Abstract

Convective oxygen transport parameters were determined in arteriolar (n = 5) and venular (n 5) capillary networks in the hamster cheek pouch retractor muscle. Simultaneously determined values of red blood cell velocity, lineal density, red blood cell frequency, hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SO2), oxygen flow (QO2), longitudinal SO2 gradient, and diameter were obtained in a total of 73 capillaries, 39 at the arteriolar ends of the network (arteriolar capillaries) and 34 at the venular ends (venular capillaries). We found that the hemodynamic variables were not different at the two ends. However, not unexpectedly, SO2 and QO2 were significantly higher at the upstream end of arteriolar capillaries (60.8 ± 9.8 (SD)% and 0.150 ± 0.081 pl/sec, respectively) compared with the downstream end of venular capillaries (39.9 ± 13.6% and 0.108 ± 0.095 pl/sec, respectively). Heterogeneities in red blood cell velocity, lineal density, SO2, and QO2, assessed by their coefficients of variation, were significantly greater in venular capillaries. To evaluate the impact of these heterogeneities on oxygen exchange, we incorporated these unique experimental data into a mathematical model of oxygen transport which accounts for variability in red blood cell frequency, lineal density, inlet SO2, capillary diameter, and, to some degree, capillary flow path lengths. An unexpected result of the simulation is that only the incorporation of variability in capillary flow path lengths had any marked effect on the heterogeneity in end-capillary SO2 in resting muscle due to extensive diffusional shunting of oxygen among adjacent capillaries. We subsequently evaluated, through model simulations, the effect of these heterogeneities under conditions of increased flow and high oxygen consumption. Under these conditions, the model predicts that heterogeneities in the hemodynamic parameters will have a marked effect on oxygen transport in this muscle. © 1988 Academic Press, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

The transport of oxygen from the blood perfusing a muscle to the mitochondria is a complex process consisting of diffusive and convective components working in concert to provide adequate amounts of oxygen to meet the metabolic needs of the tissue. It is usually presumed, on the basis of the original work of Krogh (1929), that the adequacy of tissue oxygenation is markedly influenced by the distribution of red blood cells within the capillary network, with oxygen supply enhanced by homogeneous perfusion. Such homogeneous perfusion implies that each capillary provides the same amount of oxygen to the tissue so that the distribution of oxygen within the tissue is uniform thereby eliminating the possibility of diffusional interactions among capillaries.

Recent investigations (Tyml and Groom, 1980; Tyml et al., 1981; Damon and Duling, 1984; Sarelius, 1986) have indicated that perfusion of the capillary network of striated muscle is neither spatially nor temporally homogeneous, with wide variations reported in the velocity of red blood cells (v), the number of red blood cells per unit length of capillary (lineal density, N) and the number of red blood cells per unit time passing through the capillaries (red blood cell frequency, f). The impact of these hemodynamic heterogeneities on oxygen supply to striated muscle has been the subject of much speculation (Damon and Duling, 1984; Groom et al., 1986; Sarelius, 1986). However, the lack of experimental data on the levels of oxygenation of the red blood cells in these capillaries has prevented a direct assessment of the consequences of these nonuniformities. The recent development of a technique to measure hemoglobin oxygen saturation in capillaries of striated muscle (Ellsworth et al., 1987) has enabled us to determine simultaneously both the hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters in these smallest vessels, thereby providing the information necessary to quantify the heterogeneity in all the convective oxygen transport parameters. The incorporation of these data into a previously detailed mathematical model of oxygen transport (Popel et al., 1986) provided us with the means to estimate the impact of the observed heterogeneities in both hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters on the supply of oxygen to striated muscle.

METHODS

Male golden hamsters (79 ± 5 g, 34 ± 2 days old, n = 4) were initially anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (6.5 mg/ 100 g body wt, ip). A femoral artery was cannulated with PE 10 tubing to allow continuous monitoring of arterial blood pressure. A femoral vein was likewise cannulated to permit continuous infusion of supplemental anesthetic at a rate of 0.15 mg/min. The trachea was cannulated to ensure a patent airway and the animal was allowed to breathe room air spontaneously. Deep esophageal and muscle temperatures were monitored and maintained at 37 ± 1° by separate heat exchangers within the animal platform. Data were collected only if mean arterial blood pressure exceeded 80 mm Hg.

The right cheek pouch retractor muscle was prepared as described by Sullivan and Pittman (1982). In short, the spinal end of the retractor muscle was separated from underlying back muscles and a hemoclip (Edward Weck) was used to secure two ligatures to the muscle. The spinal end of the muscle was then severed and the muscle was placed at its in situ length, ventral side up across a clear plexiglass pedestal through which the muscle was transilluminated. Several ligatures were then attached to the edges of the muscle and taped to the platform to flatten the muscle and position it at its in situ width. The preparation was covered with transparent thin plastic (Saran, Dow Corning) to minimize both desiccation of the tissue and gas exchange with the atmosphere. We did not observe any obvious deleterious effects of Saran (e.g., altered microvascular patency, platelet aggregation, or increased numbers of white cells) on the retractor muscle.

The muscle was transilluminated by a xenon lamp (75 W) with a stabilized power supply to provide constant light intensity. The preparation was illuminated with blue light (420 or 431 nm) by placing narrow bandpass (10 nm at half maximum transmission) interference filters (Optical Thin Films, N. Conway, NH) in the light beam. Observations were made using a Zeiss ACM microscope equipped with a long working distance objective (UD40/0.65). The objective was used dry to give an equivalent magnification/numerical aperture of 25.8 × /0.41. The microscope image was viewed with a closed circuit video system consisting of a SIT camera (Dage-MTI, Model 66), video monitor (Panasonic, Model WV5410), video cassette recorder (Panasonic, Model NV-9240XD), video analyzer (Colorado Video, Model 321), video field counter (Department of Biophysics, University of Western Ontario) and microcomputer (Cromemco System Two, Model CS-2H). The video analyzer superimposed a vertical cursor line on the video image that provided light intensity information (slow scan video output) for the computer analysis of red blood cell velocity, lineal density, and oxygen saturation. An amplifier circuit permitted the adjustment of the position (offset) and magnitude (gain) of the slow scan video waveform to ensure signal compatibility with the microcomputer’s analog to digital converter. A black vertical bar positioned at the left edge of the video camera provided a constant black level reference. The camera gain and high voltage were adjusted manually as was the gain on the video cassette recorder. The output of the video system was linear over the range of light intensities used. The video field counter provided the microcomputer with timing signals that indicated the beginning of each video frame and the beginning of each TV line within the frame by extracting the vertical and horizontal synchronization pulses from the composite video signal. The video field counter also provided an audio signal (cue) for the video cassette recorder which was used during playback to “enable” the video field counter (i.e., start the video field counter at a specific video field). The overall magnification of the image was 1050 × at the television monitor (0.91 μm/TV line) and uniform.

