Abstract

Background

Long-term monitoring has been advocated to enhance the detection of atrial fibrillation (AF) in patients with stroke.

Objective

To evaluate the performance of a new ambulatory monitoring system with mobile data transmission (PoIP) compared with 24-hour Holter. We also aimed to evaluate the incidence of arrhythmias in patients with and without stroke or transient ischemic attack.

Methods

Consecutive patients with and without stroke or TIA, without AF, were matched by propensity score. Participants underwent 24-hour Holter and 7-day PoIP monitoring.

Results

We selected 52 of 84 patients (26 with stroke or TIA and 26 controls). Connection and recording times were 156.5 ± 22.5 and 148.8 ± 20.8 hours, with a signal loss of 6,8% and 11,4%, respectively. Connection time was longer in ambulatory (164.3 ± 15.8 h) than in hospitalized patients (148.8 ± 25.6 h) (p = 0.02), while recording time did not differ between them (153.7 ± 16.9 and 143.0 ± 23.3 h). AF episodes were detected in 1 patient with stroke by Holter, and in 7 individuals (1 control and 6 strokes) by PoIP. There was no difference in the incidence of arrhythmias between the groups.

Conclusions

Holter and PoIP performed equally well in the first 24 hours. Data transmission loss (4.5%) occurred by a mismatch between signal transmission (2.5G) and signal reception (3G) protocols in cell phone towers (3G). The incidence of arrhythmias was not different between stroke/TIA and control groups.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation; Stroke; Electrocardiography, Ambulatory; Cell Phone; Ischemic Attack, Transient

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the main predictive factor of stroke.1 Many studies have suggested that frequent short runs of atrial tachycardia (AT) or supraventricular extrasystoles (SVES) may yield early left atrial remodeling and predict AF and increased risk for stroke.2-4 The risk for stroke is independent of clinical presentations of AF and recent studies have shown that in up to 30% of the cases, arrhythmia is diagnosed before, during or following an ischemic event.5

The diagnosis of AF requires documentation, and the detection of paroxysmal AF may be challenging.6 By convention, the diagnosis of AF requires a minimum duration of 30 seconds.7 The prognostic value of short episodes of AF is still debatable, and some authors have suggested that their occurrence may not be a benign condition.8 Detection of paroxysmal AF has been performed by different monitoring techniques, and the importance of its early detection is due to the fact that the prompt initiation of anticoagulation significantly reduces the risk of stroke recurrence by up to 40%.8-10 The American Heart Association and the Stroke Association recommend a long-term electrocardiographic monitoring of 30 days for the diagnosis of AF in post-cryptogenic stroke (class IIa; level of evidence C). Further evidence in support of this recommendation and for the establishment of the role of short AF episodes is still needed.11,12

The aim of this study was to evaluate the performance of a new ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring system using cell phone transmission in the diagnosis of AF during the acute phase of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) and compared it with 24-hour Holter, and to evaluate the incidence and the type of supraventricular arrhythmias in patients with and without stroke/TIA in its acute phase.13

Methods

Subjects: patients with recent (less than 15 days of the event) stroke/TIA were enrolled based on clinical and imaging findings. Stroke was classified as cryptogenic based on the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST).14 Ambulatory patients without stroke/TIA, but with risk factors for these events (control group) were also included, and both groups had normal sinus rhythm at electrocardiography (ECG) and no history of AF or atrial flutter (AFL).

Exclusion criteria were previous AF or AFL or admission electrocardiogram showing any of these conditions, hemorrhagic stroke, age younger than 18 years, residence in areas with no mobile phone coverage, need for intensive care due to severity of disease or difficult management of disease, sequela of neurologic injury, and patients with important cognitive impairment that could negatively affect the ability to understand the instructions related to the use of the devices. Patients with suspected stroke/TIA were seen at two medium-sized public hospitals in the city of Curvelo, Minas Gerais, Brazil, between August 2016 and April 2017. Control patients were enrolled during outpatient visits. Patients’ follow-up and therapeutic approach were left to the assistant physicians’ discretion. Patients or legal caregivers were invited to participate in the study, which was approved by the research ethics committee of University Hospital of São José/FELUMA, and all participants signed an informed form.

Measurement tools: the diagnosis of stroke/TIA was confirmed by computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and classified for etiologies using the TOAST14 criteria. CT and MRI tests were performed by radiologists experienced in the Siemens Somatom Spirit or Toshiba Asteion4 CT scanners and the GE Optima MR360 1.5T.

Demographic and clinical data: data of age, sex, skin color, place of residence, anamnesis, previous diseases, family history, weight, height, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were collected, and cardiologic and neurologic tests were also performed.

Complementary tests: 12-lead ECG, transthoracic echocardiography, Doppler examination of carotid and vertebral arteries, chest X-ray (posterior-anterior and lateral views), laboratory tests including complete blood test, urea, creatinine, glucose, transaminases, GGT, potassium, sodium, TSH, free T4, cholesterol (total and fractions), triglycerides, prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT).

