Abstract

Aims/Introduction

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus fluctuate throughout the year. However, there are few studies that have evaluated the therapeutic effect of hypoglycemic agents while considering such fluctuations. In a multicenter study (Januvia Multicenter Prospective Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Study), pretreatment patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were divided into seven groups and given sitagliptin for 1 year. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the differences in the therapeutic effect, and the efficacy of sitagliptin in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus based on the month the administration of the drug began as a subanalysis of the Januvia Multicenter Prospective Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Study.

Materials and Methods

Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus were divided into four groups according to the month of initiation of sitagliptin. Changes in HbA1c in each group were compared at 3 and 12 months after administration of sitagliptin. As a negative correlation has been reported between baseline HbA1c and the degree of change after administration of sitagliptin, an analysis using the residual error from the approximate line was carried out.

Results

In the analysis of the degree of change in HbA1c, patients in the group in which administration of sitagliptin was started between August and October had the lowest degree of improvement at 3 months after starting sitagliptin. However, there was no significant intergroup difference in improvement at 12 months after the start of sitagliptin. The same result was also obtained in residual analysis.

Conclusions

The present study suggested that the season of administration of sitagliptin influenced the subsequent hypoglycemic effect even after analysis excluding the influence of HbA1c value at the start of treatment. This study provides possibility, showing that seasonal fluctuations have an effect on the efficacy of antidiabetic drugs.

Keywords: Seasonal fluctuation in hemoglobin A1c, Sitagliptin, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

In the treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, it is important to lower the blood glucose level and keep the value constant. However, many reports have stated that hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus fluctuate throughout the year1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9. Surveys in Japanese patients showed that the level generally increased in winter and decreased from summer to autumn1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The authors investigated the HbA1c level in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus for 10 years (1995–2005) using accumulated long‐term intervention data. The results showed that monthly HbA1c was the highest in March (7.69%) and lowest in August (7.46%)1. Analysis of the frequency by month showed that the highest level occurred most often from February to April, whereas the lowest level occurred most often from August to October1. Management of HbA1c for patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus might be disturbed by seasonal fluctuations. To prevent this, patients with type 2 diabetes might need to be careful about controlling HbA1c depending on the seasons.

Matsuhashi et al.10 administered sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase‐4 inhibitor, to patients in December and compared the HbA1c level with that in February the next year; they paid particular attention to increases in HbA1c occurring during winter. Consequently, HbA1c increased by 0.22% in a group in which previous treatment was continued, and increased 0.13% in a group in which the therapy was switched to sitagliptin during winter10. Furthermore, HbA1c was decreased by 0.08% in a group in which sitagliptin was add‐on therapy10. Matsuhashi et al.10 demonstrated the ability of sitagliptin to decrease blood glucose levels in winter. However, no information on administration in other seasons (months) could be obtained, because they focused on winter only. The start of antidiabetic drug therapy is not limited to winter. Therefore, it is important to show the influence of sitagliptin on the improvement of HbA1c when it is started in a season other than winter. The authors proposed that seasonal fluctuation in HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus should be a consideration in the treatment of diabetes1. However, few reports have evaluated the effect of hypoglycemic agents on HbA1c improvement while considering seasonal fluctuations.

In a multicenter study (Januvia Multicenter Prospective Trial in Type 2 Diabetes [JAMP] Study), pretreatment patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus whose HbA1c levels were poorly controlled by diet therapy, exercise therapy or existing antidiabetic drugs were divided into seven groups and given sitagliptin for 1 year11. The differences in therapeutic effect and efficacy by sitagliptin start timing were evaluated in the subanalysis of the present study.

Methods

Study design

This was an open‐label, central‐registration, prospective, intervention study carried out at Tokyo Women's Medical University Hospital and in 69 joint research facilities in Japan. Patients were registered from 11 January 2011 to 30 June 2013 and followed until 30 June 2014. The present study was carried out in accordance with the study protocol, the Declaration of Helsinki and “Ethical Guidelines for Clinical Studies” by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, and received funding from the Japan Diabetes Foundation after being approved by the ethics committee of Tokyo Women's Medical University. Before participating in the study, written information was provided to all patients, each of whom provided written consent.

