Abstract

Airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell hyperplasia driven by persistent inflammation is a hallmark feature of remodeling in asthma. Sex steroid signaling in the lungs is of considerable interest, given epidemiological data showing more asthma in pre-menopausal women and aging men. Our previous studies demonstrated that estrogen receptor (ER) expression increases in asthmatic human ASM; however, very limited data are available regarding differential roles of ERα vs. ERβ isoforms in human ASM cell proliferation. In this study, we evaluated the effect of selective ERα and ERβ modulators on platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-stimulated ASM proliferation and the mechanisms involved. Asthmatic and non-asthmatic primary human ASM cells were treated with PDGF, 17β-estradiol, ERα-agonist and/or ERβ-agonist and/or G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 30 (GPR30/GPER) agonist and proliferation was measured using MTT and CyQuant assays followed by cell cycle analysis. Transfection of small interfering RNA (siRNA) ERα and ERβ significantly altered the human ASM proliferation. The specificity of siRNA transfection was confirmed by Western blot analysis. Gene and protein expression of cell cycle-related antigens (PCNA and Ki67) and C/EBP were measured by RT-PCR and Western analysis, along with cell signaling proteins. PDGF significantly increased ASM proliferation in non-asthmatic and asthmatic cells. Treatment with PPT showed no significant effect on PDGF-induced proliferation, whereas WAY interestingly suppressed proliferation via inhibition of ERK1/2, Akt, and p38 signaling. PDGF-induced gene expression of PCNA, Ki67 and C/EBP in human ASM was significantly lower in cells pre-treated with WAY. Furthermore, WAY also inhibited PDGF-activated PCNA, C/EBP, cyclin-D1, and cyclin-E. Overall, we demonstrate ER isoform-specific signaling in the context of ASM proliferation. Activation of ERβ can diminish remodeling in human ASM by inhibiting pro-proliferative signaling pathways, and may point to a novel perception for blunting airway remodeling.

Keywords: ERα receptor, Estrogen, Asthma, Lung, PCNA, Sex steroids

Introduction

Asthma is characterized by a chronic inflammation of conducting airways in association with airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and remodeling (Prakash, 2016, Prakash and Martin, 2014, Prakash, 2013, Lazaar and Panettieri, 2005, Sathish et al., 2011, Dekkers et al., 2009). Structural changes in the airway walls, induced by a vicious circle of injury and repair processes collectively represent airway remodeling. Increased airway smooth muscle (ASM) mass is a hallmark of airway remodeling which causes airway narrowing and obstruction (Wang et al., 2016, Rydell-Törmänen et al., 2012). Altered extracellular matrix also contributes to airway remodeling in asthma (Gerthoffer, 2008, Hershenson et al., 2008, Koziol-White, Damera and Panettieri, 2011, Roscioni et al., 2010, Coraux et al., 2008, Bossé et al., 2008). Studies including our own supports the concept that ASM proliferation augments ECM generation and deposition in asthmatic airways (Dekkers et al., 2009, Rydell-Törmänen et al., 2012, Coraux et al., 2008, Bossé et al., 2008, Freeman et al., 2017, Royce et al., 2012, Lagente and Boichot, 2010). Multiple studies suggest that ASM cell migration towards the airway epithelium in response to inflammatory mediators, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) contributes to airway remodeling (Gerthoffer, 2008, Suganuma et al., 2012, Carlin, Roth and Black, 2003, Hirst, Barnes and Twort, 1992, Ingram and Bonner, 2006). As a result, the ASM layer in asthmatic patients is in close proximity to airway epithelial cells (Joubert and Hamid, 2005, James et al., 2002), which may lead to increased airway hyper-responsiveness. Thus better understanding of mechanisms that contribute to enhanced ASM proliferation are important in the context of developing novel strategies to address asthma.

An emerging aspect of asthma is the clinical recognition that prevalence of asthma is greater in boys than in girls during prepubescent ages (Sathish, Martin and Prakash, 2015, Bonds and Midoro-Horiuti, 2013, Bjornson and Mitchell, 2000, Caracta, 2003, Carey et al., 2007) with this trend reversing after puberty to become more prevalent in adult women (Sathish et al., 2015, De Marco et al., 2000, Melgert et al., 2007). In adult women, changes in symptom severity and number of exacerbations correlated to changes in hormonal status (phases of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and menopause) (Bjornson and Mitchell, 2000, Caracta, 2003, Carey et al., 2007, Townsend, Miller and Prakash, 2012). Thus, the potential role of sex steroids in the modulation of asthma pathophysiology becomes relevant in the context of understanding sex differences in this disease. Here, estrogens may be particularly important given clinical data showing that modulating estrogen levels correlate to changes in asthma symptoms.

The effect of estrogen is mediated by two receptors (estrogen receptors, ERα and β), which are known to act as ligand-dependent transcription factors (Laudet and Gronemeyer, 2002). However, several studies including our own have shown that ERs are also capable of acting in a non-genomic fashion, for example modulating calcium responses in ASM cells (Townsend et al., 2010, Townsend et al., 2012), and furthermore acting genomically to modulate signaling pathways relevant to airway disease (Sathish et al., 2015, Prossnitz et al., 2008, Marino, Galluzzo and Ascenzi, 2006).

Previously we showed that in human ASM, physiologically-relevant concentrations of estrogens act via ERs and the cAMP pathway to non-genomically reduce [Ca2+]i, thus promoting bronchodilation (Sathish et al., 2015, Townsend et al., 2010, Townsend et al., 2012). Our recent work showed the differential expression of ERα and ERβ in asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM, and found ERβ expression is significantly greater in asthmatic ASM in both males and females (Aravamudan et al., 2017), but the downstream signaling has not been elucidated. There have been studies demonstrating that 17β-estradiol increases ASM number (Stamatiou et al., 2011) and vascular smooth muscle proliferation (Cheng et al., 2009, Muka et al., 2016) while other studies show ERα and ERβ agonists causing significant inhibition of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (Muka et al., 2016, Li et al., 2017, Li et al., 2016). There are currently no data on ER effects on human ASM proliferation, especially in the context of inflammation or asthma. The present study hypothesizes that differential activation of ERs plays a role in ASM proliferation during inflammation. We investigated the role of estrogen along with ERα and ERβ agonists in human ASM proliferation in the presence of PDGF as mitogenic stimulus, with the idea that if ERβ is more abundant in asthmatic ASM, this receptor isoform has greater contribution towards ASM proliferation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals, drugs/inhibitors, antibodies

Cell culture reagents and other cell culture supplies including fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium F/12 (DMEM/F12) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Pharmacological agonists for ER and its isoforms such as 17β-estradiol (E2), ERα-agonist (PPT, Propyl pyrazole triol; THC, Tetra Hydro Chrysenediol), G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 30 (GPR30/GPER) agonist (G1), and ERβ-agonist (WAY-200070; FERB-033; DPN, Diaryl-Propio-Nitrile) were obtained from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN). Human recombinant PDGF-BB was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Pro-inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Dallas, TX). Chemicals and supplies were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise specified. ESR1, ESR2 and negative siRNA obtained from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA) and Ambion (Austin, TX, USA). Primary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (Dallas, TX) unless otherwise mentioned. Estrogen Receptor α Monoclonal Antibody (33, Catalog # MA1-310) and Estrogen Receptor β Monoclonal Antibody (PPZ0506, Catalog # MA5-24807) were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Akt1 (Cat# 9272S), pAkt1 (Cat# 4060S), p38 (Cat# 8690S), p-p38 (Cat# 4511S), antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling, β-actin antibody from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat# A5316), and the remainder (ERK1/2 (Cat# sc-94), pERK1/2 (Cat# sc-7383), PCNA (Cat# sc-25280), C/EBP (Cat# sc-365318) Cyclin-D1 (Cat# sc-8396), and Cyclin-E (Cat# sc-481)) from Santa Cruz. The secondary antibodies m-IgGκ-HRP (Cat# sc-516102), Goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (Cat# sc-2004) were obtained from Santa Cruz and ECL anti-mouse IgG-HRP (Cat# NA931V) from GE healthcare UK Ltd.