Heart rhythm monitoring: during the first week after clinical diagnosis and notification of cryptogenic ischemic stroke or TIA, heart rhythm was monitored by three-channel Holter 24h recorders (DMS 300-8 and DMS 300-9) and analyzed simultaneously with the DMS CardioScan II software (DM Software Inc. Stateline, NV, USA) and electrocardiography (Policardiógrafo IP®, PoIP) (eMaster, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil).

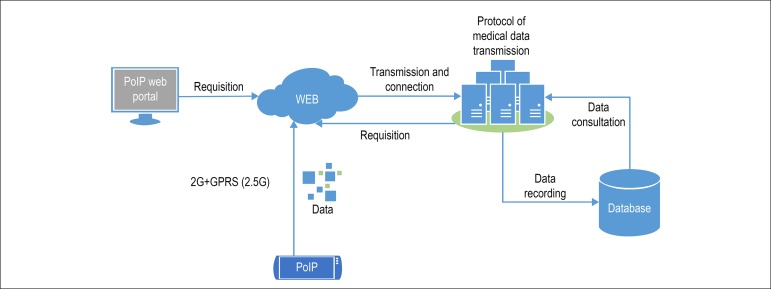

PoIP monitoring: PoIP monitors independently collect and transmit electrocardiographic data at real time using the General Packet Radio Services/ Enhanced Date Rates for GSM Evolution (GPRS/ EDGE); data are then stored in the cloud. We used the Brazilian cell phone provider Vivo for transmission of the data to the PoIP web portal, and the Mozilla Firefox was used as the web browser for analysis of the data. PoIP offers a “Portal de Exames”, an app that enables monitoring of different PoIP devices as well as the access to laboratory tests by individual access credentials (Figure 1). Six electrodes were arranged so that frontal plane leads could be monitored beyond V1-V2. Patients and family members were instructed and trained for the monitoring technique, quality of transmission signal, battery charge and charging of the lithium-based batteries. The monitoring was closely controlled via internet by the responsible staff members for the correct use of the device, and quality of the electrode contacts; if necessary, family or caregivers were informed about inadequate system operation or the quality of data transmission.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of PoIP - as can be seen in the diagram, PoIP uses the concept of real-time transmission of the data by the EDGE technology. Wireless data transmission is performed by standard protocol to internet access in mobile devices by GPRS-EDGE - Generic Packet Radio Service, commonly known as 2.5G

Procedures: Each participant received an electrode pack and a leaflet with a thorax illustration indicating electrodes’ colors and correct positioning for replacement. All electrocardiographic recordings were analyzed by the same investigator (RSF), a cardiologist experienced in ambulatory electrocardiography, and all electrocardiographic tracings considered indicative of AF or tachycardia were reviewed by a second investigator (EBS), a cardiac electrophysiologist.

For analysis of PoIP findings, the results were accessed via internet and examined for AF/AFL every 12 hours or every time the monitor button was pressed by the patient/caregiver. Every 24-hour period, all data transmitted by PoIP were exported and reviewed offline, and quantitative analysis of arrhythmias registered. In this analysis, we considered - number of (single or in pairs) SVES, number of nonsustained atrial tachycardia (AT) episodes greater than three consecutive premature atrial complexes and shorter than 30 seconds, sustained AT longer than 30 seconds and number of AF episodes longer or shorter than 30 seconds.

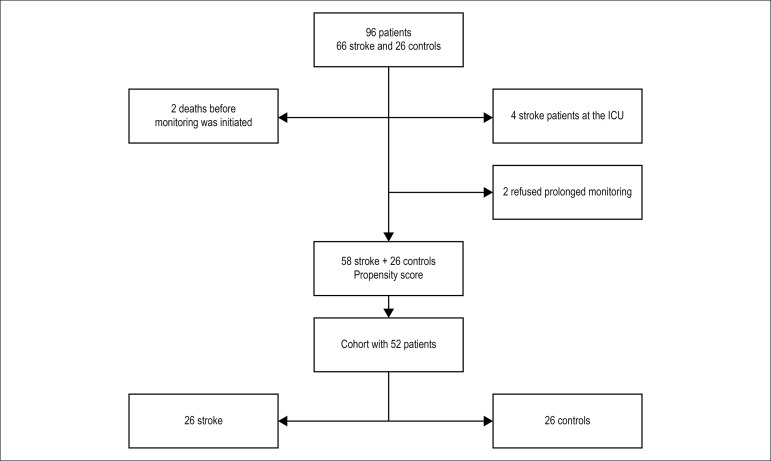

Statistical analysis: categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages and numerical variables as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Data normality assumptions were verified with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Associations between categorical variables were assessed by Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test of independence. Comparisons of two groups between independent samples were made by the Wilcoxon test, the Mann-Whitney test or the Student’s t-test, as appropriate. Analyses were performed using the free R software version 3.3.2 at 5% level of significance. Initial cohort was composed of 58 patients with stroke/acute TIA and 26 controls. For selection of patients with similar characteristics for the groups of interest, we used the propensity score matching (PSM) method. A logistic regression was constructed to estimate the probability of belonging to the stroke/TIA group, considering the following predicting variables - sex, age and CHADS2 corrected by subtracting two points in patients with stroke/TIA. PSM enabled the selection of 26 patients with stroke/TIA matched with controls by the probabilities obtained from the logistic model, so that the analysis of the cohort yielded 52 patients (26 with stroke/TIA and 26 controls) (Figure 2). Sample power to verify the difference between the recording period on the first day of Holter and PoIP use (23.7 ± 1 and 20 ± 3.2h, respectively) was greater than 80%.

