Abstract

Dehydrogenative annulation reactions are among the most straightforward and efficient approach for the preparation of cyclic structures. However, the applications of this strategy for the synthesis of saturated heterocycles have been rare. In addition, reported dehydrogenative bond-forming reactions commonly employ stoichiometric chemical oxidants, the use of which reduces the sustainability of the synthesis and brings safety and environmental issues. Herein, we report an organocatalyzed electrochemical dehydrogenative annulation reaction of alkenes with 1,2- and 1,3-diols for the synthesis of 1,4-dioxane and 1,4-dioxepane derivatives. The combination of electrochemistry and redox catalysis using an organic catalyst allows the electrosynthesis to proceed under transition metal- and oxidizing reagent-free conditions. In addition, the electrolytic method has a broad substrate scope and is compatible with many common functional groups, providing an efficient and straightforward access to functionalized 1,4-dioxane and 1,4-dioxepane products with diverse substitution patterns.

Dehydrogenative annulation is a valuable approach to heterocycles, however, stoichiometric oxidants are often required. Here, the authors describe the electrochemical dehydrogenative annulation of diols and alkenes to generate dioxanes and dioxepanes under metal- and oxidant-free conditions.

Introduction

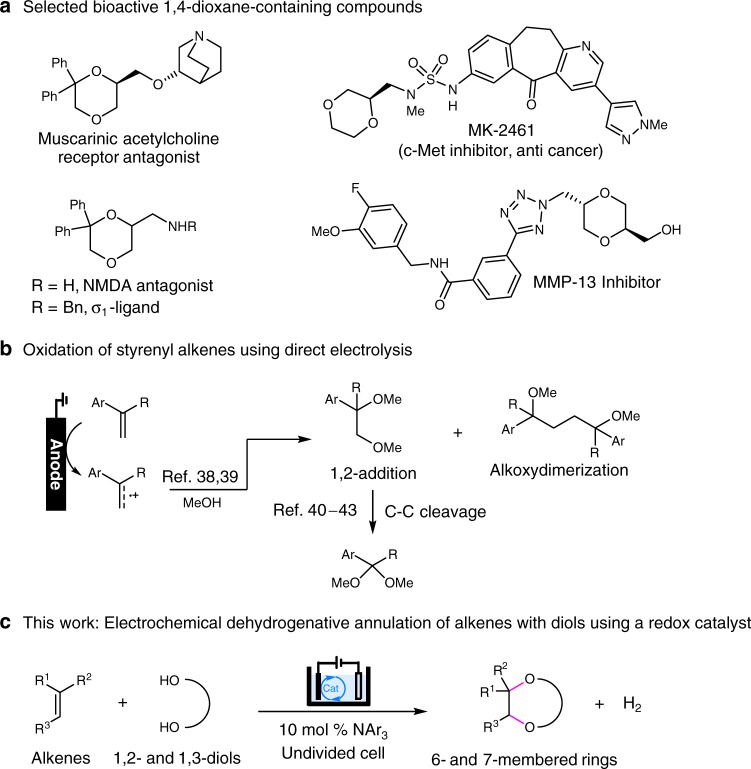

There has been mounting evidence to suggest that the number of saturated carbons and chiral centers in an organic molecule correlate strongly to its clinical prospect1–4. Because of this, saturated heterocycles have become increasingly crucial scaffolds for the development of new pharmaceutical compounds. However, unlike heteroaromatics, which can be synthesized conveniently via a variety of cross-coupling reactions, functionalized saturated heterocyclic ring systems have remained challenging to produce5–7. For example, the generation of 1,4-dioxane derivatives, which are prevalent in natural products and bioactive compounds (Fig. 1a)8–13, usually requires a lengthy synthetic procedure and/or complex starting materials that are themselves hard to obtain8–10,14,15.

Fig. 1.

