Abstract

Regular consumption of moderate amounts of ethanol has important health benefits on atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). Overindulgence can cause many diseases, particularly alcoholic liver disease (ALD). The mechanisms by which ethanol causes both beneficial and harmful effects on human health are poorly understood. Here we demonstrate that ethanol enhances TGF-β-stimulated luciferase activity with a maximum of 0.5–1% (v/v) in Mv1Lu cells stably expressing a luciferase reporter gene containing Smad2-dependent elements. In Mv1Lu cells, 0.5% ethanol increases the level of P-Smad2, a canonical TGF-β signaling sensor, by ~2-3-fold. Ethanol (0.5%) increases cell-surface expression of the type II TGF-β receptor (TβR-II) by ~2-3-fold from its intracellular pool, as determined by I125-TGF-β-cross-linking/Western blot analysis. Sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation and indirect immunofluorescence staining analyses reveal that ethanol (0.5% and 1%) also displaces cell-surface TβR-I and TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitates translocation of these receptors to non-lipid raft microdomains where canonical signaling occurs. These results suggest that ethanol enhances canonical TGF-β signaling by increasing non-lipid raft microdomain localization of the TGF-β receptors. Since TGF-β plays a protective role in ASCVD but can also cause ALD, the TGF-β enhancer activity of ethanol at low and high doses appears to be responsible for both beneficial and harmful effects. Ethanol also disrupts the location of lipid raft/caveolae of other membrane proteins (e.g., neurotransmitter, growth factor/cytokine, and G protein-coupled receptors) which utilize lipid rafts/caveolae as signaling platforms. Displacement of these membrane proteins induced by ethanol may result in a variety of pathologies in nerve, heart and other tissues.

Keywords: TGF-β ENHANCER, CANONICAL TGF-β SIGNALING, TGF-β RECEPTORS, NON-LIPID RAFT MICRODOMAINS

Ethanol abuse is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in man. Ethanol is the most widely used substance of abuse in the world. It has beneficial effects on inflammatory and immune responses at low doses. Low-dose ethanol is associated with a reduced risk of several diseases including atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [Albert et al., 2003]. However, it exhibits harmful effects at high doses [Albert et al., 2003]. It targets several organs, including liver [Bataller and Brenner, 2005], nerve [Corrao et al., 2004], and heart [Rehm et al., 2003]. Alcohol abuse increases the incidence of infection [Dolganiuc et al., 2006] and impairs adaptive immune responses [Ghare et al., 2011]. Alcohol liver disease (ALD), arguably the most notable disease caused by alcohol abuse, includes three distinct disorders: fatty liver (alcohol-associated hepatic steatosis), alcoholic hepatitis, and cirrhosis [Bataller and Brenner, 2005; Siegmund et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2014]. About 10–20% of heavy drinkers eventually develop cirrhosis. Cirrhosis features irreversible scarring of the liver and eventually results in poor liver function. Some patients with cirrhosis develop hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [Bataller and Brenner, 2005; Siegmund et al., 2005]. In the United States and Canada, cirrhosis is the third most frequent cause of HCC in adults and is commonly due to excessive alcohol consumption. The mechanisms by which ethanol causes both beneficial and harmful effects on human health have been poorly understood. Accumulating evidence now indicates that ethanol-induced alteration of growth factor and cytokine responses contribute in multiple ways to these beneficial and harmful effects [Apte et al., 2005; Crews et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2012]. Understanding the molecular mechanisms by which ethanol induces alteration of growth factor and cytokine responses may lead to health promotion and development of effective strategies for preventing and treating ethanol-induced pathologies. Currently, there are no agents proven to be effective in preventing and treating alcohol-related diseases and disorders, particularly ALD.

Ethanol is relatively unreactive under physiological conditions. It was formerly believed to act as an anesthetic by diffusing into cell membranes, altering membrane fluidity, and function. However, this suggestion was not substantiated because the increase in membrane fluidity caused by a relevant concentration of ethanol is very small [Peoples et al., 1996]. The role of ethanol in modulation of membrane function was not clear until Crowley et al. [2003] reported that neurological adaption (tolerance) to chronic administration of ethanol is associated with increased cholesterol levels in cell membranes. Since lipid rafts/caveolae in plasma membranes are rich in cholesterol [Keller and Simons, 1998], this suggests that ethanol may modulate membrane or membrane protein functions by altering the cholesterol level in lipid rafts/caveolae in plasma membranes. This suggestion is supported by the finding of Szabo et al. [2007] that ethanol acts as an immunomodulatory substance, at least in part, by altering the structure and function of lipid rafts/caveolae via release of cholesterol from plasma membranes.

We hypothesize that ethanol-induced alteration of lipid raft/caveolae structure and function in target cells enhances canonical transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling in these cells. This is analogous to the action of TGF-β enhancers such as cholesterol-lowering agents and cholesterol-depleting agents (which enhance canonical TGF-β signaling by removing cholesterol from lipid rafts/caveolae) [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008], displacing types I and II TGF-β receptors (TβR-I and TβR-II) from the lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains where canonical TGF-β signaling occurs [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. To test this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of ethanol on canonical TGF-β signaling using Mv1Lu cells expressing a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1)-luciferase reporter which contains Smad-responsive elements of the PAI-1 promoter (termed MLE cells) [Abe et al., 1994; Chen et al., 2009]. Mv1Lu cells are a model cell system for testing TGF-β signaling and responses [Abe et al., 1994; Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009].

In this communication, we show that ethanol enhances TGF-β-stimulated PAI-1-luciferase activity in a concentration-dependent manner in MLE cells. We also show that ethanol, a fusogenic substance [Komatsu and Okada, 1995; Chanturiya et al., 1999; Mondal and Sarkar, 2011], induces recruitment of TβR-II from intracellular vesicles to plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae and non-lipid raft microdomains. This is mediated by the ability of ethanol to induce membrane fusion of intracellular vesicles and plasma membranes [Komatsu and Okada, 1995; Chanturiya et al., 1999; Mondal and Sarkar, 2011]. Furthermore, we show that, in Mv1Lu cells, ethanol, which is capable of depleting cholesterol from lipid rafts/caveolae, displaces TβR-I, and TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitates their translocation to non-lipid-raft microdomains where canonical signaling occurs [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. These results suggest that ethanol enhances TGF-β activity by increased localization of TβR-I and TβR-II to non-lipid raft microdomains. Since TGF-β in the circulation is a protective cytokine against atherosclerosis [Grainger and Metcalfe, 1995], the TGF-β enhancer activity of ethanol at low doses appears to be responsible for certain beneficial effects (prevention of ASCVD and other diseases) [Albert et al., 2003; Holmes and Dale et al., 2014]. TGF-β is also known to be critically involved in the pathogenesis of ALD [Breitkopf et al., 2005; Dooley and ten Dijke, 2012]. Our findings suggest that the TGF-β enhancer activity of ethanol is responsible, at least in part, for the disease. These results may also explain the broad spectrum of ethanol-related pathologies because, like cholesterol-depleting agents [Chen et al., 2007, 2008], ethanol causes structural and functional alterations of lipid rafts/caveolae [Dolganiuc et al., 2006; Szabo et al., 2007], resulting in displacement of TGF-β receptors and other important membrane receptors from lipid rafts/caveolae and their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains. The lipid rafts/caveolae are utilized as signaling platforms by many membrane proteins (e.g., neurotransmitter receptors and G protein-coupled receptors) to mediate important physiological processes [Luo and Miller, 1999; Ghiselli et al., 2003; Hiney et al., 2003; Radek et al., 2008; Assaife-Lopes et al., 2010; Nothdurfter et al., 2013; Cuddy et al., 2014]. Complete displacement of these membrane proteins induced by ethanol at large doses from lipid rafts/caveolae thus results in a variety of pathologies in nerve, heart and other tissues [González-Reimers et al., 2014].

