Abstract

Purpose:

Visual scene displays (VSDs) and just-in-time programming support are augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) technology features with theoretical benefits for beginning communicators of all ages. The goal of the current study was to evaluate the effects of a communication application (app) on mobile technology that supported the just-in-time programming of VSDs on the communication of preadolescents and adolescents who were beginning communicators.

Method:

A single-subject multiple-baseline across participant design was employed to evaluate the effect of the AAC app with VSDs programmed just-in-time by the researcher on the communication turns expressed by five preadolescents and adolescents (9–18 years old) who were beginning communicators.

Result:

All five participants demonstrated marked increases in the frequency of their communication turns after the onset intervention.

Conclusion:

Just-in-time programming support and VSDs are two features that may positively impact communication for beginning communicators in preadolescence and adolescence. Apps with these features allow partners to quickly and easily capture photos of meaningful and motivating events and provide them immediately as VSDs with relevant vocabulary to support communication in response to beginning communicators’ interests.

Keywords: augmentative and alternative communication, adolescents, visual scene displays, mobile technology, just-in-time supports

Introduction

Beginning communicators express themselves using modalities indicative of the early stages of language development such as gestures, facial expressions, and vocalisations (Romski, Sevcik, Hyatt, & Cheslock, 2002). Their use of symbolic communication is imminent, emerging, or new. Although by preadolescence many individuals use symbolic communication with complexity and ease, some individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD) and significant speech and language impairments enter and leave this life period without having yet developed such mastery over symbolic communication. This discrepancy is due to a variety of interplaying factors that are both intrinsic (e.g. working memory limitations) and extrinsic (e.g. limited access to expressive means) to the individuals themselves (Reichle, Beukelman, & Light 2002; Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013).

Therefore, beginning communicators often rely heavily on presymbolic forms of communication (e.g. idiosyncratic gestures, vocalisations). Beginning communicators who have begun to express themselves using symbols (i.e. words) in addition to these presymbolic forms express a limited number of words with limited frequency, and their role in interactions is limited (Reichle et al., 2002). They also possess few strategies for engaging partners. Preadolescent and adolescent beginning communicators are severely restricted in participation at school, at home, and in the community (Reichle et al., 2002).

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is one intervention option beneficial to individuals with significant speech and language impairments, including beginning communicators (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2013; Reichle et al., 2002). Benefits of AAC for preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators include: increases in frequency of communication (e.g. Banda, Copple, Koul, Sancibrian, & Bogschutz, 2010), increases in requesting (e.g. Ganz, Sigafoos, Simpson, & Cook, 2008), reductions in challenging behaviour (Mirenda, 1997), increases in social interaction participation (e.g. Trottier, Kamp, & Mirenda, 2011), and increases in classroom participation (e.g. Cafiero, 2001).

Although AAC intervention clearly benefits adolescents who are beginning communicators, outcomes relative to frequency of communication and expressive vocabulary seem to represent a narrow increase. Any increase is an important one, but beginning communicators often require large increases in communication to reach equal participation status in interactions (Reichle et al., 2002).

Although many factors are likely at play (e.g. funding, social perceptions), one important and relatively-malleable factor accounting for limitations in outcomes of AAC intervention for preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators to date may be restrictions in the AAC systems available to and utilised with these individuals in intervention. For example, many interventionists have held the belief that high-tech AAC is too sophisticated for beginning communicators to use (Romski et al., 2002). This belief is likely rooted in misunderstanding and restrictively-low expectations about the potential for preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators to become more effective language users. However, the demands associated with some high-tech AAC options rendering their use challenging (Light et al., 2004) may also play a role in this belief.

Thankfully, technology continues to develop and become increasingly more accessible. These advances have the potential to even further enhance the communicative power intervention utilising high-tech AAC can bring to the lives of beginning communicators. Two promising AAC innovations for preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators, discussed in more detail below, are visual scene displays (VSDs) and just-in-time (JIT) programming.

Innovations to optimise AAC for beginning communicators

Visual scene displays.

Visual scene displays are one representation option that may promote high-tech AAC accessibility (Light et al., 2004; Thistle & Wilkinson, 2013). VSDs are an alternative to traditional grid layouts in which individual, decontextualised icons are organised on a page. In contrast to the traditional grid, VSDs are photographs of meaningful events in which concepts are embedded. For example, a photograph from a school dance could be utilised as a visual scene display for a person who uses AAC. The faces of friends in the picture could be programmed to output their names (e.g. ‘Judea’). The school banner on the top of the photo could be programmed to output an expression of school pride (e.g. ‘Go Wolfpack!’). In this way, the concepts are grounded within, and can be retrieved from, a familiar context. These photographs may offer the additional benefit of being more transparent than other representation options frequently used with preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators such as colour line drawings, miniature objects, and parts of objects (Mirenda & Locke, 1989). Due to the high transparency of photographs and the context-richness of scenes, photo VSDs appear to be a promising layout option for beginning communicators, including adolescents (Light & Drager, 2007).

Just-in-time programming.

