Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignant types of cancer, with a high mortality rate. Sorafenib is the sole approved oral clinical therapy against advanced HCC. However, individual patients exhibit varying responses to sorafenib and the development of sorafenib resistance has been a new challenge for its clinical efficacy. The current study identified gene biomarkers and key pathways in sorafenib-resistant HCC using bioinformatics analysis. Gene dataset GSE73571 was obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, including four sorafenib-acquired resistant and three sorafenib-sensitive HCC phenotypes. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the web tool GEO2R. Functional and pathway enrichment of DEGs were analyzed using the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery and the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins and Cytoscape. A total of 1,319 DEGs were selected, which included 593 upregulated and 726 downregulated genes. Functional and pathway enrichment analysis revealed DEGs enriched in negative regulation of endopeptidase activity, cholesterol homeostasis, DNA replication and repair, coagulation cascades, insulin resistance, RNA transport, cell cycle and others. Eight hub genes, including kininogen 1, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, apolipoprotein C3, alpha 2-HS glycoprotein, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2, secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich, vitronectin and vimentin were identified from the PPI network. In conclusion, the present study identified DEGs and key genes in sorafenib-resistant HCC, which further the knowledge of potential mechanisms in the development of sorafenib resistance and may provide potential targets for early diagnosis and new treatments for sorafenib-resistant HCC.

Keywords: bioinformatics analysis, sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma, differentially expressed gene, protein-protein interaction, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analysis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a malignant tumor that has become the third leading cause of cancer-associated cases of mortality (1). Sorafenib, an oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, targets various molecular mechanisms, including tumor growth and angiogenesis (2). It is the only systemic therapy drug for HCC that is approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration and as such has been applied in the clinic extensively (3). The clinical efficacy of sorafenib is limited and patients face poor prognosis; no difference in recurrence-free survival between sorafenib and a placebo-controlled group has been reported (4). Furthermore, time-to-tumor progression and overall survival were not observed to be different for patients treated with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) in conjunction with sorafenib over the TACE placebo group in a stent-protected angioplasty vs. carotid endarterectomy trial (5). Several potential mechanisms of sorafenib resistance were proposed. The processes of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and mesenchymal-epithelial transition, along with critical growth factors and signaling pathways, exhibit an impact on sorafenib resistance, including activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway (6). Additionally, cancer stem cells (CSCs) and CSC-like cells, which retain strong proliferation ability, multi-directional differentiation capacity and high drug-resistance properties, may not be completely cleared by sorafenib but differentiate and develop into novel cancer tissues, resulting in the metastasis and recurrence of HCC (6). Biological processes involved in tumor microenvironment, inflammation, fibrosis, angiogenesis, hypoxia, autophagy, viral reactivation and oxidative stress may serve a pivotal role in the resistance to sorafenib (6). However, the resistance mechanisms for sorafenib remain unclear and novel research may provide insight into the discovery of an effective treatment or personalized therapy for advanced HCC.

High-throughput microarray technology has been widely used to analyze the gene expression data of various cancer types (7). It has been a promising method to screen for potential biomarkers in tumor diagnosis and pathways involved in tumorigenesis and drug resistance (7–9). In the current study, microarray data for GSE73571 facilitated the investigation of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in sorafenib-sensitive and sorafenib-resistant tumors. Gene ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis were performed and a protein-protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed, identifying hub genes. The bioinformatics analysis of crucial genes or pathways in sorafenib-resistant HCC revealed potential strategies for improving clinical efficacy.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

Gene expression profile data (GSE73571) were obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo). Four sorafenib-acquired resistant HCC and three sorafenib-sensitive phenotypes were included. The array data were acquired from Affymetrix Human Gene 1.0 ST Array [GPL6244; transcript (gene) version].

DEG analysis

GEO2R (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/) was used to compare two or more groups of samples in a GEO series to identify genes that were differentially expressed under the same experimental conditions. DEGs in resistant and sensitive samples were analyzed by GEO2R. |log2FC|≥0.4 and P<0.01 were used as cut-off criteria and defined a statistically significant difference (10). A heat map of DEGs was generated using HemI 1.0 (https://sourceforge.net/projects/mev-tm4/).

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis of the screened DEGs was performed using the Database of Annotation Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID; http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). DAVID contains a series of functional annotation programs to explore abundant biological messages of genes and information mapped in DAVID was important for the completion of high-throughput gene functional analysis (11). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference (12).

PPI network analysis

PPI network analysis was performed using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING; http://string-db.org/). STRING provides information associated with predicted and proven interactions between large numbers of proteins. Identified DEGs were imported into STRING. Genes with a combined score of >0.4 were identified as significant. The PPI network was built using Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/). In addition, higher-degree nodes were regarded as hub nodes (12). Sub-modules of the PPI network were analyzed by Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE; Version 1.4.2; by Bader Lab, department of Biochemistry, University of Toronto; Toronto, Canada) (13), with the criteria set as follows: number of nodes >4 and MCODE score >3. GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis of DEGs of the sub modules was finished by DAVID.