RESULTS

ETHANOL ENHANCES CANONICAL TGF-β SIGNALING (Smad2-DEPENDENT)

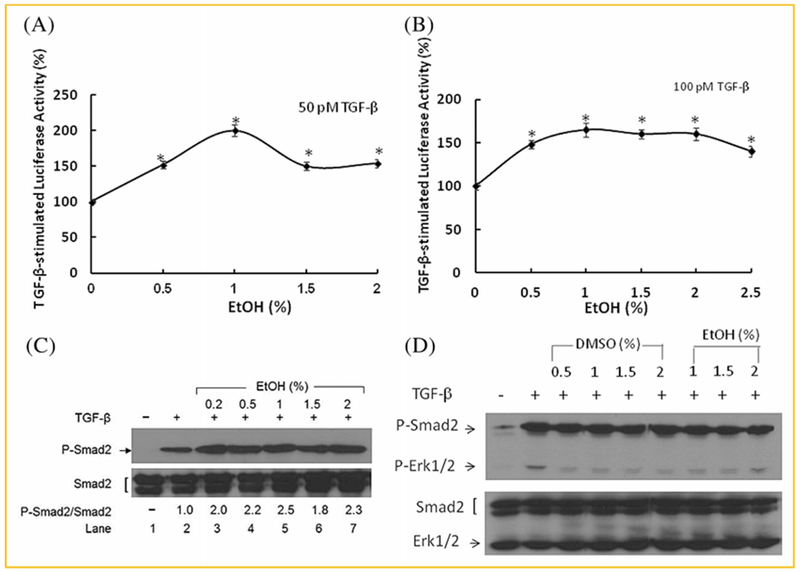

To test the hypothesis that ethanol may enhance TGF-β activity, which is mediated by canonical Smad-dependent signaling, we determined the effect of ethanol on TGF-β-stimulated luciferase activity in MLE cells [Abe et al., 1994]. MLE cells are Mv1Lu cells stably expressing a canonical TGF-β signaling-dependent PAI-1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor-1) promoter-driven luciferase reporter (PAI-1-luc). After incubation of MLE cells with 50 and 100 pM TGF-β in the presence of several concentrations (0. 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0%, v/v) of ethanol at 37°C for 5 h, the luciferase activity in the cell lysates was determined. As shown in Figure 1A and B, ethanol enhanced TGF-β-stimulated luciferase activity in a concentration-dependent manner (maximum of ~2-fold at 1%, v/v). Ethanol-related compounds such as acetaldehyde, methyl alcohol, propyl alcohol, and butyl alcohol do not significantly affect the TGF-β-stimulated luciferase activity in MLE cells (data not shown). The apparent Kd of TGF-β binding to TGF-β receptors was identical (~25 pM) in Mv1Lu cells treated with and without 1% (v/v) ethanol (Huang et al. [2003], data not shown). These results suggest that ethanol enhances TGF-β-stimulated canonical signaling and cellular responses without altering the affinity of TGF-β binding to TGF-β receptors. The specificity of the effect of ethanol on canonical TGF-β signaling is supported by the observation that, at 1% (v/v), ethanol enhanced TGF-β-stimulated phosphorylation of Smad2 by ~2-3-fold (Fig. 1C) but did not have stimulatory effects on TGF-β-stimulated phosphorylation of Erk-1/2, an indicator of non-canonical TGF-β signaling. In contrast, like DMSO, an enhancer of canonical TGF-β signaling [Huang et al., 2015], ethanol at 1%, 1.5%, and 2% (v/v) inhibited TGF-β-stimulated phosphorylation of Erk-1/2 (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Ethanol enhances TGF-β-stimulated luciferase activity in MLE cells (A, B) and TGF-β-stimulated phosphorylation of Smad2 in Mv1Lu cells (C, D). (A, B) MLE cells were treated with 50pM (A) and 100pM (B) of TGF-β in the presence of several concentrations (0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5%, v/v) of ethanol (EtOH). The luciferase activity of the lysates from treated cells was determined. β-actin in the cell lysates was used as an internal control. The luciferase activity of the lysates of treated cells was measured. The luciferase activity in cells treated with TGF-β alone was taken as 100%. In the absence of TGF-β, ethanol at 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, or 2.0% did not stimulate the luciferase activity. The experiments were performed in triplicate. The data is the representative of three independent analyses and values are mean ± s.d. *Significantly higher than that in cells treated with TGF-β alone:P <0.05. (C,D): Mv1Lu cells were treated with 100pM TGF-β in the presence of several concentrations of ethanol (EtOH) (0%, 0.2%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, and 2.0%, v/v) for 45 min. The levels of phosphorylated Smad2 (P-Smad2) and Smad2 (C), and phosphorylated ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2) and ERK1/2 (bottom) (D) were determined by Western blot analysis. Representative illustrations from three independent experiments are shown. The ratio of P-Smad2/Smad2 or P-ERK1/2/ERK1/2 in cells treated with TGF-β alone is taken as one-fold. The data are representative of three independent analyses. The ratios (mean ± s.d.) of P-Smad2/Smad2 in cells treated with TGF-β only, TGF-β + 0.2%, TGF-β + 0.5%, TGF-β + 1%, TGF-β + 1.5%, and TGF-β + 2% were estimated to be 1 ± 0.1, 1.9 ± 0.1*, 2.2 ± 0.1*, 2.5 ± 0.1*, 2.0 ± 0.2*, and 2.4 ± 0.2*, respectively. *Significantly higher than that in cells treated with TGF-β only: P < 0.05.

ETHANOL INCREASES CELL-SURFACE EXPRESSION OF TGF-β RECEPTORS FROM THEIR INTRACELLULAR POOLS

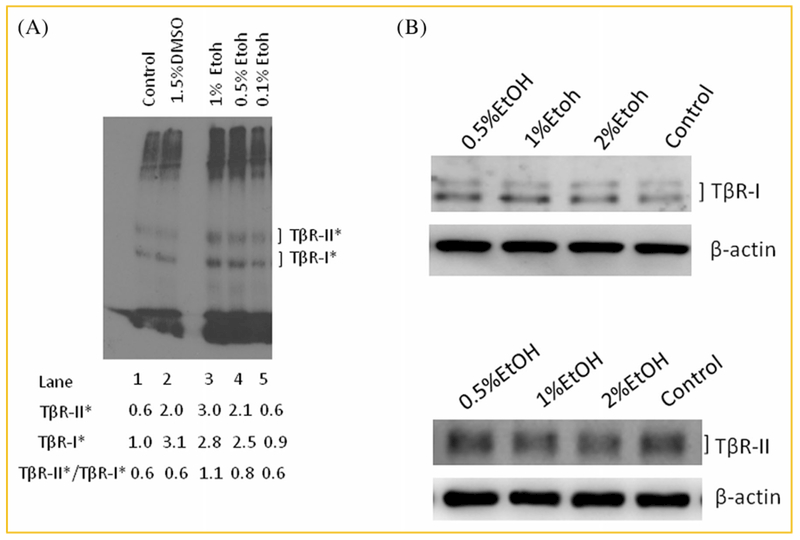

Ethanol treatment does not affect the affinity of TGF-β binding to TGF-β receptors in Mv1Lu cells but it may enhance canonical TGF-β signaling by altering the cell-surface expression and/or plasma-membrane microdomain localization of TGF-β receptors (TβR-I and TβR-II) in these cells. These two processes have been recently shown to play an important role in modulating TGF-β activity in all cell types studied [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. To test this possibility, we determined the cell-surface expression of TβR-I and TβR-II by performing I125-labeled TGF-β (I125-TGF-β)-cross-linking at 0°C in Mv1Lu cells treated with ethanol. Mv1Lu cells were treated with 1.5% (v/v) DMSO (as a positive control) [Huang et al., 2015] and several concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.5, and 1%, v/v) of ethanol. After DMSO or ethanol treatment at 37°C for 1.5 h, treated cells were I125-TGF-β-cross-linked at 0°C and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography, as described previously [Chen et al., 2007, 2008]. DMSO has recently been shown to increase cell-surface expression of TβR-I and TβR-II without altering their cellular levels [Huang et al., 2015]. As shown in Figure 2A, DMSO treatment increased the cell-surface expression of both TβR-I and TβR-II by ~3-fold (lane 2 vs. lane 1), as described previously [Huang et al., 2015]. Ethanol at 0.5% and 1% (v/v) increased the cell-surface expression of both TβR-I and TβR-II by ~2–3-fold as compared to those in cells treated without ethanol (lanes 4 and 3 vs. lanes 1). Like DMSO [Huang et al., 2015], ethanol at 0.5%, 1%, and 2% did not affect the total cellular levels of TβR-I and TβR-II in these cells, as determined by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B). This suggests the presence of large intracellular pools of TβR-I and/or TβR-II in Mv1Lu cells. This also suggests that ethanol recruits TbβR-I and/or TβR-II from their intracellular pools to the cell surface. Intracellular pools (including recycling endosomes and/or exocytotic vesicles) of TβR-I and TβR-II have been found to exist in many cell types [Massagué and Kelly, 1986;Doré et al., 2001a; Asano et al., 2011].

Fig. 2.