Reaction design. a Selected bioactive molecules containing the 1,4-dioxane moiety. b Oxidation of styrenyl alkenes via direct electrolysis. c Synthesis of O-heterocycles via annulation reactions of alkenes with diols

Annulation reactions, in which two bonds are formed in a single step, are among the most-efficient methods for the synthesis of cyclic compounds16. Particularly, dehydrogenative annulation reactions via X–H (X=C or heteroatom) functionalization provide straightforward access to cyclic scaffolds from easily available substrates17–19. Although conventional dehydrogenative annulation reactions often involve the use of stoichiometric chemical oxidants, recent advances in organic electrochemistry20–30 have led to the development of safer and more environmentally sustainable alternatives that operate under oxidant-free conditions31–38. However, to the best of our knowledge, the synthesis of saturated heterocycles with 1,4-diheteroatoms through alkene annulation reactions has not been reported. Although the intramolecular anodic dioxygenation of heteroatom-substituted alkenes proceeds efficiently39,40, the intermolecular dimethoxylation of styrenyl alkenes with MeOH under similar conditions resulted in a mixture of compounds generated from 1,2-addition and alkoxydimerization (Fig. 1b)41,42, probably owing to the relatively high concentration of the alkene radical cation intermediates that were formed on the electrode surface. Moreover, the dimethoxylated product can undergo oxidative decomposition via C–C bond cleavage43–46.

To minimize the side reactions mentioned above, we argue that the use of redox catalysis47–58 can facilitate the formation of the desired radical cation in the bulk solution and reduce the electrode potential. Herein, we report a triarylamine-catalyzed electrochemical dehydrogenative annulation reaction of alkenes with 1,2- and 1,3-diols for the synthesis of 1,4-dioxane and 1,4-dioxepane scaffolds (Fig. 1c).

Results

Reaction optimization

The annulation of 1,1-diphenylethene 1 and ethylene glycol 2 was chosen as the model reaction for optimization (Table 1). The electrolysis was conducted in an undivided cell equipped with a reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) anode and a platinum plate cathode. The highest yield of the 1,4-dioxane product 4 was 91%, achieved when the reaction system consisted of triarylamine (2,4-Br2C6H3)3N (3)46,59 (Ep/2 = 1.48 V vs SCE) as the redox catalyst, iPrCO2H as acidic additive and an excess of 2 in refluxing MeCN (entry 1). Other redox mediators that had a lower oxidation potential than 3, such as (4-BrC6H4)3N (3a, Ep/2 = 1.06 V vs SCE), (4-MeO2CC6H4)3N (3b, Ep/2 = 1.26 V vs SCE) and the imidazole derivative 3c53 (Ep/2 = 1.19 V vs SCE), were less catalytically effective (entries 2–4). When no catalyst was used, the yield of 4 dropped to 58% and two additional byproducts, 5 and 6, were obtained in 16 and 6% yields, respectively (entry 5). Running the reaction at RT (entry 6), with only two equiv of 2 (entry 7), in the absence of iPrCO2H (entry 8), or with an alternative acidic additive such as AcOH (entry 9), EtCO2H (entry 10), CF3CO2H (entry 11), and TsOH (entry 12), all led to a significant decrease in reaction efficiency. The replacement of RVC with an anode material that had a smaller surface area, such as Pt (entry 13) or graphite (entry 14), also showed a detrimental effect on the formation of 4.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditionsa

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Deviation from standard conditions | Yield of 4 (%)b |

| 1 | None | 91c |

| 2 | (4-BrC6H4)3N (3a) as the catalyst | 5 (65) |

| 3 | (4-MeO2CC6H4)3N (3b) as the catalyst | 44 (38) |

| 4 | 3c as the catalyst | 38 (25) |

| 5 | No 3 | 58d (7) |

| 6 | Reaction at RT | 63 |

| 7 | 2 equiv of 2 | 28e |

| 8 | No iPrCO2H | 60 |

| 9 | AcOH as the acid | 77 |

| 10 | EtCO2H as the acid | 87 |

| 11 | CF3CO2H as the acid | 78 |

| 12 | TsOH•H2O as the acid | 80 |

| 13 | Pt plate (1 cm × 1 cm) as anode | 87 |

| 14 | Graphite plate (1 cm × 1 cm) as anode | 66 |

aReaction conditions: reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) anode (1 cm × 1 cm × 1.2 cm), Pt plate cathode (1 cm × 1 cm), 1 (0.2 mmol), 2 (0.5 mL, 9 mmol), MeCN (5.5 mL), Et4NPF6 (0.2 mmol), 12.5 mA (janode = 0.16 mA cm−2), 1.6 h

