Abstract

Mother of FT and TFL1 (MFT) belongs to phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein (PEBP) family, which plays an important role in flowering time regulation, seed development, and germination. To gain insight into the molecular function of DlMFT in Dimocarpus longan Lour., we isolated DlMFT and its promoter sequence from longan embryogenic callus (EC). Bioinformatic analysis indicated that the promoter contained multiphytohormones and light responsive regulatory elements. Subcellular localization showed that the given the DlMFT signal localized in the nucleus, expression profiling implied that DlMFT showed significant upregulation during somatic embryogenesis (SE) and zygotic embryogenesis (ZE), and particular highly expressed in late or maturation stages. The accumulation of DlMFT was mainly detected in mature fruit and seed, while it was undetected in abortive seeds, and notably decreased during seed germination. DlMFT responded differentially to exogenous hormones in longan EC. Auxins, salicylic acid (SA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJa) suppressed its expression, however, abscisic acid (ABA), brassinosteroids (BR) showed the opposite function. Meanwhile, DlMFT differentially responded to various abiotic stresses. Our study revealed that DlMFT might be a key regulator of longan somatic and zygotic embryo development, and in seed germination, it is involved in complex plant hormones and abiotic stress signaling pathways.

Keywords: mother of FT and TFL1, longan, embryogenesis, phytohormones, stress response, quantitative real-time PCR

1. Introduction

Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) is a famous subtropical economic fruit tree in Southeast Asia. Embryogenesis is an important factor associated with fruit output quantity and quality in longan [1]. However, elucidating these mechanisms remains a challenge due to the limitations in accessibility of embryos in vivo [2]. In previous research, longan somatic embryogenesis (SE) was widely used as a model system to study the early development process of woody plants, especially their embryogenesis [1,3,4,5,6]. During plant SE, somatic cells undergo a series of morphological and biochemical changes and then differentiate into somatic embryos [7,8]. The development of SE closely resembles that of zygotic embryogenesis (ZE), it has been considered as a potential model for studying early events in plant embryo development [7], and considered as a model to study the tissular, cellular, and molecular properties of ZE [9,10].

The plant phosphatidylethanolamine binding protein (PEBP) family was divided into three main clades, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)-like, TERMINAL FLOWER1 (TFL1)-like, and MFT-like [11,12,13,14]. MFT-like clade seems to be the phylogenetically ancestral to other clades [11,15,16]. FT and TFL1 are two regulators with antagonistic functions in controlling flowering time and plant architecture, FT acts as the floral activator, but TFL1 acts as inhibitor [14,17,18,19]. Interestingly, swapping the single amino acid residues (His88/Asp144 in TFL1, Tyr85/Gln140 in FT) causes conversion of FT to TFL1 and vice versa [20]. Although the sequence of MFT shows high similarity to both FT and TFL1, the function of MFT in controlling flowering time might be different from FT/TFL1. Overexpression of MFT in Arabidopsis caused slightly early flowering under long days, but its function in determination of flowering time was redundant [21], whereas PopMFT did not identify a function in controlling flowering time [21,22]. Identification of a major QTL (quantitative trait loci) in Arabidopsis indicates MFT was a potential candidate gene for altered flowering time at an increased atmospheric (CO2) [23].

The expression pattern of MFT in several plants were very similar; Arabidopsis thaliana MFT [24], Vitis vinifera MFT [13], Populus nigra MFT [14], Citrus unshiu MFT [25], Zea mays MFT [26], Triticum aestivum MFT [27], Jatropha curcas MFT [28], Glycine max MFT [29] and Hevea brasiliensis MFT1 [30] were mainly expressed in mature fruits or seeds. However, Gossypium hirsutum MFT1 and MFT2 were mainly expressed in flowers and low-transcribed in other tissues [31]. SrMFT were constitutively expressed in various tissues and developmental stages in Symplocarpus renifolius, although the expression of SrMFT in female-stage spadices was higher than in other stages, whereas overexpression SrMFT in Arabidopsis did not show the function in earlier flowering [32]. In addition, the expression of AcMFT showed a distinct decrease from the young frond stage to the sori development and maturation stages, and was regulated by photoperiod in Adiantum capillus-veneris, introduced AcMFT in Arabidopsis promoted flowering [33]. In Arabidopsis, MFT promoted embryonic growth during seed germination by directly repressing ABI5 expression, it played a critical role in seed germination via a negative regulation of abscisic acid (ABA) signaling pathway [24], it also promoted fertility relevant to the brassinosteroid (BR) signaling pathway [34]. Meanwhile, MFT promoted primary dormancy during seed development, and enhanced germination in after-ripened imbibed seeds with exogenous ABA in Arabidopsis [35]. Conversely, TaMFT, an MFT homolog in wheat (Triticum aestivum) acted as a positive regulator of seed dormancy, while a negative regulator of seed germination [27]. The homolog of MFT in soybean responded to exogenous applied ABA and gibberellin (GA), ectopic expression of GmMFT in Arabidopsis did not affect the flowering time but suppressed seed germination [29]. Ectopic expression of HbMFT1 in Arabidopsis inhibited seed germination, seedling growth, different with previous studies, it delayed flowering time [30]. FvMFT located in the nucleus and cytoplasmic membranes, ectopic expression of FvMFT in Arabidopsis also inhibited seed germination through integrating ABA and GA signaling, FvMFT could notably promote the primary root growth under sugar-deficient conditions [36].

At present, the expression profile of MFT during SE and ZE, and its signaling pathways involved in the response to hormones and environmental cues in embryogenic calli are still fragmented. In addition, the function of MFT homolog in longan has not been investigated. In our study, we isolated DlMFT and its promoter, and found that DlMFT was a seed-specific gene, and might play an important role in longan embryogenesis, seed development, and germination. DlMFT also involved in complex hormones and stress responses. The information provided by our study may help to illuminate the biological functions of DlMFT in longan.

2. Results

2.1. Isolation of DlMFT and Its Phylogenetic Analysis

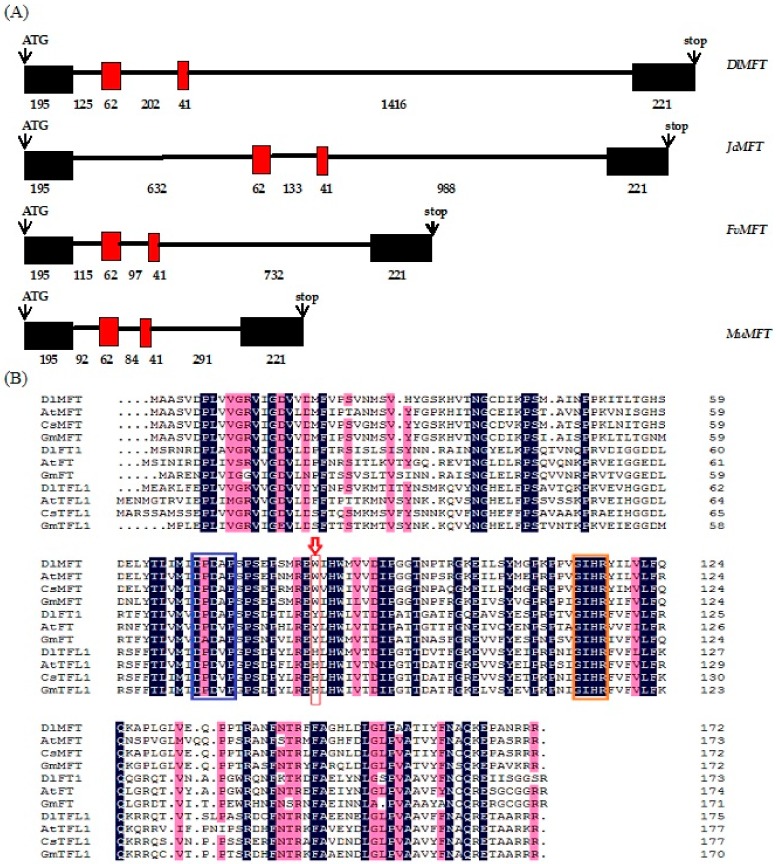

The RT-PCR (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction) combined with RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) strategy was used to obtain the complete cDNA (complementary DNA) and gDNA (genomic DNA) sequences of DlMFT from embryogenic callus of Dimocarpus longan. The amplified 866 bp region of DlMFT cDNA contained a 519 bp protein coding sequence flanked by a 54 bp 5′-untranslated region and a 312 bp 3′-untranslated region (GenBank accession No. KP861622). The gDNA sequence of DlMFT was cloned from longan EC DAN with specific primer and submitted to GenBank (GenBank accession No. KY968646), the comparative analysis of MFT genomic organization indicated that the MFT contained three introns and four exons, and owned the same number of nucleotides in exons (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(A) Genomic organization analysis of MFT in plants. Coding regions (boxes) and introns (lines) are illustrated. Numbers represent the length of exons and introns (bp). (B) Multiple alignment of the PEBP proteins isolated from Dimocarpus longan (DlMFT, AKM77640.1; DlTFL1, AHZ89714.1; DlFT1, AHF27443.1), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtFT, AAF03936.1; AtMFT, AEE29676.1; AtTFL1,P93003.1), Citrus sinensis (CsMFT, XP_006490744.1; CsTFL1, BAH28255.1), Glycine max (GmFT, BAJ33494.1; GmMFT, AJF40168.1; GmTFL1, ACU00123.1), Litchi chinensis (LcFT, AEU08965.1). The red arrow indicates the critical amino acids distinguishing TFL1, FT, and MFT. Boxes indicate the highly conserved DPDxP and GIHR motifs. The background color represents the similarity of the PEBP proteins, the blue frame represents the DPDxP motif, the orange color represent the GIHR motif, the red arrow represent the key residues of PEBP proteins.