Ethanol increases cell-surface expression of TβR-I and TβR-II (A) without altering their total cellular amounts (B) in Mv1Lu cells. (A) Cells were treated with DMSO (1.5%) and several concentrations (0%, 0.5%, and 1%, v/v) of ethanol (EtOH) at 37°C for 1.5 h. The cell-surface expression of TβR-I and TβR-II was determined by I125-TGF-β-cross-linking at 0°C as described [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. I125-TGF-β-cross-linked TβR-I and TβR-II (TβR-I* and TβR-II*) on the autoradiogram were quantified by a PhophoImager. Free I125-TGF-β, which migrated near the dye front, was cut off before autoradiography. A representative image of three experiments is shown. The relative amount of TβR-I* in cells treated with vehicle only (without DMSO and ethanol) (control cells) was quantified and taken as 1.0 (100%) (lane 1). TβR-II* in control cells (lane 1), and TβR-I* and TβR-II* in cells treated with DMSO (1.5%) (lane 2) and with 0.1%, 0.5%, and1% of EtOH (lanes 5, 4, and 3, respectively) were expressed as the amounts relative to that (1.0) of TβR-I* in cells treated with vehicle only (lane 1). The ratios (mean ± s.d.) of TβR-II*/TβR-I* in cells treated with vehicle only, DMSO, 0.1%, 0.5%, and 1% EtOH were estimated to be 0.6 ± 0.1 (n = 3), 0.6 ± 0.1 (n = 3), 0.6 ± 0.1 (n = 3), 0.8 ± 0.1* (n = 3), and 1.1 ± 0.1* (n = 3), respectively. *Significantly higher than that in cells treated with vehicle only (control): P <0.05. (B) Cells were treated with several concentrations (0%, 0.5%, 1%, and 2%, v/v) of ethanol (EtOH) at 37°C for 1.5 h. Western blot analyses of the cell lysates were performed using antibodies to TβR-I and TβR-II [Chen et al., 2007, 2008]. The relative amounts of TβR-I and TβR-II (with β-actin as an internal controls) were quantified by densitometry and were found to have no differences in cells treated with and without ethanol.

ETHANOL RECRUITS TβR-II AND TβR-I FROM INTRACELLULAR POOLS AND LIPID RAFTS/CAVEOLAE, RESPECTIVELY, TO NON-LIPID RAFT MICRODOMAINS

The I125-TGF-β-cross-linking (at 0°C) technique is not only used for detection of cell-surface TGF-β receptors but also used for determining the predominant microdomain (in lipid rafts/caveolae or non-lipid raft microdomains) localization of TβR-I and TβR-II hetero-oligomeric complexes [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. TβR-I and TβR-II are known to be present in both microdomains as hetero-oligomeric complexes [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. When the ratio of I125-TGF-β-cross-linked TβR-II (TβR-II*)/I125-TGF-β-cross-linked TβR-I (TβR-I*) is <1 (TβR-II* < TβR-I*), this indicates that the majority of TβR-I and TβR-II hetero-oligomeric complexes are localized in lipid rafts/caveolae [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2008]. If the ratio is >1, this indicates that majority of TGF-β receptor hetero-oligomeric complexes are localized in non-lipid raft microdomains where canonical signaling occurs [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. The more TGF-β receptor hetero-oligomeric complexes are localized in non-lipid raft microdomains, the more canonical TGF-β signaling is induced [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009].

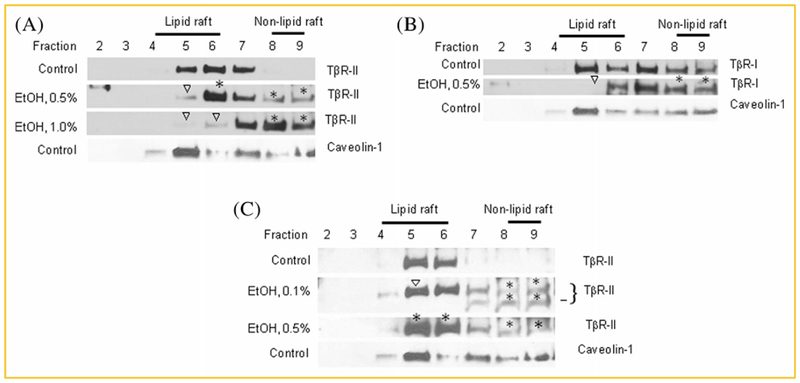

As shown in Figure 2A, 1.5% (v/v) DMSO treatment increased cell surface-expression of TβR-I and TβR-II in Mv1Lu cells by ~3-fold but did not alter the ratio of TβR-II*/TβR-I* as compared to those (0.6) in the cells treated with vehicle only (control) (lane 2 vs. lane 1), as described previously [Huang et al., 2015]. This is consistent with the notion that DMSO increases cell-surface expression of TβR-II by recruiting TβR-II from its intracellular pool to both lipid rafts/caveolae and non-lipid microdomains without significantly altering the ratio of TβR-II*/TβR-I*, indicating predominant localization of these TGF-β receptor hetero-oligomeric complexes in lipid raids/caveolae [Huang et al., 2015]. The ratios of TβR-II*/TβR-I* in cells treated with vehicle only (control), 0.1%, 0.5%, or 1% ethanol were estimated to be 0.6 ± 0.1 (n = 3), 0.6 ± 0.1 (n = 3), 0.8 ± 0.1 (n = 3), and 1.1 ± 0.1 (n = 3), respectively (lanes 1, 5, 4, and 3). It is important to note that ethanol (0.5% and 1%, v/v) increased the ratio of TβR-II*/TβR-I* from 0.6 (0% or0.1% ethanol) to 0.8 and 1.1, respectively. This suggests that ethanol not only increases the cell-surface expression of TβR-I and/or TβR-II but also recruits these receptors to cell-surface non-lipid raft microdomains in a concentration-dependent manner. Ethanol at 1% caused predominant localization of TβR-I and TβR-II in non-lipid raft microdomains because the TβR-II*/TβR-I* ratio is larger than 1 [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. To prove this, we determined the effect of ethanol treatment on microdomain localization of TβR-I and TβR-II in Mv1Lu cells treated with 0.5% or 1% (v/v) ethanol for 1.5h by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation followed by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3A, 0.5% or 1% (v/v) ethanol increased the total amount of TβR-II in plasma-membrane microdomains (lipid rafts/caveolae + non-lipid raft microdomains; fractions 5 and 6 + fractions 8 and 9) by ~2-fold as compared to those in cells treated with vehicle only (control) (Fig. 3A, EtOH 0.5% or 1.0% vs. control). The increased amount of TβR-II in the plasma membrane microdomains of ethanol-treated cells is likely derived from its intracellular pool. This is consistent with the ethanol-induced ~2–3-fold increase in cell-surface expression of TGF-β receptors, as determined by I125-TGF-β-cross-linking (Fig. 2A, lanes 4 and 3 vs. lanes 1). In addition to its effect on cell-surface expression (or plasma-membrane localization), ethanol also induced recruitment of TβR-II from plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft microdomains in a concentration-dependent manner. In these cells, ethanol at 0.5% and 1 % (v/v) displaced ~30% and nearly 100% of TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae, respectively, and facilitated translocation of TβR-II to non-lipid raft microdomains, (Fig. 3A, fractions 5 and 6 vs. fractions 8 and 9). Interestingly, treatment of cells with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol did not increase the total amount of TβR-I in these membrane microdomains as compared to those in cells treated with vehicle only (Fig. 3B, EtOH 0.5%: fractions 6, 8, and 9 vs. Control: fractions 5, 6, 8, and 9). However, 0.5% ethanol displaced ~70% TβR-I from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitated its translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains (Fig. 3B, EtOH 0.5%: fractions 5 and 6 vs. fractions 8 and 9). These results suggest that 0.5% and 1% ethanol are equally potent in inducing recruitment of TβR-II from its intracellular pool to the cell surface or plasma membrane microdomains (Fig. 3A, EtOH 0.5% and 1%). However, 1% ethanol appears to be more effective than 0.5% ethanol in displacing TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains (Fig. 3A, EtOH 1% vs. EtOH 0.5%). Since non-lipid raft microdomains are responsible for mediating canonical TGF-β signaling [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003], these results also suggest that ethanol enhances canonical TGF-β signaling by recruiting TβR-II from its intracellular pool to plasma-membrane micromodains and by displacing TβR-I and TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains in these cells. It is important to note that ethanol differs from DMSO in its ability to recruit TβR-I and TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft microdomains. This is because ethanol is capable of releasing cholesterol from lipid rafts/caveolae which results in destabilizing resident membrane proteins (including TGF-β receptors) there and facilitating their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains. In contrast, DMSO does not have this property and only induces recruitment of TβR-II [Huang et al., 2015] from its intracellular pool to both lipid rafts/caveolae and non-lipid raft microdomains. The recruitment of TβR-I (which presumably resides in lipid rafts/caveolae) to non-lipid raft microdomains by DMSO is possibly due to the presence of TβR-II (which is recruited from the intracellular pool alter DMSO treatment) in non-lipid raft microdomains, which recruit TβR-I from lipid rafts/caveolae by forming hetero-oligomeric complexes of TβR-I and TβR-II in non-lipid raft microdomains [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009].

