Abstract

Hibernation is an effective energy conservation strategy that has been widely adopted by animals to cope with unpredictable environmental conditions. The liver, in particular, plays an important role in adaptive metabolic adjustment during hibernation. Mammalian studies have revealed that many genes involved in metabolism are differentially expressed during the hibernation period. However, the differentiation in global gene expression between active and torpid states in amphibians remains largely unknown. We analyzed gene expression in the liver of active and torpid Asiatic toads (Bufo gargarizans) using RNA-sequencing. In addition, we evaluated the differential expression of genes between females and males. A total of 1399 genes were identified as differentially expressed between active and torpid females. Of these, the expressions of 395 genes were significantly elevated in torpid females and involved genes responding to stresses, as well as contractile proteins. The expression of 1004 genes were significantly down-regulated in torpid females, most which were involved in metabolic depression and shifts in the energy utilization. Of the 715 differentially expressed genes between active and torpid males, 337 were up-regulated and 378 down-regulated. A total of 695 genes were differentially expressed between active females and males, of which 655 genes were significantly down-regulated in males. Similarly, 374 differentially expressed genes were identified between torpid females and males, with the expression of 252 genes (mostly contractile proteins) being significantly down-regulated in males. Our findings suggest that expression of many genes in the liver of B. gargarizans are down-regulated during hibernation. Furthermore, there are marked sex differences in the levels of gene expression, with females showing elevated levels of gene expression as compared to males, as well as more marked down-regulation of gene-expression in torpid males than females.

Keywords: Bufo gargarizans, gene expression, hibernation, liver, energy conservation

1. Introduction

Hibernation is an effective energy conservation strategy adopted by endotherms to cope with the adverse environmental conditions during the winter [1,2,3]. During the hibernating period, the metabolic rate, heart beat rate, and oxygen consumption of hibernating small mammals can experience remarkable reductions [4,5,6]. Estivation is a survival strategy for some poikilotherms (e.g., amphibians and reptiles) against the dry season in summer [7,8]. In amphibians, the metabolism during torpor or estivation may be depressed by as much as 80% of the normal metabolic rate [8,9]. Marked physiological transitions in energy utilization take place in torpid amphibians [1].

For instance, lipids stored in white adipose tissue can be hydrolysed to free fatty acids and glycerol with the enzyme lipase, which will last both the hibernating period and the active period, but conversion to ketone bodies and glucose occurs in liver during the hibernating period [10]. The ketone bodies are an important source of energy, and can be transmitted to other tissues [11]. Hence, it is thought that the liver plays a major role in physiological regulation of metabolism during the hibernating period [1,12,13].

Until now, the molecular and genetic basis of hibernation physiology has been extensively investigated in mammals using large-scale genomic approaches [14,15,16]. Available evidence suggests that many genes involved in metabolism are differentially expressed during the hibernating period. For instance, most genes involved in carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism, detoxification and molecular transport in liver tissue are down-regulated in hibernating squirrels [17,18]. A total of 1358 differentially expressed genes in the liver between active and hibernating bats were mainly involved in metabolic depression, shifts in utilization of different energy sources, immune function, and stress responses [12]. Similarly, genes playing roles in protein biosynthesis and fatty acid catabolism with coordinated reduction of transcription of genes playing roles in lipid biosynthesis and carbohydrate catabolism are up-regulated in the liver of Ursus americanus [13]. Although these studies have advanced our understandings of liver physiology in mammals, what happens for gene expression in the liver of hibernating anurans remains unexplored.

The Asiatic toad (Bufo gargarizans) is widely distributed in China, occurring at elevations from 120 to 1500 m [19]. The species is an explosive breeder with a relatively short spawning period (6–24 days) [20], with typical breeding habitats concentrated along the vegetated edges of large, still water bodies. Competition for mating is fierce among males [19,21], and the species experiences a period of hibernation from early-December to mid-February and the mating behaviour occurs as soon as the hibernation period ends. Hence, B. gargarizans is a suitable model for investigating the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying metabolic suppression during the hibernating period. However, no information on gene expression differences among active and hibernating individuals is currently available.

The next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have provided tools to conduct genome-wide studies of non-model organisms with limited genomic resources [14,15,16,17,22]. Amongst other things, they have opened the door to obtain cDNA fragments from transcriptomes with reasonably complete coverage at a low cost [23]. The aim of this study is to compare liver tissue transcriptomes of active and torpid toads with the aid of NGS technology and, in particular, to identify differentially expressed genes that are contributing to the hibernation phenotype. A secondary goal is to compare sex differences in gene expression.

2. Results

2.1. Transcriptome Sequencing, Read Assembly, and Mapping

Transcriptome sequencing produced 20,836,817, 25,678,062, 21,610,351 and 21,463,798 reads from active female, active male, torpid female, and torpid male libraries, respectively (Table 1). The corresponding numbers of total bases generated were 5,240,784,114, 6,460,736,308, 5,426,895,884 and 5,393,246,014 bp, respectively (Table 1). After de novo assembly with Trinity, 27,349 unigenes (length > 500 bp) were recovered, the mean length of these was 849.04 bp. For further analyses of differential gene expression in four library types, the raw reads from the libraries were separately mapped to the assembled contigs (length > 500 bp) that functioned as a transcriptome reference database. Table 1 provides information about the reads mapped to the four libraries, and the mapping rate was 78.22%–80.28%. The distribution of contigs to different length intervals is shown in Figure S1.

Table 1.

Sequencing, assembly, and mapping statistics for samples of active and torpid females and males of Asiatic toads. Mapped ratio refers to percentage of mapped reads in clean reads.

| Active Females | Active Males | Torpid Females | Torpid Males | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing | |||||

| Base number | 5,240,784,114 | 6,460,736,308 | 5,426,895,884 | 5,393,246,014 | |

| Clean read number | 20,836,817 | 25,678,062 | 21,610,351 | 21,463,798 | |

| GC content (%) | 48.33 | 47.42 | 47.47 | 47.60 | |

| Assembly | |||||

| Contigs (>500 bp) | 33,976 | ||||

| Transcript (>500 bp) | 46,560 | ||||

| Unigene (>500 bp) | 27,349 | ||||

| Mapping | |||||

| Mapped ratio (%) | 78.22 | 78.53 | 80.28 | 78.65 |

2.2. Identification and Validation of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

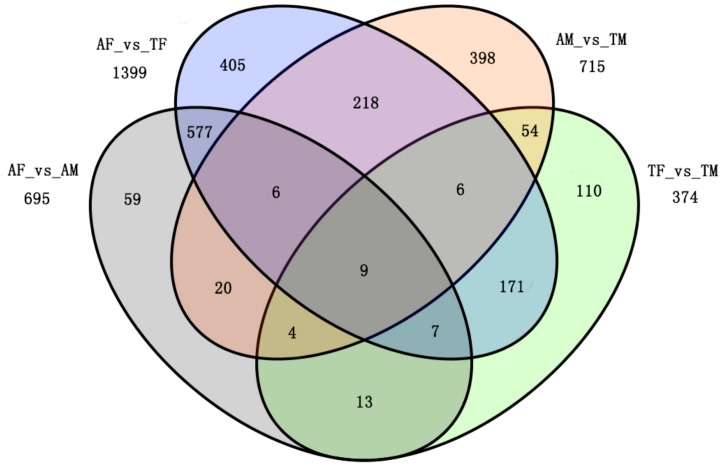

Applying a filter of false discovery rate (FDR) ≤ 0.01 and the absolute value of log2 fold change ≥2, we identified 695 differentially expressed genes between active females and males (AF-vs.-AM), of which 655 genes were down-regulated and 40 genes were up-regulated in the active males (Figure 1 and Table S1).

