Abstract

Right Dislocation (RD) has been suggested to be a focus marking device carrying an affective function motivated by limited planning time in conversation. The current study investigated the effects of genre type, planning load and affect on the use of RD in Cantonese monologues.

Discourse data were extracted from a recently developed corpus of oral narratives in Cantonese Chinese containing language samples from 144 native Cantonese speakers evenly distributed in age, education levels and gender. Three genre types representing different structures, styles and degrees of topic familiarity were chosen for an RD analysis: procedural description, story-telling and recount of personal event.

The results revealed that genre types and planning load influenced the rate of RD occurrence. 1) Specifically, the lowest proportion of RD occurred in procedural description, assumed to be the most structured genre; whereas the highest rate was found in personal event recount, considered to be the most stylized and less structured genre. 2) The highest proportion of RD appeared near the end of a narrative, where heavier cognitive load is demanded compared to the beginning of a narrative; moreover, RD also tended to co-occur with disfluency. 3) There was a high percentage of RD tokens in the personal event recount for expressing explicit emotions; and 4) a lower rate of occurrence of RD was found in monologues than previous studies based on conversations. The overall findings suggest that the use of RD is sensitive to genre structure and style, as well as planning load effects.

Keywords: Focus fronting, genre, planning load, Cantonese, Discourse

1. Introduction

Right dislocation (RD) refers to a sentence construction in which some syntactic components are dislocated from the sentence beginning or internal position to the end of the sentence. Chinese is known for its flexibility in terms of the syntactic categories of dislocated elements, which may include nouns, verbs, adverbs, connectives, modals and adverbial clauses (Cheung, 1997; Guo, 1999; Luke, 2012), Some examples of Cantonese RD are given below:

-

(1)

唔 拎 把 遮 喇 , 我

Not bring CL umbrella sfp , I

“I am not bringing the umbrella”

-

(2)

我 唔 拎 喇 , 把 遮

I not bring sfp , CL umbrella

“I am not bringing the umbrella”

In (1), the referent 我 “I” is the subject of the sentence which is usually placed in a clause initial position in canonical word order, but it is dislocated to the sentence final position after the sentence final particle (SFP). (2) is an example of object dislocation, where the object referent “umbrella” is dislocated to the right-most position after the SFP.

RD is regarded as a grammatical phenomenon that is “one of the most intriguing and least well understood in Chinese grammar (Luke, 2012, p.339)”. The complex nature of RD is also reflected in its terminology. It was initially proposed by Chao (1968) as “afterthought”, referring to the unplanned content that was added to a completed sentence. Packard (1986) has argued that it is actually a “left dislocation” in which the focus information in the sentence has undergone a leftward movement to the sentence initial position (also see Cheung, 2009). Other terms for this construction include “transposition” (Lu, 1980), “dislocation” (Liang, 2002), “focus-fronting” (Luke & Zhang, 2007; Zhang & Fang, 1996), and “incremental sentences” (Luke, 2004; 2012).

The literature on Cantonese RD has mainly focused on its syntactic and grammatical constraints. Cheung (1997, 2005) examined the syntactic characteristics of RD, and found that the main sentence and the dislocated constituent were strongly governed by grammatical principles. Law (2003) argued that RD involves leftward movement of a constituent to the focus field. The movement is subjected to island constraints. An alternative approach takes the functional perspective which is concerned with the functions and motivations of RD, almost exclusively in conversational discourse. Research to date has generally lent support to the claim that RD is a focus marking device motivated by limited time pressure in conversation (Liang, 2002; Zhang & Fang, 1996).

