Abstract

CBT is considered the first-line treatment for anxiety disorders, particularly when it involves gradual confrontation with feared stimuli (i.e., exposure); however, delivery of CBT for anxiety disorders in real-world community clinics is lacking. This study utilized surveys we developed with key stakeholder feedback (patient, provider, and administrator) to assess patient and provider/administrator perceptions of the barriers to delivering (or receiving) CBT for anxiety disorders. Providers/administrators from two counties in California (N=106) indicated lack of training/competency as primary barriers. Patients in one large county (N=42) reported their own symptoms most often impacted treatment receipt. Both groups endorsed acceptability of exposure but indicated that its use in treatment provided/received had been limited. Implications and recommendations are discussed.

Anxiety disorders are among the most prevalent mental disorders (Kessler et al., 2005) and are associated with significant disability (Stein et al., 2005), medical utilization (Deacon, Lickel & Abramowitz, 2008), and cost (Greenberg et al., 1999). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that includes exposure to feared stimuli as a central component of anxiety disorder treatment is considered one of the most effective treatments that the mental health field has for any psychiatric disorder (Deacon & Abramowitz, 2004). A traditional course of CBT for anxiety disorders includes psychoeducation about fear and anxiety, cognitive restructuring to reduce misappraisals of threat, and exposure to feared stimuli, including bodily sensations of physiological arousal (i.e., interoceptive exposure), distressing images or memories (i.e., imaginal exposure), and situations (i.e., in vivo exposure), with the exposure component considered to be a key active ingredient (Glenn et al., 2013). Despite the robust support for exposure-based CBT in efficacy and effectiveness clinical trials (Stewart & Chambless, 2009), most adults in publicly funded community mental health settings do not receive these interventions (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2015). Researchers and clinicians alike have speculated about why the research-to-practice gap remains for the treatment of adults, but few have attempted to understand this phenomenon empirically. Insights can be garnered from the literature investigating barriers to delivering evidence-based treatments in community-based settings serving children. Across a variety of settings including child welfare, schools, and community mental health, identified barriers include organizational structure, climate and culture (Glisson & Green, 2011), provider knowledge of, attitudes towards, and experience with evidence based treatments (Aarons & Palinkas, 2007; Borntrager et al., 2009; Higa-McMillan, Nakamura, Morris, Jackson, & Slavin, 2015; Stephan et al., 2012 ), and client diversity and complexity (Akin et al., 2014; Wharton & Bolland, 2014). Exploration of whether these barriers emerge in community mental health treatment of anxiety disorders in adults is needed.

In addition to the aforementioned putative barriers at the patient, provider, and organizational levels of the system, many models would suggest that system-wide support for the training and delivery of evidence-based treatments play a role in the uptake of evidence-based treatments such as CBT (Century, Cassata, Rudnick & Freeman, 2012; Damscroeder et al., 2009; Aarons, Hurlburt & Horwitz, 2011). California Proposition 63, known as the Mental Health Services Act (MHSA), was passed in 2004, providing the first opportunity in many years for the California Department of Mental Health (DMH) to provide increased funding, personnel and other resources to support county mental health programs and monitor progress toward statewide goals for children, transition age youth, adults, older adults and families (MHSA, 2004). Since 2004, MHSA funds have supported the infrastructure, technology, and training needed for a number of mental health programs, from prevention and early intervention to treatment for severely disabling mental health conditions. The Vision Statement and Guiding Principles for DSM Implementation of the MHSA (2015) includes a goal to replace ineffective treatments with evidence-based practices (EBPs). As a consequence of the MHSA, dozens of EBPs have been identified on an approved list through DMH (Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health Prevention and Early Intervention Resource Guide 2.0, 2011). However, the majority are for either children or adults with severe mental illness. Moreover, it is unclear to what extent each of these EBPs has been rolled out successfully across agencies (i.e., agencies adopt them, providers are trained in them, and they are implemented and sustained in clinics) within a county or across the state. No systematic efforts to our knowledge have assessed across all service areas in California the extent to which each EBP has been implemented. At present, the list serves as a resource for individual agencies to decide which to adopt. Therefore, work is needed to examine whether the goals of the MHSA are being met for adult mental health patients with anxiety disorders. Given that California has one of the largest populations of any state in the country and has invested government resources specifically to the provision of improving community mental health services, this challenge has implications for the dissemination and implementation of evidence-based care for anxiety disorders nationally.

We sought to understand the extent to which evidence-based treatments, and in particular, exposure-based CBT, were being delivered in publicly funded adult community mental health clinics contracted by DMH. We focused primarily on understanding whether the MHSA is working to address the needs of adults with anxiety disorders in two counties in Southern California. The current study builds directly on our recent qualitative work with a diverse group of stakeholders to begin to understand the barriers to delivering (or receiving) evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review). In the formative qualitative work, we conducted interviews and focus groups with patients, providers, and administrators to better understand the patient, provider, organizational, and system-level barriers to delivering (or receiving) CBT, and exposure in particular. We used the results of qualitative analyses from interviews with patient, provider, and administrators to develop surveys to gather quantitative data from a larger sample of stakeholders. In the present study, we surveyed patients, providers, and administrators across multiple agencies in urban and rural settings to better understand the perceived barriers and facilitators to delivering or receiving exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders.

The primary aim of this exploratory study was to identify perceived barriers, and the secondary aim was to examine the extent to which our qualitative data converged with our quantitative data gathered in the preliminary stage of this larger study. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we made few hypotheses. However, based on prior similar work in clinical settings for children (Aarons & Palinkas, 2007; Akin et al., 2014; Gray, Joy, Plath & Webb, 2013), as well as some work related to patient preferences (Dwight-Johnson et al., 2000; Dwight-Johnson et al., 2010) and therapist experiences, beliefs about, and training in CBT and exposure (Weissman et al., 2006; Herschell et al., 2010; Deacon et al., 2013; Farrell et al., 2013), we hypothesized that patients would find exposure-based CBT acceptable, but that providers would find it less so, or believe they lacked the skills necessary to deliver it.

Methods

Overview of Design

This paper presents the quantitative findings from a larger mixed-methods study utilizing community-based participatory research approach. We partnered with four community mental health centers to gather qualitative and quantitative data to understand the barriers to receiving and delivering exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders in publicly funded adult community mental health settings. Given the developmental, detailed, and iterative process and the use of the qualitative data to inform the quantitative instrument, we reported the qualitative methods and results in a parallel paper (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review). Here we report the quantitative methods and results.

We first conducted (a) key informant interviews with clinic administrators at each of the four community mental health centers, and with the former director of the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health (DMH); (b) focus groups with providers at each of the four clinics; and (c) focus groups with patients with anxiety disorders at two of the four clinics (see Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review for greater detail, including demographic makeup of the patient focus group sample).1 The purpose of the interviews and focus groups was to gather qualitative data regarding each stakeholder’s ideas about anxiety disorder treatment practices, beliefs and preferences regarding anxiety disorders and their treatments, as well as to identify perceived barriers to delivering (or receiving) evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders. Next, we used the qualitative data to develop surveys (one for patients and one for providers and clinic administrators) that reflected the themes that emerged from the focus groups and interviews. Then, we created a small multi-stakeholder panel of patients (n =3) and providers (n = 2) from across the four clinics to work with us to finalize the content of the surveys. The first (KWT) and fifth (JG) authors represented the research team on the panel. The stakeholder panel (with the researchers) met once for several hours to discuss the surveys and provide feedback. Providers also provided additional feedback via email. The qualitative data analysts also provided additional feedback to ensure consistency between the qualitative results and the surveys. We then refined the surveys according to the feedback. Finally, we distributed the patient and provider surveys. For the patient surveys, we worked closely with our community partners to recruit patients with anxiety disorders at those four clinics to participate in the survey. For the provider surveys, we contacted all Los Angeles County clinics with a DMH contract as well as a large network of all DMH-funded clinics in Ventura County. Several clinics (as described below) distributed our survey to their providers via a Web link. The entire study was conducted over a period of one year.

