With the recent advances in processing carbohydrates in lignocellulosics for bioproducts, almost all biological conversion platforms result in the formation of a significant amount of lignin by-products, representing the second most abundant feedstock on earth. However, this resource is greatly underutilized due to its heterogeneity and recalcitrant chemical structure. Thus, exploiting lignin valorization routes would achieve the complete utilization of lignocellulosic biomass and improve cost-effectiveness. The culture conditions that encourage cell growth and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) accumulation are different. Such an inconsistency represents a major hurdle in lignin-to-PHA bioconversion. In this study, we traced and compared transcription levels of key genes involved in PHA biosynthesis pathways in Pseudomonas putida A514 under different nitrogen concentrations to unveil the unusual features of PHA synthesis. Furthermore, an inducible strong promoter was identified. Thus, the molecular features and new genetic tools reveal a strategy to coenhance PHA production and cell growth from a lignin derivative.

KEYWORDS: Pseudomonas putida, lignin-consolidated bioprocessing, polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis

ABSTRACT

Cell growth and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) biosynthesis are two key traits in PHA production from lignin or its derivatives. However, the links between them remain poorly understood. Here, the transcription levels of key genes involved in PHA biosynthesis were tracked in Pseudomonas putida strain A514 grown on vanillic acid as the sole carbon source under different levels of nutrient availability. First, enoyl-coenzyme A (CoA) hydratase (encoded by phaJ4) is stress induced and likely to contribute to PHA synthesis under nitrogen starvation conditions. Second, much higher expression levels of 3-hydroxyacyl-acyl carrier protein (ACP) thioesterase (encoded by phaG) and long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase (encoded by alkK) under both high and low nitrogen (N) led to the hypothesis that they likely not only have a role in PHA biosynthesis but are also essential to cell growth. Third, 40 mg/liter PHA was synthesized by strain AphaJ4C1 (overexpression of phaJ4 and phaC1 in strain A514) under low-N conditions, in contrast to 23 mg/liter PHA synthesized under high-N conditions. Under high-N conditions, strain AalkKphaGC1 (overexpression of phaG, alkK, and phaC1 in A514) produced 90 mg/liter PHA with a cell dry weight of 667 mg/liter, experimentally validating our hypothesis. Finally, further enhancement in cell growth (714 mg/liter) and PHA titer (246 mg/liter) was achieved in strain Axyl_alkKphaGC1 via transcription level optimization, which was regulated by an inducible strong promoter with its regulator, XylR-PxylA, from the xylose catabolic gene cluster of the A514 genome. This study reveals genetic features of genes involved in PHA synthesis from a lignin derivative and provides a novel strategy for rational engineering of these two traits, laying the foundation for lignin-consolidated bioprocessing.

IMPORTANCE With the recent advances in processing carbohydrates in lignocellulosics for bioproducts, almost all biological conversion platforms result in the formation of a significant amount of lignin by-products, representing the second most abundant feedstock on earth. However, this resource is greatly underutilized due to its heterogeneity and recalcitrant chemical structure. Thus, exploiting lignin valorization routes would achieve the complete utilization of lignocellulosic biomass and improve cost-effectiveness. The culture conditions that encourage cell growth and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) accumulation are different. Such an inconsistency represents a major hurdle in lignin-to-PHA bioconversion. In this study, we traced and compared transcription levels of key genes involved in PHA biosynthesis pathways in Pseudomonas putida A514 under different nitrogen concentrations to unveil the unusual features of PHA synthesis. Furthermore, an inducible strong promoter was identified. Thus, the molecular features and new genetic tools reveal a strategy to coenhance PHA production and cell growth from a lignin derivative.

INTRODUCTION

Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) are a class of natural biopolymers that are accumulated by microbes as carbon and energy storage materials (1). They can be used as alternatives to petroleum-based plastics due to their environmentally friendly aspects of sustainability and low CO2 emissions. In addition, their biocompatibility and biodegradability allow them to be bioimplant materials for medical and therapeutic applications (2). Moreover, their controllable thermal and mechanical properties, as well as diverse molecular weights, allow PHA to function as chemical precursors and methyl ester-based fuels (1, 3, 4). The high PHA content (21% of the cellular dry weight) observed in Escherichia coli was biosynthesized from fatty acids as early as 1997 (5). However, due to the high cost of fatty acids and their toxicity to bacteria, researchers have attempted to bioproduce PHA from inexpensive and renewable unrelated carbon sources, e.g., glucose and glycerol (6–8). Lignocellulose is the most abundant resource for sustainable fuels and chemical production. With the development of cellulosic biofuel production, substantial quantities of lignin by-products are expected to be generated, representing the second most abundant feedstock on earth (9). However, the recalcitrant nature of lignins and certain technological barriers limit lignin mainly to production of process heat and power via combustion during cellulosic biofuel production (10–12). Thus, finding an efficient conversion route for lignin to PHA would offer a significant opportunity for the viability and sustainability of modern lignocellulosic biorefineries and offset global energy shortages and climate change (13). A few studies have investigated the feasibility of lignin-to-PHA bioconversion routes, including bacterial screening for lignin-consolidated bioprocessing (14, 15) and integrated biological funneling and chemical catalysis for lignin-to-PHA production (3). However, few studies have attempted to study the PHA biosynthetic pathways when strains are grown using either lignin or its derivatives as a sole carbon source (16), most likely because the complex process of lignin depolymerization in lignin-to-PHA bioconversion has hampered investigations and comparisons between PHA biosynthesis pathways. Thus, the molecular mechanisms of PHA biosynthesis, in which various metabolic pathways of fatty acids interact to mediate carbon flux to PHA biosynthesis pathways under conditions where strains are grown on lignin (or its derivatives), remain elusive.

Pseudomonas species are well-known medium-chain-length PHA (mcl-PHA)-producing organisms (17), and recent studies have shown that they are capable of lignin degradation (18). They secrete oxidative enzymes (e.g., laccases and dye peroxidases) to trigger lignin decomposition and generation of lignin oligomers (e.g., β-aryl-ether and coniferyl aldehyde), which are subsequently catabolized via versatile aromatic compound pathways (19–21). In addition, they adapt easily to different environments and have readily available genetic manipulation systems (16, 22). Taken together, these traits indicate they could play a profound role in lignin-to-PHA conversion. Pseudomonas species readily accumulate mcl-PHA under nutrient imbalances, e.g., nitrogen starvation conditions (1). Under nitrogen limitation, strains usually exhibit poor growth (e.g., lower cell density, lighter cell dry weight, or lower growth rate) (14, 23). It should be noted that cell growth (cell biomass in particular) is a critical factor for total PHA production (7). Such an inconsistency between cell growth and PHA production represents one of three major hurdles in lignin-to-PHA bioconversion, the others being lignin depolymerization and aromatic compound degradation. In fact, numerous studies have investigated the PHA biosynthesis pathways in Pseudomonas, where PHA is synthesized via either the β-oxidation pathway or by the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis pathway when the organisms are grown on related (e.g., fatty acids) or unrelated (e.g., glucose and glycerol) carbon sources, respectively (1, 24, 25). Moreover, a large number of strategies have been developed to enhance PHA production, such as reconstructing PHA synthetic pathways in model hosts without the ability for PHA accumulation (e.g., E. coli) (6, 7, 25–27). However, simultaneous improvement of both cell growth and PHA production in Pseudomonas has not been demonstrated, especially when lignin or its derivatives are used as sole carbon sources. Devising a rational strategy to counter this hurdle may require a mechanistic understanding of the links between the two traits.