‘Just-in-time’ is a concept of efficiency transcending the field of AAC (Schlosser, Shane, Allen, Abramson, Laubscher, & Dimery, 2015). Within the context of AAC, however, ‘just-in-time’ refers to access to vocabulary and supports as they are needed in the moment (Schlosser et al., 2015). This provision of vocabulary in the moment is made possible through relatively recent technology such as mobile technology with integrative features (Schlosser et al., 2015). For instance, the onboard camera of a tablet could be used to take a photo of an event quickly to add as a VSD. Concepts can then be programmed as hotspots quickly via software with minimal programming steps and controls with low motor (e.g. larger buttons) and cognitive (e.g. transparent icons) demands (Holyfield, Drager, Light, & Caron, 2017). In keeping with the example above, the photo of the school dance could be captured and programmed with a hotspot by a peer and used by the adolescent beginning communicator to share with friends during said school dance.

Some beginning communicators rely on the context of the immediate interaction to scaffold their communication and expression. Therefore, they often express themselves using concepts pulled from that context. Programming concepts into AAC devices just-in-time allows beginning communicators to do just this; concepts can be programmed for beginning communicators to express within the same interaction their interest in those concepts derived. Using the immediate context as representation of AAC concepts may reduce the demands involved in associating a concept represented in aided AAC with its real-world referent – a difficult and important association for beginning communicators’ building of language (Smith & Grove, 2003).

Additionally, VSDs can be time-consuming to create and program with vocabulary (Caron, Light, & Drager, 2016). Applications (apps) supporting just-in-time programming significantly decrease the time required to program VSDs (Caron et al., 2016), making their provision to preadolescents/adolescents who are beginning communicators (and all people who may benefit from them) more feasible.

Despite the theorised benefits of the JIT programming of VSDs for people who are beginning communicators, empirical data are currently limited. Light, Drager, and Currall (2012) compared AAC technology supportive of just-in-time programming with AAC technology less supportive of just-in-time programming, and found three young children with intellectual and developmental disability (IDD) who participated in the study took an average of twelve more turns in a 15 min play interaction using the just-in-time supportive AAC than they did using the other AAC technology. Light and colleagues (2012) also report a follow-up study in which five young children with IDD took more turns using AAC supportive of JIT programming than with traditional AAC – an average of 16 more turns in this condition during the 15-min play interaction. Drager and colleagues (2017) measured the impact of an AAC intervention using just-in-time technology on the frequency of turns in 15-min produced by adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities in shared context activities. The nine participants (aged 8–20 years) demonstrated an average increase of 26 turns from baseline to intervention. In both of these studies, an external camera captured photos to send to a computer for use as VSDs.

The current study represents an early step toward evaluating the impact of AAC technology featuring VSDs and just-in-time programming support on the communication of preadolescents/adolescents with intellectual and developmental disabilities who are beginning communicators. It furthers the prior research by exploring the effects of mobile technology containing an app featuring VSDs and just-in-time programming (via an onboard camera) on the frequency of communication turns expressed by preadolescents/adolescents.

Research question

This study was completed to evaluate AAC mobile technology featuring VSDs and just-in-time programming support. Specifically, this study addressed the following question: what is the effect of AAC mobile technology featuring VSDs and the just-in-time programming of contextually-relevant vocabulary on the number of communication turns taken by preadolescents and adolescents who were beginning communicators during 15-minute interactions? It was hypothesised use of AAC designed to minimise demands (through simple, intuitive operational features) and maximise meaningfulness (through contextually-relevant colour photos) for beginning communicators would increase their communicative frequency.

Method

Research design

A multiple baseline across participants single-subject experimental design was used to address the above questions (Baer, Wolf, & Risley, 1968). Multiple-baseline designs are well suited for AAC intervention research as they provide experimental control while allowing for the inclusion of participants from low-incidence and heterogeneous populations (McReynolds & Kearns, 1983). The independent variable of the current study was a mobile technology AAC device with a communication app featuring VSDs and just-in-time programming support allowing for in-the-moment creation of VSDs and content from the reesarchers. The dependent variable was the number of communication turns taken by the participants in a 15-min interaction. The study had two phases: (a) baseline, and (b) the treatment phase during which mobile technology with the AAC app was introduced. The first leg of this design was implemented across three participants. The results were replicated through a second leg of the design involving two participants. Splitting the design into two legs avoided some participants spending a large amount of time in baseline. Illness-related absences and snow days precluded the collection of maintenance data before the end of the school year. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the authors’ university before recruitment began.

Participants

Participants met the following criteria: (a) they were between 9 and 21 years of age (preadolescent or adolescent); (b) they had speech that was inadequate to meet their daily communication needs as a result of an IDD; (c) they were beginning communicators, defined as using less than 50 words/symbols expressively with consistency (Romski et al., 2002); (d) they demonstrated intentional communication; (e) they were able to recognise photos of people or objects; and, (f) they had sufficient motor control to use direct selection on a touch screen (with a whole hand or isolated point). Participants were recruited through school professionals.

A total of five preadolescents/adolescents with IDD participated in the study. Table I summarises the demographic characteristics of these five individuals. The students ranged in age from 9 years to 18 years. The participants had a range of developmental disabilities impacting their speech and language development, including autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, fetal alcohol syndrome, and chromosomal variations. Four of the five participants had multiple disabilities. All of the children used fewer than 25 words symbolically at the start of the study, and their speech was inadequate to meet their communication needs as judged by their speech-language pathologists. Additionally, all five participants used unaided and aided means to communicate. The unaided methods included idiosyncratic gestures, select formal signs, and some speech approximations. The aided means ranged from use of tangible objects to basic grid display options with voice recording capabilities. All of the participants were equipped with some form of speech-generating device (SGD) at the time of the study. The individuals were all receiving speech and language services at the time of the study. All five participants were educated through local school districts via a segregated special education classroom and were assigned a one-on-one aide with the goal of supporting their daily needs and their participation in classroom activities.