Participants

Participating Clinics

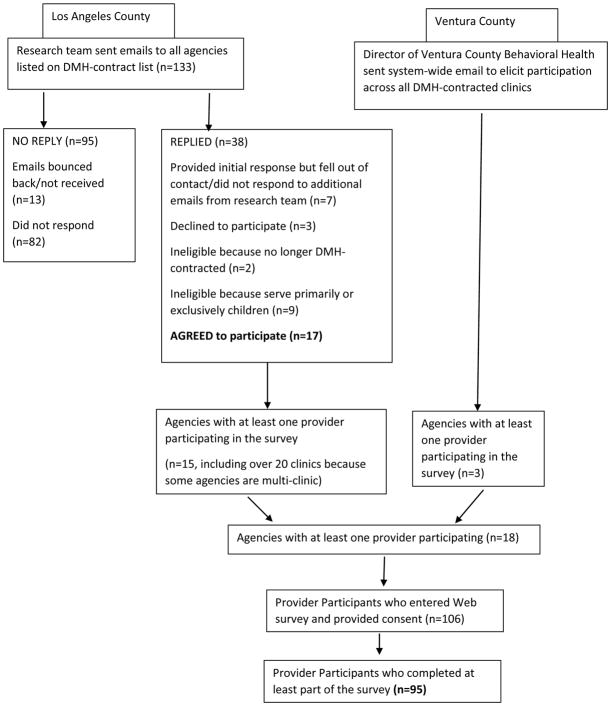

Clinics were recruited for participation based upon their inclusion on a comprehensive list of DMH-contracted providers in Los Angeles County. All clinics on the list were sent an email with information about the study and inquiring whether they would be interested in distributing the surveys to their providers. Providers were eligible if the clinics where they worked were currently DMH-contracted and provided adult mental health treatment services. As an additional measure to increase recruitment in rural service areas, we contacted administrative leadership at the Ventura County Behavioral Health, a large network of DMH-funded clinics and agencies located to the northwest of Los Angeles County, and sought assistance in disseminating the survey to eligible providers. The survey information and link was sent to all Ventura County Behavioral Health agencies. Details of the flow of recruitment across clinics are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow of Recruitment across Clinics

Participating Providers

Providers and clinic administrators were eligible to participate in the survey if they provided (or supervised) adult mental health services at a DMH-contracted community mental health agency in Los Angeles or Ventura County. 106 providers across the 18 participating agencies entered the survey, and 95 providers completed one or more sections of the surveys. See Table 1 for demographic characteristics of the provider sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Provider/Administrator Sample

| Demographic/Professional Characteristic | Mean (SD) or % | N |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 40.39 (11.17) | 88 |

| Female gender | 78.9 | 95 |

| Race/Ethnicity | 94 | |

| Caucasian/White | 53.2 | |

| Hispanic/Latino/a | 22.4 | |

| African-American/Black | 8.5 | |

| Asian-American/Pacific Islander | 7.4 | |

| Native American | 1.1 | |

| Multiracial | 5.3 | |

| Other | 1.1 | |

| Employed in Los Angeles County | 89.4 | 94 |

| Degree | 95 | |

| High School | 6.3 | |

| Associates Degree | 2.1 | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 7.4 | |

| LPN | 1.1 | |

| MFT | 37.9 | |

| MSW | 24.2 | |

| PhD – clinical psychology | 2.1 | |

| PhD – non-clinical psychology | 1.1 | |

| PsyD | 5.3 | |

| MD | 6.3 | |

| Other | 6.3 | |

| Years of post-graduate professional experience | 88 | |

| 0–4 | 46.2 | |

| 5–9 | 20.4 | |

| 10–14 | 11.8 | |

| 15+ | 21.5 | |

| Licensed | 46.8 | 88 |

| Primary Clinical Role | 95 | |

| Therapist/counselor | 54.7 | |

| Clinical supervisor | 8.4 | |

| Clinic administrator | 13.7 | |

| * Other (case worker, social worker, psychologist, psychiatrist, nurse) | 23.2 | |

| Identifies theoretical orientation as cognitive, behavioral, or cognitive behavioral | 51.7 | 95 |

All categories in “other” were endorsed in fewer than 10% frequency

Participating Patients

Patient participants were recruited from one of the four primary clinics with whom we partnered in our initial qualitative research and stakeholder panel, each of which represented a different geographic area in Los Angeles County (i.e., North Los Angeles, South Los Angeles, West Los Angeles, and East Los Angeles; see Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review, for details). Given the constraints of our agreement with the Los Angeles County DMH and the need to develop established community partnerships with clinics prior to feasibly being able to survey their patient population, we limited the patient surveys to these four clinics with which we had already established a partnership during the qualitative portion of the study.

Forty-two patient participants (Mage = 36.69, SD = 14.73) completed surveys. Participants were 58.5% female and 73.2% spoke English as the primary language spoken at home (with the remaining participants identifying Spanish as their primary language). The patient sample was 31.7% White/Caucasian, 29.3% Hispanic/Latino/a, 12.2% Black/African-American, 7.2% Asian-American or Pacific Islander, 9.8% multiracial, and 9.8% identifying as another race/ethnicity. Most participants had a high school diploma or less (22.0% reporting having completed some high school and 36.6% reporting obtaining a high school diploma or GED as their highest level of education). Most participants (61.0%) were unemployed.

Measures

As described above, a patient survey and a provider/administrator survey were developed from the ideas and themes that emerged from the qualitative data (see Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review), with input from a multi-stakeholder panel. Survey items can be found in the presentation of Results (Tables 1–8).

Table 8.

Perceived Barriers to Care for Anxiety Disorders (Patient Survey, n = 42)

| Does not stop me | Stops me a little bit | Stops me quite a bit | Completely gets in the way | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My fear of having to face the things that I avoid because of my anxiety. | 41.0 | 33.3 | 20.5 | 5.1 |

| Difficulty understanding what my therapist is talking about. | 79.5 | 20.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Feeling like my therapist doesn’t understand me. | 79.5 | 10.3 | 2.6 | 7.7 |

| Transportation difficulties. | 69.2 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 7.7 |

| Childcare issues. | 94.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 0.0 |

| Difficulty leaving work. | 83.8 | 8.1 | 5.4 | 2.7 |

| Difficulty leaving family or caregiving responsibilities. | 89.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 5.1 |

| Medical conditions. | 76.9 | 12.8 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| Conflicting schedules with other medical appointments. | 61.5 | 28.2 | 5.1 | 5.1 |

| Difficulty getting the appointment times I want at the clinic. | 78.9 | 10.5 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Difficulty getting any regularly scheduled appointments. | 76.9 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 5.1 |

| Medication side effects. | 67.5 | 17.5 | 10.0 | 5.0 |

| Depression, which leads to withdrawing from people and wanting to stay home. | 32.5 | 35.0 | 17.5 | 15.0 |

| Fear of going out in the world to get to my appointment. | 57.5 | 27.5 | 7.5 | 7.5 |

| Financial problems. | 55.0 | 22.5 | 10.0 | 12.5 |

Provider Survey

Provider survey items and ratings scales are shown in Tables 2–5. Providers were instructed to consider anxiety disorders to include panic disorder, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder when answering the survey. Sections included (1) demographics; (2) information about the type and level of training received in cognitive and behavioral skills for treating anxiety disorder, first considering graduate/clinical training, and then considering training or supervision received since beginning their clinical position; (3) practices with anxiety disorders; (4) barriers to delivering evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders, with a focus on patient- and provider-level potential barriers; and (5) other potential barriers, with a focus on organizational- and system-level potential barriers. Providers were asked to rate the extent to which they agreed with statements in sections (3) – (5) using a 0 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree) Likert scale. In section (5), since some questions were geared towards administrators/clinic directors and the average clinician might not have the knowledge needed to answer the question, an “I don’t know/not applicable to me” option was included. Internal consistency within each section of the provider survey was good to excellent, with Cronbach’s α ranging from .77 to .91 across the substantive sections of the survey.

