Abstract

Objective

Secukinumab, a fully human monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively neutralizes the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17A, has been approved in Europe in 2015 for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). This analysis assessed the budget impact of introduction of secukinumab to the Italian market for all three indications from the perspective of the Italian National Health Service.

Materials and methods

A cross-indication budget impact model was developed and included biologic-treated adult patients diagnosed with psoriasis, PsA, and AS. The analyses were conducted over a 3-year time horizon and included direct costs (drug therapy costs, administration costs, diseases-related costs, and adverse events costs). Model input parameters (epidemiology, market share projections, resource use, and costs) were obtained from the published literature and other Italian sources. The robustness of the results was tested via one-way sensitivity analyses: secukinumab cost, secukinumab market share, intravenous administration costs, and adverse events costs were varied by ±10%.

Results

The total patient population for secukinumab over the 3-year timeframe was projected to be 6,648 in the first year, increasing to 12,001 in the third year, for all three indications combined (psoriasis, PsA, and AS). Compared to a scenario without secukinumab in the market, the introduction of secukinumab in the market for the treatment of psoriasis, PsA, and AS showed a cumulative 3-year incremental budget impact of −5%, corresponding to savings of €66.1 million and per patient savings of about €1,855. The majority of the cost savings came from the adoption of secukinumab in AS (58%), followed by PsA (29%) and psoriasis (13%). Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of the results.

Conclusion

Results from this cross-indication budget impact model show that secukinumab is a cost-saving option for the treatment of PsA, AS, and psoriasis patients in Italy.

Keywords: budget impact, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Italy, secukinumab

Introduction

Psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory diseases associated with various comorbidities and worsening health-related quality of life (QoL).1–6 They are all generally chronic lifelong diseases having alternating flare-ups and periods of remission, resulting in reduced patients’ physical and psychological well-being, reduced work productivity, and higher health care costs in the longer term.7,8

Among these three diseases, psoriasis is the most common condition, which is estimated to affect between 0.7% and 2.9% of the population in Europe.9 It primarily manifests on the skin, resulting in plaques on the elbows, knees, or scalp, which may extend to other areas of the body.5,10,11 PsA and AS are part of spondyloarthritis (SpA), which are enthesitis driven, lifelong, painful, and debilitating immune-mediated inflammatory diseases affecting the joints and/or spine that can lead to irreversible structural bone damage caused by years of inflammation.6,12–15 The prevalence of PsA in the general population has been reported to range from 0.01% in Asia16 to 0.67% in Norway,17 while the prevalence of AS ranges from 0.1% to 1.4% globally.18

Psoriasis is associated with significant clinical and emotional morbidity, impacting patients’ work and social lives and reduces the QoL.19 Moreover, psoriasis is linked to other health conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease, and depression,20 further impacting the QoL of patients. Patients with PsA and AS experience pain, loss of physical function, and difficulty in performing activities of daily living, including the ability to work.6 Different studies have reported significant economic burden of psoriasis, PsA, and AS in different countries,21–26 including Italy.27,28 The economic and humanistic burden of SpA is closely connected to the functional status in PsA and AS patients, and it is increased by the fact that SpA usually occurs in active young adults.7,29–33 According to a survey performed in 17 out of the 20 regions in Italy, sponsored by the National Association of Rheumatic Patients, half of the patients with SpA reported disability and one third felt that their condition limited their career progression and personal development.34

Early efficacious treatments targeting inflammation control, prevention of comorbidities and complications, and function and social participation normalization are important in psoriasis, PsA, and AS management.35,36 The initial treatment for mild psoriasis includes topical steroids and phototherapy, whereas the initial treatment for moderate-to-severe psoriasis includes phototherapy and conventional systemic therapy, alone or in combination.37 In the past decade, the development of several drugs, biologics, and non-biologics has substantially improved the outcomes of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis.38 These include tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept, certolizumab, golimumab, and infliximab), interleukin (IL)-12 and 23 inhibitor (ustekinumab), and IL-17A inhibitors (secukinumab and ixekizumab). In addition, among non-biologics, apremilast improves the outcomes (see Table 1 for a list of currently approved and reimbursed treatments in Italy for each indication).37,39 Conventional pharmacologic treatment options for PsA and AS include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as the first-line treatment.40–43 For PsA, conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs are also used.40,41 Biologics are currently used for PsA and AS patients inadequately controlled by conventional treatments mentioned above/previously.

Table 1.

Approved indications and currently approved and reimbursed treatments for secukinumab in Italy, along with their posology

| Secukinumab indication | Currently approved and reimbursed treatments in Italy (maintenance year) |

|---|---|

| PsO: moderate-to-severe plaque Pso in adult patients who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy | Secukinumab 300 mg monthly, adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, etanercept 50 mg once weekly, ustekinumab 45 mg every 12 weeks, ustekinumab 90 mg every 12 weeks, infliximab 5 mg/kg, every 8 weeks |

| PsA: active PsA in adult patients when the response to previous DMARD therapy has been inadequate | Secukinumab 300 mg monthly for patients with concomitant moderate-to-severe plaque Pso or who are anti-TNFα IR, secukinumab 150 mg monthly for all other patients, adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, certolizumab 200 mg every 2 weeks, etanercept 50 mg once weekly, golimumab 50 mg monthly, ustekinumab 45 mg every 12 weeks, infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks, apremilasta 30 mg twice daily |

| AS: active AS in adults who have responded inadequately to conventional therapy | Secukinumab 150 mg monthly, adalimumab 40 mg every 2 weeks, certolizumab 200 mg every 2 weeks, etanercept 50 mg once weekly, golimumab 50 mg monthly, infliximab 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks |

Notes: Posology was obtained from products SmPC; please refer to last approved SmPC for loading doses where applied. Last reimbursement status for each drug can be found on the Italian Official Journal website.72

Not reimbursed in Pso, reimbursed in PsA for patients which are intolerant or inadequate to biologic therapies.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; IR, inadequate responders; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; Pso, psoriasis; SmPC, summary of product characteristics; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Secukinumab, a recombinant fully human monoclonal IgG1 antibody that selectively neutralizes the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17A constitutes an alternative and efficacious mechanism of action for the treatment of these immune-mediated inflammatory diseases.44 In 2015, secukinumab received market authorization in Europe for the treatment of adult patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis (300 mg), active PsA (150/300 mg), and active AS (150 mg), offering a new treatment option for these diseases and being the first non-TNF biologic for AS.44 Indeed, secukinumab is currently the only non-TNF biologic that is approved in all three indications. Ixekizumab, an IgG4 monoclonal antibody L-17A inhibitor, has been recently authorized for use in adults with active PsA in addition to moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis patients.45

Secukinumab has been shown to have significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate-to-severe psoriasis,46 PsA,47 and AS,48 demonstrating a rapid onset of action and sustained responses with a consistent safety profile, according to the results of several phase three clinical trials both vs placebo and comparators.46–54 In addition to its clinical value, secukinumab has been reported as a dominant or cost-effective treatment option compared to other biologics in multiple economic evaluations for the three indications.55–59 However secukinumab, being a biologic drug, is a costly treatment option and, in a context of limited resources, it is necessary to evaluate sustainability of its use.

This analysis aimed to estimate the budget impact of the introduction of secukinumab to the Italian market for the three indications (psoriasis, PsA and AS) over a 3-year time horizon from the perspective of Italian National Health Service (INHS).

Materials and methods

A cross-indication budget impact analysis (BIA) was developed by means of a dynamic simulation model in Microsoft Excel®. The model evaluated the budgetary impact of introducing secukinumab into the current approved and reimbursed treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis, active PsA, and active AS in Italy. The analysis was carried out from the perspective of the INHS over a 3-year timeframe. The model was populated with data available from literature and market research; therefore, no institutional review board or ethics committee approval was required. Model inputs included epidemiology data, current and future market share projections for treatments, data on resource use and on the following cost items (expressed in 2017 euros): drug therapy costs, administration costs, disease-related costs (resource use and associated costs), and adverse event (AE)-related costs.