Table I. Characteristics of the participants and their AAC systems at the start of the study.

| Participant | Carver | Jason | Jose | Nathan | Amanda |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Female |

| Age | 9 years; 8 months | 14 years; 4 months | 18 years; 11 months | 13 years; 11 months | 14 years; 5 months |

| Disability | Autism spectrum disorder | Multiple disabilities, including cerebral palsy, ID, spastic quadriplegia, and seizure disorder |

Multiple disabilities, including cerebral palsy, ID, encephalopathy, spastic quadriplegia, seizure disorder, and CVI |

Multiple disabilities, including partial Trisomy 18, hearing impairment, seizure disorder, and vision impairment |

Multiple disabilities, including fetal alcohol syndrome, ID, chromosomal abnormalities, seizure disorder, ADHD, and disruptive behavior disorder |

| Unaided means of communication |

Physical communication and ~ 5 signs |

Physical communication, gestures (e.g. head shaking), and vocalisations |

Physical communication and gestures (e.g. eye rolling) |

Physical communication | Physical communication, gestures, and 5–10 signs |

| Aided means of communication |

Picture communication book with photographs and PCS™ icons and BIGmacks |

Trialed both Tech Talk 8 and Tech Talk 32 |

iTalk2 with ‘yes’ and ’no;’ Quicktalker S (two) |

ProxPAD™ with tangible symbols |

SuperTalker |

| Nature of aided concepts available |

Preferred objects and activities (e.g. ’YouTube’) |

Core vocabulary (e.g. ’ready,’ ‘again’) |

Yes/no; greetings | Core vocabulary (e.g. ’me’) and favorite objects (e.g. ‘book’) |

Core vocabulary (e.g. ‘go,’ ‘more’) |

| Number of aided communication concepts available |

≈ 30 | 8 or 32, dependent on device available |

4 | ≈ 12 | 8 |

| Number of aided communication concepts used expressively^ |

≈ 10 | < 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Mobility | Ambulatory | Personally- and partner- controlled wheelchair |

Partner-controlled wheelchair |

Partner-controlled wheelchair |

Partner-controlled wheelchair |

| Educational contexts |

1:1 aide and self- contained autism support classroom for majority of the day |

1:1 aide and self- contained multiple disabilities support classroom for majority of the day |

1:1 aide and self- contained multiple disabilities support classroom for majority of the day |

1:1 aide and self- contained multiple disabilities support classroom for majority of the day |

1:1 aide and self-contained multiple disabilities support classroom for majority of the day |

| Interests and preferred activities |

Music, puzzles, gross motor activities |

Hockey, music, YouTube videos, computer games |

Friends, photographs of past memories, sneakers, dances |

Football, John Deere tractors, music, and YouTube videos |

Fashion, looking at magazines, kittens, music |

NOTE: Pseudonyms were used for each participant; ID is an abbreviation for intellectual disability; ADHD is an abbreviation for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; CVI is an abbreviation for cortical visual impairment

Expressive use of available aided AAC concepts was based on teacher report and observation.

Materials

Only materials representing leisure activities that frequently occurred in participants’ classrooms (e.g. magazines, a music player) were utilised as interaction contexts in the current study. Prior to the start of the study, the researcher discussed with school professionals those classroom activities most of interest to each participant. Additional information was gleaned as to what content interested participants within each activity (e.g. Amanda liked to look at fashion magazines; Jose liked to listen to Shakira). In all, materials used included: magazines, a music player, puzzles, adapted books, and a tablet with access to YouTube and games. Any materials brought in by the researchers mirrored those naturally-occurring within the classroom. One adaptation to classroom material was researcher-created adapted books. These were created due to the limited availability of age-appropriate, high-interest books in the classroom. The adapted books included large, colour photographs from the internet with single words or simple sentences below the pictures on each page. The content of each book was based on participant interests. For instance, one interaction context for Nathan was adapted books featuring people using John Deere tractors on their farms. The photos from adapted books were sometimes programmed as VSDs in intervention. In addition to these leisure-related materials, the participants’ current AAC devices (e.g. a picture communication book) were used in baseline. Mobile technology with the AAC app under investigation was used throughout intervention and served as the independent variable.

EasyVSD on mobile technology.

The study used an AAC app on mobile technology. More specifically, EasyVSD (under development by InvoTek; www.invotek.org) – an AAC app with VSDs and ‘just-in-time’ programming features – was used. Mobile technology (i.e. Samsung Galaxy Tab 10.1) with a capacitive and electromagnetic 10.1 inch widescreen housed the app. The tablet and app had the ability to take photos for VSDs, record voice messages for hotspots (creating digitised speech output), and transfer/backup files via Bluetooth.