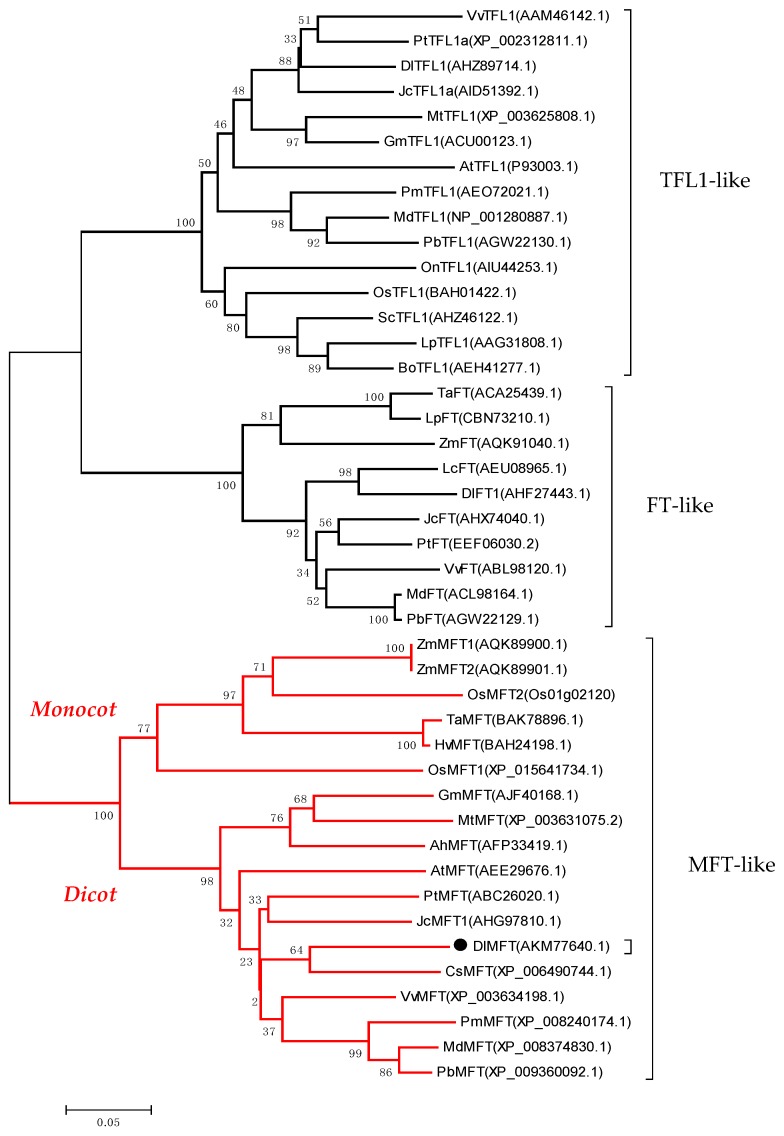

The DlMFT protein sequence shows 79%, 85%, and 86% identity with Arabidopsis MFT, Malus domestica MFT and Citrus clementina MFT, respectively (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Two highly conserved DPDxP and GIHR motifs between the PEBP families were identified (Figure 1b). In Arabidopsis, the key residues Y (Tyr-85) and H (His-88) were possibly the most critical for distinguishing FT and TFL1 function on flowering regulation [12,13,37]. However, the key residue in DlMFT was W (Trp-83), leading to the hypothesis that DlMFT does not play a central role in flowering time regulation. A phylogenetic tree for the PEBP family was constructed using several amino acid sequences of other MFT orthologs (Figure 2). The PEBP family was divided into three clades: FT-like, TFL1-like and MFT-like, and DlMFT belonged to the eudicots group of the MFT clade and had the closest relationship with CsMFT from Citrus sinensis.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic tree of the PEPB proteins from plant. The number at the nodes represents the reliability percent of bootstraps values based on 1000 replications (%). The sequences are from Dimocarpus longan (DlMFT, AKM77640.1; DlTFL1, AHZ89714.1; DlFT1, AHF27443.1), Vitis vinifera (VvMFT, XP_003634198.1; VvTFL1, AAM46142.1; VvFT, ABL98120.1), Zea mays (ZmMFT1, AQK89900.1; ZmMFT2, AQK89901.1; ZmFT, AQK91040.1), Oryza sativa (OsMFT1, Os06g30370; OsMFT2, Os01g02120; OsTFL1, BAH01422.1), Triticum aestivum (TaMFT, BAK78908; TaFT, ACA25439.1), Hordeum vulgare (HvMFT, BAH24198), Glycine max (GmMFT, AJF40168.1; GmTFL1, ACU00123.1), Medicago truncatula (MtMFT, XP_003631075.2; MtTFL1, XP_003625808.1), Arabidopsis thaliana (AtMFT, AEE29676.1; AtTFL1,P93003.1), Citrus sinensis (CsMFT, XP_006490744.1), Jatropha curcas (JcMFT1, AHG97810.1; JcTFL1a, AID51392.1; JcFT, AHX74040.1), Populus trichocarpa (PtMFT, ABC26020.1; PtTFL1a, XP_002312811.1; PtFT, EEF06030.2), Prunus mume (PmMFT, XP_008240174.1; PmTFL1, AEO72021.1), Malus domestica (MdMFT, XP_008374830.1; MdTFL1, NP_001280887.1; MdFT, ACL98164.1), Pyrus x bretschneideri (PbMFT, XP_008374830.1; PbTFL1, AGW22130.1; PbFT, AGW22129.1), Arachis hypogaea (AhMFT, AFP33419.1), Oncidium (OnTFL1, AIU44253.1), Saccharum (ScTFL1, AHZ46122.1), Lolium perenne (LpTFL1, AAG31808.1; LpFT, CBN73210.1), Bambusa oldhamii (BoTFL1, AEH41277.1), Litchi chinensis (LcFT, AEU08965.1).

2.2. Isolation and Functional Analysis of the DlMFT Promoter

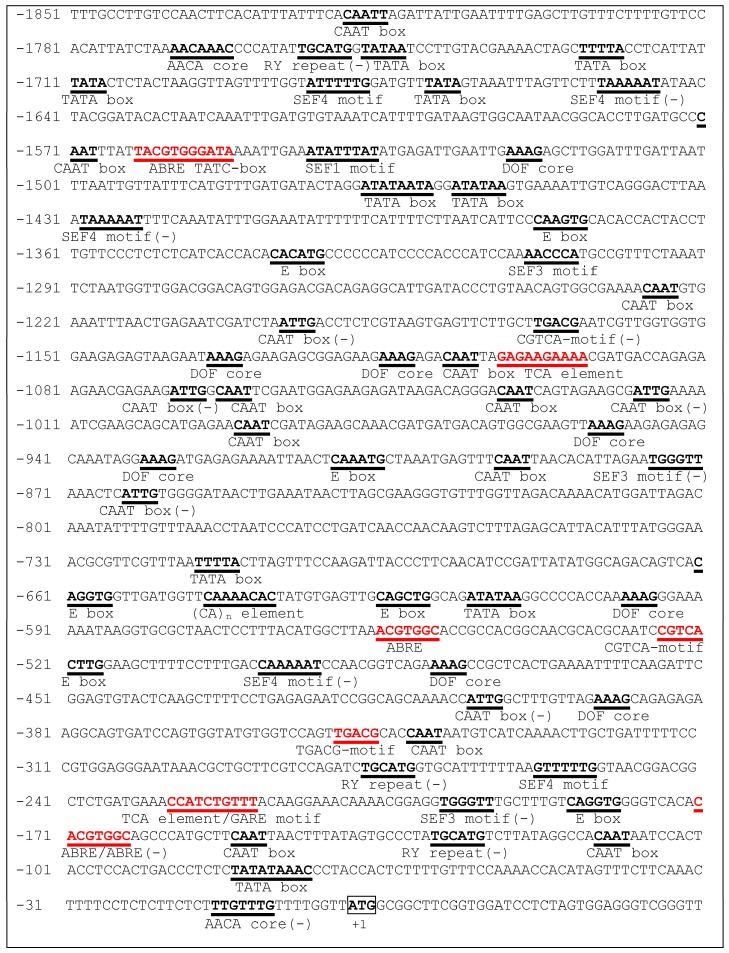

Base on the gDNA sequence, a 1.85-kb DlMFT promoter fragment (GenBank accession No. KY860780) was isolated from embryogenic callus gDNA by genome walking. The PLACE database was used to analysis the putative cis-acting elements in this promoter, and the sequences on both strands were considered. The putative regulatory elements are show in Figure 3. The DlMFT promoter contained multiple regulatory elements, including the AACA core (AACAAAC), (CA)n element (CNAACAC), DOF core (AAAG), E box (CANNTG), RY repeat (CATGCA) and SEF1, SEF3, SEF4 motifs (1, ATATTTAWW; 3, AACCCA; 4, RTTTTTR), which were involved in seed-specific transcriptional regulation [28]. Meanwhile, the putative cis-acting elements was performed using the PlantCARE database, the promoter contains multiple regulatory elements in response to hormone signals, including five ABRE for ABA responsiveness, three CGTCA-motif/TGACG-motif for MeJa responsiveness, two TCA-element for SA responsiveness, TATC-box and GARE-motif for GA responsiveness. Therefore, the analysis results suggested that DlMFT may be regulated by ABA, GA3, SA and MeJa. Furthermore, there were 22 light-responsiveness elements, including GT1-motif (3), SP1 (3), GA-motif (3), GAG-motif (3), Box-I (2), G-box (2), ACE (1), AE-box (1), ATCT-motif (1), GATA-motif (1), I-box (1), and TCT-motif (1).

