Abstract

Typically, the synthesis of radiometal-based radiopharmaceuticals is performed in buffered aqueous solutions. We found that the presence of organic solvents like ethanol increased the radiolabeling yields of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA (DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacatic acid). In the present study, the effect of organic cosolvents [ethanol (EtOH), isopropyl alcohol, and acetonitrile] on the radiolabeling yields of the macrocyclic chelator DOTA with several trivalent radiometals (gallium-68, scandium-44, and lutetium-177) was systematically investigated. Various binary water (H2O)/organic solvent mixtures allowed the radiolabeling of DOTA at a significantly lower temperature than 95 °C, which is relevant for the labeling of sensitive biological molecules. Simultaneously, much lower amounts of the chelators were required. This strategy may have a fundamental impact on the formulation of trivalent radiometal-based radiopharmaceuticals. The equilibrium properties and formation kinetics of [M(DOTA)]− (MIII= GaIII, CeIII, EuIII, YIII, and LuIII) complexes were investigated in H2O/EtOH mixtures (up to 70 vol % EtOH). The protonation constants of DOTA were determined by pH potentiometry in H2O/EtOH mixtures (0–70 vol % EtOH, 0.15 M NaCl, 25 °C). The log K1H and log K2H values associated with protonation of the ring N atoms decreased with an increase of the EtOH content. The formation rates of [M(DOTA)]− complexes increase with an increase of the pH and [EtOH]. Complexation occurs through rapid formation of the diprotonated [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates, which are in equilibrium with the kinetically active monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates. The ratecontrolling step is deprotonation (and rearrangement) of the monoprotonated intermediate, which occurs through and assisted reaction pathways. The rate constants are essentially independent of the EtOH concentration, but the M(HL)kH2O values increase from CeIII to LuIII. However, the logKM(HL) H protonation constants, analogous to the log KH2 value, decrease with increasing [EtOH], which increases the concentration of the monoprotonated M(HDOTA) intermediate and accelerates formation of the final complexes. The overall rates of complex formation calculated by the obtained rate constants at different EtOH concentrations show a trend similar to that of the complexation rates determined with the use of radioactive isotopes.

INTRODUCTION

Radiometal/Chelator Complexes.

Complexation of the radioactive metal ion *M by an adequate polydentate chelator L (also referred to as the chelator C) or its bifunctional version (BFC) covalently coupled to a biological targeting vector (TV) is an extremely important consideration in the design and construction of metal-based radiopharmaceuticals. For diagnostic and therapeutic applications in nuclear medicine, trivalent radiometals *MIII are typically chelated by macrocyclic polyamino polycarboxylic chelators, especially DOTA (H4DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid) and its derivatives, to form high-stability complexes. However, DOTA and its derivatives generally form complexes with M3+ ions exceedingly slowly at room temperature, limiting their applications for isotopes with short half-lives. On the other hand, once formed, the *MIII-L complexes, in particular the *MIII-DOTA complexes, guarantee high in vivo thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness; these properties have been systematically investigated for nonradioactive trivalent metal ions such as lanthanide(III) cations used in magnetic resonance or optical imaging.1

Slow-formation (i.e., radiolabeling) kinetics may become a critical issue for short-lived radionuclides like gallium-68 (t1/2 = 67.71 min). For this reason, detailed evaluation and optimization of experimental conditions were conducted to increase the radiolabeling efficiency. Gallium-68 complex formation can be accelerated by increasing the temperature.2,3 Elevated temperatures (e.g., 90–95 °C) are commonly used to label DOTA-conjugated somatostatin analogues or DOTA affibodies/antibodies with gallium-68, yttrium-90, indium-111, or lutetium-177, providing nearly 100% radiolabeling efficiency. With gallium-68, nearly quantitative radiolabeling (ca. 90–95%) occurs within 10 min under these conditions. Depending on the biological TV, microwave-assisted synthesis can alternatively be used to facilitate *MIII-DOTA-TV complex formation.4

Considering slow complex formation, high yields require sufficient excess of the chelating agent. In contrast, high apparent molar radioactivity of the radiopharmaceutical is preferred depending on the type of diagnostic or therapeutic application.5 For example, imaging and therapy of tumor cells overexpressing G-protein-coupled transmembrane receptors require high apparent molar activities because of the limited number and affinity of receptors on the target site. The apparent molar radioactivity is the ratio of the product radioactivity per mole chelator by taking into account the amounts of labeled and nonradiolabeled compounds. The molar amount of the radiometal cations is generally ultralow, representing, for example, 5.860 × 1012 atoms (9.731 × 10−12 mol) for 1 GBq of gallium-68 and 8.285 × 1014 atoms (1.376 × 10−9 mol) for 1 GBq of lutetium-177. In contrast, nonradioactive metal impurities (such as FeII/FeIII ions present in the radiometal stock solution and/or the chemicals and glassware used), although low in concentration in the sense of “conventional” chemistry, can efficiently compete with the radiometal for the chelators. Because those impurities are usually not avoidable or reducible, larger amounts of the “chelator” component are required, which, in turn, affects the apparent molar radioactivity of the final radiopharmaceutical.5

Formation of Metal Complexes in Water (H2O) and Binary H2O/Organic Solvent Mixtures.

The synthesis of metal-based radiopharmaceuticals is generally performed in an aqueous medium, where the MIII ions exist as aqua complexes. Because of its molecular properties (small size, inherently polar, and polarizable), H2O is an excellent, versatile solvent. It can act as a hydrogen-bond acceptor as well as a donor, allowing formation of a variety of structures that can easily adjust to changes in conditions.6 In aqueous media, a well-defined number of H2O molecules directly surround the metal ion and are bound in the inner (or first) coordination sphere of the MIII ion to form the hydrated [M(OH2)n]3+ aqua complex, where n is the hydration (or coordination) number. A second shell of less ordered H2O molecules surrounds the first hydration sphere, forming a second (or outer) hydration sphere. The ordering of H2O molecules continuously decreases from the first hydration sphere to the bulk solvent.7,8

The complex formation reaction of MIII ions is generally rapid. The mechanisms of complex formation reactions are usually different for smaller, mono- or bidentate and larger multidenate chelators. The formation rate with smaller chelators is controlled by the H2O loss from the outer-sphere complex formed between the hydrated metal ion and the chelator. The formation rate of complexes with multidentate chelators is often determined by formation of the first chelate ring. The formation of macrocyclic MIII complexes is generally rather slow because of the highly preorganized nature of these chelators as well as the slow reorganization of the metal−donor bonds in the intermediates, which may play a significant role in formation of the fully encapsulated complex.9 The complexes of MIII ions with DOTA and its derivatives are known to form very slowly in the range of pH 4–6, which is unfavorable for the complexation of short-lived radioisotopes. As was recently reported, the reaction of gallium-68 with DOTA-TOC [edotreotide; DOTA(0)-Phe(1)-Tyr(3))octreotide] in an ethanol (EtOH)/H2O solvent mixture occurs more rapidly than that in pure H2O, making radiolabeling possible at lower temperatures.10

In an early publication, a mechanism for the formation of DOTA complexes with lanthanide(III) (LnIII) ions through a long-lived intermediate [LnH2(DOTA)]+ in which the metal ion interacts only with the deprotonated carboxylate arms of the macrocyclic chelator was suggested.11 A similar diprotonated [Gd(H2HP-DO3A)]+ intermediate has been evidenced in the Gd3+-HP-DO3A reaction system.12 The formation of protonated intermediates may take place in the reaction of several divalent metal ions with the DOTA ligand.13 The diprotonated [LnH2(DOTA)]+ intermediate is formed in a fast preequilibrium, and the rate-determining step of complex formation is concerted deprotonation of the N-donor atoms and penetration of the LnIII ion into the cavity.14,15 It is worth noting that the LnIII ions involved in this slow formation reaction are extremely labile; i.e., the rate constants characterizing the H2O exchange rates of aqueous LnIII ions (109 s−1) are among the fastest known.16,17

