Abstract

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication after arthroplasty, which is associated with pain, prolonged hospital stay, multiple surgeries, functional incapacitation, and even mortality. Using scientific and efficient management protocol including modern diagnosis and treatment of PJI and eradication of infection is possible in a high percentage of affected patients. In this article, we review the current knowledge in epidemiology, classification, pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of PJI.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, Joint prosthesis, Implants, Infection

INTRODUCTION

Arthroplasty can fail because of aseptic loosening, instability, periprosthetic fracture or infection of the prosthesis. In general, the incidence of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is lower than aseptic loosening1), but it is more serious and complex complication following arthroplasty. The haematogenous seeding could happen at any time during the rest of patient's life after surgery. For doctor, the treatment and diagnose PJI are still challenging in the modern world. The implant as a foreign body increases the pathogenicity of bacteria and the presence of biofilm makes the diagnosis and treatment complex and difficult. Therefore, appropriate management protocol of PJI should be established, in a timely manner to take preventive measure and diagnosis, and accordant strictly with the results of culture and antimicrobial susceptibility test, to avoid the increase in the rate of bacterial resistance and select reasonably antibiotics combined with adequate operation procedure. Eventually, it achieves eradicating of infection, preserving joint function without any pain.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The joint arthroplasty is a safe and cost-effective surgical technique. It can alleviate symptoms, recover functions and enhance quality of life, especially in the elderly population2,3). With the increment of the joint prosthetic replacements, the number of postoperative complications has also increased. The infection rate after hip or shoulder replacement is usually less than 1%, after knee replacement less than 2% and after elbow replacement is between 1.9% and 10.3%. The reason for higher incidence in elbow region may be related to the more frequent rheumatic disorder, trauma or multiple reconstructive procedures compared to hip and knee surgery4,5).

PJI also increases the medical costs, which are up to 24 times higher than without PJI6), the major cost of PJI is generated by prolonged hospitalization, multiple surgeries and prostheses, and medical supplies7).

Coagulase-negative staphylococci and Staphylococcus aureus are the most common microorganisms in hip and knee PJI8). Furthermore some pathogenic bacteria depend on different body regions, such as Propionibacterium acnes after shoulder replacement and gram-negative bacteria after hip arthroplasty9).

PATHOGENESIS AND CLASSIFICATION

Development stages of the biofilm formation are divided into 4 phases; namely adhesion, proliferation, biofilm maturation and cellular detachment10). The bacterium adheres to the foreign body material that is the first step which can cause biofilm-related infections. The materials of orthopedic implant (such as titanium, ceramics, hydroxyapatite, and polyethylene) is easy for the bacteria to colonize on. Biofilms is a complex community of microorganisms embedded in an extracellular matrix that forms on surfaces of prosthesis.

The prosthesis can get infected by three pathways: first, perioperative period, most commonly through intraoperative inoculation; second, haematogenous could happen at any time after implantation, pathogen from different parts, e.g. respiratory or urinary tract infection, skin infection and pneumonia; and third, direct contact with a nearby infected, e.g. infected soft tissue, septic arthritis or osteomyelitis11). Table 1 shows the classification of PJI into acute and chronic infection. The early (immature) biofilm can be eradicated without remove prosthesis. If symptoms persist less than 3 weeks (hematogenous) or infection manifests less than 4 weeks after surgery (perioperative). Other procedures is defined as chronic PJI, the implant must be changed due to mature biofilm.

Table 1. Classification of Periprosthetic Joint Infection (PJI) into Acute and Chronic Infection.

| Type of PJI | Acute PJI | Chronic PJI |

|---|---|---|

| Pathogenesis | ||

| - Perioperative origin | Early postoperative | Delayed postoperative (low-grade) |

| <4 weeks after surgery | ≥4 weeks after surgery | |

| - Hematogenous origin | <3 weeks of symptoms | ≥3 weeks of symptoms |

| Biofilm age (maturity) | Immature | Mature |

| Clinical features | Acute joint pain, fever, red/swollen joint | Chronic pain, loosening of the prosthesis, sinus tract (fistula) |

| Causative microorganism | High-virulent: Staphylococcus aureus, gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) | Low-virulent: Coagulase-negative staphylococci (e.g. Staphylococcus epidermidis), Propionibacterium acnes |

| Surgical treatment | Débridement & retention of prosthesis (change of mobile parts) | Complete removal of prosthesis (exchange in one-, two-, or multiple stages) |

DIAGNOSIS

Early diagnosis is a positive factor to save the prosthesis and the joint function. No single indicator of a test using in clinic or in laboratory can hand out ideal sensitivity and specificity aiming to the diagnosis of PJI12), so a mixture of multiple tests can reasonably increase the diagnostic accuracy. Some criteria from the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS), European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) have been recently published13,14,15). The EBJIS criteria are more sensitive for the diagnosis of PJI than other criteria (Table 2)16).

