Abstract

Context:

Acne vulgaris is a disorder showing persistent inflammation in the pilosebaceous follicles. It is one of the most prevalent dermatoses that millions of people suffer from globally.

Aim:

The aim of this study was to identify Candida species from patients with acne and to determine their drugs susceptibility.

Subjects and Methods:

A total of 70 cutaneous samples from acne vulgaris patients suspected to have Candida infections were collected. Macroscopic and microscopic morphology were recorded followed by polymerase chain reaction-sequencing of ITS regions, using universal primers. In vitro antifungal susceptibility was performed using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute method.

Results:

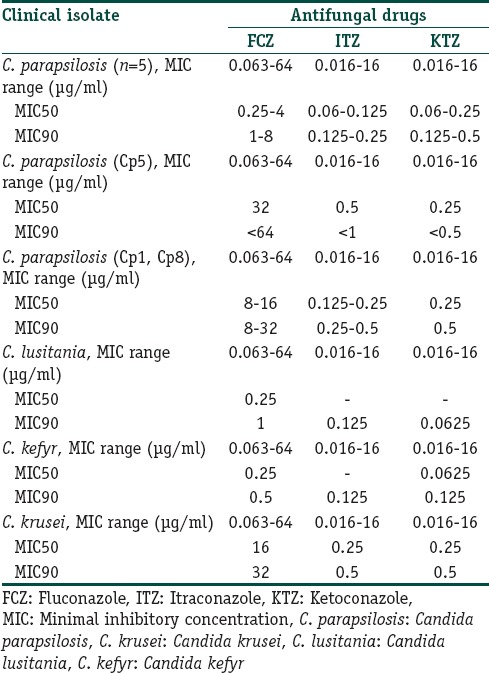

Overall, 11 Candida species including Candida parapsilosis 8 (72.73%), Candida krusei 1 (12.5%), Candida lusitaniae 1 (12.5%), Candida kefyr 1 (12.5%), and a Trichosporon asahi out of the collected clinical materials were isolated and identified. C. parapsilosis isolates susceptibility to diverse concentrations of the antifungal agents to isolate Cp1 study indicated that the isolated Cp8 and Cp5 with minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) 50 = 32, 0.5, 0.25 and MIC 90 of <64, <1, <0.5 μg/ml fluconazole, itraconazole, and ketoconazole were resistant, respectively. Some of the isolates having relative strength, almost all other species of C. parapsilosis isolates were susceptible to these drugs.

Conclusion:

C. parapsilosis was the most prevalent Candida species in acne vulgaris samples which had higher in vitro susceptibility for antifungals.

Keywords: Acne vulgaris, antifungal susceptibility, Candida

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disorder of the pilosebaceous follicle that appears on the face, neck, arms, back, and chest.[1] Acne vulgaris influences roughly 80% of adolescents and young adults often persisting well into adulthood and can bring about scarring and hyperpigmentation.[2] The main factors involved in the pathogenesis include higher levels of sebum production, the unnatural state of microbial flora inside the pilosebaceous unit. Faulty keratinization and inflammatory mediators of various bacterial or fungal agents contribute to acne, namely, Propionibacterium acnes, Propionibacterium granulosum, Prunus avium, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Malassezia sp.[1,2] The immunologic situation, hormone and genetic factors and many other factors such as anxiety, immunosuppression, pregnancy, menstruation, hot and humid weather, dirty skin, use of cosmetics, bad diet are the other factors which contribute to the outbreak and intensity of the acne. Propionibacterium acnes secrete several extracellular products that may be significant in the etiology of acne. The microenvironmental variation of the pilosebaceous duct influences the production and activity of inflammatory mediators such as lipase, muramidase, phosphatase, and protease.[3] Beside the patients’ suffering, the long-term consumption of different types of antibiotics may result in the higher number of resistance microbes and negative effects on economy.[1] On the other hand, those antibiotics, which are consumed to treat acne, may damage the normal bacterial flora of the skin and result in allowing the yeast to more growth. This may be another reason for the persistance of the acne and failure of treating it with antibiotics.[4] In appropriate situations, Candida sp. may also show itself as an opportunistic infection. Due to the production of keratinase, Candida sp. can develop and grow in the stratum corneum of the skin unlike many other microorganisms. As some of the studies and researches indicate, there are enough and good reasons to believe that yeast sp. can intensify acne, eczema, psoriasis, and atopic dermatitis. Skin of the patients has a strong inflammatory response to yeasts and this initial inflammation can intensify the progress of acne.[5,6] To reduce the prevalence of resistant Candida species and to improve the treatment outcome, it is important to determine the susceptibility of Candida isolates to antifungals before the start of the treatment.[7] Based on the studies and researches conducted by dermatologists and mycologist, we may hypothesize that Candida yeast, in addition to Malassezia sp. can be considered as one of the factors for acne.[6,7] We also utilized current laboratory methods to diagnose the Candida sp. found among the acne patients and the drug susceptibility evaluation.

