Abstract

We assessed the acceptability of nurse-delivered mobile phone-based counseling to support adherence to antiretroviral treatment (ART) and self-care behaviors among HIV-positive women in India. We conducted open-ended, in-depth interviews with 27 HIV-positive women and 19 key informants at a government ART center in Karnataka, India. Data were analyzed with interpretive techniques. About half of the HIV-positive women owned a mobile phone and many had access to mobile phones of their family members. Most women perceived phone-based counseling as a personalized care approach to get information on demand. Also, women felt that they could discuss mental health issues and ask sensitive information that they would hesitate to discuss face-to-face. Findings indicate that, when compared with text messaging, mobile phone-based counseling could be a more acceptable way to engage with women on ART, especially those with limited literacy. Future studies should focus on testing mobile phone-based information/counseling and adherence interventions that take the local context into account.

Keywords: : HIV-positive women, mobile phones, counseling, antiretroviral treatment adherence, India

Introduction

More than 50% of the 37.2 million adults living with HIV in the world are women, and most are of childbearing age. India, with 2.39 million people living with HIV, 39% of whom are women, has the third largest population in the world after South Africa and Nigeria.1 While the prevalence of HIV among women in the general population is still fairly low, a growing body of evidence indicates that women in India are highly vulnerable to poor HIV prevention and treatment outcomes.2–4 Indeed, women are at high risk for a variety of interrelated mental health and psychosocial barriers that may limit their access to HIV services and ability to engage in care. Among these are limited mobility, depression, intimate partner violence, low literacy level, gender bias, poor social support, and HIV-related stigma in community and healthcare settings.5,6

Even though good adherence is a decisive factor in the success of HIV prevention and treatment, little attention has been paid to self-care (e.g., medication adherence) promotion interventions for HIV-positive women. Even in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs in resource-limited settings, the focus is largely on prevention of HIV acquisition in the unborn baby rather than on promoting antiretroviral (ART) adherence among HIV-positive women throughout pregnancy and beyond.7,8 Furthermore, these programs have not addressed concurrent risk factors in women.

Studies have shown that as many as 40–90% of women in India who have either started or are eligible for ART are lost to follow-up.9–13 Recent studies support the promise of mobile phone-based behavioral interventions for improving adherence to medications among both men and women.14–17

However, given the dynamic matrix of concurrent cofactors that vary from woman to woman over time, it is unlikely that commonly relied upon unidimensional technology-based intervention approaches, such as SMS reminders to improve adherence in the context of HIV, will be adequate to achieve sustained improvement in secondary prevention and treatment outcomes in this population.

Therefore, phone-based counseling may be a more suitable approach for addressing the health challenges faced by women in resource-limited settings. Moreover, this approach may be acceptable to those vulnerable HIV-positive women of low socioeconomic status, in both rural and urban areas, who often have difficulties deciphering even simple text messages given literacy and language barriers.16,18 We are not aware of any previous published reports on the use of mobile technologies for delivery of evidence-based behavioral interventions for HIV-positive women in India.

Our preliminary work indicates that a theory-guided adherence phone intervention originated in the United States might be well suited to the context given the widespread use of cell phone technology, limited resources and access, and the multidimensional, patient-centered approach used to build patient–provider rapport, establish sources of support, and enable and empower problem solving to address interrelated, multitiered barriers to care. But it needs to be adapted to the sociocultural context. Therefore, we conducted qualitative formative research to assess the preliminary feasibility and acceptability of mobile phone contacts by HIV specialist nurses as a means to improve ART adherence and to support self-care among HIV-positive women with psychosocial challenges.19–21 This article reports findings from this qualitative formative research (Phase 1 of a two-phase study).

Methods

Design and sample

We conducted open-ended, in-depth interviews with 27 HIV-positive women and 19 key informants at a government-run ART center in the Belgaum district located in the state of Karnataka in southern India. The HIV prevalence is high in Belgaum (>1%) and the epidemic is characterized by higher incidence among women. The center caters to socially disadvantaged, low-income HIV-positive patients.22 The clinic enrolls at least 8–10 new HIV-positive people daily, 50% of whom are HIV-positive women (personal communication with Karnataka Health Promotion Trust, a local NGO working with HIV-positive people).

The study received approval from the ethics committees at Yale University, New Haven, CT, and the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS) in Bangalore, India. All eligible participants were informed of the study objective and invited by a trained study staff to participate in this study. Participants were enrolled if they provided written informed consent and met eligibility criteria. Patient participants were HIV-positive women aged 18 years and above, formally enrolled in, or eligible to initiate, ART, and, able to communicate in Hindi, English, or Kannada (native language in Karnataka). Stakeholders were: (1) healthcare providers (HCPs) at the HIV testing and ART centers, and (2) family members or friends accompanying an HIV-positive woman in the center, but not necessarily of the women who were participants in the study.

Interview procedures

Structured, open-ended interviews were conducted in a private setting by trained Master's level research assistants under the supervision of the site principal investigator. Participant interviews assessed their medical history and beliefs (e.g., need for and desire to take antiretroviral medication), sources of support and barriers to self-care activities, access to care, phone ownership and usage, and attitudes and preferences concerning intervention content and delivery. Contents of topic guides were viewed by experts in HIV-positive women's health in the United States and in India to establish face validity and cultural relevance.

Data analysis

The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English. Two bilingual research staff randomly selected 10% of transcripts to check for accuracy in comparison with their respective audio files, and likewise compared 10% of translated text with their respective transcripts. Data were explored using applied thematic analysis.23 We developed a codebook based on a priori codes derived from the topic guides and existing literature on acceptability and use of mobile phone-based interventions to improve ART adherence.