Figure 2.

Flowchart depicting selection of the study groups

Results

Our sample was composed of 52 patients, equally allocated into stroke/TIA and control groups (Figure 2). More than half of patients (51.9%) were men, mean age was 70.7 ± 10.5 years, with 73.1% of patients aged 65 years or older. Mean BMI was 25.5 ± 5.6 kg/m2, 21.2% were smokers and 19.2% alcohol consumers. Mean corrected CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores were 1.8 ± 0.8 and 3.3 ± 1.2, respectively.

The most frequent comorbidities were arterial hypertension (84.6%) and diabetes mellitus (51.9%). Among control patients, a significantly higher (p = 0.03) proportion of smokers was found in stroke patients aged 65 years or older (p = 0.04). No other difference was found between the groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients’ characteristics by study groups

| Variables | Sample (n = 52) | stroke/TIA (n = 26) | Controls (n = 26) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical data | ||||

| Male sex | 27 (51.9%) | 14 (53.8%) | 13 (50%) | 1.000Q |

| Age (years) | 70.7 ± 10.5 | 70.9 ± 11.4 | 70.6 ± 9.7 | 0.917T |

| ≥ 65 years | 38 (73.1%) | 20 (76.9%) | 18 (69.2%) | 0.755Q |

| White race | 40 (76.9%) | 17 (65.4%) | 23 (88.5%) | 0.100F |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.5 ± 5.6 | 25.6 ± 4.2 | 25.4 ± 6.9 | 0.498W |

| > 30 kg/m2 | 11 (21.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0.173F |

| Smoking | 11 (21.2%) | 9 (34.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | 0.038F |

| < 65 years | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (33.3%) | 1 (12.5%) | 0.539F |

| ≥ 65 years | 8 (21.1%) | 7 (35%) | 1 (5.6%) | 0.045F |

| Alcohol consumption | 10 (19.2%) | 7 (26.9%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.291F |

| Corrected CHADS2 | 1.8 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 0.831W |

| Corrected CHA2DS2-VASc | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 1.2 | 0.598W |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 44 (84.6%) | 23 (88.5%) | 21 (80.8%) | 0.703F |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (51.9%) | 13 (50%) | 14 (53.8%) | 1.000F |

| Previous stroke2 | 6 (11.5%) | 6 (23.1%) | - | |

| Previous TIA2 | 6 (11.5%) | 6 (23.1%) | - | |

| Coronary insufficiency | 5 (9.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | 3 (11.5%) | 1.000F |

| Congestive heart failure | 5 (9.6%) | 3 (11.5%) | 2 (7.7%) | 1.000F |

| Kidney failure | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (7.7%) | - | |

| Echocardiography | ||||

| Aorta (mm) | 32.6 ± 3.9 | 33.6 ± 4.3 | 31.6 ± 3.3 | 0.079T |

| Left atrium (mm) | 36.9 ± 4.5 | 36.3 ± 4 | 37.6 ± 4.9 | 0.296T |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 63.6 ± 10.3 | 61 ± 11.3 | 66 ± 8.9 | 0.049W |

| Interventricular septum (mm) | 10.3 ± 1.4 | 10.7 ± 1.4 | 10 ± 1.3 | 0.086W |

| RV posterior wall (mm) | 9.9 ± 1.3 | 10.1 ± 1.4 | 9.8 ± 1.3 | 0.356W |

| Laboratory data | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 113 ± 57.5 | 125.5 ± 76.6 | 100.5 ± 23.5 | 0.098W |

| Glycated hemoglobin (%) | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 6.1 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 0.848T |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1.01 ± 0.38 | 1.06 ± 0.44 | 0.96 ± 0.31 | 0.614W |

| HDL (mg/dl) | 53.1 ± 15.7 | 48.8 ± 11.8 | 57.1 ± 18.1 | 0.059T |

| LDL (mg/dl) | 87.2 ± 30.8 | 91.1 ± 33.8 | 83.3 ± 27.7 | 0.376T |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 142.8 ± 96.3 | 112.4 ± 42.9 | 171.9 ± 122.4 | 0.060W |

| TSH (nU/L) | 3 ± 3.21 | 2.70 ± 2.39 | 3.22 ± 3.82 | 0.459W |

| Free T4 (ng/dl) | 1.03 ± 0.23 | 1.10 ± 0.25 | 0.96 ± 0.20 | 0.038T |

Numerical variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation; TIA: transient ischemic attack; 1Corrected CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores represent the subtraction of two points from the original scores in the stroke group; 2previous stroke and TIA were found only in the stroke group (exclusion criteria for controls); Fexact Fisher’s test; Qchi-square test of independence; WWilcoxon Mann-Whitney test and T Student’s t-test for independent samples

Complementary tests

Echocardiography: the only statistically significant difference between the groups was a lower (although within normal range) ejection fraction (p = 0.04) values in the stroke/TIA group. Clinical analysis: the only statistically significant difference was found in free T4 (p = 0.03), which was higher in stroke/TIA, but also within the normal range. No other difference was found between the groups.