Figure 3.

The nucleotide sequence of the DlMFT promoter. The A of the ATG (bold and boxed) is numbered as +1. The putative regulatory elements on both strands are shown in bold and underlined, the red colors indicate the hormone-responsive elements, which was performed by PlantCARE database.

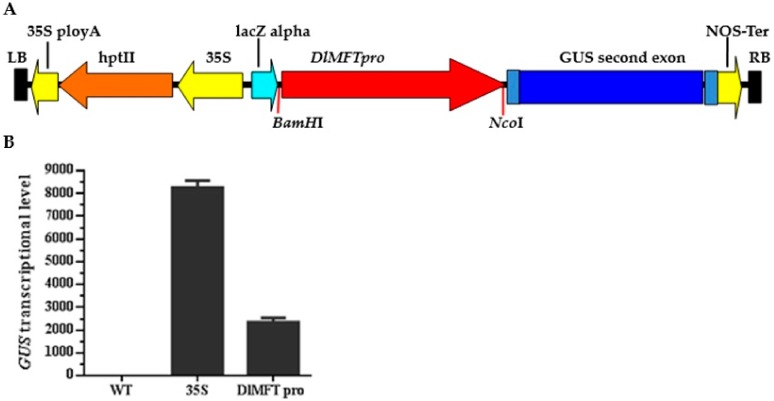

The DlMFT pro:GUS fusion (Figure 4) was constructed for transformation in N. Benthamiana. Transient transformation of DlMFT pro:GUS in Benthamiana indicated that DlMFT promoter could generate the expression of GUS, and the activation of DlMFT promoter was 28.4% lower than 35S promoter. These suggested that the DlMFT promoter can be used for further studies.

Figure 4.

GUS transcriptional level generated by 35S promoter and DlMFT promoter in N. benthamiana (Reference gene NbEF1a). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). (A) Schematic diagram of the expression frame in DlMFT pro:GUS vector. (B) The relative expression of GUS.

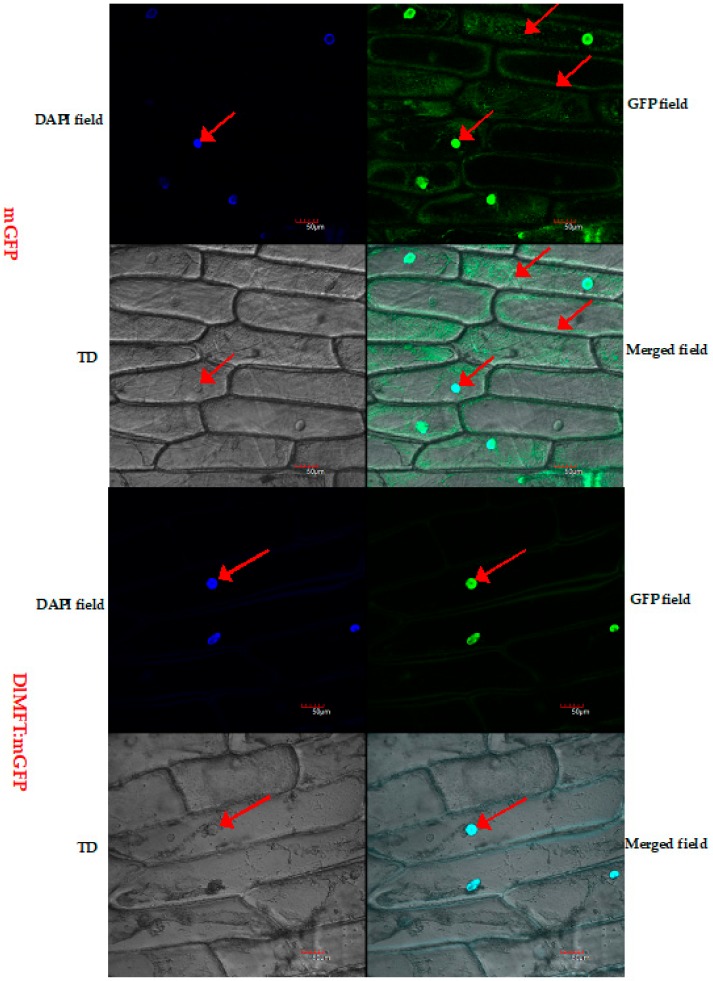

2.3. Subcellular Localization of DlMFT

The subcellular localization of DlMFT:mGFP was examined through a transient expression of DlMFT:mGFP in onion (Allium cepa) scale leaf epidermis cells, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI) was used as a maker of nuclear localization. As shown in Figure 5, the green fluorescent signal of DlMFT:mGFP fusion protein was localized in the nucleus, while the GFP associated with positive control was dispersed throughout the cells. After DAPI staining, the blue fluorescent signal of DlMFT:mGFP and positive control all targeted to the nucleus. The result indicated that DlMFT was distributed in the nucleus.

Figure 5.

Subcellular localization of DlMFT. Transient expression of DlMFT:mGFP via agroinfiltration in onion (Allium cepa) scale leaf epidermis cells; the upper image is GFP fluorescence of mGFP (pCAMBIA1302), the lower image is GFP fluorescence of DlMFT:mGFP in scale leaf epidermis cells. TD, transmitted light channel, referring to the transmitted light differential interference contrast images of the cells. Bars = 50 μm. The arrow indicated that DlMFT was located in the nucleus. The green fluorescence was the GFP file, the deep blue fluorescence was the DAPI file, the light blue fluorescence was the Merged file.

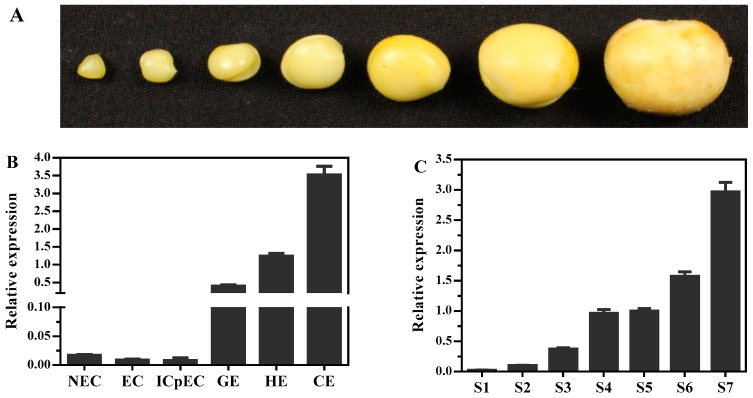

2.4. DlMFT Played a Key Role during Longan SE and ZE, and Seed Germination

To better understand the transcription regulation of DlMFT during longan embryogenesis, its transcription profiles were analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) during SE and ZE (Figure 7). As shown in Figure 7B, DlMFT was minimally expressed in non-embryogenic callus (NEC), embryogenic callus (EC) and incomplete compact pro-embryogenic cultures (ICpEC), but highly expressed in latter stages, and showed continuous up-regulation from ICpEC stage to cotyledonary embryos (CE) stages, and peaked at CE stage. Meanwhile, DlMFT mRNA was detected in all examined zygotic embryo development stages of ‘Honghezi’ longan (Figure 7A,C), its expression level was very low in S1 and S2 stages, and continuously increased during the embryo development stages, and showed a peak in mature zygotic embryo stage (S7). The results showed that DlMFT exhibited a similar expression pattern during longan SE and ZE, the expression profile implied a promotion role of DlMFT during longan SE and ZE, especially, at the late embryogenesis stages.

