Abstract

Objective

Several pull-through procedures have been described for Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) with varying outcomes. We aimed to describe the outcomes in HSCR patients < 18 year of age who underwent surgical procedures at Dr. Sardjito Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia from January 2013 to December 2014.

Results

We utilized 67 HSCR patients, of whom 49 (73%) were males and 18 (27%) females. Neonatal presentation was seen in 57 cases (85%) and most patients (98.5%) had short-segment HSCR. The clinical manifestations were mainly abdominal distension (94%) and delayed passage of meconium (45%). The most common definitive treatment performed was transanal endorectal pull-through (TEPT) (54%), followed by Soave (18%) and Duhamel (13%) procedures. Enterocolitis occurred in 13% of the HSCR patients after endorectal pull-through, but did not reach a significant level (p-value = 0.65), while the constipation rate was significantly higher in HSCR patients who underwent posterior neurectomy compared with those other procedures (OR = 15.5, 95% CI = 1.8–132.5; p-value = 0.019). In conclusions, most HSCR patients in Indonesia were diagnosed in the neonatal period and underwent the TEPT procedure. Furthermore, the risk of constipation is increased in HSCR patients following posterior neurectomy compared with other definitive surgical techniques.

Keywords: Constipation, Enterocolitis, Hirschsprung disease, Definitive surgery

Introduction

Hirschsprung disease (HSCR), which is characterized by the absence of ganglion cells (Meissnerr and Auerbach) along variable lengths of the distal gastrointestinal tract, is a common cause of neonatal intestinal obstruction, which is of great interest to pediatric surgeons throughout the world [1]. This disorder can be classified as follows: (1) short-segment (aganglionosis is confined to the rectosigmoid colon), (2) long-segment (aganglionic segment extends proximal to the sigmoid), and (3) total colonic aganglionosis [1].

Recently, a common variant within the RET gene, rs2435357, has been associated with HSCR across populations [2–6]. This variant lies within a conserved transcriptional enhancer of RET and has been shown to disrupt a SOX10 binding site within MCS + 9.7 that reduces RET gene expression, an underlying defect in HSCR [2].

The present management for HSCR is removal of the aganglionic segment of the intestines. Several definitive surgeries have been established for HSCR such as transabdominal endorectal pull-through (Soave), Duhamel, transanal endorectal pull-through (TEPT), transanal Swenson-like, and posterior neurectomy procedures [7–11], with varying outcomes [12]. Therefore, we aim to describe the outcomes, constipation and enterocolitis, in HSCR patients following a definitive surgery in Indonesia.