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing differentially expressed genes among active females (AF), active males (AM), torpid females (TF), and torpid males (TM) for transcripts with log2 fold change ≥2. (AF-vs.-TF: 1399 differentially expressed genes; AM-vs.-TM: 715 differentially expressed genes; AF-vs.-AM: 695differentially expressed genes; TF-vs.-TM: 374 differentially expressed genes).

A total of 1399 differentially expressed genes were identified between active and torpid females (AF-vs.-TF), of which 1004 genes were down-regulated and 395 genes were up-regulated in the torpid females (Figure 1 and Table S1). By comparing 715 differentially expressed genes between active and torpid males (AM-vs.-TM), we found that 378 genes were down-regulated and 337 genes were up-regulated in the torpid males (Figure 1 and Table S1). A total of 374 differentially expressed genes were identified between torpid females and males (TF-vs.-TM) of which 252 genes were down-regulated and 122 genes were up-regulated in the torpid males (Figure 1 and Table S1). Considering that genes highly expressed in liver may play important roles in the physiological functions, the genes with the top 10 reads per kilobase per million mapped reads (RPKM) that were differentially expressed in the four groups are listed in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 2.

The genes with the greatest fold change between active females and males.

| Unigene ID | Nr Annotation | RPKM (Females) | RPKM (Males) | log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated genes | ||||

| c120255.graph_c0 | Hydroxyacid oxidase 1 | 40.157 | 0 | −10.029 |

| c114360.graph_c0 | Aldolase A | 31.087 | 0 | −9.920 |

| c107620.graph_c0 | Photosystem II 10 kDa polypeptide, chloroplast | 68.956 | 0 | −9.676 |

| c119772.graph_c0 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-like | 17.887 | 0 | −9.281 |

| c110474.graph_c0 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein GRP1A-like, partial | 50.161 | 0 | −9.146 |

| c120235.graph_c0 | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1 | 21.024 | 0 | −8.941 |

| c120129.graph_c0 | Chaperone protein ClpB-like, partial | 10.981 | 0 | −8.913 |

| c112955.graph_c0 | Thioredoxin-like isoform X2 | 16.395 | 0 | −8.745 |

| c20631.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC102345338 | 17.348 | 0 | −8.651 |

| c118905.graph_c0 | Alanine aminotransferase 2-like isoform X3 | 10.463 | 0 | −8.560 |

| Up-regulated genes | ||||

| c75071.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC100127559 | 0.115 | 24.499 | 6.773 |

| c111830.graph_c0 | MOSC domain-containing protein 1, mitochondrial-like | 0 | 3.386 | 6.176 |

| c107611.graph_c0 | Keratin | 0.070 | 3.953 | 5.201 |

| c96812.graph_c0 | MGC81526 protein | 0.262 | 11.755 | 5.006 |

| c123079.graph_c0 | Actin-85C-like, partial | 0.465 | 9.786 | 3.484 |

| c123016.graph_c0 | Fast troponin I | 0.279 | 2.091 | 2.529 |

| c109275.graph_c0 | Novel protein similar to human angiopoietin-like ANGPTL | 2.538 | 15.979 | 2.456 |

| c120261.graph_c0 | Choline transporter-like protein 4 | 0.415 | 2.479 | 2.304 |

| c119575.graph_c1 | SLC12A8 cation-chloride cotransporter | 2.349 | 13.111 | 2.295 |

| c100092.graph_c0 | Hemoglobin A chain | 2.404 | 13.614 | 2.287 |

Table 3.

The genes with the greatest fold change between active and torpid females.

| Unigene ID | Nr Annotation | RPKM (Active) | RPKM (Torpid) | log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated genes | ||||

| c120255.graph_c0 | Hydroxyacid oxidase 1 | 40.157 | 0 | −9.328 |

| c114360.graph_c0 | Aldolase A | 31.087 | 0 | −9.219 |

| c107620.graph_c0 | Photosystem II 10 kDa polypeptide, chloroplast | 68.956 | 0 | −8.975 |

| c119772.graph_c0 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-like | 17.887 | 0 | −8.580 |

| c110474.graph_c0 | Glycine-rich RNA-binding protein GRP1A-like, partial | 50.161 | 0 | −8.445 |

| c120235.graph_c0 | NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1 | 21.024 | 0 | −8.241 |

| c120129.graph_c0 | Chaperone protein ClpB-like, partial | 10.981 | 0 | −8.213 |

| c112955.graph_c0 | Thioredoxin-like isoform X2 | 16.395 | 0 | −8.045 |

| c121279.graph_c0 | Transketolase-like | 7.695 | 0 | −7.813 |

| c118687.graph_c0 | Serine hydroxymethyltransferase, mitochondrial isoform X1 | 10.790 | 0 | −7.792 |

| Up-regulated genes | ||||

| c87275.graph_c0 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch 1 | 0.016 | 182.924 | 12.085 |

| c115995.graph_c0 | Myosin heavy chain IIa | 0.020 | 28.514 | 9.528 |

| c122569.graph_c1 | Titin isoform X4 | 0 | 5.402 | 9.170 |

| c87310.graph_c0 | Troponin T | 0.048 | 37.017 | 8.226 |

| c122549.graph_c0 | Obscurin-like | 0.024 | 16.880 | 8.059 |

| c95821.graph_c0 | Telethonin isoformX2 | 0 | 21.439 | 7.848 |

| c26408.graph_c0 | Myosin light chain, phosphorylatable, fast skeletal muscle | 0 | 27.037 | 7.814 |

| c122942.graph_c0 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3 | 0 | 25.036 | 7.756 |

| c74187.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC100036938 | 0 | 8.947 | 7.638 |

| c105949.graph_c0 | Myozenin-1-like | 0 | 10.209 | 7.449 |

Table 4.

The genes with the greatest fold change between active and torpid males.

| Unigene ID | Nr Annotation | RPKM (Active) | RPKM (Torpid) | log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated genes | ||||

| c107611.graph_c0 | Keratin | 3.953 | 0 | −6.375 |

| c75071.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC100127559 | 24.499 | 0.223 | −6.108 |

| c81220.graph_c0 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-beta | 4.027 | 0 | −5.709 |

| c85444.graph_c0 | Tyrosine aminotransferase | 2.588 | 0 | −5.518 |

| c85945.graph_c0 | Tubulin alpha-1A chain-like | 3.081 | 0 | −5.162 |

| c111752.graph_c0 | Long-chain-fatty-acid--CoA ligase ACSBG1 isoform X1 | 12.757 | 0.365 | −5.114 |

| c115272.graph_c0 | L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase, mitochondrial-like | 1.904 | 0 | −4.874 |

| c70612.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC101731022 | 4.881 | 0.140 | −4.810 |

| c80857.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC102222694 | 1.731 | 0 | −4.688 |

| c26374.graph_c0 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 1 | 1.931 | 0 | −4.475 |

| Up-regulated genes | ||||

| c20631.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC102345338 | 0 | 26.152 | 8.184 |

| c122917.graph_c0 | Full = Olfactory protein; Flags: Precursor | 0.165 | 62.383 | 7.752 |

| c114573.graph_c0 | Mucin-5AC-like | 0 | 7.871 | 6.562 |

| c122235.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC101734130, partial | 0.106 | 10.236 | 5.549 |

| c26943.graph_c0 | Stc2 protein | 0.476 | 29.446 | 5.542 |

| c119368.graph_c0 | Zinc finger BED domain-containing protein 1-like isoform X1 | 0.204 | 8.588 | 5.026 |

| c99486.graph_c0 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase DCLK3 | 0.023 | 1.511 | 4.438 |

| c107619.graph_c0 | DnaJ (Hsp40) homolog, subfamily A, member 4, gene 1 | 0.152 | 4.417 | 4.212 |

| c106739.graph_c0 | Sperm-associated antigen 17 | 0.164 | 5.172 | 4.199 |

| c122333.graph_c0 | Heat shock protein 70 | 0.513 | 11.259 | 4.180 |

Table 5.

