Short abstract

Objectives

Two-stage open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and limited internal fixation combined with external fixation (LIFEF) are two widely used methods to treat Pilon injury. However, which method is superior to the other remains controversial. This meta-analysis was performed to quantitatively compare two-stage ORIF and LIFEF and clarify which method is better with respect to postoperative complications in the treatment of tibial Pilon fractures.

Methods

We conducted a meta-analysis to quantitatively compare the postoperative complications between two-stage ORIF and LIFEF. Eight studies involving 360 fractures in 359 patients were included in the meta-analysis.

Results

The two-stage ORIF group had a significantly lower risk of superficial infection, nonunion, and bone healing problems than the LIFEF group. However, no significant differences in deep infection, delayed union, malunion, arthritis symptoms, or chronic osteomyelitis were found between the two groups.

Conclusion

Two-stage ORIF was associated with a lower risk of postoperative complications with respect to superficial infection, nonunion, and bone healing problems than LIFEF for tibial Pilon fractures.

Level of evidence

2.

Keywords: Pilon fracture, surgical complication, ankle, open reduction and internal fixation, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation, meta-analysis

Introduction

Tibial Pilon fractures are the most severe ankle joint injuries. Pilon injuries are relatively rare and constitute only 5% to 10% of all tibial fractures.1 Most Pilon fractures are caused by high-energy trauma and are usually associated with articular communication and severe soft tissue injury, making management extremely difficult for foot and ankle surgeons.

Different methods have been introduced to treat tibial Pilon fractures, but the optimal treatment remains a matter of debate. In 1979, Ruedi and Allgower2 first reported satisfactory results with primary open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). However, many authors have noted significant complications when ORIF was applied to severe Pilon fractures, including an infection rate as high as 55%. These complications arose from the internal fixation, leading many orthopedic surgeons to choose external fixation as an alternative.3,4 Although external fixation decreased wound necrosis and skin sloughing, high rates of pin site infection and malalignment with subsequent nonunion occurred. Therefore, orthopedic surgeons made great efforts to establish methods that provided good results and decreased postoperative complications. With the accumulation of surgical experience and the development of surgical techniques, two-stage ORIF and limited internal fixation combined with external fixation (LIFEF) were established, and these two methods are now widely advocated for the treatment of tibial Pilon fractures.5

Two-stage ORIF involves closed reduction and external fixation followed by conversion to ORIF after the condition of the surrounding soft tissues has improved. This technique focuses on the soft tissue condition and potentially decreases the incidence of soft tissue complications.6 Thus, this method is widely considered the standard of care for high-energy Pilon fractures.

However, other surgeons have recommended LIFEF for these severe fractures as an alternative to ORIF in an attempt to reduce the risk of postoperative complications.7 Although LIFEF may decrease surgical soft tissue injury, no systematic review has showed that LIFEF is superior to two-stage ORIF with respect to postoperative complications. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to quantitatively compare the postoperative complications between two-stage ORIF and LIFEF.

Materials and methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guideline was used to conduct this meta-analysis.8 Because this was a meta-analysis, ethics approval was not required.

Search strategy

The search terms were “two-stage open reduction and internal fixation,” “delayed open reduction and internal fixation,” “two-stage ORIF,” “delayed ORIF,” “limited internal fixation,” “LIFEF,” “external fixation,” “external fixator,” “tibial plafond fracture,” and “Pilon.” We searched PubMed, OVID, ISI Web of Knowledge, the Cochrane Library, and the Chinese Biomedical Database for eligible studies to July 2017. There were no restrictions on date, language, or publication status. Two of the authors independently performed the search and selected relevant studies. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author.

Inclusion criteria for eligible studies

Randomized, prospective, and retrospective studies.

Studies comparing two-stage ORIF and LIFEF for tibial plafond fractures.

Patients aged ≥18 years.

A follow-up time of ≥9 months.

