Abstract

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) are anaerobic microorganisms, which use sulfate as an electron acceptor in the process of dissimilatory sulfate reduction. The final metabolic product of these anaerobic microorganisms is hydrogen sulfide, which is known as toxic and can lead to damage to epithelial cells of the large intestine at high concentrations. Different genera of SRB are detected in the large intestine of healthy human and animals, and with diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. SRB isolated from rodents with ulcerative colitis have produced 1.14 (mice) and 1.03 (rats) times more sulfide ions than healthy rodents. The species of Desulfovibrio genus are the most widespread among all SRB in the intestine. The object of our research was to observe and compare the difference of production of sulfide and reduction of sulfate in intestinal SRB isolated from healthy rodents and rodents with ulcerative colitis.

Keywords: Sulfate-reducing bacteria, Desulfovibrio genera, Hydrogen sulfide, Ulcerative colitis

1. Introduction

Sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) are anaerobic microorganisms, which use sulfate as an electron acceptor in the process of dissimilatory sulfate reduction. SRB are spread-wide not only in the environmental sources, but are also present in the digestive tract of humans and animals [1, 2, 3].

The dissimilatory sulfate reduction is a multistage and complex process which provides SRB cell’s energy with the formation of ATP. SRB consume sulfate as a terminal electron acceptor and due to the oxidation of organic compounds and hydrogen obtain energy for their growth [4, 5]. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is the final product of sulfate reduction [6].

Sulfate in food may be important in human metabolism. Free sulfate ions affect large bowel metabolism where it is reduced to hydrogen sulfide, a substance potentially toxic to the colonic epithelium [7]. Sulfate concentrations have therefore been measured in more than 200 individual foods and beverages [8]. High-sulfate foods (>10 μmol/g or 1 mg/g) include some breads, soya flour, some dried fruits, some brassicas, and some sausages. High-sulfate beverages (>2.5 μmol/ml or 0.25 mg/ml)) include some beers, ciders, and wines. The sulfate content of beer is discussed with particular relation to epidemiological observations which link ingestion of beer with colorectal cancer [8].

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) including ulcerative colitis (UC) or Crohn’s disease is characterized by chronic inflammation of the large intestine in genetically susceptible individuals of unknown etiology [9, 10]. One of the hypotheses is that UC is caused by the toxic molecule of H2S.

In persons with ankylosing spondylitis and, with rheumatic diseases, etc. are often found SRB [4, 11, 12, 13], which in large amounts can cause intense process of dissimilatory sulfate reduction in the gut leading to inflammatory bowel diseases [1, 7, 14]. On the other hand, the increased number of SRB was found in feces from people with ulcerative colitis compared with healthy individuals [15, 16, 17, 18, 19].

SRB, especially Desulfovibrio genus, has been studied for over a century because of their ubiquity and their important roles in chemical processes and elemental cycles [20]. Also, Desulfovibrio genus is the most common species of SRB and its species are most often isolated from the large intestine of human and animals [15, 21, 22].

Due to lack of information about dissimilatory sulfate reduction of intestinal SRB and its comparison between healthy and samples from ulcerative colitis, more observation was needed. In our research, we have been focused on production of hydrogen sulfide and decrease of sulfate ions during sulfate respiration in the samples from rodents with and without ulcerative colitis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Bacterial cultures

Crude cultures of intestinal SRB have been isolated from the intestine of rats and mice. The cultures have been kept in the collection of microorganisms at the Laboratory of Anaerobic Microorganisms of Department of Experimental Biology at Masaryk University (Brno, Czech Republic).

2.2. Bacterial growth and cultivation

Bacteria were grown in a nutrition-modified Postgate’s liquid medium “C” with the following composition (g/L) [23]: Na2SO4 (4.0), (NH4)2SO4 (0.2), MgSO4 × 7H2O (1.0), K2HPO4 (0.5), KH2PO4 (0.3), CaCl2 × 6H2O (0.06), NH4Cl (1.0), lactate (6 mL), yeast extract (1.0), sodium citrate × 2H2O (0.3). The final optimal pH 8 for cultivation of intestine SRB was provided by a sterile 1 M solution of NaOH (0.9 ml/l). The bacteria were grown for 72 hours at 37°C under anaerobic conditions [24].