Zhang and Fang (1996) proposed that due to the lack of planning time, speakers in conversational discourse tend to place the most important information (i.e. the focus) in the initial position of a sentence, and then fill in the less important information at the end. Thus, the proposal suggested that RD mainly occurred in conversation. Liang (2002) is one of the most detailed studies of RD in Cantonese Chinese. In her study, 99% of the 600 instances of RD identified were from conversations. Liang (2002) agreed with Zhang and Fang (1996) that lacking planning time in conversation is the main reason for using RD. However, Liang’s conclusion seems premature since her data were predominantly drawn from conversations. It is not clear whether other discourse types, such as narratives or sequential descriptions may also contain RD. If the lack of planning time is the primary reason for using RD, the occurrence of this structure should be minimal in monologues with familiar topics. In order to understand the motivation behind RD, a greater variety of discourse types other than conversation should be studied.

Guo (1999) examined the use of RD in discourse produced by children at play. It was observed that RD often served an affective function to focus the addressee’s attention and convey the speaker’s negative feelings. By analyzing the dislocated noun phrase, three main types of RD were classified: (i) zero anaphoric, (ii) elaborations, and (iii) reduplications. The zero anaphoric and elaborative types of RD are found to be mainly used for statement purpose, while reduplications mainly serve the functions of questions, ridicules and reprimands. Based on these findings, Guo argued that RD in Mandarin Chinese carries an emphatic function to express the speaker’s focus of attention. It was further hypothesized that RD was originally a form of afterthought used as a repair device in spoken language and then became grammaticalized for managing information. Subsequently, it took up the emphatic function to express the speaker’s negative attitude.

Luke (2012) used the term “incremental sentence” to highlight the incremental nature of RD. He suggested that RD production is a real time process in which some items are added to the end of a sentence. A conversation analytic account was adopted in Luke to analyze RD (or incremental sentences). By examining naturally occurring conversational data, Luke concluded that RD performed a variety of functions, including intensification, emphasis, backgrounding, qualification, clarification, and disambiguation. An example of intensification (p.350) is cited here:

-

(3)

佢 而家 真係 勁 呀 , 佢 而家

He now really great SFP , He now

“He’s really great now, he is”

The third person pronoun “he” is repeated, together with the time phrase “now”. Luke claimed this repetition gave the utterance a particularly animated and emphatic character. The intensification effect was achieved through repetition. Supplementing background information is another major function of RD (Luke, 2012). Luke observed that the dislocated slot was often used for providing background or secondary information. In a conversation, before a speaker ends a turn, RD provides the last opportunity for secondary information to be introduced. The functions of revision and disambiguation appeared to operate in a similar manner in conversation. Specifically, the function of revision could “supply additional information in order to revise or clarify a reference or to avoid potential misunderstanding” (p.355) and the function of disambiguation could “add detail to a reference made in the main part of the sentence for the purpose of clarification or disambiguation” (p.358). Although some of the functions described in Luke may not be highly distinctive, the discussion has provided important insights showing that the discourse context does influence the use of RD. Hence, it is important to investigate RD with consideration of the context in which they are uttered.

The influence of speech context on language performance is widely observed. Studies have shown that genre types and topic familiarity have significant impact on language performance in terms of fluency, complexity and accuracy (Foster & Skehan, 1996; Skehan & Foster, 1997, 1999). Three genre types were used in Skehan and Foster (1999): personal, narrative and decision-making tasks. The personal task involved the participant sending a friend back home to turn off an oven. The speaker needed to explain to a friend how to get to the house, then to the kitchen and how to turn off the oven. The information of this personal task was familiar to the speaker and assumed to reduce the cognitive load of the task. The narrative task required the speaker to retell a story based on a cartoon strip with a clear beginning, development, and conclusion. The decision-making task was more interactive and required the speaker to relate a set of moral values in order to reach a decision. It was reported that production in the personal task exhibited less complexity than the narrative and decision-making tasks. The decision-making task solicited the most complex language, while the personal and narrative tasks showed the greatest level of fluency. The speech in the personal task also demonstrated the highest degree of accuracy, and when planning time was allowed, accuracy exhibited a marked increase in the narrative task. The results showed that both topic familiarity and genre structure influenced performance. The personal task was the most familiar to the speaker and thus least cognitively demanding. The speaker could pay greater attention to language form, resulting in greater fluency. The narrative task contained clear inherent structure with visual aids; therefore, the output in this task was also fluent. The findings also revealed that planning time enhanced accuracy in the narrative and decision-making genres, supposedly through reducing the processing load in these two tasks. Previous studies have thus established that language performance is affected by genre type or discourse structure, topic familiarity and planning time. Although RD has been suggested to serve the functions of focus marking, repair and clarification in conversation (Luke, 2012), the impact of genre type on its use has not been investigated. One of the purposes of this study is to examine the interaction between genre types and the use of RD, in particular, whether genres with different styles and degrees of familiarity would elicit different rates of RD.