Results

DEG analysis

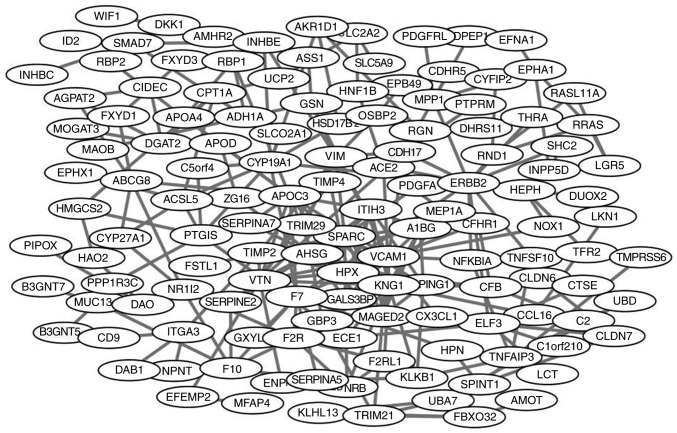

According to the cut-off criteria (P<0.05 and |log2FC|≥2), a total of 1,319 DEGs from sorafenib-resistant and sorafenib-sensitive specimens were identified, with 593 up- and 726 downregulated genes. A heat map of the top 50 up- and downregulated DEGs is presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Heat map of differentially expressed genes (the top 50 up- and downregulated genes; P<0.05). Red indicates a higher and green a lower expression level.

GO enrichment analysis

GO enrichment analysis was performed by DAVID. GO biological processes analysis revealed that upregulated DEGs were associated with negative regulation of endopeptidase activity, cholesterol homeostasis and fibrinolysis and downregulated DEGs were associated with DNA replication and repair (Table I). For molecular function, upregulated genes were enriched in collagen and receptor binding and serine-type endopeptidase activity, while downregulated genes were enriched in poly(A) RNA binding, helicase activity and ATP binding. Additionally, GO cell component analysis revealed that upregulated genes were primarily located in the extracellular space, extracellular exosome and extracellular region and the location of downregulated DEGs was primarily in nucleolus, nucleoplasm and centrosome.

Table I.

Gene ontology analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes in sorafenib-resistant HCC.

| A, Upregulated expression | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Term | Count | % | P-value |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005615/extracellular space | 110 | 16.492 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0070062/extracellular exosome | 177 | 26.537 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005576/extracellular region | 100 | 14.993 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0072562/blood microparticle | 21 | 3.148 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0016021/integral component of membrane | 235 | 35.232 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0010951/negative regulation of endopeptidase activity | 18 | 2.699 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0042632/cholesterol homeostasis | 13 | 1.949 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0042730/fibrinolysis | 8 | 1.199 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0002576/platelet degranulation | 15 | 2.249 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0030198/extracellular matrix organization | 20 | 2.999 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0005518/collagen binding | 11 | 1.649 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0005102/receptor binding | 29 | 4.348 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0004252/serine-type endopeptidase activity | 24 | 3.598 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0001948/glycoprotein binding | 10 | 1.499 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0008131/primary amine oxidase activity | 4 | 0.600 | <0.001 |

| Extracellular space means GO enrichment of cellular primarily enriches in the extracellular space. | ||||

| B, downregulated expression | ||||

| Category | Term/gene function | Count | % | P-value |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0044822/poly(A) RNA binding | 99 | 18.099 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0004386/helicase activity | 20 | 3.656 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0005524/ATP binding | 89 | 16.271 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0004004/ATP-dependent RNA helicase activity | 14 | 2.559 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_MF_DIRECT | GO:0008026/ATP-dependent helicase activity | 9 | 1.645 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005730/nucleolus | 75 | 13.711 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005654/nucleoplasm | 152 | 27.788 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005813/centrosome | 43 | 7.861 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005634/nucleus | 199 | 36.380 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_CC_DIRECT | GO:0005814/centriole | 16 | 2.925 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006260/DNA replication | 25 | 4.570 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006281/DNA repair | 27 | 4.936 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0000732/strand displacement | 10 | 1.828 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0000731/DNA synthesis involved in DNA repair | 11 | 2.011 | <0.001 |

| GOTERM_BP_DIRECT | GO:0006974/cellular response to DNA damage stimulus | 23 | 4.205 | <0.001 |

BP, biological process; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; GO, gene ontology.

KEGG pathway analysis

To gain a deeper understanding of significant DEGs, a pathway enrichment analysis was performed. As presented in Table II, upregulated genes were enriched in pathways of coagulation cascades, insulin resistance and metabolic pathways, while downregulated DEGs were significantly associated with pathways of RNA transport and cell cycle.

Table II.

KEGG pathway analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes in sorafenib-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma.

| A, Upregulated genes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Gene count | % | P-value | Genes |

| hsa04610: Complement and coagulation cascades | 20 | 2.999 | <0.001 | KNG1, F12, F10, CFB, C3, C1R, SERPING1, F7, C1S, C8B, FGG, FGB, SERPINF2, KLKB1, SERPINA5, SERPIND1, C2, CFI, PLAU, F2R |

| hsa04142: Lysosome | 14 | 2.099 | 0.003047 | TCIRG1, CTSZ, CLTB, ACP5, ACP2, CTSA, CTSS, CTSL, LAPTM5, TPP1, ARSA, CTSE, SMPD1, CTSD |

| hsa04931: Insulin resistance | 13 | 1.949 | 0.003298 | SREBF1, NR1H2, PPP1R3C, PPP1R3B, SOCS3, SLC2A2, PRKAG2, PRKAB2, NFKBIA, CREB3L3, SLC27A3, CPT1A, PCK1 |

| hsa01100: Metabolic pathways | 74 | 11.094 | 0.006009 | TM7SF2, ALAD, OGDHL, ADH1C, ADH1A, AGXT, CKB, PTGIS, P4HA2, ST3GAL5, MAT1A, RGN, DAO, ITPK1, AGPAT3, AGPAT2, GATM, ACADS, SPTLC3, FAXDC2, PISD, PNPLA3, PMM1, ALDH3B1, DGAT2, CYP27A1, HAO2, EXT1, AOC1, AKR1D1, LCT, AOC3, ACAA1, GALNT2, ENPP7, ASS1, HSD17B2, ALDOC, ENPP3, CERS4, PLPP3, PIPOX, THTPA, B3GNT5, DHCR7, PLA2G12B, PEMT, HAAO, ENO3, ETNK2, FUT2, BDH1, GAL3ST1, ACSL5, CYP19A1, TCIRG1, MOGAT3, ST6GAL1, NDUFA2, SI, MAOB, HOGA1, AMPD3, IDNK, PCK1, POLD4, BAAT, HMGCS2, SMPD1, LIPC, PHYKPL, PON3 |