2.3. Hydrogen sulfide assay

Hydrogen sulfide produced by intestinal SRB has been measured spectrophotometrically right after seeding and after 24 hours cultivation. Calibration solutions were prepared in distilled water at concentrations of 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μM of sodium sulfide. The calibration curve was constructed with the same process. A sample of volume 1 mL was added to 10 mL of a 5 g/L aqueous solution of zinc acetate. Right after, 2 mL of 0.75 g/mL p-aminodimethylaniline in a solution of sulfuric acid (2 M) was added. The mixture was left to stand for 5 minutes at room temperature. After that, 0.5 mL of 12 g/L solution of ferric chloride dissolved in 15 mM sulfuric acid was added. After standing another 5 minutes at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 5000 × g at 23°C. The absorbance of mixture was determined to measure hydrogen sulfide at a wavelength of 665 nm by spectrophotometer Spectrosonic Genesis 5. As a control, the measurement was repeated in the same manner using a cultivation medium [25].

2.4. Sulfate ions detection

The content of sulfate in the medium was determined by turbidimetric method right after seeding and after 24 hours cultivation. The calibration curve was constructed with the same process. Calibration solutions were prepared in distilled water at concentrations of 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 32, 40 and 48 μM sodium sulfate. A suspension of 40 mg/L BaCl2 was prepared in 0.12 M HCl. The resulting solution was mixed with glycerol in a 1:1 ratio. To the 1 mL of sample supernatant after centrifugation at 5000 × g at 23°C was added 10 mL of prepared BaCl2:glycerol solution and carefully stirred. The mixture was allowed to stand for 10 minutes and right after that the absorbance was measured at 520 nm (Spectrosonic Genesis 5). As a control, the measurement was repeated in the same manner using a cultivation medium [26].

2.5. DAPI

Morphological characteristics of intestinal SRB were evaluated by fluorescent DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2-fenylindol) straining. DAPI was used as cytochemical detection for bacterial DNA. This DNA-DAPI connection is visible in 365 nm [27].

2.6. Statistics

Statistical calculations of the results were carried out using the software MS Office, Origin and Statistica12 computer programs. Using the experimental data, the basic statistical parameters (mean: M, standard error: m, M ± m) were calculated. The research results were treated by methods of variation statistics using Student’s t-test. The significance of the calculated indicators was tested by Fisher’s F-test. The accurate approximation was when P≤ 0.05 [28].

3. Results

Crude samples of intestinal SRB were cultivated in the selective modified medium and after cultivation, vibrio like colonies was observed (Fig. 1). Therefore, these samples were subjected to measurement of metabolites of their dissimilatory sulfate reduction.

Figure 1.

The crude culture of intestinal SRB isolated from a mouse with ulcerative colitis (magnified 10,000 ×).

Detection and monitoring of sulfate reduction and production of sulfide in samples obtained from healthy rodents and rodents with ulcerative colitis for 24 hours cultivation were obtained. The percentage ratio of these data was calculated in every sample (Table 1.).

Table 1.

Concentrations of sulfate and sulfide in media with intestinal SRB from mice and rats for 24 hours cycle.

| SRB suspension from mice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | SO42- at the beginning [mM] | SO42- after 24 hours cultivation [mM] | SO42- decreased (%) | S2- after 24 hours cultivation [mM] | S2- produced (%) |

