Abstract

In the mature healthy mammalian neuronal networks, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) mediates synaptic inhibition by acting on GABAA and GABAB receptors (GABAAR, GABABR). In immature networks and during numerous pathological conditions the strength of GABAergic synaptic inhibition is much less pronounced. In these neurons the activation of GABAAR produces paradoxical depolarizing action that favors neuronal network excitation. The depolarizing action of GABAAR is a consequence of deregulated chloride ion homeostasis. In addition to depolarizing action of GABAAR, the GABABR mediated inhibition is also less efficient. One of the key molecules regulating the GABAergic synaptic transmission is the brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF and its precursor proBDNF, can be released in an activity-dependent manner. Mature BDNF operates via its cognate receptors tropomyosin related kinase B (TrkB) whereas proBDNF binds the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR). In this review article, we discuss recent finding illuminating how mBDNF-TrkB and proBDNF-p75NTR signaling pathways regulate GABA related neurotransmission under physiological conditions and during epilepsy.

Keywords: BDNF, TrkB, p75NTR, GABA receptors, KCC2

Introduction

A striking trait of early GABAergic transmission is that activation of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABAA) receptors (GABAARs) causes membrane depolarization and Ca2+ influx in immature neurons (Ben-Ari et al., 1989, 2007; Ganguly et al., 2001). During this critical period, depolarizing GABAAR activity plays a major role in neuronal network construction (Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Wang and Kriegstein, 2008; Sernagor et al., 2010). Given this fundamental role it comes as no surprise that flawed GABAergic transmission is implicated in an array of brain disorders such as epilepsy (Ben-Ari and Holmes, 2005), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Rett syndrome (Kuzirian and Paradis, 2011), schizophrenia (Lewis et al., 2005; Charych et al., 2009; Mueller et al., 2015) and major depressive disorder (Sanacora et al., 1999; Brambilla et al., 2003). GABAergic development relies heavily on brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; Hong et al., 2008; Gottmann et al., 2009; Sakata et al., 2009; Kuzirian and Paradis, 2011), one of the most crucial regulator of synapse development and function in the developing and adult central nervous system (CNS; Lu et al., 2005; Cohen-Cory et al., 2010). BDNF can be secreted either as a precursor (proBDNF) or a mature form (mBDNF; Nagappan et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2009). ProBDNF and mBDNF modulate the efficacy of synaptic responses via the tropomyosin-related kinase receptor B (TrkB) and the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), respectively (Lu et al., 2005). BDNF shapes the development of neuronal circuits, as well as the construction of inhibitory connections throughout life (Kovalchuk et al., 2004; Gubellini et al., 2005; Gottmann et al., 2009) and alterations in BDNF processing have been observed in diseases of the CNS, including schizophrenia, ASD and epilepsy (Binder et al., 2001; Carlino et al., 2011; Garcia et al., 2012). In this review article, we discuss the recent achievements in analysis of the development of GABAergic network with an emphasis on GABA and BDNF interplay. We particularly focus on ionotropic GABAA or metabotropic GABAB receptors activation in triggering the postsynaptic release of BDNF, which in turn regulates the maturation of GABAergic synapses. We then discuss how BDNF tunes up or down inhibitory transmission by acting on synthesis and trafficking of GABAARs and KCC2 chloride ion transporters at the cell membrane. Finally, we focus on epilepsy, a pathology that highlights the links between GABA and BDNF.

BDNF and Inhibitory Strength of GABAA Receptors

GABAARs are ionotropic receptors that allow the bidirectional flux of chloride ions across the neuronal membrane. The direction of Cl− flux depends on [Cl−]i and the membrane potential, whereas the intensity of the flux depends on the number of activated GABAARs. In mature healthy neurons the [Cl−]i is close to 4 mM, and the reversal potential of the ion flux through GABAARs (EGABAA) is ~78–82 mV, close to the resting membrane potential (Tyzio et al., 2003; Khazipov et al., 2004). Hence, at rest, the activation of GABAARs produces no or, at the most, a weak (1–2 mV) hyperpolarization or depolarization. The activation of GABAARs during neuronal depolarization induced by the excitatory synapses allows massive Cl− entry that provides strong hyperpolarizing force and effectively compensates or diminishes the strength of the excitatory signal. The increased [Cl−]i is rapidly extruded by electroneutral neuron-specific potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 (Rivera et al., 1999). In immature neurons as well as in mature neurons during different pathologies (epilepsy (Cohen et al., 2002), acute trauma (Boulenguez et al., 2010), Rett syndrome (Banerjee et al., 2016), Down syndrome (Deidda et al., 2015), Huntington disease (Dargaei et al., 2018), ASD (Tyzio et al., 2014)) the activation of GABAARs produces neuron depolarization reflecting increased resting level of [Cl−]i. This Cl−-dependent depolarization facilitated the activation of the neuronal network and contributes to the formation of pathological patterns of network activities (Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Moore et al., 2017). Thus, the inhibitory strength of GABAAR mediated inhibition is determined by two complementary parameters: the amount of ion flux through opened GABAARs and the [Cl−]i. The mBDNF and proBDNF do regulate these two parameters.

ProBDNF, mBDNF and GABAAR Interplay

Expression patterns of BDNF and proBDNF are developmentally regulated. ProBDNF expression levels increase during the first postnatal weeks while mature BDNF peaks at a later period (Yang et al., 2014; Menshanov et al., 2015; Winnubst et al., 2015). ProBDNF can be cleaved under physiological conditions depending mainly on neuronal activity generated in the developing neuronal networks (Lessmann and Brigadski, 2009; Nagappan et al., 2009; Langlois et al., 2013). For instance, theta burst stimulation triggers the co-release of proBDNF and the serine protease, tissue Plasminogen Activator (t-PA) which converts plasminogen to plasmin yielding to mature BDNF, whereas low-frequency stimulation increases the amounts of proBDNF in the extracellular space (Nagappan et al., 2009). Overexpression of proBDNF in proBDNF-HA/+ mice showed a decrease in dendritic arborization and spine density of hippocampal neurons as well as altered synaptic transmission (Yang et al., 2014). In developing rat hippocampal neurons, proBDNF/p75NTR signaling has been reported to induces a long-lasting depression of GABAAR-mediated synaptic activity (Langlois et al., 2013), whereas endogenous BDNF/TrkB signaling is required for the induction of GABAergic long-term-potentiation (Gubellini et al., 2005).

