Abstract

Carbon nanotube (CNT) yarn and fiber-microelectrodes were developed for neurotransmitter detection using fast scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV). Fibers were made by suspending CNTs in acid/surfactant and extruding into acetone/polyethyleneimine (PEI) and compared to a CNT yarn. They were FSCV frequency independent for dopamine up to 100 Hz. With faster frequencies, up to 500 Hz, high currents are maintained, which allows a 2 ms sampling rate for FSCV, compared to 100 ms. CNT fibers have rough surfaces which trap dopamine and dopamine-o-quinone (DOQ), creating more reversible CVs. CNT yarns and fibers are beneficial for high sensitivity, rapid measurements of neurotransmitters.

Introduction:

Carbon nanotube based electrodes have been used in the electrochemical detection of biomolecules.1 The high conductivity of CNTs and fast electron-transfer kinetics facilitate detection of rapid fluctuations of neurotransmitters in vivo. Open CNTs have a higher density of edge-plane carbon on the ends, which is the catalytic site for neurotransmitter oxidation. Common sensor designs include coating CNTs on other materials,2 but recent studies have explored CNT yarn and fiber microelectrodes.3 CNT yarns are produced by textile method, where aligned CNTs are twisted into yarns. In contrast, CNT fibers are produced by wetspinning. CNT yarn4 and PEI-CNT microelectrodes5 both have lower limits of detection than CFMEs due to their larger electroactive surface areas. When used with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for rapid neurotransmitter detection, CNT yarn electrodes have currents for dopamine that are independent of the waveform application frequency, which could greatly improve the temporal resolution of neurochemical experiments. Treatments of these yarns, like laser etching and anti-static gun application, can also change the surface roughness which allows momentary trapping of the analyte.6–7

Here, we show frequency-independent properties of 3 types of electrodes, CNT yarns, PEI-CNT fibers and acid-spun CNT fibers. The acid-spun CNT fiber avoids polymer and surfactant impurities because CNTs are dissolved in chlorosulfonic acid and syringed into an acetone bath. Acid spun CNT fibers have high sensitivities towards dopamine, although they are larger in diameter than the CNT yarns and PEI-CNT fibers. The high temporal resolution allows measurements at higher frequencies (500 Hz) and scan rates (2,000 V/s), an improvement of 50-fold in temporal resolution. This new property could enable measurements of dopamine release at the millisecond timescale using FSCV, enabling rapid detection of dopamine during fast phasic firing.

Experimental:

A 1 – 2 cm length of commercially available CNT yarn (20 μm diameter, General Nano, Cincinnati, OH) was inserted into a polyimide coated fused-silica capillary and sealed with Loctite 5-minute epoxy (cured 24 hours). CNT yarn microelectrodes were polished at a 90° angle as a disk. Carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs) were made with 7 μm diameter T-650 carbon fibers (Cytec Technologies, Woodland Park, NJ).8 Polyethyleneimine (PEI) CNT fibers were formed as previously described.9–10 Briefly, a suspension of 0.35% HiPCO CNTs (Unidym, Sunnyvale, CA) in 1.2% sodium dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid (SDBS, Sigma) was syringed into a solution of 40% PEI (branched, MW = 50,000 – 100,000, MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA) in methanol, which was on a rotating stage. The CNT ribbons were then purified in methanol and dried in an oven for 1 hour at 180°C to remove impurities. Acid spun CNT fibers were made as previously described.11 1% HiPCO CNTs were dissolved into chlorosulfonic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Acid spun fibers were dissolved in chlorosulfonic acid (1 M) and extruded into acetone. They were washed with water and then dried in an oven for one hour at 150°C. All CNT fiber microelectrodes were made with epoxy insulation.3 CNT fibers were cut at 100 μm to make cylinder electrodes, which have more surface area.