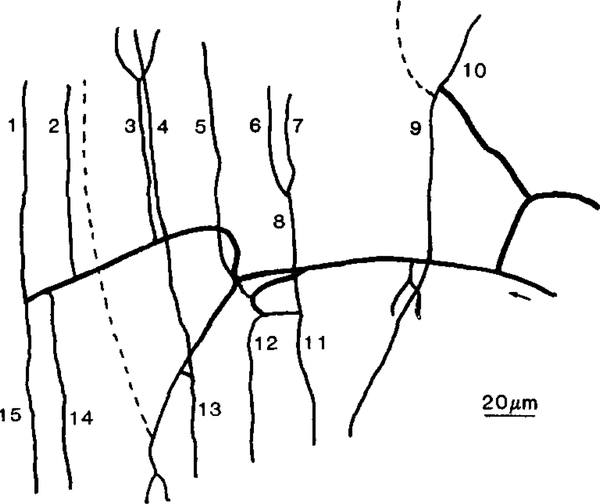

Arteriolar (n = 5) and venular (n = 5) capillary networks were selected independently and videotaped for subsequent analysis of red blood cell velocity, lineal density, red blood cell frequency, oxygen saturation, oxygen flow, longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient, and diameter. For the purposes of this study we have defined a capillary as that portion of a vessel containing single-file red blood cell flow which was visible in the same projected microscopic field as the arteriole or venule to which it attaches. We defined an arteriolar network as one in which all the capillaries originated from a single arteriole and a venular network as one in which all the capillaries drained into a single venule. Figure 1 shows one of the arteriolar networks from which data were collected. We obtained data in all numbered capillaries. However, we have not included the results obtained from capillaries six and seven since they did not originate at the arteriole. Networks were selected randomly with the restriction that they contained at least four clearly visible capillaries. A total of 39 capillaries at the arteriolar ends of networks (arteriolar capillaries) and 37 capillaries at the venular ends of networks (venular capillaries) were studied, although oxygen saturation was not measured in 3 venular capillaries for technical reasons. The sampled arteriolar and venular capillary networks did not form contiguous pathways. All data were obtained by off-line analysis of video tapes. Within each network, data for all capillaries were obtained over the same time interval.

FIG. 1.

Example of an arteriolar capillary network showing all readily distinguishable portions of capillaries. An arteriolar capillary is defined as that portion of the total capillary pathway which is in the same projected microscopic field as the arteriole which feeds it. The dashed lines represent capillaries which were barely visible and thus were not sampled for technical reasons. Note the relatively straight capillaries that are typical of both arteriolar and venular capillaries in the hamster retractor muscle.

Red blood cell velocity (v) was determined by the video-computer method of Tyml and Sherebrin (1980) as modified by Ellis et al. (1984). The method measures velocity in terms of the displacement of red blood cells and plasma gaps along the capillary that occur in a fixed time interval. Red blood cell velocity was determined in every visible capillary in a network which contained red blood cells even if the cells were stationary throughout the observation period resulting in a velocity of zero. The error associated with the determination of red blood cell velocity using this method is reported to be ±4% (Tyml and Sherebrin, 1980). Lineal density (i.e., the number of red blood cells per millimeter; N) was measured using the video-computer method developed by Ellis et al. (1984). The method provides a continuous measurement of lineal density based on frame-by-frame analysis of the spatial average of blood opacity over a selected length of capillary with an accuracy of approximately ± 0.25 red blood cells (Ellis et al., 1984). This method permits the determination of lineal density in all capillaries including those in which individual red blood cells can not be readily distinguished. Data for both red blood cell velocity and lineal density were collected at a rate of 15 samples/sec over a I-min interval. The value reported for each parameter is the mean of sixty I-sec averages of instantaneous determinations. Red blood cell frequency (f) was calculated from coincident determinations of instantaneous red blood cell velocity and lineal density. The value reported is the mean of sixty I-sec averages of these computed values.

Hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SO2) was determined at upstream and downstream locations on each capillary by the video-computer method of Ellsworth et al. (1987). The method utilizes the linear relationship between the ratio of optical densities determined at two appropriately chosen wavelengths (431 and 420 nm) and oxygen saturation. An average optical density was determined at each of the two wavelengths by sampling light intensities over a selected portion of a capillary (five TV lines), once each video frame for 30 sec. For capillaries in the hamster retractor muscle the relationship between the ratio of optical densities and oxygen saturation is SO2 — - 1.71 (OD431/OD420) + 2.20. The confidence interval for a single additional determination is ± 4.8% (Ellsworth et al., 1987).

Frequency-weighted oxygen saturations (SfO2) were determined from coincident measurements of oxygen saturation and red blood cell frequency from arteriolar and venular capillaries as SfO2 = ∑(SiO2fi)/∑fi where SiO2 and fi are the inlet or outlet oxygen saturations and red blood cell frequencies, respectively, in individual capillaries.

Oxygen flow was calculated as QO2 = cSO2 [Hb]rbc Vrbcf, where [Hb]rbc is the hemoglobin concentration within a single red blood cell, Vrbc is the volume of a red blood cell and c is a conversion factor from moles of oxygen to milliliters of oxygen. Data are presented in units of pl/sec.

The longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient was determined from coincident measurements of oxygen saturation at upstream (u) and downstream (d) sites on individual capillaries. This longitudinal gradient is equal to the difference between the upstream (SO2u) and downstream (SO2d) oxygen saturation divided by the distance (ΔZ) separating the two sites (ΔSO2/Δz = (SO2u − SO2d)/Δz). The two sites were selected as the most distant locations in the field from which reliable measurements could be obtained. In arteriolar capillaries the average distance between the upstream and downstream sites was 56.9 ± 31.6 um with the upstream site 18 ± 9 pm from the arteriole. In venular capillaries, the average distance between the two sites was 57.7 ± 39.3 um with the downstream site 22 ± 16 gm from the venule. A positive ΔSO2/Δz indicates a net loss of oxygen, while a negative ΔSO2/Δz indicates a net gain of oxygen. These data are presented in units of percentage per micrometer.

Capillary diameter, intercapillary distance, and Az were measured from the video monitor using a vernier caliper. The distance calibration was determined at the start of each experiment using a stage micrometer whose image was recorded on the video tape.

Data Analysis

All data are presented as means ± standard deviations. The coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean, CV, expressed either as percentage or decimal fraction) for each parameter was determined for arteriolar and venular capillaries combined and for each capillary network independently. An analysis of variance and Mann—Whitney U test were used to compare the oxygen transport parameters at the two ends of the network. An unpaired Student t test was used to evaluate the differences in the average coefficients of variation for all parameters in the two types of networks. All data analysis was done using a statistical software package (SAS Institute). Significance was assigned at P < 0.05 unless otherwise noted.

EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

Combining the data obtained for all capillaries (i.e., arteriolar plus venular) yielded mean values of red blood cell velocity (v) of 93.6 ± 48.3 μm/sec, lineal density (N) of 63.2 ± 29.9 cells/mm and red blood cell frequency (f) of 6.7 ± 4.6 cells/sec. Average capillary diameter (d) was 3.6 ± 0.4 pm. In evaluating relationships among the various hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters in these capillaries we found several significant although weak correlations in addition to those which would be expected due to the obligatory relationships among the parameters (e.g., v and f; SO2, and QO2). We found that red blood cell velocity was significantly correlated with lineal density (r = 0.38; P < 0.001) and oxygen saturation determined at the upstream site on a capillary was significantly correlated with the longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient (r = 0.40, P < 0.01).

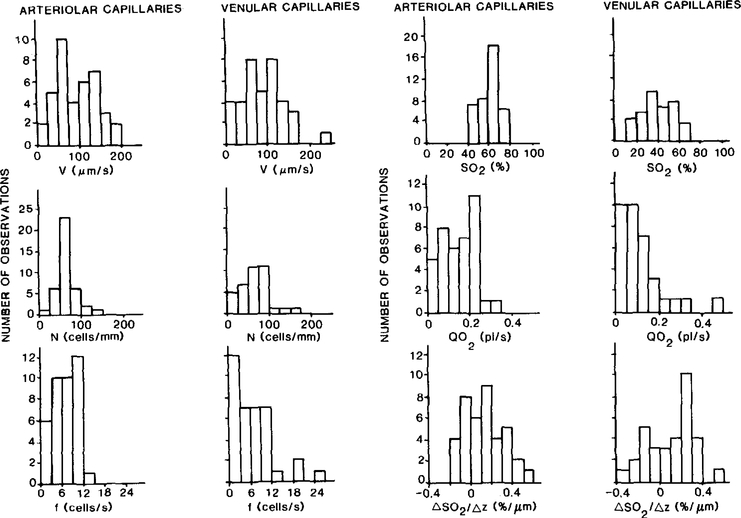

We subsequently classified the data according to the type of capillary network (i.e., arteriolar or venular). Capillaries located at the arteriolar end were classified as arteriolar capillaries, whereas capillaries at the venular end were classified as venular capillaries. The sampled arteriolar and venular capillary networks did not form contiguous pathways. The results of this division are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 2. Neither red blood cell velocity, lineal density, red blood cell frequency, nor longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient (ΔS02/Δz) was significantly different at the two ends. However, oxygen saturation (SO2) and oxygen flow (QO2) were significantly higher at the upstream ends of arteriolar capillaries compared with the downstream ends of venular capillaries. Red blood cell frequency weighted oxygen saturations (SfO2) at the upstream ends of arteriolar capillaries and the downstream ends of venular capillaries were found to be similar to the respective average values for oxygen saturations. This is an expected result since there was no significant correlation between the simultaneously determined values of red blood cell frequency and oxygen saturation. Capillary diameter was significantly larger in the venular capillaries although the physiological significance of the statistical difference is questionable due to the limits of resolution of the measuring system ( ± I TV line = 0.91 μm).

