Abstract

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in neonates. Therapeutic hypothermia reduces the risk of death or disability. Providing optimal sedation while neonates are undergoing therapeutic hypothermia is likely beneficial but may present therapeutic challenges. There are limited data describing the use of dexmedetomidine for sedation in patients undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficacy and short-term safety of dexmedetomidine infusion for sedation in term neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia for HIE.

Keywords: hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, sedation, dexmedetomidine, neonate

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in neonates. The incidence of HIE ranges from 1 to 8 per 1,000 live births in developed countries to as high as 26 per 1,000 live births in underdeveloped countries. 1 Therapeutic hypothermia reduces the risk of death or disability including cerebral palsy, mental retardation, learning disabilities, or epilepsy in infants with moderate or severe HIE. 2 3 4

Although it is unknown whether analgesic infusions during hypothermia reduce the stress response associated with hypothermia in human neonates, some randomized trials of hypothermia consistently used opiates. 5 Providing optimal sedation while neonates are undergoing therapeutic hypothermia may be beneficial but also presents therapeutic challenges. Animal data suggest that the positive effect of therapeutic hypothermia on HIE is negated when used alone versus in conjunction with morphine infusion. Although physiologic differences between a piglet and human response to hypothermia may exist, higher cortisol levels in the unsedated piglets may suggest that blunting the stress response and shivering contribute to the overall neuroprotection offered by therapeutic hypothermia with sedation. 6 In neonates with HIE who did not receive therapeutic hypothermia, those who received opioid analgesia had significantly less brain injury in all regions studied using magnetic resonance imaging despite having more severe ischemic insults compared with infants who did not receive opioids. 7 These results should be balanced with animal data which demonstrated reduced survival and no significant differences in the volume of brain injury in a rodent model of hypoxia-ischemia. 8 Use of opioids to provide sedation during hypothermia may be associated with unwanted effects such as hypotension, respiratory depression, and gastrointestinal dysmotility.

Alpha-2 adrenergic receptor agonist use in neonates is becoming more commonplace as a means of providing sedation and analgesia without compromising respiratory function and has less effect on gastrointestinal motility compared with narcotics. Additional potential benefits of dexmedetomidine use include prevention of shivering during therapeutic hypothermia, neuroprotection during periods of ischemia/hypoxia, decreased proapoptotic factors, and increased expression of active focal adhesion kinase that plays a role in cellular plasticity and survival. 9

Animal neonatal models of hypoxic-ischemic injury suggest that α agonists such as dexmedetomidine may play a beneficial role in HIE, acting as potent neuroprotectors via stimulation of the α-2A adrenoreceptors. Exposure to dexmedetomidine following perinatal hypoxia-ischemia appears to reduce cortical and white matter lesion sizes. 10 11 It has also been shown to exhibit dose-dependent protection against brain matter loss and improved neurologic functional deficit induced by a hypoxic-ischemic insult. 12

There are limited data describing the use of dexmedetomidine in patients undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. One case series in two pediatric brain trauma patients suggested that the addition of hypothermia to sedation regimens of dexmedetomidine and remifentanil resulted in clinically significant bradycardia. 11 A neonatal piglet model of HIE showed significantly decreased dexmedetomidine clearance in the setting of hypothermia, leading to increased episodes of bradycardia, hypertension, and cardiac arrest. The objective of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness and short-term safety of dexmedetomidine infusion for sedation in term neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia for HIE.

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective chart review of neonates admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit at University of Florida Health Shands Hospital between July 2013 and October 2016. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board. Infants were eligible for study inclusion if they had a diagnosis of HIE requiring therapeutic hypothermia and received intravenous dexmedetomidine within 48 hours of birth. Entry criteria for hypothermia includes a gestational age of 35 weeks or greater, birth weight of 1.8 kg or greater, and less than or equal to 6 hours of age. Enrolled neonates had evidence of encephalopathy as defined by seizures or abnormalities on a modified Sarnat exam (level of consciousness, spontaneous activity, posture, tone, primitive reflexes including suck and Moro, autonomic system findings including pupil dilation and reactivity, heart rate [HR], and respirations). 4 Evidence of hypoxic-ischemic injury was defined by a pH of 7.0 or less and/or a base deficit of greater than 16, or a pH between 7.01 and 7.15 and/or a base deficit between 10 and 15.9, or no blood gas available and an acute perinatal event (cord prolapse, HR decelerations, or uterine rupture). 4 Patients were excluded if they had major congenital anomalies incompatible with life or dexmedetomidine was used outside of the treatment window.

