Abstract

Objective

To assess residency applicants' use and perceptions of Doximity Residency Navigator (DRN) and to analyze the impact of Doximity reputation rankings on application, interview acceptance, and match list ranking decisions.

Participants and Methods

We developed and distributed a survey seeking feedback from residency applicants to describe their use of DRN during the 2017 residency recruitment and match process. The dates of the study were March 1, 2017, through May 8, 2017.

Results

We received responses from 2152 of 12,617 applicants (17%) across 24 graduate medical education programs. Sixty-two percent of respondents (n=1339) used DRN during the residency application, interview, and match list process. Doximity reputation rankings were noted to be valuable or very valuable to 78% of respondents (958 of 1233). Overall, 79% of respondents (977 of 1241) reported that Doximity reputation rankings influenced their application, interview acceptance, or match list ranking decisions. When asked about the accuracy of Doximity reputation rankings, 56% of respondents (699 of 1240) believed that rankings were slightly accurate or not accurate. The most commonly used resources to research potential residency programs were residency program websites, American Medical Association resources, and DRN.

Conclusion

Most survey respondents used DRN during the application, interview, and match ranking process. Doximity reputation rankings were found to be the most valuable resource in DRN, although more than 50% of responders had doubts about the accuracy of reputation rankings.

Abbreviations and Acronyms: AAMC, Association of American Medical Colleges; DRN, Doximity Residency Navigator; GME, graduate medical education; MCSGME, Mayo Clinic School of Graduate Medical Education; NRMP, National Residency Match Program

The process of selecting residency programs to submit applications to and interview with can be a daunting task for those seeking graduate medical education (GME) positions. Applicants have a variety of resources available to research potential residency training programs. The National Residency Matching Program (NRMP) surveyed applicants to residency programs in 2015 and found residency program reputation, geographic location, interview day experience, and perceived goodness of fit to be the most important factors that applicants considered when applying to and ranking residency programs.1 Accurate assessment of a residency program's reputation has long been a difficult task due to varying degrees of interpretation and bias.

Doximity is the largest social networking application for health care professionals and medical students. The Doximity Residency Navigator (DRN; Doximity, Inc) was developed to “help medical students make informed residency decisions and to increase transparency in the residency match process.”2 The DRN provides several tools to help applicants research prospective training programs, including reputation rankings for residency programs across multiple specialties, resident and alumni satisfaction surveys, and objective data (eg, training program size, board certification rate, sex balance, alumni publication data).

Previous studies have called into question the validity of Doximity reputation rankings of residency programs due to the lack of objective and outcome-based data used to formulate these rankings.3, 4 Nonetheless, previous studies using surveys have shown that Doximity reputation rankings influence applicants' behaviors when applying to and ranking residency programs.5, 6 To date, there are no large cohort studies evaluating the impact of DRN on medical students' residency selection across a wide distribution of GME programs. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to assess residency applicants' use and perceptions of DRN and to analyze the effect of Doximity reputation rankings on the application, interview acceptance, and match list rankings of applicants at a single sponsoring institution.

Participants and Methods

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and was conducted from March 1, 2017, through May 8, 2017. During the 2016-2017 NRMP Main Residency Match application period, the authors identified 12,617 applicants to 24 Mayo Clinic School of Graduate Medical Education (MCSGME) residency training programs. A survey was developed seeking feedback from applicants about their use of DRN during the residency application, interview selection, and match process. The survey was developed by 2 of us (B.B.S. and T.R.L.), with demographic questions modeled after a similar study of anesthesiology residency applicants.7 The survey was reviewed and edited independently by all study authors. For additional content validity, the survey was reviewed by the Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translations Science support staff, including 2 analysts and a statistician. The survey was piloted for content validity by administration to 15 current postgraduate year 1 residents with experience using Doximity across medical and surgical specialties at MCSGME. The edited survey was reviewed again by all the authors and then finalized (Supplemental Appendix, available online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org).