Modeling framework

The budget impact model compared two different scenarios: 1) without secukinumab introduction (where secukinumab is not available as an alternative biologic treatment for psoriasis, PsA, and AS patients and 2) with the introduction of secukinumab (where secukinumab is available as an alternative biologic treatment for psoriasis, PsA, and AS patients, and secukinumab market share changes over time. The model compares the costs of the current and expected psoriasis, PsA, and AS treatment options over 3 years. The treatment regimens that were modeled included market shares of approved treatments including biosimilars (etanercept and infliximab biosimilars) and expected market shares after introduction of secukinumab to the market. For each licensed treatment, the indication-specific posology was taken from the summary of product characteristics from the European Medicines Agency (see Table 1).

For each disease, BIA was conducted for the first 3 years after secukinumab introduction. The total annual cost was obtained for each scenario, and the budget impact was estimated as the difference between the two scenarios, without and with secukinumab introduction into the Italian market, for the eligible population. Results are presented for all three indications combined and for each of the indications taken individually. The modeling framework and methods are consistent with the recommendations made by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research’s Task Force on Good Research Practices and are presented in Figure 1.60,61

Figure 1.

Model structure.

Notes: Initial population without secukinumab was based on national epidemiological data derived from ISTAT. Adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with psoriasis, PsA, and AS and currently treated with a biologic treatment were included in the BIA. The number of current psoriasis, PsA, and AS patients treated with different biologic drugs was obtained from the market share data (IQVIA 2016, Novartis data-processing). In the BIA, a formulary without secukinumab was compared to one with secukinumab (new formulary). A 3-year time horizon was considered for the analysis: market share related to 2016 was used and projection for the following 3 years was adopted. *Market share could be different for indication.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BIA, budget impact analysis; ISTAT, Italian National Statistical Institute; PMPY, per Member per Year; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

Model input data

Patient population and market shares

The size of initial population was based on national epidemiological data derived from Italian National Statistical Institute. Adult patients (aged ≥18 years) diagnosed with psoriasis, PsA, and AS and currently treated with a biologic treatment were included in the BIA. The number of current psoriasis, PsA, and AS patients treated with different biologic drugs was obtained from the market share data.62 The model also accounted for the incidence and new treatment starters for each indication. In order to estimate the number of patients treated over 3 years, yearly future growth rates of 17%, 10%, and 12% for psoriasis, PsA, and AS, respectively, were used on the basis of market research findings. Table 2 shows the input data on eligible population and market growth. Based on dynamic market research, 30% of patients were assumed as biologic-naïve patients.62 Detailed psoriasis, PsA, and AS population projections for both scenarios (with and without secukinumab) over the 3 years and the respective changing market share for all treatments are shown in Tables S1–S3.

Table 2.

Model input data on population

| Overall enrollees | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Italy (=18 years) | 50,657,518 | 50,961,14 | 51,267,232 | demo.istat.it |

| Disease | Value | Source | ||

| Psoriasis | ||||

| =18 years psoriasis patients | 2.90% | Saraceno et al 200873 | ||

| =18 years moderate–severe plaque psoriasis diagnosed patients | 20.00% | Khalid et al 201374 | ||

| =18 years moderate–severe plaque psoriasis patients on treatment with biologics | 4.20% | IQVIA, 2016 Novartis data-processing62 | ||

| Psoriasis market growth/new patients | 17.00% | Novartis market assumption | ||

|

| ||||

| PsA | ||||

| =18 years PsA patients | 0.42% | de Angelis et al 200775 | ||

| =18 years moderate–severe PsA diagnosed patients | 33.60% | IQVIA, 2016 data-processing, elaborazione Novartis62 | ||

| =18 years moderate–severe PsA patients on treatment with biologics | 16.00% | IQVIA, 2016 Novartis data-processing,62 | ||

| PsA market growth/new patients | 10.00% | Novartis market assumption | ||

|

| ||||

| AS | ||||

| =18 years AS patients | 0.37% | de Angelis et al 200775 | ||

| =18 years AS diagnosed patients | 80.00% | Expert opinion | ||

| =18 years AS patients on treatment with biologics | 4.98% | IQVIA, 2016 Novartis data-processing62 | ||

| AS market growth/new patients | 12.00% | Novartis market assumption | ||

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Costs

Only direct costs of the treatments were considered, including drugs costs, administration costs associated with intravenous (IV) infusions, disease-related costs (resource use and associated costs: non-biologic drugs, physician visits, emergency room visits, phototherapy), and AE costs.

Drugs costs

Drug acquisition costs were derived from official national price lists, and ex-factory prices were used (with −5%, −5% mandatory rebates). Induction and maintenance periods for each drug were taken into account in calculating drug costs. For the doses and administration schedules, summary of product characteristics was used. Table 3 shows the doses and cost per dose for the biologic treatments as well as apremilast, and concomitant non-biologic treatments. For infliximab, the dose of drug to be administered is established on the basis of the patient’s weight, and in our analysis it was obtained by considering the mean patients’ weight in the three indications (88.54 kg for psoriasis, 87.11 kg for PsA, and 81.57 kg for AS)

Table 3.

Doses and cost per dose for the biologic treatments as well as apremilast, and concomitant non-biologic treatments

| Biologic drugs

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment option | Doses

|

Cost per dose | Indication | |

| Year 1 | Year 2+ | |||

| Secukinumab 150 mg | 16 | 12 | €473.81 | PsA, AS |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | 16 | 12 | €947.63 | Psoriasis, PsA |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 26 | 26 | €482.19 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | 30 | 26 | €460.28 | PsA, AS |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 52 | 52 | €230.25 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 52 | 52 | €157.25 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Golimumab 50 mg | 12 | 12 | €1,044.19 | PsA, AS |

| Infliximab | 8 | 6 | €2,060.16 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Infliximab biosimilar | 8 | 6 | €1,545.12 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Ixekizumab | 18 | 13 | €962.07 | Psoriasis |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 6 | 4 | €2,042.88 | Psoriasis, PsA |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 52 | 52 | €230.25 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 52 | 52 | €157.25 | Psoriasis, PsA, AS |

| Apremilast 30 mg | 695 | 730 | €13.54 | PsA |

|

| ||||

|

Non-biologic drugs

| ||||

| Treatment option |

Doses

|

Cost per dose | Proportion | |

| Year 1 | Year 2+ | |||

|

| ||||

| NSAIDs | ||||

| Ibuprofen 400 mg | 1,095 | 1,095 | €1.64 | 25% |

| Diclofenac 100 mg | 365 | 365 | €2.61 | 25% |

| Indomethacin 125 mg | 365 | 365 | €3.7 | 25% |

| Naproxen 750 mg | 365 | 365 | €4.62 | 25% |

| DMARDs | ||||

| Methotrexate 7.5 mg | 52 | 52 | €3.83 | 60% |

| Sulfasalazine 500 mg | 1,419 | 1,461 | €0.08 | 20% |

| Leflunomide 20 mg | 377 | 365 | €1.11 | 20% |

Note: Gazzetta Ufficiale Italiana, Farmadati Italia ex-factory list price (with −5%, −5% mandatory rebates).

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; DMARDs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

No additional administration costs were considered for subcutaneous treatments, while for IV treatment (infliximab and its biosimilar), estimated administration cost per infusion was about €291 (discounted in 2017).63,64

Resource use and associated costs

To estimate the resource use impact for each indication, the proportion of patients requiring health care interventions along with the frequency were obtained. To estimate these costs, the unit costs were multiplied by the frequency and proportion of patients. Unit costs for each included item are available in Table S4.