Data transmission analysis

Mean recording period was 23.5 ± 0.6 hours by Holter monitoring and 148.8 ± 20.8 hours by PoIP, with no significant difference between the groups, despite higher transmission loss for artifacts among PoIP control subjects. PoIP signal losses were caused by loss of connection (6.8%) and recording signal loss in the server (Table 2).

Table 2.

Monitoring period (hours) by study groups

| Variables | Sample (n = 52) | Stroke/TIA (n = 26) | Controls (n = 26) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holter | ||||

| Recording time | 23.5 ± 0.6 | 23.4 ± 0.8 | 23.5 ± 0.4 | 0.948 |

| Loss (artifacts) | 0.6 ± 1.4 | 0.6 ± 1.7 | 0.6 ± 1 | 0.162 |

| PoIP | ||||

| Connection period | 156.5 ± 22.5 | 148.8 ± 25.6 | 164.3 ± 15.8 | 0.024 |

| Recording time on the first day | 19.2 ± 3.4 | 19.1 ± 2.5 | 19.2 ± 4.2 | 0.514 |

| Recording period | 148.8 ± 20.8 | 143.9 ± 23.3 | 153.7 ± 16.9 | 0.080 |

| Loss (artifacts) | 50.9 ± 26.2 | 45.6 ± 26.3 | 56.1 ± 25.5 | 0.081 |

Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney test for independent samples; monitoring period had been planned to be up to 24 hours by Holter andu p to 168 hours (7 days) by PoIP. Comparison of recording periods between Holter and PoIP on the first day: p < 0.001W

In the first 24 hours, longer period was required for Holter recording (23.5 ± 0.6 hours) as compared with PoIP (19.2 ± 3.4 hours) (p < 0.001).

In the stroke/TIA group, PoIP monitoring was started after 5.4 ± 2.7 days of stroke/TIA during hospitalization, and a shorter connection (p = 0.02) and recording period was observed with PoIP (Table 3).

Table 3.

Holter monitoring results by study groups

| Variables | Stroke/TIA (n = 26) | Controls (n = 26) | p-valueF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation (< 30 seconds) | 1 (3.8%) | - | - |

| Atrial tachycardia (AT) | 16 (61.5%) | 9 (34.6%) | 0.095 |

| < 65 years | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (25%) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 65 years | 15 (75%) | 7 (38.9%) | 0.047 |

| Frequent SVES* | |||

| < 65 years | 5 (19.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.703 |

| ≥ 65 years | 5 (25%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0.697 |

| Frequent AT or SVES | 17 (65.4%) | 10 (38.5%) | 0.095 |

| < 65 years | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (25%) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 65 years | 16 (80%) | 8 (44.4%) | 0.042 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 6 (23.1%) | 5 (19.2%) | 1.000 |

| < 65 years | - | 1 (12.5%) | - |

| ≥ 65 years | 6 (30%) | 4 (22.2%) | 0.719 |

| Frequent SVES | 6 (23.1%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1.000 |

| < 65 years | - | 1 (12.5%) | - |

| ≥ 65 years | 6 (30%) | 6 (33.3%) | 1.000 |

SVES: supraventricular extrasystoles;

Fisher’s exact test;

frequent SVES was defined as > de 30 events/hour

Arrhythmias

AF was detected in one patient by Holter monitoring and in 6 patients by PoIP in the stroke/TIA group, and in only one control by PoIP. Regarding other supraventricular arrhythmias, further cases of nonsustained AT and frequent AT or SVES were identified by Holter monitoring in patients aged 65 years or older in the stroke/TIA group (p = 0.04 and 0.04, respectively). In two cases, differential diagnosis of AT and nonsustained AF required revision by the two observers (RFS and EBS). It is worth mentioning, however, that patients who had AF also had AT, and therefore, a misinterpretation of electrocardiographic tracings would not affect the results, due to the occurrence of both conditions in the same patient.

PoIP monitoring revealed that there were no significant differences between the groups regarding tachycardia (Table 4), and all patients with AF also had AT.

Table 4.

