Abstract

Objectives

The aims of the study were to determine the prevalence of suspected developmental delay in children living in poor areas of rural China and to investigate factors influencing child developmental delay.

Design

A community-based, cross-sectional survey was conducted.

Eighty-three villages in Shanxi and Guizhou Provinces, China.

Participants

A total of 2514 children aged 6–35 months and their primary caregivers.

Outcome measures

Suspected child developmental delay was evaluated using the Ages & Stages Questionnaires-Chinese version. Caregivers’ education and age, wealth index, child feeding index, parent-child interaction, number of books and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale were reported by the primary caregivers. Haemoglobin levels were measured using a calibrated, automated analyser. Birth weight was obtained from medical records.

Results

Overall, 35.7% of the surveyed children aged 6–35 months demonstrated suspected developmental delay. The prevalence of suspected developmental delay was inversely associated with age, with the prevalence among young children aged 6–11 months being almost double that of children aged 30–35 months (48.0% and 22.8%, respectively). Using a structural equation model, it was demonstrated that caregiver’s care and stimulus factors and child’s haemoglobin level were directly correlated, while caregiver’s sociodemographic factors were indirectly associated with suspected developmental delay.

Conclusions

The prevalence of suspected developmental delay is high in poor rural areas of China, and appropriate interventions to improve child development are needed.

Keywords: child protection, community child health, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This cross-sectional study evaluated suspected developmental delay among children under 3 years of age in poor rural areas of China.

A structural equation model is a good approach to examine the factors influencing suspected developmental delay.

A few binary variables were not incorporated in the structural equation model because of methodological limitations.

Introduction

Developmental delay encompasses a wide spectrum of impairments or lack of developmental features that are appropriate to a child’s age. It may manifest in various ways that include the motor, mental, language and social domains.1 2 Worldwide, developmental delay accounts for more morbidity across the life span than any other chronic condition.3 A conservative estimate is that across the world more than 200 million children under 5 years old failed to reach their potential in cognitive and social-emotional development. As a number of social factors such as poverty, malnutrition, lack of appropriate care, and child abuse and neglect have been identified as contributing to developmental delay,4 developmental delay has become a major issue in low-income and middle-income countries. Moreover, national statistics on young children’s cognitive or social-emotional development are not available for most developing countries. This gap contributes to the invisibility of the issue of developmental delay. With a total of 15 million disadvantaged children (defined as stunted, living in poverty or both), China has the third largest number of disadvantaged children globally, following India (65 million) and Nigeria (16 million).4 It is clear that interventions and policies designed to promote child development and prevent or ameliorate developmental delay are urgently needed as China moves forward.

The pathway between poverty and poor development described by Walker et al is built on the fact that poverty is associated with inadequate food, and poor access to water, sanitation and hygiene.5 Poverty is also related to poor maternal education, increasing maternal stress, depression and inadequate stimulation at home. All of these factors are detriment to the development of the child, and may lead to poor school performance and achievement. In addition, poverty and sociocultural contextual risk factors may increase young children’s exposure to biological and psychosocial risks, and the accumulation of risks can significantly harm child development. Children in developing countries are frequently exposed to multiple and cumulative risks that negatively affect their development, especially by changing their brain structure and function, and behaviour.6

Biological risk factors related to young children’s developmental delay include infectious disease, chronic malnutrition, iodine deficiency, iron deficiency, anaemia, malaria, low birth weight, preterm birth, and exposure to lead or arsenic.5 7–10

The psychological risk factors associated with developmental delay are mainly related to parenting, more specifically, cognitive stimulation, caregiver sensitivity and responsiveness to the child, and caregiver affect in terms of emotional warmth or rejection of the child.5 Parents and caregivers can play an important role in providing the child with a healthy, safe and caring environment.11

These biological and psychological risk factors are sensitive to contextual factors such as poverty and maternal depression.5 Common mental disorders including depression and anxiety among women during pregnancy or in the first postpartum year are recognised as a public health issue globally. There is emerging evidence showing that maternal mental disorders have adverse impacts on the physical and psychological development of fetuses and infants.12–18

In sum, various social, biological and psychological factors may contribute to the delay in child development. The existing evidence indicates that in developing countries, four major risk factors affect at least 20%–25% of the children:5 inadequate cognitive stimulation, stunting, iron deficiency and iodine deficiency. There is a paucity of data on the prevalence and risk factors for developmental delay in China, especially in poor rural areas where children are at high risk of developmental delay due to economic and social constraints. In addition, although the factors influencing delay in child development have been widely studied, as in our previous study,19 the relationships among these factors and their direct and indirect associations with the developmental outcome have been seldom examined. Compared with the most commonly used methods, a structural equation model can effectively control measurement error.20 More importantly, a structural equation model can tackle multiple dependent variables simultaneously and examine the relationships between dependent and independent variables at the same time without adjusting for confounders. In particular, the structural equation model enables a latent variable approach by using the idea that theoretical concepts such as intelligence cannot be measured directly but, instead, observable indicators are given. The goals of this study were to determine the prevalence of developmental delay in young children in rural China and to the explore factors contributing to child developmental delay.