The solvation of metal ions and chelators in mixed H2O/organic media is more complicated than the hydration in aqueous media because the ratio of H2O/organic molecules in the inner-sphere [M(H2O)xSy] depends on both the H2O/organic solvent ratio and the binding energy difference between the MIII–H2O and MIII–organic solvent interactions. In addition, steric factors might also be important.7,8 The H2O molecules are strongly bound to the metal ions and may remain in the inner sphere even at high organic solvent/H2O ratios; therefore, interpretation of the kinetic effect of mixed solvent systems is by no means straightforward.18

The presence of large amounts of organic solvent will also affect intra- and intermolecular interactions. It has been demonstrated that organic solvents such as isopropyl alcohol (iPrOH) can disrupt the hydrogen bonds between H2O molecules, thereby acting as a structure breaker.19,20 Furthermore, the conformation of peptide chains in DOTA–peptide or protein conjugates may also be influenced by solute–H2O interactions, in particular where −NH2 or −COOH functionalities are concerned.21

We recently observed that the presence of EtOH in mixtures utilized to purify 68Ge/68Ga-generator eluates substantially increased the radiolabeling efficacies for [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC derivatives compared to pure aqueous solutions.10 Considering the favorable effect of EtOH on the formation reaction, the aim of this work was to systematically investigate the effect of nonaqueous solvents on radiometal–chelator complex formations. We included the trivalent radiometals gallium-68, scandium-44, and lutetium-177 and screened mixtures of H2O and organic solvents such as EtOH, iPrOH, and acetonitrile (MeCN). We studied the rate of complex formation with DOTA by varying the nonaqueous solvent/H2O ratio, amount of the chelator, temperature, and reaction time.

In order to understand the physicochemical background behind the rate-increasing effect of the organic solvents, we carried out systematic kinetic studies on the formation of [M(DOTA)]− (M = GaIII, CeIII, EuIII, YIII, and LuIII) complexes in H2O/EtOH mixtures (up to 70 vol % EtOH). We could rationalize the effect of EtOH on the reaction rates by determining the protonation constants of the DOTA chelator and [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates in H2O/EtOH mixtures. The solvation of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII in mixed H2O/EtOH solutions was also tested by gallium-71, scandium-45, and yttrium-89 NMR via measurement of the T1 relaxation times of the nuclei.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Radiolabeling of DOTA and DOTA Conjugates with the Trivalent Metallic Radionuclides Gallium-68, Scandium-44, and Lutetium-177.

DOTA as a single chelator was used as the model compound because of its prevalent clinical role as a chelator in therapeutic (e.g., [90Y]Y/[177Lu]Lu-DOTA-TOC/DOTA-TATE) or diagnostic (e.g., Gd-DOTA; [68Ga]Ga-DOTA-TOC) agents. To determine the effect of additional organic solvents in the reaction mixture, the radiolabeling conditions were selected so that the radiochemical yield for gallium-68 labeling would be low (~50%) at relatively low temperature (70 °C) in a pure aqueous solution. These conditions were also adopted for scandium-44 and lutetium-177. This radiolabeling profile was taken as a reference for pure aqueous systems at 10 nmol of DOTA, and any influence of organic solvents on the radiolabeling yields was directly determined by a comparison to the yield obtained under these conditions.

[68Ga]Ga-DOTA.

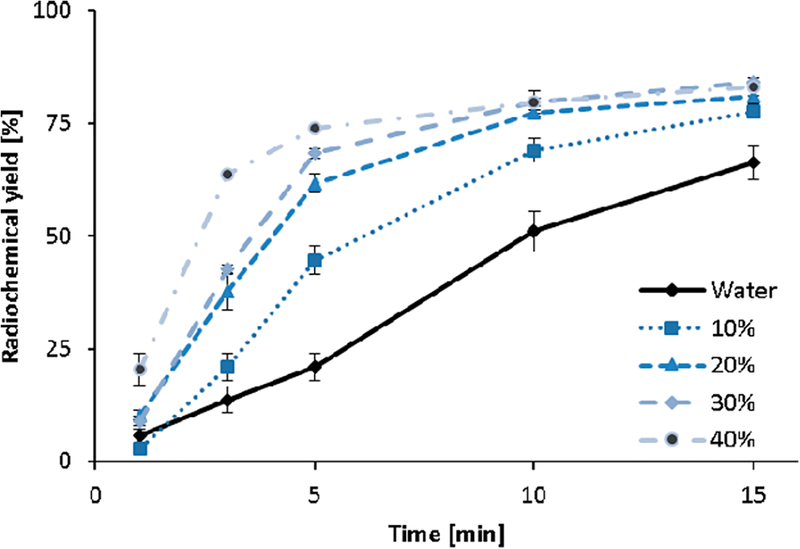

Table 1 shows the radiochemical yields of radiolabeling DOTA with gallium-68 in H2O or H2O/organic solvent mixtures (30 vol % EtOH, MeCN, or iPrOH) in percentage as well as normalized values relative to the radiochemical yield of radiolabeling in a pure aqueous solution. For all investigated nonorganic solvents, a small but highly reproducible increase of the radiolabeling yields by a factor of 1.3 was observable after 15 min of reaction time. This relative increase (nonaqueous system compared to a pure aqueous system) is even more distinctive at shorter reaction times. For example, after 5 min of reaction time, the relative increase values are 3.3 (EtOH), 3.4 (MeCN), and 3.6 (iPrOH). The most obvious enhancement is observed within 3 min of reaction time using MeCN [3.7] and iPrOH [4.5] and at 5 min for EtOH [3.3]. After 10 min, a plateau is achieved, and no significant further increase in radiolabeling can be observed for the nonaqueous systems, while complex formation continues to progress in the aqueous system. Figure 1 illustrates the impact of different amounts of EtOH (0–40 vol %) on the [68Ga]Ga-DOTA complex formation at 70 °C. A 2.1-fold increase in the complex formation yields is observed in the presence of as low as 10 vol % EtOH within 5 min of reaction time. A further increase in the EtOH content up to 40 vol % resulted in a 3.5-fold increase. After a 15 min reaction time, the relative increase observed for different amounts of EtOH approximates the same limit, around 80%. The highest impact of the nonaqueous solvent can be observed at 40 vol % solvent content and short reaction times (<5 min).

Table 1.

[68Ga]Ga-DOTA Radiolabeling Yields in Percentage (%) and Normalized (in Square Brackets) Values Relative to the Radiochemical Yields Obtained at 70 °C in a Pure Aqueous Solution and in Mixtures with Various Organic Solvents (30 vol%) with 10 nmol of DOTA Depending on the Reaction Timea

| time (min) | radiolabeling yields (%) and factors of increase (in square brackets) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2O | EtOH | MeCN | iPrOH | |

| 1 | 5.7 ± 1.1 [1] | 9.0 ± 0.7 [1.6] | 6.7 ± 0.4 [1.2] | 12.0 ± 1.3 [2.1] |

| 3 | 13.7 ± 2.2 [1] | 42.7 ± 3.8 [3.1] | 51.3 ± 2.2 [3.7] | 63.3 ± 2.4 [4.6] |

| 5 | 21.0 ± 2.0 [1] | 68.3 ± 2.2 [3.3] | 71.0 ± 1.3 [3.4] | 74.7 ± 0.9 [3.6] |

| 10 | 51.0 ± 3.3 [1] | 79.7 ± 0.4 [1.6] | 81.3 ± 0.4 [1.6] | 82.3 ± 0.4 [1.6] |

| 15 | 66.3 ± 2.9 [1] | 84.0 ± 0.7 [1.3] | 83.7 ± 0.9 [1.3] | 86.7 ± 0.4 [1.3] |

The dramatic increase observed for a short reaction time, such as 3 min, is indicated in boldface.

Figure 1.

Complex formation kinetics of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA in the presence of 0−40 vol % EtOH (10 nmol DOTA, 70 °C, n = 3).