In the cerebral cortex, BDNF/TrkB signaling controls the development of interneurons (Yuan et al., 2016) and the expression of the presynaptic GABA synthetic enzyme GAD65 (Sánchez-Huertas and Rico, 2011). In the cerebellum, BDNF promotes the formation of inhibitory synapses (Chen et al., 2016). Postsynaptically, BDNF and proBDNF are critical to control the GABAARs trafficking between synaptic sites and endosomal compartments. The cell membrane expression of GABAARs depends on their phosphorylation level (Nakamura et al., 2015). Thus, dephosphorylation of the GABAAR ß3 subunits triggers the association with the assembly polypeptide 2 (AP2) complex which leads to a clathrin-mediated internalization (Kittler et al., 2000; Nakamura et al., 2015). In fact, BDNF/TrkB signaling inhibits the internalization of GABAARs through activation of the phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI-3 kinase) and PKC pathways (Figure 1). This ability of BDNF to modulate GABAARs endocytosis and activity is likely to occur due to an inhibition of their interaction with the protein phosphatase 2A complex (PP2A), a downstream target of PI-3 kinase (Jovanovic et al., 2004; Vasudevan et al., 2011). Inversely, application of proBDNF to cultured rat hippocampal neurons cause a reduction in GABAergic synaptic transmission by promoting dephosphorylation and internalization of GABAAR ß3 subunits through the RhoA–Rock–PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog) signaling cascade (Riffault et al., 2014). The underlying molecular mechanism of PTEN-mediated dephosphorylation and downregulation of GABAARs remains to be determined but may involve the inhibition of PI3-kinase activity and the subsequent upregulation of PP2A activity. Accordingly, PTEN activated by p75NTR is a major negative regulator of the PI3-kinase signaling cascade (Song et al., 2010). Thus, the cell surface expression levels of GABAARs can be settled by the competition between mBDNF/TrkB and proBDNF/p75NTR intracellular cascades on the PTEN/PI3-kinase-mediated activation of PP2A. After endocytosis, the proBDNF/p75NTR/Rho-ROCK pathway moved internalized GABAARs to late endosomes and finally to lysosomes for degradation (Riffault et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

mBDNF/TrkB and proBDNF/p75NTR signaling pathways regulate γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) neurotransmission. Activation of TrkB receptors by mBDNF leads to an inhibition of GABAAR endocytosis and a consequent increase in the cell surface expression of these receptors through the PI 3-kinase and the PKC signaling pathway. At the transcriptional level, BDNF/TrkB signaling regulates GABAAR and KCC2 gene expression through the Shc, PLC/CaMK or MAP/ERK pathways. Activation of p75NTR by proBDNF decreases GABAARs cell surface expression through the RhoA/ROCK/PTEN pathway that leads to the dephosphorylation of GABAAR and endocytosis and degradation of internalized receptors. At the transcriptional level, proBNDF/P75NTR leads to the repression of GABAAR synthesis through the JAK2/STAT3/ICER pathway. The proBDNF/75NTR signaling also decreases KCC2 expression.

The BDNF may also be involved in GABAARs clustering at synaptic sites through the regulation of the main scaffolding protein gephyrin. Indeed, in immature rat hippocampal neuronal cultures BDNF enhanced the expression and clustering of gephyrin, which in turn leads to an increase in the density of GABAARs-gephyrin containing complexes at postsynaptic sites (González, 2014). Conversely, in cultured mouse amygdala neurons, rapid application of BDNF decreased the cell surface expression of GABAARs-gephyrin complexes whereas long-term treatment with BDNF elicits opposite effects (Mou et al., 2013). BDNF can exert different roles depending on the developmental stages (young vs. adult neurons) but also in function of the brain structures or according to the delivery mode (rapid vs. long-term treatment). These opposing responses of BDNF on GABAARS clustering may reflect the differences in the kinetics of TrkB activation (Ji et al., 2010) and may contribute to the homeostatic regulation of GABAergic synaptic strength (Tyagarajan and Fritschy, 2010; Vlachos et al., 2013; Brady et al., 2018).

After its release into the synaptic cleft, the activity of GABA is terminated by the reuptake of the neurotransmitter, a process mediated by the GABA transporters (GATs). The surface expression of GABA transporter-1 (GAT-1), the major GABA transporter expressed by both neurons and astrocytes (Guastella et al., 1990), is upregulated in neuronal cells by BDNF-mediated tyrosine kinase-dependent phosphorylation (Law et al., 2000; Whitworth and Quick, 2001). However, the neurotrophin was found to inhibit GAT-1-mediated GABA transport at the isolated nerve endings (Vaz et al., 2008), suggesting that this effect is very localized, to delay GABA uptake by the nerve terminal, thereby enhancing synaptic actions of GABA. In contrast with the effects at the synapse, BDNF may accelerate the uptake of GABA at extrasynaptic sites, allowing replenishment of neuronal pools of GABA. Furthermore, BDNF enhances GABA transport in rat cortical astrocytes by modulating the trafficking of GAT-1 from the plasma membrane (Vaz et al., 2011).

BDNF also regulates genes transcription of GABAAR subunits (Bell-Horner et al., 2006) GAD65 (Sánchez-Huertas and Rico, 2011) and GATs (Vaz et al., 2011), through the recruitment of the ERK-MAP kinase cascade, which activates the cAMP-response element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB; Figure 1; Yoshii and Constantine-Paton, 2010). In an opposite way, the downstream signaling pathway triggered by proBDNF/p75NTR activates the JAK-STAT pathway leading to the induction of the cAMP early repressor ICER, which mediates the downregulation of GABAARs ß3 gene synthesis (Figure 1). Interestingly, the activation of this pathway precedes the decrease of GABAARs ß3 cell surface expression (Riffault et al., 2014).