Table 2. Definition of Periprosthetic Joint Infection, if at least one of the following 4 criteria is fulfilled.

| Diagnostic test | Criteria | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical features | Sinus tract or visible purulence* | 20–30 | 100 |

| Histology in periprosthetic tissue | Acute inflammation in periprosthetic tissue† | 95–98 | 95–98 |

| Leukocyte count in synovial fluid‡ | >2,000/μL leukocytes or >70% granulocytes | 93–96 | 93–96 |

| Microbiology (culture) | Synovial fluid or Tissue samples§or Sonication fluid (≥50 CFU/mL)‖ | 60–80 | 97 |

| 70-85 | 92 | ||

| 85–95 | 95 |

*Metal-on-metal bearing components can simulate pus, but leukocyte count is usually normal, but metal debris visible.

†Acute inflammation defined as ≥2 granulocytes per high-power field.

‡Leukocyte cutoffs are not interpretable within 6 weeks of surgery, in rheumatic joint disease, periprosthetic fracture or luxation. Leukocyte count should be determined within 24 hours; clotted specimens are treated with 10µL hyaluronidase.

§For highly virulent organisms (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli) already one positive sample confirms infection.

‖Under antibiotics and for anaerobes, <50 colony-forming unit (CFU)/mL can be significant.

1. Laboratory Studies

If PJI is suspected, serum C-reactive protein (CRP) is usually performed17). This marker is inexpensive, rapid and has a better performance than erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). However, CRP is not specific for infection and usually increases due to healing process after intervention. Pérez-Prieto et al.18) found that with normal CRP about one-third of chronic, low-grade infections would be missed. So the combination of CRP and ESR is used for diagnose PJI19,20), the sensitivity of combined ESR (>30 mm/hr) and CRP (>10 mg/L) was 96%, but low specificity 56%21).

Synovial fluid aspiration and culture are the most accurate preoperative examination for the diagnosis of PJI17). Synovial fluid leukocyte count and granulocyte percentage can accurately distinguish PJI from aseptic failure22), and has a sensitivity of 86% compared with synovial fluid culture (52%)23). The patient with rheumatoid arthritis, periprosthetic fracture or dislocation and in the early postoperative period should be excluded, because the cell count shows falsely high11,16,21,22,24).

2. Histopathological Studies

Histopathological examination has a high sensitivity (95%) and specificity (92%) for the diagnosis of PJI. Based on histomorphological criteria, four types of periprosthetic membranes have been defined, wear particle-induced, infectious, combined and indeterminate type25). Nevertheless, the nature and degree of infiltration with inflammatory cells may vary markedly among specimens and even within individual tissue sections from the same patient. There is no comprehensively accepted definition about acute inflammation; normally an acute inflammation has been variably defined as from ≥1 to ≥10 neutrophils per high-power field at a magnification of 40012). Unfortunately, though histopathological test has high value in diagnose PJI, it does not identify the causative bacteria. The CD15 focus score values can differentiate low-virulence and high-virulence microbes with high accuracy26).

3. Microbiological Studies

1) Preoperative aspiration

The synovial fluid culture has a sensitivity ranging from 50% to 70% and should be performed before revision surgeries (together with the determination of leukocyte count in the synovial fluid).

2) Intraoperative specimens

Intraoperative tissue samples provide accurate specimens for detecting the infecting microorganism(s), sensitivity ranging from 45% to 78%, and specificity from 91% to 96%23,25,27). At least three to five intraoperative tissue samples from different anatomical sites should be sampled for culture. Samples should always be collected from a zone in which the tissue structure is visibly inflamed, because it is informative. Prior to collecting microbiological samples, any antibiotic regimen should be discontinued for 2 weeks to progress the disease28).

