Abstract

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is an efficacious treatment for alcohol use disorders (AUD). MI is thought to enhance motivation via a combination of two therapeutic strategies or active ingredients: one relational and one directional. The primary aim of this study was to examine MI’s hypothesized active ingredients using a dismantling design. Problem drinkers (N=139) seeking treatment were randomized to one of three conditions: MI, relational MI without the directional elements labeled spirit-only MI (SOMI) or a non-therapy control (NTC) condition and followed for eight weeks. Those assigned to MI or SOMI received four sessions of treatment over eight weeks. All participants significantly reduced their drinking by week 8, but reductions were equivalent across conditions. The hypothesis that baseline motivation would significantly moderate condition effects on outcome was generally not supported. Failure to find support for MI𠄉s hypothesized active ingredients is discussed in the context of the strengths and limitations of the study design.

Keywords: motivational interviewing, drinking, readiness to change, active ingredients, moderated drinking

Introduction

Motivational Interviewing (MI) is among the best validated and most widely disseminated of all psychosocial interventions for alcohol use disorders (AUD; Miller & Rose, 2009.) MI is unique among psychosocial interventions in focusing primarily on increasing motivation. Lack of strong motivation to change behavior is thought to be a key factor in addictive illness and in the maintenance of other health behavior problems. MI has been widely and successfully applied to other problem behaviors, further supporting the core hypothesis that MI has specific effects on increasing motivation (Miller & Rose, 2009). While there is strong evidence for the efficacy of MI, much less is known about how MI works, including whether components of MI increase motivation to change.

Gaining a better understanding of the mechanisms that underlie MI efficacy is important for several reasons. First, MI, like other demonstrated effective AUD treatments, is only modestly effective. About half of individuals fail to respond. Without gaining a better understanding of how MI works, it is unlikely we can improve it. Second, MI like most interventions has multiple components. Without a clear understanding of which components are most important, it is difficult to disseminate MI to the clinical practice community.

MI’s Theory of Change

MI is thought to enhance motivation via the combination of two therapy approaches or active ingredients: one client-centered and the other directional or strategic (Miller & Rose, 2009). Non-directive, client-centered approaches focus on conveying three critical conditions: accurate empathy, unconditional positive regard, and genuineness (Rogers, 1959). Accurate empathy involves skillful reflective listening that helps clarify and amplify the person’s experiences, without imposing the therapist’s interpretation or direction on the material. Positive regard and genuineness refer to the assumption that individuals possess the capacity for change and positive growth and that the role of the therapist is to help the individual explore and discover this capacity. Overall, client-centered elements create an atmosphere of acceptance and safety that allow for exploration and change to occur.

MI combines client-centered strategies with a very specific and well-articulated set of directional or technical strategies designed to strengthen personal motivation and commitment to behavior change via the differential evocation and reinforcement of change talk (Miller & Rollnick 2002; 2012). In their review of the MI literature, Miller and Rose (2009) note that each of MI’s active ingredients operates to facilitate behavior change. First, client-centered or relational factors, such as therapist empathy, facilitate behavior change. Second, the proficient use of MI’s directional strategies increases change talk and reduces sustain talk, which, in turn lead to improved outcomes. Miller and Rose labeled this latter formulation the technical hypothesis of MI.

Empirical Research on MI’s Theory of Change

A growing number of studies have examined MI’s relational and technical theories of change. Reviews of this literature suggest inconsistent or incomplete support for both theories (Apodaca & Longabaugh, 2009; Longabaugh, Magill, Morgenstern, & Huebner, 2013; Magill et al., 2014). For example, three studies found that therapist empathy predicted better outcomes in MI (Gaume, Gmel, Faouzi, & Daeppen, 2009; McNally, Palfai, & Kahler, 2005; Wiprovnick, Kuerbis, & Morgenstern, 2015); however, in their comprehensive review, Apodaca and Longabaugh (2009) found limited evidence to support the proposition that MI spirit was an active ingredient in MI.

A promising line of research has examined MI’s technical hypothesis by testing the strength of association between therapist MI consistent behaviors and client speech during MI therapy sessions and then relating these to drinking outcomes (Gaume, Bertholet, & Daeppen, 2016; Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005; Vader, Walters, Prabhu, Houck, & Field, 2010). Magill and colleagues (2014) conducted a meta-analysis of studies that examined these associations, but consistent with earlier reviews found incomplete support for the hypothesized causal chain. For example, while therapist consistent behaviors significantly increased change talk, change talk did not significantly predict drinking outcomes.

Moving Beyond Association in Testing MI Change Theory

One limitation of the empirical work summarized above is that it, for the most part, relies on tests of the strength of association between variables in an attempt to support a causal hypothesis. Significant associations may be due to a third unmeasured factor. For example, it may be that higher client motivation at baseline might facilitate greater during session MI fidelity, as well as better outcomes. Two prior studies dismantled MI into its component approaches in an attempt to experimentally examine whether MI’s relational and directional components contribute to reduced drinking (Morgenstern et al., 2012; Sellman, Sullivan, Dore, Adamson, & MacEwan, 2001).

Sellman and colleagues (2001) recruited problem drinkers entering an alcohol treatment clinic. All participants received a feedback and education session that was attended by a significant other. Participants were then assigned to MI, a non-directive listening condition NDL), or to a no further intervention control. At a six-month follow-up, a significantly lower percentage of MI participants drank 10 or more drinks on six occasions relative to the other conditions. There were no significant differences on the other five outcomes measures, although outcomes generally favored MI.

Although the Sellman et al. study was novel, there were a number of design limitations. For example, many of the methods now employed to define and measure the fidelity of the treatment conditions were absent, making it unclear whether the NDL condition accurately conveyed MI spirit or whether participants viewed NDL as a credible treatment for alcohol problems. In addition, the study did not employ standard alcohol treatment outcome measures making it difficult to compare the study findings with others in the field.

Our group conducted a second study designed, in part, to address these limitations (Morgenstern et al., 2012). We dismantled MI into its relational and directional elements to create to two MI therapy conditions. One MI condition (labeled Spirit-Only MI or SOMI) consisted of the relational or nondirective elements of MI including use of reflective listening skills, a general atmosphere of warm and egalitarianism, and avoidance of MI-inconsistent behaviors. In addition, strategies designed to selectively elicit and reinforce change talk were proscribed. The second MI condition (labeled MI) consisted of delivery of both relational and directive elements. In addition, we constructed a third, non-therapy condition (NTC, labeled selfchange in our prior study) to enable an experimental test as to whether relational components were an active ingredient in reducing drinking. Accordingly, NTC was designed to be a credible change option for those seeking help to reduce their drinking and contained elements thought to be active ingredients in the brief interventions (Bien, Miller, & Tonigan, 1993) but without any therapist contact.

We randomly assigned problem drinkers (N=89) seeking to reduce their drinking to the three conditions. Participants were treated and followed over an eight week period. Results indicated a significant reduction in drinking during treatment, but no significant differences across conditions (Morgenstem et al, 2012). Study results were surprising, especially the equivalent drinking outcome for NTC relative to two four-session therapy conditions delivered by experienced therapists. However, there were study limitations. The sample size per condition was small (n < 30). In addition, there was an imbalance in baseline drinking such that participants in MI had more severe drinking problems than those in NTC.