Table 1.

OXYGEN TRANSPORT PARAMETERS IN ARTERIOLAR AND VENULAR CAPILLARIES

| Parameters | n | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arteriolar | |||||

| v (μm/sec) | 39 | 97.3 | 45.9 | 12.0 | 197.6 |

| N (cells/mm) | 39 | 64.1 | 23.4 | 22.0 | 149.3 |

| f (cells/sec) | 39 | 6.6 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 13.0 |

| SO2 (%) | 39 | 60.8** | 9.8 | 42.0 | 73.0 |

| SfO2 (%) | 39 | 61.6 | |||

| QO2 (pl/sec) | 39 | 0.150* | 0.081 | 0.005 | 0.333 |

| ΔSO2/Δz (%/μm) | 39 | 0.120 | 0.180 | −0.204 | 0.544 |

| Diameter (μm) | 39 | 3.4** | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.1 |

| Venular | |||||

| v (μm/sec) | 37 | 89.7 | 51.1 | 0 | 233.0 |

| N (cells/mm) | 37 | 62.3 | 35.8 | 0 | 160.4 |

| f (cells/sec) | 37 | 6.7 | 5.7 | 0 | 24.0 |

| SO2 (%) | 34 | 39.9 | 13.8 | 17.8 | 64.2 |

| SfO2 (%) | 34 | 40.3 | |||

| QO2 (pl/s) | 34 | 0.108 | 0.095 | 0.006 | 0.459 |

| ΔS02/Δz (%/μm) | 33 | 0.098 | 0.214 | −0.397 | 0.511 |

| Diameter (μm) | 37 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 3.1 | 4.8 |

Statistically significant differences between arteriolar and venular capillaries at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

Statistically significant differences between arteriolar and venular capillaries at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01, respectively.

FIG. 2.

Histograms of red blood cell velocity (v), lineal density (N), red blood cell fequency (f), oxygen saturation (SO2), oxygen flow (Q02), and the longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient (ΔS02/Δz) in arteriolar and venular capillaries.

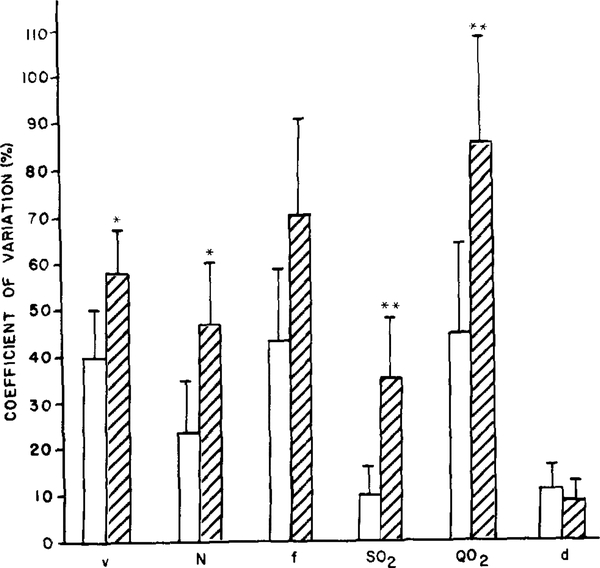

To assess the extent of spatial variability in the hemodynamic and oxygenation parameters, we evaluated the coefficient of variation for each parameter in each network and determined a mean for the arteriolar (n = 5) and venular (n = 5) networks (Fig. 3). We found that the variability in red blood cell velocity, lineal density, oxygen saturation, and oxygen flow was significantly greater in the venular capillaries.

FIG. 3.

Average coefficients of variation (CV) of oxygen transport parameters obtained for five arteriolar (open bars) and five venular (hatched bars) capillary networks. ** and * indicate significant difference between data obtained for arteriolar and venular capillary networks at P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively.

THEORETICAL MODEL

The computer simulation was designed to predict the distributions of oxygen in capillaries and tissue using realistic, experimentally determined values of input parameters and to examine the impact of heterogeneities of capillary geometry and hemodynamics on these distributions. The model permits us to eliminate different heterogeneities, one at a time, thus enabling us to attribute observed changes in the distribution of oxygen to heterogeneities in specific parameters.

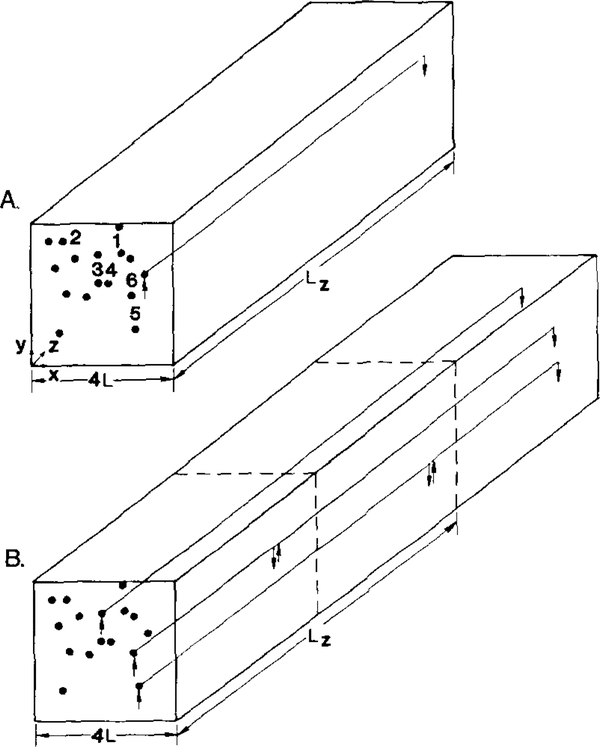

The model, described in more detail in the Appendix, considers a slab of tissue penetrated by 16 parallel capillaries without anastomotic connections as shown in Fig. 4. We assume that oxygen diffusion and consumption in the tissue are spatially homogeneous and time-independent. Then, the tissue transport of oxygen is governed by the equation

| (1) |

where Pt is tissue PO2, D is the oxygen diffusion coefficient in the tissue, α is the oxygen solubility coefficient, and M is the oxygen consumption rate.

FIG. 4.

Geometry of the theoretical models: (A) Constant capillary flow path length; (B) Distributed capillary flow path length (see text).

In the capillary, oxygen is transported by convection along the capillary and by diffusion in both red blood cells and plasma. The mass balance of oxygen along the capillary can be expressed in terms of the “mixing-cup” hemoglobin saturation as

| (2) |

where f is red blood cell frequency, Vrbc is the volume of a red blood cell, CHb is the oxygen-binding capacity of hemoglobin inside the red blood cell, SO2(Pi) is the equilibrium oxyhemoglobin dissociation relationship, J is the capillary tissue O2 flux, i.e., the amount of oxygen exchanged across the capillary wall per second per unit length of the capillary, and i is an index that labels each capillary. In Eq. (2), the amount of dissolved oxygen is neglected since it is small in comparison with the amount of oxygen bound to hemoglobin. Under normoxic conditions at normal systemic hematocrit, the chemical reaction between hemoglobin and oxygen is close to equilibrium (Clark et al., 1985; Federspiel and Popel, 1986; Gutierrez, 1986). Thus, oxygen saturation is a function of PO2.