Main text

Methods

Patients

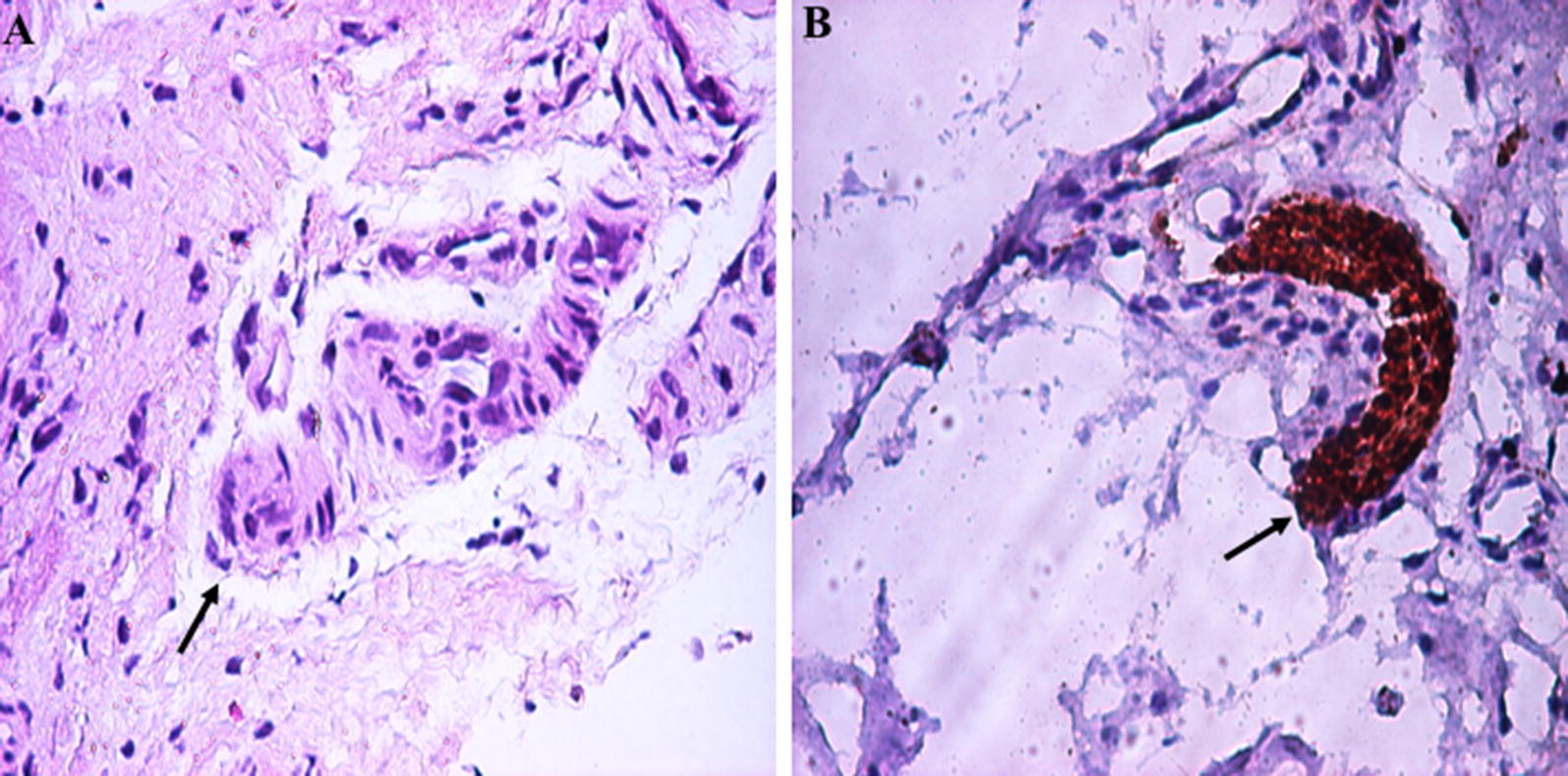

Medical records of histopathologically (Fig. 1) diagnosed HSCR patients in Dr. Sardjito Hospital, Indonesia during the study period of January 2013 and December 2014 were evaluated [13]. For the HSCR incidence calculation, we only utilized the patients from Yogyakarta province.

Fig. 1.

Histopathological findings of full-thickness rectal biopsy in a patient with Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) showed hypertrophic nerve trunk and no ganglion cells (arrow): a hematoxylin and eosin staining (×200), b S100 immunohistochemistry (×200)

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital (#KE/FK/232/EC). Written informed consent forms were completed by all parents before participation in this study.

Definitive surgical procedures

The Soave, Duhamel, or TEPT techniques were performed at our hospital based on previous studies [7–9], while the posterior neurectomy method has been described in our recent report [11].

Constipation and enterocolitis

Constipation was classified according to Krickenbeck category [14], whereas the enterocolitis diagnosis was determined using the Delphi score system [13, 15].

Results

In this study, we have ascertained 67 HSCR patients of whom 49 and 18 were males and females, respectively. This gives a male-to-female ratio of 2.7:1. The number of new HSCR cases from Yogyakarta province in 2013 was 14, while the number of newborns in 2013 in Yogyakarta province was 45,436 [16]. Therefore, the incidence of HSCR in Yogyakarta, Indonesia based on the annual number of cases divided by the annual number of newborns was approximately 1:3250.