Data extraction and study quality assessment

All eligible studies were read, and the relevant data were extracted by two independent authors. The information included the authors’ names, year, country, type of study, and number of patients allocated to each group. The primary outcomes were superficial infection, deep infection, nonunion, delayed union or malunion, arthritis symptoms, and chronic osteomyelitis. The Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine rating scale was used to assess the methodological quality of the eligible studies. Differences were settled by discussion until an agreement was reached.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager 5.3 software (Cochrane Information and Knowledge Management Department: available at http://community.cochrane.org). The factors analyzed were superficial infection, deep infection, nonunion, delayed union or malunion, arthritis symptoms, and chronic osteomyelitis. We analyzed the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) for dichotomous data. The I2 value was used to assess statistical heterogeneity among studies. If heterogeneity was significant (I2 > 50%), the meta-analysis was performed with a random-effects model, and if the heterogeneity was not significant (I2 ≤ 50%), a fixed-effects model was used. We performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding the low-quality studies.

Results

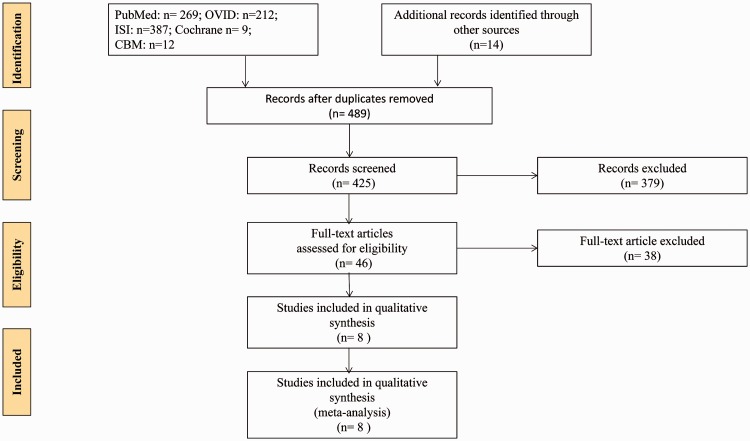

In total, eight studies compared two-stage ORIF and LIFEF for tibial Pilon fractures and were published from 2001 to 2016. Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the search results. The eight studies that met the inclusion criteria comprised one randomized controlled trial, one prospective cohort study, and six retrospective nonrandomized studies (Table 1).9–16

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature screening.ISI, ISI Web of Knowledge; Cochrane, Cochrane Library; CBM, Chinese Biomedical Database.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Investigators | Design | Group | Age (y) | Patients (n) | Male (n) | Female (n) | Fractures (n) | Fracture class | Country | Follow-up (mo) | Level of evidence | Result favored |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al.,16 2010 | RCT | Two-stage ORIF | 40.1 ± 10.7 | 27 | 25 | 2 | 27 | B3 (n = 3)C1 (n = 9)C2 (n = 10)C3 (n = 5)* | China | 24 | I | ORIF |

| LIFEF | 37.2 ± 10.9 | 29 | 26 | 3 | 29 | B3 (n = 2)C1 (n = 7)C2 (n = 13)C3 (n = 7)* | ||||||

| Davidovitch et al.,12 2011 | Retro. | Two-stage ORIF | 39 | 26 | 17 | 9 | 26 | C1 (n = 3)C2 (n = 4)C3 (n = 19)* | US | 12 | III | NS |

| LIFEF | 43 | 20 | 12 | 8 | 21 | C1 (n = 2)C2 (n = 6)C3 (n = 13)* | ||||||

| Richards et al.,15 2012 | Cohort | Two-stage ORIF | 40.66 ± 13.3 | 18 | NR | NR | 18 | C1 (n = 1)C2 (n = 1)C3 (n = 16)* | US | 12 | II | ORIF |

| LIFEF | 46.96 ± 13.1 | 27 | NR | NR | 27 | C1 (n = 1)C2 (n = 5)C3 (n = 21)* | ||||||

