Abstract

Objectives

We aimed to analyze the outcomes of patients who underwent vulvectomy with subsequent V—Y fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction.

Methods

All medical records of all patients who underwent vulvectomies with V—Y fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction from January 2007 to June 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Patient clinical and surgical data, demographics, and outcomes were abstracted.

Results

Of the 27 patients, 42 flaps were transferred. A simple vulvectomy was performed in 8 (30%) patients, partial radical vulvectomy in 15 (56%), and radical vulvectomy in 4 (15%). The median area of defect was 30 cm2. Minor wound separations occurred in 9 patients (33%). Infectious complications occurred in 4 patients (15%); this included urinary tract infections in 2 (50%), postoperative fevers in 2 (50%), and sepsis in 1 (25%) patient with a UTI. There were no instances of flap necrosis, wound dehiscence, or wound infections. Black race was more likely to be associated with an infectious complication with 3 (75%) patients, compared to white race with 1 (4%) patient (p < .01). The presence of diabetes was more likely to be associated with an infectious complication in 2 (67%) patients, compared to 1 (4%) in non-diabetic patients (p < .01). No other significant association was found during analysis of demographics, medical comorbidities, vulvar pathology, or surgical factors affecting V—Y fasciocutaneous flap infectious complications or minor wound separations.

Conclusions

The use of a V—Y fasciocutaneous advancement flap for vulvar reconstruction is safe and associated with mostly minor complications. Infectious complications were more frequently associated with diabetes, black race, and HIV.

Highlights

-

•

A V—Y fasciocutaneous flap for vulvar reconstruction is a feasible alternative to primary closure.

-

•

Minor wound separations and infectious complications were most common.

-

•

It is a safe procedure with no instances of flap necrosis, wound dehiscence, or wound infections.

1. Introduction

Vulvar cancer is a rare gynecologic malignancy that comprises only 3–5% of all gynecologic neoplasms.(Judson et al., 2006; Carramaschi et al., 1999). In 2018, there will be an estimated 6190 new cases and 1200 deaths from vulvar cancer.(Siegel et al., 2018). Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the predominant tumor type and accounts for >90% of all cases.(Del Pino et al., 2013; Lazzaro et al., 2010)

Vulvar cancer and other vulvar pathologies are usually treated with an en bloc vulvectomy, due to the high rate of recurrence. Postoperative dehiscence, lymphocysts, and lymphedema rates have been reported as high as 64–85%.(Carramaschi et al., 1999). In recent years a modified approach has been used to decrease morbidity. Primary closure is possible, however tension placed on the site can result in extensive tissue breakdown and prolonged healing. Additionally, the aesthetic result can impair patient's sexual and urinary functions. Necrosis, dehiscence, and infections can all prolong hospitalization.

A variety of reconstructive techniques have been employed to reconstruct residual vulvectomy defects in an effort to decrease postoperative complications, length of hospital stay, and to improve patient satisfaction.(Carramaschi et al., 1999; McCraw et al., 1976; Lin et al., 1992). These reconstructive techniques include the use of skin grafts, local skin flaps, regional skin flaps, and distant skin flaps. Regional flaps utilize the tissue in the area of the defect but often do not about the defect. They are mostly myocutaneous and thus, tend to be bulky. These flaps result in increased operating time and high complication rates.(Carramaschi et al., 1999; McCraw et al., 1976; Chen et al., 1995). Distant flaps utilize tissue far from the defect. They can either be created with a vascular pedicle in order to leave the vascular supply anatomically connected, or harvested as free flaps with the vascular supply being interrupted and then reconnected.

The V—Y advancement flap is a local fasciocutaneous flap that involves mobilizing the adjacent skin and underlying subcutaneous tissue to cover the primary defect. The letter “V” represents the initial V-shaped incision that is created along the adjacent skin and underlying subcutaneous tissue that is mobilized over the primary vulvar defect. The letter “Y” represents how the skin is closed, with the tail denoting the primary closure of the harvested site. This technique can be used when the donor site has enough laxity to allow appropriate mobilization to cover the defect at the time of initial surgery.(Carramaschi et al., 1999; Tateo et al., 1996; Benedetti Panici et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2006). This is an ideal treatment as restoration can occur at the time of demolitive surgery and primary healing can occur. These flaps may be erythematous and edematous for weeks but should be in their final form at 3 to 6 months. It is also beneficial as similar skin characteristics can be found in the local flap. The aim of our study was to analyze the outcomes of patients who underwent vulvectomy with subsequent V—Y fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction from adjacent gluteal or medial thigh folds for a variety of vulvar pathologies at a single institution.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient population