Table 2a.

Training and Supervision During Clinical Training Program (Provider Survey, n = 95)

| Technique | Level of Training | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| No training | Workshop | Ongoing didactic training/class | Ongoing training and saw one patient with supervision using this technique | Ongoing training and used this technique with multiple patients under supervision | Used this technique informally with patients while being supervised, but no formal didactic training | |

| Cognitive restructuring | 21.5 | 17.2 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 28.0 | 17.2 |

| In vivo exposure | 58.1 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 8.6 | 12.9 | 5.4 |

| Interoceptive exposure | 78.9 | 6.7 | 2.2 | 2.2 | 5.6 | 4.4 |

| Imaginal exposure | 60.4 | 13.2 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 8.8 | 5.5 |

Table 5.

Additional Perceived Barriers (Organizational- and System-Level) for Patients to Receive Care for Anxiety Disorders (Provider Survey, n = 95)

| Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | I don’t know/ N/A to me | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are many individuals who would benefit from anxiety treatment, but there is no funding stream for them because they are neither first-time service seekers (and thus cannot use the Early Intervention funds) nor do they qualify as severely mentally ill. As a result, we have a hard time offering services to these individuals at our clinic. | 25.6 | 20.5 | 17.9 | 14.1 | 17.7 | 14.1 |

| Most individuals with anxiety disorders who seek our services are looking for benzodiazepine prescriptions, and we don’t know how, or have the right staff, to handle this type of patient. | 46.2 | 20.5 | 16.7 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 9.0 |

| Most individuals with anxiety disorders who seek our services are looking for benzodiazepine prescriptions, and we don’t want to manage these patients. | 50.0 | 22.4 | 14.5 | 2.6 | 3.9 | 6.6 |

| There are insufficient governmental (e.g., DMH) or other funds to provide ongoing training in CBT for anxiety disorders as we have new staff join our team. | 12.8 | 21.8 | 17.9 | 21.8 | 12.8 | 12.8 |

| Few or none of our staff have received formal training in CBT specifically for anxiety disorders. | 20.5 | 19.2 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 17.9 | 11.5 |

| I supervise clinicians and I do not know how to supervise them to deliver high-quality CBT that includes exposure specifically for anxiety. | 28.6 | 9.1 | 15.6 | 5.2 | 3.9 | 37.7 |

| I supervise clinicians and I do not have time to supervise them to deliver high-quality CBT that includes exposure specifically for anxiety. | 25.0 | 10.5 | 15.8 | 6.6 | 2.6 | 39.5 |

| Treating anxiety is not a priority for our clinic or the population we serve. | 59.0 | 20.5 | 11.5 | 3.8 | 1.3 | 3.8 |

| Treating anxiety is only important to treat because it can lead to more severe co-occurring problems (e.g., depression, substance use). | 39.7 | 24.4 | 20.5 | 6.4 | 7.7 | 1.3 |

| Treating anxiety is only important to treat if it exacerbates existing psychopathology. | 44.7 | 27.6 | 19.7 | 1.3 | 5.3 | 1.3 |

| Patients cannot come in regularly enough to benefit from CBT due to their own environmental barriers (e.g., lack of transportation, childcare, inability to leave work). | 20.5 | 25.6 | 19.2 | 28.2 | 2.6 | 3.8 |

| Patients cannot come in regularly enough to benefit from CBT due to constraints in our clinic (e.g., too few clinicians, difficulties scheduling regular appointments). | 35.1 | 26.0 | 19.5 | 14.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| There is too much staff turnover at our clinic to keep a significant number of clinicians trained in CBT at any given time. | 42.3 | 17.9 | 17.9 | 12.8 | 5.0 | 3.8 |

Note: N/A = not applicable (e.g., does not apply)

Patient Survey

Patient survey items and rating scales can be found in Tables 6–8. The patient survey consisted of five sections: (1) demographics; (2) treatment received for anxiety disorders; (3) beliefs and preferences about anxiety treatment; (4) perceived barriers to receiving treatment for anxiety disorders. In sections (2) and (3), participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with statements on a scale from 0 (completely disagree) to 4 (completely agree). In section (4), patients were asked to rate on a 4-point scale the extent to which each potential barrier gets in the way of coming to sessions, from 0 (does not stop me from coming into sessions) to 3 (completely gets in the way of my ability to come to sessions). Internal consistency within each section of the patient survey was excellent, with Cronbach’s α ranging from .81 to .90 across the substantive sections of the survey (i.e., not including demographic information section).

Table 6.

Treatment for Anxiety Disorders Received (Patient Survey, n = 42)

| Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | Not Sure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My therapist has talked to me about my anxiety, and this is part of our treatment plan. | 7.3 | 0.0 | 9.8 | 24.4 | 58.5 | 0.0 |

| My anxiety gets in the way of my life. | 4.9 | 2.4 | 17.1 | 26.8 | 48.8 | 0.0 |

| My anxiety causes me to feel upset and distressed. I’m bothered by having anxiety. | 4.9 | 2.4 | 7.3 | 29.3 | 56.1 | 0.0 |

| My therapist teaches me relaxation skills like breathing differently to calm myself down. | 2.4 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 26.8 | 53.7 | 2.4 |

| My therapist has taught me how my thoughts, feelings, and behaviors all work together when I am anxious. | 2.4 | 9.8 | 4.9 | 24.4 | 56.1 | 2.4 |

| My therapist has taught me how to figure out what I am thinking when I am anxious. | 2.4 | 7.3 | 2.4 | 31.7 | 48.8 | 7.3 |

| My therapist has thought me how to challenge my thoughts when I am anxious, and to help me think differently in situations that make me anxious. | 0.0 | 5.1 | 7.7 | 23.1 | 59.0 | 5.1 |

| My therapist has helped me come up with a list of things I am afraid of or that I avoid. | 5.0 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 20.0 | 42.5 | 2.5 |

| My therapist has helped me to face my fears one at a time. | 7.5 | 5.0 | 25.0 | 17.5 | 42.5 | 2.5 |

| My therapist has taught me that anxiety is not harmful and that it is OK to feel anxious or fearful. | 7.5 | 10.0 | 17.5 | 15.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 |

| My therapist helps me face the physical feelings of anxiety to learn that they won’t harm me. | 5.0 | 12.5 | 15.0 | 27.5 | 37.5 | 2.5 |

| My therapist encourages me to go to places that normally make me afraid. | 12.8 | 12.8 | 25.6 | 20.5 | 25.6 | 2.5 |

| My therapist helps me face the thoughts, images, or memories that make me anxious so I learn to tolerate them and learn they will not harm me. | 5.1 | 10.3 | 15.4 | 17.9 | 46.2 | 5.1 |

| My therapist gives me homework assignments. | 7.5 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 27.5 | 45.0 | 0.0 |

| My therapist checks on my homework assignments to see if I did them. | 10.0 | 7.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 37.5 | 0.0 |

| My therapist has taught me that it is best to avoid the things that make me anxious so I can stay calm. | 12.5 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 22.5 | 32.5 | 2.5 |

| I take medication for my anxiety daily. | 35.9 | 0.0 | 2.6 | 10.3 | 46.2 | 5.1 |

| A psychiatrist prescribes me medication that helps me sleep. | 37.5 | 10.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 37.5 | 5.0 |

| I take medication for my anxiety and fear only when it is really bad, and it quickly calms me down. | 45.0 | 10.0 | 7.5 | 5.0 | 25.0 | 7.5 |

| My therapist and I generally talk about things other than my anxiety. | 5.0 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 15.0 | 55.0 | 10.0 |

| My therapist supports me and listens to my problems, but we don’t really work on specific skills to help my anxiety. | 32.5 | 7.5 | 10.0 | 10.0 | 30.0 | 10.0 |

Procedures

The study was approved by the UCLA Institutional Review Board and by the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health Research Committee. Surveys were created in REDCap, a secure HIPAA-compliant web application for building and managing online surveys. Administrators from each of the participating clinics received emails from the research staff including the access link for the online survey as well as survey instructions to forward to the eligible providers within their clinic. For ease of completion providers completed the surveys online and provided the researchers with their contact information to receive $10 gift cards. The information sheet participants read when initially clicking on the anonymous link informed them that the information they provided would remain only with the research team.