2.2 Human ASM cells

The technique for isolating human ASM cells has been previously described (Abcejo et al., 2012, Vohra et al., 2013, Sathish et al., 2015). Briefly, third to sixth generation human bronchi were obtained from lung specimens incidental to patient thoracic surgery at Mayo Clinic for focal, non-infectious causes (typically lobectomies for focal cancers). Normal lung areas were identified with the help of a pathologist (protocol approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board). We used samples from both male and female adults of ages from 21 to 60 yr. Samples were denuded of epithelium and ASM tissue enzymatically dissociated to generate cells that were used for experiments. For cells, cultures (<3rd passage) were maintained under standard conditions of 37°C (5% CO2, 95% air). Cells were serum starved for 24 h prior to experimentation. Experiments were conducted in Hanks’ Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)

2.3. Cell Treatment

Fully confluent T-75 flasks of ASM cells were trypsinized mixed in 10% FBS (Charcoal Stripped) Growth medium (DMEM/F12/1% AbAm), counted and seeded ~10,000 cells/well into 96-well culture plates. Cells were allowed to adhere overnight, washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (1× PBS) and incubated in serum free medium (without FBS) for 24h to mature and synchronize the growth of cells. ASM cells were treated with 17β-estradiol (E2, 1 nM), ERα-agonist (PPT, 10 nM), or ERβ-agonist (WAY, 10 nM), GPR30/GPER agonist (G1, 1 nM) with 1% FBS in the media. After 2 h of pre-incubation with respective treatment groups, cells were then exposed to PDGF (2 ng/ml) for 24 h. DMEM/F12 with 1% FBS alone served as a vehicle. For a set of experiments, 20 ng/ml TNFα, 50 ng/ml IL-13, 1 nM G1 and 10 nM each of THC, FERB-033 and DPN were used.

2.4. Small interfering RNA transfection

Technique to knock down the Estrogen receptor α and β by interfering RNA (siRNA) has also been previously described (Aravamudan et al., 2012). Briefly, human ASM cells were grown on 96 well plate or 100 mm plates to approximately 50% confluence. Transfection was achieved using 20 nM siRNA and Lipofectamine 3000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) in DMEM F-12 lacking FBS and antibiotics. Fresh growth medium was added after 6 h and cells analyzed after 48 h. ESR1 silencer select Pre-designed siRNA (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA, Catalog# 4392420), ON-TARGETplus Human ESR2 (2100) siRNA – Individual (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA, Catalog # J-003402-13-0005) were used to knock down Estrogen receptor α and β respectively. As a negative control, the Silencer Negative Control #1 (Cat# AM4611) from Ambion was used. Knockdown efficacy and specificity was verified by Western blot analysis. The effect of siRNA on proliferation in presence and absence of PDGF, WAY or PPT were analyzed by MTT assay method.

2.5. Cell proliferation assays

2.5.1. MTT Cell Proliferation Assay

After 24h treatment, the medium was aspirated and replaced with 100 μl of vehicle. A total of 10 μl MTT reagent (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl) -2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide, 5 mg/ml) was added to each well, and cells were incubated at 37°C for 4h. The medium in each well was then replaced with 100 μl DMSO. The plates were incubated on a shaker for 15 min at room temperature, and then absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a SpectraMax M5 automated microplate reader (Molecular Devises, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.5.2. CyQuant NF proliferation assay

In parallel to the above assay, cell proliferation was confirmed using CyQUANT® NF cell proliferation assay Kit (Molecular Probes; Invitrogen, USA) as per manufacturer’s protocol (Liu and Leung, 2015). Fluorescence intensity at 485 nm excitation was recorded using the plate reader. The serum-free media treated group was used for baseline measurement and the number of cells counted in this group was subtracted from all treated groups to get an estimated change in the rate of proliferation. Standard Calibration Curve: The standard calibration curve was plotted for both assay methods using a range of ASM cells (with 1250 – 40,000 cells/well). Cell numbers were determined using calibration curve and values normalized as described previously (Aravamudan et al., 2012).

2.6. Flow cytometry

Asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells were seeded in 12-well culture plates and treated with PPT or WAY with or without PDGF for 24 h along with vehicle control. Cells were harvested and fixed with ice-cold absolute ethanol to permeabilize cells, centrifuged, the resultant cell pellets washed with PBS, re-suspended in PBS and stained with propidium iodide (3 μM) for 15 min for analysis using a BD Accuri® C6 CFlow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA USA). Approximately 40,000 events were captured per sample and cells were analyzed for G1, S, G2/M phase using BD Accuri™ C6 Plus software.

2.7. RT-PCR Analysis

Cells were washed with RNA-grade DPBS, trypsinized and centrifuged. Total RNA was extracted using Quick-RNA™ MiniPrep kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) following manufacturer’s protocol and cDNA was synthesized using OneScript cDNA Synthesis Kit using 500 ng of quantified RNA (Take3™ Micro volume plate, Synergy HTX, Biotek, USA) for each sample (Applied Biological Materials Inc, Richmond, BC, Canada). LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master PCR kit (Cat# 0470751601) protocol was followed using QuantStudio 3 RT-PCR system as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The following primers were used for RT-PCR analysis: PCNA (forward 5′-GCC TGA ATG GCG AAT GGA-3′; reverse 5′-GAA GGG AAG AAA GCG AAA GGA-3′), Ki67 (forward 5′-GCT TAC TCC GAC CAT GAT TTC T-3′; reverse 5′-GCC GAT GCT TGC AAT AGT TTA G-3′), C/EBP (forward 5′-ATT GGA CCC AGA GAA GTT GAC-3′; reverse 5′-TCG GAC CAT TTA AGT CTT CAG AGA T-3′), s16 (forward 5′-CAA TGG TCT CAT CAA GGT GAA CGG-3′, reverse 5′-CTG GAT AGC ATA AAT CTG GGC-3′). The fold changes in mRNA expression were calculated by normalization of cycle threshold [C(t)] value of target genes to reference gene s16 using the ΔΔCt method.

2.8. Western analysis

Previously described techniques were used (Aravamudan et al., 2017). Briefly, cells were washed, sonicated in lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technologies, Beverly, MA, USA) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and resultant supernatants were assayed for total protein content using the DC Protein Assay kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). 30 μg equivalent protein from each lysate were loaded on 10% SDS-page and transferred onto 0.22 μm PVDF membranes. Non-specific binding was blocked using 5.0% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and the membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with specific antibodies of interest. Blots were then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. β-actin was used as loading control. Protein expression was detected using Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz, then exposed to UltraCruz Autoradiography Film (Santa Cruz), and scanned for densitometry analysis using ImageJ 1.50i software with integrated density values normalized for loading control and phosphorylated proteins. The ratios obtained for western blot analysis were first normalized by dividing the raw values of proteins of interest with the raw values of either β-Actin or the total protein. The obtained values were then normalized to vehicle.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in human ASM cells from three or more patients (non-asthmatic and asthmatic). “n” values represent patients numbers for individual experiments. All proliferation experiments were repeated at least three times for each patient sample and minimum of two times for westen blot, real time qPCR and flow cytometry experiments. Statistical analysis was performed using a Sigma Plot (SYSTAT, San Jose, CA) software statistical package. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using individual one way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc test. Statistical significance was tested at mimimum of p<0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of TNFα, IL-13 and PDGF on human ASM cell proliferation

There was a significant increase in cell proliferation after 24 h treatment with TNFα and PDGF in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic patients compared to vehicle (Figure 1A and 1B). This mitogenic effect was considerably higher in the PDGF treated group (30–40 percent more in asthmatic and 20–30 percent more in non-asthmatic) than in human ASM cells treated with TNFα. Hence, PDGF was used as a mitogenic agent for further cell proliferation studies.