Method

Participants and design

A community-based cross-sectional survey on child health, nutrition and development was conducted between July and September 2013 in the remote mountainous areas of Shanxi and Guizhou Provinces, which are located in the central and south-west regions of China, respectively. The study locations belong to the Integrated Early Childhood Development Project funded by UNICEF, and 83 villages from six counties in the two provinces were selected based on the following criteria: (1) More than 50 children under 3 years old. (2) Having a township health centre staffed with maternal and child health professionals. (3) Reachable by vehicles. The study population comprised all children in the chosen villages under 3 years of age and their primary caregivers (defined as person(s) who took primary responsibility for taking care of the child in the family). The survey included 2953 of 4288 eligible children and their primary caregivers. The response rate was 68.9%. All caretakers provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Apparently normal children were included in the present study, while children with hearing disabilities (eg, deaf children) (n=16) were excluded because the disabilities may directly affect their performance. In addition, we excluded children aged 1–5 months (n=326) because their haemoglobin values had not been tested; children with implausible haemoglobin values (n=1, haemoglobin =225 g/L); and respondents who were not primary caregivers (n=96). Therefore, the final sample size for this analysis was 2514 children.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for design or implementation of the study. The results of growth and anaemia were disseminated to the caregivers immediately. There are no plans to disseminate the results of the research to study participants or the relevant patient community.

Study instruments

Outcome measure: child developmental delay measurement

The Ages & Stages Questionnaires-Chinese version (ASQ-C), which was validated recently, was used to assess the development status of children.21 This questionnaire addresses communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving and personal-social skills.22 Each domain contains six subitems and responses of ‘yes’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘not yet’ were given scores of 10, 5 and 0 points, respectively. A score of 2 SD below the cut-off point in any domain based on the normative norm indicated developmental delay. Overall suspected development delay was defined as delay in any one of the five domains of ASQ, that is, the communication, gross motor, fine motor, problem-solving and personal-social domains. The latent variable of children’s developmental status was measured using the five dimensions of ASQ-C.

Social, biological and psychological factors

Household survey questionnaire

A face-to-face interview was conducted with the children’s caregivers using a structured questionnaire developed based on UNICEF’s fifth Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey. The questionnaire contained questions on the household socioeconomic status, family structure, health, and development of children under 3 years old and their caregivers. Wealth index was assessed according to the number of home appliances (eg, telephone, television, washing machine, refrigerator and internet connection) in each household.

Zung Self-rating Depression Scale

The Zung Self-rating Depression Scale (ZSDS), which has been validated and is widely used in China,23–25 was employed to assess caregivers’ mental health status.26 27 This scale consists of 20 items scored on a scale of 1–4 based on the following responses: never or rarely, sometimes, most of the time, or always. A score between 50 and 69 indicates depression, and a score of 70 or above indicates severe depression. In the present study, caregivers with scores of 50 or higher were identified as positive.28

A modified Infants and Child Feeding Index

A modified Infant and Child Feeding Index (ICFI) was constructed based on the current feeding practices for infants and young children recommended by WHO29 and those proposed by Ruel and Menon,30 and was used to gather information on the current feeding practices of the surveyed children. This modified ICFI was based on a dietary recall of the past 24 hours from a questionnaire and it included practices related to breast feeding, bottle feeding, feeding frequency and food diversity of the children before the survey. To account for the age-specific feeding recommendations, the modified ICFI was independently performed for three different age groups: 6–8 months, 9–11 months and 12–35 months using the following variables: breast feeding (regardless of age, a score of +2 was given to a child who was breast fed); bottle feeding (regardless of age, a score of +1 was given to a child who was never bottle fed); feeding frequency (a score of +2 was given if the recommended level was reached, and a score of +1 was given if the child received fewer than recommended number of meals but not zero meals); and dietary diversity of food groups (refers to the number of different food groups). Altogether, seven food groups were considered, and a score of +2 was given if four or more food groups were consumed; a score of +1 was given if one to three food groups were consumed. Taken together, these values provided a final score for the modified ICFI.

