Abstract

Planar cell polarity (PCP) describes a cell–cell communication process through which individual cells coordinate and align within the plane of a tissue. In this study, we show that overexpression of Fuz, a PCP gene, triggers neuronal apoptosis via the dishevelled/Rac1 GTPase/MEKK1/JNK/caspase signalling axis. Consistent with this finding, endogenous Fuz expression is upregulated in models of polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases and in fibroblasts from spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3) patients. The disruption of this upregulation mitigates polyQ‐induced neurodegeneration in Drosophila. We show that the transcriptional regulator Yin Yang 1 (YY1) associates with the Fuz promoter. Overexpression of YY1 promotes the hypermethylation of Fuz promoter, causing transcriptional repression of Fuz. Remarkably, YY1 protein is recruited to ATXN3‐Q84 aggregates, which reduces the level of functional, soluble YY1, resulting in Fuz transcriptional derepression and induction of neuronal apoptosis. Furthermore, Fuz transcript level is elevated in amyloid beta‐peptide, Tau and α‐synuclein models, implicating its potential involvement in other neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases. Taken together, this study unveils a generic Fuz‐mediated apoptotic cell death pathway in neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: alpha‐synuclein, amyloid beta‐peptide, polyglutamine, Tau, Yin Yang 1

Subject Categories: Autophagy & Cell Death, Neuroscience

Introduction

Planar cell polarity (PCP) signalling is an evolutionarily conserved pathway by which directional information regarding polarized cell movement, e.g., along an epithelial plane, is provided to cells 1. The PCP signalling axis involves two subsets of genes, PCP core and PCP effector genes. Once stimulated, the core and effector genes are activated consecutively to govern orientated cell migration and the establishment of cytoskeletal structures 1. Dishevelled (Dvl in mammals or Dsh in Drosophila 2) and Fuz (or fuzzy in Drosophila 3) are two representative PCP core and effector genes, respectively 4. It has been reported that PCP regulates mammalian nervous system development. In mice, the disruption of Dvl function causes hydrocephalus 5 and that a Fuz‐null mutant displays neural tube defects (NTDs) 6. Dominant mutations in Fuz were reported to cause NTDs in humans 7. A functional study of these dominant mutations revealed a failure of directional cell motility and cell fusion, supporting that Fuz mutants perturb the closure of neural tubes 7. These observations suggest Fuz is essential for the development of the human nervous system. However, whether Fuz plays a role in neurodegenerative diseases is unclear.

Polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases, including Huntington's disease and several types of spinocerebellar ataxias, encompass a set of neurodegenerative disorders 8. These diseases are caused by the expansion of CAG repeats, which code for glutamines, in the open reading frames of the affected genes 9. The clinical features presented by polyQ patients include loss of movement coordination and cognitive disabilities 10, 11. Perturbation of various molecular and cellular processes is implicated in the pathology of polyQ diseases including the regulation of apoptosis and gene transcription 12. Normally, apoptosis is tightly controlled by the expression of anti‐apoptotic and pro‐apoptotic genes 13. In polyQ diseases, the misexpression of apoptotic gene triggers the induction of apoptosis, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of the diseases 14, 15. In particular, the caspase cascade has been shown to be activated in polyQ‐mediated apoptosis 16, 17. Cleavage of caspases was observed in polyQ patients 18. In addition to polyQ diseases, apoptosis is also involved in other neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer's disease (AD), Tauopathy and Parkinson's disease (PD) 19, 20.

Fuz −/− mutant mice were previously reported to display an enhanced rate of cell proliferation 21, implying a role of Fuz in maintaining the balance between cell proliferation and cell death. In the current study, we report that overexpression of Fuz triggers neuronal apoptosis, and further demonstrate Fuz exploits the Dvl‐Rac1‐MAPK‐caspase signalling axis to initiate apoptotic cell death. We demonstrate that the expression of Fuz/Fuz is upregulated in polyQ diseases, and the perturbation of Fuz expression suppresses neurodegeneration. Furthermore, we show that the transcriptional regulator Yin Yang 1 (YY1) negatively regulates Fuz expression via hypermethylating Fuz promoter. In polyQ diseases, soluble YY1 protein expression is reduced in patient brains, resulting in hypomethylation of the Fuz promoter. Overexpression of YY1 corrects the Fuz promoter hypomethylation, reduces the upregulation of Fuz and suppresses apoptosis in polyQ disease models. Most importantly, we demonstrate that Fuz promoter hypomethylation is a common feature shared by several neurodegenerative conditions that associate with amyloid beta‐peptide, Tau and α‐synuclein. Our findings indicate Fuz functions as a communal pro‐apoptotic switch in neurodegenerative diseases.

Results

Fuz stimulates the Dvl/Rac1 GTPase/MEKK1/JNK/caspase signalling pathway to trigger apoptosis

We performed a quantitative real‐time polymerase chain reaction (qRT–PCR) analysis to determine the endogenous expression level of Fuz in different human tissues. Fuz transcript was detected in the normal human brain, kidney and muscle, indicating endogenous functions of Fuz in these organs (Fig EV1A). Within the human brain, endogenous Fuz expression was detected in the caudate, substantia nigra and the cerebellar regions (Fig EV1B). To investigate the effect of Fuz overexpression, we transfected rat primary cortical neurons with increasing amounts of flag‐Fuz expression construct (from 0.2 to 1.0 μg). When the relative level of the overexpressed Fuz protein in neurons reached approximately 2.5‐folds of the endogenous Fuz protein, we detected caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig 1A), as well as a significant elevation of neuronal cell death in these neurons (Fig 1B). This indicates that a 2.5‐fold elevation of Fuz protein in neurons is sufficient to induce noticeable cell death (Fig 1A and B). We thus used this transfection condition to further elucidate the apoptotic signalling pathway mediated by Fuz. When Fuz was overexpressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells, we also observed a similar cytotoxic effect (Fig 1C). We further showed that Fuz overexpression induced cell death through the induction of apoptosis (Fig 1D and E). In contrast, overexpression of other PCP effector (Inturned or Fritz) and core (Dvl or Flamingo) proteins did not induce neuronal cell death (Fig EV1C).

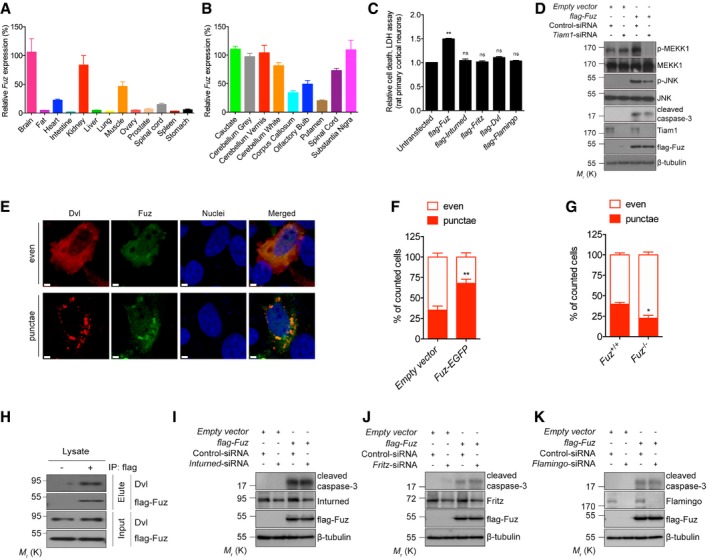

Figure EV1. Data related to Fig 1 .

-

ADifferential expression of Fuz in normal human tissues. Fuz expression in brain from the first experimental trial is defined as “100%”, and the relative expression of Fuz is normalized to that of brain. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3.

-

BDifferential expression of Fuz in normal human brain regions. Fuz expression in caudate from the first experimental trial is defined as “100%”, and the relative expression of Fuz is normalized to that of caudate. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3.

-

CInturned, Fritz, Dvl and Flamingo did not trigger neuronal cell death when overexpressed, respectively, in rat primary cortical neurons. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. ns represents no significant difference. **P < 0.01.

-

DKnockdown of Tiam1 expression suppressed the MAPK‐caspase pathway activation induced by Fuz overexpression in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

-

E, F(E) HEK293 cells transfected with 0.2 μg flag‐Dvl displayed both “even” and “punctae” staining patterns. “even” indicates cells with evenly distributed Dvl, with occasional small Dvl dots. “punctae” indicates cells with large Dvl aggregates. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars: 2 μm. Overexpression of Fuz (green) promoted Dvl (red) to form “punctae”, and Fuz protein colocalized with these “punctae”. (F) is the quantification of (E). Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. For every control or experimental group, at least 120 cells were counted in each replicate. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. **P < 0.01.

-

GKnockout of Fuz reduced the percentage of cells with Dvl “punctae”. The parental HEK293 cells were used as control. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. For every control or experimental group, at least 120 cells were counted in each replicate. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

HExogenous Fuz protein interacted with endogenous Dvl protein in HEK293 cells. “+” denotes the immunoprecipitation was performed using anti‐flag antibody, “−” denotes no antibody control. n = 3.

-

I–KKnockdown of Inturned (I), Fritz (J) or Flamingo (K) did not suppress Fuz‐induced caspase‐3 cleavage in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

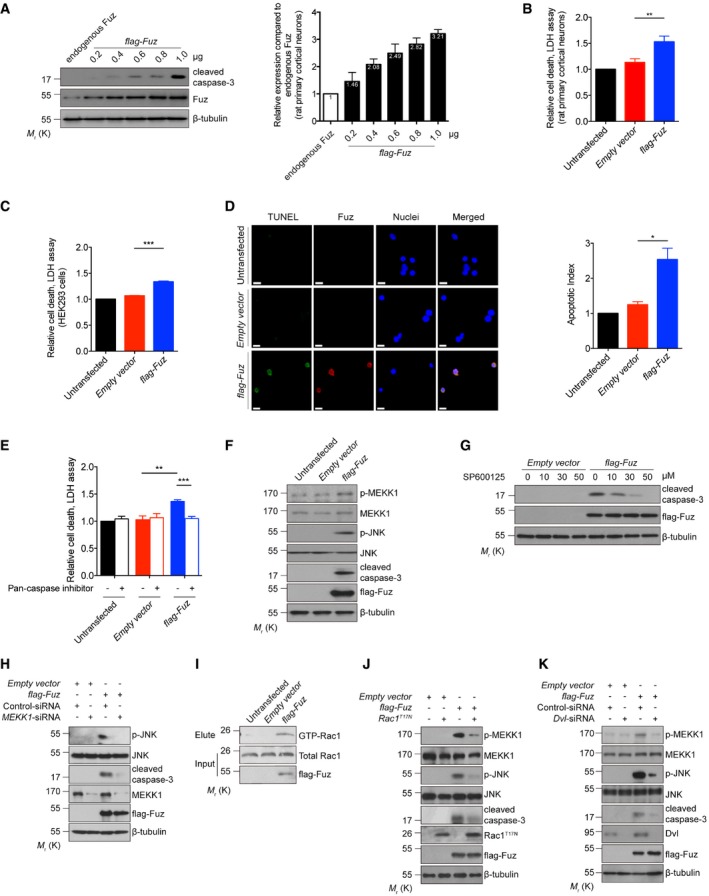

Figure 1. Fuz triggers apoptosis via the Dvl‐Rac1‐MAPK‐caspase signalling axis.

- When overexpressed, Fuz induced caspase‐3 cleavage in rat primary cortical neurons. Right panel shows the relative fold increase of protein level of flag‐Fuz to endogenous Fuz expressed in transfected neurons. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3.

- Fuz overexpression caused cell death in rat primary cortical neurons. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. **P < 0.01.

- Fuz overexpression induced cell death in HEK293 cells. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ***P < 0.001.