Figure 1. Effect of TNFα, IL-13 and PDGF on human ASM cell proliferation.

Significant mitogenic effect in asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells was observed with 24 h treatment of tumor necrosis factor alpha (20 ng/ml TNFα), Interleukin-13 (50 ng/ml IL-13) or Platelet Derived Growth Factor (2 ng/ml PDGF) by MTT (A) and CyQuant (B) assays. PDGF-induced proliferation was relatively higher compared to both the pro-inflammatory cytokine exposure. ###p<0.001, ##p<0.01, nsp>0.05 vs vehicle; ***p<0.001, **p<0.01 vs TNFα. Values are mean ± SEM from n of 4 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

3.2. Mitogenic effect of PDGF in human ASM cells

To determine an appropriate PDGF concentration for evaluating the effect of ERs on ASM cell proliferation, we first performed a dose-response curve (Figure 2A and 2B). The results showed that 2 ng/ml PGDF produced the maximum mitogenic effect in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM cells compared to vehicle treated controls. In fact, a progressive decrease in cell count was noted as PDGF concentration increased beyond 10 ng/ml. Furthermore, the mitogenic effect of PDGF was significantly higher in asthmatic human ASM compared to non-asthmatic human ASM at the same given dose.

Figure 2. Mitogenic effect of PDGF on human ASM cells.

Effect of different concentrations of PDGF on the rate of proliferation on human airway smooth muscle (ASM) cells was measured by MTT (A) and CyQuant (B) assays. At a dose of 2 ng/ml, maximum ASM proliferation at 24 h was observed, while further increases in concentrations of PDGF resulted in reduced proliferation. Notably, the rate of proliferation was greater in asthmatic ASM compared to non-asthmatic ASM. *Significant effect in Asthmatic cells vs. Non-asthmatic cells at the same given dose, (*p<0.05). Values are mean ± SEM from n of 4 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

3.3. Effect of ERα and ERβ agonists on human ASM proliferation

In the preliminary screening studies, the effect of different ERα (PPT and THC), ERβ (WAY, FERB-033 and DPN) agonists and GPR30 agonist (G1) on PDGF stimulated ASM cell proliferation were evaluated. ERβ agonists produced a significant blunting effect, higher than ERα agonists in all the patient samples (Figure 3A and 3B). The GPR30 selective agonist G1 did not show a significant inhibition of PDGF-induced proliferation of human ASM cells. Amongst ERβ agonists, WAY showed a significantly higher reduction in PDGF-induced proliferation under all experimental settings and decreased the cell count by ≃ 65% and ≃ 55% in asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM respectively.

Figure 3. Effect of ERα, ERβ and GPR30 agonists on human ASM proliferation.

The effect of ERα agonists (PPT and THC), ERβ agonists (WAY-200070, FERB033 and DPN) GPR30/GPER agonist (G1) on PDGF-induced cell proliferation of asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM cells was evaluated using (A) MTT and (B) CyQuant NF assays. ERβ agonist WAY showed the more pronounced inhibition of PDGF-induced proliferation in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic samples. ERα and GPR30 agonists did not show any consistent blunting of PDGF-induced proliferation of human ASM as compared to ERβ agonists. ###p<0.05 vs vehicle, ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, nsp>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Values are means ± SEM from n of 5 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

3.4. ERβ agonist blunts PDGF-induced proliferation in human ASM

To further evaluate the role of differential ER signaling in ASM proliferation, the effect of estradiol (E2) and selective ER agonists in the absence and presence of PDGF was studied. Treatment with WAY alone for 24 h reduced asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM proliferation significantly compared to the vehicle. Furthermore, cells pre-treated with WAY significantly blunted the proliferative effect of PDGF (reduced by 67.8% and 61.2% in asthmatic ASM and 48.6% and 50.3% in non-asthmatic ASM cells using MTT and CyQuant NF assays respectively compared to the vehicle group (Figure 4A, 4B). E2 and PPT alone showed no significant effect on cell proliferation compared to vehicle. Pre-treatment with E2 and PPT in asthmatic ASM cells showed comparable effects but they did not show significant inhibition or had lesser inhibition of PDGF-induced non-asthmatic ASM cell proliferation as compared to with ERβ agonist WAY (Figure 4A, 4B).

Figure 4. ERβ agonist blunts PDGF induced proliferation in human ASM.

ERβ agonist (WAY) significantly blunted the mitogenic effect of PDGF as evaluated using (A) MTT and (B) CyQuant NF assays. The inhibitory effect of PPT on PDGF-induced ASM proliferation was substantially less compared to WAY or non-significant in non-asthmatic patients. E2 did not show significant decrease in PDGF-induced proliferation in most settings. ###P<0.001, ##P<0.01, #P<0.05, nsP>0.05 vs vehicle; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01 nsP>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Values are means ± SEM from n of 6 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

3.5 Effect of ER siRNA on human ASM Proliferation

To confirm the observed effects and the estrogen receptor mediated mechanisms, experiments were performed with cells transfected with ER selective siRNA. Treatment with PDGF, WAY and WAY+PDGF significantly increased the proliferation of asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM cells transfected with ERβ siRNA (Figure 5A) as compared to negative siRNA transfected cells. In siRNA mediated ERβ receptor knockdown of human ASM, pretreatment with WAY (Figure 5A) has a minimal decrease of the PDGF-induced proliferation but not to the extent observed in non-transfected cells (as compared to Figure 4). This confirms that the inhibitory effect of ERβ agonist WAY is through ERβ receptor mediated function. Moreover, the basal proliferation in ERβ siRNA transfected cells was significantly higher compared to negative siRNA group (Figure 5A). Interestingly, this basal effect was absent in ERα siRNA transfected asthmatic ASM cells (Figure 5B). Treatment with PPT in ERα siRNA transfected non-asthmatic ASM did not show any significant change in proliferation as compared to negative siRNA treated group. The effectiveness of the siRNA transfection was assessed by performing western blot analysis for ERβ and ERα expression in human ASM cells. siRNA transfection was found to be effective as evident with the significantly decreased ERβ (Figure 5C) and ERα (Figure 5D) protein expression in the transfected cells as compared to negative siRNA group.

Figure 5. Effect of ER siRNA on human ASM proliferation and ER Protein Expression.

MTT assay was used to study the effect of ERβ agonist WAY and ERα agonist PPT on PDGF-induced proliferation in Asthmatic and Non-Asthmatic human ASM cells transfected with ERβ siRNA (Figure 5A) and ERα siRNA (Figure 5B) respectively. There was significant mitogenic effect observed in ERβ siRNA transfected cells compared to negative siRNA in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells. ERβ siRNA transfected human ASM cells treated with WAY and WAY+PDGF produced a significant increase in proliferation as compared to negative siRNA treated group. PPT+PDGF treatment produced an increased proliferation in ERα siRNA transfected human ASM cells. Western blot analysis was performed to determine the transfection efficacy of ERβ (Figure 5C) and ERα (Figure 5D) receptor siRNA in human ASM cells. Values are means ± SEM from n of 5 samples from asthmatics and n of 6 samples from non-asthmatics for MTT assay. Values are means ± SEM from n of 3 different patient samples of asthmatics and non-asthmatics for western analysis. ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, nsp>0.05 vs negative siRNA.