In addition, inductive/emergent codes and categories identified from the text were added to the codebook, which was then used to further code and categorize the data. Differences in coding were discussed among data analysts and resolved by consensus. Constant comparative method was used to compare and contrast the codes/categories within and across cases.24 An analytic thematic approach was used to further identify linkages between the categories and derive subthemes, which were further collapsed under broader themes to describe the acceptability of mobile phone-based counseling for ART adherence and self-care may be impeded or facilitated. Data analyses were informed by application of relevant concepts from self-regulation theory and the technology acceptance model (TAM).20,25–28

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

As seen in Table 1, the HIV-positive women participants' mean age was 35 years [standard deviation (SD) = 8]. More than one-third (37%) were currently married, about half (48%) were illiterate, and about three-fifths (59%) were unemployed. Eighty-one percent reported that their husbands were also HIV positive. More than two-thirds (70%) reported having disclosed their HIV status to others; however, the majority of the disclosures were only to their immediate family members. There were 19 key informants. Two of the nine HCPs were physicians, the rest were either HIV testing or ART counselors. The majority (n = 7/9) had over 5 years of experience in HIV service provision. Among the 10 family members who accompanied HIV-positive women, 8 were women who were mothers, daughters, daughter-in-law, or mother-in-law; and 2 were men—a maternal uncle and a brother. Overall, the mean age of the family members was 30 years (SD 10.7).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of HIV-Positive Women Participants

| Characteristics | N = 27 (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 35 ± 8 |

| Marital status | |

| Currently married | 10 (37) |

| Widowed | 17 (63) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 13 (48) |

| Primary | 3 (11) |

| Secondary | 3 (11) |

| Higher secondary | 4 (15) |

| College graduation | 3 (11) |

| Occupation | |

| Unemployed | 16 (59) |

| Employed | 11 (41) |

| HIV status of spouse | |

| HIV positive | 22 (81) |

| HIV negative/unknown status | 5 (19) |

| HIV status of children | |

| HIV positive | 4 (15) |

| HIV negative/unknown status | 23 (85) |

| Living status | |

| Joint family | 2 (7) |

| Nuclear | 26 (93) |

| Disclosure of HIV status | |

| Disclosed | 19 (70) |

| Not disclosed/not applicable | 8 (30) |

| Mobile phone ownership | |

| Owns a personal mobile phone | 14 (52) |

| Shared/no phone | 10 (37) |

| No phone | 3 (11) |

SD, standard deviation.

Current use of mobile phones

About half of the HIV-positive women participants (n = 14/27; 51.9%) reported having a personal mobile phone; others had access to a mobile phone of their family members and a few did not have any access. Some of the women reported that they could receive calls but did not know how to make calls. Similarly, not all of the women were aware of how to send a text message or how to read one.

Barriers and facilitators to timely visits to ART center, and ART adherence

HCPs reported that most of the HIV-positive women on ART were adherent to their regimens. Eight main themes concerning barriers to care and seven themes concerning facilitators of care emerged from the data. Themes and their exemplars are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Barriers and Facilitators to Timely Visits to Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Center and Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Adherence

| Theme | Representative quote |

|---|---|

| Barriers | |

| Priority on well-being of the family | “My only concern is that no one should be harmed by me.” IDI_16 |

| “Whatever the problem like health or anything, women is giving last preference. First husband, then children, and finally she will give some time for herself if she has any time left. This tradition still exists here.” HCP_2 | |

| Financial strain and cost of travel | “Delay in providing money to travel to ART center also prevented women from visiting ART centers on time to collect ART. When the bus fare was hiked, we asked for TA [travel allowance] they said only 100 Rupees is can't provided—not more than that. I come with my brother till [a town] and from there I come alone as we can't bear bus fare for 2 persons.” IDI_26 |

| Disclosure | “My mother-in-law doesn't know about this, I'm scared if she comes to know she might throw me out of the house and my daughters are still young so I have not informed this to my mother-in-law or my daughters … I have not discussed about my disease either with my mother's family or with my in-laws and my children till now. My children will be enquiring about the reason why I am taking tablets every day. I have lied to them that it is because of the fever I am taking tablets and these tablets are vitamin tablets.” IDI_5 |

| “But at in-laws' house they treat me badly and discriminate me. They won't allow me to stay at their home after the death of my husband, that's why I am staying with my sister. My mother-in-law has thrown me out of their house.” IDI_24 | |

| Fear of transmission of HIV to other family members from casual contact | “Whoever gets infected, ultimately females will be blamed. Some of the females, who are infected, won't be preparing food thinking that they will spread the infection.” HCP_6 |

| “My mother in law and child's paternal uncle, totally 5 members were at home. They thought that the illness would spread to them and hence they chased us out from the house.” IDI_18 | |

| Lack of knowledge about ART adherence due to low literacy | “I have no information on HIV and AIDS and I have not heard of this disease before. My husband also have not discussed about this disease. I am not aware what doctor had told in front of my husband. I could not follow anything they have explained … I'm really not aware why they are giving me these tablets, I'm illiterate I cannot understand anything, I cannot read what is written on the tablet box.” IDI_3 |

| “I haven't attended school. He studied up to 4th standard and he knows everything, but I don't know anything. If anybody tells then only I'll be able to understand.” IDI_19 | |

| Mental health issues | “I can't work like before. I'm too depressed and I don't want to live. Three four times I thought of ending the life.” IDI_21 |

| “I don't have children to look after me and I am troubling my sister. If she got married, what will I do? I feel scared when thinking about my future. I don't want to live, better to end the life. But I should have to live like this.” IDI_24 | |

| Drug interactions/side effects | “I was taking medicine for TB here only. I was not able to adjust for many days, 6 months course was discontinued and started a fresh one for one year … After taking ART medicine the afternoon dose caused side effect so they discontinued that dose.” IDI_1 |

| “With these medicines I feel fatigue, develop giddiness and also have vomiting episodes. I can't do any work.” IDI_24 | |

| Skipping tablets | “Sometimes I forget to take medicine during morning and I have faced problem. I can't sleep and I won't be hungry. I have forgotten twice or thrice in a month.” IDI_4 |