The Current Study

The aim of the current study was to re-test hypothesized within treatment drinking outcome differences across MI, SOMI, and NTC using a larger sample, where the distribution of drinking severity at baseline was more balanced across conditions than in the prior study. In addition, we hypothesized that the effect of MI relative to the other conditions would be moderated by motivation at baseline. Specifically, those with lower motivation would have differentially reduced drinking in MI relative to the other conditions. If MI’s primary mechanism of action is increasing motivation, it makes sense that MI would be most effective among those with lower motivation to change. Motivation was measured two ways using the Readiness to Change Questionnaire (Heather & Rollnick, 2000) and a single item, daily measure of commitment averaged over seven days. Support for this moderation hypothesis would add evidence for MI’s theory of change. The current study aims are limited to investigating main and patient-matching hypotheses. Mediation hypotheses will be examined in a future report.

Method

Study Overview

This study was reviewed by and received approval from the Institutional Review Board, Office of the Human Research Protection Program and the Institutional Review Board, Program for Human Subjects Research. We recruited 139 problem drinkers with an AUD diagnosis seeking help to reduce drinking. In order to represent the three theoretically distinct elements of MI, three conditions were created: MI, MI without directional or technical elements (SOMI), and a non-therapy control condition (NTC). All participants received feedback (see description below) from a research assistant (RA) following assessment and were then randomly assigned to condition. Participants completed assessments five and eight weeks following baseline. In addition to standard assessments and the interventions, participants responded to a twice-daily, online survey using smartphones. Because participants had a diagnosed AUD and were seeking treatment, NTC participants were offered MI after an eight-week treatment period, if still drinking at problematic levels.

Participants

Recruitment.

General advertising online and in local media were used to recruit participants seeking treatment to reduce but not stop drinking. Advertisements emphasized client choice and a moderation approach. Participants were screened on the phone and then, if eligible, were scheduled for an in-person assessment.

Study eligibility.

Participants were considered eligible if they were: (1) between the ages of 18 and 75; (2) had an estimated average weekly consumption of greater than 15 or 24 standard drinks per week for women and men, respectively, during the prior 8 weeks and (3) had a current AUD. Participants were excluded if they: (1) had another substance use disorder (for any substance other than alcohol, marijuana, nicotine) or were regular (defined as greater than weekly use) drug users; (2) presented with a serious psychiatric disorder or suicide or violence risk; (3) demonstrated clinically severe alcoholism, as evidenced by physical withdrawal symptoms or a history of serious withdrawal symptoms; (4) were legally mandated to substance abuse treatment; (5) reported social instability (e.g., homeless); (6) expressed a desire at baseline to achieve abstinence; or (7) expressed a desire or intent to obtain additional substance abuse treatment during the 8 week treatment period.

Procedures

Participants’ flow through the study is captured in Figure 1. During their initial in-person assessment, participants provided informed consent and participated in a brief evaluation with a RA. In order to avoid reactivity (Clifford, Maisto, & Davis, 2007) to the commonly used Timeline Followback Interview (TLFB, L. C. Sobell, Sobell, Leo, & Cancilla, 1988; M. B. Sobell et al., 1980), a non-reactive, standard alcohol screen and a standard diagnostic measure were used to determine initial eligibility (described further below). A mental health clinician also assessed for any high risk mental health disorders, such as current major depression. At the end of this evaluation (week 0), participants were trained on the ecological momentary assessment (EMA) system (described below) and asked to return one week later to attend the full baseline assessment (week 1). Participants completed a full week of EMA prior to assessment with the TLFB and assignment to condition, in order to assess for potential reactivity to the EMA. There were no significant changes in drinking during the pre-treatment week of EMA.

Figure 1.

Study flow and attrition.

At week 1, participants completed a full assessment battery, which included the TLFB covering the prior nine weeks. All participants were provided with normative feedback, described further below, about their drinking from study staff prior to randomization. Participants were then randomly assigned to one of three conditions: MI, SOMI, or NTC only. Participants assigned to either MI or SOMI received four sessions of psychotherapy at weeks 1, 2, 5, and 8. Those randomized to the NTC condition were encouraged to change on their own. If still drinking at problematic levels at the end of the 8 week period, NTC participants were offered four sessions of MI. Follow up rates for assessments at weeks 5, and 8 were 94.2%, and 90.6%, respectively.

Ecological Momentary Assessment Surveys

Participants were asked to complete twice-daily, online surveys via smartphone (e.g., EMA) during the study period. Starting the morning after the screening assessment, participants received two prompts per day via text message, one in the morning and one in the evening, asking that they complete a survey using the web browser on their mobile phone. Participants received these prompts for the first two weeks of the study (i.e. one week prior to and one week following baseline assessment/randomization), as well as for week 4 and week 7 for a total of 28 days of surveys during the study period. Participants were given a choice regarding the timing of the morning and evening prompts in order to align with their schedules. Morning prompts could be sent between 6 a.m. and 12 p.m. and evening prompts could be sent between 4 p.m. and 9 p.m. Efforts were made to ensure that evening prompts were sent more than 9 hours after morning prompts (i.e., if a participant chose 12 p.m. for the morning prompt, the first available option for the evening prompt was 9 p.m.). Each daily survey took between 2 to 6 minutes to complete. Constructs assessed in the morning and evening surveys were slightly different, with both assessing affect, stress, and commitment. The morning survey assessed for alcohol use whereas the evening survey did not. Only the evening survey assessed for context in which participants were potentially drinking. At the screening appointment, participants watched two training videos on the EMA surveys, and RAs provided ongoing support and clarification for any questions that participants had about the surveys or the process.

Overall compliance rates for the morning and evening surveys were 78.4% and 66.3%, respectively. No significant differences were found in EMA compliance between treatment groups on either morning or the evening surveys. Only the morning survey data was used for this analysis for the following reasons: 1) previous day’s drinking was assessed only during the morning survey; 2) the morning survey had fewer missing days (maximized power), and 3) while commitment was measured both in the morning and evening, the two time points were highly correlated (r = .60, p <001).

Study Interventions

All participants received feedback from an RA during their intake appointment immediately prior to randomization. Normative feedback consisted of an estimated average weekly consumption of alcohol based on screening reports and their score from the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT, Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) with a description of AUDIT risk categories, classifying individuals into four levels: low risk, in excess of low risk, harmful/hazardous risk, or may be physically dependent. Participants in MI and SOMI received equivalent amount of treatment, delivered in 4 sessions that lasted between 45 minutes to an hour long at weeks 1, 2, 5, and 8. Participants in the NTC condition received no treatment, as described below.

Motivational Interviewing (MI).