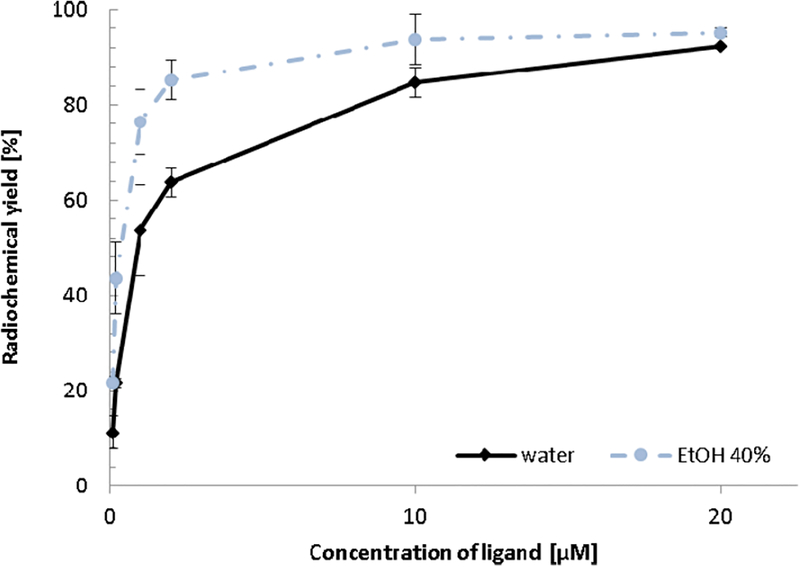

The dramatic increase in the reaction yields in EtOH-containing solvent mixtures suggests that gallium-68 labeling of DOTA is more effective in H2O/EtOH mixtures compared to the currently used standard aqueous system (“standard” here refers to pure aqueous solutions and reaction temperatures of 95 °C). Because the standard synthesis of 68Ga-DOTA-conjugated radiopharmaceuticals is typically performed at 95 °C, we decided to investigate whether the presence of an organic solvent would improve the rate of complex formation at 95 °C compared to reactions run at 70 °C. Because DOTA conjugated to small TVs can usually be labeled with gallium-68 under those temperatures (95 °C) at sufficiently high concentrations of the chelator conjugate to afford over 90% yields, our assumption was that it might be possible to achieve high radiolabeling yields at much lower concentrations of the chelator if mixed solvent systems were used. The dependence of the radiochemical yield of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA on the concentration of DOTA in the presence of 40 vol % EtOH after 5 min of radiolabeling is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Complex formation yields of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA depending on the DOTA concentration for the pure aqueous system and in a solution containing 40 vol % EtOH ([DOTA] = 0.1−20 μM, 95 °C, 5 min, n = 3).

When larger amounts such as 63.3 nmol (i.e., 20 μM concentration) of DOTA were used, the radiochemical yields were similar for the pure aqueous H2O (92.2%) and the H2O/EtOH (95.2%) system, and in this case, no significant gain in the radiochemical yield was found in the presence of EtOH. However, the radiochemical yields drop faster in the pure aqueous system than in the H2O/EtOH mixture with decreasing DOTA concentrations. For example, while labeling yields in pure aqueous systems drop from 92.2% to 84.8% to 63.7% when the DOTA concentration decreases from 20 to 10 to 2 μm, the corresponding yields in 40 vol % EtOH systems are 95.2%, 93.7°%, and 85.2%, respectively. Figure 2 clearly demonstrates that, in the presence of 40 vol % EtOH, the complex formation yields of [68Ga]Ga-DOTA are higher at 10 μM DOTA than that obtained in a pure aqueous solution containing twice as much DOTA (20 μM).

[44Sc]Sc-DOTA.

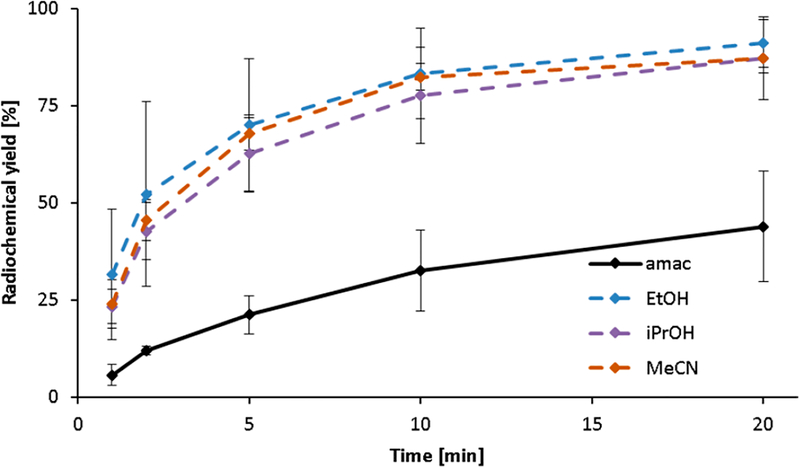

DOTA was labeled with scandium-44 as described for [68Ga]Ga-DOTA in solvent systems containing different amounts (0–40 vol %) of EtOH, iPrOH, or MeCN. Figure 3 shows the results obtained in the presence of 30 vol % of these solvents in comparison to the conventional radio-labeling procedure performed in pure ammonium acetate (amac) buffer (0.25 M, pH 4.0). Analogous to the radiolabeling experiments with gallium-68, significantly improved scandium-44 radiolabeling yields were observed in the presence of an organic solvent. Under these conditions, yields of up to 91.0% (EtOH; 20 min) were achieved, which represents a 2-fold increase compared to the yields obtained in the pure aqueous buffer system (43.9%, 20 min).

Figure 3.

Complex formation kinetics of [44Sc]Sc-DOTA in the presence of 30 vol % nonaqueous solvents (10 nmol DOTA, 70 °C, n = 3, 0.25 M amac buffer, pH 4).

Table 2 shows the radiolabeling yields of [44Sc]Sc-DOTA in solutions containing 10–40 vol % EtOH and iPrOH relative to the yield obtained in a pure aqueous buffer solution.

Table 2.

Increase of 44Sc-Radiolabeling Yields Depending on the Amount of Organic Solvent (0−40 vol% EtOH and iPrOH) and the Reaction Time Given as Normalized Values Relative to the Yield Obtained in a Pure Aqueous Buffer Solution

| time (min) | EtOH (vol %) | iPrOH (vol %) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | |

| 1 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 4.1 | 5.2 |

| 3 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| 5 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 3.3 | 3.2 | 1.4 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| 10 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| 20 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

At short reaction times (<5 min) and in mixtures containing 30% or more organic solvent, the effect of EtOH slightly exceeds that of iPrOH. For example, at 3 min reaction time, the use of 30 and 40 vol % EtOH afforded 4.4- and 4.1-fold increases, respectively, while the corresponding increase was 3.6- and 4.0-fold with 30 and 40 vol % iPrOH, respectively. For lower solvent concentrations (<30 vol %), the order was reversed. For longer reaction times (>5 min), the impact of both solvents on radiolabeling was more or less the same for each concentration and showed only a modest improvement over the shorter reaction times.

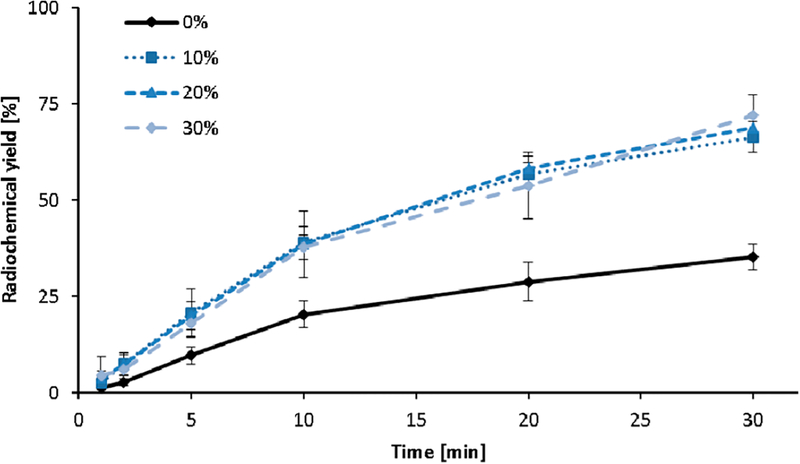

[177Lu]Lu-DOTA.