| “So far I could not feel any positive results from this tablet. Before starting these tablets also, I was sensing severe pain in my legs, after one year's consumption of these tablets also, it hasn't come down even with these medicines. If I work, I experience tiredness. Now, I am under a dilemma that whether to continue these tablets or not. No one has given me proper details about ART tablets. This might be explained to my husband, but, so far, he has not informed me anything about this.” IDI_9 | |

| Facilitators | |

| Overall healthcare services provided by the Government provision of free ART, travel/reimbursement of travel costs, satisfaction with services, trust and competency of providers | “My medicines are given free and they also give me my bus charges. Outside we need to spend 3000 [INR] for these medicines hence we come and collect it here.” IDI_19 |

| “I have been taking ART tablets for last six months and has benefited with this. Reimbursement of bus charge has also helped a lot.” IDI_5 | |

| “Here the doctors and nurses love and support me a lot.” IDI_7 | |

| “After the death of her husband, she appears sad and upset most of the time … She won't share much with us and most of the issues she discusses only with the counselor here in the hospital. They understand her problem and supports her.” FM_2 | |

| Determination to live for one's children | “I have 2 boys and have to get them married. They are my strength and my support and except that I don't have any worries. They are everything to me and I live only for them and being happy for them.” IDI_14 |

| Visible benefits of ART | “After taking ART medicines, I don't have any health issues … I have one advantage after taking this medicine, with that my CD4 count is increased. Doctor had told me that, it is a good sign if the CD4 count is more.” IDI_7 |

| Some strategies adapted to help in adherence | “I have not missed my tablets any day. I keep it in my cupboard. I change the tablet box which I brought in center and keep in one plastic cover and throw the empty box. I always carry that cover in my bag. When I go out of station then also I carry medicines with me. Everybody asks me what medicines I'm taking. I will tell them that my blood count is less and hence I'm taking tablets.” IDI_8 |

| “I have not forgotten to take these tablets in these 2 months, and my mother always makes sure that I have taken tablets after meal. My daughter also reminds me. All my sisters and mother supports me.” IDI_13 | |

| Presence of family support | “My elder children know about my disease and are very supportive. They remind me to take tablet every day and they are not unhappy about this. Except my children I have not disclosed this to any of my friends or relatives … I have no problem and my children give me full support and fill me with courage back support.” IDI_5 |

| “My father spent lot of money, but there was of no use. After coming to government hospital now I have improved … My elder brother knows about my diseases. My elder brother and mother looks after me very well. Elder brother and younger brother stayed with me in hospital and taken care of me well. They will get tablets for me. No one knows about my disease at my in-laws' house.” IDI_15 | |

| Knowledge about ART | “Since 4 years I used to come to do CD4 test once in 6 months, but now since 6 months they have started me on medicines. I don't know much about this ART medicines but I know that I should take this medicines till I die.” IDI_7 |

| Coping strategies | “I will tell you one thing. I always think in a way that I don't have HIV. You are younger to me and I am a mother. Even if others tell many things, I always try not to think too much about it and also try to live in a way that I don't have this illness.” IDI_8 |

| “Sometimes I think about the future. God is there to take care of everything and why should I think. Nothing will be solved by thinking or worrying and we won't get anything from it.” IDI_14 | |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; FM, family; HCP, healthcare provider; IDI, in-depth interview with HIV-positive woman.

The key reasons cited for nonadherence or lost-to-follow up were: placing priority on the well-being of family members over one's own health, financial dependence on others, and nondisclosure of HIV status to family members. Similarly, many HCPs believed that HIV-positive women were more likely to face problems in adherence and regular visits to ART centers when compared with men.

Several facilitators for timely visits to the government ART center were reported by the participants. Key reported reasons were provision of free ART through government ART centers and reimbursement of their travel costs to reach ART centers. In addition, many women expressed satisfaction with the services they received from the government ART centers and reported that HCPs furnished necessary information about HIV and ART. Some women, however, reported several barriers for timely visits to the ART center. A key barrier was non-disclosure of HIV status to their family members as it meant that many women needed to visit the ART center without the knowledge of family members. On the other hand, even if the women's HIV status was already known to other family members, they often suffered lack of support from the family members. This was commonly in the form of blaming the woman for bringing HIV infection to the family despite having acquired HIV infection from her husband and delay in providing money for travel to the ART center, which sometimes prevented the women from collecting ART on time.

The women outlined several factors that facilitated ART adherence. Determination to live for one's children was a common theme. Adherence to ART was also better among women who believed that ART was beneficial since they could witness increase in their body weight and in their ability to do work, including routine household chores. Adequate knowledge about HIV and fear of consequences of nonadherence also aided adherence. Tactics like having a fixed daily routine for taking tablets for instance, at 9 am and 9 pm, and packing enough pills when going to stay outside one's hometown helped some women improve adherence. Family members' support in the form of reminders was also helpful in some instances. Yet even those women who had not disclosed their HIV status to other people adopted some strategies to help them in taking ART without fail. These included lying to others that they routinely took “vitamin pills” or that they take pills “to increase the amount of blood,” removing the name label in the ART bottle, transferring pills to a different container, and hiding pills in inaccessible places.

Nevertheless, women reported certain barriers to adherence as well. Women who were relatively less educated or were illiterate reported inadequate knowledge about ART and missed pills. For instance, one person admitted that she did not know the benefits of taking ART and hence was not sure whether to continue the pills or not. Another person bluntly stated that as she was an illiterate she could not understand why and how long to take ART. Moreover, giving priority to the health of husband and children and not taking care of one's own health was another reason identified by the women, which was corroborated by HCPs as well. Even though not explicitly stated by women, mental health issues faced by them clearly seemed to affect their ability to be adherent. Indeed, some of the concerns reported by women were: anxiety about their children's future, for example, their education and marriage; fear of disclosure of one's HIV status to others and potential negative consequences to self and other family members—especially children; financial burden due to HIV-related treatment costs for self and other family members; and needless fear of transmission of HIV to other family members from casual contact. For those women who were on both ART and some other drugs, such as antidepressants or antituberculosis drugs, adherence to ART was difficult due to high pill burden and associated side effects.