The survey included questions about demographic characteristics, type of medical school attended, specialty(s) applied to, number of residency program applications submitted, NRMP Main Residency Match results, applicant use and perception of DRN and Doximity reputation rankings, and other resources used to research residency programs. Applicants who did not use DRN were asked why they chose not to use the tool and then were asked what resources they did use to research residency programs during the application process. Additional space was provided for applicants to add comments where survey choices were not comprehensive (eg, specialty[s] applied, reasons not to use Doximity, other resources used to research residency programs).

The survey was distributed to all applicants to MCSGME programs participating in the NRMP Main Residency Match in April 2017. Weekly reminders were sent to nonresponders for 3 consecutive weeks. We used the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tool at Mayo Clinic for survey distribution.8 A 4-point Likert scale was used to score the DRN features that applicants found most valuable (very valuable, valuable, slightly valuable, not valuable) and to assess applicant views of the accuracy of Doximity reputation rankings (very accurate, accurate, slightly accurate, not accurate).

Data analysis consisted of descriptive statistics using REDCap. Comments were reviewed individually by a study author (B.B.S.), grouped according to common themes, and reported.

Results

During the study period, 12,617 applicants to MCSGME residency training programs participating in the NRMP Main Residency Match were identified. A total of 2152 applicants (17%) completed the survey and were included in the data analysis. Minor differences are present in the denominators of the data because not all survey respondents answered each question. Demographic data for residency applicants are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Residency Applicant Demographic Informationa

| Variable | Values |

|---|---|

| Sex (No. [%]) (n=2147) | |

| Male | 1258 (59) |

| Female | 889 (41) |

| Age (y) | |

| Mean ± SD | 28.5±4.1 |

| Median | 27 |

| Range | 19-58 |

| Medical school (No. [%]) (n=2152) | |

| US allopathic | 1261 (59) |

| International | 774 (36) |

| US osteopathic | 117 (5) |

| Specialty applied to (No. [%]) (n=2148) | |

| Internal medicine | 622 (29) |

| Surgery | 213 (10) |

| Family medicine | 202 (9) |

| Anesthesiology | 192 (9) |

| Pediatrics | 172 (8) |

| Neurology | 126 (6) |

| Emergency medicine | 115 (5) |

| Orthopedic surgery | 113 (5) |

| Radiology | 108 (5) |

| Psychiatry | 100 (5) |

| Pathology | 91 (4) |

| Obstetrics and gynecology | 75 (4) |

| Dermatology | 72 (3) |

| Otolaryngology | 65 (3) |

| Physical medicine and rehabilitation | 57 (3) |

| Neurologic surgery | 46 (2) |

| Radiation oncology | 41 (2) |

| Plastic surgery | 39 (2) |

| Ophthalmology | 22 (1) |

| Child neurology | 19 (<1) |

| Otherb | 19 (<1) |

| Medicine/pediatrics | 15 (<1) |

| Thoracic surgery | 15 (<1) |

| Vascular surgery | 10 (<1) |

| Urology | 9 (<1) |

| Preventive medicine | 2 (<1) |

| Medical genetics | 1 (<1) |

| Nuclear medicine | 1 (<1) |

| No. of residency programs applied to (No. [%]) (n=2142) | |

| ≥51 | 1258 (59) |

| 21-30 | 262 (12) |

| 31-40 | 233 (11) |

| 41-50 | 202 (9) |

| 11-20 | 141 (7) |

| 1-10 | 46 (2) |

| Successful 2016-2017 NRMP match (No. [%]) (n=2027) | |

| Yes | 1722 (85) |

| No | 305 (15) |

NRMP = National Resident Matching Program.

Other specialties included pediatrics/psychiatry, interventional radiology, and transitional year.