Study participants

The present study included outpatients aged ≥20 years with type 2 diabetes mellitus whose blood glucose levels were poorly controlled by only diet/exercise therapy or diet/exercise + treatment with antidiabetic drugs for >1 month. Poor glycemic control at baseline was defined as an HbA1c level ≥6.9% or a fasting blood glucose ≥130 mg/dL. As the baseline HbA1c level was expressed as the Japanese Diabetes Society level, the standard in Japan (2011), the Japanese Diabetes Society levels were converted to National Glycohemoglobin Standardization program levels in accordance with the “Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus (Revision for International Harmonization of HbA1c in Japan)” by the Japanese Diabetes Society at the end of the study12.

Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded from the study: (i) history of severe ketosis, diabetic coma or pre‐coma within the past 6 months; (ii) severe infection before or after surgical treatment, or serious external injury; (iii) pregnancy, possible pregnancy or lactation; (iv) moderate renal impairment (serum creatinine level ≥1.5 mg/dL in men and ≥1.3 mg/ dL in women); (v) patients on insulin therapy; (vi) patients on treatment with rapid‐acting insulin secretagogues; (vii) history of allergy to the ingredients of the study drug; and (viii) a medical reason that makes the patient unsuitable for participation in the study as judged by the investigator.

Methods

After diet/exercise therapy or diet therapy/exercise + treatment with antidiabetic drugs for a >1‐month observation period, sitagliptin 50 mg once daily was administered as a new agent (monotherapy) or add‐on agent (combined therapy; Figure S1). Patients received these treatments without the addition or dose escalation of other drugs for 3 months after starting sitagliptin (baseline). The dose escalation of sitagliptin from 50 to 100 mg/day, addition of a new drug, change in dose of current drugs or discontinuation of other antidiabetic drugs was permitted at the physician's discretion after 3 months of sitagliptin therapy. Although the use of therapeutic agents to treat complications were not prohibited, changes in dose or the addition of drugs was limited whenever possible during the study period.

To investigate the seasonal effect of sitagliptin on the reduction of HbA1c, patients were divided into four groups based on the month sitagliptin was started. We previously showed the distribution of peak and nadir months of HbA1c levels among patients. The peak of patients was most frequently distributed in March, and the nadir was most frequently distributed in September1. We set the highest group of HbA1c from February to April, and the lowest group of HbA1c from August to October. Thus, patients who started sitagliptin from February to April, May to July, August to October and November to January (the next year), were designated as groups 1, 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The analysis included patients for whom HbA1c levels were measured at baseline (0 month) and 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin. This method was intended to analyze the seasonal difference using the same population at 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin.

Evaluation

Mean changes in HbA1c level were calculated at 3 and 12 months after the start of sitagliptin. The main paper for the present study showed a strong negative correlation between baseline HbA1c and the degree of change at 3 months after starting sitagliptin11. Therefore, residual errors at each time‐point were calculated to eliminate the effect of baseline HbA1c on post‐administration efficacy. In particular, a regression line was drawn by plotting the degree of change (ΔHbA1c) from baseline to that at 3 months after starting sitagliptin. The mean difference (residual error) between the expected value based on the approximate formulation of the regression line and the observed variation was calculated for each group. A similar regression line was drawn for HbA1c at 12 months after starting sitagliptin to calculate the mean residual error for each group. Additionally, change in body mass index (BMI) was measured at 3 and 12 months in each group.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using R version 3.4.0 (or higher; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [https://www.R-project.org/]). Correlation was tested using the Pearson product‐moment correlation coefficient. Comparison testing was carried out among groups using the Tukey–Kramer method for the degree of change. The factors that affect the HbA1c lowering effect were evaluated using multiple regression analysis. The residual error of HbA1c is expressed as mean ± standard error. Patient demographic characteristics were evaluated using analysis of variance and the χ2‐test. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation, whereas the nominal scale is expressed as the number of cases (%). Each test was carried out using a significance level of 5% (two‐sided testing).

Ethic approval and consent to participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. The ethics committee at the Tokyo Women's Medical University approved the study (approval number: 2064) on 11 January 2011. Informed consent or substitute for it was obtained from all patients included in the study.

Results

Of the 651 cases of the efficacy population in the JAMP study, a subanalysis was carried out of 568 cases observed for 12 months in which HbA1c was measured at baseline and at 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin. Groups 1, 2, 3 and 4 included 200, 180, 70 and 118 patients, respectively (Figure S2).

Patient demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were observed between groups for only biguanide as a previous medication. However, no significant difference was observed at a moderate dose of glimepiride, which, in a multivariable analysis in the main paper for the present study, was suggested to be involved in the effect of sitagliptin11. Therefore, no analysis with adjustment for previous medications was carried out.