The β-emitting radionuclide lutetium-177 (t1/2 = 6.73 days) is frequently used in peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Being a lanthanide, Lu3+ forms stable complexes with DOTA and its derivatives, and these chelators are frequently used in the construction of lutetium-177 radiopharmaceuticals. In the present work, DOTA was radiolabeled with lutetium-177 in H2O/EtOH mixtures (0–40 vol %) of EtOH after determination of the baseline conditions (70 °C, chelator–metal ratio 10:1, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 8, 30 min).

Figure 4 shows the relative increase of the radiolabeling yields of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA with increasing percentage of EtOH (10−30 vol %) present in the solvent mixture. At short reaction times of less than or equal to 5 min, the effect of EtOH on the yields somewhat exceeds those observed at longer reaction times above 5 min. For example, at 2 min the relative increase achieved by using 30 vol % EtOH is 2.1, while at 10 min, it is 1.8.

Figure 4.

Complex formation kinetics of [177Lu]Lu-DOTA in the presence of 0−30 vol % EtOH (10 nmol DOTA, 70 °C, n = 3, 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer, pH 8).

Formation of MIII Complexes with DOTA Chelator in H2O/EtOH Mixtures.

To understand and explore the impact of organic solvents on the thermodynamic and kinetic properties of the MIII-DOTA systems, systematic studies on the protonation equilibria of DOTA and the formation rates of [M(DOTA)]− (MIII = GaIII, CeIII, EuIII, YIII, and LuIII) complexes in H2O/EtOH mixtures (10, 40, and 70 vol % EtOH) were carried out. We propose a reaction mechanism for the formation of [M(DOTA)]− complexes in the H2O/EtOH solvent system, which is also supported by multinuclear NMR studies. The solvation of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII ions in mixed H2O/EtOH solutions was also tested by 71Ga, 45Sc, and 89Y NMR by measuring the T1 relaxation time of the nuclei.

Protonation Equilibria of DOTA in H2O/EtOH Mixtures.

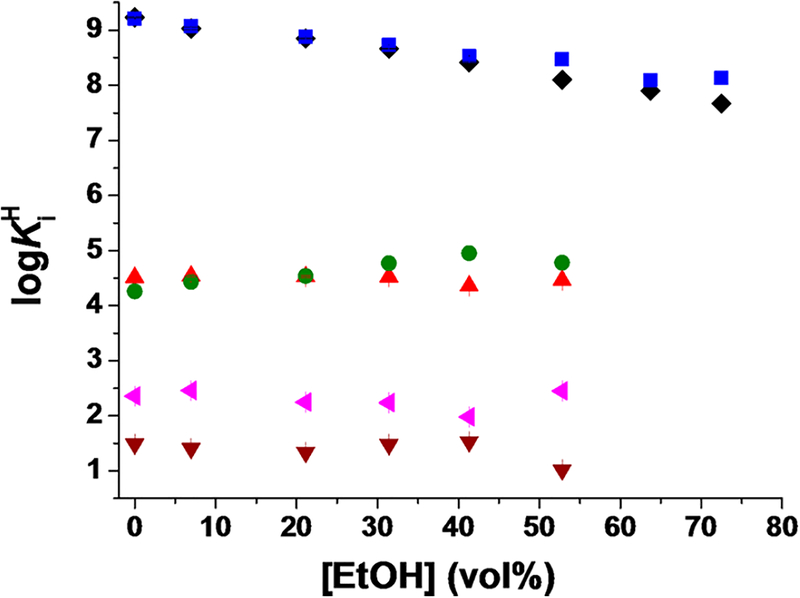

The protonation scheme of DOTA in pure aqueous solutions is well-known.22 In the present work, the protonation constants of DOTA, defined by eq 1, have been determined by pH potentiometry in H2O/EtOH mixtures. The log Ki H values are shown in Figure 5 (standard deviations are shown with error bars) and Table S2.

| (1) |

where i = 1, 2,…, 6. The data presented in Figure 5 and Table S2 indicate that the log K1 H and log K2 H values associated with the protonation of two opposite macrocyclic ring N atoms22 decrease with the increase of the EtOH content. This observation is in agreement with literature data reporting that the protonation constants of N atoms in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) chelator decrease with an increase of the MeOH content of up to around 80 m/m % MeOH. Interestingly, above 80–90 m/m % MeOH, the protonation constants of the N atoms start to rise.23

Figure 5.

Dependence of the protonation constants (log KiH) of DOTA on the EtOH content in H2O/EtOH mixtures at 25 °C in 0.15 M NaCl ([DOTA] = 2.00 mM; log KlH, black ◆; log K2H, blue ■; log K3H, red ▲; log K4H, green ●; log K5H, pink ◀; log K6H, brown ▼)

The basicity of the ring N atoms of DOTA might be influenced by four effects: (i) the electrostatic repulsion between the protonated N atoms, which reduces the basicity of the remaining macrocylic N atoms; (ii) hydrogen-bonding interaction between the protonated N atom and the negatively charged carboxylate group, which increases the basicity of the N atom, and any potential barrier for this hydrogen-bond formation would decrease the basicity; (iii) the formation of a relatively stable [Na(DOTA)]3− complex (log KNaL = 4.38),24 which results in a drop in the basicity; (iv) EtOH has a significantly lower proton dissociation constant than H2O, which also decreases the basicity of the macrocyclic N atoms. The sum of all of these effects will then lead to the gradual decrease of the log K1 and log K2 values of DOTA with increasing concentration of EtOH. The log K3 H, log K4 H, logK5 H, and log K6 H values are related to protonation of the carboxylate groups. These values are essentially constant (Figure 5), with the exception of log K4 H, which slightly increases with increasing EtOH concentration. A similar behavior was reported for the EDTA carboxylates, whose protonation constants monotonously increase with increasing concentration of methanol (MeOH).23

Formation of [M(DOTA)] Complexes in H2O/EtOH Mixtures (MIII = GaIII, CeIII, EuIII, YIII, and LuIII).

It is well-known that the complexes of the macrocyclic, rigid DOTA are formed slowly with trivalent metal ions.14,15 The slow formation of complexes may cause difficulties when the complex is used as a radiopharmaceutical. The formation mechanism of DOTA complexes is fairly well-known. The slow complexation rate of DOTA is largely due to its rigid structure and can be described by the following mechanism. The metal ion has to enter the coordination cage formed by the four ring N atoms and the four O atoms of the acetates attached to the N atoms. The formation of the fully formed, in-cage complex is hindered by the protonation of two macrocyclic ring N atoms below pH 7, but the four acetates will coordinate to the metal ion to form a diprotonated intermediate, [Ln(H2DOTA)]+, in which the LnIII ion is situated outside the coordination cage. In addition to the four acetates, four or five H2O molecules also coordinate to the metal ion.14,15,25,26 The complex formation is completed by removal of the two protons from the coordination cage, which is followed by rearrangement of the intermediate to the final [Ln(DOTA)]− complex. The rate-determining step is probably the loss of the last proton from the [Ln(HDOTA)] intermediate.15