AE costs

AEs such as serious infections, non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC), and malignancies other than NMSC were considered by individual event rates (see Table S5). Costs per event, obtained from National Diagnosis-Related Group tariffs (DRG 89, 284, 414), were €3,185, €773, and €2,194 for serious infections, NMSC, and malignancy other than NMSC, respectively.65

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

To assess the robustness of results, a one-way sensitivity analysis was performed by changing the following parameters by ±10%: secukinumab cost, secukinumab market share, IV administration costs, and AE costs. Moreover, in order to quantify the impact of a larger uptake of secukinumab in PsA and AS biologic-naïve patients, we carried out a scenario with twice as many PsA and AS biologic-naïve patients starting with secukinumab (60% compared to 30% in base case).

Results

Patients on secukinumab

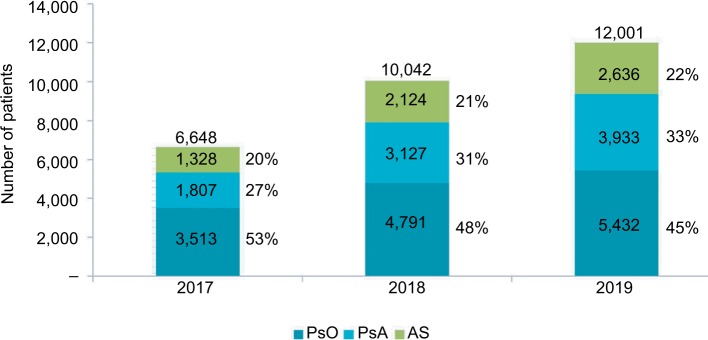

Combining all three indications (psoriasis, PsA, and AS), the total patient population in Italy treated with secukinumab over the 3-year timeframe was projected to be 6,648 in the first year, 10,042 in the second year, and 12,001 in the third year. Results are shown in detail in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Total patients treated with secukinumab over the 3-year timeframe in Italy.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriaris.

Budget impact analysis

Overall population

The introduction of secukinumab in Italy in psoriasis, PsA, and AS indications (all three combined) resulted in cumulative savings of 5% over the 3-year period, compared to the scenario without secukinumab in market (Table 4). This corresponds to per patient savings of about €1,855 and overall population savings of €66.1 million over the 3 years. The major proportion of cost savings was contributed by the adoption of secukinumab in AS (58%), followed by PsA (29%) and psoriasis (13%).

Table 4.

Budget impact results in the overall population (psoriasis, PsA, AS)

| Scenario without secukinumab

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost type | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Cumulative |

| Drug acquisition costs | €400,235,108 | €397,672,055 | €394,957,629 | €1,192,864,792 |

| Administration costs | €4,342,757 | €5,508,947 | €6,025,015 | €15,876,719 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €2,678,284 | €2,400,667 | €2,356,206 | €7,435,157 |

| Disease-related costs | €42,668,999 | €42,925,013 | €43,182,563 | €128,776,575 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €449,925,148 | €448,506,682 | €446,521,413 | €1,344,953,243 |

|

| ||||

| Scenario with secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €386,426,499 | €375,325,187 | €367,406,507 | €1,129,158,193 |

| Administration costs | €3,825,107 | €4,670,893 | €5,254,301 | €13,750,301 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €2,513,952 | €2,323,085 | €2,334,278 | €7,171,315 |

| Disease-related costs | €42,668,999 | €42,925,013 | €43,182,563 | €128,776,575 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €435,434,557 | €425,244,178 | €418,177,648 | €1,278,856,383 |

|

| ||||

| Incremental budget impact (ΔTOTAL) | −€14,490,592 | −€23,262,504 | −€28,343,765 | −€66,096,860 |

| Incremental budget impact-percentage | −3% | −5% | −6% | −5% |

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriasis

The introduction of secukinumab for moderate–severe plaque psoriasis treatment resulted in savings of 1% in the first year and 2% for the second and third year, compared to the scenario without secukinumab in market (Table 5). These correspond to savings of €1.9 million in the first year and savings increase in the following years, with €2.9 million and €3.5 million in the second and third years, respectively. The cumulative budget impact of introducing secukinumab is estimated to yield savings of €8.3 million over the 3-year period (Table 5). The cost savings per patient was €132 in the first year, €238 in the third year, and the cumulative result per patient was €568 over 3 years.

Table 5.

Budget impact results in psoriasis, PsA and AS populations

| Psoriasis

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario without secukinumab

| ||||

| Cost type | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Cumulative |

| Drug acquisition costs | €160,598,891 | €160,238,525 | €160,532,731 | €481,370,147 |

| Administration costs | €1,073,573 | €1,891,112 | €1,913,789 | €4,878,474 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €1,573,845 | €1,300,406 | €1,244,296 | €4,118,547 |

| Disease-related costs | €13,273,866 | €13,353,509 | €13,433,630 | €40,061,006 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €176,520,175 | €176,783,553 | €177,124,446 | €530,428,174 |

|

| ||||

| Scenario with secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €159,038,303 | €157,823,581 | €157,388,333 | €474,250,217 |

| Administration costs | €914,293 | €1,544,311 | €1,654,992 | €4,113,595 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €1,387,727 | €1,182,537 | €1,173,404 | €3,743,667 |

| Disease-related costs | €13,273,866 | €13,353,509 | €13,433,630 | €40,061,006 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €174,614,189 | €173,903,939 | €173,650,358 | €522,168,486 |

|

| ||||

| Incremental budget impact (ΔTOTAL) | −€1,905,986 | −€2,879,614 | −€3,474,088 | −€8,259,688 |

| Incremental budget impact-percentage | −1% | −2% | −2% | −2% |

|

| ||||

| PsA | ||||

|

| ||||

| Scenario without secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cost type | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Cumulative |

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €143,587,227 | €142,366,020 | €140,297,479 | €426,250,726 |

| Administration costs | €1,546,523 | €1,893,814 | €1,916,392 | €5,356,730 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €835,171 | €843,274 | €848,486 | €2,526,931 |

| Disease-related costs | €20,047,089 | €20,167,372 | €20,288,376 | €60,502,837 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €166,016,011 | €165,270,480 | €163,350,732 | €494,637,223 |

|

| ||||

| Scenario with secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €139,575,949 | €135,570,840 | €132,204,159 | €407,350,947 |

| Administration costs | €1,403,927 | €1,658,146 | €1,763,156 | €4,825,228 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €852,602 | €872,383 | €884,689 | €2,609,673 |

| Disease-related costs | €20,047,089 | €20,167,372 | €20,288,376 | €60,502,837 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €161,879,566 | €158,268,740 | €155,140,379 | €475,288,686 |

|

| ||||

| Incremental budget impact (ΔTOTAL) | −€4,136,444 | −€7,001,740 | −€8,210,353 | −€19,348,538 |

| Incremental budget impact-percentage | −2% | −4% | `−5% | −4% |

|

| ||||

| AS | ||||

|

| ||||

| Scenario without secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cost type | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Cumulative |

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €96,048,990 | €95,067,510 | €94,127,419 | €285,243,919 |

| Administration costs | €1,722,661 | €1,724,020 | €2,194,834 | €5,641,515 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €269,268 | €256,987 | €263,424 | €789,679 |

| Disease-related costs | €9,348,044 | €9,404,132 | €9,460,557 | €28,212,732 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €107,388,963 | €106,452,649 | €106,046,234 | €319,887,846 |

|

| ||||

| Scenario with secukinumab | ||||

|

| ||||

| Drug acquisition costs | €87,812,247 | €81,930,766 | €77,814,015 | €247,557,028 |

| Administration costs | €1,506,887 | €1,468,436 | €1,836,154 | €4,811,478 |

| Adverse event-related costs | €273,623 | €268,165 | €276,185 | €817,974 |

| Disease-related costs | €9,348,044 | €9,404,132 | €9,460,557 | €28,212,732 |

|

| ||||

| Total | €98,940,802 | €93,071,499 | €89,386,911 | €281,399,212 |

|

| ||||

| Incremental budget impact (ΔTOT) | −€8,448,161 | −€13,381,149 | −€16,659,324 | −€38,488,634 |

| Incremental budget impact-percentage | −8% | −13% | −16% | −12% |

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis

The introduction of secukinumab for the treatment of PsA reveals savings of 2% in the first year, 4% in the second year, and 5% in the third year, compared to the scenario without secukinumab in market. These correspond to savings of €4.1 million in the first year and savings increase in the following years, with €7 million and €8.2 million in the second and third years, respectively. The cumulative budget impact of introducing secukinumab is estimated to yield savings of €19.3 million over the 3-year period (Table 5). Cost savings per patient were €329 in the first year, increasing to €645 in the third year with the cumulative per patient savings of €1,527 over 3 years.

