Abstract

Context

Infrared and (sub-)mm observations of disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars point to a chemical differentiation between both types of disks, with a lower detection rate of molecules in disks around hotter stars.

Aims

To investigate the underlying causes of the chemical differentiation indicated by observations we perform a comparative study of the chemistry of T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks. This is one of the first studies to compare chemistry in the outer regions of these two types of disks.

Methods

We developed a model to compute the chemical composition of a generic protoplanetary disk, with particular attention to the photochemistry, and applied it to a T Tauri and a Herbig Ae/Be disk. We compiled cross sections and computed photodissociation and photoionization rates at each location in the disk by solving the FUV radiative transfer in a 1+1D approach using the Meudon PDR code and adopting observed stellar spectra.

Results

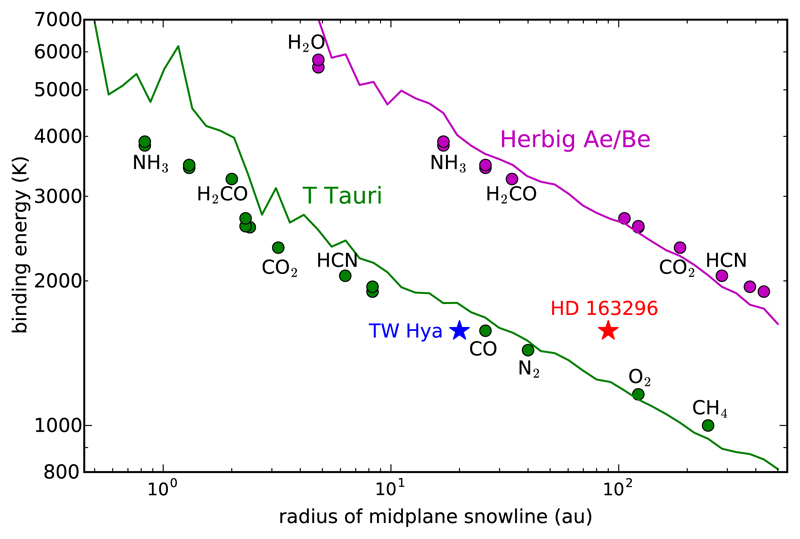

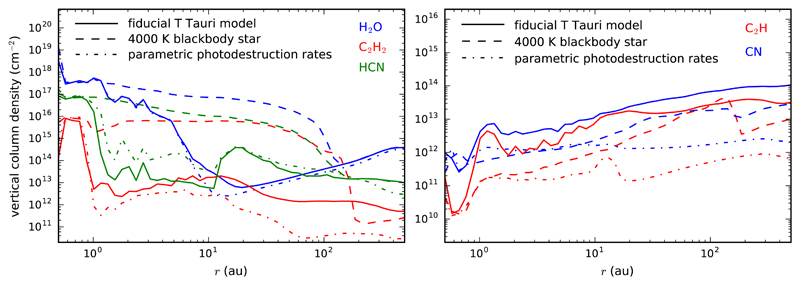

The warmer disk temperatures and higher ultraviolet flux of Herbig stars compared to T Tauri stars induce some differences in the disk chemistry. In the hot inner regions, H2O, and simple organic molecules like C2H2, HCN, and CH4 are predicted to be very abundant in T Tauri disks and even more in Herbig Ae/Be disks, in contrast with infrared observations that find a much lower detection rate of water and simple organics toward disks around hotter stars. In the outer regions, the model indicates that the molecules typically observed in disks, like HCN, CN, C2H, H2CO, CS, SO, and HCO+, do not have drastic abundance differences between T Tauri and Herbig Ae disks. Some species produced under the action of photochemistry, like C2H and CN, are predicted to have slightly lower abundances around Herbig Ae stars due to a narrowing of the photochemically active layer. Observations indeed suggest that these radicals are somewhat less abundant in Herbig Ae disks, although in any case the inferred abundance differences are small, of a factor of a few at most. A clear chemical differentiation between both types of disks concerns ices. Owing to the warmer temperatures of Herbig Ae disks, one expects snowlines lying farther away from the star and a lower mass of ices compared to T Tauri disks.

Conclusions

The global chemical behavior of T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks is quite similar. The main differences are driven by the warmer temperatures of the latter, which result in a larger reservoir or water and simple organics in the inner regions and a lower mass of ices in the outer disk.

Keywords: astrochemistry; molecular processes; protoplanetary disks; stars: variables: T Tauri, Herbig Ae/Be

1. Introduction

Circumstellar disks around young stars, the so-called protoplanetary disks, are an important link in the evolution from molecular clouds to planetary systems. These disks allow to feed with matter the young star and provide the scenario in which planets form. The study of the physical and chemical conditions of these objects is thus of paramount importance to understand how and from which type of material do planets form. Protoplanetary disks are mainly composed of molecular gas and dust. The last two decades have seen significant progress in the study of their chemical composition thanks to astronomical observations at wavelengths from the millimeter to the ultraviolet domains.

Observations with ground-based mm and sub-mm telescopes such as the 30m antenna of the Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique (IRAM), the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT), and the APEX 12m telescope, which are sensitive to the outer cool regions of disks, have provided information on the presence of various gaseous molecules such as CO, HCO+, H2CO, C2H, HCN, HNC, CN, CS, and SO (Dutrey et al. 1997; Kastner et al. 1997, 2014; van Zadelhoff et al. 2001; Thi et al. 2004; Fuente et al. 2010; Guilloteau et al. 2013, 2016; Pacheco-Vázquez et al. 2015). Interferometers that operate at (sub-)millimeter wavelengths such as the OVRO millimeter array, the IRAM array at Plateau de Bure (PdBI, now known as NOEMA), and the Submillimeter Array (SMA) have also allowed to perform sensitive observations leading to the detection of new molecules such as N2H+ and HC3N, and to obtain maps of the emission distribution of some molecules with angular resolutions down to a few arcsec (Qi et al. 2003, 2008, 2013a; Dutrey et al. 2007, 2011; Piétu et al. 2007; Schreyer et al. 2008; Henning et al. 2010; Öberg et al. 2010, 2011; Chapillon et al. 2012a,b; Fuente et al. 2012; Graninger et al. 2015; Teague et al. 2015; Pacheco-Vázquez et al. 2016). In recent years, the advent of the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA) is making possible to characterize the molecular content of protoplanetary disks with an unprecedented sensitivity and angular resolution (down to sub-arcsec scales). For example, thanks to ALMA it has been possible to detect new molecules such as cyclic C3H2 (Qi et al. 2013b; Bergin et al. 2016), CH3CN (Öberg et al. 2015), and CH3OH (Walsh et al. 2016), and to image the CO snowline in a few disks (Mathews et al. 2013; Qi et al. 2013c, 2015; Schwarz et al. 2016; Zhang et al. 2017). Infrared (IR) observations using space telescopes such as Spitzer and ground-based facilities such as the Very Large Telescope (VLT) and the Keck Observatory telescopes have provided a view of the molecular content of the very inner regions of protoplanetary disks, where absorption and emission lines from molecules such as CO, CO2, H2O, OH, HCN, C2H2, and CH4 have been routinely observed (Lahuis et al. 2006; Gibb et al. 2007; Salyk et al. 2007, 2008, 2011; Carr & Najita 2008, 2011, 2014; Pontoppidan et al. 2010a,b; Najita et al. 2010, 2013; Kruger et al. 2011; Doppmann et al. 2011; Fedele et al. 2011; Mandell et al. 2012; Bast et al. 2013; Gibb & Horne 2013; Sargent et al. 2014; Banzatti et al. 2017). The launch of the Herschel Space Observatory was also very helpful to investigate the chemical content at far-IR wavelengths, with the detection of molecules such as CH+ (Thi et al. 2011) and NH3 (Salinas et al. 2016), and the exhaustive characterization of H2O and OH from the inner to the outer regions (Hogerheijde et al. 2011; Riviere-Marichalar et al. 2012; Meeus et al. 2012; Fedele et al. 2012, 2013; Podio et al. 2013). Probing the molecular gas in the inner regions of disks through the most abundant molecule, H2, has also been possible thanks to observations at ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths using the Hubble Space Telescope (Ingleby et al. 2009; France et al. 2012).

On the theoretical side, the chemical structure of protoplanetary disks has been also widely studied during the last two decades. Early models focused on the one dimensional radial structure of disks along the midplane (Aikawa et al. 1996, 1997, 1999; Willacy et al. 1998; Aikawa & Herbst 1999a), although it was later on recognized that the chemical composition presents also an important stratification along the vertical direction, with a structure consisting of three main layers: the cold midplane where molecules are mostly condensed as ices on dust grains, a warm upper layer where a rich chemistry takes place, and the uppermost surface layer where photochemistry driven by stellar and interstellar far ultraviolet (FUV) photons regulates the chemical composition (Aikawa & Herbst 1999b, 2001; Willacy & Langer 2000; Aikawa et al. 2002). In recent years there has been an interest in identifying the main processes that affect the abundance and distribution of molecules in protoplanetary disks. An important number of studies have addressed in detail the role of processes such as the interaction with FUV and X-ray radiation (Willacy & Langer 2000; Markwick et al. 2002; Bergin et al. 2003; Ilgner & Nelson 2006a; Agúndez et al. 2008; Aresu et al. 2011; Fogel et al. 2011; Walsh et al. 2010, 2012), the interplay between the thermal and chemical structure (Glassgold et al. 2004; Woitke et al. 2009), turbulent mixing and other transport processes (Ilgner et al. 2004; Semenov et al. 2006; Ilgner & Nelson 2006b; Willacy et al. 2006; Aikawa 2007; Heinzeller et al. 2011; Semenov et al. 2011), and the evolution of dust grains as they grow by coagulation and settle onto the midplane regions (Aikawa & Nomura 2006; Fogel et al. 2011; Akimkin et al. 2013). Some studies have investigated the impact of using different chemical networks (Semenov et al. 2004; Ilgner & Nelson 2006c; Kamp et al. 2017) and the sensitivity to uncertainties in the rate constants of chemical reactions (Vasyunin et al. 2008). Various specific aspects of the chemistry of protoplanetary disks have also been addressed in detail as, for example, deuterium fractionation (Willacy 2007; Willacy & Woods 2009; Thi et al. 2010; Furuya et al. 2013; Yang et al. 2013; Albertsson et al. 2014), the formation and survival of water vapour (Dominik et al. 2005; Glassgold et al. 2009; Bethell & Bergin 2009; Du & Bergin 2014), and the formation of particular species such as benzene (Woods & Willacy 2007) and complex organic molecules (Walsh et al. 2014).

Overall, protoplanetary disks are complex systems where many different processes such as gas phase chemistry, interaction with stellar and interstellar FUV photons, transport processes, adsorption and desorption from dust grains, chemical reactions on grain surfaces, and grain evolution are all together governing the chemical composition (see reviews by Bergin et al. 2007, Henning & Semenov 2013, Dutrey et al. 2014, and Pontoppidan et al. 2014).

