Abstract

Background

Drinking is a common activity with friends or at home but is associated with harms within both close and extended relationships. This study investigates associations between having a close proximity relationship with a harmful drinker and likelihood of experiencing harms from known others’ drinking for men and women in ten countries.

Methods

Data about alcohol’s harms to others from national/regional surveys from ten countries were used. Gender-stratified random-effects meta-analysis compared the likelihood of experiencing each, and at least one, of seven types of alcohol-related harm in the last 12 months, between those who identified someone in close proximity to them (a partner, family member or household member) and those who identified someone from an extended relationship as the most harmful drinker (MHD) in their life in the last 12 months.

Results

Women were most likely to report a close male MHD while men were most likely to report an extended male MHD. Relatedly, women with a close MHD were more likely than women with an extended MHD to report each type of harm, and one or more harms, from others’ drinking. For men, having a close MHD was associated with increased odds of reporting some but not all types of harm from others’ drinking, and was not associated with increased odds of experiencing one or more harms.

Conclusions

The experience of harm attributable to the drinking of others differs by gender. For preventing harm to women, the primary focus should be on heavy or harmful drinkers in close proximity relationships; for preventing harm to men, a broader approach is needed. This and further work investigating the dynamics among gender, victim-perpetrator relationships, alcohol and harm to others will help to develop interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm to others which are specific to the contexts within which harms occur.

Keywords: alcohol, harm to others, gender, family, meta-analysis

Introduction

Problematic alcohol use, drinking that has potential to result in health or social problems to the individual or collective (WHO, 2018), can affect others around the drinker (Room et al., 2010, Room et al., 2016, Greenfield et al., 2009). While there is a significant body of research focusing on understanding and treating the drinker, there is increasing interest in understanding the effect of problematic alcohol use on others around the drinker (Laslett et al., 2013). People’s drinking may negatively affect the health and wellbeing of others through a variety of avenues – such as physically via inter-personal violence, traffic accidents, and foetal alcohol syndrome; financially via alcohol-related property damage; emotionally via neglect; and socially via social embarrassment (Laslett et al., 2011, Rehm et al., 2009). Problematic alcohol use can harm people in close proximity to the drinker, such as partners and other family or household members (Greenfield et al., 2015, Laslett et al., 2011) as well as people in the drinker’s extended relationships, such as friends and co-workers, or more distant relatives (Dale & Livingston, 2010; Laslett et al., 2010).

Being in a close relationship with someone who engages in problematic alcohol use or whose drinking has harmed others (hereinafter referred to as ‘harmful drinkers’) increases one’s risk of experiencing harms from others’ drinking (Casswell et al., 2011, Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2017). Decades of research have shown that problematic alcohol use is a contributing factor to violence within family and intimate relationships (Leonard and Quigley, 2017) and to the severity of this violence (Foran and O’Leary, 2008, Graham et al., 2011). Specific family members may be more at risk than others of adverse impacts from the problematic alcohol use of people close to them, and these risks are likely to differ according to the gender of the victim and the drinker (Berends et al., 2012, Berends et al., 2014).

The role of gender in alcohol-related harms is complex. Men and women commonly drink different amounts, in different settings with different people, and these drinking patterns vary greatly across countries (WHO, 2014). Historically, men have drunk more than women and caused more problems and harm (Nicholls, 2008, Room et al., 2011, Nicholls, 2009, Obot and Room, 2005, AIHW, 2014, Wilsnack et al., 2009). The gender of the drinker and the type of drinking context is likely to affect who is harmed (Crane et al., 2016, Karriker-Jaffe and Greenfield, 2014). For instance, when men drink at home they are more likely to affect family members, especially spouses and children, while if they drink with other friends and work colleagues, they are more likely to affect other men, including strangers and acquaintances.

The interplay between the gender of victims and perpetrators, and the types, severity and nature of harms experienced from the drinking of people from close social relationships, and from extended social relationships – that is, those who are known to the respondent that are not family members or intimate partners, such as friends, distant relatives, colleagues and acquaintances – is less-comprehensively researched. Some research suggests that men are more likely than women to experience aggression from other men who had been drinking in bars or public places, such as strangers or friends and acquaintances from their extended social relationships, whereas women are more likely to experience aggression from a male that is a spouse, partner or friend (Graham and Wells, 2001). Thus, physical harm from the drinking of people from close relationships and extended relationships may be experienced in different contexts and severity by men and women.

In summary, men’s and women’s relationships with harmful drinkers may differ, and the frequency and types of harms experienced because of the drinking of people in someone’s close versus extended social relationships may vary by the gender of the victim and the drinker. Thus, the risks of harm from others’ drinking associated with having a close proximity relationship or an extended relationship with a harmful drinker are likely to differ between men and women. Investigations of how gender and victim-perpetrator relationships interact and are associated with harm from others’ drinking can improve understandings of the specific contexts within which harm occurs, and help to develop avenues to reduce alcohol-related harm to others.

Aims

Using data from national/regional surveys from ten countries involving experiences of alcohol’s harms to others, this paper examines the associations between having a most harmful drinker (MHD) in one’s close relationships or extended relationships and likelihood of experiencing seven different types of harm from known people’s drinking, and whether these associations vary for men and women. We hypothesise that:

Women will be more likely to identify the MHD in their life as someone in a close relationship than someone in an extended relationship, while the reverse will be true for men;

Because harmful drinkers in close proximity relationships have more opportunity to cause harms to those close to them, both women and men with a MHD in a close relationship will be more likely to experience at least one harm from known people’s drinking than will those who only have a MHD in an extended relationship;

However, for some harms (e.g., physical violence) which are more likely to be experienced by women from a male family member or intimate partner and by men from other men, the risk associated with having a close MHD will be greater for women than men.