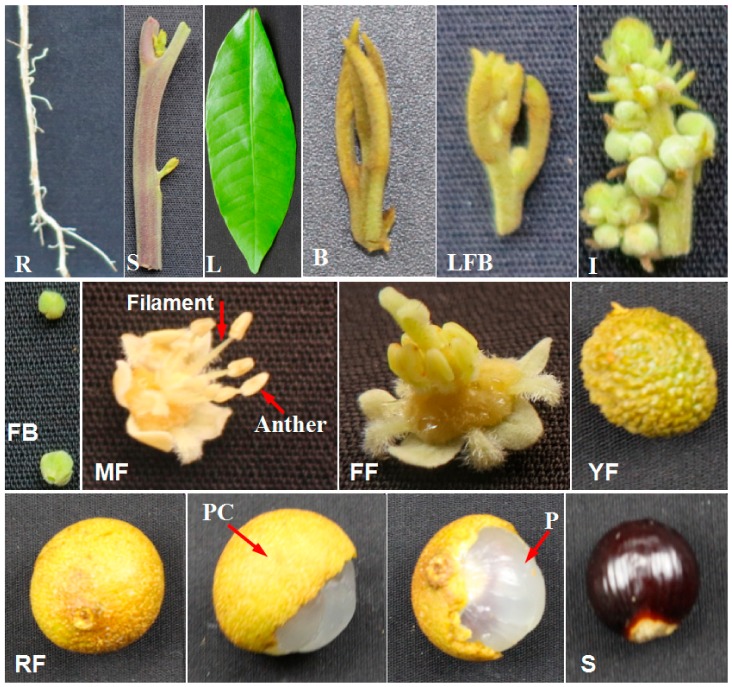

To gain insight into the expression profile of DlMFT in longan, we examined the levels of DlMFT transcript in different tissues, including roots, stems, leaves, vegetative buds, floral buds, inflorescence, flower buds, male flowers, filaments, anthers, female flowers, young fruits, ripe fruits, pericarp, pulp and seeds of ‘Honghezi’ longan (Figure 6); and the roots, leaves, flower buds, flowers, young fruits, ripe fruits, pericarp, pulp and seeds of ‘Sijimi’ longan. In ‘Honghezi’ longan (Figure 7F), DlMFT was highly expressed in the ripe fruits and seeds, however, it was minimal or undetected in other tissues, including the pericarp and pulp. Similarly, DlMFT also showed the ripe fruits and seeds specific in ‘Sijimi’ longan (Figure 7D), which revealed that DlMFT was a seed-specific gene. Furthermore, we harvested the normal and abortive seeds from their ripe fruits of different species at the same days (100 day) after flowering, and checked the expression of DlMFT in these seeds. The result showed that DlMFT was highly expressed in normal development seeds, but was undetected in abortive seeds of ‘Quanlong baihe’ longan (Figure 7E). Hence, we concluded that DlMFT played an important role in controlling the embryo and seed development.

Figure 6.

Different tissues of ‘Honghezi’ longan. R (root), S (stem), L (leaf), B (vegetative bud), LFB (late stage of floral bud), I (inflorescence), FB (flower bud), MF (male flower), FF (female flower), YF (young fruit), RF (ripe fruit), PC (pericarp), P (pulp), and S (seed).

Figure 7.

The expressions profile of DlMFT at different tissues and during longan embryogenesis. R: Root; S: Steam; L: Leaf; B: Vegetative bud; FB: Floral bud; I: Inflorescence; FBs: Flower buds; MF: Male flower; Fi: Filament; An: Anther; FF: Female flower; YF: Young fruit; RF: Ripe fruit; PC: Pericarp; P: Pulp; and S: Seed. (A). Different development stages of zygotic embryo, when the young fruits emerge cotyledon embryo stage was marked as S1, then collect the zygotic embryo every four days, marked as S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7, ordinal. (B). Relative expression of DlMFT at different stages of longan somatic embryos. NEC: Non-embryogenic callus; EC: The friable-embryogenic callus; ICpEC: Incomplete compact pro-embryogenic cultures; GE: Globular embryos; HE: Heart embryos; CE: Cotyledonary embryos (Reference genes EF1a, FSD, elf4a); (C). Relative expression of DlMFT at different stages of longan embryo (Reference genes EF1a, 2-TU, UBQ); (D). Relative expressions of DlMFT at different tissues of ‘Sijimi’ longan (Reference genes EF1a, FSD, elf4a). (E). Relative expressions of DlMFT at different species of longan seeds (Reference genes FSD, ACTB, 18S). (F). Relative expressions of DlMFT at different tissues of ‘Honghezi’ longan (Reference genes EF1a, ACTB, 18S). Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

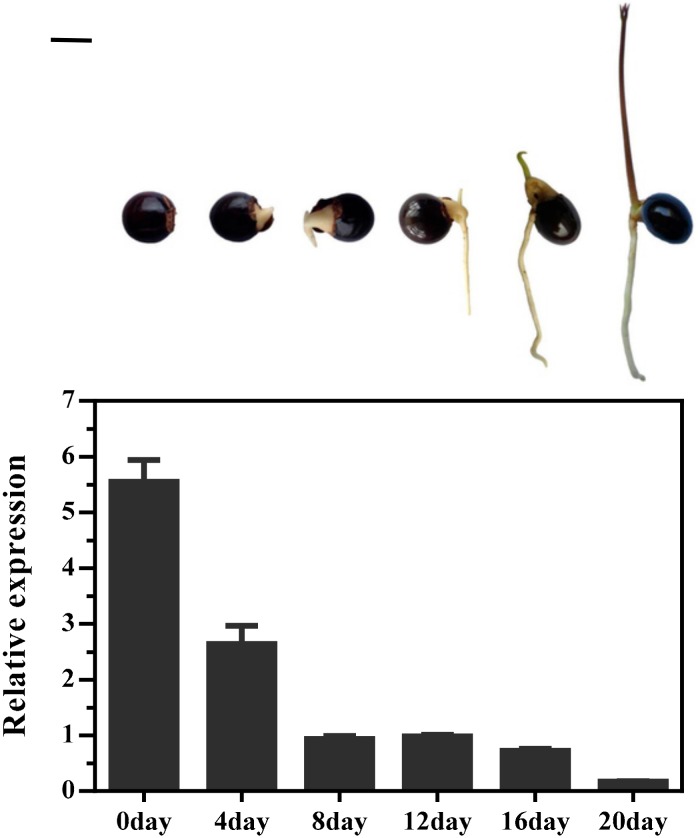

In addition, the expression pattern of DlMFT was analyzed during seed germination processes (0, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 20 day) with quantitative real-time PCR. The expression level of DlMFT was significantly decreased at 4-day and 8-day periods, and then kept at a relatively stable and low level at 8, 12 and 16 day periods, finally markedly decreased at 20-day period (Figure 8), which suggested that DlMFT appeared to be a negative regulator of seed germination.

Figure 8.

Relative expressions of DlMFT during longan seeds germination (Reference genes EF1a, FSD, 18S). Data are means ± SD (n = 3). Bar = 1 cm.