The genes with the greatest fold change between torpid females and males.

| Unigene ID | Nr Annotation | RPKM (Females) | RPKM (Males) | log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Down-regulated genes | ||||

| c87275.graph_c0 | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch 1 | 182.924 | 0.207 | −9.778 |

| c121033.graph_c0 | Nebulin-related-anchoring protein | 20.819 | 0 | −9.610 |

| c59975.graph_c0 | Cold shock domain protein A, partial | 39.894 | 0.040 | −8.993 |

| c95821.graph_c0 | Telethonin isoformX2 | 21.439 | 0 | −8.384 |

| c122942.graph_c0 | Cysteine and glycine-rich protein 3 (cardiac LIM protein) | 25.036 | 0 | −8.291 |

| c74187.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC100036938 | 8.947 | 0 | −8.173 |

| c122853.graph_c0 | Ribosomal protein L3-like | 39.071 | 0.096 | −8.159 |

| c115995.graph_c0 | Myosin heavy chain IIa | 28.514 | 0.101 | −8.108 |

| c105949.graph_c0 | Myozenin-1-like | 10.209 | 0 | −7.984 |

| c101328.graph_c0 | Tripartite motif containing 54 | 11.995 | 0 | −7.921 |

| Up-regulated genes | ||||

| c122917.graph_c0 | Full = 0l factory protein; Flags: Precursor | 0.064 | 62.383 | 8.801 |

| c111770.graph_c0 | Uncharacterized protein LOC101732866 | 0 | 13.864 | 8.469 |

| c96835.graph_c0 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, cytosolic | 0.228 | 8.825 | 5.009 |

| c123029.graph_c0 | Carboxypeptidase B1 (tissue) precursor | 1.060 | 31.190 | 4.709 |

| c26943.graph_c0 | Stc2 protein | 0.987 | 29.446 | 4.701 |

| c19061.graph_c0 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein 14 | 0 | 3.031 | 4.434 |

| c102557.graph_c0 | Fatty acyl-CoA hydrolase precursor, medium chain-like | 0.246 | 10.881 | 4.379 |

| c89882.graph_c0 | Homeobox protein SIX6-like | 0.152 | 6.725 | 4.379 |

| c106739.graph_c0 | Sperm-associated antigen 17 | 0.191 | 5.172 | 4.245 |

| c125726.graph_c0 | LOW QUALITY PROTEIN: HEAT repeat-containing protein 4 | 0 | 1.640 | 4.233 |

Analysing the differentially expressed genes between active and torpid toads (AF-vs.-TF and AM-vs.-TM), we find that most genes were significantly down-regulated in torpid livers, and the gene with the maximum log2-fold change value (up to −6.44 and −4.13, respectively) was c44660.graph_c0. Moreover, two genes, one involved in fatty acid metabolism (c111752.graph_c0) and another facilitating glucose transportation (c90064.graph_c0), were down-regulated in torpid livers. By contrast, the gene (c122333.graph_c0) encoding a heat shock protein was up-regulated during torpor. The common genes that were differentially expressed in both sexes during the hibernating period were shown in Table S2. By comparing differentially expressed genes between active and torpid females (AF-vs.-TF), the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1 (c120235.graph_c0) was up-regulated during the hibernating period. Likewise, the genes encoding contractile proteins (c87275.graph_c0, c115995.graph_c0 and c122569.graph_c1) were up-regulated in torpid liver.

When comparing differentially expressed genes between females and males in active period (AF-vs.-AM), the down-regulated genes included NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1 (c120235.graph_c0), the gene encoding several key rate-limited regulated enzymes of glycolysis (c114360.graph_c0, c123807.graph_c0, c119772.graph_c0, c123584.graph_c0, c117125.graph_c0) and amino acid transport and metabolism (c104930.graph_c0, c107734.graph_c0, c118687.graph_c0, c118905.graph_c0, c119432.graph_c0, c84432.graph_c0) in active males. When comparing differentially expressed genes between torpid females and torpid males (TF-vs.-TM), the gene encoding contractile proteins (c87275.graph_c0, c115995.graph_c0, and c122569.graph_c1) were down-regulated in torpid males.

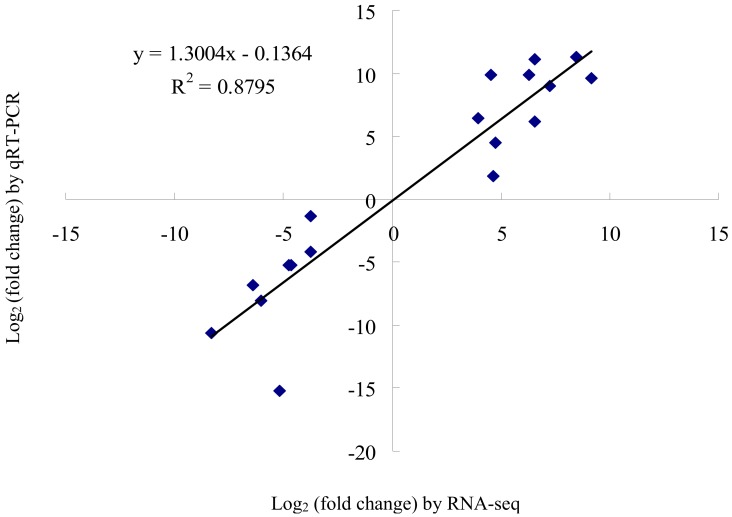

To test the validity of our measurements, we analysed the RNA sequence data of 18 randomly-selected genes with the results from qRT-PCR experiments to detect the relative mRNA expression changes of the selected genes in the four groups (AF-vs.-AM, AF-vs.-TF, AM-vs.-TM, and TF-vs.-TM). The positively and highly significant correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.8795) indicated that the two independent measures of gene expression exhibited similar patterns, testifying the reliability of the RNA-Seq data (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of expression levels measured by RNA-Seq and qRT-PCR for 18 selected transcripts. The two independent measures of gene expression displays a positive correlation.

2.3. Sequence Annotation

BlastX searches were made in various protein databases, and the GenBank NR, Swiss-Prot, PFAM, KEGG, COG, GO, and KOG databases were employed for annotation of the 21,261 unigene sequences (Table 6). Significant matches were found for 5760 (27.09%) unigenes in the COG database, 10,554 (49.64%) in the GO database, and 10,798 (50.78%) in the KEGG database. In the KOG, PFAM, Swiss-prot, and NR databases, 13,424 (63.13%), 15,330 (72.10%), 10,902 (51.27%), and 20,046 (94.28%) significantly matched unigenes were obtained, respectively.

Table 6.