The patient surveys were distributed via hardcopies in the four clinics with which we partnered. The decision to use hardcopies (rather than web links) for the patient survey was based on feedback from all four partnering clinics. Specifically, there was a significant proportion of patients in their clinics without internet access or a computer. Clinic staff offered the survey to patients with anxiety disorders. Recruitment flyers were posted in the main lobbies of the clinics, so patients could self-refer to complete the survey by obtaining a survey from the front desk staff. However, many patients were also recruited via their therapists. Providers were instructed to offer the survey to patients with anxiety disorders, regardless of the focus of treatment, modality of treatment, or comorbidity. Providers were instructed to have patients to complete the surveys privately and without their assistance in the clinic, and to give the surveys back to the providers or the front desk staff in a sealed envelope provided by the researchers. Front desk staff mailed completed surveys back to the research team. Patients were mailed $10 gift cards after the researchers received the surveys.

Results

Provider Survey

Participating Clinics

We obtained general information from clinic administrators about 14 of the 18 agencies with participating providers. Three of these clinics served youth primarily (0–25 years old), but provided treatment to parents of the children they served. Two other clinics served primarily older adults (55+ years old), with the remaining clinics serving either adults age 18 and older, or patients at any age across the lifespan. The number of adult patients treated annually at each clinic ranged from 20 to over 1200. All but two of the clinics that provided information reported that the majority of their patients were racial/ethnic minorities (i.e., ranging from 59%–100%), with 85–100% of patients defined as low-income. The size of DMH contracts across clinics ranged from $400,000 to $10 million.

Participant Professional Characteristics

Details of provider participant professional characteristics are presented in Table 1. The majority of providers had a masters-level clinical degree, were early in their careers, and identified their primary clinical role as therapist of supervisor. Over half of provider participants were unlicensed.

Prior and Ongoing Training

As shown in Table 2a, the majority of participants reported receiving “no training” in any of the types of exposure while earning their clinical degree (ranging from 58.1–78.9%), whereas the range of responses was more varied for cognitive restructuring. When asked about training and supervision while in their current clinical position (Table 2b), a similar pattern of findings was observed, but with somewhat more participants reporting training and supervision in some CBT techniques. The majority of participants (91.9%) received some instruction in cognitive restructuring while employed at their current position. Although a somewhat greater percentage of providers reported receiving ongoing, frequent supervision in in vivo exposure with their patients in their clinic (23.0%) compared to graduate/clinical training program (8.6%), a large percentage (43.7%) still reported no training in in vivo exposure while in their clinical position. Some providers reported using in vivo exposure with patients despite never receiving training or supervision in the technique. Within their current clinical positions, the majority of providers had not received training or supervision in interoceptive exposure (70.1%), the core component of a widely-used and highly efficacious CBT treatment for panic disorder (Barlow & Craske, 2007), and nearly half had not received training or supervision in imaginal exposure (49.4%), the core component of a widely-used, highly efficacious behavioral treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (Foa, Hembree & Rothbaum, 2010) and a frequently-used component of treatment for other anxiety disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder).

Table 2b.

Training and Supervision while in Clinical Position (post-graduate)

| Technique | Training Level/Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| No training or supervision | Workshop | Ongoing, regular supervision while using this technique with patients | Occasional or infrequent supervision while using this technique with patients | Use this technique informally with patients, but no formal training or supervision related to using this technique | |

| Cognitive restructuring | 8.1 | 25.6 | 32.6 | 19.8 | 14.0 |

| In vivo exposure | 43.7 | 12.6 | 23.0 | 12.6 | 8.0 |

| Interoceptive exposure | 70.1 | 11.5 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 2.3 |

| Imaginal exposure | 49.4 | 12.9 | 21.2 | 11.8 | 4.7 |

Key Terms: Cognitive restructuring during CBT for anxiety disorders involves a set of techniques in which the therapist teaches patients to use evidence-based thinking to reappraise threat-laden thoughts about anxiety provoking stimuli and to think more flexibly by generating alternative ways of thinking about the stimuli; In vivo exposure consists of directly (and typically repeatedly and gradually) facing the feared situation; interoceptive exposure consists of inducing physiological sensations of autonomic nervous system arousal (typically repeatedly), and is most commonly used in the treatment of panic disorder; imaginal exposure consists of facing feared stimuli in imagination, typically repeatedly and in the form of “worst case scenario outcomes” (in generalized anxiety disorder treatment), traumatic memories (in posttraumatic stress disorder treatment), or obsessional, unwanted images (in obsessive compulsive disorder treatment). The order and content of exposure activities is traditionally generated by creating a fear hierarchy, which is a list of feared/avoided stimuli that the patient rates on fear or subjective units of distress (SUD).

Treatment Practices with Anxiety Disorders

As shown in Table 3, most providers identified anxiety disorders as an important problem worthy of including in the treatment plan, even when other comorbidity exists. The majority of clinicians reported completely agreeing with statements that they use relaxation, mindfulness, and coping skills training with patients who have anxiety disorders. However, the degree to which other cognitive and behavioral strategies for anxiety disorders are implemented by clinicians varied, with just over one-third of providers reporting that they somewhat agree with statements that they use cognitive restructuring, build fear hierarchies, and assign exposure homework. Few providers “completely” agreed with these statements. Only one-fourth of providers reported somewhat agreeing with the statement that they do in-session exposure of any kind (i.e., in vivo, interoceptive, or imaginal), and few “completely” agreed with the statement.

Table 3.

Practices with Anxiety Disorders (Provider Survey, n = 95)

| Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I include treatment of the anxiety disorder as part of the overall treatment plan. | 2.7 | 2.7 | 6.8 | 19.2 | 68.5 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I make sure the other comorbidity (e.g., psychotic disorder, mood disorder) is addressed first, and then I treat the anxiety disorder. | 6.9 | 20.8 | 30.6 | 31.9 | 9.7 |

| When a patient comes into my office with an anxiety disorder, there are usually more important problems to address (e.g., substance use, depression), and I don’t tend to have time to treat the anxiety. | 25.0 | 40.3 | 19.4 | 13.9 | 1.4 |

| Most of my patients are anxious because they have difficult lives, so I do not consider this to be an important problem to address clinically, other than addressing basic needs such as housing and food to relieve anxiety. | 58.3 | 16.7 | 11.1 | 11.1 | 2.8 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, treatment for the anxiety disorder includes using cognitive strategies such as downward arrow and cognitive restructuring. | 2.8 | 8.3 | 18.1 | 38.9 | 31.9 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I work with the patient to create a fear hierarchy of feared and avoided situations, images, thoughts, or sensations. | 5.6 | 22.2 | 18.1 | 40.3 | 13.9 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I assign homework for the patient to confront avoided situations such as speaking up in a group or riding the bus across town. | 4.2 | 13.9 | 15.3 | 40.3 | 26.4 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I assign homework for the patient to confront other avoided stimuli, such as images of a traumatic memory or the bodily sensation of heart racing or dizziness. | 8.3 | 16.7 | 20.8 | 37.5 | 16.7 |

| When a patient comes to my office with an anxiety disorder, I have the patient face his or her fears in the session, such as by introducing him or herself to others around the office, imagining a traumatic memory, or bringing on sensations of arousal. | 12.7 | 22.5 | 26.8 | 25.4 | 12.7 |

| When I work with a patient with an anxiety disorder, I teach the patient relaxation strategies such as diaphragmatic breathing or progressive muscle relaxation. | 2.9 | 2.9 | 10.0 | 20.0 | 64.3 |

| When I work with a patient with an anxiety disorder, we work on mindfulness and acceptance strategies. | 2.8 | 2.8 | 11.1 | 34.7 | 48.6 |

| When I work with a patient with an anxiety disorder, we work on coping skills, problem solving, and assertiveness. | 2.8 | 0.0 | 12.7 | 22.5 | 62.0 |

| When I work with a patient with an anxiety disorder, we talk about how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors interact. | 2.8 | 2.8 | 18.3 | 18.1 | 68.1 |

| When I work with a patient with an anxiety disorder, I make sure that patient has a consultation for medication management for the anxiety (or I prescribe medication for anxiety, if applicable). | 5.6 | 6.9 | 19.4 | 40.3 | 27.8 |

