Abstract

Patients with toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) are known to experience various complications. Although pulmonary complications are commonly observed, they typically manifest in an acute form. By contrast, chronic complications are quite rare, and little is known with regard to their incidences or clinical manifestations. The present study reports the case of a 29-year-old female patient who suffered from TEN. At the onset of the disease, the patient exhibited no pulmonary impairment; however, 1 month after recovering from TEN, the patient developed severe obstruction and a mild diffusion defect. A diagnosis of bronchiolitis obliterans was determined, and the patient was treated with antibiotics, inhaled corticosteroids, anticholinergic agents, and bronchodilators. At the last follow-up, the patient was alive, but with a stable airway obstruction.

Keywords: chronic pulmonary complications, toxic epidermal necrolysis

Introduction

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) are severe drug-induced diseases characterized by the detachment of large areas of the epidermis and mucous membranes (1,2). According to the area of epidermal detaching in affected patients, disease severity ranges from SJS (<10% of the body surface area) to TEN/SJS overlap (10–30% of the body surface area) to TEN (>30% of the body surface area) (1–3). SJS and TEN are rare, but potentially life-threatening, disorders. It is reported that the mortality rates at 6 weeks for SJS, TEN/SJS overlap, and SJS are 12, 29 and 46%, respectively (4). The well-known chronic symptoms of TEN/SJS include ocular and cutaneous sequelae and mucosal involvement (5). In clinical practice, acute pulmonary complications are frequently observed in association with TEN/SJS. However, chronic forms of pulmonary complications are rare, and little is known regarding the prognosis, incidence and clinical manifestations of patients with chronic complications.

The present study reports the case of a patient with TEN who subsequently developed chronic bronchitis with severe obstructive ventilatory impairment and bronchiectasis. In addition, a review of the relevant literature is presented.

Case report

A 29-year-old Chinese woman with a chronic cough, sputum production and a large number of red papules and erythemas was referred to the Department of Dermatology, Ruijin Hospital (Shanghai, China) for evaluation and treatment in April 2009. The patient presented with a sore throat for 2 days and had self-administered azithromycin (0.25 g) before being admitted to hospital. However, several h after taking azithromycin, the patient had rapidly developed a high fever (40°C) and facial erythema. By the following day, the rash had spread to the trunk, back, upper arms and thighs; this was immediately followed by the development of large flaccid bullae, erythema and vesicular lesions of the mouth, eyes and vulva. The erosion involved 60–70% of the patient's body in a short period of time. Subsequently, a diagnosis of TEN was established. Physical examination revealed that the lungs were clear, without any expiratory rhonchi. Clubbing was absent, heart sounds were normal, and Nikolsky's sign was positive. A chest X-ray scan was taken once the patient was administered to hospital and demonstrated no abnormalities. Following the diagnosis of TEN, administration of methylprednisolone was given to the patient immediately and initiated at 1 mg/kg per day. After 3 days, the symptoms deteriorated and the bullae ruptured, producing large areas of detached skin on the face, trunk and upper arms. Therefore, the methylprednisolone dose was increased to 2 mg/kg per day, and the patient began to improve at ~10 days after initiation of the treatment. At 11 days after the onset of TEN, the patient began to cough, producing scant mucus-like sputum. Pathological examination of the lung tissue was not performed due to hypoxia. Re-epithelialization was evident and complete on day 37 after administration and the patient was then asymptomatic and discharged from hospital. After intensive therapy, the patient recovered from TEN, but scars remained and the patient suffered from severe symblepharon.

