Abstract

Significance: A growing body of clinical and experimental evidence has challenged the traditional understanding that only the adaptive immune system can mount immunological memory. Recent findings describe the adaptive characteristics of the innate immune system, underscored by its ability to remember antecedent foreign encounters and respond in a nonspecific sensitized manner to reinfection. This has been termed trained innate immunity. Although beneficial in the context of recurrent infections, this might actually contribute to chronic immune-mediated diseases, such as atherosclerosis.

Recent Advances: In line with its proposed role in sustaining cellular memories, epigenetic reprogramming has emerged as a critical determinant of trained immunity. Recent technological and computational advances that improve unbiased acquisition of epigenomic profiles have significantly enhanced our appreciation for the complexities of chromatin architecture in the contexts of diverse immunological challenges.

Critical Issues: Key to resolving the distinct chromatin signatures of innate immune memory is a comprehensive understanding of the precise physiological targets of regulatory proteins that recognize, deposit, and remove chemical modifications from chromatin as well as other gene-regulating factors. Drawing from a rapidly expanding compendium of experimental and clinical studies, this review details a current perspective of the epigenetic pathways that support the adapted phenotypes of monocytes and macrophages.

Future Directions: We explore future strategies that are aimed at exploiting the mechanism of trained immunity to improve the prevention and treatment of infections and immune-mediated chronic disorders.

Keywords: : epigenetics, trained immunity, monocyte, macrophage, memory, innate immunity

Introduction

Innate immunity is the first in line and one of the most important components of host defense. Recently, a paradigm shift has occurred through the discovery of memory properties in innate immune cells (91, 106). In contrast to adaptive immune responses, the innate immune system has traditionally been viewed as primitive and generic, lacking the ability to differentiate individual species of pathogen or the quantity of encounters. However, an unequivocal body of clinical and experimental evidence now argues for a shift in our understanding of the innate immune system (91), underscored by its capacity to confer broad immunological protection.

Innate immune cells, such as monocytes/macrophages and natural killer cells (NK-cells), can recollect a previous foreign encounter and, therefore, mount immunological memory. This biological process of innate immune memory has been called trained immunity (92), and it is illustrated by the observation that stimulation of innate immune cells with a pathogen augments the subsequent immune response to similar or unrelated immunological stimuli (66, 106). The enhanced immune response is associated with a profound change in the intracellular metabolism and epigenetic regulation at the level of histone modifications (4, 115).

Besides the primary function of the innate immune system to mediate first-line host defense against a broad spectrum of pathogens and to regulate tissue homeostasis, recent studies have argued that functional reprogramming of innate immune cells may also play an important role in immune-mediated diseases (9, 134, 135). Monocytes and macrophages are involved in the pathogenesis of many highly prevalent chronic disorders, including insulin resistance (obesity as well as diabetes mellitus), tumor growth, and autoimmune or autoinflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease. Further, innate immune cells play a central role in the development of atherosclerosis, a chronic low-grade inflammatory condition of the vessel wall, with macrophages being the most abundant immune cells in the atherosclerotic lesion that regulates plaque progression and stability (28, 88). The involvement of innate immune cells in atherosclerosis, as well as in other immune-mediated diseases, illustrates the pivotal role of the innate immune system in common inflammatory disorders with a high medical and economic burden.

To exploit the concept of trained immunity to improve vaccination strategies or prevent atherosclerosis and other chronic inflammatory diseases, it is crucial to unravel the underlying mechanism. This review provides a comprehensive state-of-the-art framework on the intracellular events that coordinate trained immunity, namely intracellular metabolism and epigenetic rewiring of gene transcription. Understanding the specific immunometabolic pathways and epigenetic signatures of innate immune memory is crucial for the development of novel therapeutic approaches for infectious and chronic inflammatory diseases.

Memories Are Not Just About the Past

Unlike acquired immunity, which primes the adaptive immune system for an enhanced response to subsequent encounters with the same pathogen, innate immune memory instructs an altered future response that is nonspecific. Nonspecific immunological memory has long been known to occur in plants (33) and invertebrate animals (103, 105, 114), both of which lack an adaptive immune system, suggesting an ancient biological process (93). The first indication of the potential importance of this phenomenon for vertebrate host defense came from the broad protection conferred against unrelated diseases by pioneering vaccination programs. As early as the 1930s, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), one of the world's most administered vaccines against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, was found to greatly improve the survival of infants beyond the tuberculosis mortality burden (3, 20, 38, 75, 113, 129). The nonspecific beneficial effects of BCG vaccination were further demonstrated by randomized clinical trials reporting reduced mortality from various infections in low-birth-weight children in Africa (1, 13).

Perhaps the most striking example in humans supporting a nonspecific training of the immune system was a series of studies revealing a heightened ex vivo immune response to the fungal pathogen Candida albicans in human volunteers recently vaccinated with BCG (66), consistent with previous reports of BCG-mediated protection against disseminated candidiasis in experimental animals (15, 130). The enhanced immune response was detected not only for the lymphocyte-derived IFNγ but also for monocyte-derived TNFα and IL6. Further, the heterologous protection conferred by BCG training was replicated in mice with known deficiencies in adaptive immune responses (66).

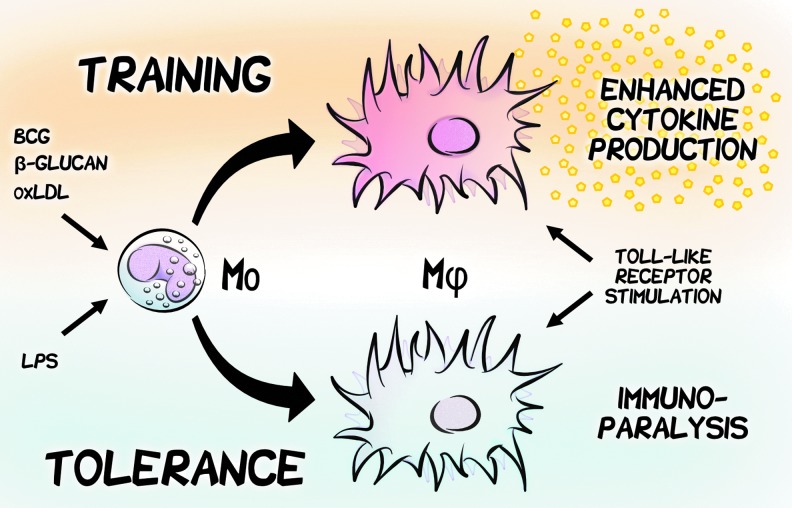

Appreciation for the importance of innate immune memory has since expanded beyond vaccines to include various microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). For example, protection against lethal C. albicans infection in mice by prior administration of a nonlethal dose is dependent on the enhanced proinflammatory and microbicidal function of trained monocytes and macrophages (106). Similar effects are observed for human primary monocytes trained in vitro with the C. albicans cell wall component β-1,3-(d)-glucan (β-glucan), which show an enhanced secondary response to stimulation with various Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists such as the bacterial lipoprotein Pam(3)CSK4 (TLR2) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) endotoxin (TLR4). This in vitro model (8) exemplifies the main properties of trained immunity: Infection with one pathogen augments the subsequent immune response to unrelated immunological stimuli. In striking contrast, primary stimulation by a high dose of LPS has been long known to induce a persistent refractory state with reduced capacity to respond to restimulation by a process called LPS-induced tolerance (40). Conceptually also a form of innate immune memory, inappropriately activated immune tolerance is responsible for the immunoparalysis induced by Gram-negative sepsis (36, 142). The adapted phenotypes induced in vitro are highly reproducible across cells prepared from unrelated donors and indicative of a specific program of cell differentiation (115). The distinct and opposing functional programs of training and tolerance provide a useful contrast for understanding the extremes of a spectrum of adaptive characteristics that can be acquired by the innate immune system in response to diverse immunological challenges (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Innate immune memory underlies a spectrum of adaptive characteristics that are acquired in response to diverse immunological challenges. Monocyte (Mo) memories of past encounters with microbial and nonmicrobial products can elicit vastly different responses to future exposures on differentiation to macrophages (Mφ). Trained immunity, induced by BCG, β-glucan, or oxLDL, defines an immunological memory that calibrates an enhanced non-specific response to subsequent infections by enhancing the inflammatory and antimicrobial properties of innate immune cells. In contrast, primary stimulation with LPS induces a persistent refractory state known as tolerance, with a markedly reduced capacity to respond to restimulation. β-glucan, β-1,3-(d)-glucan; BCG, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein.