POIP monitoring results by study groups

| Variables | Stroke/TIA (n = 26) | Controls (n = 26) | p-valueF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation (< 30 seconds)* | 6 (23.1%) | 1 (3.8%) | 0.099 |

| First 24h | 2 (7.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1.000 |

| Atrial tachycardia | 22 (84.6%) | 18 (69.2%) | 0.324 |

| < 65 years | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 65 years | 18 (90%) | 13 (72.2%) | 0.222 |

| First 24h | 12 (46.2%) | 14 (53.8%) | 0.782 |

| Frequent SVES** | 4 (15.4%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.727 |

| < 65 years | - | 1 (12.5%) | - |

| ≥ 65 years | 4 (20%) | 5 (27.8%) | 0.709 |

| First 24h | 2 (7.7%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.249 |

| Frequent atrial tachycardia or SVES | 22 (84.6%) | 19 (73.1%) | 0.499 |

| < 65 years | 4 (66.7%) | 5 (62.5%) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 65 years | 18 (90%) | 14 (77.8%) | 0.395 |

| First 24h | 12 (46.2%) | 14 (53.8%) | 0.782 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 7 (26.9%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1.000 |

| < 65 years | - | 2 (25%) | - |

| ≥ 65 years | 7 (35%) | 5 (27.8%) | 0.734 |

| First 24h | 3 (11.5%) | 4 (15.4%) | 1.000 |

| Frequent ventricular extrasystoles | 8 (30.8%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1.000 |

| < 65 years | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (12.5%) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 65 years | 7 (35%) | 6 (33.3%) | 1.000 |

| First 24h | 6 (23.1%) | 6 (23.1%) | 1.000 |

SVES: supraventricular extrasystoles;

Fisher’s exact test;

all cases identified in patients aged ≥65 years;

frequent SVES was defined as > de 30 events/hour

Comparisons between Holter and PoIP results showed a higher proportion of AT identified by PoIP in both stroke/TIA (p = 0.004) and control (p = 0.02) groups. Also, PoIP monitoring revealed a higher proportion of patients with frequent AT or SVES in the stroke/TIA (p = 0.01) and control (p = 0.02) groups considering total monitoring period, but no difference was found between the groups in the first 24 hours.

Discussion

In the present study that included 52 patients older than 59 years, prolonged rhythm monitoring was performed in 26 patients with acute cerebrovascular events, and initiated only 5 days (mean) after the event. The main findings were high prevalence of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus, some connectivity problems and problems related to PoIP signals’ recording, and similar profile of cardiac arrhythmias between the study groups.

The most frequent comorbidities were arterial hypertension (84.6%) and diabetes mellitus (51.9%), with similar distribution between the groups studied. This result was expected, since these variables were used in the PSM model, and both comorbidities are also included in the CHADS2 and CHA2DS2-VASc scores. Although these scores provide simple methods for predicting an individual risk of ischemic stroke, the risk estimated by these instruments represent only part of the overall risk (statistical agreement of 0.5). In other words, not all patients with a CHADS2 score equal to 0 or 1 have a low risk, and hence the clinical decision not to anticoagulate patients based only on this score may be erroneous. Despite the higher specificity of a CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2, this still underestimates the risk.15

For this reason, we analyzed with particular interest the higher prevalence of smoking in stroke/TIA patients (p = 0.038), especially among patients older than 65 years (p = 0.045). A recent meta-analysis showed that smoking is associated with a modest increase in AF, and that quitting smoking reduces but not eliminates the associated risk of the disease.16-18 Nevertheless, the addition of smoking to the score does not improve the risk prediction of stroke or TIA.19

Monitoring by mobile phone

Although PoIP and Holter monitoring systems had similar performance in the first 24 hours, there were problems with signal connection and transmission during PoIP monitoring. Loss of connection with the cell phone provider accounted for 6.8% of total monitoring time, shorter recording time in the server and lower data losses due to artifacts (Table 2). Loss of connectivity was greater in hospitalized (stroke) patients (p = 0.024).

For better interpretation of this result, we measured the strength of the provider signal using the Network Monitor® software in the ward facilities. We found a high signal variation depending on the site where the measurements were obtained - in the entrance, in the middle and in the ward exit, the signal velocity was 1.6, 12.3 and 0.3 Mbs, respectively, and signal strength was 60, 70 and 20%. Such high signal variation may explain signal losses during the monitoring of patients hospitalized in these areas, which would be lower in the outpatient department.

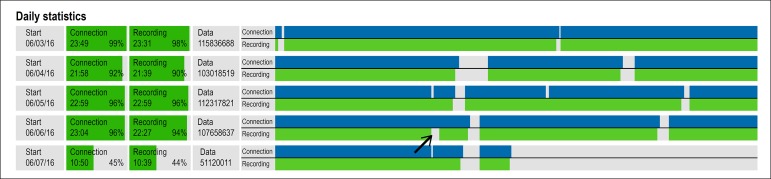

In addition, transmission losses may occur even in cases of adequate connectivity between PoIP and the mobile phone provider, due to instability of the mobile phone network. During these unstable periods, PoIP remains connected to the provider, and data transmission is restored when connection is recovered (Figure 3). Although such instability periods, are usually short, in our study, they accounted for 11.4% of total monitoring time, i.e. approximately 19 hours a week per patient (Table 2). Also, we found that after the repair of transmission towers and antennas, signal reception was changed from 2.5G (GPRS General Packet Radio Service) to 3G, which negatively affects data transmission. Updating of the technology from 3G to 4G would resolve this issue, as well as reduce the energy expenditure with data package transmission, resulting in optimization of rechargeable battery duration, reduction of charging time and improving monitoring performance.

Figure 3.