The data on 39 arteriolar capillaries for which we have simultaneously determined values of red blood cell frequency, f, inlet (upstream) hemoglobin oxygen saturation, Sin lineal density, N, and capillary radius, r, were assigned to capillaries in three tissue slabs similar to those shown in Fig. 4A: Slab 1 with capillaries 1—16; slab 2 with capillaries 17—32; slab 3 with capillaries 33—39 and 1—9. Capillaries were distributed randomly (Poisson distribution) in the plane normal to their axes. The values of f,Sin, and r were used directly, whereas the values of N were used in the calculations of the mass transfer coefficient at the capillary wall for each capillary as explained in the Appendix. Input parameters of the model are presented in the Appendix. Equations (1) and (2) with boundary conditions described in the Appendix were solved numerically using a central finite difference scheme (Popel et al., 1986). Solution of Eq. (1) for each plane z constant was obtained on an 88 × 88 grid using the successive overrelaxation method. After the capillary-tissue oxygen fluxes were determined, the fourth-order Adams-Bashforth method was applied to solve the equations in the z direction using about 50 intervals. The numerical solution of the model yielded the distributions of SO2 and PO2 along the capillaries as well as the P02 distribution within the tissue.

Capillary Flow Pathway Models

We evaluated two models of capillary flow pathways that always contained 16 capillaries at any given cross section. In Model A each capillary flow pathway consisted of a single capillary whose length was equal to the anatomical arteriole— venule distance (Lz = 412 μm), thus ignoring any heterogeneity in this parameter. In the second model, Model B, Lz is also equal to 412 μm, but it does not always constitute the capillary flow path length. The following arrangement of capillaries was assumed. All capillaries begin at the plane z = 0. However, some end at the plane z = Lz/2 while others continue on. Additional capillaries terminate at z = Lz and at 3Lz/2. When a capillary terminates before reaching the end of the network (z = 3Lz/2), a new capillary immediately begins as indicated by the vertical upward and downward arrows in Fig. 4B. Each new capillary is assigned the same input values as the original capillary. The output values of the terminated capillaries are incorporated into the determination of end-capillary oxygen saturation. Thus, in Model B there are three groups of capillaries with lengths Lz/2, Lz, and 3Lz/2. We have considered two capillary configurations. In the first, 4 capillaries terminate at z Lz/2 and four more at z = Lz. Thus, the slab contains 24 capillaries with 8 in each group. In this unit, total capillary length is 412 ± 172 gm. In the second configuration, 5 capillaries terminate at the plane z = Lz/2 and 6 at z L2. Thus, there are a total of 27 capillaries with 1l, 11, and 5 capillaries in each respective group. In this unit, capillary length is 366 ± 162 μm. Model B thus allows us to simulate heterogeneity of capillary flow pathways, at least qualitatively, subject to limitations of the geometry of the model.

Model A: Homogeneous Flow Pathways

The results of the simulation for three slabs each containing 16 capillaries are presented in Table 2. Shown in the table are the input hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SaO2; mean and CV) taken from the experimental data obtained from this study, and the calculated characteristics of end-capillary oxygen saturation (SvO2) and tissue PO2 (Pt) For the three slabs with different input values, the mean values of arterial oxygen saturation were somewhat different but the mean oxygen saturation difference (SaO2 — SvO2) was approximately 20% for each of the slabs with the predicted values of end-capillary SO2 similar to those found experimentally. The coefficients of variation of the calculated end-capillary SO2 (SvO2) are similar for all the slabs and are lower than the corresponding coefficients of variation of SaO2. Combining the results from all the slabs more than doubles the coefficient of variation (4 to 9%) suggesting an equal contribution of dispersion among different slabs relative to that within a slab. The mean tissue PO2 values calculated over the entire tissue slab and their corresponding coefficients of variation determined for the three slabs individually and for the three combined are similar.

Table 2.

Theoretical Predictions of 02 Distribution in Resting Retractor Muscle

| Experimental |

Predicted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input Sa02 |

Sv02 |

P |

||||

| Mean (%) |

CV (%) |

Mean (%) |

CV (%) |

Mean (mm Hg) | CV (%) |

|

| Model A | ||||||

| Experimental input values | ||||||

| Slab 1 (caps 1–16) | 63 | 14 | 43 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Slab 2 (caps 17–32) | 58 | 19 | 37 | 4 | 27 | 10 |

| Slab 3 (caps 33–39, 1–9) | 66 | 11 | 45 | 4 | 30 | 10 |

| Slabs 1,2,3 combined | 62 | 15 | 45 | 9 | 29 | 11 |

| Modified input values (Slab 1) | ||||||

| All values constant and equal to the mean | 63 | 0 | 42 | 0 | 30 | 9 |

| Square capillary array | 63 | 14 | 42 | 4 | 30 | 10 |

| Constant d | 63 | 14 | 43 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Constant Sa02 | 63 | 0 | 42 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Constant f | 63 | 14 | 42 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Constant mass transfer coefficient | 63 | 14 | 43 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Infinite mass transfer coefficient | 63 | 14 | 43 | 4 | 29 | 10 |