| hsa04975: Fat digestion and absorption | 7 | 1.049 | 0.007472 | APOA4, ABCG8, MOGAT3, DGAT2, PLA2G12B, PLPP3, AGPAT2 |

| B, Downregulated genes | ||||

| Name | Gene count | % | P-value | Genes |

| hsa03008: Ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes | 17 | 3.108 | <0.001 | XPO1, GTPBP4, UTP6, UTP15, GNL3L, BMS1, DROSHA, WDR36, POP1, WDR3, NOP58, GNL2, MDN1, RBM28, SPATA5, WDR43, GNL3 |

| hsa03013: RNA transport | 17 | 3.108 | <0.001 | XPOT, XPO1, XPO5, ALYREF, EIF5B, NUPL2, NUP155, PNN, TRNT1, UPF3B, SEH1L, NUP205, POP1, EIF3J, RANBP2, TPR, GEMIN5 |

| hsa03460: Fanconi anemia pathway | 9 | 1.645 | <0.001 | FANCM, BLM, FANCD2, FANCI, BRCA2, BRIP1, ATR, FANCA, BRCA1 |

| hsa04742: Taste transduction | 7 | 1.280 | <0.001 | TAS2R13, TAS2R14, TAS2R19, TAS2R46, TAS2R43, TAS2R20, TAS2R10 |

| hsa04110: Cell cycle | 9 | 1.645 | 0.014438 | CDC7, CDC6, RBL1, PRKDC, ATR, MYC, CDC25A, ATM, STAG1 |

KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes.

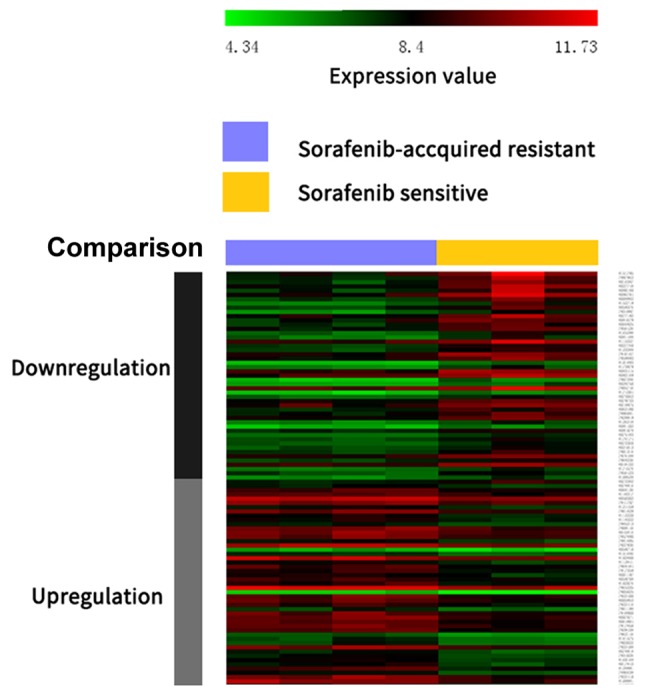

PPI network construction and module screening

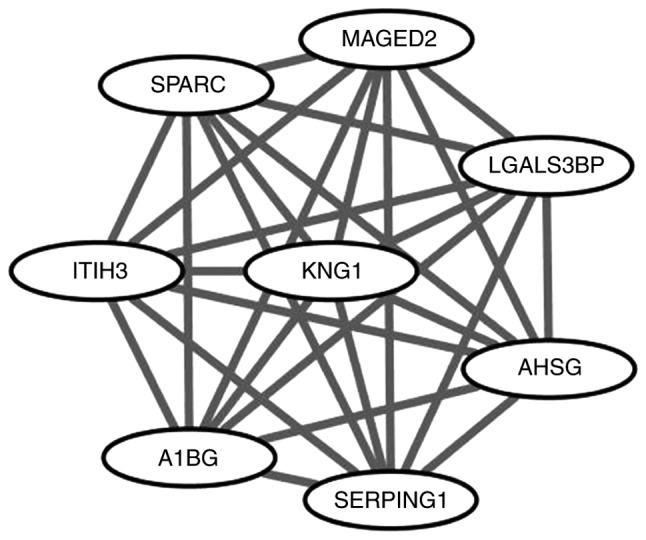

The PPI network of DEGs is presented in Fig. 2. The network was composed of 279 nodes and 636 edges. Degrees >10 were set as the cutoff criterion, from which eight genes were selected as hub genes. Hub genes included kininogen 1 (KNG1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1), apolipoprotein C3 (APOC3), alpha 2-HS glycoprotein (AHSG), erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), secreted protein acidic and cysteine rich (SPARC), vitronectin (VTN) and vimentin (VIM). The significant module of DEGs with the highest score was selected using the plug-in MCODE program. This module included 8 nodes and 28 edges (Fig. 3). No enrichment of GO terms and KEGG pathways was observed in this module.

Figure 2.

Protein-protein interaction network of differentially expressed genes.

Figure 3.

Significant module from the protein-protein interaction network.