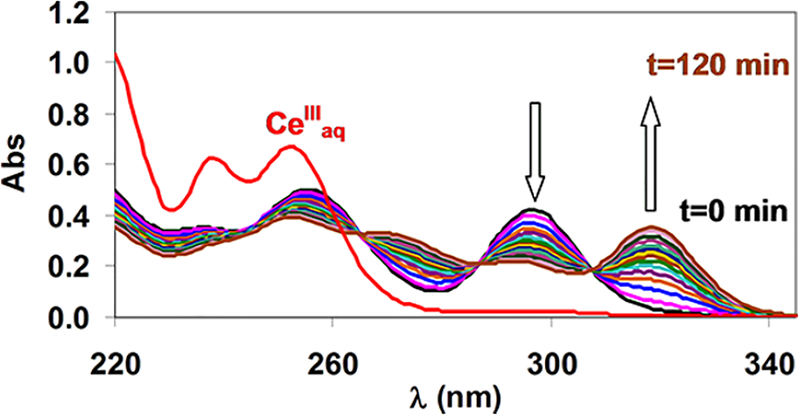

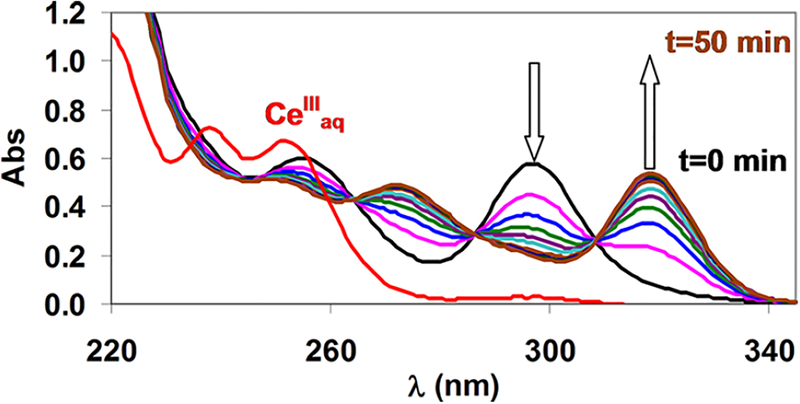

In the present work, we studied the formation kinetics of [M(DOTA)]− complexes (MIII = GaIII, CeIII, EuIII, YIII, and LuIII) in H2O/EtOH mixtures containing 10, 40, and 70 vol % EtOH. The formation of [Ce(DOTA)]− and [Eu(DOTA)]− was followed spectrophotometrically by observing the absorption bands at 320 and 250 nm, respectively. The formation of [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu-(DOTA)]− was followed by monitoring the release of H+ from DOTA (indicator method).27 The composition of the diprotonated [Ce(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate in aqueous solution was proven previously by pH-potentiometric titration14 and also by other methods.15,25,26 The detection of this intermediate as well as the monitoring of the complex formation in H2O/EtOH mixtures was performed by spectrophotometry. CeCl3 and H4DOTA were reacted in equimolar quantities in 10 and 70 vol % EtOH, and the UV spectra were recorded as a function of time (over 120 and 50 min), as shown in Figures 6 and 7.

Figure 6.

Absorption spectra of the Ce3+-DOTA system ([Ce3+] = [DOTA] = 1.0 mM, [N-methylpiperazine] = 0.01 M, 10 vol % EtOH, pH 4.46, l = 0.874 cm, 0.15 M NaCl, 25 °C).

Figure 7.

Absorption spectra of the Ce3+-DOTA system ([Ce3+] = [DOTA] = 0.1 mM, 70 vol % EtOH, [N-methylpiperazine] = 0.01 M pH 4.51, l = 10 cm, 0.15 M NaCl, 25 °C).

The intensity of the band at 296 nm decreases, while that at 320 nm increases over time. These spectra are essentially identical with those obtained in aqueous solutions. These experiences clearly demonstrate that the structure of the diprotonated intermediate [Ce(H2DOTA)]+ is the same in H2O and 10 and 70 vol % EtOH solutions. Similar phenomena were observed during the spectroscopic studies of the formation of [Eu(DOTA)]−. The formation of [Y(DOTA)]−, [Lu(DOTA)]−, and [Ga(DOTA)]− was also followed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Figures S3–S5). The appearance of isosbestic points in the 1H NMR spectra of these systems clearly indicates the formation of a [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate, which is slowly transformed to the final [M(DOTA)]−. It should be noted that in the pH range of these studies (pH 2.0) diprotonated [Ga(H2DOTA)]+ complexes are present in equilibrium (two carboxylate groups are protonated in the [Ga(H2DOTA)]+ complexes).28

The kinetic studies on the formation of [Ce(DOTA)]− and [Eu(DOTA)]− were also performed in the presence of excess CeIII and EuIII under pseudo-first-order conditions. The concentrations of CeIII and EuIII were 5−40 times higher than those of DOTA ([DOTA] = 2.0 × 10−4 M), and under these conditions, the rate of complex formation can be expressed by eq 2.

| (2) |

where [ML]t is the concentration of the [M(DOTA)]− complex formed, [L]t is the total concentration of the DOTA chelator at a given time point, and kobs is a pseudo-first-order rate constant. The formation reactions were studied at different pH values by varying the metal ion concentrations. The kobs versus [MIII] curves (Figures S6–S11) are saturation curves indicating the formation of [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates. The thermodynamic stability of these intermediates is characterized by a stability constant defined by eq 3.

| (3) |

where [M(H2L)] is the concentration of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate and [H2L] is the concentration of the H2DOTA2− chelator. The stability constants of these intermediates are relatively high, so the kobs values obtained even at lower metal-ion excess are close to the saturation value. The rate-determining step of the reaction is the deprotonation and rearrangement of the intermediate, followed by the entrance of the MIII ion into the macrocyclic cage:

| (4) |

where [M(H2L)] is the concentration of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate and kf is the rate constant characterizing the deprotonation and rearrangement of the intermediate to the [M(DOTA)]− complex. Taking into account the protonation constants of DOTA (Table S2), the stability constant of [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate (eq 3), and eq 4, the pseudo-first-order rate constant can be expressed by eq 5.

| (5) |

where The stability constant of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates and the kf rate constants have been calculated from the fitting of the pseudo-first-order rate constants obtained at various pH and [MIII] values to eq 5. The obtained stability constants are shown in Table S3. The kf rate constants for the formation of [Ce(DOTA)]− and [Eu-(DOTA)]− complexes are presented in Figures S12 and S13 as a function of [OH−].

The formation rates of [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu(DOTA)]− have also been studied under pseudo-first-order conditions that were ensured by the presence of a large excess of DOTA ([GaIII] = [YIII] = [LuIII] = 2.0 × 10−4 M; [DOTA]t = (1.0−6.0) × 10−3 M). In these cases, the rate of formation reactions can be expressed by eq 6.

| (6) |

where [ML] is the concentration of the [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu(DOTA)]− complexes formed, [MIII]t is the total concentration of species containing GaIII, YIII, and LuIII ions, and kobs is a pseudo-first-order rate constant. The formation reaction of [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu(DOTA)]− was investigated by varying the concentrations of DOTA at different pH values. As expected, the kobs versus [DOTA]t curves (Figures S14–S22) are saturation curves indicating the formation of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates.15 The rate-determining step of the reactions is the deprotonation and rearrangement of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates followed by the entrance of the metal ion into the cavity of the DOTA chelator:

| (7) |

where [M(H2L)]t is the concentration of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate and kf is the rate constant characterizing the deprotonation and rearrangement of the intermediate to the final [M(DOTA)]− complex. The concentration of the noncomplexed chelator can be expressed by eq 8 using the protonation constants of the DOTA chelator (Table S2).

| (8) |

where . Taking into account the hydrolysis of the MIII ion, the total metal-ion concentration can be expressed by eq 9:

| (9) |

Under the experimental conditions (pH 2.5−7.0), hydrolysis of the Ga3+ ion may occur, resulting in the formation of [M(OH)]2+, [M(OH)2]+, and M(OH)3 species; i.e., OH− ions may compete with the DOTA for the GaIII ions. However, in the cases of YIII and LuIII, hydrolysis can be neglected at pH < 7.29 Taking into account the protonation constants of DOTA (Table S2 and eq 8), the stability constant of the [M-(H2DOTA)]+ intermediate (eq 3), the total concentration of the MIII ion (eq 9), and eq 7, the pseudo-first-order rate constant can be expressed by eq 10.

