Abstract

Inflammatory pathway from hyperglycemia to diabetic peripheral neuropathy is very important in diagnosis and management. Inflammatory cytokine can be used for prediction and progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy.

Diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN) is the most common chronic neurological complication of diabetes1. Small and large peripheral nerve fibers can be involved in DPN. Large nerve fiber damage causes paresthesia, sensory loss and muscle weakness, and small nerve fiber damage is associated with pain, anesthesia, foot ulcer and autonomic symptoms. However, the exact pathogenic mechanisms and diagnostic criteria for DPN are currently not firmly established. The present DPN prevention, diagnosis and treatment strategies are incomplete and unsuccessful due to the various forms of pathogenesis of systemic and cellular disturbance in glucose and lipid metabolism. These abnormalities lead to the activation of complex biochemical pathways, including increased oxidative–nitrosative stress, activation of the polyol and protein kinase C pathways, activation of poly adenosine diphosphate ribosylation, and activation of genes involved in neuronal damage, cyclooxygenase‐2 activation, endothelial dysfunction, altered Na+/K+‐adenosine triphosphatase pump function, impaired C‐peptide‐related signaling pathways, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and low‐grade inflammation2. From these pathophysiological factors responsible for DPN, oxidative–nitrosative stress and inflammation are the most extensively studied pathways.

Low‐grade inflammation is an activation of innate immune system response. Clinically, low‐grade inflammation is defined as a marked increase of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines concentration and other biomarkers that activate the immune system. Chronic low‐grade inflammation increases the risk for atherosclerosis, type 2 diabetes, neurodegeneration and tumor growth. Also, it leads to reducing the functional capacity and longevity of life. Important prospective clinical trials have shown that circulating inflammatory markers and pro‐inflammatory cytokines are strongly associated with the risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Recently, evidence that long‐term low‐grade inflammation has an important role in the DPN pathogenesis has emerged from many experimental and clinical studies. Clinical trials in DPN patients with pain and without pain showed that the DPN with pain group had higher inflammation markers. Furthermore, DPN patients with pain and had more increased cytokine concentration compared with DPN patients without pain3. Another small cross‐sectional study4 showed that interleukin (IL)‐6 and IL‐10 were raised in some DPN patients, and correlated with abnormalities in large nerve fibers. IL‐10 is considered to be an anti‐inflammatory cytokine. Therefore, increased IL‐10 in that study was regarded as a compensatory mechanism.

Increased levels of IL‐6, IL‐1, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α and transforming growth factor‐β are correlated with the progression of nerve degeneration in DPN3.

In DPN, nuclear factor‐2 erythroid‐related factor 2, which drives the production of endogenous anti‐oxidant and detoxifying enzymes, expression was decreased, and nuclear factor‐kappa light chain enhancer of B cells, which is involved in pro‐inflammatory cytokine production, was increased. It can lead to inflammation and increased oxidative–nitrosative stress, and cause nerve damage, impaired blood supply to nerves, pain hypersensitivity and nerve apoptosis5.

Four years ago, in a large cohort of older adults in the population‐based cross‐sectional Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg F4 study, it was reported that serum concentrations of several inflammatory cytokines, including IL‐1 receptor antagonist (IL‐1RA), which represent a compensatory upregulation in response to induction of IL‐1β and IL‐6, were positively associated with measures of DPN in age‐ and sex‐adjusted analyses. Due to limitations of that study, prospective and intervention studies for all age groups are required to clarify the sequence and causality of the relationship between low‐grade inflammation and DPN.

In 2017, Herder et al.6 reported that systemic inflammation predicted both the onset and progression of DPN over 6.5 years for the large population of older adults in the Cooperative Health Research in the Region of Augsburg F4/FF4 cohort prospective study. Elevated plasma high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, IL‐6, TNF‐a, IL‐1RA and soluble intracellular adhesion molecule‐1 (ICAM‐1), and decreased adiponectin concentrations were associated with incident DPN. After adjustment for known DPN risk factors, increased IL‐6 and TNF‐α remained associated with incident DPN. Higher plasma soluble ICAM‐1 and IL‐1RA were associated with the progression of DPN6.

Pro‐inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF‐α, IL‐1, IL‐6, IL‐8, monocyte chemoattractant protein‐1 and C‐reactive protein, are mainly produced by activated immune cells, resident macrophages and adipocytes. In addition to these inflammatory molecules, circulating and locally produced ICAM‐1, vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1, E‐selectin and chemokines have increased expression in diabetes and DPN, and have been shown to be associated with the development and progression of DPN only by cross‐sectional trials. Although, in this prospective study6, it was reported that IL‐6 and TNF‐α elevation increased DPN development, and elevation of the levels of these systemic cytokines is not specific to DPN, but is observed in cardiovascular disease, obesity and other diabetic complications, such as diabetic nephropathy. Therefore, we should confirm the difference in systemic cytokine change between DPN and other low‐grade inflammatory disease6.