The use of DRN by residency applicants is outlined in Table 2. Of the 2152 applicants who completed the survey, 1339 (62%) actively used DRN during the application, residency interview, and match list process. Of the 1335 applicants who used DRN and answered the question, 1157 (87%) used the tool before sending out applications, 906 (68%) used it during the interview process, and 686 (51%) used it while creating their rank order lists. Of the 1186 applicants who matched into a GME training program, only 314 (26%) believed that the use of DRN helped them match successfully.

Table 2.

Doximity Residency Navigator (DRN) Use by Applicants

| Variable | Applicants (No. [%]) |

|---|---|

| DRN use during residency application/interview/match (n=2150) | |

| Yes | 1339 (62) |

| No | 811 (38) |

| When did you access DRN? (n=1335) | |

| Before sending out applications | 1157 (87) |

| During the interview process | 906 (68) |

| While making rank order list | 686 (51) |

| Do you believe DRN helped you match successfully? (n=1186) | |

| Yes | 314 (26) |

| No | 872 (74) |

| Did DRN expand your geographic options of residency programs? (n=1185) | |

| Yes | 577 (49) |

| No | 608 (51) |

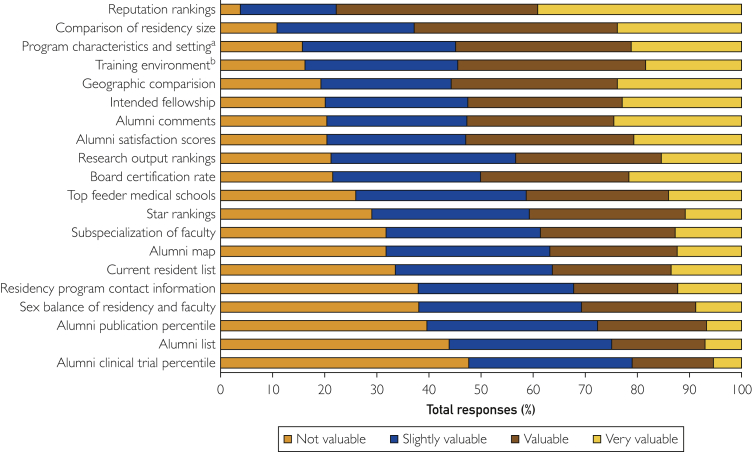

Resources available in DRN identified by applicants as very valuable, valuable, slightly valuable, and not valuable to their research of residency programs are listed in the Figure. The most valuable resource in DRN was the reputation ranking, which was noted to be valuable or very valuable to 958 of 1233 applicants (78%). Data analyzing the influence of Doximity reputation rankings on an applicant's application, interview acceptance, and match list rankings are outlined in Table 3. Overall, 977 of 1241 applicants (79%) reported that Doximity reputation rankings influenced their application, interview acceptance, or match list ranking decisions. Despite this, 699 of 1240 applicants (56%) believed that the rankings were not accurate or only slightly accurate.

Figure.

Features of Doximity Residency Navigator least and most valuable to applicants. aLarge public hospital, Veterans Affairs hospital, pediatric hospital, or American Osteopathic Association dual-accredited training program. bRural or urban setting.

Table 3.

Impact of Doximity Reputation Rankings on Applicant Residency Decisions

| Variable | Applicants (No. [%]) |

|---|---|

| Did Doximity reputation rankings influence application to residencies? (n=1241) | |

| Yes | 742 (60) |

| No | 499 (40) |

| Did Doximity reputation rankings influence acceptance or rejection of interviews? (n=1241) | |

| Yes | 499 (40) |

| No | 742 (60) |

| Did Doximity reputation rankings influence match rankings? (n=1239) | |

| Yes | 605 (49) |

| No | 634 (51) |

| How accurate do you believe that the Doximity reputation rankings are? (n=1240) | |

| Very accurate | 46 (4) |

| Accurate | 495 (40) |

| Slightly accurate | 615 (50) |

| Not accurate | 84 (7) |

Of the 811 applicants (38%) who reported that they did not use DRN during the residency application process, 621 (77%) were unaware of DRN and 130 (16%) did not find the information useful to their residency application. Applicants who chose not to use DRN commented that the content in DRN and the reputation rankings seemed “unreliable, biased, subjective,” with questionable validity.