- Overexpression of Fuz in HEK293 cells triggered apoptosis. TUNEL‐positive cells (green) were stained with anti‐BrdU antibody, and overexpressed Fuz (red) was detected with anti‐flag antibody. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 10 μm. Right panel shows the quantification of TUNEL assay results. The apoptotic index is calculated by dividing the percentage of TUNEL‐positive cells in empty vector‐transfected or flag‐Fuz‐transfected cells by the percentage of TUNEL‐positive cells in the untransfected control. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. For every control or experimental group, at least 120 cells were counted in each replicate. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

- Fuz‐induced cell death was suppressed when the activities of caspases were inhibited in HEK293 cells. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- Overexpression of Fuz induced MEKK1 and JNK phosphorylation, as well as caspase‐3 cleavage in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- Fuz‐induced caspase‐3 activation was suppressed by JNK inhibitor SP600125 in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- Knockdown of MEKK1 expression suppressed the JNK activation and caspase‐3 cleavage in flag‐Fuz‐transfected HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- Overexpression of Fuz induced Rac1 activation in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- Blockage of Rac1 activity using the dominant‐negative Rac1T17N mutant protein suppressed the MAPK‐caspase pathway activation in flag‐Fuz‐transfected HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- Knockdown of Dvl expression suppressed the MAPK‐caspase activation in Fuz‐expressing HEK293 cells. n = 3.

The mitogen‐activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1) was reported to activate apoptosis via the c‐Jun N‐terminal kinase (JNK) pathway 22. We observed that Fuz overexpression induced the phosphorylation of MEKK1 and JNK, as well as caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig 1F). Further, we found that caspase‐3 cleavage in Fuz‐expressing cells was blocked upon the treatment of either the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Fig 1G) or MEKK1‐siRNA (Fig 1H). The above results demonstrate that Fuz induces apoptosis via the MEKK1/JNK/caspase pathway. Next, we showed that Fuz overexpression triggered activation of the Rac family small GTPase 1 (Rac1; Fig 1I). Further, the coexpression of a dominant‐negative form of Rac1 (Rac1T17N) diminished Fuz‐mediated MEKK1/JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig 1J). The activity of small GTPases is regulated by guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs; 23). T‐cell lymphoma invasion and metastasis 1 (Tiam1) is a specific GEF for Rac1, and it controls Rac1 activation in neurons 24. When Tiam1 expression was knocked down, we found that Fuz‐induced MEKK1/JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage were diminished (Fig EV1D). These results thus highlight the significance of Rac1 and Tiam1 in the Fuz‐induced apoptosis pathway.

Fuz interacts with another PCP pathway protein Dvl 25. Previous studies demonstrated that Dvl “punctae” recruit Rac1 and Tiam1 to a multimeric protein complex for Rac1 activation 26. We investigated whether Dvl is involved in Fuz‐mediated apoptosis. When Dvl was overexpressed alone, 35% of Dvl‐transfected cells were found to display the Dvl “punctae” pattern (Fig EV1E and F). Upon Fuz coexpression, the percentage of Dvl/Fuz double‐transfected cell that showed Dvl “punctae” pattern was significantly elevated to 68% (Fig EV1E and F). When Dvl was overexpressed in Fuz knockout cells (Fuz −/−; Appendix Fig S1A), the percentage of cells that showed Dvl “punctae” pattern was significantly reduced (Fig EV1G). In addition, we observed that Fuz colocalized with Dvl “punctae” in cells and further showed that Fuz and Dvl proteins physically interacted with each other (Fig EV1H). When we knocked down Dvl expression in Fuz‐expressing cells, a reduction in levels of MEKK1 and JNK phosphorylation, as well as caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig 1K), was observed. In contrast, knockdown of the expression of other PCP genes, including Inturned, Fritz and Flamingo, did not affect Fuz‐induced caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig EV1I–K). Taken together, our findings depict a signalling axis that involves Dvl, Rac1, MEKK1, JNK and the caspase cascade, through which Fuz mediates apoptotic initiation.

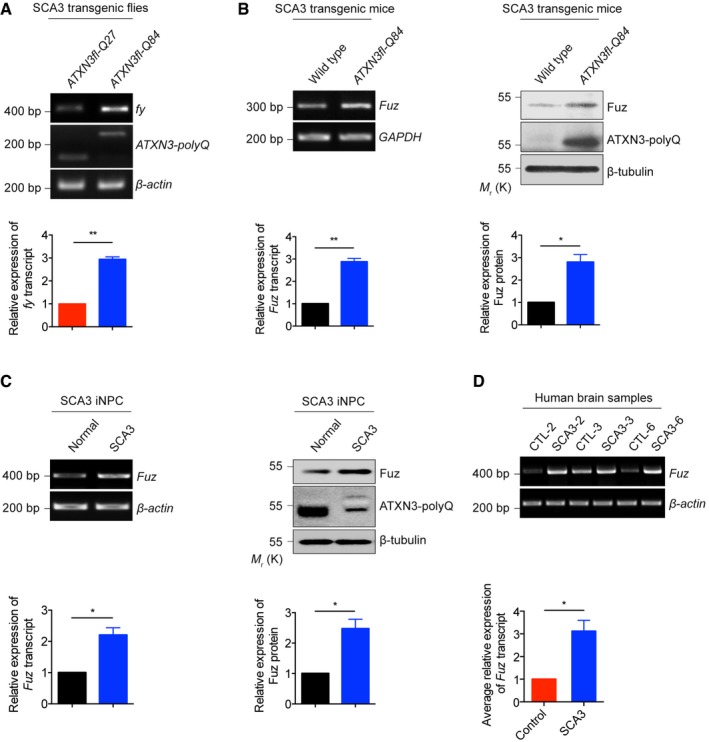

Expression of Fuz/Fuz is upregulated in polyglutamine diseases

Given the tissue distribution of Fuz in human brain (Fig EV1A) and its pro‐apoptotic function (Fig 1A–K), we investigated the role of Fuz in neurodegeneration. Apoptosis is involved in numerous neurodegenerative diseases, including polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases such as Huntington's disease (HD) and spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3). Intriguingly, the induction of Fuz/Fuz at both mRNA and protein levels were observed in cell models of HD and SCA3 (Fig EV2A and B). A similar induction was further observed in transgenic Drosophila (Fig 2A) and mouse (Fig 2B) models of SCA3, as well as in SCA3 patient fibroblasts (Fig EV2C). We then generated induced neural progenitor cells (iNPCs) from SCA3 patient fibroblasts (Fig EV2D and E) and examined Fuz expression in iNPCs. Compared with the control iNPCs, Fuz/Fuz expression was elevated in SCA3 iNPCs (Fig 2C). Fuz induction was further detected in RNA samples from SCA3 patient brains (Fig 2D). In summary, we observed the upregulation of Fuz/Fuz expression in polyQ diseases.

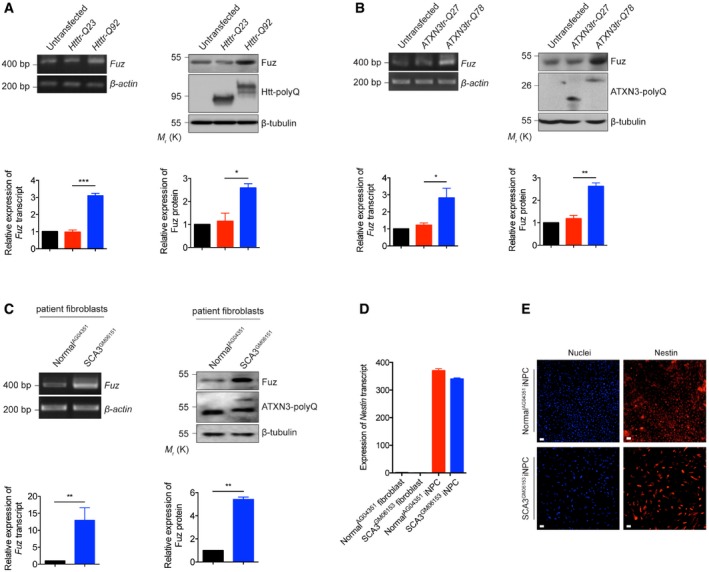

Figure EV2. Data related to Fig 2 .

- Both Fuz transcript and Fuz protein levels were upregulated in the Htttr‐Q92‐expressing HEK293 cells. “Htttr” indicates truncated Huntingtin (Htt), disease protein of Huntington's disease (HD). Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

- Overexpression of expanded ATXN3tr‐Q78 protein increased the levels of expression of Fuz transcript and Fuz protein in HEK293 cells. “ATXN3tr” indicates truncated ataxin‐3 (ATXN3), disease protein of spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3). Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

- The expression levels of Fuz transcript and Fuz protein were induced in SCA3 patient fibroblasts. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. **P < 0.01.

- Quantitative RT–PCR was used to determine the expression level of induced neural progenitor cells (iNPCs) specific marker Nestin in fibroblasts and iNPCs. Expression of Nestin was robustly induced in both normal and SCA3 iNPCs. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3.

- Immunostaining of iNPCs using anti‐Nestin (red) antibody, and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Both normal and SCA3 iNPCs showed the expression of Nestin protein. Scale bars: 100 μm. n = 3.

Figure 2. fuzzy/Fuz transcription is induced in polyQ diseases.

- Upregulation of fy transcription was observed in a SCA3 transgenic Drosophila model. “ATXN3fl” indicates full‐length ataxin‐3 (ATXN3), disease protein of SCA3. The flies were of genotypes w; gmr::Gal4 UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q27/+; +/+ and w; gmr::Gal4/+; UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q84/+. Lower panel shows the quantification of fy transcript expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. **P < 0.01.

- The expression levels of Fuz transcript and Fuz protein were upregulated in brain samples of 6‐month‐old SCA3 transgenic mice. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

- The expression levels of Fuz transcript and Fuz protein were upregulated in SCA3 iNPCs. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

- The expression level of Fuz transcript was upregulated in SCA3 patient brain samples. Background information on the control and patient brains are summarized in Appendix Table S2. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

Downregulation of Fuz/fuzzy rescues the cytotoxicity and neurodegeneration in polyQ diseases

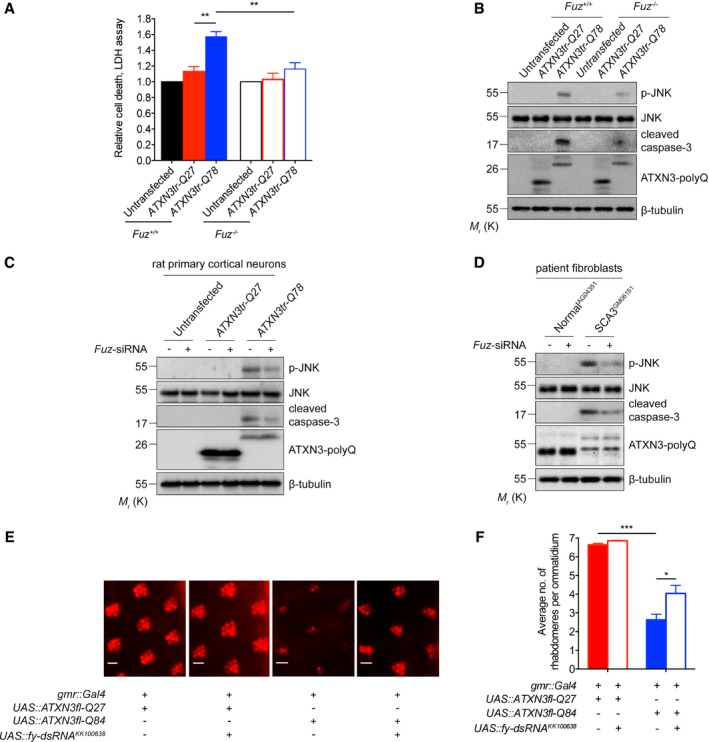

Next, we perturbed endogenous Fuz expression in our polyQ disease models and examined its effect on apoptosis and neurodegeneration. In contrast to the parental cells, when the SCA3 mutant construct ATXN3tr‐Q78 was expressed in Fuz −/− cells (Appendix Fig S1A), we observed a reduction in cell death (Fig 3A), JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig 3B). A similar effect was observed in rat primary cortical neurons transfected with the ATXN3tr‐Q78 transgene (Fig 3C and Appendix Fig S1B), as well as in SCA3 patient fibroblasts (Fig 3D and Appendix Fig S1C) with Fuz expression knocked down. These findings clearly demonstrate the involvement of Fuz in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐induced cell death.

Figure 3. Perturbation of Fuz/fuzzy expression rescues polyQ disease toxicity.

-

AExpression of ATXN3tr‐Q78 in Fuz −/− HEK293 cells showed reduced cell death. The parental HEK293 cells were used as control. Knockout of Fuz did not alter relative cell death in the untransfected or ATXN3tr‐Q27 cells, indicating that Fuz knockout did not induce cell death. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. **P < 0.01.

-

BThe JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage induced by ATXN3tr‐Q78 were suppressed in Fuz −/− HEK293 cells. The parental HEK293 cells were used as control. n = 3.

-

CKnockdown of Fuz expression suppressed JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing rat primary cortical neurons. n = 3.

-

DKnockdown of Fuz expression suppressed the activation of JNK and caspase‐3 in SCA3 patient fibroblasts. n = 3.

-

E, F(E) Knockdown of fy expression rescued neurodegenerative eye phenotype in SCA3 transgenic flies. The integrity of rhabdomeres in ATXN3fl‐Q27 flies was not affected upon fy knockdown. The flies were of genotypes w; gmr::Gal4 UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q27/+; +/+, w; gmr::Gal4 UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q27/UAS::fy‐dsRNA KK100638 ; +/+, w; gmr::Gal4/+; UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q84/+ and w; gmr::Gal4/UAS::fy‐dsRNA KK100638 ; UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q84/+. Scale bars: 5 μm. (F) is the quantification of (E). Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. For every control or experimental group, a total of 200 ommatidia collected from 20 fly eyes were examined in each replicate. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

We next knocked down fuzzy (fy; Appendix Fig S1D), the orthologue of Fuz, in Drosophila to study its role in polyQ neurodegeneration in vivo. When expressed in the Drosophila brain, including the retinal neurons, the human disease transgene ATXN3fl‐Q84 induced neurodegeneration (27; Fig 3E and F). Both knockdown and knockout of fy significantly suppressed the ATXN3fl‐Q84‐mediated neurodegenerative phenotype (Fig 3E and F, and Appendix Fig S1D–F). In addition, we found that fy knockdown mitigated neurodegeneration in a Drosophila model of HD (Appendix Fig S1G and H). Taken together, these findings highlight the key role of Fuz in SCA3 pathogenesis, as well as in other polyQ degenerative disorder.

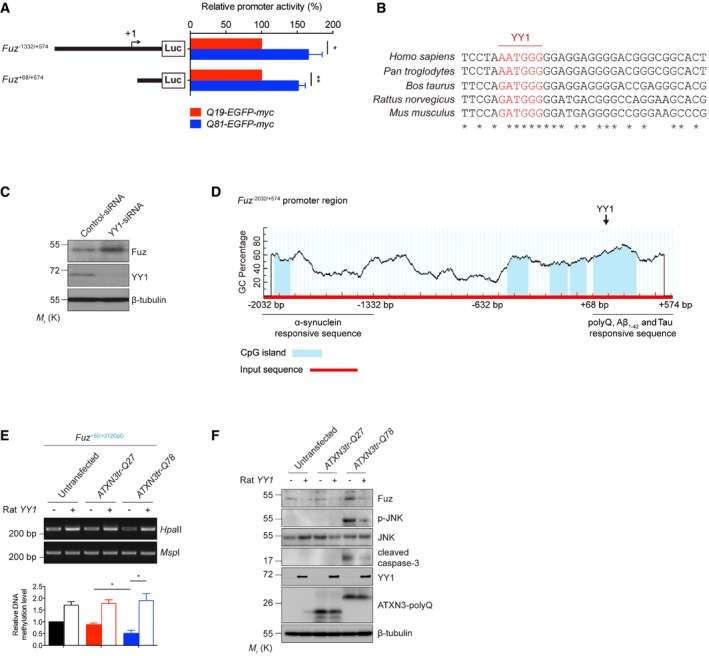

YY1 represses Fuz transcription via hypermethylating Fuz promoter

We next studied the mechanism through which expanded polyQ disease protein induces Fuz transcription. We first employed the luciferase assay to define the polyQ‐responsive element within the Fuz promoter (Fuz −1332/+574; Fig EV3A) and found that the Fuz +68/+574 region responded to expanded polyQ protein expression (Fig EV3A). A YY1 binding site (AATGGG) was predicted within the Fuz +68/+574 promoter region (Fig 4A), and this binding site is highly conserved among the mammalian genomes (Fig EV3B). YY1 is a multi‐functional transcriptional regulator that controls gene expression in the mammalian brain 28, and it plays crucial role in governing neuronal functions 29. In addition to the predicted YY1 binding site in the Fuz promoter, a binding site (ATGGC; 30) for Pleiohomeotic (PHO), the Drosophila orthologue of YY1 31, was also predicted in the Drosophila fy promoter sequence, suggesting that the transcriptional regulation of Fuz/fy by YY1/PHO is evolutionarily conserved. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation, we confirmed the binding of YY1 protein to the Fuz promoter (Fuz +117/+347CpG; Fig 4B) and detected an interaction between YY1 protein and Fuz promoter using in vitro DNA binding assay (Fig 4C). Our results thus indicate YY1 plays a regulatory role in controlling Fuz transcription.

Figure EV3. Data related to Figs 4 and 5 .

- Luciferase assay was performed to examine human Fuz promoter activity in Q19‐EGFP‐myc or Q81‐EGFP‐myc‐expressing HEK293 cells. Two expanded polyQ‐responsive regions, Fuz −1332/+574 and Fuz +68/+574, were identified. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 5. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

- Inter‐species sequence comparison of the human (Homo sapiens), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), cow (Bos taurus), rat (Rattus norvegicus) and mouse (Mus musculus) Fuz promoter regions. Nucleotides highlighted in red indicate putative YY1 binding sites. “*” indicates the identical nucleotides among the different species.

- Knockdown of YY1 expression increased the protein expression of Fuz in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

- A diagram illustrates the location of five putative CpG islands (blue) within the human Fuz −2032/+574 promoter region. A putative YY1 binding site was uncovered within Fuz +117/+347CpG. This diagram also summarizes the Fuz promoter sequences that are responsive to the different disease proteins and peptide. Fuz −2032/−1332 responds to α‐synuclein overexpression. Fuz +68/+574 responds to expanded polyQ overexpression, Aβ1–42 peptide treatment and Tau overexpression.

- HpaII DNA methylation assay was performed to determine the methylation status of Fuz +50/+312CpG in rat primary cortical neurons. The ATXN3tr‐Q78‐induced hypomethylation in Fuz promoter was rescued by rat YY1 overexpression. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz +50/+312CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. *P < 0.05.

- Overexpression of rat YY1 suppressed the ATXN3tr‐Q78‐mediated Fuz induction, JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage in rat primary cortical neurons. n = 3.

Figure 4. YY1 interacts with Fuz promoter in vivo and in vitro .

-

ASchematic representation of the human Fuz −1332/+574 promoter region. The Fuz +68/+574 was enlarged to show the detailed nucleotide sequence. A putative CpG island was found within Fuz +68/+574 and was defined as Fuz +117/+347CpG. “+1” is the transcriptional initiation site (arrow). The CpG island is highlighted in blue, and sequence of the YY1 binding site is underlined and highlighted in red.

-

BChromatin immunoprecipitation assay demonstrated the binding between YY1 protein and Fuz +117/+347CpG DNA fragment. The blue bar indicates the Fuz +117/+347CpG sequence. However, Fuz −802/−612 (orange) represents a region that did not show interaction with YY1 protein. n = 3.

-

C, D(C) In vitro DNA binding assay demonstrated the binding between purified YY1 protein and purified Fuz +117/+347CpG DNA fragment. When a mutation (green) was introduced to the YY1 site (red) within the Fuz +117/+347CpG fragment, YY1 binding was reduced. (D) is the quantification of the intensity of the Fuz +117/+347CpG DNA bands as shown in (C). Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

EMutating the YY1 binding site in the Fuz promoter increased its transcriptional activity in HEK293 cells. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 5. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ***P < 0.001.

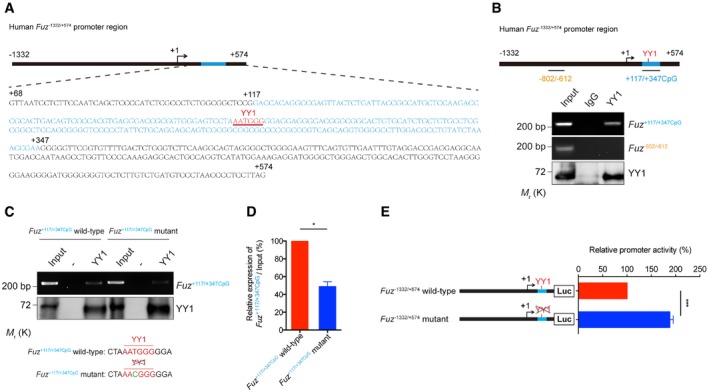

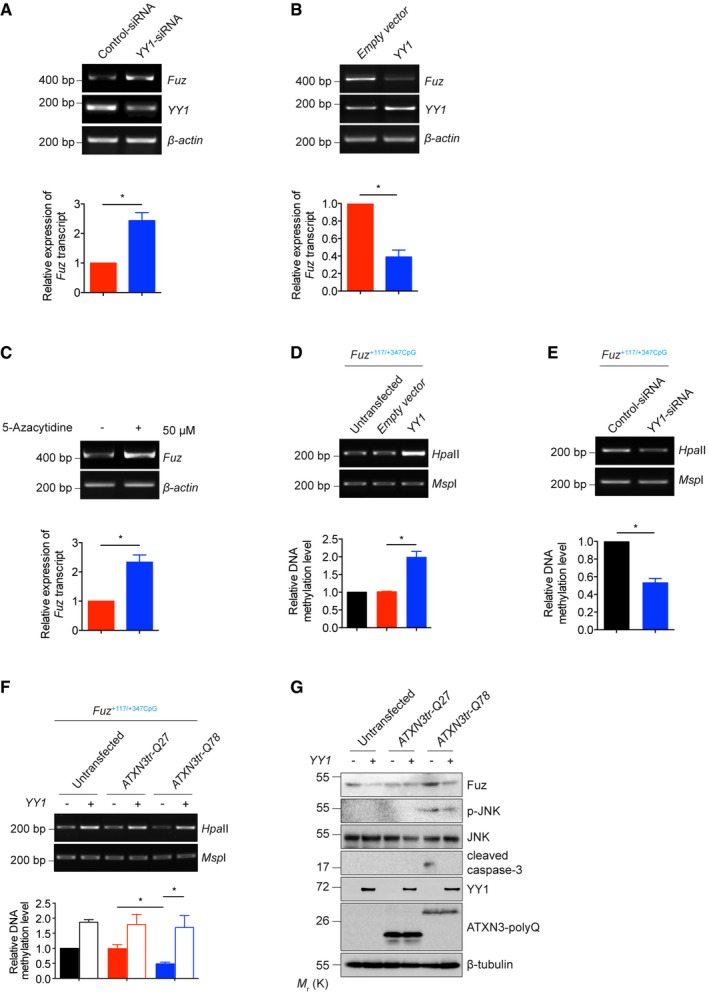

Previous reports illustrate that YY1 can both serve as a transcriptional activator 32 or a repressor 33. We found that altering one conserved nucleotide in the YY1 binding site in the Fuz +117/+347CpG region, from AATGGG to AACGGG, resulted in a significant reduction of the binding of YY1 protein to Fuz promoter (Fig 4C and D). When a Fuz −1332/+574 promoter reporter construct harbouring the same single point mutation was used in a luciferase assay, cells transfected with this mutant (Fuz −1332/+574 mutant) reporter construct exhibited a 1.9‐fold increase of luciferase activity when compared to those expressing the wild‐type (Fuz −1332/+574 wild‐type) luciferase construct (Fig 4E). Furthermore, we found that knockdown of YY1 expression led to an increase in endogenous Fuz/Fuz expression (Figs 5A and EV3C). In contrast, YY1 overexpression resulted in a downregulation of Fuz expression (Fig 5B). These findings indicate that YY1 acts as a transcriptional repressor to attenuate Fuz transcription.