| (10) |

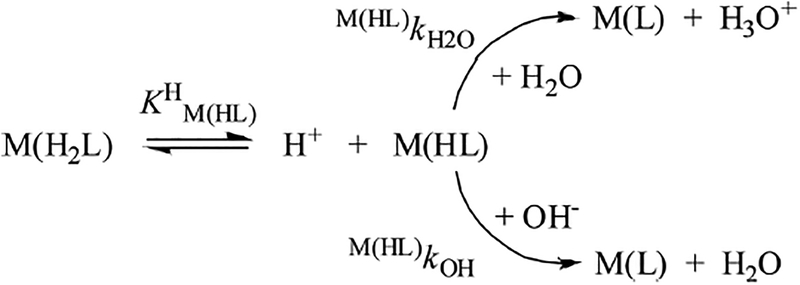

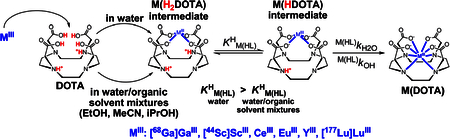

where [L]t is is the total concentration of the DOTA chelator and .29 The pseudo-first-order rate constants determined at various pH and [DOTA] values (Figures S14–S22) were fitted to eq 10, and the stability constant of the [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates () and the kf rate constants were calculated (for the YIII and LuIII complexes, αOH = 0). The stability constants of the [Ga(H2DOTA)]+, [Y(H2DOTA)]+, and [Lu(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates () are presented in Table S3. The calculated kf rate constants obtained for formation of the [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu-(DOTA)]− complexes are shown in Figures S23–S25 as a function of [OH−]. The kinetic data that we obtained indicate that the kf values increase with an increase of [OH−] and [EtOH]. According to the reaction mechanism proposed for the formation of [M(DOTA)]− complexes, the di- and monoprotonated intermediates exist in equilibrium. The dependence of the kf values on [OH−] can be interpreted by formation of the kinetically active monoprotonated [M-(HDOTA)] intermediates through dissociation of the diprotonated [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates in an equilibrium characterized with the KM(HL)H protonation constant (eq 11). The rate-controlling step of complex formation involves the H2O- or OH− -assisted deprotonation and rearrangement of the monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates to the final [M(DOTA)] complex (Scheme 1).15

| (11) |

Scheme 1.

Formation Mechanism of M(DOTA) Complexes

Considering the significantly lower polarity (lower relative permittivity) and higher pKa of the EtOH molecule relative to H2O (the concentration of the EtO− anion is extremely low in the range pH 2.5−7.0), it can be assumed that deprotonation of the monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates takes place via H2O (as a weak Bronsted base) and OH−-assisted pathways even in the presence of large amounts of EtOH. According to the proposed reaction mechanism, the formation rate of the [M(DOTA)]− complexes can be given by eq 12.

| (12) |

By considering the total concentration of the intermediates ([M(H2L)]t = [M(HL)] + [M(H2L)]), the definition of the KM(HL) protonation constant (Scheme 1), the concentration of H2O molecules, and the ionic product of H2O (Kw) in EtOH solutions (Table S1), the kf rate constant can be expressed by eq 13.

| (13) |

This equation was used for fitting of the kf values to determine the and rate constants and the protonation constants that characterize the formation of [M(DOTA)]− complexes in H2O and 10, 40, and 70 vol % EtOH solutions. The and rate constants and the protonation constants obtained from the fitting are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Rate (k) and Equilibrium Constants (K) Characterize the Formation of [Ga(DOTA)]−, [Ce(DOTA)]−, [Eu(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu(DOTA)]− Complexes in H2O and 10, 40, and 70 vol % EtOH Solutions (0.15 M NaCl, 25°C)

| H2O | 10 vol % EtOH | 40 vol % EtOH | 70 vol % EtOH | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [H2O] (mol L−1) | 55.6 | 50.1 | 33.9 | 16.9 | |

| Kw | 1.4 × 10−14 | 1.1 × 10−14 | 5.4 × 10−15 | 2.3 × 10−15 | |

| [Ce(DOTA)] | M(HL)kH2O (M−1 s−1) | 0.34a | 0.42 ± 0.03 | 0.43 ± 0.04 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| M(HL)kOH (M−1 s−1) | (1.9 × 107)15 | (1.1 ± 0.5) × 107 | (1.5 ± 0.3) × 107 | (9 ± 3) × 106 | |

| log KM(HL)H | 8.64a | 8.9(1) | 8.5(2) | 7.9(3) | |

| [Eu(DOTA)] | M(HL)kH2O (M−1 s−1) | 1.46 ± 0.09 | 1.49 ± 0.05 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | |

| M(HL)kOH (M−1 s−1) | |||||

| log KM(HL)H | 8.7(1) | 8.4(2) | 7.8(2) | ||

| [Y(DOTA)] | M(HL)kH2O (M−1 s−1) | 1.49 ± 0.08 | 1.47 ± 0.07 | 1.37 ± 0.09 | |

| M(HL)kOH (M−1 s−1) | (4.8 ± 0.8) × 109 | (4.2 ± 0.7) × 109 | (4.4 ± 0.09) × 109 | ||

| log KM(HL)H | 8.60(3) | 8.47(2) | 8.13(5) | ||

| [Lu(DOTA)] | M(HL)kH2O (M−1 s−1) | 4.70 ± 0.08 (Yb3+: 4.4)a | 4.64 ± 0.09 | 4.68 ± 0.05 | |

| M(HL)kOH (M−1 s−1) | (1.1 ± 0.3) × 109 | (1.0 ± 0.4) × 109 | (1.5 ± 0.6) × 109 | ||

| log KM(HL)H | 8.40(2) (Yb3+: 8.4)a | 8.36 (2) | 8.15(1) | ||

| [Ga(DOTA)] | M(HL)kH2O (M−1 s−1) | 0.82 ± 0.07 | 1.00 ± 0.09 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | |

| M(HL)kOH (M−1 s−1) | (1.3 ± 0.1) × 1011 | (9 ± 1)×1010 | (1.0 ± 0.4) × 1011 | ||

| log KM(HL)H | 7.16(4) | 7.09(3) | 6.75(3) |

Reference 15.