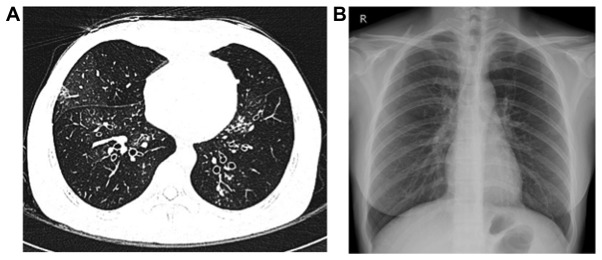

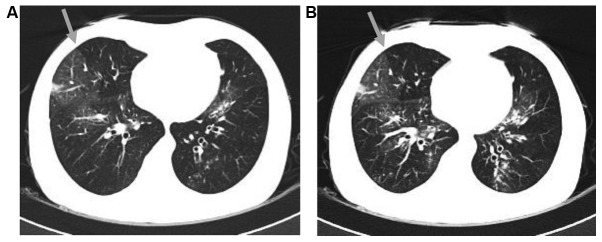

However, 1 month after the release from hospital the patient developed dyspnea and a productive cough. The patient was then presented to Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China). Blood gas examination revealed hypoxemia [partial pressure of O2, 73 mmHg (normal range, 80–100 mmHg); partial pressure of CO2, 39 mmHg (normal range, 35–45 mmHg)], and pulmonary function tests demonstrated severe obstruction, with a forced expiratory volume in 1 sec (FEV1) of 21.5%, FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) of 46.6%, and a mild diffusion defect [FEV1, 0.45 liters (15% of predicted value); FVC, 42% of predicted value]. The single-breath diffusing capacity of the lungs for CO2CO (DLCO) was 12.5 ml/mmHg/min (68% of the predicted value), while the DLCO divided by the alveolar volume was 5.67 ml/mmHg/min (123% of the predicted value). Furthermore, bronchodilation examination indicated non-reversible obstruction. A chest high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scan demonstrated central bronchiectasis (Fig. 1). Subsequently, a chest CT with inspiratory and expiratory images was further conducted to evaluate these findings. In the inspiratory image (Fig. 2A), a heterogeneous opacity was visible in a mosaic or patchy pattern. The expiratory image (Fig. 2B) revealed an area of trapped air in the lung, showing an attenuated intensity compared with the adjacent normal lung. These results, including a respiratory function test and radiological examination, were highly suggestive of bronchiolitis obliterans (BO).

Figure 1.

(A) Chest high-resolution computed tomography scan and (B) chest X-ray conducted following recovery from toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Figure 2.

(A) Inspiratory CT scan demonstrating mosaic attenuation at the upper lobes of the two lungs. An area of decreased attenuation in the right lobe is demarcated by the gray arrow. (B) Expiratory CT, performed at approximately the same level as the inspiratory image. The area of decreased attenuation in the right lobe remained lucent on expiration (gray arrow). CT, computed tomography.

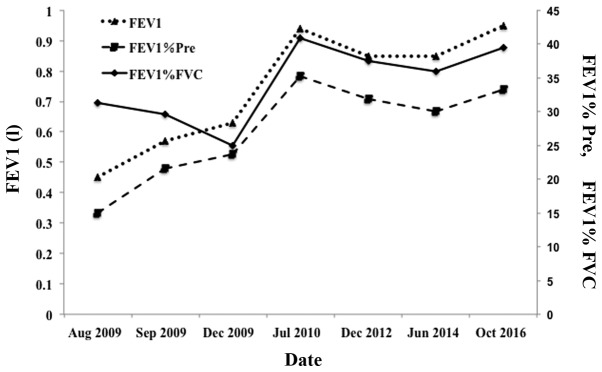

Therefore, the diagnosis of BO was established, and tiotropium bromide powder (18 µg, inhalation) and salmeterol xinafoate and fluticasone propionate powder (50/250 µg, inhalation) were administered. After 1 month, the FEV1 increased to 0.57 liters (21.5% of predicted), and the FVC was 64.8% of the predicted value. Furthermore, after 1 year, the FEV1 increased to 0.94 liters (35.3% of predicted), the FEV1/FVC was 40.81% and the FVC was 76.1% of the predicted value. At June 2017, 8 years after the onset of the disease, the patient was alive. Pulmonary function examinations demonstrated stability with the long-term use of long-acting β2-agonists and inhaled corticosteroids (Fig. 3). However, the patient did not recover completely and suffered from a chronic cough, hypersecretion of sputum (with occasional blood) and exertional dyspnea at the latest follow-up.

Figure 3.

Results of lung function tests of the patient following the development of chronic pulmonary complications. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 sec; FVC, forced vital capacity; Pre, predicted.