We adapted the MI condition from MET used in Project MATCH (Miller, Zweben, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992; Project MATCH Research Group, 1993). We revised the structured personalized feedback module to include: percentile rank for quantity and frequency of drinking compared to a normative comparison of adults in the United States; information about risk factors for developing alcohol dependence, including an estimated tolerance for alcohol based on peak blood alcohol concentration, other drug risk, family risk, and the score on the Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS, Skinner & Horn, 1984). Other revisions to the MATCH MET intervention were: 1) there was no “significant other” involvement in any of the sessions, and 2) all in-session discussions regarding goals were geared towards moderation rather than abstinence. A similar moderation-focused adaptation of MET was used previously and demonstrated efficacy among problem drinkers seeking moderation (Morgenstern et al., 2007; Morgenstern et al., 2012). Consistent with the approach described in the MET manual, structured feedback, importance and confidence rulers, formulating a change plan, and other directional activities and skills (e.g., amplified and double-sided reflections) were delivered in a flexible manner with the goal of eliciting change talk and strengthening commitment to change (Miller & Rollnick, 2013, pp. 175, 269; Miller et al., 1992, pp. 13–32).

Spirit Only MI (SOMI).

SOMI consisted primarily of the client-centered elements of MI including therapist stance (warmth, genuineness, egalitarianism), emphasis on client responsibility for change, collaboration, extensive use of reflective listening skills (e.g., open-ended questions, simple reflections), and avoidance of MI-inconsistent behaviors (advise, confront, take expert role, interpretation). Specific and selective evocation and reinforcement of change talk was proscribed. For example, using amplified and double-sided reflections to evoke change talk or directing clients back to focus on the target behavior, reducing drinking, were avoided. Rather than targeting change talk, reflective listening was focused on affective content consistent with client-centered experiential treatments (Bohart, 1995). Other techniques designed to heighten discrepancy and evoke change talk (e.g., ruler exercises, structured feedback) or to direct the therapy process towards positive change (e.g., change plan, asking for a commitment) were also proscribed.

To clarify, we note that the term MI Spirit has been used elsewhere to include therapist elicitation and reinforcement of change talk (Moyers, Martin, Manual, Miller, & Ernst, 2010) in addition to MI client-centered elements. We note our use of the term Spirit Only MI is intended only as a useful descriptive label of the SOMI therapy condition employed in this study. The SOMI protocol was written and refined in a previous pilot study (Morgenstem et al., 2012).

Non-therapy Condition (NTC).

The NTC condition was a non-therapy condition designed to incorporate elements hypothesized in the brief intervention literature to contribute to change, but not associated with relational or technical active ingredients (Bien & Miller, 1993). These elements included normative feedback, personal responsibility, and efforts to foster self-efficacy. After receiving normative feedback, participants were asked to attempt to change on their own during the next eight weeks; told that research had shown that some individuals could reduce their drinking without professional help; and informed that completion of the EMA as well as research interviews might prove helpful in that effort. Participants were told they would be offered treatment at the end of the eight week period if still drinking at problematic levels.

Therapists and training.

Five master’s and doctoral level therapists provided both MI and SOMI. All therapists with the exception of one had five or more years of experience providing MI, were highly experienced substance use disorder clinicians, and had participated in the pilot study. For the current study, all therapists participated in a three-hour training on the protocol, followed by once weekly group and individual supervision. Supervision consisted of ongoing review of session videotapes and focused on ensuring fidelity to each protocol. All therapists were assigned practice cases for re-training purposes. Performance was reviewed via taped sessions, and therapists were required to meet threshold fidelity criteria, as described below, prior to treating study participants.

Condition fidelity and discriminability.

We assessed fidelity using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code, Version 3.1.1 (MITI, Moyers et al., 2010). Discriminability was assessed using MITI coding, behavioral counts of specific techniques used within session, and DARN-C coding (Amrhein, Miller, Yahne, Palmer, & Fulcher, 2003) to determine whether condition differentiation was achieved as planned and whether that led differential rates of change talk utterances.

MITI coding.

Fifteen percent of the 355 sessions were coded by three raters trained in MITI coding. Raters were trained by one of the investigators [PA]. Raters coded the entire session. Eleven sessions were coded by two different raters. Intraclass coefficients (ICC; Model 3,1; Shrout & Fleiss, 1979) for absolute agreement were calculated for individual items of the MITI (global ratings, behavioral counts). ICCs for the items ranged from .615 to .875. Using standards reported by Cicchetti (1994), values greater than .6 are good, and values greater than .75 are excellent.

The MI and SOMI conditions were conceptualized to share the critical spirit or client-centered elements of MI. Therefore, in order to evaluate treatment fidelity, MITI global ratings of Empathy, Collaboration, and Autonomy/Support were assessed. Sessions with ratings of high competency on these scales would constitute fidelity for relational elements in both therapy conditions. We would not expect condition differences on these elements.

Two MITI global scales were selected for condition discriminability: (1) MITI global rating of Evocation (therapist “proactively to evoke client’s own reasons for change”, “uses structured therapeutic tasks as a way of reinforcing and eliciting change talk”) (Moyers et al., 2010, pp. 5-6); and (2) MITI global rating score of Direction (“clinician exerts influence on the session…towards the target behavior or referral question”, Moyers et al., 2010, p. 11). It was hypothesized that MI would demonstrate higher scores of Evocation and Direction.

Structured activities.

A behavioral count of therapist techniques, called structured activities, was also used to differentiate conditions. This was a summed score of the occurrence of importance and confidence rulers, double-sided reflections, amplified reflections, visualization of behavior change, values clarification, personalized feedback, and formulating a change plan. While these techniques are not considered unique to MI, they have been used in MET and discussed by Miller and Rollnick (2009) as being “used fruitfully within MI” (p.132) to evoke change talk and motivate change. It was hypothesized that MI would demonstrate higher rates of structured activities than MI.

DARN-C coding.

DARN-C codes (Amrhein et al., 2003) were only used for the current analysis to determine if conditions were discriminable on change talk, as hypothesized, thereby corroborating any differential results on the MITI’s global Evocation scores across conditions. A total of 98 sessions were coded using DARN-C, with sessions 1 and 2 for 25 participants in MI and 24 participants in SOMI. For the first two sessions per participant, recorded utterances of commitment and DARN (desire, ability, readiness, reasons, and need, in aggregate) language were coded for frequency and strength (codes “−1” to “−5” for increasing “Sustain Talk” strength; “0” codes for “Neutral Talk”; and codes “+1” to “+5” for increasing “Change Talk” strength). For each session, commitment and DARN code frequencies were then summed and strengths averaged; frequency totals and strength means were then averaged over the first and second sessions for analysis. It was expected that MI sessions would have more frequent Change Talk and greater commitment and DARN language strength than SOMI sessions. Coders for the current study were the same as for the pilot study, and the resulting ICC was .84 (Morgenstem et al., 2012). Previous implementations of the DARN-C coding scheme (Aharonovich, Amrhein, Bisaga, Nunes, & Hasin, 2008; Aharonovich, Stohl, Ellis, Amrhein, & Hasin, 2014; Amrhein et al., 2003; Carpenter et al., 2016; Morgenstem et al., 2012; Walker, Stephens, Rowland, & Roffman, 2011) have yielded strong inter-rater reliability values, with average ICC = .73 (SD = 0.12), as well as demonstrated reliable predictive validity.

Compliance with therapy.