Patients' perceptions of use of mobile phones for ART adherence and health promotion

In general, HIV-positive women thought that the use of mobile phones would be beneficial to them as they could then clarify their doubts over phone, ask for any new information they needed, and have someone to talk to whom they could trust (Table 3). Receiving mobile phone calls was acceptable to most of the women as they felt that the time available in one-on-one interactions with the HCPs at the ART center was limited. Besides, while in ART centers, women too were in a hurry to leave as they had to get back to their homes quickly before someone else in their home began suspecting where they had been especially so in the case of women whose HIV status was not known to other family members. Information and counseling over phone was appealing to women as they viewed it as personalized care and a convenient mode of getting information on demand. Furthermore, some women thought that they would be more comfortable asking for certain apparently sensitive information by phone that they would otherwise hesitate to ask in person, such as condom use, getting remarried to a HIV-negative man, and the possibility of HIV transmission if one cooks for her family. Only one person explicitly preferred face-to-face discussion rather than mobile phone, but she too was receptive to receiving once-a-month phone call from a HCP.

Table 3.

Patients' Perceptions of Use of Mobile Phone for Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Adherence and Health Promotion

| Theme | Representative quote |

|---|---|

| Willingness to receive calls from HCP | “Will you give us a phone? I don't know to use it. If you call I can talk. But my husband has one and you can call me anytime and any day in a week. If you call, I can tell my husband that it is my doctor and talk to you. If he is at home he will give me the phone.” IDI_21 |

| “If any staff nurse calls me, I can talk. If you call me in the night that will be better because mobile is with my sister and she will be at home during night time. You can call me twice a week, I can speak. I don't have mobile and my sister has one. If you call when she is out she will tell once she is back and I can make calls then.” IDI_24 | |

| Preference regarding when to call and frequency of calls | “After 6pm twice a week you can talk to me. It would be nice.” IDI_18 |

| “You call me twice or once in a week I would love to talk to you and share my feelings, I don't mind to talk to you over the phone. I know to give missed call and SMS also, after 4pm I'm free if you give me a missed call I will call you back.” IDI_1 | |

| “You can call me anytime. I don't have any restrictions from my family. I feel good and happy when you call me and speak to me I feel that there is someone who can share my feelings. Give your number and I also will call you.” IDI_13 | |

| Discussion of mental health issues | “But if I feel sad, then I can call you and talk to you.” IDI_2 |

| “If you talk to people like me over phone, we will feel very happy. We will get peace. We will feel happy that we got a friend. And also if we feel sad, we can talk to you and we may get peace. And we also feel there is someone to listen to our pains and to support us. You are like God to us. There is no one to ask us anything. At least you are there. If I have any problem I will call you.” IDI_1 | |

| Phone counseling was not a priority, but wanted financial assistance | “If you can support my children it will be good or else it will be difficult for us to survive. We don't have any assets and there is no one to look after my children.” IDI_21 |

| “In my opinion instead of talking over the mobile why don't you help our children. It would have been more helpful.” IDI_27 | |

| Confidentiality | “I don't have mobile, my husband has one. But if I start discussing this over the phone with someone, people at home might hear you and I don't want that to happen and it might create problems. Here at the hospital, they have taken our number. We fear they might call and create problem so we come on exact date and collect tablets and go. We don't want anyone to call and it might create problem so we have not shared our number. Please don't mind me, I'm not interested to know more information in this regard so please don't call me.” IDI_17 |

| “I have a phone with me. If anyone calls me I can receive a call. If you call I can talk but if there will be someone around me it would create problem to me. Because of these reasons I don't give my number to anybody. If required, I will call you. You give your number and need not to call.” IDI_7 |

HCP, healthcare provider; IDI, in-depth interview with HIV-positive woman.

Most of the women were of the view that as they were already adherent to ART, the mobile phone communications would, in fact, be more helpful in discussing mental health issues. There were a few who did not give much importance to health promotion messages over phone, adding that their chief priority was obtaining assistance for supporting their children's education or getting financial assistance for their family members, for example, for marriage of their daughters.

Women differed in their preference for receiving calls from a HCP, making calls to a HCP or both. Among the 25 of the 27 women who responded, 50% preferred receiving calls from a nurse, whereas just 8% preferred making calls to the nurse, and 38% opted for both. Two women, however, did not prefer receiving any calls from HCPs. Women who had their own mobile phones or whose HIV status was known to most of their family members thought it was acceptable to either receive calls from HCPs or to call HCPs; by contrast, those whose HIV status had not yet been disclosed to their family members preferred to make calls to HCPs.

The women also expressed preferences regarding the frequency of phone calls that ranged from a few calls a week to one or two calls a month; and also regarding the timing of the calls. Specifically, many preferred to be called in late evenings, especially if they worked, or shared their family member's mobile phone. Furthermore, the women expressed concerns about the possible risk of their HIV status being inadvertently disclosed to their family members or neighbors when the calls would be made, and about the possibility of being gossiped about for receiving calls from nonrelatives. They also offered suggestions on what to do if someone else other than the intended person answers the phone. For example, in such a case the caller could tell the other person that she was a friend of the woman whom she had called. Participants preferred to receive calls exclusively from women HCPs to call them.

Providers' and family members' perceptions of use of mobile phones for ART adherence and health promotion

In general, HCPs and family members opined that receiving information and counseling from nurses through mobile phone calls would be useful to improve the mental health outcomes of HIV-positive women who would find it “good to talk to someone.” Five themes emerged from their perceptions regarding the potential usefulness of mobile phone for promoting health of HIV-positive pregnant women (Table 4).

Table 4.