| Model B | ||||||

| Configuration 1 | ||||||

| Lcap = 412 ± 172 μm, n = 24 | 61 | 16 | 39 | 21 | 27 | 14 |

| Configuration 2 | ||||||

| Lcap - 366 ± 162 gm, n = 27 | 60 | 16 | 42 | 16 | 28 | 12 |

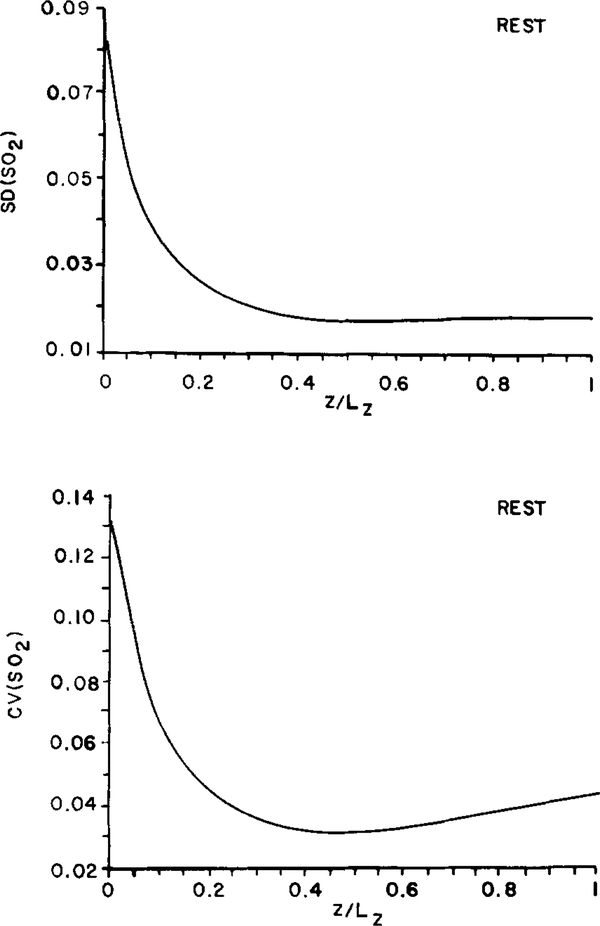

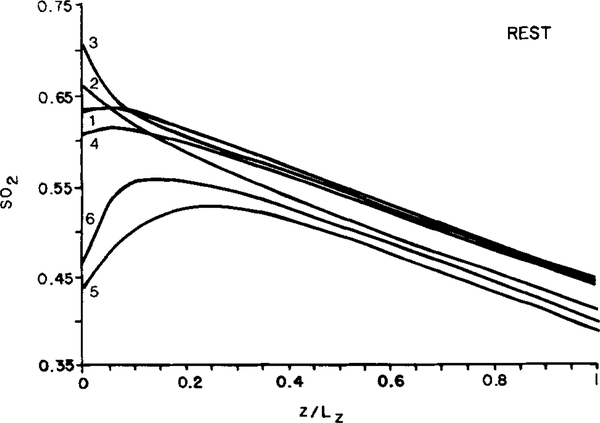

Since the differences among slabs were small, we chose a single slab (slab l) for the following calculations. As described above, the oxygen saturation distribution toward the venular end of the slab becomes more homogeneous, as evaluated by either the standard deviation or the coefficient of variation. Figure 5 shows the standard deviation, SD(SO2), and coefficient of variation, CV(SO2), of oxygen saturation determined for the group of 16 capillaries as a function of position along the slab, z/Lz. Both variables decrease sharply along the first 25% of the total length and thereafter remain relatively constant while the mean saturation decreases linearly with distance along the entire length of the slab. This increased homogeneity in SO2 results from a strong effect of diffusive shunts among adjacent capillaries. Figure 6 shows the distribution of SO2 in the six capillaries labeled in Fig. 4A. Clearly, the capillaries with low initial oxygen saturation pick up oxygen from their neighbors while those with high initial oxygen saturation give up oxygen faster than their neighbors. After about 25% of the total capillary length, the oxygen saturations vary linearly with z for the remaining portion of the slab. However, the saturations never completely equilibrate due to heterogeneities in the other variables. The gradients of SO2 become essentially equal in the different capillaries, as manifested by equal slopes of the SO2 curves.

FIG. 5.

Model predictions of the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of fractional hemoglobin oxygen saturation (SO2) along a tissue slab containing 16 parallel capillaries of uniform flow path length distributed randomly in resting muscle.

FIG. 6.

Model predictions of the distribution of fractional oxygen saturation (SO2) in 6 of the 16 parallel capillaries of uniform flow path length (labeled 1—6 in Fig. 4A) in resting muscle.

According to Eq. (2) for capillary transport, the capillary-tissue 02 flux, Ji, is then proportional to red blood cell frequency, fi, i.e., capillaries with higher frequency of red blood cells release proportionally larger amounts of oxygen and, therefore, supply larger volumes of tissue.

To attempt to pinpoint the source of the residual heterogeneities, we first examined the geometrical factors which might affect the distribution of oxygen (Table 2). We replaced the random distribution of capillaries by a regular square array and the individual values of capillary radius by the mean value for the slab. Neither change affected the predicted coefficient of variation of SvO2. Replacing the distributions of Sa02 or f by their respective mean values likewise did not alter CV(SvO2). Finally, replacing the mass transfer coefficients by the mean value or making them infinite, i.e., neglecting the intracapillary resistance to oxygen transport, had no effect on either CV(SvO2) or CV(Pt). Therefore, the CV(SvO2) is approximately 4% when all heterogeneities of input parameters are present and when the parameter distributions are replaced one at a time by their mean value. The CV(SvO2) equals zero when all parameters are replaced by their respective mean values.

Since there was some uncertainty of the exact value of oxygen solubility in the retractor muscle, we evaluated the impact of an alteration in this quantity on these determinations. Mahler et al. (1985) reported that oxygen solubility in frog sartorius muscle was 1.26 times its solubility in bulk water (αH2O = 3.1 × 10 −5 ml O2/ml mm Hg) which yields a value of 3.9 × 10 −5 ml 02/ml mm Hg, a value higher than that employed in the above calculations. The effect of such an increase in oxygen solubility on the computed result was to decrease the coefficients of variation of SvO2 and Pt to 3 and 9%, respectively.

Thus, within the framework of the model, certain characteristics of oxygen distribution in resting striated muscle are practically insensitive to the distributions of hemodynamic and geometric variables. However, it is premature to conclude that heterogeneities in these parameters do not play a role in muscle oxygenation. As will be discussed below, these factors may become crucial when oxygen demand is increased, as occurs with exercise.

Model B: Heterogeneous Flow Pathways

Model B, unlike Model A above, assumes that capillary flow path lengths are nonuniform, allowing us to evaluate, at least qualitatively, the impact of heterogeneities in this parameter on oxygen transport. By terminating some capillaries at the planes z = Lz/2, Lz or 3Lz/2, we produced capillaries with different flow path lengths within the same tissue slab. We have previously defined two capillary configurations. In the first, mean capillary flow path length (Lcap) was 412 μm for 24 capillaries while in the second, Lcap was 366 gm with 27 capillaries. The results of calculations for these configurations are presented at the bottom of Table 2. For the statistics, end-capillary oxygen saturations in all capillaries are included. For both cases, the coefficient of variation for Sv02 increased significantly to 21 and 18%, respectively, compared with 4% in Model A. These results from Model B are closer than those of Model A to the results obtained experimentally, CV(SvO2) - 35%, (Table 1). However, even for Model B the predicted end-capillary SO2 values are significantly less heterogeneous than the experimental values. We should note that any model with heterogeneous capillary path length distribution would also contain assumptions concerning the locations of arteriolar inflows and venular outflows, e.g., Model B. Depending on capillary geometry, “capillary density” could also be variable. Thus, instead of the effect of capillary path length heterogeneity it is more appropriate to speak more generally in terms of the “capillary network effect.” We also note that in Model B there is a possibility for significant gradients of tissue PO2 in the direction parallel to the capillaries in the regions adjacent to the ending of one capillary and the starting of another. Axial diffusion in the tissue was neglected in Eq. (1). If axial diffusion were taken into account, heterogeneity of SvO2 should increase further. These modifications, i.e., a more realistic network model of the capillary bed and diffusion in three dimensions, should be incorporated in the future development of the mathematical model.

DISCUSSION

The experimental data obtained in this study from the retractor muscles of young hamsters demonstrate a number of expected results as well as some others which were quite unexpected. We found that there were no statistical differences between any of the hemodynamic parameters determined at the two ends of the network. This result appears contrary to current thinking which indicates that the values of all these parameters should be lower in venular capillaries since the number of capillaries is thought to increase toward the venular end of the network. However, we are unaware of any published reports quantifying this fact for randomly selected arteriolar and venular capillary networks which do not form a contiguous pathway. We did find that red blood cell velocity, lineal density, and intercapillary distance were slightly lower in venular capillaries than in arteriolar capillaries. However, the variability in all of these parameters is extensive, preventing any demonstration of a statistical difference between the data obtained at the two ends. Klitzman and Johnson (1982) reported that red blood cell velocity in capillaries toward the venous end of the network in the hamster cremaster muscle was 152 ± 88 (SD) μm/sec. by Sarelius (1986) 138 ± 58 (SD) μm/sec obtained by determining the average velocity of the red cells traversing a complete capillary flow pathway (arteriole to venule) in the same preparation. Thus, although our results appear to differ from current concepts, they represent the first direct evaluation of this issue.

Our finding of significant heterogeneities in oxygen transport parameters, especially at the venular ends of the networks, is not unexpected. The heterogeneity in the hemodynamic parameters reported here is not unique to the hamster retractor muscle or even to mammalian muscle. Similar mean values and coefficients of variation have been obtained for red blood cell velocity, lineal density, and red blood cell frequency in hamster cheek pouch (Pittman and Okusa, 1983), cremaster (Klitzman and Duling, 1979; Sarelius et al., 1981; Klitzman and Johnson, 1982; Damon and Duling, 1984) and sartorius (Damon and Duling, 1984) muscles and frog sartorius muscles (Tyml and Groom, 1980; Tyml et al., 1981; Ellis et al., 1984; Groom et al., 1986). However, this present study is unique in that it represents the first time that the oxygen saturation of the red blood cells within these capillaries has been measured in conjunction with the hemodynamic parameters thus enabling us to directly evaluate convective oxygen transport in striated muscle capillaries.