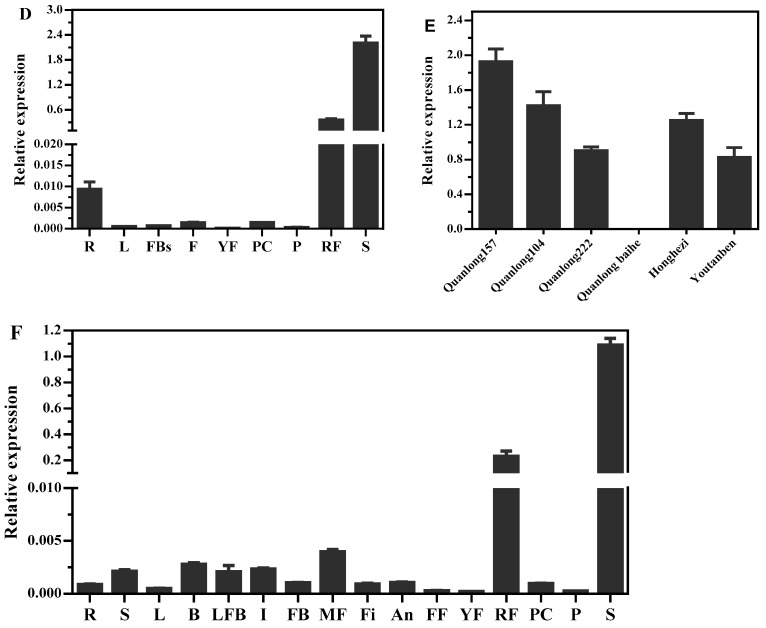

2.5. The Effect of Exogenous Hormones on DlMFT Expression

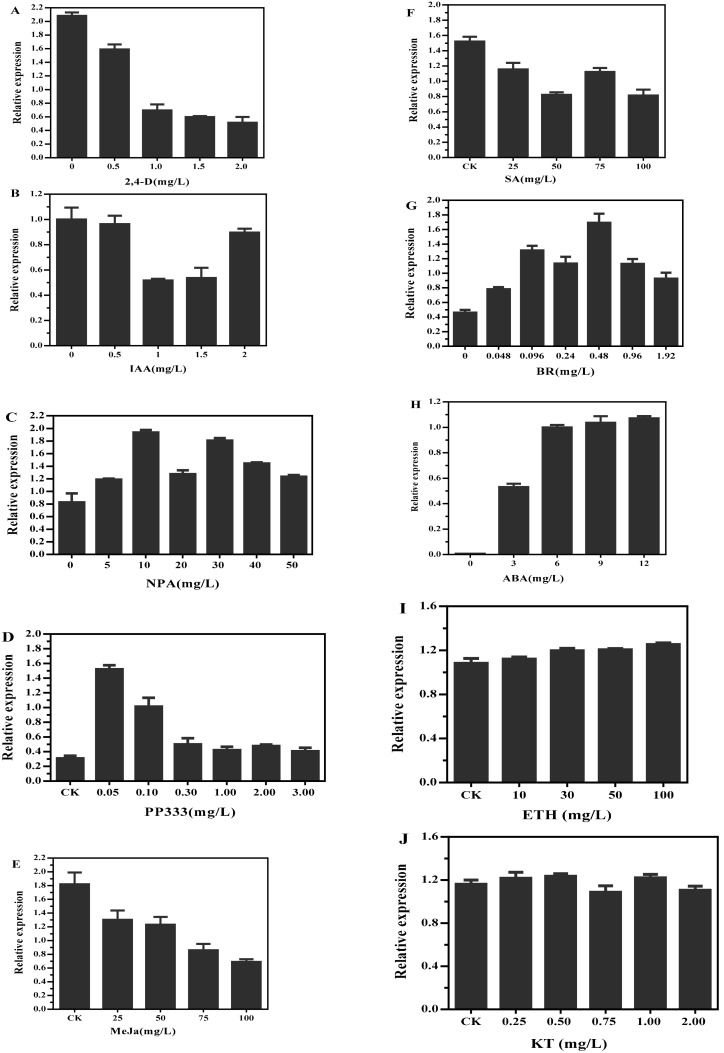

In an attempt to understand whether DlMFT is a hormone responsive gene, we analyzed the transcription of DlMFT in longan EC under different concentration of 2,4-D, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), auxin transport inhibitor (NPA), PP333, MeJa, SA, BR, ABA, kinetin (KT) and ethylene (ETH) for 24 h. Among the treatments, exogenous 2,4-D inhibited its expression, and higher concentration of 2,4-D induced a more significantly expression decline (Figure 9A); IAA at the concentrations of 1.0 and 1.5 mg/L reduced the DlMFT transcript level, by about 1.9-fold compared with the control, but only a slight effect at 0.5 and 2.0 mg/L IAA was observed (Figure 9B). The expression of DlMFT was continuously declined with higher concentration of MeJa (Figure 9E), meanwhile, DlMFT mRNA was also suppressed by SA, under 50 and 100 mg/L SA treatments, its expression level drastically reduced by about 54% compared with the control (Figure 9F). Interestingly, ABA, NPA and BR treatments generated an opposite effect on DlMFT transcript level compared with the 2,4-D, IAA, MeJa and SA treatments; 10 mg/L NPA and 0.48 mg/L BR most obviously enhanced its transcript level (Figure 9C,G). 0.05 and 0.1 mg/L growth retardator (PP333) increased the expression approximately 4.9-fold and 3.3-fold, but when concentration higher than 0.1 mg/L it offset the positive effects (Figure 9D). As shown in Figure 9H, 3 and 6 mg/L ABA enhanced the DlMFT transcript significantly, when the concentration was higher than 6 mg/L, this promotion was only slightly improved. In addition, KT and ETH had no significantly effect on DlMFT transcript level (Figure 9I,J).

Figure 9.

Relative expression of DlMFT transcripts in response to exogenous hormones. EC was treated with nutrient solution in the presence of the listed hormones at the indicated concentrations (MS 0 as control). The DlMFT expression level was normalized to EF-1a, elf4a, and FSD. (A) Treatment with 2,4-D (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mg/L); (B) Treatment with IAA (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mg/L); (C) Treatment with NPA (5, 10, 20, 30, 40 and 50 mg/L); (D) Treatment with PP333 (0.05, 0.1, 0.3, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 mg/L); (E) Treatment with MeJa (25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L) (F) Treatment with SA (25, 50, 75, and 100 mg/L); (G) Treatment with BR (0.048, 0.096, 0.24, 0.48, 0.96 and 1.92 mg/L); (H) ABA at the indicated concentrations (3, 6, 9 and 12 mg/L). Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

Taken together, our results revealed the transcription mechanism of DlMFT in responding to different exogenous hormones in longan EC. The expression of DlMFT was negatively regulated by auxins, MeJa and SA, while auxin inhibitor (NPA), ABA, BR and PP333 did the opposite function, and KT and ETH showed no significantly function on DlMFT expression.

2.6. The Effects of Light and Abiotic Stress on DlMFT Expression

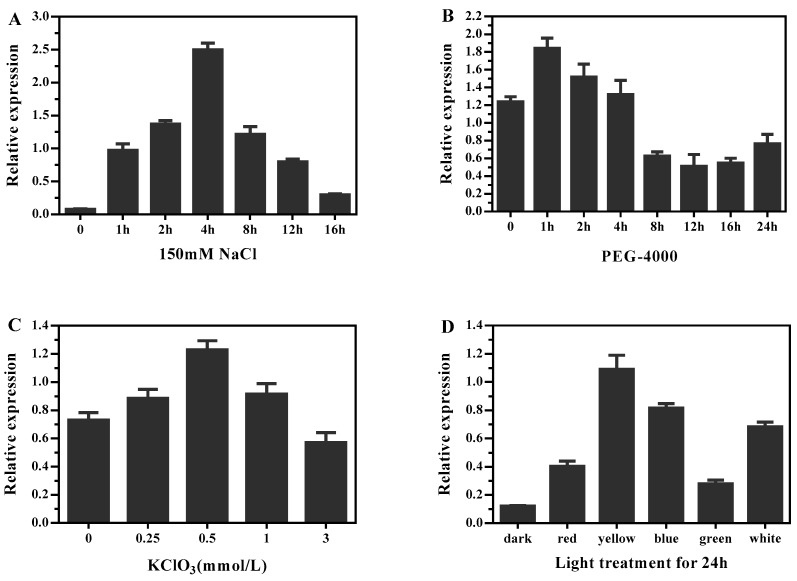

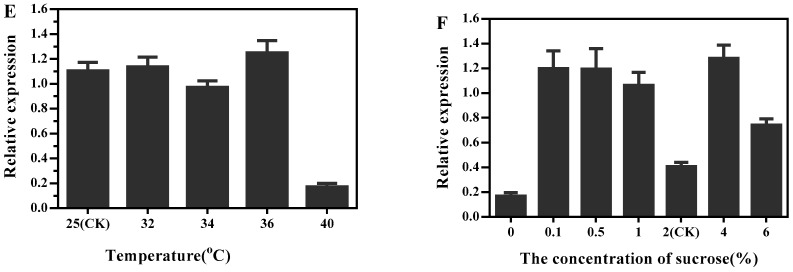

In order to determine whether the transcriptional regulation of DlMFT is affected by abiotic stress, we detected the mRNA level of DlMFT in longan EC exposed to 150 mM NaCl and PEG-4000 for different time, and treated with different concentration of sucrose, KClO3 at 110 rpm at 25 °C under dark conditions for 24 h. In addition, longan EC was treated under different temperature and light qualities conditions for 24 h to define whether DlMFT responded to temperature and light. The results revealed that treatment with 150 mM NaCl for 1, 2, and 4 h induced a significant expression increase as the treatment time increased, and the highest transcript level (~32.4-fold of the control) of DlMFT was observed at 4 h; then, as the treatment time increased, the transcript level declined, but still higher than the control (Figure 10A). In the PEG-4000 treatments, no more than 4 h treatment time slightly enhanced the transcript level of DlMFT. In contrast, when treatment time was longer than 4 h the transcript level obviously declined (Figure 10B). As Figure 10C showed, KClO3 treatment promoted the expression of DlMFT, except 3 mM treatment, and the maximum expression of DlMFT mRNA at 0.5 mM treatment. When treated with different light qualities, the highest transcript level of DlMFT was observed in yellow light, approximate 9.1-fold of the control, the following was blue, white, red and green (Figure 10D). The expression of DlMFT at 32, 34 and 36 °C treatments were similarly to that at 25 °C (CK). However, it showed an arresting decline in the 40 °C treatment (Figure 10E). Interestingly, compared to the control (2% sucrose), higher or lower concentration of sucrose was beneficial to increase the transcript level of DlMFT, but sugar-free treatment showed an opposite effect (Figure 10F). The results indicated that DlMFT mRNA differently responded to salinity stress, PEG-4000, KClO3, temperature and sucrose stress. Besides, DlMFT was a light-responsive gene—the accumulation of DlMFT mRNA was stimulated by various light qualities.

Figure 10.

DlMFT expression in response to abiotic stress. EC was treated with nutrient solution containing 150 mM NaCl or PEG-4000 for different times, KClO3 at the indicated concentrations, or exposed to different light qualities. RNA was isolated from samples treated with: (A) 150 mM NaCl (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 16 h), (B) PEG-4000 (0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h), (C) different light qualities (dark, red, green, blue, and white) for 24 h, (D) KClO3 (0.25, 0.5, 1 and 3 mM/L), (E) different temperature (25, 32, 34, 36 and 40 °C), (F) sucrose (0, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 and 6.0%). Reference genes were EF1a, FSD, and elf4a. Data are means ± SD (n = 3).

3. Discussion

3.1. DlMFT Played a Key Role in Longan Embryogenesis and Seed Germination

Although MFT shows high similarity in sequence to FT and TFL1, the function of MFT was different with FT/TFL1. To date, the functional studies of MFT were mainly focus on expression pattern, flowering time control and seed germination. Previous studies had proved that MFT from different plants showed different functions on flowering time, for example, ectopic expression of AtMFT [21] and AcMFT [33] in Arabidopsis promoted flowering. However, PopMFT [22], SrMFT [32], and GmMFT [29] had no effect on flowering, and HbMFT1 [30] even delayed flowering when it was introduced in Arabidopsis. The recent researches on MFT revealed that most of the MFT showed preferential expression in seeds, and mainly involved in seed development and germination. In Arabidopsis, AtMFT promoted seed germination [24,35], fertility relevant to BR signaling pathway [34], and primary seed dormancy and germination [35]. By contrast, TaMFT [27], FvMFT [36], HbMFT1 [30], GmMFT [29] suppressed seed germination, opposite to the action of AtMFT. In our study, DlMFT showed distinct seed-specific expression pattern, and showed similar upregulated expression during longan SE and ZE processes, especially, highly expressed at the late or mature embryo stages. However, DlMFT was not detected in abortive longan seeds, but highly expressed in normal development seeds. During seed germination, DlMFT was significantly downregulated. Hence, we speculated that DlMFT could served as a key mediator to regulate longan SE and ZE, as well as seed germination.