Disks are commonly found around young low-mass (T Tauri) and intermediate-mass (Herbig Ae/Be) stars, which have quite different masses and effective temperatures, and thus may affect differently the disk chemical composition. For example, Herbig Ae/Be stars have a higher ultraviolet flux and disks around them are warmer than around T Tauri stars. Indeed, T Tauri and Herbig Ae disks have been extensively observed from millimeter to IR wavelengths and it has been found that the detection rate of molecules (for example, H2O, C2H2, HCN, CH4, CO2, H2CO, C2H, and N2H+) is strikingly lower toward Herbig Ae disks than toward disks around T Tauri stars (Mandell et al. 2008; Schreyer et al. 2008; Pontoppidan et al. 2010a; Öberg et al. 2010, 2011; Fedele et al. 2011, 2012, 2013; Salyk et al. 2011; Riviere-Marichalar et al. 2012; Meeus et al. 2012; Guilloteau et al. 2016; Banzatti et al. 2017). This fact may indicate that there is a marked chemical differentiation between both types of disks. Most theoretical studies on the chemistry of protoplanetary disks have focused on disks around T Tauri-like stars, and only a few have studied Herbig Ae/Be disks (e.g., Jonkheid et al. 2007). Here we present a comparative study in which we investigate the two dimensional distribution of molecules in disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars. In a recent study, Walsh et al. (2015) have investigated the differences in the chemical composition between disks around stars of different spectral type, focusing on the inner disk regions. In this study, we make a thorough investigation of the main chemical differences and similarities between T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks from the inner to the outer disk regions, which to our knowledge has not been investigated in detail. We are particularly concerned with a detailed treatment of the photochemistry and with the impact of the FUV illumination from these two types of stars on the chemical composition of the disk. To this purpose we have implemented the Meudon PDR code in the disk model to compute photodestruction rates at each location in the disk in a 1 + 1D approach. We adopted FUV stellar spectra coming from observations of representative T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars. In Sec. 2 we present in detail our physical and chemical disk model, with a particular emphasis on the photochemistry (further described in Appendices A and B), in Sec. 3 we present the resulting abundance distributions of important families of molecules for our T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disk models and compare them with results from observations, in Sec. 4 we analyse the influence on the chemistry of the stellar spectra and the method used to compute photodestruction rates, and we summarize the main conclusions found in this work in Sec. 5.

2. The disk model

We consider a passively irradiated disk in steady state around a T Tauri or Herbig Ae/Be star. We solve the thermal and chemical structure of the disk using a procedure which can be summarized as follows. We first solve the dust temperature distribution in the disk using the RADMC code (Dullemond & Dominik 2004). We assume that gas and dust are thermally coupled except for the surface layers of the disk where we estimate the gas kinetic temperature following Kamp & Dullemond (2004). We then solve the radiative transfer of interstellar FUV photons along the vertical direction and of stellar FUV photons along the direction from the star using the Meudon PDR code (Le Petit et al. 2006) to get the photodissociation and photoionization rates of the different species at each disk location. We finally solve the chemical composition at each location in the disk as a function of time including gas phase chemical reactions, processes induced by FUV photons and cosmic rays, and interactions of gas particles with dust grains (adsorption and desorption processes).

2.1. Physical model

We adopt a fiducial model of disk representative of objects commonly found around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars (see parameters in Table 1). The disk extends between an inner radius Rin of 0.5 au and an outer radius Rout of 500 au from the star and has a mass Mdisk of 0.01 M⊙. We consider that the radial distribution of the surface density Σ is given by a power law of the type

| (1) |

where Σ0 is the surface density at a reference radius r0 and the exponent ϵ is chosen to be 1.0 between Rin and Rout. To avoid the abrupt disappearance of the disk at the inner radius we set ϵ to −12 at r < Rin, which results in a soft continuation of the disk at the inner regions.

Table 1.

Model parameters.

| Parameter | Value / Source |

|---|---|

| Disk | |

| Disk mass (Mdisk) | 0.01 M⊙ |

| Inner disk radius (Rin) | 0.5 au |

| Outer disk radius (Rout) | 500 au |

| Radial surface density power index (ϵ) | 1.0 † |

| Gas-to-dust mass ratio (ρg/ρd) | 100 |

| Dust composition | 70 % silicate 30 % graphite |

| Minimum dust grain radius (amin) | 0.001 μm |

| Maximum dust grain radius (amax) | 1 μm |

| Dust size distribution power index (β) | 3.5 |

| Interstellar radiation field | Draine (1978) |

| Cosmic-ray ionization rate of H2(ζ) | 5 × 10−17 s−1 |

| T Tauri star | |

| Stellar mass (M*) | 0.5 M⊙ |

| Stellar radius (R*) | 2 R⊙ |

| Stellar effective temperature (T*) | 4000 K |

| Herbig Ae/Be star | |

| Stellar mass (M*) | 2.5 M⊙ |

| Stellar radius (R*) | 2.5 R⊙ |

| Stellar effective temperature (T*) | 10,000 K |

ϵ = –12 at r < Rin.

We consider that dust is present in the disk with a uniform abundance and size distribution, i.e., which does not vary with radius nor height over midplane. We adopt a gas-to-dust mass ratio of 100 and consider spherical grains typically present in the interstellar medium, i.e., with the composition being a mixture of 70 % of silicate and 30 % of graphite (with optical properties taken from Draine & Lee 1984, Laor & Draine 1993, and Weingartner & Draine 2001), and the size distribution being given by the power law

| (2) |

where n(a) is the number of grains of radius a, the minimum and maximum grain radius amin and amax are 0.001 and 1 μm, and the exponent β takes a value of 3.5 according to Mathis et al. (1977).

As stellar parameters we adopt typical values of T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars. The T Tauri star is assumed to have a mass M* of 0.5 M⊙, a radius R* of 2 R⊙, and an effective temperature T* of ~4000 K, typical values of T Tauri stars of spectral type M0-K7 in Taurus (Kenyon & Hartmann 1995). In the case of the star of type Herbig Ae/Be we adopt a mass of 2.5 M⊙, a radius of 2.5 R⊙, and an effective temperature of ~10,000 K, typical values of early Ae and late Be stars (e.g., Martin-Zaïdi et al. 2008; Montesinos et al. 2009).

2.1.1. Stellar and interstellar FUV spectra

The irradiation from the central star is of great importance for the disk because it dominates the heating of gas and dust. The stellar and interstellar spectra at FUV wavelengths are also of prime importance because they control the photochemistry that takes place in the disk surface.

The FUV component of the interstellar radiation field (ISRF) adopted here is given by

| (3) |

where λ is the wavelength in Å, Iλ is the specific intensity in units of erg s−1 cm−2 Å−1 sr−1, and the expression has been obtained by fitting to the radiation field given by Draine (1978). The expression in Eq. (3) is similar to that given by Le Petit et al. (2006), except for an erratum in their first term. The ISRF given by Eq. (3) is complemented with another component that accounts for the emission at longer wavelengths (from ~2000 Å to the near IR), for which we adopt the radiation field given by Mathis et al. (1983) in the form of a combination of three diluted black bodies

| (4) |

where Bλ(T) is the Planck law at temperature T.

Concerning stellar spectra, in the case of the T Tauri star we adopt as a proxy of the stellar spectrum that of TW Hya, which consists of observations with the Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) in the 900-1150 Å wavelength range (data from program C0670102) and Hubble STIS observations in the 1150-3150 Å range (Herczeg et al. 2002; Bergin et al. 2003). The intrinsic stellar brightness is calculated adopting a distance to the star of 51 pc (Mamajek 2005), a stellar radius of 1 R⊙ (Webb et al. 1999), and a negligible interstellar reddening (Bergin et al. 2003). At wavelengths longer than 3150 Å we use a Kurucz model spectrum (Castelli & Kurucz 2004)1 with an effective temperature of 4000 K, a surface gravity of 101.5 cm s−2, and solar metallicity, scaled to match the flux of TW Hya around 3150 Å. The resulting spectrum is similar to that presented by France et al. (2014) in the 1150-1750 Å wavelength range, although their continuum level is about twice below our adopted spectrum. In the case of the star of type Herbig Ae/Be we use as a proxy the FUV spectrum of AB Aurigae, which consists of observations taken with FUSE in the 900-1190 Å wavelength range (data from program P2190301) and with Hubble STIS in the 1190-1710 Å range (Roberge et al. 2001; Ayres 2010). The intrinsic brightness of AB Aurigae is calculated adopting a distance to the star of 144 pc, a stellar radius of 2.41 R⊙, and an interstellar extinction of 0.48 mag (Martin-Zaïdi et al. 2008). For the correction due to extinction we use the method and coefficients of Fitzpatrick & Massa (2007). Longwards of 1710 Å we use a Kurucz spectrum (Castelli & Kurucz 2004) with an effective temperature of 9750 K (close to that of AB Aurigae), a surface gravity of 102.0 cm s−2, and solar metallicity.

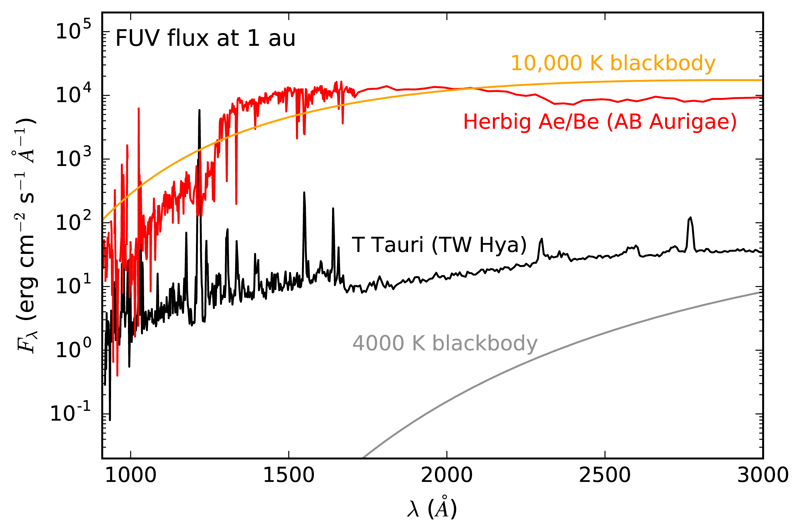

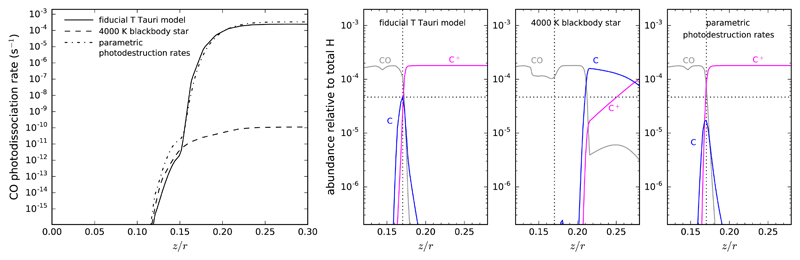

The FUV spectra adopted for the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars are shown in Fig. 1, where we also compare with spectra corresponding to blackbodies at the temperatures of the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars, 4000 K and 10,000 K, respectively. It is seen that AB Aurigae outshines by 2-3 orders of magnitude the FUV flux of TW Hya because of the much higher effective temperature. However, T Tauri stars usually have an important FUV excess and may become very bright in lines such as Lyα (at 1215.67 Å). It is worth noting that TW Hya is brighter than AB Aurigae in the Lyα line and that in TW Hya the fraction of flux emitted in Lyα is about 30 % of the total flux emitted in the 910-2400 Å wavelength range. We also note that while the FUV spectra of AB Aurigae is similar to that of a 10,000 K blackbody, a 4000 K blackbody is a bad approximation for a T Tauri star as it completely misses the FUV excess. As will be discussed in Sec. 4, this has important consequences for the chemistry of the disk.

Fig. 1.

Stellar FUV flux at 1 au of the T Tauri star (emitting as TW Hya and as a 4000 K blackbody) and of the Herbig Ae/Be star (emitting as AB Aurigae and as a 10,000 K blackbody).