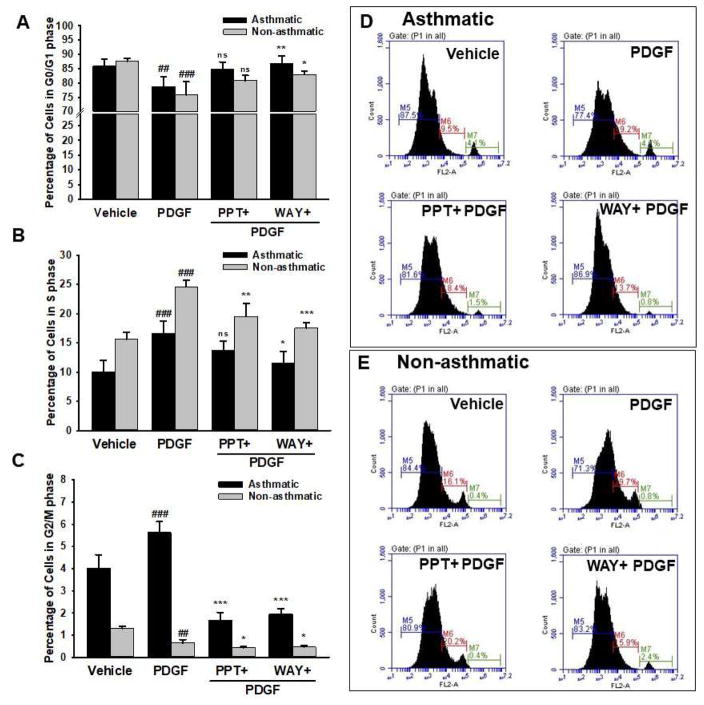

3.6. ERβ agonist induces G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest

There was a significant 7% increase in ‘S’ phase (Figure 6B) and a reciprocal decrease of cells in ‘G0-G1’ phase (Figure 6A) among the PDGF-treated groups in asthmatic ASM compared to vehicle, indicating an increased proliferation (Figure 6C). This mitogenic effect of PDGF was inhibited by WAY as evidenced by a significant 5% decrease in ‘S’ phase. We found significant increase in the G0/G1 phase among asthmatic cells pre-treated with WAY (Figure 6B). Whereas, there was no significant effect observed with pre-treatment with PPT on the G0/G1 phase or ‘S’ phase of the asthmatic cells. Similarly, a significant 10% increase in ‘S’ phase cell population was observed in PDGF-treated non-asthmatic cells, which was blunted by pre-treatment with WAY (Figure 6B). Consistent with the findings above, flow cytometric analysis of asthmatic ASM cells stimulated with PDGF showed a substantial increase in the percentage of cells entering G2/M phase indicating proliferation, while cells pre-treated with WAY and PPT showed significantly decreased cells in G2/M phase (Figure 6C). This effect of WAY and PPT on G2/M phase was less significant in non-asthmatic ASM.

Figure 6. Effect of ER agonists on different phases of human ASM cell cycles studied using flow cytometry.

Cell cycle analysis showed increased cell population in S and M phases (B and C) with PDGF treatment. Asthmatic ASM showed an increased ratio of cells in S (B) and G2/M phase (C) to G0/G1 phase (A), consistent with a proliferative tendency of asthmatic ASM. ERβ agonist WAY significantly reduced the ratio of asthmatic human ASM cells in S to G0/G1 phase (B to A) and G2/M to G0/G1 phase (C to A) suggesting arrest of cell cycle progression in G0/G1 phase, and thus inhibiting proliferation. The representative profiles of asthmatic (D) and non-asthmatic (E) human ASM cell-cycle distributions by various treatment groups is shown where M5, M6 and M7 represent percentage of cells in G0/G1, S and G2/M phase respectively. ###p<0.001, ##p<0.01 vs vehicle; ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, *p<0.05, nsp>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Values are means ± SEM from n of 3 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

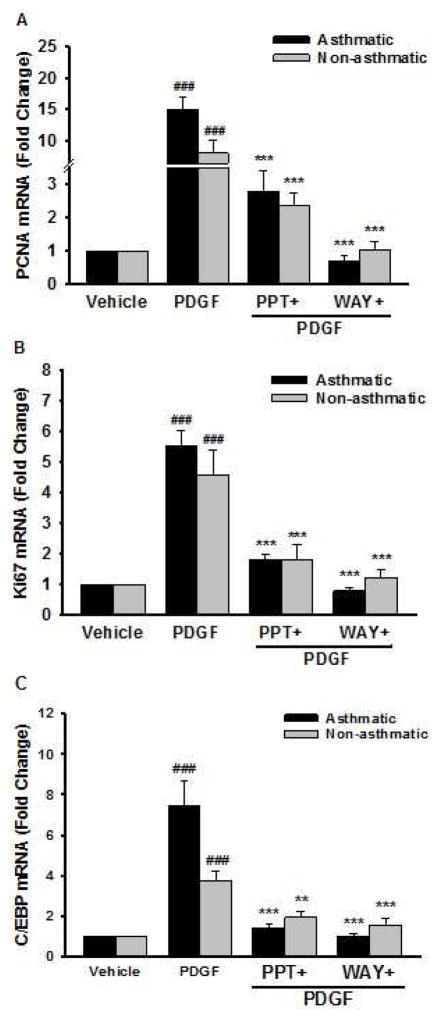

3.7. Expression of PDGF induced proliferative markers in human ASM

PDGF alone significantly increased mRNA expression of PCNA, Ki67 and C/EBP (Figure 7A–C) compared to vehicle. Cells pre-treated with WAY and PPT showed significant decrease in PDGF-induced mRNA expression of PCNA, Ki67 and C/EBP. This mRNA expression of the proliferative marker genes was significantly reduced by pre-treatment with WAY and PPT (Figure 7A–C). The effect of PPT was comparable to that of WAY in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM.

Figure 7. PCNA, Ki67 and C/EBP gene expression in human ASM.

Cells were treated with vehicle, ERα agonist (PPT) or ERβ agonist (WAY) for 2 h, followed by PDGF for 24 h. (A) PCNA, (B) Ki67, and (C) C/EBP mRNA expression were measured by real time qPCR. PDGF treated group showed a significant increase in PCNA, Ki67, and C/EBP expression; whereas pre-treatment with PPT and WAY significantly decreased the expression of these genes. ###p<0.001 vs vehicle and ***p<0.001, **p<0.01 vs PDGF treated group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, from n of 6 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

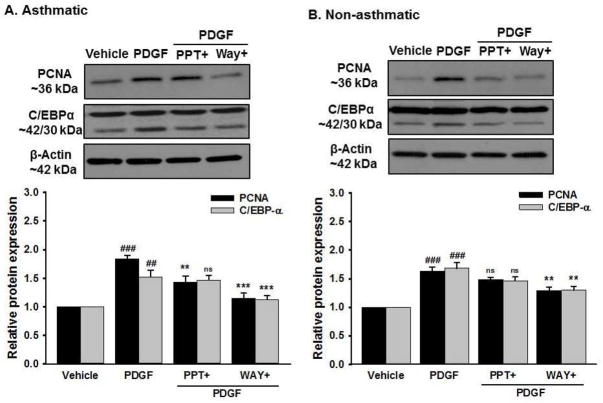

Consistent with the mRNA data, there was increased expression of proliferative proteins PCNA, C/EBPα (Figure 8), Cyclin-D1 and Cyclin-E (Figure 9) in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells stimulated with PDGF compared to vehicle. Interestingly, this PDGF-induced increase in expression of all the mentioned proteins were significantly inhibited in cells pre-treated with WAY whereas PPT did not have any significant effect on them.

Figure 8. Effect of ER agonists on PDGF induced proliferative marker proteins in human ASM.

Western analysis of proliferative protein markers. (A) Asthmatic human ASM showed increased protein expression of PCNA and C/EBP-α following PDGF exposure; an effect substantially blunted by WAY but not by PPT. (B) Similarly, non-asthmatic human ASM shows decreased PDGF induced PCNA and C/EBP expression in cells pre-treated with WAY but PPT had no effect on the same. β-Actin served as a loading control ###p<0.001, ##p<0.01 vs vehicle and ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, nsp>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, from n of 5 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

Figure 9. Effect of ER agonists on PDGF induced cell cycle progression proteins in human ASM.