The medical records of all patients who underwent a vulvectomy with V—Y fasciocutaneous flap reconstruction at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital (TJUH) from January 1, 2007 to June 1, 2016 were retrospectively reviewed after obtaining IRB approval. Demographic, surgical information, disease outcomes, and complications were abstracted. Patients without adequate medical records were excluded. All patients were given preoperative deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis with heparin as well as preoperative antibiotics. They were placed in dorsal lithotomy position, prepped with chlorahexadine and betadine, and had a Foley catheter placed. A gynecologic oncologist performed the first portion of the surgery, which ranged from a simple vulvectomy, partial radical vulvectomy, or radical vulvectomy plus unilateral or bilateral groin dissection, depending on pathology. A plastic surgeon performed the second portion of the surgery, a V—Y fasciocutaneous advancement flap from the adjacent gluteal or medial thigh folds. Unilateral or bilateral V—Y flap reconstruction was performed based on the size of the tumor and defect after primary excision. The wound was irrigated with antibiotic irrigation and the flaps were incised with a scalpel. The flap was mobilized down to the muscular fascia and elevated with undermining of the subcutaneous tissue. A JP drain, if necessitated by the size of defect, was placed beneath the flap and brought out anteriorly through the skin. The wound was closed in multiple layers with deep dermal sutures followed by a running subcuticular closure in order to prevent the most amount of tension. This is detailed in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. Postoperatively, patients were allowed to ambulate the morning after surgery. Sequential compression devices were used throughout the surgery and postoperatively in the hospital to prevent deep venous thrombosis. Prophylactic subcutaneous heparin was administered every 8 h, starting on postoperative day 1 during the hospital stay.

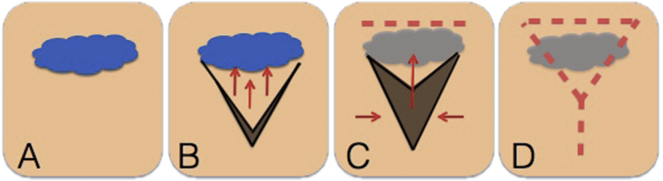

Fig. 1.

Creation of V—Y Fasciocutaneous Flap.

A. Initial defect in blue.

B. Initial V-shaped skin incision is made adjacent to the defect. Subcutaneous tissue underlying V is undermined.

C. V-shaped skin is mobilized over the primary vulvar defect, is mobilized and medial edge closed.

D. Apex of the V is closed linearly. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

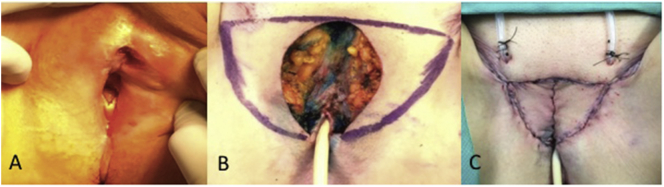

Fig. 2.

Radical vulvectomy with bilateral V—Y Fasciocutaneous Advancement Flaps.

Initial defect prior to surgical intervention.

After resection of the lesion with marked flaps to be excised.

Final appearance of bilateral flaps in place.

2.2. Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the characteristics of the patient population, surgical procedures, and surgical outcomes with medians, ranges, and frequencies. The associations between demographics, medical comorbidities, type of vulvar pathology, or surgical factors affecting V—Y fasciocutaneous flap minor wound separations and infectious complications were examined. t-tests were used to compare means of continuous variables or Mann-Whitney to compare medians if data was skewed. Chi Square or Fishers Exact test as appropriate were used for categorical variables. Data analysis was performed with STATA version 12 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Significance was defined as a P value <.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

During the study period from 2007 to 2016, 27 patients underwent vulvectomies with a total of 42 V-Y fasciocutaneous flap reconstructions at TJUH. Table 1 details patient demographics. The median age of patients was 69 years old, with a range of 25 to 93 years old. Twenty-two (81%) patients were Caucasian and 5 (19%) were black. Medical comorbidities included 3 (11%) patients with diabetes mellitus, 8 (30%) with hypertension, and 1 (4%) with HIV. Six patients (22%) were current or previous smokers.