PoIP provides daily statistics of connection (blue line) and recoding (green line) data of signal transmission in the server. It is of note that connection and transmission percentages are very similar to each other (day 3/6: 99% and 98%, day 4/6: 92% and 90%, day 5/6: 96% and 96%). Small losses occurred, as on 6/6/2016, when there was a brief period when signal was transmitted but not recorded in the server (arrow)

Greater data loss due to artifacts was seen in control subjects in the PoIP group, which may be justified by the greater freedom of movement of patients in ambulatory treatment.

Arrhythmias detected by PoIP (firs 24 hours) compared with Holter-24

In the first 24 hours, no difference in arrhythmias was observed (AT, SVES, SVES + AT). Despite the longer monitoring period by Holter recordings, all AT runs and the three episodes of AF (2 in the stroke and 1 in the control group).

Twenty-four hour Holter compared with prolonged monitoring

Comparison between Holter and PoIP monitoring results showed a higher proportion of frequent AT and SVES detected by PoIP monitoring in both stroke/TIA and control groups, which was expected by its longer monitoring period.

Comparison of arrhythmias detected in stroke group and controls

No significant difference was found in the occurrence of AT or nonsustained AF, in the comparison between patients with cryptogenic stroke and a control group matched by sex, age and corrected CHADS2. We report a high prevalence of atrial arrhythmias in 52 patients, including 40 with AT and 7 with AF. In stroke/TIA group, proportion of AF was 23.1% in patients monitored by PoIP, and 3.8% in those monitored by Holter, which is in agreement with the literature (Tables 3, 4 and 5).20 Some studies have suggested that and additional 24-hour period of monitoring would increase the percentage of new diagnoses of paroxysmal AF in 2-4% stroke patients.21,22 This confirms the efficacy of prolonged ambulatory ECG in patients at risk of AF and may generate a clinically significant diagnostic yield.23

Table 5.

Comparisons between Holter and POIP monitoring results

| Variable | Holter | POIP | p-valueF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation (< 30 seconds) | 1 (1.9%) | 7 (13.5%) | 0.060 |

| AVC/AIT | 1 (3.8%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.099 |

| Controls | - | 1 (3.8%) | - |

| First 24h | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (5.7%) | 0.618 |

| Atrial tachycardia | 25 (48.1%) | 40 (76.9%) | 0.004 |

| AVC/AIT | 16 (61.5%) | 22 (84.6%) | 0.116 |

| Controls | 9 (34.6%) | 18 (69.2%) | 0.025 |

| First 24h | 25 (48.1%) | 26 (50%) | 1.000 |

| Frequent SVES* | 8 (15.4%) | 10 (19.2%) | 0.796 |

| AVC/AIT | 5 (19.2%) | 4 (15.4%) | 1.000 |

| Controls | 3 (11.5%) | 6 (23.1%) | 0.465 |

| First 24h | 8 (15.4%) | 8 (15.4%) | 1.000 |

| Frequent atrial tachycardia or SVES | 27 (51.9%) | 41 (78.8%) | 0.007 |

| Stroke/TIA | 17 (65.4%) | 22 (84.6%) | 0.199 |

| Controls | 10 (38.5%) | 19 (73.1%) | 0.025 |

| First 24h | 27 (51.9%) | 26 (50%) | 1.000 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 11 (21.2%) | 14 (26.9%) | 0.647 |

| Stroke/TIA | 6 (23.1%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1.000 |

| Controls | 5 (19.2%) | 7 (26.9%) | 0.743 |

| First 24h | 11 (21.2%) | 7 (13.5%) | 0.438 |

| Frequent ventricular extrasystoles | 13 (25%) | 15 (28.8%) | 0.825 |

| Stroke/TIA | 6 (23.1%) | 8 (30.8%) | 0.755 |

| Controls | 7 (26.9%) | 7 (26.9%) | 1.000 |

| First 24h | 13 (25%) | 12 (23.1%) | 1.000 |

SVES: supraventricular extrasystoles;

Fisher’s exact test;

frequent SVES was defined as > de 30 events/hour

Studies have highlighted the association of frequent SVES and AT with increased risk of stroke.2,3,4,24-27 Studies involving long-term heart rhythm monitoring in patients with previous stroke/TIA have reported a paroxysmal AF prevalence of 5-20%.20,28,30-33

In our study, all AF episodes lasted less than 30 seconds. Although an AF episode ≥ 30 seconds is used as a parameter for the diagnosis of AF,7 some authors have suggested that short AF episodes have an impact on the risk of stroke/TIA or systemic thromboembolism.10,33

One important finding was the lack of difference in the prevalence of atrial arrhythmias between patients with and without stroke or TIA, at similar risk for these conditions. This finding suggests that the atrial arrhythmias detected may be an epiphenomenon. Kottkamp and other authors15,34 have suggested the presence of a thrombogenic fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, with risk for embolic events with no causal connections with atrial arrhythmias. Contractile changes would be responsible for the increased thrombogenic risk during sinus rhythm, in addition to interatrial block and sinus node dysfunction. Even ablation of AF would not be able to impede the progression of fibrotic process.34 Factors like diabetes, hypertension, age, among others, would be involved in myocardial damage. In our sample, more than 80% of patients had arterial hypertension and more than 50% were diabetic. Non-invasive detection of atrial fibrosis is currently limited to MRI techniques, not available in clinical practice.34 In this context, AF would be a manifestation of atrial structural changes, and thereby increasing the risk of embolic events.