The EasyVSD app included a menu that appeared in a vertical layout on the left hand side of the screen. This menu supported navigating, with VSD activities represented by thumbnail representations of the first VSD in the activity. After selection of the activity thumbnail, a second menu bar immediately appeared directly to the right of the first activity menu. The second menu bar provided thumbnails of the specific VSDs within the activity selected and allowed navigation from one page to the next. The menu also included programming the following programming tools: taking a photo for a VSD, programming a photo with a hotspot, recording voice output onto a hotspot, and drawing on VSDs (feature not used in the current study).

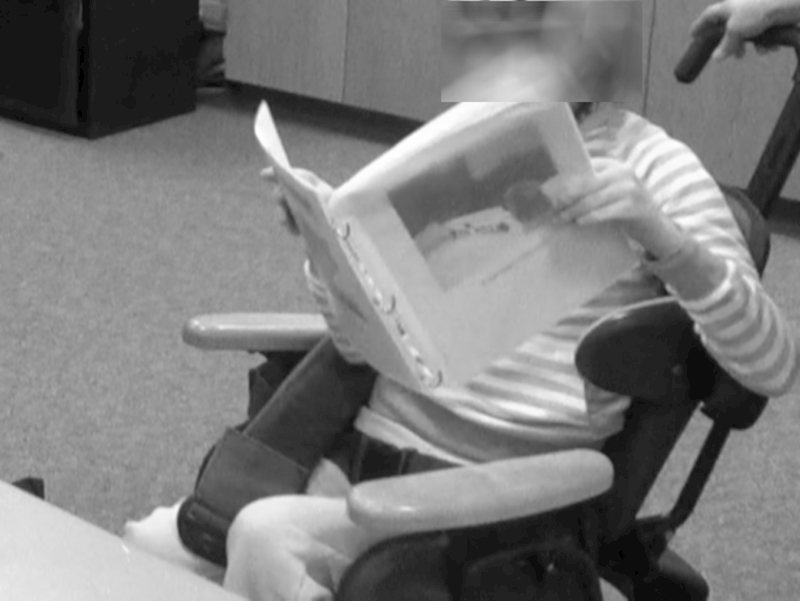

All programming, to support communication during the intervention, was completed just-in-time during the session. As an example of JIT use, if an adolescent enjoyed looking at books, the researcher could use the camera onboard the tablet to snap a photo of the adolescent interacting with the book within the EasyVSD app. The photo would automatically be utilised by the app as a VSD, similar to the VSD exampled in figure 1. Then, the researcher could create a ‘hotspot’ to embed aided AAC content within the VSD (e.g. ‘read’). This VSD with a hotspot could then be used immediately by the adolescent to communicate within the context in which the scene was captured. That is, the adolescent could touch-activate the hotspot to express ‘read’. If more than one VSD was created for that context, the other VSDs would appear in the vertical menu for selection. The app allowed for any number of hotspots to be created on a VSD; however, for the purposes of the current study, no more than three hotspots were programmed per VSD.

Figure 1.

Visual scene display of Amanda looking at a book with the area of the hotspot circled; the hotspot was embedded with the concept ‘read’ (face blurred for publication purposes only).

Procedure

All of the sessions across phases (i.e. baseline, treatment) took place at the participants’ schools. Four of the individuals participated in the study in an extra classroom at the high school they attended and one of the individuals participated in his autism support classroom at the school he attended. Sessions always occurred late morning. As noted earlier, all sessions (baseline and intervention) involved interactions in contexts that were: (a) motivating to the participants; (b) age appropriate for preadolescent/adolescents; (c) able to support numerous opportunities for engagement and communication; and (d) representative of typical leisure activities within the participants’ classroom. Each session lasted approximately 15 minutes and followed the same procedures. The procedures included wait time, prompting, and modeling to support participants’ communication. These communication strategies were held consistent throughout the study in order to evaluate the AAC technology itself and not varying strategies to teach AAC use. The first and second authors conducted all sessions.

Baseline phase

At the beginning of each session, the researcher presented the participant with a choice of two activities. The choice made by the participant would become the first activity of the session. If the participant did not make a choice, a new choice of two different activities would be offered. If the participant still did not make a choice, a response would be modeled by the researcher and the activity chosen in the model would become the first activity of the session. After the leisure activity began, the researcher followed this sequence: (a) participate in the activity with the participant for 30 to 45 s, (b) make a comment or ask a question, (c) wait at least 5 s for a response, (d) if no response, gesturally and/or verbally prompt use of aided AAC device, (e) wait at least 5 s for a response, (f) if no response, model AAC use, and (g) respond to participants’ communication or expand on model. This sequence was repeated throughout the length of the activity. When participants initiated communication without a comment or question from the researcher, the researcher responded and the sequence repeated. At the natural end of each activity (e.g. the end of a video, the end of a game), the researcher would repeat the provision of a choice and the communication partner strategies cycle. This cycle continued for the 15-min span of each session. The EasyVSD app was not present in this phase.