Materials and Methods

Datasets

This paper utilises data collected in ten countries (listed in Table 1) which conducted cross-sectional surveys measuring harm from others’ drinking. The construction and management of the multi-country data archive was completed as part of two large projects: the WHO/Thai Health Collaborative Study of Alcohol’s Harms to Others (described in detail in Callinan et al., 2016a) and the Alcohol’s Harm to Others: Multinational Cultural Contexts and Policy Implications (GENAHTO) project (described in Greenfield et al., 2017). The country-level studies – described in detail by Callinan et al. (2016a), Laslett et al. (2011), Kaplan et al. (2017) and Greenfield and Karriker-Jaffe (2015) – were conducted between 2008 and 2015 and used comparable versions of the same questionnaire, except for subtle alterations in item wording which were made to ensure each survey remained culturally applicable and sensitive to local norms. Within-regions, random digit dialling or multi-stage sampling was used in all country-level studies. Detailed methods for each of the ten countries are depicted in Table 1. In this paper, the individual study samples are referred to as countries. However, it is important to note that not all studies utilised a national sampling scope (see Table 1). Australia, New Zealand, USA, Lao PDR, Thailand, Vietnam and Sri Lanka used a national sampling scope and drew nationally representative samples. The Chilean and Indian samples were drawn from selected regions and were regionally representative. Nigeria used a regional sampling scope, however random selection was not followed within the household and thus may not be representative of the selected regions.

Table 1.

Data collection methods from each of the ten country-level cross-sectional survey studies of alcohol’s harms to others.

| Country | Data Collection | Sampling | Sample, N | N Negatively affected by a known heavy drinkera | % At least one of seven types of harmb (among a) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Scope | Response rate | |||||

| Australia | Oct 08–Dec 08c | National (7 states and 2 territories) | 35% | 2,622 | 761 | 63.8 |

| New Zealand | Sep 08–Mar 09c | National | 64% | 2,878 | 727 | 47.2 |

| Nigeria | Oct 12–Dec 13d | Regional (3 states, 1 in North, and 2 in South) | e | 2,269 | 695 | 62.7 |

| Chile | Oct 12–Sep 13d | Regional (7 cities & surrounding areas) | 72% | 1,461 | 496 | 51.7 |

| USA | Feb 15–Jun 15c | National (50 states and Washington DC) | 60%f | 2,565 | 349 | 74.3 |

| Lao PDR | Oct 13 –Nov 13d | National (3 regions, 3 provinces, 6 districts) | 99% | 1,212 | 158 | 76.3 |

| Thailand | Sep 12–Mar 13d | National (4 regions & Bangkok, 5 provinces, 15 districts) | 94% | 1,695 | 722 | 63.2 |

| Vietnam | Dec 12–May 13d | National (6 regions, 1 province per region) | 99% | 1,501 | 840 | 60.2 |

| India | Dec 13–Aug 14d | Regional (4 regions in Karnataka State) | 97% | 3,396 | 1,772 | 68.4 |

| Sri Lanka | Sep 13–Feb 14c | National (9 provinces, 21 districts) | 93% | 2,431 | 830 | 86.9 |

And identified the person whose drinking had harmed them the most in the last 12 months (MHD);

From known people’s drinking;

Survey administered via face-to-face interview;

Survey administered via computer-assisted telephone interview;

A response rate of 99% was reported among households where someone was home;

Cooperation rate (Kaplan et al., 2017).

Measures

Respondents who answered ‘yes’ to a question asking whether they knew a heavy drinker (defined in the questionnaire as a “problem drinker or someone who drinks large amounts of alcohol often”) that had negatively affected them in the last 12 months were asked to identify, from a selection of relationship categories, the person whose drinking had most negatively affected them (i.e., Most Harmful Drinker – MHD) (except Indian respondents who were all asked this item and given the option to select ‘not applicable’ if they had not been negatively affected). These responses were categorized in terms of relationship proximity between the MHD and the respondent as “close MHD” (immediate family member, other household member, or current or ex-intimate partner) or “extended MHD” (non-first degree relative such as grandparent, cousin, sibling-in-law or distant relative; friend that is not a household member; or other person such as a neighbour or co-worker). These categories may not reflect the quality or intimacy of the relationship.

Harms from known drinkers were measured in two ways. The first asked participants if they had experienced specific harms in the past 12 months, and if so, whether the drinker who harmed them was a family member or friend (i.e. someone they knew). Three outcomes were included from these questions:

Harmed physically – “has someone who had been drinking harmed you physically?”

Called names or insulted – “has someone who had been drinking called you names or otherwise insulted you?”

-

Felt threatened or afraid – “did you feel threatened or afraid because of someone’s drinking at home or in some other private setting?” (drinker was assumed to be a family member or friend, except for USA respondents who were asked this directly)

Harms from known drinkers were also assessed by asking respondents first whether they had been negatively affected by the drinking of someone they knew, and if so, had they experienced specific harms from a heavy drinker they knew. Four additional outcomes were derived from these variables:

Forced or pressured into sex – “were you forced or pressured into sex or something sexual because of any of these people’s drinking?”

Emotionally hurt or neglected – “were you emotionally hurt or neglected because of any of these people’s drinking?”

Had to leave home – “did you have to leave home to stay somewhere else because of someone in the household’s drinking?”

Had less money for household expenses – “was there less money for household expenses because of someone in the household’s drinking?”

Six of the seven harm items were asked equivalently in all surveys; however, “called names or insulted by a known drinker” from the Australian and New Zealand surveys could not be derived. Additionally, for Australia and New Zealand, items about harms from a known drinker (questions 1, 3–7) were asked only about the most harmful drinker, not all heavy drinkers known to the respondent.

A summary variable was created (1+ harms) which was scored as “yes” if the respondent reported experiencing at least one of the seven specific harms, “no” if they did not experience any of the seven specific harms, and missing if they did not experience any of the harms and were missing on more than one quarter of the items.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the samples, compare the percentage of men and women who experienced each of the seven different types of alcohol-related harm, and compare the percentage of men and women with a close male MHD, close female MHD, extended male MHD or extended female MHD.