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics

| Group parameters | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 200) | (n = 180) | (n = 70) | (n = 118) | ||

| Age (years) | 63.4 ± 10.4 | 64.5 ± 11.5 | 63.0 ± 11.6 | 64.4 ± 12.3 | 0.661 |

| Sex (male) | 131 (65.5) | 120 (66.7) | 48 (68.6) | 77 (65.3) | 0.963 |

| Abdominal circumference (cm) | 88.9 ± 12.7 | 89.9 ± 9.8 | 85.4 ± 11.1 | 86.6 ± 10.8 | 0.095 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 4.6 | 25.7 ± 4.1 | 24.9 ± 3.8 | 25.2 ± 3.8 | 0.269 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.82 ± 0.97 | 7.79 ± 1.12 | 7.75 ± 0.97 | 7.86 ± 0.96 | 0.905 |

| Duration of diabetes mellitus (years) | 9.60 ± 7.07 | 8.66 ± 6.88 | 7.45 ± 5.32 | 8.94 ± 6.68 | 0.158 |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 160.4 ± 38.6 | 148.1 ± 36.7 | 159.9 ± 34.2 | 164.9 ± 46.0 | 0.009* |

| SBP (mmHg) | 130.5 ± 14.9 | 130.4 ± 14.3 | 127.6 ± 13.8 | 133.1 ± 16.5 | 0.109 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.2 ± 10.9 | 76.4 ± 10.5 | 74.9 ± 10.2 | 77.9 ± 11.1 | 0.306 |

| Smoking habit† | 41 (21.0) | 40 (23.3) | 10 (14.7) | 26 (22.4) | 0.521 |

| Drinking habit‡ | 95 (48.7) | 82 (47.7) | 30 (44.1) | 50 (43.9) | 0.817 |

| Complications | 177 (88.5) | 160 (88.9) | 58 (82.9) | 108 (91.5) | 0.349 |

| Concomitant drugs | 152 (76.0) | 120 (66.7) | 45 (64.3) | 88 (74.6) | 0.096 |

| Complications | |||||

| Hypertension | 120 (60.0) | 114 (63.3) | 33 (47.1) | 77 (65.3) | 0.073 |

| Dyslipidemia | 128 (64.0) | 122 (67.8) | 42 (60.0) | 78 (66.1) | 0.676 |

| Hyperuricemia | 26 (13.0) | 18 (10.0) | 5 (7.1) | 7 (5.9) | 0.183 |

| Retinopathy | 16 (8.0) | 8 (4.4) | 4 (5.7) | 14 (11.9) | 0.106 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (1.5) | 5 (2.8) | 5 (7.1) | 2 (1.7) | 0.073 |

| Renal disease | 17 (8.5) | 16 (8.9) | 1 (1.4) | 8 (6.8) | 0.199 |

| Hepatic disease | 16 (8.0) | 23 (12.8) | 3 (4.3) | 9 (7.6) | 0.135 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (2.5) | 6 (3.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (3.4) | 0.474 |

| Cerebral stroke§ | 11 (5.5) | 15 (8.3) | 6 (8.6) | 8 (6.8) | 0.694 |

| Angina pectoris | 8 (4.0) | 6 (3.3) | 4 (5.7) | 6 (5.1) | 0.807 |

| Cardiac failure | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (0.8) | 0.693 |

| Pretreatment drugs | |||||

| Diet/exercise therapy | 48 (24.0) | 60 (33.3) | 25 (35.7) | 30 (25.4) | 0.096 |

| Low dose of glimepiride | 20 (10.0) | 18 (10.0) | 9 (12.9) | 14 (11.9) | 0.873 |

| Medium dose of glimepiride | 14 (7.0) | 15 (8.3) | 6 (8.6) | 8 (6.8) | 0.930 |

| BG | 33 (16.5) | 15 (8.3) | 9 (12.9) | 29 (24.6) | 0.002* |

| TZD | 12 (6.0) | 12 (6.7) | 1 (1.4) | 6 (5.1) | 0.414 |

| α‐GI | 3 (1.5) | 6 (3.3) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (2.5) | 0.709 |

| Multidrug therapy | 70 (35.0) | 54 (30.0) | 18 (25.7) | 28 (23.7) | 0.157 |

Data presented as mean ± standard deviation or n (%). *P < 0.05 (analysis of variance or χ2‐test). †Excluding 17 unknown cases. ‡Excluding 19 unknown cases. §Including hemorrhagic stroke and infarction stroke. α‐GI, α‐glucosidase inhibitor; BMI, body mass index; BG, biguanide; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c, SBP, systolic blood pressure; TZD, thiazolidine.