Synopsis of functional annotation of unigenes of the Bufo gargarizans transcriptome. AF, AM, TF, and TM refer to active females, active males, torpid females, and torpid males, respectively.

| Databases | All Annotated Transcripts | 300–1000 (bp) | >1000 (bp) | AF-vs.-AM Annotated Transcripts |

AF-vs.-TF Annotated Transcripts |

AM-vs.-TM Annotated Transcripts |

TF-vs.-TM Annotated Transcripts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COG | 5760 | 1610 | 3686 | 237 | 355 | 104 | 46 |

| GO | 10,554 | 3154 | 6735 | 115 | 329 | 152 | 117 |

| KEGG | 10,798 | 3390 | 6551 | 149 | 380 | 157 | 136 |

| KOG | 13,424 | 4281 | 7939 | 309 | 565 | 191 | 138 |

| PFAM | 15,330 | 4818 | 9370 | 455 | 783 | 266 | 190 |

| Swiss-Prot | 10,902 | 3263 | 6950 | 167 | 421 | 183 | 163 |

| NR | 20,046 | 7283 | 10,699 | 272 | 666 | 335 | 234 |

| All_Annotated | 21,261 | 7940 | 10,787 | 502 | 903 | 342 | 234 |

In the GO annotation, the 10,554 unigenes were allocated to one or more GO terms on the basis of sequence similarity (Table 6). The three main categories of GO annotations were for cellular components (25,872 genes; 36.61%), for molecular function (12,806; 18.12%), and for biological processes (31,985; 45.27%). For cellular components, genes involved in “cell” and “cell part” terms were the most common (Figure S2a–d). In the category of molecular function, the term “binding” was in the highest proportion of annotations, followed by “catalytic activity” (Figure S2a–d). For biological processes, the most frequent GO term was “cellular process”, followed by “single-organism process” and “metabolic process” (Figure S2a–d). The GO analysis revealed a significant enrichment of genes associated with response to stress in the biological processes category: these genes were up-regulated in both sexes during the hibernating period (Table 7).

Table 7.

Genes in significant Gene Ontology categories of the biological processes.

| GO Category | NR Annotation | Unigene ID | AF-vs-AM | AF-vs-TF | AM-vs-TM | TF-vs-TM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log2FC | log2FC | log2FC | log2FC | |||

| Carbohydrate metabolic process (GO:0005975) | Malate dehydrogenase, mitochondrial isoform X1 | c117841 | −8.099 | −7.401 | ||

| Glycolytic process (GO:0006096) | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-like | c119772 | −9.282 | −8.581 | ||

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase, partial | c73032 | −5.337 | −4.657 | |||

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | c102216 | −4.671 | −4.004 | |||

| Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 | c108799 | −5.861 | −5.174 | |||

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | c117125 | −8.378 | −7.679 | |||

| Cellular amino acid metabolic process (GO:0006520) | Glycine dehydrogenase [decarboxylating], mitochondrial | c109713 | −7.590 | −6.893 | ||

| Dopa decarboxylase (aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase) | c21604 | −3.845 | ||||

| Tyrosine aminotransferase | c85444 | −5.009 | −5.519 | |||

| Very long-chain fatty acid metabolic process (GO: 0000038) | Long-chain-fatty-acid-CoA ligase ACSBG1 isoform X1 | c111752 | −4.667 | −5.114 | ||

| Fatty acid metabolic process (GO: 0006631) | Acyl-CoA synthetase family member 2, mitochondrial | c109605 | −2.281 | |||

| Positive regulation of fast-twitch skeletal muscle fiber contraction (GO: 0031448) | ATPase, Ca++ transporting, cardiac muscle, fast twitch 1 | c87275 | 12.086 | −9.778 | ||

| Response to stress (GO: 0006950) | Heat shock protein 90kDa alpha (cytosolic), class A member 1, gene 2 | c88789 | 3.994 | |||