| Healthy | |||||

| 1 | 20.49±1.64 | 13.19±0.62 | 35.63 | 7.31±0.12 | 40.49 |

| 2 | 17.28±1.63 | 14.19±0.79 | 17.88 | 8.22±0.63 | 53.04 |

| 3 | 19.82±1.41 | 14.30±0.44 | 27.85 | 7.12±0.15 | 41.85 |

| 4 | 21.70±1.38 | 14.43±0.81 | 33.50 | 7.83±0.83 | 41.76 |

| 5 | 21.52±1.37 | 16.06±1.14 | 25.37 | 6.77±0.31 | 59.38 |

| 6 | 20.91±2.10 | 15.42±0.71 | 26.26 | 8.96±0.48 | 48.10 |

| 7 | 19.68±1.44 | 12.27±0.89 | 37.65 | 7.99±0.45 | 37.42 |

| Average | 20.27±1.56 | 14.06±0.77 | 29.38 | 7.74±0.30 | 45.92 |

| Ulcerative colitis | |||||

| 1 | 20.77±2.32 | 13.50±1.45 | 35.00 | 8.21±0.98 | 52.50 |

| 2 | 20.23±1.72 | 13.21±1.42 | 34.70 | 8.44±0.65 | 45.26 |

| Average | 20.50±2.02 | 13.35±1.44 | 34.85 | 8.32±0.82 | 48.83 |

| SRB suspension from rats | |||||

| Healthy | |||||

| 1 | 24.31±1.21 | 13.48±0.74 | 44.55 | 9.17±0.59 | 52.02 |

| 2 | 21.97±0.82 | 14.01±0.66 | 36,23 | 7.57±0.12 | 42.54 |

| Average | 23.14±1.02 | 13.75±0.70 | 40.60 | 8.37±0.36 | 47.73 |

| Ulcerative colitis | |||||

| 1 | 24.40±2.39 | 14.68±1.45 | 39.84 | 7.46±0.83 | 54.96 |

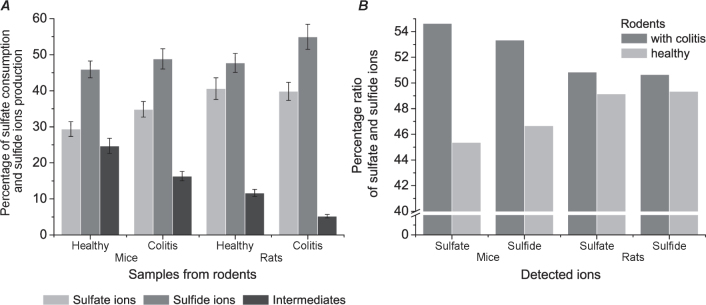

Sulfide production was increased in samples from mice and rats with UC, 4.06±0.34 and 4.10±0.46 mM, in comparison with healthy samples, 3.55±0.29 and 3.99±0.28 mM, respectively. However, sulfate reduction was increased in the same way, 7.15±0.75, 9.72±0.53 mM (UC) and 6.20±0.23, 9.40±0.36 mM (healthy). In intestinal SRB suspension from rats sulfate reduction was significantly increased with 9.40±0.36 and 9.72±0.53 mM compared with the suspension from mice at 6.20±0.23 and 7.15±0.75 mM. On the other hand, the production of sulfide is not as different as sulfate reduction. Based on the percentage ratio calculations for metabolites of dissimilatory sulfate reduction mentioned above, two graphs were drawn (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage ratio of sulfate reduction ions (A), the percentage of starting and final metabolites during sulfate-reduction (B) from healthy samples and samples with UC.

During sulfate reduction in samples from mice, intermediate compounds were 24.7 and 16.32 % of total compounds compared to samples from rats (11.67, 5.2 %) (Fig. 2A). Additionally, the differential percentage ratio between samples with colitis and healthy control is visible in samples from mice for sulfate states 54.63:45.37 % and for sulfide ions 49.15:50.85 % in comparison to samples from rats, 53.34:46.66%; 50.65:49.35% respectively (Fig. 2B).

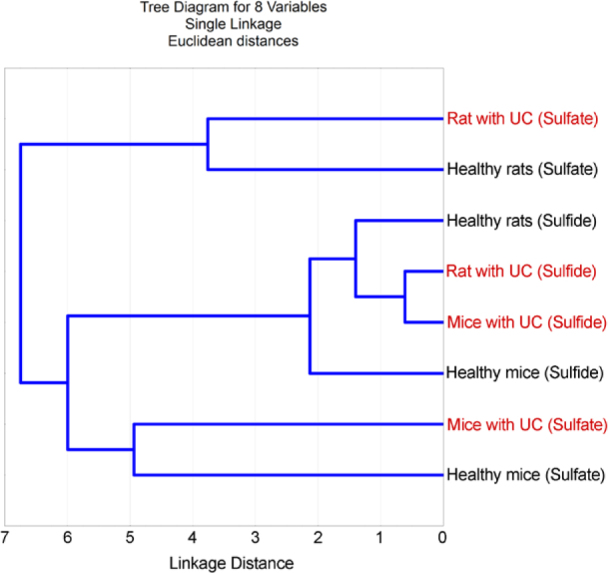

The diagram of cluster analysis shows that sulfate ions from healthy rodents are not as related to rodents with colitis as are sulfide ions (Fig. 3). However, samples with UC from both rodents have shorter linkage distance. Healthy control of sulfide ions is also incorporated into the same cluster as are with colitis.

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis of consuming sulfate and produced sulfide after 24 hours.