Results and Discussion:

Surface Characterization:

CNT yarn, PEI-CNT fiber, acid-spun CNT fibers were compared. CNT yarns are dry spun from aligned CNTs and thus, they are relatively impurity free and have a large surface area. Polyethyleneimine (PEI) CNT fibers are wet spun from CNTs suspended in surfactant via sonication and aggregation. When pushed into a streaming solution of polymer, the CNTs collapse into ribbons, which are washed in methanol to remove excess polymer and form thin CNT fibers (~20 μm in diameter). However, some polymer remains, which could block sites for adsorption of biomolecules. More recently, wet-spinning with acids instead of polymers has been investigated. Chlorosulfonic acid can dissolve the CNTs and the oxide groups of the chlorosulfonic acid can separate CNT bundles and align them into fibers. Once extruded into water or acetone, which displaces the acid, the CNTs are then vertically aligned into CNT fibers. These acid-spun fibers have no polymer or surfactant impurities.

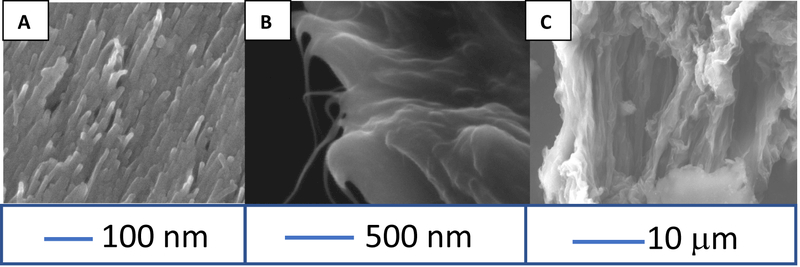

Fig. 1A shows SEM cross sections of each material. CNT yarns were made into polished disk electrodes and the ends are aligned CNTS (Fig. 1A). PEI-CNT fibers have diameters of 15–25 μm and are very rough, with CNTs evident at high magnification (Fig. 1B). The CNTs appear to be in thick bundles and some CNT bundles are seen protruding from the surface. Fig. 1C shows the side of an acid-spun CNT fiber, which has more pits, giving it a rough surface. The diameter of acid spun fibers is ~40 μm.

Figure 1: SEM Images of CNT Fibers and Yarn.

(A) Cross-section of a CNT yarn microelectrode. (B) SEM image of a PEI CNT fiber end. Thin whiskers of individual CNTs protrude from the bundles in the cross-section. (C). SEM of Acid Spun CNT fiber.

Electrochemical Characterization:

Electrochemical characteristics of the fibers and yarns are compared in Table 1. Acid -pun CNT microelectrodes (MEs) have large areas, large background currents, and low LODs for dopamine due to higher conductivity and larger diameter of the fiber. PEI-CNT and acid-spun CNT fiber MEs were cylinder electrodes with larger surface areas than CNTYMEs, which is reflected in the LOD. More controlled studies could be performed in the future to try to measure area to calculate sensitivity per unit area. CNTYMEs and acid-spun CNT fiber MEs had smaller ΔEp values than CFMEs and PEI-CNT fiber MEs, by about 100 mV (Table 1). These fibers are made of pure CNTs and thus have no impurities to hinder electron transfer. Peak separations are large for FSCV because the scan rate outruns electron transfer and possible iR drop as well. All of the CNT yarns/fiber microelectrodes have a greater reversibility for dopamine oxidation. A ratio of 1 would indicate all the dopamine that was oxidized was reduced to dopamine on the return scan. The acid-spun fibers are most reversible, which can be attributed to the trapping of dopamine inside some of the crevices in the electrodes. This trapping effect has been previously characterized at CNT yarn microelectrodes.12–13 While using dopamine as proof of principle, the concept may also applicable to other analytes such as other adsorption controlled neurotransmitters.