Trained immunity is a double-edged sword

Despite its benefits in the context of infections, long-term activation of the innate immune system may play a maladaptive role in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases (59). One example of such a disease is atherosclerosis, the result of a chronic, low-grade vascular inflammation in which the immune system plays a central role. A complex interplay between endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, and circulating immune cells creates a proinflammatory microenvironment in the vascular wall supporting the formation of an atherosclerotic plaque (25). In this process, the most abundant inflammatory cells are monocytes and macrophages. By migrating into the vessel wall, monocytes determine early plaque development, and after differentiation into macrophages they ingest lipid particles to become foam cells (59). Moreover, local damage-associated molecular patterns such as modified low-density lipoprotein (LDL) particles and proteoglycans stimulate membrane-bound receptors such as TLR2 and TLR4 (154). The subsequent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines further fuels the proinflammatory environment that is associated with the development, progression, and (in)stability of atherosclerotic plaques (59).

Training of human primary monocytes with MAMPs induces a marked elevation in the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines that are strongly implicated in the development and progression of atherosclerotic plaques (135). Vaccination with BCG accelerates atherosclerosis in rabbits fed a cholesterol-rich diet (69). In contrast, other studies have reported a protective effect in atherosclerosis-prone mice (100, 131), which might be due to its cholesterol-lowering action. Perhaps most compelling are recent observations that nonmicrobial products, including lipoproteins that are known drivers of cardiovascular disease, can also induce trained immunity (Table 1). In vitro stimulation of human primary monocytes with a low concentration of oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL) programs a sustained atherogenic macrophage phenotype that is characterized by elevated expression of CD36 and SR-A scavenger receptors leading to enhanced foam cell formation, as well as amplified proinflammatory cytokine production and matrix metalloprotease expression (9). Similarly, brief exposure to lipoprotein(a) induces a proinflammatory phenotype in monocytes that are restimulated in vitro (134). Indeed, circulating monocytes isolated from patients with symptomatic atherosclerosis exhibit a proinflammatory phenotype compared with cells isolated from healthy controls (10). This effect was also observed in patients with an increased cardiovascular risk due to elevated circulating levels of lipoprotein(a) (134).

Table 1.

Inducers of Innate Immune Memory in Monocytes

| Primary stimulus | Type of immune response | Cellular metabolism in trained cells | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCG | Trained immunity | ↑ Aerobic glycolysis | Kleinnijenhuis et al. (66) |

| ↑ Oxidative phosphorylation | Arts et al. (4) | ||

| ↑ Glutamine metabolism | |||

| Candida albicans | Trained immunity | Quintin et al. (106) | |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae via fungal chitin | Trained immunity | Rizzetto et al. (111) | |

| β-1,3-(d)-glucan | Trained immunity | ↑ Aerobic glycolysis | Cheng et al. (24) |

| ↓ Oxidative phosphorylation | Saeed et al. (115) Arts et al. (5) |

||

| oxLDL | Trained immunity | ↑ Glycolysis | Bekkering et al. (9) |

| Lipoprotein(a) | Trained immunity | Van der Valk et al. (134) | |

| Fumarate | Trained immunity | Arts et al. (5) | |

| TLR-agonists | |||

| TLR 4: LPS | Trained immunity/tolerance | Novakovic et al. (97) | |

| TLR 2: Pam3CSK4 | Immunotolerance | ||

| TLR 3: poly(I:C) | Trained immunity/tolerance | Foster et al. (40) Ifrim et al. (50) |

|

| TLR 5: flagellin | Trained immunity/tolerance | Lachmandas et al. (68) | |

| Cytosolic receptors | |||

| NOD2 (muramyl dipeptide, MDP) | Trained immunity | Ifrim et al. (50) | |

| NOD1 (l-Ala-γ-d-Glu-mDAP, Tri-DAP) | Trained immunity | ||

| Cytokines/chemokines | |||

| GM-CSF, IL-3 | Trained immunity | Borriello et al. (16) | |

| IFNy | Immune priming | Hoeksema et al. (47) | |

BCG, Bacillus Calmette–Guérin; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; oxLDL, oxidized low-density lipoprotein; TLR, Toll-like receptor.

These findings convey the concept that trained immunity is a biological process with broad implications for cardiovascular disease (59). Such a model implies that monocytes are stimulated by environmental signals in the circulation that could induce epigenetic reprogramming, thereby increasing their responsiveness to secondary stimulation, for instance within the arterial wall or atherosclerotic plaque. The ability for macrophages to adopt unique properties as a function of their microenvironment raises important considerations for macrophage populations in atherosclerotic lesions that are hypoxic, as well as rupture-prone versus stable plaques. Further, accelerated atherosclerosis remains the principal cause of morbidity and premature mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus (81), and a role for trained immunity in diabetic versus normoglycemic environments warrants exploration (59, 135). Several other factors associated with metabolic disease such as free fatty acids, uric acid, and advanced glycation end-products elicit inflammatory responses in monocytes via pattern recognition receptor stimulation, raising the unexplored possibility that they too could induce functional reprogramming and innate immune memory in the context of cardiovascular complications (30, 135).

Cellular metabolism determines the phenotype of innate immune cells

The extensive range of physiological macrophage functions in host defense and maintenance of tissue homeostasis necessitates a broad spectrum of precisely regulated states of macrophage activation. Although it has long been appreciated that changes in oxygen and glucose consumption accommodate the metabolic requirements of activated macrophages, the importance of intracellular metabolism for shaping the immune response has only recently emerged (98). Moreover, engagement of distinct metabolic pathways not only follows energy requirements but also distinguishes and supports discrete macrophage phenotypes. This metabolic reprogramming is best exemplified by the polarization of classically activated (M1 or M[IFNγ]) and alternatively activated (M2 or M[IL-4]) macrophages. Paralleling their respective pro- and anti-inflammatory phenotypes, these subtypes are characterized by distinct arginine metabolism as well as by differences in fatty acid synthesis and usage [recently reviewed by Van den Bossche et al. (133)]. Although glycolytic metabolism is upregulated across both polarized states, activation of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) is only observed in classically activated macrophages, where it supports inflammatory responses by generating amino acids for protein synthesis, nucleotides for proliferation, as well as NADPH for the production of reactive oxygen species that are necessary for phagocytic killing (98).

Though energetically less efficient than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), the relatively rapid expandability of glycolysis allows faster production of ATP to meet cellular requirements (90, 98). In alternatively activated macrophages, these biochemical processes remain coupled: Enhanced glycolytic generation of pyruvate fuels the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and parallels the induction of OXPHOS (132). This contrasts sharply with inflammatory macrophages, which are characterized by impaired OXPHOS and anabolic repurposing of the TCA cycle (98, 133). This metabolic shift is comparable to the Warburg effect characteristic of cancer metabolism that amends tumor cells to hypoxic environments by upregulating glycolytic gene expression via the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF1α) transcription factor (TF) (125, 141). Further, instead of feeding into the TCA cycle to ultimately fuel OXPHOS, pyruvate is fermented to lactate by HIF1α-dependent pathways. A similar process drives the glycolytic switch in inflammatory macrophages despite the availability of oxygen (98, 132).

Cellular metabolism orchestrates innate immune memory

A metabolic switch comparable to that of classically activated macrophages underlies the adapted phenotype induced by β-glucan training. Stimulation of human monocytes with β-glucan induces glycolysis paralleling elevated glucose consumption and increased pyruvate to lactate conversion (24). Moreover, markedly reduced oxygen consumption in β-glucan-trained macrophages indicates a concomitant reduction in OXPHOS (24). Recent studies reported long-term upregulation of glycolytic rate-limiting enzymes in circulating monocytes from individuals vaccinated with BCG and demonstrated that genetic variation in hexokinase 2 and phosphofructokinase modulates induction of trained immunity (4). Contrasting the classical Warburg switch induced by β-glucan, the immunometabolic profile of BCG training is characterized not only by increased glycolysis and lactate production but also by augmented oxygen consumption (4). However, inhibition of the electronic transport chain did not alter the reprogramming of macrophages in BCG training, demonstrating the secondary role of OXPHOS in development of the adapted phenotype (4). By contrast, inhibition of glycolysis with 2-deoxyglucose abrogated BCG training. Further, inhibition of the Akt/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/HIF1α pathway at several stages abolished training by β-glucan and BCG in vitro as well as experimental animals (4, 24). Emphasizing the relevance of this pathway in humans, administration of the antidiabetic drug and indirect mTOR inhibitor metformin decreased the ability for circulating monocytes to mount a trained response ex vivo to β-glucan exposure in healthy individuals (5). Interestingly, the PPP was also found to be upregulated in β-glucan-trained cells. However, evidence so far suggests that the role of the PPP in trained immunity is relatively small, since inhibition of this pathway had no effect on the adapted phenotype (5). The relevance of this metabolic rewiring in the context of atherosclerosis is illustrated by the consistent finding that glycolytic enzymes are upregulated in monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages that are isolated from patients with established atherosclerosis (10, 119).