| Blauth et al.,10 2001 | Retro. | Two-stage ORIF | NR | 15 | NR | NR | 15 | NR | Australia | 48 | III | NS |

| LIFEF | NR | 8 | NR | NR | 8 | NR | ||||||

| Deivaraju et al.,13 2015 | Retro. | Two-stage ORIF | NR | 33 | NR | NR | 33 | A (n = 4)B (n = 6)C (n = 23)* | US | 9 | III | NS |

| LIFEF | NR | 32 | NR | NR | 32 | A (n = 1)B (n = 5)C (n = 26)* | ||||||

| Bacon et al.,9 2007 | Retro. | Two-stage ORIF | 39.4 ± 11.2 | 25 | 20 | 5 | 25 | C1 (n = 3)C2 (n = 7)C3 (n = 15)* | US | 12 | III | NS |

| LIFEF | 32.3 ± 10.2 | 13 | 11 | 2 | 13 | C1 (n = 1)C2 (n = 3)C3 (n = 9)* | ||||||

| Koulouvaris et al.,14 2007 | Retro. | Two-stage ORIF | 45.6 | 13 | NR | NR | 13 | B2 (n = 8)B3 (n = 0)C1 (n = 0)C2 (n = 5)C3 (n = 0) | US | 12 | III | ORIF |

| LIFEF | 46 | 42 | NR | NR | 42 | B2 (n = 7)B3 (n = 4)C1 (n = 14)C2 (n = 11)C3 (n = 6) | ||||||

| Cisneros et al.,11 2016 | Retro. | Tw-stage ORIF | NR | 18 | NR | NR | 18 | NR | India | 24 | III | ORIF |

| LIFEF | NR | 13 | NR | NR | 13 | NR |

ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; LIFEF, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation; RCT, randomized controlled trial; Retro., retrospective; NR, not reported; NS, not significant.

*Orthopaedic Trauma Association classification [Orthopaedic Trauma Association Committee for Coding and Classification. Fracture and dislocation compendium. J Orthop Trauma 1996; 10(Suppl 1): 1–154].

The eight eligible studies involved 360 fractures in 359 patients. Of these 360 fractures, 175 were treated with two-stage ORIF and 184 were treated with LIFEF.

The Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine quality rating scale revealed a quality level of I in one study, II in one study, and III in six studies.

Postoperative complications

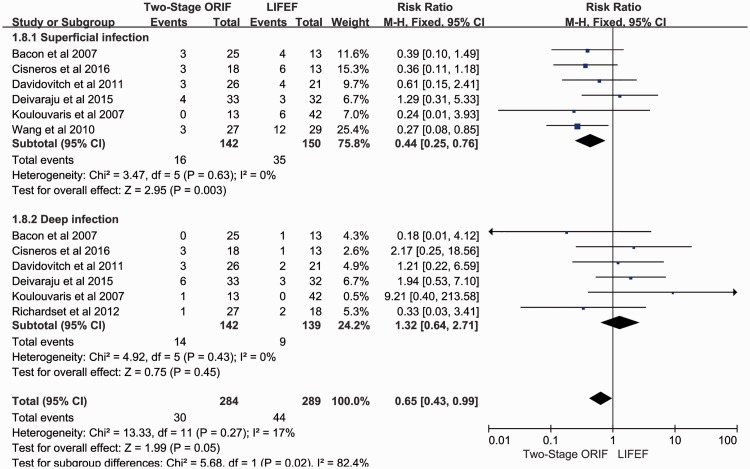

Superficial and deep infection

Superficial infection was defined as abnormal changes in skin color, skin warmth, and drainage over 72 hours, possibly with the addition of pus or increased microbial growth on cultures; however, it could be cured by local cleansing and oral antibiotics. Although all studies reported the results of infection, one study did not state the details of superficial and deep infections and was therefore excluded. The rate of superficial infection was 16 of 142 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 35 of 150 fractures in the LIFEF group. The rate of deep infection was 14 of 142 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 9 of 139 fractures in the LIFEF group. The meta-analysis showed a higher risk of superficial infection in the LIFEF group (RR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.25–0.76, chi2 = 3.47, p = 0.003) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

Deep infection was defined as severe changes of wounds that required the patient to return to the operating room for debridement and intravenous antibiotics. There were no significant differences in deep infection between the two groups (RR = 1.32, 95% CI = 0.64–2.71, chi2 = 4.92) and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of superficial and deep infection. ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; LIFEF, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel statistic; CI, confidence interval.