All patients were sporadic HSCR, except one, with degree of aganglionosis as follows: short-segment in 66 (98.5%) patients, long-segment in 1 (1.5%) patients and total colonic aganglionosis was none. The long-segment patient was a sporadic HSCR case and from Yogyakarta province, while the familial HSCR case was also from Yogyakarta province. Neonatal presentation was seen in 56 (84%) patients, whereas 5 (8%), 3 (4%), 2 (3%), and 1 (1%) cases presented as infant, toddler, child, and adolescent, respectively. The clinical manifestations were mainly abdominal distension (94%) and delayed passage of meconium (45%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with HSCR in Indonesia

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 49 (73) |

| Female | 18 (27) |

| Age distribution | |

| Neonate | 56 (84) |

| Infant | 5 (8) |

| Toddler | 3 (4) |

| Child | 2 (3) |

| Adolescent | 1 (1) |

| Aganglionosis type | |

| Short-segment | 66 (98.5) |

| Long-segment | 1 (1.5) |

| Total colonic aganglionosis | 0 |

| Clinical manifestation | |

| Abdominal distension | 63 (94) |

| Delayed meconium passage (> 24 h) | 30 (45) |

HSCR Hirschsprung disease

A definitive surgery was performed in 39 infants, twenty-eight underwent a colostomy and a full-thickness rectal biopsy awaiting pull-through procedure. All cases were histopathologically proven as HSCR prior to any surgery (Fig. 1). The TEPT procedure has been the most common operation (54%), followed by Soave (18%), and Duhamel (13%) procedures. One patient underwent posterior myectomy, while a posterior neurectomy was performed in 13% of the HSCR patients.

Enterocolitis occurred in 15% of the HSCR patients, with the highest rate (13%) after endorectal pull-through, but did not reach a significant level (p-value = 0.65) Constipation frequency after surgery was 15%, and most of them (7.5%) underwent posterior neurectomy (p-value = 0.019) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Surgical procedures and outcomes in patients with HSCR in Indonesia

| Definitive surgery and outcomes | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitive surgery | 39 (58) | ||

| TEPT | 21 (54) | ||

| Soave | 7 (18) | ||

| Duhamel | 5 (13) | ||

| Posterior neurectomy | 5 (13) | ||

| Posterior myectomy | 1 (2) | ||

| Outcomes after surgery (N = 39) | |||

| Enterocolitis | 6 (15) | ||

| TEPT | 3 (7.5) | 2.2 (0.2–21.1) | 0.65 |

| Soave | 2 (5) | ||

| Duhamel | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Posterior neurectomy | 0 | ||

| Posterior myectomy | 0 | ||

| Constipation | 6 (15) | ||

| Posterior neurectomy | 3 (7.5) | 15.5 (1.8–132.5) | 0.019* |

| TEPT | 1 (2.5) | ||

| Soave | 0 | ||

| Duhamel | 2 (5) | ||

| Posterior myectomy | 0 | ||

| Characteristic and surgical outcomes | Yogyakarta province (%) | Outside province (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | N = 30 | N = 37 | |

| Neonate | 26 (87) | 32 (86) | 1.00 |

| Post-neonate | 4 (13) | 5 (14) | |

| Outcomes after surgery | N = 17 | N = 22 | |

| Enterocolitis | 2 | 4 | 0.68 |

| Constipation | 2 | 4 | 0.68 |

| Characteristic and surgical outcomes | Male (%) | Female (%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age distribution | N = 49 | N = 18 | |

| Neonate | 42 | 16 | 1.00 |

| Post-neonate | 7 | 2 | |

| Definitive surgery | N = 31 | N = 8 | |

| TEPT | 16 | 5 | 0.70 |

| Soave | 7 | 0 | |

| Duhamel | 4 | 1 | |

| Posterior neurectomy | 3 | 2 | |

| Posterior myectomy | 1 | 0 | |

| Outcomes after surgery | N = 31 | N = 8 | |

| Enterocolitis | 6 | 0 | 0.31 |

| Constipation | 3 | 3 | 0.09 |

HSCR Hirschsprung disease, TEPT transanal endorectal pull-through

*Significant (p-value < 0.05)

Furthermore, there were no significant differences between the Yogyakarta and outside province HSCR cases in term of the age distribution of diagnosis, enterocolitis and constipation rates after definitive surgery (p-value = 1.00, 0.68, and 0.68, respectively) (Table 2). The age distribution of diagnosis, type of definitive surgery, enterocolitis and constipation rates after surgery were also comparable between male and female HSCR patients (p-value = 1.00, 0.70, 0.31, and 0.09, respectively) (Table 2).