Figure 5. Expanded polyQ perturbs the function of YY1 to derepress Fuz expression.

-

AKnockdown of YY1 expression upregulated Fuz expression in HEK293 cells. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

BOverexpression of YY1 downregulated Fuz expression in HEK293 cells. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

C5‐Azacytidine treatment induced the expression of Fuz in HEK293 cells. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

D, EOverexpression of YY1 promoted the hypermethylation (D) while knockdown of YY1 expression led to the hypomethylation (E) of Fuz +117/+347CpG. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz +117/+347CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

-

FOverexpression of YY1 promoted the hypermethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG in the untransfected or ATXN3tr‐Q27‐expressing HEK293 cells. The ATXN3tr‐Q78‐mediated hypomethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG was rescued by YY1 overexpression. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz +117/+347CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. *P < 0.05.

-

GOverexpression of YY1 suppressed the ATXN3tr‐Q78‐mediated Fuz induction, JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage in HEK293 cells. n = 3.

Previous studies showed that YY1 mediates gene silencing by recruiting DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) to gene promoters, thus promoting the hypermethylation of CpG islands 34. We found putative CpG islands (Fuz +117/+347CpG; Fig EV3D) within the Fuz promoter region where the YY1 binding site resides (Fig 4A). To determine whether promoter DNA methylation affects Fuz transcriptional control, we treated HEK293 cells with the DNMT inhibitor 5‐azacytidine. Upon treatment, we observed an upregulation of Fuz expression (Fig 5C). We further demonstrated that YY1 overexpression induced the hypermethylation of the Fuz +117/+347CpG (Fig 5D), whereas YY1 knockdown exerted an opposite effect (Fig 5E). These results strongly indicate that YY1 represses Fuz transcription via hypermethylating the Fuz promoter.

Expanded polyQ derepresses Fuz expression via perturbing the function of YY1

We sought to determine whether the changes in CpG island methylation in the Fuz promoter occur in cells expressing the polyQ disease protein ATXN3tr‐Q78. Indeed, we found that the Fuz +117/+347CpG was less methylated in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing cells when compared with the ATXN3tr‐Q27 or untransfected control (Fig 5F). Remarkably, the Fuz +117/+347CpG hypomethylation status in the ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing cells was restored upon YY1 coexpression (Fig 5F), indicating that YY1 affects Fuz induction through altering its promoter DNA methylation. A similar effect was also observed in rat primary cortical neurons expressing ATXN3tr‐Q78 (Fig EV3E). We further demonstrated that YY1 overexpression reduced Fuz protein expression, JNK phosphorylation and caspase‐3 cleavage in both HEK293 cells and rat primary cortical neurons that expressed ATXN3tr‐Q78 (Figs 5G and EV3F).

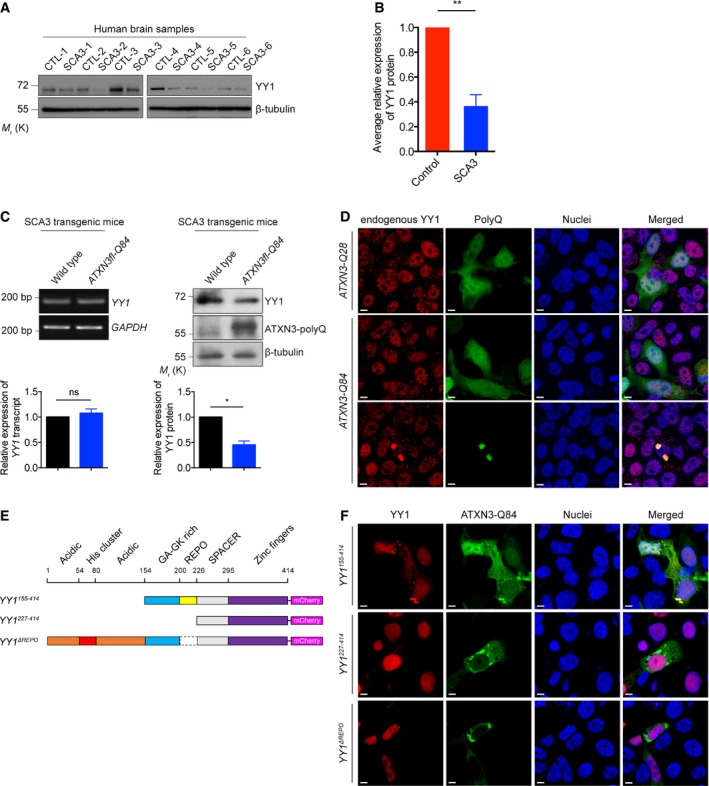

Recruitment of YY1 to protein aggregates and a reduction of its soluble level in polyQ diseases

We next evaluated YY1 protein expression in cerebellar cortex samples collected from SCA3 patients. When compared with age‐matched control group, the SCA3 group exhibited reduced YY1 protein level (Fig 6A and B). Furthermore, we observed a similar reduction in SCA3 transgenic mouse brains (Fig 6C). Despite a change in YY1 protein level was detected, we found that YY1 mRNA expression was not altered in these mice (Fig 6C). An immunofluorescence analysis revealed that endogenous YY1 was recruited to polyQ protein aggregates in ATXN3‐Q84‐expressing cells (Fig 6D). This explains the reduction of soluble YY1 protein expression in the SCA3 models (Fig 6A–C).

Figure 6. Soluble YY1 protein level is reduced in polyQ diseases.

-

A, B(A) Soluble YY1 protein level was reduced in SCA3 patient brain samples versus age‐matched controls. Background information on the control and patient brains are summarized in Appendix Tables S2 and S3. (B) is the quantification of (A). Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 6. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. **P < 0.01.

-

CExpression of soluble YY1 protein, but not YY1 transcript, was reduced in the brains of 6‐month‐old SCA3 transgenic mice. Lower panel shows the quantification of YY1 transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ns represents no significant difference. *P < 0.05.

-

DYY1 protein was sequestered to the ATXN3‐Q84 protein aggregates (green) in HEK293 cells, while its nuclear localization was not affected in ATXN3‐Q28‐expressing cells or cells with no ATXN3‐Q84 protein aggregate detected. Endogenous YY1 (red) was stained with anti‐YY1 antibody. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

-

ESchematic representation of the domain structure of the human full‐length and truncated YY1 proteins used in this study.

-

FYY1155–414, but not YY1227–414 and YY1ΔREPO proteins (red), was sequestered to the ATXN3‐Q84 protein aggregates (green) in HEK293 cells. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

We took a domain deletion mapping approach to determine which domains contribute to the recruitment of YY1 to polyQ protein aggregates (Fig 6E). The truncated YY1 proteins were independently coexpressed with ATXN3‐Q84 in our SCA3 cell model; the colocalization of the truncated YY1 proteins with polyQ protein aggregates was determined by confocal microscopy. Similar to the endogenous YY1 protein (Fig 6D), the YY1154–414 truncated protein was recruited to the polyQ protein aggregates. In contrast, the YY1227–414 and YY1ΔREPO truncated proteins did not colocalize with polyQ protein aggregates (Fig 6F). The region that was deleted in both YY1227–414 and YY1ΔREPO is the REcruitment of POlycomb (REPO) domain; our result thus indicates that the REPO domain is required for the recruitment of YY1 to polyQ protein aggregates.

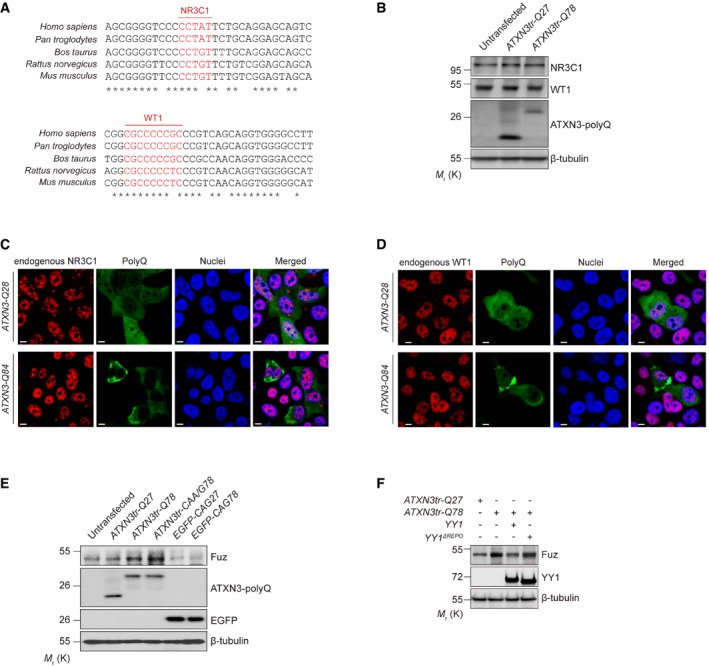

In addition to YY1, the binding sites for two other neuronal transcriptional regulators nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (NR3C1; 35) and Wilms tumour 1 (WT1; 36) were predicted within Fuz +68/+574 promoter region (Fig EV4A). We investigated the protein expression and localization of both NR3C1 and WT1 in polyQ‐expressing cells. In contrast to YY1 (Fig 6A), soluble protein levels of NR3C1 and WT1 in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing cells were comparable to the controls (Fig EV4B). We also did not observe the recruitment of NR3C1 and WT1 to polyQ protein aggregates (Fig EV4C and D).

Figure EV4. Data related to Fig 6 .

-

AInter‐species sequence comparison of the human (Homo sapiens), chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), cow (Bos taurus), rat (Rattus norvegicus) and mouse (Mus musculus) Fuz promoter regions. Nucleotides highlighted in red indicate putative NR3C1 and WT1 binding sites. “*” indicates the identical nucleotides among the different species.

-

BEndogenous soluble NR3C1 and WT1 protein levels were not altered in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing HEK293 cells. n = 3.

-

C, DBoth the NR3C1 (C) and WT1 (D) proteins showed nuclear localization in both ATXN3‐Q28‐and ATXN3‐Q84‐expressing cells. NR3C1 (C) and WT1 (D) were not detected in protein aggregate in ATXN3‐Q84‐expressing cells. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

-

EOverexpression of either ATXN3tr‐Q78 or ATXN3tr‐CAA/G78 induced the expression of Fuz protein in HEK293 cells. Such induction was not observed in cells transfected with EGFP‐CAG78 expresses only the expanded CAG transcript but not polyQ protein. n = 3.

-

FYY1ΔREPO was less effective than full‐length YY1 in suppressing Fuz induction in ATXN3tr‐Q78‐expressing cells. n = 3.

In addition to the toxic expanded polyQ protein, expanded CAG polyQ transcript also contributes to the polyQ disease pathogenesis 37. When cells were transfected with EGFP‐CAG78 that only produces the expanded polyQ transcript but not the polyQ protein, the expression of Fuz remained unchanged when compared with the unexpanded control EGFP‐CAG27. Both the CAG27/78 sequences were inserted in the untranslated region of the EGFP DNA construct 38. In contrast, when cells were transfected with the ATXN3tr‐CAA/G78 transgene which harbours a mixture of CAG and CAA glutamine codons in its polyQ‐coding domain 39, Fuz induction was still detected (Fig EV4E). The ATXN3tr‐CAA/G78 construct possesses polyQ protein toxicity and exhibits diminished CAG RNA toxicity. These results clearly demonstrate that the expanded polyQ protein, but not the expanded CAG polyQ transcript, triggers Fuz/Fuz induction.

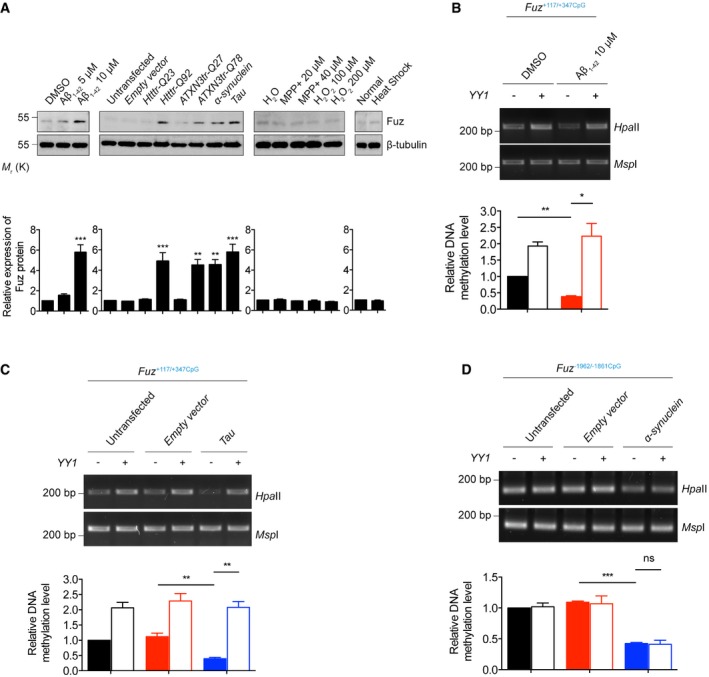

Fuz/Fuz expression is upregulated in Aβ1–42, Tau and α‐synuclein models

In addition to polyQ diseases, we detected increased level of Fuz protein in rat primary cortical neurons treated with Aβ1–42 peptide and also neurons that were transfected with Htttr‐Q92, ATXN3tr‐Q78, α‐synuclein or Tau construct (Fig 7A and Appendix Fig S2A). In contrast, no such induction was observed when neurons were treated with MPP+, a toxin that causes parkinsonism and triggers apoptotic cell death in mammals (40; Fig 7A and Appendix Fig S2B). Neither did we observe Fuz induction in neurons that had undergone oxidative stress nor heat‐shock treatment (Fig 7A and Appendix Fig S2C and D). Consistent with neuronal cell findings, Fuz/Fuz induction was observed in Aβ1–42‐treated or Tau‐/α‐synuclein‐transfected HEK293 cells (Fig EV5A–C). These results suggest that Fuz induction is triggered by toxic disease peptide/proteins.

Figure 7. Fuz protein expression and its transcriptional regulation in different stress and neurodegenerative disease conditions.

- Rat primary cortical neurons treated with Aβ1–42 peptide, or transfected with Htttr‐Q92, ATXN3tr‐Q78, α‐synuclein, Tau constructs induced Fuz protein expression. Such induction was not observed in neurons treated with MPP+, H2O2 or heat shock. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

- Overexpression of YY1 promoted the hypermethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG in the DMSO‐treated HEK293 cells. Treatment of Aβ1–42 caused hypomethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG, while such hypomethylation was restored by YY1 overexpression. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz +117/+347CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

- Overexpression of YY1 promoted the hypermethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG in the untransfected or empty vector‐transfected HEK293 cells. The Tau‐mediated hypomethylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG was rescued by YY1 overexpression. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz +117/+347CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. **P < 0.01.

- Overexpression of YY1 did not change the methylation of Fuz −1962/−1861CpG in the untransfected or empty vector‐transfected HEK293 cells. The α‐synuclein‐mediated hypomethylation of Fuz −1962/−1861CpG was not restored by YY1 overexpression. Lower panel shows the quantification of DNA methylation level of Fuz −1962/−1861CpG relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. ns represents no significant difference. ***P < 0.001.

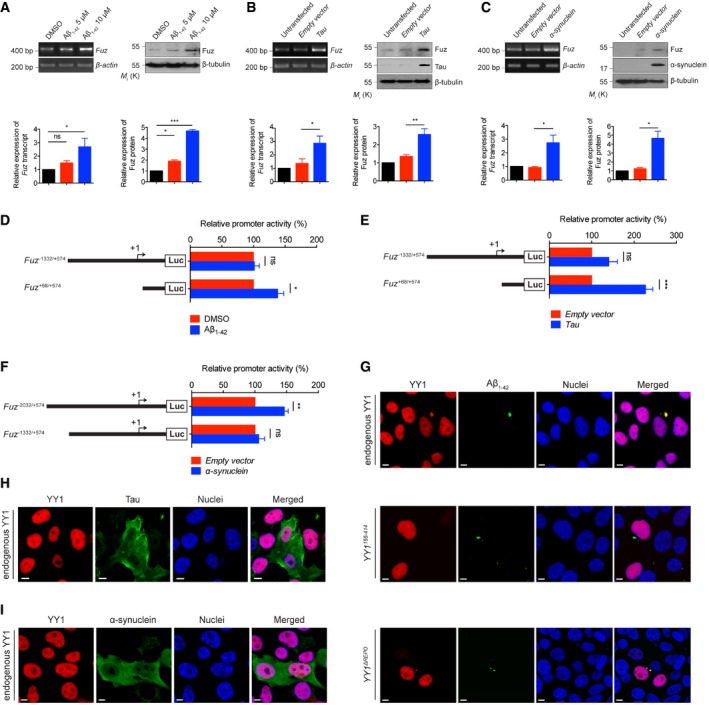

Figure EV5. Data related to Fig 7 .

- HEK293 cells treated with Aβ1–42 peptide showed induction of Fuz/Fuz at both mRNA and protein levels. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test. ns represents no significant difference. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

- HEK293 cells transfected with Tau caused an increase in the expression levels of both Fuz transcript and Fuz protein. Lower panel shows the quantification of Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

- The mRNA and protein expression of Fuz/Fuz levels were elevated in α‐synuclein‐expressing HEK293 cells. Lower panel shows the quantification of relative Fuz transcript and protein expression relative to controls. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 3. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. *P < 0.05.

- Luciferase assay was performed to examine human Fuz promoter activity in Aβ1–42‐treated HEK293 cells. The activity of Fuz +68/+574, but not Fuz −1332/+574 was upregulated in Aβ1–42‐treated cells. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 5. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ns represents no significant difference. *P < 0.05.

- Luciferase assay was performed to examine human Fuz promoter activity in Tau‐expressing HEK293 cells. Overexpression of Tau induced the transcriptional activity of Fuz +68/+574. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 5. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ns represents no significant difference. ***P < 0.001.

- Luciferase assay was performed to examine human Fuz promoter activity in α‐synuclein‐expressing HEK293 cells. The activity of Fuz −2032/+574, but not Fuz −1332/+574 was upregulated in α‐synuclein‐expressing cells. Error bars represent s.e.m., n = 5. Statistical analysis was performed using two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test. ns represents no significant difference. **P < 0.01.

- YY1 protein was sequestered to the Aβ1–42 aggregates (green) in HEK293 cells. Endogenous YY1 (red) was stained with anti‐YY1 antibody. YY1ΔREPO, but not YY1155–414 protein (red), was sequestered to the Aβ1–42 aggregates (green) in HEK293 cells. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

- YY1 protein was not sequestered to the Tau aggregates (green) in HEK293 cells. Endogenous YY1 (red) was stained with anti‐YY1 antibody. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

- The nuclear localization of YY1 was not changed in α‐synuclein‐expressing HEK293 cells. Endogenous YY1 (red) was stained with anti‐YY1 antibody. Cell nuclei (blue) were stained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bars: 5 μm. n = 3.

Fuz promoter sequence is hypomethylated in Aβ1–42, Tau and α‐synuclein models

By means of luciferase assay, we further demonstrated that the Fuz +68/+574 promoter region is responding to Aβ1–42 treatment (Fig EV5D) and Tau expression (Fig EV5E). Next, we examined whether the methylation of Fuz +117/+347CpG was altered in Aβ1–42‐treated or Tau‐expressing cells. As shown in Fig 7B and C, the Fuz +117/+347CpG was found to be less methylated upon Aβ1–42 treatment or Tau transfection. When YY1 was coexpressed, methylation status of this region was restored (Fig 7B and C).

When we further analysed the Fuz promoter, we identified another region (Fuz −2032/−1332) that is responsive to α‐synuclein expression (Fig EV5F) and found a putative CpG island (Fuz −1962/−1861CpG) within this region (Fig EV3D). We next sought to determine whether the methylation status of the Fuz −1962/−1861CpG was affected by α‐synuclein. As shown in Fig 7D, when α‐synuclein was overexpressed, this region was found to be hypomethylated. However, no predicted YY1 binding site was predicted within the Fuz −1962/−1861CpG. In line with the in silico prediction, YY1 overexpression did not alter the methylation status of Fuz −1962/−1861CpG in α‐synuclein‐expressing cells (Fig 7D).

YY1 protein colocalizes with Aβ1–42 aggregates, but its localization is not changed in Tau and α‐synuclein models

The Aβ1–42 peptide and Tau protein form aggregates 41, 42 and cause dysregulation of gene expression 43, 44. We found that endogenous YY1 was recruited to Aβ1–42 aggregates (Fig EV5G). Our colocalization study further suggests that the N‐terminal acidic and His cluster regions of YY1 play some roles in its sequestration to Aβ1–42 aggregates (Fig EV5G). In contrast, we did not observe recruitment of YY1 to Tau aggregates (Fig EV5H). Similarly, we also did not observe any change of YY1 localization pattern in α‐synuclein‐expressing cells (Fig EV5I). How Fuz transcriptional control is affected in Tau‐ and α‐synuclein‐mediated neurotoxicity warrants further investigation.

Discussion

This study unveiled a previously undescribed role of Fuz, a PCP effector, in the pathogenesis of multiple neurodegenerative diseases (Fig 8). We showed that Fuz, when overexpressed, triggers apoptosis in neuronal cells by activating the Dvl/Rac1 GTPase/MEKK1/JNK/caspase signalling pathway (Fig 1A–K). Elevated level of Fuz expression was observed in cell models expressing Htttr‐Q92 (Figs 7A and EV2A), ATXN3tr‐Q78 (Figs 7A and EV2B), Tau (Figs 7A and EV5B), α‐synuclein (Figs 7A and EV5C) or treated with Aβ1–42 peptide (Figs 7A and EV5A). Furthermore, our data demonstrate that Fuz promoter was hypomethylated in cells transfected with ATXN3tr‐Q78, α‐synuclein, and Tau, as well as Aβ1–42 peptide‐treated cells (Figs 5F and 7B–D). All these conditions lead to the transcriptional upregulation of Fuz gene expression.