Other reports have also suggested that in rat visual cortex and cerebellar Purkinje cells, the BDNF/TrkB signaling modulates GABAARs mediated currents through the PLCγ-Ca2 + and CaMK pathways (Cheng and Yeh, 2003; Mizoguchi et al., 2003). In immature cultured rat hippocampal and hypothalamic neurons, the BDNF/TrkB dependent increase in GABAARs plasma membrane expression occurs when activation of GABAARs lead to a depolarization of the membrane potential, which in turn triggers the release of BDNF (Obrietan et al., 2002; Porcher et al., 2011). In more mature cultured rat hippocampal neurons and murine cerebellar granule cells, BDNF decreases the plasma membrane expression of GABAARs (Brünig et al., 2001; Cheng and Yeh, 2003). In parallel, BDNF/trkB signaling reduces the excitability of parvalbumin-positive interneurons in the mouse dentate gyrus (Holm et al., 2009). Surprisingly, these neurons do not express the proBDNF receptor p75NTR (Dougherty and Milner, 1999; Holm et al., 2009). The change in the regulation of GABAARs cell surface expression by BDNF coincides with a shift in GABA polarity (depolarization to hyperpolarization), attributed to the activity of KCC2 (Rivera et al., 1999) which is also regulated by both forms of BDNF. A recent study showed that increased proBDNF/p75NTR signaling disrupts the developmental GABAergic sequence by maintaining a depolarizing GABA response in a KCC2-dependent manner in mature cortical neurons (Riffault et al., 2018). In developing neurons, BDNF increases KCC2 expression on the level of mRNA transcription (Aguado et al., 2003; Rivera et al., 2004; Ludwig et al., 2011). In line with these observations, it was shown that the expression of KCC2 is significantly decreased in trkB−/– mice hippocampi (Carmona et al., 2006) whereas, in adult neurons BDNF decreases both mRNA and protein KCC2 (Rivera et al., 2002, 2004; Wake et al., 2007; Shulga et al., 2008; Boulenguez et al., 2010). In accordance with these results, neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord treated with BDNF showed a depolarizing shift of the GABA reversal potential (Coull et al., 2003, 2005). The actions of BDNF/TrkB signaling on GABAergic synapses are developmentally regulated, with BDNF leading to an increase of KCC2 expression in immature neurons through activation of Shc pathway, and a decrease in adult neurons through activation of both Shc and PLCγ cascades (Rivera et al., 2002, 2004; Figure 1).

Altogether, these findings suggest that the relative availability of the two forms of BDNF, pro and mature, could affect the excitatory/inhibitory balance during the development by regulating the polarity and the synaptic strength of GABAergic transmission.

GABABR and BDNF Interplay

Similarly to BDNF, a crucial factor regulating the development of inhibitory transmission is GABA itself (Ben-Ari et al., 2007; Gaiarsa et al., 2011). In the neocortex, extracellular GABA signaling regulates the development of GABAergic inhibition through GABAA and GABAB receptors. During the developmental period, ambient GABA may also participate in neuronal network construction and synaptogenesis. In the visual cortex of mice, Chattopadhyaya et al. (2007) demonstrated that the tonic activation of GABAA and GABAB receptors regulates the axonal branching of basket-cell interneurons. They reported that reducing GABA levels in a single basket cell results in a decrease of perisomatic GABAergic inputs on the pyramidal cells. This deficit of synaptic transmission is partially restored by GABA uptake blocker or GABAA and GABAB receptor agonists. In agreement with this study, knockout of the GABAB1 subunit leads to altered maturation of GABAergic synaptic transmission in murine hippocampal neurons and synaptic activation of GABABRs promotes the development of GABAergic synapses (Fiorentino et al., 2009). The mechanisms are not fully understood but may likely involve the BDNF/TrkB signaling. Indeed, the trophic action of GABABRs was prevented by BDNF scavenger (TRkB-IgG) and not observed in BDNF KO mice (Fiorentino et al., 2009). Moreover, the stimulation of GABABRs induce a calcium-dependent release of BDNF via the PLC-PKC signaling cascade and L-type voltage-gated calcium channels (Fiorentino et al., 2009; Kuczewski et al., 2011). Finally, in the developing rat hippocampus, it was shown that activation of GABABRs also increased the phosphorylation levels of the α-CamKII, which play a critical role in BDNF release (Fischer et al., 2005; Kolarow et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2008). Therefore, postsynaptic calcium increase and phosphorylation of α-CamKII may underlie the GABAB-R-mediated release of BDNF. Interestingly, the regulated secretion of BDNF following GABAB receptor activation increases the number of GABAA ß2/3 subunits receptors at the postsynaptic membrane (Kuczewski et al., 2011). Thus, the interplay between GABABRs activation and the subsequent BDNF secretion in developing hippocampal neurons contribute to the functional maturation of GABAergic synaptic transmission.