Barriers to Delivering Evidence-based Treatment for Anxiety Disorders

As shown in Tables 4 and 5, the majority of provider participants did not identify any one barrier to delivering evidence-based treatment for anxiety disorders. Most providers thought exposure and cognitive restructuring were effective for anxiety and that exposure does not do harm to patients. The majority of providers also believed that their patients with anxiety disorders were appropriate candidates for CBT who could attend regular therapy sessions. Most providers reported that the quality and quantity of their supervision was adequate and that their supervisors had the skills necessary to provide supervision in cognitive and behavioral techniques for anxiety disorders. Despite the acceptability of CBT for anxiety disorders in this provider population, as well as the confidence in their supervisors, some barriers were identified. Specifically, approximately one-third of the providers thought that a structured treatment protocol was not practical in their clinical setting, reported discomfort with making their patients anxious during treatment, felt incompetent to deliver exposure, reported receiving inadequate training in exposure, and believed that ongoing crises often got in the way of starting CBT for anxiety disorders.

Table 4.

Perceived Patient- and Provider-Level Barriers to Delivering Evidence-Based Treatment for Anxiety Disorders (Provider Survey, n = 95)

| Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I think there are better ways to treat anxiety than to use cognitive or behavioral (i.e., exposure, or facing fears) strategies. | 11.6 | 37.7 | 29.0 | 20.3 | 1.4 |

| I think exposure is harmful to patients (e.g., re-traumatizes, is mean, makes them worse). | 17.1 | 31.4 | 32.9 | 15.7 | 2.9 |

| I don’t think exposure works for treating anxiety. | 20.0 | 41.4 | 27.1 | 8.6 | 2.9 |

| I don’t think cognitive restructuring works for treating anxiety. | 34.8 | 40.6 | 17.4 | 4.3 | 2.9 |

| It makes me uncomfortable to make my patients anxious on purpose. | 11.6 | 29.0 | 29.0 | 23.2 | 7.2 |

| I do not feel competent to deliver cognitive restructuring. | 30.0 | 37.1 | 15.7 | 12.9 | 4.3 |

| I do not feel competent to deliver exposure therapy. | 17.1 | 28.6 | 12.9 | 25.7 | 15.7 |

| My supervisor does not know how to do cognitive restructuring well enough for me to feel comfortable getting consultation from him or her to use these approaches. | 33.8 | 22.5 | 28.2 | 14.1 | 1.4 |

| My supervisor does not know how to do exposure well enough for me to feel comfortable getting consultation from him or her to use these approaches. | 29.6 | 25.4 | 28.2 | 11.3 | 5.6 |

| I did not receive adequate training to deliver cognitive restructuring for anxiety. | 22.9 | 30.0 | 25.7 | 17.1 | 4.3 |

| I did not receive adequate training to deliver exposure therapy for anxiety. | 19.7 | 15.5 | 25.4 | 28.2 | 11.3 |

| My supervisor knows how to deliver cognitive and behavioral strategies for anxiety, but my supervision is not long or frequent enough for me to get the help I need. | 32.4 | 14.1 | 36.6 | 14.1 | 2.8 |

| We focus on other things during supervision, so there is not enough time for me to get help with these cases. | 31.0 | 29.6 | 25.4 | 12.7 | 1.4 |

| It is too difficult to get my patients into weekly or bi-weekly sessions to do a good course of CBT for anxiety. | 29.6 | 23.9 | 26.8 | 19.7 | 0.0 |

| My patients are unwilling or unable to come in for regular appointments. | 26.8 | 26.8 | 25.4 | 14.1 | 7.0 |

| I have offered cognitive therapy to my patients with anxiety disorders, but they usually refuse. | 32.9 | 37.1 | 22.9 | 5.7 | 1.4 |

| I have offered exposure therapy to my patients with anxiety disorders, but they usually refuse. | 25.4 | 32.4 | 31.0 | 8.5 | 2.8 |

| I have offered cognitive therapy to my patients with anxiety disorders, but they usually stop showing up. | 32.9 | 38.6 | 22.9 | 5.7 | 0.0 |

| I have offered exposure therapy to my patients with anxiety disorders, but they usually stop showing up. | 34.3 | 28.6 | 32.9 | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| I feel like I need to handle my patients’ ongoing crises and this takes priority over starting CBT for anxiety. | 14.1 | 22.5 | 26.8 | 31.0 | 5.6 |

| Most of my patients are too complex or severe to benefit from CBT for their anxiety disorder. | 31.0 | 39.4 | 19.7 | 9.9 | 0.0 |

| Most of my patients are not motivated enough to benefit from CBT for their anxiety disorder. | 21.1 | 38.0 | 26.8 | 14.1 | 0.0 |

| Most of my patients are not functioning well enough to benefit from CBT for their anxiety disorder. | 25.4 | 31.0 | 23.9 | 18.3 | 1.4 |

| My patients have more important things to deal with than their anxiety disorder. | 32.9 | 28.6 | 30.0 | 8.6 | 0.0 |

| My supervisor does not like CBT or thinks other therapies are more helpful for anxiety. | 55.7 | 17.1 | 22.9 | 4.3 | 0.0 |

| A successful anxiety treatment is one in which my patient learns to relax, control anxiety, and avoid anxiety-provoking situations. | 15.5 | 19.7 | 18.3 | 29.6 | 16.9 |

| Most of my patients’ anxiety do not conform to a DSM anxiety disorder, so I’m not sure how I would treat it using CBT. | 42.3 | 26.8 | 26.8 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| It’s hard to know what kind of exposure exercises I could do with my patients, since most of them do not have anxiety that conforms to a typical DSM anxiety disorder. | 39.4 | 28.2 | 26.8 | 5.6 | 0.0 |

| In our clinic, we need to be flexible and deal with a lot of complex issues, so going through a formal manual or structured treatment is not practical. | 21.1 | 18.3 | 29.6 | 25.4 | 5.6 |

| I am not aware of flexible ways to apply cognitive and behavioral strategies to anxiety problems. | 39.4 | 32.4 | 15.5 | 8.5 | 4.2 |

With regard to system- and organizational-level barriers, none of the potential barriers were endorsed by the majority of providers. In fact, most providers strongly disagreed or disagreed with nearly all of the statements, particularly when excluding the participants who stated they did not know or the question was not applicable to them (e.g., the question was geared towards administrators with more general knowledge of organizational culture or funding streams). The primary exception was that, when excluding participants who endorsed “do not know,” over one-third of providers reported that few to none of the staff at their clinic had formal CBT training. In sum, the primary barrier consistently endorsed related to adequacy of CBT training.

Patient Survey

Treatment Received for Anxiety Disorders

As shown in Table 6, patient participants (n = 42) were asked to report the extent to which they had received (or would like to receive) certain types of treatment for their anxiety disorders. Most patients reported receiving most of the techniques listed. Consistent with provider reports, patients reported somewhat less receipt of exposure therapy techniques compared to cognitive restructuring and relaxation techniques, but nonetheless, about half of patient participants reported receiving each exposure-based technique (e.g., creating fear hierarchy, being encouraged to face feared situations, facing bodily sensations of arousal). Also consistent with provider report, patients reported that treating anxiety was considered an important part of their treatment plan.