Our review of the literature has reflected the current understanding of how RD is motivated in conversations. Conclusions from these reports were, however, limited in terms of the size of dataset and methodologies. Drawing on a larger data set, this study has employed quantitative analyses to investigate a mode of communication that has been far less studied, that is, monologue, in light of the previously proposed hypotheses concerning genre type, planning load pressure, and affective function. Three types of narratives were chosen for examination–procedural description, story-telling, and recount of personal experience. These genre types represent different properties in terms of structure, style and degree of familiarity. The planning load is assumed to be the lightest when a topic is more familiar and there is more shared knowledge between the speaker and listener. According to Foster and Skehan (1996), the cognitive demand in the genre of procedural description should be the minimum since it contains an inherent sequential task structure. Recounting a personal experience would be expected to be the most cognitively demanding since its structure is more dynamic and stylized. The speaker has to organize the content and introduce entities spontaneously as the discourse unfolds. The planning pressure of telling well-known stories is expected to be in between. The content is familiar and stories in general are well-structured although speakers might pay some attention to plan the introduction of entities in the discourse. If the hypothesis of Zhang and Fang (1996) about the pressure of planning time (or load) as a key factor of the occurrence of RD in conversation is correct, RD is predicted to appear more frequently in a discourse with high planning pressure, that is, the recount of personal event. Moreover, more RD would be produced later in the course of narration since the early part of a narrative would usually be better planned given the pre-task preparation time. Obtaining the frequency and position of occurrence of RD in production of these genres would enable us to understand whether genre type and planning load pressure play a role in using RD in spoken Cantonese.

Finally, to assess the hypothesis about the affective function of RD, we compared the relative frequencies of RD tokens with explicit emotional expressions with those without.

2. Methods

The data of this study were drawn from a spoken Cantonese corpus of oral narratives (CANON) (Kong, Law, & Lee, 2010–14).

2.1. Participants

CANON is composed of language samples from neurologically unimpaired native Cantonese speakers. The participants consisted of 12 sub-groups classified by gender (male and female), age (18–39 years old, 40–59 years old, and above 60), and education level (higher or lower than secondary school for the two younger groups; and higher or low than primary school for the oldest group). Each sub-group contained 12 participants. Altogether there were 144 participants balanced in gender, age and education level in the corpus.

2.2. Procedures of data collection and analyses

A face-to-face interview was conducted for each participant. Connected speech samples were elicited by means of four narrative tasks, including descriptions of picture stimuli, procedural descriptions, story-telling, and recount of a personally important event. During the interview, the examiner’s input was kept to a minimum. At the time of data collection, the participants’ speech was videotaped and audio-taped. All language samples were orthographically transcribed. Inter-rater reliability of orthographic transcription was computed by randomly selecting 10% of the samples and double-checked against the audio recordings by two native speakers, and was found to have an agreement of greater than 99%.

2.2.1. Identification of instances of RD

The present study followed criteria for identifying dislocation mentioned in Cheung (1997) and Liang (2002). Structurally, dislocation takes the form of [α (SFP), β], where α and β refer to components of a clause. If there was a sentence final particle (SFP), it must appear between the α and β strings. SFP is not obligatory although it is commonly found in RD (Liang, 2002). Semantically, the β string should be able to form a complete clause with the α string when the clause is in a canonical word order. Phonetically, there is no noticeable pause between the main clause and the dislocated element, and the dislocated element is always said in a fast tempo (Liang, 2002). An example is provided in (4). The subject “this kid” should appear before the verb “play” when it is in the canonical word order.