Treatment phase

The researcher followed the same procedures from baseline during the treatment phase. The difference between the two phases was the introduction of the AAC technology being evaluated. Treatment sessions were the only time during which participants had access to the app. The technology did not contain any pre-programmed messages at the onset of the treatment phase, so all VSDs and embedded concepts were programmed just-in-time. It took about 25 s to program a VSD with two hotspots. Decisions about content to program were based on interest demonstrated by participants. For instance, if a participant regularly returned to a specific page of a book, that page would be programmed as a VSD; if a participant laughed especially heartily at a specific point in a video, a still screen view of that point in the video would be programmed. The concepts embedded into the VSDs were single words or simple phrases to cater to the language profiles of the participants; the concepts were not recorded with the goal of being combined syntactically as the participants were in the early stages of using single symbolic concepts expressively. Concepts were chosen based on the flow of the interaction and the behaviour of participants. For example, when Jason threw his hands in the air every time the chorus from the song ‘Happy’ began, ‘happy’ was chosen as the concept to be embedded into a VSD depicting that point in the music video. Only one to three concepts were embedded within each VSD to minimise motor demands for the participants as fine motor movement was a major limitation for the majority of participants. After content was programmed into a participants’ user profile on EasyVSD, that content was available throughout the remainder of the study for the participant to use again.

Session procedures during the treatment phase were identical to those in the baseline phase except for that (a) the researcher programmed aided AAC content just-in-time into EasyVSD in response to participant interest, and (b) all prompting and modeling occurred on the intervention technology rather than participants’ existing technologies used in baseline. So, for example, after ‘happy’ was programmed based on Jason’s interests, Jason would be prompted to express ‘happy’ using the app if he did not do so spontaneously. If he did not respond to the prompt, the researcher would model the use of ‘happy.’

Phase changes.

After a stable or downward baseline trend was observed (defined by a slope less than +0.1 across the baseline data points) and at least five baseline sessions had occurred (Kratochwill et al., 2010), the treatment phase was initiated for the first two participants in each leg of the design (Carver, Nathan). After a treatment effect was observed for these participants, defined as data at least 50% higher than the highest baseline data point across three consecutive sessions, the treatment phase began for the next participants. After the second participant in the first leg (Jason) demonstrated a treatment effect, the treatment phase was initiated for the third participant in the first leg (Jose). The treatment phase ended for each participant after (a) the participant communicated at a frequency at least double his or her average communication frequency in baseline, and (b) the participant had completed at least five sessions in this phase, in accordance with single subject standards (Kratochwill et al., 2010).

Procedural reliability.

In order to ensure all procedures were implemented as intended, a randomly selected sample constituting over 20% of baseline and treatment phase sessions for each participant was checked against researchers’ implementation of the procedure sequence by a trained graduate student in speech-language pathology. Training consisted of calibration on a randomly selected video with the first author. Agreement from the calibration session was above 90%. Procedural reliability was calculated by dividing each step of the procedure correctly followed by the total number of steps and multiplying by 100 to yield a percentage. For the first author who implemented the study with four participants, average procedural reliability was: 95.54% for Jason (range=93.97%−96.91%), 93.27% for Jose (range=88.88%−95.65%), 95.49% for Nathan (range=93.22%−97.66%), and 95.15% for Amanda (range=93.27%−97.01%). For the second author who conducted the study with Carver, average procedural reliability was 89.53% (range=84.62%−93.22%).

Data collection and analysis

Data collection.

Data were collected via video recordings of each intervention session. If a session was longer than 15 minutes, a randomly selected 15-min segment of the interaction was used to measure the dependent variable. A graduate student in speech-language pathology watched the videos to code the dependent variable. The graduate student was provided with the researcher’s definition of communication turns and practiced coding example behaviours before reviewing the videos. The graduate students’ transcriptions were checked periodically to ensure they continued along the initial definition of a turn. A communicative turn was defined as any symbolic communicative act understood by the partner including speech or speech approximations, conventional gesture, sign or sign approximations, and/or use of aided AAC (Drager et al., 2017; Light et al., 2012). Turns could occur at any point within or outside of the procedural sequence and therefore could have occurred spontaneously or after prompting or modeling. Attempts were made to discount any turns appearing unintentional. Activations on aided AAC were not considered turns if the participant’s face was not oriented toward the device or if the participant activated the device multiple times in immediate succession as a result of lack of withdrawal of his or her hand from the device (e.g. the touch screen).

Data analysis.