Fig. 3.

Ethanol recruits TβR-II (A,C) and TβR-I (B) from lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft microdomain in Mv1Lu cells. Cells were treated with 0%, 0.5%, and/or 1.0% (v/v) ethanol at 37 °C for 2 h (A,B). In a separate experiment, cells were treated with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol or 0.1% of ethanol for 2 h and then an additional 0.1% (v/v) of ethanol (C). After a total incubation time of 5 h, the lipid raft/caveolae and non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TβR-I and TβR-II was determined by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation followed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis using antibodies to TβR-I and TβR-II (A–C). Fraction 1 (A–C), which did not exhibit the presence of the antigen, is not shown. Fractions 4, 5, and 6, and fractions 8 and 9 represent lipid raft/caveolae- and non-lipid raft microdomain-containing fractions respectively, as described [Chen et al., 2007, 2008]. Caveolin-1 is a marker for lipid raft/caveolae-containing fractions (fractions 4–6). Ethanol at 0.5% and 1% did not affect the distribution of caveolin-1 in the sucrose density gradient fractions. The presence of a small amount of caveolin-1 in fractions 7–9 was presumably due to the presence of mitochondria in these fractions. Caveolin-1 is known to be associated with mitochondria under the low confluent cell state. Fraction 10, which mainly contained cell debris, is not shown. The data are representative of a total of three independent analyses. Open arrowheads in A and B indicate the decreased amount of TβR-I or TβR-II in the fraction as compared with that of untreated control. The * in A–C indicates the increased amount of TβR-I or TβR-II in the fraction as compared with that of untreated control. The bar in C indicates a proteolytic product of TβR-II.

Pharmacological concentrations of ethanol are ≤50 mM (0.29%, v/v) [Dolganiuc et al., 2006; Dooley and ten Dijke, 2012]. Treatment of Mv1Lu cells with 0.1% (~17 mM) ethanol for 2 h did not significantly affect the total cellular amounts and microdomain localization of TβR-I and TβR-II as compared to those in cells treated without ethanol (data not shown). Ethanol is relatively stable under the experimental conditions. We reasoned that ethanol at 0.1% (v/v) in the medium may evaporate rapidly under the incubation conditions (37°C, 5% CO2, 2 h). We then treated Mv1Lu cells with 0.1% (v/v) ethanol at 37°C for 2 h and then added additional ethanol (0.1%, v/v) to the medium. After further incubation for 3 h, the cell lysates were subjected to analysis of the plasma-membrane microdomain localization of TβR-I and TβR-II by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation followed by Western blot analysis. In a separate experiment, Mv1Lu cells were directly treated with 0.5% (v/v) ethanol for 5 h and analyzed for plasma membrane microdomain localization by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation and Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 3C, addition of 0.1% (v/v) ethanol into the medium at two time points was more potent in recruiting TβR-II from lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft microdomains than 0.5% (v/v) ethanol added once in a total incubation time of 5h (20 ± 4% of TβR-II in lipid rafts/caveolae vs. 10 ± 4% of TβR-II in lipid rafts/caveolae). These results suggest that ethanol at 0.1–0.2 % (v/v), which is in the range of the pharmacological concentrations (≤0.29% or 50 mM), is capable of displacing TGF-β receptors from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating their translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains. Treatment of cells with 0.5% ethanol for 5h also increased the total amount of cell-surface (or plasma-membrane) TβR-II by ~2-fold as compared to that in cells treated without ethanol (Fig. 3C, EtOH 0.5%: fractions 5,6,8, and 9 vs. Control: fractions 5 and 6). The 0.5% ethanol (5 h incubation)-increased cell-surface or non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TβR-II is presumably derived from its intracellular pool. However, the recruitment of TβR-II to non-lipid raft microdomains by 0.5% (v/v) ethanol (5 h incubation) is less than that caused by 0.5% (v/v) ethanol (2 h incubation) (~10% of TβR-II in Fig. 3C vs. ~30% of TβR-II in Fig. 3A). These results suggest that the effect of ethanol on recruiting TGF-β receptors to non-lipid raft microdomains is reversible.

ETHANOL RECRUITS TβR-II FROM INTRACELLULAR VESICLES TO PLASMA-MEMBRANE LIPID RAFTS/CAVEOLAE AND NON-LIPID RAFT MICRODOMAINS

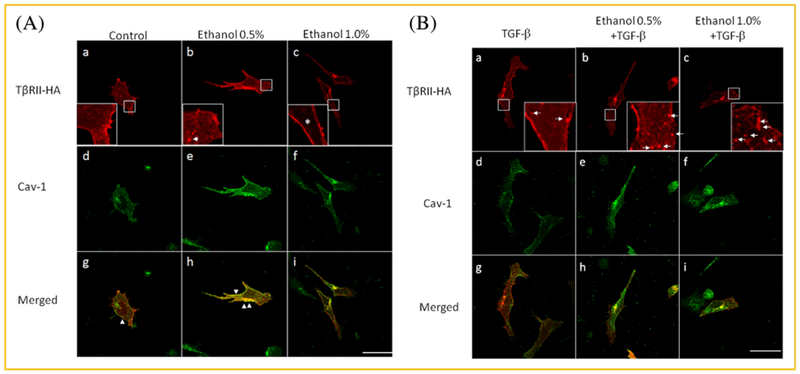

As shown above, ethanol recruits TβR-II but not TβR-I from its intracellular pool to plasma-membrane microdomains and also recruits TβR-I and TβR-II from plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft microdomains. To characterize the intracellular pool of TβR-II, we performed indirect immunofluorescence staining of Mv1Lu cells transiently expressing hemagglutinin (HA) epitope-tagged TβR-II (TβR-II-HA) plasmid [Tsukazaki et al., 1998] after treatment of these cells with ethanol (0,0.5% and 1%, v/v) for 1.5 h, using antibodies to HA and caveolin-1. Antibody to the HA epitope is highly reliable, specific and sensitive [Czech et al., 1993], and is suitable for identifying the intracellular TβR-II-HA in these cells. In contrast, immunostaining of endogenous TβR-II with commercially available antibodies to TβR-II usually yields a high non-specific background in the cytoplasm of Mv1Lu cells. For these reasons, we decided to characterize TβR-II-HA in Mv1Lu cells transiently transfected with TβR-II-HA plasmid using antibody to HA. As shown in Figure 4A, in cells treated with vehicle only (control), TβR-II-HA was found in the plasma membrane and cytoplasm (panel a). TβR-II-HA was present in the cytoplasm as a vesicle-like network (Fig. 4A, inset in panel a). Caveolin-1 was seen in the plasma membrane and cytoplasm (Fig. 4A, panel d). Caveolin-1 in the cytoplasm is presumably associated with mitochondria in the non-confluent growing state [Li et al., 2001; Rashid-Doubell et al., 2007].

Fig. 4.

Ethanol induces recruitment of TβR-II-HA from its intracellular pool to plasma membrane microdomains in TβR-II-HA-transiently-transfected Mv1Lu cells treated with vehicle only (A) and TGF-β (B). Mv1Lu cells transiently transfected with TβR-II-HA plasmid (from Addgene) were treated with 0%, 0.5%, and 1% ethanol in the presence of vehicle only (A) and 100pM TGF-β (B) at 37°C for 1.5 h. Cells were then subjected to indirect immunofluorescence staining using anti-HA (A and B, panels a–c) and anti–caveolin-1 (A and B, panels d–f). Merged staining is also shown (A and B, panels g–i). Insets indicate the intracellular pool of TβR-II-HA before and after ethanol treatment (A and B, panels a–c). The * indicates the absence of TβR-II-HA in the cytoplasm (the inset in panel c) The presence of caveolin-1 (Cav-1) staining was found in the plasma membrane, cytoplasm and Golgi apparatus (A and B, panels d–f). In the cytoplasm, caveolin-1 is known to be associated with mitochondria. This appears to be consistent with the presence of small amounts of caveolin-1 in fractions 7–9 in the fractions obtained from sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation of the cell lysates of Mv1Lu cells treated with vehicle only (Fig. 3A). Arrow indicates the localization of exocytotic vesicles which may target the plasma membrane for fusion (A, inset in panel b). Arrowheads indicate the co-localization (as indicated by yellow color) of TβR-II-HA and caveolin-1 at the plasma membrane (A, panels g and h). Arrows indicate the localization of endosomes (B, inset in panels a–c). Size bar represents 10 microns.