Despite the metabolic skewing of β-glucan-trained macrophages toward glycolysis, concentrations of the TCA cycle metabolites citrate, succinate, malate, fumarate, and 2-hydroxyglutarate are increased in comparison to naive macrophages (5). This suggested that the TCA cycle was not entirely adjourned and led to the speculation that these specific metabolites were being replenished through glutaminolysis (5). Indeed, increased glutamine metabolism was one of the consistent immunometabolic changes in macrophages trained with β-glucan and BCG (4, 5, 24), and it plays an important role in immune activation (120). Demonstrating the importance of this process, the glutaminase inhibitor BPTES blocked the induction of trained immunity by β-glucan (5) and BCG (4) in vitro and in experimental animal models (5).

Immunometabolic pathways that are important for the functional reprogramming of immune cells extend beyond those involved in glucose metabolism and OXPHOS. Cells trained with β-glucan displayed upregulation of more than half of the genes involved in cholesterol biosythesis, identifying this pathway together with glutaminolysis and glycolysis as one of the most essential for innate immune training (5). Underlining the importance of the cholesterol synthesis pathway even further, treatment with the HMG-CoA-reductase atorvastatin attenuated β-glucan-induced innate immune training in a murine model (5). Since, next to sterols, the essential lipids in the human cell membrane are phospholipids and glycolipids, fatty acid synthesis is also an important pathway in immune cell function (133). Indeed, recent data indicate that inflammatory stimuli such as LPS and cytokines trigger an increase in fatty acid synthesis in macrophages (5). However, in contrast to the abrogation of training when cholesterol synthesis was inhibited, blockade of fatty acid synthesis did not alter the proinflammatory macrophage phenotype induced by β-glucan training (5).

Molecular mechanisms of macrophage memory

For a monocyte, memories of past encounters with microbial products can be truly transformative insofar as they can elicit vastly different future responses to microbial ligands. The gross implication of training or tolerance is a fundamental phenotypic shift involving changes to major metabolic and signaling pathways that facilitate the overall cellular memory. Underlying much of this reprogramming are widespread transcriptional changes associated with metabolic pathways, many of which occur early in the training regimen and precede the adapted phenotype (5).

Because distinct cell types and subtypes of multicellular organisms arise from identical genetic material, gene control and expression are fundamental determinants of differentiation and phenotype. However much remains to be understood about how genetic information is interpreted by individual cells in health and disease. Only when we unravel the DNA strands to appreciate the constituent assembly of chromatin can we begin to recognize the complexity of genome organization and regulation (29).

Chromatin reorganization and innate immune memory

Epigenetic regulation of gene expression

Gene transcription is tightly controlled by the interplay and long-range communication of regulatory events at gene promoters that are proximal to the transcription start site and distal genetic elements called enhancers (21). Accessibility of the DNA to protein TFs and other transcriptional machinery at these regulatory regions is essential for gene expression. The dynamic polymer of DNA and nucleosomal histone proteins known as chromatin facilitates functional compartmentalization of the genome to assemble structurally open, transcriptionally permissive configurations or condensed, repressive domains (57). Since the initial description of the nucleosome particle as the repeating unit of chromatin in 1977 (39), it has become increasingly clear that core nucleosome components are distinguishable by post-translational chemical modification and instructive of chromatin architecture (54, 136).

Histone modifications influence chromatin structure and function

The octameric nucleosome is composed of four core histone proteins: two H3 and H4 homodimers and two H2A/H2B heterodimers, encircled by ∼147 bp of DNA (57). Unstructured N-terminal histone tails that extend from nucleosomes are substrate for post-translational enzymatic modifications, which are cooperatively associated with various states of transcriptional competency and chromatin organization. Amid a vast repertoire of histone modifications (73), acetylation (lysine residues) and methylation (arginine and lysine residues) are the most broadly studied and extensively characterized (Fig. 2). The capacity for histone modifications to designate functional genomic regions and support transcriptional processes significantly amplifies the information potential of the genetic code through mechanisms that modulate chromatin structure and function. Their influence on higher order chromatin accessibility is predominantly facilitated by establishing high-affinity binding sites for the recruitment of chromatin readers: core transcriptional machinery, as well as multisubunit protein complexes that actively restructure, relocate, install, or evict nucleosomes (7).

FIG. 2.

post-translational chemical modifications distinguish between chromatin architecture and transcriptional competency. As the repeating structural unit of chromatin, the nucleosome consists of ∼147 bp of DNA wrapped around an octamer of the core histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. Unstructured N-terminal histone tails are substrate for a variety of posttranslational modifications, which are dynamically written to and erased from specific amino acid residues by specialized enzymes. Shown here are lysine modifications that occur on the tails of H3 and H4 histones. Histone lysine acetylation (orange hexagons) is ubiquitously associated with transcriptional competency and is regulated by the competing activities of HAT and deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes. By contrast, the extent of modification and the position of the modified residue within the histone tail determine the functional readout of histone lysine methylation (purple hexagons). The influence of histone modifications on higher order chromatin accessibility is predominantly facilitated by establishing high-affinity binding sites for the recruitment of protein complexes that actively remodel chromatin. HAT, histone acetyltransferase; HDAC, histone deacetylase; K, lysine; KDM, lysine demethylase; KMT, lysine methyltransferase.

Histone acetylation

Histone acetylation, for example at lysine-9 (H3K9ac) and lysine-27 (H3 histone-lysine-27 acetylation [H3K27ac]) of H3 histones, almost exclusively demarcates transcriptional competency (35). In addition to promoting open chromatin architecture by neutralizing the electrostatic charges on the histone tail and subsequently altering interactions with adjacent nucleosome components (55), acetylated histones are recognized and bound by bromodomains—a structural motif found in specialized chromatin reader proteins (116). Components of many histone acetyltransferase (HAT) complexes harbor bromodomains, which anchor the HAT complexes to acetylated chromatin, allowing them to propagate the acetyl signature to adjacent nucleosomes. Similarly, the bromodomain components of ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complexes are critical for their recruitment to acetylated promoters (55). Another class of histone-acetyl readers known as the bromodomain and extra-terminal (BET) domain-containing family of proteins can regulate gene expression by recruiting TFs as well as chromatin remodeling complexes, and they are increasingly implicated in transcriptional responses that are associated with inflammation (59) and innate immunity (94, 110). Histone modifications are reversible, and their presence on the chromatin is determined by opposing activities of enzymatic writers and erasers. Histone deacetylase (HDAC) enzymes remove acetyl groups from histone tails. Thus, HAT/HDAC activity balance is an important determinant of gene regulation, and it has accordingly emerged as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of various diseases (48, 62, 108, 127).

Histone methylation

Contrasting histone acetylation, the position of the modified residue within the histone tail determines the functional readout of histone methylation. Regulatory elements of repressed genes are often characterized by H3 histones that are methylated at lysine-9 and lysine-27. Conversely, methylation of lysine-4 and lysine-36 is associated with the assembly of transcriptionally permissive chromatin structures. Enzymes that catalyze the transfer (lysine methyltransferase [KMT]) and removal (lysine demethylase [KDM]) of histone methylation demonstrate remarkable specificity toward amino acid positions within the histone tail (51). Further, specific enzymes and complexes determine the extent of individual lysine methylation: Mono- (m1), di- (m2), or trimethylated (m3) histone lysine residues are differentially distributed across chromatin and attributed discrete functional roles in gene regulation. Transcriptional activity positively correlates with the degree of H3 histone-lysine-4 trimethylation (H3K4m3) at gene promoters (11). On the other hand, monomethylation of this residue (H3 histone-lysine-4 monomethylation [H3K4m1]) is a stereotypical feature of enhancers (6). Specialized protein domains, including the chromodomain, tudor domain, malignant brain tumor (MBT) domain, and the plant homeodomain (PHD) finger domain, interpret methylated histones by recruiting various chromatin-remodeling complexes (49, 128).

DNA methylation regulates gene expression

The epigenetic methyl modification is unique in the way that in addition to histones, it can also be written directly to the DNA template. Again, the genomic location of the modification is key to the functional outcome. Postreplicative methylation of the 5-carbon ring of cytosine nucleotides (5-methylcytosine, 5mc) immediately adjacent to guanine residues (5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′ dinucleotide [CpG]) is primarily associated with promoter silencing by two main mechanisms. First, 5mc is mechanistically interpreted by proteins possessing the methyl-CpG-binding domain, which, in turn, recruit transcriptional repressors and chromatin remodeling complexes to establish transcriptionally incompetent chromatin (43). Second, 5mc can physically modulate the binding of TFs to gene regulatory elements (52). On the other hand, 5mc regulates gene splicing, transcriptional elongation, and distal regulatory activities of highly transcribed genes (53). Recent advances in methyl-capture and sequencing technologies have propelled efforts to characterize the DNA methylome across various tissues and disease states, including myeloid differentiation (2, 37), macrophage polarization (140), and cytokine production (151).