Compliance with therapy was high across both treatment groups, with 89.4% of MI clients and 89.1% of SOMI clients completing all four sessions.

Measures

Sociodemographics.

A self-report, demographic questionnaire used in a series of completed studies was used during the initial phone and in-person encounter with the participant. This included data on age, gender, educational and occupational information, race and ethnicity, medical history, family psychiatric and substance abuse history, and the participant’s substance use treatment history.

Screening and substance use diagnosis.

Two instruments were used to screen participants for eligibility and later identify alcohol and other substance use disorders. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-C was used to determine preliminary eligibility for the study, as it is a shortened version of the AUDIT and has demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Bush, Kivlahan, & McDonell, 1998). The Composite International Diagnostic Instrument, Substance Abuse Module (CIDI-SAM, Cottier, Robins, & Helzer, 1989) was used to evaluate substance dependence exclusion criteria and the number of AUD criteria a participant satisfied. The CIDI-SAM is a well-established diagnostic interview that has demonstrated excellent reliability and validity (Wittchen et al., 1991).

Psychiatric and cognitive impairment exclusion criteria.

Two screening tools, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Psychotic Screening and Mood Disorders sections (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001), and the Mini-Mental Status Examination (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) were used to screen for serious psychiatric symptoms and cognitive impairments, respectively. Both of these instruments are well established as having strong psychometric properties (Folstein, Folstein, McHugh, & Fanjiang, 2001; Tombaugh & McIntyre, 1992; Ventura, Liberman, Green, Shaner, & Mintz, 1998).

Alcohol and drug use problems.

The ADS (Skinner & Horn, 1984) is a 25-item self-report measure used to assess severity of alcohol dependence. Items are summed, providing a raw score for interpretation. The ADS has demonstrated high reliability and validity across substance using populations (Kahler, Strong, Hayaki, Ramsey, & Brown, 2003). Cronbach’s alpha was .78. The Short Inventory of Problems (SIP, Miller, Tonigan, & Longabaugh, 1995) is a 15-item self-report measure of lifetime or past three months’ negative consequences of drinking. The SIP has demonstrated strong psychometric properties (Kenna et al., 2005). Cronbach’s alpha for this study was .88.

Motivation to reduce drinking.

We assessed baseline motivation to reduce drinking using two constructs: readiness to change and strength of commitment not to drink heavily. At the baseline assessment, each participant completed The Readiness to Change Questionnaire, treatment version (RCQ, Heather & Rollnick, 2000). The RCQ is a 12-item self-report instrument for measuring “stage of change” of the participant in changing drinking. The RCQ has demonstrated good psychometric properties including predictive validity, and it consists of three subscales: Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Action. A composite readiness score was created by reverse coding the scores for the precontemplation items and then calculating the mean of all the items. Cronbach’s alpha was .73.

We also assessed strength of commitment using one EMA item that asked, “How committed are you to not drink heavily (that is, drink 4 or more drinks for women, 5 or more drinks for men) in the next 24 hours?” The response set ranged from 0 “not at all” to 8 “extremely.” A mean for this item during the baseline week was calculated to create a score of baseline EMA-reported motivation to change. In a prior study, strength of commitment during the week prior to treatment significantly predicted within treatment drinking (Kuerbis, Armeli, Muench, & Morgenstern, 2013). Using this same item, commitment was predictive of drinking across the treatment period in a previous analysis of this study (Morgenstern et al., 2016). The RCQ and the commitment item were significantly correlated (r = .40, p < .001). Neither measure of motivation was included in the normative or personalized feedback to the participants.

Drinking outcomes.

Two methods were used to assess drinking prior to and during the treatment period. The TLFB (M. B. Sobell et al., 1980) assessed frequency and intensity of alcohol use during the nine weeks prior to the week 1 assessment. It was re-administered at weeks 5 and 8 covering the time since the last assessment. The TLFB has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2004), agreement with collateral reports of alcohol (Dillon, Turner, Robbins, & Szapocznik, 2005), convergent validity, and reliability (Vinson, Reidinger, & Wilcosky, 2003). TLFB data for the entire pre-baseline period was aggregated into summary variables that corresponded to the outcome variables. Baseline values for mean sum of standard drinks per week and heavy drinking days per week were calculated and used as covariates. Outcome data was aggregated into the sum of standard drinks (SSD) per week for each of the weeks during the treatment period. Additionally, heavy drinking days (HDD) per week was calculated as days per week in which participants drank greater than three drinks or greater than four drinks for women and men, respectively, for each week during the treatment period.

Drinking was also assessed via EMA in the daily morning survey by asking, “Did you drink yesterday since your morning survey?” When participants responded “yes” to this question, they were asked to report the number of standard drinks of beer, wine, and liquor respectively that they had consumed in the last 24 hours. Participants were reminded in the survey question about standard drink sizes for each category. Participants who responded “no” to the question of whether they drank yesterday were coded as drinking 0 drinks in the prior day. Daily reports of drinking were aggregated into weekly SSD for baseline and each EMA week assessed (denoted by EMA SSD). If a participant completed fewer than 4 days of the survey in a week, then that week was counted as missing. In weeks with 3 or fewer days missing, values for SSD were imputed by taking the average of the days present, then multiplying by 7. There were a total of 3 time points during treatment for EMA SSD, with the pre-treatment week used as a baseline covariate.

Analytic Plan

All analyses were conducted using SAS statistical software program (SAS Institute Inc., 2002-2012). Condition equivalence on demographics, drinking, and other problem severity at baseline were determined using chi square tests, t-tests, and one-way ANOVAs, where appropriate. In addition, to determine fidelity and discriminability of therapy conditions, we tested for mean differences on MITI scores and DARN-C coding. Next, intent-to-treat analyses were conducted on two primary repeated measures outcomes, SSD and HDD, created from the TLFB data and spanning the eight week treatment period. Eight of the 139 participants did not provide follow-up data, yielding an analytic sample of n = 131. No significant differences were found in attrition across conditions; attrition rates for the conditions were 4.2% for MI, 4.3% for SOMI, and 6.5% for NTC.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE, Liang & Zeger, 1986) were used to analyze the non-normal, longitudinal data for each of the primary dependent variables. GEE is a data analytic technique appropriate for a longitudinal panel design because it is a powerful test that corrects for correlated observations (Stokes, Davis, & Koch, 2000). For this analysis, a negative binomial distribution with log link function was specified, which provided good model fit for each of the dependent variables, with an exchangeable working correlation.

The two models were built independently and in steps. First, demographic variables were entered into the models testing both outcome variables to determine their impact on drinking and the need to control for those effects in the final model. No demographic variables yielded an effect atp < .05, and were thus removed from the models. Both time and pretreatment weekly SSD or HDD were added to the respective models as covariates. Condition was coded using Helmert contrast coding, such that Contrast 1 was the average of both therapy conditions MI and SOMI vs. NTC (MI=−1, SOMI=−1, NTC=2) and Contrast 2 was MI vs. SOMI (MI=−1, SOMI=1, NTC=0). Both contrast variables were entered into the models together. All variables in each of the models were centered. To isolate effects over time, time by condition interaction terms were initially added to each of the models; however, none yielded significant effects and were therefore removed from the final models.

