Abstract

Introduction

Preclinical and clinical evidence suggest that the neuropeptide oxytocin may be of value in treating alcohol use disorder, either by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol or reducing negative affect induced by alcohol withdrawal. However, the effect of a single dose of oxytocin on subjective and psychomotor responses to alcohol in social drinkers is not known.

Methods

The present study examined the effect of intranasal oxytocin on subjective, behavioral, and physiological responses to a moderate dose of alcohol (0.8 g/kg) in young adult social drinkers. Participants (N=35) completed two study sessions at which they consumed beverages containing alcohol (ALC; N=20) or placebo (NoALC; N=15) in combination with intranasal oxytocin (40 IU with a 20 IU booster) or placebo. They received oxytocin at one session and placebo at the other session (order counterbalanced) 20 min before consuming beverages. Subjective mood and drug effects ratings, heart rate and blood pressure, and four behavioral tasks (flanker task, digit span, go/no-go, and pursuit rotor) were the primary outcome measures.

Results

ALC produced its expected subjective and behavioral effects; including feeling intoxicated and impaired performance on the digit span and go/no-go tasks. Oxytocin alone had no significant subjective or physiological effects, and it did not affect responses to alcohol on any measure.

Conclusion

We can conclude that, under these conditions, a single dose of intranasal oxytocin does not alter the effects of acute alcohol in healthy young adult social drinkers. Further research is needed to determine whether oxytocin alters responses to alcohol under different conditions, and to determine its potential as an aid in treatment for substance use disorders.

Keywords: oxytocin, alcohol, human subjects, psychomotor

Introduction

Despite advances in treatments for alcohol-use disorders (AUD), there remains an urgent need for novel approaches to reduce problematic drinking. One promising new candidate as a medication for AUD and other substance use disorders is the neuropeptide oxytocin. Preclinical studies suggest that oxytocin may reduce both the reinforcing properties and other behavioral effects of alcohol (Bahi, 2015; Bowen et al., 2015; Peters, Bowen, Bohrer, McGregor, & Neumann, 2017). In humans, there is early evidence that oxytocin dampens desire for marijuana, nicotine, and for alcohol in current and detoxified alcoholics (McRae-Clark, Baker, Maria, & Brady, 2013; Miller, Bershad, King, Lee, & de Wit, 2016; Pedersen, 2017; Sherman, Baker, & McRae-Clark, 2017). Yet, no studies have examined effects of oxytocin on responses to acute alcohol administration in non-dependent, social drinkers. Therefore, the current pilot study sought to assess the effects of intranasal oxytocin on subjective, behavioral, and physiological responses to a moderate dose of alcohol in healthy social drinkers.

Oxytocin is an endogenous peptide hormone that is synthesized in the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei of the hypothalamus (Lee, Rohn, Tanda, & Leggio, 2016; Viero et al., 2010). It is released centrally via dendritic and terminal mechanisms, and peripherally via the posterior pituitary (Lee & Weerts, 2016). G-protein coupled oxytocin receptors are widely distributed throughout the central nervous system, including in regions implicated in reinforcement and reward processing (Viero et al., 2010). In addition to its well-known role in sexual and maternal behaviors, oxytocin appears to facilitate pro-social behaviors, including increased empathy, trust, and the tendency to favor members of an in-group (Bethlehem, van Honk, Auyeung, & Baron-Cohen, 2013; Mitchell, Gillespie, & Abu-Akel, 2015; Viero et al., 2010). There is also both preclinical and clinical evidence that oxytocin attenuates anxiety and responses to stress (Bethlehem et al., 2013; Heinrichs, Baumgartner, Kirschbaum, & Ehlert, 2003; Lee & Weerts, 2016; Mitchell et al., 2015; Viero et al., 2010), effects that may indirectly reduce alcohol craving and consumption in problem users (Fox, Bergquist, Hong, & Sinha, 2007; Magrys & Olmstead, 2015). Evidence also suggests that oxytocin has an inhibitory effect on learning and memory (de Wied, Diamant, & Fodor, 1993; Sarnyai & Kovács, 2014), and this may hold relevance for substance use disorders, in which maladaptive learning and memory processes are a central feature.

Oxytocin also interacts with the mesolimbic dopamine system, which may influence subjective responses to alcohol. For example, in rats, oxytocin injected into the ventral tegmental area increases extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, and this effect is blocked by oxytocin receptor antagonists (Melis et al., 2007). Activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system contributes to alcohol’s reinforcing effects, and may have a role in alcohol’s subjective effects in humans (Aalto et al., 2015; Boileau et al., 2003; Hendler, Ramchandani, Gilman, & Hommer, 2011; Samson, Tolliver, Haraguchi, & Hodge, 1992; Urban et al., 2010; Yoder et al., 2005). Possibly via its interactions with dopaminergic systems, exogenous oxytocin administration appears to reduce the reinforcing effects of alcohol in rodent models (Burkett & Young, 2012; Bahi, 2015; Kenna et al., 2016; King et al., 2017; MacFadyen et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Stevenson et al., 2017). Because reinforcing effects are closely linked with positive subjective effects in humans, it is reasonable to speculate that oxytocin may also reduce subjective alcohol responses in humans.

Interestingly, oxytocin may also decrease the sedative and motor-impairing effects of moderate doses of alcohol, but whether these effects translate to humans is unclear. In a recent study with rats, a 1.5 g/kg dose of ethanol produced significant motor impairments on wire-hanging and righting reflex tests, as well as reduced locomotor activity in an open-field test (Bowen et al, 2015). Rats pretreated with oxytocin showed an attenuation of ethanol-induced impairment at 5 and 35 minutes post alcohol administration. Oxytocin, however, did not reduce the motor impairing effects of a 3 g/kg dose of alcohol. To date, no clinical studies have assessed oxytocin’s effects on alcohol-induced impairments in psychomotor performance.

There are few reports of interactions between oxytocin and alcohol in humans. One small pilot study examined effects of oxytocin (24 IU twice a day for 3 days) in 7 alcohol dependent patients undergoing acute inpatient withdrawal. Relative to placebo (n=4), oxytocin decreased the amount of lorazepam needed to treat withdrawal symptoms during acute detoxification (Petersen et al, 2017; Pedersen et al., 2013). In a randomized clinical trial, 22 heavy drinkers self-administered daily doses of oxytocin (40 IU, 2–3 times daily) or placebo for twelve weeks. Compared to placebo, oxytocin significantly reduced the number of drinks per drinking day, and marginally reduced the number of heavy drinking days, but had no effect on craving or anxiety scores (Pedersen et al, 2017). The authors suggest that these findings indicate a reversal of alcohol tolerance. These two reports suggest that oxytocin reduces both withdrawal symptoms and alcohol consumption.