Epigenetic cross-talk

The emerging picture of epigenetic regulation is one of remarkable complexity. Protein complexes that read chromatin marks can further recruit certain classes of epigenetic enzymes that cooperatively shape the chromatin landscape. For example, binding of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) via its chromodomain to H3K9m2/3 promotes further repressive methyl marks by enlisting additional KMTs, as well as DNA methyltransferases (41, 124). Together with the activities of short (micro RNAs [miRNAs]) and long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), histone and DNA modifications are collectively defined as epigenetic (80). Through complex interactions with TF networks and other transcriptional machinery, epigenetic modifications collaboratively support the functional exchange between repressed and active states of chromatin to contextualize gene expression.

Chromatin modifications associated with macrophage differentiation and identity

Epigenome-wide variations underlying cellular function and fate are definable at unprecedented resolution by current analytical technologies. To this end, the importance of histone modifications to cellular identity is underscored by the massive reconfiguration of lysine methylation and acetylation patterns at gene regulatory elements during naive monocyte to macrophage differentiation (97, 115). Crucially, the intersection of transcriptome and epigenome profiles revealed a positive correlation between transcriptionally permissive H3 histone modifications and the activity of regulatory elements (115). The most dynamic of these changes were observed for H3 acetylation, with one report describing approximately equal numbers of promoters exhibiting significant enrichment or depletion of H3K27ac (97, 115).

A similar pattern of H3K27ac was observed at distal enhancer regions on differentiation, with 1894 and 2142 regions displaying significant loss and gain of this modification, respectively (115), in accordance with the function of enhancers as key determinants of cell identity, especially within the myeloid lineage. The complements of active enhancer elements in a given tissue are typically co-occupied by combinations of lineage-determining TFs enforcing tissue- and cell-type-specific programs of gene expression (45, 99). Enhancers are distinguished from promoters by their specific enrichment of H3K4m1 (6) and can be classified as active or poised depending on the presence or absence of H3K27ac (45). A comprehensive study of hematopoiesis in mice revealed that a significant proportion of lineage-specific enhancers are established de novo in parallel with H3K4m1 enrichment. Further, clear distinctions were observed across the respective enhancer repertoires after the definitive differentiation step from monocyte to macrophage (71). Enrichment of H3K27ac during human macrophage differentiation is often accompanied by increased deposition of H3K4m1. By contrast, a majority of sites that lose H3K27ac retain their H3K4m1 signature and remain sensitive to cleavage by DNase I due to their open chromatin architecture (115).

Epigenomic patterns distinguish training and tolerance

Because many studies reporting adaptive characteristics of the innate immune system predate the modern era of molecular biology, insufficient understanding at the molecular level meant that the magnitude of this process was perhaps underappreciated. Although much detail remains to be elucidated, several studies published in recent years demonstrate the essential role of epigenetic reprogramming in innate immune memory across various phyla (93, 96, 105, 112, 126). These seminal findings not only shed light on the molecular mechanisms underlying the capacity for monocytes to integrate micro-environmental experiences into their programs of gene expression that is a type of chromatin-based memory but also emphasize the potential reversibility of innate immune phenotypes (97).

Several studies describe the enrichment of H3K4m3 at promoters associated with trained immunity, for instance at genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines and intracellular signaling molecules after stimulation with β-glucan (106, 115), as well as at promoters of genes implicated in atherogenesis in cells trained with oxLDL (9). Further, the heterologous benefit of BCG vaccination is associated with persistent H3K4m3 enrichment at the promoters of genes encoding TNFα, IL6, and TLR4 (66). Similarly, H3K4m3 distinguishes attenuated (tolerizable) and induced (non-tolerizable) genes in immune tolerance. Although promoters of both classes of genes are trimethylated at H3K4 on LPS stimulation, this mark is selectively maintained at non-tolerizable promoters after restimulation (40). The positive correlation of H3K4m3 and transcriptional activity is well described across various organisms and cell types (6, 72, 114). Accordingly, inhibition of this modification by using the pan-methyltransferase inhibitor 5′-methylthioadenosine (MTA) precludes the adapted phenotypes induced by β-glucan (50), BCG (66), and oxLDL (9).

Although quantifying H3K4m3 can be informative of transcriptional competency or activity at discrete loci, it hardly exhausts the broad regulatory potential for histone modifications in innate immune memory. Recent deep sequencing analyses revealed distinct epigenomic signatures that are characteristic of trained immunity and tolerance (24, 97, 115). By generating epigenome-wide maps of H3K4m1, H3K4m3, H3K27ac, and DNase I sensitivity, Saeed et al. (115) defined distinct clusters of genomic regions reflecting putative transcriptional regulatory elements. Importantly, several of these clusters are differentially modulated in β-glucan training and LPS tolerance. This is most apparent at ∼500 promoters that concurrently gain H3K27ac and H3K4m3 exclusively in β-glucan-trained cells (115). Paralleling naive monocytes, β-glucan treatment results in partial establishment of macrophage-specific regions within the first 24 h of the in vitro training protocol. In contrast, LPS-treated cells exhibited stunted differentiation and delayed establishment of chromatin marks. This temporal observation is consistent with a failure of LPS-tolerized macrophages to deposit active histone marks at promoters of tolerized loci in response to a second LPS stimulation, including genes associated with lipid metabolism and phagocytic pathways (97).

Most remarkable, however, is the epigenetic distinction observed across the respective repertoires of distal enhancers within these phenotypic extremes of the innate immune memory spectrum (97, 115). LPS and β-glucan pretreatment induced a distinct set of enhancers generating signal-dependent differences in gene expression. Some enhancer regions (1212) show consistent enrichment of H3K27ac across both treatment conditions, whereas more than 40% of all dynamic enhancers gain de novo H3K27ac exclusively in cells trained with β-glucan. On the other hand, acetylation of a much smaller subset of enhancers is restricted to LPS-tolerized cells (115). Taken together, these studies suggest that β-glucan induces comprehensive epigenetic rewiring of promoters and enhancers, whereas LPS tolerance is characterized by a subtle epigenetic signature closely reflecting that of naive macrophages.

The epigenome modulating effects of β-glucan were further exemplified by the exciting finding that it can partially reverse LPS tolerance. Exposure of LPS-tolerized cells to β-glucan for 24 h in vitro restored their capacity for cytokine production (97). Importantly, this reversal of immunoparalysis to a more responsive phenotype was also observed in monocytes isolated from volunteers with experimental endotoxemia restimulated with β-glucan ex vivo. The effects of β-glucan were demonstrated by the reinstitution of the transcriptional response to LPS at otherwise tolerized genes. This process was associated with the restoration of H3K27ac at enhancers previously precluded by LPS exposure, demonstrating the ability for β-glucan to effectively erase and reprogram innate immune memory. These findings indicate that β-glucan-induced receptor pathways remain at least partially responsive in LPS-tolerized cells, and they could lead to novel immunomodulatory strategies for the clinical management of sepsis (97).

DNA methylation in innate immune memory

Despite its historically robust associations with genome organization and transcriptional regulation, much less is known about the potential role of DNA methylation in innate immune memory. Epigenome-wide analyses have demonstrated a general loss of 5mc during ex vivo monocyte to macrophage differentiation (97, 138). The vast majority of differentially methylated regions occurred at distal enhancers, with only a small fraction enriched at gene promoters. In terms of macrophage subtypes, a distinct methylation pattern was observed for LPS-treated cells. On the other hand, the methylome of β-glucan-treated cells more closely resembled that of naive macrophages (97).

Similar to its histone counterpart, 5mc is enzymatically reversible. The first step of this process requires oxidation of 5mc by the ten-eleven-translocation (TET) family of dioxygenases (18) to generate 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmc). This variant can then be further processed to 5-formylcytosine and 5-carboxylcytosine—newly characterized epigenetic marks that appear to be associated with silenced (26), poised (122), or activated (109) enhancer elements. The importance of 5mc and 5hmc dynamics in the course of innate immune memory remains an open question. The answer necessitates an ability to accurately distinguish these variants of cytosine methylation. The method used by the aforementioned study (97), bisulfite sequencing, is the gold standard for 5mc analysis and involves the conversion of unmethylated cytosine residues to uracil. Importantly, both 5mc and 5hmc are resistant to bisulfite conversion (121), meaning that DNA demethylation could be underestimated by using this method. By extension, such a method of analysis confounds the discovery of 5hmc-specific functions in genome regulation. To this end, a recent study highlights advantages and caveats of commonly used epigenome-wide 5hmc profiling technologies and demonstrates that the interpretation of 5hmc data is significantly influenced by the sensitivity of the method used (121).