Other resources used by applicants to research residency programs are listed in Table 4. The most frequently used resources were residency program websites (1676 of 2014, 83%), American Medical Association resources (1389 of 2014, 69%), DRN (1339 of 2150, 62%), Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) resources (1012 of 2014, 50%), and NRMP resources (1010 of 2014, 50%).

Table 4.

Resources Used by Applicants to Research Residency Programsa

| Resource | Applicants (No. [%]) |

|---|---|

| Residency program websites (n=2014) | 1676 (83) |

| AMA resourcesb (n=2014) | 1389 (69) |

| Doximity Residency Navigator (n=2150) | 1339 (62) |

| AAMC (n=2014) | 1012 (50) |

| NRMP (n=2014) | 1010 (50) |

| Student Doctor Network (n=2014) | 849 (42) |

| Other online or print resources (n=2014) | 236 (12%) |

| Social media (n=2014) | 201 (10) |

| Medscape (n=2014) | 85 (4) |

AAMC = Association of American Medical Colleges; AMA = American Medical Association; FREIDA = Fellowship and Residency Electronic Interactive Database; NRMP = National Resident Matching Program.

FREIDA Online, the AMA Residency & Fellowship Database.

Discussion

Most applicants (1339 of 2150; 62%) applying to GME programs at our institution who completed the survey used DRN during the application, interview, and match ranking process. Doximity reputation rankings were found to be the most valuable resource in DRN by the applicants. Of 1241 applicants who reviewed Doximity reputation rankings, 977 (79%) reported that the rankings influenced their application, interview acceptance, or match list rankings of residency programs. Despite the significant impact of Doximity reputation rankings, 699 of 1240 applicants (56%) believed that the reputation rankings were not accurate or were only slightly accurate. Furthermore, only 314 of 1186 applicants (27%) believed that DRN helped them match successfully during the NRMP 2017 Main Residency Match.

Identifying tools that accurately assess residency programs before applying to and interviewing is important for applicants to GME programs. The NRMP 2017 Main Residency Match was highly competitive, with 43,157 applicants vying for 31,757 residency positions.9 In response to the competitive nature of the match, applicants are applying to and interviewing at an increasing number of residency programs to improve their chances of matching.10, 11 Application and interview expenses, as well as the time required to interview, at an increasing number of programs can be prohibitive to prospective residents. For example, a 2015 survey by the AAMC reported that during the application and interview process, mean ± SD expenses were $3422±$2853 per applicant (range, $80-$25,000).12 With limited financial resources and restricted time for interview travel, it is becoming increasingly important for applicants to have valid tools to research residency programs.

As stated by Doximity, Inc, DRN is a tool to help applicants “make informed residency decisions and to increase transparency in the residency match process.”2 The use of DRN by applicants has become more prevalent since its release in 2014. The present study shows that of the 811 applicants (38%) who did not use DRN, 621 (77%) were unaware of its existence. This demonstrates the possibility that increased awareness may result in a dramatic increase in utilization by residency program applicants. Doximity compiles objective data from a variety of public sources, conducts annual satisfaction surveys, and partners with residency programs to ensure individual residency program data in DRN is accurate and current. Doximity reputation rankings are derived from surveys sent to board-certified physicians and modeled after the annual physician survey from which U.S. News & World Report's Best Hospitals rankings are calculated.2 Previous studies have called into question the validity of the Doximity reputation rankings due to the lack of objective and outcome-based data used to formulate these rankings.3, 4, 5, 6 Consistent with previous studies,5, 6 the present study found that applicants question the accuracy of Doximity reputation rankings. Despite this apprehension, the present study indicated that Doximity reputation rankings influence the application, interview choice, and match list rankings of applicants, suggesting that applicants will use whatever information is available to evaluate residency programs.