2.1.2. Dust and gas temperature

Given the input parameters characteristic of the star (M*, R*, and stellar spectrum), the radial distribution of surface density in the disk given by Eq. (1), the dust-to-gas mass ratio, and the dust properties, we solve for the two dimensional distribution of the dust temperature in the disk using the RADMC code (Dullemond & Dominik 2004)2. RADMC is a two dimensional Monte Carlo code that solves the dust continuum radiative transfer in circumstellar disks and yields the dust temperature as a function of radius r and height z over the midplane. The vertical distribution of the volume density of particles n(z) is assumed to be given by hydrostatic equilibrium as

| (5) |

where μ is the mean mass of particles, G the gravitational constant, k the Boltzmann constant, and Td(z) is the vertical distribution of dust temperature. We proceed iteratively to find n(z) at each radius r according to Eq. (5) and consistently with the vertical distribution of dust temperature Td(z) computed at each radius r.

We assume that gas and dust are thermally coupled, i.e., gas and dust temperatures are equal, except for the disk surface. Models dealing with the computation of the gas temperature in protoplanetary disks find that the thermal coupling of gas and dust is a good approximation over most of the disk and that this assumption breaks down at the surface layers of the disk, where the visual extinction AV in the vertical outward direction becomes lower than ~1 (Kamp & Dullemond 2004; Woitke et al. 2009; Walsh et al. 2010). In these surface layers the gas can be much warmer than dust grains. In order to take this into account we use the following approximation for the gas temperature. We assume that the gas temperature is equal to the dust temperature in those regions where AV in the vertical outward direction is higher than 1. Following the study by Kamp & Dullemond (2004), we assume that in the uppermost regions of the disk, where AV < 0.01, the gas temperature is equal to the evaporation temperature of a hydrogen atom, calculated as the temperature at which the most probable speed of particles equals the escape velocity from the disk, i.e.,

| (6) |

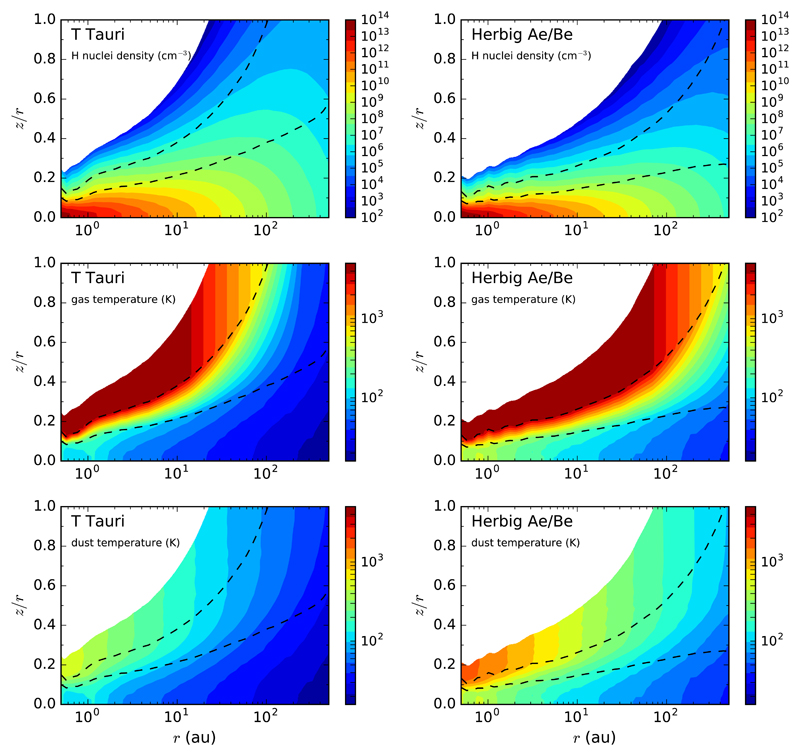

where mH is the mass of a hydrogen atom. Finally, at regions intermediate between AV = 1 and AV = 0.01 we approximate the gas temperature through a linear interpolation with height. In Fig. 2 we show the two dimensional distributions of the volume density of particles and of the gas and dust temperatures calculated for the disks around the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars. The flared shape, which is apparent in both disks, is more prominent in the T Tauri disk owing to the lower gravity of the star. The most significant difference between the physical structure of both disks is that the disk around the Herbig Ae/Be star is significantly warmer than the disk around the T Tauri star because of the higher stellar irradiation of the former.

Fig. 2.

Calculated volume density of H nuclei (top), gas temperature (middle), and dust temperature (bottom) as a function of radius r and height over radius z/r for the T Tauri (left) and Herbig Ae/Be (right) disks. The dashed lines indicate the location where AV in the outward vertical direction takes values of 0.01 and 1.

2.2. Chemical model

Once the physical structure of the disk (temperature of gas and dust and volume density of particles) is calculated at steady state, we solve for the temporal evolution of the chemical composition at each location in the disk. Since transport processes are neglected, each location in the disk evolve independently of other disk regions. We solve the chemical composition as a function of time up to 1 Myr, which is of the order of the typical ages of protoplanetary disks, for a grid consisting of 50 radii (logarithmically spaced from Rin to Rout) and 200 heights (generated specifically for each radius to properly sample the different regimes of AV in the vertical direction). The chemical network includes 252 species (97 neutral species, 133 positive ions plus the negative ion H− and free electrons, and 20 ice molecules) involving the elements H, He, C, N, O, S, Cl, and F. Atoms of Si, P, Fe, Na, and Mg are also included because their ionized forms are important in controlling the degree of ionization in certain disk regions. We adopt as initial chemical composition that calculated with a pseudo-time-dependent chemical model (where the chemical evolution is solved under fixed physical conditions) of a cold dense cloud with standard parameters (density of H nuclei of 2×104 cm−3, temperature of 10 K, visual extinction of 10 mag, and cosmic-ray ionization rate of H2 of 5 × 10−17 s−1) at a time of 0.1 Myr. The elemental abundances adopted, based in the so-called ”low metal” case (e.g., Graedel et al. 1982; Lee et al. 1998), are listed in Table 3 of Agúndez & Wakelam (2013). The chemical network comprises 5533 processes including gas phase chemical reactions, cosmic-ray induced processes, photodissociations and photoionizations due to stellar and interstellar FUV photons, and exchange processes between the gas and ice mantle phases (adsorption and desorption). At this stage, the model does not include X-ray induced processes and grain-surface reactions, except for the formation of H2. X rays may be an important source of chemical differentiation between disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars because the former are more important X-ray emitters (see, e.g., Telleschi et al. 2007). Moreover, winds and magnetic fields in actively accreting T Tauri systems may lead to cosmic-ray exclusion so that ionization in the disk can be dominated by X rays rather than cosmic rays (Cleeves et al. 2015). Therefore, it will be interesting to study the impact of X rays on the chemistry of the two types of disks in the future. In any case, previous chemical models of T Tauri disks have found that the gas-phase chemistry is not greatly affected by X rays. The species whose abundance is most affected are, according to Aresu et al. (2011), the ions present in the disk surface OH+, H2O+, H3O+, and N+, while Walsh et al. (2012) find that N2H+ is the most sensitive species to X rays. We however note that the models of Aresu et al. (2011) and Walsh et al. (2012) did not consider cosmic-ray exclusion, unlike the study of Cleeves et al. (2015). Chemical reactions occurring on the surface of dust grains are likely to have an effect on the chemical composition of cool midplane regions, especially regarding complex organic molecules (Walsh et al. 2014), although the distribution of abundant molecules and the main chemical patterns in the disk are probably not very much affected by such processes. We also plan to investigate this particular aspect in the future.

2.2.1. Gas phase chemical reactions

The vast majority of gas phase chemical reactions included can be grouped into two main categories: ion-neutral reactions and neutral-neutral reactions. The subset of ion-neutral reactions has been constructed based on databases originally devoted to the study of the chemistry of cold interstellar clouds, such as the UMIST database for astrochemistry (Woodall et al. 2007; McElroy et al. 2013)3 and the Ohio State University (OSU) database, formerly maintained by E. Herbst and currently integrated into the Kinetic Database for Astrochemistry (KIDA; Wakelam et al. 2012, 2015)4. Rate constants of ion-neutral reactions have been taken from the previous databases and from the literature on chemical kinetics. In particular, a large part of the rate constants has been revised according to the compilation by Anicich (2003)5. The chemical kinetics of exothermic ion-neutral reactions is rather simple because in most cases the kinetics is dominated by long range electrostatic forces. In the case of reactions in which the neutral species is non polar the theory indicates that the rate constant is independent of temperature and is given by the Langevin value. If the neutral species has an electric dipole moment the expression found by Su & Chesnavich (1982) can be used to evaluate the rate constant and its dependence with temperature (Maergoiz et al. 2009; see more details in Wakelam et al. 2010). For ion-non polar reactions for which there is no experimental data, the rate constant has been approximated as the Langevin value. In the case of ion-polar reactions, we have used the Su-Chesnavich approach to evaluate the rate constant of reactions not studied experimentally and to obtain the temperature dependence of the rate constant of reactions which have been only characterized at one single temperature, usually around 300 K.

The part of the chemical network involving ions includes also dissociative recombinations of positive ions with electrons and radiative recombinations between cations and electrons. The set of reactions and associated rate constants have been mainly taken from databases such as UMIST (Woodall et al. 2007; McElroy et al. 2013) and KIDA (Wakelam et al. 2012, 2015). Information on the chemical kinetics of dissociative recombinations has largely benefited from experiments carried out with ion storage rings (Florescu-Mitchell & Mitchell 2006; Geppert & Lasson 2008).

The subset of neutral-neutral reactions has been constructed from chemical kinetics databases, such as the one by NIST (Manion et al. 2013)6, databases devoted to the study of interstellar chemistry, such as UMIST (Woodall et al. 2007; McElroy et al. 2013) and KIDA (Wakelam et al. 2012, 2015), compilations for application in atmospheric chemistry, such as the evaluations by IUPAC (Atkinson et al. 2004, 2006)7 and JPL (Sander et al. 2011)8, and compilations for use in combustion chemistry, such as the IUPAC evaluation by Baulch et al. (2005) and the Leeds methane oxidation mechanism (Hughes et al. 2001) or the mechanism by Konnov (2000). A good number of reaction rate constants have been taken from specific experimental and theoretical studies found in the literature on chemical kinetics. For example, we have included the numerous measurements at low and ultra low temperatures carried out with the CRESU apparatus (Smith et al. 2006). It is important to note that some regions of protoplanetary disks may have temperatures up to some thousands of degrees Kelvin and therefore it is necessary to include reactions that become fast at high temperatures, i.e., reactions which are endothermic and/or have activation barriers. Chemical kinetics data for such reactions are to a large extent based on chemical networks used in previous chemical models of warm gas in protoplanetary nebulae (Cernicharo 2004) and inner regions of protoplanetary disks (Agúndez et al. 2008), whose original sources of data are mainly the combustion chemistry databases listed above. A similar high temperature chemical network has also been used by Harada et al. (2010) to model the chemistry of active galactic nuclei of galaxies. We include also three body reactions and their reverse process (thermal dissociation) with H2, He, and H acting as third body. Three body reactions become important at densities above ~1010 cm−3, values that are reached in the innermost midplane regions of protoplanetary disks, while thermal dissociations become important at high temperatures. We use an expanded version of the set of three body reactions and thermal dissociations compiled by Agúndez & Cernicharo (2006). An important aspect of the neutral-neutral subset of reactions is that for many of the endothermic reactions for which chemical kinetics data are not available the rate constants have been calculated through detailed balance from the rate constant of the reverse exothermic reaction and the thermochemical properties of the species involved. Thermochemical data in the form of NASA polynomial coefficients (McBride et al. 2002) have been obtained from compilations like those by Konnov (2000) and Burcat & Ruscic (2005)9.