None of our patients with stroke/TIA had AF before or during stroke. In fact, AF may be detected in only a minority of the cases and may take months, as shown by the TRANDS, ASSERT and IMPACT studies, which included patients with implantable continuous monitoring devices.35-37

The paradigm used in most studies is that AF detection would be just a matter of time, but even in a one-year follow up, AF is detected in less than half of patients with cryptogenic stroke. This is a pioneering study in monitoring patients at similar stroke and TIA risk, by including a group with stroke and a control group without the disease. The finding that the incidence of atrial arrhythmias was not different between both groups is consistent with the hypothesis that a factor other than arrhythmia may be involved in the risk for stroke; one possibility is fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy.

Study limitations

The sample size was insufficient to evaluate individual risk factors. Discrimination between short runs of atrial tachycardia and AF may be difficult, even to an experienced electrophysiologist. P-waves in ambulatory monitoring systems may not be clearly identified as compared with conventional 12-lead ECG. Nevertheless, analysis of isolated episodes and analysis of more than one arrhythmia episode yielded similar results, since all patients that had short AF episodes also had AT.

Mobile phone services currently available still have limited coverage, with absent or deficient signal strength, and unstable transmission velocity, which altogether, negatively affect PoIP data collection. Due to frequent repairs of problems caused by electrical discharges in cell phone towers, access to GPRS may be lost, thereby affecting signal reception, which may be solved by implementation of the 4G technology.

Conclusions

Holter and PoIP showed comparable results in the first 24 hours. The shorter monitoring period was caused by a low signal strength. Data transmission loss in hospitalized patients resulted from a mismatch between the protocol of signal transmission in the cell phone tower (3G) and the signal effectively transmitted (2.5G), which can be mitigated by the adoption of a 4G technology. The incidence of arrythmia was not different between stroke and control groups.

Footnotes

Sources of Funding

There were no external funding sources for this study.

Study Association

This article is part of the thesis of master submitted by Rogerio Ferreira Sampaio, from Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências da Saúde da Faculdade Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitário São José/FELUMA under the protocol number CAAE=35481114.0.0000.5134. All the procedures in this study were in accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, updated in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Author contributions

Conception and design of the research, acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Sampaio RF, Gomes IC, Sternick EB; Analysis and interpretation of the data: Gomes IC; Writing of the manuscript: Sampaio RF, Sternick EB.