During hypothermia, all neonates undergo continuous video electroencelphographic monitoring for the 72 hours of hypothermia and 24 hours after rewarming. Nurses assess pain and agitation using the Neonatal Pain, Agitation and Sedation Scale (N-PASS). Fentanyl or dexmedetomidine are started at the initiation of hypothermia as a continuous infusion. Fentanyl is started at a dose of 0.5 mcg/kg/hour and increased by 0.5 mcg/kg/hour increments. If fentanyl is used as the primary agent and the dose reaches 1 mcg/kg/hour, dexmedetomidine is added as a second sedative. Dexmedetomidine is preferentially used in spontaneously breathing patients and is started at 0.3 mcg/kg/hour. The doses are titrated by 0.1 to 0.2 mcg/kg/hour as needed. Fentanyl or dexmedetomidine is increased if the N-PASS score is elevated, the HR is continuously above 120 beats per minute (bpm) with no other physiologic explanation, or clinical pain/agitation is perceived by the bedside clinician. Sedation is decreased if the neonate has a resting HR below 70, appears oversedated, and/or is not responsive to stimulation. Fentanyl or dexmedetomidine is decreased by 0.1 to 0.2 mcg/kg/hour until clinically acceptable parameters are obtained (HR increases to goal range or the baby becomes responsive to stimuli). Sedation can be stopped for short periods of time and restarted when the HR is greater than 70 bpm and/or the baby responds to stimuli.

Data collection included patient demographics, pertinent medication information, laboratory assessments, and vital signs. The primary objective of the study is to describe the use of dexmedetomidine in neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia for HIE. Clinical outcomes include dosing information and need for supplemental analgesics or sedatives. Safety analysis includes the evaluation of hemodynamics including mean arterial pressures, HR, cerebral saturations, and need for new or increased vasopressor support after dexmedetomidine initiation. Additional outcomes include feeding tolerance, duration of central intravenous access, and duration of mechanical ventilation. Descriptive statistics are used to evaluate data.

Results

Demographics

Nineteen patients were included in the analysis. Demographics are provided in Table 1 . All but one patient survived to discharge. Patients were term gestation, 63% male, and 74% required mechanical ventilation after birth. Approximately half of the patients had hypotension requiring vasopressor support and 42% demonstrated clinical or electrographic evidence of seizure activity during the study period. Of the 8 patients who experienced seizures, only 2 were discharged with antiepileptic medications.

Table 1. Patient demographics.

| Patient characteristics | N = 19 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 38.5 (1.39) |

| Birth weight (kg) | 3.55 (0.88) |

| Male, n (%) | 12 (63) |

| Inborn, n (%) | 11 (57) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 1 (5) |

| APGAR-1 min | 1 (1.3) |

| APGAR-5 min | 4 (2.2) |

| APGAR-10 min | 5 (2.6) |

| Cord pH | 7.01 (0.19) |

| Cord PaO2 | 29.2 (17.9–46.5) |

| Cord PaCO2 | 64.2 (26) |

| Cord base deficit | –17 (7.8) |

| Lactate | 9.8 (5.6) |

| Mechanically ventilated, n (%) | 14 (73.6) |

| Duration mechanical ventilation (d) | 4 (2.5–8.5) |

| Sarnat score | 2 (0.72) |

| Seizures, n (%) | 8 (42) |

| Hypotension, n (%) | 10 (52) |

Abbreviations: APGAR, Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, and Respiration; PaCO2, partial pressure carbon dioxide; PaO2, partial pressures of oxygen.

Sedation Management

Of the 19 patients studied, 2 received dexmedetomidine monotherapy and 17 received combination therapy with fentanyl. Most patients were initiated on fentanyl infusions prior to the start of dexmedetomidine. Time from birth to start of fentanyl and dexmedetomidine infusions were 2.5 (±1.07) and 11.5 (interquartile range [IQR], 6–20.1) hours, respectively ( Table 2 ).