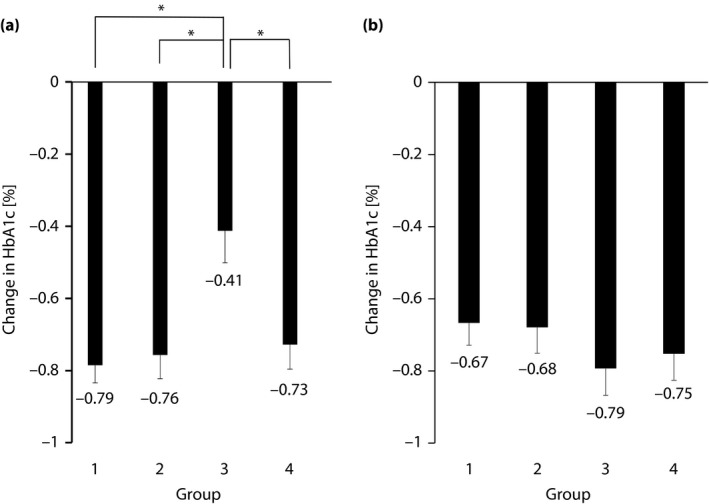

The degrees of change in HbA1c at 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin are shown in Figure 1. Comparison of the extent of change in HbA1c between groups showed a significant difference between group 3 and the other three groups at 3 months after starting sitagliptin. However, no significant difference was observed among groups at 12 months. Sitagliptin, however, was started from August to October in group 3 when the HbA1c level was the lowest. Therefore, to eliminate the effect of baseline HbA1c on the degree of change in HbA1c caused by sitagliptin, we compared the residual error of each group obtained from linear regression.

Figure 1.

Degree of change in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) after starting sitagliptin. (a) At 3 months. Mean ± standard error, *P < 0.05 (groups compared using the Tukey–Kramer method). (b) At 12 months. Mean ± standard error, not significant.

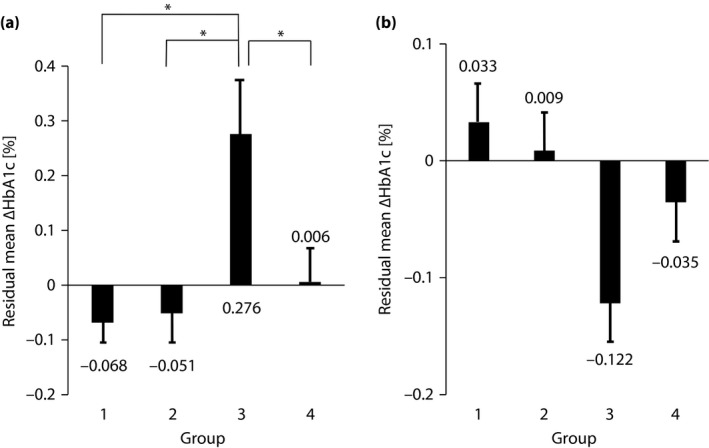

Next, we analyzed the change in HbA1c using residual error from the regression line in the same way as analyzed in the main paper11. The regression equation based on a regression line drawn from the correlation between baseline HbA1c level and the degree of change at 3 months after starting sitagliptin was as follows: y = −0.42x + 2.60 (r = −0.53, P = 0.001) (Figure S3a). Similarly, the regression equation based on the relationship between baseline HbA1c level and the amount of change at 12 months after starting sitagliptin was as follows: y = −0.44x + 2.74 (r = −0.52, P = 0.001) (Figure S3b). If the residual error is negative, the improvement effect of sitagliptin is considered strong, whereas if the residual error is positive, the effect is considered weak. The mean residual error at 3 months after starting sitagliptin was −0.0684 ± 0.0382 (mean ± standard error) for group 1, −0.0514 ± 0.0530 for group 2, 0.276 ± 0.0977 for group 3 and 0.00570 ± 0.0619 for group 4. Comparison of groups showed a significant difference between group 3 and the other groups (Figure 2a). The mean residual error at 12 months after starting sitagliptin was 0.0330 ± 0.0541 for group 1, 0.00876 ± 0.0593 for group 2, −0.122 ± 0.0662 for group 3 and −0.0354 ± 0.0652 for group 4. Testing showed no significant intergroup difference (Figure 2b). Furthermore, to investigate the factors of reducing HbA1c, we also carried out multiple regression analysis with HbA1c at 0 months, usage of medium dose of glimepiride at 0 months, BMI at 0 months and groups as a factor. We found HbA1c at 0 months, usage of medium dose of glimepiride at 0 months, BMI at 0 months and group 3 were the factors. A significant difference was found between group 3 and the other groups in 3 months, but no significant difference was found in 12 months. We obtained the same results similar to analysis using residuals (Table S1). Furthermore, we analyzed the residuals of HbA1c at 12 months using the data including only patients without drug change after 3 months to 12 months (Table S2). We found there was no significant difference in each group at 12 months using the Tukey–Kramer method. Although we compared the change in BMI at 3 months and 12 months among groups, there was no significant difference, respectively (Table S3).