Discussion

Chronic pulmonary complications resulting from TEN and SJS are rare. According to previous studies published in English, 22 patients who suffered from chronic pulmonary diseases following TEN/SJS were identified, including the present case (6–24). The age of patients ranged between 2 and 52 years, and there were 10 male and 12 female patients (Table I). Therefore, it appears that chronic pulmonary diseases induced by TEN/SJS are likely to occur at a younger age, and that there is no significant prevalence associated with the patients' sex.

Table I.

Chronic pulmonary complications resulting from toxic epidermal necrolysis/Stevens-Johnson syndrome in cases described in the present and previous studies.

| First author | Age (years/sex) | Early pulmonary symptoms | Chronic pulmonary complication | Treatments | Outcome/time after onset | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taguchi et al | 53/M | − | BO | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/26 months | (6) |

| Date et al | 13/M | + | BO | Living-donor lobar lung transplantation | Alive/11 months | (7) |

| Minamihaba et al | 24/F | + | Bronchial obstruction | Steroid, bronchodilator, reopen by balloon catheter | Succumbed/1.3 years | (8) |

| Kim and Lee | 10/M | N/A | BO, bronchiectasis | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/1.8 years | (9) |

| Kim and Lee | 6/F | + | BO, bronchiectasis | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/2 years | (9) |

| Yatsunami et al | 25/M | + | BO, bronchiectasis | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/1 year | (10) |

| Edell et al | 8/F | − | Bronchial obliteration | Steroid, bronchodilator | Alive/7 months | (11) |

| Martín Mateos et al | 5/F | N/A | Chronic bronchitis, pneumopathy with deficit pulmonary perfusion | N/A | Alive/3 years | (12) |

| Tsunoda et al | 41/F | + | BO | Steroid, bronchodilator | Succumbed/2 months | (13) |

| Reyes de la Rocha et al | 15/F | + | Obstructive pulmonary disease | Steroid, bronchodilator | Alive/1.1 years | (14) |

| Virant et al | 2/F | + | Interstitial lung disease | Antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/1.5 months | (15) |

| Edwards et al | 8/M | + | Chronic obliterative bronchitis | Steroid, bronchodilator | Succumbed/9 months | (16) |

| Schønheyder | 8/M | + | Bronchiolar obstruction | Steroid, bronchodilator | Succumbed/3.5 months | (17) |

| McIvor et al | 40/F | + | BOOP | N/A | Succumbed/3 months | (18) |

| Kamada et al | 33/M | + | Chronic bronchitis, bronchiectasis | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Succumbed/1.5 years | (19) |

| Bakirtas et al | 8/M | − | BO | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/15 months | (20) |

| Bakirtas et al | 13/M | − | BO | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/3 months | (20) |

| Thimmesch et al | 3/F | N/A | BO | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/7 years | (21) |

| Yang et al | N/A | + | Interstitial lung disease | Steroid | Alive/1 year | (22) |

| Shah et al | 13/F | + | Constrictive bronchiolitis | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/2 years | (23) |

| Woo et al | 29/F | − | Obliterative bronchitis | Steroid, immunosuppressants (cyclosporine), antibiotics | Succumbed/1.7 years | (24) |

| Present case | 29/F | + | BO | Steroid, antibiotics, bronchodilator | Alive/8 years | N/A |

BO, bronchiolitis obliterans; BOOP, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia; +, present; -, absent; N/A, not available/applicable.

In the published literature, the precise interval between the onset of TEN/SJS and the development of complications was unknown. Certain patients developed chronic respiratory symptoms after 1 month, while other patients developed these symptoms after 1 week. However, the majority (13 out of 22 patients) demonstrated early pulmonary symptoms, including wheezing, dyspnea, hypoxia or bloody sputum. In the present case, the patient experienced dyspnea and hypoxia soon after the onset of TEN. Following treatment with short-term, high-dose corticosteroid therapy, the patient became asymptomatic, but then began to suffer from severe respiratory obstruction 1 month later. On the basis of these observations, it is suggested that the presence of early pulmonary symptoms should prompt close monitoring for possible delayed complications in these patients. However, the severity of the chronic pulmonary symptoms does not appear to be correlated with the severity of early pulmonary symptoms.