The present study was designed to determine whether intranasal oxytocin reduces responses to a single, moderate dose of alcohol in healthy volunteers. Based on the evidence described above, we hypothesized that oxytocin would reduce the positive subjective responses to alcohol. Furthermore, because oxytocin reduced ethanol-induced sedation and motor impairment in rats (Bowen et al., 2015), we also hypothesized that intranasal oxytocin would dampen alcohol-induced psychomotor and neurocognitive impairment, relative to placebo. We assessed the effects of oxytocin during both the ascending and descending limbs of the blood alcohol curve to monitor its time course of effect and determine its effects over a range of blood alcohol concentrations (Fillmore, Marczinski, & Bowman, 2005; Fillmore & Weafer, 2012; Schweizer & Vogel-Sprott, 2008).

Methods

Overall design

The study used a mixed within and between subject design to examine the effect of oxytocin vs. placebo on subjective and behavioral responses to an alcohol or placebo challenge. During two study sessions, healthy social drinkers received nasal sprays containing placebo on one session and oxytocin (40 IU) on the other session, in random order. Sprays were administered both shortly before consuming a beverage and again after the beverage. Half of the participants received alcohol in the beverages at both sessions (ALC), and half received placebo beverage at both sessions (NoALC; between-subjects). Dependent measures included self-report ratings of subjective effects of both the nasal sprays and the beverages, as well as computer-based cognitive and psychomotor behavioral tasks, blood pressure and heart rate. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago approved the study, and it was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Thirty-five healthy social drinkers (19 male, 16 female) with were recruited via community flyers and online advertisements. Screening included a psychiatric evaluation and physical examination. Inclusion criteria were age 21–35 years, at least a high school education, BMI between 19 and 26, and English fluency. Further, only candidates consuming at least 6 drinks per week with at least one binge episode (per the NIAAA guidelines of 4 drinks for women and 5 drinks for men) in the past 30 days were included, based on a retrospective Timeline Follow Back (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1992) calendar. Candidates were excluded if they had a current DSM-5 major psychiatric disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), history of alcohol or other substance dependence (except nicotine), performed night shift work, were taking regular medications (except birth control), or had a history of nasal surgery, hyponatremia, diabetes insipidus, or syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone. Women who were pregnant, nursing, or planning to become pregnant were excluded from participation.

Participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment into the study. They were told that they would receive nasal sprays containing either a hormone, such as vasopressin or oxytocin, or placebo, and beverages containing alcohol or placebo at each session. Participants were instructed to consume their normal amounts of caffeine and nicotine before the sessions, but to abstain from food, nicotine, and caffeine for 2 hours prior to each session. They were also instructed to refrain from alcohol and other recreational drugs for at least 24 hours prior to each study session. Women using hormonal contraceptives were tested at any time in their menstrual cycle, but those not using contraceptives (n=3) were tested only in the follicular phase to control for fluctuations in endogenous hormone levels (Miller et al., 2016; Weafer, Gallo, & de Wit, 2016).

Procedures

Sessions took place at the Human Behavioral Pharmacology Laboratory at the University of Chicago. Participants first completed an orientation session, during which they practiced the cognitive and psychomotor behavioral tasks and were familiarized with the study protocol and questionnaires. The sessions were conducted with participants individually in a comfortable living-room-like space with couches, a computer (for data collection and task administration only), and a selection of magazines, as well as movies available to participants when measures were not being obtained.

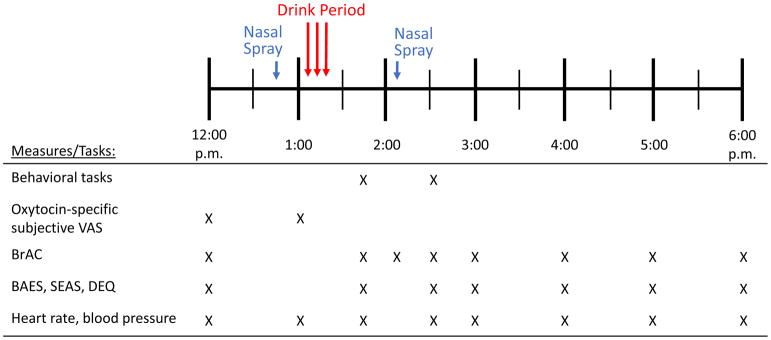

The two study sessions took place from 12 to 6 p.m., Monday through Saturday, and were separated by at least 7 days. The session timeline is summarized in Figure 1. Upon arrival, participants provided breath (measured via AlcoSensor IV Breathalyzer, Intoximeters, Inc., St. Louis, MO) and urine (measured via Rapid Drug Test, CLIAwaived Inc, San Diego, CA) samples to detect recent alcohol and drug use, and pregnancy in women (measured via CLIAwaived Inc, San Diego, CA). Sessions were rescheduled if participants tested positive for alcohol or drugs (except THC; 3 participants in ALC and 5 in NOALC tested positive for THC prior to both sessions). After breath and urine tests, participants completed baseline subjective questionnaires (pre-beverage Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES), Drug Effects Questionnaire (DEQ) and Subjective Effects of Alcohol Scales (SEAS)) and underwent heart rate and blood pressure readings (measured via Omron Blood Pressure Monitor, Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, IL) followed by a light snack (Nature Valley Crunchy Granola Bars, General Mills, Minneapolis, MN). Then, they received two nasal sprays containing either oxytocin (40 IU) or placebo (see Drugs below). Fifteen minutes after the sprays, they completed visual analog questionnaires assessing response to oxytocin. Then they consumed a beverage in three small portions (ALC (0.8 g/kg for males, 0.68 g/kg for females) or NoALC; see Drugs below). A research assistant was present and conversed with the participants during beverage consumption. Twenty minutes after finishing the beverage, participants completed the first round of cognitive and psychomotor behavioral tasks (see below), corresponding with the ascending limb of the blood alcohol curve. Then they received a second nasal spray with the same contents as the first (the oxytocin dose for the second, booster spray was 20 IU), and repeated the cognitive and psychomotor tasks, corresponding with the descending limb of the blood alcohol curve. Other dependent measures included breath alcohol (BrAC) and vital sign measurements, mood, and subjective drug effects questionnaires every 15–60 min throughout the session until 6 p.m. When BrAC was below 0.04% (usually by 6 pm), the experimental session ended.

Figure 1.