bDetermined by 1H NMR analysis using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as the internal standard. Unreacted 1 in parenthesis

cYield of isolated 4

d16% of 5 and 6% of 6

e8% of 5

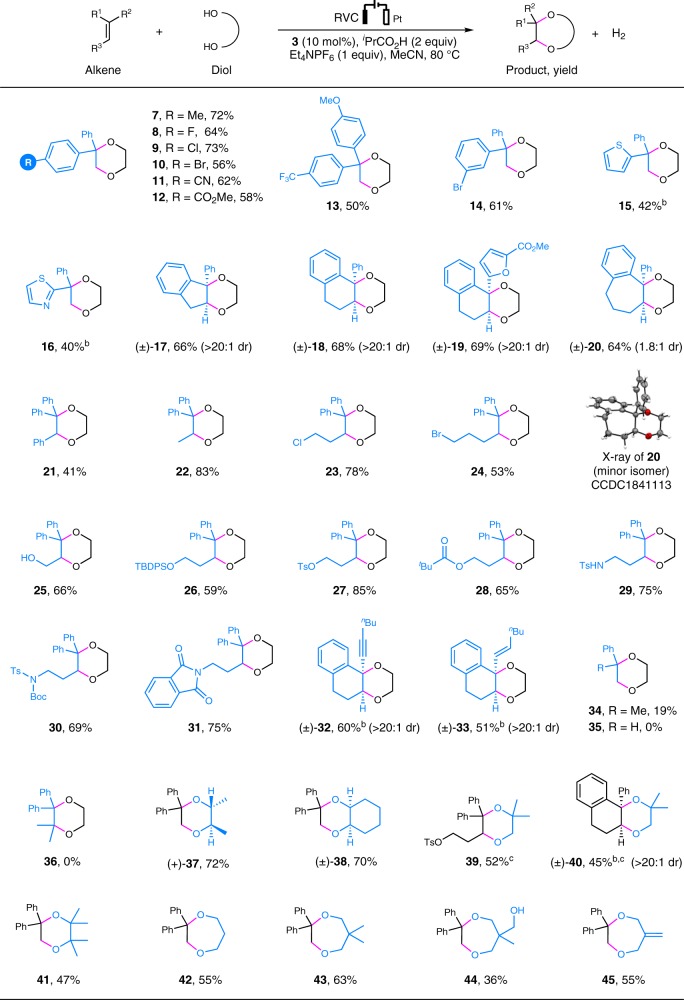

Substrate scope

We explored the substrate scope under the optimized conditions by first varying the substituents on the alkene (Table 2). The reaction was shown to be broadly compatible with different 1,1-diphenyl alkenes bearing substituents of diverse electronic properties at the para- or meta-position of the benzene ring (7–14). Meanwhile, alkenes functionalized with a 2-thiophenyl or 2-thiazolyl group were also tolerated (15, 16), albeit with slightly decreased reactivity. When a trisubstituted olefin whose C–C double bond was embedded in a five or six-membered ring was employed, the reaction afforded the cis-fused products (17–19) as the only diastereomer. However, the employment of a seven-membered cyclic alkene resulted in the generation of a mixture of diastereomers (20, dr = 1.8:1). The structure of the minor diastereomer of 20 was subsequently confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Trisubstituted acyclic alkenes (21–31) bearing a halogen (23, 24), free alcohol (25), silyl ether (26), tosylate (27), ester (28), sulfonamide (29, 30), or phthalimide (31) were all found to be suitable substrates. Furthermore, dioxanes 32 and 33 could be obtained in moderate yields from their corresponding enyne and diene precursors, respectively. It is worth emphasizing that a previous attempt at the anodic reaction of dienes with ethylene glycol generated a mixture of addition and dimerization products instead of the annulation product60. Current limitation of the annulation reaction included the inefficient reaction of α-methylstyrene (34, 19% yield) and the complete failure of styrene (35) and a tetrasubstituted alkene (36)

Table 2.