Discussion

In the present study, gene expression data of GSE73571 were extracted from the GEO database. Four sorafenib-resistant and three sorafenib-sensitive HCC samples were selected for analysis. A total of 593 downregulated and 726 upregulated DEGs were identified among the sorafenib-sensitive and sorafenib-resistant phenotypes with HCC. Function annotation revealed that these DEGs were primarily associated with complement and coagulation cascades, DNA replication, synthesis and repair. PPI network analysis suggested that eight hub genes exhibited higher degrees of interaction, which may describe new targets in sorafenib resistance.

GO term analysis reveled that upregulated DEGs were primarily associated with negative regulation of endopeptidase activity, cholesterol homeostasis and fibrinolysis. Peptidases are crucial in tumor formation and development in various ways, including regulating the process of neoplastic growth, as adhesion molecules, through involvement in intracellular signaling and extracellular matrix degradation (14). Various studies indicated that the expression of various peptidases, including circulating aminopeptidase N/CD13, varies among cancer types at different stages (15–18). Cholesterol metabolites are related to the development of various cancers (19,20). Management of cholesterol homeostasis may lead to lower risks of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, breast and endometrial cancers (21–23). The fibrinolytic system was verified to promote tumor growth and it may be involved in apoptosis inhibition, angiogenesis, cell proliferation and extracellular matrix (24,25). Downregulated DEGs were primarily involved in DNA replication and repair. DNA replication and repair may be involved in the development of certain types of cancer, by regulating the cell cycle, angiogenesis, cell differentiation and cell signaling (26–29). Additionally, KEGG pathway analysis of upregulated genes revealed involvement in complement and coagulation cascades, insulin resistance and metabolic pathways. KEGG pathway analysis of downregulated DEGs exhibited participation in RNA transport and cell cycle. A previous study reported that constituents of the coagulation cascade could affect cancer progression (30) and the complement and coagulation cascade pathway enrichment in colorectal cancer (CRC) and HCC has been described (31,32). Poor glycemic control is a prognostic element in patients with HCC and diabetes (33) and insulin resistance is considered as a risk factor in HCC development (34). Metabolic pathways, cell cycle and RNA transport have been associated with carcinogenesis, cancer cell survival and growth (35–37). Therefore, the identification of the above mentioned pathways may lead to novel prognostic and therapeutic methods in HCC and sorafenib-resistant HCC.

In the present study, the following eight hub genes were identified through PPI network construction and analysis: KNG1, VCAM1, APOC3, AHSG, ERBB2, SPARC, VTN and VIM. KNG1, a cysteine proteinase inhibitor, exhibited the highest degree of connectivity in the PPI network. It participates in blood coagulation, inflammatory response, apoptosis regulation and the prevention process of metastasis in cancer cells (38,39). KNG1 is overexpressed in CRC and HCC (40) and is regarded as a potential prognostic marker for CRC, as patients with increased KNG1 expression exhibit decreased survival rates when compared with lower KNG1 expression patients (39,41). Additional studies reported that KNG1 may be involved in cholesterol and lipoprotein metabolism disturbance and take part in the complex interplay between the hemostatic system and immune response in hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated HCC (39,40). Differences in KNG1 expression were observed among patients with multidrug-resistant and drug-sensitive tuberculosis and healthy control patients, and it is suspected that blood coagulation serves a role in the resistant ability of KNG1 (42).

The second hub gene is VCAM1, a mediator of angiogenesis, which serves a critical function in endothelium development during angiogenesis (43,44). It promotes cancer cell adhesion to the endothelium and is associated with immune and inflammatory responses of tumors (45). High VCAM1 serum levels have been reported for various cancer types, including HCC, chronic liver disease, breast cancer and CRC, and VCAM1 is considered a potential predictor for cancer prognosis (46–50). The amount of VCAM1 in the serum is dependent on tumor stage and neoplasm metastasis (51). VCAM1 expression decreased following carboplatin intervention in mice with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer, while high-level expression was maintained in mice with platinum-resistant tumors (52). VCAM1 has been recognized as a response monitor in the treatment of ovarian cancer and as a molecular biomarker in chemotherapy-associated sensitivity, which allows for earlier alterations in treatment decisions (52).

APOC3, the third hub gene, is expressed in the liver and participates in very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) triglyceride (TG) metabolism by inhibiting VLDL-TG clearance in vivo and promoting absorption of intestinal TG and VLDL-TG production (53). APOC3 polymorphism is considered to be an independent risk factor of hepatocarcinogenesis and HCC development in patients with chronic hepatitis B (54). It was suggested that APOC3 may be involved in HCC familial aggregation in China (55). There is no evidence indicating an association between APOC3 and sorafenib or other drug resistance, making it a potential target for further research.

AHSG, a serum glycoprotein, is produced by hepatocytes and is involved in several metabolic disorders, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (56,57), genesis of diabetes (58) and metabolic syndrome (59). It is significantly increased in HCC when compared with normal patients. AHSG is also an important biomarker of recent mortality in liver cirrhosis and liver cancer patients (60). AHSG is associated with cancer progression through regulation of the transforming growth factor-β signaling pathway (61,62). In the present study, dysregulation of AHSG was observed, which is in accordance with a previous study describing that the upregulation of AHSG in HCC drug-resistant cell lines may be a predictor for HCC with chemotherapeutic drug resistance (63). The levels of AHSG and five other selected serum biomarkers were proposed to predict resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancers (64). The differences in complement system and LDL oxidation may contribute to this phenomenon (64).