Materials and Methods

Samples

Altogether 70 swab samples were collected from the patients attending dermatology clinic as also from the suspicious acne lesions of students of high and junior-high schools in the western urban area of north of Iran (Tonekabon City). Those who were using or used topical or systemic medication within the past 4 weeks of sample collection were excluded from the study. The skin was first cleansed with 70% ethanol, and the material was taken out from skin lesions by sterile swab and placed into transport medium.

Isolation and identification of the species

Two test tubes, containing brain-heart infusion medium (Sigma-Aldrich), were used as the transitional media. After the sampling swab was transferred to the laboratory, immediately it was cultivated in a linear manner on the Sabouraud Dextrose Agar medium (Merck, Germany) which contained chloramphenicol (Sigma-Aldrich), then, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 48 h to form yeast colonies. Suspected colonies of the yeast were tested to determine the type of yeast. Molecular identification methods were used to determine the species Candida.[8,9,10]

Molecular identification

DNA extraction

This procedure included the lysis of yeast colonies or cells from liquid culture in lithium acetate-sodium dodecyl sulfate solution and succeeding precipitation of DNA with ethanol. To extract the DNA of lysis buffer, sodium acetate buffer, K Proteinase, isopropyl alcohol, 70% ethanol, and 0.5 mm glass beads were utilized. The extracted DNA underwent electrophoresis in 1% gel to make sure about its quality. In quantitative terms, the resulting materials were checked in 260 nm wavelengths through spectrophotometry method.[10,11]

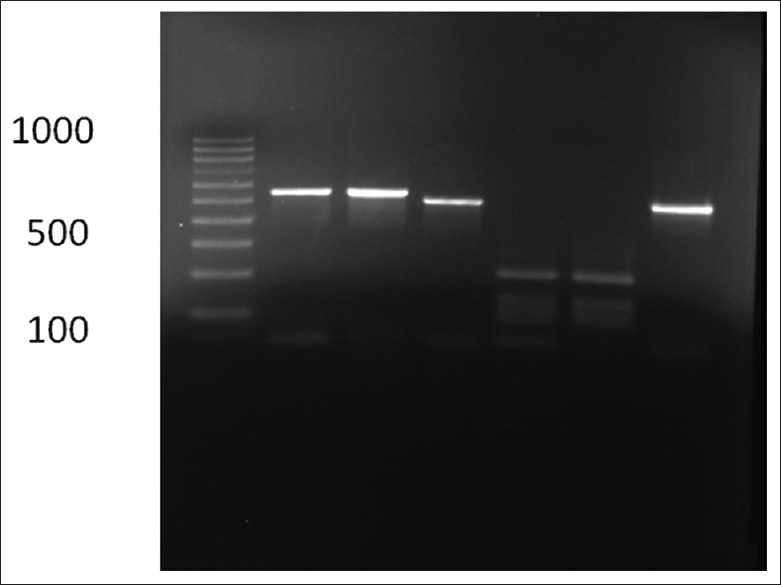

Polymerase chain reaction method

In this method, rapid identification of fungi by sequencing the ITS1 and ITS2 regions was performed[12,13] with primer forward: ITS1 (5’ TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3') and primer reverse: ITS4 (5'-CCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3') (GenFanAvaran, Iran).[14] The final product was tested by electrophoresis on agarose gel (Power supply, model300, USA) to check its validity.[12,15] Once assured of its validity, the final product was sent to Jen Fanavaran Co. to determine its sequence. The resulting DNA sequences were analyzed using Blast 2.0 online software on NCBI/blast website.