The finding that heterogeneity in red blood cell velocity, lineal density, oxygen saturation, and oxygen flow is greater in capillaries feeding a single venule compared with those fed by a single arteriole is not entirely unexpected for two principal reasons. First, the capillaries which feed a single venule do not all originate from a single arteriole, so that differences could be introduced as a consequence of different input values. A second contributing factor is that the pathways traveled by the red blood cells are not the same in all capillaries. Sarelius (1986) reported that the lengths of red blood cell flow pathways in the cremaster muscles of hamsters similar in age to those reported here were 351 ± 134 um (CV = 36%). The impact of this magnitude of flow pathway heterogeneity on venous oxygen saturation was evaluated theoretically in this study and found to induce a four to fivefold increase in the predicted dispersion of oxygen saturation compared with the case of no pathway heterogeneity (Table 2).

The impact of the observed heterogeneities in intercapillary distances, capillary diameters, capillary oxygen saturation, and red blood cell frequency on oxygen distribution was evaluated theoretically and found to be negligible in resting muscle. This conclusion results from the finding that replacing any of the experimentally determined distributions with the corresponding mean value did not alter the small degree of heterogeneity in the predicted oxygen saturation at the venous end of the capillary network. Similarly, we found no effect of the intracapillary resistance to oxygen transport.

It is usually assumed, based on Krogh’s model of oxygen transport, that oxygen saturation decreases linearly along the length of the capillaries. However, the theoretical model predicts that although the decrease in oxygen saturation appears linear at the venular end of the network, there are significant deviations from linearity at the arteriolar end due to diffusional interactions among neighboring capillaries, a result suggested by our experimental data. We found that the average longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient obtained from measurements on single capillaries (local ΔS02/Δz) was 0.113 ± 0.196 %/μm with no statistical difference observed between arteriolar and venular capillaries. However, when we compared these data with the average longitudinal saturation gradient obtained by dividing the difference in mean oxygen saturations determined at the upstream ends of arteriolar capillaries and the downstream ends of venular capillaries (60.8—39.9%) by the average anatomical capillary length (412 μm), we found that this latter quantity was smaller than the average local ΔSO2/Δz by a factor of 2. One possible explanation for this is the presence of diffusive interactions among capillaries in a network. We found that in both arteriolar and venular capillaries, approximately 1/3 of all capillaries gained oxygen, as evidenced by a negative longitudinal oxygen saturation gradient. In paired capillaries in which one capillary lost oxygen while the other capillary gained it, we found that the average loss was about twice the average gain, a result which is not unexpected since a portion of the oxygen lost would be consumed by the tissue in the immediate vicinity of the capillary.

Since the experimental data from arteriolar and venular capillaries were not obtained from contiguous capillary paths, and are therefore independent, comparisons of the experimental result with the theoretical model can only be qualitative.

When capillary flow pathways in the model were made nonuniform, the heterogeneity in end-capillary oxygen saturation increased four to fivefold (Table 2). If we incorporate this result with the observation that, when the data from the three slabs were combined (Table 2), the coefficient of variation of end-capillary oxygen saturation more than doubled, we obtain a coefficient of variation which is similar to that determined experimentally. We know that capillary flow pathways are not homogeneous and that all capillaries which feed into a single venule do not all originate from a single arteriole. Therefore, invoking these two factors we conclude that the theoretical predictions are consistent with the experimental data. However, in view of the assumptions made in formulating Model B, the calculations should be considered indicative of a trend toward increased heterogeneity. For quantitative comparison between theory and experiment, a more realistic capillary network model is necessary.

To ascertain if heterogeneities in oxygen transport parameters have an impact on oxygen transport in other situations of physiologic interest, we simulated the distribution of oxygen in isometrically contracting muscle under two conditions. In the first, flow was increased by a factor of 2 while muscle oxygen consumption was increased by a factor of 5. In the second, flow was increased by a factor of 5 and muscle oxygen consumption by a factor of 10. These conditions approximate the results of mild and heavy exercise obtained for cat soleus muscles (Bockman, 1983). All other input parameters were assumed to be the same as in resting muscle and Model A was used in the simulation. Thus, we do not take into account possible changes in intercapillary distance. The results are shown in Table 3. In both cases, the coefficients of variation of SvO2 increased dramatically from the resting value of 4% to 57% and 53%, respectively, while mean tissue PO2 (17 and 12 mm Hg, respectively) remained well above the critical level (Pcr = 0.5 mm Hg; Honig and Gayeski, 1982). To assess the adequacy of tissue oxygen supply we computed the ratio of the total amount of oxygen consumed in the slab to the maximum amount of oxygen that could be consumed if oxygen consumption were spatially constant, equal to MO as defined in the Appendix (Eq. (A1)). For the two cases presented above, this ratio equalled 0.99 and 0.96, respectively, indicating that the tissue was adequately supplied with oxygen.

Table 3.