Ankylosing spondylitis

The introduction of secukinumab for treatment of AS reveals savings of 8% in the first year, 13% in the second year, and 16% in the third year, compared to the scenario without secukinumab in market. These correspond to savings of €8.4 million in the first year and savings increase in the following years, with €13.4 million and €16.7 million in the second and third years, respectively. The cumulative budget impact of introducing secukinumab is estimated to yield savings of €38.5 million over the 3-year period (Table 5). Per patient cost results showed savings of €1,010 in the first year, which increased to €1,968 in the third year with the cumulative per patient savings of €4,568 over 3 years.

Sensitivity and scenario analyses

In Figure 3, a tornado diagram shows one-way sensitivity analysis results for the overall population scenario (com bining patients with all three indications). This analysis demonstrated that budget impact results were most sensitive to change in secukinumab cost and the cost of secukinumab was the main cost driver in the analysis.

Figure 3.

Tornado diagram for the sensitivity analysis results: ±10% variation of parameters in the overall per member BI scenario.

Notes: BI per member cumulative result in the overall population (combining three indications): €1,855. Tornado diagram is useful to compare the relative importance of variables considered in sensitivity analysis. For each variable, we estimated the effect of a ±10% change from BI baseline.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; BI: budget impact; IV, intravenous.

To assess the impact of a potential growth of biologic-naïve patients, twice the number of secukinumab AS and PsA biologic-naïve patients was assumed compared to that in base case scenario (in base case, 30% of PsA and AS eligible patients were biologic-naïve). With regard to combined PsA and AS population, the increase in biologic-naïve patients resulted in incremental cumulative savings of about €27.7 million over 3 years against base case scenario (€93.8 vs €66.1 million), as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

BIA results: base case vs twice PsA and AS biologic-naïve patients starting with secukinumab (150 mg secukinumab uptake)

| Scenario | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Cumulative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Base case | ||||

| Without secukinumab | €449,925,148 | €448,506,682 | €446,521,413 | €1,344,953,243 |

| With secukinumab | €435,434,557 | €425,244,178 | €418,177,648 | €1,278,856,383 |

| Incremental budget impact | −€14,490,592 | −€23,262,504 | −€28,343,765 | −€66,096,860 |

| Incremental budget impact - percentage | −3% | −5% | −6% | −5% |

|

| ||||

| B. Twice PsA and AS biologic-naïve patients (150 mg secukinumab uptake) | ||||

| Without secukinumab | €450,086,778 | €449,029,143 | €447,526,843 | €1,346,642,764 |

| With secukinumab | €429,718,477 | €416,014,237 | €407,146,774 | €1,252,879,488 |

| Incremental budget impact | −€20,368,301 | −€33,014,905 | −€40,380,070 | −€93,763,276 |

| Incremental budget impact - percentage | −5% | −7% | −9% | −7% |

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

The increase of PsA biologic-naïve population led to incremental cumulative savings of €16.2 million over the 3 years against base case scenario (€35.5 vs €19.3 million). Therefore, the market share assumed for secukinumab changed from 14.4%, 24.7%, and 30.9% in base case to 18.7%, 32.1%, and 40.2% in the first, second, and third year, respectively. With regard to AS population, the increase in biologic-naïve patients resulted in incremental cumulative savings of €11.5 million over the 3 years against base case scenario (€50 vs €38.5 million). In this case, market share for secukinumab 150 mg changed from 15.9%, 25.2%, and 31.1% in base case to 20.6%, 32.8%, and 40.5% in the first, second, and third year, respectively.

Discussion

This analysis demonstrated considerable cost savings for INHS with the introduction of secukinumab in the market for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis, PsA, and AS. Considering total direct medical costs from the INHS perspective, cumulative savings resulted to about €66.1 million after 3 years of secukinumab introduction. The highest savings were observed in AS patients (€38.5 million), followed by PsA (€19.3 million) and psoriasis (€8.3 million) patients. Within a fixed health care budget, such savings with the introduction of secukinumab could allow treatment of more patients with psoriasis, PsA, and AS in Italy. Potentially with these aforementioned savings, approximately an additional 5,925 patients (230 for psoriasis, 392 for PsA, and 5,302 for AS) could be treated. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the base case findings in most cases, and secukinumab cost was found to be the main cost driver in the analysis. As revealed in alternative scenario analysis, the savings could potentially increase if secukinumab would be used more in biologic-naïve AS and PsA patients, thus providing a better cost-saving treatment. In view of the strong clinical and comparative evidence provided by several randomized controlled trials supporting the efficacy and safety of secukinumab for psoriasis, PsA, and AS treatment,46,48–54,66–69 this analysis showed the budget impact of the introduction of secukinumab from the INHS perspective.

The budget impact model results presented in this analysis were consistent with other recent studies available in literature from different countries. Duteil et al70 assessed the budget impact of the introduction of secukinumab for patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, AS, and PsA in France. This analysis demonstrated that secukinumab utilization led to savings of €83.6 million over a 6-year time period. Halliday et al71 estimated the budget impact of introduction of secukinumab in the UK in patients with AS. The cumulative budget savings over a 5-year period were estimated to be €49.2 million.

There are few limitations of this analysis. Outcomes of the analysis are based on population and market share projections. Some input data were not available to Italian context, and when not available, data from other countries or assumptions were entered into the model. Furthermore, there could be a limit in the identification of the target population, as the model has considered separately the psoriasis, PsA, and AS populations, and there is lack of studies able to provide information regarding patients on treatment with simultaneous presence of these diseases.

The BIA, according to the INHS perspective, included only direct costs. In view of the huge impact on work productivity of these diseases, potential savings could be higher if we had included indirect costs as well. Therefore, it would be interesting to plan further analyses taking into account total costs to define the composition of direct and indirect costs and the real burden on patients and the Italian society. Although the robustness of results was confirmed by sensitivity analysis, real-world evidence could further confirm our assumptions and results in future.

In conclusion, this analysis demonstrated that secukinumab is a cost-saving option for INHS when introduced for psoriasis, PsA, and AS treatment, particularly cost-savings was the highest in AS and PsA patients.

Supplementary materials

Table S1.

PsO population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | – | – | – | 3,513 (24.3%) | 4,791 (33.0%) | 5,432 (37.2%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 4,100 (28.4%) | 2,176 (15.0%) | 2,331 (16.0%) | 3,057 (21.2%) | 1,387 (9.6%) | 1,341 (9.2%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 2,827 (19.6%) | 1,849 (12.7%) | 1,124 (7.7%) | 2,108 (14.6%) | 1,179 (8.1%) | 647 (4.4%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 352 (2.4%) | 735 (5.1%) | 1,026 (7.0%) | 352 (2.4%) | 735 (5.1%) | 1,026 (7.0%) |

| Ixekizumab | 793 (5.5%) | 2,689 (18.5%) | 3,668 (25.1%) | 591 (4.1%) | 1,714 (11.8%) | 2,111 (14.5%) |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 5,711 (39.6%) | 5,928 (40.8%) | 5,300 (36.3%) | 4,258 (29.5%) | 3,779 (26.0%) | 3,049 (20.9%) |

| Infliximab | 377 (2.6%) | 577 (4.0%) | 367 (2.5%) | 281 (2.0%) | 368 (2.5%) | 211 (1.4%) |

| Infliximab biosimilar | 270 (1.9%) | 563 (3.9%) | 786 (5.4%) | 270 (1.9%) | 563 (3.9%) | 786 (5.4%) |

| Total | 14,430 (100.0%) | 14,517 (100.0%) | 14,604 (100.0%) | 14,430 (100.0%) | 14,517 (100.0%) | 14,604 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: PsO, psoriasis.