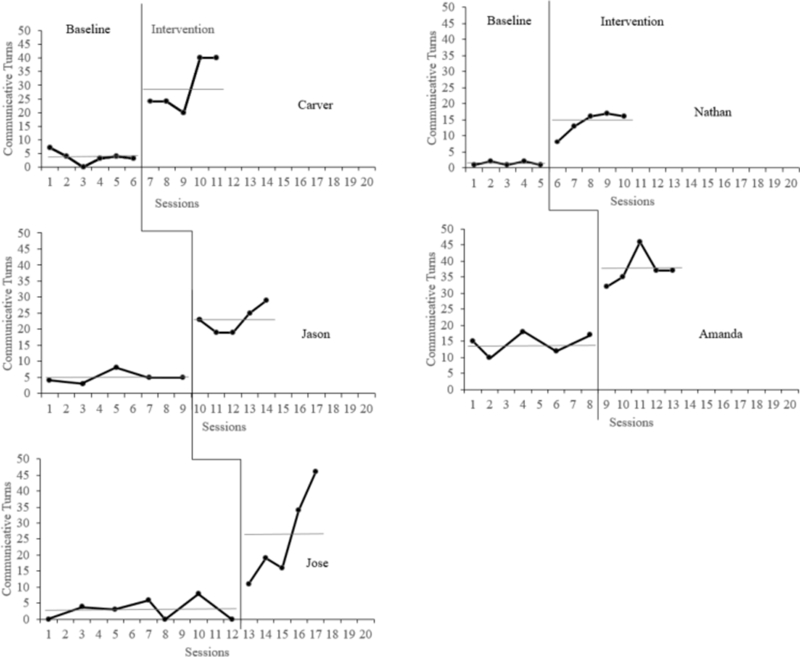

Data were visually analysed in accordance with What Works Clearinghouse standards (Kratochwill et al., 2010) to determine if ‘the data pattern in one phase (e.g. an intervention phase) differs more than would be expected from the data pattern observed or extrapolated from the previous phase (e.g. a baseline phase)’ (Kratochwill et al., 2010, p. 17). As per What Works Clearinghouse recommendations, six data-pattern features – level, trend, variability, immediacy of the effect, overlap, and consistency of data patterns across similar phases – were examined. Taken together, these features of the data were interpreted to determine if experimental control was established and change in the data was caused by the introduction of the independent variable. ‘Best fit’ lines were added to the graphs to illustrate the level and trend of the data in each phase for each participant (See figure 2).

Figure 2.

Communicative turns taken by each of the adolescents across 15 min baseline and intervention sessions.

Reliability.

In order to ensure the reliability of the data, a second coder – an undergraduate honors student – independently coded 20% of the data. Calibration was completed before reliability was conducted as with procedural fidelity, with a 90% or higher signaling fitness to begin independent reliability coding. This occurred after only one calibration session. Reliability was calculated across both phases and included 20% of sessions for Nathan, Jason, and Amanda; 27% of sessions for Carver; and 25% of sessions for Jose. The coders were blind to the goal of the study but were not blind to the condition of the study as it was easily apparent from the video whether or not mobile technology with an AAC app was available. Interrater agreement was calculated by determining the number of point-by-point agreements divided by the number of agreements plus disagreements plus omissions multiplied by 100. Mean interrater reliability was 91% (range from 80% to 100%) across all participants.

Result

Figure 2 presents the data on number of communicative turns for each participant in baseline and intervention. Based on visual analysis, the level of data of communication turns was markedly higher in intervention than baseline for all five participants. The immediacy of the effect, as judged by comparing the final three baseline data points and the initial three intervention points, increases viewer confidence that the change noted was a result of the intervention (Kratochwill et al., 2010). This visual analysis also corresponded to large increases in average turns across the two phases for all participants (an average +26 turns for Carver, +18 for Jason, +22 for Jose, +13 for Nathan, and +23 turns for Amanda per 15-min interaction). Additionally, at least some upward trend was noted in the intervention phase for each participant when comparing the initial and final session data points.

Discussion

The increase in communication turns demonstrate by all participants suggests the communication app on mobile technology programmed just-in-time with contextually-relevant VSDs was effective in promoting communication frequency. These results deliver preliminary evidence that people who have IDD and are in the early stages of language development as preadolescents/adolescents may benefit from access to AAC with such features. The approximate average increase of just over +20 turns per 15-min interaction is consistent with previous presentations utilising similar technology (without the use of a tablet with an onboard camera) that reported average effects of +16 turns for young children with IDD and +26 turns for adolescents with IDD during 15-minute play or shared-context activities (Light et al., 2012 and Drager et al., 2017, respectively). It is interesting the older beginning communicators across two studies demonstrated consistently larger turn increases than did young children. Clearly, it is never too late for effective AAC intervention. Results from this study serve as yet another clear demonstration that preadolescents/adolescents with IDD, including those with multiple disabilities and beginning communicator profiles, benefit from intervention utilising high tech AAC.

The effects observed in the current study were large and immediate. Due to the nature of the current study, it is impossible to know which aspect of the independent variable contributed for these pronounced gains. Although only hypotheses can be generated, a few likely hypotheses based on language development theory are outlined below.

One explanation in the large impact of the current intervention is the power of providing beginning communicators with concepts grabbed from the immediate context for them to use within the same context (Smith & Gove, 2003). This was a major difference between the intervention technology and participants’ baseline technologies. Three of the participants had access to largely ‘core’ vocabulary, which is inherently not specific to any particular context. A couple participants did have access to some concepts specific to the current context (e.g. Jason had ‘YouTube’, Nathan had ‘book’) on their baseline technologies, but these were general descriptors of the activity rather than highly-motivating vocabulary that can be used within the activities (e.g. a word from a song when watching a music video on YouTube). The app was designed to support just-in-time programming in order to allow for the quick and easy programming of concepts and representations (i.e. photos) from the immediate communicative context in which the concepts would go on to be expressed.

The colour photo representations themselves may have also accounted for some of the increase in communicative frequency (although Carver’s baseline aided AAC technology included some photo representations). Given that colour photos are highly recognisable representations, they may have rendered the vocabulary concepts more linguistically accessible to the participants than the representation options from their baseline technologies (e.g. line drawings) (Mirenda & Locke, 1989). The VSD layout may have similarly supported participants’ communication by imposing less demands than the low- or mid-tech grid options most of the participants used in baseline (i.e. Jose, Amanda, Jason, and Carver) (Light & Drager, 2007; Thistle & Wilkinson, 2013). The limited number (1–3) and large size of hotspots programmed on the VSDs also probably served to minimise motor demands and support access to aided AAC concepts despite motor limitations. Finally, the use of a high-tech, mainstream device (i.e. a tablet) to house the participants’ communication may have drawn interest and motivated an increase in interaction.