TEN and SJS are reported to be causes of several types of chronic pulmonary complications (6–24). In the current literature review, BO was observed in 10 cases, respiratory tract obliteration/obstruction was present in 5 cases, bronchiectasis in 4 cases, chronic (obliterative) bronchitis in 4 cases, interstitial lung disease in 2 cases, while BO organizing pneumonia (BOOP), obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumopathy with pulmonary perfusion deficit were each observed in 1 case. These cases demonstrated that the most common manifestations of chronic pulmonary complications associated with SJS or TEN are chronic bronchitis/bronchiolitis with obstructive impairment (including BO and BOOP), bronchiectasis and respiratory tract obstruction. In the present case, the patient presented BO with a severe obstructive ventilatory impairment. Several diseases can cause BO, and the known causes include connective tissue disorders (the most common factor), infections, inhalational injury, drugs and organ transplantation among others (25). In the current case, the patient did not have any rheumatologic manifestations. Upon referral to Zhongshan Hospital, the patient's lungs were clear, viral antibody tests were negative, while no abnormalities were identified on the chest X-ray scans. The patient had not previously suffered from chronic cough, and had no history of asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchiectasis or organ transplantation. Therefore, it is suggested that TEN was responsible for the development of BO in the present case.

In previous studies (13,17,18), the prognoses of chronic pulmonary complications resulting from TEN/SJS were considered to be poor. Considering all the relevant studies published to date that were identified by the present study, 4 patients who suffered from chronic pulmonary complications from TEN/SJS succumbed to the disease within 1 year, and a further 3 patients succumbed within 2 years, whereas 4 patients survived for >2 years and 1 patient survived for >7 years. In the present case, the patient survived for >8 years. Although the patient suffered from chronic severe obstruction, the lung function (FEV1 and FEV1% predicted) was slightly improved, which may be due to the alleviation of the inflammatory response by long-term use of inhalation of corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist. Thus, it appears that it is possible for such patients to survive for a long time, and the prognosis of patients with chronic pulmonary complications is not necessarily poor.

Treatment of chronic pulmonary complications mainly includes the administration of antibiotics, bronchodilators and steroids; however, these treatments do not reverse the deterioration of the pulmonary function (6). A living-donor lobar lung transplantation was performed in 1 previous case and presented good results (7). Reopening of the obstructed bronchi using a balloon catheter under the guidance of fiber-optic bronchoscopy was also applied in 1 patient who developed BO following TEN (8). However, rapid restenosis of the bronchi occurred, leading to the hypothesis that inflammatory responses may persist for a prolonged period subsequent to the onset of TEN/SJS. However, in the present case, the results of follow-up pulmonary function examinations following the development of chronic pulmonary complications suggested that inflammatory responses are likely to generally improve during the chronic phase of pulmonary complications (Fig. 3).

In conclusion, not only skin, but also respiratory tract is simultaneously injured in TEN. Therefore, physicians should be alert not only of acute symptoms but also the chronic pulmonary complications. The majority of patients with TEN/SJS generally experience deteriorating pulmonary function, rather than improvement. Therefore, when patients begin to present persistent pulmonary difficulties, early, intense and sustained treatment should be administered. This may maintain or even slightly improve the patient's pulmonary function. Therefore, close monitoring, including pulmonary function examinations and HRCT, is advised for patients with TEN/SJS.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81401877), the Program for Young Talents of Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (grant no. 2015ZSYXQN18) and the Shanghai Three-Year Plan of the Key Subjects Construction in Public Health-Infectious Diseases and Pathogenic Microorganism (grant no. 15GWZK0102).