Table 2. Sedation management.

| Dexmedetomidine | Number of patients (%) | 19 (100) |

| Timing of initiation (h of life) | 11.5 (6, –20.1) | |

| Duration (h) | 3.8 (2.6–4.9) | |

| Initial dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | |

| Minimum dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.2 (0.12–0.3) | |

| Maximum dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.5 (0.4–1) | |

| Fentanyl | Number of patients | 17 (89) |

| Timing of initiation (h of life) | 2.51 (1.1) | |

| Duration (h) | 3.3 (0.75–4.9) | |

| Initial dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.5 (0.5–0.75) | |

| Minimum dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.5 (0.3–0.75) | |

| Maximum dose, mcg/kg/h | 0.9 (0.46) |

In 13 of the 17 patients receiving combination therapy, the fentanyl infusion was weaned down within 4 hours of starting dexmedetomidine infusion. No patients required additional boluses of fentanyl or midazolam after starting dexmedetomidine. Fentanyl was discontinued prior to dexmedetomidine in 14 of the 17 patients receiving combination therapy. Of the 13 survivors who required mechanical ventilation, 11 were receiving dexmedetomidine at the time of extubation. Four patients were weaned off the infusion the same day as extubation, and the other patients were weaned off within 48 hours following extubation.

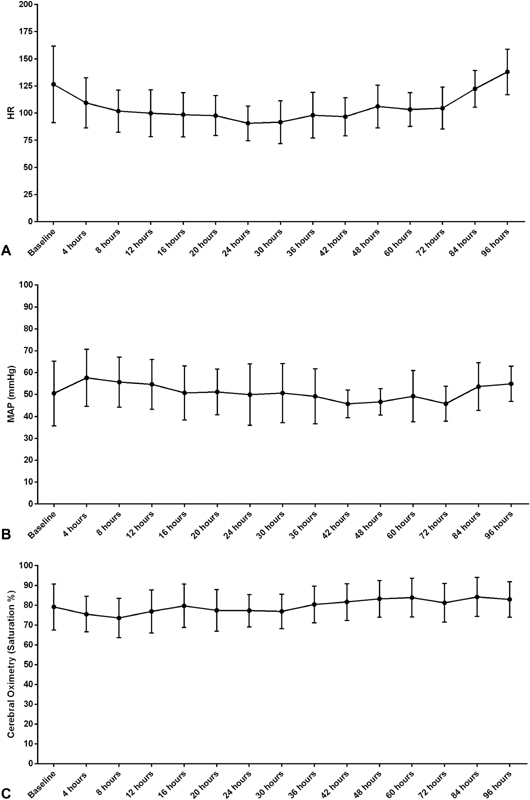

Hemodynamics

Hemodynamic indices are provided in Fig. 1 . Initiation of dexmedetomidine infusion did not appear to negatively impact HR, mean arterial blood pressures, or cerebral saturations. HR instability was noted in one patient who experienced bradycardia (68 bpm) that resolved upon weaning the fentanyl infusion and maintaining the dexmedetomidine dose. No patient experienced new onset hypotension or hypertension. No patient experienced cardiac arrest. Ten of the 19 patients received vasopressors during the study period, but none were started or required an increased in dose after dexmedetomidine initiation.

Fig. 1.

Vital signs over time are shown for a period of 96 hours. The change in the heart rate ( A ), the mean arterial pressure (MAP, B ), and cerebral oximetry ( C ) are shown graphically compared with a baseline vital sign reading prior to infusion of dexmedetomidine. Graphed values represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

Other Outcomes

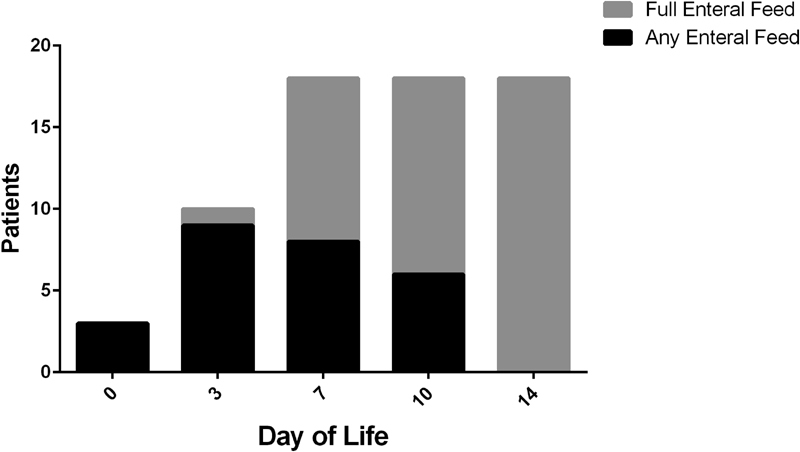

Enteral feeds were initiated as described in Fig. 2 . On days 0, 1, 2, and 3, trophic feeds were initiated in 3 (15%), 5 (26%), 7 (37%), and 12 (63%) patients, respectively. Mean day to enteral feeding initiation was 2.7 days, and full enteral feeds (150 mL/kg/day) were attained by day 6. Duration of parenteral nutrition and central intravenous access were 5.6 and 6.1 days, respectively. All but one survivor was discharged on full oral feeds. For the 17 patients who did not require gastrostomy tube, this was established within 6.6 days of birth.