Table 1.

Demographics and disease characteristics.

| Median (range) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 (25–93) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 (18–51) |

|

N = 27 n(%) |

|

| Race | |

| White | 22 (81) |

| Black | 5 (19) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 3 (11) |

| Hypertension | 8 (30) |

| HPV | 2 (7) |

| Lichen sclerosis | 5 (19) |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | 1 (4) |

| HIV | 1 (4) |

| Smoking | 6 (22) |

| Type of Surgery | |

| Simple Vulvectomy | 8 (30) |

| Partial Radical Vulvectomy | 15 (56) |

| Radical Vulvectomy | 4 (15) |

| Groin LN Dissection | 10 (37) |

| Anatomic location | |

| Anterior/Lateral Vulva | 17 (63) |

| Perineum/Posterior Vulva | 10 (37) |

| Laterality of surgery | |

| Unilateral | 12 (44) |

| Bilateral | 15 (56) |

| Malignant | |

| Cancer | 21(78) |

| Benign | 6 (22) |

| Pathology | |

| Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 17 (63) |

| Paget's | 2 (7) |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma | 1 (3) |

| Endometrial Adenocarcinoma | 1 (3) |

| Bartholin's cyst | 1 (3) |

| Hidradenitis Suppurativa | 1 (3) |

| Chronic abscess/fistula | 1 (3) |

| VIN III | 1 (3) |

| Vaginal Smooth Muscle Tumor | 1 (3) |

| Subepithelial Lymphangiectasia | 1 (3) |

| Stage of SCC (n = 17) | |

| Ia | 3 (18) |

| Ib | 9 (53) |

| II | 0 (0) |

| IIIa | 0 (0) |

| IIIb | 1 (5.9) |

| IIIc | 0 (0) |

| IV | 0 (0) |

| Recurrent | 4 (24) |

| Grade of SCC (n = 17) | |

| 1 | 5 (29) |

| 2 | 7 (41) |

| 3 | 5 (29) |

| Radiation | |

| Neoadjuvant | 2 (10) |

| Adjuvant | 3 (18) |

Kg/m2 = kilogram/m2

3.2. Surgical characteristics

As seen in Table 1, a simple vulvectomy was performed in 8 (30%) patients, partial radical vulvectomy in 15 (56%), and radical vulvectomy in 4 (15%). Inguinofemoral lymph node dissections were performed in 10 (37%) patients at the time of surgery. Median estimated blood loss was 50 mL and median total operative time was 179 min (Table 2). Median length of stay was 3 days. The median area of defect was 30 cm2. Drains at the site of vulvar reconstruction were used in 24 (89%) patients and a wound vacuum was placed prophylactically in 1 (4%) patient who had multiple prior surgeries. Drains were left in place for a median of 10 days, until the patient's postoperative visit with the plastic surgeon.

Table 2.

Surgical information.

| N = 27 n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Drains Used | 24 (89) |

| Wound Vac Used | 1 (4) |

| Median (range) | |

| Time Drains Used (days) | 10 (2–27) |

| Time Foley Left in (days) | 1 (0–7) |

| Area of Defect (cm2) | 30 (6–131) |

| EBL (mL) | 50 (5–400) |

| Total Operative Time (minutes) | 179 (50–315) |

| Hospital Stay (days) | 3 (1–7) |

cm2 = centimeter2, mL = milliliters, min = minute.

3.3. Stage of disease and tumor characteristics

Of the 27 patients, 21 (78%) had surgery for cancer (Table 1). Of these cancers, 17 (81%) were squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), 2 were due to Paget's Disease, 1 was a dermatofibrosarcoma, and 1 was a metastatic endometrial adenocarcinoma. Four (24%) of the SCC were recurrent at the time of surgery. The majority of the SCCs were Stage I, with 3 (18%) that were Stage Ia and 9 (53%) that were Stage Ib. The remaining patient had a Stage IIIb SCC of the vulva. Grade 2 disease was found in 7 (41%) patients.