Another hub gene, ERBB2, encodes for a receptor tyrosine kinase, a member of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) family, and is involved in fixation and propagation of oncogene mutations (65). Comprehensive studies have demonstrated that increased ERBB2 expression in breast and ovarian cancer is associated with poor prognosis (66,67). ERBB2 was upregulated in the current study and has been regarded as a potential critical regulator for malignant transformations in early HCC (68). In specific studies on HCC, the percentage of control cases expressing ErbB2 ranged from 0–30% (69–72). ERBB2 expression level potentially refers to different HCC stages (71,73). Cetuximab and panitumumab, EGFR-targeted antibodies, are treatments for metastatic CRC (74). The amplification of ERBB2 contributes to the primary (de novo) resistance to anti-EGFR treatment, the mechanism of which is associated with the activation of the MEK-ERK cascade (74).

The other three identified hub genes in the current study were SPARC, VTN and VIM. SPARC encodes a protein involved in numerous biological processes, which are associated with various cancer mechanisms, including development, cell apoptosis, angiogenesis, cell differentiation, cell proliferation, cell adhesion and migration (75,76). Lau et al (77) reported high SPARC expression in HCC compared with non-tumorous liver. Elevated SPARC expression promotes tumor aggressiveness of melanoma (78), glioblastoma (79) and prostate cancer (80). The association between high SPARC mRNA expression and low pathological response rate in breast tumor cells following neoadjuvant anthracycline treatment has been confirmed (81). VTN, a representative acute-phase glycoprotein, is expressed and secreted by hepatocytes (82). Interactions with integrins may enhance cell adhesion and the spread in serum and extracellular matrix (82). Increased VTN was described as a poor prognostic tool for patients with HCC as it is a primary component of the stroma and accelerates leucocyte accumulation (83) and cell migration (84). VTN has an adverse effect on HCC development in HCV-infected patients with liver cirrhosis (85). Additionally, VTN adhesion was previously suggested to contribute to drug resistance in chemotherapy-treated myeloma cells through Notch signaling activation (86). Elevated VIM expression was observed in small size HCC (≤2 cm) (87). It has been suggested that the circulating level of VIM may be more sensitive and specific compared with AFP in detecting small tumors and VIM expression has been recognized as a potential biomarker for HCC diagnosis (87). VIM is overexpressed in CRC cells with butyrate or histone deacetylase inhibitor resistance, which is likely to mediate cell signaling/gene expression cascades and to integrate the EMT process in drug-resistant CRC cells (88).

The genes identified in the current study may be associated with HCC genesis, development and prognosis and potentially contribute to sorafenib resistance in HCC. Future research into these genes may provide information on the mechanism of sorafenib-resistant HCC and hold potential for novel therapeutic methods for drug-resistant HCC.

In conclusion, a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of DEGs was performed, revealing genes that may be involved in the biological process of sorafenib-resistant HCC. A series of potential targets has been provided, which may be considered for future exploration.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The study was supported by the Scientific Research Project of Medical Service of National Clinical Research Base of Traditional Chinese Medicine of State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant no. JDZX2015173) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 21675177).

Availability of data and materials

Data and materials have been provided as part of the submitted article.