3.2. DlMFT Was Involved in Various Plant Hormone Signaling Pathways during Longan SE

As we discussed above, MFT play an important role in plant embryo development and seed germination through several hormone-signaling pathways. For instance, Xi et al. found that AtMFT regulated seed germination through a negative feedback loop modulating ABA signaling in Arabidopsis, AtMFT was regulated by DELLA protein [24]. During seed germination, GmMFT was inhibited by ABA, but promoted by GA3, ectopic expression of GmMFT in Arabidopsis affected the expression of ABA and GA metabolism and signaling genes [29]. Ectopic expression of FvMFT in Arabidopsis also inhibited seed germination through integrating ABA and GA signaling [36]. Furthermore, AtMFT promoted fertility through the BR signaling pathway [34], DlMFT also promoted by BR. Hence, MFT played an important role in seed development and germination via ABA, GA, and BR signaling pathway. However, very few studies focus on the plant hormones in regulating MFT during SE.

In our study, DlMFT was inhibited by exogenous 2,4-D, IAA, while promoted by auxin transport inhibitor (NPA) and plant growth inhibitor (PP333) in longan EC. During longan SE, high dose of 2,4-D was essential for SE induction [4], 1.0 mg/L 2,4-D was the key factor of EC long term maintance with growing vigorously [3]. The level of endogenous IAA in early SE was higher than that in NEC, while decrease after GE stage till CE stage [2]. In our study, DlMFT accumulation facilitated the morphogenesis in the middle and late SE and ZE stages, which suggested that DlMFT might involved in auxin signaling pathway during longan SE. ABA is an important plant growth regulator that is involved in embryo formation and maturation [38,39,40]. During SE, ABA not only contributed to normal morphological development of embryos [41,42], but also involved in the improvement of somatic embryo quality for many species by promoting desiccation tolerance and inhibiting precocious germination [43,44,45,46]. In our study, DlMFT was promoted by ABA, consistent with the study that the expression of AtMFT was induced by ABA during seed germination [24]. Plus the fact that endogenous ABA was increased during longan SE, especially at the late embryonic stages [2]. Meanwhile, DlMFT was promoted by exogenous GA3, and inhibited by SA and MeJa. In addition, DlMFT promoter contained multiple elements related to hormone signals, including ABRE for ABA responsiveness, CGTCA-motif for MeJa responsiveness, TCA-element for SA responsiveness, TATC-box and GARE-motif for GA responsiveness. Thus, it was suggested that DlMFT was involved in various hormones signaling during longan SE.

3.3. DlMFT Participated in Responses to Various Abiotic Stresses

Stress acts as an embryogenic stimulus, which plays an important role in plant SE [47]. In citrus, desiccation and low-temperature treatments were beneficial to promote SE, resumed and enhanced the capacity of embryogenesis [48]. It was reported that 25 mM sodium chloride could enhance callus proliferation, somatic embryo formation and conversion in date palm, but a negative effect was found by higher dose of NaCl [49]. Our results also showed that certain treatment time of PEG-4000, NaCl and KClO3 could increase the accumulation of DlMFT. Relatively high temperature was effective to induce secondary somatic embryos, while a low temperature was more suitable for further embryo development [50]. The expression of DlMFT was inhibited with 40 °C treatment, while no significant change of the expression was found when treated with 32, 34 and 36 °C.

Light and temperature are the key abiotic modulators of plant gene expression [51]. Light qualities were employed to significantly enhance SE in many species [39,52,53,54,55,56]. In this study, observed that there were 22 light responsive elements (GT1-motif, SP1, GA-motif, GAG-motif, Box-I, G-box, ACE, AE-box, ATCT-motif, GATA-motif, I-box, and TCT-motif) in the 5′ flanking sequence of DlMFT were observed, which might involve in transcriptional regulations of DlMFT gene. We found that DlMFT responded differently to various light treatments, all the light treatments up-regulated the expression of DlMFT, especially, with the yellow and blue light treatments. These results indicated that DlMFT might be involved in complicated light signaling pathways during longan SE.

In addition, sugars have important hormone-like functions as primary messengers in signal transduction, sugar signaling is yet another potential source for regulation of nuclear genes [57]. High concentration of sucrose generated osmotic stress in culture medium, and played an important role in promoting the maturation of somatic embryos during longan SE [2]. Over-expression of FvMFT in Arabidopsis notably promoted the primary root growth under sugar-deficient condition [36], which suggested that MFT might be involved in sugar signaling. In the present research, compared with 2% sucrose (control), the transcription level of DlMFT was promoted at higher and lower concentration of sucrose, while inhibited under sucrose-deficient condition, which indicated that DlMFT was included in sugar signaling pathway. All these results indicate that DlMFT, at least in part, take part in the abiotic stress response.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

The synchronized embryogenic cultures at different developmental stages, including the non-embryogenic callus (NEC), friable-embryogenic callus (EC), incomplete compact pro-embryogenic cultures (ICpEC), globular embryos (GE), heart-shape embryos (HE), cotyledonary embryos (CE) were obtained by the following previously published methods [2,4]. ‘Honghezi’ Longan tissues or organs for qRT-PCR were showed at Figure 6. Different development stages of zygotic embryo were collected for qRT-PCR, when the young fruits emerge cotyledon embryo stage was marked as S1, then collect the zygotic embryo every four days, marked as S2, S3, S4, S5, S6 and S7, ordinal (Figure 7a).

Transferred 0.2 g 18-day subculture longan EC to MS liquid basal medium (2% sucrose) supplemented with ABA (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/L) (Solarbio, Beijing, China), 2,4-D (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 mg/L) (TCI, Shanghai, China), BR (0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 4.0 μM) (Yuanye, Shanghai, China), IAA (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 3.0 mg/L) (Sigma-Aldrich, SAFC, USA), SA (25, 50, 75, 100mg/L) (SCR, Shanghai, China), MeJa (25, 50, 75, 100 mg/L) (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), GA3 (3, 6, 9, and 12 mg/L) (YEASEN, Shanghai, China), N-1-Naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA: 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM) (Solarbio, Beijing, China), Paclobutrazol (PP333: 25, 50, 75, and 100 μM) (Solarbio, Beijing, China), KClO3 (0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 3.0 mM) (SCR, Shanghai, China) with agitation at 110 rpm at 25 °C under dark conditions for 24 h, with 3 replicates. EC culture in MS liquid medium as control. EC treated with 1 mg/L IAA for different time (4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24 h), treated with 150 mM NaCl for different time (1, 2, 4, 8, 12 and 16 h) and treated with PEG-4000 for different time (1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16 and 24 h) in liquid MS medium with agitation at 110 rpm at 25 °C under dark conditions, EC culture in MS liquid medium as control. EC treated with different light qualities (dark, red, yellow, blue, green and white) was carried out at 25 °C for 24 h. Frozen all samples in liquid nitrogen immediately for 5 min after collecting, then stored at −80 °C for isolating the total RNA.

4.2. Isolation of DlMFT and Its Promoter

The cDNA was synthesized from total RNA of embryo callus using GeneRacer™ Kit (RLM-RACE) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Base on the sequence of MFT from longan embryo callus transcriptome (SRR accession number: SRA050205), specific primers DlMFT-GSP1 and DlMFT-GSP2 couple with 3′-primer and 3′-Nest primer, respectively, were used for 3′-RACE, DlMFT-GSPa and DlMFT-GSPb couple with 5′-primer and 5′-Nest primer, respectively, were used for 5′-RACE, DlMFT-F/R were used for Splice verification and gDNA amplification, all primers are list in Table 1. All amplifications were performed with the following parameters: 94 °C for 3 min (94 °C for 30 s, 54 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min) for 35 cycles, 72 °C for 10 min, but different primer with some modifications. Purified the PCR products by agarose gel electrophoresis, then cloned into pMD 18-T vector (Takara, Mountain View, CA, USA) and sequenced.

Table 1.