3.4. Complications and disease outcomes

Primary wound healing complications occurred in 9 patients (33%) and included minor wound separations, or local scar defects. These are detailed in Table 3. Infectious complications occurred in 4 (15%) patients: 2 (50%) had urinary tract infections (UTI), 2 (50%) had postoperative fevers, one due to atelectasis and one due to an unknown cause, and 1 (25%) of the patients with a UTI was found to be septic. Foleys were left in place for a median of 1 day postoperatively. There were no instances of flap necrosis, wound dehiscence, or surgical site infections. There were no recurrences. One patient later died, unrelated to her disease. Four patients had chemoradiation: 2 in the neoadjuvant setting and 2 in the adjuvant setting. One patient had adjuvant vaginal brachytherapy alone.

Table 3.

Surgical complications.

| N = 27 n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Minor wound separations | 9 (33) |

| Postoperative fever | 2 (7) |

| Sepsis | 1 (4) |

| Urinary Tract Infection | 2 (7) |

| Lymphocele | 0 (0) |

| VTE/PE | 0 (0) |

| Surgical Site infection | 0 (0) |

| Dehiscence | 0 (0) |

| Flap necrosis | 0 (0) |

| Recurrence | 0 (0) |

| Death | 1 (4) |

3.5. Associations of infectious complications and minor wound separations

Of the four patients with infectious complications, 3 (75%) were black and 1 (25%) Caucasian (See Table 4). One (25%) patient smoked and 2 (50%) had diabetes. Black race was associated with an infectious complication in 3 patients (75%), compared to white race with 1 patient (4%) (p < .01). Additionally, the presence of diabetes was more likely to be associated with an infectious complication in 2 (67%) of the diabetic patients, compared to 1 (4%) of the non-diabetic patients (p < .01). HIV was also found to be associated with infectious complications (p < .01), with the 1 (100%) patient with HIV having an infectious complication. No association was found between other demographics, medical comorbidities, type of vulvar pathology, or surgical factors affecting V—Y fasciocutaneous flap infectious complications or minor wound separations. We had no instances of flap necrosis, wound dehiscence, or wound infections.

Table 4.

Analysis of minor infectious complications.

| Minor Infectious Complications n = 4 n (%) |

No infectious complications n = 23 n (%) |

P value⁎ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Black Race | 3 (75) | 2 (9) | <0.01 |

| Age (years, median (range)) | 67 (44–74) | 69 (25–93) | 0.84 |

| BMI (kg/m2, median (range)) | 26 (19–31) | 29 (18–51) | 0.25 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Smoker | 1 (25) | 5 (22) | 0.89 |

| Diabetes | 2 (50) | 1 (4) | <0.01 |

| Hypertension | 2 (50) | 6 (26) | 0.94 |

| HIV | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 0.02 |

| Lichen Sclerosis | 1 (25) | 4 (17) | 0.72 |

| Hidradenitis | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | 0.67 |

| HPV | 1 (25) | 1 (4) | 0.15 |

| Surgical factors | |||

| Radical Vulvectomy | 2 (50) | 2 (9) | 0.85 |

| Use of drains | 4 (100) | 20 (87) | 0.44 |

| OR Time (minutes, median (range)) | 219 (195–238) | 169 (50–315) | 0.17 |

| EBL (mL, median (range)) | 125 (20–250) | 50 (5–400) | 0.28 |

| Area of defect (cm2, median (range)) | 29 (23–61) | 36 (6–131) | 1.00 |

| Pathology | |||

| Cancer | 3 (75) | 18 (78) | 0.89 |

kg/m2 = kilogram/m2, mL = milliliters, cm2 = centimeter2.

For continuous variables, a t-test was performed unless data was not normally distributed when a Mann-Whitney test performed. For categorical data Chi Square or Fishers Exact test were used as appropriate.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the overall feasibility and safety of using a V—Y fasciocutaneous advancement flap from adjacent tissue for primary vulvar reconstruction for patients with vulvar pathologies. Demolitive vulvar surgery can be extensive and reconstruction is important in improving quality of life and reducing complications. The use of a V—Y fasciocutaneous advancement flap for vulvar reconstruction is safe and associated with minor complications in most situations.

Minor wound separations, dehiscence, and necrosis have been reported in the literature, however, in our patient population, there were only 9 local scar defects which all healed conservatively.(Lazzaro et al., 2010). Infectious complications, including urinary tract infections and fevers postoperatively only occurred in 4 patients, with one patient developing sepsis from the UTI. We found diabetes, black race, and HIV to be associated with infectious complications. The presence of both diabetes and HIV have been shown to lead to infectious complication. (Dryden et al., 2015; Knapp, 2013). It is, however, unclear why black race led to an increase in infectious complications. We also did not find any demographic or surgical factors associated with minor wound separations. Given the small number of patients and complications, a larger sample size would be useful to further investigate these associations.