Stratified bivariate logistic regression modelling and meta-analysis of individual participant data using the DerSimonian-Laird method of two-stage inverse-variance random-effects method (Fisher, 2015) were used to compare the relative likelihood by gender of experiencing each, and at least one (generally of seven types of) harm from known people’s drinking according to the proximity of the respondent’s relationship to the MHD, pooled across ten countries. Due to the differences in sampling and subtle survey differences across the countries or regions (see Table 1) random effects meta-analyses were conducted. The pooled estimates resulting from these analyses are interpreted as the mean estimates of the true varying effects across all countries. Due to the low number of respondents that reported experiencing each harm, it was not possible to conduct multivariate regression models controlling for potential confounding covariates without losing a large proportion (>5%) of the country samples because of inestimable regression coefficients. However, the bivariate associations between the proximity of relationship to the MHD and each, and at least one harm from known people’s drinking (plotted in Figure 2) were replicated using the portions of the samples with sufficient data to estimate these associations after controlling for the age, level of education and drinking pattern of respondents – no notable differences in the pooled effect estimates were found.

To investigate gender differences in the association between the proximity of relationship to the MHD and harm from known people’s drinking, an interaction term between gender and the proximity of relationship to the MHD was fitted in logistic regression models predicting physical harm and 1+ harms with interaction coefficients pooled across countries via the DerSimonian-Laird method described above.

Country-level and pooled meta-analysis estimates and accompanying I-squared statistics are presented in stratified forest plots. I-squared describes the percentage of the total variability in effect sizes due to true heterogeneity (between-studies variability not sampling error) – I-squared = 25%, 50%, and 75% indicates low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively. All estimates are weighted to adjust for participants’ probability of being selected to participate (according to the number of eligible persons present in the household) and non-response (to match the gender distribution in each country, and to match the national adult population distributions of age and geographic location for Australia, age, geographic location and ethnicity for New Zealand, and numerous variables for USA (Kaplan et al., 2017)). All reported N pertain to the unweighted samples. Significant differences in odds are indicated by confidence intervals of odds ratios which do not include one, and significant differences in percentages between groups are indicated by confidence intervals which do not overlap. Countries are arranged in tables and figures in descending order of per capita alcohol consumption according to published WHO estimates (WHO, 2014). All data analysis and construction of forest plots was completed using Stata version 14.0 (Stata Corp., 2015).

Results

The estimated percentage of respondents who experienced each and at least one of seven different types of harm from known people’s drinking in men and women in ten countries is depicted in Table 2. Combining men and women into single samples, the estimated percentage of respondents who had experienced at least one of seven types of harm from known people’s drinking (1+ harms) ranged from 12% in New Zealand to slightly below half (44%) in Sri Lanka.

Table 2.

Percentage (CI) of respondents who experienced seven different types of harm from known people’s drinking in the last 12 months, in ten countries by respondents’ gender.

| N | % Harmed physically | % Called names or insulted | % Felt threatened or afraid | % Forced or pressured into sex | % Emotionally hurt or neglected | % Had to leave home | % Had less money for household expenses | % At least one harm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | |||||||||

| Men | 1084 | 1 (1, 2) | n/a | 8 (6, 10) | 0 (0, 1) | 12 (10, 14) | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (1, 3) | 15 (13, 17) |

| Women | 1538 | 2 (1, 3) | n/a | 9 (7, 10) | 1 (1, 2) | 20 (18, 23) | 2 (1, 3) | 4 (3, 5) | 22 (20, 24) |

| New Zealand | |||||||||

| Men | 1135 | 1 (1, 2) | n/a | 4 (3, 6) | 1 (0, 1) | 7 (5, 9) | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (1, 2) | 10 (8, 12) |

| Women | 1743 | 1 (1, 2) | n/a | 6 (5, 8) | 0 (0, 1) | 11 (10, 13) | 3 (2, 4) | 3 (2, 4) | 14 (13, 16) |

| Nigeria | |||||||||

| Men | 1390 | 3 (2, 4) | 11 (9, 13) | 0 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | 17 (15, 20) | 5 (4, 6) | 5 (4, 7) | 23 (21, 26) |

| Women | 879 | 2 (1, 3) | 12 (10, 15) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 19 (16, 22) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 6) | 23 (20, 26) |

| Chile | |||||||||

| Men | 680 | 4 (2, 6) | 13 (11, 16) | 13 (11, 16) | 3 (2, 5) | 11 (9, 14) | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 6) | 28 (24, 32) |

| Women | 781 | 4 (2, 5) | 13 (11, 16) | 16 (13, 19) | 3 (2, 5) | 11 (9, 14) | 4 (3, 5) | 4 (3, 6) | 26 (23, 30) |

| USA | |||||||||

| Men | 1078 | 1 (1, 2) | 6 (5, 8) | 4 (3, 6) | 1 (0, 2) | 8 (6, 10) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 3) | 13 (10, 16) |

| Women | 1487 | 1 (1, 2) | 8 (6, 11) | 6 (5, 8) | 1 (0, 3) | 12 (10, 15) | 1 (1, 2) | 3 (2, 4) | 17 (14,20) |

| Lao PDR | |||||||||

| Men | 504 | 2 (1, 4) | 12 (9, 16) | 8 (6, 11) | 1 (1, 3) | 9 (7, 12) | 1 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 4) | 25 (21, 29) |

| Women | 708 | 2 (1, 3) | 10 (7, 12) | 6 (5, 9) | 1 (0, 2) | 8 (6, 11) | 2 (1, 4) | 2 (1, 4) | 19 (16, 23) |

| Thailand | |||||||||

| Men | 694 | 2 (1, 4) | 23 (20, 27) | 7 (5, 9) | 1 (0, 4) | 20 (17, 24) | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (1, 4) | 39 (35, 44) |

| Women | 1001 | 1 (1, 3) | 18 (15, 21) | 10 (8, 13) | 1 (1, 2) | 28 (25, 32) | 3 (2, 5) | 5 (4, 7) | 38 (35, 42) |

| Vietnam | |||||||||

| Men | 753 | 4 (2, 5) | 18 (15, 21) | 8 (6, 11) | 1 (0, 2) | 21 (18, 24) | 1 (0, 2) | 3 (2, 4) | 33 (29, 36) |

| Women | 748 | 7 (5, 10) | 23 (20, 26) | 14 (12, 17) | 3 (2, 5) | 35 (32, 39) | 4 (3, 6) | 8 (6, 11) | 41 (37, 45) |

| India | |||||||||

| Men | 1621 | 8 (6, 9) | 17 (15, 19) | 21 (19, 23) | 4 (3, 6) | 27 (25, 29) | 15 (13, 17) | 18 (16, 20) | 42 (40, 45) |

| Women | 1775 | 11 (10, 13) | 22 (20, 24) | 23 (21, 25) | 6 (5, 7) | 28 (26, 30) | 7 (6, 9) | 14 (12, 16) | 44 (41, 46) |

| Sri Lanka | |||||||||

| Men | 1191 | 5 (3, 6) | 23 (20, 26) | 11 (9, 14) | 3 (2, 4) | 33 (30, 37) | 9 (7, 11) | 17 (15, 20) | 48 (45, 51) |

| Women | 1240 | 4 (3, 6) | 23 (21, 26) | 11 (9, 13) | 7 (6, 9) | 33 (30, 36) | 4 (3, 6) | 17 (15, 19) | 40 (37, 43) |

n/a: Equivalent variable not able to be derived.