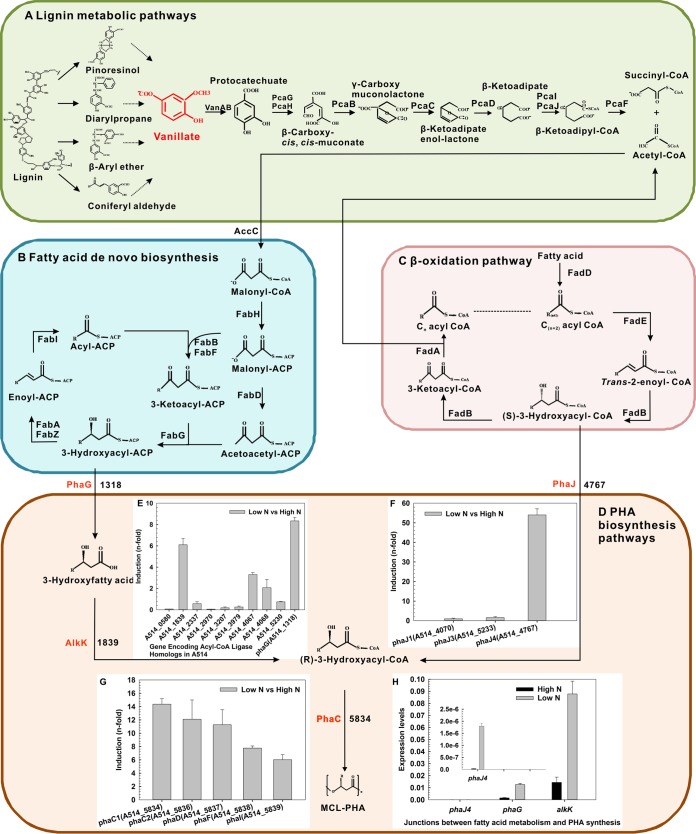

Here, we employed the previously identified lignin-utilizing Pseudomonas putida strain A514 as a research model to investigate the PHA biosynthesis pathways. To simplify the lignin depolymerization process, we utilized a lignin substitute, vanillic acid, a key intermediate metabolite that connects several peripheral pathways to the central pathway (β-ketoadipate pathway) during lignin depolymerization, as the sole carbon source (Fig. 1A) (16, 18). The transcription levels of key genes involved in PHA biosynthesis were tracked and compared when A514 cells were grown on M9 medium with low (65 mg/liter) and high (1 g/liter) nitrogen (N) concentrations, unveiling unusual features of PHA synthesis. Exploiting these molecular features and developing genetic tools enabled us to devise a rational strategy to coenhance PHA production and cell growth.

FIG 1.

Proposed metabolic pathways for lignin-to-PHA bioconversion. Key genes and metabolic intermediates are highlighted in red. Identifications (IDs) of the corresponding genes in A514 are shown. (A) Lignin degradation pathways. Dashed arrows indicate multiple steps. (B) De novo fatty acid biosynthesis. (C) β-Oxidation pathway. After each turn of the cycle, an acyl-CoA (indicated as Cn) that is two carbons shorter than the initial one (indicated as Cn + 2) is generated. The dashed line connects acyl-CoA intermediates of different chain lengths. (D) PHA biosynthesis pathways. (E, F, and G) Expression ratios for alkK homologs and phaG and phaJ genes, as well as for PHA synthetic genes, in A514 that were grown under the low-N conditions, compared to those grown under the high-N conditions. The ratios that were >1 were defined as induced. (H) Expression levels of the phaJ4, phaG, and alkK (PputA514_1839) genes in A514 under both high-N and low-N conditions. The inset in panel H shows the expression level of phaJ4 at an appropriate scale. The expression levels and expression ratios are defined in Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

Transcriptional comparison revealed specific features of PHA synthesis in A514 when a lignin derivative was used as the sole carbon source.

P. putida A514 was grown on either high-N or low-N M9 medium, supplemented with 15 mM vanillic acid as the sole carbon source. First, it was observed that the doubling time of A514 cells grown on high-N medium (4.8 h) was higher than that of cells grown on low-N medium (3.8 h) during the exponential phase (Table 1 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Second, cell dry weight (CDW) under high-N conditions was approximately 6-fold higher than under low-N conditions (Table 1). Third, 15 mM vanillic acid was completely consumed under high-N growth conditions, whereas only 6.5 mM vanillic acid was utilized under low-N conditions (Table 1 and Fig. S1). Taken together, these results indicate a likely change in gene expression in A514 between the high-N and low-N growth conditions. Thus, the transcription levels of genes involved in PHA synthesis under these two conditions were subsequently examined by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR) (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Cell growth and mcl-PHA accumulation in the recombinant P. putida A514 strains

| Culturea | Strain | Relevant plasmid | Doubling timeb (h) | VAc utilization (mM) | CDWd (mg/liter) | PHA titer (mg/liter) | PHA content (wt %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High N (1 g/liter) | A514 WT | None | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 14.9 ± 0.01 | 664.1 ± 3.6 | 11 ± 2.0 | 1.7 ± 0.3 |

| APvan | pPvan | 4.7 ± 0.3 | 14.8 ± 0.01 | 664.6 ± 2.2 | 12 ± 1.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | |

| AphaJ4C1 | pTJ4C1 | 4.6 ± 0.3 | 15.0 ± 0.02 | 668.0 ± 3.5 | 23 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | |

| AalkKphaGC1 | pTphaGC1 | 4.5 ± 0.2 | 14.9 ± 0.01 | 667.5 ± 4.8 | 90 ± 2.1 | 13.5 ± 0.3 | |

| AR-PxylA | pTRPxylA | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 15.0 ± 0.01 | 694.7 ± 11.1 | 12 ± 0.6 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | |

| Axyl_phaJ4C1 | pTPxylAphaGC1 | 4.8 ± 0.1 | 15.0 ± 0.02 | 702.7 ± 19.4 | 26 ± 1.7 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | |

| Axyl_alkKphaGC1 | pTPxylAphaJ4C1 | 4.8 ± 0.2 | 15.0 ± 0.01 | 714.8 ± 12.9 | 246 ± 17.3 | 34.4 ± 0.3 | |

| Low N (65 mg/liter) | A514 WT | None | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 0.03 | 133.8 ± 10.9 | 23 ± 1.0 | 17.3 ± 1.8 |

| APvan | pPvan | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 6.6 ± 0.06 | 135.5 ± 5.8 | 23 ± 3.8 | 17.1 ± 2.1 | |

| AphaJ4C1 | pTJ4C1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 7.4 ± 0.05 | 133.0 ± 7.8 | 43 ± 1.5 | 32.6 ± 1.2 | |

| AalkKphaGC1 | pTphaGC1 | 3.9 ± 0.1 | 7.6 ± 0.05 | 145.2 ± 7.3 | 62 ± 6.1 | 42.4 ± 2.2 | |

| AR_PxylA | pTRPxylA | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 7.5 ± 0.04 | 148.7 ± 6.1 | 24 ± 0.6 | 16.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Axyl_phaJ4C1 | pTPxylAphaGC1 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 7.9 ± 0.04 | 141.3 ± 12.3 | 63 ± 2.3 | 44.5 ± 4.9 | |

| Axyl_alkKphaGC1 | pTPxylAphaJ4C1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.04 | 175.3 ± 13.3 | 116 ± 4.5 | 66.3 ± 4.7 |

The strains were grown in 15 mM vanillic acid-M9 medium under either high-N (1 g/liter) or low-N (65 mg/liter) conditions.

The doubling time (DT) was calculated during the exponential phase, based on the formula DT = t · [log 2/(log Nt − log N0)].

VA, vanillic acid.