Clinical implications

This study provides evidence preadolescents/adolescents can see huge gains in communication when provided with AAC intervention designed to maximise their participation and minimise demands. Early intervention is important and effective, but individuals as old as 18 in this current study increased their communication quickly and markedly with access to theoretically-driven technology. When considering this study alongside previous evidence involving a high level of technology, visual scene displays, and just-in-time programming, evidence is building that these features are powerful aspects of AAC intervention for speech-language pathologists to employ with preadolescent/adolescent beginning communicators. Unfortunately, given the large number of differences between participants’ baseline technologies and the technology used in intervention, it is not possible from the current study for speech-language pathologists to decipher which particular features may have been most clinically useful.

Limitations and future directions

The current study provided preliminary evidence a mobile technology-housed AAC app featuring VSDs and just-in-time programming support can increase the expressive communication in preadolescents/adolescents with IDD who are beginning communicators. This finding is promising considering changes to AAC technology may be one of the simplest ways to promote better communication outcomes (Holyfield, Drager, Kremkow, & Light, 2017). Given the preliminary nature of the current study, however, there are several important limitations affecting the application and reach of the findings. The greatest limitation of the current study was the sample size (n=5). The generalisability of the results are severely restricted by the limited number of preadolescents/adolescents who participated. Another major limitation of the current study was the lack of maintenance or generalisation data. Information on the maintenance of any effects measured in single subject research and the generalisation of those effects to other contexts, communication partners, or stimuli are crucial markers of the value of an intervention and its validity within the real world (Schlosser & Lee, 2000). Absences and the end of the school year did not allow for maintenance data to be gathered. More time should have been allotted to the study, especially considering the medical complications that can accompany the lives of individuals with multiple disabilities. The preliminary nature of the current study is reflected in the small number of participants and lack of generalisation and maintenance data. Other limitations in the current study include: (a) the context of the intervention – despite using only leisure activities found in the classroom, the interactions occurred with an unfamiliar partner (i.e. the researcher) outside of normally-scheduled classroom activities, (b) the heterogeneity of the participants’ ages, diagnoses, and language/communication profiles (although this served to bolster the generalisability of the results), and, finally, (c) the multiple differences between the intervention AAC technology and baseline AAC technology (e.g. introduction of mobile technology, visual scene display layouts, just-in-time programming support, and contextually-relevant representations and vocabulary) precluding any conclusions being safely drawn about which aspects of the intervention technology were most effective or in fact at all effective.

Clearly, future research is needed to build upon the preliminary findings reported within the current results to begin to paint a fuller picture of AAC technological changes that may be most beneficial to older beginning communicators. Future research should continue to evaluate the technology features in the current study with more preadolescents, adolescents, and other age groups of early language learners (e.g. adults). Of course, measuring the maintenance of any future findings as well as their generalisation would likely provide valuable insight. In future research, ‘more care needs to be taken in selecting appropriate designs for evaluating generalisation and maintenance effectiveness while considering the range of available strategies for promoting generalisation and maintenance’ (Schlosser & Lee, 2000, p. 221). An additional step could explore the effectiveness of the current AAC technology as it is implemented by school professionals during school activities. Future research could also assess the (a) viability and (b) implications of including beginning communicators in the programming process. Given the procedures of the current study did not systematically provide the preadolescents/adolescents opportunities to be physically involved in the communication process, future research could build off the current study by comparing outcomes when beginning communicators are and aren’t provided the opportunity to be actively involved in the programming process (Holyfield et al., 2017). Finally, future research could address some of the questions emerging from the current preliminary study by systematically manipulating a single feature at a time, or, as research has been completed, analysing the published research by conducting component analyses (for an example from another field, see Fantuzzo, King, & Heller, 1992) to identify elements that may be most impactful on the communication of its users. Conversely, future research could use the app within a more comprehensive intervention – a huge need in AAC research (Light, 1999).

Conclusion

There are multiple ways to promote a person’s success in completing a task, such as the task of communication via aided AAC. One option is to reduce the additional demands aided AAC technology places on the person (Light & Drager, 2007). The technology utilised in the current study followed a theoretically-driven approach to reduce motor, visual, (Thistle & Wilkinson, 2013), cognitive (Schlosser et al., 2015), and linguistic (Light & Drager, 2007) demands of use. Such an approach appears promising for preadolescents/adolescents who are beginning communicators. Through accessible, theoretically-driven AAC technology, these individuals can make huge gains in their expressive communication.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded through Grant #1R43HD059231-01A1 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. In addition, the first and second authors were supported by funding from the Penn State AAC Leadership Project, a doctoral training grant funded by U.S. Department of Education grant #H325D110008.

Footnotes

This article includes a word which is or is asserted to be a proprietary term or trade mark. Its inclusion does not imply it has acquired for legal purposes a non-proprietary or general significance, nor is any other judgement implied concerning its legal status. PCSTM is a Mayer-Johnson® product; a BIGmack is a light-tech, single-message, single-button voice output device manufactured by Ablenet®; the Tech Talk 8 and Tech Talk 32 are light-tech devices with grid displays allowing for up to 8 or 32 messages, respectively, and are manufactured by AMDi; iTalk2 is a two-message/two-button speech output device manufactured by Ablenet®; Quicktalker S devices are single-message, proximity-activated voice output options manufactured by Ablenet®; SuperTalker is a light-tech, voice output device featuring a grid display of up to eight messages manufactured by Mayer-Johnson®; the ProxPadTM plus Tangibles Kit is a light-tech option, proximity-activated voice output option manufactured by Logan® Tech.