TβR-II-HA and caveolin-1 were co-localized at the plasma membrane in these cells (panel g). However, after treatment of these cells with 0.5% ethanol, both the plasma membrane localization of TβR-II-HA and co-localization of TβR-II-HA and caveolin-1 at the plasma membrane (Fig. 4A, panels b and h, respectively) increased as compared to those in cells treated without ethanol (control) (Fig. 4A, panels a and g). It is important to note that 0.5% ethanol induces formation of fused vesicles (inset in panel b). Furthermore, treatment of cells with 1% ethanol resulted in depletion of TβR-II-HA from the areas of the cytoplasm (inset in panel c vs. inset in panel a) and the disappearance of TβR-II-HA and caveolin-1 co-localization in the plasma membrane (panel i vs. panel h). These results suggest that the intracellular pool of TβR-II-HA is present in the cytoplasm as a vesicle-like network. These results also suggest that, like endogenous TβR-II (Fig. 3A), exogenous TβR-II-HA undergoes ethanol-induced recruitment from intracellular vesicles to plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae and non-lipid raft microdomains.

TREATMENT OF CELLS WITH TGF-β DOES NOT AFFECT THE INTRACELLULAR POOL OF TβR-II-HA AND ETHANOL-INDUCED RECRUITMENT OF TβR-II-HA FROM CYTOPLASMIC VESICLES TO PLASMA MEMBRANES

TGF-β-induced canonical signaling is often thought to occur in endosomes [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003]. However, our recent studies [Chen et al., 2009] reveal that it occurs at coated-pit stages during clathrin-dependent endocytosis of TGF-β-bound TβR-I-TβR-II hetero-oligomeric complexes. These are localized in plasma-membrane non-lipid raft microdomains. On the other hand, a population of cell-surface TβR-I-TβR-II hetero-oligomeric complexes are localized in lipid rafts/caveolae. After TGF-β binding, these hetero-oligomeric complexes undergo rapid internalization and degradation [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005]. To see the effect of TGF-β on the intracellular pool of TβR-II-HA, Mv1Lu cells were treated with 100 pM TGF-β in the presence of 0%, 0.5%, and 1% ethanol for 1.5 h. Indirect immunofluorescence staining of these treated cells was performed using antibodies to the HA epitope and caveolae-1. As shown in Figure 4B, TGF-β did not significantly affect the intracellular pool of TβR-II-HA in cells treated without ethanol (control) and with 0.5% ethanol (Fig. 4B, inset in panels a and b vs. Fig. 4A, inset in panels a and b) but increased TβR-II-HA-positive endosomes in the cytoplasm of these cells as compared to those in cells treated with vehicle only (control) (Fig. 4B, inset in panels a, b and c vs. Fig. 4A, inset in panels a, b and c). TGF-β did not affect ethanol (1%)-induced depletion of the intracellular pool of TβR-II-HA but greatly increased the number of TβR-II-HA-positive endosomes (Fig. 4B, inset in panel c vs. Fig. 4A, inset in panel c). This is due to the fact that 1% ethanol recruits TβR-II-HA from cytoplasmic vesicles to non-lipid raft microdomains where TGF-β receptors undergo clathrin-dependent endocytosis following TGF-β binding (Fig. 4B, inset in panel c). In addition, TGF-β induces rapid degradation of TβR-II-HA localized to lipid rafts/caveolae [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005]. This results in disappearance of co-localization of TβR-II-HA and caveolin-1 at the plasma membrane in cells treated with TGF-β in either the presence or absence of ethanol (Fig. 4B, panels g, h, and i). These results can be summarized in Table 1. They indicate that ethanol enhances TGF-β-induced endosomal localization of Tβ R-II-HA in a concentration-dependent manner. They are also consistent with the notion that ethanol enhances canonical TGF-β signaling by promoting non-lipid raft microdomain (coated-pit)-mediated endocytosis [Chen et al., 2009].

TABLE I.

Ethanol Induces Depletion of TβR-II-HA From Cytoplasmic Vesicles and Enhances TGF-β-Stimulated Endocytosis of Plasma-Membrane TβR-II-HA in Mv1Lu Cells Transiently Transfected With TβR-II-HA Plasmida

| −TGF-β |

+TGF-β |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TβR-II-HA localization | Ethanol 0% | 0.5% | 1% | Ethanol 0% | 0.5% | 1% |

| Cytoplasmb | +++ | +++c | ± | +++ | +++ | ± |

| Plasma membrane | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lipid rafts/caveolaed | + | +++ | − | − | − | − |

| Endosomese | − | − | − | + | ++ | +++ |

Mv1Lu cells transiently transfected with TβR-II-HA plasmid were treated with several concentrations (0%, 0.5%, or 1%) of ethanol in the presence of vehicle only (−TGF-β) or 100 pM TGF-β (+TGF-β) at 37°C for 1.5 h. Cells were fixed and stained with a mouse antibody against hemagglutinin (HA) epitope and a rabbit antibody against caveolin-1 and then with rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody.

TβR-II-HA evenly distributed in the cytoplasm as a vesicle-like network in cells treated without ethanol (0%) was taken as +++.

The network containing TβR-II-HA in the cytoplasm exhibited formation of exocytotic vesicles after 0.5% ethanol treatment. These vesicles would presumably be fused with the plasma membrane and present TβR-II-HA at the cell surface.

TβR-II-HA was co-localized with caveolin-1 at lipid rafts/caveolae (as marked by yellow) in the plasma membrane.

TGF-β treatment resulted in formation of endosomes. The density of TβR-II-HA-positive endosomes in cells treated with 1% ethanol was taken as +++.

DISCUSSION

In this communication, we show that ethanol enhances TGF-β-stimulated activity. This is mediated by recruiting TβR-II from its intracellular pool to plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae and non-lipid raft microdomains, as well as by recruiting TβR-I and TβR-II from plasma-membrane lipid rafts/caveolae to non-lipid raft mcrodomains. TβR-I and TβR-II hetero-oligomeric complexes localized in non-lipid raft microdomains are known to mediate canonical TGF-β signaling upon TGF-β (ligand) binding [Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Huang and Huang, 2005; Le Roy and Wrana, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. Ethanol has also been shown to increase cell-surface expression of membrane receptors without affecting their total cellular levels [Kumar et al., 2004]. These results suggest that ethanol increases cell-surface expression from intracellular pools of these membrane receptors, including TβR-II, by inducing fusion of endocytotic vesicles containing these receptors with plasma membranes. Ethanol is known to be a fusogenic substance which is capable of inducing vesicle-membrane fusion [Komatsu and Okada, 1995; Chanturiya et al., 1999; Mondal and Sarkar, 2011]. It is also capable of increasing membrane fluidity by depleting cholesterol from plasma membranes of target cells [Dolganiuc et al., 2006; Szabo et al., 2007]. This results in destabilizing or displacing membrane proteins associated with lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating translocation of these displaced proteins to non-lipid raft microdomains [Huang and Huang, 2005; Dolganiuc et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2007, 2008; Szabo et al., 2007]. The mechanisms by which ethanol increases cell-surface expression and non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TGF-β receptors appear to be different. This is supported by different optimal concentrations of ethanol required for these two activities: ≥0.5% versus ≤1% for cell surface expression and non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TGF-β receptors, respectively. The effect of ethanol-increased cell-surface expression of TβR-II is persistent and lasts longer (at least for 3 h) than that of ethanol-increased non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TβR-II.

We also show that the TβR-II exhibits a large intracellular pool which is ~2-3-fold of the cell-surface TβR-II. TGF-β stimulation at the cell-surface does not appear to affect the level of TβR-II in the cytoplasmic pool. The role of the TβR-II cytoplasmic pool in the homeostasis of cell-surface TβR-II is not clear. It is possible that the cytoplasmic TβR-II may serve as a reservoir to replace cell-surface TβR-II after its ligand-induced internalization and degradation. The molecular motif in TβR-II responsible for the presence of such a large intracellular pool in the cytoplasmic pool is unknown. However, TβR-II possesses a non-canonical di-isoleucine motif in the cytoplasm domain near the plasma membrane [Ehrlich et al., 2001]. This motif has been shown to be essential for clarthrin-mediated endocytosis of TβR-II [Doré et al., 2001b]. Interestingly, other membrane proteins, such as potassium channel Kir2.3 [Mason et al., 2008], mammary gland rat8 [Zucchi et al., 2004], sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (Ntcp) [Stross et al., 2013], Na+/H+ Exchanger NHE5 [Szaszi et al., 2002], and K+channel 1 (TWIK1) [Feliciangeli et al., 2010], cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) [Varga et al., 2004] and gamma-aminobutyric acid A (GABAA) receptor [Kumar et al., 2004], have been shown to have a large intracellular pool and also possess diisoleucine motifs. Disruption of the di-isoleucine motif in Kir2.3 is known to decrease interaction of the channel protein with AP-2 [Mason et al., 2008]. Replacement of the di-isoleucine motif with a di-leucine signal actually results in blocking of Kir2.3 endocytosis [Mason et al., 2008]. These results support the important role of diisoleucine in the formation of the large intracellular pool in the cytoplasm. The TGF-β receptors (TβR-I and TβR-II) have been shown to possess large intracellular (cytoplasmic) pools in different cell types. We hypothesize that TβR-I and TβR-II are present in different vesicles in the cytoplasm. TβR-I possesses a di-leucine motif for internalization from the cell surface [Shapira et al., 2012].