CDW, cell dry weight.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in qRT-PCR

| Primer | Sequences |

|---|---|

| PputA514_5834 | F: 5′-TCACCGCCGACATCTACTC-3′; R: 5′-CTGCTGGACAACACGAACTC-3′ |

| PputA514_5836 | F: 5′-CACTTCGCATTCGCCTTGT-3′; R: 5′-TGTTGCCGCCTGAGTTGA-3′ |

| PputA514_5834 | F: 5′-GCGACCGTATCCTTGAATGT-3′; R: 5′-GAAGTGGTAGTAGAGGTTGCC-3′ |

| PputA514_5838 | F: 5′-GCGTCTCAACAGTGCTAT-3′; R: 5′-TTTGCTTGGTCAGGGTATC-3′ |

| PputA514_5839 | F: 5′-AGTAATGTCTCAAGCGTCAA-3′; R: 5′-TGCCGATTCGATTCAAGG-3′ |

| PputA514_4767 | F: 5′-ATTATGTCGGCAAGGAACT-3′; R: 5′-GACGTGGATGAACTGATGA-3′ |

| PputA514_4070 | F: 5′-TGTTCAAGGAGCGTATCG-3′; R: 5′-GGCTTCTGGAAGGTCATC-3′ |

| PputA514_5233 | F: 5′-CAAAGGTCTTTGGCTTTCGC-3′; R: 5′-CAGGAAGATTGGCAGCTTGA-3′ |

| PputA514_1318 | F: 5′-GCCTGTATCCGCAATTCAAC-3′; R: 5′-CCTTCGTCAGCATCTTCTCAT-3′ |

| PputA514_1839 | F: 5′-CCAGATCGCCGTTGTTACT-3′; R: 5′-GCCTGCCATTCAATGATGTC-3′ |

| PputA514_2970 | F: 5′-TCAGGATCAGGACCTTGC-3′; R: 5′-GCGTAACACAGCGACATA-3′ |

| PputA514_4067 | F: 5′-CCACATCTATGCCTTCACCTT-3′; R: 5′-CTTCCACTTCGACAGTTCCTT-3′ |

| PputA514_4068 | F: 5′-GGTTCGTGAGCATTGTTG-3′; R: 5′-CGTCTTCGATCTCGTTGG-3′ |

| PputA514_5230 | F: 5′-CAAAGACCCGAACCTGACTC-3′; R: 5′-TGCTGCGAAACTCCACATAC-3′ |

| PputA514_3207 | F: 5′-ACCACAACATCCTCAACAA-3′; R: 5′-ATACCGAAGCAGTGATACAA-3′ |

| PputA514_0580 | F: 5′-TGTGGAACTGGCTGGTGTC-3′; R: 5′-GCTGATTGTCTCGGCATCG-3′ |

| PputA514_3979 | F: 5′-TGAAGATGGCTACTGGTGGAT-3′; R: 5′-TCGGCGACTTTAGGGTGAG-3′ |

| PputA514_2337 | F: 5′-CCATCCGATCACCTTCTACGA-3′; R: 5′-GGCAATCAGCAGGCGATAC-3′ |

| PputA514_4978 | F: 5′-GGCAACGAAGTGGATGAA-3′; R: 5′-CTGGCAACGGATGATGTC-3′ |

Similarly to that of P. putida strain KT2440, the A514 pha gene cluster consists of phaC1 and phaC2, encoding two polymerases, phaZ, encoding a depolymerase, phaD, encoding a transcriptional regulator, and two genes encoding polyhydroxyalkanoate granule-associated proteins (phaF and phaI) (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The organization of these genes in the A514 genome is also similar to that of P. putida KT2440, consistent with previous studies showing that the PHA biosynthetic gene cluster is well conserved among the Pseudomonas PHA producer strains (17) (Fig. S2). Comparison of gene transcription under high-N and low-N conditions revealed several characteristics of PHA synthesis in A514 when employing a lignin derivative (vanillic acid) as the sole carbon source. First, genes located in the PHA synthesis cluster were upregulated, including phaC1 (PputA514_5834), phaC2 (PputA514_5836), phaD (PputA514_5837), phaF (PputA514_5838), and phaI (PputA514_5839) (Fig. 1D and G), confirming the phenotype that PHA synthesis was induced under nitrogen deprivation (Fig. S1). Second, phaG (PputA514_1318) and alkK (PputA514_1839) were induced (Fig. 1B and E). phaG (encoding 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP thioesterase), combined with alkK (encoding fatty acid-CoA ligase), provides 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA, the precursor for PHA synthesis (6), thus connecting the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis pathway and the PHA biosynthesis pathway. The induced phaG gene demonstrated its role in PHA synthesis in the presence of vanillic acid as the carbon source. In addition, nine paralogs that are homologous to the alkK gene from P. putida KT2440 were identified in A514, and their transcription levels were examined (6, 28). Among them, PputA514_1839 (encoding a long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase) was prominent in that it not only encoded the highest protein identity (89%; E value, 0) to AlkK of P. putida KT2440, but also showed the highest level of transcription (Fig. 1E), suggesting its probable contribution in the production of 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA for PHA production. Third, phaJ4, which connects the β-oxidation pathway and the PHA synthesis pathway, was highly upregulated (∼54-fold) (Fig. 1C and F). phaJ [encoding (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase] produces 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA from fatty acid oxidation as the precursor for PHA biosynthesis (7). A514 harbors three phaJ paralogs, namely, phaJ1 (PputA514_4070), phaJ3 (PputA514_5233), and phaJ4 (PputA514_4767). Among them, phaJ4 exhibited the highest induction (Fig. 1F), suggesting an important role for this gene in directing carbon flux from the β-oxidation pathway to PHA biosynthesis. This is consistent with our previous study, where overexpressing phaJ4 and phaC1 increased PHA production when lignin was used as the sole carbon source (16). Fourth, compared to phaJ4, phaG and alkK sustained much higher expression levels under both high- and low-N conditions, indicating that, in addition to PHA synthesis, they were likely to be important in cell growth (Fig. 1H). Furthermore, comparison of low-N and high-N conditions showed that phaJ4 was highly induced (∼54-fold), in contrast to phaG and alkK, which showed only ∼6-fold activation (Fig. 1E and F). This was distinct from the PHA-producing model strain, P. putida KT2440, where it was phaG that presented the greatest induction (∼220-fold versus 3.8-fold for phaJ4) when grown on low-N medium compared to high-N medium (6), suggesting specific features of PHA synthesis in A514 when utilizing vanillic acid as the carbon source.

Increasing carbon flux from de novo fatty acid biosynthesis to PHA synthesis can simultaneously improve PHA production and cell growth.

Our previous study demonstrated that phaJ4 and phaC1 are important for PHA biosynthesis from lignin under nitrogen starvation conditions in A514 cultures (16). However, the unique transcriptional feature of phaG and alkK, in this study, suggested their role in both PHA biosynthesis and cell survival, thus raising the feasibility of enhancing PHA production without impairing cell growth. To validate this hypothesis, the plasmid pPvan, plasmid pPROBE-TT carrying the Pvan promoter, was employed as the expression vector (Table 3) (29). phaG (PputA514_1318), alkK (PputA514_1839), and phaC1 (PputA514_5834) were cloned into pPvan to construct the plasmid pTphaGC1, while phaJ4 (PputA514_4767) and phaC1 (PputA514_5834) were cloned into pPvan, generating the pTJ4C1 vector. The three plasmids were subsequently transformed into strain A514, generating the recombinant strains APvan, AalkKphaGC1, and AphaJ4C1, respectively (Table 3). AalkKphaGC1 was subsequently characterized for cell growth and PHA production, while AphaJ4C1 and APvan were used as reference strains.

TABLE 3.