BDNF and GABA Interplay in Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a brain disorder characterized by the appearance of spontaneous recurrent seizures due to network hyperexcitability (Fischer et al., 2005). Neurotrophic signaling pathways are over-activated after status epilepticus (SE) and seem to contribute to epileptogenesis by promoting neuronal cell deaths and rewiring of excitatory networks (Koyama et al., 2004; Unsain et al., 2008; Goldberg and Coulter, 2013). Similarly, changes in GABAergic neurotransmission and altered neuronal Cl− homeostasis are considered to play a crucial role in epileptogenesis. Initial studies regarding the contribution of BDNF to epilepsy led to conflicting conclusions, with intrahippocampal BDNF perfusion or intraventricular injection of the BDNF scavenger TrkB-IgG, both being protective in a model of dorsal hippocampal kindling (Reibel et al., 2000; Binder et al., 2001). However, further studies reported that epileptogenesis was suppressed in mice with conditional deletion of TrkB in the brain (He et al., 2004) as well as in mice carrying a TrkB gene mutation that uncouples TrkB from the PLCγ (He et al., 2010). Interestingly, elevated levels of BDNF and TrkB following seizure activity or bath application of BDNF on hippocampal neurons trigger a down-regulation of KCC2 surface expression and a subsequent increase in neuronal excitability which most likely contributes to the establishment of recurrent seizures (Rivera et al., 2002; Wake et al., 2007). In addition to the pro-epileptogenic effect of mBDNF, it has been shown that proBDNF and p75NTR are markedly increased after Pilocarpine-induced seizures. The elevated amounts of proBDNF following SE are associated with reduced proBDNF cleavage machinery that results from acute decreases in tPA/plasminogen proteolytic cascade and increases in API-1, an inhibitor of proBDNF cleavage (Reibel et al., 2000; Binder et al., 2001). Furthermore, two recent studies showed that proBDNF/p75NTR response following SE selectively downregulates KCC2, which in turn promotes a chloride homeostasis dysregulation leading to an excitatory action of GABAA receptors and facilitate epileptiform discharges (Kourdougli et al., 2017; Riffault et al., 2018; Figure 2). Interestingly, blockade of p75NTR during the earliest phase of epileptogenesis restores KCC2 levels and reduces seizures frequency (Kourdougli et al., 2017; Riffault et al., 2018). These results suggest that proBDNF/p75NTR play a critical role in the mechanisms of epileptogenesis (see Figure 2). It should be pointed, however, that apart from these pro-epileptogenic actions, BDNF could exert anti-epileptic effects (Paradiso et al., 2009; Bovolenta et al., 2010). Several observations support the view that at least part of the pro-epileptogenic actions of pro- or mature-BDNF relies on an alteration of GABAergic inhibition. Thus, although BDNF exerts beneficial effects on developing GABAergic synapses, exogenous applications of this neurotrophin decrease the efficacy of GABAergic inhibition on mature neurons (Berninger et al., 1995; Mizoguchi et al., 2003). In cultured hippocampal neurons, proBDNF promotes GABAA receptor endocytosis and degradation (Riffault et al., 2014) and BDNF has been reported to reduce the probability of GABA release (Mizoguchi et al., 2003). At the transcriptional level, BDNF/TrkB signaling causes the repression of GABAARs α1 subunit gene through the activation of JAK-STAT pathway following SE (Lund et al., 2008). An important feature of epileptogenesis is a downregulation of KCC2 expression both in human epileptogenic tissues (Aronica et al., 2007; Huberfeld et al., 2007; Munakata et al., 2007; Shimizu-Okabe et al., 2011; Kahle et al., 2014) and in animal models of epilepsy (Jin et al., 2005; Kourdougli et al., 2017; Riffault et al., 2018). In patients with temporal lobe epilepsy, the decrease in KCC2 expression results in depolarizing GABAergic events in a minority of subicular pyramidal cells that contribute to inter-ictal like activity (Cohen et al., 2002; Huberfeld et al., 2007). These findings are consistent with reports of KCC2 downregulation and changes in the polarity of GABAergic response in animal models of epilepsy (Huberfeld et al., 2007; Barmashenko et al., 2011; Shimizu-Okabe et al., 2011; Kourdougli et al., 2017; Riffault et al., 2018). Because both forms of BDNF regulate the expression of KCC2 (Rivera et al., 1999; Ludwig et al., 2011), the decrease observed in epileptic tissues could be due to an imbalance between mBDNF/TrkB and proBDNF/p75NTR signaling during the first postnatal weeks causing an impaired or delayed functional maturation of GABAergic inhibition. Alternatively, an excess of BDNF production and secretion associated with reductions in proBDNF cleavage in epileptic tissues (Ernfors et al., 1991; Thomas et al., 2016) could account for the decrease in KCC2 expression (Figure 2). Altogether, these findings show a complex picture in which BDNF signaling can influence the pathogenicity of epilepsy both ways. Further studies will be necessary to precise the role of the extracellular proBDNF/mBDNF ratio in GABAergic transmission during neuronal development and in different types of epilepsies.

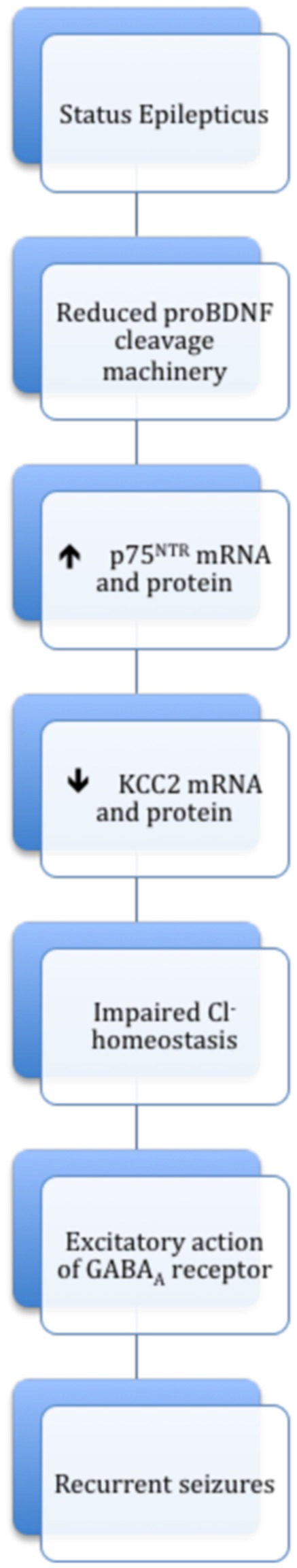

Figure 2.

Scheme summarizing the causal relationship between proBDNF/p75NTR and depolarizing action of GABA during epileptogenesis. Elevated amounts of proBDNF following status epilepticus (SE) are associated with reduced proBDNF cleavage machinery and increased expression of p75NTR. The proBDNF/p75NTR response donwregulates KCC2, which promotes a chloride homeostasis dysregulation leading to an excitatory action of GABA and facilitate recurrent seizures.

Unveiling the mode of action of BDNF in the development and functioning of the GABAergic network is a promising quest for developing new cures of a number of neurological diseases. BDNF influences the development and functioning of the GABAergic network which in turn controls BDNF levels. As a result of this interaction, impairment of one of the two systems will most disturb the other, and since each of them is fundamental to normal CNS functioning, this will potentially lead to a host of neurological conditions. As of today, there is hope that investigation of the molecular pathways mediating the trophic action of BDNF may provide new insights into the normal development of the GABAergic network, providing new therapeutic strategies to improve the symptoms in a broad spectrum of GABA-related pathologies.