Next, we tested whether SSD or HDD was moderated by baseline readiness to change or commitment not to drink heavily. For each of the outcome variables, the readiness and commitment variables and their interaction terms (e.g., motivation × condition) were entered into each of the models independently.

Finally, in order to determine whether method of assessment yielded distinct results, the analyses described above were repeated using drinking outcomes reported via EMA (EMA SSD), which contained three time points during the eight week treatment period. Using the same model building process as described above, condition and covariates were entered into the model in identical fashion as above to identify potential main effects of condition on EMA derived drinking outcomes. GEE was again used for this analysis, for which a negative binomial distribution with log link function was specified and an exchangeable working correlation. Next, the moderating impact of readiness and commitment were also explored with this outcome variable, through the same process of independently testing interaction terms.

Results

Sample Description

On average, participants were middle-aged, well-educated (70% college graduates), employed (78%), Caucasian (76%), and female (57%) (see Table 1). Participants drank heavily at baseline, consuming on average about 31 standard drinks per week. Almost all participants (91%) met criteria for current DSM-IV alcohol dependence. Initial descriptive statistics of demographics yielded no significant differences between treatment groups. Similarly, the selected markers for drinking severity were equivalent across conditions on all the variables.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Sample

| Variable | MI (N = 47) |

SOMI (N = 46) |

NTC (N = 46) |

Overall Sample (N = 139) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 43.7 | 11.09 | 43.39 | 13.53 | 43.0 | 13.34 | 43.4 | 12.6 |

| Male | 44.7 | 41.3 | 43.5 | 43.2 | ||||

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic, White/Caucasian | 66.0 | 71.7 | 69.6 | 69.0 | ||||

| Hispanic/Latino, any race | 23.4 | 13.0 | 15.2 | 17.3 | ||||

| Other | 10.6 | 15.3 | 15.2 | 13.7 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||

| High school diploma/GED and under | 10.6 | 8.7 | 2.2 | 7.2 | ||||

| Some college/Associates | 23.4 | 19.6 | 26.1 | 23.0 | ||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 36.2 | 47.8 | 26.1 | 36.7 | ||||

| Some graduate school or higher | 29.8 | 23.9 | 45.7 | 33.1 | ||||

| Employment | ||||||||

| Employed | 91.5 | 63.0 | 78.3 | 77.7 | ||||

| Unemployed/Looking for work | 2.1 | 15.2 | 10.9 | 9.4 | ||||

| Not in labor force/not looking for work | 6.4 | 21.7 | 10.9 | 13.0 | ||||

| Drinking Severity | ||||||||

| Mean sum of standard drinks per week | 30.6 | 11.5 | 31.3 | 15.0 | 31.3 | 16.1 | 31.1 | 14.2 |

| Mean drinks per drinking day | 6.3 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 2.3 | 6.2 | 2.6 | 6.1 | 2.6 |

| Short Inventory of Problems (SIP) | 13.5 | 8.7 | 12.4 | 8.0 | 13.5 | 5.9 | 13.1 | 7.6 |

| Alcohol Dependence Scale (ADS) | 13.6 | 5.3 | 13.5 | 6.6 | 14.7 | 5.5 | 13.9 | 5.8 |

| Number of alcohol dependence criteria met | 5.0 | 1.6 | 4.7 | 1.7 | 5.5 | 1.6 | 5.1 | 1.7 |

| Any drug use | 40.4 | 26.1 | 28.3 | 31.7 | ||||

| Beck’s Depression Inventory-II Score (BDI-II) | 13.9 | 9.0 | 14.7 | 9.9 | 12.4 | 8.3 | 13.7 | 9.1 |

| Ever received formal treatment for substance use problem | 23.4 | 39.1 | 37.0 | 33.1 | ||||

| Readiness to Change Questionnaire Item Mean* | 1.1 | .36 | .92 | .41 | 1.1 | .36 | 1.1 | .38 |

| Average Daily Commitment | 5.6 | 1.6 | 4.9 | 1.7 | 5.2 | 1.8 | 5.2 | 1.8 |

p < .05

Condition Fidelity and Discriminability

Table 2 reports the results of the MITI coding, directional activity count, and DARN-C coding results across conditions. For global MITI scales Empathy, Autonomy/Support and Collaboration, both conditions demonstrated mean scores above 4, indicating proficiency according to expert-defined standards. Only Empathy was significantly different, with SOMI demonstrating a higher mean Empathy score than MI. For the two global scales Evocation and Direction, as expected, MI demonstrated a significantly higher mean compared to SOMI. In addition, MI demonstrated a significantly higher mean score per session on structured activities. Finally, DARN-C coding revealed significantly higher rates of commitment frequency and strength, as well as DARN frequency and strength for those in MI compared to SOMI.

Table 2.

Condition differences related to fidelity and discriminability

| MI M (SD) |

SOMI M (SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MITI 3.1.1.a | (N = 30) | (N = 24) | |

| MI Adherent Behaviorsb | 7.6 (3.9) | 6.6 (4.4) | NS |

| Global Scales | |||

| Autonomy/Support | 4.4 (.6) | 4.4 (.6) | NS |

| Empathy | 4.5 (.5) | 4.9 (.3) | < .01 |

| Collaboration | 4.3 (.8) | 4.5 (.6) | NS |

| Direction | 4.6 (.7) | 2.6 (1.4) | <.001 |

| Evocation | 4.2 (.7) | 3.1 (1.2) | <.001 |

| % of sessions with score over 4 in all 5 global scales | 83.9 | 36.8 | -- |

| % of sessions with score of 4 in 3 global scales (Autonomy/support, empathy and collaboration) | 87.1 | 94.7 | -- |

| Structured Activitiesc | 3.9 (2.9) | 0.43 (0.8) | <.001 |

| DARN-C Codingd | (N = 25) | (N = 24) | |

| Commitment Talk Frequency Change Neutral Sustain |

20.2 (7.05) 5.98 (2.43) 14.2 (5.88) |

12.3 (5.09) 4.52 (2.78) 13.3 (6.77) |

<.001 NS NS |

| Commitment Talk Strengthe | 0.39 (0.40) | −0.08 (0.47) | <.001 |

| DARN Talk Frequency Change Neutral Sustain |

79.7 (24.6) 28.1 (11.4) 37.7 (15.4) |

50.0 (21.5) 24.4 (10.7) 34.7 (16.0) |

<.001 NS NS |

| DARN Talk Strengthe | 1.01 (0.34) | 0.57 (0.59) | <.005 |

MITI = Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity

MI Adherent Behaviors included those defined by MITI 3.1.1, e.g.., asking permission before giving advice, emphasizing client control, supporting the client with compassionate statements, affirmations

Structured Activities=importance and confidence rulers, change plan, structured feedback, amplified or double-sided reflections, visualization of behavior change

DARN = Desire, ability, reason, need. Note: Because 87/98 (89%) of the sessions did not present readiness utterances, readiness codes from the other 11 patients were excluded from this computation. Scores were averaged over sessions 1 and 2.