Plasmids and bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source and/or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pPROBE-TT | 30 | |

| pPvan | pPROBE-TT derivative, P. putida A514 promoter of vanAB (Pvan) | This study |

| pTJ4C1 | pPROBE-TT derivative, Pvan, phaJ4, and phaC1 | This study |

| pTphaGC1 | pPROBE-TT derivative, Pvan, phaG, alkK, and phaC1 | This study |

| pTPxylA | pPROBE-TT derivative, P. putida A514 promoter of xylA (PxylA) | This study |

| pTRPxylA | pPROBE-TT derivative, PxylA, and xylR | This study |

| pTPxylAphaGC1 | pPROBE-TT derivative, PxylA, phaG, alkK, and phaC1 | This study |

| pTPxylAphaJ4C1 | pPROBE-TT derivative, PxylA, phaJ4, and phaC1 | This study |

| Strains | ||

| P. putida A514 | Wild type | Dennis Gross lab (TAMU) (17) |

| AT | A514 carrying pPROBE-TT | This study |

| APvan | A514 carrying pPvan | This study |

| AphaJ4C1 | A514 carrying pTJ4C1 | This study |

| AalkKphaGC1 | A514 carrying pTphaGC1 | This study |

| APxylA | A514 carrying pTPxylA | This study |

| AR-PxylA | A514 carrying pTRPxylA | This study |

| Axyl_phaJ4C1 | A514 carrying pTPxylAphaJ4C1 | This study |

| Axyl_alkKphaGC1 | A514 carrying pTPxylAphaGC1 | This study |

Under nitrogen excess conditions, AalkKphaGC1 showed significant improvement in PHA titer, which increased to 90 mg/liter, although levels of cell growth and vanillic acid utilization for all three strains were similar (Table 1 and Fig. S3A). Under nitrogen limitation conditions, AalkKphaGC1 showed improvement in cell biomass compared to that of APvan (P = 0.016; Table 1 and Fig. S3B). In addition, AalkKphaGC1 produced 54% and 166% more PHA than did AphaJ4C1 and APvan, respectively, reaching ∼62 mg/liter (Table 1 and Fig. S3B). Corresponding to the higher CDW and PHA titer, more vanillic acid was consumed by AalkKphaGC1 than by APvan (P = 0.006, Table 1 and Fig. S3B).

These data demonstrate two aspects of the mechanism for PHA biosynthesis from vanillic acid. First, although increasing 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA from either the de novo fatty acid biosynthesis pathway or β-oxidation pathway improved PHA production, overexpression of phaG and alkK contributed more to PHA production in strain A514, especially under conditions of excess nitrogen (Table 1 and Fig. S3). Second, when A514 cells were grown under conditions favoring PHA accumulation (nutrition imbalance), enhancing the expression levels of phaG and alkK coimproved cell growth and PHA biosynthesis. On the basis of these results, we experimentally validated the role of phaG and alkK in PHA production and cell growth, and we suggest that this property could be further exploited to coenhance cell growth and PHA production.

Screening an inducible strong promoter to regulate the transcription levels of phaG and alkK from strain A514.

In AalkKphaGC1, the PHA synthetic gene cluster from pTphaGC1 was constitutively expressed in the presence of vanillic acid, as the promoter Pvan was induced by vanillic acid (Table 3). PHA synthesis, thereby, was turned on during the initial cell growth period, likely causing a burden on AalkKphaGC1. Consequently, to further increase PHA production, an alternative inducible strong promoter was required to regulate the relevant gene expression.

For this purpose, a putative xylose catabolism gene cluster (xylAFGH), which appeared to be specifically induced by xylose, was targeted based on our previous genomics data (Fig. 2A) (16). The promoter sequence (PxylA) is located in the 160-bp intergenic region shared by the xylR (xylose operon regulatory protein) and xylA (xylose isomerase) genes. It was predicted by the PePPER webserver and cloned into the promoter probe vector pPROBE-TT, with a gfp (green fluorescent protein gene) reporter gene, generating the pTPxylA construction (29, 30) (Table 3). When APxylA (carrying pTPxylA in A514) was grown in M9 medium supplemented with 15 mM vanillic acid (rather than with xylose), the measured green fluorescence was close to background levels observed in A514 cells harboring the plasmid pPROBE-TT (designated AT) (Fig. 2B, bars 1 and 2, and Table 3). In contrast, an obvious green fluorescent signal was detected with the addition of xylose, confirming that the activity of PxylA was specifically induced by xylose (Fig. 2B, bar 3).

FIG 2.

Effect of the regulator, regulator-induced expression time, and inducer concentrations on the activity of the promoter PxylA. (A) Organization of the putative A514 xylose catabolism locus, as well as reporter constructs used to detect activity of PxylA. P, promoter; gfp, green fluorescent protein gene. (B) Activities of PxylA and Pvan under various inducing conditions. For bars 1 to 5, either 0 mM or 0.2 mM (final concentration) xylose was added when strains were at the mid-exponential phase. After 6 h of induction, green fluorescence intensity was measured to determine the promoter activity. Bars 6 and 7 represent the Pvan activity in APvan at the mid-exponential phase and the stationary phase, respectively. Bars 8 and 9 represent the XylR-PxylA activity in AR-PxylA at the stationary phase, which was exposed to 0 mM or 2 mM xylose for 12 h, respectively. pTT, pPROBE-TT; Con, concentration. (C) Time point-dependent induction of XylR-PxylA activity. Response of XylR-PxylA to different growth phases at which 0.2 mM xylose (final concentration) was added. Fluorescence intensity was measured every 3 h until AR-PxylA entered the stationary phase. (D) Xylose concentration-dependent induction of XylR-PxylA activity. AR-PxylA at the mid-exponential phase was exposed to different concentrations of xylose for 6 h. For panels B, C, and D, all of the strains were cultivated in M9 medium supplemented with 15 mM vanillic acid. Fluorescence intensity, which was detected to determine the promoter activity, is expressed in arbitrary units normalized for 106 CFU.

To maximize the activity of PxylA, three crucial factors were investigated, as follows: the regulator, induced expression time, and inducer concentrations. First, xylR (PputA514_3011) enhanced the activity of PxylA. xylR is located immediately upstream of the xylAFGH cluster, with its transcription oriented in the opposite direction, suggesting a role in modulating xylAFGH expression in response to xylose (Fig. 2A). Therefore, we created a recombinant strain, AR-PxylA, bearing pTRPxylA (Table 3). When assayed in AR-PxylA, the promoter activity was distinctly enhanced, 2.4-fold higher than that with PxylA (Fig. 2B, bars 3 and 5), confirming that XylR is a positive regulator for PxylA. Second, a higher promoter activity was found when xylose was added during the mid-exponential phase. To examine the effect of the induced expression time on the PxylA activity, 0.2 mM xylose (final concentration) was added at three time points (during the early-to-mid exponential phase), and the level of green fluorescence was measured from time of addition to stationary phase. When xylose was added during the early exponential phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600], ∼0.36), promoter activity in APxylA was quickly switched on, reaching highest activity at 3 h and sustained at this level until stationary phase (15 h after induction began). In contrast, when xylose was added during the mid-exponential phase (OD600, ∼0.56 and ∼0.78), promoter activity increased along with the induced expression time and reached the highest activity at 12 h (stationary phase). Since higher green fluorescence intensity was detected in APxylA when xylose was supplemented at the mid-exponential phase than at the early exponential phase, xylose was added at the mid-exponential phase (e.g., at OD600 of ∼0.78) for the following study (Fig. 2C). Third, there was an inducer concentration-dependent effect on promoter activity, with a final concentration of 2 mM xylose being determined as the appropriate concentration. To assess the effect of different xylose concentrations, AR-PxylA was grown in M9 medium with 15 mM vanillic acid, reaching an OD600 of ∼0.78, and then exposed to various inducer concentrations (from 0.02 mM to 20 mM) for 6 h (Fig. 2D). It was determined that 2 mM xylose was sufficient to activate PPxylA.

Therefore, the optimized promoter activity of XylR-PxylA in the expression vector pTRPxylA was achieved when adding 2 mM xylose at an OD600 of ∼0.78 and was approximately 4-fold higher than that of APvan under 15 mM vanillic acid conditions (Fig. 2B, bars 7 and 9).

PHA production was further enhanced via transcription level optimization.