4. Discussion

The presence of intestinal SRB isolated from healthy human feces was previously presented by Moore et al. [21], Beerens and Romond [29], and by Gibson and his colleagues [15, 16], who also measured the rate of producing H2S. The lower percentage ratio of intermediate compounds in samples from rodents with colitis indicates that they faster convert incorporated sulfate ions to sulfide. This faster reduction of sulfate can be involved with enzymes of dissimilatory sulfate-reduction (adenosine-5′-phosphosulfate reductase and sulfite reductase) or even by other enzymes such as pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, Na+/K+-activated Mg2+-dependent ATP-hydrolase, acetate kinase, and phosphotransacetylase [5, 30, 31, 32]. However, the difference in sulfate consumption between samples with UC and healthy control is not significant, which indicates that sulfate is evenly transported to the bacterial cell.

The concentration of sulfate in the intestine depends on the food introduced. Oxidized forms of sulfur including sulfite and sulfate are present in food such as commercial bread, nuts, dried fruits and vegetables, brassica vegetable and fermented beverages. The sulfate mainly is in the free anionic form. About 2±15 mM of sulfate is passes through the human gastrointestinal tract every day by food. However, the concentration of sulfate ions in the feces is much lower and is it about 0.26 mM/day. It was also observed that 95% of sulfate is absorbed in the gastrointestinal tract and only 5% remains detected in the feces [8]. Other researchers have also reported that absorption of sulfate by the human gastrointestinal tract is believed to be bad [33, 34].

Due to the possible connection of the intestinal SRB to the development of UC various researches have studied synthesized organic compounds on their inhibition [35, 36, 37].