Substrate scope

TBDPS, tert-butyldiphenylsilyl; Ts, p-toluenesulfonyl; Boc, tert-butyloxycarbonyl

aReaction conditions: Alkene (0.2 mmol), diol (9 mmol), 1.7–4.5 h. All yields are isolated yields

bMeCN/CH2Cl2 (1:2) as solvent

c18 mmol of diol was employed

On the other hand, ethylene glycol could be replaced with other vicinal diols such as (2R,3 R)-(−)-2,3-butanediol (37), cis-1,2-cyclohexanediol (38), 2-methyl-1,2-propanediol (39, 40), 2,3-dimethyl-2,3-butanediol (41), and 1,3-diols (42–45). Notably, the unsymmetrically substituted diol 2-methyl-1,2-propanediol reacted regioselectively with different trisubstituted alkenes to afford 39 and 40 bearing two tetrasubstituted carbon centers.

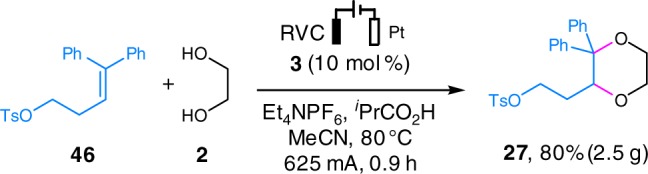

The electrochemical annulation reaction could be conducted on a gram scale as demonstrated by the preparation of 2.5 g of 27 in 80% yield from the annulation of the alkene 46 and 2 (Fig. 2). To allow the application of a higher current, a large anode 50 times the size of that used for the abovementioned model reaction was employed. Gratifyingly, the reaction was completed in < 1 hour, which provided rapid access to 27.

Fig. 2.