Authors' contributions

HY, DH and ZC conceived the present study; WY, HL and SL analyzed and interpreted chip data; DH, SL and HL drafted the manuscript; and. HY and ZC revised the article. All authors have given final approval of the version to be published.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Grazie M, Biagini MR, Tarocchi M, Polvani S, Galli A. Chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: The present and the future. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:907–920. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v9.i21.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tovar V, Cornella H, Moeini A, Vidal S, Hoshida Y, Sia D, Peix J, Cabellos L, Alsinet C, Torrecilla S, et al. Tumour initiating cells and IGF/FGF signalling contribute to sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2017;66:530–540. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, Chau GY, Yang J, Kudo M, Cai J, Poon RT, Han KH, Tak WY, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): A phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1344–1354. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lencioni R, Llovet JM, Han G, Tak WY, Yang J, Guglielmi A, Paik SW, Reig M, Kim DY, Chau GY, et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: The SPACE trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64:1090–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Jin R, Zhao J, Liu J, Ying H, Yan H, Zhou S, Liang Y, Huang D, Liang X, et al. Potential molecular, cellular and microenvironmental mechanism of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nannini M, Pantaleo MA, Maleddu A, Astolfi A, Formica S, Biasco G. Gene expression profiling in colorectal cancer using microarray technologies: Results and perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mok SC, Bonome T, Vathipadiekal V, Bell A, Johnson ME, Wong KK, Park DC, Hao K, Yip DK, Donninger H, et al. A gene signature predictive for outcome in advanced ovarian cancer identifies a survival factor: Microfibril-associated glycoprotein 2. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kadioglu O, Saeed M, Kuete V, Greten HJ, Efferth T. Oridonin targets multiple drug-resistant tumor cells as determined by in silico and in vitro analyses. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:355. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li L, Wang G, Li N, Yu H, Si J, Wang J. Identification of key genes and pathways associated with obesity in children. Exp Ther Med. 2017;14:1065–1073. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Z, Zhou Y, Cao Y, Dinh TL, Wan J, Zhao M. Identification of candidate biomarkers and analysis of prognostic values in ovarian cancer by integrated bioinformatics analysis. Med Oncol. 2016;33:130. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0840-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang B, Li C, Zhao J. Identification of key pathways and genes in colorectal cancer using bioinformatics analysis. Med Oncol. 2016;33:111. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0829-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bader GD, Hogue CW. An automated method for finding molecular complexes in large protein interaction networks. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carl-McGrath S, Lendeckel U, Ebert M, Röcken C. Ectopeptidases in tumor biology: A review. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:1339–1353. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cordero OJ, Ayude D, Nogueira M, Rodriguez-Berrocal FJ, de la Cadena MP. Preoperative serum CD26 levels: Diagnostic efficiency and predictive value for colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;83:1139–1146. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikeda N, Nakajima Y, Tokuhara T, Hattori N, Sho M, Kanehiro H, Miyake M. Clinical significance of aminopeptidase N/CD13 expression in human pancreatic carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1503–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami H, Yokoyama A, Kondo K, Nakanishi S, Kohno N, Miyake M. Circulating aminopeptidase N/CD13 is an independent prognostic factor in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8674–8679. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Larrinaga G, Blanco L, Sanz B, Perez I, Gil J, Unda M, Andrés L, Casis L, López JI. The impact of peptidase activity on clear cell renal cell carcinoma survival. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F1584–F1591. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00477.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McDonnell DP, Park S, Goulet MT, Jasper J, Wardell SE, Chang CY, Norris JD, Guyton JR, Nelson ER. Obesity, cholesterol metabolism, and breast cancer pathogenesis. Cancer Res. 2014;74:4976–4982. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin CY, Huo C, Kuo LK, Hiipakka RA, Jones RB, Lin HP, Hung Y, Su LC, Tseng JC, Kuo YY, et al. Cholestane-3β, 5α, 6β-triol suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion of human prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65734. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murtola TJ, Visvanathan K, Artama M, Vainio H, Pukkala E. Statin use and breast cancer survival: A nationwide cohort study from finland. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardwell CR, Hicks BM, Hughes C, Murray LJ. Statin use after colorectal cancer diagnosis and survival: A population-based cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3177–3183. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.4569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jacobs EJ, Newton CC, Thun MJ, Gapstur SM. Long-term use of cholesterol-lowering drugs and cancer incidence in a large United States cohort. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1763–1771. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhuo H, Lyu Z, Su J, He J, Pei Y, Cheng X, Zhou N, Lu X, Zhou S, Zhao Y. Effect of lung squamous cell carcinoma tumor microenvironment on the CD105+ endothelial cell proteome. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4717–4729. doi: 10.1021/pr5006229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han B, Nakamura M, Mori I, Nakamura Y, Kakudo K. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator system and breast cancer (Review) Oncol Rep. 2005;14:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsunoda T, Nakamura T, Ishimoto K, Yamaue H, Tanimura H, Saijo N, Nishio K. Upregulated expression of angiogenesis genes and down regulation of cell cycle genes in human colorectal cancer tissue determined by cDNA macroarray. Anticancer Res. 2001;21:137–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romero-Cordoba SL, Salido-Guadarrama I, Rodriguez-Dorantes M, Hidalgo-Miranda A. miRNA biogenesis: Biological impact in the development of cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2014;15:1444–1455. doi: 10.4161/15384047.2014.955442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perez R, Wu N, Klipfel AA, Beart RW., Jr A better cell cycle target for gene therapy of colorectal cancer: Cyclin G. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:884–889. doi: 10.1007/s11605-003-0034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tominaga O, Nita ME, Nagawa H, Fujii S, Tsuruo T, Muto T. Expressions of cell cycle regulators in human colorectal cancer cell lines. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2003;88:855–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1997.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Berg YW, Osanto S, Reitsma PH, Versteeg HH. The relationship between tissue factor and cancer progression: Insights from bench and bedside. Blood. 2012;119:924–932. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-317685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pesson M, Volant A, Uguen A, Trillet K, De La Grange P, Aubry M, Daoulas M, Robaszkiewicz M, Le Gac G, Morel A, et al. A gene expression and pre-mRNA splicing signature that marks the adenoma-adenocarcinoma progression in colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87761. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai TH, Song E, Zhu R, Di Poto C, Wang M, Luo Y, Varghese RS, Tadesse MG, Ziada DH, Desai CS, et al. LC-MS/MS-based serum proteomics for identification of candidate biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Proteomics. 