As shown in Table 2, based on non-overlapping confidence intervals, a significantly larger percentage of women than men reported 1+ harms from a known drinker in three countries (Australia, New Zealand and Vietnam) while a larger percentage of men than women reported 1+ harms in one country (Sri Lanka, only); for the other six countries, there was no evidence of a gender difference in the percentage of respondents who experienced 1+ harms.

In most countries there was no statistically significant difference between the percentage of men and women who had felt afraid or threatened or been physically, verbally, sexually or emotionally harmed by a known person’s drinking. However, the number of respondents reporting these types of harms was quite low, and, in countries where a gender difference was observed, these harms were in every case more prevalent among women than men.

Differences in the percentage of men compared to women who reported harms that specifically pertained to experiences in the household were less consistent – in some countries, a greater percentage of women than men reported having less money for household expenses or having to leave because of a household member’s drinking, whereas in other countries the percentage of respondents that experienced these harms was greater among men than women.

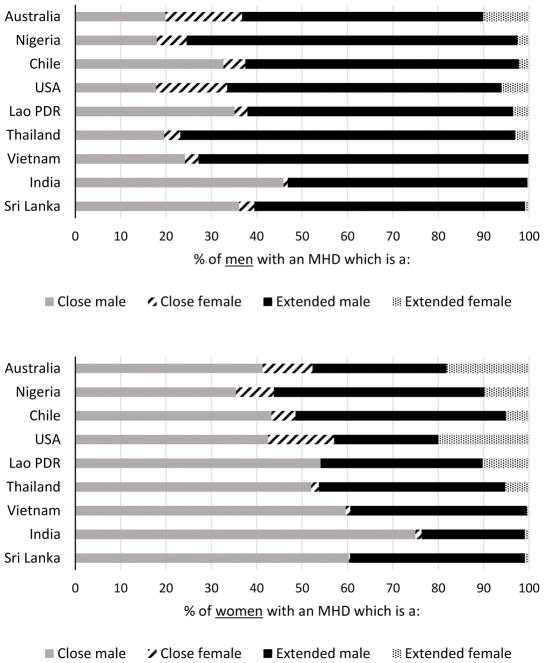

The gender of the MHD and relationship proximity of the MHD to the respondent among men and women is shown in Figure 1. The majority of the MHDs reported by both men and women were male. The main difference by gender is that men were consistently more likely to report that their MHD was a male from an extended relationship than a close male, close female or extended female (in all countries except India where men were equally likely to have a close or extended male MHD). In contrast, women were more or at least equally likely to report that their MHD was a close male than a close female, extended male or extended female. A detailed description of the sociodemographic and drinking characteristics of respondents who had a close MHD and respondents who had an extended MHD is provided in Supplementary Table S-1.

Figure 1.

Percentages (stacked) among men and women that identified the most harmful drinker in their life (MHD) as a close male, close female, extended male or extended female.

Among respondents who indicated they knew a heavy drinker that had negatively affected them; Gender of MHD not asked in New Zealand survey.

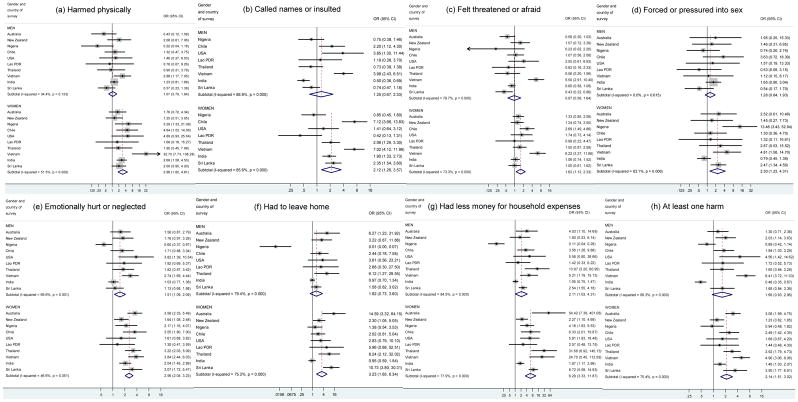

Figure 2 presents the estimated likelihood of experiencing each, and at least one, of seven different types of harms from known people’s drinking for respondents with a close MHD compared to those with an extended MHD. Pooling the estimates across ten countries, women with a close MHD were significantly more likely to have experienced 1+ harms from a known drinker than women with an extended MHD (Figure 2h). While there was high between-country heterogeneity in the size of the effect (I-squared = 75.4%), the estimated direction of association was consistent across all countries except one (Nigeria), and the confidence intervals indicated a significantly increased odds in six countries.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of men’s and women’s likelihood (bivariate odds ratio) of experiencing each (a–g), and at least one (h), of seven types of harm from known people’s drinking in the last 12 months if they had a close most harmful drinker (MHD) compared to an extended MHD, pooled across ten countries.

Called names or insulted not able to be derived for Australia and New Zealand; Countries with insufficient data due to zero cell counts are excluded from the applicable model(s); Weights of the contribution of country-level estimates to pooled estimates are represented by the relative area of the corresponding grey square.