The biomarker data showing which cytokines are involved in DPN progression are limited. Herder et al.6 suggested that soluble ICAM‐1 and IL‐1RA can be used as biomarkers for DPN progression. Cell adhesion molecules (vascular cell adhesion molecule‐1, ICAM‐1) activation and elevation in endothelial cells induce the release of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, and promote the inflammatory response and the progression of DPN and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, increased cell adhesion molecules expression must be ruled out for comorbid disease and complications.

IL‐1RA, an anti‐inflammatory cytokine, is induced by IL‐1β and blocks the pro‐inflammatory cytokine action of IL‐1β at IL‐1 receptor I. IL‐1RA can be easily measured compare with IL‐1β, and systemic levels of IL‐1RA are elevated in obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes patients. Therefore, the balance between IL‐1RA and IL‐1β is an important mechanism to prevent the development and progression of high cardiovascular risk patients. In DPN, increased IL‐1RA levels reflect compensatory upregulation in response to IL‐1β dysregulation with low‐grade inflammatory diseases. Recombinant IL‐1RA and IL‐1β inhibitor used in clinical trials were required for clarification of the inflammatory process role in the progression of DPN7.

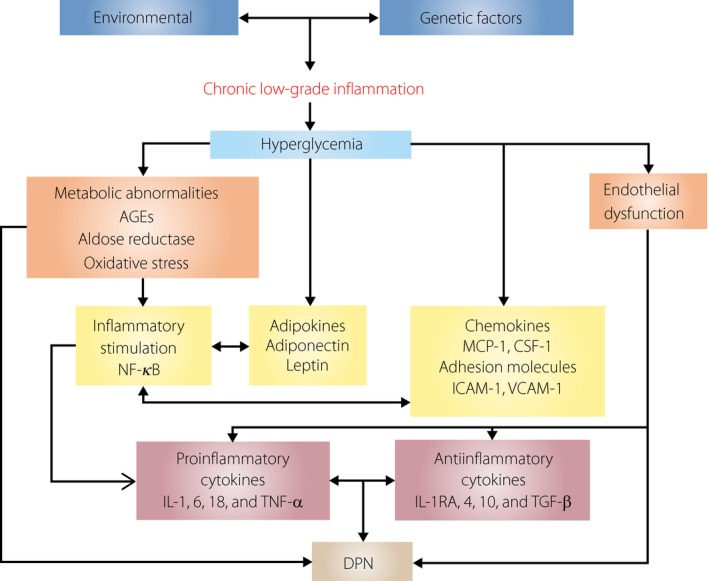

Recently, many studies have been shown to support the associations between prediabetes, diabetes mellitus, inflammation and DPN. It is now clear that chronic low‐grade inflammation is one of the critical pathways in the development and progression of DPN, and that the inflammatory environment in type 2 diabetes mellitus contributes significantly to the development of many of the complications of this disease, including DPN. The relationships between this inflammatory state and the development and progression of DPN involve very complex network processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inflammatory pathway from hyperglycemia to diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN). AGEs, advanced glycation end‐products; CSF, colony‐stimulating factor; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IL, interleukin; MCP, monocyte chemoattractant protein; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐kappa light chain enhancer of B cells; TGF, transforming growth factor beta; TNF‐α, tumor necrosis factor alpha; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Multiple inflammatory molecules play important roles in this complex signaling pathway, including pro‐inflammatory cytokines, adipokines, chemokines and adhesion molecules. At the present time, current management of DPN is still disappointing and unsatisfactory, both in preventing its development, and in halting and modifying its progression. A more accurate and clearer understanding of the role of inflammatory molecules and processes in the context of DPN will facilitate the development of early and correct diagnostic biomarkers. This will lead to new and improved therapeutic strategies that can be successfully applied to clinical applications for DPN.

References

- 1. Tesfaye S, Boulton AJM, Dickenson AH. Mechanisms and management of diabetic painful distal symmetrical polyneuropathy. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2456–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pop‐Busui R, Ang L, Holmes C. Inflammation as a therapeutic target for diabetic neuropathies. Curr Diab Rep 2016; 16: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doupis J, Lyons TE, Wu S, et al Microvascular reactivity and inflammatory cytokines in painful and painless peripheral diabetic neuropathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 2157–2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Magrinelli F, Briani C, Romano M, et al The association between serum cytokines and damage to large and small nerve fibers in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Diabetes Res 2015; 2015: 547834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ganesh Yerra V, Negi G, Sharma SS, et al Potential therapeutic effects of the simultaneous targeting of the Nrf2 and NF‐κB pathways in diabetic neuropathy. Redox Biol 2013; 1: 394–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Herder C, Kannenberg JM, Huth C, et al Proinflammatory cytokines predict the incidence and progression of distal sensorimotor polyneuropathy: KORA F4/FF4 study. Diabetes Care 2017; 40: 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Herder C, de Las Heras Gala T, Carstensen‐Kirberg M, et al Circulating levels of interleukin 1‐receptor antagonist and risk of cardiovascular disease: meta‐analysis of six population‐based cohorts. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017; 37: 1222–1227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]