(A) Asthmatic and (B) Non-asthmatic human ASM showed increased expression of Cyclin-D1 and Cyclin E with PDGF exposure. WAY significantly decreased PDGF induced Cyclin-D1 and Cyclin-E protein expression in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM. Pre-treatment with PPT did not show any significant effect on the expression of these proteins. β-Actin served as a loading control. ###P<0.001, ##P<0.01 vs vehicle; ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, nsP>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, from n of 6 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

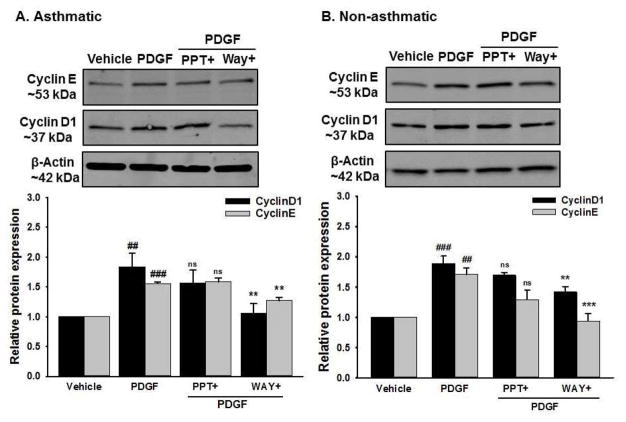

3.8. ERβ agonist inhibits cell signaling pathways

To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which WAY inhibits PDGF stimulated ASM proliferation, we explored changes in MAPK, ERK1/2 and Akt phosphorylation (Figure 10A and 10B). Preliminary experiments were carried out using protein lysates collected at different time points following PDGF treatment. 6h of PDGF exposure was identified to result in maximum activation of cell signaling proteins and hence used for further studies (data not shown with 12 h and 24 h treatment). Cells pre-treated with WAY significantly decreased PDGF-induced phosphorylation of p38, ERK and Akt in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM cells. Cells pre-treated with PPT showed a significant decrease in PDGF-induced phosphorylation of only p38 in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic cells (Figure 10A and 10B).

Figure 10. Effect of ER agonists on MAPK expression in PDGF induced human ASM cells.

Western analysis shows PDGF induced activation of p38, ERK and Akt in (A) Asthmatic and (B) Non-asthmatic human ASM. Pre-treatment with WAY significantly reduced this PDGF-induced phosphorylation of p38, ERK and Akt in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM. Pre-treatment with PPT significantly decreased only p38 activation in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic human ASM and the effect is significantly lesser when compared to WAY. ###p<0.001, ##p<0.01, #p<0.05 vs vehicle; ***p<0.001, **p<0.01, nsp>0.05 vs PDGF treated group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, from n of 6 samples each from asthmatics and non-asthmatics.

4. Discussion

Asthma is a chronic disorder characterized by airway obstruction induced by hyperreactivity and remodeling promoted by inflammation (Prakash, 2016, Puthalapattu and Ioachimescu, 2014). Clinical data showing sex differences and potential sex steroid effects in asthma underline the importance of understanding the mechanisms by which sex steroids such as estrogens influence the airway. Here, given that ASM cell proliferation and migration play a crucial role in airway remodeling (Sathish et al., 2013, Yang et al., 2015, Lahm et al., 2012), the present study sought to explore the mechanisms by which estrogens modulate ASM proliferation. We demonstrate that there are differential effects of ER isoforms where ERβ may interestingly serve to blunt cell proliferation, particularly in asthmatic ASM, thus pointing to the importance of understanding the specific roles of ER isoforms in the context of estrogenic effects in asthmatic airways.

Beyond its well-recognized roles in the reproductive system, recent studies have identified other roles for estrogen in different organs and tissues of both males and females, including cell growth and differentiation (Sathish et al., 2015, Townsend et al., 2012, Townsend et al., 2012). In this regard, various epidemiological and pre-clinical data have shown sex differences in asthma, and the potential effects of estrogens on airway function (Townsend et al., 2012, Sathish and Prakash, 2016), resulting in increased interest in exploring sex steroid receptor expression and function in airways. Our previous studies demonstrated that physiological concentrations of estrogen can induce bronchodilation by enhancing cAMP and protein kinase A and thus decreasing [Ca2+]i levels in ASM (Townsend et al., 2010, Townsend et al., 2012). We and others have demonstrated the expression of both ERα and ERβ in human ASM (Townsend et al., 2012, Aravamudan et al., 2017, Hughes et al., 2002, Dahlman-Wright et al., 2006, Jia et al., 2011). Most recently, we evaluated the differential expression of ERα and ERβ in asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM, and found that ERβ expression is significantly greater in asthmatic ASM in both males and females (Aravamudan et al., 2017) suggesting the potential importance of ER isoforms in asthma pathophysiology or its alleviation. The results of the present study support this concept showing the differential effect of ER isoforms in the context of ASM proliferation.

The present study is the first to demonstrate ER isoform specific effects in human ASM proliferation in response to a mitogen. Some previous animal studies suggest estrogens enhance inflammation and have a mitogenic effect on ASM (Stamatiou et al., 2011, Sakazaki, Ueno and Nakamuro, 2008, Riffo-Vasquez et al., 2007), while other studies find that estrogens blunt asthma symptoms (Gilliver, 2010, Lieberman et al., 1995, Myers and Sherman, 1994) and thus likely have blunting effects on proliferation. However, most studies utilized 10% serum medium as mitogenic agent and have not explored the role of ER isoforms. In this study, we demonstrated that ERβ activation significantly suppressed PDGF-stimulated human ASM cell proliferation and arrested cell cycle progression in G0/G1 phase.

The mitogenic effect of PDGF in human ASM cells has been previously reported (Pelaia et al., 2008), and PDGF effects in proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells is well-known (Li et al., 2016, Dong et al., 2010, Guan et al., 2014). PDGF interacts with PDGF receptor (PDGFR) on cell membrane inducing dimerization, which is essential for activation of tyrosine kinase receptors (Dong et al., 2010, Heldin and Östman, 1996). PDGFR activates intracellular signaling pathways such as Ras/Rac, MAPK, PI3K, STAT and Src, which modify cellular function and enhance cell proliferation and migration (Heldin and Westermark, 1999, Rönnstrand and Heldin, 2001). In the present study, we found that PDGF does activate multiple signaling intermediates particularly in asthmatic ASM cells.

The selection of estrogen receptor selective agonists was based on critical literature review of studies performed on ER’s in the past decade. WAY200070 is a selective estrogen receptor beta agonist (IC50 2.3 nM for ERβ and 155 nM for ERα) (Harris, 2007, Malamas et al., 2004) with 410 times more selectivity to ERβ over ERα (Stauffer et al., 2000). In a murine study, WAY200070 at a dose of 30 mg/kg has induced translocation of ERs’ to the nucleus in wild type and ERα KO mice while no translocation was observed in ERβ KO mice (Hughes et al., 2008) indicating the mechanism of action of WAY200070 through ERβ and not ERα. Moreover, WAY200070 has an inverted U shaped dose response curve due to high dose binding to ERα as well as ERβ (Clipperton et al., 2008). Furthermore, ERα and ERβ act in opposite to each other (Gustafsson, 2006) and binding of WAY200070 to ERα may counter the effects of ERβ. In this study, we used WAY200070 at 10 nM dose, which is potent enough to activate ERβ but not ERα considering the IC50 values. PPT was selected as ERα selective agonist as it is completely inactive in stimulating transcription of ERs’ through ERβ (Stauffer et al., 2000). In concurrence to this, our biochemical data representing mechanism of action from the current study also indicates differential signaling of ER’s.