-

(4)

玩 之嘛 , 哩 個 小朋友

Play SFP , this CL kid

“He’s just kidding, this kid”

2.2.2. Genre types effect

Language samples from three genres were analyzed with respect to the frequency of RD. They were (i) procedural description of making an egg-and-ham sandwich, (ii) story-telling–The Hare and the Tortoise and The Boy who Cried Wolf, and (iii) recount of a personally important event. These genres mainly varied in the constraint on structure and degree of familiarity of content. For instance, procedural description involved a sequence of steps in making a sandwich. Its structure was rather fixed. The referents of egg, ham and bread were familiar information to both the speaker and listener since the picture of these objects remained in sight during narration. In the story-telling task, the storylines were presented in the story cards; the content was familiar to the participant and the interviewer. Nonetheless, this task required more attention to story development and might involve greater variety in individual style than the procedural description. The genre of personal event recount was supposed to be most varied and stylized in terms of content and structure. Entities in this task were assumed to be new information in the discourse since the interviewer (listener) did not know what a speaker would say about his/her personal experience.

The frequencies of occurrence of RD across genre types, the rate of occurrence of each narrative sample were calculated. Non-parametric tests were used for statistical analyses as the Shapiro-Wilk test revealed that the distributions of frequency of occurrence failed to meet the normality assumption. The Kruskal-Wallis H test was performed to determine if the different genre types had an effect on the rate of usage of RD. Post-hoc analyses using Mann-Whitney U test were conducted for pairwise comparisons in case of a significant difference.

2.2.3. Planning load effect

In order to test whether the use of RD was triggered by pressure of speech planning load, the position of occurrence of RD over the course of a narrative was analyzed. Given the preparation time prior to a task, speech at the beginning of a narrative would have lower planning load pressure than speech occurring towards the end of the narrative; thus, an increase in the probability of RD would be expected over the course of the discourse. Each narrative was segmented evenly into three sections—beginning, middle and final—according to its number of utterances. The Chi-square goodness-of-fit test was employed to determine whether the occurrences of RD were evenly distributed across the three segments.

2.2.4. Effect of affective function

To clarify whether the use of RD was associated with expressions of emotion, each RD token was examined for explicit emotional words, such as “sad”, “happy”, and “unforgettable” etc. The Chi-square goodness-of-fit test was applied to evaluate if the association between RD and emotional expressions was statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 117 instances of RD were identified. They were produced by 63 speakers. In other words, more than half of the participants did not use any RD in any of the narrative tasks. The 63 speakers seemed to be distributed evenly across age groups and education levels. Young female speakers with low education level tended to use RD rarely.

3.1. Genre effect

The distribution of RD across genre types is shown in Table 1 With reference to the number of utterance, the rate of RD was lowest in the procedural description task (1.4 per 100 utterances) followed by story-telling (2.1), which in turn had a lower RD rate than personal recount (3.2)

Table 1.

Distribution of RD in Genres

| No. of RD used | Total no. of utterance |

RD token per 100 utterance |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural Description | 10 | 692 | 1.4 |

| Story-telling | 52 | 2478 | 2.1 |

| Personal Recount | 56 | 1747 | 3.2 |

The Kruskal-Wallis test showed that the rates of RD occurrence were significantly different across the genres, H (2) = 7.7, p < .05, with an effect size of 0.8. Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted with Bonferroni correction (p = .05/3 = .0167) to investigate which two genres were different from each other. RD was produced significantly less frequently in procedural description than in personal recount (U = 108, z = −2.26, p = .014), and in story-telling (U = 97, z = −2.88, p = .004).There was no reliable difference between story-telling and personal recount (U = 541, z = −2.00, p = .045).