Positive M indicates patient bias to change (reduce or abstain from) drinking; negative M indicates patient bias to sustain drinking.

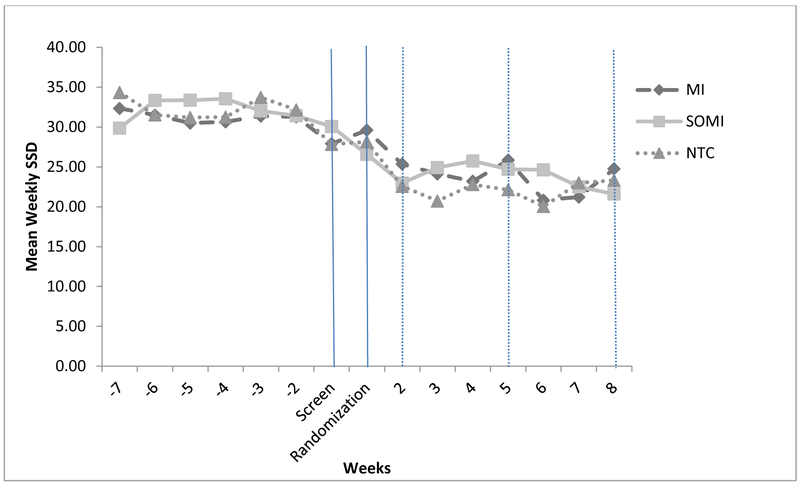

Main Condition Effects on Drinking at End Treatment

When controlling for baseline drinking, there were no significantly different effects of the average of MI and SOMI compared to NTC on either TLFB drinking outcome (MI + SOMI vs NTC: SSD: B = .11, SE = .10, p = .22; HDD: B = −.04, SE = 0.18, p = .73). In addition, there were no significantly different effects on drinking between MI and SOMI (MI vs SOMI: SSD: B = −.00, SE = .09, p = .97; HDD: B = .13, SE = 0.12, p = .27). Figure 2 demonstrates the TLFB SSD trajectories for each of the three conditions over time.

Figure 2.

Drinking trajectories by condition. Initial session happened at randomization. Dotted lines indicate treatment sessions at weeks 2, 5, and 8. Assessments occurred at Screen, Randomization, 5, and 8.

Treatment Condition by Motivation to Reduce Drinking

SSD.

The main effect of the RCQ on SSD, when controlling for condition, was not significant (B = .05, SE = .10, p = .65). When the interaction terms with condition were entered into the model, neither yielded a significant effect (MI + SOMI vs NTC × RCQ: B = .17, SE = .26, p = .51; MI vs SOMI × RCQ: B = −.05, SE = .21; p = .80). The main effect of commitment was significant (B = −.04, SE = .02; p = .02), when controlling for condition, such that for every unit increase in commitment there was a 4% decrease in drinking. The commitment × condition interaction terms were not significant; MI + SOMI vs NTC × Commitment: B = .05, SE = .05, p = .25; MI vs SOMI × Commitment: B = −.08, SE = .04; p = .06.

HDD.

There was no significant main effect of RCQ (B = .09, SE = .13; p = .46) on HDD, and a significant main effect for commitment (B = −.05, SE = .02; p = .03) on HDD. None of the interaction terms testing the RCQ and commitment as moderators yielded significant effects in predicting HDD. All p-values were greater than .10. The parameter estimates for MI vs SOMI × commitment variable were in a similar direction to that for SDD, but were not significant (B = − .06, SE = .06; p = .32).

Results Related to EMA-Based Drinking at End Treatment

Results of the tests with EMA SSD as the outcome variable were generally consistent with the TLFB based results. There were no significant effects of condition on drinking. While there was an independent main effect of RCQ on drinking (B =.20, SE = .03; p = .02), RCQ was not a significant moderator of condition on drinking. Finally, there was no independent main effect of commitment (though it was in the same direction as the effect above) nor was there a moderating effect of commitment on condition. All p-values were greater than .10.

Discussion

This study used a dismantling design to examine MIs hypothesized active ingredients. Specifically, the contrast between MI and SOMI was designed to test whether directional strategies that selectively identify and reinforce change talk lead to improved outcomes relative to a client centered therapy that did not include directional strategies. In addition, the contrast between SOMI and NTC was designed to test whether client-centered therapy strategies alone improved outcomes relative to a non-therapy condition in which participants were offered normative feedback and encouragement to change on their own. Neither hypothesis was supported. Examination of drink trajectories in Figure 2 indicates a rapid decline in drinking after randomization across all conditions. Participants receiving normative feedback and encouragement to change on their own had equivalent drinking outcomes to those receiving MI or an MI informed version of non-directive counseling.

The predicted interaction that MI would be superior to SOMI and NTC for those with low commitment was not supported. Lack of findings may represent a mismatch between client need and what the therapy is offering. MI was designed to help individuals who are ambivalent or not fully committed to change to engage in a collaborative decision-making process and become more motivated. Problem drinkers voluntarily seeking treatment and expressing a strong commitment not to drink heavily may have already engaged in this decision making process, thus preventing MI from emerging as a stronger intervention.

Study findings of no significant difference in drinking outcomes across conditions replicate those in our earlier study (Morgenstern et al., 2012). The current study has a number of strengths including an adequate sample size, good balance of participant characteristics across conditions, condition fidelity and discriminability, high levels of therapy attendance, low follow-up attrition, and use of EMA and traditional TLFB methods for assessing drinking outcomes. Examination of results across studies suggests that participants were quite similar in demographics and problem severity at baseline and that conditions yielded similar levels of drinking across the outcome period. However, in contrast to our pilot study, we did not find evidence that MI produced a more rapid reduction in drinking than the other conditions.

Findings in Context

Results of the current study differ from those of Sellman and colleagues (2001) who found MI yielded significantly improved drinking outcome relative to a non-directive listening condition or a no further treatment control. One explanation for the different results is that Sellman et al. recruited patients entering an alcohol clinic, rather than recruiting problem drinkers via advertisements. It may be that patients entering treatment differ in important ways from those recruited using other means and that these patients benefit differentially from MI. Alternatively, Sellman and colleagues detected condition differences in only one relatively nonstandard outcome measure, unequivocal heavy drinking defined as drinking more than 10 standard drinks on at least 6 occasions. Standard drinking outcomes, such as continuous measures of alcohol consumption, were not reported making it difficult to compare findings across the studies.

Four previous AUD treatment studies have examined whether MI is differentially more effective for participants with low motivation. Heather and colleagues (Heather, Rollnick, Bell, & Richmond, 1996) found MI was more effective in reducing drinking compared to a skills treatment condition among problem drinkers with low motivation recruited in an inpatient medical setting. However, Maisto and colleagues (Maisto et al., 2001) failed to find a motivation-by-MI effect in a study that compared MI to brief advice among problem drinkers in primary care. Witkiewitz and colleagues (Witkiewitz, Hartzler, & Donovan, 2010) found that outpatients with low motivation fared better in MET relative to CBT. However, the United Kingdom Alcohol Treatment Trial (UKATT) failed to find that MET improved outcomes relative to Social and Behavioral Network Therapy among outpatients with low motivation (UK Alcohol Research Treatment Trial Research Team, 2008). Our findings did not help clarify the relationship between these constructs.