3) Sonication for removed implant

Sonication is used for dislodging adherent microorganisms from the surface of prosthetic joint. The sonication fluid culture proves the higher sensitivity and specificity than periprosthetic tissue culture which is also valid at the patient who has received antibiotic treatment before surgery. Discontinued antibiotic therapy within 14 days will have higher sensitivity27). A study29) about inoculation of sonication fluid in blood culture bottles (BCB) greatly improves the result, even when the patients received antibiotics. The sonication fluid in BCB has 100% sensitivity and specificity, even the half of patients received antibiotics within 14 days. But the sensitivity is 87% for conventional synovial fluid culture and 59% in tissue culture. The sonication fluid in BCB also reduces the culture time; it detects all bacteria in only 5 days. Another study demonstrated that the sonication fluid in BCB has better sensitivity than agar plate culture and also reduces the culture time than agar plate30). But why sonication fluid in BCB increases the sensitivity is still unclear. The method of sonication fluid in BCB still need more clinic practice to find some details about this research.

4. Imaging Studies

Conventional radiography is the most used in the first-step imaging diagnosis of PJI17). However, the sensitivity and specificity of X-ray plain film in the diagnosis of infection are low, and it is difficult to distinguish between aseptic loosening and PJI31). Computed tomography (CT) imaging occupies good contrast resolution of bone and surrounding soft tissue. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used safely on patients with non-ferrimagnetic implants. MRI displays greater resolution for soft tissue abnormalities than CT and radiography and does not involve radiation. However, the patients must remain in an enclosed machine, which may be extremely problematic for claustrophobic patients. The main disadvantage of CT and MRI is imaging interference in the vicinity of metallic orthopedic implants. Fluorine 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) is a fast, safety, high-quality imaging for detection of PJI32). One meta-analysis report33) pooled sensitivity and specificity of FDG-PET for the diagnosis of prosthetic hip or knee joint infection were 82.1% and 86.6%.

5. New Diagnostic Methods

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques can identify an isolated bacterium and some difficult-to-cultured bacteria. When the patient receives antibiotics, the sensitivity and specificity are still high by multiplex PCR for diagnosis PJI and to distinguish aseptic loosening34). According to a meta-analysis of 14 studies35), the sensitivity and specificity of PCR in synovial fluid samples were 84% and 89% and the PCR in sonication fluid culture were 81% and 96% for the detection of PJI. The sensitivity in fresh samples was better than using frozen samples.

The alpha defensin lateral flow (ADLF) is a rapid biomarker for test PJI, but the sensitivity and specificity are a controversial idea36,37,38). In a recent study16), the ADLF test was detected PJI with sensitivity and specificity in the criteria of MSIS 84.4% and 96.4%, IDSA 67.3% and 95.5%, and EBJIS 54.4% and 99.3%. The EBJIS criteria used for ADLF test are not a good screening diagnose to rule out the PJI, while it could be a good method to confirm PJI.

Microcalorimetry is able to be used to rapidly detect the existence of microorganisms through measuring microbial heat produced by microbial growth and metabolism. A study reports that in microcalorimetry of sonication fluid the sensitivity is 100% and specificity is 97%39).

TREATMENT

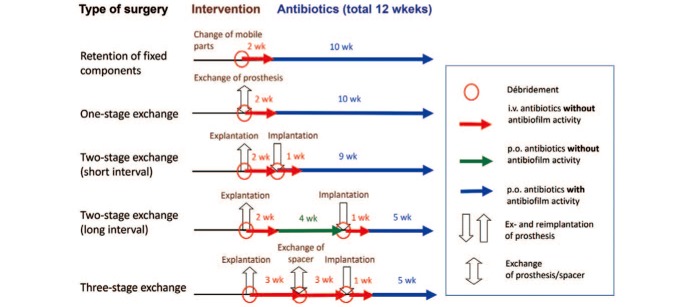

The goals of PJI treatment are to alleviate suffering, restore the normal joint function and eliminate the infection. Treatment decisions should be individualized, and involve a cooperation of a multi-disciplinary team in order to tender the best approach for each patient based on a critical review of the current information. An appropriate operation combining with antimicrobial concept is required for successful treatment. The existing recommendations for treatment of the PJI4,40) have been refined further by new scientific evidences and clinical experiences, as optimized and summarized in a surgical and antibiotic treatment algorithm in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Treatment algorithm of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI).