Parent-child interaction

Parent-child interaction was assessed based on the following six activities that caregivers participated in with their child: (1) Reading books to a child. (2) Telling stories to a child. (3) Singing songs to or with a child. (4) Taking a child outside the home, yard or enclosure. (5) Playing with toys with a child (6) Naming, counting or drawing things with a child to promote learning. If one of the abovementioned behaviours was present a score of +1 was given; a total score of +6 was possible.

Haemoglobin concentration

Trained staff members measured each child’s haemoglobin concentration using a capillary blood sample with a calibrated and automated analyser (HemoCue 201 (HemoCue, Angelholm, Sweden)). Anaemia was defined as haemoglobin concentration <110 g/L for preschool children, based on the global definition with adjustment for altitude.31 Children with anaemia were referred to an appropriate health facility for treatment.

Anthropometric measurements

Birth weight was obtained from medical records. The latent variable, caregiver factor, was measured by assessing caregivers’ education, caregivers’ age and the Wealth Index. Care and stimulus were measured by assessing the parent-child interaction, number of books and ZSDS Score.

Data analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows (V.16.0, SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Descriptive statistics are shown as medians, ranges and IQRs for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. A structural equation model (Amos 20 for Windows, IBM, Armonk, New York, USA) was used to test whether the hypothetical explanatory model fits the observed data, by applying the asymptotically distribution-free estimate. The hypothetical explanatory model was derived from the literature4 5 and the result of a univariate regression. The assignment rules and explanation of the variables in the structural equation model are listed in table 1. The model was modified according to statistics suggested by the modification index in Amos, and an absolute value ≥1.96 (P ≤0.05) for the standardised β-coefficient T was considered to indicate statistical significance. The Goodness-of-fit Index (GFI), Normal Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to test the model fit. For GFI, CFI and NFI, a value of 1 refers to a perfect fit, whereas a value >0.9 indicates an adequate fit. For RMSEA, a value <0.05 indicates a good model. A χ2 statistic for testing the null hypothesis was not required, because the sample size was larger than 1000. A latent variable approach assumes that all dimensions of ASQ have the same percentage and variance and that there is no measurement error. This generates a latent variable of children’s development status.32

Table 1.

Assignment rules and explanations of variables in the structural equation model

| Variable | Assignment rules or explanation |

| Caregiver’s education | Illiteracy, +1 |

| Primary school, +2 | |

| Junior high school, +3 | |

| Senior high school and above, +4 | |

| Caregiver’s age | Caregiver’s integer age |

| Wealth Index | Numbers of accessories including phone (telephone or mobile), washing machine, refrigerator, TV set, access to internet |

| Parent-child interaction | Six behaviours including read books to child, told stories, sang songs, took child outside the home, played with child, and named, counted or drew things to promote learning would form stimulus signals |

| Numbers of books | Numbers of books children owned presently |

| Score of ZSDS | Reversed score of caregiver’s depression assessed by ZSDS |

| Modified ICFI | Breast feeding:

Feeding frequency:

|

| Birth weight | Birth weight of child (medical records or parental report) |

| Haemoglobin value for children | Haemoglobin value we tested |

| Communication | Score of communication assessed by ASQ |

| Gross motor | Score of gross motor assessed by ASQ |

| Fine motor | Score of fine motor assessed by ASQ |

| Problem-solving | Score of problem-solving assessed by ASQ |

| Personal-social | Score of personal-social assessed by ASQ |

ASQ, Ages & Stages Questionnaires; ICFI, Infant and Child Feeding Index; ZSDS, Zung Self-rating Depression Scale.

Results

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of participants

Children aged 6–11 months (21.0%) accounted for the fewest subjects, and there were more boys (56.8%) than girls in the study population (table 2). Approximately half the subjects (47.9%) were first-born children, 11.4% were left-behind children (ie, their parents were migrant workers who leave rural areas for the cities while leaving children behind in their home towns). More than a third of the subjects (35.5%) were ethnic minorities. The majority of the caregivers interviewed (79.6%) was mothers of the children; the mean (±SD) age of the caregivers was 30.19±9.71 years, and most of this group (63.5%) had completed 9 years of education (secondary) or more. Of the surveyed households, 51% lived under the national poverty line of $1 per day (not shown in table 2) and 45% lived more than 5 km from the nearest health facilities.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of sampled child-caregiver pairs (n=2514)