Transcriptional and epigenetic memory

The biological consequences of this epigenetic reprogramming are numerous and varied. Where they intersect is at the level of transcriptional regulation; however, the precise mechanisms of this control require further investigation. Among the catalogue of gene expression changes associated with innate immune memory is a subset of genes whose pattern of expression reveals a profound transcriptional memory. Within this cluster, a broad distinction can be drawn between genes that are primed for transcriptional activation and those that are persistently altered.

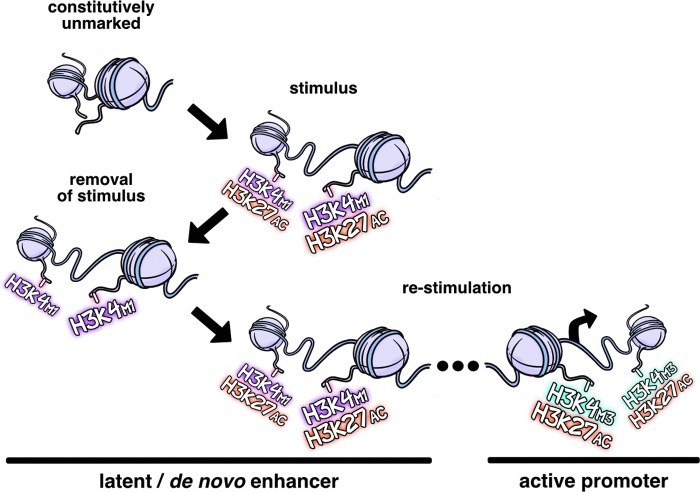

A recently emerged paradigm of primed transcriptional memory centers on the induction of de novo or latent enhancers (99). In unstimulated macrophages, these genomic regions are unbound by TFs and are largely devoid of the histone modifications that are characteristic of distal regulatory elements. However, they acquire signature epigenetic features of enhancers such as an open chromatin architecture marked by H3K4m1 and H3K27ac in response to specific stimuli. On removal of the activating stimulus, Ostuni et al. (99) demonstrated the persistence of H3K4m1 despite loss of H3K27ac at a fraction of decommissioned de novo enhancers. Moreover, the enhancers that retained the H3K4m1 signature exhibited a stronger response to rechallenge (Fig. 3). This chromatin-dependent transcriptional memory may at least partly explain the differential activation of enhancer repertoires, supporting the unique phenotypic properties adopted by macrophages as a function of anatomical location (42), and similar mechanisms are likely to shape chromatin architectures that are associated with innate immune memory. Indeed, the dynamics and genomic locations of H3K4m1-marked enhancers differ significantly between β-glucan training and LPS tolerance (97). Further, these findings are reminiscent of previous descriptions of H3K4m1-dependent metabolic memory in monocytes and other cell types (57).

FIG. 3.

Latent enhancers prime a transcriptional memory in macrophages. Constitutively unmarked distal regulatory elements acquire signature epigenetic features of enhancers such as an open chromatin architecture marked by H3K4m1 and H3K27ac in response to specific stimuli. On removal of the activating stimulus, regions that retain the H3K4m1 enrichment mediate a faster and more robust response to restimulation, supporting a role for this specific modification in the epigenetic memory of macrophages. H3K27ac, H3 histone-lysine-27 acetylation; H3K4m1, H3 histone-lysine-4 monomethylation.

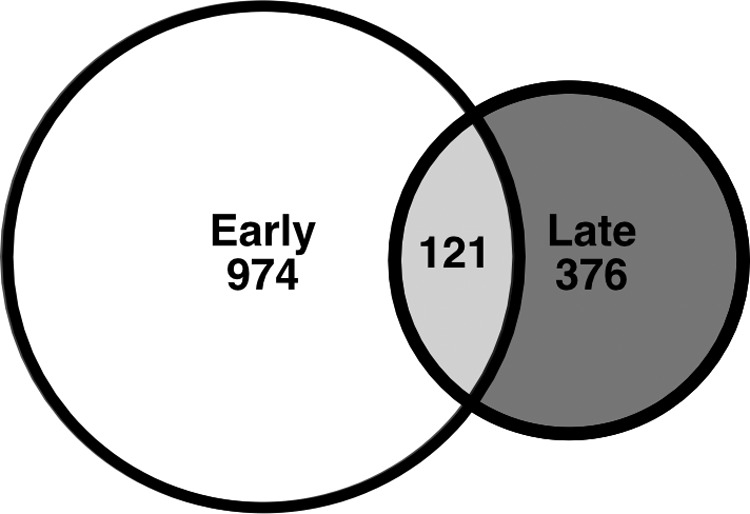

Contrasting primed memory, persistent memory is characterized by transcriptional activity that is sustained beyond removal of the activating stimulus. Monomethylation of H3K4 underlies persistent, high-glucose-mediated proinflammatory gene expression that is refractory to glycemic correction in vascular endothelial models of glycemic variability and diabetic mice (17). This epigenetic signature, written by the Set7 KMT, was later observed in monocytes of diabetic patients (101). Intersection of the transcriptome data from early and late timepoints described by Novakovic et al. (97) reveals a cluster of genes whose transcriptional response to β-glucan is maintained for 5 days in culture (Fig. 4). This includes genes downregulated 24 h after stimulation that are also downregulated on day 6, as well as genes upregulated on day 1 that remain in a state of heightened transcriptional activity for the duration of the experiment. Of course, this is a simplification as the activity of some genes may oscillate between altered and basal transcriptional states at intermediate time points. Nonetheless, this model may provide a useful framework to understand changes in gene expression that are associated with metabolic and other pathways that occur early in the process of trained immunity and support the phenotype of fully differentiated, trained macrophages. Discernment of the epigenetic proponents of persistent gene expression will inform about not only mechanisms that sustain the memories of macrophages but also long-term epigenetic programming of myeloid cells.

FIG. 4.

Training with β-glucan induces a program of persistent transcriptional memory. Persistent transcriptional memory is characterized by transcriptional activity that is sustained beyond removal of the activating stimulus. Intersection of transcriptome data derived from macrophages at early (24 h) and late (6 days) time points post β-glucan stimulation described by Novakovic et al. (97) (GSE85246) reveals a cluster of 121 genes whose transcriptional response is maintained for the duration of the experiment.

The heterologous protection conferred by vaccination with BCG far exceeds the lifespan of innate immune cells in the circulation (66). The remarkable finding that the trained phenotype and gene-specific H3K4m3 enrichment can be observed 3 months and even up to 1 year after vaccination has inspired interest in the physiological mechanisms mediating innate immune memory at the level of immune progenitor cells. Myeloid cell progenitors can mediate long-term TLR2-induced tolerance (146); however, much less is known about this process in trained immunity. Evolutionary conservation of innate immune memory across various phyla provides valuable opportunities to understand this biological process in humans (60). Using an experimental infection model, Torre et al. recently demonstrated that the induction of innate immune memory in planarians (phylum Platyhelminthes) is driven by a specific population of pluripotent stem cells (126). Although much controversy surrounds the transmissibility of histone modifications across generations in vertebrates, the role of DNA (de)methylation in myeloid differentiation is actively investigated (2, 137). Further, the heritability and potent gene-regulating functions of 5mc underscore the enthusiasm surrounding the role of this modification in sustaining cellular memories (14). Future studies should aim at characterizing the DNA methylomes of myeloid progenitors and terminally differentiated cells in the broader context of innate immune memory.

In light of the epigenetic changes and different modes of transcriptional memory that define innate immune memory, a key challenge is to understand the operational epigenetic machinery (145). Several epigenetic enzymes have been recently associated with macrophage function [recently reviewed by Hoeksema and de Winther (45)]; however, their roles in training and tolerance remain untested. One study reported significant upregulation of Set7 in response to β-glucan training (115). Although the importance of the MLL1 KMT to epigenetic enhancer signatures in macrophages has been recently described for processes such as TLR4 signaling (56, 65), the potential role of Set7 remains to be established. As an interesting link to metabolic regulation, genes encoding KDMs JMJD1A and JMJD2B are transcriptionally activated by HIF1α in response to hypoxia in primary epithelial cells as well as transformed cell lines (12, 67). In this search for epigenetic regulators, another potentially important clue was revealed by the study of Torre et al. (126). The trained phenotype of planarians is dependent on a KMT that shares homology with human Set8. This enzyme specifically methylates lysine 20 on H4 histones (87), a modification that is yet to be explored in the innate immune memory of vertebrates (60).