Providers' and Family Members' Perceptions of Use of Mobile Phones for Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) Adherence and Health Promotion

| Theme | Representative quote |

|---|---|

| Perceived need for support for mental health promotion | “They [HIV-positive women] will be highly depressed. They think too much like who will look after me? Who will take care about my health? Then they think about their children's future, and how the society will look at them when they come to know that they have HIV. They also will have the worry to face husband and parents. All these thoughts push them to severe depression.” HCP_2 |

| “We have come across with one or two cases got admitted in inpatient department. They will be diagnosed and getting treated by the Psychiatrist. We will provide antidepressant tablets along with ART. Support is very important here. The family members may not be knowing that they are taking tablets and it is difficult to tell all. We treat them as their family members because they will not inform anybody that they are taking tablets.” HCP_8 | |

| Support for mobile phone counseling | “I have mobile. But she will not be with us always. At times for a change she will go and stay at my sister's home for more than one week. I also will go to work and will be back in home late night. So, if you call me during day time I won't be able to give your call. She would like to talk to you.” FM_1 |

| “We are happy to receive call from the nurse. … She has a mobile phone which is personal. It will be switched on always. There is no problem in providing a phone to her for making and receiving calls from the nurse.” FM_3 | |

| Perception of additional burden on nurses by increase in the number of unnecessary calls | “Once rapport is built, they will call you whenever is convenient for them or else call them according to their convenience. Being girls/ladies if you give your numbers to them, they might trouble you by calling very often. I had experienced it already and changed my SIM twice. Whether it is 11 or 12 in the night, they call me and tell they are having vomiting or fever. For small reasons they will get anxious and call us.” HCP_6 |

| “The call from a nurse will definitely help them. Our nurses don't have time. They will be comfortable talking to the nurse and it won't affect their personal life. They should make time to talk to you. It is better let the patient make call whenever they are free and have any problem.” HCP_10 | |

| Providers' suggestion to get the family's support first | “The mobile based intervention counseling is helpful if the condition at the home is good. If the family is not supportive and phone call comes to them there will definitely have problem arise. And the timing of call, family criteria and family response must be considered. We have to take all those in to consideration and then we have to proceed. … We should know when she will be free and when she can talk and whether there any chance to emerge new problem, etc. should assess first and then make call. Initially we can make a call once in three days or weekly once. As the days goes on we can call twice in a month or weekly once. If you start twice in a week, then you can switch to weekly once. Gradually we can reduce the frequency and by the time we can understand whether they got adjusted or not. According to the needs of each one we can plan.” HCP_7 |

| “Around 70% of them might talk over the phone about their issues if you call them according to their convenience … They will be available at their homes after 5pm. While calling them you need get their consent. If they agree you can call them around 5 times in a month.” HCP_9 | |

| Reservations in relation to whether women would like to receive phone counseling | “Females may have restriction to speak on mobile. Most of the people from our side will not be provided with a mobile. Some may have suspiciousness if they give mobile. Educated people may provide phone. If you convince their family they may speak. You can call them in the afternoon or in the evening. It will be good if you call one or two times in a week because they will be coming to take medicines. If you call them again and again they will feel bad.” HCP_8 |

| “Receiving such calls will be a problem for some women. It may create hindrance when they are with relatives or neighbors or else they are in any function.” FM_11 | |

| Suggestions for who can initiate the call, appropriate time to call, and how to maintain confidentiality | “We can call them once or twice in a week but it is advisable to talk when they call. When you call it may not be the right time to speak or some of the family members will be with her so she cannot discuss her problems and she may find it difficult to do so. So I feel you should talk to her when she calls instead of staff nurse calling them.” HCP_3 |

| “I think it will be good if you can make call to her. She will be comfortable sharing her health issues to the nurse over phone. She will be able to talk to the nurse in the afternoon. She will be free from all the works in the afternoon. It will be good if you make calls twice in a week and to let her call to the nurse whenever she is in need. Both the nurse call to her regularly and let her call to the nurse will be better option. So, whenever she wants to share anything she can call and the nurse also can check her condition in between. She has mobile phone. There are chances to have some problems at home when you call, so better you discuss with her and fix a time.” FM_5 |

ART, antiretroviral treatment; FM, family; HCP, healthcare provider.

HIV-positive women's acceptance in receiving mobile phone calls seemed to be facilitated by prior trust in HCPs, perceived competency of HCPs in dealing with mental health issues, and perceived need for the support for mental health promotion. Family members expressed their willingness to lend their phone to their HIV-positive female family member, but suggested that calls be made in the late evening once they returned from work. Also, they did not object to the idea of providing a mobile phone to their HIV-positive family member for personal use. As nurses were expected to be receiving and making calls to HIV-positive women in the planned intervention, some doctors were concerned about the additional burden on nurses. Moreover, nurses worried about the risk of receiving calls from women even for “trivial matters.” In other words, nurses anticipated there might be a lower threshold in contacting a provider over phone, and possible psychological dependence of the HIV-positive women on them. Thus, HCPs offered some suggestions, including restricting phone calls from women to office hours or setting a maximum limit to the number of calls to be made or to be received per week or month.

HCPs also suggested that before the start of phone counseling interventions that consent should be obtained from other family members, explicit preference of patients should be determined with respect to whether they would like to only receive calls, make calls, or both; nurses and patients should agree on the frequency of calls to be made or received, and on the appropriate time to call; and a protocol should be used to maintain patient confidentiality.