The TGF-β enhancer activity of ethanol thus contributes to both its beneficial and harmful effects on human health. For example, at low doses which produce moderate but reversible TGF-β enhancer activity, ethanol exhibits beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system [Albert et al., 2003; Levitan et al., 2005]. It is well known that moderate drinking of alcohol decreases the risk of ASCVD [Albert et al., 2003; Levitan et al., 2005]. The TGF-β enhancer activity at low doses of ethanol appears to be responsible, at least in part, for this beneficial effect [Chen et al., 2009]. This is because circulating TGF-β protects against ASCVD [Grainger and Metcalfe, 1995]. In contrast, excessive ethanol use or alcohol abuse, which may produce potent and lasting TGF-β enhancer activity (via increasing cell-surface expression and non-lipid raft microdomain localization of TβR-II and TβR-I), leads to ALD. After acute liver injury induced by ethanol or other agents, TGF-β produced at the injury site promotes collagen synthesis in the activated hepatic stellate cells via Smad signaling pathways which are enhanced by ethanol [Yoshida and Matsuzaki, 2012]. TGF-β is also a central regulator in chronic liver disease [Bataller and Brenner, 2005; Breitkopf et al., 2005; Dooley and ten Dijke, 2012]. TGF/Smad signaling is involved in all stages of disease progression from initial liver injury through inflammation and fibrosis to cirrhosis. Active TGF-β produced after liver damage and TGF^/Smad signaling facilitate hepatocyte destruction and mediate activation of hepatic stellate cells and fibroblasts, resulting in myofibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix deposition. TGF/Smad signaling enhancer activity of ethanol is thus likely involved in the initiation and progression of chronic ALD caused by excessive ethanol use. The ethanol-enhanced Smad signalling pathway of TGF-β, a major profibrogenic cytokine, should be an ideal target for developing therapeutic agents to treat ALD progression.

Excessive alcohol use can also lead to the development of a variety of health problems other than chronic liver disease. TGF-β does not appear to be critically involved in the pathologies of neurological disorders [Fernandez-Lizarbe et al., 2013; Marin et al., 2013; Pascual-Lucas et al., 2014], malnutrition [Wani et al., 2012], developmental neurotoxicity [Littner et al., 2013], immune suppression [Ghare et al., 2011], or impaired Th1-mediated cellular immune responses [Ishikawa et al., 2011]. The mechanisms by which ethanol causes these effects are becoming clearer. Increasing evidence indicates that ethanol-induced displacement from lipid rafts/caveolae of many membrane proteins, which utilize lipid rafts/caveolae as functioning or signaling platforms, appears to play an important role in creating health problems caused by ethanol [Ghare et al., 2011; Ishikawa et al., 2011; Wani et al., 2012; Fernandez-Lizarbe et al., 2013; Littner et al., 2013; Pascual-Lucas et al., 2014]. In this communication, we demonstrate that ethanol at the apparent concentration of 1% (v/v), the exact concentration of which may be much lower due to potential evaporation during in vitro incubation (particularly for longer-time incubation), almost completely displace the TGF-β receptors from lipid rafts/caveolae. This suggests that ethanol is likely to exert similar effects on other membrane proteins (e.g., dopamine and serotonin receptors) which reside in lipid rafts/caveolae and utilize lipid rafts/caveolae as functioning platforms [Allen et al., 2007]. If it does occur, it could cause immediate dramatic or catastrophic effects on nerve function. In addition, ethanol stimulates the GABAA receptor by displacing it from lipid rafts/caveolae and facilitating its translocation to non-lipid raft microdomains where the GABAA receptor becomes activated. This promotes central nervous system depression. Under repeated heavy consumption of ethanol, the GABAA receptor is desensitized and reduced in number, leading to tolerance and physical dependence [Barnes, 1996].

Ethanol has been used as an antiseptic agent extensively in hospitals and public places for topical dermal applications. The biocide action of ethanol has been well studied [McDonnell and Russell, 1999]. The ability of ethanol to destabilize lipid rafts/caveolae demonstrated here may provide new insights into the disinfectant action of ethanol. Since lipid rafts/caveolae have been shown to serve as cell-entry portals of pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, parasites, and prions [Rosenberger et al., 2000], ethanol application to skin may confer resistance to infection by these pathogens. It is important to note that the effect of ethanol on lipid rafts/caveolae is reversible. Thus, the disinfectant action of ethanol is temporally limited.

Ethanol-induced alteration of the structure and function of lipid rafts/caveolae may provide a target for development of effective agents to prevent or treat ethanol-caused lipid raft/caveolae-related pathologies. For example, cholesterol analogs and/or docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) supplementation maybe useful for prevention and treatment of alcohol-related diseases and disorders. Cholesterol has been shown to antagonize the cellular effects of cholesterol-lowering agents and cholesterol-depleting agents which alter the formation and function of lipid rafts/caveolae in cells [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2008]. Cholesterol has also been shown to decrease mortality from alcohol-related diseases in humans [Fagot-Campagna et al., 1997; Roongpisuthipong et al., 2001]. DHA has been recently shown to protect lipid rafts/caveolae against ethanol toxicity in primary rat hepatocytes [Aliche-Djoudi et al., 2013]. These results suggest that consumption of ethanol with foods containing compounds, which stabilize lipid rafts/caveolae and confer resistance to ethanol-induced toxicity, may attenuate the toxicity caused by ethanol at large doses. Human clinical trials are warranted.

MATERIALS

Na[125I] (17 Ci/mg) was obtained from ICN Biochemicals (Irvine, CA). DMEM, high molecular mass protein standards (myosin, 205 kDa; β-galactosidase, 116 kDa; phosphorylase, 97 kDa; bovine serum albumin, 66 kDa), chloramine-T, Disuccinimidyl suberate (DSS) and other biochemical reagents were obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Recombinant human TGF-β1 was obtained from PreproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies to caveolin-1, P-Smad2, Smad2, P-Erk1/2, Erk1/2, β-actin, TβR-I, and TR-II were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The luciferase assay system was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI).

LUCIFERASE ACTIVITY ASSAY

MLE cells-Clone 32 are Mv1Lu cells stably expressing the luciferase reporter gene driven by the PAI-1 promoter [Chen et al., 2007, 2009]. MLE cells were grown to near-confluence on 12-well dishes and then treated with 50 or 100 pM of TGF-β in the presence of ethanol at the concentrations as indicated at 37°C for 5h. Treated cells were then lysed in 100 μl of lysis buffer (Promega). The cell lysates (~20 μg protein) were then assayed using the luciferase kit from Promega.

QUANTITATIVE WESTERN BLOT ANALYSIS

Mv1Lu cells grown to near confluence on 12-well culture dishes were treated with 50 or 100 pM TGF-β in the presence of ethanol at the concentration as indicated in serum-free DMEM (0.5 ml/well) at 37°C for 45 min [Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009]. Treated cells were lysed by SDS sample buffer. Cell lysates with equal amounts of protein (200 μg) were analyzed by 7.5% SDS–PAGE followed by Western blotting using anti-Smad2, anti-P-Smad2 antibodies, anti-P-Erk1/2, and anti-Erk1/2 antibodies. The relative levels of Smad2/P-Smad2 and Erk1/2/P-Erk1/2 were determined by densitometry.

CELL-SURFACE 125I-LABELED TGF-β-CROSS-LINKING

Cell-surface 125I-labeled TGF-β (125I-TGF-β)-cross-linking was performed at 0°C using the cross-linking agent DSS according the published procedures [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008, 2009], 125I-TGF-β-cross-linked cell lysates were analyzed by 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed by autoradiography or quantification using a PhosphoImager. Mv1Lu cells grown to confluence on 6-well culture dishes were treated with several concentrations of ethanol at 37°C. After 1.5 h, treated cells were washed with cold binding buffer and incubated with 100 pM 125I-TGF-β in the presence or absence of 100-fold excess of unlabeled TGF-β in binding buffer containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at 0°C for 2.5 h. 125I-TGF-β-bound cells were then washed with cold binding buffer in the absence of bovine serum albumin and then incubated with 30 μM DSS at 0°C for 15 min. 125I-TGF-β-cross-linked cell lysates were analyzed by 7.5% SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and autoradiography.