Recent study questioned about the expression of ERβ receptor in the peripheral tissues including the lung and suggested the verified antibody for ERβ detection (Andersson et al., 2017). In light of this, we conducted the additional experiments on freshly isolated human ASM tissue bundles which were denuded of epithelium by mild abrasions and confirmed the expression of ERβ protein by western analysis using verified ERβ antibody (not shown) (Andersson et al., 2017). Our study showed that the ERβ selective agonist WAY has a more prominent effect in blunting ASM proliferation supporting our hypothesis regarding differential ER isoform effects. Furthermore, siRNA studies confirmed the crucial role of ERβ in PDGF induced human ASM proliferation albeit only moderate siRNA transfection efficiency observed. In siRNA mediated knock down of ERβ receptor, WAY did not reduce PDGF induced human ASM proliferation indicating that WAY act through ERβ receptor in regulating proliferation. We did not observe any significant effect of GPR30/GPER agonist G1 on PDGF induced human ASM proliferation. Most of the reported studies primarily implicate non-genomic activations of GPR30/GPER rather than genomic (Pupo, Maggiolini and Musti, 2016, Feldman and Limbird, 2017, Filardo et al., 2006) which aligns with our observed data.

However, we did not observe any significant effect of ERα activation alone in human ASM cell cycle phases, ERβ activation downregulated G2/M phase activated by PDGF in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells and arrested the cell cycle in G0/G1, consequently leading to inhibited proliferation. G0/G1 phase represents quiescent state, whereas S is synthesis phase, where DNA replication occurs and G2/M phase in which cell division take place (Di Sante et al., 2017, Casimiro et al., 2014). Cyclin-D1 is closely associated with cell-cycle transition through G1 phase and commitment to enter S phase (Casimiro et al., 2014, Xiong et al., 1997). Earlier studies have shown that cyclin-D1 is responsible for shortening G1 and is rate limiting in G1 phase progression (Jiang et al., 1993, Quelle et al., 1993, Resnitzky et al., 1994). Regulation of cyclin-D1 expression in ASM cells is controlled by catalytic activation of ERKs (Ramakrishnan et al., 1998). Cyclin-E is an important protein responsible for activation of cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) to sustain the hyperphosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (Rb) which is responsible for transcription of S phase (Nevins, 1998, Pavletich, 1999). ERβ activation of human ASM cells significantly blunted PDGF-induced protein expression of cyclin-D1 and cyclin-E in asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM, which is further supported by our flow cytometry analysis indicating the potential role of ERβ signaling in ASM proliferation, and the involvement of ERKs.

The role of PCNA, Ki-67 and C/EBPs in cell proliferation and differentiation are well known (Ruffell et al., 2009, Wylam et al., 2015). PDGF receptor activation initiates an intracellular cascade leading to an increase in gene expression of these proliferative markers. PDGF effects on these markers was suppressed by ERβ activation again supporting the role for ERβ per se in modulating proliferation. The importance of MAPK pathways in proliferation and migration of human ASM cells has been established (Zhai et al., 2004), including ERK 1/2 JNK and p38 MAPK (Gerthoffer and Singer, 2003). Consistent with reported data we observed increased phosphorylation of ERK 1/2, and p38 MAPK upon PDGF exposure. These signaling pathways were inhibited by ERβ activation, particularly in asthmatic ASM. These effects of ERβ are consistent with data from mammary epithelium and breast cancer cells (Cotrim et al., 2013, Helguero et al., 2005, Helguero et al., 2008).

Activation of PDGFR upregulates PI3K/Akt signaling and directs the phosphorylation of p70S6 kinase, a primary mTOR substrate responsible for ASM cell proliferation (Garat et al., 2006). Inhibition of PI3K signaling has a significant role in repressing PDGF-induced ASM cell proliferation. Our data show significant decrease in phosphorylation of Akt with ERβ activation, indicating the distinctive role of ERβ in modulating ASM proliferative pathways.

Overall, the present study shows that PDGF upregulates a variety of mechanisms to contribute in ASM cell proliferation in the context of airway remodeling. ERβ activation significantly inhibits PDGF-induced cell proliferation in non-asthmatic and asthmatic ASM cells by suppressing proliferative proteins along with MAPKs and PI3K signaling pathway. These findings further broaden the role of ER regulation in asthma pathophysiology and point to a potentially niche role for ERβ receptor to be a novel target for airway remodeling.

Highlights.

PDGF significantly increased human airway smooth muscle (ASM) proliferation in non-asthmatic and asthmatic cells.

We show that receptor specific ERβ signaling in regulate the PDGF induced human ASM proliferation.

ERβ activation regulates cell cycle-related antigens (PCNA and Ki67) and C/EBP.

PDGF induced MAPKs and PI3K signaling pathway inhibited by activation of ERβ signaling.