Summary and unifying framework

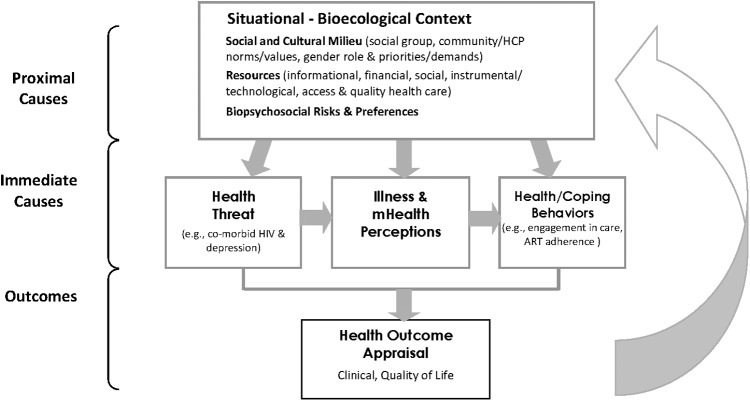

Taken together, the data establish the significance of several factors associated with the acceptance of an mHealth intervention and its potential for enhancing engagement in care among women living with HIV in India as summarized above. The process by which the factors interact to drive outcomes can be understood within an adapted model (Fig. 1) that provides a dynamic, unifying framework. Self-care behavior of the individual living with HIV is essential to the effectiveness of HIV treatments since most of the day-to-day management takes place outside of healthcare settings. A host of research conducted by Leventhal et al. has shown that the way in which individuals interpret or make sense of their illness (illness representation) drives self-care behaviors such as adherence to medication. Illness representations are highly individual, influenced by a host of internal and external information that are often ambiguous, fluctuate daily, and are affected by situational variation.25,29,30 They may or may not be compatible with medical norms and influence how new health information is processed and acted upon. At the most basic level, the individual's sense of self, who she is in relation to the world, develops through physical and psychological capacities and vulnerabilities (physical–mental health) in interaction with her social circumstances. The social circumstances obviously vary by the cultural and socioeconomic environment as well as by a host of commonplace and chance events that occur over the lifetime. These operate to shape an individual's perceived options and expectations, which in turn influence the moment-by-moment interpretation of stimuli and selection of self-regulating actions. The individual interprets stimuli and acts to maintain or enhance an acceptable or desirable status or avert or reduce a stimulus that is interpreted as unacceptable or undesirable. The individual considers his/her options and selects an action based upon his/her perception of viable options and past successes and failures under similar circumstances. 25,30,31

FIG. 1.

Conceptual framework.

An mHealth intervention may provide an efficient and acceptable way to reach women to promote self-care behavior. Drawing from this model, a central element of the potential efficacy of the mobile phone intervention is how the woman comprehends her illness in the context of her life circumstances (sociocultural milieu), experiences and perceptions of the potential benefits of technology-facilitated support from a HCP. While the process is highly nuanced and individualized, our findings indicate that several factors will be central to the acceptability and usefulness of an mHealth intervention to vulnerable women living with HIV. These include the individual's perceptions of its usefulness in the context of her knowledge of HIV and ART, financial circumstances, and sociocultural context (e.g., perceived stigma and quality of interpersonal relationships), priorities, and preferences.

Discussion

The present study examined the perspectives of HIV-positive women, their family members, and HCPs on the use of mobile phones as a mode to facilitate ART adherence and address the psychosocial issues of HIV-positive women. Most women and HCPs were enthusiastic about a mobile phone-based counseling intervention by nurses as it offered them an opportunity to receive personalized evidence-based information about services, and treatment on demand from a trained person. As nurses were likely to be women, HIV-positive women felt that it would be easier for them to discuss certain apparently gender-sensitive information and mental health issues that they would hesitate to ask in person. Some of the issues that were identified included the need to directly address many of the prevalent misconceptions regarding spread of HIV/AIDS, side-effects due to ART, fear of disclosure, stigma, mental health issues such as depression, and limited social and financial support for women.

The analysis identified the themes related to usefulness of technology and the various barriers and facilitators to adherence to treatment situated within and beyond the individual, and social (family and HCPs) factors to understand HIV+ women's acceptance of mHealth counseling intervention. Stigma emerged as a common theme that would have a bearing upon the achievement of the overall outcome engagement by enhancing self-care. This indicates the need to address co-occurring psychosocial issues, including stigma and discrimination as they affect illness and treatment perceptions and access to and engagement in treatment and self-care activities. Areas of risk and strengths can be identified, corresponding health information and support provided, and skills developed that are individualized to the patient's schema and situational context. In doing so, the content may be viewed as more meaningful and more readily integrated into the individual's cognitive schema and acted upon in problem-solving efforts to manage barriers and emotional responses that surround both the primary difficult experience of living with an illness condition in the context of the individual's situational challenges. Furthermore, the mobile phone contact provides a means of facilitating coordination of services, continuity of care, and patient monitoring.

Although the HCPs thought that HIV-positive women had good adherence, they were positive about the use of mobile phone counseling because most women faced many psychosocial issues which they thought needed to be addressed to ensure long-term adherence and continue treatment. Based on their personal experience, however, some HCPs cautioned against sharing of mobile numbers of nurses with patients as they thought it may lead to emotional drain associated with stress and burnout of the nurse counselors. This suggests the need to develop a consensus on this issue and possibly to develop preliminary guidelines to avoid both provider burnout and build patient self-care behavior and risk of overdependence on providers.32,33

Some of the major implementation challenges identified by the patients and the key informants are, HIV-positive women's limited access to a personal phone, unfamiliarity with mobile phone usage, including making calls and text messaging, and low literacy levels.34,35 Gender disparities in mobile ownership in many low middle-income countries are influenced by social norms, which reflect women's role, status and empowerment, in society, and consequently, their relationship with mobile technology.36,37 Similarly, in our study population only 50% women had personal phones while others shared a phone. Therefore, many women indicated that they would be dependent on receiving calls subject to the phone's availability and there were concerns about privacy and the possibility of disclosure of their HIV status to other family members or within the community if the calls were not managed well. In view of the pervasive stigma associated with being HIV positive, gender-specific concerns regarding privacy need to be taken into consideration to improve participation of women who have shared phone access, to increase the reach of the mHealth interventions. Overall, women were receptive to the calls from nurses and due to very cheap mobile call tariffs, free local incoming calls, free portability of numbers and high penetration rate, lack of funds to recharge phones, and changing numbers and/or cell phone service providers did not emerge as a limiting factor. Our findings are similar to those from qualitative studies on mobile phone use and perception for adherence among HIV-positive patients in the United States and Peru.38–41