Patient Preferences and Beliefs about Anxiety Treatment

As shown in Table 7, patients generally were satisfied with therapy but had mixed opinions regarding their acceptability and the perceived efficacy of medication for their anxiety disorders. Although a large percentage of patients stated that the idea of facing their fears to overcome anxiety sounded terrifying, most participants endorsed items reflecting acceptability of exposure. For example, nearly three-quarters of participants stated that a treatment that consists of gradually confronting fears is helpful (or would be helpful, if they were to receive it); and over half of the participants stated that, if offered an effective therapy that required them to face their fears, they would undergo the treatment. Most participants believed that a combination of medication and therapy was better than either treatment alone, though the vast majority of participants thought therapy + medication was better than medication alone, whereas fewer thought therapy + medication was better than therapy alone.

Table 7.

Beliefs and Preferences about Anxiety Treatment (Patient Survey, n = 42)

| Completely disagree | Somewhat disagree | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Completely agree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy working regularly with a therapist on my anxiety. | 2.5 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 45.0 | 47.5 |

| I like taking medication for my anxiety. | 30.0 | 2.5 | 22.5 | 15.0 | 30.0 |

| Therapy has been helpful in managing and reducing my anxiety. | 2.5 | 2.5 | 12.5 | 27.5 | 55.0 |

| Medication has been helpful in managing and reducing my anxiety. | 27.5 | 2.5 | 7.5 | 30.0 | 32.5 |

| I prefer therapy that is open-ended and allows me to talk about my problems and feelings. | 2.5 | 2.5 | 22.5 | 27.5 | 45.00 |

| I prefer therapy with specific goals in which I learn strategies and skills for managing my anxiety. | 2.6 | 2.6 | 15.4 | 28.2 | 51.3 |

| I like (or would like) a therapy that teaches me new ways of thinking in anxious situations. | 2.6 | 0.0 | 12.8 | 33.3 | 51.3 |

| I think therapy that teaches me new ways of thinking in anxious situations has been helpful (or would be helpful, if I were to receive it). | 2.6 | 0.0 | 7.7 | 43.6 | 46.2 |

| I think therapy that helps me gradually confront the things I’m afraid of to learn something new about those things is helpful (or would be helpful, if I were to receive it). | 2.6 | 7.7 | 20.5 | 30.8 | 38.5 |

| I think therapy that helps me gradually confront the things I’m afraid of sounds terrifying. | 12.8 | 12.8 | 17.9 | 35.9 | 20.5 |

| If my therapist offered me an effective treatment that required me to face my fears, I would not want to do it. | 33.3 | 17.9 | 28.2 | 10.3 | 10.3 |

| Anxiety is harmful. | 20.5 | 10.3 | 15.4 | 28.2 | 25.6 |

| I think the combination of therapy and medication is better than therapy alone. | 12.8 | 7.7 | 17.9 | 23.1 | 38.5 |

| I think the combination of therapy and medication is better than medication alone. | 7.7 | 2.6 | 5.1 | 25.6 | 59.0 |

| I think my anxiety gets better the more I practice what I learn with my therapist in my daily life. | 5.1 | 0.0 | 15.4 | 28.2 | 51.3 |

| My therapist has offered to teach me new thinking skills. | 2.6 | 5.1 | 2.6 | 33.3 | 56.4 |

| My therapist has offered to teach me new thinking skills to improve my anxiety but I declined. | 46.2 | 20.5 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 7.7 |

| My therapist has offered to help me gradually face the things I avoid because of my fear and anxiety (like thoughts, images, situations, body sensations, and memories). | 2.6 | 12.8 | 15.4 | 38.5 | 30.8 |

| My therapist has offered to help me gradually face the things I avoid and that I’m afraid of (like thoughts, images, situations, body sensations, and memories), but I declined. | 41.0 | 7.7 | 12.8 | 25.6 | 12.8 |

| I started learning specific skills or facing my fears with my therapist to reduce my anxiety but I stopped coming in regularly for therapy. | 64.1 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 5.1 |

| I started therapy that did not include learning specific skills or facing my fears to reduce my anxiety, and I stopped coming in regularly. | 66.7 | 15.4 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 0.0 |

| Anxiety is the least of my problems – when I meet with my therapist, we have more important issues to discuss. | 46.2 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 15.4 | 7.7 |

Patients’ Perceived Barriers to Receiving Care

Consistent with provider report (see Table 8), most patients did not report that environmental (e.g., transportation) or system-level (e.g., difficulty getting appointments) barriers prevented them from receiving regular treatment for their anxiety. Similarly, patients generally reported that provider-related issues (e.g., difficulty understanding my therapist) did not get in the way of receiving treatment for anxiety. Although none of the potential barriers were endorsed as getting in the way “quite a bit” or “completely” by most participants, the two potential barriers that were endorsed at these levels somewhat more frequently related to the patients’ own symptoms. That is, approximately one-quarter of participants reported that their own fears of facing avoided situations in therapy got in the way of attending sessions, and approximately one-third of participants reported that the consequences of their depression (i.e., withdrawal and difficulty leaving the home) got in the way of attending sessions to treat their anxiety disorder. In sum, few barriers to care were identified by participants, but the most highly endorsed were those relating to their own symptoms getting in the way of receiving regular treatment.

Discussion

This study was the first to our knowledge to gather comprehensive data from patients, providers, and administrators at adult community mental health settings across diverse settings and populations in order to better understand perceived barriers to delivering (and receiving) evidence-based psychosocial treatment for anxiety disorders. Each stakeholder group offered insights relevant to their unique role in the implementation system. Issues related to provider training and competence in exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders stood out as the most prominent barriers, and the relatively low prevalence of providers and patients endorsing that cognitive or behavioral skills (particularly exposure) were used in therapy sessions is likely to reflect, at least in part, insufficient training or skill in these strategies.

Patients and providers found CBT for anxiety to be acceptable. Providers had positive beliefs about the safety and efficacy of cognitive and behavioral strategies for treating anxiety disorders, including exposure strategies. Possibly, increased knowledge and awareness of CBT for anxiety disorders and EBPs generally among community providers has led to these positive attitudes, though additional research is needed. Similarly, patients liked (or thought they would like) to work with their therapists using these strategies, including exposure to feared stimuli. These findings challenge the conventional wisdom that patients and providers are resistant to exposure, and add to the growing body of literature demonstrating that patients and providers find exposure highly acceptable once they learn about it (Arch et al,., 2015). This preliminary finding is promising in that those with more positive beliefs about exposure-based therapy have been shown to more optimally delivery it (Farrell, Deacon, Kemp, Dixon & Sy, 2013; Deacon, Lickel, Farrell,, Kemp, & Hipol, 2013) and to be less likely to inappropriately exclude anxious patients from exposure-based treatment (Mayer, Farrell, Kemp, Blakey & Deacon, 2014).

Another finding that was discrepant from the initial themes that emerged from the qualitative data (see Wolitzky-Taylor et al., under review) was that external/environmental patient-level factors (e.g., childcare, transportation) were not frequently endorsed as barriers by the patients themselves or the providers. These findings are also discrepant from prior studies examining barriers to EBP delivery in community-based settings for children (Reardon et al., 2017). Most work examining barriers to treatment delivery has gathered insights from administrators and providers. Our findings suggest that there may be value in asking patients directly what may (or may not) prevent them from attending sessions regularly. Possibly, providers and administrators may be making assumptions about why their patients are not regularly attending sessions; or providers may not offer therapies requiring regular ongoing sessions (e.g., CBT) because they assume that these environmental barriers will arise for patients. Patients may benefit from their providers assessing for these potential barriers directly before developing a treatment plan. On the other hand, the particular patients who agreed to participate in this study could have been more motivated than the average patient to engage with mental health care. Future studies could employ random patient sampling to ascertain the extent to which the current findings generalize to community mental health patients broadly.