Electrochemical gram scale reaction. Gram scale synthesis of 27

Discussion

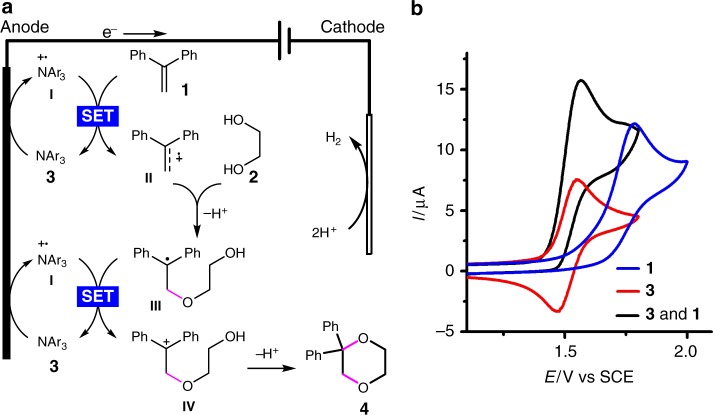

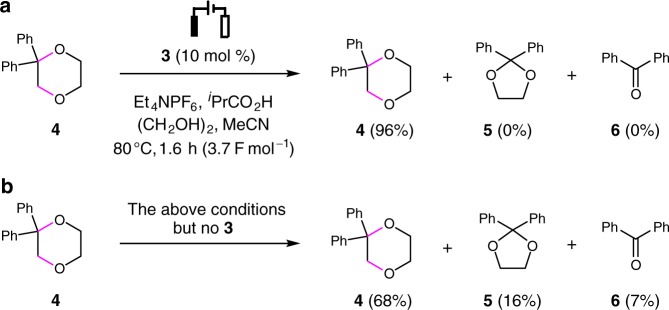

A reaction mechanism was proposed in Fig. 3a. The triarylamine catalyst 3 (Ep/2 = 1.48 V vs SCE) is first anodically oxidized into the radical cation I, which in turn oxidizes the alkene substrate 1 (Ep/2 = 1.68 V vs SCE) through single-electron transfer to furnish the corresponding radical cation II and regenerate 3. The nucleophilic trapping of II with ethylene glycol (2) and the subsequent deprotonation produce the carbon-centered radical III39,40,61–63, which is then oxidized by I to afford the carbon cation IV. The cyclization of IV eventually generates the 1,4-dioxane product 4 (Ep/2 = 1.95 V vs SCE). On the cathode, protons are reduced to produce H2. The addition of iPrCO2H facilitates H2 evolution and probably also plays an important role in reducing unwanted reduction of I, the CH2Cl2 solvent and the alkene substrate. The catalytic role of 3 was confirmed by the detection of a catalytic current47,64 using cyclic voltammetry (Fig. 3b). The inclusion of 3 was also found to inhibit the oxidative decomposition of 4, probably because of the inefficient oxidation of 4 by 3-derived radical cation I (Supplementary Fig. 1). This was supported by the observation that 4 remained largely stable when subjected to electrolysis in the presence of a catalytic amount of 3 (Fig. 4a). In contrast, under similar conditions but in the absence of 3, 32% of 4 was found to have decomposed, resulting in the formation of 1,3-dioxane 5 and benzophenone 6 in 16 and 7% yields, respectively (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 3.

Mechanistic rationale and cyclic voltammograms. a Mechanistic proposal. b Cyclic voltammograms recorded in MeCN/CH2Cl2 (6:1) with 0.1 M Et4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte. 3 (2.6 mM). 1 (1.3 mM). SET, single-electron transfer

Fig. 4.

Electrolysis of compound 4. a Electrolysis of 4 in the presence of triarylamine 3. b electrolysis of 4 in the absence of 3. Yields were determined by 1H NMR using 1,3,5-trimethoxygenzene as the internal standard

In summary, we have developed a triarylamine-catalyzed electrochemical annulation reaction for the synthesis of 1,4-dioxane and 1,4-dioxepane scaffolds from alkenes and diols. The reaction is compatible with a wide variety of functional groups and showed excellent tolerance for di- and trisubstituted alkenes, allowing facile access to functionalized O-heterocycles with tetrasubstituted carbon centers. We are currently investigating whether our alkene annulation reaction can be applied to the synthesis of other 1,4-heterocyclic compounds.

Methods

Representative procedure for the synthesis of 4

A 10-mL three-necked round-bottomed flask was charged with 3 (0.02 mmol, 0.1 equiv), the alkene 1 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv), ethylene glycol 2 (9 mmol, 45 equiv), iPrCO2H (0.4 mmol, 2 equiv), and Et4NPF6 (0.2 mmol, 1 equiv). The flask was equipped with a reflux condenser, a RVC anode (100 PPI (pores per inch), ~ 65 cm2 cm−3, 1 cm × 1 cm × 1.2 cm) and a platinum plate (1 cm × 1 cm) cathode before being flushed with argon. Then, anhydrous MeCN was added. Constant current (12.5 mA, janode = 0.16 mA cm−2) electrolysis was performed at reflux (internal temperature, 80 °C) until the alkene substrate was completely consumed (monitored by thin layer chromatography or 1H NMR). The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature (RT) and saturated Na2CO3 solution was added. The resulting mixture was extracted with EtOAc (3 × 20 mL). The combined organic solution was dried with anhydrous MgSO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was chromatographed through silica gel and the product 4 was obtained in 91% yield as a white solid by eluting with ethyl acetate/hexanes. All new compounds were fully characterized (See the Supplementary Information).

Procedure for the gram scale synthesis of 27

The gram scale synthesis of compound 27 (80%, 2.5 g) was conducted in a 200-mL beaker-type cell with two RVC plates (100 PPI, 5 cm × 5 cm × 1.2 cm) as anode and a Pt plate cathode (3 cm × 3 cm) at constant current of 625 mA (janode = 0.16 mA cm−2) for 0.9 h. The reaction mixture consisted of compound 2 (15 mL, 262 mmol), 46 (2.2 g, 5.8 mmol), 3 (0.42 g, 0.58 mmol), iPrCO2H (1.1 mL, 11.6 mmol), MeCN (180 mL), and Et4NPF6 (1.6 g, 5.8 mmol).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support of this research from MOST (2016YFA0204100), NSFC (No. 21672178), the “Thousand Youth Talents Plan”, and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author contributions

C.Y.C. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. H.C.X. designed and directed the project and wrote the manuscript.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1841113 (20). The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre [http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif]. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Any further relevant data are available from the authors on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41467-018-06020-8.