References

- 1.Mawson AR, Eriator I, Karre S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis (SJS/TEN): Could retinoids play a causative role? Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:133–143. doi: 10.12659/MSM.891043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Letko E, Papaliodis DN, Papaliodis GN, Daoud YJ, Ahmed AR, Foster CS. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2005;94(419–438):456. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61112-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92–96. doi: 10.1001/archderm.129.1.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sekula P, Dunant A, Mockenhaupt M, Naldi L, Bavinck Bouwes JN, Halevy S, Kardaun S, Sidoroff A, Liss Y, Schumacher M, et al. Comprehensive survival analysis of a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1272–1285. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411103311906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taguchi S, Furuta J, Ohara G, Kagohashi K, Satoh H. Severe airflow obstruction in a patient with ulcerative colitis and toxic epidermal necrolysis: A case report. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:1944–1946. doi: 10.3892/etm.2015.2307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Date H, Sano Y, Aoe M, Goto K, Tedoriya T, Sano S, Andou A, Shimizu N. Living-donor lobar lung transplantation for bronchiolitis obliterans after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:389–391. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minamihaba O, Nakamura H, Sata M, Inage M, Shirakabe M, Tanida H, Osada Y, Kondo S, Tomoike H. Progressive bronchial obstruction associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis. Respirology. 1999;4:93–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.1999.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MJ, Lee KY. Bronchiolitis obliterans in children with Stevens-Johnson syndrome: Follow-up with high resolution CT. Pediatr Radiol. 1996;26:22–25. doi: 10.1007/BF01403698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yatsunami J, Nakanishi Y, Matsuki H, Wakamatsu K, Takayama K, Kawasaki M, Ogino H, Hashimoto S, Hara N. Chronic bronchobronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Intern Med. 1995;34:772–775. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.34.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edell DS, Davidson JJ, Muelenaer AA, Majure M. Unusual manifestation of Stevens-Johnson syndrome involving the respiratory and gastrointestinal tract. Pediatrics. 1992;89:429–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mateos Martín MA, Polemeque A, Pastor X, Muñoz López F. Uncommon serious complications in Stevens-Johnson syndrome: A clinical case. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 1992;2:278–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsunoda N, Iwanaga T, Saito T, Kitamura S, Saito K. Rapidly progressive bronchiolitis obliterans associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Chest. 1990;98:243–245. doi: 10.1378/chest.98.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de la Rocha Reyes S, Leonard JC, Demetriou E. Potential permanent respiratory sequela of Stevens-Johnson syndrome in an adolescent. J Adolesc Health Care. 1985;6:220–223. doi: 10.1016/S0197-0070(85)80022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virant FS, Redding GJ, Novack AH. Multiple pulmonary complications in a patient with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 1984;23:412–414. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edwards C, Penny M, Newman J. Mycoplasma pneumonia, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and chronic obliterative bronchitis. Thorax. 1983;38:867–869. doi: 10.1136/thx.38.11.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schønheyder H. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with intrahepatic cholestasis and respiratory disease: A case report. Acta Derm Venereol. 1981;61:171–173. doi: 10.2340/0001555561171173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McIvor RA, Zaidi J, Peters WJ, Hyland RH. Acute and chronic respiratory complications of toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1996;17:237–240. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199605000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamada N, Kinoshita K, Togawa Y, Kobayashi T, Matsubara H, Kohno M, Igari H, Kuriyama T, Nakamura M, Hirasawa H, Shinkai H. Chronic pulmonary complications associated with toxic epidermal necrolysis: Report of a severe case with anti-Ro/SS-A and a review of the published work. J Dermatol. 2006;33:616–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2006.00142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakirtas A, Harmanci K, Toyran M, Razi CH, Turktas I. Bronchiolitis obliterans: A rare chronic pulmonary complication associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:E22–E25. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thimmesch M, Gilbert A, Tuerlinckx D, Bodart E. Chronic respiratory failure due to toxic epidermal necrosis in a 10 year old girl. Acta Clin Belg. 2015;70:69–71. doi: 10.1179/2295333714Y.0000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang CW, Cho YT, Chen KL, Chen YC, Song HL, Chu CY. Long-term sequelae of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:525–529. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah AP, Xu H, Sime PJ, Trawick DR. Severe airflow obstruction and eosinophilic lung disease after Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1276–1279. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00036006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo T, Saito H, Yamakawa Y, Komatsu S, Onuma S, Okudela K, Nozawa A, Aihara M, Ikezawa Z, Ishigatsubo Y. Severe obliterative bronchitis associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Intern Med. 2011;50:2823–2827. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.50.5582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryu JH, Myers JL, Swensen SJ. Bronchiolar disorders. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1277–1292. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-053SO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]