| N | % | N | % | ||

| Child age (months) | Caregivers interviewed | ||||

| 6–11 | 528 | 21.0 | Mother | 2002 | 79.6 |

| 12–23 | 1034 | 41.1 | Father | 189 | 7.5 |

| 24–35 | 952 | 37.9 | Grandparents | 320 | 12.7 |

| Child gender | Others | 3 | 0.1 | ||

| Male | 1427 | 56.8 | Caregivers’ age | ||

| Female | 1087 | 43.2 | <20 | 42 | 1.7 |

| Having elder sibling | 20- | 1561 | 62.1 | ||

| Yes | 1277 | 50.8 | 30- | 539 | 21.4 |

| No | 1203 | 47.9 | 40- | 349 | 13.9 |

| Unknown | 34 | 1.4 | Unknown | 23 | 0.9 |

| Left-behind children | Caregivers’ education | ||||

| Yes | 286 | 11.4 | Illiteracy | 256 | 10.2 |

| No | 2228 | 88.6 | Primary education | 661 | 26.3 |

| Ethnicity | Secondary | 1277 | 50.8 | ||

| Han | 1621 | 64.5 | Above secondary | 320 | 12.7 |

| Minority | 893 | 35.5 | Distance to health facility | ||

| <5 km | 1345 | 53.5 | |||

| ≥5 km | 1131 | 45.0 | |||

| Unknown | 38 | 1.5 |

Suspected developmental delay among children under 3 years of age

Overall, 35.7% of the surveyed children under 3 years of age had suspected developmental delay (table 3). Across all age groups, the prevalence of suspected developmental delay was inversely associated with the child’s age, with the highest rate (48.0%) among children aged 6–11 months and the lowest (22.8%) among children aged 30–35 months. Across all domains, the prevalence of delay in communication skills was the lowest (8.9%) and that of delay in fine motor skills was the highest (20.6%); the prevalence of the other domains ranged from 15.1% to 16.7%.

Table 3.

Prevalence of suspected developmental delay

| 6 months n(%) n=538 |

12 months n(%) n=473 |

18 months n(%) n=561 |

24 months n(%) n=517 |

30 months n(%) n=435 |

Total n(%) n=2514 |

|

| Suspected developmental delay | 258 (48.0) | 210 (44.4) | 207 (36.9) | 123 (23.8) | 99 (22.8) | 897 (35.7) |

| Delay in subscales | ||||||

| Communication | 92 (17.4) | 46 (9.7) | 46 (8.2) | 22 (4.3) | 18 (4.1) | 224 (8.9) |

| Gross motor | 107 (20.3) | 85 (18.0) | 83 (14.8) | 61 (11.8) | 44 (10.1) | 380 (15.1) |

| Fine motor | 157 (29.7) | 145 (30.7) | 144 (25.7) | 50 (9.7) | 23 (5.3) | 519 (20.6) |

| Problem-solving | 98 (18.6) | 131 (27.7) | 84 (15.0) | 50 (9.7) | 56 (12.9) | 419 (16.7) |

| Personal-social | 102 (19.3) | 92 (19.5) | 96 (17.1) | 63 (12.2) | 52 (12.0) | 405 (16.1) |

Social, biological and psychological factors

The Wealth Index in the surveyed families ranged from 0 to 5, with a median of 4, indicating that most of the families owned major appliances. The parent-child interaction scores ranged from 0 to 6, with a median score of 6. On average, the surveyed children owned only one book (median=1, IQR=3). The caregivers’ ZSDS Score in this sample ranged from 38 to 80, with a median score of 63.76. Nearly two-fifths of the caregivers (38.5%) had symptoms of depression. The ICFI ranged from 0 to 7, with a median score of 2. The haemoglobin concentrations of the surveyed children were 51–178 g/L, with a median of 110 g/L. The prevalence of anaemia was high at 43.8%. The birth weight of the surveyed children ranged from 1.40 kg to 6.00 kg, with a median of 3.30 kg; 2.9% had low birth weight (ie, a birth weight of less than 2.5 kg).