3.2. Planning load effect

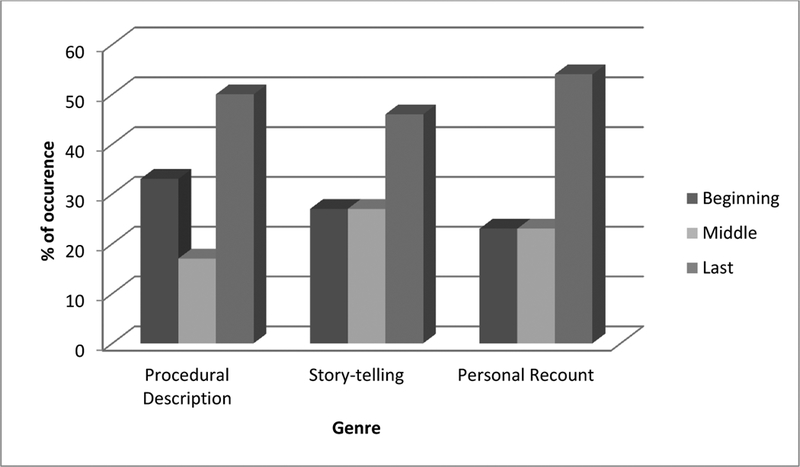

Regarding the position in which RD tended to occur within a narrative, all three genres showed the same tendency with the majority of RD appearing near the end of the narrative (see Figure 1). The remaining instances distributed fairly evenly in the beginning and middle of the narrative. The bias in distribution was confirmed by the Chi-square goodness-of-fit test when the three genres were combined (χ2 (2) = 6.29, p < .05).

Figure 1.

Position of occurrence of RD in different genres

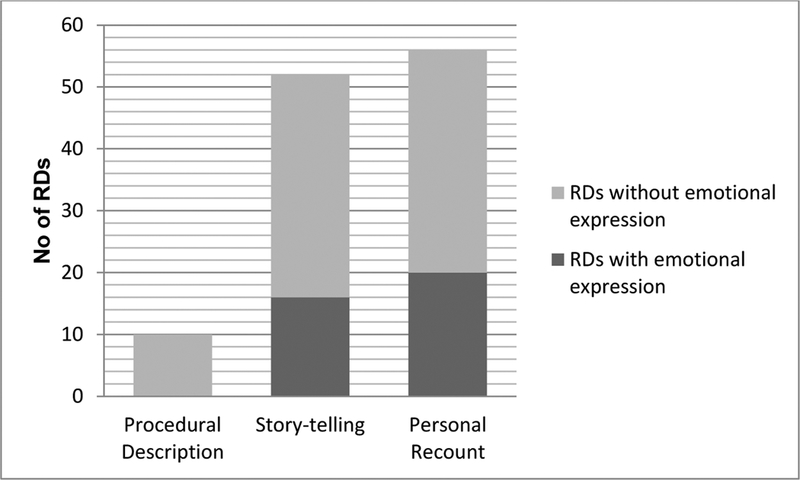

3.3. Affective effect

In procedural description task, no RD was found to contain any emotional word. In story-telling, 31% of the RD involve explicit emotion expressions; while 28.5% of the construction in the personal recount genre carried explicit emotional words. The Chi-square goodness-of-fit test revealed that the co-occurrence of RD and emotion word was not significantly above chance. There was no association between the use of RD and emotional expression in either story-telling: χ2 (1) = 0.07, p > .05, or personal recount: χ2 (1) = 0.18, p > .05. The frequencies of RD carrying emotional expressions in different genres are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of RD with emotional expression in different genres

4. Discussion

The results showed that genre types and planning load played a role in the use of RD in Cantonese. The highest rate of RD was found in the most stylized genre, that is, personal event recount. In contrast, RD occurred most infrequently in the procedural description, which was the most structured genre. Hence, our study has shown that genre containing inherent structure elicits fewer RD. As Foster and Skehan (1996, 1997) suggested, in language tasks with essentially a sequential structure, the speaker could pay more attention to the linguistic form rather than the presentation of the content. In this sense, the speaker may not need to use RD frequently as an afterthought or repair device.