Recent evidence suggests that the identities of some of the factors responsible for the myriad epigenetic changes governing innate immune memory may be revealed through a deeper understanding of upstream signaling events that sustain epigenetic pathways and shape the deposition of chromatin marks (91).

Epigenetics and immunometabolism

Inhibition of either glycolysis or mTOR signaling interrupts the characteristic chromatin modification pattern and adapted phenotype of trained immunity, confirming a role for metabolic changes in epigenetic reprogramming. Further linking metabolic rewiring of cellular metabolism with innate immune memory, evidence increasingly supports the integration of metabolic information and transcriptional control via the enzymatic consumption of metabolites in epigenetic reactions (57). Specifically, the enzymatic activities of many chromatin modifiers are regulated, in part, by concentrations of metabolic intermediates (32). Fluctuating metabolite concentrations, therefore, potentiate continual adjustment of gene expression by modulating the epigenome to influence chromatin dynamics (57).

It is, therefore, reasonable to speculate that the profound metabolic changes associated with trained immunity could sustain epigenetic patterns or drive further alterations to the chromatin landscape at important regulatory regions through an interesting interplay between metabolites and gene regulation. Critical metabolic intermediates such as NAD+ and acetyl-CoA, which are altered in β-glucan-trained monocytes (24, 91), serve as cofactors or substrates for numerous HDACs and HATs, respectively (Fig. 5). The methylome is also sensitive to metabolic variation through changes to cellular levels of α-ketoglutarate, an essential cofactor for several lysine and cytosine demethylating enzymes (57, 82). Importantly, TCA cycle intermediates succinate and fumarate can inhibit certain demethylation reactions (143). The striking elevation of succinate and fumarate induced by the metabolic rewiring of trained macrophages, therefore, represents a plausible mechanism behind the integration of immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity.

FIG. 5.

Chromatin modifications unite immunometabolism and gene expression. The activities of many chromatin-modifying enzymes are regulated in part by concentrations of intermediates of energy metabolism. Repurposing of the TCA cycle modulates the epigenome of trained immunity. Members of the sirtuin family of HDAC enzymes are sensitive to intracellular NAD+/NADH ratios. Acetyl-CoA is the essential acetyl group donor to lysine acetylation (by HATs), linking intermediary carbon metabolism with chromatin dynamics and transcription. Histone lysine demethylating events are influenced by the elevated levels of succinate and fumarate that are associated with metabolic rewiring of trained macrophages. In particular, fumarate inhibits KDMs, thereby elevating the enrichment of H3K4m3 at the promoters of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines. H3K4m3, H3 histone-lysine-4 trimethylation; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Drawing on these molecular interactions, we recently demonstrated that the accumulation of fumarate as a function of glutamine replenishment of the TCA cycle connects immune pathways with epigenetic programs by inhibiting the H3K4 demethylase KDM5, thereby elevating the enrichment of H3K4me3 at the promoters of genes encoding proinflammatory cytokines (5). Moreover, exogenous fumarate itself induces a trained macrophage phenotype in terms of cytokine production that is again abolished by inhibition of glutaminolysis and glycolysis. At the epigenomic level, fumarate training echoes a proportion of the chromatin patterns induced by β-glucan, implicating its probable involvement in at least partially mediating the effects of classical training stimuli. Perhaps most remarkable is the observation that fumarate positively regulates transcription of genes encoding KDM5 isoforms, in addition to the epigenetic activity of these enzymes. From this interplay emerges a regulatory dichotomy with relevance for trained immunity: KDM5 activity and the downstream increases in cytokine production mediated by fumarate were attenuated by α-ketoglutarate (83).

Another important observation transpiring from this study was the induction of H3K27ac in cells trained with fumarate (5). This raises two main possibilities. First, fumarate could positively regulate the expression of genes encoding HATs or, reciprocally, negatively regulate HDAC gene expression by inhibiting demethylation of active chromatin marks. Second, fumarate inhibits KDM5 demethylases to regulate the chromatin-modifying activities of HATs or HDACs by altering their post-translational lysine methylation status (Fig. 5).

Finally, other metabolites could directly influence epigenetic regulation by mechanisms that are yet to be thoroughly characterized. A pertinent example is succinylation—a posttranslational modification of proteins in which a succinyl group is added to a lysine residue from succinyl-CoA (153). In accordance with the marked increases observed for succinate in trained immunity, lysine succinylation is considered an inflammatory signal for innate immune cells (125). Importantly, this modification is written to several sites of histone tails in human and yeast cells (144). Although details of the functional consequences of histone succinylation are currently undescribed, this modification induces a structural chromatin change that is greater than the change caused by lysine acetylation, by converting a positively charged residue to a negative charge (144). Future studies are predicted to strengthen this regulatory connection between chromatin biology and the metabolic characteristics of innate immune memory.

Multiple roles for lysine methylation in innate immune memory

The very definition of epigenetics has drawn its share of recent criticism (86), though perhaps largely from argument that is more semantic than biologic and stemming from an etymology rooted in developmental biology and heredity (139). It is now clear that epigenetic processes are not only restricted to roles in development but also shape the phenotypes of nondividing cells. Certainly more deserving of attention is the controversy surrounding the hierarchical significance of epigenetic modifications in gene expression. A stringent interpretation of the histone code hypothesis (51) tends to attribute regulatory primacy to chromatin modifications while appreciating that TFs bind specific DNA sequences to activate nearby genes. However, rather than displace the long-standing importance of TFs, the emerging picture is one where epigenetic enzymes and chromatin modifications synergize with traditional regulators of transcription. To this end, a conceptual framework that encompasses the molecular tagging of chromatin components to designate functional genomic regions and support transcriptional responses to distinct signaling cues is consistent with the current understanding of gene regulation.

Though not entirely overlooked, the role of TF networks for the induction of innate immune memory has not received the same attention as chromatin modifications. Approximately 12% of known TFs are variably expressed during macrophage differentiation, tolerance, and training (115). Further, discrete binding motifs within condition-specific dynamic epigenomic regions indicate the importance of particular TFs for the distinct transcriptional programs of trained and tolerized macrophages (97, 115).

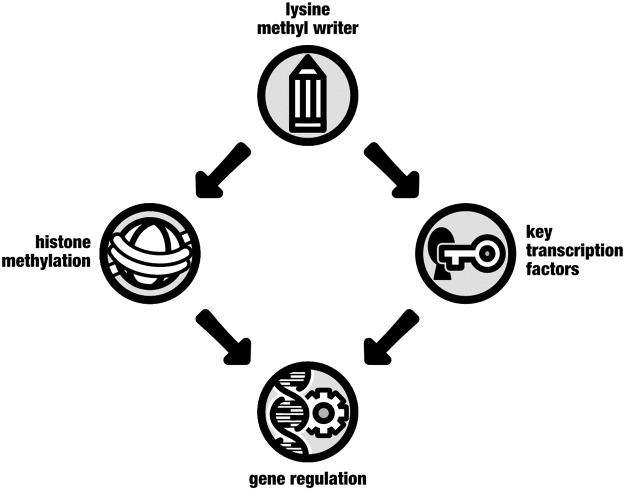

Although pre-treatment with a pan-methylation inhibitor impedes the epigenetic rewiring and, consequently, blocks the adapted phenotype of trained cells (9, 50, 66), histones and DNA are not the only gene-regulating factors modulated by methylation. post-translational methylation has in recent years emerged as a ubiquitous and pivotal determinant of TF stability and trans-activity, revealing the dual regulatory roles of KMTs and KDMs in histone-dependent and -independent mechanisms of transcription (Fig. 6) (22, 70). Similar regulatory functions are attributed to post-translational lysine acetylation (102, 123). Of particular relevance to the induction of innate immune memory for its potential influence on cellular metabolism is the post-translational methylation recently shown to regulate HIF1α function. Set7-mediated methylation of HIF1α diminishes its occupancy on glycolytic gene promoters, thereby inhibiting gene expression (78). Importantly, this modification is reversed by lysine-specific histone demethylase 1 (LSD1) (64), an epigenetic enzyme that is influenced by cellular levels of flavin adenosine dinucleotide and is, therefore, sensitive to metabolic variation (44). It is currently unknown as to whether similar methyl-dependent regulation of HIF1α, or other TFs that direct the overall metabolic shift, impacts the induction of trained immunity.

FIG. 6.