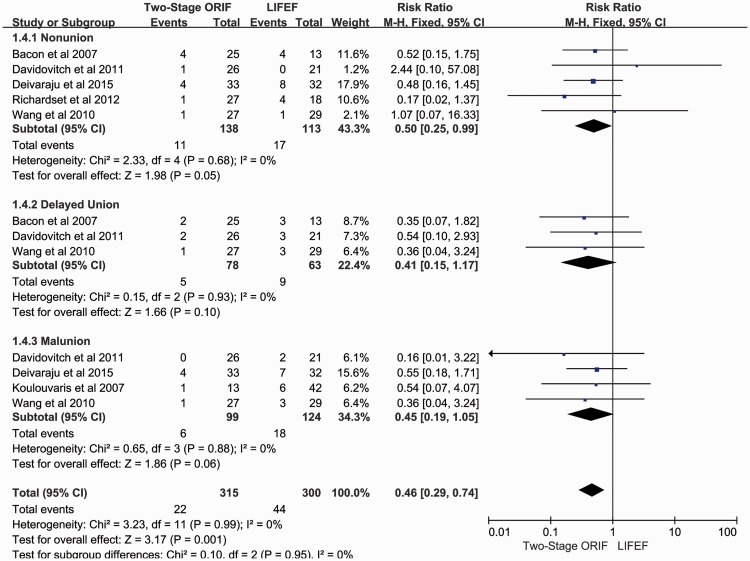

Subgroup analysis of bone healing complications

A subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate bone healing complications (nonunion, delayed union, and malunion).

Nonunion was defined as a fracture that had not healed (by radiographic criteria of healing) within 6 months of injury.15 A total of 5 studies involving 251 fractures reported the results of nonunion. The rate of nonunion was 11 of 138 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 17 of 113 fractures in the LIFEF group. The meta-analysis showed a higher risk of nonunion in the LIFEF group (RR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.25–0.99, chi2 = 2.33, p = 0.05) with no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Subgroup analysis of bone healing problems. ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; LIFEF, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel statistic; CI, confidence interval.

Delayed union was defined as a fracture that showed a cessation of the healing process (by radiographic healing criteria) at 3 months postinjury.15 A total of 3 studies involving 141 fractures reported the results of delayed union. The rate of delayed union was 5 of 78 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 9 of 63 fractures in the LIFEF group. The meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.15–1.17) and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 3). Malunion was defined as angulation of 5º in the coronal plane, angulation of 10º in the sagittal plane, or 2 mm of articular stepoff as seen on postoperative radiographs.15 Four studies involving 223 fractures reported the results of malunion. The rate of malunion was 6 of 99 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 18 of 124 fractures in the LIFEF group. No significant difference was found between the two groups (RR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.19–1.05, chi2 = 0.65), and no significant heterogeneity was present (I2 = 0%) (Figure 3).

The overall effect showed that the rate of bone healing complications was 22 of 315 fractures and 44 of 300 fractures in the two-stage ORIF and LIFEF groups, respectively. The meta-analysis of the overall effect demonstrated that the two-stage ORIF group had a lower rate of bone healing problems (RR = 0.46, 95% CI = 0.29–0.74, chi2 = 3.23, p = 0.001). The heterogeneity was not significant among the studies.