Despite these encouraging findings, system-, organizational-, and provider-level characteristics related to training emerged as the most prominent barriers to enacting exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders, consistent with the qualitative focus group and interview data (see Wolitzky-Taylor et al, under review). Provider surveys revealed that only a minority of providers received ongoing training and supervision in most CBT skills, with particularly low levels of training or supervision in exposure. These findings are consistent with prior work showing that only a small proportion of the mental health workforce is trained to deliver CBT (Institute of Medicine, 2015; Weissman et al., 2006). Accordingly, many providers reported not receiving adequate training to conduct exposure, feeling incompetent to deliver exposure, and discomfort with making their patients anxious during treatment. Discomfort about inducing anxiety during exposure is likely to be the effect of low self-efficacy (and skill) in delivering exposure, which typically comes with training and supervised experience. A recent study demonstrates that clinician attitudes toward exposure, such as discomfort in making patients (temporarily) anxious during treatment, significantly shift following exposure training that explicitly target such attitudes (Farrell, Kemp, Blakey, Meyer & Deacon, 2016).

Consistent with these provider- and organizational-level barriers related to exposure-based CBT training, the most frequently endorsed system-level barrier was the lack of funding to provide such training to new clinicians joining the clinical staff. This barrier also emerged in our qualitative analyses and may represent the most challenging to overcome. Even with well-intentioned staff at community mental health centers who aim to employ evidence-based treatments for anxiety disorders, patients who seem willing and able to attend these therapy sessions, and a highly effective treatment for providers to learn, lessening the burden of anxiety disorders ultimately depends on government (or other) funds to support the ongoing training and supervision of clinical staff to deliver CBT treatments. The MHSA provided financial resources for training providers in a variety of EBPs in California at a specific cross-section in time, and clinics benefitted from those training funds during that period. However, training in exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders appears to have been excluded from the funded training curriculum, despite the fact that the organizational cultures of clinics surveyed here appeared to prioritize and acknowledge the importance of treating anxiety disorder. Consequently, providers used and seemed most experienced with general CBT skills such as relaxation or cognitive restructuring, but had little training and experience in delivering exposure, likely the most active ingredient in CBT for anxiety disorders (i.e., exposure; Glenn, Golinelli, Rose et al., 2013; Longmore & Worrell, 2007). Previous work treating anxiety disorders in primary care settings has shown that greater reliance on cognitive coping strategies (such as cognitive restructuring) led to worse outcomes (Craske et al., 2006). Further, given very high staff turnover in community mental health settings (Woltmann et al., 2008) the widespread uptake of these interventions may not be sustainable without continued resource allocation for ongoing training efforts. Clearly, policies are needed to ensure ongoing funding for training and continued supervision to ensure that as new providers enter the workforce, they are provided with the opportunities to learn the most effective therapies for treating anxiety disorders, as well as offered the supervision needed to develop as skilled practitioners in this area.

Recommendations and Future Directions

As one of the most effective treatments for any class of mental disorder, exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders should be advocated as a funding priority for training and supervision in community settings. Researchers have shown that exposure-based CBT can be successfully implemented in community settings that treat anxious children (Weisz et al., 2012) and U.S. military veterans with PTSD (McLean & Foa, 2013); however, efforts to systematically roll out these treatments in publicly funded community mental health settings for (non-veteran) adults, who represent the majority of people with anxiety disorders, are lacking. Given the high prevalence of anxiety disorders (Kessler et al., 2005), their documented effects on daily impairment and quality of life (Olatunji, Cisler & Tolin, 2004; Mendlowisz & Stein, 2000), clear preference from previous and current study data of patient preference for therapy over medication to treat anxiety (McHugh, Whitton, Pechham, Welge & Otto, 2013), and current findings demonstrating that across stakeholder levels, anxiety disorders are viewed as burdensome and important to treat, this effort is vital.

From the taxpayer’s perspective, this effort is also urgent. Disseminating the most strongly supported evidence-based treatments for anxiety disorders stands to save time and money for patients, providers, and organization. For example, the most common therapy strategy endorsed by current providers was relaxation, which has been shown to serve a superfluous role within CBT for anxiety disorders (Schmidt & Woolaway-Bickel, 2000; Deacon et al., 2012). As noted, the most common core CBT strategy endorsed by current providers for anxiety was cognitive restructuring, which has been shown to be associated with worse outcomes when employed more often within a treatment effectiveness study for panic disorder (Craske et al., 2006). And nearly half of current providers agreed with the statement that “a successful anxiety treatment is one in which my patient learns to….avoid anxiety-provoking situations”. This statement represents the precise opposite goal or process of exposure therapy. Generally, reinforcing behavioral avoidance would be hypothesized to lead to worse functional outcomes for anxiety disorder patients – reinforcing the very avoidance that signifies a core causal and maintenance factor for anxiety disorders (Barlow, 2002; Craske, 1999).

Importantly, we fully believe that providers are doing the best job they can with the training they have. Rather, we note that despite generally positive attitudes toward exposure therapy, current providers simultaneously hold views that are incompatible with regard to implementing exposure. Fortunately, recent work demonstrates that exposure training that directly targets such views is successful at modifying them (Farrell et al., 2016). Given the diverse forms of training and beliefs about the value of avoidance endorsed by many current providers, we recommend that exposure training efforts directly address misconceptions about exposure, reinforced by testimonials from successfully treated patients, prior to teaching exposure strategies.

Recent work (Gallo, Comer, Barlow, Clarke & Antony, 2015) also highlights the promise of a frequently overlooked pathway to promoting EBPs, including exposure-based CBT, to adults treated in the community – direct-to-consumer marketing. Building on the extraordinary success of direct-to-consumer marketing in promoting pharmaceuticals, nascent work has begun to ascertain the effect of directly promoting psychotherapy to potential consumers (Gallo et al, 2015). Clearly, psychotherapy lacks the corporate money or backing that characterizes much of the pharmaceutical industry. Yet promoting exposure-based CBT for anxiety disorders in clinic marketing materials online and onsite (e.g., “Ask your therapist about CBT for anxiety disorders – a scientifically proven treatment”) could grow demand for the treatment from patients themselves. This is turn could help to justify sustaining the system funding to train and supervise providers in the treatment. As a caveat, our recommendations should be considered preliminary and supported by future research with larger samples that replicates these findings.

Study Limitations

This study represents the first to bring together multiple stakeholders – patient, provider, and administrator – to explore barriers to the implementation of exposure-based CBT for the treatment of anxiety disorders in adult community mental health settings. That stated, there are limitations worth noting. First, the current sample reflects a convenience sample; further studies would benefit from random sampling (if possible) as well as larger samples. The majority of agencies we contacted for participation did not respond to the invitation and the study could not provide funds directly to participating agencies to help incentivize their participation. Given the busy schedules of many stakeholders, future studies would benefit from using reasonable incentives to increase participation. Additionally, we do not know how many providers across all of the participating agencies received the email about the surveys, and thus do not know what the participation rate was for providers. It is possible that those providers who self-selected to participate may differ in some ways from those who did not participate. Still, the number of agencies in which at least one provider responded is large, increasing generalizability. Similarly, the patient sample may be biased in favor of positive reports of therapy experiences and fewer environmental barriers to attending sessions, as these surveys were done via hardcopy in clinics. Thus, these patients represent those who are seemingly willing and able to attend at least some sessions, are interested in participating in a survey to improve care, and therefore may not be representative of the larger population of those seeking treatment at publicly funded community mental health centers. Relatedly, there could be potential biases in patient reports since staff at their clinic gave them the surveys, though we attempted to minimize this bias by ensuring that clinic staff left the room while participants completed the surveys and only collected them after they were placed in sealed envelopes by the patients.

Second, the sample size was relatively small. Given the large number of clinics and agencies from which the provider participants were recruited, our sample size was insufficient to nest within clinics or to investigate differences among organizations. Future research with larger samples should explore whether beliefs about treatment barriers are clustered within organizations, and what characteristics of organizations are associated with better (or worse) uptake of exposure-based CBT for adult anxiety disorders (Glisson et al., 2010). Research suggests that interventions that target organization-level service barriers can result in better outcomes when paired with an EBT than when the EBT is implemented alone, suggesting that organizational characteristics play a large role in EBT adoption and effective use. Relatedly, different professionals (e.g., social workers v. psychologists v. psychiatrists) may report different barriers, but larger sample sizes are needed to identify potential differences across professional groups. Similarly, our patient sample was obtained only from four out of the many clinics whose providers participated; therefore, we were unable to compare provider and patient responses within organizations, an important question deserving of future research with larger samples.