Table S2.

PsA population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 542 (4.3%) | 938 (7.4%) | 1,180 (9.3%) |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | – | – | – | 1,265 (10.0%) | 2,189 (17.3%) | 2,753 (21.6%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 3,997 (31.8%) | 3,839 (30.3%) | 3,823 (30.0%) | 3,389 (26.9%) | 2,791 (22.1%) | 2,456 (19.3%) |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | 537 (4.3%) | 495 (3.9%) | 246 (1.9%) | 455 (3.6%) | 360 (2.8%) | 158 (1.2%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 3,513 (11.2%) | 3,219 (10.2%) | 3,288 (5.0%) | 2,978 (9.5%) | 2,341 (7.4%) | 2,112 (3.2%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 351 (27.9%) | 593 (25.4%) | 856 (25.8%) | 351 (23.7%) | 593 (18.5%) | 856 (16.6%) |

| Golimumab 50 mg | 1,404 (2.8%) | 1,294 (4.7%) | 642 (6.7%) | 1,190 (2.8%) | 941 (4.7%) | 413 (6.7%) |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 1,443 (11.5%) | 1,465 (11.6%) | 1,760 (13.8%) | 1,223 (9.7%) | 1,065 (8.4%) | 1,131 (8.9%) |

| Infliximab | 554 (4.4%) | 511 (4.0%) | 253 (2.0%) | 470 (3.7%) | 371 (2.9%) | 163 (1.3%) |

| Infliximab bios | 361 (2.9%) | 610 (4.8%) | 880 (6.9%) | 361 (2.9%) | 610 (4.8%) | 880 (6.9%) |

| Apremilast 30 mg | 422 (3.4%) | 631 (5.0%) | 984 (7.7%) | 358 (2.8%) | 459 (3.6%) | 632 (5.0%) |

| Total | 12,582 (100.0%) | 12,657 (100.0%) | 12,733 (100.0%) | 12,582 (100.0%) | 12,657 (100.0%) | 12,733 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Table S3.

AS population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 1,328 (15.9%) | 2,124 (25.2%) | 2,636 (31.1%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 3,045 (36.4%) | 3,184 (37.8%) | 2,856 (33.7%) | 2,530 (30.2%) | 2,279 (27.1%) | 1,788 (21.1%) |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | 421 (5.0%) | 297 (3.5%) | 317 (3.7%) | 350 (4.2%) | 212 (2.5%) | 198 (2.3%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 2,363 (28.2%) | 2,564 (30.5%) | 2,358 (27.9%) | 1,963 (23.5%) | 1,835 (21.8%) | 1,477 (17.4%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 245 (2.9%) | 452 (5.4%) | 677 (8.0%) | 245 (2.9%) | 452 (5.4%) | 677 (8.0%) |

| Golimumab 50 mg | 1,266 (15.1%) | 892 (10.6%) | 952 (11.2%) | 1,052 (12.6%) | 639 (7.6%) | 596 (7.0%) |

| Infliximab | 759 (9.1%) | 535 (6.4%) | 571 (6.7%) | 631 (7.5%) | 383 (4.5%) | 358 (4.2%) |

| Infliximab bios | 266 (3.2%) | 491 (5.8%) | 735 (8.7%) | 266 (3.2%) | 491 (5.8%) | 735 (8.7%) |

| Total | 8,365 (100.0%) | 8,415 (100.0%) | 8,466 (100.0%) | 8,365 (100.0%) | 8,415 (100.0%) | 8,466 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: AS, ankylosing spondylitis.

Table S4.

Resource use and costs associated with PsO, PsA, and AS treatment

| Component | PsO

|

PsA

|

AS

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | |

| Physician visit | 10 | 5.0 | €66.00 | 100 | 10.7 | €66.00 | 100 | 10.8 | €66.00 |

| Emergency room visit | – | – | – | 20 | 1.8 | €241.05 | 22 | 2 | €241.05 |

| Phototherapy (narrow band UVB) | 16 | 24.0 | €54.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NSAIDsa | 45 | – | €1,446.31 | 52 | – | €1,446.31 | 22 | – | €1,446.31 |

| DMARDsa | 45 | – | €223.90 | 52 | – | €223.90 | 22 | – | €223.90 |

Notes: Cost data obtained from Italian national formulary;1 phototherapy-related data from De Compadri and Koleva;2 frequency data for PsO from NICE clinical guidance3 and for PsA and AS from Greenberg et al.4

For NSAIDs and DMARDs, cost has been estimated as weighted cost as the global model.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugl NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

Table S5.

Annual rates of adverse events associated with PsO, PsA, and AS treatment

| Treatment option | PsO

|

PsA

|

AS

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious infection | NMSC | Malignancies other than NMSC | Serious infection | NMSC | Serious infection | NMSC | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 1.4%6 | 2.1%6 | 0.9%7 | 0.9%7 |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | 1.4%8 | 0.4%8 | 0.3%8 | 2.8%6 | 0.0%6 | – | – |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 5.2%a | 0.9%a | 0.6%a | 2.8%9 | 0.1%9 | 1.4%9 | 0.5%9 |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | – | – | – | 3.1%10 | 0.0%10 | 3.9%11 | 0.0%11 |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 5.1%a | 3.5%a | 0.0%a | 1.7%12 | 0.6%12 | 0.0%13 | 0.0%13 |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 5.1%b | 3.5%b | 0.0%b | 1.7%b | 0.6%b | 0.0%b | 0.0%b |

| Golimumab 50 mg | – | – | – | 1.4%14 | 0.0%14 | 0.4%15 | 0.0%15 |

| Ixekizumab | 0.02%a | 0.0%a | 0.0%a | – | – | – | – |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 0.0%a | 0.5%a | 0.6%a | 0.8%16 | 0.4%16 | – | – |

| Infliximab | 5.5%a | 0.4%a | 7.7%a | 1.9%17 | 1.9%17 | 2.1%18 | 0%18 |

| Infliximab bios | 5.5%b | 0.4%b | 7.7%b | 1.9%b | 1.9%b | 2.1%b | 0%b |

| Apremilast 30 mg | – | – | – | 2.6%19 | 1.3%19 | – | – |

Notes: Only serious adverse events due to malignancies and severe infections requiring hospitalization were included in the analysis. Severe infections included sepsis, tuberculosis, skin and soft tissue infections, bone and joint infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections.

Data obtained from product label.

Assumed same as corresponding branded drug. “–” Indicates a treatment (at a given dose strength) is not considered for the indication mentioned.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

References

- 1.Italian National Formulary 2015 (physician visit) 2015. [Accessed March 25, 2018]. Available from: www.mattoni.salute.gov.it/mattoni/documenti/11_Valutazi-one_costi_dell_emergenza.pdf (ER visit)