Timeline of experimental sessions

To assess the blind, each study session ended with a survey asking the participants which drug (oxytocin, vasopressin, or placebo) they believed that they received in the nasal sprays and beverages (alcohol or placebo), as well as to rate whether they felt any effects of the spray and beverages (“I felt no effect,” “I think I felt a mild effect, but am not sure,” “I definitely felt an effect, but it was not strong,” “I felt a strong effect,” “I felt a very strong effect”). Following oxytocin sessions, while 57% of participants reported feeling a mild effect of the sprays, only 26% of participants indicated that they believed that they had receive oxytocin. Following the placebo session, 51% of participants reported feeling a mild effect of the sprays and 34% of participants correctly labeled the placebo. All participants who received alcohol correctly indicated that the beverages contained alcohol, while those who received placebo correctly indicated that the beverages did not contain alcohol 70% of the time.

Behavioral tasks

The four neurocognitive and psychomotor tasks were used to assess specific cognitive processes that are impaired by acute alcohol: digit span, flanker task, go/no-go task, and pursuit rotor (Fillmore, 2003; Fillmore et al., 2005; Grattan-Miscio & Vogel-Sprott, 2005; Mann & Vogel-Sprott, 1981; Maylor & Rabbitt, 1993; Schweizer et al., 2006). The tasks were obtained from the Psychology Experiment Building Language (PEBL; Mueller & Piper, 2014), and subjects completed the tasks in random order, 20 and 70 minute after consuming their beverages. The tasks took 20 minutes to complete. Due to technical errors, 3 participants’ data from the NoALC group were lost or incomplete.

Digit Span

The digit span task is a working memory task that consists of visual presentation of a series of numbers, one at a time. After the series of numbers is displayed, the participant must respond by typing the numbers in the same in order in which they appeared. The number of digits displayed is increased by one digit every two trials, up to a maximum of 10. The task ends when the participant incorrectly responds on 2 consecutive trials or after 10 digits. The primary outcome measures are memory span (the maximum number of digits correctly recalled) and the number of total correct trials.

Flanker Task

The flanker task in PEBL is a modified version of the Eriksen flanker task (Eriksen & Schultz, 1979), which assesses conditional accuracy and reaction time with distractors. Participants respond by indicating the direction towards which a central arrow is pointing. On some trials the central arrow is flanked by congruent arrows (pointing in the same direction), on other trials by incongruent arrows (pointing in the opposite direction), dashes, or nothing. The primary outcome measures are accuracy, mean response time, and number of errors.

Go/No-Go Task

The go/no-go task in PEBL assesses response inhibition and reaction time (Bezdjian, Baker, Lozano, & Raine, 2009). The task requires participants to attend to the presentation of letters and respond to the target letter (go signal), while suppressing responses to the distractor letter (no-go signal). The screen shows a 2 × 2 array, with each quadrant containing a star. On each trial, one of the stars is randomly replaced with a letter P or R, with P’s appearing in greater frequency. In the first condition, participants are instructed to respond to the presentation of the letter P in any of the 4 quadrants and suppress responses to the letter R. In the reversal condition, participants are instructed to respond to the presentation of the letter R and suppress responses to the letter P. The primary outcome measures are the total number of errors (commission and omission) and the mean response time under each condition.

Pursuit Rotor

The pursuit rotor task assesses motor dexterity by requiring the participant to use a computer mouse to follow a target moving at a fixed rate along a circular track (Piper et al., 2015). The target moves at a fixed rate, and participants perform four 15-second trials. The total time on the target is the primary outcome measurement.

Subjective effects

Subjective effects of oxytocin were assessed with visual analog scales on which subjects rated themselves on the following items: tense, dreamy, focused, excited, dizzy, anxious, relaxed, alert, calm, friendly, withdrawn, social, content, drowsy, stimulated, and tired on a scale of 0–100. Subjective effects of alcohol (or placebo beverage) were assessed via the drug effects questionnaire (DEQ; (Fischman & Foltin, 1991; Morean et al., 2013) assessing overall magnitude of drug effect, drug liking and disliking, and wanting, as well as the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale (BAES; Martin, Earleywine, Musty, Perrine, & Swift, 1993) and the Subjective Effects of Alcohol Scale (SEAS; Morean, Corbin, & Treat, 2013).

Drugs

Alcohol and oxytocin were administered under double blind conditions. Alcohol beverages (ALC) were prepared with 95% alcohol (Everclear, Luxco Inc., St. Louis, MO) and orange juice. The volume of 500–900 mLs (depending on the participant’s body weight) was evenly distributed into 3 plastic cups administered at 5 min intervals. The dose was chosen to produce peak blood alcohol concentrations of 0.08 mg% (0.80 g/kg for males, 0.68 g/kg for females; based on body weight). In the placebo beverage condition (NoALC), subjects received an equivalent volume of orange juice distributed evenly among three cups, each with a 1mL “floater” of 95% alcohol.

Intranasal oxytocin (OT) doses were prepared within 24 hours of administration by the University of Chicago Hospital investigational pharmacy. A single dose of Pitocin (OT Injection USB; Monarch Pharmaceuticals; concentration: 10 IU Pitocin/1 ml) was distributed into syringes (1 mL/syringe). Placebo nasal sprays consisted of Ocean Spray Nasal Solution (Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Bridgewater, NJ), placed in 1 mL syringes. Atomizers (MAD300 by LMA Inc., San Diego, CA) were affixed to the syringes to facilitate administration. The nasal sprays were administered over a 5 minute period by trained personnel. The nasal sprays contained 0.5 mL per inhalation. During the first administration before the beverage they received 8 inhalations (40 IU total; 2 mL/nostril) and then at the booster dose after the beverage they received a further 4 inhalations (20 IU; 1 mL/nostril)

Data Analysis

Breath alcohol concentrations were analyzed using repeated measures ANOVA with the within-subjects factors of time and spray (OT vs PL).

Subjective responses to the first dose of oxytocin were analyzed via a two-way ANOVA with time (pre- and post-nasal sprays) and spray (placebo and oxytocin) as the within-subject factors, collapsed across ALC and NoALC. Post hoc t-tests were used to follow-up on any significant interactions. Because subjective responses to oxytocin may be modulated by gender (Olff et al., 2013), secondary ANOVAs included gender as a covariate.

Subjective, behavioral, and physiological responses were separately analyzed via 3-way repeated measures ANOVAs, each with the within-subjects factors of time and spray (OT vs PL), and between-subjects factor of beverage (ALC vs NoALC). Simple effects post hoc tests were conducted on any interactions that were statistically significant (p<0.05) to identify alcohol or OT effects. In separate repeated measures ANOVAs conducted only on the data from the ALC group, average number of drinks per week, as determined from TLFB, was included as a covariate to determine if, the effects of oxytocin on alcohol response was related to recent drinking history (King, de Wit, McNamara, & Cao, 2011).