In the literature, there is a low rate of dehiscence after vulvectomy with V—Y fasciocutaneous advancement flaps. In one series of 17 gluteal fold flaps in 9 patients, small wound disruptions occurred in 3 patients, which healed conservatively. There was no necrosis. (Lee et al., 2006). In a case series of 8 patients with 16 gluteal fold V—Y advancement flaps, 1 patient had marginal flap necrosis. (Lazzaro et al., 2010). In another case series of 21 patients, with 36 V-Y advancement flaps, local scar defect was noted in 16 patients (76%). The defects were <10 cm in 10 patients. No necrosis of the flaps were observed.(Conri et al., 2016). Additionally, in another case series of 5 patients with 7 V-Y advancement flaps, one patient had partial dehiscence after surgery. (Nakamura et al., 2010)

Conri et al. found V—Y suprafascial gluteal advancement flaps to be safe options for a reliable reconstruction of vulvar defects despite ASA score, age, or BMI.(Conri et al., 2016). Their cohort of patients was operated and cared for in the French healthcare system and the patients remained in the hospital until local scar defects were healed to allow for inpatient postoperative nursing care. They commented that tension free repairs spent half the time in the hospital.(Conri et al., 2016). In our cohort of patients in the U.S., median hospital stay was 3 days. All local scar defects were managed as outpatients and healed without need for reoperation.

One limitation of this series of cases is the lack of controls for comparison. However, in a recent study, the use of a V—Y gluteal fold advancement flap for large vulvectomy sites (> 4 cm) showed a statistically significant reduction in wound dehiscence compared to demolitive only surgeries.(Benedetti Panici et al., 2014). Compared to patients with large resections, the wound dehiscence rate was reduced from 40% to 10.3%. Median post-operative hospital stay was reduced to 3 days and 90% had good primary healing. Only 3 patients had complications, none with necrosis.(Benedetti Panici et al., 2014). Another study looked at patients who either had a traditional extensive vulvectomy and inguinal lymphadenectomy with either primary closure of the wound, local advancement flaps, or skin grafts compared to patients followed prospectively with a modified triple incision radical vulvectomy and inguinal lymphadenectomy followed by immediate V—Y flaps from the upper inner thighs.(Carramaschi et al., 1999). The perineal and inguinal dehiscence rates in the traditional approach were 68.4% and 78.9% compared to 10.5% and 36.8% in the modified approach.(Carramaschi et al., 1999)

A recent systematic review looked at the complication rates and feasibility of using reconstructive flaps after vulvovaginal malignancies.(Di Donato et al., 2017). They included 24 studies and found the majority of flaps were either advancement flaps or transpositional flaps with similar complication rates: 26.7% vs 22.3%, respectively. Of the 11 advancement flap studies they included, only 165 patients were included, further solidifying the need for further research related to this technique.(Di Donato et al., 2017). Finally, a retrospective single institution series looked at 234 patients undergoing a V—Y advancement flap compared to 128 undergoing a lotus petal flap (LPF) after demolitive surgery for vulvar malignancies.(Confalonieri et al., 2017) Wound infection, flap dehiscence, or local flap ischemia only occurred in 21% of the V—Y flaps and 13% of the LPF flaps. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups and the study concluded both are valid techniques for reconstruction.(Confalonieri et al., 2017)

When deciding between advancement or transposition fasciocutaneous flaps, the size and aesthetic results should be taken into consideration.(Di Donato et al., 2017; Confalonieri et al., 2017). Both have low complication rates however expertise in surgical dissection of the vessels is necessary for transposition flaps. Some institutions prefer transposition flaps due to the aesthetic results with less scarring compared to the V—Y. (Confalonieri et al., 2017). Moderate to large sized defects often require an advancement flap as less tension is placed on the wound.(Di Donato et al., 2017)

Overall, our study supports the ease and feasibility of using V—Y advancement flaps in the immediate reconstruction of vulvar defects. It is a simple and easy procedure with few complications in most cases.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author contribution statement

Drs. Hand, Rosenblum, and Kim created the idea for this project and the structure of the article. Data collection was completed by Dr. Hand, Dr. Maas, and Nadia Baka and reviewed by Dr. Kim. Drs. Hand and Mercier performed statistical analysis. All authors were involved in preparation and review of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Lauren C. Hand, Email: HandLC@upmc.edu.