Next, the expression vector pTRPxylA was employed to coexpress the two PHA synthetic gene clusters in A514. Thus, two recombinant strains, Axyl_phaJ4C1 and Axyl_alkKphaGC1, were generated. Substrate utilization, cell growth, and PHA titers of these two strains were assessed (Table 1 and Fig. S4). (i) More vanillic acid was utilized by Axyl_alkKphaGC1 than by AalkKphaGC1 under nitrogen deprivation conditions (P = 6 × 10−6, Table 1 and Fig. S3 and S4). A similar trend was observed in Axyl_phaJ4C1, in contrast to in AphaJ4C1 (P = 1 × 10−4). (ii) In comparison with AalkKphaGC1, cell growth was further improved in Axyl_alkKphaGC1, especially under nitrogen starvation conditions. The growth rate and cell biomass of Axyl_alkKphaGC1 were both enhanced under the low-N conditions (P = 0.008 for doubling time and P = 0.019 for CDW; Table 1). In addition, a higher cell biomass of Axyl_alkKphaGC1 was also obtained under the high-N conditions (P = 0.003; Table 1). (iii) Axyl_alkKphaGC1 and Axyl_phaJ4C1 produced more PHA titer than AalkKphaGC1 and AphaJ4C1, respectively (P values < 0.05), whereas APvan and AR-PxylA produced PHA titers similar to that of A514 (P values > 0.05; Table 1 and Fig. S3 and S4). This indicated that the PHA titer was improved by regulating the transcription levels of key genes. A514 and APvan cultures (carrying promoter Pvan in the plasmid pPROBE-TT) were grown in vanillic acid-M9 medium, while AR-PxylA cells (carrying promoter R-PxylA in the plasmid pPROBE-TT) were grown in vanillic acid-M9 medium with 2 mM xylose inducer added at the mid-exponential phase (OD600, ∼0.78). The similar PHA titers among the three strains (P values > 0.05) suggested that 2 mM xylose has very little contribution to PHA synthesis. (iv) Although the highest PHA content (wt %, 66) was reached in Axyl_alkKphaGC1 under low-N conditions, the greatest PHA titer was produced by Axyl_alkKphaGC1 under high-N conditions, reaching ∼250 mg/liter in a single fermentation batch (Table 1 and Fig. S4B). This would be the result of more cell biomass being obtained in Axyl_alkKphaGC1 under high-N conditions, demonstrating the role of the cell biomass in PHA production. (v) Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) composition analysis revealed that the PHA produced were medium-chain-length PHA (mcl-PHA) (C6 to C14). Compared to that in AR-PxylA, the major units in Axyl_alkKphaGC1 PHA polymers were shifted from shorter-carbon-chain units to longer-carbon-chain units. Under nitrogen starvation conditions, 3-hydroxydecanoate (3HD, C10) (∼33%) and 3-hydroxytetradecanoate (3HTD, C14) (∼23%) were the major units in Axyl_alkKphaGC1, while the 3HD and 3HTD content in mcl-PHA synthesized in Axyl_phaJ4C1 also increased. In contrast, the major PHA component of AR-PxylA was 3-hydroxyhexanoate (3HHx, C6), ∼45% (Table 4). Under nitrogen excess conditions, 3HD (∼41%) and 3-hydroxyoctanoate (3HO, C8) (∼31%) were the major monomers in Axyl_alkKphaGC1, while 3HHx accounted for approximately ∼57% of the PHA polymers of AR-PxylA. In particular, 3HTD (∼3%) was detected in mcl-PHA produced by Axyl_alkKphaGC1, whereas it was not found in mcl-PHA produced by AR-PxylA or Axyl_phaJ4C1 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

GC compositional analysis of mcl-PHA produced by recombinant P. putida A514 strainsa

| Strain | Culture | PHA composition (mol%)b |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3HHx (C6) | 3HO (C8) | 3HD (C10) | 3HDD (C12) | 3HTD (C14) | ||

| APvan | High N (1 g/liter) | 56.0 ± 4.8 | ND | 21.7 ± 1.2 | 22.3 ± 1.0 | ND |

| AphaJ4C1 | 53.6 ± 2.1 | ND | 25.7 ± 1.5 | 20.7 ± 1.7 | ND | |

| AalkKphaGC1 | 15.0 ± 1.0 | 20.0 ± 1.9 | 47.8 ± 3.1 | 14.9 ± 2.2 | 2.3 ± 0.6 | |

| AR-PxylA | 57.4 ± 5.0 | ND | 19.9 ± 0.6 | 22.7 ± 1.0 | ND | |

| Axyl_phaJ4C1 | 56.8 ± 1.0 | ND | 20.6 ± 0.8 | 22.6 ± 1.1 | ND | |

| Axyl_ alkKphaGC1 | 10.2 ± 0.8 | 30.9 ± 1.8 | 41.2 ± 1.5 | 15.2 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | |

| APvan | Low N (65 mg/liter) | 44.2 ± 0.3 | 8.3 ± 1.0 | 20.2 ± 1.2 | 13.4 ± 2.0 | 13.9 ± 0.6 |

| AphaJ4C1 | 33.2 ± 0.5 | 11.9 ± 0.8 | 25.8 ± 2.3 | 12.1 ± 1.5 | 17.0 ± 1.0 | |

| AalkKphaGC1 | 17.0 ± 1.1 | 18.3 ± 1.0 | 34.1 ± 2.1 | 12.1 ± 2.9 | 18.5 ± 0.3 | |

| AR-PxylA | 45.4 ± 2.8 | 7.3 ± 0.2 | 16.6 ± 2.0 | 14.9 ± 0.7 | 15.8 ± 0.4 | |

| Axyl_phaJ4C1 | 32.5 ± 0.9 | 9.8 ± 0.9 | 24.7 ± 2.3 | 13.8 ± 1.2 | 19.2 ± 0.1 | |

| Axyl_ alkKphaGC1 | 16.0 ± 0.8 | 15.2 ± 2.6 | 32.8 ± 1.7 | 13.1 ± 0.4 | 22.9 ± 0.1 | |

Vanillic acid (15 mM) was used as the carbon source.

3HHx, 3-hydroxyhexanoate; 3HO, 3-hydroxyoctanoate; 3HD, 3-hydroxydecanoate; 3HDD, 3-hydroxydodecanoate; 3HTD, 3-hydroxytetradecanoate; ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

PHA are polyesters that are synthesized by microbes as storage materials and are substantially accumulated under conditions where fatty acids are employed as the feedstock, without the requirement of inorganic ion deprivation. However, the high cost of fatty acids hinders commercialization of PHA production. Therefore, lignin, a by-product generated in large volumes by lignocellulosic biorefineries, is the ideal substrate for PHA production. When lignin is utilized as a carbon source, PHA accumulation usually occurs under conditions of fluctuating nutrient availability due to its function as a carbon and energy storage molecule. However, this nutrition imbalance generally limits cell growth, which is a critical factor for the total PHA titer and thus represents one of the major hurdles in a consolidated lignin-to-PHA bioconversion scheme. Previous studies have reported strategies for heterologous PHA production without compromising cell biomass in E. coli, with either glucose or glycerol as the sole carbon source (6, 7, 31–33), but not, as yet, with lignin or its derivatives. This is probably due to E. coli's inability to degrade lignin, restricting it to glycerol or other carbohydrates. Therefore, testing and comparing the PHA synthetic pathways when lignin or its derivatives are provided as the main source of carbon may serve as an essential foundation for engineering these two traits in Pseudomonas species, organisms known to be capable of both lignin degradation and PHA accumulation.

First, our work extended molecular tools for Pseudomonas strains by identifying a xylose-inducible promoter, PxylA, which is specifically induced by xylose at a concentration (2 mM) that is sufficient to stimulate its activity without interfering with cell growth when a lignin derivative is utilized as the sole carbon source. Moreover, the adjacent xylose operon regulatory protein, XylR, was validated to stimulate its activity. Thus, XylR-PxylA might be superior for the control of strongly transcribed genes, complementary to an inducible weak promoter, Pvan (16, 34).