Ongoing dialogue among applicants, medical schools, accreditation bodies, match organizations, program directors, and other parties, such as Doximity, Inc, to provide comprehensive information about residency programs to those seeking GME training is essential to improving the current application, interview, and match process. This is critical because the number of applicants seeking GME positions will increase due to medical school expansion.13 Individual residency programs should monitor their respective program websites and DRN, in addition to American Medical Association, AAMC, and NRMP resources, for accurate content because these resources are frequently used by applicants to research programs. Going forward, it is in the best interests of GME programs and prospective applicants for Doximity and sponsoring institution leadership to work together to ensure that valid metrics are collected and accurately reported in the DRN.

The low response rate in the present survey (2152 of 12,617 applicants [17%]) is a limitation of this study. Despite the low response rate, this is the largest multispecialty survey examining the use of DRN available in the literature. In addition, because the survey was distributed after the NRMP 2017 Main Residency Match, recall bias may have influenced the results as applicants may have been unable to determine the influence of DRN and Doximity reputation rankings on their application, interview, and match decisions. A large, multicenter, multispecialty study (possibly as a component of the NRMP applicant survey) is needed to further analyze the influence of DRN on applicants' decisions during the NRMP season.

Conclusion

Most survey responders used DRN during the application, interview, and match ranking process. Doximity reputation rankings were found to be the most valuable resource in DRN, and most applicants reported that the rankings influenced their application, interview acceptance, or match list rankings of residency programs. Despite this, more than 50% of respondents had doubts about the accuracy of Doximity reputation rankings. Given the availability and increasing utilization of social networking applications such as DRN, program directors and administrators at institutions that sponsor GME will need to develop strategies to ensure accuracy of content and how to best use these platforms to attract the best applicants.

Footnotes

Grant Support: This project was supported by grant UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Potential Competing Interests: Dr Tooley received paid support for travel and YouTube videos from Doximity, Inc. The rest of the authors report no competing interests.

Supplemental Online Material

Supplemental material can be found online at http://www.mcpiqojournal.org. Supplemental material attached to journal articles has not been edited, and the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of all data.

References

- 1.National Resident Matching Program, Data Release and Research Committee . National Resident Matching Program; Washington, DC: 2015. Results of the 2015 NRMP Applicant Survey by Preferred Specialty and Applicant Type. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doximity Residency Navigator. https://s3.amazonaws.com/s3.doximity.com/mediakit/Doximity_Residency_Navigator_Survey_Methodology.pdf Updated June 2017. Accessed August 12, 2017.

- 3.Wilson A.B., Torbeck L.J., Dunnington G.L. Ranking surgical residency programs: reputation survey or outcomes measures? J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e243–e250. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashack K.A., Burton K.A., Dellavalle R.P. Dermatology in Doximity. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22(2) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rolston A.M., Hartley S.E., Khandelwal S., et al. Effect of Doximity residency rankings on residency applicants' program choices. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(6):889–893. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.8.27343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson W.J., Hopson L.R., Khandelwal S., et al. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(3):350–354. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.4.29750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dodd S.A., Licatino L.K., Rose S.H., Long T.R. Factors important to anesthesiology residency applicants during recruitment. J Educ Perioper Med. 2017 XIX(II) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris P.A., Taylor R., Thielke R., Payne J., Gonzalez N., Conde J.G. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Resident Matching Program . National Resident Matching Program; Washington, DC: 2017. Results and Data: 2017 Main Residency Match®. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Putnam-Pite D. Viewpoint from a former medical student/now intern playing the game: balancing numbers and intangibles in the orthopedic surgery match. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):311–313. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00236.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berger J.S., Cioletti A. Viewpoint from 2 graduate medical education deans application overload in the residency match process. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):317–321. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00239.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried J.G. Association of American Medical Colleges; Washington, DC: May 2015. Cost of Applying to Residency Questionnaire Report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iglehart J.K. The residency mismatch. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(4):297–299. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1306445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.