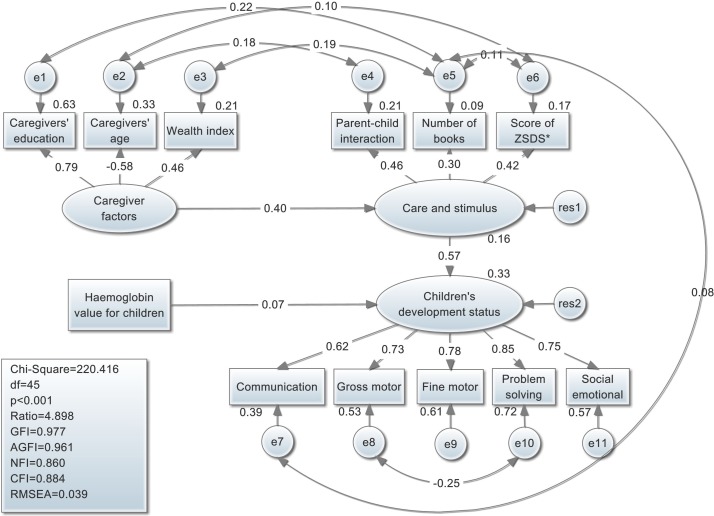

Structural equation model for suspected developmental delay in children

About half of the squared multiple correlations of variables were more than 0.50 (online supplementary table S1), which indicated that the variables had good reliability. In the final structural equation model (table 4), modified ICFI and birth weight were excluded from the model, because no statistically significant relationships were found between these and the other variables. The estimated covariance and paths for this model are shown in figure 1. The following three variables predicted the developmental status of subjects: (1) Caregiver sociodemographic factors such as caregiver’s education, age and Wealth Index (total effect on child developmental status =0.23). (2) Care and stimulus factors measured by parent-child interaction, number of books and ZSDS Score (direct effect=0.57). (3) Child haemoglobin concentration (direct effect=0.07). For example, caregivers of younger age were more likely to interact with the children (covariance of residuals=−0.18), and the latent variable of caregiver factors had a direct positive effect on the care and stimulus factors (path coefficient=0.40) but an indirect positive effect on the developmental status of children. The overall model fit was good, as reflected by a GFI of 0.977 and CFI of 0.884.

Table 4.

Regression weights of the structural equation model

| Equation | Estimates (unstandardised) |

Estimates (standardised) |

SE | Critical ratio | P values |

| Regression weights | |||||

| Care and stimulus ← caregiver factor | 0.402 | 0.401 | 0.047 | 8.497 | <0.001 |

| Children’s developmental status ← care and stimulus | 9.608 | 0.573 | 0.913 | 10.525 | <0.001 |

| Children’s developmental status ← haemoglobin value for children | 0.593 | 0.071 | 0.178 | 3.331 | 0.001 |

| Caregivers’ education ← caregiver factor | 1.000 | 0.794 | |||

| Caregivers’ age ← caregiver factor | −8.358 | −0.576 | 0.543 | −15.380 | <0.001 |

| Wealth index ← caregiver factor | 0.775 | 0.461 | 0.055 | 14.163 | <0.001 |

| Parent-child interaction ← care and stimulus | 1.000 | 0.456 | |||

| Numbers of books ← care and stimulus | 1.687 | 0.303 | 0.220 | 7.678 | <0.001 |

| Score of ZSDS ← care and stimulus | 4.856 | 0.415 | 0.488 | 9.944 | <0.001 |

| Communication ← children’s developmental status | 0.863 | 0.622 | 0.029 | 30.054 | <0.001 |

| Gross motor ← children’s developmental status | 0.970 | 0.726 | 0.030 | 32.608 | <0.001 |

| Fine motor ← children’s developmental status | 1.132 | 0.778 | 0.028 | 40.216 | <0.001 |

| Problem-solving ← children’s developmental status | 1.188 | 0.848 | 0.030 | 40.212 | <0.001 |

| Personal-social ← children’s developmental status | 1.000 | 0.752 | |||

| Covariance | |||||

| e8 ↔ e10 | −19.912 | −0.248 | 2.961 | −6.725 | <0.001 |

| e3 ↔ e5 | 0.620 | 0.188 | 0.064 | 9.708 | <0.001 |

| e2 ↔ e4 | −1.695 | −0.175 | 0.270 | −6.290 | <0.001 |

| e1 ↔ e5 | 0.364 | 0.215 | 0.051 | 7.136 | <0.001 |

| e5 ↔ e7 | 3.079 | 0.076 | 0.680 | 4.527 | <0.001 |

| e5 ↔ e6 | −2.709 | −0.115 | 0.575 | −4.712 | <0.001 |

| e2 ↔ e6 | −5.270 | −0.100 | 1.247 | −4.228 | <0.001 |

ZSDS, Zung Self-rating Depression Scale.

Figure 1.

Structural equation model and standardised coefficient for relationships between factors that theoretically influence suspected developmental delay. CFI, Comparative Fit Index; GFI, Goodness-of-fit Index, AGFI, Adjusted Goodness-of-fit Index; NFI, Normal Fit Index; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; ZSDS, Zung Self-rating Depression Scale.

bmjopen-2018-021628supp001.pdf (181.3KB, pdf)