Results

Demographics

Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics for the alcohol (ALC) and placebo (NoALC) groups. The groups did not differ in age, body mass index (BMI), number of years of education, or current drug and alcohol use. Overall, participants reported consuming about 12 ± 1.1 alcohol drinks per week and 4.2 ± 0.6 binge episodes during the past month.

Table 1.

Participant Demographics

| Alcohol (ALC; n=20) Mean (SD) |

Placebo (NoALC; n=15) Mean (SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (M:F) | 9:11 | 10:5 | 0.20 |

| Age (years) | 26.0 (5.1) | 26.1 (4.5) | 0.97 |

| BMI | 22.1 (1.7) | 23.1 (1.3) | 0.07 |

| Education (years) | 15.6 (1.9) | 15.5 (1.6) | 0.83 |

| Race (%) | 0.15 | ||

| White | 50 | 60 | |

| Black | 10 | 27 | |

| Other/Mixed | 40 | 6.5 | |

| Not provided | 0 | 6.5 | |

| Current drug use (past month)* | |||

| Caffeine (# servings/day) | 1.9 (0.8); n=19 | 2.0 (0.6); n=11 | 0.83 |

| Cigarettes (#/week) | 10.3 (7.6); n=4 | 21.2 (38.1); n=4 | 0.59 |

| Cannabis (# days) | 18.6 (9.0); n=7 | 10.4 (9.2); n=10 | 0.09 |

| Alcohol use (past month) | |||

| # Drinks/week | 11.7 (7.3) | 12.4 (5.7) | 0.77 |

| # Binges/month | 4.1 (3.2) | 4.4 (3.5) | 0.76 |

n= number of participants endorsing past month use; means were calculated using only participants who reported any use

Subjective effects of the initial dose (40 IU) of oxytocin

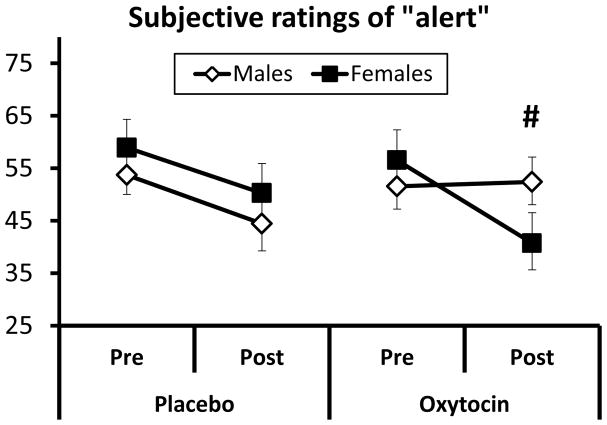

Based on self-report questionnaires completed immediately before and 15 min after the first nasal spray (i.e., before consuming any beverage) oxytocin did not produce any changes in subjective effects relative to placebo. Secondary analyses exploring the role of gender on the subjective effects of intranasal oxytocin indicated that compared to women, men exhibited a marginally significant increase in ratings of “alert” after oxytocin (Figure 2; time x drug x gender repeated measures ANOVA F1,31=3.48, p=0.07). No other sex differences were observed.

Figure 2.

Subjective ratings of “alert” following the first dose (40 IU) of intranasal oxytocin or placebo (drug x time x gender, ANOVA p<0.07). Means ± SEM are shown. # indicates statistical trend.

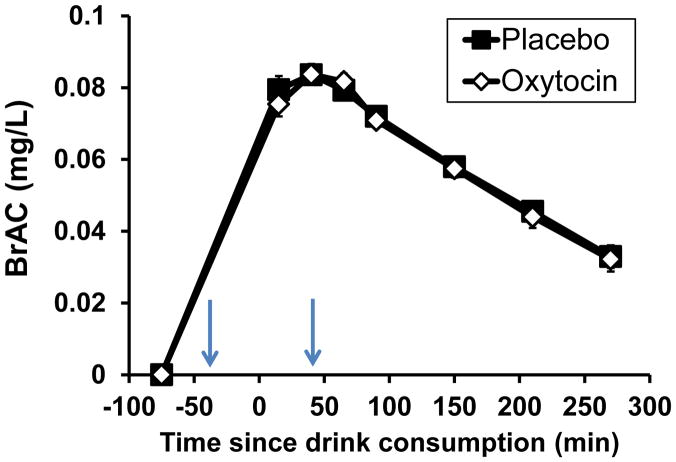

Breath alcohol concentrations

Breath alcohol concentrations (BrAC) are shown in Figure 3. Participants attained a mean peak BrAC of 0.084 ± 0.003 mg/L at approximately 40 minutes following beverage consumption. Men attained a higher peak BrAC than women (peak BrACmales = 0.087 ± 0.005 mg/L, peak BrACfemales = 0.081 ± 0.003 mg/L; time*gender interaction: F7,126=4.33, p<0.001). Oxytocin did not alter BrAC.

Figure 3.

Mean and sem breath alcohol concentrations (mg/L) during the placebo and oxytocin sessions. -75 min represents the pre-beverage value, 0 minutes represents the completion of beverage consumption, and the first time point was obtained 15 minutes after the beverages were consumed. The arrows indicate the times of the nasal sprays.