2.2.2. Cosmic-ray induced processes

The processes induced by cosmic rays play also an important role in the chemistry of protoplanetary disks. We include the direct ionization of H2 and atoms by cosmic-ray impact, together with photoprocesses induced by secondary electrons produced in the direct ionization of H2, the so-called Prasad-Tarafdar mechanism (Prasad & Tarafdar 1983; Gredel et al. 1989). The rates of these processes are expressed in terms of the cosmic-ray ionization rate of H2 (ζ), for which we adopt a value of 5 × 10−17 s−1 (see Table 1), and are taken from astrochemical databases such as UMIST (Woodall et al. 2007; McElroy et al. 2013) and KIDA (Wakelam et al. 2012, 2015).

2.2.3. Photoprocesses

Photodissociation and photoionization processes caused by stellar and interstellar FUV photons are a key aspect of the chemistry of protoplanetary disks as they control the chemical composition of the surface layers, from where much of the molecular emission arises. In order to treat in detail these processes we have used the Meudon PDR code (Le Petit et al. 2006; Goicoechea & Le Bourlot 2007; González García et al. 2008)10, where PDR stands for photodissociation region, to compute the photodissociation and photoionization rates of various important species at each location in the disk. We use the version 1.4 of the Meudon PDR code, with some practical modifications to make it more versatile and integrate it into the protoplanetary disk model. The Meudon PDR code solves the FUV radiative transfer in one dimension for a plane-parallel cloud illuminated on one side by a FUV source. In protoplanetary disks the geometry involves two dimensions (radial and vertical) and there are two different FUV sources, the star illuminating from the central position and the interstellar radiation field illuminating isotropically from outside the disk. We thus adopt a 1+1D approach. On the one hand we solve the radiative transfer of FUV interstellar radiation as it propagates from outside the disk to the midplane along a series of vertical directions located at the different radii of the grid described in Sec. 2.2. On the other hand we solve the radiative transfer of FUV stellar radiation as it travels from the star through the disk along a series of directions given by a grid of 200 angles from the midplane (covering the range from 0° to almost 90°). The Meudon PDR code assumes that stellar photons arrive from a direction perpendicular to the plane-parallel surface of the cloud. In disks, the star may illuminate the disk with small grazing angles, in particular in the inner regions where the flaring shape of the disk is less marked. It is thus likely that when computing the FUV energy density along the different directions from the star, at low penetration depths the Meudon PDR code underestimates the contribution of FUV photons scattered by dust from nearby regions around the disk surface. However, it is not straightforward to properly correct by this geometrical effect without moving to 2D and thus we do not apply any specific correction for it here.

In summary, once the physical structure of the disk is calculated at steady state (using the RADMC code as described in Sec. 2.1) and prior to the computation of the temporal evolution of the chemical composition, we use the Meudon PDR code to evaluate the photodissociation and photoionization rates at each location in the disk by calculating the FUV flux as a function of wavelength due to stellar and interstellar radiation and using the relevant wavelength-dependent cross sections. Our approach to treat photochemistry is thus different from other state-of-the-art chemical models of protoplanetary disks in which the FUV radiative transfer is solved in 2D but only in a few broad spectral bands (e.g., Woitke et al. 2016) and it is in essence more similar to the series of models by Walsh et al. (2012, 2014, 2015).

We have compiled cross sections for 29 molecules and 8 atoms (see Appendix A). The photodissociation rate of H2 and CO are computed by solving the excitation and the line-by-line radiative transfer taking into account self and mutual shielding effects. In the case of photoprocesses for which cross section data is not available we have approximated the rate using a parametric expression in which the rate Γ, in units of s−1, is expressed as a function of the visual extinction AV as

| (7) |

where χ is the FUV11 energy density with respect to that of the ISRF of Draine (1978), α is the rate under a given unattenuated radiation field with χ = 1, and the coefficient γ controls the decrease in the rate with increasing visual extinction. The coefficients α and γ are specific of each photoprocess and depend also on the spectral shape of the FUV field. Values of α and γ corresponding to the ISRF have been taken from the databases such as the UMIST database for astrochemistry (Woodall et al. 2007; McElroy et al. 2013) and the OSU and KIDA databases (Wakelam et al. 2012, 2015), as well as from the compilation by van Dishoeck et al. (2006), recently revised by Heays et al. (2017).

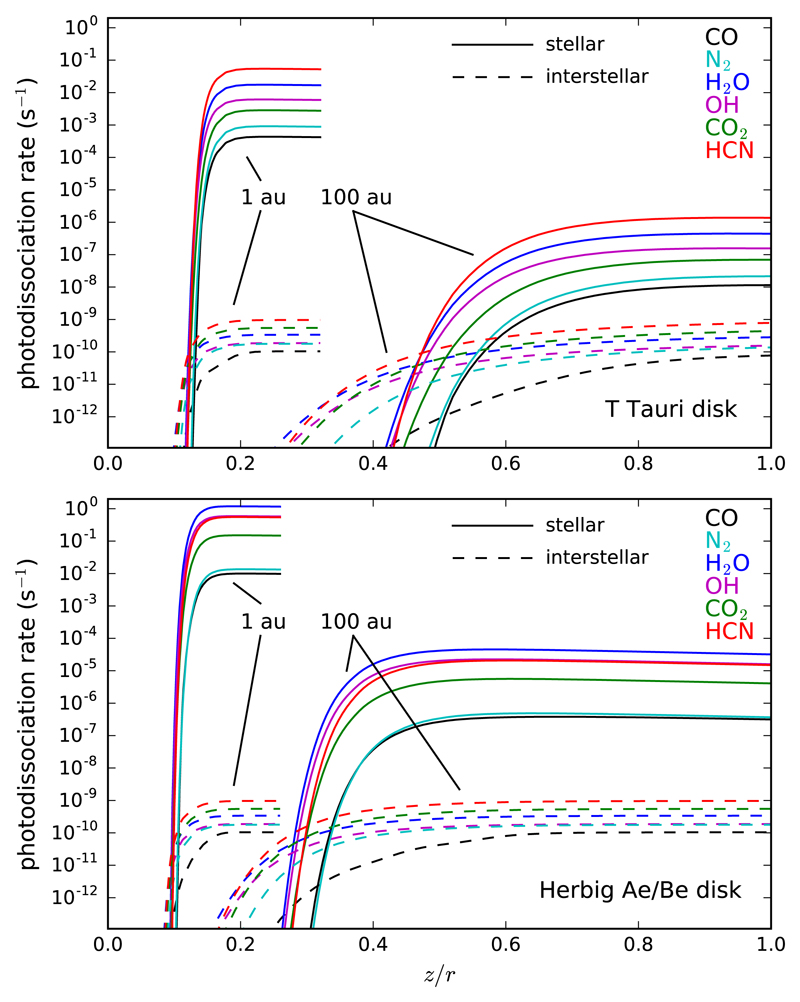

In Fig. 3 we show the contribution of the stellar and interstellar radiation fields to the photodissociation rate of various molecules as a function of height over the disk midplane. This is shown at two radial distances from the star (1 au and 100 au) for the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks. We see that in the uppermost regions of the disk, photoprocesses are clearly dominated by the stellar radiation field. However, as we go deeper into the disk, at some point the contribution of the ISRF becomes more important than the stellar one because of the more marked increase of the visual extinction against stellar light than against interstellar photons. Therefore, depending on the location in the disk, photodestruction can be driven by the ISRF or by the star.

Fig. 3.

Contribution of the stellar (solid lines) and interstellar (dashed lines) FUV fields to the photodissociation rates of various molecules as a function of the height over radius (z/r) at 1 au and 100 au in the T Tauri (upper panel) and Herbig Ae/Be (lower panel) disks.

2.2.4. Reactions with vibrationally excited H2

In the disk surface the gas is strongly illuminated by FUV photons and vibrationally excited states of molecular hydrogen are easily populated through FUV fluorescence. Since the reactivity of H2 can be quite different when it is in the ground or in excited vibrational states –the internal energy of H2 can be used to overcome or diminish endothermicities or activation barriers which are present when H2 is in its ground vibrational state– we have included a few reactions of H2 with specific rate constants for each vibrational state. Concretely, we have included the reactions of H2 with C+ (important in the formation of CH+), He+, O, OH, and CN, with the rate constant expressions compiled by Agúndez et al. (2010), and the reaction of H2 and S+, which may be important in the synthesis of the ion SH+, with the rate constant expressions calculated by Zanchet et al. (2013). The populations of the different vibrational states of H2 are computed at each location in the disk with the Meudon PDR code.

2.2.5. Adsorption processes

The adsorption of gas species onto the surface of dust grains is treated in a rather simple and standard way. The adsorption rate of a gas species i, in units of s−1, is given by

| (8) |

where αi and νi are the sticking coefficient and thermal velocity of each gas species i. The sticking coefficient is assumed to be 1 for all species and the thermal velocity is evalued as where Tk is the gas kinetic temperature and mi is the mass of each gas species i. The term 〈σdnd〉 is the product of the geometric cross section and the volume density of dust particles averaged over the grain size distribution given by Eq. (2) and is evaluated following the formalism of Le Bourlot et al. (1995). To simplify, we only consider adsorption of a limited number of stable neutral species, among which there are the most typically abundant ice constituents (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Ice species, binding energies, and photodesorption yields.

| Species | ED (K) | Ref. | Y (molecule photon−1) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | 1000 | (1) ◊ | 10−3 | (11) |

| C2H2 | 2587 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| C2H4 | 3487 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| C2H6 | 4387 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| H2O | 5773 | (3) ◊ | (1.3 + 0.032 Td) × 10−3 | (12) * |

| O2 | 1161 | (4) † ♮ | (2.8a, 2.3b, 2.4c) × 10−3 | (13) § |

| CO | 1575 | (5) † ♮ | (9.5a, 4.8b, 10.3c) × 10−3 | (14) § |

| CO2 | 2346 | (4) † ♮ | (8.2a, 2.0b, 0.98c) × 10−4 | (15) § * |

| H2CO | 3260 | (6) † | 10−3 | (11) |

| CH3OH | 4990 | (7) ◊ | (1.5a, 1.1b, 1.3c) × 10−4 | (16) § * |

| HCOOH | 5570 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| NH3 | 3830 | (1) ◊ | 10−3 | (11) |

| N2 | 1435 | (5) † ♮ | (2.0a, 1.6b, 0.89c) × 10−3 | (13) § |

| HCN | 2050 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| H2S | 1945 | (8) ♯ | 10−3 | (11) |

| CS | 1900 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| H2CS | 2700 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| SO | 2600 | (2) ‡ | 10−3 | (11) |

| SO2 | 3900 | (9) † | 10−3 | (11) |

| OCS | 3440 | (10) ◊ | 10−3 | (11) |

Notes.– ◊ pure ice; † amorphous water ice substrate (♮ submonolayer regime); ♯ solid SO2 substrate; ‡ estimated for water ice substrate; § wavelength-dependent photodesorption yield is convolved over the 7-13.6 eV range with the interstellara, T Taurib, and Herbig Ae/Bec FUV radiation fields described in section 2.1.1; * yields of direct photodesorption and fragmentation have been measured.

References.– (1) Luna et al. (2014); (2) Garrod & Herbst (2006); (3) Fraser et al. (2001); (4) Noble et al. (2012a); (5) Fayolle et al. (2016); (6) Noble et al. (2012b); (7) Doronin et al. (2015); (8) Sandford & Allamandola (1993); (9) Schriver-Mazzuoli et al. (2003), assuming that ED is directly proportional to the desorption temperature (see, e.g., Martín-Doménech et al. 2014); (10) Burke & Brown (2010); (11) assumed; (12) pure H2O ice (> 8 ML) in the 18-100 K range; the fraction of H2O molecules photodesorbed is (0.42 + 0.002 Td), the remaining results in fragmentation into OH + H (Öberg et al. 2009); (13) pure O2 (30 ML) and 15N2 (60 ML) ices at 15 K (Fayolle et al. 2013); (14) pure CO ice (10 ML) at 18 K (Fayolle et al. 2011); (15) pure 13CO2 (10 ML) ice at 10 K; the fraction of CO2 molecules desorbed is 0.37, 0.42, and 0.22 under the interstellar, T Tauri, and Herbig Ae/Be FUV fields, respectively, the remaining results in fragmentation into CO + O (Fillion et al. 2014); (16) pure CH3OH (20 ML) ice at 10 K; the fraction of CH3OH molecules desorbed is 0.08, while the fragmentation channels CH3 + OH, H2CO + H2, CO + H2 + H2 occur with fractions of 0.05, 0.07, and 0.80, almost independently of the radiation field (Bertin et al. 2016; see also Cruz-Diaz et al. 2016).