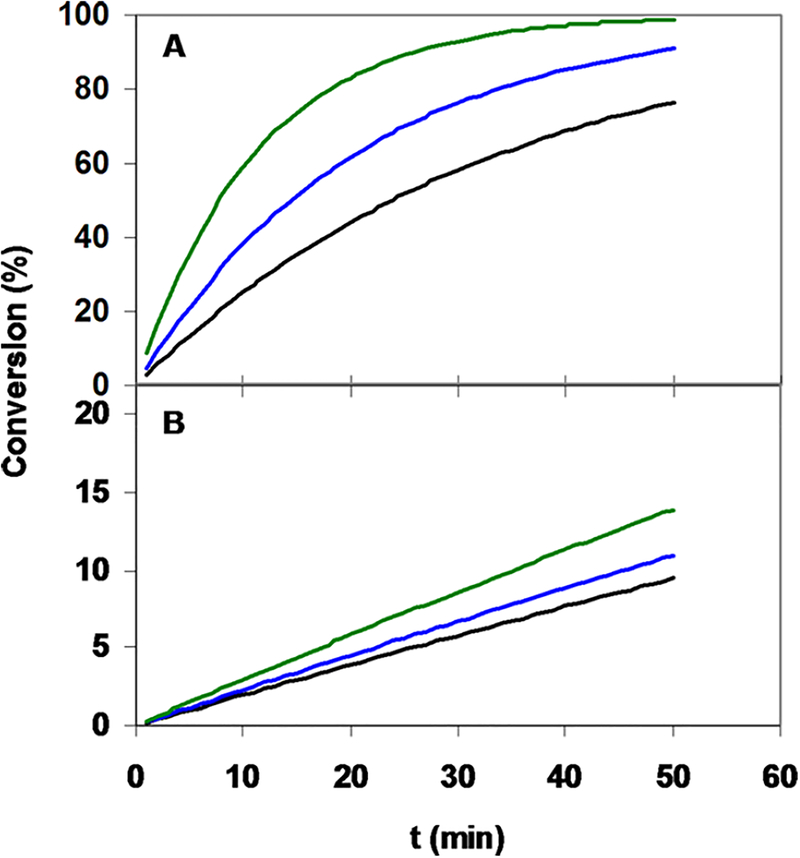

The rate constants that characterize the H2O- assisted deprotonation and rearrangement of the [M-(HDOTA)] intermediates to the final [M(DOTA)]− complexes increase from CeIII to LuIII, whereas the values are independent of the size of the LnIII ions. The value obtained for [Ga(DOTA)]− is smaller than those acquired for [Eu(DOTA)]−, [Y(DOTA)]−, and [Lu-(DOTA)]−, which can be explained by the different size and coordination number of GaIII and LnIII ions (GaIII, 0.62 Å; LnIII, 0.97−1.16 Å). The protonation constants of the monoprotonated intermediates decrease with a decrease of the size of the MIII ions and with an increase of [EtOH]. Reduction of the values with decreasing MIII size is due to the larger electrostatic repulsion between the protons on the ring N-donor atoms and the smaller MIII ions in the [M-(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates. The decrease of the values with increasing [EtOH] can be interpreted by a decrease of the basicity of the ring N-donor atoms in the [M-(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates. The basicity of the macrocyclic N-donor atoms of the free DOTA chelator analogously decreases in EtOH solutions (Table S2). On the basis of the kinetic data, the faster formation of [M(DOTA)]− complexes in EtOH solutions can be rationalized by a decrease of the log values. Deprotonation of the diprotonated [M-(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates seems to play a crucial role in the complex formation because the lower log values lead to higher concentrations of the kinetically active monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates. To highlight the effect of EtOH on the formation rate of [M(DOTA)]− complexes, the kobs rate constants characterizing the formation of [Ga(DOTA)]− and [Lu(DOTA)]− at pH 4.0 and 25 °C in the presence of 3.4 μM DOTA chelator in H2O and in 10 and 40 vol % EtOH solutions were calculated using eqs 10 and 13. The kobs rate constants that characterize the formation of [Ga(DOTA)]− and [Lu(DOTA)]− at pH 4.0 and 25 °C in the presence of 3.4 μM DOTA chelator were found to be 4.83 × 10−4, 8.00 × 10−4, and 1.49 × 10−3 s−1 for [Ga(DOTA)]− and 3.32 × 10−5, 3.86 × 10−5, and 5.00 × 10−5 s−1 for [Lu(DOTA)]− in H2O and in 10 and 40 vol % EtOH solutions, respectively. The extent of complex formation is shown in Figure 8. The calculated kobs rate constants and the data in Figure 8 show that, in the presence of 3.4 μM DOTA at pH 4.0, the increase of [EtOH] from 0 to 40 vol % results in approximately 3 and 1.5 times higher formation rate for [Ga(DOTA)]− and [Lu(DOTA)]−, respectively.

Figure 8.

Formation of [Ga(DOTA)]− (A) and [Lu(DOTA)]− (B) complexes in H2O and in 10 and 40 vol % EtOH solutions ([DOTA] = 3.4 μM, pH 4.0, 25 °C, 0.15 M NaCl).

Hydration/Solvation of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII Ions in H2O/EtOH Mixtures.

Because the complex formation occurs by the interaction of hydrated/solvated metal ions with the chelator, some knowledge of the hydration/solvation of MIII ions in H2O and in mixed solutions would be very helpful to better understand the mechanism of complex formation. Because the number and chemical nature of donor atoms coordinating to the MIII ion may influence the NMR chemical shift and relaxation time of the MIII nuclei, we studied the hydration/solvation of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII ions by multinuclear NMR spectroscopy in H2O/EtOH mixtures. The NMR studies were focused on the measurement of the longitudinal relaxation times (T1) of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII ions in H2O/EtOH mixtures because we anticipated that the coordination symmetry as well as the nature of the solvating species would significantly affect the T1 relaxation times. 71Ga, 45Sc, and 89Y NMR spectra of Ga(NO3)3, ScCl3, and YCl3 solutions obtained in H2O and in 10, 40, and 60 vol % EtOH solutions are shown in Figures S26–S28. The T1 values measured in H2O and in 10, 40, and 60 vol % EtOH solutions are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

T1 Values (ms) of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII Ions in H2O and in 10, 40, and 60 vol % EtOH Solutions

| H2O | 10 vol % EtOH |

40 vol % EtOH |

60 vol % EtOH |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GaIII (1.4 M HNO3) | 5.5 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 1.5 |

| ScIII (1.0 M HNO3) | 2.1 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| YIII (0.5 M HNO3) | 2.2 × 106 | 7.6 × 105 | 5.4 × 105 | 3.7 × 105 |

Generally, the exchange between the [M(H O)x]3+ and [M(H2O)x-1(X)]3+ species formed by solvation of the aqua MIII complexes is fast on the NMR time scale, so the chemical shifts of the observed signals represent a weighted average of the shifts of the different species involved in the specific solvation. Taking into account the lower affinity of the EtOH molecule to MIII ions, we assumed that some of the inner-sphere H2O molecules were replaced by EtOH ([M-(H2O)x-n(EtOH)n]3+). The presence of EtOH slightly influences the chemical shifts of 71Ga, 45Sc, and 89Y NMR signals of the solvated ions, which can be interpreted by the formation of [M(H2O)x-n(EtOH)n]3+ species (GaIII, x = 6; ScIII, x = 8; YIII, x = 8), which are in fast exchange with the [M(H2O)x]3+ aqua complex. The obtained NMR data are also consistent with the assumption that the presence of EtOH molecules in the inner sphere can influence the T1 values of GaIII, ScIII, and YIII ions. Because the relaxation of 71Ga and 45Sc nuclei takes place by a quadrupolar mechanism, the decrease of T1 values can be explained by the lower symmetry of [M(H2O)x−n(EtOH)n]3+ (GaIII, x = 6; ScIII, x = 8) species compared to the corresponding aqua ions. The dominant T1 (spin−lattice) relaxation mechanism of a 89YIII aqua ion is a combination of spin rotation and the more efficient dipolar interaction with the coordinated H2O and solvent protons. The observed marked decrease of T1 in the presence of EtOH is likely due to the replacement of some of the inner-sphere H2O molecules by EtOH, which decreases the contribution of spin rotation relaxation but speeds up dipolar relaxation. It is also likely that breaking of the symmetrical coordination environment of the YIII ion amplifies the contribution of other relaxation mechanisms, in particular, chemical shift anisotropy.30

CONCLUSIONS

It has been previously reported that nonaqueous solvents can influence the solvation and chelation of metal ions.10 In the present study, we investigated this phenomenon in the context of radiopharmaceutical chemistry. Here we provide compelling experimental evidence that performing the chelation in a mixture of H2O and a polar organic solvent (EtOH, iPrOH, and MeCN) can significantly speed up the complex formation and improve the radiolabeling yield. This is an important consideration, especially when the chelation is performed with an extremely low concentration of the radiometal, as is commonly the case in radiopharmaceutical synthesis. The following factors were found to have a significant influence on the chelation.

Impact of the Organic Solvent.

For a given reaction system and temperature, the addition of 40, 30, 20, or even 10 vol % of a nonaqueous solvent like EtOH, MeCN, or iPrOH has a direct and reproducible influence on the complex formation and radiolabeling yields. Depending on the solvent and reaction time, the addition of a nonaqueous solvent facilitates the formation reaction. The effect can be quite significant, in particular for short reaction times (≤10 min). The effect of the organic solvent depends on both the chelator and radiometal. For example, we observed the order EtOH < MeCN < iPrOH (t < 10 min) for 68Ga-DOTA complex formation, while the order was reversed (EtOH > MeCN > iPrOH; t < 10 min) for the formation of [44Sc]Sc-DOTA. For a given reaction system and temperature, the impact of different nonaqueous solvents grows with its increasing concentration. The greatest impact can be observed for reaction times of <10 min, which are especially of interest for radiolabeling with short-lived radiometals such as gallium-68, in which case the shorter reaction times can afford significant extra radioactivity in the final radiopharmaceutical preparation.

Impact on the Chelator Amount.

For a given reaction system, temperature, and reaction time, the addition of organic solvents increases the radiolabeling yields (Figure 2). Consequently, it is possible to achieve high radiochemical yields (>95%) even when the amount of chelator is reduced by a factor of 10. This translates into a 10-fold increase in the apparent molar radioactivity of the product, which is especially relevant in the context of receptor targeting.

Impact on the Duration of Synthesis.

Applying optimum reaction conditions, one might guarantee constant labeling yields of >98% in routine synthesis. This is well above the current recommendation published by the European Pharmacopoeia.31 Such high labeling yields may eliminate the need for radiochemical purification procedures. In practice, the duration of the synthesis from elution of the generator until formulation of the final product will be reduced because of the omission of the purification step. Effectively, this also contributes to an improvement in the final product radioactivity. This is particularly relevant for short-living radio-nuclides such as gallium-68: reducing the reaction time by 10 min results in nearly a 11% gain of radioactivity, i.e., increases the final product radioactivity by 11%.