Second, our study unveiled unique features of the P. putida A514 mcl-PHA biosynthetic genes when this strain is grown on a lignin derivative. Comparison of low-N versus high-N conditions revealed that phaJ4 exhibited the highest induction (Fig. 1F). This contradicts the current notion that phaG, but not phaJ4, is significantly upregulated when P. putida KT2440 is grown with glycerol (6). The stress-induced phaJ4 gene should play an important role in PHA biosynthesis under low-N conditions, which is consistent with the result where Axyl_phaJ4C1 generated more mcl-PHA under low-N conditions than did AR_PxylA (Table 1). In addition, comparison of the expression levels of phaG and alkK to phaJ4 leads to the hypothesis that phaG and alkK not only have a role in PHA biosynthesis but are also likely to be essential in cell growth (Fig. 2). This hypothesis was validated by the experiment where Axyl_alkKphaGC1 coenhanced the PHA titer and cell growth under both low-N and high-N conditions (Table 1). Furthermore, total PHA titer reached the highest level (∼250 mg/liter) under high-N conditions, although the PHA content in Axyl_alkKphaGC1 was not the highest (∼35 wt% CDW), possibly a consequence of Axyl_alkKphaGC1 having the highest cell dry weight.

Third, the mcl-PHA, synthesized in Axyl_phaJ4C1 and Axyl_alkphaGC1, have a greater number of longer-chain monomers (Table 4). This phenotype may be ascribed to the functions of phaJ4, phaG, and alkK. phaJ4Pa in P. aeruginosa encodes an (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase that shows specificity for the hydration of longer-chain-length enoyl-CoAs (C6 to C12) (35). The higher contents of 3HO, 3HDD, and 3HTD in Axyl_phaJ4C1 cells under nitrogen deprivation indicated the homologous phaJ4 gene in A514 likely has greater preference for C8, C10, and C14 substrates. In addition, the function of PhaG (in P. putida KT2440) has been shown as a 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP thioesterase to produce 3-hydroxy fatty acids, while AlkK (in Pseudomonas oleovorans) is involved in catalyzing the conversion of 3-hydroxy fatty acids to the PHA precursor 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA (6, 28). The closest homolog in A514 to the AlkK gene is the gene encoding a long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase (PputA514_1839). Thus, the longer chain PHA monomers (C10 and C14) produced in Axyl_alkphaGC1 appear to be the result of alkK substrate specificity in A514. This is consistent with the previous report that the mcl-PHA synthesized in recombinant E. coli, carrying the vector to coexpress PhaG, PhaC1, and the medium-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase (AlkK-like protein in KT2440), mainly contain C8 and C10 (6).

Finally, compared to other studies on PHA biosynthesis from lignin or its derivatives, higher PHA production (246 mg/liter) and cell dry weights (715 mg/liter) were generated in batch cultivation (Table 5). Although a slightly higher PHA titer (252 mg/liter) was produced by P. putida KT2440 from alkaline pretreated liquor, it was obtained through fed-batch fermentation and high substrate concentrations (including those of glucose, acetate, coumaric acid, and ferulic acid) (3). Additionally, the monomeric composition and content of PHA produced by bacterial strains from lignin or its derivatives are very important, as they can greatly affect the properties of PHA copolymers (36). Both Cupriavidus basilensis B-8 and Pandoraea sp. strain ISTKB produce short-chain-length PHA (scl-PHA, C3 to C5), whereas the monomeric content of mcl-PHA generated by P. putida KT2440 from alkaline pretreated liquor was not reported (Table 5) (10, 37, 38). In contrast, longer-chain monomers produced by A514 in general and the large amount of longer monomers (e.g., 3HTD) synthesized by Axyl_alkphaGC1 in particular would have higher crystallinity and better tensile strength (36), which may endow mcl-PHA with novel mechanical properties and wider array of potential applications. This demonstrated that increasing the expression levels of phaG and alkK is a more efficient strategy to coenhance PHA titer and cell growth, and that P. putida Axyl_alkKphaGC1 is a very competitive strain for the production of PHA from lignin derivatives.

TABLE 5.

Comparison of the mcl-PHA or scl-PHA (PHB) production from lignin or its derivatives

| Strain | Carbon substrate | Cultivation mode | Cultivation time (h) | CDW (mg/liter) | mcl-PHAa titer (mg/liter) | scl-PHAb titer (mg/liter) | PHA content (wt%) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cupriavidus basilensis B-8 | 5 g/liter soluble lignin | Shake flask batch | 120 | 736 | NDc | 128 | 17 | 38 |

| Pandoraea sp. ISTKB | 2 g/liter vanillic acid | Shake flask batch | 96 | 215 | ND | 72 | 33 | 37 |

| P. putida JCM13063 | 10 g/liter vanillic acid | Shake flask batch | 72 | 210 | ND | trd | <1 | 10 |

| P. putida Gpo1 | 10 g/liter vanillic acid | Shake flask batch | 72 | 140 | ND | tr | <1 | 10 |

| P. putida KT2440 | 2 g/liter coumaric acid | Shake flask batch | 48 | 470 | 160 | ND | 34 | 3 |

| P. putida KT2440 | 2 g/liter ferulic acid | Shake flask batch | 48 | 436 | 170 | ND | 39 | 3 |

| P. putida Axyl_alkKphaGC1 | 2.5 g/liter vanillic acid | Shake flask batch | 50 | 715 | 246 | ND | 34 | This study |

| P. putida KT2440 | 90% alkaline-pretreated liquor | Fed-batch fermentation | 48 | 787 | 252 | ND | 32 | 3 |

mcl-PHA, medium-chain-length PHA.

scl-PHA, short-chain-length PHA.

ND, not determined.

tr, trace.

Conclusions.

In summary, this study revealed specific features of the PHA synthesis pathways for P. putida A514 when grown using a lignin derivative and demonstrated a rational strategy to coengineer cell growth and PHA production. As improvements in cell growth and bioproduct production are crucial and shared goals in the sustainable development of lignocellulosic biorefineries (11), our findings should be valuable not just to the production of PHA, but also to that of a wide variety of biofuels and biochemicals. Further genetic strategies, including optimization of the carbon flux either from de novo fatty acid biosynthesis or β-oxidation pathways to PHA synthesis (e.g., deletion, insertion, or substitution of the genes involved in fatty acid metabolism, global nitrogen regulation, and so on), and fermentation optimization at flask level or bioreactor level in the near future would further improve the PHA content in cells, which then could be integrated into lignin-consolidated bioprocessing to promote the production of bioproducts.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 3. E. coli DH5α was used for all molecular manipulations to construct plasmids. This strain was grown on Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. During recombinant plasmid construction, 15 μg/ml tetracycline was added to the medium. For P. putida A514 and cultivation of its recombinant strains, all strains were grown on LB agar for 24 h at 30°C. A single colony was inoculated into 5 ml of 15 mM vanillic acid-M9 mineral medium (with a high concentration NH4Cl [1 g/liter]) and grown at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm (39). When the stationary phase was reached, 0.2 ml of culture solution was transferred into 20 ml of fresh vanillic acid-M9 mineral medium with either high-concentration NH4Cl (1 g/liter) or low-concentration NH4Cl (65 mg/liter) at 30°C, 200 rpm, and passaged two times (with 1% [vol/vol] inoculation) under the same culture condition. Subsequently, 1% (vol/vol) of seed inoculum for shake flask cultivation was incubated in 100 ml of vanillic acid-M9 mineral medium with high-N or low-N conditions at 30°C and 200 rpm. Tetracycline (15 μg/ml) was added to the medium when culturing P. putida A514 recombinant strains. Cell growth was spectrophotometrically monitored by measuring the optical densities at 600 nm (OD600). For the cultivation of strains AR-PxylA, Axyl_phaJ4C1, and Axyl_alkKphaGC1, xylose was introduced to a final concentration of 2 mM when the OD600 was either ∼0.78 (in the high-nitrogen culture medium) or ∼0.22 (in the low-nitrogen culture medium). The doubling times (DT) of all the strains were calculated during the exponential phase, based on the formula DT = t · [log 2/(log Nt − log N0)], where t = duration, Nt = final cell concentration, and N0 = initial cell concentration. To determine the number of living cells of N0 and Nt, 100 μl of fermentation culture was serially diluted and plated on LB agar plates. CFU/ml was assessed as cell concentration. All of the experiments were performed in biological triplicate and technical duplicate.