Figure 2.

Residual errors of degree of change in hemoglobin A1c (ΔHbA1c). (a) At 3 months. Mean ± standard error, *P < 0.05 (groups compared using the Tukey–Kramer method). (b) At 12 months. Mean ± standard error, not significant.

Discussion

The present study emphasized the month sitagliptin was started in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The results showed that the degree of change in HbA1c in a group in which sitagliptin was started from summer to autumn was unlikely to decrease significantly compared with those of other groups when sitagliptin was started in another season. We previously showed a strong correlation between baseline HbA1c and the amount of change in it (ΔHbA1c)11. Therefore, we analyzed the factors affecting the degree of change in HbA1c after eliminating the effect of baseline HbA1c. In the present study, patients were divided into four groups by the month sitagliptin was started to compare the improvement effect in HbA1c using the mean residual errors between groups. Consequently, comparison at 3 months after starting sitagliptin showed that group 3 (start from August to October) was significantly different from all other groups. This result suggests that the improvement effect in HbA1c by sitagliptin was unlikely to be obtained for group 3 compared with other groups, even after eliminating the effect of baseline HbA1c. Therefore, the sitagliptin start month is considered to impact the improvement effect in HbA1c 3 months later. However, the comparison at 12 months after starting sitagliptin showed no significant intergroup difference in improvement. This year‐round result suggests that sitagliptin reduces HbA1c equally regardless of the month it is started and effectively treats diabetes mellitus. No significant difference was seen in the HbA1c at 0 months among groups. We selected patients who have not been able to control blood glucose, so we consider that there was no difference as a result of seasonal fluctuation at the beginning of the study.

The reason for the seasonal fluctuation in HbA1c is not entirely clear. Kuroshima et al.13 measured the output of glucagon, a hormone involved in glucose metabolism, for 1 year in 13 healthy men aged 20–42 years and eight healthy women aged 21–37 years. They consequently reported that glucagon output was seasonally variable, with a higher level in winter and a lower level in summer13. One proposed explanation is that exercise habits and dietary intake are involved in the seasonal fluctuation. Kanamori et al.14 administered a questionnaire about diet/exercise therapy in a group in which HbA1c was stable after sitagliptin administration and a group in which HbA1c re‐ascended at the beginning of winter after its administration. They consequently reported that many responders in the group in which HbA1c re‐ascended at the beginning of winter could not comply with diet/exercise therapy. We also compared changes in BMI. However, there was no difference depending on seasons. We found that the seasonal difference in HbA1c change is not necessarily the same as the seasonal change in bodyweight. Shimoya et al.4 reported that body fat and HbA1c levels were increased in winter and decreased in summer without any appreciable change in bodyweight. That study also supports the present results. A correlation between HbA1c and mean ambient temperature was reported in a study showing the seasonal fluctuation in HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus1. Although lifestyle is the most important factor affecting HbA1c variations at the individual level, particular temperature‐related physiological or metabolic factors are estimated to affect population‐level variations.

In the present study, although differences in the degree of change in HbA1c after 3 months occurred depending on the time of the start of sitagliptin, the degree of change in HbA1c was equal in all groups after 1 year. When a long‐term investigation was carried out, sitagliptin start timing did not affect the drug's effect on blood glucose improvement. However, when the improvement effect of blood glucose was evaluated in a short‐term investigation (3 months), sitagliptin was a drug whose effect decreased when it was started in the summer to control a high baseline HbA1c level.