Lysine methylation regulates gene expression by chromatin-dependent and chromatin-independent mechanisms. In addition to chromatinized histone substrates, epigenetic lysine methyl writers can exert their influence on gene expression by specific methylation of amino acid residues on the surface of non-histone proteins. The functional consequences for substrates such as key transcription factors include changes in protein stability and activity that modulate downstream transcriptional outcomes.

This avenue of inquiry could also reveal novel regulatory mechanisms that are immediately associated with the trained cell's response to secondary stimuli. The rapidity and magnitude of macrophage responses to TLR stimulation is facilitated by the expeditious deployment of stimulus-responsive TFs such as AP-1, NFκB, and STAT family members to regulatory elements of inflammatory genes (91). As described earlier, these transcriptional responses are intensified in trained immunity by the sustained accessibility of chromatin owing to specific epigenetic patterns. However, the same pathways that support chromatin modifications may also influence TF dynamics. Much like histones, the functional consequences of TF lysine methylation are site specific (Table 2).

Table 2.

Lysine Methylation Regulates Transcription Factor Function

| Transcription factor | Methylated lysine | Regulatory function | KMT | KDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIF1α | K32 | Repression | Set7 (64, 78) | LSD1 (64) |

| K391 | Degradation | LSD1 (74) | ||

| NFκB-p65 | K37 | Activation | Set7 (34) | |

| K218 | Activation | NSD1 (84) | FBXLII (84) | |

| K221 | Activation | NSD1 (84) | FBXLII (84) | |

| K310 | Repression | SETD6 (76) | ||

| K314 | Degradation | Set7 (148) | ||

| K315 | Degradation | Set7 (148) | ||

| STAT3 | K49 | Activation | EZH2 (31) | |

| K140 | Repression | Set7 (147) | LSD1 (147) | |

| K180 | Activation | EZH2 (63) | ||

| STAT1 | K685 (predicted) | Set7 (61) |

HIF1α, hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha; KDM, lysine demethylase; KMT, lysine methyltransferase; LSD1, lysine-specific histone demethylase 1.

In addition to their interactions with modified histones, binding of TFs can, in fact, facilitate the localization of epigenetic enzymes to sites of chromatin modification (58). A recent finding suggests that the stress-responsive TF ATF7 is a key regulator of long-term maintenance of epigenetic changes that enhance macrophage resistance to pathogens (150). In resting cells, ATF7 suppresses a group of innate immune-related genes by recruiting the H3K9 KMT G9a. In response to LPS stimulation, ATF7 is phosphorylated by p38 kinase and released from the chromatin. This causes a concomitant decrease in transcriptionally repressive H3K9m2 levels, culminating in a partially disrupted chromatin structure. Once ATF7 is depleted from the chromatin, it is not entirely reinstated back at the original binding sites, thus maintaining the expression of target genes for long periods as a type of epigenetic and transcriptional memory (149, 150).

Interestingly, many chromatin-modifying enzymes are themselves regulated by post-translational modifications, including lysine methylation and acetylation, suggesting a highly ordered and dynamic network of components that are capable of writing and erasing modifications at both the chromatin template and each other. For example, the enzymatic activity of a specific HAT known as p300/CBP-associated factor is post-translationally regulated by methylation and acetylation at numerous lysine residues (85, 117). Individual epigenetic enzymes, therefore, possess the potential to indirectly control multiple chromatin modifications. Mapping the inter-enzyme modification network of chromatin regulators has considerable capacity to expand our understanding of gene regulation (58).

Conclusion and Future Perspective

The defining premise of innate immune memory rests on the cell's ability to retain and recall information about previous exposures. This cellular memory is facilitated by major shifts in metabolic and transcriptional pathways. It is becoming increasingly clear that such changes are inextricably and bidirectionally linked through epigenetic mechanisms. These findings add to the growing body of literature supporting a prominent role for the epigenome in recording adaptive experiences. In particular, they shed light on the potential mechanisms underlying primed and persistent transcriptional memory in innate immune training and tolerance. Further, stable and heritable epigenetic changes have the capacity to explain the long-term memory effects of trained immunity observed months after BCG vaccination (66).

Trained immunity is a fundamental property of the mammalian immune response, and it is increasingly investigated as an adjuvant to potentiate next-generation vaccines (79). In recent years, there has been a shift by some in the field to understand the broader therapeutic possibilities. For example, inducers of trained immunity such as BCG and β-glucan represent current (19, 89) and prospective approaches to the clinical management of various cancers. The restoration of cytokine production in experimental endotoxemia by β-glucan at the level of histone modification and transcriptional reactivation highlights the potential of epigenetic therapy in the broader context of immune paralysis (97). On the other hand, innate immune reprogramming may have adverse effects in various pathological contexts, particularly under chronic inflammatory conditions in which trained immunity is induced by endogenous ligands. The enhanced and maladaptive immune responsiveness foreshadows important consequences as well as novel therapeutic opportunities for the development, progression, and stability of atherosclerotic lesions (27). Further exploration may uncover new clinical strategies to treat vascular complications arising from the deleterious hyperactivity of innate immune cells sustained by features of metabolic syndrome and the diabetic milieu (135). Indeed, hyperglycemia can induce long-term epigenetic modulation of inflammatory gene expression (23, 101).

Clinical exploitation will be enhanced by the rapidly accumulating knowledge of the molecular mechanisms underlying the metabolic and epigenetic rewiring of adaptive innate immune responses. Pharmacological modulation of metabolism has shown potential in other pathophysiological situations. For example, inhibition of glycolysis limits pathological neovascularization (118). The emerging picture of trained innate immunity outlines a process driven by complex interactions between metabolic and epigenetic factors. Not surprisingly, the immune-modulating effects of metabolic inhibitors are, at least partly, mediated by epigenetic changes. Such studies have already disclosed important clues to the identities of the nuclear machinery responsible for maintaining chromatinized signatures of innate immune memories (5), providing an early framework for the development of clinical strategies that target epigenetic regulators. Several drugs that inhibit epigenetic enzymes are already approved for clinical use in the fields of oncology and hematology (104). Small-molecular histone mimic BET inhibitors (iBET) have shown promise for treatment of inflammation (95). Though effective in blocking LPS-induced tolerance when co-administered in human monocytes, iBET treatment was unable to reverse memories of previous LPS stimulation (97).

While offering arguably greater precision for the adjustment of discrete transcriptional events, direct pharmacological manipulation of the epigenetic proponents of trained immunity raises some important considerations. As described earlier for the pan-methyl inhibitory properties of MTA, certain HDAC inhibitors exhibit broad substrate specificity. Even compounds that target specific enzymes may have unintended effects, as the complex interplay between epigenetic enzymes and traditional transcriptional machinery forecasts the potential pleiotropic impact of epigenetic drugs across a broad spectrum of protein substrates and gene regulatory processes (77, 107). The complexities of pharmacological epigenetic modulation are further exacerbated by cell-type-specific roles of the chromatin-modifying machinery. For example, macrophage and endothelial cell HDAC3 play opposing roles in the development of atherosclerosis in mice (46, 152). For these reasons, recent technological and scientific advances such as single-cell transcriptomic and epigenomic profiling will form the cornerstone of future research efforts.

Indeed, we are only beginning to scratch the surface of a remarkably intricate system of long-term gene regulation and transcriptional memory. In combination with DNA sequence profiling, epigenomics could determine the functional significance of genetic variants to innate immune function (19), including those occurring in regulatory and noncoding regions. Epigenomic and transcriptomic profiling could also unravel the contributions of miRNA and lncRNA to trained immunity, which remain largely unexplored but are of significant regulatory potential (91). Further, TF substrates of epigenetic enzymes can be inferred from chromatin and gene expression profiles and protein substrate motifs (61). Successful future therapeutic approaches to the manipulation of innate immune memory of infectious and autoinflammatory diseases will emerge only from a comprehensive understanding of key molecular events and epigenetic interactions.

Abbreviations Used

- β-glucan

β-1,3-(D)-glucan

- 5hmc

5-hydroxymethylcytosine

- 5mc

5-methylcytosine

- BCG

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

- BET

bromodomain and extra-terminal

- CpG

5′-cytosine-phosphate-guanine-3′ dinucleotide

- H3K27ac

H3 histone-lysine-27 acetylation

- H3K4m1

H3 histone-lysine-4 monomethylation

- H3K4m3

H3 histone-lysine-4 trimethylation

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- HIF1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- iBET

BET inhibitors

- KDM

lysine demethylase

- KMT

lysine methyltransferase

- lncRNA

long noncoding RNA

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LSD1

lysine-specific histone demethylase 1

- MAMP

microbe-associated molecular pattern

- miRNA

micro RNA

- MTA

5′-methylthioadenosine

- mTOR

mechanistic target of rapamycin

- oxLDL

oxidized low-density lipoprotein

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylation

- PPP

pentose phosphate pathway

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- TF

transcription factor

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Acknowledgments

L.A.B.J. and M.G.N. were supported by an ERC Consolidator Grant (No. 310372) and a Spinoza grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. N.P.R., L.A.B.J., and M.G.N. received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 667837. Figures include Shark Party font by Aryel Filipe.