Determination of gene transcription levels by qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR was performed as previously described (40). Briefly, a total volume of 10 ml of P. putida A514 cell culture was harvested from either high-nitrogen (OD600, ∼0.78) or low-nitrogen (OD600, ∼0.22) culture medium during the mid-exponential phase. The total RNA was isolated using a TransZol Up Plus RNA kit (Transgen Biotech). cDNA libraries were synthesized with a TransScript one-step genomic DNA (gDNA) removal and cDNA synthesis supermix kit (Transgen Biotech), employing 0.5 μg of total RNA as the template for each sample. The qRT-PCRs were performed using the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II kit (TaKaRa) with the real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems VII A7). The primers used in qRT-PCR are listed in Table 2. Gene expression levels were assessed by comparing the ratios of the housekeeping gene rpoD (PputA514_4978, encoding the housekeeping σ70 factor) threshold cycle (CT) values to target gene CT values using the following equation: ratio of rpoD/target = 2CT(rpoD) − CT(target) (6). The n-fold induction was determined by the expression levels of the genes of cells grown on low-N M9 medium versus those of cells grown on high-N M9 medium. All of the samples were prepared and analyzed in biological triplicate and technical duplicate.

Plasmid and strain construction.

A 315-bp PCR fragment containing the promoter fragment of the vanAB genes (encoding vanillate demethylase A and vanillate O-demethylase oxidoreductase in the vanillic acid degradation pathway), Pvan, was amplified from P. putida A514 genomic DNA and subsequently ligated into the plasmid pPROBE-TT (29) through HindIII and EcoRI, to generate the plasmid pPvan. pPvan was used as the expression vector for coexpression of PHA synthesis genes. The putative 3-hydroxyacyl-ACP thioesterase gene (phaG, PputA514_1318), long-chain fatty acid-CoA ligase gene (alkK, PputA514_1839), enoyl-CoA hydratase gene (phaJ4, PputA514_4767), and poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) polymerase 1 gene (phaC1, PputA514_5834) were amplified by PCR from the genome of A514. These three DNA fragments (phaG, alkK, and Pvan) were fused by gene splicing by overlap extension (SOE) PCR to produce a 2.8-kb PCR fragment, whereas the DNA fragments of phaJ4 and Pvan were fused to produce a 0.78-kb PCR fragment. The two overlap PCR fragments were digested with HindIII and KpnI, respectively, while the phaC1 fragment was digested with KpnI and EcoRI. DNA fragments containing Pvan, phaG, alkK, and phaC1 were cloned into the pPROBE-TT to construct plasmid pTphaGC1. Similarly, DNA fragments containing Pvan, phaJ4, and phaC1 were cloned into the pPROBE-TT to construct the pTJ4C1 vector (Table 3).

For the inducible promoter investigation, a chromosomal fragment comprising the 140-bp xylR-xylA intergenic region was PCR amplified and cloned into the plasmid pPROBE-TT through HindIII and XbaI, generating the pTPxylA vector (29). To construct pTRPxylA, a genomic fragment containing the ORF region of xylR and the xylR-xylA intergenic region was PCR amplified, digested by HindIII and XbaI, and then ligated into the pPROBE-TT (Table 3).

The plasmid pTRPxylA was used as the expression vector to coexpress the PHA synthesis genes. A DNA fragment containing phaC1 and either phaG and alkK or phaJ4 was amplified and cloned into pTRPxylA to construct pTPxylAphaGC1 and pTPxylAphaJ4C1, respectively (Table 3).

All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing and were subsequently transformed into A514 cells through chemical transformation (41), followed by selection on LB agar supplemented with 15 μg/ml tetracycline.

Green fluorescence signal detection.

Cells from 15 mM vanillic acid-M9 medium cultures were harvested, centrifuged, washed once with 10 mM phosphate buffer, and then resuspended in phosphate buffer. Fluorescence was measured on an LS50B luminescence spectrometer (PerkinElmer Instruments, Norwalk, CT) at an excitation wavelength of 490 nm, an emission wavelength of 510 nm, and emission/excitation slit widths of 8 nm. Intensity readings are represented by arbitrary units and were normalized to a cell density of 106 CFU/ml. All of the experiments were performed in biological triplicate and technical duplicate.

Analytical procedures.

To measure the concentration of vanillic acid in the medium, 1-ml cell samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g, and the concentration of vanillic acid in the supernatant was measured via absorbance at 289 nm, as previously described (16). For PHA production analysis, PHA biosynthesis and monomer compositions were analyzed by gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (GC-MS/MS; Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). PHA titer was defined as the PHA concentration (mg) per one liter of shake flask batch culture, while PHA content was defined as the percentage of PHA concentration (mg) to cell dry weight (mg). Liquid cultures (100 ml) were harvested at the stationary phase and centrifuged at 9,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, washed twice with 15 ml Nanopure water, lyophilized (Lyophilizer Alpha 1-4 LSC; Martin Christ Gefriertrocknungsanlagen GmbH, Osterode am Harz, Germany) at −59°C and 0.140 × 105 mPa for a minimum of 24 h, and weighed. The lyophilized cells were dissolved in 2 ml of methanol-sulfuric acid (85:15) solution and 2 ml chloroform (containing a final concentration of 0.01 mg/ml 3-methylbenzoic acid as the internal standard) and then incubated at 100°C for 4 h to methanolysis. After cooling, 1 ml of demineralized water was added to the organic phase, which contained the resulting methyl esters of monomers. The organic phase was filtered and analyzed by GC-MS/MS (Agilent series 7890B GC system; Santa Clara, CA), coupled with a 7000D MS detector (extractor ion [EI]; 70 eV). An aliquot (1 μl) of the organic phase, which was properly diluted, was injected into the gas chromatography column. Separation of compounds was achieved using an HP-5 capillary column (5% phenyl-95% methyl siloxane, 30 m by 0.32-mm inside diameter [i.d.] by 0.25-μm film thickness). Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.1 ml/min. The injector and transfer line temperatures were set at 280°C and 300°C, respectively. The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature of 60°C for 3 min, then from 60°C to 200°C at a rate of 5°C per min, then 200°C for 1 min, and finally from 200°C to 280°C a rate of 15°C per min. The EI mass spectrum was recorded in full scan mode (m/z 40 to 550). PHA standard samples (3HHx, 3HO, 3HD, 3HDD, and 3HTD), which were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Larodan, and TRC, were also analyzed by GC-MS/MS according to the method above. The retention time (RT), patterns of fragment ion peaks for known PHA standards, and resulting mass spectra available compared with the GC-MS library database (NIST08s) were all employed to determine the PHA monomers in the study samples (7, 23). All of the experiments were performed in biological triplicate and technical duplicate. Differences between groups (including cell dry weight, vanillic acid concentration, and PHA titer) were evaluated using two-tailed unpaired t tests. Those with P values of <0.05 are considered significant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 41606154 from the NSF of China; grant LMB17011002 from the Open Funding of Key Laboratory of Tropical Marine Bio-resources and Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; grant HY201704 from the Open Funding of Key Laboratory of Marine Biogenetic Resources, Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration; and grant SKYAM002-2016 from the State Key Laboratory of Applied Microbiology Southern China, Guangdong Institute of Microbiology. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