Impact on the Formation Mechanism of [M(DOTA)]− Complexes.

According to the detailed physicochemical studies presented here, the solvation of the aqua [M(H2O)x]3+ complexes in the presence of EtOH may result in the formation of [M(H2O)x−n(EtOH)n]3+ species (GaIII, x = 6; ScIII, x = 8; YIII, x = 8). However, formation of the [M(DOTA)]− complex occurs through the formation of diprotonated [M(H2DOTA)]+ intermediates in both H2O and H2O/EtOH mixtures. The rate-controlling step is the H2O- and OH− -assisted deprotonation and rearrangement of the monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates formed in fast equilibrium with the diprotonated [M(H2DOTA)] intermediates. Thus, hydration/solvation of the MIII ion does not play an important role in the formation rate of [M(DOTA)]− complexes. EtOH or any other organic solvent indirectly accelerates the formation rate of [M-(DOTA)]− complexes by decreasing the protonation constant of the monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediates. This, in turn, results in the formation of the kinetically active monoprotonated [M(HDOTA)] intermediate in higher concentration, which speeds up formation of the final complex.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project was carried out in the frame of the EU COST Action CA15209: European Network on NMR Relaxometry. Support by the EU and the European Regional Development Fund (Projects GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00008 and GINOP-2.3.3-15-2016-00004) are gratefully acknowledged. The 89Y hyperpolarization experiments were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant P41-EB015908.

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00669.

General experimental procedures, details of equilibrium, kinetic studies, and 71Ga, 45Sc, and 89Y NMR data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Bünzli J-CG; Choppin GR Lanthanide probes in life, chemical and earth sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; pp 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- (2).De Leon-Rodriguez LM; Kovacs Z The synthesis and chelation chemistry of DOTA- peptide conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem 2008, 19 (2), 391–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cooper MS; Sabbah E; Mather SJ Conjugation of chelating agents to proteins and radiolabeling with trivalent metallic isotopes. Nat. Protoc 2006, 1 (1), 314–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Pruszynski M; Majkowska-Pilip A; Loktionova NS; Eppard E; Roesch F Radiolabeling of DOTATOC with the long-lived positron emitter 44Sc. Appl. Radiat. Isot 2012, 70 (6), 974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Coenen HH; Gee AD; Adam M; Antoni G; Cutler CS; Fujibayashi Y; Jeong JM; Mach RH; Mindt TL; Pike VW; Windhorst AD Open letter to journal editors on: International Consensus Radiochemistry Nomenclature Guidelines. Ann. Nucl. Med 2018, 32 (3), 236–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Feig M Biomolecular Solvation in Theory and Experiment. Modeling Solvent Environments; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Berlin: 2010; pp 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Richens DT The Chemistry of Aqua Ions: Synthesis, Structure and Reactivity: A Tour Through the Periodic Table of the Elements; Wiley: Chichester, U.K., 1997. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Ohtaki H; Radnai T Structure and dynamics of hydrated ions. Chem. Rev 1993, 93 (3), 1157–1204. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Burgess J Ions in Solution: Basic Priknciples of Chemical Interactions; Ellis Horwood: Chichester, U.K., 1988; pp 125–143. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Eppard E; Pèrez-Malo M; Rösch F Improved radiolabeling of DOTATOC with trivalent radiometals for clinical application by addition of ethanol. EJNMMI Radiopharmacy and Chemistry 2016, 1(1), 6–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Brücher E; Laurenczy G; Makra ZS Studies on the kinetics of formation and dissociation of the cerium(III)-DOTA complex. Inorg. Chim. Acta 1987, 139 (1), 141–142. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kumar K; Tweedle MF Ligand Basicity and Rigidity Control Formation of Macrocyclic Polyamino Carboxylate Complexes of Gadolinium(Iii). Inorg. Chem 1993, 32 (20), 4193–4199. [Google Scholar]

- (13).Kasprzyk SP; Wilkins RG Kinetics of interaction of metal ions with two tetraazatetraacetate macrocycles. Inorg. Chem 1982, 21(9), 3349–3352. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Tóth É ; Brücher E; Lázár I; Tóth I Kinetics of Formation and Dissociation of Lanthanide(III)-DOTA Complexes. Inorg. Chem 1994, 33 (18), 4070–4076. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Burai L; Fábián I; Király R; Szilágyi E; Brücher E Equilibrium and kinetic studies on the formation of the lanthanide(III) complexes, [Ce(DOTA)]- and [Yb(DOTA)]- (H4DOTA = 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetic acid). J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans 1998, 2, 243–248. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cossy C; Merbach AE Recent developments in solvation and dynamics of the lanthanide(III) ions. Pure Appl. Chem 1988, 60 (12), 1785–1796. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Micskei K; Powell DH; Helm L; Brücher E; Merbach AE Water exchange on [Gd(H2O)8]3+ and [Gd(PDTA)(H2O2)]- in aqueous solution: A variable-pressure, - temperature and -magnetic field 17O NMR study. Magn. Reson. Chem 1993, 31 (11), 1011–1020. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Margerum DW; Cayley GR; Weatherburn DC; Pagenkopf GK In Coordination Chemistry; Martell AE, Ed.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, 1978; Vol. 2, pp 1–220. [Google Scholar]

- (19).Idrissi A; Longelin S The study of aqueous isopropanol solutions at various concentrations: low frequency Raman spectroscopy and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Mol. Struct 2003, 651−653, 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Helm L; Merbach AE Inorganic and bioinorganic solvent exchange mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2005, 105 (6), 1923–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Covell DG; Wallqvist A Analysis of protein-protein interactions and the effects of amino acid mutations on their energetics. The importance of water molecules in the binding epitope.J. Mol. Biol 1997, 269 (2), 281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Desreux JF; Merciny E; Loncin MF Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance and Potentiometric Studies of the Protonation Scheme of 2 Tetraaza Tetraacetic Macrocycles. Inorg. Chem 1981, 20 (4), 987–991. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Rorabacher DB; MacKellar WJ; Shu FR; Bonavita SM Solvent effects on protonation constants. Ammonia, acetate, polyamine, and polyaminocarboxylate ligands in methanol-water mixtures. Anal. Chem 1971, 43 (4), 561–573. [Google Scholar]

- (24).Chaves S; Delgado R; Da Silva JJ The stability of the metal complexes of cyclic tetra-aza tetra-acetic acids. Talanta 1992, 39 (3), 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Wu SL; Horrocks WD Kinetics of Complex-Formation by Macrocyclic Polyaza Polycarboxylate Ligands - Detection and Characterization of an Intermediate in the Eu3+-DOTA System by Laser-Excited Luminescence. Inorg. Chem 1995, 34 (14), 3724–3732. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Moreau J; Guillon E; Pierrard JC; Rimbault J; Port M; Aplincourt M Complexing mechanism of the lanthanide cations Eu3+, Gd3+, and Tb3+ with 1,4,7,10-tetrakis(carboxymethyl)-1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (DOTA) - Characterization of three successive complexing phases: Study of the thermodynamic and structural properties of the complexes by potentiometry, luminescence spectroscopy, and EXAFS. Chem. - Eur. J 2004, 10 (20), 5218–5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cassatt JC; Wilkins RG The kinetics of reaction of nickel(II) ion with a variety of amino acids and pyridinecarboxylates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1968, 90 (22), 6045–6050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Kubicek V; Havlickova J; Kotek J; Tircso G; Hermann P; Toth E; Lukes I Gallium(III) complexes of DOTA and DOTA-monoamide: kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Inorg. Chem 2010, 49 (23), 10960–10969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Baes CF; Mesmer RE The Hydrolysis of Cations; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1976; pp 129 (Ln3+) and pp 313 (Ga3+). [Google Scholar]

- (30).Levy GC; Rinaldi LP; Bailey JT Yttrium-89 NMR. A possible spin relaxation probe for studying metal ion interactions with organic ligands. J. Magn. Reson 1980, 40 (1), 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- (31).European Pharmacopoeia: 8.6 to 8.8; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.