| Cardiovascular heat shock protein | c112677 | 3.869 | ||||

| Heat shock protein 70 | c122333 | 2.441 | 4.181 | |||

| Heat shock 22kDa protein 8 | c107729 | 5.073 | ||||

| Heat shock protein 90 alpha | c107796 | 2.023 | ||||

| Response to heat (GO:0009408) | Heat shock protein beta-1 | c51360 | 6.034 |

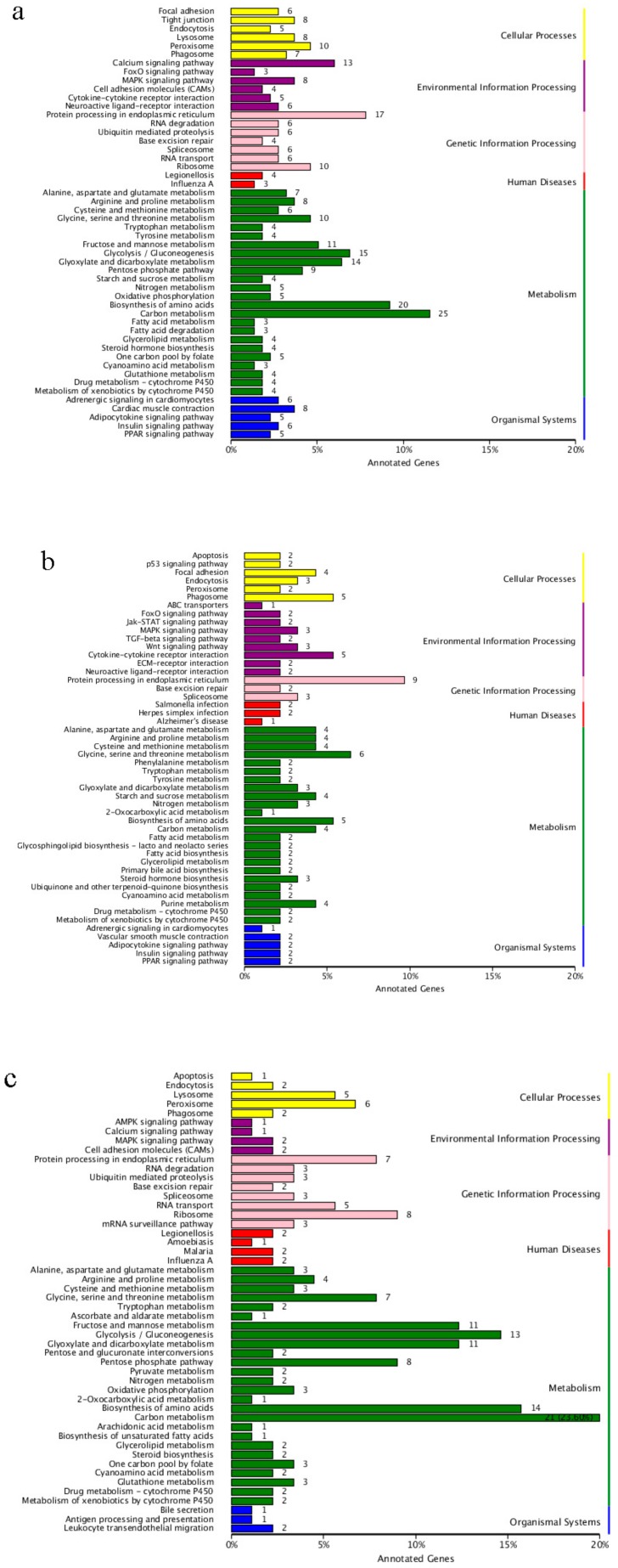

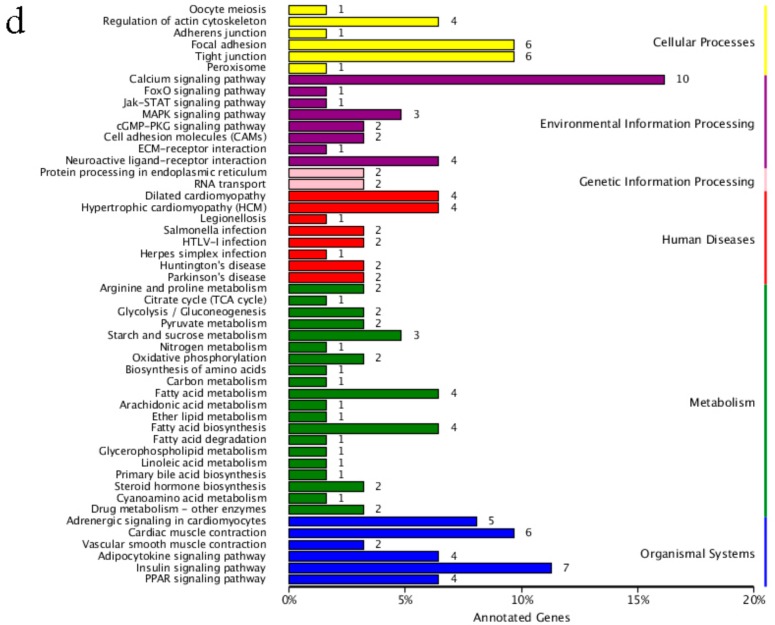

To further explore the biological pathways, the unigene sequences were mapped with the KEGG Pathway Tools. These were classified into six categories: cellular process, environmental information processing, genetic information processing, human diseases, metabolism and organismal systems. This process for active and torpid states assigned 380 unigenes to a total of 143 pathways in females and 157 unigenes to a total of 98 pathways in males, respectively. For metabolism, the genes in the carbon metabolism (ko01200) and biosynthesis of amino acids (ko01230) involved in “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” and “amino acid transport and metabolism” were down-regulated during torpor in both sexes (Figure 3a,b). Meanwhile, genes including the glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ko00010), glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism (ko00630), fructose and mannose metabolism (ko00051), pentose phosphate pathway (ko00030), and fatty acid metabolism (ko01212) involved in “carbohydrate transport and metabolism” and “lipid transport and metabolism” were down-regulated in the torpid females (Figure 3a). In addition, genes in the calcium signalling pathway (ko04020) and cardiac muscle contraction (ko04260) involved in “calcium ion transport” and “muscle contraction” were up-regulated in the torpid females in environmental information processing and organismal systems categories (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes in four comparisons of samples, active female vs. torpid female (a), active male vs. torpid male (b), active female vs. active male (c), and torpid female vs. torpid male (d).

This process for females and males assigned 149 unigenes to a total of 86 pathways in the active state and 136 unigenes to a total of 60 pathways in the torpid state, respectively (Figure 3c,d). For metabolism, the genes involved in the carbon metabolism (ko01200), glycolysis/gluconeogenesis (ko00010), fructose and mannose metabolism (ko00051), pentose phosphate pathway (ko00030) and biosynthesis of amino acids (ko01230) were down-regulated in active males (Figure 3c). For environmental information processing and organismal systems, the genes including the calcium signalling pathway (ko04020) and cardiac muscle contraction (ko04260) involved in “calcium ion transport” and “muscle contraction” were down-regulated in the torpid males (Figure 3d).

2.4. Body Mass and Fat-Body Mass

Body mass of the torpid toads was significantly lower than that of active ones (two-way ANOVA: F1,36 = 5.069, p = 0.031; Tables S3 and S4). Fat-body mass in the torpid toads was significantly lower than in active ones (two-way ANOVA: F1,36 = 5.051, p = 0.031; Tables S3 and S4).

3. Discussion

3.1. Metabolic Enzymes

As an important strategy for energy conservation, reduced metabolic rate plays a critical role for survival in harsh winter in many mammals [4]. The minimum metabolic rate during torpor can be as low as 4.3% of the basal metabolic rate [6], enabling hibernators to save 90% of normal energy usage [24]. How do the hibernating animals mediate a low level of their metabolic rate? Changed traits and levels of gene expression permit them to display a diversity of phenotypes even with a common genotype [1]. The variations of physiology in an organism shifting between active and torpid states may result from the changed expression of genes encoding proteins where that specific functions can be served in physiologcal process [12]. We found that most of the genes involved in metabolic pathways were down-regulated during torpor. For example, the genes were down-regulated and were likely to play a crucial role in energy metabolism by encoding an important enzyme (NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1). This enzyme takes part in an extra-hepatic P450 electron transport pathway and contributes to the accumulation of hepatic lipids [25,26]. The above-mentioned example suggests that transcriptional changes resulted in metabolic adjustment between active and torpor states. Similarly, the results from torpid Rhinolophus ferrumequinum reveal co-down-regulation of genes involved in the glycolytic pathway playing a central role in metabolic suppression during torpor [12,14].

Amphibians, like other animals, undergo critical shifts in their energy utilization pathways during torpor, specifically switching from carbohydrate to fat-based metabolism [1]. For B. gargarizans, the fat mass is highest in July and lowest in March, and lipids are the primary energy source during the hibernating period [27], as in most torpid animals [28]. In our material, fat-body mass in torpid toads was significantly lower than in active ones (Tables S3 and S4), suggesting active utilization of fat-bodies during the hibernating period.

By comparing the gene expression between active and torpid females (AF-vs.-TF), we found that genes encoding several key rate-limited regulated enzymes of glycolysis, lipid transport and metabolism and protein synthesis (c21604.graph_c0, c85444.graph_c0, and c109713.graph_c0) were expressed at lower levels during torpor. Likewise, the five genes (c116341.graph_c0, c113894.graph_c0, c115957.graph_c0, c90064.graph_c0, and c115215.graph_c0) facilitating glucose transportation were down-expressed in torpid females. Similarly, we also found that genes encoding facilitated glucose transporter and amino acid metabolic processes were down-expressed in torpid males when compared to active males (AM-vs.-TM). These findings align with the results of Xiao et al. [12] who find that some differentially expressed genes are associated with the glycolytic pathway and lipid metabolism in the liver between active and torpid R. ferrumequinum.

NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1 (c120235.graph_c0) and several genes encoding several key rate-limited regulated enzymes of glycolysis (c114360.graph_c0, c119772.graph_c0, c117125.graph_c0) were down-regulated in active males as compared to active females (AF-vs.-AM). As the basal metabolic rate (BMR) increases with body mass and body surface area [29,30], and females are the larger sex in B. gargarizans, we would expect females to exhibit higher BMR than males. Moreover, the BMR in females is expected to be elevated by pregnancy [31,32]. In fact, torpid females are carrying developing eggs during the hibernating period, thus, in order to guarantee the normal development of their eggs, the females are not allowed to decrease their metabolism to the level which is similar to that of males.

3.2. Contractile Proteins

It has been shown that titin, serving as a molecular spring, results in elasticity and passive muscle stiffness [33] which is likely to play a critical role in mediating heart function at extremely low temperatures. Hence, titin is an important determinant in diastolic filling of heart. There is evidence that, for Citellus undulates, the 3400-kDa isoform of titin is expressed predominantly in both skeletal and cardiac muscle during the hibernating period [34]. In this study, the genes encoding contractile proteins (c87275.graph_c0, c115995.graph_c0, c122569.graph_c1) were up-regulated in torpid females as compared to active females (AF-vs.-TF). In line with our findings, the expression of genes in the heart altering contractility and Ca2+ handling are higher in the hibernating season than in the active season by the thirteen-lined ground squirrel (Spermophilus tridecemlineatus) [35].

The genes encoding contractile proteins (c87275.graph_c0, c115995.graph_c0, and c122569.graph_c1) were down-expressed in torpid males as compared torpid females (TF-vs.-TM). Blackburn and Calloway suggest that oxygen uptake increases after exercise for pregnant woman [31]. In contrast to males, females continue their reproductive investment during the hibernating period by developing eggs. This suggests that torpid females may be forced to increase their oxygen uptake during the hibernating period more than torpid males and, hence, also up-regulation of genes involved in the production of contractile proteins.

3.3. Anti-Stress Response

It has been found by several studies that, during the hibernating period, protein synthesis and proteolysis are often in a state of being suppressed [4,36]. The elevated expression of multi-family heat shock protein (HSP) genes in this study suggests that the preservation of the proteome from protein folding during torpor is a function that is preserved even during torpor. Stresses, such as hypoxia or ischemia, induce protein mis-folding during torpor, which also occurs in the pathological conditions related to neurodegenerative diseases and brain injury [37,38,39]. In the current study, we found many HSP genes were up-regulated during torpor (cf. comparisons: AF-vs.-TF and AM-vs.-TM), suggesting that elevated expression of HSP may play a specific role in protein homeostasis to maintain tissue-specific functions. This inference is supported by the fact that the up-regulation of HSP genes have also been reported in studies of hibernating mammals [40,41,42].