- 2.De Compadri P, Koleva D. I costi della psoriasis vulgaris nei pazienti sottoposti a terapia sistemica: una rassegna della letteratura e una stima preliminare di costo in Italia [The costs of psoriasis vulgaris in patients receiving systemic therapy: a review of the literature and a preliminary cost estimate in Italy] Quaderni di farmaco economia. 2008;6:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Clinical Guideline Centre . Psoriasis: Assessment and Management of Psoriasis. London: Royal College of Physicians (UK); 2012. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Guidance. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greenberg JD, Palmer JB, Li Y, Herrera V, Tsang Y, Liao M. Healthcare resource use and direct costs in patients with ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis in a large US cohort. J Rheumatol. 2016;43(1):88–96. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McInnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(26):2534–2548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Kerkhof PC, Griffiths CE, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab long-term safety experience: a pooled analysis of 10 Phase II and III clinical studies in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(1):83–98.e84. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burmester GR, Panaccione R, Gordon KB, McIlraith MJ, Lacerda AP. Adalimumab: long-term safety in 23 458 patients from global clinical trials in rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’s disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(4):517–524. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mease PJ, Fleischmann R, Deodhar AA, et al. Effect of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis: 24-week results of a Phase 3 double-blind randomised placebo-controlled study (RAPID-PsA) Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):48–55. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landewe R, Braun J, Deodhar A, et al. Efficacy of certolizumab pegol on signs and symptoms of axial spondyloarthritis including ankylosing spondylitis: 24-week results of a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled Phase 3 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(1):39–47. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterry W, Ortonne JP, Kirkham B, et al. Comparison of two etanercept regimens for treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: PRESTA randomised double blind multicentre trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c147. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braun J, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Huang F, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of etanercept versus sulfasalazine in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized, double-blind trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(6):1543–1551. doi: 10.1002/art.30223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kavanaugh A, van der Heijde D, McInnes IB, et al. Golimumab in psoriatic arthritis: one-year clinical efficacy, radiographic, and safety results from a Phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(8):2504–2517. doi: 10.1002/art.34436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun J, Deodhar A, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 104-week results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(5):661–667. doi: 10.1136/ard.2011.154799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the Phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):990–999. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Torii H, Nakagawa H, Japanese Infliximab Study investigators Inflix-imab monotherapy in Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter trial. J Dermatol Sci. 2010;59(1):40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun J, Deodhar A, Dijkmans B, et al. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over a two-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(9):1270–1278. doi: 10.1002/art.24001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a Phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73(6):1020–1026. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-205056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab inhibition of interleukin-17A in patients with psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(14):1329–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Alessandro Roccia from Novartis Pharma Italy, Martina Oselin and M Chiara Valentino from S.A.V.E. Research Center, and Niraj Modi from Novartis Healthcare Private Limited, Hyderabad for editorial writing support. This analysis was funded by Novartis Pharma S.p.A., Origgio, Italy.

Footnotes

Authors contributions

SMJ and PG designed the original model framework. SDM adapted the model to the Italian perspective. GLC reviewed and validated the model adaptation and wrote the manuscript. CM supported the model adaptation and in writing the manuscript. MN interpreted the data and decided on manuscript content and structure. GMB supervised the project and helped in writing the manuscript. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

GLC, GMB, CM, and SDM are employees of S.A.V.E. S.r.l and consultants for Novartis. SMJ is an employee and shareholder of Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. PG is an employee of Novartis Product Life Cycle Services-NBS, Novartis Healthcare Private Limited, Hyderabad, India. MN is an employee of Novartis Pharma, Origgio, Italy. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.de Korte J, Mombers FMC, Bos JD, Sprangers MAG. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9(2):140–147. doi: 10.1046/j.1087-0024.2003.09110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sw H, Holt EW, Husni ME, Qureshi AA. Willingness-to-pay stated preferences for 8 health-related quality-of-life domains in psoriatic arthritis: a pilot study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2010;39(5):384–397. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Husted JA, Thavaneswaran A, Chandran V, Gladman DD. Incremental effects of comorbidity on quality of life in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2013;40(8):1349–1356. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.121500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gratacós J, Daudén E, Gómez-Reino J, Moreno JC, Casado Miguel Ángel, Rodríguez-Valverde V. Health-related quality of life in psoriatic arthritis patients in Spain. Reumatol Clín. 2014;10(1):25–31. doi: 10.1016/j.reuma.2013.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boehncke W-H, Schön MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–994. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61909-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg N, van den Bosch F, Deodhar A. The concept of spondyloarthritis: Where are we now? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(5):663–672. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huscher D, Merkesdal S, Thiele K, et al. Cost of illness in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus in Germany. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65(9):1175–1183. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.046367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franke LC, Ament AJ, van de Laar MA, Boonen A, Severens JL. Cost-of-illness of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009;27(4 Suppl 55):S118–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(2):377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gudjonsson JE, Johnston A, Sigmundsdottir H, Valdimarsson H. Immunopathogenic mechanisms in psoriasis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farley E, Menter A. Psoriasis: comorbidities and associations. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011;146(1):9–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mease PJ, Armstrong AW. Managing patients with psoriatic disease: the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis. Drugs. 2014;74(4):423–441. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0191-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvadorini G, Bandinelli F, delle Sedie A, et al. Ankylosing spondylitis: how diagnostic and therapeutic delay have changed over the last six decades. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(4):561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, Baraliakos X, et al. The early disease stage in axial spondylarthritis: Results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2009;60(3):717–727. doi: 10.1002/art.24483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schett G, Lories RJ, D’Agostino M-A, et al. Enthesitis: from pathophysiology to treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2017;13(12):731–741. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2017.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng Q, Chen R, Darmawan J, et al. Rheumatic diseases in China. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(1):R17. doi: 10.1186/ar2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoff M, Gulati AM, Romundstad PR, Kavanaugh A, Haugeberg G. Prevalence and incidence rates of psoriatic arthritis in central Norway: data from the Nord-Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT) Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(1):60–64. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akkoc N. Are spondyloarthropathies as common as rheumatoid arthritis worldwide? A review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(5):371–378. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazard E, Cherry SB, Lalla D, Woolley JM, Wilfehrt H, Chiou CF. Clinical and economic burden of psoriasis. Manag Care Interface. 2006;19(4):20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mdefspde Oliveira, Bdeo Rocha, Duarte GV. Psoriasis: classical and emerging comorbidities. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(1):9–20. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghatnekar O, Ljungberg A, Wirestrand LE, Svensson A. Costs and quality of life for psoriatic patients at different degrees of severity in southern Sweden – a cross-sectional study. Eur J Dermatol. 2012;22(2):238–245. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berger K, Ehlken B, Kugland B, Augustin M. Cost-of-illness in patients with moderate and severe chronic psoriasis vulgaris in Germany. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3(7):511–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2005.05729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy AR, Davie AM, Brazier NC, et al. Economic burden of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Canada. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(12):1432–1440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poole CD, Lebmeier M, Ara R, Rafia R, Currie CJ. Estimation of health care costs as a function of disease severity in people with psoriatic arthritis in the UK. Rheumatology. 2010;49(10):1949–1956. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boonen A, et al. Direct costs of ankylosing spondylitis and its determinants: an analysis among three European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(8):732–740. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.8.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobelt G, Andlin-Sobocki P, Maksymowych WP. Costs and quality of life of patients with ankylosing spondylitis in Canada. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):289–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colombo G, et al. Moderate and severe plaque psoriasis: cost-of-illness study in Italy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(2):559–568. doi: 10.2147/tcrm.s2740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olivieri I, de Portu S, Salvarani C, et al. The psoriatic arthritis cost evaluation study: a cost-of-illness study on tumour necrosis factor inhibitors in psoriatic arthritis patients with inadequate response to conventional therapy. Rheumatology. 2008;47(11):1664–1670. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Conaghan P, Alten R, Strand V. The relationship between physical functioning and work for people with psoriatic arthritis: results from a large real-world study in 16 countries [Abstract 1712] Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cortesi PA, Scalone L, D’Angiolella L, et al. Systematic literature review on economic implications and pharmacoeconomic issues of psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30(4 Suppl 73):S126–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Altobelli E, Maccarone M, Petrocelli R, et al. Analysis of health care and actual needs of patients with psoriasis: a survey on the Italian population. BMC Public Health. 2007;7(1):59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-7-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burgos-Pol R, Martínez-Sesmero JM, Ventura-Cerdá JM, Elías I, Caloto MT, Casado M. Á. The cost of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in 5 European countries: a systematic review. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107(7):577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.ad.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams EM, Walker RJ, Faith T, Egede LE. The impact of arthritis and joint pain on individual healthcare expenditures: findings from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), 2011. Arthritis Res Ther. 2017;19(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s13075-017-1230-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramonda R, Marchesoni A, Carletto A, et al. Patient-reported impact of spondyloarthritis on work disability and working life: the ATLANTIS survey. Arthritis Res Ther. 2016;18(1):78. doi: 10.1186/s13075-016-0977-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smolen JS, Schöls M, Braun J, et al. Treating axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis, especially psoriatic arthritis, to target: 2017 update of recommendations by an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(1):3–17. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Avede Carvalho, Romiti R, Cdas Souza, et al. Psoriasis comorbidities: complications and benefits of immunobiological treatment. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(6):781–789. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mrowietz U. Implementing treatment goals for successful long-term management of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26(Suppl 3):12–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Norlin JM, Steen Carlsson K, Persson U, Schmitt-Egenolf M. Switch to biological agent in psoriasis significantly improved clinical and patient-reported outcomes in real-world practice. Dermatology. 2012;225(4):326–332. doi: 10.1159/000345715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CH, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Yiu ZZ, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2017. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(3):628–636. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):499–510. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(5):1060–1071. doi: 10.1002/art.39573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, et al. American College of Rheumatology/Spondylitis Association of America/Spondyloarthritis Research and Treatment Network 2015 recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(2):282–298. doi: 10.1002/art.39298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):978–991. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cosentyx Summary of Product Characteristics. [Accessed March 25, 2018]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/003729/WC500183132.pdf.