Across countries, men with a close MHD were not more likely than men with an extended MHD to have experienced 1+ harms at the 5% confidence level (but the difference was close to significant (p = 0.08)). Men with a close MHD were at significantly increased odds of harm compared to men with extended MHDs in four countries. However, having an extended MHD was associated with a significantly increased odds for men from India, and there was very high heterogeneity in the size and direction of effect across countries (I-squared = 89.3%). Furthermore, pooling the estimates across countries, gender was not found to interact with the association between having a close MHD versus extended MHD and odds of experiencing 1+ harms from known people’s drinking (pooled interaction coefficient = 1.34, 95% CI = 0.87, 2.05, p = 0.18, I-squared = 62.3%; results not shown).

Figure 2h was replicated using an outcome variable for 1+ of six harms (excluding called names or insulted) and no major differences to the pooled ORs were observed (men OR = 1.56 vs. 1.66, women OR = 2.30 vs. 2.14).

The likelihood of being physically harmed by a close MHD compared to an extended MHD is presented in Figure 2a. Pooling estimates across ten countries, for women, having a close MHD, rather than an extended MHD, is associated with being at three times greater odds of being physically harmed by a known person’s drinking in the last 12 months. The effect was fairly consistent across countries – having a close MHD was associated with significantly greater odds of physical harm among Nigerian, Chilean, Vietnamese and Indian women, the point estimates of women from all other countries were in the same direction, and there was moderate heterogeneity in the size of the effect (I-squared = 51.5%).

Pooling the estimates across ten countries, the proximity of men’s relationship to their MHD was not associated with a greater likelihood of being physically harmed because of a known person’s drinking. While in Vietnam men were more likely to have been physically harmed if they had a close MHD than if they had an extended MHD, no significant association was consistently found in the remaining nine countries (I-squared = 34.4%).

In terms of gender differences, there was a strong interaction effect of the gender of the respondent on the association between having a close MHD versus extended MHD and odds of being physically harmed by a known drinker (pooled interaction coefficient = 3.06, 95% CI = 1.78, 5.26, p < .001, I-squared = 21.7%). Pooling the interaction effect of gender across countries, respondents with a close MHD were more likely to be physically harmed by a known person’s drinking if they were a woman than a man, whereas respondents with an extended MHD were more likely to be physically harmed by a known person’s drinking if they were a man than a woman.

Pooled values of the estimated likelihood of experiencing each of the six other types of harm from known people’s drinking for respondents with a close MHD compared to those with an extended MHD are depicted in Figure 2(b–g). Women were at greater odds of experiencing each of the six other types of harms from known people’s drinking if they had a close MHD compared to an extended MHD. For men, having a close MHD was not significantly associated with greater odds of being called names or insulted, threatened or made afraid, forced or pressured into sex or having to leave home because of a known person’s drinking. However, across countries, men were significantly more likely to have been emotionally harmed or neglected and had less money for household expenses if they had a close MHD. Despite this, Nigerian men were significantly less likely to have been emotionally hurt or neglected, had to leave home, and had less money for household expenses, if they had a close MHD versus extended MHD. In contrast, Vietnamese men were significantly more likely to experience five types of harm from known people’s drinking if they had a close MHD versus extended MHD. For Vietnamese women, the odds associated with having a close MHD was equivalent to or higher than the largest value across women in the other nine countries for all harms (having to leave home was unable to be estimated for Vietnamese women).

Discussion

As hypothesized, men were consistently more likely to report that their MHD was a male in an extended relationship while women were more likely to report that their MHD was a male in a close relationship. This finding is consistent with previous work in Australia which found MHD’s were usually intimate partners and friends, and generally were males (Laslett et al., 2010).

Our second hypothesis was also partly supported in that, in general, those who had a close MHD were more likely than those with an extended MHD to experience at least one of the seven harms. However, this relationship was significant for women but not men, and was more consistent across countries for women than for men – reflecting the greater likelihood that men would have an extended rather than a close MHD. Men with extended MHDs were significantly more likely to experience 1+ harms in India.

Our third hypothesis was also supported in that for some harms (e.g., physical violence) which are more likely to be experienced by women from a male family member or intimate partner and by men from other men, the risk associated with having a close MHD will be greater for women than men, and the risk associated with having an extended MHD will be greater for men than women.

Associations among gender, relationship proximity to harmful drinkers and specific alcohol-related harm from others

Gender was not found to interact with the association between relationship proximity to the MHD and risk of experiencing at least one of the seven harms from known people’s drinking. However, having a close MHD was associated with a significantly increased risk of experiencing at least one of the seven harms from known people’s drinking among women, but not among men. Being in close proximity (vs. more distal proximity) to a MHD may increase one’s exposure to the heavy/harmful drinking occasions of their MHD and therefore lead to greater opportunity to be harmed by their drinking. Despite this, men with an extended MHD and men with a close MHD had a similar risk of experiencing at least one harm from known people’s drinking. It might be that men’s extended MHDs are often friends, distal relatives, colleagues or acquaintances whom they drink with (and perhaps frequently or heavily). Therefore, while men with extended MHDs may spend similar or less time with their MHD than men with a close MHD, a relatively high proportion of this time might be spent while drinking. Thus, men with close and extended MHDs may be exposed to a similar level of their MHD’s heavy or harmful drinking occasions. Relatedly, men may be more likely to experience certain types of harms from known people’s drinking according to whether they have a close or extended MHD. Indeed, men with a close MHD were at significantly greater odds of financial and emotional harm than men with an extended MHD, but they were equally likely to experience physical harm, being called names or insulted, being threatened or afraid, forced into sex, or having to leave home (harms arguably likely to have more severe negative consequences for the victim).

Two of the harm items (having to leave home and having less money for household expenses) refer to experiences in the home, and two more (being forced or pressured into sex and emotionally hurt or neglected) might be disproportionately experienced by those with an intimate partner, whether or not their partner drinks heavily. Alternatively, people may feel pressured to have sex by others outside of the domestic context, such as at a bar.

For women, the largest increased risk of harm associated with having a close MHD (vs. an extended MHD) is for financial harm. To have less money for household expenses because of someone’s drinking requires the drinker being in the household. Those with a close MHD may be much more likely to experience financial harm from a known person’s drinking than those with an extended MHD because respondents may share expenses with a close MHD but not with an extended MHD.