Implications and Future Research Directions

Dismantling studies offer a relatively strong method to test AUD treatment-related MOBC. The current findings are largely consistent with prior reviews of empirical studies in failing to find consistent support for MI’s hypothesized MOBC (Longabaugh et al., 2013; Magill et al., 2014). It may be that MI works as hypothesized but only for a limited subset of those with AUD and only under certain conditions. For example, Gaume and colleagues (Gaume, Longabaugh, et al., 2016) found the expected positive association between MI consistent therapist behaviors, increased CT, and reduced drinking, but only when therapists were experienced and among participants with more severe drinking problems. Future studies are needed to further examine these relationships. Future research should also examine whether providing MI to individuals already committed to change might be detrimental relative to receiving other bona fide treatments. Identifying mismatches between treatments and client attributes has not received much attention, but may be underappreciated as an approach to developing personalized AUD treatment. For example, Karno and Longabaugh (2007) examined a set of matching and mismatching hypotheses in Project MATCH. They found that while matching effects tended to optimize otherwise good outcomes, mismatches had larger effect sizes and predicted relatively poor outcomes.

It is noteworthy that NTC yielded equivalent reductions in drinking to MI. NTC was designed as a relatively weak control in an effort to test whether SOMI, a relational only condition, would prove effective in reducing drinking. Thus, the results are surprising. NTC included a number of ingredients that are core to brief alcohol interventions, including fostering a sense of personal responsibility for behavior change, normative feedback, and enhancing self-efficacy (Bien et al., 1993). These elements are also part of MI, but have not been featured prominently in theories about how MI works. In addition, participants received EMA and in-person follow-up assessments. Miller and Sanchez (1994) speculated that follow-up assessments contribute to the efficacy of BI. EMA alone has not been found to be reactive in reducing drinking (Shiffman, 2009), but it may have stronger effects on drinking when delivered as part of a self-change intervention. Overall, it may be that elements of MI that have their origins in brief interventions, in combination with aspects of clinical trials research methods, have stronger effects on drink reduction than anticipated. While research on MI’s MOBC has focused largely on therapist behaviors (Miller & Rose, 2009; Magill et al., 2014), the current findings suggest further exploration of whether and how non-therapy components of MI work deserve more attention.

Study Limitations

Study findings are limited to an examination of initiation of drink reduction in mild-to-moderately dependent drinkers recruited via advertisement and voluntarily seeking treatment. Coding schemes, such as the MITI, used in this study to test the differentiation of MI and SOMI were limited by their global nature. Within session tracking of therapist speech to specific client response was not performed in this study, and instead values of therapist behaviors were averaged across session. It is possible therefore that nuances of the relationship between therapist and client behavior may have been lost. Due to space constraints, findings are limited to condition main effects and one theory-relevant moderator effect on drinking outcomes at week 8. Given that the final therapy session occurred at week 8, it may be that the full effects of the intervention were not detected in the current analysis. It may be the case that MI, SOMI or both would have proved more effective than NTC at later follow-up. Because we offered participants in NTC the option to receive MI at week 8, a comparison of the three conditions on later outcomes is not available. Future reports will explore post treatment drinking outcomes between MI and SOMI, as well as hypothesized causal chains that link active ingredients across the three conditions to hypothesized mechanisms, such as increases in motivation or self-efficacy, and their resulting impact on drink reduction. Finally, it is possible that use of the TLFB, EMA and feedback were either reactive or therapeutic interventions on their own and that their use resulted in reduced drinking across conditions and may have obscured differences in outcomes between MI and SOMI had these elements not been present.

Conclusion

This study dismantled MI into three discrete conditions in an effort to experimentally test whether directional and relational therapist strategies are responsible for reduced drinking in MI. Findings indicated that a condition representing the directional and relational aspects of MI, one containing only relational ingredients, and a control that contained neither directional nor relational ingredients yielded equivalent outcomes on initiation of drink reduction. In addition, participants with low levels of pre-treatment motivation did not fare better in MI relative to the other conditions. Overall, findings replicate those found in a smaller pilot study (Morgenstern et al., 2012) and highlight the continued difficulty in demonstrating strong empirical support for MI’s theory of change.

Acknowledgments

Findings from this study will be presented at the annual meeting for the Research Society on Alcoholism in 2017. This study was supported with funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (Grant R01 AA020077; PI: Morgenstern).

Contributor Information

Jon Morgenstern, Department of Psychiatry, Northwell Health.

Alexis Kuerbis, Silberman School of Social Work, Hunter College, City University of New York.

Jessica Houser, Department of Psychiatry, Northwell Health.

Svetlana Levak, Department of Psychiatry, Northwell Health.

Paul Amrhein, Psychology Department, Montclair State University.

Sijing Shao, Department of Psychiatry, Northwell Health.

James R. McKay, Department of Psychiatry, Penn-TRI Center on the Continuum of Care in the Addictions, University of Pennsylvania

References

- Aharonovich E, Amrhein PC, Bisaga A, Nunes EV, & Hasin DS (2008). Cognition, commitment language, and behavioral change among cocaine-dependent patients. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 557–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharonovich E, Stohl M, Ellis J, Amrhein P, & Hasin D (2014). Commitment strength, alcohol dependence and HealthCall participation: effects on drinking reduction in HIV patients. Drug Alcohol Depend, 135, 112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.n.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrhein PC, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, & Fulcher L (2003). Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 862–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apodaca TR, & Longabaugh R (2009). Mechanisms of change in motivational interviewing: A review and preliminary evaluation of the evidence. Addiction, 104(5), 705–715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor T, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, & Monteiro MG (2001). The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bien TH, Miller WR, & Tonigan JS (1993). Brief interventions for alcohol problems: A review. Addiction, 88(3), 315–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohart A (1995). The person-centered therapies In Gurman A & Messer S (Eds.), Essential psychotherapies. (pp. 85–127). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Bush K, Kivlahan DR, & McDonell MB (1998). The AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questions (AUDIT-C): An effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Archives of Internal Medicine, 3, 1789–1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, & Henson JM (2004). Temporal stability of the Timeline Followback Interview for alcohol and drug use with psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 65, 774–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter KM, Amrhein PC, Bold KW, Mishlen K, Levin FR, Raby WN, . . . Nunes EV (2016). Derived relations moderate the association between changes in the strength of commitment language and cocaine treatment response. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 24(2), 77–89. doi: 10.1037/pha0000063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV (1994). Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment, 6, 284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA, & Davis CM (2007). Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: Part I. Alcohol use and related consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 68(4), 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Robins LN, & Helzer JE (1989). The reliability of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Substance Abuse Module-(CIDI-SAM): A comprehensive substance abuse interview. British Journal of Addiction, 84, 801–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon FR, Turner CW, Robbins MS, & Szapocznik J (2005). Concordance among biological, interview, and self-report measures of drug use among African American and Hispanic adolescents referred for drug abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(4), 404–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (2001). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition With Psychotic Screen (SCID-I/P W/PSYSCREEN). Retrieved from New York: [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, & McHugh PR (1975). Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 72(3), 189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR, & Fanjiang G (2001). Mini-Mental State Examination user’s guide. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Bertholet N, & Daeppen JB (2016). Readiness to Change Predicts Drinking: Findings from 12-Month Follow-Up of Alcohol Use Disorder Outpatients. Alcohol Alcohol, doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agw047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Faouzi M, & Daeppen J (2009). Counselor skill influences outcomes of brief motivational interventions. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 37, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J, Longabaugh R, Magill M, Bertholet N, Gmel G, & Daeppen JB (2016). Under what conditions? Therapist and client characteristics moderate the role of change talk in brief motivational intervention. J Consult Clin Psychol, 84(3), 211–220. doi: 10.1037/a0039918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, & Rollnick S (2000). Readiness to change questionnaire: User’s manual. Retrieved from Newcastle, England: [Google Scholar]