Antifungal susceptibility testing

For this purpose, microdilution broth test in accordance to the global standard (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute - M27A3) was utilized. Dilution of various concentrations of the selected antifungal drugs (Sigma-Aldrich): ketoconazole (KTZ), fluconazole (FCZ), itraconazole (ITZ) was carried out in RPMI164 medium along with L-glutamine (Sigma Chemical Co.) through binary concentrations in a 96 well microplate with an ultimate concentration of 0.016–16 μg/mL for KTZ, ITZ, and 0.063–64 μg/ml for FCZ. Reading the results of minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was accomplished using mirror. To ensure reading the results, spectrophotometer (Sigma, Germany) with the wavelength of 620 nm was used.[12,13] Using SPSS software (Version 19), the data were analyzed and P<0.05 was considered as the level of significance.

Results

Of the 70 patients recruited for the present study 49 (70%) were female and the rest 21 (30%) were male. The majority (33, 47.14%) belonged to the age group of 15 to 20 years. There were 18 persons in the 20 to 25 years, 12 in 25 to 30 years, and 6 in 10 to 15 years age group and only 2 were above 30 year. Fifty-four of the participants were from urban area and the rest 16 were from rural background. A positive family history of acne was found in 46.4% of cases and 53.6% had no family history. In 37, the duration of the disease was less than 1 year; 20 had it for 1 to 5 years; for 11 it was 5 to 10 years and the rest 2 were suffering from the problem for a pretty long time. Forty one of the group had history of previous treatment while the rest 29 were naive patients.

Based on the culture and other diagnostic tests for 70 samples, 12 colonies suspicious of Candida sp. were found. Using the sequencing method, finally 11 cases of Candida (15.71%) were identified. The following species were seen: Eight (72.73%) Candida parapsilosis, one (9.9%) Candida krusei, one (9.9%) Candida lusitaniae, one (9.9%) Candida kefyr. One colony suspicious of Candida was found to be Trichosporon asahii [Figure 1]. As shown in Figure 1, all the samples were in the 386bp band. The results of drug susceptibility testing of Candida isolates have been described in Table 1. Except for Cp1 and Cp8 isolates, which had relative resistance, other species of the Candida and other isolates of C. parapsilosis were sensitive to the tested drugs.

Figure 1.

DNA amplifications of the ITS gene from Candidia sp. (350–880 bp) by polymerase chain reaction with universal primer on gel electrophoresis

Table 1.

In vitro susceptibility of isolates of Candida recovered from acne, to antifungal agents

Discussion

The basic cause of acne is the disorder in the composition and the secretion of sebaceous glands and also disorders in the process and intensity of keratinization.[1,16] Achieving control can be a giant step in answering the epidemiologic questions, treating the disease and removing the hygiene problems associated with this disease. Although some Candida species are the etiologic agents for a broad range of cutaneous damages referred to as cutaneous Candidiasis, few studies have been conducted on their role in acne.[4]

In the present study on acne, out of the 70 individuals enrolled, 70% were female and 30% were male. In the study conducted by Etezadi et al., of 125 patients, 56% of patients were female and 44% male and the patients ranged from 12 to 40 years old.17 In our study the age range was from 10 to 35 years.