Barriers to the use of mobile phone-based counseling interventions could be more challenging among patients in resource-poor settings. However, there are many ways that could be employed to better protect patient privacy. For example, the ability of the patient to contact the nurse as per her convenience may help to ensure the uptake of the intervention and to maintain confidentiality. Mobile phone-based interventions among women may need to ensure access to a personal phone and ensure privacy and confidentiality when calls are made by interventionists. Also, it is equally important that during counseling nurses be nonjudgmental and know the rights of HIV-positive women, and understand the link between cultural practices and gender inequality that might prevent women in accessing healthcare. In short, the intervention framework needs to take into account the context of the local patient populations.6,15,42–44

This study demonstrates the value of using formative research to contextualize the intervention components according to the local sociocultural environment of HIV-positive women accessing care at a government ART center in a multicultural, poor, semiurban setting in South India. Important issues to be discussed with the women during the calls require a pragmatic approach that directly addresses the needs identified by participants, and strategies to improve treatment adherence and their uptake of mental healthcare and social services. Although most women were receptive to calls from providers, individual patient characteristics and the pattern of mobile phone usage may impede their participation in proposed interventions.45

Our study has some limitations. First, an inherent limitation in most qualitative research studies is its lack of generalizability.24,46 The participants were recruited from a single government-run ART center from South India. Considering India is a diverse country with different languages and culture, the applicability of the proposed intervention components to other parts of the country may be limited. However, our findings are likely transferrable to other settings with similar characteristics and contexts. Also, most of the psychosocial issues and use of mobile phones and phone apps in reaching HIV+ individuals in resource-rich countries identified in our study are similar to findings from studies conducted in other resource-limited settings.18,40,41,47–49 Another potential limitation is social desirability bias in that participants might have provided certain responses that they thought could be the desired responses by the interviewers.50,51 However, the interviewers did emphasize confidentiality and also explicitly probed for any unfavorable or alternative perspectives from participants and provider key informants. Future research should continue to explore other factors and contexts to help us clearly characterize strategies that integrate counseling within a broader health promotion framework for HIV-positive women and men.

Many HIV-positive women own or have access to mobile phones and are willing to receive mobile phone-based counseling from HCPs. Possible advantages of phone-based counseling over traditional face-to-face counseling are the increased chance of discussing important mental health and sensitive issues with HCPs and mutually convenient and flexible timing to receive health counseling. Mobile phone-based counseling by nurses appears to be a promising and acceptable way to reach and engage women on ART with limited levels of literacy in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, challenges that need to be addressed in such mobile phone-based counseling interventions include the risk of inadvertent disclosure of HIV status of the clients to others, and the initial discomfort of the participants in getting used to a technology-based health counseling. Future mobile phone-based health interventions need to take these concerns and preferences into account to increase the uptake of such interventions by the local population.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, and staff at the ART center, especially Dr. Shanta Desai (Senior Medical Officer), Dr. Attiq Rehaman (Medical Officer), and Ms. Swapna Hulasogi (Counselor). The study was supported by the United States National Institutes of Health (R21MH100939), the Indian Council of Medical Research (HIV/INDOUS/152/9/2012-ECD-II), and the ITRA project, funded by DEITy, India [Ref. No. ITRA/15(57)/Mobile/HumanSense/01].

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the authors has commercial associations that might create a conflict of interest in connection with submitted articles.

References

- 1.The Gap Report. 2014. Available at: www.refworld.org/docid/53f1e1604.html (Last accessed May23, 2018)

- 2.Chandra PS, Ravi V, Desai A, Subbakrishna D. Anxiety and depression among HIV-infected heterosexuals—A report from India. J Psychosom Res 1998;45:401–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyamathi AM, Sinha S, Ganguly KK, et al. Challenges experienced by rural women in India living with AIDS and implications for the delivery of HIV/AIDS care. Health Care Women Int 2011;32:300–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghosh P, Arah O, Talukdar A, et al. Factors associated with HIV infection among Indian women. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:140–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandra PS, Satyanarayana VA, Satishchandra P, Satish KS, Kumar M. Do men and women with HIV differ in their quality of life? A study from South India. AIDS Behav 2009;13:110–117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradhan BK, Sundar R. Gender impact of HIV and AIDS in India. 2006. Available at: www.undp.org/content/dam/india/docs/gender.pdf (Last accessed May23, 2018)