THEORETICAL PREDICTIONS OF O2 DISTRIBUTION IN CONTRACTING RETRACTOR MUSCLE

| Experimental |

Predicted |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input SaO2 |

SvO2 |

Pt |

||||

| mean (%) |

CV (%) |

mean (%) |

CV (%) |

mean (%) |

CV (%) |

|

| “Mild Exercise” | ||||||

| Flow increased 2-fold 02 consumption increased 5-fold |

63 | 14 | 12 | 57 | 17 | 42 |

| “Heavy Exercise” | ||||||

| Flow increased 5-fold 02 consumption increased |

63 | 14 | 22 | 53 | 12 | 59 |

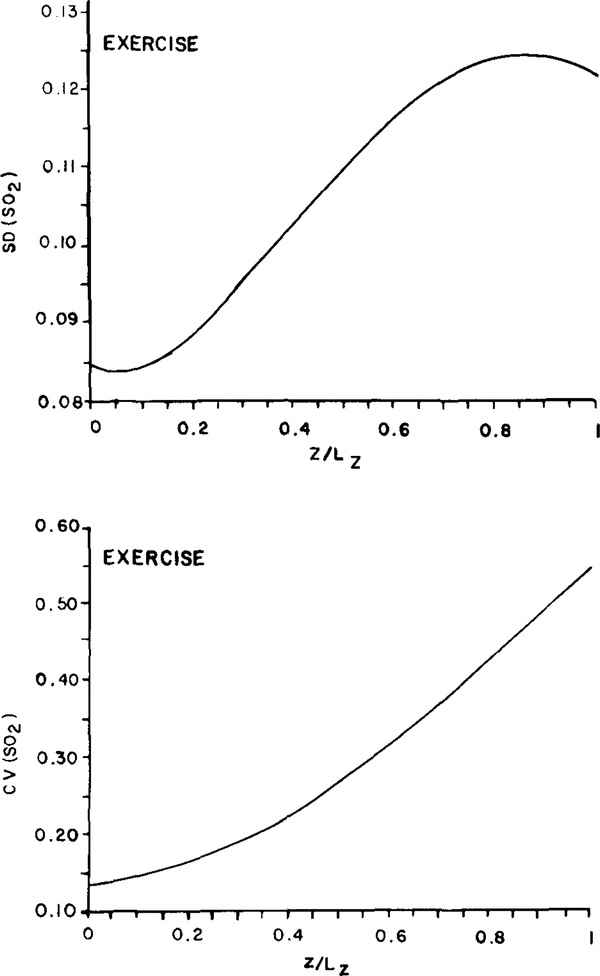

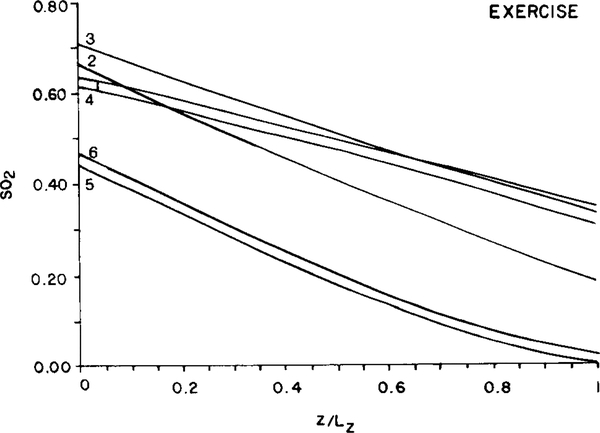

In resting muscle, the dispersion of oxygen saturation decreased gradually toward the venous end of the slab (Fig. 5) due to diffusive shunts between adjacent capillaries. In contracting muscle, the result is quite different. Figure 7 shows the distribution of SD(SO2) and CV(SO2) along the slab corresponding to the second case in Table 3 (“heavy exercise”). Apparently, the effect of diffusive shunting is not as important in this case as it was for resting muscle. The coefficient of variation increases monotonically with distance while the saturation averaged over the 16 capillaries decreases linearly with position, z. This latter result is similar to the finding for resting muscle and is a consequence of the tissue P02 in the bulk of the tissue remaining above the critical level. As a result, oxygen consumption remains essentially uniform throughout the muscle. Figure 8 shows the SO2 distribution for the same 6 capillaries that were presented in Fig. 6. Whereas in resting muscle capillaries with different inlet oxygen saturations equilibrated quickly with only a small residual heterogeneity remaining at the venous end, the effect of diffusive shunting in contracting muscle was surpassed by the impact of the other heterogeneities present.

FIG. 7.

Model predictions of the standard deviation (SD) and coefficient of variation (CV) of fractional hemoglobin oxygen saturation (S02) along a tissue slab for a group of 16 parallel capillaries of uniform flow path length distributed randomly in contracting muscle. Note that the vertical scales differ from those used in Fig. 5 for resting muscle.

FIG. 8.

Model predictions of the distribution of fractional oxygen saturation (SOJ in 6 of the 16 capillaries of uniform flow path length in contracting muscle. Capillary locations and designations are identical to those used in Fig. 6. Note that the vertical scale differs from that used in Fig. 6 for resting muscle.

In the simulation presented above we have assumed that the degree of heterogeneity in the input parameters is equal to those determined for resting muscle. There is experimental evidence that heterogeneity of red blood cell velocity in capillaries evaluated in terms of a coefficient of variation is similar in resting and contracting muscle (Damon and Duling, 1985). However, no data exist on heterogeneity of inlet capillary oxygen saturation in contracting muscle, or even its mean value. Repeating the above calculations for the case of heavy exercise using a mean value of Sa02 = 63% and a CV(SO2) — 0%, the coefficient of variation of end-capillary SO2 decreased slightly from 53 to 51%. However, when inlet SO2 was increased to 78% (PaO2 = 47 mm Hg), CV(SvO2) decreased to 33%. A further decrease to a coefficient of variation of 24% was observed when input SO2 was increased to 88% (PaO2 = 60 mm Hg).

The data presented here represent the first reports of simultaneous measurements of convective oxygen transport parameters in a striated muscle. The incorporation of these data into a theoretical model has enabled us to directly evaluate the role of the observed heterogeneities in these parameters on muscle oxygen transport rather than simply speculate on their potential impact. The results of this analysis indicate that the geometric and hemodynamic heterogeneities present in the capillary circulation likely play a qualitatively different role in different metabolic states. While such heterogeneities are of little importance in states of low metabolic rate where the tissue receives oxygen well in excess of its needs, they may play a major role in the distribution of oxygen in states of high metabolic rate.

APPENDIX

The Model

The model considers a slab of tissue penetrated by 16 parallel capillaries without anastomotic connections as shown in Fig. 4. We assume that oxygen diffusion and consumption in the tissue are spatially homogeneous and timeindependent. Then, the tissue transport of oxygen is governed by Eq. (1). Diffusion in the z direction (parallel to the capillary axis) is neglected in comparison to diffusion in the x and y directions, an assumption that is consistent with a large ratio of capillary length to intercapillary distance. The oxygen consumption rate of the tissue is assumed to follow Michaelis—Menten kinetics

| (A1) |

where Pcr is the critical tissue PO2 at which the consumption is equal to 50% of its maximum value and M0 is the maximum consumption under specified conditions.

The boundary conditions at the capillary-tissue interface reflect the intracapillary resistance to oxygen transport

| (A2) |

where ji is the oxygen flow per unit area of the capillary-tissue interface, n is distance normal to the interface, ki is the mass transfer coefficient, Pi is the intercapillary PO2, Pint is the tissue PO2 at the capillary-tissue interface, and i is an index that labels each capillary. The integral in equation (A2) is taken over the circumference of a capillary.

We assume that the bulk of the tissue is composed of tissue slabs shown in Fig. 4 which form a periodic structure. Thus, we impose periodic boundary conditions at the lateral boundaries of the slab

| (A3) |

At the capillary inlets, hemoglobin oxygen saturation, SO2, is specified. The numerical solution of the model yields the distributions of SO2 and P2 along the capillaries, S(z) and P(z), as well as the PO2 distribution within the tissue,pt(x,y,z).

Parameters of the Model

Most of the parameters utilized in the model have been derived from measurements obtained for hamster blood or the hamster retractor muscle. All values are referenced to 37°. The diffusion coefficient (D = 1.39 × 10 −5 cm2/sec) was measured in vitro in retractor muscles of adult hamsters (Ellsworth and Pittman, 1984). The solubility coefficient (α = 2.84 × 10 −5 ml 02/(cm3 tissue mm Hg)) was computed from a comparison of experimental data obtained by Sullivan and Pittman (1984) and Ellsworth and Pittman (1984) for retractor muscles of adult hamsters (cf., see discussion in Mahler et al., 1985). Oxygen consumption of the resting hamster retractor muscle (M = 0.89 ml O2/(100 g min) = 1.57 × 10−4 ml O2/(ml sec)) was measured in vitro (unperfused muscle) in adult hamsters (Sullivan and Pittman, 1984). Red blood cell volume (Vrbc — 69.3 μm3) was taken from measurements of Sarelius et al. (1981) for immature hamsters, a value which is slightly higher than that determined for adult hamsters (Meyerstein and Cassuto, 1970; Sarelius et al., 1981). The oxygen binding capacity of hemoglobin (CHb 0.5 ml 02/ml Hb) was calculated as the product of the hemoglobin concentration within a single red blood cell ([Hb] — 19.58 mM; Meyerstein and Cassuto, 1970) and a factor to convert moles of oxygen to milliliters of oxygen (c = 25.4 × 103 ml O2/mole at 37°). The critical tissue oxygen tension, Pcr, was chosen as 0.5 mm Hg (Honig and Gayeski, 1982). However, its exact value is not important for the present study since the predicted tissue P02 values in the resting muscle are well above the critical value.

The parameters of the oxygen dissociation curve required to convert measurements of oxygen saturation to oxygen tension were determined by fitting the data for hamster blood obtained by Ulrich et al. (1963) to a linear representation of the Hill equation. The linear regression fit of In P02 vs In (S02/(100-S02)) yields a PO2 at which hemoglobin within the red blood cell is 50% saturated (P50) of 26.7 mm Hg and a Hill coefficient (n) of 2.2 (r — 0.995) under standard conditions (pH, 7.40, PCO2 = 40 mm Hg, 37°) for oxyhemoglobin saturations ranging between 30 and 90%. Under experimental conditions similar to those employed here, systemic arterial PCO2 was 56.3 mm Hg and pH was 7.32 (unpublished observations). Employing the correction for nonstandard values of pH (Ulrich et al., 1963) and PCO2 (Keirnan, 1966),

| (A4) |

we obtained a P50of 29.3 mm Hg.