Discussion

We showed evidence that the incidence of HSCR in Yogyakarta, Indonesia is higher than other regions [17, 18], even compared with other Asian countries [19]. It might relate to Indonesian genetic structure ethnicity [20, 21]. Recently, our studies showed that Indonesian controls have a high frequency of RET rs2435357 risk allele (0.50) [3], which was higher than those in the European and the African ancestry individuals (0.25 vs. 0.01) [22]. The high incidence of HSCR in Indonesia could also be caused by improved ascertainment due to the establishment of more accurate registry in our hospital or due to advancement in diagnosis and coding over time. However, this data should be interpreted with carefulness since this high incidence may not have a clinical significance [20].

Familial history has been reported in ~ 40% of HSCR cases, particularly with total colon aganglionosis and in female patients [23]. In this study, there was only one patient with family history of HSCR. The patient and affected sibling are females, but presented with short-segment aganglionosis.

The majority of HSCR cases of our study were diagnosed in the neonatal period (85%), which is similar to that of a previous study in Europe (78.5%) [20]. However, our study showed different results from studies from Burkino Faso [17] and Japan [19], where the diagnosis of HSCR was made in the neonatal period in 36% and 40.1–53.4% cases, respectively. Furthermore, in Australia, the percentage of HSCR cases being diagnosed in the neonatal period is higher (90.5%) than in Indonesia [18]. Our study might imply that the HSCR in our hospital has been early diagnosed. Furthermore, our hospital is one of the tertiary referral hospitals in Indonesia. Nevertheless, early diagnosis is important to prevent complications, especially enterocolitis, a significant cause of mortality [24].

Formerly, the neonates diagnosed with HSCR underwent colostomy and waited until 6–12 months later for definitive pull-through. However, this approach has altered greatly over three decades, and the primary pull-through is becoming popular among pediatric surgeons worldwide, in which the TEPT is the most commonly performed procedure [24]. Our study showed a similar trend that the TEPT procedure has been the commonest operation in our hospital.

In this study, the enterocolitis frequency (15%) following definitive surgery was relatively similar with other studies (14–20%) [10, 19], with the highest rate in our HSCR patients (13%) after endorectal pull-through. It has been shown that the enterocolitis is a more complex disease that will not be solely resolved by the type of surgery chosen [13, 24].

The constipation frequency varied from 6 to 34% [25]. Our cohort patients showed post-operative constipation of 15%, which was comparable with a previous study (10%) [12]. In addition, the highest constipation rates were in the patients who underwent posterior neurectomy (7.5%). This result might be due to not performing resection of the aganglionic colon during posterior neurectomy [11].

Conclusions

Most HSCR patients in Indonesia were diagnosed in the neonatal period and underwent the TEPT procedure. Furthermore, the risk of constipation is increased in HSCR patients following posterior neurectomy compared with other definitive surgical techniques.

Limitation

A possible limitation of the study involves having only extracted information retrospectively from available medical records.

Authors’ contributions

G, AD, and SMK conceived the study. G drafted the manuscript. G and SMK collected the data, and G analyzed it. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families who have contributed in these studies. We are also grateful to a native speaker at English Services Center, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, for editing the grammar and proofreading of our manuscript. We are also thankful to Harini Natalia (Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital) for ethical clearance management and to all those who took part in the management of these patients.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the submission. The raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee of Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital permitted this study (#KE/FK/232/EC). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents for participating this study.

Funding

The work was supported by a grant from the Director General for the Strengthening of Research and Development, Indonesian Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education (“1700/UN1/DITLIT/DIT-LIT/LT/2018” to G.).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- HSCR

Hirschsprung disease

- TEPT

transanal endorectal pull-through

Contributor Information

Gunadi, Phone: +62-274-631036, Email: drgunadi@ugm.ac.id.

Stefani Melisa Karina, Email: stefani_melisa_karina@hotmail.com.

Andi Dwihantoro, Email: iba.fk@ugm.ac.id.