To conclude our research, differences in production of sulfide and reduction of sulfate in suspension of SRB from rodents with and without ulcerative colitis was observed. Differences in produced H2S are visible between samples with UC and healthy controls. The consumption of sulfate ions was not significant. The observed difference can lead to a better understanding of the etiology of the UC and association of SRB in its development.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grant Agency of the Masaryk University (MUNI/A/0906/2017)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest statement: Authors state no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Loubinoux J., Bronowicki J.-P., Pereira I.A., Mougenel J.-L., Faou A.E.. Sulfate-reducing bacteria in human feces and their association with inflammatory bowel diseases. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2002;40(2):107–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kushkevych I., Vítězová M., Vítěz T., Bartoš M.. Production of biogas relationship between methanogenic and sulfate-reducing microorganisms: relationship between methanogenic and sulfate-reducing microorganisms. Open Life Sciences. 2017;12(1):82–91. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kushkevych I., Kováč J., Vítězová M., Vítěz T., Bartoš M.. The diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the seven bioreactors. Archives of Microbiology. 2018;200(6):945–950. doi: 10.1007/s00203-018-1510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Barton L.L., Hamilton A.W. Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria Environmental and Engineered Systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kushkevych I., Fafula R., Parák T., Bartoš M.. Activity of Na+ / K+ -activated Mg2- -dependent ATP-hydrolase in the cell-free extracts of the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio piger Vib-7 and Desulfomicrobium sp. Rod-9. Acta Veterinaria Brno. 2015;84(1):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kushkevych I., Vítězová M., Fedrová M., Vochyanová Z., Paráková L., Hošek J.. Kinetic properties of growth of intestinal sulphate-reducing bacteria isolated from healthy mice and mice with ulcerative colitis. Acta Veterinaria Brno. 2017;86:405–411. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pitcher M., Beatty E., Gibson G., Cummings J.. Hydrogen Sulphide Production by Colonic Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria: A Luminal Toxin in Ulcerative Colitis? Clinical Science. 1995;89(33):26P.2–26P. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Florin T.H., Neale G., Goretski S., Cummings J. H.. Sulfate in food and beverages. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 1993;6(2):140–151. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Podolsky D.K.. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(6):417–429. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schirbel A., Fiocchi C.. Inflammatory bowel disease: Established and evolving considerations on its etiopathogenesis and therapy. Journal of Digestive Diseases. 2010;11(5):266–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2980.2010.00449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Cummings J., Macfarlane G., Macfarlane S.. Intestinal bacteria and ulcerative colitis. Current issues in intestinal microbiology. 2003;4(1):9–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sekirov I., Russell S.L., Antunes L.C., Finlay B.B.. Gut Microbiota in Health and Disease. Physiological Reviews. 2010;90(3):859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kushkevych I., Kollar P., Ferreira A.L., Palma D., Duarte A., Lopes M.M., Jampilek J.. Antimicrobial effect of salicylamide derivatives against intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2016;14(2):125–130. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Macfarlane S., Dillon J.. Microbial biofilms in the human gastrointestinal tract. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2007;102(5):1187–1196. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gibson G.R., Cummings J.H., Macfarlane G.T.. Growth and activities of sulphate-reducing bacteria in gut contents of healthy subjects and patients with ulcerative colitis. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 1991;9(2):103–111. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Gibson G.R., Macfarlane G.T., Cummings J.H.. Sulphate reducing bacteria and hydrogen metabolism in the human large intestine. Gut. 1993;34(4):437–439. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.4.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Levitt M.D., Furne J., Springfield J., Suarez F., DeMaster E.. Detoxification of hydrogen sulfide and methanethiol in the cecal mucosa. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1999;104(8):1107–1114. doi: 10.1172/JCI7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Macfarlane G.T., McBain A.J. Gibson G. R., Roberfroid M. B. Colonic Microbiota, Nutrition and Health. 1. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 1999. The Human Colonic Microbiota; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zinkevich V., Beech I.B.. Screening of sulfate-reducing bacteria in colonoscopy samples from healthy and colitic human gut mucosa. FEMS Microbiology Ecology. 2000;34(2):147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2000.tb00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Voordouw G.. Carbon Monoxide Cycling by Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184(21):5903–5911. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.21.5903-5911.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Moore W.E., Johnson J.L., Holdeman L.V.. Emendation of Bacteroidaceae and Butyrivibrio and Descriptions of Desulfomonas gen. nov. and Ten New Species in the Genera DesulfomonasButyrivibrioEubacteriumClostridium and Ruminococcus. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1976;26(2):238–252. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Willis C.L., Cummings J.H., Neale G., Gibson G.R.. Nutritional Aspects of Dissimilatory Sulfate Reduction in the Human Large Intestine. Current Microbiology. 1997;35(5):294–298. doi: 10.1007/s002849900257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Postgate J.R. The sulphate-reducing bacteria. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kováč J., Kushkevych I.. New modification of cultivation medium for isolation and growth of intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria. In MendelNet 2017 Proceedings of 24th International PhD Students Conference, Mendel University in Brno. 2017:702–707. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bailey T.S., Pluth M.D.. Chemiluminescent Detection of Enzymatically Produced Hydrogen Sulfide. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2013;135(44):16697–16704. doi: 10.1021/ja408909h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kolmert Å., Wikström P., Hallberg K.B.. A fast and simple turbidimetric method for the determination of sulfate in sulfate-reducing bacterial cultures. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2000;41(3):179–184. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(00)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Porter K.G., Feig Y.S.. The use of DAPI for identifying and counting aquatic microflora1. Limnology and Oceanography. 1980;25(5):943–948. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Bailey N.T.J. Statistical Methods in Biology. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1995. 252 p. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Beerens H., Romond C.. Sulfate-reducing anaerobic bacteria in human feces. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1977;30(11):1770–1776. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/30.11.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kushkevych I.. Acetate kinase Activity and Kinetic Properties of the Enzyme in Desulfovibrio piger Vib-7 and Desulfomicrobium sp. Rod-9 Intestinal Bacterial Strains. The Open Microbiology Journal. 2014;8(1):138–143. doi: 10.2174/1874285801408010138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kushkevych I.V.. Activity and kinetic properties of phospho-transacetylase from intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2015;62(1):103–108. doi: 10.18388/abp.2014_845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kushkevych I.V.. Kinetic Properties of Pyruvate Ferredoxin Oxidoreductase of Intestinal Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria Desulfovibrio piger Vib-7 and Desulfomicrobium sp. Rod-9. Polish J Microbiol. 2015;64:107–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wilson T. Intestinal absorption. Saunders; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Goodman L.S., Gilman A. The Pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 5th. New York: Macmillan; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kushkevych I., Kollar P., Suchy P., Parak K., Pauk K., Imramovsky A.. Activity of selected salicylamides against intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria. Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2015;36:106–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kushkevych I., Kos J., Kollar P., Kralova K., Jampilek J.. Activity of ring-substituted 8-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxanilides against intestinal sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio piger. Medicinal Chemistry Research. 2018;27(1):278–284. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Kushkevych I., Vítězová M., Kos J., Kollár P., Jampílek J.. Effect of selected 8-hydroxyquinoline-2-carboxanilides on viability and sulfate metabolism of Desulfovibrio piger. Journal of Applied Biomedicine. 2018;16(3):241–246. [Google Scholar]