The subanalysis of the present study showed that the effect of sitagliptin on HbA1c improvement differed by the month of beginning administration. However, there were some limitations. This result might apply to other antidiabetic agents as well. It is not clear whether this phenomenon occurs for sitagliptin only, because no data based on the month (season) of initial administration for other drugs was available. The present study was an exploratory analysis, and the number of cases varied among groups, because this was not a strict comparative study with patient assignments. In addition, as no investigation of individual dietary and exercise habits was carried out, the causal relationship between these factors and increases or decreases in HbA1c could not be inferred. In this study, as we did not collect information about the start administration date of other diabetic medicine, we could not carry out the same analysis between seasonal fluctuation of HbA1c and other drugs. Ishii et al.5 reported that the amount of exercise decreased and HbA1c might rise during the winter in the countryside because they were engaged in agriculture. However, the JAMP Study was mainly carried out in Tokyo (an urban area). Therefore, the results obtained in the present study might not apply to other areas, different cultures or different climates.

In conclusion, we showed the difference in the effect of HbA1c by improvement based on the month of sitagliptin initial administration. Although the detailed mechanism is not clear, particular physiological or metabolic factors related to changes in ambient temperature are estimated to be involved in the variation. The results of the present study provide important evidence of the existence of seasonal fluctuations in the therapeutic effect of hypoglycemic agents in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Therefore, we propose that the seasonal fluctuation of effect of antidiabetic drugs by the month of beginning administration should be considered.

Disclosure

This study was funded by the Japan Diabetes Foundation. Hiroshi Sakura received honoraria from Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation and research grant from Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1 | Study design. †Criteria on poor glycemic control: hemoglobin A1c of ≥6.9%, or fasting blood glucose of ≥130 mg/dL. ‡Study‐specific test (arbitrary): glycoalbumin, 1.5 anhydroglucitol, C‐peptide and proinsulin‐to‐insulin ratio. SU, sulfonylurea.

Figure S2 | Patient flow. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Figure S3 | Correlation between baseline hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level and degree of change in HbA1c (ΔHbA1c) at 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin.

Table S1 | (a) Multiple regression analyses of ∆HbA1c levels as the dependent variable at 3 months (factors: group, HbA1c at 0 months, BMI at 0 months, and usage of medium‐dose of glimepiride). (b) Multiple regression analyses of ∆HbA1c levels as the dependent variable at 12 months (factors: group, HbA1c at 0 months, BMI at 0 months, and usage of medium‐dose of glimepiride)

Table S2 | Residual errors of ΔHbA1c at 12 months with the patients without drug change after 3 to 12 months

Table S3 | Change in BMI at 3 and 12 months

Acknowledgments

We express our sincere gratitude to Mr Shogo Shishikura (MSD K.K.; Teikyo University Graduate School of Public Health, MPH) for scientific advice including references for revising the manuscript. We also thank Nouvelle Place Inc. for carrying out the data analyses.

Appendix 1. JAMP Study Investigators.