- 7.Panditrao M, Darak S, Kulkarni V, Kulkarni S, Parchure R. Socio-demographic factors associated with loss to follow-up of HIV-infected women attending a private sector PMTCT program in Maharashtra, India. AIDS Care 2011;23:593–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Both J, van Roosmalen J. The impact of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) programmes on maternal health care in resource-poor settings: Looking beyond the PMTCT programme? A systematic review. BJOG 2010;117:1444–1450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachani D, Rewari BB. Antiretroviral therapy: Practice guidelines and National ART Programme. J Indian Med Assoc 2009;107:308., 310–314, 316 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Semret N. Nicodimos. The Association between Domestic Violence and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Southern India. University of Washington, Seattle, Washington, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta KG, Baxi R, Patel S, Parmar M. Drug adherence rate and loss to follow-up among people living with HIV/AIDS attending an ART Centre in a Tertiary Government Hospital in Western India. J Family Med Prim Care 2016;5:266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sarna A, Pujari S, Sengar AK, Garg R, Gupta I, Dam J. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy & its determinants amongst HIV patients in India. Indian J Med Res 2008;127:28–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarna A, Bachani D, Sebastian M, Sogarwal R, Battala M. Factors affecting enrolment of PLHIV into ART services in India. New Delhi: Population Council, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller CW, Himelhoch S. Acceptability of mobile phone technology for medication adherence interventions among HIV-positive patients at an urban clinic. AIDS Res Treat 2013;2013:670525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan CV, Kaufman DR. A technology selection framework for supporting delivery of patient-oriented health interventions in developing countries. J Biomed Inform 2010;43:300–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haberer JE, Kiwanuka J, Nansera D, Wilson IB, Bangsberg DR. Challenges in using mobile phones for collection of antiretroviral therapy adherence data in a resource-limited setting. AIDS Behav 2010;14:1294–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalichman SC, Cherry J, Cain D. Nurse-delivered antiretroviral treatment adherence intervention for people with low literacy skills and living with HIV/AIDS. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2005;16:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shet A, Arumugam K, Rodrigues R, et al. Designing a mobile phone-based intervention to promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy in South India. AIDS Behav 2010;14:716–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds NR, Sun J, Nagaraja HN, Gifford AL, Wu AW, Chesney MA. Optimizing measurement of self-reported adherence with the ACTG Adherence Questionnaire: A cross-protocol analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007;46:402–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds NR. The problem of antiretroviral adherence: A self-regulatory model for intervention. AIDS Care 2003;15:117–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leventhal H, Safer MA, Panagis DM. The impact of communications on the self-regulation of health beliefs, decisions, and behavior. Health Educ Q 1983;10:3–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parande MV, Mantur BG, Parande AM, et al. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus & hepatitis B virus co-infection in Belgaum, southern India. Indian J Med Res 2013;138:364–365 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guest G, MacQueen KM, Namey EE, eds. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss A, Corbin JM, eds. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc., 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leventhal H, Brissette I, Leventhal EA, Cameron L, Leventhal H. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness. In: The Self-Regulation of Health and Illness Behaviour. Cameron LD. and Leventhal H, eds. London: Routledge, 2003: pp. 42–65 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leventhal H, Phillips LA, Burns E. The common-sense model of self-regulation (CSM): A dynamic framework for understanding illness self-management. J Behav Med 2016;39:935–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Campbell JI, Aturinda I, Mwesigwa E, et al. The technology acceptance model for resource-limited settings (TAM-RLS): A novel framework for mobile health interventions targeted to low-literacy end-users in resource-limited settings. AIDS Behav 2017;21:3129–3140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q 1989;13:319–340 [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Mahen HA, Flynn HA, Chermack S, Marcus S. Illness perceptions associated with perinatal depression treatment use. Arch Womens Ment Health 2009;12:447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baines T, Wittkowski A. A systematic review of the literature exploring illness perceptions in mental health utilising the self-regulation model. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2013;20:263–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leventhal H, Leventhal EA, Breland JY. Cognitive science speaks to the “common-sense” of chronic illness management. Ann Behav Med 2011;41:152–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Dyk AC. Occupational stress experienced by caregivers working in the HIV/AIDS field in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res 2007;6:49–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vawda YA, Variawa F. Challenges confronting health care workers in government's ARV rollout: Rights and responsibilities. PER 2012;15:1–36 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waldman L, Morgan R, George A. mHealth and gender: Making the connection. London: UK Department for International Development (UKAID), 2015; 6 p [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deshmukh M, Mechael P. Addressing Gender and Women's Empowerment in MHealth for MNCH: An Analytical Framework, mHealth Alliance. 2013. Available at: www.villagereach.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/gender_analytical_framework_report.pdf (Last accessed October13, 2017)

- 36.van der Kop, Mia L, Muhula S, et al. Participation in a mobile health intervention trial to improve retention in HIV care: Does gender matter? J Telemed Telecare 2017;23:314–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Women GC. Bridging the gender gap: Mobile access and usage in low-and middle-income countries. London: GSMA Connected Women. Google Scholar, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paudel V, Baral KP. Women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA), battling stigma, discrimination and denial and the role of support groups as a coping strategy: A review of literature. Reprod Health 2015;12:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blashill AJ, Perry N, Safren SA. Mental health: A focus on stress, coping, and mental illness as it relates to treatment retention, adherence, and other health outcomes. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2011;8:215–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baranoski AS, Meuser E, Hardy H, et al. Patient and provider perspectives on cellular phone-based technology to improve HIV treatment adherence. AIDS Care 2014;26:26–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curioso WH, Kurth AE. Access, use and perceptions regarding Internet, cell phones and PDAs as a means for health promotion for people living with HIV in Peru. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2007;7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeVito Dabbs A. An intervention fidelity framework for technology-based behavioral interventions. Nurs Res 2011;60:340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carey MP, Braaten LS, Jaworski BC, Durant LE, Forsyth AD. HIV and AIDS relative to other health, social, and relationship concerns among low-income urban women: A brief report. J Womens Health Gend Based 1999;8:657–661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyer-Viola LA, Corless IB, Webel A, Reid P, Sullivan KM, Nichols P. Predictors of medication adherence among HIV-positive women in North America. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2014;43:168–178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Everett-Murphy K, De Villiers A, Ketterer E, Steyn K. Using formative research to develop a nutrition education resource aimed at assisting low-income households in South Africa adopt a healthier diet. Health Educ Res 2015;30:882–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams B, Amico KR, Konkle-Parker D. Qualitative to assessment of barriers and facilitators to HIV treatment. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2011;22:307–312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smillie K, Van Borek N, Abaki J, et al. A qualitative study investigating the use of a mobile phone short message service designed to improve HIV adherence and retention in care in Canada (WelTel BC1). J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care 2014;25:614–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rana AI, van dB, Lamy E, Beckwith CG. Using a mobile health intervention to support HIV treatment adherence and retention among patients at risk for disengaging with care. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:178–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saberi P, Siedle-Khan R, Sheon N, Lightfoot M. The use of mobile health applications among youth and young adults living with HIV: Focus group findings. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2016;30:254–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Randall DM, Fernandes MF. The social desirability response bias in ethics research. In: Citation Classics from the Journal of Business Ethics: Celebrating the First Thirty Years of Publication. Michalos AC. and Poff DC, eds. New York: Springer, 2013; pp. 173–190 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 1982;7:363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]