SEPARATION OF LIPID RAFT AND NON-LIPID RAFT MICRODOMAINS OF PLASMA MEMBRANES BY SUCROSE DENSITY GRADIENT ULTRACENTRIFUGATION

Mv1Lu were grown to near confluence in 100 mm dishes (5–10 × 106 cells per dish). Cells were incubated with several concentrations of ethanol (0%, 0.5%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, and 2.5%, v/v) at 37°C for 1.5 h. After two washes with ice cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), cells were scraped into 0.85 ml of 500 mM sodium carbonate, pH 11.0. Homogenization was carried out with 10 strokes of a tightfitting Dounce homogenizer followed by three 20 s bursts of an ultrasonic disintegrator (Soniprep 150; Fisher Scientific) to disrupt cell membranes, as described previously [Chen et al., 2007, 2008]. The homogenates were adjusted to 45% sucrose by addition of 0.85 ml of 90% sucrose in 25 mM 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid, pH 6.5, 0.15 M NaCl (MBS), and placed at the bottom of an ultracentrifuge tube. A discontinuous sucrose gradient was generated by overlaying 1.7 ml of 35% sucrose and 1.7 ml of 5% sucrose in MBS on the top of the 45% sucrose solution. It was then centrifuged at 200,000g for 16–20 h in an SW55 TI rotor. Ten 0.5 ml fractions were collected from the top of the tube, and a portion of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis using antibodies to TβR-I and TβR-II. The relative amounts of TβR-I and TβR-II on the blot were quantified by densitometry. Caveolin-1 was used as an internal loading control for the quantitative analysis of both TGF-β receptors in the fractions of sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation. Fractions 4, 5, and 6, and fractions 8 and 9 contained caveolin-1 and transferrin receptor-1, respectively [Huang and Huang, 2005; Chen et al., 2007, 2008].

INDIRECT IMMUNOFLUORESCENCE STAINING OF TβR-II-HA AND CAVELIN-1 IN Mv1Lu CELLS TRANSIENTLY TRANSFECTED WITH TβR-II-HA PLASMID

Mv1Lu cells were transiently transfected with TβR-Π-HA plasmid [González-Reimers et al., 2014] and grown to 50% confluence on coverslips overnight. Transfected cells were then pretreated with 0%, 0.5%, and 1.0% (v/v) ethanol at 37°C for 1.5 h and stimulated with and without 100 pM TGF-β for 30min. After TGF-β stimulation, cells were fixed in methanol at −20°C for 15 min, washed with PBS and treated with 0.2% gelatin in PBS for 1 h. Fixed cells were then incubated overnight with a mouse antibody against hemagglutinin (HA) protein (F-7; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and rabbit antibody against caveolin-1 (N-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at 1:100 dilution at 4°C in a humidified chamber. After extensive washing, cells were incubated with rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibody and FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody at a 1:50 dilution for 1 h. Images were viewed using a Leica TCS SP confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems Ltd., Heidelberg, Germany). The measurements of co-localization rate were analyzed using a Leica Application Suite (LAS). Approximately 20–30 cells were viewed for the confocal imaging. The number of replications was three.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed by comparing ethanol-treated cells versus untreated (control) cells using unpaired and two-tailed Student’s t-tests. The P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lai-Ping Yan and Ying Fei for technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grants HL 095261 and AR 052578 to Auxagen and AAO19233 to St. Louis University (J.S.H.). This work was also supported by the University President’s Research Fund, Saint Louis University (J.S.H.) and the NSYSU-KMU Joint Research Project (NSYSUKMU104-I004), National Sun Yat-sen University (C.L.C).

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant numbers: HL 095261, AR 052578; Grant sponsor: University President’s Research Fund, Saint Louis University (J.S.H.); Grant sponsor: NSYSU-KMU Joint Research Project (NSYSUKMU104-I004), National Sun Yat-sen University (C.L.C).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest:

The authors declare that they have one conflict of interest. Jun San Huang and Shuan Shian Huang had an equity position in Auxagen Inc. during the time the research was carried out.