2.2.6. Desorption processes

Species which have been adsorbed on dust grains forming ice mantles can return to the gas phase through a variety of desorption mechanisms. In protoplanetary disks, the most important desorption processes are thermal desorption and photodesorption by FUV photons. We also include desorption induced by cosmic rays. Based on the results of experimental work using isotopic markers (Bertin et al. 2012, 2013) and molecular dynamics calculations (Andersson & van Dishoeck 2008), we consider that only molecules from the top two monolayers can desorb efficiently (Nl = 2). The term due to desorption can therefore be written in the kinetic rate equations as

| (9) |

where ni and are the volume densities of species i in the gas and ice phases, respectively, are the desorption rates, in units of s−1, of thermal desorption, photodesorption, and desorption induced by cosmic rays, respectively (see below). The quantity is the volume density of species i in the top desorbable ice layers, which is simply equal to when these layers are not fully occupied while it is given by multiplied by the factor otherwise. The volume density of sites in the top desorbable layers ntop is given by ns4〈σdnd〉Nl (where ns is the surface density of sites, typically ~ 1.5 × 1015 cm−2; see Hasegawa et al. 1992) and is the sum of the volume densities of all ice species, i.e., This implementation of desorption in the kinetic rate equations is similar to that of, e.g., Aikawa et al. (1996) and Woitke et al. (2009); see also Cuppen et al. (2017).

– Thermal desorption. This process, which depends on the dust temperature Td and the binding energy of adsorption of each species ED, controls to a large extent the distribution of ices in protoplanetary disks and the location of the different snow lines of each molecule. The thermal desorption rate, in units of s−1, of an adsorbed species i is given by

| (10) |

where ν0,i is the characteristic vibration frequency of the adsorbed species i (evaluated as where the binding energy ED,i is expressed in units of K. Binding energies have been measured in the laboratory by depositing volatile species on different cold substrates and using temperature programmed desorption methods (see Burke & Brown 2010 and references therein). In general, binding energies show little dependence with the chemical or morphological nature of the substrate as long as the ice under study consists of various monolayers (ML). If desorption occurs at submonolayer coverage, desorption energies can be quite different depending on the substrate, e.g., they tend to be higher if employing water ice as substrate than using silicates (Noble et al. 2012a). The translation of these laboratory experiments into a realistic model of thermal desorption in protoplanetary disks is complicated because ices are heterogeneous mixtures, thought to be dominated by water ice but whose composition probably varies between cold and warmer regions. Also, molecules may selectively co-desorb with other trapped species, experience volcano desorption following the crystallization of water ice, or co-desorb with some of the major ice constituents (Collings et al. 2004). Here we have adopted the simple and usual approach in which the thermal desorption of each species is controlled by a specific binding energy. We have collected values of ED experimentally measured, when possible using a water ice substrate and under a submonolayer regime. For those molecules for which experimental binding energies are not available, we have adopted the values estimated by Garrod & Herbst (2006) for a water ice substrate based on the previous compilation by Hasegawa et al. (1993) and the experimental study of Collings et al. (2004). The binding energies of the ice molecules considered and the corresponding references are given in Table 2.

– Photodtsorption. The absorption of FUV photons of stellar or interstellar origin (or generated through the Prasad-Tarafdar mechanism) by icy dust grains can induce the desorption of molecules on the ice surface. In regions where the dust temperature is too cold to allow for thermal desorption, photodesorption can provide an efficient means to bring ice molecules to the gas phase. The photodesorption rate, in units of s−1, of an adsorbed species i is given by

| (11) |

where Yi is the yield of molecules desorbed per incident photon, FFUV is the FUV photon flux (in units of photon cm−2 s−1), and the expression of when inserted in Eq. (9), naturally accounts for the fact that ices are not pure but consist of multiple constituents and that desorption is only effective from the top desorbable layers (see, e.g., Cuppen et al. 2017). FUV photons may have an stellar or interstellar origin (in which case FFUV is evaluated with the Meudon PDR code at each position in the disk) or can be generated through the Prasad-Tarafdar mechanism, in which case we adopt FFUV = 2 × 103 photon cm−2 s−1 (values between 750 and 104 photon cm−2 s−1 have been reported in the literature; e.g., Hartquist & Williams 1990; Shen et al. 2004). Note that this latter value scales with the cosmic-ray ionization rate. Experiments carried out to study the photodesorption of pure ices or binary ice mixtures (Öberg et al. 2009; Muñoz Caro et al. 2010; Fayolle et al. 2011, 2013; Bertin et al. 2013; Fillion et al. 2014; Martín-Doménech et al. 2015) suggest that the main underlying mechanism, called desorption induced by electronic transition (DIET), involves absorption of FUV photons in the ~ 5 top monolayers and electronic excitation of the absorbing molecules, followed by energy redistribution to neighbouring molecules, which may break their intermolecular bonds and be ejected into the gas phase. The efficiency of photodesorption is thus regulated by the ability of the molecules present in the ice surface and sub-surface to absorb FUV photons through electronic transitions. If these transitions are dissociative the situation becomes more complex because the fragments may desorb directly, recombine in the ice and then desorb, or diffuse through the ice forming new molecules that may also desorb (e.g., Andersson & van Dishoeck 2008). Here we adopt a simple approach in which ice molecules may desorb directly or as fragments upon FUV irradiation, with yields based on experimental data for CO, N2, O2, H2O, and CO2 (see Table 2). Desorption of fragments has been observed upon irradiation of pure ices of H2O, CO2, and CH3OH (Öberg et al. 2009; Fillion et al. 2014; Martín-Doménech et al. 2015; Bertin et al. 2016; Cruz-Diaz et al. 2016), and it is likely that desorption of dissociation fragments and new species formed in situ in the ice dominates over direct desorption for other polyatomic molecules. However, in the absence of experimental photodesorption yields for molecules other than CO, N2, O2, H2O, CO2, and CH3OH we have assumed that direct desorption dominates with assumed values for Yi. It is interesting to note that photodesorption yields of CO, O2, N2, CO2, and CH3OH have been measured as a function of wavelength using synchrotron techniques (Fayolle et al. 2011, 2013; Fillion et al. 2014; Bertin et al. 2016), which permits to compute the yield Yi under different FUV fields (see values for the ISRF and the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stellar radiation fields in Table 2). Note for example that the photodesorption yield of CO2 is almost one order of magnitude higher under the ISRF than under a Herbig Ae/Be stellar field.

- Cosmic-ray induced desorption. This mechanism is driven by the impact of cosmic rays on dust grains. The energy deposited on dust grains upon impact of relativistic heavy nuclei of iron results in a local heating that induces the thermal desorption of the ice molecules present in the heated region. According to Hasegawa et al. (1993), the desorption rate induced by cosmic rays, in units of s−1, of a species i is given by

| (12) |

where the numerical factor stands for the fraction of the time spent by grains in the vicinity of a temperature of 70 K, at which much of the desorption is assumed to occur in the formalism of Hasegawa et al. (1993), and is derived adopting the Fe cosmic ray flux estimated by Léger et al. (1985) for the local interstellar medium and dust grains with a radius of 0.1 μm. The term (70 K) is the rate of thermal desorption of species i, given by Eq. (10), evaluated at 70 K. The desorption rate scales with the cosmic-ray ionization rate.

2.2.7. Formation of H2 on grain surfaces

The kinetics of H2 formation on grain surfaces in interstellar space is usually described as

| (13) |

where nH is the volume density of H nuclei, n(H) and n(H2) are the volume densities of neutral H atoms and H2 molecules, and Rf is the formation rate parameter for which usually the canonical value of 3 × 10−17 cm3 s−1 derived by Jura (1975) for diffuse interstellar clouds is adopted. Here, we evaluate Rf as

| (14) |

where νH is the thermal velocity of H atoms, evaluated as The sticking coefficient of H atoms SH depends on the gas kinetic temperature Tk and is evaluated through the expression

| (15) |

where we have adopted S0 = 1, T0 = 25 K, and β = 2.5, based on the experimental study carried out by Chaabouni et al. (2012) for a silicate surface. The recombination efficiency ϵH2 in Eq. (14) depends on the dust temperature Td according to the expression derived by Cazaux & Tielens (2002a,b) and is evaluated with the parameters provided by Cazaux & Tielens (2002a) in their Table 1, with an updated value of 12,200 K for the desorption energy of chemisorbed H, as calculated by Goumans et al. (2009) for an olivine surface. Currently, the kinetics of grain-surface H2 formation considered in the model accounts for the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism. In the future it will be worth to consider also the Eley-Rideal mechanism, which is expected to increase the H2 formation efficiency at high gas temperatures (e.g., Le Bourlot et al. 2012; Bron et al. 2014).