Moreover, the majority of RD were produced in the later course of narration for all three genres; the finding is consistent with the planning load hypothesis. Preparation time prior to narration may be a cause for this pattern. Mehnert (1998) studied the effects of planning time on second language performance and found that advanced speech planning is an effective way to reduce the amount of online speech planning needed, and thus eases the burden of communicative load and processing pressure. Language performance generally improved, with pre-task planning time, in terms of sentence complexity and accuracy. Under the planned condition, speech was more fluent as reflected by shorter pauses or self-correction. Beattie (1983) investigated speech planning and discovered that the general semantic content of utterances would have been worked out first, while the detailed syntactic and semantic planning was carried out online. To apply these observations to the present finding, the utterances in the early part of a narrative would be well-planned given the pre-task preparation time. Subsequent utterances would only be planned while narrating. The pressure would also become higher from the dual tasks of planning and speaking, leading to a higher proportion of RD. A corroborating observation is that RD utterances in this corpus were often accompanied by repetition, retracing, and longer pauses, as illustrated in (5), an excerpt from the task “The boy who cried wolf”.

-

(5)

(i) 啲 農民 呢 聽 到 喎.

CL farmer SFP heard SFP

“The farmer heard (the boy shouting)”

(ii) 即刻 停 嗮 啲 嘢.

At once stop Quan CL thing

“They stopped everything at once”

(iii) 停 嗮 唔 做 耕田.

Stop Quan not do farming

“They stopped farming”

(iv) gam2aa6 攞 嗮 鋤頭 呀 盛

Take Quan hoe SFP

“They took the hoes etc.”

(v) 即刻 趕 上 山.

Immediately rush up hill

“They rushed up the hill immediately”

(vi) 就 去 [/] 去 打 [/] 打 走 啲 [/] 啲 狼 啦 , 想 話.

Then go go hit hit away CL CL wolf SFP , intend

“They intended to go and drive the wolves away”

(5) is an example of co-occurrence of RD and self-correction. In line (vi), the speaker corrected her speech by making several repetitions, including the verbs “go”, “hit”, and classifier “some”. The dislocated part is the main verb “intend”. Dislocation of verb does not usually occur in English. The dislocated verb served the function of adding supplementary information to the utterance. It seems that the idea of “driving the wolves away” was in the speaker’s mind, but the semantic and syntactic units were not fully planned, as evidenced by the repetitions. While uttering the sentence, the speaker might realize that “chasing the wolves away” was not entirely correct because there was actually no wolf (it was a lie told by the shepherd boy). The verb “intend” after the main clause would make the action become the intention of the farmer - a depiction that fitted the storyline better. In this example, it was unlikely that the speaker deliberately dislocated any constituents for highlighting; it might instead be the result of pressure under time and communicative constraints. The co-occurrence of disfluency and RD in relation to planning pressure merits further investigation.

Regarding the affective function of RD proposed by Guo (1999), the hypothesis did not seem to be supported by our data. Nonetheless, a certain proportion of RD was accompanied by emotional expressions in personal recount and story-telling, compared with its absence in procedural description. This contrast is probably due to the fact that in recounting personal experience and telling stories, it is very common for the speakers to express or share their feelings and evaluations. In addition, the present data have revealed that when RD co-occurs with an emotive word, different kinds of emotions can be expressed, positive as well as negative.

In comparison with previous studies involving conversations, a lower rate of occurrence of RD was observed in our corpus of monologues. More specifically, in 25 conversations and one story-telling totaling about 5.5 hours, Liang (2002) identified 666 instances of RD. Luke (2012) analyzed a sample of four hours of conversations and collected about 300 occurrences. In the present study, approximately 8 hours of recordings was examined, but only 117 instances were found. We suggest that the much higher rate of RD in conversation might partly be due to turn-taking, that is, to indicate the next turn to the addressee. Consider the following excerpt taken from Luke (2012, p.346):

-

(6)

Ian: … 啲 天氣 好似 琴日 噉 囉

CL weather like yesterday stprt SFP

“…the weather is like yesterday”

Joe: 有 冇check 過 呀, 你?