Author Contributions

The review was conceptualized, written and edited by each of the authors. CP was the supervisor.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Yesser Belgacem-Tellier and Karen Hsu for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by The National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM), the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), the National Agency for Research (ANR, grant number R07066AS 2008–2011 CP, IM and J-LG).

References

- Aguado F., Carmona M. A., Pozas E., Aguiló A., Martínez-Guijarro F. J., Alcantara S., et al. (2003). BDNF regulates spontaneous correlated activity at early developmental stages by increasing synaptogenesis and expression of the K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2. Development 130, 1267–1280. 10.1242/dev.00351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronica E., Boer K., Redeker S., Spliet W. G. M., van Rijen P. C., Troost D., et al. (2007). Differential expression patterns of chloride transporters, Na+-K+-2Cl−-cotransporter and K+-Cl−-cotransporter, in epilepsy-associated malformations of cortical development. Neuroscience 145, 185–196. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee A., Rikhye R. V., Breton-Provencher V., Tang X., Li C., Li K., et al. (2016). Jointly reduced inhibition and excitation underlies circuit-wide changes in cortical processing in Rett syndrome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 113, E7287–E7296. 10.1073/pnas.1615330113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmashenko G., Hefft S., Aertsen A., Kirschstein T., Köhling R. (2011). Positive shifts of the GABAA receptor reversal potential due to altered chloride homeostasis is widespread after status epilepticus. Epilepsia 52, 1570–1578. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03247.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-Horner C. L., Dohi A., Nguyen Q., Dillon G. H., Singh M. (2006). ERK/MAPK pathway regulates GABAA receptors. J. Neurobiol. 66, 1467–1474. 10.1002/neu.20327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Cherubini E., Corradetti R., Gaiarsa J. L. (1989). Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J. Physiol. 416, 303–325. 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Gaiarsa J.-L., Tyzio R., Khazipov R. (2007). GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol. Rev. 87, 1215–1284. 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ari Y., Holmes G. L. (2005). The multiple facets of γ-aminobutyric acid dysfunction in epilepsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 18, 141–145. 10.1097/01.wco.0000162855.75391.6a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berninger B., Marty S., Zafra F., da Penha Berzaghi M., Thoenen H., Lindholm D. (1995). GABAergic stimulation switches from enhancing to repressing BDNF expression in rat hippocampal neurons during maturation in vitro. Development 121, 2327–2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder D. K., Croll S. D., Gall C. M., Scharfman H. E. (2001). BDNF and epilepsy: too much of a good thing? Trends Neurosci. 24, 47–53. 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01682-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulenguez P., Liabeuf S., Bos R., Bras H., Jean-xavier C., Brocard C., et al. (2010). Down-regulation of the potassium-chloride cotransporter KCC2 contributes to spasticity after spinal cord injury. Nat. Med. 16, 302–307. 10.1038/nm.2107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovolenta R., Zucchini S., Paradiso B., Rodi D., Merigo F., Navarro Mora G., et al. (2010). Hippocampal FGF-2 and BDNF overexpression attenuates epileptogenesis-associated neuroinflammation and reduces spontaneous recurrent seizures. J. Neuroinflammation 7:81. 10.1186/1742-2094-7-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady M. L., Pilli J., Lorenz-Guertin J. M., Das S., Moon C. E., Graff N., et al. (2018). Depolarizing, inhibitory GABA type a receptor activity regulates GABAergic synapse plasticity via ERK and BDNF signaling. Neuropharmacology 128, 324–339. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P., Perez J., Barale F., Schettini G., Soares J. C. (2003). GABAergic dysfunction in mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 8, 721–737, 715. 10.1038/sj.mp.4001395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünig I., Penschuck S., Berninger B., Benson J., Fritschy J. M. (2001). BDNF reduces miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents by rapid downregulation of GABAA receptor surface expression. Eur. J. Neurosci. 13, 1320–1328. 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01506.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlino D., Leone E., Di Cola F., Baj G., Marin R., Dinelli G., et al. (2011). Low serum truncated-BDNF isoform correlates with higher cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45, 273–279. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona M. A., Pozas E., Martínez A., Espinosa-Parrilla J. F., Soriano E., Aguado F. (2006). Age-dependent spontaneous hyperexcitability and impairment of GABAergic function in the hippocampus of mice lacking trkB. Cereb. Cortex 16, 47–63. 10.1093/cercor/bhi083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charych E. I., Liu F., Moss S. J., Brandon N. J. (2009). GABAA receptors and their associated proteins: implications in the etiology and treatment of schizophrenia and related disorders. Neuropharmacology 57, 481–495. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2009.07.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyaya B., Di Cristo G., Wu C. Z., Knott G., Kuhlman S., Fu Y., et al. (2007). GAD67-mediated GABA synthesis and signaling regulate inhibitory synaptic innervation in the visual cortex. Neuron 54, 889–903. 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. I., Zang K., Masliah E., Reichardt L. F. (2016). Glutamatergic axon-derived BDNF controls GABAergic synaptic differentiation in the cerebellum. Sci. Rep. 6:20201. 10.1038/srep20201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q., Yeh H. H. (2003). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor attenuates mouse cerebellar granule cell GABAA receptor-mediated responses via postsynaptic mechanisms. J. Physiol. 548, 711–721. 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.037846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I., Navarro V., Clemenceau S., Baulac M., Miles R. (2002). On the origin of interictal activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy in vitro. Science 298, 1418–1421. 10.1126/science.1076510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Cory S., Kidane A. H., Shirkey N. J., Marshak S. (2010). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and the development of structural neuronal connectivity. Dev. Neurobiol. 70, 271–288. 10.1002/dneu.20774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull J. A. M., Beggs S., Boudreau D., Boivin D., Tsuda M., Inoue K., et al. (2005). BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature 438, 1017–1021. 10.1038/nature04223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull J. A. M., Boudreau D., Bachand K., Prescott S. A., Nault F., Sík A., et al. (2003). Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature 424, 938–942. 10.1038/nature01868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargaei Z., Bang J. Y., Mahadevan V., Khademullah C. S., Bedard S., Parfitt G. M., et al. (2018). Restoring GABAergic inhibition rescues memory deficits in a Huntington’s disease mouse model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 115, E1618–E1626. 10.1073/pnas.1716871115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deidda G., Parrini M., Naskar S., Bozarth I. F., Contestabile A., Cancedda L. (2015). Reversing excitatory GABAAR signaling restores synaptic plasticity and memory in a mouse model of down syndrome. Nat. Med. 21, 318–326. 10.1038/nm.3827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty K. D., Milner T. A. (1999). p75NTR immunoreactivity in the rat dentate gyrus is mostly within presynaptic profiles but is also found in some astrocytic and postsynaptic profiles. J. Comp. Neurol. 407, 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernfors P., Bengzon J., Kokaia Z., Persson H., Lindvall O. (1991). Increased levels of messenger RNAs for neurotrophic factors in the brain during kindling epileptogenesis. Neuron 7, 165–176. 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90084-d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino H., Kuczewski N., Diabira D., Ferrand N., Pangalos M. N., Porcher C., et al. (2009). GABAB receptor activation triggers BDNF release and promotes the maturation of GABAergic synapses. J. Neurosci. 29, 11650–11661. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3587-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer M. J. M., Scheler G., Stefan H. (2005). Utilization of magnetoencephalography results to obtain favourable outcomes in epilepsy surgery. Brain 128, 153–157. 10.1093/brain/awh333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaiarsa J.-L., Kuczewski N., Porcher C. (2011). Contribution of metabotropic GABAB receptors to neuronal network construction. Pharmacol. Ther. 132, 170–179. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguly K., Schinder A. F., Wong S. T., Poo M. (2001). GABA itself promotes the developmental switch of neuronal GABAergic responses from excitation to inhibition. Cell 105, 521–532. 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00341-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia K. L. P., Yu G., Nicolini C., Michalski B., Garzon D. J., Chiu V. S., et al. (2012). Altered balance of proteolytic isoforms of pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor in autism. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 71, 289–297. 10.1097/nen.0b013e31824b27e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg E. M., Coulter D. A. (2013). Mechanisms of epileptogenesis: a convergence on neural circuit dysfunction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14, 337–349. 10.1038/nrn3482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González M. I. (2014). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor promotes gephyrin protein expression and GABAA receptor clustering in immature cultured hippocampal cells. Neurochem. Int. 72, 14–21. 10.1016/j.neuint.2014.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottmann K., Mittmann T., Lessmann V. (2009). BDNF signaling in the formation, maturation and plasticity of glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses. Exp. Brain Res. 199, 203–234. 10.1007/s00221-009-1994-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella J., Nelson N., Nelson H., Czyzyk L., Keynan S., Miedel M. C., et al. (1990). Cloning and expression of a rat brain GABA transporter. Science 249, 1303–1306. 10.1126/science.1975955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini P., Ben-Ari Y., Gaïarsa J.-L. (2005). Endogenous neurotrophins are required for the induction of GABAergic long-term potentiation in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 25, 5796–5802. 10.1523/jneurosci.0824-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.-P., Kotloski R., Nef S., Luikart B. W., Parada L. F., McNamara J. O. (2004). Conditional deletion of TrkB but not BDNF prevents epileptogenesis in the kindling model. Neuron 43, 31–42. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X. P., Pan E., Sciarretta C., Minichiello L., McNamara J. O. (2010). Disruption of TrkB-mediated phospholipase Cγ signaling inhibits limbic epileptogenesis. J. Neurosci. 30, 6188–6196. 10.1523/jneurosci.5821-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M. M., Nieto-Gonzalez J. L., Vardya I., Vaegter C. B., Nykjaer A., Jensen K. (2009). Mature BDNF, but not proBDNF, reduces excitability of fast-spiking interneurons in mouse dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 29, 12412–12418. 10.1523/jneurosci.2978-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong E. J., McCord A. E., Greenberg M. E. (2008). A biological function for the neuronal activity-dependent component of BDNF transcription in the development of cortical inhibition. Neuron 60, 610–624. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberfeld G., Wittner L., Clemenceau S., Baulac M., Kaila K., Miles R., et al. (2007). Perturbed chloride homeostasis and GABAergic signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 27, 9866–9873. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y., Lu Y., Yang F., Shen W., Tang T. T., Feng L., et al. (2010). Acute and gradual increases in BDNF concentration elicit distinct signaling and functions in hippocampal neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 302–309. 10.1038/nn.2505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Huguenard J. R., Prince D. A. (2005). Impaired Cl− extrusion in layer V pyramidal neurons of chronically injured epileptogenic neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 2117–2126. 10.1152/jn.00728.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic J. N., Thomas P., Kittler J. T., Smart T. G., Moss S. J. (2004). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates fast synaptic inhibition by regulating GABAA receptor phosphorylation, activity and cell-surface stability. J. Neurosci. 24, 522–530. 10.1523/jneurosci.3606-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle K. T. K. T., Merner N. D. N. D., Friedel P., Silayeva L., Liang B., Khanna A., et al. (2014). Genetically encoded impairment of neuronal KCC2 cotransporter function in human idiopathic generalized epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 15, 766–774. 10.15252/embr.201438840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazipov R., Khalilov I., Tyzio R., Morozova E., Ben-Ari Y., Holmes G. L. (2004). Developmental changes in GABAergic actions and seizure susceptibility in the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 19, 590–600. 10.1111/j.0953-816x.2003.03152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kittler J. T., Delmas P., Jovanovic J. N., Brown D. A., Smart T. G., Moss S. J. (2000). Constitutive endocytosis of GABAA receptors by an association with the adaptin AP2 complex modulates inhibitory synaptic currents in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 20, 7972–7977. 10.1523/jneurosci.20-21-07972.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolarow R., Brigadski T., Lessmann V. (2007). Postsynaptic secretion of BDNF and NT-3 from hippocampal neurons depends on calcium calmodulin kinase II signaling and proceeds via delayed fusion pore opening. J. Neurosci. 27, 10350–10364. 10.1523/jneurosci.0692-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kourdougli N., Pellegrino C., Renko J.-M., Khirug S., Chazal G., Kukko-Lukjanov T.-K., et al. (2017). Depolarizing γ-aminobutyric acid contributes to glutamatergic network rewiring in epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 81, 251–265. 