Abstract

Distinct female castes produced from one genotype are the trademark of a successful evolutionary invention in eusocial insects known as reproductive division of labour. In honey bees, fertile queens develop from larvae fed a complex diet called royal jelly. Recently, one protein in royal jelly, dubbed Royalactin, was deemed to be the exclusive driver of queen bee determination. However, this notion has not been universally accepted. Here I critically evaluate this line of research and argue that the sheer complexity of creating alternate phenotypes from one genotype cannot be reduced to a single dietary component. An acceptable model of environmentally driven caste differentiation should include the facets of dynamic thinking, such as the concepts of attractor states and genetic hierarchical networks.

In honeybees, genotypically identical females develop into queens or sterile workers, depending on their diets. In this review, Ryszard Maleszka discusses the controversial role of the royal jelly protein Royalactin in caste determination and provides a framework for moving beyond the master inducer concept.

Introduction

Many organisms have the capacity to produce contrasting organismal outcomes from one genotype using intricate developmental cues1–3. This captivating biological phenomenon known as phenotypic plasticity is found in both plants and animals, particularly in insects, and is considered one of the most interesting albeit poorly understood properties of biological systems. The original concept was used to describe developmental effects on morphological characters1,4, but more recently has been broadly applied to all phenotypic responses to environmental change5,6. Numerous cellular mechanisms generating confined or systemic responses are required to accomplish plasticity, including gene transcription and translation, epigenomic modifications, metabolic modulation and hormonal regulation5–12. The phasing, specificity and pace of plastic responses are essential for their adaptive value. The particular case when variations in environment induce discrete phenotypes is termed polyphenism, which finds its most striking representation in eusocial insects, such as ants and honey bees2,5,6,13.

In advanced social honey bees (Apis mellifera) one genetic blueprint is used to produce two types of females by utilising nutritional cues from two distinct feeding regimes7,14,15. Following an inflexible embryonic development, newly hatched female larvae are multipotent and can develop either into short-lived functionally sterile workers or long-lived fertile queens with both organisms showing distinct phenotypic features, such as different sensory organs, hind legs, body size, ovaries, etc.16. Initially, not only the queen-destined larvae, but also worker larvae receive a certain amount of nutritious jelly, although the worker jelly appears to have lower concentration of sugars and some other ingredients compared to the queen food17. However, after 3 days of growth only queen-destined individuals will continue to get unrestricted quantities of a special multifactorial food, produced in head glands of nurse bees, known as royal jelly14,15,18 or bee milk19. In contrast, worker larvae switch to a simpler diet consisting of pollen and sugars, which ensures that they will become functionally sterile helpers. It has been argued that nutritional stress during development to which worker larvae are subjected after 3 days on rich royal jelly-like diet is a critical factor enforcing major reshaping of the worker’s organismal outcome in particular ovarian function and behavioural physiology20. Such nutritional stress associated with differential feeding may have been a driver of evolutionary inventions associated with division of labour and insect sociality20. It is a striking example of regulatory processes utilising nutritional impact on developmental reprogramming of multipotent cells and how a specialised diet interacting with a single genotype, mediated by epigenomic changes can generate two contrasting organisms7,21,22. Currently, this is the most experimentally accessible model in which a defined environmental stimulus, royal jelly, controls post-embryonic development by means of gene regulation via epigenomic modifiers7,21,23,24. This highly successful evolutionary invention has been the topic of numerous studies including micro-array and ultra-deep RNA sequencing often combined with genomics and methylomics (epigenomics) that provided initial impetus to unravelling the intricate genetic network driving mechanistic features of phenotypic plasticity in honey bees25–27.

Caste Determination as an Epigenetic Developmental Process

Developmental processes are regulated by a network of interconnected regulatory circuits with multiple genes expressed in a precise spatio-temporal pattern. It is therefore not surprising that a highly publicised 2011 Nature paper in which one protein was deemed to be the singular driver of developmental canalisation of the honey bee queens28 has met with some reservations23,29. The protein in question, fittingly dubbed Royalactin was suggested to act as the master inducer of queen developmental trajectory via the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), to determine the fate of queen or worker. The sole author of that study Kamakura reinforced this notion by evidence obtained in Drosophila in which Royalactin appears to induce increased body size and accelerated development by activating EGFR and p70 S6 kinase signalling pathway.

Royalactin (a monomeric form of Major Royal Jelly Protein 130–32) is one of many components of royal jelly, a unique larval food whose complex composition remains poorly understood30,33–35. When a selected female larva is exclusively fed royal jelly it becomes a reproductive long-lived queen. Given the complex nature of this diet and the need for copious amounts of royal jelly over a period of 6 days to produce a mature queen, a conventional explanation of this phenomenon is that a finely tuned feeding regime leads to changes in metabolic flux26,27, hormone levels36–38 and activation of a cascade of epigenetic regulatory mechanisms including DNA methylation, histone modifications and non-protein coding RNAs, which have the capacity to alter global gene regulation required for producing contrasting organismal outcomes from one genome7,25–27,39. Because enzymes responsible for adding or removing epigenetic marks are dependent upon, or influenced by, metabolites, metabolic flux is now recognised as an important driver of DNA and histone modifications and thus a prime mover in gene regulation24,25,40 (Fig. 1).

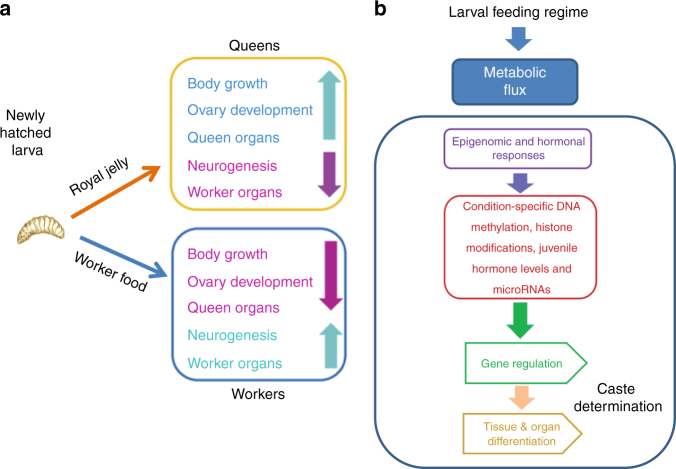

Fig. 1.

Nutritional programming of postembryonic development in honey bees. a Newly hatched female larvae are multipotent and can develop either into short-lived functionally sterile workers or long-lived fertile queens depending on the feeding regime during larval growth. The entire queen development from a fertilised egg to an adult takes 16–17 days. Workers emerge as adults around 5 days later than queens16. The distinctiveness in neuronal development in the worker larvae may be associated with the early stages of building a sophisticated nervous system required for workers remarkable navigational skills and high mnemonic fidelity during adult life. b Larval feeding regimes act as an external cue that directs epigenetic programing of postembryonic development in a caste-specific manner via metabolic flux. Royal jelly activates pathways associated with the catabolism of proteins, carbohydrates and fats, as well as the major energy pathways. This can be observed as increased growth rates seen in queen larvae relative to that seen in larvae destined to become workers. This process is based on threshold adjustments occurring at several levels, including hormone levels and epigenomic modifications, until a point of no return is reached and development is committed to one phenotype

In this context the main findings of Kamakura are quite remarkable because they imply that this epigenetic process is in fact driven by only one ingredient in royal jelly, namely a monomeric form of Royalactin28. While the study is impressive in terms of the amount of experimental data, especially using the surrogate Drosophila system, it also contains a questionable result on egfr methylation29 and, conceptually, represents a return to outdated linear molecular simplicity, a point criticized by many authors22,41–43. In discussing the implications of Royalactin, the author overlooks the vast trove of data on conditional phenotypes1–6,14, the quantitative biological constraints that are manifested during development and the inherent pitfalls in data transferability between different species at particular levels42. The evident omission of such relevant datasets in understanding Royalactin’s activities is one reason for confusion surrounding the Royalactin story. Given a huge interest in phenotypic plasticity and genotype–environment interactions, it was only a matter of time before a follow-up study on the proposed role of Royalactin would be available. In a recent article also published in Nature, Buttstedt et al.23 describe their unsuccessful attempts to repeat some of the original Royalactin experiments and conclude that this protein “is not a royal making of a queen”, effectively suggesting that the 2011 Nature results are invalid. In a rebuttal letter accompanying this story, the author of the 2011 study, Kamakura, forcefully argues that the experimental design in Buttstedt et al.23 ignores a critical aspect of royal jelly as a determinant of queen fate, namely its quantity44. While Kamakura might be right that Buttstedt and colleagues23 used smaller quantities of royal jelly in their in vitro experiments than those used in the 2011 Nature paper17, this explanation does not change the fact that Royalactin cannot induce queen phenotype unless a critical amount of royal jelly is present, suggesting that instead of being a unique control button it acts as one of several important dietary components whose concerted action is required to enforce the queen’s developmental trajectory.

To fully appreciate the complexity of this issue it is important to highlight several highly relevant aspects of larval development in honey bees: First, all newly hatched female larvae are initially fed a multifactorial diet (royal jelly or worker jelly14,15,17), but after 3 days of growth, only the larva destined to become queen will receive copious amounts of royal jelly14,45 (Fig. 2), the quantitative component is critical, as emphasised by Kamakura44 in his response to Buttstedt et al.23 Indeed, larvae grown in the lab on lower concentrations of royal jelly do not develop all queen features and are characterised as intermediates7,23,46. Furthermore, larvae grown on royal jelly deprived of Royalactin also develop queen or queen-like characteristics23.

Fig. 2.

Queen development. A queen pupa undergoing metamorphosis in a special sealed cell that was initially full of royal jelly. The excess of food the queen larva receives is highlighted by some royal jelly left at the bottom. At the pupal stage no food is consumed

Second, until day 4 of growth, the developmental trajectory that will lead to a queen is reversible14,45, suggesting that the initial 3-day exposure of a selected larva to royal jelly is not enough to trigger queen development and that the resulting developmental heterochrony is a gradual threshold-based process driven by instructional vectors from nutritional input rather than by a single on–off switch7,26.

Third, a queen can be experimentally induced by interfering with the methylation machinery in newly hatched larvae47, and possibly by other means that disturb the developmental network driving phenotypic outcomes. Queen fate is associated with elevated levels of mTOR and RNAi inhibition of this important growth signalling gene induces worker characteristics in queen-destined larvae48. Importantly, similarly to the effects of lower quantities of royal jelly, these interventions often generate a gradient of phenotypes referred to as ‘inter-castes’23,37,46–48.

Fourth, royal jelly is exceedingly rich in both methionine and methyl groups and some of its major proteins are unusually rich in this essential amino acid, notionally providing substrates for methylation activities49,50. However, because of the circular nature of the methionine biosynthetic pathway, methionine excess may actually impair DNA/RNA methylation by inhibiting re-methylation of homocysteine51.

Fifth, the fatty acid components of royal jelly are unusual and uncommon structures that are not destroyed at 40 °C, the temperature used by Kamakura to inactivate Royalactin28. Some of them exhibit powerful histone deacetylase inhibitory activities7,52, which act as chromatin openers affecting the expression of hundreds of genes from the very moment every young larva gets a mouthful of royal jelly. The perceived queen-stimulating properties of small molecules in royal jelly have been considered in a number of studies, always in conjunction with sufficient amounts of food. In one study, an ethanol soluble, protease resistant fraction of royal jelly has been proposed to contain a “queen determinant” on the basis of its capacity to facilitate induction of a queen phenotype in lab experiments53.

Sixth, the appropriate control for these experiments to determine the extent to which other proteins and smaller molecules in royal jelly are important for queen development would be to use pure Royalactin in combination with a synthetic diet free of the natural ingredients in royal jelly, admittedly a rather unattainable task.

Seventh, Drosophila is indeed facile in terms of experimental manipulation, but it has major drawbacks that impinge upon data transferability (e.g., the lack of DNA methylation toolkit and reproductive division of labour54). Phenotypic outcomes depend absolutely on the genetic background used in the experiments55–57. As just one clear example reveals, in mushroom body miniature, these important brain structures in the fly degenerate in one genetic background, but are completely normal in another58. Indeed, it has been shown that royal jelly/Royalactin effects in Drosophila are strain-dependent implicating genetic background and cryptic sequence variants as an important factor in phenotypic outcomes driven by the heterologous protein57. It is mandatory therefore that if Drosophila is to be a surrogate, than the Royalactin experiments need to be conducted in different genetic backgrounds. Notably, royal jelly-based diet is not only atypical, but also toxic for Drosophila and even at concentrations much lower than those used for bee larvae has strong detrimental effects on life span, productivity and can negatively affect developmental processes57,59. In addition, low levels of royal jelly show similar enhancement for both males and females59, whereas a female-specific effect would be expected if it was acting through an analgous pathway as in honey bees.

Finally, to perturb development in Drosophila, an organism in which Royalactin does not occur, is akin to perturbing a system with biologically based drugs; one learns about the perturbation, but its biological relevance depends absolutely on the network structure and network flux of the recipient60,61. These are quantitative properties of networks, not all or none phenomena (discussed in more detail later on).

In this context, the paper by Grandison et al.62 on the effects of amino acid imbalance on longevity and reproduction may have far reaching implications for nutritionally controlled development of queen bees, in particular for caloric restriction, specific metabolic requirements and regulation via mechanisms involving methyl groups. For example, in contrast to many organisms in which dietary restriction promotes longevity but impairs fecundity63,64, queen bees are an exception. The rich royal jelly diet of a queen bee makes her one of the most fecund animals on the planet, yet she lives 10–20× longer than her sterile genetically identical workers49,50,65,66. The finding by Grandison et al.62 that in Drosophila, methionine alone is necessary and sufficient to increase fecundity as much as does full feeding, but without reducing lifespan, is striking. As mentioned above, the larval and adult queens’ only food (royal jelly), is very rich in both methionine and methyl groups. In addition to free methionine49, some of its major proteins belonging to the Major Royal Jelly Protein (MRJP) family to which Royalactin also belongs are unusually rich in this essential amino acid; MRJP5 contains 68 Met residues (11.5%)50, while acetylcholine in royal jelly is six-fold higher than that found in the insect brain65. Choline is a hydrolysis product of acetylcholine and is a rich source of methyl groups that could be utilised in regulatory pathways controlling the balance between metabolic and reproductive demands.

Clearly, it would be informative to investigate the effects of high methionine content in royal jelly and relationships between caloric restriction, methylation and acetylcholine with longevity and physiology to better understand how by fine tuning the queen’s diet, honey bees successfully maximised the fecundity of a focal individual in a colony without compromising her life span. Such analyses would undoubtedly advance our efforts to address the unresolved questions regarding the role of Royalactin in phenotypic polymorphism of female honey bees.

Another important aspect to consider in the context of the presumed role of Royalactin in development is the extent to which its in vivo conformation translates to signalling effectiveness in modulating various cellular processes. Royalactin is a monomeric form of MRJP1, an abundant glycoprotein that co-purifies from royal jelly with a small peptide Apisimin, which in turn facilities noncovalent assembly of MRJP1/Apisimin into oligomers31. Recent high-resolution structural data have revealed a rather complex picture of this interaction that also involves glycosylation acting as an aggregation inhibitor32. The authors conclude that the semi-unfolded structure of MRJP1_Apisimin aggregates may be advantageous for ensuring efficient hydrolysis in the queen larval gut, which notably contains different enzymes than a worker larval intestinal tract67.

Intriguingly, the application of the CRISPR technology to produce knock-out mutations in the gene encoding Royalactin yielded viable adult individuals with no obvious phenotypic abnormalities68. While this result does not contradict the role of dietary Royalactin in post-embryonic regulatory functions during queen differentiation, it suggests that endogenous Royalactin is dispensable for development. Since this gene also is expressed in the brain69 it would be interesting to determine if brain function is affected in mutated individuals.

Towards an Experimentally Testable Model of Queen Development

Development is particularly vulnerable to opposing trepidations, with multiple downstream outcomes, and this is why phenotypic plasticity is directly linked to development5. A certain level of noise in development is expectable and may even have consequences for adaptation70. Several authors emphasised the importance of the so-called hierarchical gene regulatory networks (GRNs) and their biological properties, e.g. dynamic stability that is capable of containing excessive stochastic noise70,71. Hence, a credible understanding of how phenotypic plasticity evolves should reflect the characteristics of developmental GRNs. A constructive insight into the opportunities here can be gained by taking into account the concept of basins of attraction, a term invented by mathematicians72, but often used in the context of gene regulatory networks61,73. This idea is best explained by an analogy to a ball bearing moving around the bowl until eventually resting at the lowest point, or point of ‘attraction’. That attractiveness is only effective within a certain space or structure termed the basin or state of attraction for that system, because a ball will move towards a different point if removed from the bowl.

Excessive feeding with royal jelly leads to a major perturbation (noise) of metabolic processes in a larva, which is manifested by an initial slower growth of a queen-destined larva in comparison to worker larvae74. The initial noise is rapidly buffered by GRNs and their dynamic stability. As a result, the global network’s topology is remodelled to fit the current instructional vectors from nutrition, which translates into rapid growth and acceleration of queen development. This type of developmental divide is an excellent example of an epigenetic process, whereby external factors generate multiple functional versions of a genome, or epigenomes without affecting the DNA base sequence. One way of visualising the resulting developmental canalisation is by using Waddington’s imaginative allegory of an epigenetic landscape75. Waddington’s original ‘epiegenetic’ notions were about the study of the causal developmental mechanisms linking the genotype and the phenotype and understandably were very general as he could not explain how the environmentally modified gene function can generate lasting, “canalised” reactions. However, a modern interpretation of his ideas encompassing the concepts of dynamic thinking and dynamic systems76 fits well with the original concept of the epigenetic landscape77–79. As shown in Fig. 3, the choice of the two alternate developmental trajectories can be imagined as a growing honey bee female larva (depicted as a yellow ball) travelling across a landscape of mountains and valleys where the valleys represent ‘attractor states or basins’24,80. In this illusory landscape, a developing organism travels along an irregular terrain of phenotypic attractors following a set of instructional vectors until it reaches its final state that is said to be optimal under a given set of conditions79. As noted by some authors, the epigenetic landscape has some important characteristics that are relevant to epigenotype dynamics: it displays canalisation, demonstrates critical periods when particularly big changes can be induced and shows developmental branching, which lead to clearly distinguished alternative tissues78. Indeed, Waddington’s definition of the epigenotype as the set of organising rules or processes linking genotype and phenotype to which various tissues are subjected during development remains fully applicable to modern epigenetics81,82. Predictably, the capacity to buffer the developmental trajectory of a female larva can be compromised if there is environmental or dietary change. In laboratory experiments in which various diets were used, the so-called inter-castes with a mixture of queen and worker phenotypic features have been found with significant frequency23,46,47. In those cases a new set of instructional vectors shifted the growing larva towards a new attractor state. The striking sensitivity of developmental programming to even small external changes (even in the presence of Royalactin) is yet another argument against a single master regulator. Such developmental de-canalisation/re-canalisation is possible because of a high level of degeneracy in biological systems that provide organisms with the ability to change22,83.

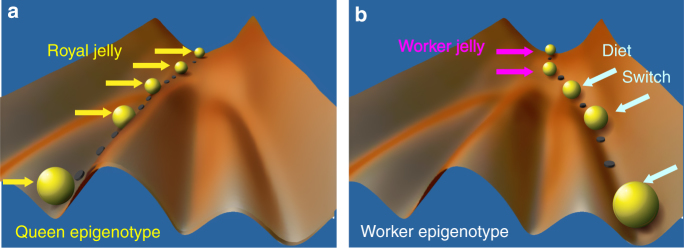

Fig. 3.

A dynamic view of caste determination inspired by Waddington’s epigenetic landscape. A newly hatched female larva, depicted as a yellow ball, moves along a certain trajectory following instructions from the diet she receives from nurse bees. The valleys represent the basins of attractions, which are the most optimal developmental states under the given set of conditions. A larva fed exclusively royal jelly will become a queen (a), whereas a dramatic switch to a less nutritious diet after 4 days will force the larva to take another path resulting in a worker phenotype (b). Although both castes are produced from the same genotype, they have different epigenotypes, described by Waddington as a complex of developmental processes that connect genotype and phenotype, or a set of organising principles to which a certain tissue will be subject during development81,82

Elegant work by the network theory pioneer Barabasi and his colleagues has expanded the protein’s role into “an element in a network of protein–protein interactions, in which it has a contextual or cellular function within functional modules”84. They have provided seminal evidence for this idea by showing that the phenotypic consequence of a single gene deletion is affected to a large extent by the topological position of its protein product in the complex hierarchical web of molecular interactions. Both queen and worker trajectories use the same molecular components to achieve plasticity, e.g., insulin signalling, mTOR, juvenile hormone, vitellogenin, etc., that are epigenetically regulated in a context-dependent manner8–10,26,27,36,85. One challenge in this field is to find matching molecular and cellular criteria that will allow filtering of the irrelevant network nodes (gene products) or those whose effects on network fluxes are phenotypically minimal, away from those that are bona fide drivers of queen development.

The importance of network modularity for developmental plasticity was recognised by West-Eberhard in her modern interpretation of Waddington’s ideas86. By examining the properties of the topology of regulatory networks in queen and worker larvae it should be possible to identify those interconnecting module nodes that are sources of innovation in the evolution of phenotypic dimorphism in honey bees78. Such inter-modules may belong to a less-conserved category of network nodes that provide connectivity between partners in different modules in contrast to highly conserved nodes that have tight connections within individual modules87. One possibility is that the queen specifying mechanisms evolve relatively quickly and operate via interconnecting modules representing more recent evolutionary novelties. The goal of unravelling the underlying mechanisms is attainable by analysing both gene expression and epigenomic changes using frequent sampling of queen, worker and inter-caste larvae from the moment of hatching up to pupation. Particular attention needs to be given to the clusters of committed, yet undifferentiated progenitors of adult structures in female honey bees called imaginal discs88. These pluripotent cells are highly flexible and their fate can be easily manipulated89, suggesting that their responsiveness to instructional vectors is frequently being refreshed. Technological innovation is no longer a limiting step in analysing genomic or epigenomic changes90–93. When properly analysed, such combined datasets of transcriptomes, methylomes, histone modifications, microRNAs and metabolomes would reveal temporal changes in network topologies relevant to each situation. This kind of analysis, albeit on a smaller scale, based on a microarray transcriptional profiling of queen and worker larvae27 has already shown great promise in untangling the differences in caste-specific regulatory networks. Specifically, it has shown that worker’s network is more interconnected than queen’s network suggesting that the worker differentially expressed genes share much more conserved cis-elements when compared to queen differentially expressed genes. This result indicates that workers’ genes are more strongly interrelated.

Conclusion

Crediting a single compound, such as one of the nine highly conserved MRJPs50 to be the sole driver of the honey bee queen development is like crediting resveratrol to be the magic ingredient responsible for the so-called “French Paradox” whereby eating a diet high in “bad” fats can be healthy if it is accompanied by red wine94. The obvious question is why honey bees would risk a collapse of their social structure by opting for a single protein to control one of the most critical aspects of their life cycle, namely the reproductive division of labour. In addition to being the only reproductive individual in the entire colony, the queen has to ensure that workers’ potential to lay unfertilised eggs is inhibited via a complex mechanism involving pheromones and a highly conserved Notch signalling pathway95. In the specific case of its inputs into the mTOR nutrient sensing network48,96, Royalactin is simply one of very many components that contribute to network flux. Obviously, it has a defined and important role in this process, but until the points detailed above have been addressed, it is neither special, nor unique.

More research is badly needed to put the role of Royalactin in a proper context and to create a testable model of caste determination in honey bees. To accelerate progress, what is now required is a convergence of advanced molecular techniques with facets of dynamic thinking, attractor states and the concept of an emergent self-organising system. By taking these notions into consideration we should be able to better understand how a continuously refreshed epigenetic landscape provides instructions for developmental decisions to build different body plans. Applying dynamic thinking to honey bee postembryonic development provides a way forward to experimentally advance a research area that is shrouded in an aura of what most likely is an unnecessary controversy.

Acknowledgements

I thank George Miklos for stimulating discussions that inspired me to develop some of the ideas in this article. The author’s work was supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery grant DP160103053.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans JD, Wheeler DE. Gene expression and the evolution of insect polyphenisms. Bioessays. 2001;23:62–68. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200101)23:1<62::AID-BIES1008>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal AA. Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science. 2001;294:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.West-Eberhard MJ. Phenotypic plasticity and the origins of diversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1989;20:249–278. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.20.110189.001341. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whitman, D. W. & Agrawal, A. A. in Phenotypic Plasticity of Insects: Mechanisms and Consequences (eds Whitman, D. W. & Ananthakrishnan, T. N.) Ch. 1 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2009).

- 6.Simpson SJ, Sword GA, Lo N. Polyphenism in insects. Curr. Biol. 2011;21:R738–R749. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maleszka R. The social honey bee in biomedical research: realities and expectations. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models. 2014;12:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmod.2014.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corona M, Libbrecht R, Wheeler DE. Molecular mechanisms of phenotypic plasticity in social insects. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016;13:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans, J. D. & Wheeler, D. E. Expression profiles during honeybee caste determination. Genome Biol. 2, RESEARCH0001 (2001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Wheeler DE, Buck N, Evans JD. Expression of insulin pathway genes during the period of caste determination in the honey bee, Apis mellifera. Insect Mol. Biol. 2006;15:597–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asencot M, Lensky Y. The effect of sugars and juvenile hormone on the differentiation of the female honeybee larvae (Apis mellifera L.) to queens. Life Sci. 1976;18:693–699. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cameron RC, Duncan EJ, Dearden PK. Biased gene expression in early honeybee larval development. BMC Genom. 2013;14:903. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith CR, Anderson KE, Tillberg CV, Gadau J, Suarez AV. Caste determination in a polymorphic social insect: nutritional, social, and genetic factors. Am. Nat. 2008;172:497–507. doi: 10.1086/590961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weaver N. Physiology of caste determination. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1966;11:79–102. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.11.010166.000455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haydak MH. Honey bee nutrition. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1970;15:143–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.en.15.010170.001043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rembold H, Kremer JP, Ulrich GM. Characterization of post-embryonic developmental stages of the female castes of the honey bee, Apis-Mellifera L. Apidologie. 1980;11:29–38. doi: 10.1051/apido:19800104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, et al. Comparison of the nutrient composition of royal jelly and worker jelly of honey bees (Apis mellifera) Apidologie. 2016;47:48–56. doi: 10.1007/s13592-015-0374-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knecht D, Kaatz HH. Patterns of larval food production by hypopharyngeal glands in adult worker honey bees. Apidologie. 1990;21:457–468. doi: 10.1051/apido:19900507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohashi K, Natori S, Kubo T. Change in the mode of gene expression of the hypopharyngeal gland cells with an age-dependent role change of the worker honeybee Apis mellifera L. Eur. J. Biochem. 1997;249:797–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Kaftanoglu O, Brent CS, Page RE, Jr, Amdam GV. Starvation stress during larval development facilitates an adaptive response in adult worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) J. Exp. Biol. 2016;219:949–959. doi: 10.1242/jeb.130435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maleszka R. Epigenetic integration of environmental and genomic signals in honey bees: the critical interplay of nutritional, brain and reproductive networks. Epigenetics. 2008;3:188–192. doi: 10.4161/epi.3.4.6697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maleszka R, Mason PH, Barron AB. Epigenomics and the concept of degeneracy in biological systems. Brief Funct. Genom. 2014;13:191–202. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elt050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buttstedt A, Ihling CH, Pietzsch M, Moritz RF. Royalactin is not a royal making of a queen. Nature. 2016;537:E10–E12. doi: 10.1038/nature19349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wedd L, Maleszka R. DNA methylation and gene regulation in honeybees: from genome-wide analyses to obligatory epialleles. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016;945:193–211. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-43624-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ashby R, Foret S, Searle I, Maleszka R. MicroRNAs in honey bee caste determination. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:18794. doi: 10.1038/srep18794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Foret S, et al. DNA methylation dynamics, metabolic fluxes, gene splicing, and alternative phenotypes in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:4968–4973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202392109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barchuk AR, et al. Molecular determinants of caste differentiation in the highly eusocial honeybee Apis mellifera. BMC Dev. Biol. 2007;7:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamakura M. Royalactin induces queen differentiation in honeybees. Nature. 2011;473:478–483. doi: 10.1038/nature10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kucharski R, Foret S, Maleszka R. EGFR gene methylation is not involved in Royalactin controlled phenotypic polymorphism in honey bees. Sci. Rep.-UK. 2015;5:14070. doi: 10.1038/srep14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitzova J, et al. A family of major royal jelly proteins of the honeybee Apis mellifera L. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 1998;54:1020–1030. doi: 10.1007/s000180050229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamura S, et al. Molecular characteristics and physiological functions of major royal jelly protein 1 oligomer. Proteomics. 2009;9:5534–5543. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandacaru SC, et al. Characterizing the structure and oligomerization of major royal jelly protein 1 (MRJP1) by mass spectrometry and complementary biophysical tools. Biochemistry. 2017;56:1645–1655. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.7b00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rembold H, Dietz A. Biologically active substances in royal jelly. Vitam. Horm. 1965;23:359–382. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(08)60385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kodai T, Umebayashi K, Nakatani T, Ishiyama K, Noda N. Compositions of royal jelly II. Organic acid glycosides and sterols of the royal jelly of honeybees (Apis mellifera) Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2007;55:1528–1531. doi: 10.1248/cpb.55.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Han B, et al. Novel royal jelly proteins identified by gel-based and gel-free proteomics. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:10346–10355. doi: 10.1021/jf202355n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartfelder K, Engels W. Social insect polymorphism: hormonal regulation of plasticity in development and reproduction in the honeybee. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1998;40:45–77. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)60364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rembold H, Czoppelt C, Rao PJ. Effect of juvenile-hormone treatment on caste differentiation in honeybee, Apis-Mellifera. J. Insect Physiol. 1974;20:1193–1202. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(74)90225-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wirtz P, Beetsma J. Induction of caste differentiation in honeybee (Apis mellifera) by juvenile-hormone. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 1972;15:517–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1570-7458.1972.tb00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dickman MJ, Kucharski R, Maleszka R, Hurd PJ. Extensive histone post-translational modification in honey bees. Insect Biochem. Mol. 2013;43:125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Donohoe D, Bultman SJ. Metaboloepigenetics: interrelationships between energy metabolism and epigenetic control of gene expression. J. Cell. Physiol. 2012;227:3169–3177. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mattick JS, Taft RJ, Faulkner GJ. A global view of genomic information—moving beyond the gene and the master regulator. Trends Genet. 2010;26:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maleszka R, de Couet HG, Miklos GLG. Data transferability from model organisms to human beings: insights from the functional genomics of the flightless region of Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:3731–3736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brenner S, Dove W, Herskowitz I, Thomas R. Genes and development: molecular and logical themes. Genetics. 1990;126:479–486. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamakura M. Kamakura replies. Nature. 2016;537:E13–E13. doi: 10.1038/nature19350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shuel RW, Dixon SE. The early establishment of dimosphism in the female honeybee, Apis mellifera L. Insectes Soc. 1960;VII:265–282. doi: 10.1007/BF02224497. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Souza DA, et al. Morphometric identification of queens, workers and intermediates in in vitro reared honey bees (Apis mellifera) PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123663. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kucharski R, Maleszka J, Foret S, Maleszka R. Nutritional control of reproductive status in honeybees via DNA methylation. Science. 2008;319:1827–1830. doi: 10.1126/science.1153069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patel A, et al. The making of a queen: TOR pathway is a key player in diphenic caste development. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e509. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pratt JJ, Jr., House HL. A qualitative analysis of the amino acids in royal jelly. Science. 1949;110:9–10. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2844.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Drapeau MD, Albert S, Kucharski R, Prusko C, Maleszka R. Evolution of the Yellow/Major Royal Jelly Protein family and the emergence of social behavior in honey bees. Genome Res. 2006;16:1385–1394. doi: 10.1101/gr.5012006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterland RA. Assessing the effects of high methionine intake on DNA methylation. J. Nutr. 2006;136:1706S–1710S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1706S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Spannhoff A, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor activity in royal jelly might facilitate caste switching in bees. Embo Rep. 2011;12:238–243. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rembold H, Lackner B, Geistbeck I. The chemical basis of honeybee, Apis mellifera, caste formation. Partial purification of queen bee determinator from royal jelly. J. Insect Physiol. 1974;20:307–314. doi: 10.1016/0022-1910(74)90063-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lyko F, Maleszka R. Insects as innovative models for functional studies of DNA methylation. Trends Genet. 2011;27:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chandler CH, Chari S, Tack D, Dworkin I. Causes and consequences of genetic background effects illuminated by integrative genomic analysis. Genetics. 2014;196:1321–1336. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.159426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gibson G, Dworkin I. Uncovering cryptic genetic variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;5:681–690. doi: 10.1038/nrg1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morgan SL, et al. The phenotypic effects of royal jelly on wild-type D. melanogaster are strain-specific. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Belle JS, Heisenberg M. Expression of Drosophila mushroom body mutations in alternative genetic backgrounds: a case study of the mushroom body miniature gene (mbm) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:9875–9880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shorter JR, et al. The effects of royal jelly on fitness traits and gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0134612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miklos GL, Maleszka R. Protein functions and biological contexts. Proteomics. 2001;1:169–178. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200102)1:2<169::AID-PROT169>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miklos GL, Maleszka R. Microarray reality checks in the context of a complex disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:615–621. doi: 10.1038/nbt965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grandison RC, Piper MDW, Partridge L. Amino-acid imbalance explains extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in Drosophila. Nature. 2009;462:1061–U1121. doi: 10.1038/nature08619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Holliday R. Food, reproduction and longevity: is the extended lifespan of calorie-restricted animals an evolutionary adaptation? Bioessays. 1989;10:125–127. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mair W, Dillin A. Aging and survival: the genetics of life span extension by dietary restriction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2008;77:727–754. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061206.171059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colhoun EH, Smith MV. Neurohormonal properties of Royal jelly. Nature. 1960;188:854–855. doi: 10.1038/188854a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haddad LS, Kelbert L, Hulbert AJ. Extended longevity of queen honey bees compared to workers is associated with peroxidation-resistant membranes. Exp. Gerontol. 2007;42:601–609. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chan QW, et al. Honey bee protein atlas at organ-level resolution. Genome Res. 2013;23:1951–1960. doi: 10.1101/gr.155994.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kohno H, Suenami S, Takeuchi H, Sasaki T, Kubo T. Production of Knockout Mutants by CRISPR/Cas9 in the European Honeybee, Apis mellifera L. Zool. Sci. 2016;33:505–512. doi: 10.2108/zs160043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kucharski R, Maleszka R, Hayward DC, Ball EE. A royal jelly protein is expressed in a subset of Kenyon cells in the mushroom bodies of the honey bee brain. Naturwissenschaften. 1998;85:343–346. doi: 10.1007/s001140050512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ruvinsky, A. Genetics and Randomness (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2010).

- 71.Erwin DH, Davidson EH. The evolution of hierarchical gene regulatory networks. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009;10:141–148. doi: 10.1038/nrg2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nusse, H. E, Yorke, J. A. & Kostelich, E. J. Dynamics: Numerical Explorations: Accompanying Computer Program Dynamics, 269–314. (Springer, US, 1994).

- 73.Wuensche, A. Genomic Regulation Modeled as a Network with Basins of Attraction Pac. Symp. Biocomput. 89–102 (1998). [PubMed]

- 74.Thrasyvoulou AT, Benton AW. Rates of growth of honeybee larvae. J. Apic. Res. 1982;21:189–192. doi: 10.1080/00218839.1982.11100540. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Waddington, C. H. Organisers and Genes (The University Press, Cambridge, 1940).

- 76.Thelen, E. & Smith, L. A Dynamic Systems Approach to the Development of Cognition and Action (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1994).

- 77.Tronick E, Hunter RG. Waddington, dynamic systems, and epigenetics. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016;10:107. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jablonka E, Lamm E. Commentary: the epigenotype—a dynamic network view of development. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2012;41:16–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.McGrath JJ, Hannan AJ, Gibson G. Decanalization, brain development and risk of schizophrenia. Transl. Psychiatry. 2011;1:e14. doi: 10.1038/tp.2011.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miklos GLG, Maleszka R. Epigenomic communication systems in humans and honey bees: from molecules to behavior. Horm. Behav. 2011;59:399–406. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Waddington, C. H. An Introduction to Modern Genetics (George Allen & Unwin, London, 1939).

- 82.Waddington CH. The epigenotype. Endeavour. 1942;1:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Edelman GM, Gally JA. Degeneracy and complexity in biological systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13763–13768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231499798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jeong H, Mason SP, Barabasi AL, Oltvai ZN. Lethality and centrality in protein networks. Nature. 2001;411:41–42. doi: 10.1038/35075138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mutti NS, et al. IRS and TOR nutrient-signaling pathways act via juvenile hormone to influence honey bee caste fate. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:3977–3984. doi: 10.1242/jeb.061499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.West-Eberhard, M. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution (Oxford University Press, USA, 2003).

- 87.Fraser HB. Modularity and evolutionary constraint on proteins. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:351–352. doi: 10.1038/ng1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Santos CG, Hartfelder K. Insights into the dynamics of hind leg development in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) queen and worker larvae—a morphology/differential gene expression analysis. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2015;38:263–277. doi: 10.1590/S1415-475738320140393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Worley MI, Setiawan L, Hariharan IK. Regeneration and transdetermination in Drosophila imaginal discs. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2012;46:289–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Welsh L, Maleszka R, Foret S. Detecting rare asymmetrically methylated cytosines and decoding methylation patterns in the honeybee genome. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2017;4:170248. doi: 10.1098/rsos.170248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Maleszka R. Epigenetic code and insect behavioural plasticity. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2016;15:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cois.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bock C. Analysing and interpreting DNA methylation data. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012;13:705–719. doi: 10.1038/nrg3273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hunt GJ, Gadau JR. Editorial: advances in genomics and epigenomics of social insects. Front. Genet. 2016;7:199. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2016.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ferrieres J. The French paradox: lessons for other countries. Heart. 2004;90:107–111. doi: 10.1136/heart.90.1.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Duncan EJ, Hyink O, Dearden PK. Notch signalling mediates reproductive constraint in the adult worker honeybee. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12427. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang Y, et al. Down-regulation of honey bee IRS gene biases behavior toward food rich in protein. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]