TABLE 1:

Electrochemical Data. including limit of detection, ΔEp and reversibility (cathodic/anodic peak). The limit of detection (LOD) was calculated using a S/N ratio of 3 from 100 nM dopamine.

| Fiber | n | LOD (nM) | ΔEp (mV) | ip,c/ip,a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFME | 4 | 24 ± 2 | 680 ± 5 | 0.63 ± 0.01 |

| CNTY | 5 | 10 ± 0.8 | 580 ± 3 | 0.77 ± 0.01 |

| PEI-CNT | 6 | 5 ± 1 | 670 ± 6 | 0.78 ± 0.01 |

| ACID-CNT | 6 | 3 ± 0.5 | 570 ± 7 | 0.95 ± 0.01 |

Frequency Independent Response:

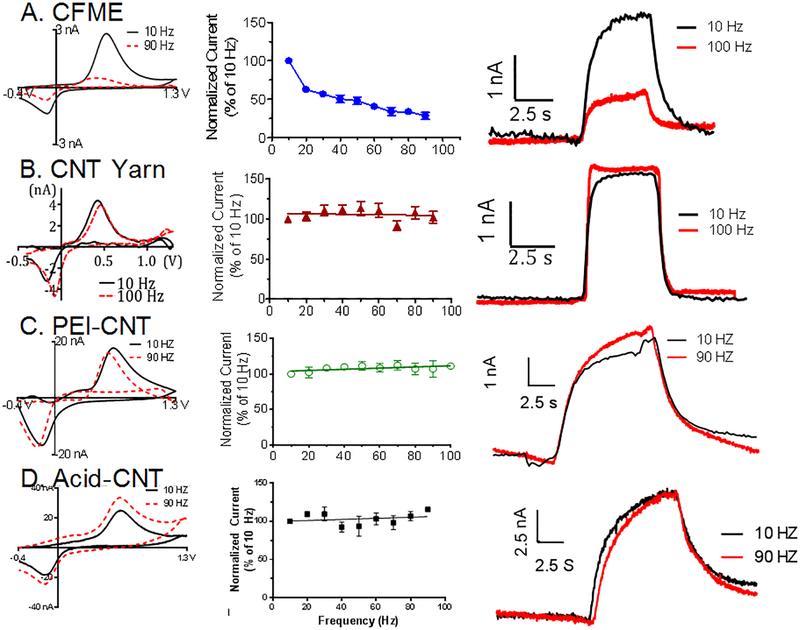

We recently discovered an interesting property of CNT yarn microelectrodes: their sensitivity for dopamine is independent of the waveform application frequency in FSCV. Traditionally, with CFMEs, the peak oxidative current of dopamine decreases as the frequency increases because there is less time for dopamine to adsorb during the holding potential at higher frequencies (Fig. 2A). Here, we observed PEI-CNT and acid-spun CNT fiber MEs have frequency-independent responses similar to CNT yarn MEs. Fig. 2B-D shows no drop in dopamine peak oxidative current upon increasing the frequency from 10 Hz to 90 Hz. This behavior occurs because the rough surface of the electrodes can create a thin-layer cell effect by trapping dopamine and its oxidation product dopamine-o-quinone (DOQ) at the surface of the electrode. Thus, the DOQ cannot diffuse far and the reactions are more reversible and frequency independent. Other carbon nanomaterial electrodes, such as those with short forests of aligned CNTs,14 CNTs grown on metal wires,15 or carbon nanospikes16 grown on metal microelectrodes are not frequency independent because their surface roughness is not great enough to trap DOQ long enough to increase reversibility. Importantly, the fast electrode time response is maintained even at the high frequencies.

Figure 2:

Frequency Response for 1 μM dopamine (400 V/s). Left: CVs at 10 Hz and 90 Hz repetition rates. Middle: Current with increasing FSCV frequency during repeated injections of dopamine. Right: Current vs time traces showing the temporal response. A. CFMEs (current drops with frequency). B. CNT Yarns are frequency independent (R2=.002). C. PEI-CNT fiber ME are frequency independent (R2 = .007). D. Acid-CNT fiber MEs are frequency independent (R2 = .074). n=4–6. The i vs t plots show that the rapid temporal response is maintained at high frequencies.