10.1002/ana.24870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalchuk Y., Holthoff K., Konnerth A. (2004). Neurotrophin action on a rapid timescale. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 14, 558–563. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama R., Yamada M. K., Fujisawa S., Katoh-Semba R., Matsuki N., Ikegaya Y. (2004). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces hyperexcitable reentrant circuits in the dentate gyrus. J. Neurosci. 24, 7215–7224. 10.1523/jneurosci.2045-04.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczewski N., Fuchs C., Ferrand N., Jovanovic J. N., Gaiarsa J.-L., Porcher C. (2011). Mechanism of GABAB receptor-induced BDNF secretion and promotion of GABAA receptor membrane expression. J. Neurochem. 118, 533–545. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzirian M. S., Paradis S. (2011). Emerging themes in GABAergic synapse development. Prog. Neurobiol. 95, 68–87. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langlois A., Diabira D., Ferrand N., Porcher C., Gaiarsa J.-L. (2013). NMDA-dependent switch of proBDNF actions on developing GABAergic synapses. Cereb. Cortex 23, 1085–1096. 10.1093/cercor/bhs071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law R. M., Stafford A., Quick M. W. (2000). Functional regulation of γ-aminobutyric acid transporters by direct tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23986–23991. 10.1074/jbc.m910283199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessmann V., Brigadski T. (2009). Mechanisms, locations and kinetics of synaptic BDNF secretion: an update. Neurosci. Res. 65, 11–22. 10.1016/j.neures.2009.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. A., Hashimoto T., Volk D. W. (2005). Cortical inhibitory neurons and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 312–324. 10.1038/nrn1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B., Pang P. T., Woo N. H. (2005). The yin and yang of neurotrophin action. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 603–614. 10.1038/nrn1726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A., Uvarov P., Soni S., Thomas-Crusells J., Airaksinen M. S., Rivera C. (2011). Early growth response 4 mediates BDNF induction of potassium chloride cotransporter 2 transcription. J. Neurosci. 31, 644–649. 10.1523/jneurosci.2006-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund I. V., Hu Y., Raol Y. H., Benham R. S., Faris R., Russek S. J., et al. (2008). BDNF selectively regulates GABAA receptor transcription by activation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Sci. Signal. 1:ra9. 10.1126/scisignal.1162396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menshanov P. N., Lanshakov D. A., Dygalo N. N. (2015). proBDNF is a major product of bdnf gene expressed in the perinatal rat cortex. Physiol. Res. 64, 925–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi Y., Ishibashi H., Nabekura J. (2003). The action of BDNF on GABAA currents changes from potentiating to suppressing during maturation of rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J. Physiol. 548, 703–709. 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore Y. E., Kelley M. R., Brandon N. J., Deeb T. Z., Moss S. J. (2017). Seizing control of KCC2: a new therapeutic target for epilepsy. Trends Neurosci. 40, 555–571. 10.1016/j.tins.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mou L., Dias B. G., Gosnell H., Ressler K. J. (2013). Gephyrin plays a key role in BDNF-dependent regulation of amygdala surface GABAARs. Neuroscience 255, 33–44. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.09.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller T. M., Remedies C. E., Haroutunian V., Meador-Woodruff J. H. (2015). Abnormal subcellular localization of GABAA receptor subunits in schizophrenia brain. Transl. Psychiatry 5:e612. 10.1038/tp.2015.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munakata M., Watanabe M., Otsuki T., Nakama H., Arima K., Itoh M., et al. (2007). Altered distribution of KCC2 in cortical dysplasia in patients with intractable epilepsy. Epilepsia 48, 837–844. 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2006.00954.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagappan G., Zaitsev E., Senatorov V. V., Yang J., Hempstead B. L., Lu B. (2009). Control of extracellular cleavage of ProBDNF by high frequency neuronal activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 1267–1272. 10.1073/pnas.0807322106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Darnieder L. M., Deeb T. Z., Moss S. J. (2015). Regulation of GABAARs by phosphorylation. Adv. Pharmacol. 72, 97–146. 10.1016/bs.apha.2014.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K., Gao X.-B., Van Den Pol A. N. (2002). Excitatory actions of GABA increase BDNF expression via a MAPK-CREB-dependent mechanism–a positive feedback circuit in developing neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 88, 1005–1015. 10.1152/jn.2002.88.2.1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso B., Marconi P., Zucchini S., Berto E., Binaschi A., Bozac A., et al. (2009). Localized delivery of fibroblast growth factor-2 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor reduces spontaneous seizures in an epilepsy model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 7191–7196. 10.1073/pnas.0810710106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porcher C., Hatchett C., Longbottom R. E., McAinch K., Sihra T. S., Moss S. J., et al. (2011). Positive feedback regulation between gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptor signaling and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release in developing neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 21667–21677. 10.1074/jbc.M110.201582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reibel S., Larmet Y., Lê B. T., Carnahan J., Marescaux C., Depaulis A. (2000). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor delays hippocampal kindling in the rat. Neuroscience 100, 777–788. 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00351-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffault B., Kourdougli N., Dumon C., Ferrand N., Buhler E., Schaller F., et al. (2018). Pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor (proBDNF)-mediated p75NTR activation promotes depolarizing actions of GABA and increases susceptibility to epileptic seizures. Cereb. Cortex 28, 510–527. 10.1093/cercor/bhw385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riffault B., Medina I., Dumon C., Thalman C., Ferrand N., Friedel P., et al. (2014). Pro-brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission by activating endocytosis and repression of GABAA receptors. J. Neurosci. 34, 13516–13534. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2069-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C., Li H., Thomas-Crusells J., Lahtinen H., Viitanen T., Nanobashvili A., et al. (2002). BDNF-induced TrkB activation down-regulates the K+-Cl− cotransporter KCC2 and impairs neuronal Cl− extrusion. J. Cell Biol. 159, 747–752. 10.1083/jcb.200209011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C., Voipio J., Payne J. A., Ruusuvuori E., Lahtinen H., Lamsa K., et al. (1999). The K+/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature 397, 251–255. 10.1038/16697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera C., Voipio J., Thomas-Crusells J., Li H., Emri Z., Sipilä S., et al. (2004). Mechanism of activity-dependent downregulation of the neuron-specific K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. J. Neurosci. 