References

- 1.Chakravarti A, Lyonnet S, et al. Hirschsprung disease. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Sly WS, Childs B, Kinzler K, et al., editors. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 6231–6255. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Emison ES, Garcia-Barcelo M, Grice EA, et al. Differential contributions of rare and common, coding and noncoding Ret mutations to multifactorial Hirschsprung disease liability. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gunadi, Kapoor A, Ling AY, et al. Effects of RET and NRG1 polymorphisms in Indonesian patients with Hirschsprung disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1614–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gunadi, Dwihantoro A, Iskandar K, Makhmudi A. Rochadi. Accuracy of polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism for RET rs2435357 genotyping as Hirschsprung risk. J Surg Res. 2016;203:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2016.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang D, Yang J, Li S, Jiang M, et al. Effects of RET, NRG1 and NRG3 Polymorphisms in a Chinese Population with Hirschsprung Disease. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43222. doi: 10.1038/srep43222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virtanen VB, Salo PP, Cao J, et al. Noncoding RET variants explain the strong association with Hirschsprung disease in patients without rare coding sequence variant. Eur J Med Genet. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lefèvre JH, Parc Y. Soave procedure. J Visc Surg. 2011;148:e262–e266. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nah SA, de Coppi P, Kiely EM, et al. Duhamel pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: a comparison of open and laparoscopic techniques. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:308–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De La Torre L, Langer JC. Transanal endorectal pull-through for Hirschsprung disease: technique, controversies, pearls, pitfalls, and an organized approach to the management of postoperative obstructive symptoms. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2010;19:96–106. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahajan JK, Rathod KK, Bawa M, Narasimhan KL. Transanal Swenson’s operation for recto-sigmoid Hirschsprung’s disease. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2011;8:301–305. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.91678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rochadi, Haryana SM, Sadewa AH. Gunadi. Effect of RET c.2307T > G polymorphism on the outcomes of posterior sagittal neurectomy for Hirschsprung disease procedure in Indonesian population. Int Surg. 2014;99:802–806. doi: 10.9738/INTSURG-D-14-00082.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aworanti OM, Mcdowell DT, Martin IM, Hung J, Quinn F. Comparative review of functional outcomes post surgery for Hirschsprung’s disease utilizing the paediatric incontinence and constipation scoring system. Pediatr Surg Int. 2012;28:1071–1078. doi: 10.1007/s00383-012-3170-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parahita IG, Makhmudi A. Gunadi. Comparison of Hirschsprung-associated enterocolitis following Soave and Duhamel procedures. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53:1351–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holschneider A, Hutson J, Peña A, et al. Preliminary report on the international conference for the development of standards for the treatment of anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pastor AC, Osman F, Teitelbaum DH, et al. Development of a standardized definition for Hirschsprung’s-associated enterocolitis: a Delphi analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Health District Office of Yogyakarta Province, Indonesia. Yogyakarta’s health profile. dinkes.jogjaprov.go.id/files/64370-profil-kes-DIY-2012.pdf. Accessed 11 Feb 2017.

- 17.Bandré E, Kaboré RA, Ouedraogo I, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease: management problem in a developing country. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2010;7:166–168. doi: 10.4103/0189-6725.70418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh SJ, Croaker GD, Manglick P, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease: the Australian Paediatric Surveillance Unit’s experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:247–250. doi: 10.1007/s00383-002-0842-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suita S, Taguchi T, Ieiri S, Nakatsuji T. Hirschsprung’s disease in Japan: analysis of 3852 patients based on a nationwide survey in 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Best KE, Addor MC, Arriola L, et al. Hirschsprung’s disease prevalence in Europe: a register based study. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2014;100:695–702. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunadi, Makhmudi A, Agustriani N. Rochadi. Effects of SEMA3 polymorphism in Hirschsprung disease patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32:1025–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00383-016-3953-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–1073. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moore SW, Zaahl MG. A review of genetic mutation in familial Hirschsprung’s disease in South Africa: towards genetic counseling. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:325–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teitelbaum DH, Coran AG. Hirschsprung disease. In: Spitz L, Coran AG, editors. Operative pediatric surgery. 7. New York: CRC Press; 2013. pp. 560–581. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Menezes M, Corbally M, Puri P. Long-term results of bowel function after treatment for Hirschsprung’s disease: a 29-year review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2006;22:987–990. doi: 10.1007/s00383-006-1783-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the submission. The raw data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.