L.L. conceived and designed the experiments. L.L. and X.W. performed the experiments. L.L. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. J.D., J.L., W.W., H.W., Z.Z., and X.Y. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01469-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang Y, Yin J, Chen GQ. 2014. Polyhydroxyalkanoates, challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Biotechnol 30:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang J, Shishatskaya EI, Volova TG, da Silva LF, Chen GQ. 2018. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) for therapeutic applications. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl 86:144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linger JG, Vardon DR, Guarnieri MT, Karp EM, Hunsinger GB, Franden MA, Johnson CW, Chupka G, Strathmann TJ, Pienkos PT, Beckham GT. 2014. Lignin valorization through integrated biological funneling and chemical catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:12013–12018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410657111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen GQ, Hajnal I, Wu H, Lv L, Ye J. 2015. Engineering biosynthesis mechanisms for diversifying polyhydroxyalkanoates. Trends Biotechnol 33:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langenbach S, Rehm BH, Steinbuchel A. 1997. Functional expression of the PHA synthase gene phaC1 from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Escherichia coli results in poly(3-hydroxyalkanoate) synthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 150:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Q, Tappel RC, Zhu C, Nomura CT. 2012. Development of a new strategy for production of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoates by recombinant Escherichia coli via inexpensive non-fatty acid feedstocks. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:519–527. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07020-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhuang QQ, Wang Q, Liang QF, Qi QS. 2014. Synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates from glucose that contain medium-chain-length monomers via the reversed fatty acid beta-oxidation cycle in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng 24:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burniol-Figols A, Varrone C, Le SB, Daugaard AE, Skiadas IV, Gavala HN. 2018. Combined polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) and 1,3-propanediol production from crude glycerol: selective conversion of volatile fatty acids into PHA by mixed microbial consortia. Water Res 136:180–191. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin L, Xu J. 2013. Dissecting and engineering metabolic and regulatory networks of thermophilic bacteria for biofuel production. Biotechnol Adv 31:827–837. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomizawa S, Chuah J-A, Matsumoto K, Doi Y, Numata K. 2014. Understanding the limitations in the biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) from lignin derivatives. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 2:1106–1113. doi: 10.1021/sc500066f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ragauskas AJ, Beckham GT, Biddy MJ, Chandra R, Chen F, Davis MF, Davison BH, Dixon RA, Gilna P, Keller M, Langan P, Naskar AK, Saddler JN, Tschaplinski TJ, Tuskan GA, Wyman CE. 2014. Lignin valorization: improving lignin processing in the biorefinery. Science 344:1246843. doi: 10.1126/science.1246843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyman CE. 2007. What is (and is not) vital to advancing cellulosic ethanol. Trends Biotechnol 25:153–157. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao X, Chen J-C, Wu Q, Chen G-Q. 2011. Polyhydroxyalkanoates as a source of chemicals, polymers, and biofuels. Curr Opin Biotechnol 22:768–774. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salvachua D, Karp EM, Nimlos CT, Vardon DR, Beckham GT. 2015. Towards lignin consolidated bioprocessing: simultaneous lignin depolymerization and product generation by bacteria. Green Chem 17:4951–4967. doi: 10.1039/C5GC01165E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numata K, Morisaki K. 2015. Screening of marine bacteria to synthesize polyhydroxyalkanoate from lignin: contribution of lignin derivatives to biosynthesis by Oceanimonas doudoroffii. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng 3:569–573. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin L, Cheng Y, Pu Y, Sun S, Li X, Jin M, Pierson EA, Gross DC, Dale BE, Dai SY, Ragauskas AJ, Yuan JS. 2016. Systems biology-guided biodesign of consolidated lignin conversion. Green Chem 18:5536–5547. doi: 10.1039/C6GC01131D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Prieto MA, Eugenio LId, Galàn B, Luengo JM, Witholt B. 2007. Synthesis and degradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates, p 397–428. In Ramos J-L, Filloux A (ed), Pseudomonas: a model system in biology. Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, the Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bugg TD, Ahmad M, Hardiman EM, Singh R. 2011. The emerging role for bacteria in lignin degradation and bio-product formation. Curr Opin Biotechnol 22:394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rahmanpour R, Bugg TD. 2015. Characterisation of Dyp-type peroxidases from Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf-5: oxidation of Mn(II) and polymeric lignin by Dyp1B. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 574:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Gonzalo G, Colpa DI, Habib MH, Fraaije MW. 2016. Bacterial enzymes involved in lignin degradation. J Biotechnol 236:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos A, Mendes S, Brissos V, Martins LO. 2014. New dye-decolorizing peroxidases from Bacillus subtilis and Pseudomonas putida MET94: towards biotechnological applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:2053–2065. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5041-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nikel PI, Martinez-Garcia E, de Lorenzo V. 2014. Biotechnological domestication of Pseudomonads using synthetic biology. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:368–379. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nikodinovic-Runic J, Flanagan M, Hume AR, Cagney G, O'Connor KE. 2009. Analysis of the Pseudomonas putida CA-3 proteome during growth on styrene under nitrogen-limiting and non-limiting conditions. Microbiology 155:3348–3361. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.031153-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moita R, Freches A, Lemos PC. 2014. Crude glycerol as feedstock for polyhydroxyalkanoates production by mixed microbial cultures. Water Res 58:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Q, Nomura CT. 2010. Monitoring differences in gene expression levels and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 grown on different carbon sources. J Biosci Bioeng 110:653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poblete-Castro I, Escapa IF, Jager C, Puchalka J, Lam CM, Schomburg D, Prieto MA, Martins dos Santos VA. 2012. The metabolic response of P. putida KT2442 producing high levels of polyhydroxyalkanoate under single- and multiple-nutrient-limited growth: highlights from a multi-level omics approach. Microb Cell Fact 11:34. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ryan WJ, O'Leary ND, O'Mahony M, Dobson AD. 2013. GacS-dependent regulation of polyhydroxyalkanoate synthesis in Pseudomonas putida CA-3. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1795–1802. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02962-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satoh Y, Murakami F, Tajima K, Munekata M. 2005. Enzymatic synthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-4-hydroxybutyrate) with CoA recycling using polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and acyl-CoA synthetase. J Biosci Bioeng 99:508–511. doi: 10.1263/jbb.99.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller WG, Leveau JH, Lindow SE. 2000. Improved gfp and inaZ broad-host-range promoter-probe vectors. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 13:1243–1250. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.11.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Jong A, Pietersma H, Cordes M, Kuipers OP, Kok J. 2012. PePPER: a webserver for prediction of prokaryote promoter elements and regulons. BMC Genomics 13:299. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong YK, Show PL, Ooi CW, Ling TC, Lan JC. 2014. Current trends in polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) biosynthesis: insights from the recombinant Escherichia coli. J Biotechnol 180:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freches A, Lemos PC. 2017. Microbial selection strategies for polyhydroxyalkanoates production from crude glycerol: effect of OLR and cycle length. N Biotechnol 39(Part A):22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, Fan Z, Jiang X, Chen J, Chen GQ. 2016. Enhanced production of polyhydroxybutyrate by multiple dividing E. coli. Microb Cell Fact 15:128. doi: 10.1186/s12934-016-0415-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thanbichler M, Iniesta AA, Shapiro L. 2007. A comprehensive set of plasmids for vanillate- and xylose-inducible gene expression in Caulobacter crescentus. Nucleic Acids Res 35:e137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuge T, Taguchi K, Seiichi T, Doi Y. 2003. Molecular characterization and properties of (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: metabolic tools for synthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates via fatty acid beta-oxidation. Int J Biol Macromol 31:195–205. doi: 10.1016/S0141-8130(02)00082-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu W, Chen GQ. 2007. Production and characterization of medium-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoate with high 3-hydroxytetradecanoate monomer content by fadB and fadA knockout mutant of Pseudomonas putida KT2442. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:1153–1159. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar M, Singhal A, Verma PK, Thakur IS. 2017. Production and characterization of polyhydroxyalkanoate from lignin derivatives by Pandoraea sp. ISTKB 2:9156–9163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi Y, Yan X, Li Q, Wang X, Liu M, Xie S, Chai L, Yuan J. 2017. Directed bioconversion of Kraft lignin to polyhydroxyalkanoate by Cupriavidus basilensis B-8 without any pretreatment. Process Biochem 52:238–242. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauchop T, Elsden SR. 1960. The growth of micro-organisms in relation to their energy supply. J Gen Microbiol 23:457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin L, Song H, Tu Q, Qin Y, Zhou A, Liu W, He Z, Zhou J, Xu J. 2011. The Thermoanaerobacter glycobiome reveals mechanisms of pentose and hexose co-utilization in bacteria. PLoS Genet 7:e1002318. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mercer AA, Loutit JS. 1979. Transformation and transfection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effects of metal ions. J Bacteriol 140:37–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.