24, 4683–4691. 10.1523/jneurosci.5265-03.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata K., Woo N. H., Martinowich K., Greene J. S., Schloesser R. J., Shen L., et al. (2009). Critical role of promoter IV-driven BDNF transcription in GABAergic transmission and synaptic plasticity in the prefrontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 106, 5942–5947. 10.1073/pnas.0811431106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanacora G., Mason G. F., Rothman D. L., Behar K. L., Hyder F., Petroff O. A., et al. (1999). Reduced cortical gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in depressed patients determined by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 1043–1047. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.11.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Huertas C., Rico B. (2011). CREB-dependent regulation of GAD65 transcription by BDNF/TrkB in cortical interneurons. Cereb. Cortex 21, 777–788. 10.1093/cercor/bhQ170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sernagor E., Chabrol F., Bony G., Cancedda L. (2010). GABAergic control of neurite outgrowth and remodeling during development and adult neurogenesis: general rules and differences in diverse systems. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 4:11. 10.3389/fncel.2010.00011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu-Okabe C., Tanaka M., Matsuda K., Mihara T., Okabe A., Sato K., et al. (2011). KCC2 was downregulated in small neurons localized in epileptogenic human focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsy Res. 93, 177–184. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2010.12.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulga A., Thomas-Crusells J., Sigl T., Blaesse A., Mestres P., Meyer M., et al. (2008). Posttraumatic GABAA-mediated [Ca2+]i increase is essential for the induction of brain-derived neurotrophic factor-dependent survival of mature central neurons. J. Neurosci. 28, 6996–7005. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5268-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song W., Volosin M., Cragnolini A. B., Hempstead B. L., Friedman W. J. (2010). ProNGF induces PTEN via p75NTR to suppress Trk-mediated survival signaling in brain neurons. J. Neurosci. 30, 15608–15615. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2581-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. X., Cruz Del Angel Y., Gonzalez M. I., Carrel A. J., Carlsen J., Lam P. M., et al. (2016). Rapid Increases in proBDNF after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice are associated with reduced proBDNF cleavage machinery. eNeuro 3:ENEURO.0020-15.2016. 10.1523/ENEURO.0020-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyagarajan S. K., Fritschy J. M. (2010). GABAA receptors, gephyrin and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. J. Physiol. 588, 101–106. 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio R., Ivanov A., Bernard C., Holmes G. L., Ben-Ari Y., Khazipov R. (2003). Membrane potential of CA3 hippocampal pyramidal cells during postnatal development. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 2964–2972. 10.1152/jn.00172.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyzio R., Nardou R., Ferrari D. C., Tsintsadze T., Shahrokhi A., Eftekhari S., et al. (2014). Oxytocin-mediated GABA inhibition during delivery attenuates autism pathogenesis in rodent offspring. Science 343, 675–679. 10.1126/science.1247190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsain N., Nuñez N., Anastasía A., Mascó D. H. (2008). Status epilepticus induces a TrkB to p75 neurotrophin receptor switch and increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor interaction with p75 neurotrophin receptor: an initial event in neuronal injury induction. Neuroscience 154, 978–993. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan N. T., Mohan M. L., Gupta M. K., Hussain A. K., Naga Prasad S. V. (2011). Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A activity by PI3Kγ regulates β-adrenergic receptor function. Mol. Cell 41, 636–648. 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz S. H., Cristóvão-Ferreira S., Ribeiro J. A., Sebastião A. M. (2008). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits GABA uptake by the rat hippocampal nerve terminals. Brain Res. 1219, 19–25. 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaz S. H., Jørgensen T. N., Cristóvão-Ferreira S., Duflot S., Ribeiro J. A., Gether U., et al. (2011). Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) enhances GABA transport by modulating the trafficking of GABA transporter-1 (GAT-1) from the plasma membrane of rat cortical astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 40464–40476. 10.1074/jbc.M111.232009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachos A., Reddy-Alla S., Papadopoulos T., Deller T., Betz H. (2013). Homeostatic regulation of gephyrin scaffolds and synaptic strength at mature hippocampal GABAergic postsynapses. Cereb. Cortex 23, 2700–2711. 10.1093/cercor/bhs260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wake H., Watanabe M., Moorhouse A. J., Kanematsu T., Horibe S., Matsukawa N., et al. (2007). Early changes in KCC2 phosphorylation in response to neuronal stress result in functional downregulation. J. Neurosci. 27, 1642–1650. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3104-06.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. D., Kriegstein A. R. (2008). GABA regulates excitatory synapse formation in the neocortex via NMDA receptor activation. J. Neurosci. 28, 5547–5558. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5599-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth T. L., Quick M. W. (2001). Substrate-induced regulation of γ-aminobutyric acid transporter trafficking requires tyrosine phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42932–42937. 10.1074/jbc.M107638200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winnubst J., Cheyne J. E., Niculescu D., Lohmann C. (2015). Spontaneous activity drives local synaptic plasticity in vivo. Neuron 87, 399–410. 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.06.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C., Zhao M., Poo M., Zhang X. (2008). GABA(B) receptor activation mediates frequency-dependent plasticity of developing GABAergic synapses. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1410–1418. 10.1038/nn.2215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Harte-Hargrove L. C., Siao C.-J., Marinic T., Clarke R., Ma Q., et al. (2014). proBDNF negatively regulates neuronal remodeling, synaptic transmission and synaptic plasticity in hippocampus. Cell Rep. 7, 796–806. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Siao C.-J., Nagappan G., Marinic T., Jing D., McGrath K., et al. (2009). Neuronal release of proBDNF. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 113–115. 10.1038/nn.2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshii A., Constantine-Paton M. (2010). Postsynaptic BDNF-TrkB signaling in synapse maturation, plasticity and disease. Dev. Neurobiol. 70, 304–322. 10.1002/dneu.20765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q., Yang F., Xiao Y., Tan S., Husain N., Ren M., et al. (2016). Regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor exocytosis and gamma-aminobutyric acidergic interneuron synapse by the schizophrenia susceptibility gene dysbindin-1. Biol. Psychiatry 80, 312–322. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]