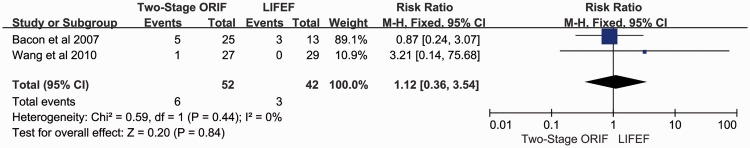

Chronic osteomyelitis

The diagnosis of chronic osteomyelitis was based on the presence of chronic sinus drainage, fistulas, ulcers, or radiographic evidence.16 Two studies reported the results of chronic osteomyelitis. The total rate was 6 of 52 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 3 of 42 fractures in the LIFEF group. The meta-analysis showed no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 1.12, 95% CI = 0.36–3.54) and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of chronic osteomyelitis. ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; LIFEF, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel statistic; CI, confidence interval.

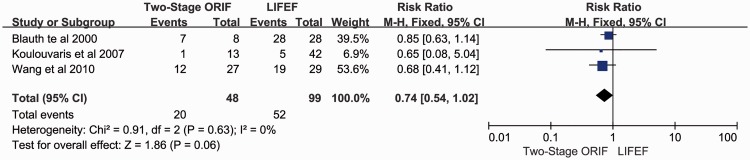

Arthritis symptoms

Three studies reported arthritis symptoms. The rate of arthritis symptoms was 20 of 48 fractures in the two-stage ORIF group and 52 of 99 fractures in the LIFEF group. There was no significant difference between the two groups (RR = 0.74, 95% CI = 0.54–1.02, chi2 = 0.91) and no significant heterogeneity (I2 = 0%) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of arthritis symptoms.ORIF, open reduction and internal fixation; LIFEF, limited internal fixation combined with external fixation; M-H, Mantel–Haenszel statistic; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

Pilon fractures occur at the distal end of the tibia and are often associated with serious damage to the articular surface. Such fractures generally have a poor prognosis. Their causes include road traffic accidents, falling from a height, and similar occurrences.1 The number of Pilon fractures is rising as the incidence of high-energy accidents increases. During injury, the high axial load and torsion not only contribute to tibial plafond destruction but also result in severe soft tissue trauma. Thus, how to repair Pilon fractures and protect the soft tissue remains challenging.17

During the past few decades, various treatment strategies for these fractures have been developed.18–20 In 1979, Ruedi and Allgower2 first reported good and excellent results of primary ORIF in 84 patients, and ORIF became the gold standard for treatment of Pilon fracture at that time. However, other authors have had difficulties reproducing the same outcomes, especially when ORIF was attempted for high-energy trauma; high postoperative complication rates and a poor prognosis were reported. Thus, when managing high-energy Pilon fractures, emphasis must be placed on good treatment of the articular surface while ensuring suitable management of the soft tissue.

With the accumulation of surgical experience and development of surgical techniques, increasingly more authors are choosing two-stage ORIF and LIFEF to treat high-energy Pilon fractures with satisfactory results.21,22 The first stage of the two-stage ORIF protocol is to perform temporizing fixation by application of an ankle-spanning external fixator or calcaneal traction. The second step is to convert the external fixation to internal fixation after 7 to 14 days when the soft tissue edema and inflammation have settled down. Many surgeons have employed this protocol and reported a vastly decreased incidence of complications.16,23 As an alternative to staged ORIF, LIFEF was evaluated with respect to its ability to achieve articular surface realignment with limited injury to the soft tissue. Multiple studies have shown that comparable results could be achieved by LIFEF while minimizing the infection and skin sloughing rates.7

Prospective randomized studies are difficult to design because of ethical considerations. Thus, the meta-analysis is an important tool with which to summarize the most useful evidence and help orthopedic surgeons to weigh the benefits and disadvantages of different interventions.24 This is the first meta-analysis to quantitatively compare the clinical efficiency of two-stage ORIF versus LIFEF. It included one randomized controlled trial, one prospective cohort study, and six retrospective nonrandomized studies. These 8 studies included 360 Pilon fractures, 175 of which were treated by two-stage ORIF and 185 of which were treated by LIFEF.