- 45.Taltz – update from EMA regarding adoptation of new indication for Taltz. 2017. [Accessed March 25, 2018]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/003729/WC500183132.pdf.

- 46.Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis – results of two Phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed. 2014;371(4):326–338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mease PJ, Mcinnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab Inhibition of Interleukin-17A in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed. 2015;373(14):1329–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed. 2015;373(26):2534–2548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thaçi D, Blauvelt A, Reich K, et al. Secukinumab is superior to ustekinumab in clearing skin of subjects with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: CLEAR, a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(3):400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Strand V, Mease P, Gossec L, et al. Secukinumab improves patient-reported outcomes in subjects with active psoriatic arthritis: results from a randomised Phase III trial (FUTURE 1) Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(1):203–207. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-209055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mcinnes IB, Mease PJ, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab, a human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriatic arthritis (FUTURE 2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9999):1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61134-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mcinnes IB, Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT, et al. Secukinumab sustains improvement in signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: 2 year results from the Phase 3 FUTURE 2 study. Rheumatology. 2017;56(11):1993–2003. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deodhar AA, Dougados M, Baeten DL, et al. Effect of secukinumab on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active ankylosing spondylitis: a Phase III randomized trial (MEASURE 1) Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(12):2901–2910. doi: 10.1002/art.39805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sieper J, Deodhar A, Marzo-Ortega H, et al. Secukinumab efficacy in anti-TNF-naive and anti-TNF-experienced subjects with active ankylosing spondylitis: results from the MEASURE 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(3):571–592. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Puig L, Notario J, Jiménez-Morales A, et al. Secukinumab is the most efficient treatment for achieving clear skin in psoriatic patients: a cost-consequence study from the Spanish National Health Service. J Dermatolog Treat. 2017;28(7):623–630. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1364687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goeree R, Chiva-Razavi S, Gunda P, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of secukinumab for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis: a Canadian perspective. J Med Econ. 2018;21(2):163–173. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1384737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D’Ausilio A, Aiello A, Daniel F, Graham C, Roccia A, Toumi M. A cost-effectiveness analysis of secukinumab 300 mg vs current therapies for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Italy. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A424. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee A, Gregory V, Gu Q, Becker DL, Barbeau M. Cost-effectiveness of secukinumab compared to current treatments for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in Canada. Value Health. 2015;18(3):A182. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costa-Scharplatz M, Lang A, Gustavsson A, Fasth A. Cost-effectiveness of secukinumab compared to ustekinumab in patients with psoriasis from a Swedish health care perspective. Value Health. 2015;18(7):A422. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mauskopf JA, Sullivan SD, Annemans L, et al. Principles of good practice for budget impact analysis: report of the ISPOR Task Force on good research practices – budget impact analysis. Value Health. 2007;10(5):336–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sullivan SD, Mauskopf JA, Augustovski F, et al. Budget impact analysis – principles of good practice: report of the ISPOR 2012 Budget Impact Analysis Good Practice II Task Force. Value Health. 2014;17(1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2013.08.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.IMS Health Data Processing. Novartis; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Favalli EG, Marchesoni A, Colombo GL, Sinigaglia L. Pattern of use, economic burden and vial optimization of infliximab for rheumatoid arthritis in Italy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2008;26(1):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.De Compadri P, Koleva D. I costi della psoriasis vulgaris nei pazienti sottoposti a terapia sistemica: una rassegna della letteratura e una stima preliminare di costo in Italia [The costs of psoriasis vulgaris in patients receiving systemic therapy: a review of the literature and a preliminary cost estimate in Italy] Quaderni di farmaco economia. 2008;6:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ministry of Health Tariffs of acute hospital care services [DRG tariffs] Official Journal of the Italian Republic. Series N.23; Supplement 8 of 28 January 2013. [Accessed March 25, 2018]. Available from: http://www.salute.gov.it/portale/temi/p2_6.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=1349&area=ricoveriOspedalieri&menu=sistema.

- 66.Nash P, Mcinnes I, Mease P, et al. Secukinumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: comparative effectiveness versus adalimumab using a matching-adjusted indirect comparison. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68(Suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mcinnes IB, Nash P, Ritchlin C, et al. THU0437 secukinumab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: comparative effectiveness results versus licensed biologics and apremilast from a network meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(Suppl 2):348–349. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hawe E, Vickers AD, Mallya UG, McBride DW, Capkun-Niggli G, Olson M. Secukinumab 300 mg demonstrates highest probability of efficacy than other biologics in psoriasis: indirect comparison. Paper presented as a poster at the 23rd European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology Congress; October; Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Baeten D, Mease P, Strand V, et al. SAT0390 secukinumab for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: comparative effectiveness results versus currently licensed biologics from a network meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(Suppl 2):809–810. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Duteil E, Rachdi L, Cariou C, et al. Budget impact analysis of secukinumab in moderate to severe plaque psoriaris, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis In France. Value in Health. 2016;19(7):A458. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Halliday A, Hacking V, Jugl SM, et al. Budget impact of secukinumab for ankylosing spondylitis in the UK. Value in Health. 2016;19(7):A535. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Italian Republic Official Gazette. [Accessed March 25, 2018]. Available from: http://www.gazzettauf-ficiale.it/ricerca/atto/serie_generale/originario?reset=true&normativi=false.

- 73.Saraceno R, Mannheimer R, Chimenti S. Regional distribution of psoriasis in Italy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008;22(3):324–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khalid JM, Globe G, Fox KM, Chau D, Maguire A, Chiou C-F. Treatment and referral patterns for psoriasis in United Kingdom primary care: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Dermatol. 2013;13(1):9. doi: 10.1186/1471-5945-13-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.de Angelis R, Salaffi F, Grassi W. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in an Italian population sample: a regional community-based study. Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36(1):14–21. doi: 10.1080/03009740600904243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

PsO population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | – | – | – | 3,513 (24.3%) | 4,791 (33.0%) | 5,432 (37.2%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 4,100 (28.4%) | 2,176 (15.0%) | 2,331 (16.0%) | 3,057 (21.2%) | 1,387 (9.6%) | 1,341 (9.2%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 2,827 (19.6%) | 1,849 (12.7%) | 1,124 (7.7%) | 2,108 (14.6%) | 1,179 (8.1%) | 647 (4.4%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 352 (2.4%) | 735 (5.1%) | 1,026 (7.0%) | 352 (2.4%) | 735 (5.1%) | 1,026 (7.0%) |

| Ixekizumab | 793 (5.5%) | 2,689 (18.5%) | 3,668 (25.1%) | 591 (4.1%) | 1,714 (11.8%) | 2,111 (14.5%) |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 5,711 (39.6%) | 5,928 (40.8%) | 5,300 (36.3%) | 4,258 (29.5%) | 3,779 (26.0%) | 3,049 (20.9%) |

| Infliximab | 377 (2.6%) | 577 (4.0%) | 367 (2.5%) | 281 (2.0%) | 368 (2.5%) | 211 (1.4%) |

| Infliximab biosimilar | 270 (1.9%) | 563 (3.9%) | 786 (5.4%) | 270 (1.9%) | 563 (3.9%) | 786 (5.4%) |

| Total | 14,430 (100.0%) | 14,517 (100.0%) | 14,604 (100.0%) | 14,430 (100.0%) | 14,517 (100.0%) | 14,604 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: PsO, psoriasis.