1. Surgical Therapy

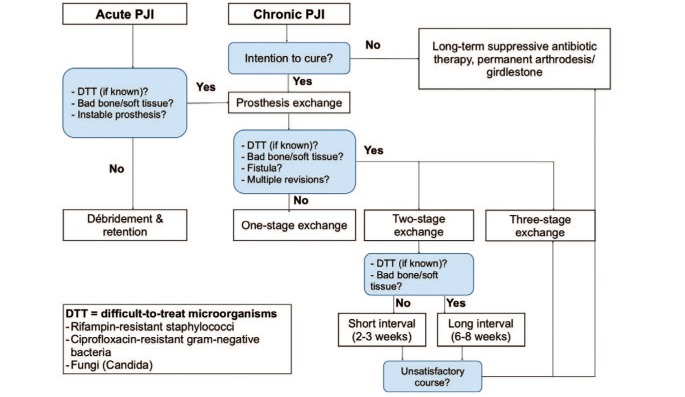

Major surgical strategy for the treatment of PJI includes; débridement and implant retention, one-stage or two-stage implant replacement (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Surgical treatment of periprosthetic joint infection (PJI).

wk: week; i.v.: intravenously; p.o.: per oral.

1) Débridement with retention

Early studies of débridement combining with retention strategies to treat prosthetic joint infection have high failure rates41). However, success rates can be greater than 80% when the following conditions are met42): (1) prosthesis is stable; (2) a pathogen with susceptibility to antimicrobial agents is active against surface-adhering microorganisms; (3) there is no sinus tract or compromised soft tissue; (4) symptom duration of infection is less than 3 weeks. Based on a recent report43), 90% of orthopedic device-related infections are successfully cured by surgical débridement and implant-retention plus antimicrobial therapy according to a predefined treatment algorithm, if patients fulfill the above selection criteria and the pathogen is susceptible to rifampin (for gram-positive pathogens) or ciprofloxacin (for gram-negative pathogens).

2) One-stage implant replacement

One-stage exchange is a single operation, which includes the removal of the old and reimplantation of a new prosthesis. The operation is mostly used in Europe, whereas two-stage replacement is often used in United States5,13). One-stage exchange is suitable for patients who have good bone conditions and soft tissue without sinus tract, as well as known bacteria with no difficult-to-treat (DTT) infections caused by pathogens resistant to biofilm-active antimicrobials42). If based on the indication, the success rate of one-stage exchange could be reach 100%44). In a single center report45), the success rate of one-stage replacement is from 85% to 90% over 35 years. The one-stage exchange is an effective surgery with high success rate, earlier mobility, shorter period of hospitalization and less cost than two-stage exchange.

3) Two-stage implant replacement

It includes removal of the prosthesis and subsequently delayed reimplantation of a second prosthesis. The approach of short interval (2–4 weeks) is suitable for patients who have known and easily treatable organism, compromised soft tissue or sinus tract. The approach of long interval (8 weeks) is suitable for the organism which is unknown or DTT and strongly compromised soft tissue. Two-stage exchange is identified as a golden standard to treat the patients13), especially in DTT microorganisms such as enterococci or fungi, etc. The success rate of two stage usually >90%4), but the reinfection is important and easy to be ignored question, and the incidence of reinfection in one and two stage according to a meta-analysis shows 8.2% versus 7.9% (95% confidence intervals)46). If more than three morbidities and a high ESR or CRP is present before reimplantation, the risk of reinfection is high47).

2. Antimicrobial Therapy

For all surgical procedures, a total duration of antibiotic treatment of 12 weeks is recommended (Fig. 2). Antibiotic treatment without surgery is not recommended and should be only performed, if the patient refuses surgery or the surgical procedure is associated with high risk for patient life. In this case, antibiotic suppression might be considered.

Rifampin is effective to the implant-associated infections causes by staphylococci and Propionibacterium spp., whereas ciprofloxacin has biofilm activity against gram-negative bacteria. In Table 3 the recommended antibiotic therapies targeting different microorganisms are summarized4).