3. Results

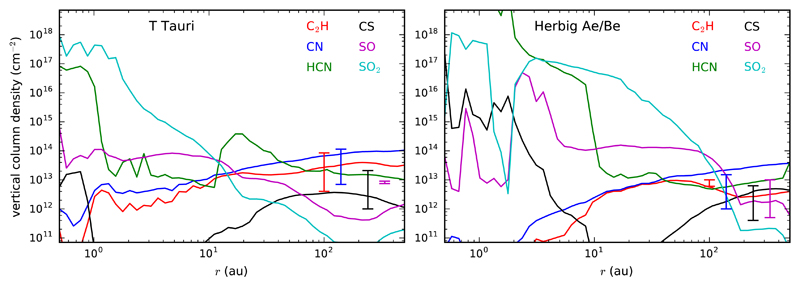

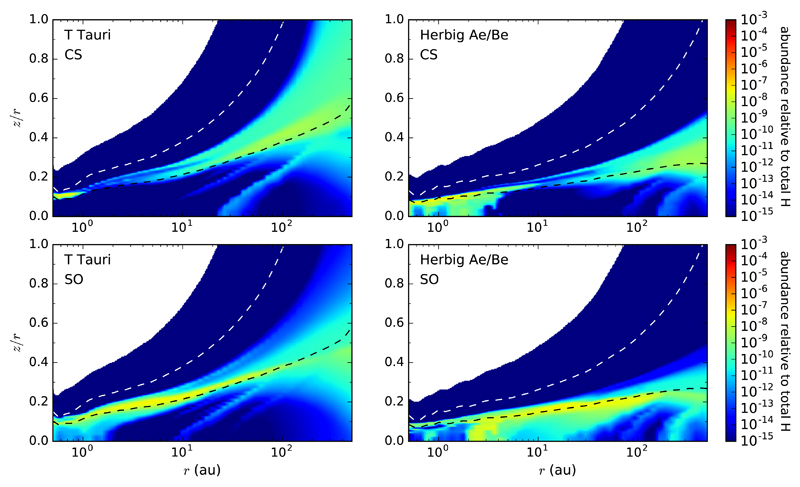

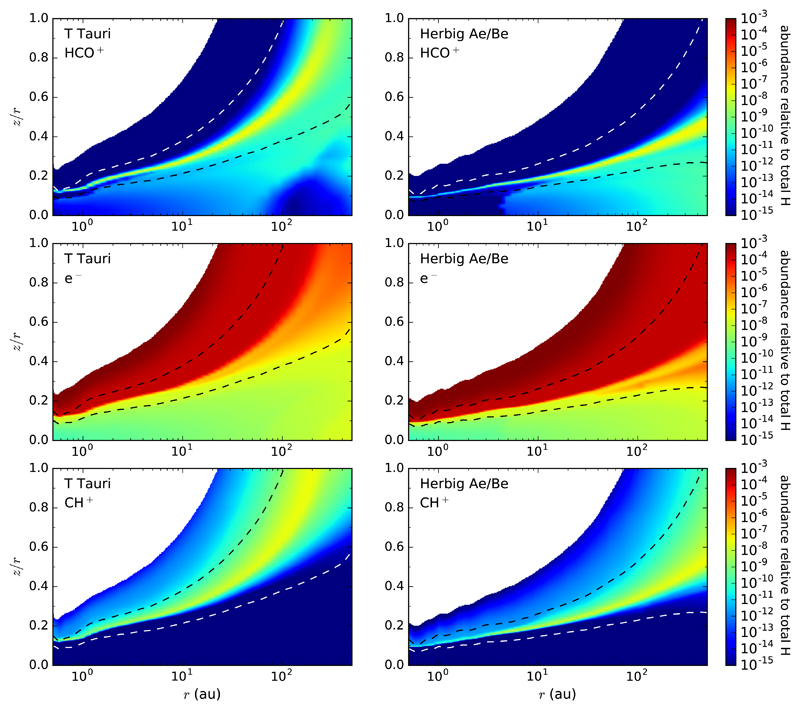

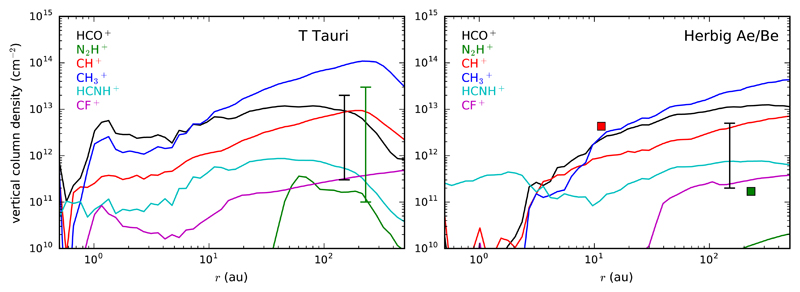

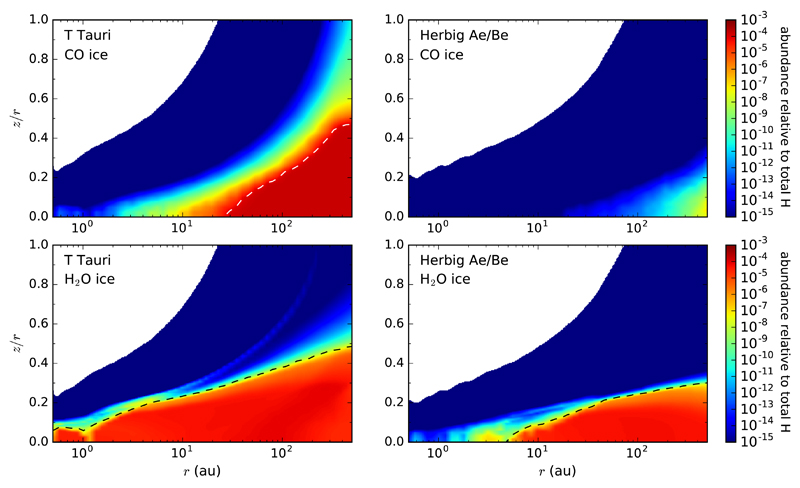

In this section we present the calculated abundance distributions of various molecules in our fiducial T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disk models, and compare them with available constraints from observations, with the stress put on the similarities and differences between both types of disks. We focus on molecules that have been observed in disks at IR or (sub-)mm wavelengths. Detected species in disks have been summarized by Dutrey et al. (2014). In Table 3 we provide an updated an comprehensive summary of the molecules observed in T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks. We first concentrate on molecules observed through IR observations, which are sensitive to the hot inner disk: H2O and OH (Sec. 3.1), and simple organics such as C2H2, HCN, CH4, and CO2 (Sec. 3.2). We then focus on molecules observed at (sub-)mm wavelengths, which trace the outer disk: the radicals C2H and CN (Sec. 3.3) and other organic molecules with a certain complexity, such as H2CO (Sec. 3.4), the sulfur-bearing molecules CS and SO (Sec. 3.5), and molecular ions (Sec. 3.6). We finally discuss the abundance distributions of ices, for which most observational constraints consist of determining the location of the CO snowline (Sec. 3.7). Abundances are mostly expressed as column densities because this is the quantity provided by most observational studies. Nonetheless, sometimes we use the term fractional abundance, which hereafter refers to the abundance relative to the total number of H nuclei.

Table 3.

Summary of molecules (other than H2 and CO) observed in disks and abundances derived.

| Species | Spectral signature, region probed | Detection rate, abundance, and references | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T Tauri | Herbig Ae/Be | ||||

| H2O | IR emission, inner atmosphere | many disks (0.4 − 800) × 1018 cm−2 |

(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11) (6,7) |

one disk: HD 163296 1014 − 1015 cm−2 |

(4,7,11,12,13,14,15) (14) |

| sub-mm emission, outer disk | two disks: TW Hya, DGTau ~ 10−7 relative to H2 |

(16,17,18) (16) |

one disk: HD 100546 | (18,19) | |

| OH | IR emission, inner atmosphere | many disks (0.4 − 200) × 1015 cm−2 |

(2,3,4,6,7,8,11,15,20) (6,7) |

a dozen of disks (0.01 − 200) x 1015 cm−2 |

(4,7,11,12,21) (12,15,21) |

| C2H2 | IR emission/absorption, inner disk | many disks (0.5 − 70) × 1015 cm−2 |

(2,6,7,8,22,23,24) (6,7,22,23,24) |

none | |

| HCN | IR emission/absorption, inner disk | many disks (0.5 − 65) × 1015 cm−2 |

(2,6,7,8,22,23,24) (6,7,22,23,24) |

none | |

| mm emission, outer disk | many disks (0.2 − 10.6) × 1012 cm−2 |

(27,28,29,30,31,32,33,35) (28,31,32,33) |

many disks (0.1 − 1) × 1012 cm−2 |

(28,29,30,31,32,33,34) (31,33,34) |

|

| HNC | mm emission, outer disk | two disks: DM Tau, TW Hya HNC/HCN = 0.3-0.4 |

(27,36) (27) |

one disk: HD 163296 HNC/HCN = 0.1 − 0.2 |

(36) (36)a |

| CH4 | IR absorption, inner disk | one disk: GV Tau 2.8 × 1017 cm−2 |

(25) (25) |

none | |

| CO2 | IR emission/absorption, inner disk | many disks (0.04 − 10) × 1016cm−2 |

(6,7,22,24,26) (7,22,24,26) |

one disk: HD 101412 1016 cm−2 |

(7) (7) |

| C2H | mm emission, outer disk | many disks (0.4 − 8.5) × 1013cm−2 |

(27,32,33,37,38) (33,37)b |

two disks: AB Aur, MWC 480 (0.6 − 1) × 1013 cm−2 |

(33,34,37,39,40) (33) |

| CN | mm emission, outer disk | many disks (0.7 − 11.5) × 1013 cm−2 |

(27,28,29,30,31,32,33) (28,31,32,33) |

a handful of disks (0.1 − 1.5) × 1013 cm−2 |

(28,29,30,31,33,34) (28,31,33,34) |

| H2CO | mm emission, outer disk | a dozen of disks (0.9 − 4.4) × 1012 cm−2 |

(27,28,29,30,33,41,43,44) (33)c |

a handful of disks (1.6 − 3.3) × 1012 cm−2 |

(30,33,34,42,45,46) (33)d |

| CH3OH | mm emission (ALMA), outer disk | one disk: TW Hya; (3 − 6) × 1012 cm−2 | (47) | none | |

| HC3N | mm emission, outer disk | two disks: GO Tau, LkCa 15; ~ 1012 cm−2 | (48) | one disk: MWC 480; ~ 1012 cm−2 | (48,49) |

| CH3CN | mm emission (ALMA), outer disk | none | one disk: MWC 480; ~ 1013 cm−2 | (49) | |

| c-C3H2 | mm emission (ALMA), outer disk | one disk: TW Hya | (38) | one disk: HD 163296; 1012 − 1013 cm−2 | (50) |

| NH3 | sub-mm emission, outer disk | one disk: TW Hya (0.2 − 17) × 10−11 relative to H2 |

(51) (51) |

none | |

| CS | mm emission, outer disk | a dozen of disks (1 − 20.9) × 1012 cm−2 |

(27,32,33,52) (32,33,52) |

two disks: AB Aur, MWC 480 (0.4 − 6.3) × 1012cm−2 |

(33,34,40) (33,34) |

| SO | mm emission, outer disk | two disks: CI Tau, GM Aur (7.4 − 9) × 1012 cm−2 |

(33) (33) |

one disk: AB Aur (0.5 − 10) × 1012 cm−2 |

(33,34,40,42) (33,34,42) |

| HCO+ | mm emission, outer disk | many disks (0.3 − 20) × 1012 cm−2 |

(28,29,30,33,35,53,54,55) (28,33,53,54,55) |

many disks (0.2 − 5) × 1012 cm−2 |

(28,29,30,33,34,54,56) (28,33,34,54)e |

| N2H+ | mm emission, outer disk | a handful of disks (0.1 − 30) × 1012 cm−2 |

(29,30,44,53,54,57) (53,54)f |

one disk: HD 163296 1.7 × 1011 cm−2 |

(45) (45) |

| CH+ | sub-mm emission, mid disk | none | two disks: HD 100546, HD 97048 4.3 × 1012 cm−2 |

(15,58) (58)g |

|

References: (1) Carr et al. (2004); (2) Carr & Najita (2008); (3) Salyk et al. (2008); (4) Pontoppidan et al. (2010a); (5) Pontoppidan et al. (2010b); (6) Carr & Najita (2011); (7) Salyk et al. (2011); (8) Mandell et al. (2012); (9) Riviere-Marichalar et al. (2012); (10) Sargent et al. (2014); (11) Banzatti et al. (2017); (12) Fedele et al. (2011); (13) Meeus et al. (2012); (14) Fedele et al. (2012); (15) Fedele et al. (2013); (16) Hogerheijde et al. (2011); (17) Podio et al. (2013); (18) Du et al. (2017); (19) van Dishoeck et al. (2014); (20) Carr & Najita (2014); (21) Mandell et al. (2008); (22) Lahuis et al. (2006); (23) Gibb et al. (2007); (24) Bast et al. (2013); (25) Gibb & Horne (2013); (26) Kruger et al. (2011); (27) Dutrey et al. (1997); (28) Thi et al. (2004); (29) Öberg et al. (2010); (30) Öberg et al. (2011); (31) Chapillon et al. (2012a); (32) Kastner et al. (2014); (33) Guilloteau et al. (2016); (34) Fuente et al. (2010); (35) Fuente et al. (2012); (36) Graninger et al. (2015); (37) Henning et al. (2010); (38) Bergin et al. (2016); (39) Schreyer et al. (2008); (40) Pacheco-Vázquez et al. (2015); (41) Aikawa et al. (2003); (42) Pacheco-Vázquez et al. (2016); (43) Loomis et al. (2015); (44) Öberg et al. (2017); (45) Qi et al. (2013a); (46) Carney et al. (2017); (47) Walsh et al. (2016); (48) Chapillon et al. (2012b); (49) Öberg et al. (2015); (50) Qi et al. (2013b); (51) Salinas et al. (2016); (52) Dutrey et al. (2011); (53) Qi et al. (2003); (54) Dutrey et al. (2007); (55) Teague et al. (2015); (56) Mathews et al. (2013); (57) Qi et al. (2013c); (58) Thi et al. (2011).