Divergent ERβ activation downregulated G2/M phase activated by PDGF in both asthmatic and non-asthmatic ASM cells and arrested the cell cycle in G0/G1.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grants R01 HL123494, R01 HL123494-02S1 (Venkatachalem), and R01 HL 088029 (Prakash). Additional support in part from ND EPSCoR with NSF #1355466 and NDSU RCA Activity. Authors would like to thank Dr. Jagadish Loganathan, Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, NDSU for providing technical support in completion of this study. The authors also acknowledge Dr. Tao Wang, Core Biology Facility for helping in performing the flow cytometry study. Funding for the Core Biology Facility used in the publication was made possible by NIH Grant P30 GM103332-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prakash Y. Emerging concepts in smooth muscle contributions to airway structure and function: implications for health and disease. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2016;311:L1113–L1140. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00370.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prakash Y, Martin RJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the airways. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2014;143:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prakash Y. Airway smooth muscle in airway reactivity and remodeling: what have we learned? American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2013;305:L912–L933. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00259.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazaar AL, Panettieri RA., Jr Airway smooth muscle: a modulator of airway remodeling in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:488–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.06.030. quiz 496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sathish V, Abcejo AJ, VanOosten SK, Thompson MA, Prakash Y, Pabelick CM. Caveolin-1 in cytokine-induced enhancement of intracellular Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2011;301:L607–L614. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dekkers BG, Maarsingh H, Meurs H, Gosens R. Airway structural components drive airway smooth muscle remodeling in asthma. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009;6:683–692. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-056DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang SY, Freeman MR, Sathish V, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash Y. Sex Steroids Influence Brain-Derived Neurotropic Factor Secretion From Human Airway Smooth Muscle Cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 2016;231:1586–1592. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rydell-Törmänen K, Andréasson K, Hesselstrand R, Risteli J, Heinegård D, Saxne T, Westergren-Thorsson G. Extracellular matrix alterations and acute inflammation; developing in parallel during early induction of pulmonary fibrosis. Laboratory Investigation. 2012;92:917–925. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerthoffer WT. Migration of airway smooth muscle cells. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008;5:97–105. doi: 10.1513/pats.200704-051VS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershenson MB, Brown M, Camoretti-Mercado B, Solway J. Airway smooth muscle in asthma. Annu Rev pathmechdis Mech Dis. 2008;3:523–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.1.110304.100213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koziol-White CJ, Damera G, Panettieri RA. Targeting airway smooth muscle in airways diseases: an old concept with new twists. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2011;5:767–777. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roscioni SS, Dekkers BG, Prins AG, Oldenbeuving G, Pool KM, Elzinga CR, Meurs H, Schmidt M. Epac And PKA Inhibit PDGF-induced airway smooth muscle phenotype modulation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010:A2142. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coraux C, Roux J, Jolly T, Birembaut P. Epithelial cell–extracellular matrix interactions and stem cells in airway epithelial regeneration. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008;5:689–694. doi: 10.1513/pats.200801-010AW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bossé Y, Sobieszek A, Pare PD, Seow CY. Length adaptation of airway smooth muscle. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008;5:62–67. doi: 10.1513/pats.200705-056VS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman MR, Sathish V, Manlove L, Wang S, Britt RD, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and airway fibrosis in asthma. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2017;313:L360–L370. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00580.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Royce SG, Cheng V, Samuel CS, Tang ML. The regulation of fibrosis in airway remodeling in asthma. Molecular and cellular endocrinology. 2012;351:167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lagente V, Boichot E. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in the inflammatory process of respiratory diseases. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;48:440–444. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suganuma N, Ito S, Aso H, Kondo M, Sato M, Sokabe M, Hasegawa Y. STIM1 regulates platelet-derived growth factor-induced migration and Ca2+ influx in human airway smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlin SM, Roth M, Black JL. Urokinase potentiates PDGF-induced chemotaxis of human airway smooth muscle cells. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2003;284:L1020–L1026. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00092.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirst SJ, Barnes PJ, Twort CH. Quantifying proliferation of cultured human and rabbit airway smooth muscle cells in response to serum and platelet-derived growth factor. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1992;7:574–574. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/7.6.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ingram JL, Bonner JC. EGF and PDGF receptor tyrosine kinases as therapeutic targets for chronic lung diseases. Current molecular medicine. 2006;6:409–421. doi: 10.2174/156652406777435426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joubert P, Hamid Q. Role of airway smooth muscle in airway remodeling. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:713–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.James AL, Maxwell PS, Pearce-Pinto G, Elliot JG, Carroll NG. The relationship of reticular basement membrane thickness to airway wall remodeling in asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2002;166:1590–1595. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2108069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sathish V, Martin YN, Prakash Y. Sex steroid signaling: Implications for lung diseases. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2015;150:94–108. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonds RS, Midoro-Horiuti T. Estrogen effects in allergy and asthma. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;13:92. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835a6dd6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bjornson CL, Mitchell I. Gender differences in asthma in childhood and adolescence. J Gend Specif Med. 2000;3:57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caracta CF. Gender differences in pulmonary disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2003;70:215–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carey MA, Card JW, Voltz JW, Arbes SJ, Jr, Germolec DR, Korach KS, Zeldin DC. It’s all about sex: gender, lung development and lung disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18:308–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Marco R, Locatelli F, Sunyer J, Burney P. Differences in incidence of reported asthma related to age in men and women: a retrospective analysis of the data of the European Respiratory Health Survey. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2000;162:68–74. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9907008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melgert BN, Ray A, Hylkema MN, Timens W, Postma DS. Are there reasons why adult asthma is more common in females? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2007;7:143–50. doi: 10.1007/s11882-007-0012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsend EA, Miller VM, Prakash Y. Sex differences and sex steroids in lung health and disease. Endocrine reviews. 2012;33:1–47. doi: 10.1210/er.2010-0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laudet V, Gronemeyer H. The Nuclear Receptors Factbooks Academic. San Diego: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Townsend EA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Rapid effects of estrogen on intracellular Ca2+ regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L521–30. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00287.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Townsend EA, Sathish V, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Estrogen effects on human airway smooth muscle involve cAMP and protein kinase A. American journal of physiology. Lung cellular and molecular physiology. 2012;303:L923–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00023.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prossnitz ER, Arterburn JB, Smith HO, Oprea TI, Sklar LA, Hathaway HJ. Estrogen signaling through the transmembrane G protein–coupled receptor GPR30. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:165–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marino M, Galluzzo P, Ascenzi P. Estrogen signaling multiple pathways to impact gene transcription. Current genomics. 2006;7:497–508. doi: 10.2174/138920206779315737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aravamudan B, Goorhouse KJ, Unnikrishnan G, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Hawse JR, Prakash Y, Sathish V. Differential Expression of Estrogen Receptor Variants in Response to Inflammation Signals in Human Airway Smooth Muscle. Journal of cellular physiology. 2017;232:1754–1760. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stamatiou R, Paraskeva E, Papagianni M, Molyvdas PA, Hatziefthimiou A. The mitogenic effect of testosterone and 17beta-estradiol on airway smooth muscle cells. Steroids. 2011;76:400–8. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng B, Song J, Zou Y, Wang Q, Lei Y, Zhu C, Hu C. Responses of vascular smooth muscle cells to estrogen are dependent on balance between ERK and p38 MAPK pathway activities. International journal of cardiology. 2009;134:356–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Muka T, Vargas KG, Jaspers L, Wen K-x, Dhana K, Vitezova A, Nano J, Brahimaj A, Colpani V, Bano A. Estrogen receptor β actions in the female cardiovascular system: A systematic review of animal and human studies. Maturitas. 2016;86:28–43. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li Q, Zhu L, Zhang L, Chen H, Zhu Y, Du Y, Zhong W, Zhong M, Shi X. Inhibition of estrogen related receptor α attenuates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration by regulating RhoA/p27 Kip1 and β-Catenin/Wnt4 signaling pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2017;799:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2017.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Cheng Y, Simoncini T, Xu S. 17β-Estradiol inhibits TNF-α-induced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via suppression of TRAIL. Gynecological Endocrinology. 2016;32:581–586. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2016.1141882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abcejo AJ, Sathish V, Smelter DF, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Hartman WR, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor enhances calcium regulatory mechanisms in human airway smooth muscle. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vohra PK, Thompson MA, Sathish V, Kiel A, Jerde C, Pabelick CM, Singh BB, Prakash Y. TRPC3 regulates release of brain-derived neurotrophic factor from human airway smooth muscle. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2013;1833:2953–2960. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sathish V, Freeman MR, Long E, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash Y. Cigarette smoke and estrogen signaling in human airway smooth muscle. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry. 2015;36:1101–1115. doi: 10.1159/000430282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aravamudan B, Thompson M, Pabelick C, Prakash Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces proliferation of human airway smooth muscle cells. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine. 2012;16:812–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01356.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu WN, Leung KN. Jacaric acid inhibits the growth of murine macrophage-like leukemia PU5-1.8 cells by inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Cancer cell international. 