Have not check Asp SFP , you ?

“Have you checked?”

Luke argued that the dislocated “you” carried little value in terms of information load. It was more like a term of address than a pronoun. Its existence is to indicate to the addressee for the next turn-taking in the conversation. Luke (2000) reported that 78% of the RD utterances in his data either co-occurred or was directly followed by a turn-transition. RD in turn-taking was also claimed to be a “post-completion device” (p.307). The speaker attempts to extend his/her turn of speaking by supplementing more information upon completion of the utterance. If turn-taking is one of the main motivations in using RD, the absence of turn-taking in monologues may account for its lower rate of occurrence.

5. Conclusion

The current study has taken a functional and quantitative approach to investigate RD in Cantonese with consideration of different monologue types. Our findings are consistent with the view that the use of RD is sensitive to genre structure as well as planning load pressure. The co-occurrence of RD with disfluency is worthy of further investigation.

Funding acknowledgement

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health to Anthony Pak-Hin Kong (PI) and Sam-Po Law (Co-I) [project number R01DC010398–04].

Footnotes

References

- Beattie G (1983). Talk: An analysis of speech and non-verbal behaviour in conversation. Milton Keynes, U.K.: Open University Press [Google Scholar]

- Chao YR (1968). A grammar of spoken Chinese. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YL (1997). A study of right dislocation in Cantonese. Unpublished M.Phil. thesis, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung YL (2009). Dislocation focus construction in Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 18, 197–232. [Google Scholar]

- Foster P, & Skehan P (1996). The influence of planning and task type on second language performance. Studies in Second language acquisition, 18(03), 299–323. [Google Scholar]

- Guo J (1999). From information to emotion: The affective function of right-dislocation in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Pragmatics, 31(9), 1103–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Kong APH, Law SP, & Lee ASY (2010-2014). Cantonese Corpus of Oral Narratives (CANON: ). [Google Scholar]

- Law A (2003). Right dislocation in Cantonese as a focus-marking device. UCL Working Papers in Linguistics, 15, 243–275. [Google Scholar]

- Liang Y (2002). Dislocation in Cantonese: Sentence form, information structure, and discourse function Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

- Lu J (1980). 漢語口語句法裡的易位現象[The phenomenon of inversion (of sentence parts) in syntax of spoken Chinese]. Zhongguo yuwen (Chinese Language and Writing), 154, 28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Luke KK (2004). 說延伸句 [On incremental sentences] In Editorial board of Zhongguo yuwen (Chinese Language and Writing), Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (Ed.), Academic papers for celebrating the 50th anniversary of ‘Zhongguo yuwen (Chinese Language and Writing), (pp. 39–48). Beijing: The Commercial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luke KK (2012). Dislocation or Afterthought?—A Conversation Analytic Account of Incremental Sentences in Chinese. Discourse Processes, 49(3–4), 338–365. [Google Scholar]

- Luke KK, & Zhang W (2007). Retrospective turn continuations in Mandarin Chinese conversation. Pragmatics: quarterly publication of the International Pragmatics Association, 17(4), 605–636. [Google Scholar]

- Mehnert U (1998). The effects of different lengths of time for planning on second language performance. Studies in second language acquisition, 20(1), 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Packard JL (1986). A left-dislocation analysis of ‘afterthought’ sentences in Peking Mandarin. Journal of the Chinese Language Teachers Association, 21(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P, & Foster P (1997). Task type and task processing conditions as influences on foreign language performance. Language teaching research, 1(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Skehan P, & Foster P (1999). The influence of task structure and processing conditions on narrative retellings. Language learning, 49(1), 93–120 [Google Scholar]

- Swets. B, Jacovina ME & Gerrig, RJ (2013). Effects of Conversational Pressures on Speech Planning. Discourse Processes, 50 (1), 23–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B & Fang M (1996). 《漢語功能語法研究》[Studies in Chinese Functional Grammar] Nanchang: Jiangxi Education Publishing House. [Google Scholar]