2015;15:2369–2381. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turati F, Talamini R, Pelucchi C, Polesel J, Franceschi S, Crispo A, Izzo F, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P, Montella M. Metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:222–228. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baffy G, Brunt EM, Caldwell SH. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An emerging menace. J Hepatol. 2012;56:1384–1391. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boroughs LK, DeBerardinis RJ. Metabolic pathways promoting cancer cell survival and growth. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17:351–359. doi: 10.1038/ncb3124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang W, Huang H, Ding L, Zhu P, Saiyin H, Ji G, Zuo J, Han D, Pan Y, Ding D, et al. Regulation of cell cycle of hepatocellular carcinoma by NF90 through modulation of cyclin E1 mRNA stability. Oncogene. 2015;34:4460–4470. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clawson GA, Feldherr CM, Smuckler EA. Nucleocytoplasmic RNA transport. Mol Cell Biochem. 1985;67:87–99. doi: 10.1007/BF02370167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quesada-Calvo F, Massot C, Bertrand V, Longuespée R, Blétard N, Somja J, Mazzucchelli G, Smargiasso N, Baiwir D, De Pauw-Gillet MC, et al. OLFM4, KNG1 and Sec24C identified by proteomics and immunohistochemistry as potential markers of early colorectal cancer stages. Clin Proteomics. 2017;14:9. doi: 10.1186/s12014-017-9143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang J, Wang X, Lin S, Chen C, Wang C, Ma Q, Jiang B. Identification of kininogen-1 as a serum biomarker for the early detection of advanced colorectal adenoma and colorectal cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8:e70519. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wahab Abdel AHA, El-Halawany MS, Emam AA, Elfiky A, Elmageed Abd ZY. Identification of circulating protein biomarkers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma concomitantly infected with chronic hepatitis C virus. Biomarkers. 2017;22:621–628. doi: 10.1080/1354750X.2016.1252966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He X, Wang Y, Zhang W, Li H, Luo R, Zhou Y, Liao CL, Huang H, Lv X, Xie Z, He M. Screening differential expression of serum proteins in AFP-negative HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma using iTRAQ -MALDI-MS/MS. Neoplasma. 2014;61:17–26. doi: 10.4149/neo_2014_001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang C, Liu CM, Wei LL, Shi LY, Pan ZF, Mao LG, Wan XC, Ping ZP, Jiang TT, Chen ZL, et al. A group of novel serum diagnostic biomarkers for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis by iTRAQ-2D LC-MS/MS and solexa sequencing. Int J Biol Sci. 2016;12:246–256. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koch AE, Halloran MM, Haskell CJ, Shah MR, Polverini PJ. Angiogenesis mediated by soluble forms of E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1. Nature. 1995;376:517–519. doi: 10.1038/376517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Byrne GJ, Ghellal A, Iddon J, Blann AD, Venizelos V, Kumar S, Howell A, Bundred NJ. Serum soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1: Role as a surrogate marker of angiogenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1329–1336. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.16.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoong KF, McNab G, Hubscher SG, Adams DH. Vascular adhesion protein-1 and ICAM-1 support the adhesion of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes to tumor endothelium in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Immunol. 1998;160:3978–3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexiou D, Karayiannakis AJ, Syrigos KN, Zbar A, Kremmyda A, Bramis I, Tsigris C. Serum levels of E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in colorectal cancer patients: Correlations with clinicopathological features, patient survival and tumour surgery. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2392–2397. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kang X, Wang F, Xie JD, Cao J, Xian PZ. Clinical evaluation of serum concentrations of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in patients with colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4250–4253. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i27.4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Hanlon DM, Fitzsimons H, Lynch J, Tormey S, Malone C, Given HF. Soluble adhesion molecules (E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1) in breast carcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2002;38:2252–2257. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00218-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ho JW, Poon RT, Tong CS, Fan ST. Clinical significance of serum vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2014–2018. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Iliaz R, Akyuz U, Tekin D, Serilmez M, Evirgen S, Cavus B, Soydinc H, Duranyildiz D, Karaca C, Demir K, et al. Role of several cytokines and adhesion molecules in the diagnosis and prediction of survival of hepatocellular carcinoma. Arab J Gastroenterol. 2016;17:164–167. doi: 10.1016/j.ajg.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diaz-Sanchez A, Matilla A, Nunez O, Rincon D, Lorente R, Iacono Lo O, Merino B, Hernando A, Campos R, Clemente G, Bañares R. Serum level of soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and its association with severity of liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12:236–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scalici JM, Thomas S, Harrer C, Raines TA, Curran J, Atkins KA, Conaway MR, Duska L, Kelly KA, Slack-Davis JK. Imaging VCAM-1 as an indicator of treatment efficacy in metastatic ovarian cancer. J Nucl Med. 2013;54:1883–1889. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.112.117796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito Y, Azrolan N, O'Connell A, Walsh A, Breslow JL. Hypertriglyceridemia as a result of human apo CIII gene expression in transgenic mice. Science. 1990;249:790–793. doi: 10.1126/science.2167514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chan AW, Wong GL, Chan HY, Tong JH, Yu YH, Choi PC, Chan HL, To KF, Wong VW. Concurrent fatty liver increases risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:667–676. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhong DN, Ning QY, Wu JZ, Zang N, Wu JL, Hu DF, Luo SY, Huang AC, Li LL, Li GJ. Comparative proteomic profiles indicating genetic factors may involve in hepatocellular carcinoma familial aggregation. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1833–1838. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haukeland JW, Dahl TB, Yndestad A, Gladhaug IP, Løberg EM, Haaland T, Konopski Z, Wium C, Aasheim ET, Johansen OE, et al. Fetuin A in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: In vivo and in vitro studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:503–510. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yilmaz Y, Yonal O, Kurt R, Ari F, Oral AY, Celikel CA, Korkmaz S, Ulukaya E, Ozdogan O, Imeryuz N, et al. Serum fetuin A/α2HS-glycoprotein levels in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Relation with liver fibrosis. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:549–553. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao ZW, Lin CG, Wu LZ, Luo YK, Fan L, Dong XF, Zheng H. Serum fetuin-A levels are associated with the presence and severity of coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Biomarkers. 2013;18:160–164. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2012.762806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaushik SV, Plaisance EP, Kim T, Huang EY, Mahurin AJ, Grandjean PW, Mathews ST. Extended-release niacin decreases serum fetuin-A concentrations in individuals with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:427–434. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalabay L, Jakab L, Prohaszka Z, Füst G, Benkö Z, Telegdy L, Lörincz Z, Závodszky P, Arnaud P, Fekete B. Human fetuin/alpha2HS-glycoprotein level as a novel indicator of liver cell function and short-term mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis and liver cancer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:389–394. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Guillory B, Sakwe AM, Saria M, Thompson P, Adhiambo C, Koumangoye R, Ballard B, Binhazim A, Cone C, Jahanen-Dechent W, Ochieng J. Lack of fetuin-A (alpha2-HS-glycoprotein) reduces mammary tumor incidence and prolongs tumor latency via the transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway in a mouse model of breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2635–2644. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swallow CJ, Partridge EA, Macmillan JC, Tajirian T, DiGuglielmo GM, Hay K, Szweras M, Jahnen-Dechent W, Wrana JL, Redston M, et al. alpha2HS-glycoprotein, an antagonist of transforming growth factor beta in vivo, inhibits intestinal tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6402–6409. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xiang Y, Liu Y, Yang Y, Hu H, Hu P, Ren H, Zhang D. A secretomic study on human hepatocellular carcinoma multiple drug-resistant cell lines. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:1249–1260. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hyung SW, Lee MY, Yu JH, Shin B, Jung HJ, Park JM, Han W, Lee KM, Moon HG, Zhang H, et al. A serum protein profile predictive of the resistance to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced breast cancers. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(M111):011023. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.011023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kirschbaum MH, Yarden Y. The ErbB/HER family of receptor tyrosine kinases: A potential target for chemoprevention of epithelial neoplasms. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2000;34:52–60. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4644(2000)77:34+<52::AID-JCB10>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Slamon DJ, Godolphin W, Jones LA, Holt JA, Wong SG, Keith DE, Levin WJ, Stuart SG, Udove J, Ullrich A. Studies of the HER-2/neu proto-oncogene in human breast and ovarian cancer. Science. 1989;244:707–712. doi: 10.1126/science.2470152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Press MF, Pike MC, Chazin VR, Hung G, Udove JA, Markowicz M, Danyluk J, Godolphin W, Sliwkowski M, Akita R. Her-2/neu expression in node-negative breast cancer: Direct tissue quantitation by computerized image analysis and association of overexpression with increased risk of recurrent disease. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4960–4970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Colak D, Chishti MA, Al-Bakheet AB, Al-Qahtani A, Shoukri MM, Goyns MH, Ozand PT, Quackenbush J, Park BH, Kaya N. Integrative and comparative genomics analysis of early hepatocellular carcinoma differentiated from liver regeneration in young and old. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:146. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakopoulou L, Stefanaki K, Filaktopoulos D, Giannopoulou I. C-erb-B-2 oncoprotein and epidermal growth factor receptor in human hepatocellular carcinoma: An immunohistochemical study. Histol Histopathol. 1994;9:677–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hamazaki K, Yunoki Y, Tagashira H, Mimura T, Mori M, Orita K. Epidermal growth factor receptor in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Detect Prev. 1997;21:355–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Prange W, Schirmacher P. Absence of therapeutically relevant c-erbB-2 expression in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:727–730. doi: 10.3892/or.8.4.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Altimari A, Fiorentino M, Gabusi E, Gruppioni E, Corti B, D'Errico A, Grigioni WF. Investigation of ErbB1 and ErbB2 expression for therapeutic targeting in primary liver tumours. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:332–338. doi: 10.1016/S1590-8658(03)00077-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ito Y, Takeda T, Sakon M, Tsujimoto M, Higashiyama S, Noda K, Miyoshi E, Monden M, Matsuura N. Expression and clinical significance of erb-B receptor family in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1377–1383. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Misale S, Di Nicolantonio F, Sartore-Bianchi A, Siena S, Bardelli A. Resistance to anti-EGFR therapy in colorectal cancer: From heterogeneity to convergent evolution. Cancer Discov. 2014;4:1269–1280. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vaz J, Ansari D, Sasor A, Andersson R. SPARC: A potential prognostic and therapeutic target in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2015;44:1024–1035. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nagaraju GP, Dontula R, El-Rayes BF, Lakka SS. Molecular mechanisms underlying the divergent roles of SPARC in human carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2014;35:967–973. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgu072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lau CP, Poon RT, Cheung ST, Yu WC, Fan ST. SPARC and Hevin expression correlate with tumour angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Pathol. 2006;210:459–468. doi: 10.1002/path.2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Massi D, Franchi A, Borgognoni L, Reali UM, Santucci M. Osteonectin expression correlates with clinical outcome in thin cutaneous malignant melanomas. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:339–344. doi: 10.1016/S0046-8177(99)90014-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Golembieski WA, Ge S, Nelson K, Mikkelsen T, Rempel SA. Increased SPARC expression promotes U87 glioblastoma invasion in vitro. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1999;17:463–472. doi: 10.1016/S0736-5748(99)00009-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thomas R, True LD, Bassuk JA, Lange PH, Vessella RL. Differential expression of osteonectin/SPARC during human prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1140–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang T, Srivastava S, Hartman M, Buhari SA, Chan CW, Iau P, Khin LW, Wong A, Tan SH, Goh BC, Lee SC. High expression of intratumoral stromal proteins is associated with chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:55155–55168. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Seiffert D, Geisterfer M, Gauldie J, Young E, Podor TJ. IL-6 stimulates vitronectin gene expression in vivo. J Immunol. 1995;155:3180–3185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edwards S, Lalor PF, Tuncer C, Adams DH. Vitronectin in human hepatic tumours contributes to the recruitment of lymphocytes in an alpha v beta3-independent manner. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:1545–1554. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nejjari M, Hafdi Z, Gouyss G, Fiorentino M, Béatrix O, Dumortier J, Pourreyron C, Barozzi C, D'errico A, Grigioni WF, Scoazec JY. Expression, regulation, and function of alpha V integrins in hepatocellular carcinoma: An in vivo and in vitro study. Hepatology. 2002;36:418–426. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferrin G, Ranchal I, Llamoza C, Rodríguez-Perálvarez ML, Romero-Ruiz A, Aguilar-Melero P, López-Cillero P, Briceño J, Muntané J, Montero-Álvarez JL, De la Mata M. Identification of candidate biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in plasma of HCV-infected cirrhotic patients by 2-D DIGE. Liver Int. 2014;34:438–446. doi: 10.1111/liv.12277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ding Y, Shen Y. Notch increased vitronection adhesion protects myeloma cells from drug induced apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467:717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sun S, Poon RT, Lee NP, Yeung C, Chan KL, Ng IO, Day PJ, Luk JM. Proteomics of hepatocellular carcinoma: Serum vimentin as a surrogate marker for small tumors (<or=2 cm) J Proteome Res. 2010;9:1923–1930. doi: 10.1021/pr901085z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lazarova DL, Bordonaro M. Vimentin, colon cancer progression and resistance to butyrate and other HDACis. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20:989–993. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data and materials have been provided as part of the submitted article.