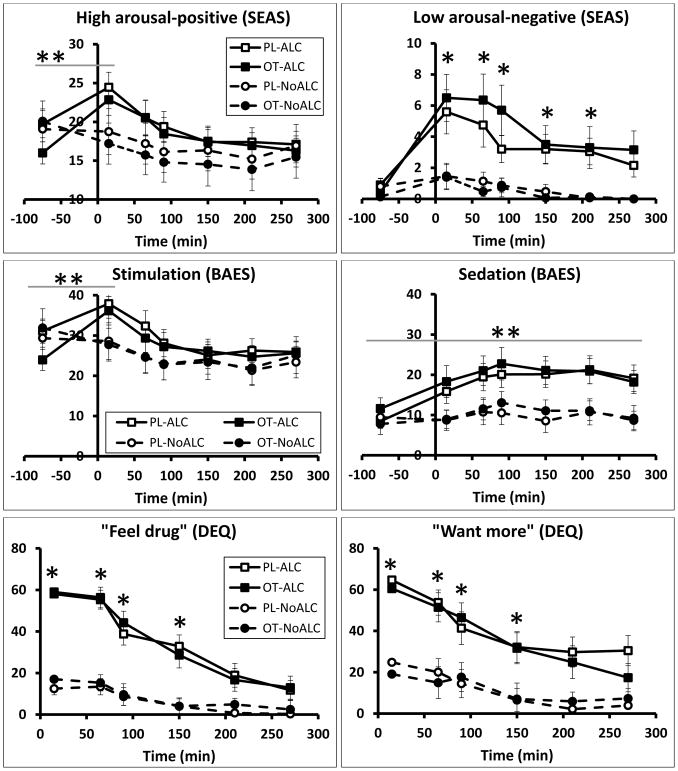

Subjective alcohol responses

Relative to the placebo beverage, alcohol produced its expected subjective effects (Figure 4), but oxytocin did not change these effects. Alcohol significantly increased BAES stimulation scores at 15 minutes following beverage consumption (time*beverage interaction: F6,198=3.59, p=0.002), and increased BAES sedation scores throughout the session (time*beverage interaction: F6,198=2.81, p=0.012). It also increased DEQ ratings on all scales, except “dislike drug” throughout the session (time*beverage interactions: “feel drug,” F6,198=18.46, p<0.001; “want more,” F6,198=6.47, p<0.001; “like drug,” F6,198=9.46, p<0.001; “feel high,” F6,198=17.17, p<0.001; Figure 4). On the SEAS, alcohol increased both high positive arousal (time*beverage interaction: F6,198=4.68, p<0.001; time*spray*beverage interaction: F6,198=2.10, p=0.055; Figure 4) and low negative arousal (F6,198=4.23, p<0.001). Participants in the NoALC condition did not report increases on any of these measures. Subjective responses to alcohol did not differ based on recent drinking history. Oxytocin had no effect on any of the subjective effects.

Figure 4.

Ratings of subjective alcohol effects. The y-axis indicates the mean rating values (± SEM) for each item. Time = 0 min represents the completion of beverage consumption, and nasal sprays occurred at Time=−30 min and 40 min. * indicates statistical significance for ALC vs NoALC (p<0.01); **indicates significant time*beverage interaction (p<0.001)

Behavioral Tasks

Alcohol impaired performance on the digit span and go/no-go tasks, but oxytocin had no effect on these measures. Relative to the NoALC group, subjects in the ALC group remembered fewer digits (mean ± SEM: ALC, 7.4 ± 0.2; NoALC, 8.4 ± 0.2 (F1,29=5.28, p=0.029)) and completed fewer correct trials (mean ± SEM: ALC, 9.8 ± 0.3; NoALC, 11.5 ± 0.4 (F1,29=4.37, p=0.045)). In the go/no-go task, alcohol marginally increased response times during the reversal condition (mean ± SEM: ALC, 546.3 ± 6.8 ms; NoALC, 502.1 ± 9.9 ms (F1,28=3.99, p=0.056). Oxytocin did not affect performance on any task or alter the effects of alcohol on the digit span and go/no-go tasks, and recent drinking history was not related to performance measures.

Physiological effects

Relative to placebo, alcohol produced modest cardiovascular effects but oxytocin did not alter on these responses. Alcohol decreased both systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure (time*drink interaction for: SBP, F7,231= 3.75, p<0.001; DBP, F7,231= 3.72, p<0.001). The effects on SBP occurred at 90 and 270 minutes post beverage consumption. While there were no significant differences in DBP between ALC and NoALC at specific time points, alcohol significantly decreased DBP relative to baseline (F1,33= 14.84, p<0.001) at 65–270 minutes post beverage consumption (p<0.05). Alcohol increased heart rate (time*drink interaction: F7,231=3.93, p<0.001) 15 minutes and 150–270 minutes following beverage consumption. Oxytocin did not alter the physiological effects of alcohol.

Discussion

This study examined the effects of intranasal oxytocin on behavioral, subjective, and physiological responses to alcohol in social drinkers. Alcohol (0.8 g/kg for males, 0.68 g/kg for females) produced its expected subjective effects, impaired performance on psychomotor tasks and produced expected cardiovascular effects. However, oxytocin did not modulate any of these effects. Therefore, the results do not support the hypothesis that oxytocin attenuates responses to alcohol in this population of neurotypical, young adult, social drinkers.

Our findings do not fit simply with evidence from rodents suggesting that oxytocin reduced the reinforcing or the motor-impairing effects of alcohol (Bahi, 2015; King et al., 2017; MacFadyen et al., 2016; Peters et al., 2017; Stevenson et al., 2017; Bowen et al., 2015). Reinforcing effects in rodents are often linked to positive subjective responses in humans. In rats, oxytocin also reduces the sedation and motor impairment induced by alcohol in a wire-hanging test and loss of righting-reflex test (Bowen et al, 2015). In the present study, oxytocin did not reduce subjective ratings of ‘liking’ alcohol, the positive, stimulating effects of alcohol, or alcohol-induced sedation and impairments on either a go/no go task or digit span task. There are many possible reasons why our findings in humans do not correspond with the rodent studies. First, the doses and routes of administration of alcohol and oxytocin used in the rodent vs human studies may not be comparable, and the pharmacokinetics of the drugs may differ. For example, in the Bowen et al study, oxytocin was administered directly into the CNS via the cerebral ventricles, whereas in the present study, oxytocin was administered intranasally. Therefore, we are unable to make comparisons regarding the dose of peptide reaching targets in the brain. Second, there may be cross-species differences in how oxytocin affects behavior and there are clear differences in the measures used to assess alcohol ‘reward’ in rodents vs humans, or motor impairment (e.g., wire-hanging vs reaction time). The difficulty in designing truly translational studies in human and nonhuman species remains a significant challenge to the field (Stephens, Crombag, & Duka, 2011).

Several previous studies in alcohol dependent individuals suggested that oxytocin might have therapeutic potential for alcohol use (Mitchell, Arcuni, Weinstein, & Woolley, 2016; Pedersen, 2017; Pedersen et al., 2013). Pederson et al (2013, 2017) reported that oxytocin reduced both alcohol withdrawal severity and anxiety in detoxifying AUD patients, and reduced the number of drinks per drinking day among heavy drinkers meeting DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence. Mitchell et al (2016) reported that oxytocin reduced cue-induced craving for alcohol in AUD patients with high scores on relationship anxiety. These previous clinical findings are consistent with the idea that oxytocin has anxiolytic effects, which might be most apparent during withdrawal or in anxious individuals. It has also been proposed that oxytocin may reduce or inhibit tolerance induced by chronic, long-term alcohol use (Lee et al., 2016; Pedersen, 2017; Szabó, Kovács, Székeli, & Telegdy, 1985; Szabó, Kovács, & Telegdy, 1989; Tirelli, Jodogne, & Legros, 1992). It was difficult to address these ideas in this study, in which the participants were young adult social drinkers without significant anxiety, and without and without evidence of either acute or chronic tolerance (Brumback, Cao, & King, 2007; Fillmore & Weafer, 2012) on psychomotor performance. The design of this study did not allow us to evaluate oxytocin’s effects on acute or chronic tolerance to alcohol. It is possible that the effects of oxytocin might be evident only in individuals who are alcohol dependent and/or report some moderate levels of negative affect, anxiety or depression.