For women, having a close MHD (vs. an extended MHD) was associated with an increased risk of being threatened or made afraid because of a known person’s drinking. The elevation in risk was relatively small in comparison to the risk associated with the other harms considered in this study. This indicates women may experience threatening behaviour and other actions that induce fear because of others’ drinking in a variety of contexts. The relatively high percentage of women with a close MHD that were harmed physically is important in light of the finding that women are more likely than men to have a male MHD who is close.

Respondents with a close MHD were more likely to be physically harmed by a known person’s drinking if they were a woman than if they were a man, whereas respondents with an extended MHD were more likely to be physically harmed if they were a man than if they were a woman. This finding is consistent with Canadian men’s and women’s descriptions of their most recent incident of physical aggression (with or without alcohol involvement) – men were more likely than women to report incidents with friends rather than with an intimate partner and women were more likely to report incidents with intimate partners (Graham and Wells, 2001).

Cross-country variation in associations among gender, relationship proximity to harmful drinkers and harm from known people’s drinking

While associations among gender, relationship proximity to harmful drinkers and alcohol-related harm were relatively consistent across countries, there was some cross-country variation in effect magnitude and direction. Numerous social and cultural factors may underpin the observed variation. Associations among gender, relationships and harm from others’ drinking may vary across countries due to differing drinking norms, drinking cultures and social roles and contexts across countries (Bloomfield et al., 2005, Obot and Room, 2005, Orford et al., 2005). Furthermore, while there are likely some consistencies in gender-specific roles and perceptions related to drinking across countries (Wilsnack et al., 2000), the extent of these differences may vary, especially given the changes in women’s role in western societies during the 20th century (Room, 2010, Ames and Rebhun, 1996, Rotskoff, 2002).

Specifically, having a close MHD may be more strongly related to harms in some drinking cultures than in others. In cultures where the activity of drinking is typically carried out away from home, for those with a close MHD, the risk of those harms which are only experienced when in close physical proximity to the MHD may tend to be lower than in cultures where drinking in the home is commonplace and more time is spent with the MHD whilst they are drinking. Alcohol consumption in the home is commonplace in Australia (Room, 2010, Callinan et al., 2016b) and the US (Rotskoff, 2002). This is in contrast to Nigeria, where, drinking has historically centred around festivals, rituals and important ceremonies, and where, more-recently, daily or near daily drinking at a bar is more common than at home (Ibanga et al., 2005). In India, the majority of men’s drinking occasions were in bars, pubs or the workplace, and men more commonly drank with friends and workmates than with a spouse or family members (Benegal et al., 2005). In contrast, a slightly higher percentage of women’s drinking occasions were in their own home or at mealtimes than in in bars, pubs or the workplace, and a similar percentage of women’s drinking occasions were with a spouse or family members as with friends or workmates (Benegal et al., 2005). Thus, it is to be expected to find a stronger association between having a close MHD and likelihood of experiencing at least one harm from known people’s drinking in countries where drinking usually takes place in the home (for example, Australia and the US), and that having an extended MHD is associated with risk of harm from known people’s drinking among Indian men but not in other cultures. Vietnamese drinking contexts may explain why having a close MHD was strongly associated with harms from known people among Vietnamese women and men, although literature describing Vietnamese drinking contexts and culture in particular is scarce (Lincoln, 2016). Anecdotal reasoning suggests that some alcohol-related misbehaviour to others within the family or domestic setting may be more forgivable than alcohol-related misbehaviour outside of the household boundary. Thus, normalisation of drinking within the household may underpin the strong association between having a close MHD and risk of harm from known people’s drinking among Vietnamese respondents.

More subjective experiences of harm (such as being emotionally hurt) are at least partially dependent on expectations not being met and these expectations may vary systematically across cultures (Room et al., 2016). It is plausible that men and women might be more or less likely to acknowledge alcohol as a cause for their experiences of harm from others depending on the country and culture they live in. For example, in countries where non-alcohol-related harm is common, or where heavy drinking is pervasive and well accepted, people might be more likely to conclude that the individual caused the harm, not their drinking. Therefore, cross-country variation in gender roles and perceptions related to drinking, expectations of relationships, and rates of harm to others from all causes likely underlie some of the cross-country variation in the associations investigated in this study.

While the primary focus of this study was to investigate associations between the proximity of relationship to the MHD and harm from others’ drinking by gender, the percentage of respondents reporting harms appeared to vary between the samples and thus warrants further investigation. Specifically, given that emotional hurt may affect wellbeing and social relationships (Mee et al., 2006) and was among the most commonly reported harm in these sample, the impacts of emotional harms due to others’ drinking across countries warrants further investigation.

Limitations

As with many international studies based on survey research, the comparability of surveys across countries is not perfect. In particular, Australian and New Zealand questions on harms were limited to harms attributable to the respondent’s MHD, while those in other countries were asked to report harms from any drinkers (and then asked whether they knew the perpetrator). This may be a contributing factor to the relatively low percentage of respondents that reported experiencing at least one of the seven harms observed in Australia and New Zealand and should be taken into account when interpreting results. While it is a limitation, it was necessary to include those countries whose surveys did not have harms specifically pertaining to the MHD to enable testing of associations within and across a broad range of countries and cultures.

Not all who said they were negatively affected by a known heavy drinker reported experiencing at least one of the seven types of harm from known people’s drinking included in this study (see Table 1). Therefore, there may be other types of harms from known people’s drinking not considered in this study that are related to the respondent’s gender and relationship proximity to the MHD, and future qualitative studies may compliment this study by building on understandings of the nature and extent of harms experienced from others’ drinking.

As demonstrated in Table 1, there are differences in administration from country to country that should also be noted, primarily the method of administration, and Australia’s low response rate, which is common in survey research in many English-speaking countries. While we do not expect differences in the method of survey administration to have significantly biased the associations reported in this study, we cannot be certain that a respondent may be equally likely to accurately recall particular information during a face-to-face interview versus a computer-assisted telephone interview. As social and cultural conditions of countries may change over time, so too may associations. Thus, the staggering of country-level studies between 2008 and 2015 is a limitation. Finally, there were some differences in the exact format of questions asked, as we have tried to make it clear wherever it could affect results.