Discussion

The present study showed that the prevalence of suspected developmental delay among children aged 6–35 months was high and inversely related to age in the surveyed areas of poor rural China. Furthermore, a structural equation model was used to investigate the risk factors of suspected developmental delay in children. To date, only one study has examined developmental delay in rural China, and reported a prevalence of 20.0% in cognitive development and 32.3% in psychomotor development among children aged 6–12 months.33 Our study revealed that 35.7% of rural children under 3 years of age had suspected developmental delay and that among children aged 6–12 months, 17%–20% of them had delay in the communication, problem-solving, personal-social and gross motor domains, and nearly 30% had delay in fine motor development. Overall, the prevalence in our study was comparable with the results of the previous study. According to the very limited data in the WHO report,34 the prevalence of developmental delay in young children is 17% in Senegal, 15% in Nigeria, 13% in India and 24% in Brazil. The lower prevalence reported by other developing countries may reflect the underestimation and inaccurate measurement of developmental delay. The promotion of early childhood development (ECD) is a critical issue. It is recommended that the government and healthcare providers pay more attention to the early diagnosis and treatment of developmental delay. Among the five domains of ASQ, suspected developmental delay of the fine motor domain had the highest prevalence. This is a key finding that suggests the need for further intervention in poor rural areas of China.

In the structural equation model, caregiver factors, care and stimulus factors, and child haemoglobin concentrations were directly or indirectly associated with suspected developmental delay. These findings indicate areas on which future intervention programmes should focus, including improving feeding and nutrition, raising public awareness of the issue of developmental delay, and improving parenting skills to increase frequency of interaction with their children.

Relationships between caregiver factors and child development

Younger caregivers with a higher level of education and a higher Wealth Index had an indirect positive effect on child development. Previous studies have primarily investigated relationships between sociodemographic characteristics of caregivers and child development. For example, a population-based study in Argentina and a cohort study in Brazil showed that poverty and maternal education were positively associated with early attainment of selected developmental milestones as well as cognitive and motor development.35 36 Furthermore, parenting cognitive stimulation, caregivers’ responsiveness and caregivers’ effect are related to poverty, cultural values and practices.5 Similarly, the model in the present study revealed that there was a path between caregiver factors and child development, in which caregiver factors were indirect predictors of developmental delays. Although caregiver factors did not have a direct effect on childhood developmental status, the education, age and poverty levels of caregivers should receive more attention in future interventions aimed at improving child development and health.

Relationships between care and stimulus factors and child development

The present study demonstrated that the most important predictors of suspected childhood developmental delay were care and stimulus factors (path coefficient=0.57). Better parent-child interactions, more books and a lower level of maternal depression had positive effects on child development, and a 1-point increase in care and stimulus factors was associated with a 0.57-point increase in child development. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies that demonstrated the protective effects of parent-child interactions, children’s books and optimistic caregivers on child development.37 Thus, it is necessary to promote parent-child interactions, such as reading books, telling stories, singing songs, taking the child outside the home, playing with the child, and naming, counting or drawing things to promote learning and the formation of stimulus signals.5 38 39 The incidence of depression among caregivers was alarmingly high in the present sample, and is similar to that in previous findings.40 41 Additionally, the present results confirm those of other studies that reported that caregivers with depression are at an increased risk of having adverse effects on child development.17 42 Depression among caregivers not only affects the health of the child but also places such children at a greater risk of developmental delay.43 44 It is well established that concurrent maternal depression during mother-infant interactions is associated with reduced maternal responsiveness, which in turn is positively associated with later alterations in the emotional, cognitive and physical development of the infant.45 46 The present study revealed that a latent variable, care and stimulus factors (including caregiver depression scores and parent-child interactions) had a joint impact on development. Thus, there is an urgent need for child development interventions directed at phenomena related to the care and stimulation of children in poor rural China.

Relationships between haemoglobin concentrations and child development

In the present study, the haemoglobin concentrations of children had a weak positive effect on child development, whereas other biological factors, such as birth weight and modified ICFI Score, did not predict child development. These findings were not consistent with those of previous research.5 It is possible that the structural equation model used in the present study, which involved only three continuous variables that could not be treated as one latent variable due to their poor correlations, may have played a role in this discrepancy. The incidence of anaemia among children was alarmingly high in the present sample, as in a previous study.47 This issue constitutes a severe public health problem,48 and likely has a significant impact on child growth and development.4 5 49 Our results indicate that the haemoglobin concentration of children has a positive effect on child development. Fortunately, the Chinese government is aware of this public health issue and has initiated a programme to provide micronutrient supplements named Ying Yang Bao to children aged 6–35 months living in poor rural areas, free of charge. This intervention may decrease the prevalence of anaemia in children. Although we found that birth weight and modified ICFI did not predict child development, poor maternal nutrition, infections and child-feeding practices in poor areas of rural China should be regularly monitored and improved by the government.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations that should be considered. First, due to the cross-sectional design of this study, the associations revealed by the structural equation model could not be confirmed as causative relationships, even though these models are a powerful statistical technique for the simultaneous consideration of multiple variables. Further evidence from cohort studies and interventional studies is needed to infer the causality of these relationships. Second, due to the restrictions and limitations inherent in the methodology and the software, many binary variables, including those measuring infant and young childhood infections (eg, diarrhoea and pneumonia) were not incorporated into the structural equation model. Third, this study was conducted in two provinces in central and south-west China. These study sites are not representative of all poor rural areas of China. Caution is warranted when generalising our findings to other rural areas in China.