Notes:

Values are line intensity ratios rather than abundance ratios.

Out of this range, Kastner et al. (2014) derive N(C2H) = 5.1 × 1015 cm−2 in TW Hya.

Out of this range, Aikawa et al. (2003) derive N(H2CO) = (7.2 − 19) × 1012 cm−2 in LkCa 15.

Carney et al. (2017) derive a H2CO abundance of (2 − 5) × 10-12 relative to H2 in HD 163296.

Out of this range, Mathews et al. (2013) derive N(HCO+) = 1.5 × 1014 cm−2 in HD 163296.

Out of this range, Qi et al. (2013c) derive N(N2H+) = 1014 − 1015 cm−2 in TW Hya.

In the same object, HD 100546, Fedele et al. (2013) derive N(CH+) = 1016 − 1017 cm−2 for an emitting area inner to 50-70 au.

3.1. Water and hydroxyl radical

In the last years, near-IR to sub-mm observations have provided important constraints on the presence of water and its related radical (OH) in protoplanetary disks. At near- and mid-IR wavelengths, the spectra of disks around T Tauri stars show emission of hot H2O and OH arising from the inner disk (< a few au) atmosphere (Carr et al. 2004; Carr & Najita 2008, 2011, 2014; Salyk et al. 2008, 2011; Pontoppidan et al. 2010a,b; Mandell et al. 2012; Sargent et al. 2014; Banzatti et al. 2017), while in disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars, emission by OH is relatively common but there is a striking lack of H2O emission (Mandell et al. 2008; Pontoppidan et al. 2010a; Fedele et al. 2011; Salyk et al. 2011; Banzatti et al. 2017). Far-IR observations with Herschel/PACS have essentially confirmed that the water detection rate is much higher in T Tauri disks than in disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars (Riviere-Marichalar et al. 2012; Meeus et al. 2012; Fedele et al. 2012, 2013). Therefore, infrared observations suggest that water could be intrinsically less abundant in disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars than around T Tauri stars. Such a trend is however not corroborated by our models.

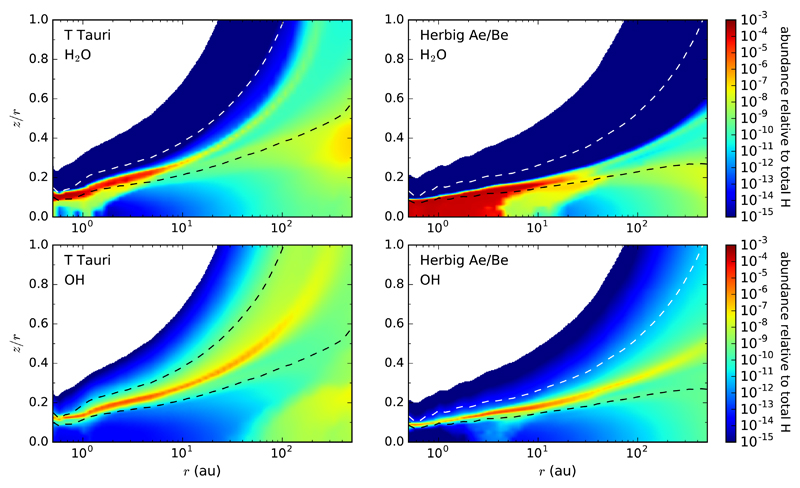

As can be seen in Fig. 4, in the T Tauri disk model, water is present with fractional abundances of ~10−4 in a surface layer at AV ~1 in the inner ~10 au from the star, while in the Herbig Ae/Be disk, the warmer temperatures make the region of high H2O abundance to extend radially beyond 10 au and vertically down to the midplane. In the inner disk, water becomes very abundant in regions warmer than ~200 K, where the reaction OH + H2 is activated, and sufficiently shielded from FUV photons, while OH is present in a thin layer on top of H2O resulting from its photodissociation. In our generic T Tauri disk model, the inner midplane regions are not warm enough to sustain a high water abundance, and thus most H2O (and all OH) are present in upper layers. We however note that the presence of water vapor in the inner midplane is very sensitive to the temperature and that other T Tauri disk models (e.g., Walsh et al. 2015) find high H2O abundances in these regions. Therefore, the model predicts that as the stellar luminosity increases and the disk becomes warmer water vapor is more abundant.

Fig. 4.

Calculated distributions of H2O and OH as a function of radius r and height over radius z/r for the T Tauri (left) and Herbig Ae/Be (right) disks. The dashed lines indicate the location where AV in the outward vertical direction takes values of 0.01 and 1.

The vertical column densities calculated for H2O and OH in the IR-observable atmosphere12 of the inner T Tauri disk are 1017-1018 cm−2 and ~1015 cm−2, respectively, which are in the low range of observed values (see left panel in Fig. 5). The calculated OH/H2O column density ratio in the inner disk, 10−2-10−3, is between the values derived in AA Tau, DR Tau, and AS 205A (0.1-0.3; Carr & Najita 2008; Salyk et al. 2008) and that found from a study of a much larger sample of T Tauri disks (~10−3; Salyk et al. 2011). Previous chemical models of inner T Tauri disks (Agúndez et al. 2008; Walsh et al. 2015) find H2O and OH column densities and ratios of the same order of magnitude than the ones calculated by us. In summary, chemical models of T Tauri disks predict the existence of an important reservoir of hot water in the inner regions (formed by warm gas-phase chemistry) and smaller amounts of OH (formed by FUV photodissociation of water), with numbers that are roughly in agreement with those derived from IR observations.

Fig. 5.

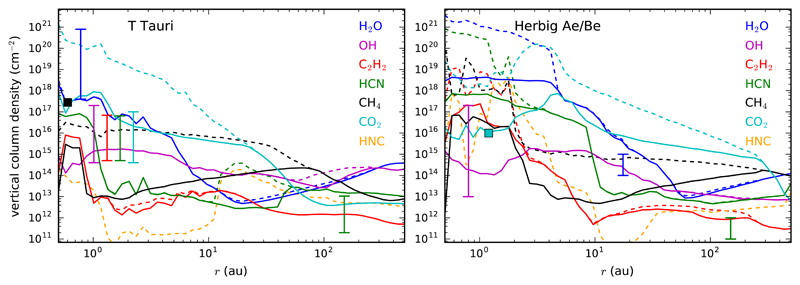

Calculated vertical column densities down to the AV=10 surface (solid lines) and down to the midplane (dashed lines) of H2O, OH, and simple organics as a function of radius r for the T Tauri (left panel) and Herbig Ae/Be (right panel) disks. For HNC, only the total column density down to the midplane is shown. Column densities derived from observations are indicated by vertical lines (when there are ranges of values) or by squares (when only one value is available), with their radial locations corresponding to the approximate region probed by observations (see Table 3).

In disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars, OH has been detected in about a dozen of objects with a broad range of column densities (see Table 3). In our Herbig Ae/Be disk model, the calculated vertical column density of OH is ~1015 cm−2 across the first 10 au, decreasing down to ~1013 cm−2 in the outer disk, in the low range of values derived from observations (see right panel in Fig. 5). Walsh et al. (2015) calculate somewhat higher values for the inner 10 au, 1016-1017 cm−2, more in line with the high range of observed values. Water has been convincingly detected at IR wavelengths only around one Herbig star, HD 163296 (Meeus et al. 2012; Fedele et al. 2012). The H2O and OH column densities derived in this disk are similar, in the range 1014-1015 cm−2, and the emitting region for both species is constrained to be 15-20 au from the star. In our Herbig Ae/Be disk model, the column density of water is very large in the inner disk (out to ~4 au), where it is very abundant in the midplane (see right panels in Figs. 4 and 5), and experiences a sharp abundance decline with increasing radius. At 15-20 au from the star, where water is no longer present in the midplane but in upper disk layers, the model yields N(H2O) = 1015-1016 cm−2 and N(OH) = 1014-1015 cm−2, with a OH/H2O ratio of ~0.1, values which are not far from those derived in the HD 163296 disk. In the Herbig Ae disk model of Walsh et al. (2015), at 10 au (the farthest radius studied by these authors) the column densities of H2O and OH are in the range 1016-1017, with the OH/H2O ratio approaching unity. The model of Walsh et al. (2015) and ours do a reasonable job at explaining the order of magnitude of the water and OH observations of HD 163296. It however remains puzzling to explain the extremely low detection rate of water in Herbig Ae/Be disks, as compared with T Tauri disks, taking into account that chemical models (Walsh et al. 2015 and this work) predict that in disks around Herbig stars, water should be even more abundant than in T Tauri disks. Several explanations have been proposed (see Antonellini et al. 2016 and references therein), most of which are related to observational aspects (e.g., the higher level of infrared continuum in Herbig Ae/Be disks and the lower sensitivity reached for detection of emission lines above the continuum) than with substantive differences in the chemistry between disks around low- and intermediate-mass pre-main sequence stars.

Our model predicts that the reservoir of hot water present in the inner regions of disks around T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be stars vanishes typically beyond 10 au from the star, owing to thermal deactivation of the water-forming reaction OH + H2 and to freeze-out onto dust grains. This drastic decline of various orders of magnitude in the abundance and column density of water (see Figs. 4 and 5) has been observationally probed by mid- to far-IR observations in a few protoplanetary disks (Blevins et al. 2016). The model however predicts that there exists an additional reservoir of cold water in the outer parts of T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks, typically beyond 100 au and at intermediate heights (see Fig. 4). Water in these regions arises from the FUV photodesorption of water ice and reaches peak fractional abundances of ~10−7, with typical vertical column densities of the order of 1013-1014 cm−2 (see Fig. 5). This outer reservoir of water is also predicted by previous chemical models of T Tauri disks which include photodesorption (e.g., Willacy & Langer 2000; Woitke et al. 2009; Semenov et al. 2011; Walsh et al. 2012) and has been detected with Herschel/HIFI in the T Tauri disks TW Hya and DG Tau (Hogerheijde et al. 2011; Podio et al. 2013) and in the Herbig Be disk HD 100546 (van Dishoeck et al. 2014; Du et al. 2017), although it remains elusive to detection in many other protoplanetary disks (Bergin et al. 2010; Du et al. 2017). It is remarkable that the detection rate of water at sub-mm wavelengths is not so different between T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disks as it is at IR wavelengths (see Table 3), which suggests that the low detection rate of H2O IR emission in Herbig objects may not be due to an intrinsic deficit of water with respect to T Tauri systems.

3.2. Simple organics: C2H2, HCN, CH4, and CO2

It is known that there exists an important reservoir of simple organic molecules in protoplanetary disks. Thanks to observations at near- and mid-IR wavelengths, lines of molecules such as acetylene, hydrogen cyanide, methane, and carbon dioxide have been detected in absorption (Lahuis et al. 2006; Gibb et al. 2007; Gibb & Horne 2013; Bast et al. 2013) and in emission (Carr & Najita 2008, 2011; Salyk et al. 2011; Kruger et al. 2011; Mandell et al. 2012; Najita et al. 2013; Pascucci et al. 2013). These observations probe hot gas located in the inner (a few au) disk, where these molecules are found with large abundances. It is noteworthy that the vast majority of infrared detections of simple organics correspond to disks around T Tauri stars rather than to disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars, where neither C2H2, HCN, nor CH4 are detected, and only CO2 has been detected in one disk, HD 101412 (Salyk et al. 2011). It is therefore tempting to think that Herbig Ae/Be disks are less rich in simple organics than disks around T Tauri stars. However, similarly to the case of H2O, we do not find such a trend in our models.