References

- 1.Aaby P, Roth A, Ravn H, Napirna BM, Rodrigues A, Lisse IM, Stensballe L, Diness BR, Lausch KR, Lund N, Biering-Sorensen S, Whittle H, and Benn CS. Randomized trial of BCG vaccination at birth to low-birth-weight children: beneficial nonspecific effects in the neonatal period? J Infect Dis 204: 245–252, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Errico D, Vento-Tormo R, Sieweke M, and Ballestar E. Epigenetic control of myeloid cell differentiation, identity and function. Nat Rev Immunol 15: 7–17, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson JD. Protective vaccination against tuberculosis, with special reference to BCG vaccine. Minn Med 31: 1336, 1948 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arts RJ, Carvalho A, La Rocca C, Palma C, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, Kleinnijenhuis J, Lachmandas E, Goncalves LG, Belinha A, Cunha C, Oosting M, Joosten LA, Matarese G, van Crevel R, and Netea MG. Immunometabolic pathways in BCG-induced trained immunity. Cell Rep 17: 2562–2571, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Ter Horst R, Carvalho A, Bekkering S, Lachmandas E, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, Cheng SC, Wang SY, Habibi E, Goncalves LG, Mesquita I, Cunha C, van Laarhoven A, van de Veerdonk FL, Williams DL, van der Meer JW, Logie C, O'Neill LA, Dinarello CA, Riksen NP, van Crevel R, Clish C, Notebaart RA, Joosten LA, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, and Netea MG. Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell Metab 24: 807–819, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, and Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker PB. and Workman JL. Nucleosome remodeling and epigenetics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 5: 1–20, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekkering S, Blok BA, Joosten LA, Riksen NP, van Crevel R, and Netea MG. In vitro experimental model of trained innate immunity in human primary monocytes. Clin Vaccine Immunol 23: 926–933, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, and Riksen NP. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34: 1731–1738, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bekkering S, van den Munckhof I, Nielen T, Lamfers E, Dinarello C, Rutten J, de Graaf J, Joosten LA, Netea MG, Gomes ME, and Riksen NP. Innate immune cell activation and epigenetic remodeling in symptomatic and asymptomatic atherosclerosis in humans in vivo. Atherosclerosis 254: 228–236, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, and Lander ES. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell 120: 169–181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyer S, Kristensen MM, Jensen KS, Johansen JV, and Staller P. The histone demethylases JMJD1A and JMJD2B are transcriptional targets of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF. J Biol Chem 283: 36542–36552, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biering-Sorensen S, Aaby P, Napirna BM, Roth A, Ravn H, Rodrigues A, Whittle H, and Benn CS. Small randomized trial among low-birth-weight children receiving bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination at first health center contact. Pediatr Infect Dis J 31: 306–308, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev 16: 6–21, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bistoni F, Vecchiarelli A, Cenci E, Puccetti P, Marconi P, and Cassone A. Evidence for macrophage-mediated protection against lethal Candida albicans infection. Infect Immun 51: 668–674, 1986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borriello F, Iannone R, Di Somma S, Loffredo S, Scamardella E, Galdiero MR, Varricchi G, Granata F, Portella G, and Marone G. GM-CSF and IL-3 modulate human monocyte TNF-alpha production and renewal in in vitro models of trained immunity. Front Immunol 7: 680, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brasacchio D, Okabe J, Tikellis C, Balcerczyk A, George P, Baker EK, Calkin AC, Brownlee M, Cooper ME, and El-Osta A. Hyperglycemia induces a dynamic cooperativity of histone methylase and demethylase enzymes associated with gene-activating epigenetic marks that coexist on the lysine tail. Diabetes 58: 1229–1236, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Breiling A. and Lyko F. Epigenetic regulatory functions of DNA modifications: 5-methylcytosine and beyond. Epigenetics Chromatin 8: 24, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buffen K, Oosting M, Quintin J, Ng A, Kleinnijenhuis J, Kumar V, van de Vosse E, Wijmenga C, van Crevel R, Oosterwijk E, Grotenhuis AJ, Vermeulen SH, Kiemeney LA, van de Veerdonk FL, Chamilos G, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JW, Netea MG, and Joosten LA. Autophagy controls BCG-induced trained immunity and the response to intravesical BCG therapy for bladder cancer. PLoS Pathog 10: e1004485, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.C.N. Experiences with the BCG vaccination in the providence of Norbotten (Sweden). Revue de la Tuberculose 12: 617–636, 1931 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calo E. and Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: what, how, and why? Mol Cell 49: 825–837, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carr SM, Poppy Roworth A, Chan C, and La Thangue NB. post-translational control of transcription factors: methylation ranks highly. FEBS J 282: 4450–4465, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Z, Miao F, Paterson AD, Lachin JM, Zhang L, Schones DE, Wu X, Wang J, Tompkins JD, Genuth S, Braffett BH, Riggs AD, Group DER, and Natarajan R. Epigenomic profiling reveals an association between persistence of DNA methylation and metabolic memory in the DCCT/EDIC type 1 diabetes cohort. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113: E3002–E3011, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JH, Rao NA, Aghajanirefah A, Manjeri GR, Li Y, Ifrim DC, Arts RJ, van der Veer BM, Deen PM, Logie C, O'Neill LA, Willems P, van de Veerdonk FL, van der Meer JW, Ng A, Joosten LA, Wijmenga C, Stunnenberg HG, Xavier RJ, and Netea MG. mTOR- and HIF-1alpha-mediated aerobic glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science 345: 1250684, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chistiakov DA, Bobryshev YV, Nikiforov NG, Elizova NV, Sobenin IA, and Orekhov AN. Macrophage phenotypic plasticity in atherosclerosis: the associated features and the peculiarities of the expression of inflammatory genes. Int J Cardiol 184: 436–445, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi I, Kim R, Lim HW, Kaestner KH, and Won KJ. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine represses the activity of enhancers in embryonic stem cells: a new epigenetic signature for gene regulation. BMC Genomics 15: 670, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christ A, Bekkering S, Latz E, and Riksen NP. Long-term activation of the innate immune system in atherosclerosis. Semin Immunol 28: 384–393, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, and Staels B. Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev 262: 153–166, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cooper ME. and El-Osta A. Epigenetics: mechanisms and implications for diabetic complications. Circ Res 107: 1403–1413, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crisan TO, Cleophas MCP, Novakovic B, Erler K, van de Veerdonk FL, Stunnenberg HG, Netea MG, Dinarello CA, and Joosten LAB. Uric acid priming in human monocytes is driven by the AKT-PRAS40 autophagy pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: 5485–5490, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dasgupta M, Dermawan JK, Willard B, and Stark GR. STAT3-driven transcription depends upon the dimethylation of K49 by EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 3985–3990, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donohoe DR. and Bultman SJ. Metaboloepigenetics: interrelationships between energy metabolism and epigenetic control of gene expression. J Cell Physiol 227: 3169–3177, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durrant WE. and Dong X. Systemic acquired resistance. Annu Rev Phytopathol 42: 185–209, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ea CK. and Baltimore D. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity through lysine monomethylation of p65. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 18972–18977, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eberharter A. and Becker PB. Histone acetylation: a switch between repressive and permissive chromatin. Second in review series on chromatin dynamics. EMBO Rep 3: 224–229, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El Gazzar M, Liu T, Yoza BK, and McCall CE. Dynamic and selective nucleosome repositioning during endotoxin tolerance. J Biol Chem 285: 1259–1271, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farlik M, Halbritter F, Muller F, Choudry FA, Ebert P, Klughammer J, Farrow S, Santoro A, Ciaurro V, Mathur A, Uppal R, Stunnenberg HG, Ouwehand WH, Laurenti E, Lengauer T, Frontini M, and Bock C. DNA methylation dynamics of human hematopoietic stem cell differentiation. Cell Stem Cell 19: 808–822, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferguson RG. and Simes AB. BCG vaccination of Indian infants in Saskatchewan. Tubercle 30: 5–11, 1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Finch JT, Lutter LC, Rhodes D, Brown RS, Rushton B, Levitt M, and Klug A. Structure of nucleosome core particles of chromatin. Nature 269: 29–36, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]