2015;15:90. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0246-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Puthalapattu S, Ioachimescu OC. Asthma and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2014;62:665–675. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sathish V, Vanoosten SK, Miller BS, Aravamudan B, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Vassallo R, Prakash YS. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cigarette smoke-induced airway hyperreactivity. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48:431–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0129OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang G, Li J-Q, Bo J-P, Wang B, Tian X-R, Liu T-Z, Liu Z-L. Baicalin inhibits PDGF-induced proliferation and migration of airway smooth muscle cells. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015;8:20532. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lahm T, Albrecht M, Fisher AJ, Selej M, Patel NG, Brown JA, Justice MJ, Brown MB, Van Demark M, Trulock KM. 17β-Estradiol attenuates hypoxic pulmonary hypertension via estrogen receptor–mediated effects. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012;185:965–980. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201107-1293OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sathish V, Prakash Y. Sex Differences in Pulmonary Anatomy and Physiology: Implications for Health and Disease, Sex Differences in Physiology. Elsevier; 2016. pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hughes RA, Harris T, Altmann E, McAllister D, Vlahos R, Robertson A, Cushman M, Wang Z, Stewart AG. 2-Methoxyestradiol and analogs as novel antiproliferative agents: analysis of three-dimensional quantitative structure-activity relationships for DNA synthesis inhibition and estrogen receptor binding. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1053–69. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dahlman-Wright K, Cavailles V, Fuqua SA, Jordan VC, Katzenellenbogen JA, Korach KS, Maggi A, Muramatsu M, Parker MG, Gustafsson J-Å. International union of pharmacology. LXIV. Estrogen receptors. Pharmacological reviews. 2006;58:773–781. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jia S, Zhang X, He DZ, Segal M, Berro A, Gerson T, Wang Z, Casale TB. Expression and Function of a Novel Variant of Estrogen Receptor–α36 in Murine Airways. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2011;45:1084–1089. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0268OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sakazaki F, Ueno H, Nakamuro K. 17beta-Estradiol enhances expression of inflammatory cytokines and inducible nitric oxide synthase in mouse contact hypersensitivity. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:654–60. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riffo-Vasquez Y, Ligeiro de Oliveira AP, Page CP, Spina D, Tavares-de-Lima W. Role of sex hormones in allergic inflammation in mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37:459–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gilliver SC. Sex steroids as inflammatory regulators. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;120:105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lieberman D, Kopernic G, Porath A, Levitas E, Lazer S, Heimer D. Influence of estrogen replacement therapy on airway reactivity. Respiration. 1995;62:205–8. doi: 10.1159/000196448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Myers JR, Sherman CB. Should supplemental estrogens be used as steroid-sparing agents in asthmatic women? Chest. 1994;106:318–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.1.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pelaia G, Renda T, Gallelli L, Vatrella A, Busceti MT, Agati S, Caputi M, Cazzola M, Maselli R, Marsico SA. Molecular mechanisms underlying airway smooth muscle contraction and proliferation: implications for asthma. Respiratory medicine. 2008;102:1173–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dong L-H, Wen J-K, Miao S-B, Jia Z, Hu H-J, Sun R-H, Wu Y, Han M. Baicalin inhibits PDGF-BB-stimulated vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through suppressing PDGFRβ-ERK signaling and increase in p27 accumulation and prevents injury-induced neointimal hyperplasia. Cell research. 2010;20:1252–1262. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guan S, Tang Q, Liu W, Zhu R, Li B. Nobiletin Inhibits PDGF-BB-Induced Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation and Migration and Attenuates Neointimal Hyperplasia in a Rat Carotid Artery Injury Model. Drug development research. 2014;75:489–496. doi: 10.1002/ddr.21230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heldin C-H, Östman A. Ligand-induced dimerization of growth factor receptors: variations on the theme. Cytokine & growth factor reviews. 1996;7:3–10. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heldin C-H, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiological reviews. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rönnstrand L, Heldin CH. Mechanisms of platelet-derived growth factor–induced chemotaxis. International journal of cancer. 2001;91:757–762. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1136>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Harris HA. Estrogen receptor-β: recent lessons from in vivo studies. Molecular endocrinology. 2007;21:1–13. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Malamas MS, Manas ES, McDevitt RE, Gunawan I, Xu ZB, Collini MD, Miller CP, Dinh T, Henderson RA, Keith JC. Design and synthesis of aryl diphenolic azoles as potent and selective estrogen receptor-β ligands. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2004;47:5021–5040. doi: 10.1021/jm049719y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Stauffer SR, Coletta CJ, Tedesco R, Nishiguchi G, Carlson K, Sun J, Katzenellenbogen BS, Katzenellenbogen JA. Pyrazole ligands: structure- affinity/activity relationships and estrogen receptor-α-selective agonists. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2000;43:4934–4947. doi: 10.1021/jm000170m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hughes ZA, Liu F, Platt BJ, Dwyer JM, Pulicicchio CM, Zhang G, Schechter LE, Rosenzweig-Lipson S, Day M. WAY-200070, a selective agonist of estrogen receptor beta as a potential novel anxiolytic/antidepressant agent. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:1136–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Clipperton AE, Spinato JM, Chernets C, Pfaff DW, Choleris E. Differential effects of estrogen receptor alpha and beta specific agonists on social learning of food preferences in female mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2362. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gustafsson J. ERβ scientific visions translate to clinical uses. Climacteric. 2006;9:156–160. doi: 10.1080/14689360600734328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Andersson S, Sundberg M, Pristovsek N, Ibrahim A, Jonsson P, Katona B, Clausson C-M, Zieba A, Ramström M, Söderberg O. Insufficient antibody validation challenges oestrogen receptor beta research. Nature communications. 2017;8:15840. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pupo M, Maggiolini M, Musti AM. GPER mediates non-genomic effects of estrogen, Estrogen Receptors. Springer; 2016. pp. 471–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feldman RD, Limbird LE. GPER (GPR30): a nongenomic receptor (GPCR) for steroid hormones with implications for cardiovascular disease and cancer. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2017;57:567–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010716-104651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Filardo EJ, Graeber CT, Quinn JA, Resnick MB, Giri D, DeLellis RA, Steinhoff MM, Sabo E. Distribution of GPR30, a seven membrane–spanning estrogen receptor, in primary breast cancer and its association with clinicopathologic determinants of tumor progression. Clinical cancer research. 2006;12:6359–6366. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Di Sante G, Di Rocco A, Pupo C, Casimiro MC, Pestell RG. Hormone-induced DNA damage response and repair mediated by cyclin D1 in breast and prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:81803. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Casimiro MC, Velasco-Velázquez M, Aguirre-Alvarado C, Pestell RG. Overview of cyclins D1 function in cancer and the CDK inhibitor landscape: past and present. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2014;23:295–304. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.867017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xiong W, Pestell RG, Watanabe G, Li J, Rosner MR, Hershenson MB. Cyclin D1 is required for S phase traversal in bovine tracheal myocytes. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 1997;272:L1205–L1210. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.6.L1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jiang W, Kahn S, Zhou P, Zhang Y, Cacace A, Infante A, Santella R, Weinstein I. Overexpression of cyclin D1 in rat fibroblasts causes abnormalities in growth control, cell cycle progression and gene expression. Oncogene. 1993;8:3447–3457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Quelle D, Ashmun R, Shurtleff S, Kato J, Bar-Sagi D, Roussel M, Sherr C. Overexpression of mouse D-type cyclins accelerates G1 phase in rodent fibroblasts. Genes & development. 1993;7:1559–1571. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Resnitzky D, Gossen M, Bujard H, Reed S. Acceleration of the G1/S phase transition by expression of cyclins D1 and E with an inducible system. Molecular and cellular biology. 1994;14:1669–1679. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Ramakrishnan M, Musa NL, Li J, Liu PT, Pestell RG, Hershenson MB. Catalytic activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases induces cyclin D1 expression in primary tracheal myocytes. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 1998;18:736–740. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.6.3152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nevins JR. Toward an understanding of the functional complexity of the E2F and retinoblastoma families. Cell growth and differentiation. 1998;9:585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pavletich NP. Mechanisms of cyclin-dependent kinase regulation: structures of cdks, their cyclin activators, and cip and INK4 inhibitors 1, 2. Journal of molecular biology. 1999;287:821–828. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ruffell D, Mourkioti F, Gambardella A, Kirstetter P, Lopez RG, Rosenthal N, Nerlov C. A CREB-C/EBPβ cascade induces M2 macrophage-specific gene expression and promotes muscle injury repair. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:17475–17480. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908641106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wylam ME, Sathish V, VanOosten SK, Freeman M, Burkholder D, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Prakash Y. Mechanisms of cigarette smoke effects on human airway smooth muscle. PloS one. 2015;10:e0128778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhai W, Eynott PR, Oltmanns U, Leung SY, Chung KF. Mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways in IL-1β-dependent rat airway smooth muscle proliferation. British journal of pharmacology. 2004;143:1042–1049. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gerthoffer WT, Singer CA. MAPK regulation of gene expression in airway smooth muscle. Respiratory physiology & neurobiology. 2003;137:237–250. doi: 10.1016/s1569-9048(03)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cotrim C, Fabris V, Doria M, Lindberg K, Gustafsson J-Å, Amado F, Lanari C, Helguero L. Estrogen receptor beta growth-inhibitory effects are repressed through activation of MAPK and PI3K signalling in mammary epithelial and breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2013;32:2390–2402. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Helguero LA, Faulds MH, Gustafsson J-Å, Haldosen L-A. Estrogen receptors alfa (ERα) and beta (ERβ) differentially regulate proliferation and apoptosis of the normal murine mammary epithelial cell line HC11. Oncogene. 2005;24:6605–6616. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Helguero LA, Lindberg K, Gardmo C, Schwend T, Gustafsson JA, Haldosen LA. Different roles of estrogen receptors alpha and beta in the regulation of E-cadherin protein levels in a mouse mammary epithelial cell line. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8695–704. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Garat CV, Fankell D, Erickson PF, Reusch JE-B, Bauer NN, McMurtry IF, Klemm DJ. Platelet-derived growth factor BB induces nuclear export and proteasomal degradation of CREB via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:4934–4948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02477-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]