References

- 1.Lovering F. Escape from flatland 2: complexity and promiscuity. Med. Chem. Commun. 2013;4:515–519. doi: 10.1039/c2md20347b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humblet C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritchie TJ, Macdonald SJF, Young RJ, Pickett SD. The impact of aromatic ring count on compound developability: further insights by examining carbo- and hetero-aromatic and -aliphatic ring types. Drug Discov. Today. 2011;16:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morley AD, et al. Fragment-based hit identification: thinking in 3D. Drug Discov. Today. 2013;18:1221–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Over B, et al. Natural-product-derived fragments for fragment-based ligand discovery. Nat. Chem. 2012;5:21–28. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vo CVT, Luescher MU, Bode JW. SnAP reagents for the one-step synthesis of medium-ring saturated N-heterocycles from aldehydes. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:310–314. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye Z, Adhikari S, Xia Y, Dai M. Expedient syntheses of N-heterocycles via intermolecular amphoteric diamination of allenes. Nat. Commum. 2018;9:721. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03085-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Del Bello F, et al. Novel muscarinic acetylcholine receptor hybrid ligands embedding quinuclidine and 1,4-dioxane fragments. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017;137:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Bello F, et al. 1,4-dioxane, a suitable scaffold for the development of novel M3 muscarinic receptor antagonists. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:1783–1787. doi: 10.1021/jm2013216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonifazi A, et al. Novel potent N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists or σ1 receptor ligands based on properly substituted 1,4-dioxane ring. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:8601–8615. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu T, et al. Synthetic silvestrol analogues as potent and selective protein synthesis inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:8859–8878. doi: 10.1021/jm3011542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katz JD, et al. Discovery of a 5H-benzo[4,5]cyclohepta[1,2-b]pyridin-5-one (MK-2461) inhibitor of c-Met kinase for the treatment of cancer. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:4092–4108. doi: 10.1021/jm200112k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruminski PG, et al. Discovery of N-(4-fluoro-3-methoxybenzyl)-6-(2-(((2S,5R)-5-(hydroxymethyl)-1,4-dioxan-2-yl)methyl)-2H-tetrazol-5-yl)-2-methylpyrimidine-4-carboxamide. A highly selective and orally bioavailable matrix metalloproteinase-13 inhibitor for the potential treatment of osteoarthritis. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:313–327. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang W, Sun J. Organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of 1,4-dioxanes and other oxa-heterocycles by oxetane desymmetrization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;128:1900–1903. doi: 10.1002/ange.201509888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiecco M, et al. Synthesis of enantiomerically pure 1,4-dioxanes from alkenes promoted by organoselenium reagents. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:1095–1102. doi: 10.1016/S0957-4166(03)00124-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molander GA. Diverse methods for medium ring synthesis. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:603–609. doi: 10.1021/ar960101v. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moisés G, Luis MJ. Metal-catalyzed annulations through activation and cleavage of C-H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:11000–11019. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ackermann L. Carboxylate-assisted ruthenium-catalyzed alkyne annulations by C-H/het-H bond functionalizations. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:281–295. doi: 10.1021/ar3002798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou, Z.-W., Mao, Z.-Y. & Xu, H.-C. Recent progress on the Synthesis of (aza)indoles through oxidative alkyne annulation reactions. Synlett28, 1867–1872 (2017).