Third, it is unclear whether these findings will generalize to other counties within California or to other states. Our work uncovered how the idiosyncrasies within each clinic, agency, and county impacted the uptake of CBT for anxiety disorders. These idiosyncrasies are likely to exist across and within service systems more broadly, and thus call for future research to examine whether these initial findings replicate, as well as highlight the potential need to tailor solutions for specific organizations and systems. For example, although we obtained provider/administrator data from both urban and rural service areas, the patient sample was comprised of clinics from urban areas in Los Angeles County. Research on patient beliefs and preferences would be important to conduct in rural service areas as well. Finally, because this study did not include medical record data, we lacked information about the patient participants’ diagnoses, length of treatment, or other relevant clinical characteristics. Larger samples that also collect these clinical data systematically may be able to shed light on whether there are particular patterns of responses that emerge within subgroups (e.g., specific anxiety disorders, those with depression or substance use comorbidity).

Summary and Conclusion

Positive attitudes, beliefs, and preferences across stakeholder groups for treating anxiety disorders using CBT, coupled with few patient- and organizational-level barriers, point toward a willingness for exposure-based CBT to be utilized more widely in adult community mental health settings. However, the lack of trained providers and funds to support training in CBT for anxiety disorders currently hinders these organizations’ ability to provide the best care for adults with anxiety disorders treated in community mental health settings. Advocacy efforts at multiple stakeholder levels are now needed to promote access to one of the most efficacious psychosocial treatments developed to date.

Footnotes

This study was conducted in line with ethical guidelines for the conduct of human subjects research. It was approved by the Institutional Review Board. The authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

The decision to conduct patient focus groups at only two of the four clinics was purely practical. The funding for the qualitative and quantitative portions of the project was for one year, and recruiting patient participants required close logistical collaboration with the community partners. We chose the two clinics in which we believed timely recruitment would be most feasible.

References

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, Horwitz SM. Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38(1):4–23. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Palinkas LA. Implementation of evidence-based practice in child welfare: Service provider perspectives. Administration and policy in mental health and mental health services research. 2007;34(4):411–419. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akin BA, Mariscal SE, Bass L, McArthur VB, Bhattarai J, Bruns K. Implementation of an evidence-based intervention to reduce long-term foster care: Practitioner perceptions of key challenges and supports. Children and Youth Services Review. 2014;46:285–293. [Google Scholar]

- Arch JJ, Twohig MP, Deacon BJ, Landy LN, Bluett EJ. The credibility of exposure therapy: Does the theoretical rationale matter? Behaviour research and therapy. 2015;72:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH, Craske MG. Mastery of your anxiety and panic. Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. Guilford press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager CF, Chorpita BF, Higa-McMillan C, Weisz JR. Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(5):677–681. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Century J, Cassata A, Rudnick M, Freeman C. Measuring enactment of innovations and the factors that affect implementation and sustainability: Moving toward common language and shared conceptual understanding. The journal of behavioral health services & research. 2012;39(4):343–361. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG. Anxiety disorders: Psychological approaches to theory and treatment. Basic Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Craske MG, Roy-Byrne P, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Hazlett-Stevens H, Bystritsky A, Sherbourne C. CBT intensity and outcome for panic disorder in a primary care setting. Behavior Therapy. 2006;37(2):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation science. 2009;4(1):50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ, Abramowitz JS. Cognitive and behavioral treatments for anxiety disorders: A review of meta-analytic findings. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60(4):429–441. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon B, Lickel J, Abramowitz JS. Medical utilization across the anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2008;22(2):344–350. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ, Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, Dixon LJ, Sy JT, Zhang AR, McGrath PB. Assessing therapist reservations about exposure therapy for anxiety disorders: The Therapist Beliefs about Exposure Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(8):772–780. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ, Lickel JJ, Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, Hipol LJ. Therapist perceptions and delivery of interoceptive exposure for panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(2):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon BJ, Lickel JJ, Possis EA, Abramowitz JS, Mahaffey BG, Wolitzky-Taylor K. Do cognitive reappraisal and diaphragmatic breathing augment interoceptive exposure for anxiety sensitivity? Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2012;26(3):257–269. [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 2000;15(8):527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Lagomasino IT, Hay J, Zhang L, Tang L, Green JM, Duan N. Effectiveness of collaborative care in addressing depression treatment preferences among low-income Latinos. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61(11):1112–1118. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.11.1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell NR, Deacon BJ, Dixon LJ, Lickel JJ. Theory-based training strategies for modifying practitioner concerns about exposure therapy. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(8):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell NR, Deacon BJ, Kemp JJ, Dixon LJ, Sy JT. Do negative beliefs about exposure therapy cause its suboptimal delivery? An experimental investigation. Journal of anxiety disorders. 2013;27(8):763–771. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, Blakey SM, Meyer JM, Deacon BJ. Targeting clinician concerns about exposure therapy: A pilot study comparing standard vs. enhanced training. Behaviour research and therapy. 2016;85:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Treatments that work. Prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD: Emotional processing of traumatic experiences: Therapist guide 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KP, Comer JS, Barlow DH. Direct-to-consumer marketing of psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(8):793–801. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KP, Comer JS, Barlow DH, Clarke RN, Antony MM. Direct-to-consumer marketing of psychological treatments: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2015;83(5):994. doi: 10.1037/a0039470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn D, Golinelli D, Rose RD, Roy-Byrne P, Stein MB, Sullivan G, … Craske MG. Who gets the most out of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders? The role of treatment dose and patient engagement. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2013;81(4):639. doi: 10.1037/a0033403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstron KS, Chapman JE. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Green P. Organizational climate, services, and outcomes in child welfare systems. Child abuse & neglect. 2011;35(8):582–591. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez ML, Butler AS, England MJ, editors. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray M, Joy E, Plath D, Webb SA. Implementing evidence-based practice: A review of the empirical research literature. Research on Social Work Practice. 2013;23(2):157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Sisitsky T, Kessler RC, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Davidson JR, Ballenger JC, Fyer AJ. The economic burden of anxiety disorders in the 1990s. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:427–435. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herschell AD, Kolko DJ, Baumann BL, Davis AC. The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical psychology review. 2010;30(4):448–466. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higa-McMillan CK, Nakamura BJ, Morris A, Jackson DS, Slavin L. Predictors of use of evidence-based practices for children and adolescents in usual care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2015;42(4):373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0578-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Demler O, Frank RG, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Walters EE, … Zaslavsky AM. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders, 1990 to 2003. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352(24):2515–2523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa043266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore RJ, Worrell M. Do we need to challenge thoughts in cognitive behavior therapy? Clinical psychology review. 2007;27(2):173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, Welge JA, Otto MW. Patient preference for psychological vs. pharmacological treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. The Journal of clinical psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean CP, Foa EB. Dissemination and implementation of prolonged exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of anxiety disorders. 2013;27(8):788–792. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendlowicz MV, Stein MB. Quality of life in individuals with anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):669–682. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mental Health Services Act. State of California; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JM, Farrell NR, Kemp JJ, Blakey SM, Deacon BJ. Why do clinicians exclude anxious clients from exposure therapy? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2014;54:49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Deacon BJ. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2010;33(3):557–577. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Tolin DF. Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2007;27(5):572–581. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, Gillihan SJ, Foa EB. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical psychology review. 2010;30(6):635–641. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon T, Harvey K, Baranowska M, O’Brien D, Smith L, Creswell C. What do parents perceive are the barriers and facilitators to accessing psychological treatment for mental health problems in children and adolescents? A systematic review of qualitative and quantitative studies. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00787-016-0930-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]