Conclusions

These preliminary findings indicate that the prevalence of suspected developmental delay is high in poor rural areas of China. More attention needs to be paid to ECD. Interventions should specifically target and support families in poverty and those with low education levels, as well as prioritise maternal and children’s nutrition and mental health, so as to improve fetal and ECD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the local healthcare providers for data collection and all the participants in this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: YL performed the data analysis. JZ drafted the article. SG, XW and RWS designed the study. JZ, QW, CZ and SL collected the data. XW and CZ critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: UNICEF grants ‘Health and Nutrition’ (0315-China/YH702).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Peking University’s Biomedical Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data sets analysed in the current study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Gupta N, Kabra M. Approach to the diagnosis of developmental delay - the changing scenario. Indian Journal Medical Research 2014;139:4–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rimal HS, Pokharel A, Saha V, et al. . Burden of developmental and behavioral problems among children - a descriptive hospital based study. Journal of Nobel Medical College 2014;3:45–9. 10.3126/jonmc.v3i1.10054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease: 2004 update: published by the Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Grantham-McGregor S, Cheung YB, Cueto S, et al. . Developmental potential in the first 5 years for children in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:60–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60032-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Walker SP, Wachs TD, Gardner JM, et al. . Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet 2007;369:145–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wachs TD. Necessary but not sufficient: the role of individual and multiple influences on human development. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Qian M, Wang D, Watkins WE, et al. . The effects of iodine on intelligence in children: a meta-analysis of studies conducted in China. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2005;14:32–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walker SP, Chang SM, Powell CA, et al. . Effects of early childhood psychosocial stimulation and nutritional supplementation on cognition and education in growth-stunted Jamaican children: prospective cohort study. Lancet 2005;366:1804–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67574-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fernando SD, Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. The ’hidden' burden of malaria: cognitive impairment following infection. Malar J 2010;9:366–11. 10.1186/1475-2875-9-366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carter JA, Neville BG, Newton CR. Neuro-cognitive impairment following acquired central nervous system infections in childhood: a systematic review. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 2003;43:57–69. 10.1016/S0165-0173(03)00192-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alfredo R, Loizillon A. The Review of care, education and child development indicators in early childhood. France: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adewuya AO, Ola BO, Aloba OO, et al. . Impact of postnatal depression on infants' growth in Nigeria. J Affect Disord 2008;108:191–3. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Misri S, Oberlander TF, Fairbrother N, et al. . Relation between prenatal maternal mood and anxiety and neonatal health. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:684–9. 10.1177/070674370404901006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rahman A, Bunn J, Lovel H, et al. . Maternal depression increases infant risk of diarrhoeal illness: –a cohort study. Arch Dis Child 2007;92:24–8. 10.1136/adc.2005.086579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rahman A, Iqbal Z, Bunn J, et al. . Impact of maternal depression on infant nutritional status and illness: a cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:946–52. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.9.946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Huang J, Sherraden M, Purnell JQ. Impacts of child development accounts on maternal depressive symptoms: evidence from a randomized statewide policy experiment. Soc Sci Med 2014;112:30–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pearson RM, Melotti R, Heron J, et al. . Disruption to the development of maternal responsiveness? The impact of prenatal depression on mother-infant interactions. Infant Behav Dev 2012;35:613–26. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Letourneau NL, Tramonte L, Willms JD, et al. . Maternal depression, family functioning and children’s longitudinal development. J Pediatr Nurs 2013;28:223–34. 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei QW, Zhang JX, Scherpbier RW, et al. . High prevalence of developmental delay among children under three years of age in poverty-stricken areas of China. Public Health 2015;129:1610–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bian R, Che H, Yang H. Item parceling strategies in structural equation modeling. Advances in Psychological Science 2007;15:567–76. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wei M, Bian X, Squires J, Mei W, Xiaoyan B, Jane S, et al. . [Studies of the norm and psychometrical properties of the ages and stages questionnaires, third edition, with a Chinese national sample]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2015;53:913–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bian X, Yao G, Squires J, et al. . Translation and use of parent-completed developmental screening test in Shanghai. Journal of Early Childhood Research 2012;10:162–75. 10.1177/1476718X11430071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lee HC, Chiu HF, Wing YK, et al. . The zung self-rating depression scale: screening for depression among the Hong Kong Chinese elderly. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1994;7:216–20. 