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Animals and Sample Preparation

The specimens used in this study were collected with permission (# 17001) from the Ethical Committee for Animal experiments in China West Normal University, and the experimental protocols complied with the current laws of China concerning animal experimentation (Approval date: 20 September 2015). A total of 100 individuals (50 females and 50 males) were caught in mid-October 2015 from Nanchong (30°49′ N, 106°03′ E, 251 metre above sea level) in Sichuan Province, China. All individuals were kept in a pond (length × width × depth: 3 m × 2 m × 1 m). After 48 h, we randomly selected 10 active females and 10 active males. Individuals were transferred to the laboratory and kept individually in a rectangular tank (0.5 m × 0.4 m × 0.4 m; Chahua, Fujian, China), and then killed by single-pithing [43,44,45,46,47]. We measured the body size (snout-vent length: SVL) of each individual to the nearest 0.01 mm with a calliper (SHANGGOMG, Shanghai, China). Body mass and fat-body mass were measured to the nearest 0.1 mg with an electronic balance (HANGPING FA2204B, Shanghai, China). In late December 2015, we randomly captured 20 individuals (10 torpid females and 10 torpid males) from the pond where all individuals had been hibernating for 40 days. We anesthetized all individuals and killed them using single-pithing [48,49,50,51,52,53]. We promptly performed surgical procedures to protect RNA from degradation. The livers from active and torpid toads were rapidly excised, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and then stored at −80 °C until processing for RNA isolation.

4.2. RNA Isolation and cDNA Library Construction

Total RNA in livers for all individuals was extracted using Trizol (Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA). RNA concentration was then measured with the use of a NanoDrop 2000 system (Thermo, Wilmington, SD, USA). We assessed RNA integrity using the RNA Nano 6000 Assay Kit of the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Biomarker Technologies Corporation (Beijing, China) used an Illumina Genome Analyzer II platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to perform the deep sequencing of Total RNA. A total amount of 1 μg RNA per sample was provided for input material for the RNA sample preparations. We used NEBNext UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, USA) to generate sequencing libraries and added index codes to attribute sequences to each sample. Briefly, we used poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads to purify mRNA from total RNA. Fragmentation was conducted using divalent cations under increased temperature in NEBNext first strand synthesis reaction buffer (5×). First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using random hexamer primer and M-MuLV reverse transcriptase. Second strand cDNA was subsequently synthesized using DNA polymerase I and RNase H. Remained overhangs were transferred to blunt ends through exonuclease/polymerase activities. We ligated the NEBNext adaptor with a hairpin loop structure to prepare for hybridization after adenylation of 3′ ends of DNA fragments. The library fragments were purified using an AMPure XP system (Beckman Coulter, Beverly, MA, USA) to choose cDNA fragments of, preferentially, 240 bp in length. We used the 3 μL USER enzyme (NEB, USA) with size-selected, adaptor-ligated cDNA at 37 °C for 15 min followed by 5 min at 95 °C before PCR. We performed the PCR with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase, Universal PCR primers and Index (X) Primer. Finally, we used an AMPure XP system to purify PCR products and assessed library quality using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. We constructed four cDNA libraries (active females (AF), active males (AM), torpid females (TF), and torpid males(TM)) with the Super-Script® Double-Stranded cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, cat. no. 11917-010, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Raw sequence data generated by Illumina pipeline were deposited into Short Read Archive (SRA) database of NCBI with the accession no. SRR5344011 (active females), no. SRR5344010 (active males), no. SRR5344009 (torpid females), and no. SRR5344008 (torpid males).

4.3. Transcriptome Sequencing and Assembly

Sequencing was performed via a paired-end 125 cycle rapid run on two lanes of the Illumina HiSeq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), generating more than 89.59 million pairs of reads as desired. We separately assembled de novo from transcriptomes using Trinity [54]. The left files (read1 files) and right files (read2 files) from all libraries/samples were pooled into one large left.fq file and one large right.fq file, respectively. Transcriptome assembly was accomplished on the basis of both the left.fq and right.fq with min_kmer_cov set to 2 on the basis of default, and all other parameters set to default. In particular, long fragments without N (named contigs) initially consisted of clean reads with a certain overlap length. We used the TGICL software [55] to cluster related contigs in order to produce unigenes (without N) that cannot be extended on either end, and we removed redundancies to acquire non-redundant unigenes. We then separately mapped raw reads from four libraries to pre-assembled contigs (length > 500) using BWA v0.6.1-r104 [56,57], with two critical parameters: less than five mismatches and no gap. High-quality clean reads were obtained by removing the adaptor sequences, duplicated sequences, ambiguous reads (‘N’), and low-quality reads (including the removal of ‘N’ ratio greater than 10% of reads, the base number of the quality value Q ≤ 10 is removed by reads of more than 50% of the entire read.).

4.4. Gene Annotation

To retrieve protein functional annotations on the baisis of sequence similarity, we searched the unigene sequences of the four groups by BLASTX against the NCBI nonredundant (NR), Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Cluster of Orthologous Group of proteins (COG/KOG), Swiss-Prot protein (Swiss-Prot), and Protein family (PFAM) databases (E-value ≤ 1 × 10−5). We determined the direction of the unigene sequences using high-priority databases. We then decided the sequence direction of the unigenes that could not be aligned to any of the above databases using the ESTScan software [58]. We assigned GO terms to each sequence annotated using BLASTX against the NR database on the basis of the Blast2GO program with the E-value threshold of 1 × 10−5 for further functional categorization. The distribution of the GO functional classification of the unigenes was plotted by the Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot (WEGO) software [59]. We analysed inner-cell metabolic pathways and the related gene function using BLASTX through assigning the unigenes to KEGG pathway annotations.

4.5. Analysis of the Functional Enrichment of DEGs

Read counts of every gene were estimated through using RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization (RSEM) [60] which was nested in the Trinity package [54]. Then, we calculated FPKM (fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped) values to normalize the read counts so that the gene expression difference between two different samples was able to be compared. Here, we detected differentially expressed genes by using EdgeR method [61]. On the basis of applying Benjamini-Hochberg correction [62] for multiple test, FDR ≤ 0.01 and the absolute value of log2 fold change ≥2 were set as the thresholds for the significance of the gene expression difference between the samples.

4.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

To test the validity of our measurements, qRT-PCR was performed to detect the relative messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of 18 randomly selected genes which were down-regulated (c106287.graph_c0, c111514.graph_c0) or up-regulated (c100636. graph_c0, c102204.graph_c0) between active females and active males (AF-vs.-AM) in the transcriptome sequencing, down-regulated (c80857.graph_c0) or up-regulated (c122853.graph_c0, c122834.graph_c0) between active females and torpid females (AF-vs.-TF), down-regulated (c85945.graph_c0, c76918.graph_c0) or up-regulated (c114573.graph_c0, c109992.graph_c1, c20664.graph_c0) between active males and torpid males (AM-vs.-TM), down-regulated (c122942.graph_c0, c77297.graph_c0, c101480. graph_c0) or up-regulated (c111770.graph_c0, c102232.graph_c1, c123340.graph_c0) between torpid females and torpid males (TF-vs.-TM). The α-actin gene was selected as the house-keeping gene [63]. The primer pairs for the 18 genes and house-keeping α-actin gene for B. gargarizans are listed in Table S5, including their sequences, and product lengths. Messenger RNA samples from the livers of 40 individuals (10 active females, 10 active males, 10 torpid females, 10 torpid males), were converted to cDNA templates. qRT-PCRs were performed using a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China) and an automatic threshold calculated by the StepOne software v2.1 (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Shanghai, China). For each sample, three technical replicates of each PCR reaction were run. For each target gene, reactions of all biological replicates (i.e., all samples) in the active and torpid state (or female and male) were completed on one plate to eliminate inter-run heterogenity. Each 20 μL PCR mixture reaction contained 10 μL SybrGreen qPCR Master Mix, 7.2 μL ddH2O, 2 μL cDNA template and 0.4 μL of each primer. PCRs were carried out using the following parameters: 95 °C × 3 min, 45 cycles of 95 °C × 7 s, 57 °C × 10 s, 72 °C × 15 s. The standard deviation between two reactions of each sample was less than 0.5, which means the CT (crossing threshold) value of each sample was used in further analyses. The relative quantity was calculated by using 2−ΔΔCT method [64].