Infection is a common problem in the treatment of Pilon fractures. A subgroup analysis of superficial and deep infection was performed. The meta-analysis showed that the rate of superficial infection was higher in the LIFEF group. However, the rate of deep infection was similar between the two groups. The heterogeneity was not significant among the studies. Among the individual studies included in the meta-analysis, Wang et al.16 found that the superficial infection rate was significantly higher in the LIFEF than two-stage ORIF group. The other studies showed that the rates of superficial and deep infection were not significantly different between the two groups. Compared with the LIFEF technique, the direct ORIF procedure requires wound exposition and results in soft tissue damage, which may increase the infection rate. However, the first step of two-stage ORIF is to perform temporizing fixation by application of a spanning external fixator or calcaneal traction. This avoids excessive disturbance of the compromised soft tissues during the high-risk period and creates opportunities for the soft tissue to recover. When the soft tissue edema and inflammation have substantially decreased after 7 to 14 days, the risk of infection caused by wound exposure in the ORIF process is reduced. LIFEF may induce less soft tissue damage and involve less surgical dissection, but pin tract infection is a frequent complication in this procedure. Thus, the superficial infection rate was higher in the LIFEF group. Additionally, deep infection has been shown to be equally likely in both treatment groups,24 and the present meta-analysis showed similar results.

Five studies reported the complication of nonunion. The mean nonunion rate was 8% in the two-stage ORIF group and 15% in the LIFEF group. Although no individual study showed a significant difference between the two groups, the meta-analysis showed that the rate of nonunion was higher in the LIFEF group.

Delayed union and malunion are also common complications during the treatment of Pilon fractures. The ORIF technique might increase the risk of delayed union because of extensive dissection and possible damage to the blood supply. However, the meta-analysis did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups. This result was also confirmed by the individual studies. Two-stage ORIF has many advantages over LIFEF, such as the ability to remove the soft tissues including the periosteum, muscles, and ruptured ligaments embedded in the fracture fragment. Additionally, ORIF allows for visualization of the joint surface and achieves anatomic reconstruction. The rate of malunion may also be lower with two-stage ORIF than with LIFEF. Although though the mean rate of malunion in the two-stage ORIF group (6.06%) was greater than that in the LIFEF group (14.52%), the present meta-analysis did not show a statistically significant difference between the two groups.

In recent years, increasingly more studies have reported promising results with the two-stage procedure.25,26 Temporary transarticular external fixation and reconstruction of the length of the fibula by internal fixation allow minimal compromise of the soft tissues. Secondary reconstruction of the articular surface can be performed by minimally invasive osteosynthesis. This meta-analysis proved these outcomes and showed that the rate of bone healing problems was significantly lower in the two-stage ORIF group.

This meta-analysis showed no significant differences in the rates of arthritis symptoms and chronic osteomyelitis between the two groups. Blauth et al.,10 Koulouvaris et al.,14 and Wang et al.16 reported that the rate of arthritis symptoms was similar between the two groups.