10.1177/089198879400700404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mammadova F, Sultanov M, Hajiyeva A, et al. . Translation and adaptation of the Zung self- rating depression scale for application in the bilingual Azerbaijani population. Eur Psychiatry 2012;27(Suppl 2):S27–S31. 10.1016/S0924-9338(12)75705-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shen LL, Lao LM, Jiang SF, et al. . A survey of anxiety and depression symptoms among primary-care physicians in China. Int J Psychiatry Med 2012;44:257–70. 10.2190/PM.44.3.f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wei Q, Zhang C, Zhang J, et al. . Caregiver’s depressive symptoms and young children’s socioemotional development delays: a cross-sectional study in poor rural areas of china. Infant Mental Health Journal 2018;27:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shi HF, Zhang JX, Wang XL, et al. . [Effectiveness of integrated early childhood development intervention on nurturing care for children aged 0-35 months in rural China]. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi 2018;56:110–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. ZUNG WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965;12:63 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dewey K. Guiding principles for complementary feeding of the breastfed child. Washington D 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruel MT, Menon P. Child feeding practices are associated with child nutritional status in Latin America: innovative uses of the demographic and health surveys. J Nutr 2002;132:1180–7. 10.1093/jn/132.6.1180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. WHO. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Vitamin and mineral nutrition information system. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.1 (accessed 11 Jan 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ml W. Structural equation modeling–the operation and application of AMOS. Chongqing: Chongqing University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Luo R, Shi Y, Zhou H, et al. . Micronutrient deficiencies and developmental delays among infants: evidence from a cross-sectional survey in rural China. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008400 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. World Health Organization. Developmental Difficulties in Early Childhood: Prevention, Early Identification, Assessment and Intervention in Low- And Middle-Income Countries: A Re, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lejarraga H, Pascucci MC, Krupitzky S, et al. . Psychomotor development in Argentinean children aged 0-5 years. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2002;16:47–60. 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2002.00388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lima MC, Eickmann SH, Lima AC, et al. . Determinants of mental and motor development at 12 months in a low income population: a cohort study in northeast Brazil. Acta Paediatr 2004;93:969–75. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2004.tb18257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cheung YB, Yip PS, Karlberg JP. Fetal growth, early postnatal growth and motor development in Pakistani infants. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:66–72. 10.1093/ije/30.1.66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chiang YC, Lin DC, Lee CY, et al. . Effects of parenting role and parent-child interaction on infant motor development in Taiwan Birth Cohort Study. Early Hum Dev 2015;91:259–64. 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kagitcibasi C, Sunar D, Bekman S. Long-term effects of early intervention: Turkish low-income mothers and children. J Appl Dev Psychol 2001;22:333–61. 10.1016/S0193-3973(01)00071-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wolf AW, De Andraca I, Lozoff B. Maternal depression in three Latin American samples. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2002;37:169–76. 10.1007/s001270200011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Organization WH. Developmental difficulties in early childhood: prevention, early identification, assessment and intervention in low- and middle-income countries. World Health Organization 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sohr-Preston SL, Scaramella LV. Implications of timing of maternal depressive symptoms for early cognitive and language development. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2006;9:65–83. 10.1007/s10567-006-0004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, et al. . Post-partum depression and the mother-infant relationship in a South African peri-urban settlement. Br J Psychiatry 1999;175:554–8. 10.1192/bjp.175.6.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Murray L, Cooper P. Effects of postnatal depression on infant development. Arch Dis Child 1997;77:99–101. 10.1136/adc.77.2.99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bigelow AE, MacLean K, Proctor J, et al. . Maternal sensitivity throughout infancy: continuity and relation to attachment security. Infant Behav Dev 2010;33:50–60. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McElwain NL, Booth-Laforce C. Maternal sensitivity to infant distress and nondistress as predictors of infant-mother attachment security. J Fam Psychol 2006;20:247–55. 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hipgrave DB, Fu X, Zhou H, et al. . Poor complementary feeding practices and high anaemia prevalence among infants and young children in rural central and western China. Eur J Clin Nutr 2014;68:916–24. 10.1038/ejcn.2014.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lawson JA. Comparative Quantification of Health Risks. Global and Regional Burden of Disease Attributable to Selected Major Risk Factors by Majid Ezzati; Alan D; Lopez; Anthony Rodgers; Christopher J.L. Murray. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2004:163. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Engle PL, Black MM, Behrman JR, et al. . Strategies to avoid the loss of developmental potential in more than 200 million children in the developing world. The Lancet 2007;369:229–42. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60112-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-021628supp001.pdf (181.3KB, pdf)