Based on the culture results and other diagnostic tests of the 70 samples, 11 colonies of Candida sp. were positive. C. parapsilosis was the most common (72.73%) species isolated in our study. In the study conducted by Etezadi et al. of 45 cases of acne, Candida sp. was isolated from 11 patients that included C. parapsilosis (27.2%), C. krusei (18.2%), C. dubliniensis (18.2%), C. kefyr (18.2%) and Candida glabrata (18.2%).[17]

In the study conducted by Kalarestaghi et al. (2010) among the 123 cultures of those afflicted with acne, 23 cases were positive, among which 3 cases were Malassezia furfur, 2 cases C. glabrata, 1 case Candida albicans, and 17 other species of Candida were found.[18] In a study conducted by Nagentu et al. in France to investigate the relationship between lipase enzyme and pathogenicity of C. parapsilosis, it showed that this gene has a major role in the pathogenicity of Candida sp.[19] In another study conducted by Hu et al., Malassezia sp. was detected in the affected follicles of 80% of patients and oral antifungal drugs such as ITZ were better than other medicines in terms of their clinical and antifungal influences.[20]

Based on these researches, the highest level of frequency went to C. parapsilosis. Some researches of course pointed to the greater frequency of nonalbicans species compared to C. albicans and Malassezia sp. Extracellular enzymes of C. parapsilosis contribute to digestion of the host cell wall as a source of food and cause further invasion.[21]

Thus, considering the high frequency of Malassezia sp. in skin as microflora in comparison to Candida, a quick look at the results of the above-mentioned studies can get us to the conclusion that Candida, a normal flora of the skin, can also be considered as a factor in acne.[22] With the exception of Cp1 and Cp8 isolates which were relatively resistant, other species of the Candida and other isolates of C. parapsilosis were sensitive to KTZ, FCZ, and ITZ.

In the research conducted by Kalarestaghi et al. on Malassezia isolates, the following facts were reported: MIC KTZ 2–0.02 μg/mL, MIC CTZ 4–16 μg/mL, and MIC MCZ 2–16 μg/mL.[18] In a study conducted by Grossman et al., resistance to FCZ in 122 isolated cases of C. parapsilosis was reported to be 7.5% in the hospitals of the US.[23]

Arevalo et al. studied the sensitivity pattern of 625 Candida species recovered from hospital inpatients and found Candida albicans in 388 specimens, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata in 84 each and C. parapsilosis in 69 samples. They also showed that among the C. albicans isolates 10% were resistance to ITZ and 8.8% to FCZ, and 1.8% to KTZ. Among C. tropicalis, 39.5% were resistant to ITZ, 34.5% to FCZ and 2.4% to KTZ. Of the C. glabrata isolates, 19.1% were resistant to FCZ and 13.1% to ITZ; 4.4% of C. parapsilosis were resistant to FCZ and 1.5% to ITZ. They concluded that C. tropicalis was the most resistant and C. parapsilosis the most sensitive among the isolates.[24]

Considering the results of this study and changes in the microbial state of the skin, lipase gene might be one of the virulence factors of Candida and Malassezia yeasts in causing the disease with the hope of finding appropriate methods to treat acne.[25]

Conclusions

Various studies have shown that in most cases bacterial agents are involved in causing acne, whereas, according to the results of this study, it can be suggested that the yeast Candida may be introduced as an agent in the etiology of this disease. Candida species isolates can also be resistant to common antifungal drugs and this could be one of several causes why sequential treatment of this disease is defeated.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was financially supported by Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tonekabon, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by a research project (a grant) approved (No. 26169) from Tonekabon Branch, Islamic Azad University,(Tonekabon, Iran) which we gratefully acknowledge.