- 20.Yoshida J, Kataoka K, Horcajada R, Nagaki A. Modern strategies in electroorganic synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2265–2299. doi: 10.1021/cr0680843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan M, Kawamata Y, Baran PS. Synthetic organic electrochemical methods since 2000: on the verge of a renaissance. Chem. Rev. 2017;117:13230–13319. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang Y, Xu K, Zeng C. Use of electrochemistry in the synthesis of heterocyclic structures. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4485–4540. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anton W, et al. Electrifying organic synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5594–5619. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang S, Liu Y, Lei A. Electrochemical oxidative cross-coupling with hydrogen evolution: a green and sustainable way for bond formation. Chem. 2018;4:27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2017.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang QL, Fang P, Mei TS. Recent advances in organic electrochemical C-H functionalization. Chin. J. Chem. 2018;36:338–352. doi: 10.1002/cjoc.201700740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida Ji, Shimizu A, Hayashi R. Electrogenerated cationic reactive intermediates: the pool method and further advances. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4702–4730. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moeller KD. Using physical organic chemistry to shape the course of electrochemical reactions. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4817–4833. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauermann N, Meyer TH, Qiu Y, Ackermann L. Electrocatalytic C–H activation. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7086–7103. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma C, Fang P, Mei TS. Recent advances in C–H functionalization using electrochemical transition metal catalysis. ACS Catal. 2018;8:7179–7189. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b01697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kärkäs, M. D. Electrochemical strategies for C–H functionalization and C–N bond formation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 5786–5865 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Liu K, Tang S, Huang P, Lei A. External oxidant‐free electrooxidative [3 + 2] annulation between phenol and indole derivatives. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:775. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00873-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang G, et al. Oxidative [4 + 2] annulation of styrenes with alkynes under external‐oxidant‐free conditions. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1225. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cong T, Leonardo M, TH M, Lutz A. Electrochemical C–H/N–H activation by water‐tolerant cobalt catalysis at room temperature. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:2383–2387. doi: 10.1002/anie.201712647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Youai Q, Cong T, Leonardo M, Torben R, Lutz A. Electrooxidative ruthenium‐catalyzed C−H/O−H annulation by weak O‐coordination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5818–5822. doi: 10.1002/anie.201802748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu F, Li YJ, Huang C, Xu HC. Ruthenium-catalyzed electrochemical dehydrogenative alkyne annulation. ACS Catal. 2018;8:3820–3824. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.8b00373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hou ZW, et al. Electrochemical C-H/N-H functionalization for the synthesis of highly functionalized (aza)indoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:9168–9172. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen J, et al. Electrocatalytic aziridination of alkenes mediated by n-Bu4NI: a radical pathway. Org. Lett. 2015;17:986–989. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jin L, et al. Electrochemical aziridination by alkene activation using a sulfamate as the nitrogen source. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:5695–5698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201801106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu B, Duan S, Sutterer AC, Moeller KD. Oxidative cyclization based on reversing the polarity of enol ethers and ketene dithioacetals. Construction of a tetrahydrofuran ring and application to the synthesis of (+)-nemorensic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:10101–10111. doi: 10.1021/ja026739l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Y, Liu B, Kao J, d’Avignon DA, Moeller KD. Anodic cyclization reactions: reversing the polarity of ketene dithioacetal groups. Org. Lett. 2001;3:1729–1732. doi: 10.1021/ol015925d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engels R, Schäfer Hans J, Steckhan E. Anodische oxidation von arylolefinen. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1977;1977:204–224. doi: 10.1002/jlac.197719770203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kojima M, Sakuragi H, Tokumaru K. Electrochemical oxidation of aromatic olefins. Dependence of the reaction course on the structure of the olefins and on the nature of the anodes. Chem. Lett. 1981;10:1707–1710. doi: 10.1246/cl.1981.1707. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ogibin YN, Ilovaisky AI, Nikishin GI. Electrochemical cleavage of double bonds in conjugated cycloalkenyl- and 1,2-alkenobenzenes. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:3256–3258. doi: 10.1021/jo951948s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ogibin YN, Sokolov AB, Ilovaiskii AI, Élinson MN, Nikishin GI. Electrochemical cleavage of the double bond of 1-alkenylarenes. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Soc. 1991;40:561–566. doi: 10.1007/BF00957996. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okajima M, Suga S, Itami K, Yoshida Ji. “Cation pool” method based on C−C bond dissociation. Effective generation of monocations and dications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:6930–6931. doi: 10.1021/ja050414y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu X, Davis AP, Fry AJ. Electrocatalytic oxidative cleavage of electron-deficient substituted stilbenes in acetonitrile–water employing a new high oxidation potential electrocatalyst. An electrochemical equivalent of ozonolysis. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5633–5636. doi: 10.1021/ol7026416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Francke R, Little RD. Redox catalysis in organic electrosynthesis: basic principles and recent developments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:2492–2521. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60464k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steckhan E. Indirect electroorganic syntheses - a modern chapter of organic electrochemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1986;25:683–701. doi: 10.1002/anie.198606831. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nutting JE, Rafiee M, Stahl SS. Tetramethylpiperidine N-oxyl (TEMPO), phthalimide N-oxyl (PINO), and related N-oxyl species: electrochemical properties and their use in electrocatalytic reactions. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:4834–4885. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fu N, Sauer GS, Saha A, Loo A, Lin S. Metal-catalyzed electrochemical diazidation of alkenes. Science. 2017;357:575–579. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Badalyan A, Stahl SS. Cooperative electrocatalytic alcohol oxidation with electron-proton-transfer mediators. Nature. 2016;535:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature18008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng CC, Zhang NT, Lam CM, Little RD. Novel triarylimidazole redox catalysts: synthesis, electrochemical properties, and applicability to electrooxidative C–H activation. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1314–1317. doi: 10.1021/ol300195c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Francke R, Little RD. Optimizing electron transfer mediators based on arylimidazoles by ring fusion: Synthesis, electrochemistry, and computational analysis of 2-aryl-1-methylphenanthro[9,10-d]imidazoles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:427–435. doi: 10.1021/ja410865z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horn EJ, et al. Scalable and sustainable electrochemical allylic C-H oxidation. Nature. 2016;533:77–81. doi: 10.1038/nature17431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Philipp R, Steffen E, Alexander KC, Gerhard H. Efficient oxidative coupling of arenes via electrochemical regeneration of 2,3‐dichloro‐5,6‐dicyano‐1,4‐benzoquinone (DDQ) under mild reaction conditions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2017;359:1359–1372. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201601331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hou ZW, Mao ZY, Melcamu YY, Lu X, Xu HC. Electrochemical synthesis of imidazo-fused N-heteroaromatic compounds through a C–N bond-forming radical cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:1636–1639. doi: 10.1002/anie.201711876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kawamata Y, et al. Scalable, electrochemical oxidation of unactivated C–H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:7448–7451. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rafiee M, Wang F, Hruszkewycz DP, Stahl SS. N-hydroxyphthalimide-mediated electrochemical iodination of methylarenes and comparison to electron-transfer-initiated C–H functionalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:22–25. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shen Y, Hattori H, Ding K, Atobe M, Fuchigami T. Triarylamine mediated desulfurization of S-arylthiobenzoates and a tosylhydrazone derivative. Electrochim. Acta. 2006;51:2819–2824. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2005.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baltes H, Stork L, Schäfer HJ. Anodische oxidation organischer verbindungen, 23 anodische addition von harnstoffen und ethylenglykol an konjugierte diene. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1979;1979:318–327. doi: 10.1002/jlac.197919790304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yi H, et al. Photocatalytic dehydrogenative cross‐coupling of alkenes with alcohols or azoles without external oxidant. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:1120–1124. doi: 10.1002/anie.201609274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilger DJ, Grandjean JMM, Lammert TR, Nicewicz DA. The direct anti-Markovnikov addition of mineral acids to styrenes. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:720. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Johnston LJ, Schepp NP. Reactivities of radical cations: characterization of styrene radical cations and measurements of their reactivity toward nucleophiles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:6564–6571. doi: 10.1021/ja00068a013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wu ZJ, Xu HC. Synthesis of C3-fluorinated oxindoles through reagent-free cross-dehydrogenative coupling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:4734–4738. doi: 10.1002/anie.201701329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1841113 (20). The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre [http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif]. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Any further relevant data are available from the authors on request.