Table 3. Antimicrobial Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infection.

| Microorganism | Antibiotic (dose), check pathogen susceptibility | Duration | Followed by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus spp. | |||

| Oxacillin-/methicillin-susceptible | Cefazolin (3×2 g, i.v.)*+Rifampin (2×450 mg, p.o.) | 2 wk | According to susceptibility, Levofloxacin (2×500 mg, p.o.) or Cotrimoxazol (3×960 mg, p.o.) or Doxycyclin (2×100 mg, p.o.) +Rifampin(2×450 mg, p.o.) |

| Oxacillin-/methicillin-resistant | Vancomycin (2×1 g, i.v.)†+Rifampin (2×450 mg. p.o.) | 2 wk | Same combination as above for oxacillin-/methicillin-susceptible staphylococci |

| Rifampicin-resistant§ | Vancomycin (2×1 g, i.v.)† | 2 wk | Long-term suppression for ≥1 yr, depending on susceptibility (e.g., with cotrimoxazol, doxycycline or clindamycin) |

| Streptococcus spp. | Penicillin G (4×5 million U, i.v.)* or Ceftriaxon (1×2 g, i.v.) | 2 wk | Amoxicillin (3×1,000 mg, p.o.) or Levofloxacin (2×500 mg, p.o.) (consider suppression for 1 year) |

| Enterococcus spp. | |||

| Penicillin-susceptible | Ampicillin (4×2 g, i.v.)*+Gentamicin (2×60-80 mg, i.v.)‡ | 2–3 wk | Amoxicillin (3×1,000 mg, p.o.) |

| Penicillin-resistant§ | Vancomycin (2×1 g, i.v.)† or +Gentamicin (2×60-80 mg, i.v.)‡ | 2–4 wk | Linezolid (2×600 mg, p.o.), maximum 4 wk |

| Vancomycin-resistant | Individual; removal of the implant or life-long suppression necessary | ||

| Gram-negative bacteria | |||

| Enterobacteriaceae (Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Enterobacter, etc.) | Ciprofloxacin (2×750 mg, p.o.) | ||

| Nonfermenters (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter spp.) | Piperacillin/tazobactam (3×4.5 g, i.v.) or Meropenem (3×1 g, i.v.) or Ceftazidim (3×2 g, i.v.)+Gentamicin (1×240 mg, i.v.) | 2–3 wk | Ciprofloxacin (2×750 mg, p.o.) |

| Ciprofloxacin-resistant§ | Depending on susceptibility: meropenem (3×1 g), colistin (3×3 million U) and/or fosfomycin (3×5 g), i.v. | Oral suppression | |

| Anaerobes | |||

| Gram-positive anaerobes (Propionibacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Finegoldia magna) | Penicillin G (4×5 million U, i.v.)* or Ceftriaxon (1×2 g, i.v.)+Rifampin (2×450 mg, p.o.) | 2 wk | Levofloxacin (2×500 mg, p.o.) or Amoxicillin (3×1,000 mg, p.o.)+Rifampin (2×450 mg, p.o.) |

| Gram-negative anaerobes (Bacteroides) | Clindamycin (3×600 mg, i.v.) | 2 wk | Metronidazol (3×500 mg, p.o.) |

| Candida spp. | |||

| Fluconazole-susceptible§ | Caspofungin (1×50 mg, 1st day: 70 mg; i.v.) | 2 wk | Fluconazole (1×400 mg, suppression for ≥1 year; p.o.) |

| Fluconazole-resistant§ | Individual (e.g., with voriconazole 2×200 mg, p.o.); removal of the implant or long-term suppression | ||

Total duration of therapy: 12 weeks, usually 2 weeks intravenously, followed by oral route.

Laboratory testing 2 times/weekly: leukocytes, C-reactive protein, creatinine/estimated glomerular filtration rate, liver enzymes (AST/SGOT and ALT/SGPT).

Dose-adjustment according to renal function and body weight (<40 kg or >100 kg); the dosages needed renal adjustment are in bold.

i.v.: intravenously; p.o.: per oral.

Rifampin is administered only after the new prosthesis is implanted, wounds are dry and drains are removed; in patients aged >75 years, the rifampicin dose should be reduced to 2×300 mg, p.o.

*In case of anaphylaxis (such as Quincke's edema, bronchospasm, anaphylactic shock) or cephalosporin allergy: vancomycin (21 g, i.v.).

†Check vancomycin trough concentration (take blood before next dose) at least 1 time/week; therapeutic range, 15–20 µg/mL.

‡Give only, if gentamicin high-level (HL) is tested susceptible (consult your microbiology laboratory). In gentamicin HL-resistant enterococci: gentamicin is exchanged with ceftriaxone (1×2 g, i.v.).