Experimental data on the capillary mass transfer coefficient are not available so we had to rely on theoretical estimates derived for the problem of oxygen transport from spherical erythrocytes moving through a cylindrical tube (Federspiel and Popel, 1986). These estimates present the dimensionless mass transfer coefficient, K = Wkd/Da as a function of the ratio of intererythrocyte distance to erythrocyte length, where k is the dimensional mass transfer coefficient in (A2). Erythrocyte shape was assumed cylindrical with the ratio of cell radius to capillary radius equal to 1.25. The values of the mass transfer coefficient presented in Fig. 3b of Federspiel and Popel (1986) were used. The calculated mean for the mass transfer coefficient for the 39 arteriolar capillaries is 9.6 (range: 2.1—15.3). Although the assumption that the erythrocyte shape is cylindrical is not consistent with the assumption of Federspiel and Popel (1986) that the cells are spherical, the final results for resting muscle turn out to be practically independent of K. In the case of contracting muscle the intracapillary resistance to oxygen transport is expected to be of significance, thus additional theoretical work needs to be done to investigate the effect of erythrocyte shape on the mass transfer coeffcient.

The mean intercapillary distance, L = 26.4 μm, was determined in vivo for the capillary network from which experimental data were obtained by measuring the distance between capillaries which were judged to be in equal focus. Since the depth of focus for the objective we used is 1.4 μm (Slayer, 1970), capillaries in equal focus should lie in the same plane. Thus, the distance measured between them should provide a good estimate of intercapillary distance. This value is used in the calculations as follows. In the model, a square cross section of the slab contains 16 capillaries arranged either in a square array or distributed randomly so that they do not cross the boundary. Thus, with the dimension of the square 4L, as illustrated in Fig. 4, the model configurations correspond to a capillary density, nc = L−2 1435 capillaries/mm2. The anatomical distance between neighboring terminal arterioles and venules was found experimentally to be 412 ± 119 μm (n = 19).

Parameters n Mean SD Minimum Maximum

Arteriolar

Experimental Predicted mean cv mean cv mean cv

(70) (mm Hg)

IO-fold

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Jeanette Skelton for her expert technical assistance and Fransisco Varela for his help with the computer simulation. This study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, U.S. Public Health Service (HL-18292), and A.D. Williams Fund for Research. Software for the determination of red blood cell velocity and lineal density was purchased from the Microcirculation Group, Department of Medical Biophysics, Univ. of W. Ontario.

REFERENCES

- BOCKMAN EL (1983). Blood flow and oxygen consumption in active soleus and gracilis muscles in cats. Am. J. Physiol 244:H546–H551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK A, FEDERSPIEL WJ, CLARK PAA, AND COKELET GR (1985). Oxygen delivery from red cells. Biophys. J 47, 171–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMON DH, AND DULING BR (1984). Distribution of capillary blood flow in the microcirculation: An in vivo study using epifluorescent microscopy. Microvasc. Res 27, 81–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAMON DH, AND DULING BR (1985). Evidence that capillary perfusion heterogeneity is not controlled in striated muscle. Amer. J. Physiol 249, H386–H392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS CG, FRASER S, HAMILTON G, AND GROOM AC (1984). Measurement of lineal density of red blood cells in capillaries in vivo, using a computerized frame-by-frame analysis of video images. Microvasc. Res 27, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLIS CG, POTTER RF, AND GROOM AC (1984). Continuous measurement of red cell velocity in capillaries with flow reversals, using a video computer technique. Microvasc. Res 27, 241. [Google Scholar]

- ELLSWORTH ML, AND PITTMAN RN (1984). Heterogeneity of oxgyen diffusion through hamster striated muscle. Amer. J. Physiol 246, H161–H167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELLSWORTH ML, PITTMAN RN, AND ELLIS CG (1987). Measurement of hemoglobin oxygen saturation in capillaries. Amer. J. Physiol 252, H1031–H1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FEDERSPIEL WJ, AND POPEL AS (1986). A theoretical analysis of the effect of the particulate nature of blood on oxygen release in capillaries. Microvasc. Res 32, 164–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROOM AC, ELLIS CG, WRIGLEY SM, AND POTTER RF (1986). Architecture and flow patterns in capillary networks of skeletal muscle in frog and rat In “Microvascular Networks: Experimental and Theoretical Studies” (Popel AS and Johnson PC, Eds.), pp. 61–76. Karger, Basel. [Google Scholar]

- GUTIERREZ G (1986). The rate of oxygen release and its effect on capillary 02 tension: A mathematical analysis. Resp. Physiol. 63, 79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HONG CR, AND GAYESKI TEJ (1982). Correlation of 02 transport on the micro and macro scale. Int. J. Microcirc: Clin. Exp 1, 367–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KELMAN GR (1966). Digital computer subroutine for the conversion of oxygen tension into saturation. J. Appl. Physiol 21, 1375–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLITZMAN B, AND DULING BR (1979). Microvascular hematocrit and red cell flow in resting and contracting striated muscle. Amer. J. Physiol 237, H481–H490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLITZMAN B, AND JOHNSON PC (1982). Capillary network geometry and red cell distribution in hamster cremaster muscle. Amer. J. Physiol 242, H211–H219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROGH A (1929). “The Anatomy and Physiology of Capillaries” Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT. [Google Scholar]

- MAHLER M, LOUY C, HOMSHER E, AND PESKOFF A (1985). Reappraisal of diffusion, solubility, and consumption in frog skeletal muscle, with applications to muscle energy balance. J. Gen. Physiol 86, 105–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYERSTEIN N, AND CASUTO Y (1970). Haematological changes in heat-acclimatized Golden hamsters. Brit. J. Haematology 18, 417–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PITTMAN RN, AND OKUSA MD (1983). Measurements of oxygen transport in single capillaries In “Oxygen Transport to Tissue IV” (Bicher HI and Bruley DF, Eds.), pp. 539–553, Plenum, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POPEL AS, CHARNY CK, AND DVINSKY AS (1986). Effect of heterogeneous oxygen delivery on oxygen distribution in skeletal muscle. Math Biosci. 81, 91–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARELIUS IH (1986). Cell flow path influences transit time through striated muscle capillaries. Amer. J. Physiol 250, H899–H907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SARELIUS IH, DAMON DN, AND DULING BR (1981). Microvascular adaptations during maturation of striated muscle. Amer. J. Physiol 241, H317–H324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SLAYTER EM (1970). “Optical Methods in Biology”, pp. 275–279. Wiley, New York. [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN SM, AND PITTMAN RN (1982). Hamster retractor muscle: A new preparation for intravital microscopy. Microvasc. Res 23, 329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SULLIVAN SM, AND PITTMAN RN (1984). In vitro 02 uptake and histochemical fiber type of resting hamster muscles. J. Appl. Physiol 57, 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYML E, ELLIS CG, SAFRANYOS RF, FRASER S, AND GROOM AC (1981). Temporal and spatial distributions of red cell velocity in capillaries of resting skeletal muscle, including estimates of red cell transit times. Microvasc. Res 22, 14–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYML K, AND GROOM AC (1980). Regulation of blood flow in individual capillaries of resting skeletal muscle in frogs. Microvasc. Res 20, 346–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TYML K, AND SHEREBRIN MH (1980). A method for on-line measurements of red cell velocity in microvessels using computerized frame-by-frame analysis of television images. Microvasc. Res 20, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ULRICH S, HILPERT P, AND BARTELS H (1963). Uber die Atmungsfunktion des Blutes von Spitzmausen, weissen Mausen und syrischen Goldhamstern. Pflugers Arch. 277, 150–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]