More broadly, the present study supports prior findings that the subjective and behavioral effects of intranasal oxytocin in humans are inconsistent and variable based on contextual and individual factors. In the present study, participants correctly indicated which drug they had received in the nasal spray only about 30% of the time. Similarly, in a recent meta-analysis of 38 clinical studies involving exogenous oxytocin administration, 93% of participants were unable to distinguish between oxytocin and placebo, and the hormone produced subtle and inconsistent behavioral effects (MacDonald et al., 2011). There are several possible reasons why it has been difficult to detect a robust effect of oxytocin. First, the effects may be subtle and not readily apparent using standard behavioral tasks. Further, the effects of oxytocin may depend on context (Bartz, Zaki, Bolger, & Ochsner, 2011; Bethlehem, Baron-Cohen, van Honk, Auyeung, & Bos, 2014) or individual factors, such as gender, attachment style, polymorphisms in the oxytocin receptor gene, and endogenous oxytocin levels (Bartz et al., 2011; Bethlehem et al., 2014; Feng et al., 2015; Olff et al., 2013; Sumracki, Gordon, Hull, Carter, & Tops, 2014). While our exploration of gender differences in self-reported subjective effects of oxytocin yielded no significant findings, our analyses may have been limited by the small sample size. It remains to be determined under what conditions this neuropeptide produces its behavioral effects.

Further complicating our interpretation of the present findings is the lack of empirical data on the pharmacokinetic profile of intranasal oxytocin in humans. Several small studies in non-human primates quantified the effect of intranasal oxytocin on central concentrations of the peptide, primarily via assaying the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). While some show increased CSF concentrations of oxytocin within 30–60 minutes of intranasal administration (Chang, Barter, Ebitz, Watson, & Platt, 2012; Dal Monte, Noble, Turchi, Cummins, & Averbeck, 2014; Freeman et al., 2016; Modi, Connor-Stroud, Landgraf, Young, & Parr, 2014), others show no significant changes (Dal Monte et al., 2014; Modi et al., 2014). A recent study demonstrated the penetrance of exogenous oxytocin into the central nervous system in rhesus macaques using isotope-labeled intranasal oxytocin (80 IU) (Lee et al., 2017). However, the pharmacokinetics of intranasal oxytocin are likely to be different in humans. Indeed, there is evidence that absorption of oxytocin can be enhanced simply by communicating to the participant to inhale during nasal administration (Guastella et al., 2013; Modi et al., 2014; Striepens et al., 2013), as was done in the current study. Although it is difficult to measure brain levels of peptides in humans, one study reported modest increases in CSF oxytocin in four participants 75 minutes following intranasal administration (Striepens et al., 2013). Nevertheless, the concentration reaching receptor targets in the brain is unknown, as is a complete understanding of oxytocin’s dose-response effects.

The present study had several limitations. First, we tested only a single dose of oxytocin. This dose (40 IU with 20 IU booster 75 minutes later) was based on published work (Churchland & Winkielman, 2012; Feifel et al., 2010; MacDonald et al., 2011; MacDonald et al., 2013), and the known short half-life of oxytocin (Arias, 2000; Churchland & Winkielman, 2012; Gossen et al., 2012). A complete determination of the effects of oxytocin should include a full dose-response function. Second, the tasks selected to detect alcohol-induced impairment were not highly sensitive and significant effects on performance were observed on only 2 of the 4 tasks. More sensitive measures might be needed to detect subtle effects of oxytocin on psychomotor and neurocognitive performance. Further, we did not assess performance before the sprays on each session, and so we could not rule out pre-spray baseline differences in the alcohol vs placebo groups. However, since we did not observe any effect of the spray, this is a minor concern. Third, the number of subjects was relatively small. None of our results suggest that we would detect effects in a larger sample. However, it is possible that effects may be observed in more demographically heterogeneous subjects, including those with heavier drinking histories or a higher level of anxiety or negative mood states.

The present study contributes to a growing body of literature on how oxytocin may affect drug and alcohol use. There is some evidence that oxytocin reduces craving for drugs among drug users under conditions of stress or anxiety (McRae-Clark et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2016; Pedersen et al., 2013), but not among users in non-stressed conditions (Lee et al., 2014; Woolley et al., 2016). The present findings indicate that the hormone has little effect in non-dependent social drinkers who are tested under stress-free conditions. Collectively, these findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the effects of exogenous oxytocin are dependent on contextual and individual factors, which must be considered when designing future studies. Further, oxytocinergic pathways may be altered by chronic drug and alcohol use, thus the effects of intranasal oxytocin are less evident in social or moderate users.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from NIDA (DA002812) awarded to HdW. AV is currently supported by a NIDA training grant (T32DA043469).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

Dr. de Wit has received support unrelated to this study from the following sources: Consulting fees from Marinius and Jazz Pharmaceuticals; gift of a study drug from Indivior; and support for a research study from Insys Therapeutics. Dr. King and Dr. de Wit have consulted for the FDA.