5. Conclusions

To sum up, we used the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform to sequence liver transcriptomes of active and torpid B. gargarizans to gain insights into changes in gene expression patterns in hibernating female and male toads. We discovered that 395 genes, mainly involved in stress responses, including contractile proteins, were significantly up-regulated, whereas 1004 genes mainly involved in metabolic depression and shifts in energy utilization were down-regulated in torpid females. Similar patterns were recoded in comparison of torpid and active males but, in general, fewer genes were markedly expressed in males than females. More specifically, 695 genes were differentially expressed between active females and active males: of these expression of 655 genes were significantly down-regulated in activemales. Only 374 differentially expressed genes were identified between torpid females and males, but again, most of these (252 genes) were significantly down-regulated in torpid males. The genes encoding an important enzyme (NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase isoform X1) were down-regulated so as to achieve the accumulation of hepatic lipids, thus, the metabolic rate would be reduced and the survival of poikilotherms living in tough winter conditions would be enhanced. However, the metabolic rate of females was higher than that of males as they were carrying developing eggs during the hibernating period. Moreover, the up-regulation of genes encoding contractile proteins might be caused by the increasing demands of oxygen for torpid toads during hibernation. Further, many HSP were up-regulated in torpor (cf. comparisons: AF-vs.-TF and AM-vs.-TM), indicating that HSP may be responsible for maintaining tissue-specific functions via the protein homeostasis pathway during torpor. Totally, the findings suggest that levels and patterns of gene expression in liver of anurans are significantly influenced by torpor, and that there are significant differences in gene expression between males and females.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Zhiping Mi, Chunlan Mai and Jing Liao for their help for sampling in fieldwork and Thomas Conner for improving the English.

Abbreviations

| AF | Active females |

| AM | Active males |

| TF | Torpid females |

| TM | Torpid males |

| FPKM | Fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped |

| BMR | Basal metabolic rate |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| RPKM | Reads Per Kilobase per Million mapped reads |

| WEGO | Web Gene Ontology Annotation Plot |

| RSEM | RNA-Seq by Expectation Maximization |

| CT | Crossing threshold |

| NGS | Next-generation sequencing |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| HSP | Heat shock protein |

| NR | NCBI nonredundant |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| COG | Cluster of Orthologous Group of proteins |

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/8/2363/s1.

Author Contributions

W.B.L. conceived and designed the experiments; L.J. and J.P.Y. performed the tissue collection and RNA isolation; L.J. and W.B.L. performed the data analysis; L.J. performed the quantitative real-time PCR experiments; L.J., W.B.L., and J.M. wrote the manuscript drafts; Z.J.Y. and J.M. edited the manuscript; and all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Financial support was provided by the National Natural Sciences Foundation of China (31471996 to Wen-Bo Liao), Sichuan Province Outstanding Youth Academic Technology Leaders Program (2013JQ0016 to Wen-Bo Liao), Sichuan Province Department of Education Innovation Team Project (Grant #15TD0019 to Wen-Bo Liao), and the Academy of Finland (129662 and 134728 to Juha Merilä).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Carey H.V., Andrews M.T., Martin S.L. Mammalian hibernation: Cellular and molecular responses to depressed metabolism and low temperature. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:1153–1181. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00008.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roots C. Hibernation. Greenwood Press; Westport, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Geiser F. Hibernation. Curr. Biol. 2013;23:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storey K.B., Storey J.M. Metabolic rate depression in animals: Transcriptional and translational controls. Biol. Rev. 2004;79:207–233. doi: 10.1017/S1464793103006195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiser F. Metabolic rate and body temperature reduction during hibernation and daily torpor. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:239–274. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032102.115105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruf T., Geiser F. Daily torpor and hibernation in birds and mammals. Biol. Rev. 2015;90:891–926. doi: 10.1111/brv.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abe A.S. Estivation in South-American amphibians and reptiles. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 1995;28:1241–1247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kayes S.M., Cramp R.L., Franklin C.E. Metabolic depression during aestivation in Cyclorana alboguttata. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 2009;154:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Beurden E.K. Energy metabolism of dormant Australian water holding frogs (Cyclorana platycephalus) Copeia. 1980;4:787–799. doi: 10.2307/1444458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlquist D.A., Nelson R.A., Steiger D.L., Jones J.D., Ellefson R.D. Glycerol metabolism in the hibernating black bear. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 1984;155:75–79. doi: 10.1007/BF00688794. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen P., Leray V., Diez M., Serisier S., Bloc’h J.L., Siliart B., Dumon H. Liver lipid metabolism. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. 2008;92:272–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2007.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiao Y., Wu Y., Sun K., Wang H., Zhang B., Song S., Du Z., Jiang T., Shi L., Wang L., et al. Differential expression of hepatic genes of the greater horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) between the summer active and winter torpid states. PLoS ONE. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedorov V.B., Goropashnaya A.V., Toien O., Stewart N.C., Chang C., Wang H., Yan J., Showe L.C., Showe M.K., Barnes B.M. Modulation of gene expression in heart and liver of hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus) BMC Genom. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lei M., Dong D., Mu S., Pan Y.H., Zhang S. Comparison of brain transcriptome of the Greater Horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum) in active and torpid Episodes. PLoS ONE. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan J., Burman A., Nichols C., Alila L., Showe L.C., Showe M.K., Boyer B.B., Bames B.M., Marr T.G. Detection of differential gene expression in brown adipose tissue of hibernating arctic ground squirrels with mouse microarrays. Physiol. Genom. 2006;25:346–353. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00260.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fedorov V.B., Goropashnaya A.V., Toien O., Stewart N.C., Gracey A.Y., Chang C., Qin S., Pertea G., Quackenbush J., Showe L.C., et al. Elevated expression of protein biosynthesis genes in liver and muscle of hibernating black bears (Ursus americanus) Physiol. Genom. 2009;37:108–118. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90398.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams D.R., Epperson L.E., Li W., Hughes M.A., Taylor R., Rogers J., Martin S.L., Cossins A.R., Gracey A.Y. Seasonally hibernating phenotype assessed through transcript screening. Physiol. Genom. 2005;24:13–22. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00301.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srere H.K., Wang L.C., Martin S.L. Central role for differential gene expression in mammalian hibernation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:7119–7123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fei L., Ye C.Y. The Colour Handbook of the Amphibians of Sichuan. Chinese Forestry Publishing House; Beijing, China: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu T.L., Lu X. Mating pattern variability across three Asiatic toad (Bufo gargarizans gargarizans) populations. North West J. Zool. 2012;8:241–246. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao W.B., Liu W.C., Merilä J. Andrew meets Rensch: Sexual size dimorphism and the inverse of Rensch’s rule in Andrew’s toad (Bufo andrewsi) Oecologia. 2015;177:389–399. doi: 10.1007/s00442-014-3147-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang Z.J., Peng Z.S., Wei S.H., Liao M.L., Yu Y., Jang Z.Y. Pistillody mutant reveals key insights into stamen and pistil development in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) BMC Genom. 2015;16 doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1453-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Z., Gerstein M., Snyder M. RNA-Seq: A revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang L.C., Lee T., Fregley M., Blatteis C. Torpor and hibernation in mammals: Metabolic, physiological, and biochemical adaptations. In: Pappenheimer J.R., Fregly M.J., Blatties C.M., editors. Handbook of Physiology: Environmental Physiology. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen A.L., O’Leary K.A., Kasper C.B. Association of multiple developmental defects and embryonic lethality with loss of microsomal NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:6536–6541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gu J., Weng Y., Zhang Q.Y., Cui H., Behr M., Wu L., Yang W., Zhang L., Ding X. Liver-specific deletion of the NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase gene: Impact on plasma cholesterol homeostasis and the function and regulation of microsomal cytochrome P450 and heme oxygenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25895–25901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303125200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou H., Sun J. The seasonal rhythm of fat content in fat-body of Chinese toad. Sichuan J. Zool. 1997;16:95. [Google Scholar]