Importantly, the results of this study describe associations between variables and do not infer that causal relationships exist between proximity to a MHD and harms from known people’s drinking.

A strength of this study is the inclusion of samples from a breadth of cultures, including countries from five different continents: Africa, Asia, Australasia/Oceania, North America and South America. The countries vary greatly on a number of socioeconomic measures such as age distribution, levels of educational attainment, drinking patterns and national economy (Supplementary Table S-2; WHO, 2014; World Bank, 2018), which facilitated discussion of the influence of cultural differences on the observed associations.

Elucidating the findings

While men and women are both more likely to report men as their MHD, this gender split obscures an important distinction in the gender difference in the relationship proximity of the harmful drinker to the respondent. Men were more likely to report that their MHD was a male in an extended relationship while women were more likely to report that their MHD was a male in a close relationship. This broad finding was reflected in the relative risk of physical harm which was more likely to come from a close harmful drinker than a distal harmful drinker for women and equally likely from a close or distal harmful drinker for men. In general, those who had a close MHD were more likely than those with an extended MHD to experience at least one of the seven harms; however, this relationship was significant for women but not men, and was more consistent across countries for women than for men – reflecting the greater likelihood that men would have an extended rather than a close MHD.

While associations among gender, relationships with harmful drinkers and alcohol-related harm appeared mostly consistent across countries, some inconsistencies were observed. There are many factors which may underpin these inconsistencies – such as variations in drinking contexts, gender roles, relationship norms and expectations, rates of harm from all causes, tolerance or sensitivity to harms and attribution of alcohol as a cause of harm.

Conclusions

These findings reinforce current concerns that alcohol-related harms to women stem largely from male intimate partners and family members, and such harms to men result more often from male friends, distal relatives and acquaintances (but also may be inflicted by family members). This broad gender difference is an important public health issue across many countries and cultures. Therefore, for preventing harm to women, the primary focus should be on drinkers in close relationships; for preventing harm to men, an environmental prevention approach which extends to public settings is needed. Further work investigating the dynamics among gender, victim-perpetrator relationships, alcohol and specific harms to others should be designed to help develop interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm to others which are specific to the contexts within which harm occurs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The data used in this paper are from the GENAHTO Project (Gender and Alcohol’s Harm to Others), supported by NIAAA Grant No. R01 AA023870 (Alcohol’s Harm to Others: Multinational Cultural Contexts and Policy Implications). GENAHTO is a collaborative international project affiliated with the Kettil Bruun Society for Social and Epidemiological Research on Alcohol and coordinated by research partners from the Alcohol Research Group/Public Health Institute (USA), University of North Dakota (USA), Aarhus University (Denmark), the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (Canada), the Centre for Alcohol Policy Research at La Trobe University (Australia), and the Addiction Switzerland Research Institute (Switzerland). Support for aspects of the project has come from the World Health Organization (WHO), the European Commission (Concerted Action QLG4-CT-2001-0196), the Pan American Health Organization, the Thai Health Promotion Foundation (THPF), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC Grant No. 1065610), and the U.S. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism/National Institutes of Health (Grants R21 AA012941, R01 AA015775, R01 AA022791, R01 AA023870, and P50 AA005595). Support for individual country surveys was provided by government agencies and other national sources. National funds also contributed to collection of all of the data sets included in WHO projects. Study directors for the survey data sets used in this paper have reviewed the paper in terms of the project’s objective and the accuracy and representation of their contributed data. The study directors and funding sources for data sets used in this report are: Australia (Robin Room, Anne-Marie Laslett, Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education and NHMRC Grant 1090904)); Chile (Ramon Florenzano, THPF, WHO); India (Vivek Benegal and Girish Rao, THPF, WHO); Lao PDR (Latsamy Siengsounthe, THPF, WHO); New Zealand (Sally Casswell and Taisia Huckle, Health Research Council of New Zealand); Nigeria (Isidore Obot and Akanidomo Ibanga, THPF, WHO); Sri Lanka (Siri Hettige, THPF, WHO); Thailand (Orratai Waleewong and Jintana Janchotkaew, THPF, WHO); the United States (Thomas Greenfield and Katherine Karriker-Jaffe, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism/National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01 AA022791)); Vietnam (Hanh T.M. Hoang and Hanh T.M. Vu, THPF, WHO). Opinions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, the National Institutes of Health, the WHO, and other sponsoring institutions. (GENAHTO survey information at https://genahto.org/abouttheproject/).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) National Drug Strategy Household Survey Detailed Report: 2013. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Canberra: 2014. Drug Statistics Series no. 28. Cat. no. PHE 183. [Google Scholar]

- Ames G, Rebhun L. Women, alcohol and work: interactions of gender, ethnicity and occupational culture. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43:1649–1663. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benegal V, Nayak M, Murthy P, Chandra P, Gururaj G. Women and alcohol use in India. In: Obot I, Room R, editors. Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspectives from Low and Middle Income Countries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Berends L, Ferris J, Laslett A-M. A problematic drinker in the family: variations in the level of negative impact experienced by sex, relationship and living status. Addiction Research & Theory. 2012;20:300–306. [Google Scholar]

- Berends L, Ferris J, Laslett A-M. On the nature of harms reported by those identifying a problematic drinker in the family, an exploratory study. Journal of Family Violence. 2014;29:197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield K, Allamani A, Beck F, Bergmark K, Csemy L, Eisenbach-Stangl I, Elekes Z, Gmel G, Kerr-Corrêa F, Knibbe R, Mäkelä P, Monteiro M, Medina Mora M, Nordlund S, Obot I, Plant M, Rahav G, Mendoza M. Gender, Culture and Alcohol Problems: A Multi-National Study. Charité Campus Benjamin Franklin; Berlin: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Callinan S, Laslett A-M, Rekve D, Room R, Waleewong O, Benegal V, Casswell S, Florenzano R, Hanh H, Hanh V. Alcohol’s harm to others: an international collaborative project. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research. 2016a;5:25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Callinan S, Livingston M, Room R, Dietze P. Drinking contexts and alcohol consumption: how much alcohol is consumed in different Australian locations? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016b;77:612–619. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2016.77.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casswell S, You R, Huckle T. Alcohol’s harm to others: reduced wellbeing and health status for those with heavy drinkers in their lives. Addiction. 2011;106:1087–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane C, Godleski S, Przybyla S, Schlauch R, Testa M. The proximal effects of acute alcohol consumption on male-to-female aggression: a meta-analytic review of the experimental literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2016;17:520–531. doi: 10.1177/1524838015584374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale C, Livingston M. The burden of alcohol drinking on co-workers in the Australian workplace. Med J Australia. 2010;193:138–140. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D. Two-stage individual participant data meta-analysis and generalized forest plots. Stata Journal. 2015;15:369–396. [Google Scholar]