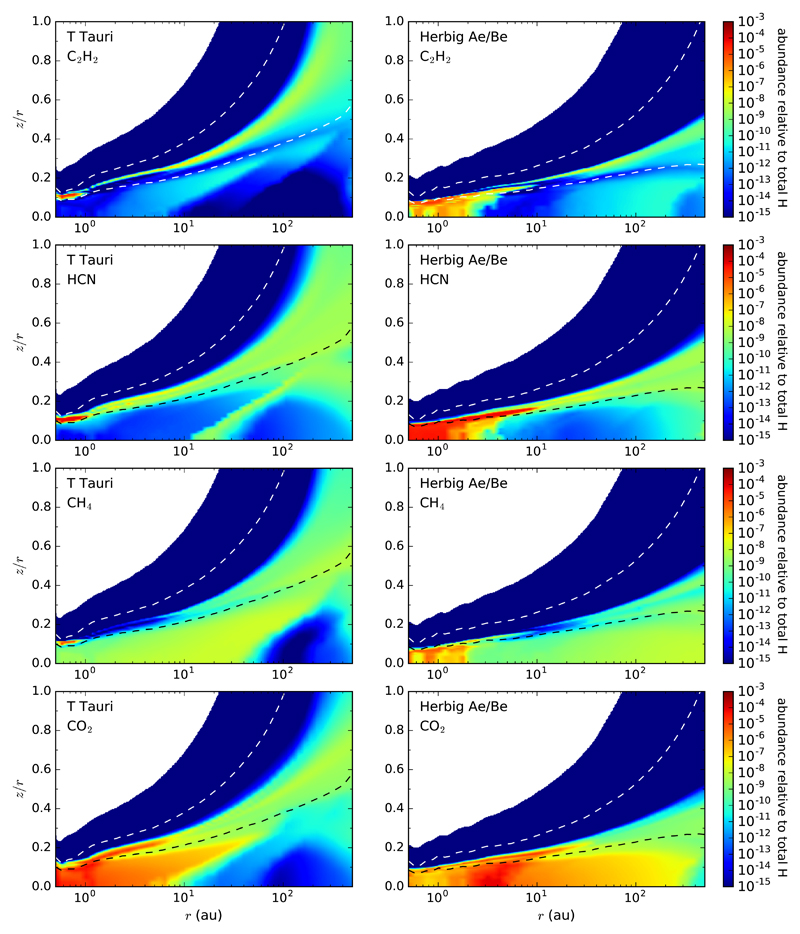

In our T Tauri disk model, C2H2, HCN, and CH4 are formed with high fractional abundances (a few × 10−5) in the atmosphere (AV~1) of the inner (within a few au) regions of the disk (see Fig. 6). Their synthesis is driven by FUV photochemistry in a warm gas (see Agúndez et al. 2008; Bast et al. 2013; Walsh et al. 2015). In the Herbig Ae/Be disk model, the region over which these molecules have large fractional abundances extends to larger radii compared to the T Tauri disk, as a consequence of the higher temperatures. Moreover, in the Herbig Ae/Be disk, C2H2, HCN, and CH4 are formed abundantly in the inner midplane, where the synthesis is not related to photochemistry but to the fact that the chemical composition tends toward thermochemical equilibrium in these hot, dense, and FUV-shielded regions. Both the T Tauri and Herbig Ae/Be disk models show a progressive disappearance of simple organics as one moves radially from the star, in this order: CH4, C2H2, and HCN. This behavior, already predicted by Agúndez et al. (2008), is a consequence of the requirements of temperature that each molecule has to activate its corresponding formation routes, with CH4 being the most demanding. Such a trend is also found in the disk models of Walsh et al. (2015) for C2H2 and HCN. Note that CH4, unlike C2H2 and HCN, is also predicted to be moderately abundant in cool midplane regions, where the synthesis is driven by ion-molecule routes. In these regions however the calculated abundance of CH4 could be especially uncertain if grain-surface chemistry (not included in our models) plays an important role.

Fig. 6.

Same as Fig. 4 but for C2H2, HCN, CH4, and CO2.

The calculated vertical column densities of C2H2 and HCN in the IR-observable atmosphere of the inner T Tauri disk (within 1 au from the star) are large, with maxima in the range 1015-1017 cm−2, in good agreement with observed values (see left panel in Fig. 5). Observations of T Tauri disks indicate that C2H2 and HCN have similar abundances, although there is a significant dispersion, and that they are somewhat less abundant than water vapor (C2H2/HCN = 0.04-20; HCN/H2O = 10−3-10−1;Lahuis et al. 2006; Gibb et al. 2007; Carr & Najita 2011; Salyk et al. 2011; Mandell et al. 2012; Bast et al. 2013). These observed ratios are in line with the values found in the T Tauri disk model. Methane has only been detected in one T Tauri disk, GV Tau, in absorption (Gibb & Horne 2013). These authors derive a column density of 2.8 × 1017 cm−2 and a rotational temperature of 750 K, which implies that the detected CH4 is distributed in the inner disk. In GV Tau, CH4 is somewhat more abundant than C2H2 and HCN. Note however that in DR Tau, the non detection of CH4 in emission implies that it has an abundance similar to or smaller than C2H2 and HCN (Mandell et al. 2012). In our T Tauri disk model, CH4 reaches a column density of the order of those of C2H2 and HCN in the IR-observable atmosphere of the inner disk (see left panel in Fig. 5). Neither C2H2, HCN, or CH4 have been observed in Herbig Ae/Be disks, although our model predicts that they should be even more abundant than in T Tauri disks (see Figs. 5 and 6). Similar conclusions are found in the models by Walsh et al. (2015). The lack of simple organics in the spectra of Herbig Ae/Be disks has not been investigated to the extent of the lack of water, but it is likely that observational rather than chemical effects are at the origin of it.

Carbon dioxide has been extensively observed in T Tauri disks but only in one Herbig Ae/Be disk, where the derived column density is within the range of values found in T Tauri disks. In our models, CO2 is formed abundantly, mostly in the inner disk (< 10 au in the T Tauri disk and < 100 au in the Herbig disk) and over most of the vertical structure (see Fig. 6). The formation of CO2 occurs in the gas-phase, mainly through the reaction OH + CO, and is less demanding in terms of temperature than the formation of C2H2, HCN, and CH4. Therefore, CO2 extends over larger radii than the other simple organics. The calculated column density of CO2 in the IR-observable atmosphere of the inner (< 10 au) T Tauri disk is in the range 1016-1018 cm−2 (see left panel in Fig. 5), in the high range of observed values. As with the other simple organics, according to the model there is no apparent chemical reason for a lower amount of CO2 in disks around Herbig Ae/Be stars than in T Tauri disks.

The simple organic molecules discussed here experience a drastic decline in their column densities with increasing radius, especially for C2H2 and HCN (see Fig. 5). This extended and cooler reservoir of simple organics can be probed at mm wavelengths in the case of polar molecules like HCN. In fact, HCN has been extensively characterized this way in protoplanetary disks (Dutrey et al. 1997; Thi et al. 2004; Fuente et al. 2010, 2012; Öberg et al. 2010, 2011; Chapillon et al. 2012a; Kastner et al. 2014; Guilloteau et al. 2016). Although the statistics of Herbig Ae disks is low, these studies suggest that T Tauri disks can retain in their outer parts somewhat larger HCN abundances than Herbig Ae disks (see Table 3). The column densities calculated for HCN beyond 100 au are ~1013 cm−2 in both the T Tauri and the Herbig Ae/Be disks, in the high range of observed values (see Fig. 5). The model predicts a slightly higher amount of HCN in the outer regions of the T Tauri disk compared to the Herbig disk. It is interesting to note that the contrary is found in the inner regions. The reason is that the chemical synthesis of HCN is different in nature in the hot inner disk than in the cool outer regions. In the outer disk (>100 au), HCN is mainly present at intermediate heights with fractional abundances of ~10−8 relative to H2 (see Fig. 6). In these regions, HCN is formed by the same gas-phase chemical routes that operate in cold interstellar clouds, i.e., through ion-molecule reactions that lead to the precursor ion HCNH+, which by dissociative recombination yields HCN as well as its isomer HNC. Thus, both observations and our model suggest that HCN is somewhat more abundant in the outer regions of T Tauri disks compared to Herbig Ae/Be disks. We however caution that on the observational side, the statistics of Herbig Ae disks is low, and on the theoretical one, the difference is small and could result from the particular set of parameters adopted in the models.

Hydrogen isocyanide, closely related to HCN from a chemical point of view, has been only detected around the T Tauri stars DM Tau and TW Hya and the Herbig Ae star HD 163296 (Dutrey et al. 1997; Graninger et al. 2015). The lower detection rate of HNC in disks compared to its most stable isomer HCN suggests that HNC is less abundant than HCN, although there is also a selection effect as lines of HNC have not been targeted as often as those of HCN (e.g., Öberg et al. 2011; Guilloteau et al. 2016). Observations indicate that HNC is indeed somewhat less abundant than HCN, with HNC/HCN ratios in the range 0.1-0.4 (see Table 3). These values may need to be revised down due to differences in the collisional excitation rate coefficients of HCN and HNC (Sarrasin et al. 2010). The calculated distribution of HNC approximately follows that of HCN, but at a lower level of abundance (see Fig. 5). The model shows that there is a gap in the column density of HNC which occurs at 1-10 au in the T Tauri disk (shifted to larger radii in the Herbig Ae/Be disk). There is observational evidence of such a gap in the distribution of HNC from SMA interferometric observations of TW Hya (Graninger et al. 2015). While the presence of HNC in the hot inner disk is related to the existence of large amounts of HCN, a fraction of which isomerizes to HNC in the hot gas phase, in the cool outer disk, HNC has an abundance of the order of that of HCN because the two isomers share the same chemical formation routes, with the molecular ion HCNH+ as main precursor. The calculated HNC/HCN ratio in the outer disk (>100 au) is 0.3-0.4 in both the T Tauri and the Herbig Ae/Be disks, in line with the values derived from observations. Interferometric observations indicate that HNC does not extend out to radii as large as HCN in TW Hya (Graninger et al. 2015), a feature that is not predicted by our T Tauri disk model. A possible explanation could be related to an enhanced photodissociation cross section of HNC compared to that of HCN, something that is suggested by theoretical calculations (Chenel et al. 2016; Aguado et al. 2017).

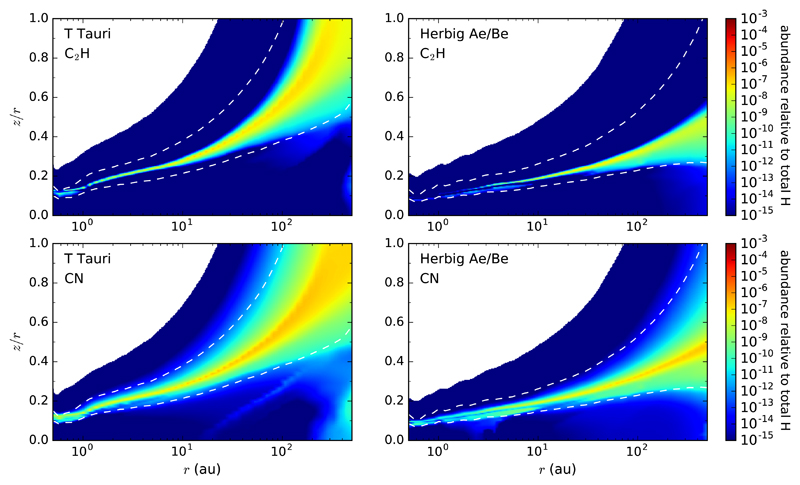

3.3. Radicals C2H and CN