- Heather N, Rollnick S, Bell A, & Richmond R (1996). Effects of brief counselling among male heavy drinkers identified on general hospital wards. Drug Alcohol Rev, 75(1), 29–38. doi: 10.1080/09595239600185641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Hayaki J, Ramsey SE, & Brown RA (2003). An item response analysis of the Alcohol Dependence Scale in treatment-seeking alcoholics. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 127–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karno MP, & Longabaugh R (2007). Does matching matter? Examining matches and mismatches between patient attributes and therapy techniques in alcoholism treatment. Addiction, 102, 587–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenna GA, Longabaugh R, Gogineni A, Woolard RF, Nirenberg TD, Becker B, . . . Karolczuk K (2005). Can the Short Index of Problems (SIP) be improved? Validity and reliability of the 3-Month SIP in an emergency department sample. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 66(3), 433–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuerbis A, Armeli S, Muench F, & Morgenstern J (2013). Motivation and self-efficacy in the context of moderated drinking: Global self-report and ecological momentary assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 27(4), 934–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K, & Zeger SL (1986). Longitudinal analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika, 73(1), 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Longabaugh R, Magill M, Morgenstern J, & Huebner R (2013). Mechanisms of behavior change in treatment for alcohol and other drug use disorders In McCrady BS & Epstein EE (Eds.), Addictions: A Comprehensive Guidebook (2nd ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Magill M, Gaume J, Apodaca TR, Walthers J, Mastroleo NR, Borsari B, & Longabaugh R (2014). The technical hypothesis of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of MI’s key causal model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 973–983. doi: 10.1037/a0036833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Conigliaro J, McNeil M, Kraemer K, Conigliaro RL, & Kelley ME (2001). Effects of two types of brief intervention and readiness to change on alcohol use in hazardous drinkers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62(5), 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally AM, Palfai TP, & Kahler CW (2005). Motivational intervenitons for heavy drinking college students: Examining the role of discrepancy-related psychological processes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(1), 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2009). Ten things that Motivational Interviewing is not. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37, 129–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2013). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rose GS (2009). Toward a theory of Motivational Interviewing. American Psychologist, 64(6), 527–537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Sanchez VC (1994). Motivating young adults to for treatment and lifestyle change In Howard G & Nathan PE (Eds.), Issues in alcohol use and misuse in young adults (pp. 55–81). Notre Dame, IN:: University of Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, & Longabaugh R (1995). The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Test manual Retrieved from Rockville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, & Rychtarik RG (1992). Motivational Enhancement Therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. Retrieved from Rockville, MD: [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Irwin TW, Wainberg ML, Parsons JT, Muench F, Bux DA, . . . Schulz-Heik J (2007). A randomized controlled trial of goal choice interventions for alcohol use disorders among men-who-have-sex-with-men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(1), 72–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Amrhein PC, Hail LA, Lynch KG, & McKay JR (2012). Motivational interviewing: A pilot test of active ingredients and mechanisms of change. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 26(4), 859–869. doi: 10.1037/a0029674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Houser J, Muench FJ, Shao S, & Treloar H (2016). Within-person associations between daily motivation and self-efficacy and drinking among problem drinkers in treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(6), 630–638. doi: 10.1037/adb0000204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, & Tonigan JS (2009). From insession behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(6), 1113–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manual JK, Miller WR, & Ernst D (2010). Revised global scales: Motivational Interviewing treatment integrity 3.1.1 (MITI 3.1.1) Albuquerque, NM: Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA). [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, & Miller WR (2005). Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 28, 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project MATCH Research Group. (1993). Project MATCH: Rationale and methods for a multisite clinical trial matching patients to alcoholism treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 17, 1130–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2002–2012). SAS software, Version 13.1 for Windows. Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Sellman JD, Sullivan PF, Dore GM, Adamson SJ, & MacEwan I (2001). A randomized controlled trial of motivational enhancement therapy (MET) for mild to moderate alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 62, 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S (2009). Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) in studies of substance use. Psychological Assessment, 21(4), 486–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, & Fleiss JL (1979). Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull, 86(2), 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA, & Horn JL (1984). Alcohol Dependence Scale: Users guide. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, & Cancilla A (1988). Reliability of a timeline method: Assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. British Journal of Addiction, 83(4), 393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MB, Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Cooper AM, Cooper T, & Saunders B (1980). Developing a prototype for evaluating alcohol treatment effectiveness In Sobell LC & Ward E (Eds.), Evaluating alcohol and drug abuse treatment effectiveness: Recent advances (pp. 129–150). New York: Pergamon. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes ME, Davis CS, & Koch GG (2000). Categorical data analysis using the SAS system (2nd ed.). Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tombaugh TN, & McIntyre NJ (1992). The Mini-Mental State Examination: A comprehensive review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 40(9), 922–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UK Alcohol Research Treatment Trial Research Team. (2008). UK Alcohol Treatment Trial: Client-treatment matching effects. Addiction, 103(2), 228–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02060.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vader AM, Walters ST, Prabhu GC, Houck JM, & Field CA (2010). The language of Motivational Interviewing and feedback: Counselor language, client language, and client drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(2), 190–197. doi: 10.1037/a0018749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura J, Liberman RP, Green MF, Shaner A, & Mintz J (1998). Training and quality assurance with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I/P). Psychiatric Research, 79, 163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinson DC, Reidinger C, & Wilcosky T (2003). Factors affecting the validity of a Timeline Followback Interview. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, 64, 733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker D, Stephens R, Rowland J, & Roffman R (2011). The influence of client behavior during motivational interviewing on marijuana treatment outcome. Addictive Behaviors, 36, 669–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiprovnick A, Kuerbis A, & Morgenstern J (2015). The effect of therapeutic bond within a brief intervention for alcohol moderation on drinking outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 29(1), 129–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Hartzler B, & Donovan D (2010). Matching motivation enhancement treatment to client motivation: re-examining the Project MATCH motivation matching hypothesis. Addiction, 105(8), 1403–1413. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02954.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Robins LN, Cottler LB, Sartorius N, Burke JD, Regier D, & trials P i. t. m. W. A. f. (1991). Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). British Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]