- Foran H, O’Leary K. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: a meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Bernards S, Wilsnack S, Gmel G. Alcohol may not cause partner violence but seems to make it worse: a cross national comparison of the relationship between alcohol and severity of partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:1503–23. doi: 10.1177/0886260510370596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S. The two worlds of aggression for men and women. Sex Roles. 2001;45:595–622. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T, Bloomfield K, Wilsnack S. [Accessed December 13, 2017];Alcohol’s harms to others: multinational cultural contexts and policy implications (GENAHTO) project [Alcohol Research Group/Public Health Institute GENAHTO Web site] 2017 Available at: http://genahto.org/

- Greenfield T, Karriker-Jaffe K. 2015 national alcohol’s harm to others survey (NAHTOS) [Accessed December 13, 2017];[Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute Web site] 2015 Available at: http://arg.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/H2O_Qre_v9_FINAL-Rev.pdf.

- Greenfield T, Karriker-Jaffe K, Kaplan L, Kerr W, Wilsnack S. Trends in alcohol’s harms to others (AHTO) and co-occurrence of family-related AHTO: the four US National Alcohol Surveys, 2000–2015. Substance Abuse: Research and Treatment. 2015;9:23–31. doi: 10.4137/SART.S23505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield T, Ye Y, Kerr W, Bond J, Rehm J, Giesbrecht N. Externalities from alcohol consumption in the 2005 US National Alcohol Survey: implications for policy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2009;6:3205–3224. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6123205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanga A, Adetula A, Dagona Z, Karick H, Ojiji O. The contexts of alcohol consumption in Nigeria. In: Obot I, Room R, editors. Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspectives from Low and Middle Income Countries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan L, Nayak M, Greenfield T, Karriker-Jaffe K. Alcohol’s harm to children: findings from the 2015 United States National Alcohol’s Harm to Others Survey. Journal of Pediatrics. 2017;184:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K, Greenfield T, Kaplan L. Distress and alcohol-related harms from intimates, friends, and strangers. Journal of Substance Use. 2017;22:434–441. doi: 10.1080/14659891.2016.1232761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe K, Greenfield T. Gender differences in associations of neighbourhood disadvantage with alcohol’s harms to others: a cross-sectional study from the USA. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2014;33:296–303. doi: 10.1111/dar.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A-M, Callinan S, Pennay A. The increasing significance of alcohol’s harm to others research. Drugs and Alcohol Today. 2013;13:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A-M, Catalano P, Chikritzhs T, Dale C, Doran C, Ferris J, Jainullabudeen T, Livingston M, Matthews S, Mugavin J, Room R, Schlotterlein M, Wilkinson C. The Range and Magnitude of Alcohol’s Harm to Others. Alcohol Education and Rehabilitation Foundation; Canberra: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Laslett A-M, Room R, Ferris J, Wilkinson C, Livingston M, Mugavin J. Surveying the range and magnitude of alcohol’s harm to others in Australia. Addiction. 2011;106:1603–1611. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K, Quigley B. Thirty years of research show alcohol to be a cause of intimate partner violence: future research needs to identify who to treat and how to treat them. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2017;36:7–9. doi: 10.1111/dar.12434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln M. Alcohol and drinking cultures in Vietnam: a review. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016;159:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J. Vinum brittanicum: the “drink question” in early modern England. Social History of Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;22:190–208. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J. The Politics of Alcohol: A History of the Drink Question in England. Manchester University Press; Manchester: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mee S, Bunney B, Reist C, Potkin S, Bunney W. Psychological pain: A review of evidence. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2006;40:680–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obot I, Room R. Alcohol, Gender and Drinking Problems: Perspectives from Low and Middle Income Countries. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Orford J, Natera G, Copello A, Atkinson C, Mora J, Velleman R, Crundall I, Tiburcio M, Templeton L, Walley G. Coping with Alcohol and Drug Problems: The Experiences of Family Members in Three Contrasting Cultures. Routledge; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009;373:2223–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R. The long reaction against the wowser: the prehistory of alcohol deregulation in Australia. Health Sociology Review. 2010;19:151–163. [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Ferris J, Bond J, Greenfield T, Graham K. Differences in trouble per litre of different alcoholic beverages – a global comparison with the GENACIS dataset. Contemporary Drug Problems. 2011;38:493–516. doi: 10.1177/009145091103800403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Ferris J, Laslett A-M, Livingston M, Mugavin J, Wilkinson C. The drinker’s effect on the social environment: a conceptual framework for studying alcohol’s harm to others. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010;7:1855–1871. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7041855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Laslett A-M, Jiang H. Conceptual and methodological issues in studying alcohol’s harm to others. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;33:455–478. [Google Scholar]

- Rotskoff L. Love on the Rocks: Men, Women, and Alcohol in Post-World War II America. University of North Carolina Press; Chapel Hill: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stata Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 14. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. [Accessed April 11, 2018];Data bank: World Development Indicators [The World Bank Web site] 2018 Available at: http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=2&country=&series=NY.GNP.PCAP.CD&period=

- World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2014. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) [Accessed April 11, 2018];Lexicon of alcohol and drug terms published by the World Health Organization [World Health Organization Web site] 2018 Available at: http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/terminology/who_lexicon/en/

- Wilsnack R, Vogeltanz N, Wilsnack S, Harris R. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns. Addiction. 2000;95:251–265. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilsnack R, Wilsnack S, Kristjanson A, Vogeltanz-Holm N, Gmel G. Gender and alcohol consumption: patterns from the multinational GENACIS project. Addiction. 2009;104:1487–1500. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.