Primers Used in Cloning, qRT-PCR, and Vector Constructions.

| Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′–3′) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| DlMFT 3′GSP1 | GGATTCACTGGATGGTCGT | 3′-RACE |

| DlMFT 3′GSP2: | TCAACAGAAGGCACCATTAG | |

| DlMFT 5′GSPa | CCTAATGGTGCCTTCTGTTG | 5′-RACE |

| DlMFT 5′GSPb | GACCATCCAGTGAATCCATT | |

| DlMFT-F | TTTTGGTTATGGCGGCTTC | Splice verification, gDNA amplification |

| DlMFT-R | ATGCTCCAGACCCCATACTA | |

| DlMFT-SP1 | GCGAACCAGTGAATCCATT | Promoter cloning |

| DlMFT-SP2 | CATCAGAGTGACCAGTGAGAGT | |

| DlMFT-SP3 | TGATGTCACAGCCGTTGGT | |

| DlMFT-pro-F | GCGGATCCTTTGCCTTGTCCAACTTCAC | For construction of DlMFT pro:GUS. The added BamI (GGATCC) and NcoI (CCATGG) sites were underlined |

| DlMFT-pro-R | GCCCATGGCAAACAAAGAGAAGAGAGGA | |

| DlMFT-SL-F | GAAGATCTATGGCGGCTTCGGTGGATC | Subcellar localization of DlMFT. The added BglII (AGATCT) site was underlined |

| DlMFT-SL-R | GAAGATCTGCGGCGACGGTTGGCCTTCC | |

| DlMFT-q-F | AACGGCTGTGACATCAAGC | qRT-PCR |

| DlMFT-q-R | CGACCATCCAGTGAATCCA | |

| NbEF1a-F | AGAGGCCCTCAGACAAAC | Reference gene for qRT-PCR in N. benthamiana |

| NbEF1a-R | TAGGTCCAAAGGTCACAA | |

| GeneRacerTM 3′-Primer | GCTGTCAACGATACGCTACGTAACG | 3′-RACE |

| GeneRacerTM 3′-Nested Primer | CGCTACGTAACGGCATGACAGTG | |

| GeneRacerTM 5′-Primer | CGACTGGAGCACGAGGACACTGA | 5′-RACE |

| GeneRacerTM 5′-Nested Primer | GGACACTGACATGGACTGAAGGAGTA |

Based on the gDNA sequence of DlMFT, specific primers SP1, SP2 and SP3 and the adaptor primers AP1 and AP2 were used for cloning the promoter by Tail-RCR (thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR) protocol of genome walking Kit (Takara) from embryogenic callus DNA. The PLACE (https://sogo.dna.affrc.go.jp/cgi-bin/sogo.cgi?lang=en&pj=640&action=page&page=newplace) database and the PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) database were used to analyze the putative cis-acting regulatory elements. The primers used in promoter cloning are list in Table 1.

4.3. Subcellular Localization of DlMFT Protein

In order to generate DlMFT: GFP fusion protein, the coding sequence (CDS) of DlMFT without a terminator codon (TAA) was sub-cloned in BglII sites of pCAMBIA1302-GFP vector for investigating the subcellular localization of DlMFT in Allium cepa. The pCAMBIA1302-GFP vector (served as the positive control) was co-transformed into Allium cepa. 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was used as a maker of nuclear localization. Transient transformation of onion (Allium cepa) scale leaf epidermis cells was performed using the agrobacterium-mediated gene expression system and analyzed by laser scanning con-focal microscopy (Olympus; FV1200, Tokyo, Japan). The protocols were similar to transient transformation of onion scale leaf epidermal cells described previously [58], with some modifications.

4.4. Quantitative Real-Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA of longan embryogenesis cultures and EC under various treatments were extracted by means of TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Total RNA was isolated from longan tissues and different germination stages with the Universal Plant Total RNA Extraction Maxi Kit (Spin-column) (Bioteke Corp., Beijing, China). Total RNA of N. Benthamiana were extracted with TransZol Up Plus RNA Kit (TransGen, Beijing, China). Samples were then treated with DNase I to remove any genomic DNA. RNA was quantified by NanoDrop Lite spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron Corp., Houston, TX, USA) and checked the integrality using 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis.

The cDNA was synthesized with a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit (Takara), the amount of RNA was 500 ng in 10 μL reaction system. qRT-PCR was performed on the Lightcycler 480 system (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland) in a 20 μL final volume containing 10 μL of 2× SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (Takara), 1 μL of 10× diluted cDNA, and 0.8 μL specific primer pairs (100 nM, listed in Table 1), and 7.4 μL of ddH2O. EF-1α, eIF-4α, and Fe-SOD were used as internal controls for calculating the relative expression of DlMFT at different stages of SE [59], different treatments and different tissues of ‘Sijimi’ longan as described previously [5,59]. The expression of DlMFT during longan seeds germination stages was normalized to the expression of longan EF1a, FSD, 18S reference genes. EF1a, ACTB, 18S were used as reference genes for calculating the relative expression of DlMFT at different tissues of ‘Honghezi’ longan. Expression levels of specific genes in N. benthamiana were normalized to NbEF1a. The primers used in this study were listed in Table 1.

4.5. DlMFT Pro:GUS Plasmid Construction and N. Benthamiana Transformation

To generate the DlMFT pro:GUS plasmid, a 1.85-kb BamHI (5′)-NcoI (3′) DlMFT promoter fragment was subcloned into the BamHI-NcoI site of pCAMBIA1301, and designated this recombinant plasmid as DlMFT pro:GUS, used pCAMBIA1301 as control, then transferred DlMFT pro:GUS and pCAMBIA1301 into A. tumefaciens EHA105, respectively. Transient transformed the resulting A. Tumefaciens EHA105 in N. Benthamiana leaves by the injection method, then cultured the transformation plant in the greenhouse at 25 °C under dark conditions for three days. The injected part of the leaves was then harvested for verifying the activity of 35S and DlMFT promoter by qRT-PCR.

Abbreviations

| Dl | Dimocarpus longan |

| MFT | mother of FT and TFL1 |

| FT | Flowering locus T |

| TFL1 | terminal flowering like 1 |

| SE | somatic embryogenesis |

| ZE | zygotic embryogenesis |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| NEC | non-embryogenic callus |