References

- 1.Kurokawa I, Danby FW, Ju Q, Wang X, Xiang LF, Xia L, et al. New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:821–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanghetti EA. The role of inflammation in the pathology of acne. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2013;6:27–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burkhart CG, Burkhart CN, Lehmann PF. Acne: A review of immunologic and microbiologic factors. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:328–31. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.75.884.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alver O, Gürcan S, Özkaya G, Ener B. The effects of virulence factors on invasion in various species of Candida. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2013;7:719–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Asbeck EC, Clemons KV, Stevens DA. Candida parapsilosis: A review of its epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical aspects, typing and antimicrobial susceptibility. Crit Rev Microbiol. 2009;35:283–309. doi: 10.3109/10408410903213393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang SH, Kim HU. The isolation of Malassezia yeasts in the comedones of Acne vulgaris. Korean J Med Mycol. 1999;4:33–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jafari-Nodoushan AA, Kazemi A, Mirzaii F, Dehghani M. Fluconazole susceptibility profile of Candida isolates recovered from patients specimens admitted to Yazd Central Laboratory. Iran J Pharm Res. 2008;7:69–75. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song YC, Hahn HJ, Kim JY, Ko JH, Lee YW, Choe YB, et al. Epidemiologic study of Malassezia yeasts in acne patients by analysis of 26S rDNA PCR-RFLP. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:321–8. doi: 10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang SJ, Lim SH, Ko JH, Oh BH, Kim SM, Song YC, et al. The investigation on the distribution of Malassezia yeasts on the normal Korean skin by 26S rDNA PCR-RFLP. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:18–26. doi: 10.5021/ad.2009.21.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ataides FS, Costa CR, Souza LK, Fernandes Od, Jesuino RS, Silva Mdo R, et al. Molecular identification and antifungal susceptibility profiles of Candida parapsilosis complex species isolated from culture collection of clinical samples. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:454–9. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0120-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lõoke M, Kristjuhan K, Kristjuhan A. Extraction of genomic DNA from yeasts for PCR-based applications. Biotechniques. 2011;50:325–8. doi: 10.2144/000113672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YC, Lin YH, Chen KW, Lii J, Teng HJ, Li SY, et al. Molecular epidemiology and antifungal susceptibility of Candida parapsilosis sensu stricto, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis in Taiwan. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;68:284–92. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.3rd ed. Vol. 28. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. CLSI, Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts. Approved Standard M27-A3. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujita SI, Senda Y, Nakaguchi S, Hashimoto T. Multiplex PCR using internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 regions for rapid detection and identification of yeast strains. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:3617–22. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.10.3617-3622.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pryce TM, Palladino S, Kay ID, Coombs GW. Rapid identification of Fungi by sequencing the ITS1 and ITS2 regions using an automated capillary electrophoresis system. Med Mycol. 2003;41:369–81. doi: 10.1080/13693780310001600435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zouboulis CC, Eady A, Philpott M, Goldsmith LA, Orfanos C, Cunliffe WC, et al. What is the pathogenesis of acne? Exp Dermatol. 2005;14:143–52. doi: 10.1111/j.0906-6705.2005.0285a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etezadi T, Hajheydari Z, Kalarestaghi AR, Nasrollahi Omran A, Shokohi T, Hedayati MT. The prevalence of candida in skin and acne lesions of patients Candida parapsilosis and Candida krusei were the most frequent isolated. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2012;30:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kalarestaghi AR, Hajheydari Z, Hedayati MT, Shokohi T. Hospital from sari and susceptibility of isolated species to ketoconazole’ miconazole and clotrimazole. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci. 2011;24:10–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen LN, Trofa D, Nosanchuk JD. Fatty acid synthase impacts the pathobiology of candida parapsilosis in vitro and during Mammalian infection. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu G, Wei YP, Feng J. Malassezia infection: Is there any chance or necessity in refractory acne? Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:628–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gácser A, Trofa D, Schäfer W, Nosanchuk JD. Targeted gene deletion in Candida parapsilosis demonstrates the role of secreted lipase in virulence. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3049–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI32294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prohic A, Jovovic Sadikovic T, Krupalija-Fazlic M, Kuskunovic-Vlahovljak S. Malassezia species in healthy skin and in dermatological conditions. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:494–504. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grossman NT, Pham CD, Cleveland AA, Lockhart SR. Molecular mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in candida parapsilosis isolates from a US Surveillance system. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59:1030–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04613-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arévalo MP, Arias A, Andreu A, Rodríguez C, Sierra A. Fluconazole, itraconazole and ketoconazole in vitro activity against candida spp. J Chemother. 1994;6:226–9. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.1994.11741156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunel L, Neugnot V, Landucci L, Boze H, Moulin G, Bigey F, et al. High-level expression of Candida parapsilosis lipase/acyltransferase in Pichia pastoris. J Biotechnol. 2004;111:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]