References

- Baer DM, Wolf MM, and Risley TR (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 1, 91–97. 10.1901/jaba.1968.1-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banda DR, Copple KS, Koul RK, Sancibrian SL, & Bogschutz RJ (2010). Video modelling interventions to teach spontaneous requesting using AAC devices to individuals with autism: A preliminary investigation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32, 1364–1372. 10.3109/09638280903551525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beukelman D, & Mirenda P (2013). Augmentative and Alternative Communication: Supporting Children and Adults with Complex Communication needs (4th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Cafiero J (2001). The effect of an augmentative communication intervention on the communication, behavior, and academic program of an adolescent with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 16, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Caron J, Light J, & Drager K (2016). Operational Demands of AAC Mobile Technology Applications on Programming Vocabulary and Engagement During Professional and Child Interactions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 32, 12–24. 10.3109/07434618.2015.1126636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager KD, Light J, Currall J, Muttiah N, Smith V, Kreis D, … & Wiscount J (2017). AAC technologies with visual scene displays and “just in time” programming and symbolic communication turns expressed by students with severe disability. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 1–16. 10.3109/13668250.2017.1326585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, King J, & Heller L (1992). Effects of reciprocal peer tutoring on mathematics and school adjustment: A component analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84, 331 10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz JB, Sigafoos J, Simpson RL, & Cook KE (2008). Generalization of a pictorial alternative communication system across instructors and distance. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24, 89–99. 10.1080/07434610802113289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield C, Drager KD, Kremkow JM, & Light J (2017). Systematic review of AAC intervention research for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 1–12. 10.1080/07434618.2017.1370495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holyfield C, Drager K, Light J, & Caron JG (2017). Typical toddlers’ participation in “Just-in-Time” programming of vocabulary for visual scene display augmentative and alternative communication apps on mobile technology: A descriptive study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 26, 737–749. https://doi:10.1044/2017_AJSLP-15-0197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratochwill TR, Hitchcock J, Horner RH, Levin JR, Odom SL, Rindskopf DM & Shadish WR (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation Retrieved from What Works Clearinghouse website: http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf.

- Light J (1999). Do augmentative and alternative communication interventions really make a difference?: The challenges of efficacy research. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15, 13–24. 10.1080/07434619912331278535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, & Drager K (2007). AAC technologies for young children with complex communication needs: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 23, 204–216. 10.1080/07434610701553635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, Drager K, & Currall J (2012, November). Effects of AAC systems with ‘just in time’ programming for children with complex communication needs. Presentation at the annual convention of the American Speech Language Hearing Association, Atlanta, GA: Retrieved from Pennsylvania State University; AAC website: www.aac.psu.edu. [Google Scholar]

- Light J, Drager K, McCarthy J, Mellott S, Millar D, Parrish C, … & Welliver M (2004). Performance of typically developing four-and five-year-old children with AAC systems using different language organization techniques. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20, 63–88. 10.1080/07434610410001655553 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McReynolds L, & Kearns K (1983). Single-Child Experimental Designs in Communicative Disorders University Park Press; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Mirenda P (1997). Supporting individuals with challenging behavior through functional communication training and AAC: Research review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 13, 207–225. 10.1080/07434619712331278048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirenda P, & Locke P (1989). A comparison of symbol transparency in nonspeaking persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 54, 131–140. https://doi:10.1044/jshd.5402.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichle J, Beukelman D, & Light J (2002). Exemplary Practices for Beginning Communicators: Implications for AAC Brookes Publishing Company; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Romski MA, Sevcik RA, Hyatt AM, & Cheslock M (2002). A continuum of AAC language intervention strategies for beginning communicators. In Reichle J, Beukelman D, & Light J (Eds.), Exemplary Practices for Beginning Communicators: Implications for AAC (pp. 1–23). Brookes Publishing Company; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser R, & Lee D (2000) Promoting generalization and maintenance in augmentative and alternative communication: A meta-analysis of 20 years of effectiveness research, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16, 208–226. 10.1080/07434610012331279074 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser R, Shane H, Allen A, Abramson J, Laubscher E, & Dimery K (2015). Just-in-time supports in augmentative and alternative communication. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 1–17. 10.1007/s10882-015-9452-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith M, & Grove N (2003). Asymmetry in input and output for individuals who use AAC. In Light J, Beukelman D, & Reichle J (Eds.), Communicative Competence for Individuals who use AAC (pp. 163–195). Brookes Publishing Company; Baltimore, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Thistle J, & Wilkinson K (2013). Working memory demands of aided augmentative and alternative communication for individuals with developmental disabilities. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 29, 235–245. 10.3109/07434618.2013.815800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier N, Kamp L, & Mirenda P (2011). Effects of peer-mediated instruction to teach use of speech-generating devices to students with autism in social game routines. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27, 26–39. 10.3109/07434618.2010.546810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]