Fig. 2.

Enteral feeding outcomes. Number of patients receiving any enteral feeds compared with those achieving full enteral feeds over time.

Median duration of mechanical ventilation was 4 days (IQR, 2.5–8.5). Of the 13 survivors who required mechanical ventilation, 11 were receiving dexmedetomidine at the time of extubation. Four patients were weaned off the infusion the same day as extubation, and the other patients were weaned off within 48 hours following extubation.

Discussion

Dexmedetomidine appeared to be well-tolerated in this cohort of patients with HIE requiring therapeutic hypothermia. Dexmedetomidine was primarily used as adjunctive therapy with fentanyl, but a small subset of patients was maintained with dexmedetomidine monotherapy. Fentanyl 0.5 to 1 mcg/kg/hour is the standard initial infusion dose for patients in our unit undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. In most patients receiving combination therapy, fentanyl infusion had been increased from the initial infusion rate prior to starting dexmedetomidine. Addition of dexmedetomidine to the sedation regimen allowed weaning of fentanyl infusions in 76% of patients. Use of dexmedetomidine infusion may minimize the need for adjunctive sedation/opioids in neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Downstream positive effects of this may include decreased respiratory depression and gastric motility issues.

For nonhypothermia patients, our unit begins dexmedetomidine infusion at 0.5 mcg/kg/hour. This subset of patients was empirically started on lower doses to account for potential bradycardia when used in conjunction with hypothermia. 13 14 No patient experienced new onset hypotension, hypertension, or cardiac arrest. Addition of dexmedetomidine to patients receiving vasopressor support did not result in increased vasopressor doses after initiation. Clinically significant bradycardia only occurred in one patient who was receiving fentanyl 1.8 mcg/kg/hour prior to starting dexmedetomidine. This particular patient had a lower HR prior to starting the dexmedetomidine infusion at 0.2 mcg/kg/hour (75 bpm). Upon weaning fentanyl to 0.5 mcg/kg/hour, the patient's HR increased to 84 bpm. The dexmedetomidine infusion rate was not changed during this time. Patients whose baseline HRs was above the goal prior to starting dexmedetomidine infusion were able to be captured and maintained at target HRs (80–100 bpm). Since data are still sparse regarding safe dosing of dexmedetomidine in neonates undergoing therapeutic hypothermia, it may be prudent to limit initial infusion rates to assess response in HRs.

Enteral feeding outcomes revealed shorter duration of parenteral nutrition and time to full oral feeds compared with previously published historical patients in our unit. 15 This hold true even when compared with patients who received minimal enteral nutrition in the absence of dexmedetomidine. Only one patient who survived to discharge required surgical placement of gastrostomy tube for feeds. The other 17 patients were transitioned to oral feeds shortly after initiation of enteral feeds.

Because dexmedetomidine does not have significant effects on respiratory drive, it may present an ideal sedation option in patients requiring therapeutic hypothermia who are not receiving mechanical ventilation. In this cohort, 5 (26%) spontaneously breathing patients received dexmedetomidine infusion and did not subsequently require mechanical ventilation. No patient who required mechanical ventilation was intubated after starting dexmedetomidine. Dexmedetomidine was not associated with any extubation failures and was continued in 11 patients at the time of discontinuation of mechanical ventilation.