Reference List

- Aalto S, Ingman K, Alakurtti K, Kaasinen V, Virkkala J, Någren K, … Scheinin H. Intravenous Ethanol Increases Dopamine Release in the Ventral Striatum in Humans: PET Study Using Bolus-Plus-Infusion Administration of [11 C]raclopride. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. 2015;35(3):424–431. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias F. Pharmacology of Oxytocin and Prostaglandins. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2000;43(3):455–468. doi: 10.1097/00003081-200009000-00006. Retrieved from https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=10949750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi A. The oxytocin receptor impairs ethanol reward in mice. Physiology & Behavior. 2015;139:321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartz JA, Zaki J, Bolger N, Ochsner KN. Social effects of oxytocin in humans: context and person matter. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15(7):301–309. doi: 10.1016/J.TICS.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethlehem RAI, Baron-Cohen S, van Honk J, Auyeung B, Bos PA. The oxytocin paradox. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 2014;8:48. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethlehem RAI, van Honk J, Auyeung B, Baron-Cohen S. Oxytocin, brain physiology, and functional connectivity: a review of intranasal oxytocin fMRI studies. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(7):962–74. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezdjian S, Baker LA, Lozano DI, Raine A. Assessing inattention and impulsivity in children during the Go/NoGo task. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2009;27(2):365–383. doi: 10.1348/026151008X314919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boileau I, Assaad JM, Pihl RO, Benkelfat C, Leyton M, Diksic M, … Dagher A. Alcohol promotes dopamine release in the human nucleus accumbens. Synapse. 2003;49(4):226–231. doi: 10.1002/syn.10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen MT, Peters ST, Absalom N, Chebib M, Neumann ID, McGregor IS. Oxytocin prevents ethanol actions at δ subunit-containing GABAA receptors and attenuates ethanol-induced motor impairment in rats. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2015;112(10):3104–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416900112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumback T, Cao D, King A. Effects of alcohol on psychomotor performance and perceived impairment in heavy binge social drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91(1):10–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkett JP, Young LJ. The behavioral, anatomical and pharmacological parallels between social attachment, love and addiction. Psychopharmacology. 2012;224(1):1–26. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2794-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SWC, Barter JW, Ebitz RB, Watson KK, Platt ML. Inhaled oxytocin amplifies both vicarious reinforcement and self reinforcement in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109(3):959–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114621109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churchland PS, Winkielman P. Modulating social behavior with oxytocin: how does it work? What does it mean? Hormones and Behavior. 2012;61(3):392–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2011.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Monte O, Noble PL, Turchi J, Cummins A, Averbeck BB. CSF and Blood Oxytocin Concentration Changes following Intranasal Delivery in Macaque. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e103677. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wied D, Diamant M, Fodor M. Central Nervous System Effects of the Neurohypophyseal Hormones and Related Peptides. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 1993;14(4):251–302. doi: 10.1006/FRNE.1993.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen CW, Schultz DW. Information processing in visual search: a continuous flow conception and experimental results. Perception & Psychophysics. 1979;25(4):249–63. doi: 10.3758/bf03198804. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/461085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feifel D, Macdonald K, Nguyen A, Cobb P, Warlan H, Galangue B, … Hadley A. Adjunctive Intranasal Oxytocin Reduces Symptoms in Schizophrenia Patients. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(7):678–680. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng C, Lori A, Waldman ID, Binder EB, Haroon E, Rilling JK. A common oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) polymorphism modulates intranasal oxytocin effects on the neural response to social cooperation in humans. Genes, Brain, and Behavior. 2015;14(7):516–25. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT. Reliability of a computerized assessment of psychomotor performance and its sensitivity to alcohol-induced impairment. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 2003;97(1):21–34. doi: 10.2466/pms.2003.97.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Marczinski CA, Bowman AM. Acute tolerance to alcohol effects on inhibitory and activational mechanisms of behavioral control. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):663–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.663. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16331852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillmore MT, Weafer J. Acute tolerance to alcohol in at-risk binge drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):693–702. doi: 10.1037/a0026110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman MW, Foltin RW. Utility of subjective-effects measurements in assessing abuse liability of drugs in humans. Addiction. 1991;86(12):1563–1570. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox HC, Bergquist KL, Hong KI, Sinha R. Stress-Induced and Alcohol Cue-Induced Craving in Recently Abstinent Alcohol-Dependent Individuals. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31(3):395–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman SM, Samineni S, Allen PC, Stockinger D, Bales KL, Hwa GGC, Roberts JA. Plasma and CSF oxytocin levels after intranasal and intravenous oxytocin in awake macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016;66:185–194. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossen A, Hahn A, Westphal L, Prinz S, Schultz RT, Gründer G, Spreckelmeyer KN. Oxytocin plasma concentrations after single intranasal oxytocin administration – A study in healthy men. Neuropeptides. 2012;46(5):211–215. doi: 10.1016/J.NPEP.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grattan-Miscio KE, Vogel-Sprott M. Effects of alcohol and performance incentives on immediate working memory. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181(1):188–196. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella AJ, Hickie IB, McGuinness MM, Otis M, Woods EA, Disinger HM, … Banati RB. Recommendations for the standardisation of oxytocin nasal administration and guidelines for its reporting in human research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(5):612–625. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs M, Baumgartner T, Kirschbaum C, Ehlert U. Social support and oxytocin interact to suppress cortisol and subjective responses to psychosocial stress. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1389–98. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00465-7. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14675803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendler RA, Ramchandani VA, Gilman J, Hommer DW. Stimulant and Sedative Effects of Alcohol. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences. 2011;13:489–509. doi: 10.1007/7854_2011_135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, de Wit H, McNamara PJ, Cao D. Rewarding, Stimulant, and Sedative Alcohol Responses and Relationship to Future Binge Drinking. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):389. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King CE, Griffin WC, Luderman LN, Kates MM, McGinty JF, Becker HC. Oxytocin Reduces Ethanol Self-Administration in Mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2017;41(5):955–964. doi: 10.1111/acer.13359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Glassman M, King-Casas B, Kelly DL, Stein EA, Schroeder J, Salmeron BJ. Complexity of oxytocin’s effects in a chronic cocaine dependent population. European Neuropsychopharmacology: The Journal of the European College of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;24(9):1483–91. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Rohn MCH, Tanda G, Leggio L. Targeting the Oxytocin System to Treat Addictive Disorders: Rationale and Progress to Date. CNS Drugs. 2016;30(2):109–123. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0313-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MR, Scheidweiler KB, Diao XX, Akhlaghi F, Cummins A, Huestis MA, … Averbeck BB. Oxytocin by intranasal and intravenous routes reaches the cerebrospinal fluid in rhesus macaques: determination using a novel oxytocin assay. Molecular Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1038/mp.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lee MR, Weerts EM. Oxytocin for the treatment of drug and alcohol use disorders. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2016;27(8):640–648. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald E, Dadds MR, Brennan JL, Williams K, Levy F, Cauchi AJ. A review of safety, side-effects and subjective reactions to intranasal oxytocin in human research. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2011;36(8):1114–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald K, MacDonald TM, Brüne M, Lamb K, Wilson MP, Golshan S, Feifel D. Oxytocin and psychotherapy: A pilot study of its physiological, behavioral and subjective effects in males with depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(12):2831–2843. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFadyen K, Loveless R, DeLucca B, Wardley K, Deogan S, Thomas C, Peris J. Peripheral oxytocin administration reduces ethanol consumption in rats. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2016;140:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magrys SA, Olmstead MC. Acute stress increases voluntary consumption of alcohol in undergraduates. Alcohol and Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire) 2015;50(2):213–8. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann RE, Vogel-Sprott M. Control of alcohol tolerance by reinforcement in nonalcoholics. Psychopharmacology. 1981;75(3):315–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00432446. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6798624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CS, Earleywine M, Musty RE, Perrine MW, Swift RM. Development and Validation of the Biphasic Alcohol Effects Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17(1):140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maylor EA, Rabbitt PM. Alcohol, reaction time and memory: a meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychology (London, England: 1953) 1993;84(Pt 3):301–17. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1993.tb02485.x. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8401986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae-Clark AL, Baker NL, Maria MMS, Brady KT. Effect of oxytocin on craving and stress response in marijuana-dependent individuals: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology. 2013;228(4):623–631. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3062-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melis MR, Melis T, Cocco C, Succu S, Sanna F, Pillolla G, … Argiolas A. Oxytocin injected into the ventral tegmental area induces penile erection and increases extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus of male rats. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26(4):1026–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Bershad A, King AC, Lee R, de Wit H. Intranasal oxytocin dampens cue-elicited cigarette craving in daily smokers. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2016;27(8):697–703. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell IJ, Gillespie SM, Abu-Akel A. Similar effects of intranasal oxytocin administration and acute alcohol consumption on socio-cognitions, emotions and behaviour: Implications for the mechanisms of action. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2015;55:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Arcuni PA, Weinstein D, Woolley JD. Intranasal Oxytocin Selectively Modulates Social Perception, Craving, and Approach Behavior in Subjects With Alcohol Use Disorder. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2016;10(3):182–189. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi ME, Connor-Stroud F, Landgraf R, Young LJ, Parr LA. Aerosolized oxytocin increases cerebrospinal fluid oxytocin in rhesus macaques. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;45:49–57. doi: 10.1016/J.PSYNEUEN.2014.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, Corbin WR, Treat TA. The Subjective Effects of Alcohol Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation of a novel assessment tool for measuring subjective response to alcohol. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25(3):780–795. doi: 10.1037/a0032542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, Sofuoglu M, Rueger SY, O’Malley SS. The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology. 2013;227(1):177–192. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller ST, Piper BJ. The Psychology Experiment Building Language (PEBL) and PEBL Test Battery. Journal of Neuroscience Methods. 2014;222:250–259. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2013.10.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olff M, Frijling JL, Kubzansky LD, Bradley B, Ellenbogen MA, Cardoso C, … van Zuiden M. The role of oxytocin in social bonding, stress regulation and mental health: An update on the moderating effects of context and interindividual differences. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38(9):1883–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA. Oxytocin, Tolerance, and the Dark Side of Addiction. International review of neurobiology. 2017;136:239–274. doi: 10.1016/bs.irn.2017.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen CA, Smedley KL, Leserman J, Jarskog LF, Rau SW, Kampov-Polevoi A, … Garbutt JC. Intranasal Oxytocin Blocks Alcohol Withdrawal in Human Subjects. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37(3):484–489. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01958.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters ST, Bowen MT, Bohrer K, McGregor IS, Neumann ID. Oxytocin inhibits ethanol consumption and ethanol-induced dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Addiction Biology. 2017;22(3):702–711. doi: 10.1111/adb.12362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper BJ, Mueller ST, Geerken AR, Dixon KL, Kroliczak G, Olsen RHJ, Miller JK. Reliability and validity of neurobehavioral function on the Psychology Experimental Building Language test battery in young adults. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1460. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson HH, Tolliver GA, Haraguchi M, Hodge CW. Alcohol self-administration: role of mesolimbic dopamine. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1992;654:242–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb25971.x. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1352952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarnyai Z, Kovács GL. Oxytocin in learning and addiction: From early discoveries to the present. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2014;119:3–9. doi: 10.1016/J.PBB.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer TA, Vogel-Sprott M. Alcohol-impaired speed and accuracy of cognitive functions: A review of acute tolerance and recovery of cognitive performance. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2008;16(3):240–250. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer TA, Vogel-Sprott M, Danckert J, Roy EA, Skakum A, Broderick CE. Neuropsychological Profile of Acute Alcohol Intoxication during Ascending and Descending Blood Alcohol Concentrations. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31(6):1301–1309. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman BJ, Baker NL, McRae-Clark AL. Effect of oxytocin pretreatment on cannabis outcomes in a brief motivational intervention. Psychiatry Research. 2017;249:318–320. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-Back. In: Litten RZ, Allen JP, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens DN, Crombag HS, Duka T. The Challenge of Studying Parallel Behaviors in Humans and Animal Models. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2011. pp. 611–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson JR, Wenner SM, Freestone DM, Romaine CC, Parian MC, Christian SM, … O’Kane CM. Oxytocin reduces alcohol consumption in prairie voles. Physiology & Behavior. 2017;179:411–421. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striepens N, Kendrick KM, Hanking V, Landgraf R, Wüllner U, Maier W, Hurlemann R. Elevated cerebrospinal fluid and blood concentrations of oxytocin following its intranasal administration in humans. Scientific Reports. 2013;3(1):3440. doi: 10.1038/srep03440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumracki NM, Gordon JJ, Hull PR, Carter CS, Tops M. Individual differences underlying susceptibility to addiction: Role for the endogenous oxytocin system. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2014;119:22–38. doi: 10.1016/J.PBB.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó G, Kovács GL, Székeli S, Telegdy G. The effects of neurohypophyseal hormones on tolerance to the hypothermic effect of ethanol. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY) 1985;2(4):567–74. doi: 10.1016/0741-8329(85)90082-5. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4026981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabó G, Kovács GL, Telegdy G. Intraventricular administration of neurohypophyseal hormones interferes with the development of tolerance to ethanol. Acta Physiologica Hungarica. 1989;73(1):97–103. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2711843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirelli E, Jodogne C, Legros JJ. Oxytocin blocks the environmentally conditioned compensatory response present after tolerance to ethanol-induced hypothermia in mice. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 1992;43(4):1263–7. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90512-e. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1361994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban NBL, Kegeles LS, Slifstein M, Xu X, Martinez D, Sakr E, … Abi-Dargham A. Sex Differences in Striatal Dopamine Release in Young Adults After Oral Alcohol Challenge: A Positron Emission Tomography Imaging Study With [11C]Raclopride. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;68(8):689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viero C, Shibuya I, Kitamura N, Verkhratsky A, Fujihara H, Katoh A, … Dayanithi G. REVIEW: Oxytocin: Crossing the bridge between basic science and pharmacotherapy. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2010;16(5):e138–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Gallo DA, de Wit H. Effect of Alcohol on Encoding and Consolidation of Memory for Alcohol-Related Images. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(7):1540–7. doi: 10.1111/acer.13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley JD, Arcuni PA, Stauffer CS, Fulford D, Carson DS, Batki S, Vinogradov S. The effects of intranasal oxytocin in opioid-dependent individuals and healthy control subjects: a pilot study. Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(13):2571–2580. doi: 10.1007/s00213-016-4308-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KK, Kareken DA, Seyoum RA, O’Connor SJ, Wang C, Zheng QH, … Morris ED. Dopamine D2 Receptor Availability is Associated with Subjective Responses to Alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical & Experimental Research. 2005;29(6):965–970. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000171041.32716.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]