Table S2.

PsA population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 542 (4.3%) | 938 (7.4%) | 1,180 (9.3%) |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | – | – | – | 1,265 (10.0%) | 2,189 (17.3%) | 2,753 (21.6%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 3,997 (31.8%) | 3,839 (30.3%) | 3,823 (30.0%) | 3,389 (26.9%) | 2,791 (22.1%) | 2,456 (19.3%) |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | 537 (4.3%) | 495 (3.9%) | 246 (1.9%) | 455 (3.6%) | 360 (2.8%) | 158 (1.2%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 3,513 (11.2%) | 3,219 (10.2%) | 3,288 (5.0%) | 2,978 (9.5%) | 2,341 (7.4%) | 2,112 (3.2%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 351 (27.9%) | 593 (25.4%) | 856 (25.8%) | 351 (23.7%) | 593 (18.5%) | 856 (16.6%) |

| Golimumab 50 mg | 1,404 (2.8%) | 1,294 (4.7%) | 642 (6.7%) | 1,190 (2.8%) | 941 (4.7%) | 413 (6.7%) |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 1,443 (11.5%) | 1,465 (11.6%) | 1,760 (13.8%) | 1,223 (9.7%) | 1,065 (8.4%) | 1,131 (8.9%) |

| Infliximab | 554 (4.4%) | 511 (4.0%) | 253 (2.0%) | 470 (3.7%) | 371 (2.9%) | 163 (1.3%) |

| Infliximab bios | 361 (2.9%) | 610 (4.8%) | 880 (6.9%) | 361 (2.9%) | 610 (4.8%) | 880 (6.9%) |

| Apremilast 30 mg | 422 (3.4%) | 631 (5.0%) | 984 (7.7%) | 358 (2.8%) | 459 (3.6%) | 632 (5.0%) |

| Total | 12,582 (100.0%) | 12,657 (100.0%) | 12,733 (100.0%) | 12,582 (100.0%) | 12,657 (100.0%) | 12,733 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: PsA, psoriatic arthritis.

Table S3.

AS population without and with secukinumab over a 3-year horizon and respective change in market share for treatments

| Treatment | Scenario without secukinumab

|

Scenario with secukinumab

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients

|

Number of patients

|

|||||

| 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 1,328 (15.9%) | 2,124 (25.2%) | 2,636 (31.1%) |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 3,045 (36.4%) | 3,184 (37.8%) | 2,856 (33.7%) | 2,530 (30.2%) | 2,279 (27.1%) | 1,788 (21.1%) |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | 421 (5.0%) | 297 (3.5%) | 317 (3.7%) | 350 (4.2%) | 212 (2.5%) | 198 (2.3%) |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 2,363 (28.2%) | 2,564 (30.5%) | 2,358 (27.9%) | 1,963 (23.5%) | 1,835 (21.8%) | 1,477 (17.4%) |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 245 (2.9%) | 452 (5.4%) | 677 (8.0%) | 245 (2.9%) | 452 (5.4%) | 677 (8.0%) |

| Golimumab 50 mg | 1,266 (15.1%) | 892 (10.6%) | 952 (11.2%) | 1,052 (12.6%) | 639 (7.6%) | 596 (7.0%) |

| Infliximab | 759 (9.1%) | 535 (6.4%) | 571 (6.7%) | 631 (7.5%) | 383 (4.5%) | 358 (4.2%) |

| Infliximab bios | 266 (3.2%) | 491 (5.8%) | 735 (8.7%) | 266 (3.2%) | 491 (5.8%) | 735 (8.7%) |

| Total | 8,365 (100.0%) | 8,415 (100.0%) | 8,466 (100.0%) | 8,365 (100.0%) | 8,415 (100.0%) | 8,466 (100.0%) |

Note: Changing % market share of treatments over a 3-year horizon are shown in brackets.

Abbreviation: AS, ankylosing spondylitis.

Table S4.

Resource use and costs associated with PsO, PsA, and AS treatment

| Component | PsO

|

PsA

|

AS

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | % | Frequency per year | Unit cost | |

| Physician visit | 10 | 5.0 | €66.00 | 100 | 10.7 | €66.00 | 100 | 10.8 | €66.00 |

| Emergency room visit | – | – | – | 20 | 1.8 | €241.05 | 22 | 2 | €241.05 |

| Phototherapy (narrow band UVB) | 16 | 24.0 | €54.00 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| NSAIDsa | 45 | – | €1,446.31 | 52 | – | €1,446.31 | 22 | – | €1,446.31 |

| DMARDsa | 45 | – | €223.90 | 52 | – | €223.90 | 22 | – | €223.90 |

Notes: Cost data obtained from Italian national formulary;1 phototherapy-related data from De Compadri and Koleva;2 frequency data for PsO from NICE clinical guidance3 and for PsA and AS from Greenberg et al.4

For NSAIDs and DMARDs, cost has been estimated as weighted cost as the global model.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugl NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.

Table S5.

Annual rates of adverse events associated with PsO, PsA, and AS treatment

| Treatment option | PsO

|

PsA

|

AS

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serious infection | NMSC | Malignancies other than NMSC | Serious infection | NMSC | Serious infection | NMSC | |

| Secukinumab 150 mg | – | – | – | 1.4%6 | 2.1%6 | 0.9%7 | 0.9%7 |

| Secukinumab 300 mg | 1.4%8 | 0.4%8 | 0.3%8 | 2.8%6 | 0.0%6 | – | – |

| Adalimumab 40 mg | 5.2%a | 0.9%a | 0.6%a | 2.8%9 | 0.1%9 | 1.4%9 | 0.5%9 |

| Certolizumab 200 mg | – | – | – | 3.1%10 | 0.0%10 | 3.9%11 | 0.0%11 |

| Etanercept 50 mg | 5.1%a | 3.5%a | 0.0%a | 1.7%12 | 0.6%12 | 0.0%13 | 0.0%13 |

| Etanercept biosimilar | 5.1%b | 3.5%b | 0.0%b | 1.7%b | 0.6%b | 0.0%b | 0.0%b |

| Golimumab 50 mg | – | – | – | 1.4%14 | 0.0%14 | 0.4%15 | 0.0%15 |

| Ixekizumab | 0.02%a | 0.0%a | 0.0%a | – | – | – | – |

| Ustekinumab 45 mg | 0.0%a | 0.5%a | 0.6%a | 0.8%16 | 0.4%16 | – | – |

| Infliximab | 5.5%a | 0.4%a | 7.7%a | 1.9%17 | 1.9%17 | 2.1%18 | 0%18 |

| Infliximab bios | 5.5%b | 0.4%b | 7.7%b | 1.9%b | 1.9%b | 2.1%b | 0%b |

| Apremilast 30 mg | – | – | – | 2.6%19 | 1.3%19 | – | – |

Notes: Only serious adverse events due to malignancies and severe infections requiring hospitalization were included in the analysis. Severe infections included sepsis, tuberculosis, skin and soft tissue infections, bone and joint infections, pneumonia, and urinary tract infections.

Data obtained from product label.

Assumed same as corresponding branded drug. “–” Indicates a treatment (at a given dose strength) is not considered for the indication mentioned.

Abbreviations: AS, ankylosing spondylitis; NMSC, non-melanoma skin cancer; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis.