Abstract

The ubiquitin proteasome system has been validated as a target of cancer therapies evident by the US FDA approval of anticancer 20S proteasome inhibitors. Deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), an essential component of the ubiquitin proteasome system, regulate cellular processes through the removal of ubiquitin from ubiquitinated-tagged proteins. The deubiquitination process has been linked with cancer and other pathologies. As such, the study of proteasomal DUBs and their inhibitors has garnered interest as a novel strategy to improve current cancer therapies, especially for cancers resistant to 20S proteasome inhibitors. This article reviews proteasomal DUB inhibitors in the context of: discovery through rational design approach, discovery from searching natural products and discovery from repurposing old drugs, and offers a future perspective.

Keywords: : 19S, 26S, cancer, deubiquitinating enzymes, drug reposition, DUB inhibitors, molecular targeting, rational design, ubiquitin proteasome system

The ubiquitin proteasome system

Ubiquitination by E1, E2 & E3

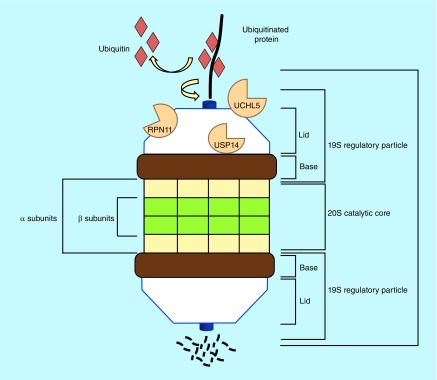

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) consists of a small protein molecule called ubiquitin and a large multiunit complex called the 26S proteasome (Figure 1). Ubiquitin is responsible for tagging a protein substrate to the 26S proteasome for its degradation [1]. Ubiquitin conjugation to the substrates occurs through three classes of enzymes, the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2) and the ubiquitin-ligating enzyme (E3). E1 is responsible for ATP hydrolysis and ubiquitin adenylation. E2 catalyzes the covalent attachment of ubiquitin to the lysine residue of the target protein. E3 confers substrate's specificity [1]. The ubiquitin contains seven internal lysine residues, through which polyubiquitin chain can be linked and tagged to the protein substrates for trafficking and delivery to the proteasome [2].

Figure 1. . Degradation of ubiquitinated proteins by 26S proteasome.

26S proteasome is comprised of a 20S core particle and one or two 19S proteasomal caps. 20S proteasome is labeled, along with 19S proteasome including the three associated DUBs, UCHL5, USP14 and RPN11. A ubiquitinated target protein is first recruited to 19S proteasome, deubiquitinated by the DUBs and then degraded by 20S proteasome, while ubiquitin is recycled.

DUB: Deubiquitinating enzyme.

26S, 20S & 19S proteasomes

The 26S proteasome is composed of approximately 50 subunits acting as a highly specific molecular shredder to hydrolyze the protein substrate into small peptides. The 26S proteasome holoenzyme consists of the 20S central catalytic core (known as the CP or 20S complex) capped by one or two 19S regulatory particles (known as RP, 19S complex or PA700) at either end [1,2]. The 20S CP is a barrel-like structure composed of 28 subunits, arranged as four stacked heptameric rings (7α, 7β, 7β and 7α) around a central cavity [3,4]. The outer two α rings have a regulatory role, while the inner two β rings are responsible for the proteolytic activity of CP. β1 has caspase-like activity, β2 confers the trypsin-like activity and β5 is responsible for chymotrypsin-like activity [5], which gives the proteasome the ability to cleave protein substrates after acidic, basic and hydrophobic residues, respectively [4].

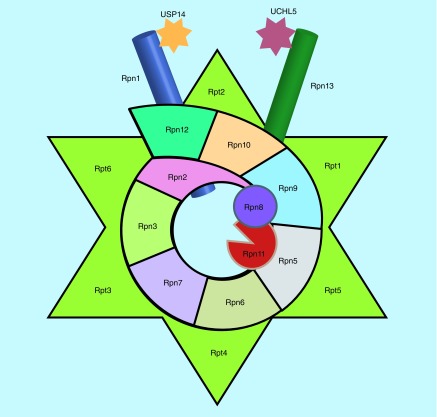

The 19S RP (Figure 2) has at least 19 subunits and composed of lid and base. The base mediates the opening of 20S gate because it interacts directly with the α ring assembly [4]. The proteasome is highly specific for ubiquitinated substrates, and degradation of nonubiquitinated proteins are prevented by 19S RP. Thus, it provides selectivity for the ubiquitinated protein substrates through entry into 20S CP [4]. Ubiquitinated proteins are captured by specific receptors in the 19S RP [6]. Once the ubiquitinated conjugates bind to 19S, they will be deubiquitinated by proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) and will undergo unwinding by the 19S RP ATPases which are located in the base and then fed into the 20S CP for degradation [6].

Figure 2. . Diagram of 19S proteasome.

19S regulatory particle can be divided into the base and the lid. Six RP triple ATPases (Rpt1–6) and three RP non-ATPases (Rpn1, Rpn2 and Rpn13) form the base. Rpn10 links the base to the lid. All the other Rpns form the lid. Rpn11 is a 19S member and a DUB. Other two DUBs, USP14 and UCHL5, are reversibly associated with Rpn1 and Rpn13, respectively. Rpn4 or Rpn14 are transcription factors or assembly chaperones.

DUB: Deubiquitinating enzyme; RP: Regulatory particle.

The mechanisms for regulation of the proteasome are still poorly understood but it has been reported that there are different proteins that are reversibly associated with the proteasome. Some proteins have a role in binding the RP and delivering the ubiquitin conjugates to the proteasome, others open the axial channel into the catalytic core, and a third class of proteins includes the ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases that could modify the proteasome-bound ubiquitin chains [6]. The ubiquitination that promotes protein degradation and includes ubiquitin ligating (E3 ligase) is a reversible process, which could be reversed by deubiquitination via DUBs that cleave the isopeptide bond at the C terminal of ubiquitin [7].

General DUBs

DUBs in eukaryotes are responsible for removal of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like chains from the target protein before its degradation, therefore regulating different cellular processes such as cell cycle control, DNA stabilization, chromatin modification and cellular signaling pathways. DUBs can prevent substrates from degradation, resulting in increased protein accumulation [8].

Approximately 100 DUBs are encoded by the human genome and they are divided into five [7] or six [9] subfamilies. There are five families which belong to cysteine proteases that include motif-interacting with ubiquitin-containing novel DUB family, ubiquitin-specific protease (USP), ubiquitin C-terminal protease hydrolases (UCHs), Machado-Joseph domain-containing proteins and Otubain domain-containing protease. Additionally, there is one family that belongs to the zinc metallopeptidases, JAMMs (JAB1, MOV34, MPN) [10]. This review focuses on proteasome-associated DUBs.

Three 19S-associated DUBs, USP14, UCHL5 & RPN11

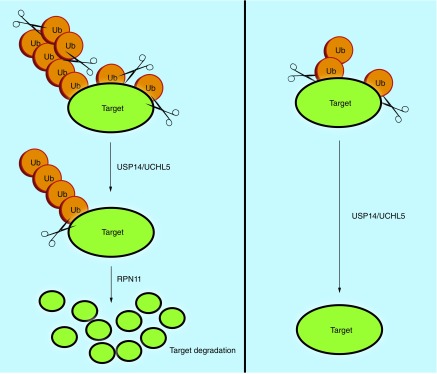

Three DUBs are associated with the 19S RP (Figure 1) in mammalian cells. Two DUBs, USP14/Ubp6 and UCHL5/UCH37, belong to cysteine proteases class and are in the lid, and their activity is toward the distal tip of ubiquitin chain. The third DUB, POH1/RPN11, belongs to metalloprotease and is located at the base, which cleaves the ubiquitin chain from its base [11–14]. These proteasome-associated DUBs play an important role in maintaining the ubiquitin homeostasis via recycling of ubiquitin, facilitating the protein degradation by removal of sterically bulky ubiquitin and rescue of poorly ubiquitinated protein [6]. Figure 3 illustrates how deubiquitination by these DUBs could lead to increased levels of substrate degradation or stability.

Figure 3. . The process of deubiquitination of a target protein by one or more of the three 19S-deubiquitinating enzymes leads to increased degradation or stability of the substrate protein.

There are different ubiquitin receptors associated with the proteasome, and the substrates are relatively susceptible to chain trimming by USP14 and UCHL5, which was suggested to be dependent on which receptors engaged with a given substrate and the positioning of these receptors with respect to USP14 and UCH37 (UCHL5). UCHL5 binds to the ubiquitin receptor RPN13 [15,16], while USP14 binds to the RPN1 subunit in the base of 19S RP [17].

The yeast ortholog of USP14 is Ubp6, while not essential, its loss increases the sensitization of cells to stressors due to a rapid depletion of the free ubiquitin pool [18]. USP14 is considered as a potent inhibitor of proteasome degradation. It causes chain trimming that leads to inhibition of proteasome activity through deubiquitination. This trimming governs the rate of degradation of many ubiquitin conjugates. The ability of these DUBs to inhibit the proteasome-mediated degradation of ubiquitinated proteins results in maintenance of the ubiquitin pools inside the cells [18,19]. For example, UPS14 could remove or trim an ubiquitin chain of a substrate protein, preventing it from degradation by 20S proteasome; in addition, USP14 could slow down the rate of proteasome-mediated substrate degradation. Both of the above mechanisms contribute to the degradation inhibition property of USP14 [19,20]. In addition to its inhibitory effect on the proteasome degradation, USP14 regulates the gate opening of 20S proteasome after its association with the ubiquitin conjugates [14].

UCHL5 may have dual roles in proteasome-mediated degradation; it could inhibit the degradation by disassembly of distal polyubiquitin moieties and could catalyze the selected degradation of specific substrate such as nitrogen oxide synthase and inhibitor of kappa B (IkB) [21,22]. Its deubiquitinating activity depends on its association with the ubiquitin receptors at the base of 19S named Rpn13/ADRM1 [15,23]. A conformation change is induced in UCHL5 through the binding of its C-terminus to ADRM1, leading to activation [15,23]. This activation process is 19S proteasome-binding dependent. It has also been reported that UCHL5 can interact with Ino80 chromatin-remodeling complex, which is important for transcription and DNA repair [24]. When complexed with Ino80 complex, UCHL5 is inactive. However, the role of UCHL5 in the Ino80 complex needs further investigation [25].

RPN11 activity is delayed until the proteasome is committed to degrading the substrate [26]. RPN11 cleaves the entire ubiquitin chain at the base and frees the substrate, which is fed into the 20S CP for hydrolysis. Deubiquitination before the commitment might result in inhibition of the substrates degradation [27]. The activity of USP14 and UCHL5 is not dependent on the commitment as they cleave the chain from its substrate-distal tip [26] and shorten the chain rather than removing them en bloc in a process that appears to antagonize the degradation of proteasome [27].

Proteasomal DUBs & their inhibitors in cancer

Proteasomal DUBs as important regulators in tumor progression

Despite eukaryotes’ need of the proteasome for normal cellular processors, inhibition of its activity may be beneficial. Specifically, 20S proteasome inhibition has been highly effective in treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), in addition to other applications [28]. Tumor tissues showed overexpression of proteasomal DUBs that made them an important target for anticancer therapy, especially RPN11 as it is required for cancer cell viability [29].

RPN11 promotes resistance to several anticancer drugs such as doxorubicin, paclitaxel and 7-hydroxysporine, which may involve modulation of AP-1-mediated stress pathway [29,30]. In addition, RPN11 could modulate the expression of a receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB2, expression of which has been associated with a poor prognosis in breast cancer [30]. RPN11 may counteract the ubiquitination of ErbB2 preventing its degradation. Thus, drugs that target RPN11 control the response of ErbB2-positive breast cancer resistance to conventional treatment. In addition to RPN11, UCHL5 and other DUBs were overexpressed in tumor biopsies of cervical carcinoma when compared with the normal tissue [29]. UCHL5 influences the survival of cells through its ability to alter signaling pathways such as TGF-β signaling. The interruption of the signaling cascade leads to phosphorylation and translocation of SMAD family of transcription factors [31]. UCHL5 could then interact with SMAD7 and counteract the ubiquitination of TGF-β by E3 ligase (Smurf2) that sustains TGF-β [31]. UCHL5 could also alter the expression of apoptotic mediators [31]. Knockdown of UCHL5 in non-small-lung carcinoma has resulted in reduced cell survival, increased caspase activity, downregulation of antiapoptotic factors Bcl-2 oncoprotein and upregulation of apoptotic regulator Bax [31]. USP14 is associated with the progression of cancer and its expression negatively related to patient survival in colorectal carcinoma [32]. Elevated levels of USP14 were also present in lung and liver metastasis. USP14 could also deubiquitinate the chemokine receptor CXCR4, mediating motility of the cancer cells [33].

Proteasomal DUBs as novel targets for cancer therapy

There has been evidence suggesting that targeting the pathways of cancer progression (such as the UPS) may be more effective treatment strategy than targeting solid tumors. The DUBs of the UPS are a promising target for cancer therapy [34]. New strategies can be formulated to target cancer-associated substrates. Inhibition of DUBs leads to the aggregation of ubiquitin-bound substrates as they are not degraded. Thus, substrate degradation can be controlled and utilized to promote anticancer or tumor-suppressant factors, which would otherwise be inhibited [34]. While the UPS is mainly known for its role in MM, many DUBs have been shown to have roles in other cancer types [35]. Proteasomal DUB USP14 has been associated with, but not limited to, ovarian and colorectal cancers [36]. Upregulated USP14 activity and expression levels were found in metastasis developing in the lymph nodes. On the other hand, UCHL5 regulation of TGF-β/Smad signaling and nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) has been demonstrated. UCHL5 overexpression has been linked to lung cancer in A549 cell lines [31]. By targeting these DUBs, antioncogenic substrates may be prevented from degradation.

20S proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs in clinics

Bortezomib or BTZ (PS-341, NSC 681239, Velcade®; Millennium Pharmaceuticals) is a synthetic dipeptide boronic acid that is considered as a reversible inhibitor of the chymotryptic-like activity (β5) with less inhibitory effect on the caspase-like activity (β1) of the 20S proteasome [37]. BTZ was approved by the US FDA for treatment of MM [37]. It was reported that BTZ was effective in treatment of MM resistant to doxorubicin, melphalan and dexamethasone. In addition, BTZ was approved in 2006 for the treatment of patients with mantle cell lymphoma, a lymphoid malignancy derived from mature B cells. The response of patients with mantle cell lymphoma to BTZ was more than 40% and persisted [38,39]. Many of the MM patients showed initial response to BTZ and then relapsed. This may be due to alterations in the stoichiometry of β2- versus β1- and β5-subunits [39–42]. Also, it was noticed that some alterations occurred in the proteasome pathway of BTZ-resistant acute myeloid lymphoma and MM cells. BTZ is unable to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis in the resistant cell [43]. Overexpression of antiapoptotic mitochondrial proteins such as Bcl-2, MCL-1 and Bcl-XL could suppress BTZ-induced apoptosis [44]. However, drugs that can antagonize Bcl-2 family may be able to overcome the BTZ resistance. ABT-737, an inhibitor of Bcl-2 family, showed a synergetic effect with BTZ in mediating cell death in preclinical settings [45].

Synergetic effect was seen when BTZ was used in combination with some clinically used drugs (such as doxorubicin and melphalan) [46], or with inhibition of DNA repair pathways [47]. Furthermore, BTZ and a histone deacetylase inhibitor work synergistically via suppression of aggresome formation. However, clinical use of BTZ is associated with some toxic side effects such as neuropathy [39].

Several next-generation proteasome inhibitors have been approved by the FDA or are being tested in clinical trials, including carfilzomib and ONX-0912. Both of these peptide-epoxyketone proteasome inhibitors can inhibit the proteasomal chymotryptic-like activity irreversibly [48,49]. In addition, carfilzomib is effective in bortezomib-resistant cancer cells in both preclinical and clinical settings [48]. ONX-0912 is currently being tested in several Phases I–II clinical trials; ONX-0912 is suitable for oral administration, while BTZ and carfilzomib are injected intravenously [49]. MLN-9708 (Millennium Pharmaceuticals) and CEP-188770 are reversible peptide boronic acid inhibitors, which are in the early-stage clinical trials [50,51]. Also, marizomib (Nereus), a β-lactone-γ-lactam derivative that inhibits the three proteolytic activities of the 20S proteasome irreversibly or is being tested in clinical settings [52].

Proteasomal DUB inhibition as a potential strategy to overcome 20S proteasome inhibitor resistance

As mentioned above, BTZ is encountered with toxic side effects and drug resistance [39]. Thus, overcoming its resistance has been a great challenge in the field. Since modulation of ubiquitination processes can still be potentially controlled at the 19S rather than the 20S, researchers have been developing 19S-DUB inhibitors for cancer treatment. Like the 20S inhibitors, inhibitors of the 19S could be developed to counteract underexpression of key anticancer proteins [34]. More detailed discussion is provided in below sections. Also, one could target a downstream event to overcome BTZ resistance. It was found that resistance to 20S proteasome inhibition is associated with an increase in the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins. Targeting substrates such as Bcl-2, therefore, could serve as a more potent and viable option to treat 20S inhibitor-resistant diseases [53].

Proteasomal DUB inhibitors: discovery through rational design approach

Inhibitors of USP14 & UCHL5

Ubiquitin vinyl sulfone

The inventors exploited the ubiquitin specificity of the proteins and the cysteine active sites, thus creating a ubiquitin substrate with the vinyl sulfone group [54]. The ubiquitin provides the specificity to the active site, while the vinyl sulfone acts as the electrophile that forms a covalent linkage between the cysteine residue of the active site and the vinyl sulfone [54].

Ubiquitin vinyl sulfone (Ub-VS; Table 1) is considered to be a suicide inhibitor as the interaction between the electrophile and the active site is irreversible [54]. Furthermore, additional labeling of the vinyl sulfone-conjugated ubiquitin allows for directive visualization of the activity of proteins in the ubiquitination cycle [55]. Probes such as [125I]-Ub-VS can be created to determine the inhibitory effect of Ub-VS on DUBs-related processes. Due to the covalent modification nature of Ub-VS, it has become a popular novel inhibitor used in assays in the discovery of other noncovalent UCH- and UBP-specific inhibitors [55]. Other studies used the DUB inhibitor to determine the role DUBs have in certain cancer cell lines. Additionally, the simple addition of tags to Ub-VS provided a simple avenue to track and measure inhibition [55].

Table 1. . Summary of published 19S-deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors synthesized by rational design.

| Compounds | Targets | Mode of action | Models | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ubiquitin Vinyl-sulfone |

UCHs USPs DUBs (excluding JAMM class) |

Covalently irreversible binds to protein subclasses UCH and USP, thus inhibiting hydrolysis of polyubiquitin in vitro leading to ubiquitinated protein accumulation | Any cellular expression of UCHL5 and USP14 | [54,55] |

| IU1/IU1-47 | USP14 | Increases oxidized protein degradation Leads to oxidative stress recovery in vitro. Known substrates include Tae proteins, cODC-EGFP and TDP-43 |

HEK293, HeLa, primary mouse embryonic (MEFs) | [56,57] |

| b-AP15/VLX1570 | UCHL5 USP14 |

Inhibits substrates through α-β carbonyl addition active site modification, which results in decreased tumor progression that has been demonstrated in vitro and in vivo. Substrates include p53, caspase-3, PARP, CDKN1A, CDKN1B | HCT-116, CK18, orthotopic breast carcinomas in BALB/C mice, syngeneic LLC tumors in C57BL/6J, FaDu human tumor xenografts in SCID mice | [58–61] |

| Azepan-4-ones | UCHL5 USP14 |

Inhibition of DUBs through inhibition of UCHL5 and USP14 affecting Bcl-2 expressions. Treatment of cancer that is refractory to treatments such as bortezomib | Multiple myeloma, solid tumors | [62] |

| RA-9 | UCHL5 USP14 |

α-β Carbonyl modification on cysteine residues | Ovarian cancer (lines SKOV-3, TOV-21G, OVCAR-3 and ES-2) in vivo and in vitro | [63,64] |

| OPA | RPN11 Metal-containing enzymes |

Metalloprotein-specific chelator. Chelation of Zn2+ of RPN11 results in inhibition | Multiple myeloma | [65,66] |

| Capzimin/8TQ | RPN11 | Stabilizes substrates p53, HIF-1 α and Nrf2 | Lung cancer, multiple myeloma | [67] |

| WP1130 | UCHL5 USP14 USP9X |

Substrate control of p53 and MCL-1. Leads to tumor cell apoptosis through the specific DUB inhibition in the UPS. Induces cytotoxicity in triple-negative breast cancer lines | Prostate cancer (VCap), breast cancer (MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468) | [68,69] |

| P5091 | USP7 | Induction of HDM2 through polyubiquitination leads to stabilization of p53 | Multiple myeloma, Neuroblastoma xenograft in mice | [71] |

| NEM | Thiol-containing proteins, metalloproteins | Able to form thioether bonds with reduced cysteines (sulfhydryls) | Multiple myeloma | [72,73] |

DUB: Deubiquitinating enzyme; UCH: Ubiquitin C-terminal protease hydrolase; USP: Ubiquitin-specific protease.

IU1

IU1 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) was the first USP14-specific inhibitor demonstrated in vitro and in cells. The drug was discovered from a high-throughput assay [56]. The original discovery study proposed that the drug increases the degradation rate of proteasome substrates through the inhibition of the USP14 DUB. IU1 is a pyrrolyl pyrrolidinyl-ethanone, which is cell permeable [56]. The structure suggests that the drug targets the thiol group in the active site cysteine of proteases. IU1 reportedly was unable to inhibit other significant DUBs. The Ub-VS labeling experiment with USP14 upon incubation of IU1 shows that no mass-shift associated with USP14, suggesting that IU1 binds competitively to the active site [56]. However, the data showed the mass shift of the UCHL5 protein when treated with Ub-VS after incubation of IU1. This suggested that IU1 does not bind or affect the active site of UCHL5, confirming the specificity to USP14. USP14 reportedly is a regulator of prostate cancer proliferation through deubiquitination and stabilization of the androgen receptor [56]. Studies suggest that IU1 inhibition of USP14 decreases proliferation of prostate cancer LNCaP cells. Small-interfering RNA or short hairpin RNA were used to knockdown USP14 and to validate it as a target of IU1 [56].

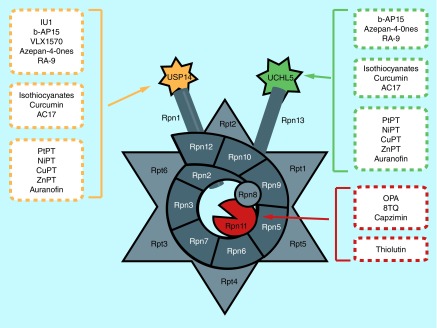

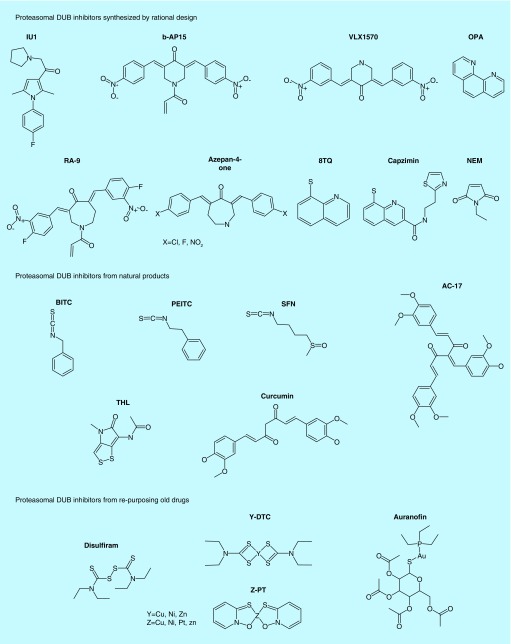

Figure 4. . Summary diagram of 19S-deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors.

Figure 5. . Chemical structures of 19S-deubiquitinating enzyme proteasomal deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors from rational design, nature and drug reposition.

An analog of IU1, namely IU1-47, was synthesized and further evaluated [57]. It was reported that IU1-47 was tenfold more potent than the parental IU1. The effects of the IU1-47 were studied in cultured neurons to confirm the inhibitory properties [57]. It is reported that IU1-47 caused degradation of wild-type tau in neurons at significantly higher rate than IU1. The study proposes that IU1-47 further targets lysine 174 in tau protein, which may contribute to the higher specificity and efficacy [57].

b-AP15

b-AP15 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) was discovered as an inhibitor to both UCHL5 and USP14 in the 19S proteasome cap. The α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group is thought be directly involved in the Michael addition with the thiol in the active site cysteine [58]. b-AP15 was identified from a pool of compounds that were screened to evaluate the compounds for the lysosomal apoptosis pathway. The researchers compared gene expression signatures of b-AP15-treated cells to the Connectivity Map database, which suggested that b-AP15 shared similarities with other potent proteasome inhibitors in the gene expression profiles. Additionally, the data showed that b-AP15 induced a dose-dependent aggregation of conjugated ubiquitin, suggesting inhibition of the degradation activity of the DUBs [58]. Ub-VS labeling assay was then performed using purified 19S DUB upon treatment of b-AP15. b-AP15 blocked Ub-VS labeling to the active sites of USP14. However, b-AP15 also inhibited Ub-UV labeling of UCHL5. This suggested that b-AP15 targets both USP14 and UCHL5. In addition, it was found that b-AP15 has an IC50 value of 2.1 μM when using purified 19S proteasome [56].

This 19S-DUB inhibitor has been linked to multiple applications due to its anticancer properties and the potential to treat BTZ-resistant cancer lines [59]. It has been shown that treatment of BTZ-resistant MM cell lines with b-AP15 decreased cell viability in vitro. b-AP15 caused caspase activations responsible for the increased induction of apoptosis. This inhibitor has also been tied to an increase in caspase-dependent apoptosis and unfolded protein responses. In vivo studies revealed that tumor growth was blocked by b-AP15 in human xenografts [59]. In addition to the findings above, b-AP15 showed increased efficacy in MM in combination with suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, lenalidomide or dexamethasone treatments [59].

VLX1570

VLX1570 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) was developed as an analog of b-AP15 in order to increase the in vivo selectivity and efficacy [60]. Structurally, the α,β-unsaturated carbonyls or the Michael acceptor was not modified from b-AP15. However, the structure of VLX1570 differs in that two 4-nitrobenzylidne groups in b-AP15 were replaced by two 4-fluoro-3-nitrobenzylidene groups in VLX1570, thus increasing the electron-withdrawing property on the side aryls. Additionally, the six-membered piperidine-4-one ring in b-AP15 was substituted to the seven-membered azepane ring in VLX1570 [60]. Protein extracts, harvested from cells treated with VLX1570, were treated with Ub-VS to determine if Ub-VS would outcompete VLX1570 [60]. The results of this assay suggested an increase in USP14 inhibition by VLX1570 compared with b-AP15 [60]. Adversely, Ub-VS outcompeted VLX1570 more significantly in inhibiting UCHL5. Thus, the competitive binding assay using Ub-VS showed that the analog displayed a greater specificity to USP14 rather than UCHL5 compared with b-AP15 [60].

In vivo studies on MM cells revealed that VLX1570 was more effective than b-AP15 in inhibiting tumor progression in mice [61]. Furthermore, tumor progression was inhibited by VLX1570 in BTZ-resistant cancers in mice. siRNA transient knockdown for USP14 or UCHL5 in cell lines resulted in the reduced viability of MM cells [61]. With the promising outcome of VLX1570 in xenograft models, VLX1570 was pushed to enter clinical trials in humans. VLX1570 is a novel drug currently in Phase II clinical trials in the USA to determine the efficacy in MM in human patients [61].

Azepan-4-ones

Azepan-4-ones (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) are a class of compounds, patented by Linder and Larsson that have a mechanism of action which is thought to be very similar to b-AP15 [62]. The compound class is specific to inhibition of UCHL5 and USP14 with no effect in nonproteasomal DUBs. Thus, Azepan-4-ones seem to be thiol-active site directed with specificity for the two 19S DUBs, which contain cysteine-active sites [62]. The similarity to b-AP15 suggests that there is a Michael addition utilizing the α,β-unsaturated carbonyls of the compound to the catalytic active site, thus inhibiting the activity of the DUBs.

Because of the inhibition of Bcl-2, the inventors suggest that Azepan-4-ones would be an effective treatment for BTZ-resistant cell lines. Additional applications of the compounds could include treatments of cancers such as MM and solid tumor malignancies [53].

RA-9

RA-9 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) is another compound with a structure very similar to b-AP15. RA-9, a chalcone-based derivative with α,β-unsaturated carbonyls that are thought to react with the sulfurs in the active site cysteine [63]. RA-9 was shown to have inhibitory properties for proteasome-associated DUBs. There was a dose-dependent relationship found in an Ub-AMC assay of 19S DUBs treated with RA-9, which supports the proposed specificity by the authors [64]. Additionally, treatment of the drug led to a dose-dependent aggregation of polyubiquitinated proteins on a cellular level. This suggests that RA-9 inhibits the DUB-mediated deubiquitination [64]. The application of this compound has been studied in ovarian cancer cell lines. It is proposed that RA-9 inhibits DUB activity in ovarian cancer cells, as studies have shown that RA-9 can inhibit growth, induce caspase-mediated apoptosis, decrease proliferation, and prolongs mouse survival with ovarian cancer [64].

Inhibitors of RPN11

Ortho-phenanthroline

1,10-Phenanthroline also known as OPA (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) is a zinc ion chelator [65]. It has been reported that OPA inhibits the activity of purified RPN11 [66]. OPA is considered an ortho-phenanthroline. Two nitrogen molecules chelate the zinc ion in the active site of the metalloenzyme. OPA is thought to be specific to RPN11 [66]. However, as it is a metal chelator, it chelates any metals to which it is exposed [65]. While USPs and UCHs mostly do not contain an incorporated metal, RPN11 does have zinc-bound active site. Furthermore, it was shown that OPA does not affect proteasome activity when added to RPN11-mutated proteasome extract relative to unmodified extract, which further supports RPN11 specificity [66]. Research on the efficacy of OPA as a potential cancer treatment has been started in MM. Studies indicate that OPA's metallopeptidase inhibition activity is linked to apoptosis in myeloma cell lines including cell lines, which were BTZ resistant [29].

8-Thioquinoline

8-Thioquinoline (8TQ; Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) is a small molecule that was recently reported to have strong RPN11-specific inhibition [67]. A fragment-based drug discovery approach was instrumental into the identification of the RPN11 inhibitor. Studies describe that slight modifications to 8TQ may result in an increase in inhibition activity [67]. Specifically, the increase of RPN11 inhibition was quantified from a transition of IC50 values from 2.5 μM (8TQ) to as low as 400 nM (8TQ derivative) [67]. 8TQ and its analogs are proposed to chelate the zinc ion bound to the active site of RPN11. One analog, S-(Quinolin-8-yl) 2-bromobenzothioate (H18) was shown to have greater specificity toward RPN11 as it inhibited degradation of the reporter protein UbG776V-GFP [67]. Due to the 19S's role in the proliferation of cancerous cells in vitro, 8TQ has been proposed a possible novel treatment to MM and other cancers. The 8TQ and associated compounds were shown to be potent apoptosis inducers in MM cells [67].

Capzimin

After the development of analogs of 8TQ, a derivative named as ‘capzimin’ (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) was selected for further investigation [67]. Capzimin was shown to have a greater than fivefold selectivity for the metalloprotein RPN11. Capzimin, S-(Quinolin-8-yl)-2-bromobenzothioate, was characterized as a thioester derivate [67]. In vitro cleavage assays suggest that the addition of the 1-(O-Bromophenyl)-1-ethanone group to 8-thioquioline results in greater inhibition of RPN11. Additionally, capzimin is reported to induce cancer cell death and resensitize BTZ-resistant MM cells [67].

Other DUB inhibitors

WP1130

WP1130 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) is described as a small molecule responsible for inducing ubiquitination of Bcr-Abl, which leads to aggresome formation as the Bcr-Abl is transported into condensed, intracellular protein complexes [68]. By affecting ubiquitination, WP1130 inhibited the oncogenic activity of Bcr-Abl [68,69]. It was found that WP1130 can directly inhibit USP9X in addition to UCHL5, and USP14. As USP9X inhibition has been linked to apoptosis and prevention of drug resistance in malignancies through Mcl-1 degradation, WP1130 is thought to target a Bcr-Abl-/Mcl-1-specific pathway as a USP inhibitor, suggesting a potential for cancer treatment [68,69].

Development of EOAI3402143 was based on WP1130 very closely. It is proposed that WP1130 was responsible for an upregulation of Usp24 while inhibiting USP9X [70]. Thus, EOAI3402143 was developed to dose-dependently inhibit USP9X and Usp24 activity to increase cancer cell apoptosis. Preliminary data suggested that EOAI3402143 may have a potential for the treatment of both MM and solid tumors [70].

P5091

P5091 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) is a small-molecule inhibitor designed to specifically inhibit USP7 [71]. This inhibitor was discovered through a high-throughput screening for inhibitors of USP7. MTT assays, cell morphology studies and immunoblotting all suggest that P5091 suppresses ovarian cancers by inhibition of USP7 [71]. Additionally, combination treatment of P5091 and BTZ were effective in BTZ-resistant MM, suggesting that P5091 overcomes BTZ resistance [71].

N-Ethylmaleimide

N-Ethylmaleimide (NEM; Figures 4, 5 & Table 1) forms a covalent bond with the free cysteine residues in the medium it is applied to [72]. Thus, the irreversible inhibition of the active sites of multiple thiol-containing DUBs leads to significant DUBs inhibition. Currently, there is the issue of nonspecificity in total cell extracts. As NEM binds to any free cysteines, many other non-DUBs proteins are modified as well [72,73]. Thus, NEM is particularly useful in in vitro studies of purified proteasomal system. Studies have shown that in the presence of NEM, purified proteasomal activity decreases and the amount of total polyubiquitinated proteins increase [73].

Proteasomal DUB inhibitors: discovery from searching natural products

Chemopreventive isothiocyanates

Many natural compounds, such as those present in fruits and vegetables, possess cancer-preventive properties [74,75]. Dietary intake of cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, kale, watercress, etc., has shown significant decrease in the risk of malignancies [76,77]. The chemoprotective properties of these vegetables are attributed to their contents of the natural products that include isothiocyanates (ITCs; Figures 4, 5 & Table 2), such as phenethyl isothiocyanate (PEITC), benzyl isothiocyanate (BITC) and sulforaphane [76–79]. The exact molecular mechanisms responsible for ITCs’ anticancer activity is still unclear [79]. It was reported that these compounds could induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor cell proliferation both in vitro and in vivo [80–82]. PEITC has entered clinical trials for treating lung and oral cancers [83] due to its potent anticancer effect and low inherent toxicity [81,82,84–87]. Additionally, ITCs interrupt many cellular processes that include DNA repair [88], autophagy [77], inflammatory response [79] and antioxidant response [77,79]. ITCs also showed inhibition of activity of many oncogenic proteins. It was reported that BITC and PEITC caused reduction in the expression of antiapoptotic protein MCL-1 in leukemia cells, and inhibition of the oncogenic fusion protein Bcr-Ab1 kinase [89–91].

Table 2. . Summary of natural product-derived proteasomal deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors in the literature.

| Agent | Targets | Inhibition | Anticancer properties | Dietary source | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isothiocyanates – BITCs – PEITC – DL-SFN |

UCHL5 USP14 USP9X |

Electrophiles form reversible adducts with thiols. Forms irreversible adducts with amine. May inhibit DUBs through interaction of active site cysteine | – Induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor cell proliferation in vitro and in vivo – Inhibits oncogenic proteins such as MCL-1 in leukemia cells |

Cruciferous vegetables such as cabbage, broccoli, kale, etc. | [77–79,82,89,91] |

| THL | RPN11 | Induces metal chelation of Zn2+ through inhibition of JAMM domain | – Reversibly inhibits RPN11 with potential DUB-inhibition-related anticancer activity | Streptomyces | [96] |

| Curcumin/AC17 | UCHL1 UCHL3 USP2 USP5 USP8 | Nucleophilic attack from sulfhydryl of cysteine residues on α-β unsaturated carbonyl group of curcumin causes inhibition via active site modification. Inhibition of DUBs results in an accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins. Downregulation of cell cycle promoters as cyclin D-1, upregulation of tumor-suppressor proteins as P53, P27kip1 and p16InkA and induction of cell cycle arrest in S-G2 phase | – Curcumin has antiproliferative and antimetastatic properties in prostate cancer due to downregulation of androgen receptor and EGFR – Downregulates Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL – Induces cleavage of PARP |

Rhizome of Curcuma longa plant | [62,99,100,105,107] |

BITC: Benzyl isothiocyanate; DUB: Deubiquitinating enzyme; PEITC: Phenethyl isothiocyanate; SFN: Sulforaphane; THL: Thiolutin; UCH: Ubiquitin C-terminal protease hydrolase; USP: Ubiquitin-specific protease.

ITCs are electrophiles that form reversible adducts with thiols and irreversible adducts with amines. PEITC and BITC have been shown to inhibit the DUBs at physiologically relevant concentrations [92] through adduct formation with the active site cysteine. The resulting carbon–sulfur double bond of this dithiocarbamate adduct is longer than the corresponding carbonyl bond of the thioester intermediate capturing the stabilizing interactions of the transition state of the DUB reaction [93]. Specifically, PEITC and BITC showed an inhibitory effect toward 19S DUBs USP14 and UCHL5 in addition to other DUBs such as USP9X [93,94]. USP14, UCHL5 and USP9X are overexpressed in different malignancies, and a correlation is present between high levels of these DUBs and poor prognosis. Therefore, inhibition of these DUBs by ITCs might contribute to their cancer-preventive activities, and ITCs might serve as natural lead compounds for designing potent anticancer DUB inhibitors with low toxicity. More than 120 ITCs are available from both dietary and other natural sources forming a large collective for potential lead compounds, drug discovery and functional food design [92]. ITCs showed reduction in the antiapoptotic protein Mcl-1 in several cell lines and the same reduction was observed after inhibition or silence of USP9X. As USP9X was reported to protect the Mcl-1 from degradation and ubiquitination, it was suggested that USP9X is a primary target of PEITC and BITC [69,89,92].

Thiolutin

Thiolutin (THL; Figures 4, 5 & Table 2) is a disulfide-containing antibiotic and antiangiogenic produced by Streptomyces [95]. It reversibly inhibits the growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae and has a potent inhibitory effect on the growth of yeast and on the mRNA degradation through different pathways [95]. In addition, it inhibits RNA synthesis by affecting the DNA-dependent RNA polymerase [96]. It was reported that THL causes inhibition of RPN11 through chelation of its Zn2+ ions. THL inhibits Csn5, which is classified as a paralog to the JAMM DUB RPN11 and is deneddylase of COP9 signalosome [97]. JAMM protease family AMSH could also be inhibited by THL. AMSH has a role in the regulation of ubiquitin-dependent sorting of cell-surface receptors and can cleave K63-linked ubiquitin chain of endosomal proteins [98]. The IC50 of THL for AMSH inhibition was reported to be eightfold higher than that which was measured for RPN11 and could be reversed by Zn2+ cyclen. THL causes inhibition of substrates’ deubiquitination via affecting Brcc36-containing isopeptidase complex [97]. It should be noted that THL also chelates other metals.

Curcumin & analogs

Curcumin (diferuloylmethane; Figures 4, 5 & Table 2) is a polyphenolic natural compound that was extracted from the rhizome of Curcuma longa plant and showed chemopreventive properties. In addition to its anti-inflammatory activity, it is a yellow spice that was used in Ayurvedic, Chinese and Hindu medicine system as a potent anti-inflammatory agent [99–102]. Additionally, it also showed antioxidant [103,104], antimicrobial activities [99], antiproliferative and antiangiogenic [105] properties against different types of cancer cells. It was reported that curcumin could affect many cellular signaling pathways including MAPKs, casein kinase II and COP signalosome in many cancer cell types including prostate cancer [101]. In prostate cancer, curcumin showed antiproliferative and antimetastatic properties via downregulation of androgen receptor and EGF receptor in addition to its ability to induce cell cycle arrest [106]. Curcumin showed inhibition of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo in addition to its ability to induce apoptosis in both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cell lines [107]. It has also been reported that curcumin caused decreased expression of antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, resulting in induction of apoptosis [108]. Curcumin is considered as relatively unstable compound that could be degraded easily, by major degradation into mainly bicyclopentadione, and by minor degradation into ferulic acid, feruloyl methane and vanillin [109]. Ferulic acid and vanillin have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities but their anticancer activity is less than that of the parent compound curcumin [110]. Two series of curcumin analogs totaling 24 compounds were reported. Twenty-three of these compounds showed antiproliferative activities in both prostate cancer and breast cancer cells 50-times higher than curcumin [111]. The anticancer activity of bioflavonoids curcumin and chalcones resulted from their ability to inhibit the DUBs of 26S proteasome without affecting the 20S catalytic core. The α,β-unsaturated carbonyl group of these compounds are susceptible to the nucleophilic attack from the sulfhydryl of cysteines in the active sites of proteasomal DUBs. Other DUBs that were inhibited by charlone derivatives are: UCH-L1, UCH-L3, USP2, USP5 and USP8 [63]. Inhibition of those DUBs resulted in accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, downregulation of cell cycle promoters and upregulation of tumor suppressor [112]. Also, curcumin inhibits the ubiquitin isopeptidases (ubiquitin-specific protases), which are family of cysteine proteases. The inhibitory activity of curcumin toward DUBs was nearly 30% due to its low bioavailability [112].

AC17 is an analog of 4-arylidene curcumin that was developed as an irreversible proteasomal DUB inhibitor [113]. AC17 (Figures 4, 5 & Table 2) rapidly induces an accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins. Compared with curcumin that also inhibits proteolytic activity, AC17 irreversible inhibits the 19S-DUBs that results the inhibition of the NF-κB pathway. Furthermore, the inhibition of NF-κB causes reactivation of p53 [113]. AC17 can also suppress tumor growth in human lung cancer A549 [113]. Thus, the analog AC17 has great potential for anticancer drug discovery.

Proteasomal DUB inhibitors: discovery from repurposing old drugs

Finding new drugs for cancer therapy is imperative considering the high incidence of tumors, but one cannot ignore the obstacles in drug development such as high expense and poor safety. Therefore, repurposing of old drugs which have been used clinically becomes an alternative approach. We and others have screened different kinds of old drugs and reported some of them having the proteasomal DUB-inhibitory activity (Figures 4, 5 & Table 3).

Table 3. . Proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzyme inhibitors containing metal ions.

| Agent | Targets | Cell and animal models | Antitumor mechanisms | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuET | NPL4 | MDA-MB-231, U2OS cells, etc.; nude mice bearing MDA-MB-231 xenografts |

Inhibits p97-dependent protein degradation; induces a heat-shock response; induces cell death |

[123] |

| Cu(II)-DTC, Zn(II)-DTC | 19S JAMM domain | MDA-MB-231 cells | Induces cytotoxic effect | [127,128] |

| ZnPT | UCHL5 USP14 |

U266, K562, A549/DDP, A549, HepG2, SMMC-7721, GFPu-HEK293, primary AML cells, nude mice bearing A549 xenografts | Induces apoptosis, upregulation of p21, p27, independent of DNA damage | [131] |

| NiPT | UCHL5 USP14 |

U266, K562, A549/DDP, A549, SMMC-7721, KBM5, KBM5-T315I, BaF3-p210-WT, BaF3-p210-T315I, LO2, 16HBE, GFPu-HEK293, primary AML/CML cells, nude mice bearing A549/K562/KBM5/KBM5-T315I xenografts |

Induces apoptosis, upregulation of p21, p27, downregulation of Bcr-Abl, independent of DNA damage | [134,135] |

| PtPT | UCHL5 USP14 |

U266, K562, A549/DDP, A549, SMMC-7721, LO2, 16HBE, FPu-HEK293, primary AML cells, nude mice bearing A549/K562 xenografts | Induces apoptosis, upregulation of p21, p27, independent of DNA damage | [132] |

| CuPT | UCHL5 USP14 20S(β5) |

MCF-7, HepG2, U266, NCI-H929, GFPu-HEK293, primary AML cells, nude mice bearing HepG2/NCI-H929 xenografts | Induces apoptosis, upregulation of p21, p27, Bax, IκB-α | [133] |

| AUIII | UCHL1 UCHL3 UCHL5 |

MCF-7, MDA-MB-231, HeLa, nontumorigenic immortalized liver cells | Induces apoptosis, cell-cycle arrest, antiangiogenic property | [137] |

| Auranofin | UCHL5 USP14 |

MCF-7, HepG2, SMMC-7721, KBM5, KBM5-T315I, GFPu-HEK293, primary AML/CML cells, nude mice bearing MCF-7/SMMC-7721/HepG2/KBM5/KBM5-T315I xenografts | Induces ER stress, apoptosis and NF-κB inactivation, upregulation of c-Jun, p21, IκB-α, downregulation of Bcr-Abl, independent of ROS production | [142,143] |

AML: Acute Myeloid Lymphoma; CML: Chronic myeloid leukemia; DTC: Diethyldithiocarbamate; ER: Endoplasmic reticulum; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κB; ROS: Reactive oxygen species; UCH: Ubiquitin C-terminal protease hydrolase; USP: Ubiquitin-specific protease.

Disulfiram or DSF

Disulfiram (DSF; Figure 5 & Table 3) has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of alcoholism with recognized safety and good tolerance in patients since 1951 [114]. It was reported that DSF could increase the aggregation of acetaldehyde through the inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase. The concentration of acetaldehyde induces physical discomfort from the DSF–ethanol reactions that stop people from drinking alcohol [114]. In recent years, the antitumor effect of DSF have been found and investigated.

As early as 1992, Dufour et al. have initiated a clinical test which proved that ditiocarb (diethyldithiocarbamate, DTC), one of metabolites from DSF, has antitumor ability in high-risk breast cancer [115]. Coincidentally, several reports have clarified that DSF induces apoptosis in a number of cell lines including human melanoma, colorectal cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, breast and prostate cancers [116–119]. Notably, DSF was even suggested to inhibit the growth of some cancer-stem-like cells [120]. To date, the mechanisms identified include: inhibition of the proteasome activity, reactive oxygen species–MAPK pathway, NF-kB pathway and hemimethylated DNA substrate [117–119,121,122]. We have also reported that a DSF–copper (Cu) complex could inhibit 20S proteasomal activity and induce apoptosis in human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 and MCF10 DCIS.com cells [117]. However, the specific mechanism of DSF's effect in cancer cells is still not well characterized, furthering the motivation to study the compound.

Ni(II), Cu(II) & Zn(II) DTC complexes

Recently, a nationwide epidemiological study based on the Danish nationwide demographic and health registries was performed, which showed that using DSF may decrease the tumor mortality of patients suffering from common cancers [123]. It was observed that tumor growth of MDA-MB-231-xenografted mice was inhibited after DSF- and DSF/CuGlu-treatment. Meanwhile, the active metabolite of DSF to anticancer in vivo is validated to be a complex of ditiocarb–Cu, CuET (bis(DTC)–Cu). Interestingly, CuET was observed to have strikingly preferential accumulation in tumors. Even though high levels of Cu were found in different types of human cancers including breast, prostate and colon cancers, the detail mechanism still needs more research [124,125]. Moreover, the results showed that DSF binds and immobilizes NPL4 (an adaptor of p97 segregase) via an intact putative zinc finger domain, restraining the regular degradation of ubiquitylated proteins and inducing a heat-shock response [123]. In conclusion, these results suggested that DSF targets cancer by inhibiting the processing of ubiquitylated proteins, which correlated with the NPL4-dependent p97 segregase.

Brar et al. have reported that DSF, binding with zinc and Cu, could inhibit melanoma tumor growth [126], but the mechanism is not clear. Therefore, we combined Cu(II), Zn(II) and Ni(II) (Figures 4, 5 & Table 3), respectively, with dithiocarbamate to form three different complexes, and compared their effects against the 20S proteasome [127]. The results showed that except for Ni(II) complex, both Zn(EtDTC)2 (the putative active compound in DSF/zinc gluconate) and Cu(EtDTC)2 could induce cytotoxic effect as well as inhibit 26S proteasome function in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. However, their effects against purified 20S proteasome were not that strong. Connected with the research before [128], we attributed the inhibition of proteasome to the JAMM domain in the 19S regulatory subunit of proteasome. Interestingly, the analysis of electronic density on atoms and bonds within Ni(EtDTC)2, Cu(EtDTC)2 and Zn(EtDTC)2 showed that Cu(EtDTC)2 should be more active against the JAMM domain of the 26S proteasome than Zn(EtDTC)2, and nickel complex almost would have no effect [127]. These results demonstrated that Cu(II)-DTC and Zn(II)-DTC complexes may interact with JAMM domain of 19S DUBs to inhibit its function.

Pyrithione-based metal complexes (Cu, Zn, Ni, Pt)

Pyrithione (PT; Figures 4, 5 & Table 3) possesses excellent metal-chelating properties. The zinc complex of PT has been used as an antimicrobial compound in antidandruff shampoos and in antifouling paint [129], and has also been reported as a potential antitumor therapy [130]. In the past studies, using PT and several kinds of metals (Zn, Ni, platinum [Pt] and Cu), we prepared different complexes and compared their effects toward the proteasome. We found that all these PT-metal complexes could induce cytotoxicity and UPS inhibition in cancer cells and primary leukemia cells [131–135]. Distinctively, NiPT induced UPS inhibition and apoptosis in both imatinib (IM)-resistant and IM-sensitive CML cells [134,135]. Moreover, these complexes including ZnPT, NiPT, PtPT and CuPT could inhibit proteasome function and tumor growth in nude mice. Regarding the mechanism of action, the results suggested that ZnPT, NiPT and PtPT target the 19S-associated DUBs USP14 and UCHL5. By contrast, CuPT could inhibit both 19S DUBs and 20S proteolytic peptidases [131–135]. Except for PtPT, other complexes also inhibit some other nonproteasomal DUBs in the cytoplasm. Remarkably different from cisplatin [132], PtPT did not show any DNA damage (Figures 4, 5 & Table 3).

Au-based complexes (AUIII, auranofin)

In addition, gold (Au)-based complexes including Au(I) and Au(III) complexes (Figures 4, 5 & Table 3) have also been reported to inhibit cancer growth, and one possible mechanism was defined as DUB activity inhibition [136,137]. Au(III) dithiocarbamate complexes have been clarified to inhibit the 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome activity, leading to ubiquitinated protein accumulation and cell apoptosis in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and transplanted tumor in nude mice [138]. Moreover, it was first reported that auranofin (AF), an Au(I) compound which has been used to treat rheumatic arthritis, was able to inhibit 19S proteasome-associated DUBs USP14 and UCHL5, rather than 20S proteasome [139]. Importantly, the suppression of proteasome-associated DUBs is necessary for AF-triggered cell apoptosis. Furthermore, IM is a classical inhibitor of Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinase, which has significance in the oncogenesis of CML [140,141]. We have demonstrated that AF gave rise to cytotoxicity in both Bcr-Abl wild-type cells and IM-resistant Bcr-Abl-T315I mutation cells in vitro and in vivo [142,143]. Importantly, expression of both Bcr-Abl protein and mRNA was downregulated by AF. Notably, AF-triggered cytotoxicity and UPS inhibition could not be saved by the antioxidant tert-Butylhydroquinone (TBHQ), which proved that proteasomal DUB inhibition, but not reactive oxygen species generation, plays a role in the anticancer effect of AF. In conclusion, these findings revealed AF as a novel strategy for cancer therapy.

Conclusion

A significant amount of progress has been made in the discovery and development of proteasomal DUB inhibitors. The UPS has been targeted due to its correlation with many cancerous pathways. At first, the 20S proteasome was successfully targeted for treatment of multiple myeloma through its inhibition by a specific inhibitor such as bortezomib. However, resistance to 20S proteasomal inhibitors emerged and an alternative target was needed. The proteasomal DUBs were identified as a potential target that could not only overcome the resistance to 20S proteasome inhibitors but also serve as a potential therapeutic for other cancers. Thus began the development of specific proteasomal DUB inhibitors. This review discussed three methods of discovery of proteasomal DUB inhibitors: rational design, natural compounds, and drug reposition. Compounds created through rational design are potentially novel and distinct, and usually patented. On the other hand, discovery of natural proteasomal DUB inhibitors was done through screening common compounds in nature, and drug reposition utilized old drugs for other purposes but with a new focus on their anticancer activity. Nonetheless, many challenges have arisen. For example, as the proteasomal DUBs UCHL5 and USP14 have a very similar active site, many researchers have had a difficult time creating a therapy specific to only one DUB. Additionally, many of the compounds do not have sufficient basic science research and therefore their effects could not be validated and they could not be progressed through the drug discovery process to become actual therapeutics. Thus, more work will be needed in order to discover and develop potent, specific proteasomal DUB inhibitors as novel anticancer drugs.

Future perspective

With the UPS structurally analyzed, many new proteins were identified as potential targets for modulating the ubiquitination/deubiquitination processes. DUBs have a significant role in the UPS. While there has been a substantial characterization of DUBs in recent years, there is still much work to be done. The regulatory properties of DUBs are sources from which diseases and cancer can be exploited. However, these regulatory properties of DUBs may be also used to reverse malicious processes. Thus, not only is the creation of DUB inhibitors crucial to potential treatments of diseases but it could potentially illuminate the mechanisms by which certain disease occurs. Through disabling DUBs in certain processes, the pathway a process occurs may be fully characterized thus leading to potentially more targets. The precise mechanism in which DUBs should be further explored as it is not completely understood currently. This will be achieved through better inhibitors and improved assaying.

While there have been advances in drug discovery and drug reposition for DUB inhibition, there may be challenges upon transition to the clinical field. Issues such as absorption and bioavailability have and may arise. Additionally, solubility may be an issue which would render the compound ineffective or potentially toxic. At this time, only proteasomal DUB inhibitor VLX1570 has entered a clinical trial. Drugs, such as WP1130, show promise but they are limited by poor selectivity. Issues regarding selectivity may be tackled through modification of the previously discussed compounds. This, however, requires knowledge of how compounds interact with targets. This could be achieved through crystal structure and modeling with rationally designed drugs. Thus, increased DUB-specific basic laboratory work must be completed to isolate and further characterize selectivity, activity and specificity. Ultimately, properties like toxicity must be addressed for discovery to translate into the clinical field.

Executive summary.

The ubiquitin proteasome system, 26S proteasome, 20S central catalytic core & 19S regulatory particle

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) consists of ubiquitin and 26S proteasome, which is made of the 20S proteasome and 19S proteasome. The 19S proteasome have three associated deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs): USP14, UCHL5 and RPN11 that are responsible for removal of ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like chains from the target protein, leading to increased levels of stability or degradation.

The DUBs of the 19S regulatory particle & their association with cancer/tumor activity

DUBs are an important regulator in tumor progression. Overexpression of proteasomal DUBs made them an important target for anticancer therapy.

Targeting the pathways of cancer progression (such as the UPS) may be more effective treatment strategy than targeting solid tumors.

Relevant 20S proteasome inhibitors

There are 20S proteasome inhibitors clinical setting such as bortezomib that approved by the US FDA for treatment of multiple myeloma. However, major issues have arisen after application of bortezomib such as toxic side effects and drug resistance.

There have been several other proteasome inhibitors such as carfilzomib and ONX-0912 in attempts to treat bortezomib-resistant cancers, which are either approved or in clinical trials.

Designing 19S DUB inhibitors

Inhibitors of the 19S could be developed as novel anticancer drugs and to overcome bortezomib resistance.

Currently, DUB inhibition has been studied through the rational design, natural compounds and drug reposition.

Drugs such as IU1, b-AP15, VLX1570, azepan-4-ones, RA-9 and capzimin were designed and synthesized to specifically target proteasome-associated DUBs for further characterizing DUB processes and their potential anticancer properties. VLX1570 is being tested in a clinical multiple myeloma trial.

Natural compounds as cancer prevention & cancer therapy through targeting the DUBs

Isothiocyanates are seen to inhibit UCHL5, USP14 and USP9X.

Isothiocyanates increased ubiquitination of the oncogenic protein Bcr-Abl.

Drug reposition: turning old research into new discovery

Metal complexes were identified as potential anticancer drugs and proteasomal DUB inhibitors through the repurposing of the FDA approved old drugs including disulfiram. This discovery fueled the research of metal complex inhibitors. Additionally, studies have found significant anticancer activity with metals complexed with dithiocarbonates, pyrithione and auranofin.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

This work was partially supported by National Cancer Institute grant R21CA184788 (to QP Dou) and NIH grant P30 CA022453 (to the Karmanos Cancer Institute at Wayne State University) as well as Karmanos internal funds. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest; •• of considerable interest

- 1.Hershko A, Heller H, Elias S, Ciechanover A. Components of ubiquitin-protein ligase system. Resolution, affinity purification, and role in protein breakdown. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258(13):8206–8214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groll M, Heinemeyer W, Jager S, et al. The catalytic sites of 20S proteasomes and their role in subunit maturation: a mutational and crystallographic study. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96(20):10976–10983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.10976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen LK, Kolch W, Kholodenko BN. When ubiquitination meets phosphorylation: a systems biology perspective of EGFR/MAPK signalling. Cell Commun. Signal. 2013;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: a molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arendt CS, Hochstrasser M. Eukaryotic 20S proteasome catalytic subunit propeptides prevent active site inactivation by N-terminal acetylation and promote particle assembly. EMBO J. 1999;18(13):3575–3585. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.13.3575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee MJ, Lee BH, Hanna J, King RW, Finley D. Trimming of ubiquitin chains by proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzymes. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(5) doi: 10.1074/mcp.R110.003871. R110 003871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amerik AY, Hochstrasser M. Mechanism and function of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1695(1–3):189–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wei R, Liu X, Yu W, et al. Deubiquitinases in cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(15):12872–12889. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liao Y, Liu N, Hua X, et al. Proteasome-associated deubiquitinase ubiquitin-specific protease 14 regulates prostate cancer proliferation by deubiquitinating and stabilizing androgen receptor. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(2):e2585. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, et al. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123(5):773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao T, Cohen RE. A cryptic protease couples deubiquitination and degradation by the proteasome. Nature. 2002;419(6905):403–407. doi: 10.1038/nature01071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leggett DS, Hanna J, Borodovsky A, et al. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol. Cell. 2002;10(3):495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verma R, Chen S, Feldman R, et al. Proteasomal proteomics: identification of nucleotide-sensitive proteasome-interacting proteins by mass spectrometric analysis of affinity-purified proteasomes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11(10):3425–3439. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peth A, Besche HC, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitinated proteins activate the proteasome by binding to Usp14/Ubp6, which causes 20S gate opening. Mol. Cell. 2009;36(5):794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yao T, Song L, Xu W, et al. Proteasome recruitment and activation of the Uch37 deubiquitinating enzyme by Adrm1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8(9):994–1002. doi: 10.1038/ncb1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamazaki J, Iemura S, Natsume T, Yashiroda H, Tanaka K, Murata S. A novel proteasome interacting protein recruits the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 to 26S proteasomes. EMBO J. 2006;25(19):4524–4536. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Chen X, Elsasser S, et al. Rpn1 provides adjacent receptor sites for substrate binding and deubiquitination by the proteasome. Science. 2016;351(6275) doi: 10.1126/science.aad9421. pii: aad9421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chernova TA, Allen KD, Wesoloski LM, Shanks JR, Chernoff YO, Wilkinson KD. Pleiotropic effects of Ubp6 loss on drug sensitivities and yeast prion are due to depletion of the free ubiquitin pool. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278(52):52102–52115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310283200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shabek N, Herman-Bachinsky Y, Ciechanover A. Ubiquitin degradation with its substrate, or as a monomer in a ubiquitination-independent mode, provides clues to proteasome regulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(29):11907–11912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905746106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuo CL, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitinated proteins promote the association of proteasomes with the deubiquitinating enzyme Usp14 and the ubiquitin ligase Ube3c. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114(17):e3404–e3413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1701734114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mazumdar T, Gorgun FM, Sha Y, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity and inducible nitric oxide synthase by regulatory particle non-ATPase subunit 13 (Rpn13) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107(31):13854–13859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913495107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ventii KH, Wilkinson KD. Protein partners of deubiquitinating enzymes. Biochem. J. 2008;414(2):161–175. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu XB, Ouyang SY, Li CJ, Miao S, Wang L, Goldberg AL. hRpn13/ADRM1/GP110 is a novel proteasome subunit that binds the deubiquitinating enzyme, UCH37. EMBO J. 2006;25(24):5742–5753. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muratani M, Tansey WP. How the ubiquitin-proteasome system controls transcription. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2003;4(3):192–201. doi: 10.1038/nrm1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin J, Cai Y, Yao T, et al. A mammalian chromatin remodeling complex with similarities to the yeast INO80 complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280(50):41207–41212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verma R, Aravind L, Oania R, et al. Role of Rpn11 metalloprotease in deubiquitination and degradation by the 26S proteasome. Science. 2002;298(5593):611–615. doi: 10.1126/science.1075898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lam YA, Xu W, Demartino GN, Cohen RE. Editing of ubiquitin conjugates by an isopeptidase in the 26S proteasome. Nature. 1997;385(6618):737–740. doi: 10.1038/385737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chauhan D, Bianchi G, Anderson KC. Targeting the UPS as therapy in multiple myeloma. BMC Biochem. 2008;9(Suppl. 1):S1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-S1-S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song Y, Li S, Ray A, et al. Blockade of deubiquitylating enzyme Rpn11 triggers apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells and overcomes bortezomib resistance. Oncogene. 2017;36(40):5631–5638. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu H, Buus R, Clague MJ, Urbe S. Regulation of ErbB2 receptor status by the proteasomal DUB POH1. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z, Niu X, Li Z, et al. Effect of ubiquitin carboxy-terminal hydrolase 37 on apoptotic in A549 cells. Cell Biochem. Funct. 2011;29(2):142–148. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shinji S, Naito Z, Ishiwata S, et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 14 expression in colorectal cancer is associated with liver and lymph node metastases. Oncol. Rep. 2006;15(3):539–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mines MA, Goodwin JS, Limbird LE, Cui FF, Fan GH. Deubiquitination of CXCR4 by USP14 is critical for both CXCL12-induced CXCR4 degradation and chemotaxis but not ERK ativation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284(9):5742–5752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808507200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D'Arcy P, Wang X, Linder S. Deubiquitinase inhibition as a cancer therapeutic strategy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015;147:32–54. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussain S, Zhang Y, Galardy PJ. DUBs and cancer: the role of deubiquitinating enzymes as oncogenes, non-oncogenes and tumor suppressors. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(11):1688–1697. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.11.8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Wang J, Zhong J, et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 14 (USP14) regulates cellular proliferation and apoptosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Med. Oncol. 2015;32(1):379. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Bortezomib: a novel therapy approved for multiple myeloma. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2003;1(10):596–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Connor OA, Wright J, Moskowitz C, et al. Phase II clinical experience with the novel proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23(4):676–684. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laubach JP, Mitsiades CS, Roccaro AM, Ghobrial IM, Anderson KC, Richardson PG. Clinical challenges associated with bortezomib therapy in multiple myeloma and Waldenstroms macroglobulinemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 2009;50(5):694–702. doi: 10.1080/10428190902866732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oerlemans R, Franke NE, Assaraf YG, et al. Molecular basis of bortezomib resistance: proteasome subunit beta5 (PSMB5) gene mutation and overexpression of PSMB5 protein. Blood. 2008;112(6):2489–2499. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Franke NE, Niewerth D, Assaraf YG, et al. Impaired bortezomib binding to mutant beta5 subunit of the proteasome is the underlying basis for bortezomib resistance in leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2012;26(4):757–768. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruckrich T, Kraus M, Gogel J, et al. Characterization of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in bortezomib-adapted cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(6):1098–1105. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nawrocki ST, Carew JS, Dunner K, Jr, et al. Bortezomib inhibits PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase and induces apoptosis via ER stress in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(24):11510–11519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hagenbuchner J, Ausserlechner MJ, Porto V, et al. The anti-apoptotic protein BCL2L1/Bcl-xL is neutralized by pro-apoptotic PMAIP1/Noxa in neuroblastoma, thereby determining bortezomib sensitivity independent of prosurvival MCL1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285(10):6904–6912. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.038331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Premkumar DR, Jane EP, DiDomenico JD, Vukmer NA, Agostino NR, Pollack IF. ABT-737 synergizes with bortezomib to induce apoptosis, mediated by Bid cleavage, Bax activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction in an Akt-dependent context in malignant human glioma cell lines. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2012;341(3):859–872. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.191536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.San Miguel JF, Schlag R, Khuageva NK, et al. Bortezomib plus melphalan and prednisone for initial treatment of multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008;359(9):906–917. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gourzones-Dmitriev C, Kassambara A, Sahota S, et al. DNA repair pathways in human multiple myeloma: role in oncogenesis and potential targets for treatment. Cell Cycle. 2013;12(17):2760–2773. doi: 10.4161/cc.25951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuhn DJ, Chen Q, Voorhees PM, et al. Potent activity of carfilzomib, a novel, irreversible inhibitor of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, against preclinical models of multiple myeloma. Blood. 2007;110(9):3281–3290. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-065888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chauhan D, Singh AV, Aujay M, et al. A novel orally active proteasome inhibitor ONX 0912 triggers in vitro and in vivo cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;116(23):4906–4915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-276626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Piva R, Ruggeri B, Williams M, et al. CEP-18770: a novel, orally active proteasome inhibitor with a tumor-selective pharmacologic profile competitive with bortezomib. Blood. 2008;111(5):2765–2775. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez E, Li M, Steinberg JA, et al. The proteasome inhibitor CEP-18770 enhances the anti-myeloma activity of bortezomib and melphalan. Br. J. Haematol. 2010;148(4):569–581. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.08008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakai K, Satoh M, Hirano M, et al. Clinical evaluation of ECG R-R interval variation in normal person and patients with coronary artery diseases. Rinsho. Byori. 1986;34(3):339–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas S, Quinn BA, Das SK, et al. Targeting the Bcl-2 family for cancer therapy. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2013;17(1):61–75. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.733001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borodovsky A, Kessler BM, Casagrande R, Overkleeft HS, Wilkinson KD, Ploegh HL. A novel active site-directed probe specific for deubiquitylating enzymes reveals proteasome association of USP14. EMBO J. 2001;20(18):5187–5196. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rivard C, Bazzaro M. Measurement of deubiquitinating enzyme activity via a suicidal HA-Ub-VS probe. Methods Mol. Biol. 2015;1249:193–200. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2013-6_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• Describes methods to measuring deubiquitinating enzyme (DUB) activity. These methods are widely used to further characterize DUB processes and evaluate potential inhibition. Many in the field use this technique to evaluate potential DUB inhibitors.

- 56.Lee BH, Lee MJ, Park S, et al. Enhancement of proteasome activity by a small-molecule inhibitor of USP14. Nature. 2010;467(7312):179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature09299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boselli M, Lee BH, Robert J, et al. An inhibitor of the proteasomal deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 induces tau elimination in cultured neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292(47):19209–19225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.815126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.D'Arcy P, Brnjic S, Olofsson MH, et al. Inhibition of proteasome deubiquitinating activity as a new cancer therapy. Nat. Med. 2011;17(12):1636–1640. doi: 10.1038/nm.2536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tian Z, D'Arcy P, Wang X, et al. A novel small molecule inhibitor of deubiquitylating enzyme USP14 and UCHL5 induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma and overcomes bortezomib resistance. Blood. 2014;123(5):706–716. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-05-500033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X, D'Arcy P, Caulfield TR, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of derivatives of the proteasome deubiquitinase inhibitor b-AP15. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2015;86(5):1036–1048. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paulus A, Akhtar S, Caulfield TR, et al. Coinhibition of the deubiquitinating enzymes, USP14 and UCHL5, with VLX1570 is lethal to ibrutinib- or bortezomib-resistant Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia tumor cells. Blood Cancer J. 2016;6(11):e492. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2016.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Linder S, Larsson R. Method for inhibition of deubiquitinating activity. 2013. WO/2013/058691.

- 63.Issaenko OA, Amerik AY. Chalcone-based small-molecule inhibitors attenuate malignant phenotype via targeting deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(9):1804–1817. doi: 10.4161/cc.20174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coughlin K, Anchoori R, Iizuka Y, et al. Small-molecule RA-9 inhibits proteasome-associated DUBs and ovarian cancer in vitro and in vivo via exacerbating unfolded protein responses. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20(12):3174–3186. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brandt WW, Dwyer FP, Gyarfas ED. Chelate complexes of 1,10-phenanthroline and related compounds. Chem. Rev. 1954;54(6):959–1017. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guterman A, Glickman MH. Complementary roles for Rpn11 and Ubp6 in deubiquitination and proteolysis by the proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(3):1729–1738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307050200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li J, Yakushi T, Parlati F, et al. Capzimin is a potent and specific inhibitor of proteasome isopeptidase Rpn11. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017;13(5):486–493. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; •• As RPN11's specificity has been difficult to achieve, Li et al. studied capzimin an analog to 8-thioquioline. While capzimin is a zinc chelator, it can potentially interact with the catalytic active site of RPN11 to increase specificity. This reference highlights the difficulty of developing a potent RPN11 inhibitor that is specific and nontoxic, thus stressing the importance of RPN11 inhibition.

- 68.Kapuria V, Peterson LF, Fang D, Bornmann WG, Talpaz M, Donato NJ. Deubiquitinase inhibition by small-molecule WP1130 triggers aggresome formation and tumor cell apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(22):9265–9276. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sun H, Kapuria V, Peterson LF, et al. Bcr-Abl ubiquitination and USP9X inhibition block kinase signaling and promote CML cell apoptosis. Blood. 2011;117(11):3151–3162. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-276477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Peterson LF, Sun H, Liu Y, et al. Targeting deubiquitinase activity with a novel small-molecule inhibitor as therapy for B-cell malignancies. Blood. 2015;125(23):3588–3597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-605584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chauhan D, Tian Z, Nicholson B, et al. A small molecule inhibitor of ubiquitin-specific protease-7 induces apoptosis in multiple myeloma cells and overcomes bortezomib resistance. Cancer Cell. 2012;22(3):345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Crankshaw MW, Grant GA. Modification of cysteine. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 1996;3(1):15.1.1–15.1.18. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1501s03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hjerpe R, Aillet F, Lopitz-Otsoa F, Lang V, England P, Rodriguez MS. Efficient protection and isolation of ubiquitylated proteins using tandem ubiquitin-binding entities. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(11):1250–1258. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]