Potential Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Blaha MJ. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2014 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129(3):e28–292. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000441139.02102.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glotzer TV, Hellkamp AS, Zimmerman J, Sweeney MO, Yee R, Marinchak R, et al. Atrial high rate episodes detected by pacemaker diagnostics predict death and stroke: report of the Atrial Diagnostics Ancillary Study of the MOde Selection Trial (MOST) Circulation. 2003;107(9):1614–1619. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000057981.70380.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larsen BS, Kumarathurai P, Falkenberg J, Nielsen OW, Sajadieh A. Excessive atrial ectopy and short atrial runs increase the risk of stroke beyond incident atrial fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(3):232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kochhauser S, Dechering DG, Reinke F, Ramtin S, Frommeyer G, Eckardt L. Supraventricular premature beats and short atrial runs predict atrial fibrillation in continuously monitored patients with cryptogenic stroke. Stroke. 2014;45(3):884–886. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.003788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, Ahlsson A, Atar D, Casadei B, et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(38):2893–2962. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wohlfahrt J, Stahrenberg R, Weber-krüger M, Gröschel S, Wasser K, Edelmann F, et al. Clinical predictors to identify paroxysmal atrial fibrillation after ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(1):21–27. doi: 10.1111/ene.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kirchhof P, Auricchio A, Bax J, Crijns H, Camm J, Diener HC, et al. Outcome parameters for trials in atrial fibrillation: executive summary. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(22):2803–2817. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sposato LA, Cipriano LE, Riccio PM, Hachinski V, Saposnik G. Very short paroxysms account for more than half of the cases of atrial fibrillation detected after stroke and TIA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke. 2015;10(6):801–807. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akrawinthawong K, Venkatesh PK, Mehdirad AA, Ferreira SW. Atrial fibrillation monitoring in cryptogenic stroke: the gaps between evidence and practice. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(12):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s11886-015-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hart RG, Diener HC, Coutts SB, Easton JD, Granger CB, O'Donnell MJ, et al. Embolic strokes of undetermined source: the case for a new clinical construct. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(4):429–438. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70310-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, Bravata DM, Chimowitz MI, Ezekowitz MD, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160–2236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.January CT, Wann LS, Alpert JS, Calkins H, Cigarroa JE, Cleveland Jr JC, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2014;130(23):2071–2104. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dussault C, Toeg H, Nathan M, Wang ZJ, Roux JF, Secemsky E. Electrocardiographic monitoring for detecting atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2015;8(2):263–269. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams Jr HP, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 1993;24(1):35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsh BJ, Copeland-Halperin RS, Halperin JL. Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation, and thromboembolism: mechanistic links and clinical inferences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(20):2239–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.03.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ritter MA, Kochhauser S, Duning T, Reinke F, Pott C, Dechering DG, et al. Occult atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke: detection by 7-day electrocardiogram versus implantable cardiac monitors. Stroke. 2013;44(5):1449–1452. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.676189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ziegler PD, Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Singer DE, Ezekowitz MD, Hoyt RH, et al. Detection of previously undiagnosed atrial fibrillation in patients with stroke risk factors and usefulness of continuous monitoring in primary stroke prevention. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(9):1309–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu W, Yuan P, Shen Y, Wan R, Hong k. Association of smoking with the risk of incident atrial fibrillation: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Inter J Cardiol. 2016;218:259–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon Y, Norby FL, Jensen PN, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Lip GY, et al. Association of Smoking, Alcohol, and Obesity with Cardiovascular Death and Ischemic Stroke in Atrial Fibrillation: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study and Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) PLoS One. 2016;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell C, Kapral M. Use of ambulatory electrocardiography for the detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with stroke. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27(1):25–31. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100051933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazzaro MA, Krishnan K, Prabhakaran S. Detection of atrial fibrillation with concurrent holter monitoring and continuous cardiac telemetry following ischemic stroke and transient ischemic attack. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21(2):89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shafqat S, Kelly PJ, Furie KL. Holter monitoring in the diagnosis of stroke mechanism. Intern Med J. 2004;34(6):305–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turakhia MP, Ullal AJ, Hoang DD, Than CT, Miller JD, Friday KJ, et al. Feasibility of extended ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring to identify silent atrial fibrillation in high-risk patients: the Screening Study for Undiagnosed Atrial Fibrillation (STUDY-AF) Clin Cardiol. 2015;38(5):285–292. doi: 10.1002/clc.22387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marijon E, Le Heuzey JY, Connolly S, Yang S, Pogue J, Brueckmann M, et al. Causes of death and influencing factors in patients with atrial fibrillation: a competing-risk analysis from the randomized evaluation of long-term anticoagulant therapy study. Circulation. 2013;128(20):2192–2201. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.000491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip G, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation The Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2010;31(19):2369–2429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liao J, Khalid Z, Scallan C, Morillo C, O'Donnell M. Noninvasive cardiac monitoring for detecting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter after acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2935–2940. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.478685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gladstone DJ, Dorian P, Spring M, Panzov V, Mamdani M, Healey M. Atrial premature beats predict atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke: results from the EMBRACE trial. Stroke. 2015;46(4):936–941. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.008714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzmaurice DA, Hobbs FD, Jowett S, Mant J, Murray ET, Holder R. Screening versus routine practice in detection of atrial fibrillation in patients aged 65 or over cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;335(7616):383–386. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39280.660567.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liao J, Khalid Z, Scallan C, Morillo C, O'Donnell M. Noninvasive cardiac monitoring for detecting paroxysmal atrial fibrillation or flutter after acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review. Stroke. 2007;38(11):2935–2940. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.106.478685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gaillard N, Deltour S, Vilotijevic B, Hornyc A, Crozier S, Leger A, et al. Detection of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation with transtelephonic EKG in TIA or stroke patients. Neurology. 2010;74(21):1666–1670. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e0427e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jabaudon D, Sztajzel J, Sievert K, Landis T, Sztajzel R. Usefulness of ambulatory 7-day ECG monitoring for the detection of atrial fibrillation and flutter after acute stroke and transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1647–1651. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131269.69502.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tayal AH, Tian M, Kelly KM, Jones SC, Wright DJ, Singh D, et al. Atrial fibrillation detected by mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry in cryptogenic TIA or stroke. Neurology. 2008;71(21):1696–1701. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000325059.86313.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Higgins P, Dawson J, MacFarlane PW, McArthur K, Langhorne P, Lees KR. Predictive value of newly detected atrial fibrillation paroxysms in patients with acute ischemic stroke, for atrial fibrillation after 90 days. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2134–2136. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kottkamp H. Fibrotic atrial cardiomyopathy: a specific disease/syndrome supplying substrates for atrial fibrillation, atrial tachycardia, sinus node disease, AV node disease, and thromboembolic complications. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2012;23(7):797–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2012.02341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, Singer DE, Ezekowitz MD, Hilker C. The relationship between daily atrial tachyarrhythmia burden from implantable device diagnostics and stroke risk: the TRENDS study. Circ Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 2009;2(5):474–480. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.849638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci A, et al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):120–129. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ip J, Waldo AL, Lip GY, Rothwell PM, Martin DT, Bersohn MM, et al. Multicenter randomized study of anticoagulation guided by remote rhythm monitoring in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator and CRT-D devices: Rationale, design, and clinical characteristics of the initially enrolled cohort The IMPACT study. Am Heart J. 2009;158(3):364.e1–370.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]