Akiko Sato (Maruyama Internal Medicine Clinic); Akira Miyashita (Miyashita Surgery Clinic); Asako Kokubo (Kokubo Clinic); Atsuro Tsuchiya (Tsuchiya Clinic); Dai Hirohara (Hanazono Clinic); Daiji Kogure (Kogure Clinic); Daijo Kasahara (Kasahara Clinic); Hideki Tanaka (Internal Medicine, Seiwa Clinic); Hideki Tanaka (Internal Medicine, Nishiarai Hospital); Hideo Tezuka (Tezuka Clinic); Hiroyuki Kuroki (Internal Medicine, Johsai Hospital); Jun Ogino (Department of Diabetes, Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Tokyo Women's Medical University Yachiyo Medical Center); Kanu Kin (Internal Medicine, Nishiarai Lifestyle‐Related Diseases Clinic); Kanu Kin (Internal Medicine, Nishiarai Hospital); Kazuko Muto (Tokyo Women's Medical University); Kazuo Suzuki (Kenkokan Suzuki Clinic of Internal Medicine); Keiko Iseki (Iseki Clinic); Keita Watanabe (Watanabe Clinic); Kenshi Higami (Higami Hospital); Kenzo Matsumura (Matsumura Gastroenterological Clinic); Kiyotaka Nakajima (Ebisu Clinic); Koki Shin (Shin Clinic); Kuniya Koizumi (Kuniya Clinic); Maki Saneshige (Mugishima Medical Clinic); Makio Sekine (Sekine Clinic); Makoto Yaida (Urban Heights Clinic); Mari Kiuchi (Physician, Kanauchi Medical Clinic); Mari Mugishima (Mugishima Medical Clinic); Mari Osawa (Department of Diabetes Mellitus, Institute of Geriatrics, Tokyo Women's Medical University); Masae Banno (Banno Medical Clinic); Masahiro Yamamoto (Internal Medicine 1, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine); Masatake Hiratsuka (Higashishinagawa Clinic); Masumi Hosoya (Yasui Clinic); Michika Atsuta (Internal Medicine, Nishiarai Lifestyle‐Related Diseases Clinic); Mitsutoshi Kato (Kato Clinic of Internal Medicine); Miwa Morita (Internal Medicine 1, Shimane University Faculty of Medicine); Munehiro Miyamae (Johsai Hospital); Mutsumi Iijima (Abe Hospital); Naomi Okuyama (Shinjuku Mitsui Building Clinic); Nobuo Hisano (Mejiro Medical Clinic); Norihiro Tsuchiya (Omotesando Naika Ganka); Rie Wada (Kanauchi Medical Clinic); Rie Wada (Nerimasakuradai Clinic); Ryuji Momose (Momo Medical Clinic); Sachiko Otake (Tokyo Women's Medical University); Satoko Maruyama (Shinjuku Mitsui Building Clinic); Satoru Takada (Internal Medicine, Social Welfare Corporation Shineikai Takinogawa Hospital); Shigeki Dan (Ube Internal Medicine and Pediatrics Hospital); Shigeki Nishizawa (Nishizawa Medical Clinic); Shigeo Yamashita (Department of Diabetes and Endocrinology, JR Tokyo General Hospital); Shingo Saneshige (Internal Medicine, Kamiochiai Shin Clinic); Shinichi Teno (Teno Clinic); Shinji Tsuruta (Diabetic Medicine, Itabashi Chuo Medical Center); Shinobu Kumakura (Kumakura Medical Clinic); Sumiko Kijima (Abe Hospital); Takashi Kondo (Kondo Clinic); Takeo Onishi (Internal Medicine, Onishi Clinic); Taku Kudo (Internal Medicine, Social Welfare Corporation Shineikai Takinogawa Hospital); Tatsushi Sugiura (Internal Medicine, Seiwa Clinic); Toshihiko Ishiguro (Kaname Clinic); Yasue Suzuki (Suzuki Medical Clinic); Yasuhiro Tomita (Nakanobu Clinic); Yasuko Takano (Department of Diabetes, Shiseikai Daini Hospital); Yoshihisa Akimoto (Akimoto Yoshi Medical Clinic); Yoshiko Odanaka (Ito Internal Medicine Pediatrics Clinic); Yoshimasa Tasaka (Tokyo Women's Medical University); Yoshitaka Aiso (Internal Medicine, Diabetes, Aiso Clinic); Yukiko Inoue (Inoue Medical Clinic); Yukinobu Kobayashi (Kobayashi Clinic).

J Diabetes Investig 2018; 9: 1159–1166

A complete list of the JAMP (Januvia Multicenter Prospective Trial in Type 2 Diabetes) Study Investigators is provided in Appendix 1.

Clinical Trial Registry

University Hospital Medical Information Network

UMIN000019154

Contributor Information

Hiroshi Sakura, Email: hsakura.dmc@twmu.ac.jp.

the JAMP Study Investigators:

Akiko Sato, Akira Miyashita, Asako Kokubo, Atsuro Tsuchiya, Dai Hirohara, Daiji Kogure, Daijo Kasahara, Hideki Tanaka, Hideki Tanaka, Hideo Tezuka, Hiroyuki Kuroki, Jun Ogino, Kanu Kin, Kanu Kin, Kazuko Muto, Kazuo Suzuki, Keiko Iseki, Kenshi Higami, Kenzo Matsumura, Kiyotaka Nakajima, Koki Shin, Kuniya Koizumi, Maki Saneshige, Makio Sekine, Makoto Yaida, Mari Kiuchi, Mari Mugishima, Mari Osawa, Masae Banno, Masahiro Yamamoto, Masatake Hiratsuka, Masumi Hosoya, Michika Atsuta, Mitsutoshi Kato, Miwa Morita, Munehiro Miyamae, Mutsumi Iijima, Naomi Okuyama, Nobuo Hisano, Norihiro Tsuchiya, Rie Wada, Rie Wada, Ryuji Momose, Sachiko Otake, Satoko Maruyama, Satoru Takada, Shigeki Dan, Shigeki Nishizawa, Shigeo Yamashita, Shingo Saneshige, Shinichi Teno, Shinji Tsuruta, Shinobu Kumakura, Sumiko Kijima, Takashi Kondo, Takeo Onishi, Taku Kudo, Tatsushi Sugiura, Toshihiko Ishiguro, Yasue Suzuki, Yasuhiro Tomita, Yasuko Takano, Yoshihisa Akimoto, Yoshiko Odanaka, Yoshimasa Tasaka, Yoshitaka Aiso, Yukiko Inoue, and Yukinobu Kobayashi

References

- 1. Sakura H, Tanaka Y, Iwamoto Y. Seasonal fluctuations of glycated hemoglobin levels in Japanese diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010; 88: 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Iwao T, Sakai K, Ando E. Seasonal fluctuations of glycated hemoglobin levels in Japanese diabetic patients: effect of diet and physical activity. Diabetol Int 2013; 4: 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwata K, Iwasa M, Nakatani T, et al Seasonal variation in visceral fat and blood HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2012; 96: e53–e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sohmiya M, Kanazawa I, Kato Y. Seasonal changes in body composition and blood HbA1c levels without weight change in male patients with type 2 diabetes treated with insulin. Diabetes Care 2004; 27: 1238–1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ishii H, Suzuki H, Baba T, et al Seasonal variation of glycemic control in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2001; 24: 1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang L, Li W, Xian T, et al Seasonal variations of hemoglobin A1c in residents of Beijing, China. Int Clin Exp Pathol 2016; 9: 9429–9435. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pereira MT, Lira D, Bacelar C, et al Seasonal variation of haemoglobin A1c in a Portuguese adult population. Arch Endocrinol Metab 2015; 59: 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim YJ, Park S, Yi W, et al Seasonal variation in hemoglobin a1c in Korean patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Korean Med Sci 2014; 29: 550–555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gikas A, Sotiropoulos A, Pastromas V, et al Seasonal variation in fasting glucose and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes. Prim Care Diabetes 2009; 3: 111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Matsuhashi T, Sano M, Fukuda K, et al Sitagliptin counteracts seasonal fluctuation of glycemic control. World J Diabetes 2012; 3: 118–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sakura H, Hashimoto N, Sasamoto K, et al Effect of sitagliptin on blood glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus who are treatment naive or poorly responsive to existing antidiabetic drugs: the JAMP study. BMC Endocr Disord 2016; 16: 70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Committee of the Japan Diabetes Society on the Diagnostic Criteria of Diabetes Mellitus , Seino Y, Nanjo K, et al Report of the committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2010; 1: 212–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kuroshima A, Doi K, Ohno T. Seasonal variation of plasma glucagon concentrations in men. Jpn J Physiol 1979; 29: 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kanamori A, Matsuba I. Factors associated with reduced efficacy of sitagliptin therapy: analysis of 93 patients with type 2 diabetes treated for 1.5 years or longer. J Clin Med Res 2013; 5: 217–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1 | Study design. †Criteria on poor glycemic control: hemoglobin A1c of ≥6.9%, or fasting blood glucose of ≥130 mg/dL. ‡Study‐specific test (arbitrary): glycoalbumin, 1.5 anhydroglucitol, C‐peptide and proinsulin‐to‐insulin ratio. SU, sulfonylurea.

Figure S2 | Patient flow. HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c.

Figure S3 | Correlation between baseline hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level and degree of change in HbA1c (ΔHbA1c) at 3 and 12 months after starting sitagliptin.

Table S1 | (a) Multiple regression analyses of ∆HbA1c levels as the dependent variable at 3 months (factors: group, HbA1c at 0 months, BMI at 0 months, and usage of medium‐dose of glimepiride). (b) Multiple regression analyses of ∆HbA1c levels as the dependent variable at 12 months (factors: group, HbA1c at 0 months, BMI at 0 months, and usage of medium‐dose of glimepiride)

Table S2 | Residual errors of ΔHbA1c at 12 months with the patients without drug change after 3 to 12 months

Table S3 | Change in BMI at 3 and 12 months