This study has some limitations. First, this meta-analysis included one randomized controlled trial, one prospective cohort study, and six retrospective studies. The retrospective studies may have had bias, lowering the reliability of the conclusions. Second, the Ilizarov fixator used in one report9 differs from external fixation using Schanz screws both biomechanically and in terms of the complication rate. Statistical conclusions may be difficult to reach because of the lack of information. Third, the sample sizes were relatively small in most of the studies. More high-quality studies comparing two-stage ORIF and LIFEF are needed in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present evidence has demonstrated that two-stage ORIF is associated with a lower risk of postoperative complications with respect to superficial infection, nonunion, and bone healing problems than LIFEF for tibial Pilon fractures. However, these two methods are similar with respect to the incidence of deep infection, arthritis symptoms, and chronic osteomyelitis.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Mauffrey C, Vasario G, Battiston B, et al. Tibial pilon fractures: a review of incidence, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Acta orthopaedica Belgica 2011; 77: 432–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruedi TP, Allgower M. The operative treatment of intra-articular fractures of the lower end of the tibia. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1979: 105–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egol KA, Tejwani NC, Capla EL, et al. Staged management of high-energy proximal tibia fractures (OTA types 41): the results of a prospective, standardized protocol. J Orthop Trauma 2005; 19: 448–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tejwani NC and, Achan P. Staged management of high-energy proximal tibia fractures. Bulletin 2004; 62: 62–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarkin IS, Clare MP, Marcantonio A, et al. An update on the management of high-energy pilon fractures. Injury 2008; 39: 142–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, et al. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2004; 18(8 Suppl): S32–S38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wyrsch B, McFerran MA, McAndrew M, et al. Operative treatment of fractures of the tibial plafond. A randomized, prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78: 1646–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009; 62: 1006–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bacon S, Smith WR, Morgan SJ, et al. A retrospective analysis of comminuted intra-articular fractures of the tibial plafond: Open reduction and internal fixation versus external Ilizarov fixation. Injury 2008; 39: 196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blauth M, Bastian L, Krettek C, et al. Surgical options for the treatment of severe tibial pilon fractures: a study of three techniques. J Orthop Trauma 2001; 15: 153–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cisneros LN, Gomez M, Alvarez C, et al. Comparison of outcome of tibial plafond fractures managed by hybrid external fixation versus two-stage management with final plate fixation. Indian J Orthop 2016; 50: 123–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davidovitch RI, Elkhechen RJ, Romo S, et al. Open reduction with internal fixation versus limited internal fixation and external fixation for high grade pilon fractures (OTA type 43C). Foot Ankle Int 2011; 32: 955–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deivaraju C, Vlasak R, Sadasivan K. Staged treatment of pilon fractures. J Orthop 2015; 12(Suppl 1): S1–S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koulouvaris P, Stafylas K, Mitsionis G, et al. Long-term results of various therapy concepts in severe pilon fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2007; 127: 313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Richards JE, Magill M, Tressler MA, et al. External fixation versus ORIF for distal intra-articular tibia fractures. Orthopedics 2012; 35: 862–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang C, Li Y, Huang L, et al. Comparison of two-staged ORIF and limited internal fixation with external fixator for closed tibial plafond fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010; 130: 1289–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liporace FA, Yoon RS. Decisions and staging leading to definitive open management of pilon fractures: where have we come from and where are we now? J Orthop Trauma 2012; 26: 488–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abou Elatta MM, Assal F, Basheer HM, et al. The use of dynamic external fixation in the treatment of dorsal fracture subluxations and pilon fractures of finger proximal interphalangeal joints. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2017; 42: 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang SB, Zhang YB, Wang SH, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of limited internal fixation combined with external fixation for Pilon fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin J Traumatol 2017; 20: 94–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penny P, Swords M, Heisler J, et al. Ability of modern distal tibia plates to stabilize comminuted pilon fracture fragments: Is dual plate fixation necessary? Injury 2016; 47: 1761–1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busel GA, Watson JT, Israel H. Evaluation of Fibular Fracture Type vs Location of Tibial Fixation of Pilon Fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2017; 38: 650–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong D, Ji F, Zhang H, et al. Two-stage procedure protocol for minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis technique in the treatment of the complex pilon fracture. Int Orthop 2012; 36: 833–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2009; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill CE. Does external fixation result in superior ankle function than open reduction internal fixation in the management of adult distal tibial plafond fractures? Foot Ankle Surg 2016; 22: 146–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ketz J, Sanders R. Staged posterior tibial plating for the treatment of Orthopaedic Trauma Association 43C2 and 43C3 tibial pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2012; 26: 341–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, et al. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2004; 18: 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]