While 100 Hz is the limit with a 400V/s waveform (because the triangle waveform is about 10 ms), with higher scan rates, even higher frequencies can be achieved. At 2,000 V/s, the time for the triangle is about 2 ms; therefore, a 500 Hz frequency is possible. Figure 3A shows that at 2,000 V/s, the current at a CFME drops dramatically between 10 and 500 Hz. However, there is no decrease in peak oxidative current for CNTYMEs (Fig. 3B) or PEI-CNT fiber MEs (Fig. 3C) with frequency from 10 to 500 Hz. Acid-spun CNT fiber MEs could not be used with higher scan rates because their background currents were too large for standard FSCV amplifiers. At high scan rates, the CVs have larger ΔEp values because the CV is outrunning dopamine electron transfer. CNT Yarn MEs have a better peak shape, and the reduction peak for PEI-CNTs is likely lower than the scanned potentials. During salient events, bursts of action potentials occur only 20–100 milliseconds apart, and the current temporal resolution of CFMEs (100 msec) is not sufficient to measure these neurochemical changes. Therefore, the increased temporal resolution of neurotransmitter detection could enable a better understanding of complex brain neurochemistry elicited during firing patterns.

Figure 3:

High Temporal Resolution Measurements. Example CVs of 1 μM dopamine at 2000 V/s at 10 Hz and 500 Hz repetition rates at A. CFMEs, B. CNT yarn MEs and C. CNT-PEI fiber MEs.

Summary:

CNT fiber and yarn microelectrodes are useful for rapid detection of dopamine due to their frequency independent response. The phenomenon is hypothesized to occur due to the presence of micro-crevices on CNT microelectrodes that trap dopamine and DOQ, leading to reversible CVs because the analyte is trapped near the surface. These fast repetition frequencies may facilitate measurements of dopamine during individual pulses of burst firing. Future in vivo measurements are necessary with CNT yarn/fiber microelectrodes to understand their properties in tissue.

Acknowledgments:

Funding Source: NIH R21DA037584 and R01EB026497 and American University Faculty Research Support Grant.

References:

- 1.Wang J, Deo RP, Poulin P, Mangey M. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 125 14706–14707 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swamy BE; Venton BJ. Analyst, 132 (9), 876–884 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zestos AG, Nguyen MD, Poe BL, Jacobs CB, Venton BJ. Sensors and Actuators B-Chemical. 182, 652–658, (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs CB, Ivanov IN, Nguyen MD, Zestos AG, Venton BJ. Analytical chemistry, 86, 5721–5727 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zestos AG, Jacobs CB, Trikantzopoulos E, Ross AE, Venton BJ. Analytical chemistry, 86 8568–8575 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang C, Wang Y, Jacobs CB, Ivanov IN, Venton BJ. Analytical chemistry, 89 5605–5611 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang C, Trikantzopoulos E, Nguyen MD, Jacobs CB, Wang Y, Mahjouri-Samani M, Ivanov IN, Venton BJ. ACS sensors, 1 508–515 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huffman ML, Venton BJ. Analyst, 134, 18–24 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munoz E, Suh DS, Collins S, Selvidge M, Dalton AB, Kim BG, Razal JM, Ussery G, Rinzler AG, Martinez MT, Baughman RH.. Advanced Materials. 17 (8), 1064-+ (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vigolo B, Penicaud A, Coulon C, Sauder C, Pailler R, Journet C, Bernier P, Poulin P. Science. 290 (5495), 1331–1334, (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Behabtu N, Young CC, Tsentalovich DE, Kleinerman O, Wang X, Ma AW, Bengio EA, ter Waarbeek RF, de Jong JJ, Hoogerwerf RE. Science, 339, 182–186 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang C, Trikantzopoulos E, Jacobs CB, Venton BJ. Analytica chimica acta, 965, 1–8 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang C, Denno ME, Pyakurel P, Venton BJ.Analytica chimica acta, 887, 17–37 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao N, Venton BJ. Analytical chemistry, 84, 7816–7822 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang C, Jacobs CB, Nguyen MD, Ganesana M, Zestos AG, Ivanov IN, Puretzky AA, Rouleau CM, Geohegan DB, Venton BJ. Analytical chemistry, 88 645–652 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zestos AG, Yang C, Jacobs CB, Hensley D, Venton BJ. Analyst, 140 7283–729 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]