In addition to sedative properties, dexmedetomidine may also have neuroprotective properties by interrupting many of the pathophysiologic cascades induced by hypoxic-ischemic injury; thereby making it superior to the opioids for sedation during hypothermia. Dexmedetomidine protects the developing brain from excitotoxicity, a major component of the pathophysiology of HIE, with the protective effect mediated through the α 2a receptor. 11 16 Dexmedetomidine also has neuroprotective properties beyond the α 2a -mediated mechanisms of action. Dexmedetomidine increases the expression of pERK1 and 2, a key enzyme in signal transduction for survival and synaptic plasticity, via the I1-imidazoline receptor. 17 Dexmedetomidine has also been shown to reduce tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 in endotoxin-induced rat models. 18

Based on our experience, dexmedetomidine was effective for sedation in this population of neonates with HIE undergoing therapeutic hypothermia. Dexmedetomidine is used our first-line sedative in neonates who are not mechanically ventilated due to concerns of hypoventilation or apnea with fentanyl. In our experience, the starting dose of dexmedetomidine to safely obtain optimal sedation is 0.3 mcg/kg/hour. In neonates with HIE undergoing hypothermia who are candidates for minimal enteral nutrition, we have found that feeding outcomes have improved with dexmedetomidine compared with fentanyl. 15

Acknowledgment

We thank all families for participating in clinical research, which allows us to continue to improve care for neonates.

Disclosure Statement None.

Statement of Financial Support

Children's Miracle Network.

References

- 1.Kurinczuk J J, White-Koning M, Badawi N. Epidemiology of neonatal encephalopathy and hypoxic-ischaemic encephalopathy. Early Hum Dev. 2010;86(06):329–338. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azzopardi D V, Strohm B, Edwards A D et al. Moderate hypothermia to treat perinatal asphyxial encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(14):1349–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gluckman P D, Wyatt J S, Azzopardi Det al. Selective head cooling with mild systemic hypothermia after neonatal encephalopathy: multicentre randomised trial Lancet 2005365(9460):663–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shankaran S, Laptook A R, Ehrenkranz R A et al. Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(15):1574–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcps050929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wassink G, Lear C A, Gunn K C, Dean J M, Bennet L, Gunn A J. Analgesics, sedatives, anticonvulsant drugs, and the cooled brain. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;20(02):109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thoresen M, Satas S, Løberg E M et al. Twenty-four hours of mild hypothermia in unsedated newborn pigs starting after a severe global hypoxic-ischemic insult is not neuroprotective. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(03):405–411. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200109000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angeles D M, Wycliffe N, Michelson D et al. Use of opioids in asphyxiated term neonates: effects on neuroimaging and clinical outcome. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(06):873–878. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157676.45088.8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Festekjian A, Ashwal S, Obenaus A, Angeles D M, Denmark T K. The role of morphine in a rat model of hypoxic-ischemic injury. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45(02):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAdams R M, Juul S E. Neonatal encephalopathy: update on therapeutic hypothermia and other novel therapeutics. Clin Perinatol. 2016;43(03):485–500. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laudenbach V, Mantz J, Lagercrantz H, Desmonts J M, Evrard P, Gressens P. Effects of alpha(2)-adrenoceptor agonists on perinatal excitotoxic brain injury: comparison of clonidine and dexmedetomidine. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(01):134–141. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200201000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paris A, Mantz J, Tonner P H, Hein L, Brede M, Gressens P. The effects of dexmedetomidine on perinatal excitotoxic brain injury are mediated by the alpha2A-adrenoceptor subtype. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(02):456–461. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000194301.79118.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ma D, Hossain M, Rajakumaraswamy Net al. Dexmedetomidine produces its neuroprotective effect via the alpha 2A-adrenoceptor subtype Eur J Pharmacol 2004502(1-2):87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tobias J D. Bradycardia during dexmedetomidine and therapeutic hypothermia. J Intensive Care Med. 2008;23(06):403–408. doi: 10.1177/0885066608324389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ezzati M, Broad K, Kawano G et al. Pharmacokinetics of dexmedetomidine combined with therapeutic hypothermia in a piglet asphyxia model. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(06):733–742. doi: 10.1111/aas.12318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang L L, Wynn J L, Pacella M J et al. Enteral feeding as an adjunct to hypothermia in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Neonatology. 2018;113(04):347–352. doi: 10.1159/000487848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Douglas-Escobar M, Weiss M D. Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy: a review for the clinician. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(04):397–403. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dahmani S, Paris A, Jannier V et al. Dexmedetomidine increases hippocampal phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 1 and 2 content by an alpha 2-adrenoceptor-independent mechanism: evidence for the involvement of imidazoline I1 receptors. Anesthesiology. 2008;108(03):457–466. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318164ca81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taniguchi T, Kidani Y, Kanakura H, Takemoto Y, Yamamoto K. Effects of dexmedetomidine on mortality rate and inflammatory responses to endotoxin-induced shock in rats. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(06):1322–1326. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000128579.84228.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]