- 28.South F., House W. Energy metabolism in hibernation. In: Fisher K., Dawe A., Lyman C., Schonbaum E., editors. Mammalian Hibernation III. Oliver & Boyd; Edinburgh, UK: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benedict F. Factors affecting basal metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 1915;20 doi: 10.1001/jama.1936.02770310035014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kleiber M. The Fire of Life: An Introduction to Animal Energetics. Huntington; New York, NY, USA: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blackburn M.W., Calloway D.H. Basal metabolic rate and work energy expenditure of mature, pregnant women. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1976;69:24–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.King J.C. Physiology of pregnancy and nutrient metabolism. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;71:1218–1225. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/71.5.1218s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Granzier H.L., Labeit S. The giant protein titin: A major player in myocardial mechanics, signaling, and disease. Circ. Res. 2004;94:284–295. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000117769.88862.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vikhliantsev I.M., Podlubnaia Z.A. Adaptive behavior of titin isoforms from skeletal and cardiac muscles of ground squirrels (Citellus undulatus) during hibernation. Biofizika. 2004;49:430–435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brauch K.M., Dhruv N.D., Hanse E.A., Andrews M.T. Digital transcriptome analysis indicates adaptive mechanisms in the heart of a hibernating mammal. Physiol. Genom. 2005;23:227–234. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00076.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frerichs K.U., Smith C.B., Brenner M., DeGracia D.J., Krause G.S., Laura M., Thomas E.D., John M.H. Suppression of protein synthesis in brain during hibernation involves inhibition of protein initiation and elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:14511–14516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown I.R. Heat shock proteins and protection of the nervous system. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007;1113:147–158. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Massa S.M., Longo F.M., Zuo J., Wang S., Chen J., Sharp F.R. Cloning of rat grp75, an hsp70-family member, and its expression in normal and ischemic brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 1995;40:807–819. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490400612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu L., Voloboueva L.A., Ouyang Y., Emery J.F., Giffard R.G. Overexpression of mitochondrial Hsp70/Hsp75 in rat brain protects mitochondria, reduces oxidative stress, and protects from focal ischemia. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:365–374. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storey K.B. Metabolic regulation in mammalian hibernation: Enzyme and protein adaptations. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A. 1997;118:1115–1124. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9629(97)00238-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eddy S.F., McNally J.D., Storey K.B. Up-regulation of a thioredoxin peroxidase-like protein, proliferation-associated gene, in hibernating bats. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;435:103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee K., Park J.Y., Yoo W., Gwag T., Lee J.W., Byun M.W., Choi I. Overcoming muscle atrophy in a hibernating mammal despite prolonged disuse in dormancy: Proteomic and molecular assessment. J. Cell. Biochem. 2008;104:642–656. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liao W.B., Lou S.L., Zeng Y., Kotrschal A. Large brains, small guts: The expensive tissue hypothesis supported in anurans. Am. Nat. 2016;188:693–700. doi: 10.1086/688894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo Y., Zhong M.J., Huang Y., Li F., Liao W.B., Kotrschal A. Seasonality and brain size are negatively associated in frogs: Evidence for the expensive brain framework. Sci. Rep. 2017;7 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16921-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lüpold S., Jin L., Liao W.B. Population density and structure drive differential investment in pre- and postmating sexual traits in frogs. Evolution. 2017;71:1686–1699. doi: 10.1111/evo.13246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liao W.B., Huang Y., Zhong M.J., Zeng Y., Luo Y., Lüpold S. Ejaculate evolution in external fertilizers: Influenced by sperm competition or sperm limitation? Evolution. 2018;72:4–17. doi: 10.1111/evo.13372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu X., Zhong M.J., Li D.Y., Jin L., Liao W.B., Kotrschal A. Large-brained frogs mature later and live longer. Evolution. 2018;72:1174–1183. doi: 10.1111/evo.13478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeng Y., Lou S.L., Liao W.B., Jehle R., Kotrschal A. Sexual selection impacts brain anatomy in frogs and toads. Ecol. Evol. 2016;6:7070–7079. doi: 10.1002/ece3.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mai C.L., Liao J., Zhao L., Liu S.M., Liao W.B. Brain size evolution in the frog Fejervarya limnocharis does neither support the cognitive buffer nor the expensive brain framework hypothesis. J. Zool. 2017;302:63–72. doi: 10.1111/jzo.12432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin L., Yang S.N., Liao W.B., Lüpold S. Altitude underlies variation in the mating system, somatic condition and investment in reproductive traits in male Asian grass frogs (Fejervarya limnocharis) Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2016;70:1197–1208. doi: 10.1007/s00265-016-2128-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liao W.B., Lou S.L., Zeng Y., Merilä J. Evolution of anuran brains: Disentangling ecological and phylogenetic sources of variation. J. Evol. Biol. 2015;28:1986–1996. doi: 10.1111/jeb.12714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang T., Luo Y., Huang C.H., Liao W.B., Huang W.C. Variation in somatic condition and testes mass in Feirana quadranus along an altitudinal gradient. Anim. Biol. 2018;68:277–288. doi: 10.1163/15707563-17000142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang S.N., Feng H., Jin L., Zhou Z.M., Liao W.B. No evidence for the expensive-tissue hypothesis in Fejervarya limnocharis. Anim. Biol. 2018;68:265–276. doi: 10.1163/15707563-17000094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grabherr M.G., Haas B.J., Yassour M., Levin J.Z., Thompson D.A., Amit I., Adiconis X., Fan L., Raychowdhury R., Zeng Q.D., et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:644–652. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pertea G., Huang X.Q., Liang F., Antonescu V., Sultana R., Karamycheva S., Lee Y., White J., Cheung F., Parvizi B., et al. TIGR Gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): A software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Iseli C., Jongeneel C.V., Bucher P. ESTScan: A program for detecting, evaluating, and reconstructing potential coding regions in EST sequences. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell. Syst. Mol. Biol. 1999;99:138–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ye J., Fang L., Zheng H., Zhang Y., Chen J., Zhang Z., Wang J., Li S., Li R., Bolund L., et al. WEGO: A web tool for plotting GO annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:293–297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li B., Dewey C.N. RSEM: Accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robinson M.D., McCarthy D.J., Smyth G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. B. 1995:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang M., Chai L., Zhao H., Wu M., Wang H. Effects of nitrate on metamorphosis, thyroid and iodothyronine deiodinases expression in Bufo gargarizans larvae. Chemosphere. 2015;139:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.