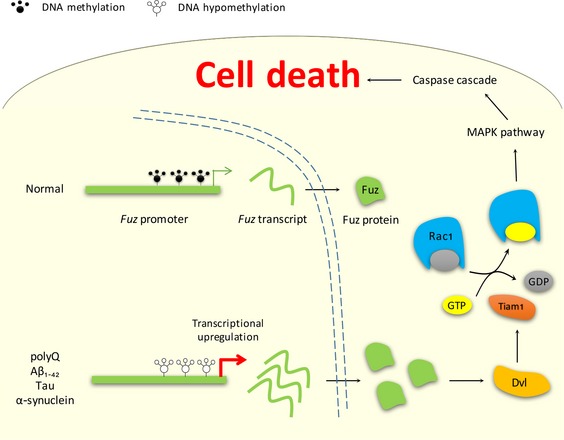

Figure 8. Model of Fuz‐induced apoptosis in polyQ, Aβ1–42, Tau and α‐synuclein models.

In normal condition, Fuz promoter is methylated. In polyQ, Aβ1–42, Tau and α‐synuclein models, Fuz promoter is hypomethylated, and this results in transcriptional upregulation of Fuz. The accumulation of Fuz protein in turn stimulates the downstream Dvl/Rac1 GTPase/MAPK/caspase signalling pathway and induces neuronal cell death.

Tabler et al 45 observed the overproduction of neural crest cells in Fuz −/− embryos and that Fuz mutant mice display excessive cell proliferation 21. These findings highlight the role of Fuz in the regulation of cell survival and proliferation. Dishevelled is responsible for transducing Wnt signals to downstream pathways including PCP signalling 46. Genetically, Fuz acts as a downstream effector of Dvl 3. More recently, it was reported that Fuz could modulate the subcellular distribution of Dvl to regulate PCP 25, indicating Fuz can regulate its downstream pathways via Dvl. In addition to the classical roles of Dvl and Fuz in PCP 1, our study discovered a previously undescribed function of Fuz in activating apoptotic signalling (Fig 1K). Fuz promotes the formation of Dvl “punctae” (Fig EV1E), which in turn triggers the Rac1 GTPase/MEKK1/JNK/caspase signalling axis to mediate apoptotic cell death (Fig 1A–K). Interestingly, knockdown of other PCP genes, including Inturned, Fritz and Flamingo, did not affect Fuz‐induced caspase‐3 cleavage (Fig EV1I–K). This strongly suggests that Fuz‐induced apoptosis is independent of the PCP signalling pathway, but may specifically involve the pro‐apoptotic functions of Dvl 47. Since the regulation of apoptosis by Dvl involves the canonical Wnt signalling pathway 48, future investigations may examine the involvement of molecules such as GSK3β and β‐catenin in Fuz‐induced apoptosis.

We previously reported that the downregulation of pre‐45S ribosomal RNA expression in polyQ diseases can be caused by rDNA hypermethylation 38. By contrast, here we observed that Fuz promoter is hypomethylated in polyQ diseases (Fig 5F). Furthermore, hypomethylation of the Fuz promoter was also observed in Aβ1–42 peptide‐treated cells (Fig 7B), as well as in cells transfected with Tau (Fig 7C) and α‐synuclein (Fig 7D), suggesting that Fuz hypomethylation may be a common pathogenic feature in multiple neurodegenerative diseases. Epigenetic regulation of gene transcription is reversible 49, and our findings highlight that targeted reversal of the pathologic epigenome would be a viable therapeutic strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases in general.

Polyglutamine protein aggregation is a pathological hallmark of polyQ diseases 9. Various cellular regulators, including transcriptional factors, are recruited to these aggregated macromolecular structures. Protein aggregates deplete the cellular activities of the sequestered cellular proteins and contribute to the neurotoxicity observed in polyQ diseases 50. Alteration of cellular gene expression has widely been reported in polyQ diseases 51, 52, 53. The sequestration of transcriptional factors to polyQ protein aggregates can downregulate the expression of cellular genes 54, 55, 56. In this study, we are intrigued to have discovered a significant reduction of protein expression of a Fuz transcriptional repressor, YY1, in SCA3 patients (Fig 6A and B). We observed the recruitment of YY1 to polyQ protein aggregates in our SCA3 cell model (Fig 6D) and further demonstrated that the REPO domain is required for the recruitment of YY1 into polyQ protein aggregates (Fig 6F). The REPO domain is known for the recruitment of the polycomb group proteins into a multimeric protein complex required for transcriptional silencing 34. When we examined whether the deletion of the REPO domain would disrupt YY1's function in suppressing Fuz induction in SCA3 cell model, as expected we found that YY1ΔREPO was less effective than full‐length YY1 in suppressing the expanded polyQ‐induced upregulation of Fuz (Fig EV4F). This indicates that the REPO domain is not only required for the recruitment of YY1 into polyQ protein aggregates, but it is also important for YY1 to suppress Fuz upregulation in polyQ diseases.

In addition to the suppression of Fuz upregulation, overexpression of YY1 also suppressed apoptosis in neurons expressing the expanded polyQ protein (Fig EV3F). A range of studies indicate that the function of YY1 is perturbed during neurodegeneration 57, 58. Our results unveil a new role of YY1 in polyQ pathogenesis, as demonstrated by the findings that deprivation of functional YY1 protein by expanded polyQ protein causes derepression of Fuz transcription, followed by the induction of neuronal apoptosis. Moreover, we found that the Fuz +117/+347CpG is responsive to multiple toxic protein insults, including expanded polyQ, Aβ1–42 and Tau (Appendix Table S1). In AD brains, YY1 protein was found to have undergone proteolytic cleavage, which results in the reduction of full‐length YY1 protein level 59. This is a plausible explanation to Fuz upregulation in Aβ1–42‐treated cells (Fig EV5A).

Our result indicates that the α‐synuclein protein activates Fuz transcription via a different promoter region (Fuz −1962/−1861CpG; Appendix Table S1). Although α‐synuclein also induces Fuz promoter hypomethylation, it could not be restored by YY1 coexpression (Fig 7D), indicating other transcriptional regulatory factors may be involved. In silico analysis of this region identified a putative forkhead box A1 (FOXA1) transcriptional factor binding site in the Fuz −1962/−1861CpG. FOXA1 has been implicated in the maintenance of dopaminergic neurons 60, and its expression also regulates the methylation of DNA sequences 61. Further investigations would be needed to verify the involvement of FOXA1 in Fuz transcription regulation in α‐synuclein‐expressing cells.

In conclusion, our study shows that Fuz promoter is hypomethylated in expanded polyQ‐, α‐synuclein‐, Tau‐expressing and Aβ1–42‐treated cells. Instead of invoking the downregulation of pro‐survival gene expression 62, 63, 64, we provide an alternative mechanistic explanation to how the transcriptional derepression of a pro‐apoptotic gene can participate in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders.

Materials and Methods

Plasmids

The pcDNA3.1‐Tau‐2N4R‐V5/His 65, pcDNA3.1(+)‐ATXN3tr‐Q27/Q78 66, pcDNA3.1(+)‐ATXN3tr‐CAA/G78 38, pEGFP‐CAG27/78 38, pCMV‐Tag2B‐Htttr‐Q23/Q92 67 and pcDNA3.1(+)‐Q19/Q81‐EGFP‐myc constructs 66 were described previously. pRK5‐Rac1 T17N was a gift from Gary Bokoch (Addgene plasmid # 12984). pCDNA3.1(zeo)‐Dvl was a gift from Randall Moon (Addgene plasmid # 16758). pmCherry‐N1 was a gift from Michael Davidson (Addgene plasmid # 54517). pEGFP‐ATXN3‐Q28/Q84 were gifts from Henry Paulson (Addgene plasmids # 22122 and 22123) 68. pCMV6‐Inturned (RC218556), pCMV6‐Fritz (RC210824) and pCMV6‐Flamingo (RC211860) were purchased from OriGene Technologies. pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] and pTK‐RL were purchased from Promega. To generate the pcDNA3.1(+)‐flag‐α‐synuclein, the α‐synuclein DNA sequence was amplified from HEK293 cDNA template using primers KpnI‐flag‐asyn‐F, 5′‐GGGGTACCATGGATTACAAGGACGATGACGATAAGATGGATGTATTCATGAAAGGAC‐3′ and NotI‐asyn‐R, 5′‐ATTTGCGGCCGCTTAGGCTTCAGGTTCGTAGTC‐3′. The DNA fragment was subsequently subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) vector (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using KpnI and NotI. To generate the pcDNA3.1(+)‐flag‐Fuz, the Fuz DNA sequence was amplified from HEK293 cDNA template using primers EcoRI‐flag‐Fuz‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGATTACAAGGATGACGACGATAAGATGGGGGAGGAGGGGAC‐3′ and XhoI‐Fuz‐R, 5′‐CCGCTCGAGTCAAAGAAGTGGGGTGAG‐3′. The respective DNA fragments were then subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) vector using EcoRI and XhoI. To generate the pFuz‐EGFP, the Fuz DNA sequence was amplified from HEK293 cDNA template using primers EcoRI‐Fuz‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGGGGAGGAGGGGAC‐3′ and KpnI‐Fuz‐R, 5′‐CCGGGTACCGTAAGAAGTGGGGTGAGG‐3′. The resultant DNA fragments were subcloned into pEGFP‐N1 vector (Clontech Laboratories) using EcoRI and KpnI. To generate the pcDNA3.1(+)‐Human YY1‐myc and pcDNA3.1(+)‐Rat YY1‐myc, the human and rat YY1 DNA sequences were amplified from HEK293 and rat primary cortical neuron cDNA templates, respectively. The primers used were EcoRI‐YY1‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGCCTCGGGCGACAC‐3′ and XhoI‐myc‐YY1‐R, 5′‐CCGCTCGAGTCACAGATCCTCTTCTGAGATGAGTTTTTGTTCCTGGTTGTTTTTGGC‐3′. The DNA fragments were subsequently subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) vector using EcoRI and XhoI. To generate YY1 deletion constructs, the YY1 155–414 and YY1 227–414 DNA sequences were amplified from HEK293 cDNA template using primers EcoRI‐YY1‐155‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGCGGCCGGCAAGAG‐3′; EcoRI‐YY1‐227‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGATGAAAAAAAAGATATTG‐3′; and KpnI‐YY1‐R, 5′‐CCGGGTACCGTCTGGTTGTTTTTGGC‐3′. The resultant DNA fragments were subcloned into pmCherry‐N1 vector using EcoRI and KpnI to generate the pYY1 155–414 ‐mCherry and pYY1 227–414 ‐mCherry. Overlapping PCR method was used to generate the YY1 ΔREPO sequence, and the resultant DNA fragment was subcloned into pmCherry‐N1 vector using EcoRI and KpnI to generate the pYY1 ΔREPO ‐mCherry. Primers used for overlapping PCR were EcoRI‐YY1‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGCCTCGGGCGACAC‐3′; YY1 ΔREPO ‐R, 5′‐CTTTTTTTTCATCGTTGCCCGG‐3′; YY1 ΔREPO ‐F, 5′‐GGCGCCGACGATGAAAAAAAAG‐3′; and KpnI‐YY1‐R, 5′‐CCGGGTACCGTCTGGTTGTTTTTGGC‐3′. To generate pcDNA3.1(+)‐YY1 ΔREPO ‐myc, the YY1 ΔREPO DNA sequence was amplified from pYY1 ΔREPO ‐mCherry using primers EcoRI‐YY1‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGGCCTCGGGCGACAC‐3′ and XhoI‐myc‐YY1‐R, 5′‐CCGCTCGAGTCACAGATCCTCTTCTGAGATGAGTTTTTGTTCCTGGTTGTTTTTGGC‐3′. The resultant DNA fragment was subsequently subcloned into pcDNA3.1(+) vector using EcoRI and XhoI. The −2032 to +574, −1332 to +574 and +68 to +574 human Fuz promoter DNA sequences were amplified from HEK293 genomic DNA template using primers NheI‐Fuz Promoter −2032‐F, 5′‐CCGGCTAGCTTTGTTCTTGTTGCCCAGGC‐3′; NheI‐Fuz Promoter −1332‐F, 5′‐CCGGCTAGCGCACTTTGAGAGGCTGAGGT‐3′; NheI‐Fuz Promoter +68‐F, 5′‐CCGGCTAGCGTTAATCCTCTTCCAATCAG‐3′ and BglII‐Fuz Promoter‐R, 5′‐CCGAGATCTCTAAGGAGGGGTTAGGG‐3′. The resultant DNA fragments were subcloned into pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] luciferase vector using NheI and BglII to generate the pGL4.17‐Fuz −2032/+574, pGL4.17‐Fuz −1332/+574 and pGL4.17‐Fuz +68/+574. Overlapping PCR method was used to generate the Fuz promoter −1332/+574 YY1 mutant sequence, and the resultant DNA fragment was subcloned into pGL4.17[luc2/Neo] luciferase vector using NheI and BglII to generate the pGL4.17‐Fuz −1332/+574 YY1 mutant. Primers used for overlapping PCR were NheI‐Fuz Promoter −1332‐F, 5′‐CCGGCTAGCGCACTTTGAGAGGCTGAGGT‐3′; YY1 mutant‐F, 5′‐GAGTCCTAAACGGGGGAGGAG‐3′; YY1 mutant‐R, 5′‐CTCCTCCCCCGTTTAGGACTC‐3′; and BglII‐Fuz Promoter‐R, 5′‐CCGAGATCTCTAAGGAGGGGTTAGGG‐3′.