REFERENCES

- Abe M, Harpel JG, Metz CN, Nunes I, Loskutoff DJ, Rifkin DB. 1994. An assay for transforming growth factor-β using cells transfected with a plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promoter-luciferase construct. Anal Biochem 216:276–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM. 2003. Alcohol consumption and plasma concentration of C-reactive protein. Circulation 107:443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliche-Djoudi F, Podechard N, Collin A, Chevanne M, Provost E, Poul M, Le Hegarat L, Catheline D, Legrand P, Dimanche-Boitrel MT, Lagadic-Gossmann D. 2013. A role for lipid rafts in the protection afforded by docosahexaenoic acid against ethanol toxicity in primary rat hepatocytes. Food Chem Toxicol 60:286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JA, Halverson-Tamboli RA, Rasenick MM. 2007. Lipid raft microdomains and neurotransmitter signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:128–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apte MV, Zima T, Dooley S, Siegmund SV, Pandol SJ, Singer MV. 2005. Signal transduction in alcohol-related diseases. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:1299–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asano Y, Ihn H, Jinnin M, Tamaki K, Sato S. 2011. Altered dynamics of transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) receptors in scleroderma fibroblasts. Ann Rheum Dis 70:384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assaife-Lopes N, Sousa VC, Pereira DB, Ribeiro JA, Chao MV, Sebastiao AM. 2010. Activation of adenosine A2A receptors induces TrkB translocation and increases BDNF-mediated phospho-TrkB localization in lipid rafts: Implications for neuromodulation. J Neurosci 30:8468–8480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Barnes EM Jr., 1996. Use-dependent regulation of GABAA receptors. Int Rev Neurobiol 39:53–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataller R, Brenner DA. 2005. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 115:209–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitkopf K, Haas S, Wiercinska E, Singer MV, Dooley S 2005. Anti-TGF-β strategies for the treatment of chronic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29:121S–131S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanturiya A, Leikina E, Zimmerberg J, Chernomordik LV. 1999. Short-chain alcohols promote an early stage of membrane hemifusion. Biophys J 77:2035–2045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Liu IH, Fliesler SJ, Han X, Huang SS, Huang JS. 2007. Cholesterol suppresses TGF-β responsiveness: Implications in atherogenesis. J Cell Sci 120:3509–35621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Huang SS, Huang JS. 2008. Cholesterol modulates cellular TGF-β responsiveness by altering TGF-β binding to TGF-β receptors. J Cell Physiol 215:223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Hou WH, Liu IH, Huang SS, Huang JS. 2009. Inhibitors of clathrin-dependent endocytosis inhibitors enhance TGF-β signaling and responses. J Cell Sci 122:1863–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrao G, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, La Vecchia C. 2004. A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of 15 diseases. Prev Med 38:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crews FT, Bechara R, Brown LA, Guidot DM, Mandrekar P, Oak S, Qin L, Szabo G, Wheeler M, Zou J 2006. Cytokines and alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30:720–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowley JJ, Treistman SN, Dopico AM. 2003. Cholesterol antagonizes ethanol potentiation of human brain BKCa channels reconstituted into phospholipid bilayers. Mol Pharmacol 64:365–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy LK, Winick-Ng W, Rylett RJ. 2014. Regulation of the high-affinity choline transporter activity and trafficking by its association with cholesterol-rich lipid rafts. J Neurochem 128:725–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech MP, Chawla A, Woon CW, Buxton J, Armoni M, Tang W, Joly M, Corvera S. 1993. Exofacial epitope-tagged glucose transporter chimeras reveal COOH-terminal sequences governing cellular localization. J Cell Biol 123:127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. 2003. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-β receptor signaling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol 5:410–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolganiuc A, Bakis G, Kodys K, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. 2006. Acute ethanol treatment modulates Toll-like receptor-4 association with lipid rafts. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30:76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley S, ten Dijke P. 2012. TGF-β in progression of liver disease. Cell Tissue Res 347:245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré JJ Jr., Yao D, Edens M, Garamszegi N, Sholl L, Leof EB. 2001. Mechanisms of transforming growth factor-β receptor endocytosis and intracellular sorting differ between fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 12:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré JJ Jr., Yao D, Edens M, Garamszegi N, Sholl EL, Leof EB. 2001. Mechanisms of transforming growth factor-β receptor endocytosis and intracellular sorting differ between fibroblasts and epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell 12:675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich M, Shmuely A, Henis YI. 2001. A single internalization signal from the di-leucine family is critical for constitutive endocytosis of the type II TGF-β receptor. J Cell Sci 114:1777–1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot-Campagna A, Hanson RL, Narayan KM, Sievers ML, Pettitt DJ, Nelson RG, Knowler WC. 1997. Serum cholesterol and mortality rates in a Native American population with low cholesterol concentrations: A U-shaped association. Circulation 96:1408–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciangeli S, Tardy MP, Sandoz G, Chatelain FC, Warth R, Barhanin J, Bendahhou S, Lesage F. 2010. Potassium channel silencing by constitutive endocytosis and intracellular sequestration. J Biol Chem 285:4798–4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lizarbe S, Montesinos J, Guerri C. 2013. Ethanol induces TLR4/TLR2 association, triggering an inflammatory response in microglial cells. J Neurochem 126:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghare S, Patil M, Hote P, Suttles J, McClain C, Barve S, Joshi-Barve S. 2011. Ethanol inhibits lipid raft-mediated TCR signaling and IL-2 expression: Potential mechanism of alcohol-induced immune suppression. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 35:1435–4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiselli G, Chen J, Kaou M, Hallak H, Rubin R. 2003. Ethanol inhibits fibroblast growth factor-induced proliferation of aortic smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23:1808–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Reimers E, Santolaria-Fernández F, Martín-González MC, Fernández-Rodríguez CM, Quintero-Platt G. 2014. Alcoholism: A systemic proinflammatory condition. World J Gastroenterol 20:14660–14671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DJ, Metcalfe JC. 1995. A pivotal role for TGF-β in atherogenesis? Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc 70:571–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiney JK, Dearth RK, Srivastava V, Rettori V, Dees WL. 2003. Actions of ethanol on epidermal growth factor receptor activated luteinizing hormone secretion. J Stud Alcohol 64:809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MV, Dale CE, et al. 2014. InterAct Consortium. 2014 Association between alcohol and cardiovascular disease: Mendelian randomisation analysis based on individual participant data. BMJ 349:g4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Huang JS. 2005. TGF-β control of cell proliferation (Review). J Cell Biochem 96:447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Ling TY, Tseng WF, Huang YH, Huang JS. 2003. Cellular growth inhibition by IGFBP-3 and TGF-β1 requires LRP-1. FASEB J 17:2068–2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SS, Chen CL, Huang FW, Hou WH, Huang JS. 2015. DMSO enhances TGF-β activity by recruiting the type II TGF-β receptor from intracellular vesicles to the plasma membrane. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa F, Kuwabara T, Tanaka Y, Okada Y, Imai T, Momose Y, Kakiuchi T, Kondo M. 2011. Mechanism of alcohol consumption-mediated Th2-polarized immune response. Nihon Arukoru Yakubutsu Igakkai Zasshi 46:319–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller P, Simons K. 1998. Cholesterol is required for surface transport of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Cell Biol 140:1357–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Okada S. 1995. Ethanol-induced aggregation and fusion of small phosphatidylcholine liposome: Participation of interdigitated membrane formation in their processes. Biochim Biophys Acta 1235:270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Fleming RL, Morrow AL. 2004. Ethanol regulation of gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptors: Genomic and nongenomic mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther 101:211–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roy C, Wrana JL. 2005. Clathrin- and non-clathrin-mediated endocytic regulation of cell signaling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6:112–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitan EB, Ridker PM, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Buring JE, Cook NR, Liu S. 2005. Association between consumption of beer, wine, and liquor and plasma concentration of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein in women aged 39 to 89 years. Am J Cardiol 96:83–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WP, Liu P, Pilcher BK, Anderson RG. 2001. Cell-specific targeting of caveolin-1 to caveolae, secretory vesicles, cytoplasm or mitochondria. J Cell Sci 114:1397–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littner Y, Tang N, He M, Bearer CF. 2013. L1 cell adhesion molecule signaling is inhibited by ethanol in vivo. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 37:383–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Miller MW. 1999. Platelet-derived growth factor-mediated signal transduction underlying astrocyte proliferation: Site of ethanol action. J Neurosci 19:10014–10025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin R, Rojo JA, Fabelo N, Fernandez CE, Diaz M. 2013. Lipid raft disarrangement as a result of neuropathological progresses: A novel strategy for early diagnosis? Neuroscience 245:26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason AK, Jacobs BE, Welling PA. 2008. AP-2-dependent internalization of potassium channel Kir2.3 is driven by a novel di-hydrophobic signal. J Biol Chem 283:5973–5984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massagué J, Kelly B. 1986. Internalization of transforming growth factor-β and its receptor in BALB/c 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol 128:216–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonnell G, Russell AD. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: Activity, action, and resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:147–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy Mondal, Sarkar M 2011. Membrane fusion induced by small molecules and ions. J Lipids 2011:528784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen VA, Le T, Tong M, Silbermann E, Gundogan F, de la Monte SM 2012. Impaired insulin/IGF signaling in experimental alcohol-related myopathy. Nutrients 4:1058–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothdurfter C, Tanasic S, Di Benedetto B, Uhr M, Wagner EM, Gilling KE, Parsons CG, Rein T, Holsboer F, Rupprecht R, Rammes G. 2013. Lipid raft integrity affects GABA receptor, but not NMDA receptor modulation by psychopharmacological compounds. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 1361–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Lucas M, Fernandez-Lizarbe S, Montesinos J, Guerri C. 2014. LPS or ethanol triggers clathrin- and lipid raft/caveolae-dependent endocytosis of TLR4 in cortical astrocytes. J Neurochem 129:448–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peoples RW, Li C, Weight FF. 1996. Lipid vs protein theories of alcohol action in the nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 36:185–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radek KA, Kovacs EJ, Gallo RL, DiPietro LA. 2008. Acute ethanol exposure disrupts VEGF receptor cell signaling in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 295:H174–H184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid-Doubell F, Tannetta D, Redman CWG, Sargent IL, Boyd CAR, Linton EA. 2007. Caveolin-1 and lipid rafts in confluent BeWo trophoblasts: Evidence for rock-1 association with caveolin-1. Placenta 28:139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Gmel G, Sepos CT, Trevisan M. 2003. Alcohol-related morbidity and mortality. Alcohol Res Health 27:39–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roongpisuthipong C, Sobhonslidsuk A, Nantiruj K, Songchitsomboon S. 2001. Nutritional assessment in various stages of liver cirrhosis. Nutrition 17:761–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberger CM, Brumell JH, Finlay BB. 2000. Microbial pathogenesis: Lipid rafts as pathogen portals. Curr Biol 10:R823–R825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapira KE, Gross A, Ehrlich M, Henis YI. 2012. Coated pit-mediated endocytosis of the type I transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) receptor depends on a di-leucine family signal and is not required for signaling. J Biol Chem 287:26876–26889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegmund SV, Dooley S, Brenner DA. 2005. Molecular mechanisms of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Dig Dis 23:264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stross C, Kluge S, Weissenberger K, Winands E, Häussinger D,Kubitz R 2013. A dileucine motif is involved in plasma membrane expression and endocytosis of rat sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (Ntcp). Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 305:G722–G730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo G, Dolganiuc A, Dai Q, Pruett SB. 2007. TLR4, ethanol, and lipid rafts: A new mechanism of ethanol action with implications for other receptor-mediated effects. J Immunol 178:1243–1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szaszi K, Paulsen A, Szabo EZ, Numata M, Grinstein S, Orlowski J. 2002. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis and recycling of the neuron-specific Na+/H+ exchanger NHE5 isoform. Regulation by phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase and the actin cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem 277:42623–42632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukazaki T, Chiang TA, Davison AF, Attisano L, Wrana JL. 1998. SARA, a FYVE domain protein that recruits Smad2 to the TGF-β receptor. Cell 95:779–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga K, Jurkuvenaite A, Wakefield J, Hong JS, Guimbellot JS, Venglarik CJ, Niraj A, Mazur M, Sorscher EJ, Collawn JF, Bebök Z 2004. Efficient intracellular processing of the endogenous cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in epithelial cell lines. J Biol Chem 279:22578–22584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani NA, Hamid A, Khanduja KL, Kaur J. 2012. Folate malabsorption is associated with down-regulation of folate transporter expression and function at colon basolateral membrane in rats. Br J Nutr 107:800–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Roh YS, Song J, Zhang B, Liu C, Loomba R, Seki E. 2014. Transforming growth factor β signaling in hepatocytes participates in steatohepatitis through regulation of cell death and lipid metabolism in mice. Hepatology 59:483–495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Matsuzaki K. 2012. Differential regulation of TGF-β/Smad signaling in hepatic stellate cells between acute and chronic liver injuries. Front Physiol 3:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucchi I, Prinetti A, Scotti M, Valsecchi V, Valaperta R, Mento E, Reinbold R, Vezzoni P, Sonnino S, Albertini A, Dulbecco R. 2004. Association of rat8 with Fyn protein kinase via lipid rafts is required for rat mammary cell differentiation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:1880–1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]