Talia M. Maas, Email: Talia.Maas@jefferson.edu.

Nadia Baka, Email: Nadia.Baka@jefferson.edu.

Rebecca J. Mercier, Email: Rebecca.Mercier@jefferson.edu.

Patrick J. Greaney, Email: Patrick.Greaney@jefferson.edu.

Norman G. Rosenblum, Email: Norman.Rosenblum@jefferson.edu.

Christine H. Kim, Email: christine.kim@jefferson.edu.

References

- Benedetti Panici P., Di Donato V., Bracchi C., Marchetti C., Tomao F., Palaia I. Modified gluteal fold advancement V-Y flap for vulvar reconstruction after surgery for vulvar malignancies. Gynecol. Oncol. 2014;132(1):125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carramaschi F., Ramos M.L.C., Nisida A.C.T., Ferreira M.C., Pinotti J.A. V-Y flap for perineal reconstruction following modified approach to vulvectomy in vulvar cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 1999;65(2):157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(99)00016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.H.T., Hentz V.R., Wei F.C., Chen Y.R. Short gracilis myocutaneous flaps for vulvoperineal and inguinal reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1995;95(2):372–377. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199502000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Confalonieri P.L., Gilardi R., Rovati L.C., Ceccherelli A., Lee J.H., Magni S. Comparison of V-Y Advancement Flap Versus Lotus Petal Flap for Plastic Reconstruction after Surgery in Case of Vulvar Malignancies: a Retrospective Single Center experience. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2017;79(2):186–191. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conri V., Casoli V., Coret M., Houssin C., Trouette R., Brun J.L. Modified gluteal fold V-Y advancement flap for reconstruction after radical vulvectomy. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2016;26(7):1300–1306. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Pino M., Rodriguez-Carunchio L., Ordi J. Pathways of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2013;62:161–175. doi: 10.1111/his.12034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Donato V., Bracchi C., Cigna E., Domenici L., Musella A., Giannini A. Vulvo-vaginal reconstruction after radical excision for treatment of vulvar cancer: Evaluation of feasibility and morbidity of different surgical techniques. Surg. Oncol. 2017;26:511–521. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryden M., Baguneid M., Eckmann C., Corman S., Stephens J., Solem C. Pathophysiology and burden of infection in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral vascular disease: Focus on skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015;21:S27–S32. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judson P.L., Habermann E.B., Baxter N.N., Durham S.B., Virnig B.A. Trends in the incidence of invasive and in situ vulvar carcinoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006;107(5):1018–1022. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000210268.57527.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp S. Diabetes and infection: is there a link?--a mini-review. Gerontology. 2013;59(2):99–104. doi: 10.1159/000345107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzaro L., Guarneri G.F., Rampino Cordaro E., Bassini D., Revesz S., Borgna G. Vulvar reconstruction using a “v-Y” fascio-cutaneous gluteal flap: a valid reconstructive alternative in post-oncological loss of substance. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2010;282(5):521–527. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1603-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee P.K., Choi M.S., Ahn S.T., Oh D.Y., Rhie J.W., Han K.T. Gluteal fold V-Y advancement flap for vulvar and vaginal reconstruction: a new flap. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;118(2):401–406. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227683.47836.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J.Y., Dubeshter B., Angel C., Dvoretsky P.M. Morbidity and recurrence with modifications of radical vulvectomy and groin dissection. Gynecol. Oncol. 1992;47(1):80–86. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(92)90081-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCraw J.B., Massey F.M., Shanklin K.D., Horton C.E. Vaginal reconstruction with gracilis myocutaneous flaps. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1976;58(2):176–183. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197608000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura Y., Ishitsuka Y., Nakamura Y., Xu X., Hori-Yamada E., Ito M. Modified gluteal-fold flap for the reconstruction of vulvovaginal defects. Int. J. Dermatol. 2010;49(10):1182–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin [Internet]. 2018;68(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tateo A., Tateo S., Bernasconi C., Zara C. Use of V-Y flap for vulvar reconstruction. Gynecol. Oncol. 1996;62(2):203–207. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1996.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]