Cell cultures and transfection

The SCA3 patient fibroblasts (GM06151) 69 were obtained from the NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research. The unaffected control fibroblasts (AG04351) 38 were obtained from the NIA Aging Cell Culture Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research. The Fuz −/− HEK293 cell line was generated by GenScript using the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system. The targeting guide RNA sequence used was 5′‐ACTGACCAATATCCGCAACG‐3′. The mutant Fuz locus was PCR‐amplified from the CRISPR‐targeted cell clones and sequenced. The resultant Fuz −/− clones were confirmed to carry a homozygous 1‐bp insertion mutation in the coding region of endogenous Fuz locus. This insertion introduces a premature stop codon after the Arg 171 position. Both the HEK293 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fibroblasts were cultured using DMEM (GE Healthcare BioSciences) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The cells were maintained in a 37°C humidified cell culture incubator supplemented with 5% CO2. Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used in plasmid and siRNA transfection, respectively. For gene knockdown experiments, all ON‐TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNAs were purchased from GE Healthcare BioSciences. In this study, 40 pmol of MEKK1‐siRNA (L‐003575‐00‐0005), 20 pmol of Tiam1‐siRNA (L‐003932‐00‐0005), 20 pmol of Dvl‐siRNA (L‐004070‐00‐0005), 20 pmol of Inturned‐siRNA (L‐031873‐01‐0005), 40 pmol of Fritz‐siRNA (L‐020947‐02‐0005), 40 pmol of Flamingo‐siRNA (L‐005460‐00‐0005), 20 pmol of human Fuz‐siRNA (L‐016342‐02‐0005), 60 pmol of rat Fuz‐siRNA (L‐082437‐02‐0005) and 5 pmol of YY1‐siRNA (L‐011796‐00‐0005) were used to knockdown the respective gene expression. Non‐targeting siRNA (D‐001210‐01‐50) was used as control. Rat primary cortical neurons were isolated and cultured as previously reported 70. Neurons were incubated with 3 μg of plasmids or 60 pmol of siRNAs in primary neuron transfection reagent (VVPG‐1003, Lonza). Neurons were transfected using Amaxa Nucleofection system (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The SCA3 patient fibroblasts (GM06153) 71 were obtained from the NIGMS Human Genetic Cell Repository at the Coriell Institute for Medical Research. The SCA3 fibroblasts and unaffected control fibroblasts (AG04351) were reprogrammed with the Yamanaka factors, Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c‐Myc using the Sendai virus delivery system. The reprogramming protocol was performed according to manufacturer's instructions (CytoTune®‐iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) at passage 12 were further induced to neural progenitor cells using the STEMdiff™ Neural Induction Medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Inc.). Induced neural progenitor cells (iNPCs) were maintained in STEMdiff™ Neural Progenitor Medium (STEMCELL Technologies, Inc.) and used for experiments at passage 4. For the characterization of iNPC cells, RNAs were extracted from cells, followed by quantitative PCR to determine the expression of Nestin. The primers used were Nestin‐F, 5′‐GTCTCAGGACAGTGCTGAGCCTTC‐3′ and Nestin‐R, 5′‐TCCCCTGAGGACCAGGAGTCTC‐3′.

Drosophila stocks

All fly crosses were set up in a 21.5°C incubator. Fly lines UAS::ATXN3fl‐Q27/Q84 27, gmr::Gal4 72 and UAS::Httexon1‐Q93 73 were described previously. The UAS::fy‐dsRNA line (KK100638) was obtained from Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center, and the fy 3 line (8875) 3 was obtained from Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Mouse strain

The SCA3 transgenic mouse strain B6;CBA‐Tg(ATXN3*)84.2Cce/IbezJ 74 (012705) was obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Genotyping was performed using the genomic DNA isolated from tail biopsy. Primers used for genotyping were Mouse MJD‐F, 5′‐ACAATGACACGATGTTGGCT‐3′; Mouse MJD‐R, 5′‐AAACAAATATTCGCCAGGTGTAG‐3′; Mouse GAPDH‐F, 5′‐ACATCATCCCTGCATCCACTG‐3′; and Mouse GAPDH‐R, 5′‐ACAACCTGGTCCTCAGTGTA‐3′. Whole‐brain samples were collected from homozygous SCA3 transgenic mice at 6 months of age. All animal procedures were conducted with the approval of the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Human brain samples

Brain tissues from five SCA3 patients were obtained from the NIH NeuroBioBank at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD. Brain tissues from one SCA3 case and six age‐matched controls were obtained through the New York Brain Bank, Columbia University, New York, NY. Background information including age, gender and post‐mortem interval of controls and SCA3 cases are listed in Appendix Tables S2 and S3. Brain tissues were homogenized in SDS sample buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol). Protein concentration was determined using Bradford Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The homogenate was heated at 99°C for 10 min. A total of 60 μg of each sample was used for immunoblotting.

Human TissueScan cDNA arrays

Human brain tissue cDNA array (HBRT301, OriGene Technologies) and human normal tissue cDNA array (HMRT304, OriGene Technologies) were used to determine the expression profile of Fuz in humans. The qPCR was performed using an ABI 7500 real‐time PCR system. The following TaqMan probes were used Fuz (Assay ID: Hs01547302_m1), beta‐actin (Assay ID: Hs99999903_m1). Relative expression of Fuz was normalized against beta‐actin using the 2−ΔCT method.

RNA isolation and RT–PCR

TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to extract RNA from mammalian cells, adult fly heads and mouse brains. Two micrograms of RNA was used for reverse transcription using the ImProm‐II™ Reverse Transcription System (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primers used in this study were Human Fuz‐F, 5′‐CCGGAATTCATGCCCCTTCACACAGACATC‐3′; Human Fuz‐R, 5′‐CCGGGTACCGTTCAAAGAAGTGGGGTGAGG‐3′; YY1‐F, 5′‐TCAGATTCTCATCCCGGTGC‐3′; YY1‐R, 5′‐ACTCTTCTTGCCGCTCTTCT‐3′; Actin‐F, 5′‐ATGTGCAAGGCCGGTTTCGC‐3′; Actin‐R, 5′‐CGACACGCAGCTCATTGTAG‐3′; Drosophila fuzzy‐F, 5′‐CACATGCCATGAGTGCCTAC‐3′; Drosophila fuzzy‐R, 5′‐TATTAGCATGGATGCGTTGC‐3′; Drosophila ATXN3‐polyQ‐F, 5′‐CGCGGATCCAAAAACAGCAGCAAAAGC‐3′; Drosophila ATXN3‐polyQ‐R, 5′‐CGCACCGGTTCTGTCCTGATAGGTCC‐3′; Mouse Fuz‐F, 5′‐CCCGTCAACAGCTTCCTTTC‐3′; and Mouse Fuz‐R, 5′‐CCAGGAAGCTGTCGATGAGA‐3′.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at 37°C. Ice‐cold 1× PBS was used to wash cells twice. Binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 142.5 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma‐Aldrich) was then added to the samples. Sonication was applied to lyse the cells (Duty Cycle 30, Output Control 3, Timer 30 s, Sonifier 450, Branson Ultrasonics), and the samples were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. The samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 30 min at 14,000 × g. A fraction of the supernatant was saved as “Input”. The dynabeads protein G (10004D, Thermo Fisher Scientific), together with anti‐YY1 antibody (ab109237, Abcam), was quickly added to the remaining samples, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight with gentle rotation. The subsequent washing and elution procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (ChIP Assay Kit, Merck Millipore). The recovered genomic DNA was analysed by PCR using the primers Fuz ‐802‐F, 5′‐TTGTCACATCCATAAAATAG‐3′; Fuz ‐612‐R, 5′‐TACCATGTAAAATGTGAAAAATC‐3′; Fuz +117‐F, 5′‐GACCACAGGCCGAGTTACTC‐3′; and Fuz +347‐R, 5′‐TTCGGTTTAGATACAGGCGTC‐3′.

In vitro DNA binding assay

In vitro DNA binding assay was performed as previously described 75. In brief, Fuz promoter‐containing DNA fragments were PCR‐amplified from pGL4.17‐Fuz −1332/+574 and pGL4.17‐Fuz −1332/+574 YY1 mutant constructs, respectively. The primers used were Fuz +117‐F, 5′‐GACCACAGGCCGAGTTACTC‐3′ and Fuz +347‐R, 5′‐TTCGGTTTAGATACAGGCGTC‐3′. Five nanograms of wild‐type and YY1 mutant DNAs was independently mixed with 400 ng of YY1 protein (ab187479, Abcam), 0.4 μg of anti‐YY1 antibody (ab109237, Abcam) and 40 μl of dynabeads protein G (10004D, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 500 μl binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 142.5 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100). The mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight with gentle rotation. Prior to elution, the protein/DNA mixture was washed with binding buffer for five times. The recovered genomic DNA was analysed by PCR using the primers Fuz +117‐F, 5′‐GACCACAGGCCGAGTTACTC‐3′ and Fuz +347‐R, 5′‐TTCGGTTTAGATACAGGCGTC‐3′.

Protein sample preparation, immunoblot analysis and antibodies used in this study

Proteins were extracted from HEK293 cells or rat primary cortical neurons using SDS sample buffer. For protein extraction from mice, half of the brain was homogenized in protein lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 10% NP‐40, 5% sodium deoxycholate). All protein samples were boiled at 99°C for 10 min, prior to immunoblot analysis. Primary antibodies used were anti‐cleaved caspase‐3 (9664, 1:500), anti‐p‐JNK (9251, 1:500), anti‐JNK (9252, 1:1,000), anti‐myc (2276, 1:2,000) from Cell Signaling Technology; anti‐p‐MEKK1 (ab138662, 1:1,000), anti‐MEKK1 (ab69533, 1:1,000), anti‐Fuz (ab111842, 1:500), anti‐WT1 (ab89901, 1:1,000), anti‐Flamingo (ab90817, 1:500), anti‐YY1 (ab109237, 1:1,000), anti‐beta‐tubulin (ab6046, 1:2,000) from Abcam; anti‐Tiam1 (sc‐393315, 1:100), anti‐dishevelled (sc‐8027, 1:200), anti‐NR3C1 (sc‐56851, 1:500) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti‐Inturned (LS‐C169884‐50, 1:500) from LifeSpan BioSciences; anti‐Fritz (PA524271, 1:500) from Thermo Fisher Scientific; anti‐ATXN3 (MAB5360, 1:500) from Merck Millipore; anti‐polyglutamine (P1874, 1:1,000), anti‐flag (F3165, 1:500), anti‐HA (H3663, 1:500) and anti‐His (27‐4710‐01, 1:1,000) from Sigma‐Aldrich; anti‐Hsp70 (SPA‐812C, 1:1,000) from Enzo Life Sciences. Secondary antibodies used for immunoblot analyses were goat anti‐rabbit (11‐035‐045, 1:5,000) and goat anti‐mouse (115‐035‐062, 1:10,000) from Jackson ImmunoResearch.

Co‐immunoprecipitation assay

Cells were washed once with ice‐cold 1× PBS. Binding buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 5 mM MgCl2, 142.5 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X‐100) supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma‐Aldrich) was then added to the samples. Sonication was applied to lyse the cells (duty cycle 30, output control 3, timer 30 s, Sonifier 450, Branson Ultrasonics), and the samples were incubated at 4°C for 1 h with rotation. The samples were centrifuged at 4°C for 20 min at 14,000 × g. A fraction of the supernatant was saved as “Input”. The dynabeads protein G (10004D, Thermo Fisher Scientific), together with anti‐flag antibody (2368, Cell Signaling Technology) was quickly added to the remaining samples, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight with gentle rotation. On the following day, the beads were washed for three times with binding buffer and then resuspended in SDS sample buffer. All protein samples were boiled at 99°C for 10 min, prior to immunoblot analysis. The Dvl and flag‐Fuz were detected using anti‐Dvl (sc‐8027, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti‐flag (F3165, Sigma‐Aldrich) antibodies, respectively.

Drug and peptide treatments

Pan‐caspase inhibitor Z‐VAD‐FMK (Enzo Life Sciences) was used at 20 μM, and the treatment lasted for 48 h. The JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Merck Millipore) was used at 10, 30 or 50 μM, and the treatment lasted for 24 h. The DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5‐azacytidine (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used at 50 μM, and the treatment lasted for 8 h. The MPP+ (Sigma‐Aldrich) was used at 20 or 40 μM, and the treatment lasted for 48 h. The H2O2 (Merck Millipore) was used at 100 or 200 μM, and the treatment lasted for 48 h. The Aβ1–42 was pre‐incubated at 37°C for 1 h before used at 5 or 10 μM, and the treatment lasted for 24 h. The fluorescently labelled Aβ1–42 (AS‐60479‐01, AnaSpec) was prepared as previously described 76. The working concentration was 2 μM, and the treatment lasted for 24 h.

Heat‐shock treatment

Heat shock was performed by placing the rat primary cortical neurons at 42°C for 2 h. The neurons were then recovered at 37°C for 24 h.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

For HEK293 cells, LDH assay was performed 72 h post‐transfection. For rat primary cortical neurons, LDH assay was performed 96 h post‐transfection. The procedures were performed according to manufacturer's instructions (CytoTox 96 Non‐Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay Kit, Promega).

Terminal Deoxynucleotidyl Transferase dUTP Nick End Labelling (TUNEL) assay

Forty‐eight hours post‐transfection, HEK293 cells were fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde. The remaining procedures were performed according to manufacturer's instructions (APO‐BrdU™ TUNEL Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell images were acquired on an Olympus IX‐81 FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus) using a 20× objective lens and Olympus Fluoview software (version 4.2a).

Rac1 activation assay

For the Rac1 activation assay, HEK293 cells were harvested 24 h post‐transfection. The subsequent procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (RhoA/Rac1/Cdc42 Activation Assay Combo Kit, Cell Biolabs).

Luciferase assay

Cell culture medium was removed 24 h post‐transfection, and the following procedures were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Dual‐Glo Luciferase Assay Kit, Promega). The firefly and Renilla luminescence were detected using a luminometer (Tecan). The relative luciferase activity was determined by calculating the ratio between firefly and Renilla luminescence.

HpaII DNA methylation assay

HpaII DNA methylation assay was performed as previously described 38. The primers used were Fuz +117‐F, 5′‐GACCACAGGCCGAGTTACTC‐3′; Fuz +347‐R, 5′‐TTCGGTTTAGATACAGGCGTC‐3′; Fuz −1962‐F, 5′‐TTCAAGCGATTATCCTGC‐3′; Fuz −1861‐R, 5′‐GAGAAACCCCGGCTCTAC‐3′; Rat Fuz +50‐F, 5′‐TCCAAACAGCAGGCCACTTTG‐3′; and Rat Fuz +312‐R, 5′‐GCATGTATGCAGTCCCAGCTTC‐3′.

Immunocytochemistry

The HEK293 cells were seeded on cover slip (Marienfeld‐Superior). Cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde. The primary and secondary antibodies used were anti‐NR3C1 (1:200; sc‐56851, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti‐WT1 (1:400; ab89901, Abcam), anti‐YY1 antibody (1:400; ab109237, Abcam), anti‐flag (1:200; F3165, Sigma‐Aldrich), anti‐His antibody (1:200; 27‐4710‐01, Sigma‐Aldrich), goat anti‐mouse IgG (H+L) FITC conjugate (1:400; Zymed), goat anti‐mouse IgG (H+L) Cy3 conjugate (1:400; Zymed) and goat anti‐rabbit IgG (H+L) Cy3 conjugate (1:400; Zymed), respectively. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (1:400; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell images were acquired on an Olympus IX‐81 FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus) using a 63× water immersion objective lens and Olympus Fluoview software (version 4.2a). For the iNPC characterization, the primary and secondary antibodies used were anti‐Nestin antibody (1:200; sc‐1703, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and goat anti‐mouse IgG (H+L) Cy3 conjugate (1:400; Zymed), respectively. The cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (1:400; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Cell images were acquired on an Olympus IX‐81 FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus) using a 20× objective lens and Olympus Fluoview software (version 4.2a). Ten micromolar of CM‐H2DCFDA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was added to H2O2‐treated rat primary cortical neurons to monitor reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and ROS was detected after a 30‐min incubation at 37°C. The images were acquired on an Olympus IX‐81 FV1000 confocal microscope (Olympus) using a 20× objective lens and Olympus Fluoview software (version 4.2a).

Pseudopupil assay

Pseudopupil assay was performed as previously described 77. The images of ommatidia were captured by a SPOT Insight CCD camera (Diagnostic Instruments Inc.), and all images were processed using the SPOT Advanced software (version 5.2; Diagnostic Instruments, Inc.) and Adobe Photoshop 7.0 software. For each control or experimental group, a total of 200 ommatidia collected from 20 fly eyes were examined. The average number of rhabdomeres from each ommatidia was used to determine ommatidial integrity.

Statistical analyses

The two‐tailed, unpaired Student's t‐test and one‐way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test were applied to determine the difference between each group. *, ** and *** represent P < 0.05, P < 0.01 and P < 0.001, respectively, which are considered statistically significant.

Data and software availability

Fuz and fuzzy promoter sequences are deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers NG_032843 and NT_033779.5. The intensity of the protein or DNA bands were quantified using the ImageJ software (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) 78. Transcription factor binding sites were predicted using the ConSite (http://consite.genereg.net/) 79, Transcription factor affinity prediction (http://trap.molgen.mpg.de/cgi-bin/trap_form.cgi) 80 and PROMO (http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3) 81 softwares. The CpG islands were predicted using the MethPrimer (http://www.urogene.org/methprimer/) 82 software.

Author contributions

ZSC and HYEC planned the study and designed the experiments. ZSC, FMC, LL, XL, WL, SP, and QZ carried out the experiments and analyses. YA, ZSC, HYEC, T‐FC, ACK, KMK, K‐FL, JCKN, and WTW interpreted the results. ZSC, ACK, and HYEC wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix

Expanded View Figures PDF

Source Data for Expanded View and Appendix

Review Process File

Source Data for Figure 1

Source Data for Figure 2

Source Data for Figure 3

Source Data for Figure 4

Source Data for Figure 5

Source Data for Figure 6

Source Data for Figure 7

Acknowledgements

We thank former and present members of the Laboratory of Drosophila Research for insightful comments and discussion. We are grateful to Dr. S.H. Kuo and Dr. P.L. Faust from Columbia University for providing human brain samples. Human SCA3 tissue was obtained from the NIH Neurobiobank at the University of Maryland. Control brain tissue and one SCA3 case were obtained from the New York Brain Bank, Columbia University. Control and SCA3 iPSCs were generated by Dr. J.J. Kim from the Human Stem Cell Core at Baylor College of Medicine. This work was supported by the General Research Fund (14100714) of the Hong Kong Research Grants Council; CUHK Vice‐Chancellor's One‐Off Discretionary Fund (VCF2014011); CUHK One‐off Funding for Joint Lab/Research Collaboration (3132980); CUHK Faculty of Science Strategic Development Fund (FACULTY‐P17173); CUHK Gerald Choa Neuroscience Centre (7105306); and donations from Chow Tai Fook Charity Foundation (6903898) and Hong Kong Spinocerebellar Ataxia Association (6903291).

EMBO Reports (2018) 19: e45409

References

- 1. Butler MT, Wallingford JB (2017) Planar cell polarity in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 18: 375–388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Axelrod JD, Miller JR, Shulman JM, Moon RT, Perrimon N (1998) Differential recruitment of dishevelled provides signaling specificity in the planar cell polarity and wingless signaling pathways. Genes Dev 12: 2610–2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Collier S, Gubb D (1997) Drosophila tissue polarity requires the cell‐autonomous activity of the fuzzy gene, which encodes a novel transmembrane protein. Development 124: 4029–4037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Devenport D (2014) The cell biology of planar cell polarity. J Cell Biol 207: 171–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ohata S, Nakatani J, Herranz‐Perez V, Cheng J, Belinson H, Inubushi T, Snider WD, Garcia‐Verdugo JM, Wynshaw‐Boris A, Alvarez‐Buylla A (2014) Loss of dishevelleds disrupts planar polarity in ependymal motile cilia and results in hydrocephalus. Neuron 83: 558–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gray RS, Abitua PB, Wlodarczyk BJ, Szabo‐Rogers HL, Blanchard O, Lee I, Weiss GS, Liu KJ, Marcotte EM, Wallingford JB et al (2009) The planar cell polarity effector Fuz is essential for targeted membrane trafficking, ciliogenesis and mouse embryonic development. Nat Cell Biol 11: 1225–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Seo JH, Zilber Y, Babayeva S, Liu J, Kyriakopoulos P, De Marco P, Merello E, Capra V, Gros P, Torban E (2011) Mutations in the planar cell polarity gene, Fuzzy, are associated with neural tube defects in humans. Hum Mol Genet 20: 4324–4333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Adegbuyiro A, Sedighi F, Pilkington AW IV, Groover S, Legleiter J (2017) Proteins containing expanded polyglutamine tracts and neurodegenerative disease. Biochemistry 56: 1199–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kuiper EF, de Mattos EP, Jardim LB, Kampinga HH, Bergink S (2017) Chaperones in polyglutamine aggregation: beyond the Q‐stretch. Front Neurosci 11: 145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orr HT, Zoghbi HY (2007) Trinucleotide repeat disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci 30: 575–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan HC, Ho LI, Chi CS, Chen SJ, Peng GS, Chan TM, Lin SZ, Harn HJ (2014) Polyglutamine (PolyQ) diseases: genetics to treatments. Cell Transplant 23: 441–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Everett CM, Wood NW (2004) Trinucleotide repeats and neurodegenerative disease. Brain 127: 2385–2405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Elmore S (2007) Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol Pathol 35: 495–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]