§Difficult-to-treat.

OUTLOOK

Diagnosis and treatment of PJI are still difficult and have a lack of an universal definition. In order to successfully prevent and treat PJI as well as preserve implant functions in the future, PJI management must contain the effective, timely and individualized diagnosis and treatment with interdisciplinary collaboration. On the other hand, research and development of new diagnostic methods with more accuracy, simplicity, and convenience are required.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors declare that there is no potential conflict of interest relevant to this article.

References

- 1.Ulrich SD, Seyler TM, Bennett D, et al. Total hip arthroplasties: what are the reasons for revision. Int Orthop. 2008;32:597–604. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0364-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oleske DM, Bonafede MM, Jick S, Ji M, Hall JA. Electronic health databases for epidemiological research on joint replacements: considerations when making cross-national comparisons. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:660–665. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerli W, Trampuz A, Ochsner PE. Prosthetic-joint infections. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1645–1654. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra040181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achermann Y, Vogt M, Spormann C, et al. Characteristics and outcome of 27 elbow periprosthetic joint infections: results from a 14-year cohort study of 358 elbow prostheses. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:432–438. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alp E, Cevahir F, Ersoy S, Guney A. Incidence and economic burden of prosthetic joint infections in a university hospital: A report from a middle-income country. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9:494–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haenle M, Skripitz C, Mittelmeier W, Skripitz R. Economic impact of infected total knee arthroplasty. Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:196515. doi: 10.1100/2012/196515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aggarwal VK, Bakhshi H, Ecker NU, Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Kendoff D. Organism profile in periprosthetic joint infection: pathogens differ at two arthroplasty infection referral centers in Europe and in the United States. J Knee Surg. 2014;27:399–406. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1364102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Cofield RH, et al. Microbiologic diagnosis of prosthetic shoulder infection by use of implant sonication. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1878–1884. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01686-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gbejuade HO, Lovering AM, Webb JC. The role of microbial biofilms in prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop. 2015;86:147–158. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2014.966290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corvec S, Portillo ME, Pasticci BM, Borens O, Trampuz A. Epidemiology and new developments in the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Int J Artif Organs. 2012;35:923–934. doi: 10.5301/ijao.5000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trampuz A, Steckelberg J. Advances in the laboratory diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2003;14:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:e1–e25. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parvizi J, Gehrke T, Chen AF. Proceedings of the international consensus on periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J. 2013;95-B:1450–1452. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.33135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochsner PE, Borens O, Bodler PM. Infections of the musculoskeletal system: basic principles, prevention, diagnosis and treatment. Grandvaux: Swiss orthopaedics in-house-publisher; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Renz N, Yermak K, Perka C, Trampuz A. Alpha defensin lateral flow test for diagnosis of periprosthetic joint infection: not a screening but a confirmatory test. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:742–750. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.17.01005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad SS, Becker R, Chen AF, Kohl S. EKA survey: diagnosis of prosthetic knee joint infection. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:3050–3055. doi: 10.1007/s00167-016-4303-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pérez-Prieto D, Portillo ME, Puig-Verdie L, et al. C-reactive protein may misdiagnose prosthetic joint infections, particularly chronic and low-grade infections. Int Orthop. 2017;41:1315–1319. doi: 10.1007/s00264-017-3430-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piper KE, Fernandez-Sampedro M, Steckelberg KE, et al. Creactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and orthopedic implant infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Austin MS, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Lindsay A, Parvizi J. A simple, cost-effective screening protocol to rule out periprosthetic infection. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:65–68. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tande AJ, Patel R. Prosthetic joint infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2014;27:302–345. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trampuz A, Hanssen AD, Osmon DR, Mandrekar J, Steckelberg JM, Patel R. Synovial fluid leukocyte count and differential for the diagnosis of prosthetic knee infection. Am J Med. 2004;117:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgenstern C, Cabric S, Perka C, Trampuz A, Renz N. Synovial fluid multiplex PCR is superior to culture for detection of lowvirulent pathogens causing periprosthetic joint infection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2018;90:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schinsky MF, Della Valle CJ, Sporer SM, Paprosky WG. Perioperative testing for joint infection in patients undergoing revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1869–1875. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.01255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller M, Morawietz L, Hasart O, Strube P, Perka C, Tohtz S. Diagnosis of periprosthetic infection following total hip arthroplasty--evaluation of the diagnostic values of preand intraoperative parameters and the associated strategy to preoperatively select patients with a high probability of joint infection. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;3:31. doi: 10.1186/1749-799X-3-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krenn VT, Liebisch M, Kölbel B, et al. CD15 focus score: Infection diagnosis and stratification into low-virulence and high-virulence microbial pathogens in periprosthetic joint infection. Pathol Res Pract. 2017;213:541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:654–663. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spangehl MJ, Masri BA, O'Connell JX, Duncan CP. Prospective analysis of preoperative and intraoperative investigations for the diagnosis of infection at the sites of two hundred and two revision total hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:672–683. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199905000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portillo ME, Salvadó M, Trampuz A, et al. Improved diagnosis of orthopedic implant-associated infection by inoculation of sonication fluid into blood culture bottles. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1622–1627. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03683-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janz V, Trampuz A, Perka CF, Wassilew GI. Reduced culture time and improved isolation rate through culture of sonicate fluid in blood culture bottles. Technol Health Care. 2017;25:635–640. doi: 10.3233/THC-160660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tigges S, Stiles RG, Roberson JR. Appearance of septic hip prostheses on plain radiographs. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:377–380. doi: 10.2214/ajr.163.2.8037035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwee TC, Basu S, Torigian DA, Zhuang H, Alavi A. FDG PET imaging for diagnosing prosthetic joint infection: discussing the facts, rectifying the unsupported claims and call for evidence-based and scientific approach. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2013;40:464–466. doi: 10.1007/s00259-012-2319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwee TC, Kwee RM, Alavi A. FDG-PET for diagnosing prosthetic joint infection: systematic review and metaanalysis. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:2122–2132. doi: 10.1007/s00259-008-0887-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Portillo ME, Salvadó M, Sorli L, et al. Multiplex PCR of sonication fluid accurately differentiates between prosthetic joint infection and aseptic failure. J Infect. 2012;65:541–548. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qu X, Zhai Z, Li H, et al. PCR-based diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:2742–2746. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00657-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonanzinga T, Zahar A, Dütsch M, Lausmann C, Kendoff D, Gehrke T. How reliable is the alpha-defensin immunoassay test for diagnosing periprosthetic joint infection? A prospective study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:408–415. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4906-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sigmund IK, Holinka J, Gamper J, et al. Qualitativeα-defensin test (Synovasure) for the diagnosis of periprosthetic infection in revision total joint arthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:66–72. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0295.R1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deirmengian C, Kardos K, Kilmartin P, et al. The alpha-defensin test for periprosthetic joint infection outperforms the leukocyte esterase test strip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:198–203. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3722-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borens O, Yusuf E, Steinrücken J, Trampuz A. Accurate and early diagnosis of orthopedic device-related infection by microbial heat production and sonication. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1700–1703. doi: 10.1002/jor.22419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giulieri SG, Graber P, Ochsner PE, Zimmerli W. Management of infection associated with total hip arthroplasty according to a treatment algorithm. Infection. 2004;32:222–228. doi: 10.1007/s15010-004-4020-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deirmengian C, Greenbaum J, Lotke PA, Booth RE, Jr, Lonner JH. Limited success with open debridement and retention of components in the treatment of acute Staphylococcus aureus infections after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18(7 Suppl 1):22–26. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(03)00288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trampuz A, Zimmerli W. Prosthetic joint infections: update in diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135:243–251. doi: 10.4414/smw.2005.10934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tschudin-Sutter S, Frei R, Dangel M, et al. Validation of a treatment algorithm for orthopaedic implant-related infections with device-retention-results from a prospective observational cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;22:457. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ilchmann T, Zimmerli W, Ochsner PE, et al. One-stage revision of infected hip arthroplasty: outcome of 39 consecutive hips. Int Orthop. 2016;40:913–918. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-2833-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahar A, Webb J, Gehrke T, Kendoff D. One-stage exchange for prosthetic joint infection of the hip. Hip Int. 2015;25:301–307. doi: 10.5301/hipint.5000264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD. Reinfection outcomes following one- and two-stage surgical revision of infected hip prosthesis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0139166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cha MS, Cho SH, Kim DH, et al. Two-stage total knee arthroplasty for prosthetic joint infection. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2015;27:82–89. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2015.27.2.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]