| EC | embryogenic callus |

| ICpEC | incomplete compact pro-embryogenic cultures |

| GE | globular embryos |

| TE | torpedo-shaped embryos |

| CE | cotyledonary embryos |

| 2,4-D | 2,4-Dichlorophenoxyacetic acid |

| IAA | indoleacetic acid |

| ABA | abscisic acid |

| GA | gibberellin |

| SA | salicylic acid |

| MeJa | methyl jasmonate |

| BR | brassinosteroids |

| NPA | N-1-Naphthylphthalamic acid |

| PP333 | Paclobutrazol |

| GFP | green fluorescent protein |

| 35S | CaMV35S |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol |

Author Contributions

Y.C. (Yukun Chen) participated in the research design, carried out the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Y.L. and X.X. (Xu Xuhan) participated in the research design and helped to draft the manuscript. X.X. (Xiaoping Xu), X.C., Y.C. (Yan Chen) and Z.Z. prepared the materials. Z.L. conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31572088, 31672127), the Natural Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scholars in Fujian Province (2015J06004), the Major Science and Technology Project in Fujian Province (2015NZ0002-1).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Lai Z., Chen C., Zeng L., Chen Z. Somatic embryogenesis in longan [Dimocarpus longan Lour.] In: Jain S.M., Gupta P.K., Newton R.J., editors. Somatic Embryogenesis in Woody Plants. Volume 6. Springer; Dordrecht, The Netherlands: 2000. pp. 415–431. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai Z., Chen C. Changes of endogenous phytohormones in the process of somatic embryogenesis in longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) Chin. J. Trop Crops. 2002;23:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai Z., Pan L.Z., Chen Z.G. Establishment and maintenance of longan embryogenic cell lines. J. Fujian Agric. Univ. 1997;26:160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai Z.X., Chen Z.G. Somatic embryogenesis of high frequency from longan embryogenic calli. J. Fujian Agric. Univ. 1997;26:271–276. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai Z., Lin Y. Analysis of the global transcriptome of longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.) embryogenic callus using Illumina paired-end sequencing. BMC Genom. 2013;14:561. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lai Z.X., He Y., Chen Y.T., Cai Y.Q., Lai C.C., Lin Y.L., Lin X.L., Fang Z.Z. Molecular Biology and Proteomics during Somatic Embryogenesis in Dimocarpus longan Lour. International Society for Horticultural Science (ISHS); Leuven, Belgium: 2010. pp. 95–102. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmerman J.L. Somatic Embryogenesis: A Model for Early Development in Higher Plants. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1411–1423. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.10.1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi X., Zhang C., Liu Q., Zhang Z., Zheng B., Bao M. De novo comparative transcriptome analysis provides new insights into sucrose induced somatic embryogenesis in camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora L.) BMC Genom. 2016;17:26. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-2357-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodeman V.L., Ducreux G., Kreis M. Review Article: Zygotic embryogenesis versus somatic embryogenesis. J. Exp. Bot. 1997;48:1493–1509. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/48.313.1493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willemsen V., Scheres B. Mechanisms of pattern formation in plant embryogenesis. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2004;38:587–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chardon F., Damerval C. Phylogenomic Analysis of the PEBP Gene Family in Cereals. J. Mol. Evol. 2005;61:579–590. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0179-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahn J.H., Miller D., Winter V.J., Banfield M.J., Lee J.H., Yoo S.Y., Henz S.R., Brady R.L., Weigel D. A divergent external loop confers antagonistic activity on floral regulators FT and TFL1. EMBO J. 2006;25:605–614. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carmona M.J., Calonje M., Martínez-Zapater J.M. The FT/TFL1 gene family in grapevine. PLANT Mol. Biol. 2007;63:637–650. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9113-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Igasaki T., Watanabe Y., Nishiguchi M., Kotoda N. The Flowering Locus T/Terminal Flower 1 Family in Lombardy poplar. Plant Cell Physiol. 2008;49:291–300. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hedman H., Källman T., Lagercrantz U. Early evolution of the MFT-like gene family in plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;70:359–369. doi: 10.1007/s11103-009-9478-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlgren A., Gyllenstrand N., Källman T., Sundström J.F., Moore D., Lascoux M., Lagercrantz U. Evolution of the PEBP gene family in plants: Functional diversification in seed plant evolution. Plant Physiol. 2011;156:1967–1977. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.176206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradley D., Ratcliffe O., Vincent C., Carpenter R., Coen E. Inflorescence commitment and architecture in Arabidopsis. Science. 1997;275:80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi Y., Kaya H., Goto K., Iwabuchi M., Araki T. A pair of related genes with antagonistic roles in mediating flowering signals. Science. 1999;286:1960–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kardailsky I., Shukla V.K., Ahn J.H., Dagenais N., Christensen S.K., Nguyen J.T., Chory J., Harrison M.J., Weigel D. Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science. 1999;286:1962–1965. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanzawa Y., Money T., Bradley D. A single amino acid converts a repressor to an activator of flowering. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7748–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500932102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoo S.Y., Kardailsky I., Lee J.S., Weigel D., Ahn J.H. Acceleration of flowering by overexpression of MFT (MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1) Mol. Cells. 2004;17:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohamed R., Wang C.T., Ma C., Shevchenko O., Dye S.J., Puzey J.R., Etherington E., Sheng X., Meilan R., Strauss S.H., et al. Populus CEN/TFL1 regulates first onset of flowering, axillary meristem identity and dormancy release in Populus. Plant J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2010;62:674–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward J.K., Samanta Roy D., Chatterjee I., Bone C.R., Springer C.J., Kelly J.K. Identification of a major QTL that alters flowering time at elevated [CO2] in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e49028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xi W., Liu C., Hou X., Yu H. MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 regulates seed germination through a negative feedback loop modulating ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1733–1748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishikawa F., Endo T., Shimada T., Fujii H., Shimizu T., Omura M. Isolation and Characterization of a Citrus FT/TFL1 Homologue (CuMFT1), Which Shows Quantitatively Preferential Expression in Citrus Seeds. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2008;77:285–292. doi: 10.2503/jjshs1.77.38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Danilevskaya O.N., Meng X., Hou Z., Ananiev E.V., Simmons C.R. A genomic and expression compendium of the expanded PEBP gene family from maize. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:250–264. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.109538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakamura S., Abe F., Kawahigashi H., Nakazono K., Tagiri A., Matsumoto T., Utsugi S., Ogawa T., Handa H., Ishida H. A wheat homolog of MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 acts in the regulation of germination. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3215–3229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tao Y., Luo L., He L., Ni J., Xu Z. A promoter analysis of MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 1 (JcMFT1), a seed-preferential gene from the biofuel plant Jatropha curcas. J. Plant Res. 2014;127:513–524. doi: 10.1007/s10265-014-0639-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li Q., Fan C., Zhang X., Wang X., Wu F., Hu R., Fu Y. Identification of a soybean MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 homolog involved in regulation of seed germination. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e99642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bi Z., Li X., Huang H., Hua Y. Identification, Functional Study, and Promoter Analysis of HbMFT1, a Homolog of MFT from Rubber Tree (Hevea brasiliensis) Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:247. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang X., Wang C., Pang C., Wei H., Wang H., Song M., Fan S., Yu S. Characterization and Functional Analysis of PEBP Family Genes in Upland Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e161080. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ito-Inaba Y., Masuko-Suzuki H., Maekawa H., Watanabe M., Inaba T. Characterization of two PEBP genes, SrFT and SrMFT, in thermogenic skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus renifolius) Sci. Rep. 2016;6:29440. doi: 10.1038/srep29440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hou C., Yang C. Comparative analysis of the pteridophyte Adiantum MFT ortholog reveals the specificity of combined FT/MFT C and N terminal interaction with FD for the regulation of the downstream gene AP1. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;91:563–579. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0489-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xi W., Yu H. MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 regulates seed germination and fertility relevant to the brassinosteroid signaling pathway. Plant Signal. Behav. 2010;5:1315–1317. doi: 10.4161/psb.5.10.13161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaistij F.E., Gan Y., Penfield S., Gilday A.D., Dave A., He Z., Josse E., Choi G., Halliday K.J., Graham I.A. Differential control of seed primary dormancy in Arabidopsis ecotypes by the transcription factor SPATULA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:10866–10871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301647110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu Y., Gao Y.R., Wei W., Zhang K., Feng J.Y. Strawberry MOTHER OF FT AND TFL1 regulates seed germination and post-germination growth through integrating GA and ABA signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2016;126:343–352. doi: 10.1007/s11240-016-1002-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho W.W.H., Weigel D. Structural features determining flower-promoting activity of Arabidopsis FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant Cell. 2014;26:552–564. doi: 10.1105/tpc.113.115220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernando S.C., Gamage C.K. Abscisic acid induced somatic embryogenesis in immature embryo explants of coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) Plant Sci. 2000;151:193–198. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J., Wu L., Hu B., Yi X., Liu R., Deng Z., Xiong X. The Influence of Plant Growth Regulators and Light Quality on Somatic Embryogenesis in China Rose (Rosa chinensis Jacq.) J. Plant Growth Regul. 2014;33:295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00344-013-9371-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Finkelstein R.R., Tenbarge K.M., Shumway J.E., Crouch M.L. Role of ABA in Maturation of Rapeseed Embryos. Plant Physiol. 1985;78:630–636. doi: 10.1104/pp.78.3.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang X., Zhang X. Regulation of Somatic Embryogenesis in Higher Plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2010;29:36–57. doi: 10.1080/07352680903436291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langhansová L., Konrádová H., Vanĕk T. Polyethylene glycol and abscisic acid improve maturation and regeneration of Panax ginseng somatic embryos. Plant Cell Rep. 2004;22:725–730. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0750-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rai M.K., Jaiswal V.S., Jaiswal U. Effect of ABA and sucrose on germination of encapsulated somatic embryos of guava (Psidium guajava L.) Sci. Hortic. 2008;117:302–305. doi: 10.1016/j.scienta.2008.04.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vahdati K., Bayat S., Ebrahimzadeh H., Jariteh M., Mirmasoumi M. Effect of exogenous ABA on somatic embryo maturation and germination in Persian walnut (Juglans regia L.) Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2008;93:163–171. doi: 10.1007/s11240-008-9355-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rai M.K., Shekhawat N.S., Harish, Gupta A.K., Phulwaria M., Ram K., Jaiswal U. The role of abscisic acid in plant tissue culture: A review of recent progress. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011;106:179–190. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-9923-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robichaud R.L., Lessard V.C., Merkle S.A. Treatments affecting maturation and germination of American chestnut somatic embryos. J. Plant Physiol. 2004;161:957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zavattieri M.A., Frederico A.M., Lima M., Sabino R., Arnholdtschmitt B. Induction of somatic embryogenesis as an example of stress-related plant reactions. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2010;13:1–9. doi: 10.2225/vol13-issue1-fulltext-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao Y., Deng X. Stress treatments and DNA methylation affected the somatic embryogenesis of citrus callus. Acta Bot. Sin. 2002;44:673–677. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ibraheem Y.M., Pinker I., Böhme M.H. The effect of sodium chloride-stress on ‘zaghlool’ date palm somatic embryogenesis. Acta Hortic. 2012:961. doi: 10.17660/ActaHortic.2012.961.48. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang J., Wu S., Li C. High Efficiency Secondary Somatic Embryogenesis in Hovenia dulcis Thunb. through Solid and Liquid Cultures. Sci. World J. 2013;2013:718754. doi: 10.1155/2013/718754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soitamo A.J., Piippo M., Allahverdiyeva Y., Battchikova N., Aro E. Light has a specific role in modulating Arabidopsis gene expression at low temperature. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Michler C.H., Lineberger R.D. Effects of light on somatic embryo development and abscisic levels in carrot suspension cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1987;11:189–207. doi: 10.1007/BF00040425. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.D’Onofrio C., Morini S., Bellocchi G. Effect of light quality on somatic embryogenesis of quince leaves. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1998;53:91–98. doi: 10.1023/A:1006059615088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Merkle S.A., Montello P.M., Xia X., Upchurch B.L., Smith D.R. Light quality treatments enhance somatic seedling production in three southern pine species. Tree Physiol. 2006;26:187–194. doi: 10.1093/treephys/26.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.De-la-Peña C., Galaz-Avalos R.M., Loyola-Vargas V.M. Possible role of light and polyamines in the onset of somatic embryogenesis of Coffea canephora. Mol. Biotechnol. 2008;39:215–224. doi: 10.1007/s12033-008-9037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rodríguez-Sahagún A., Acevedo-Hernández G., Rodríguez-Domínguez J.M., Rodríguez-Garay B., Cervantes-Martínez J., Castellanos-Hernández O.A. Effect of light quality and culture medium on somatic embryogenesis of Agave tequilana Weber var. Azul. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2011;104:271–275. doi: 10.1007/s11240-010-9815-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rolland F., Moore B., Sheen J. Sugar Sensing and Signaling in Plants. Plant Cell. 2002;14:S185–S205. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu K., Huang X., Wu M., Wang Y., Chang Y., Liu K., Zhang J., Zhang Y., Zhang F., Yi L., et al. A rapid, highly efficient and economical method of Agrobacterium-mediated in planta transient transformation in living onion epidermis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e83556. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lin Y.L., Lai Z.X. Reference gene selection for qPCR analysis during somatic embryogenesis in longan tree. Plant Sci. 2010;178:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.02.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]