Abstract

The inability to produce sustainable lifestyle modifications (e.g., physical activity, healthy diet) remains a major barrier to reducing morbidity and mortality from prevalent, preventable conditions. The objective of this paper is to present a model that builds on and extends foundational theory and research to suggest novel approaches that may help to produce lasting behavior change. The model aims to integrate factors not typically examined together in order to elucidate potential processes underlying a shift from behavior initiation to long-term maintenance. The central premise of the Maintain IT model builds on approaches demonstrating that in-tact executive function (EF) is critical for health behavior initiation, for more complex behaviors beyond initiation, and in unsupportive environments and circumstances, but successful recruitment of EF is effortful and prone to error. Enduring changes are more likely if the underlying cognitive processes can become less effortful (nonconscious, automatic). The Maintain IT model posits that a centered identity transformation is one path leading to less effortful processing and facilitating successful recruitment of EF when necessary over the longterm, increasing the sustainability of health behavior change. A conceptual overview of the literature supporting the utility of this integrative model, future directions, and anticipated challenges are presented.

Keywords: health behavior, behavior maintenance, identity transformation, executive function, self-regulation, intervention

Producing sustainable lifestyle modifications remains a major barrier to reducing morbidity and mortality from prevalent and preventable conditions. The leading causes of disease burden in the modern world can be avoided, delayed, or managed through healthy lifestyle behavior changes (Kontis et al., 2014; Reiner, Niermann, Jekauc, & Woll, 2013; Yoon et al., 2014). Serious efforts have been made by researchers to understand how to effectively encourage health-promoting behaviors and discourage health-risk behaviors (Michie et al., 2013, 2016); such efforts have been moderately successful at getting motivated individuals to adopt healthier behaviors for the short-term, but are largely unsuccessful at facilitating maintenance of these changes over time (Bryan et al., 2013; Marcus et al., 2000; Rothman et al., 2015). Sustaining behavior change is a critical challenge because most behaviors that decrease chronic disease risk require continued maintenance to achieve optimal health (e.g., weight loss; MacLean et al., 2015; Magkos et al., 2016).

Our objective is to present an integrative model that builds on and extends foundational theory and research from health, social, cognitive, clinical and positive psychology, and suggests novel and promising approaches to guide the development of interventions that produce lasting health behavior change. The model aims to integrate factors from existing perspectives not typically examined together that are important for behavior change and/or maintenance, and introduce centered Identity Transformation (IT) as one process that can lead to less effortful and more sustainable behavior change. Existing theories and approaches typically focus on behavior change or maintenance, but not both (with notable exceptions: e.g., the transtheoretical model, Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982; Rothman’s self-regulated behavior change model, Rothman, 2000; health action process approach, Schwarzer, Lippke, & Ziegelmann, 2008). Even these exceptions lack specific guidelines for successfully leading people from behavior initiation, where active self-regulation and/or self-control and increasing self-efficacy are primary, to a point where the health behaviors can be more consistently and reliably maintained.

The Maintain IT model utilizes a comprehensive approach to guide change in both the behavior and the individual to facilitate behavior adoption in an integrated way, and guide the identity of the individual to a more empowered and resilient state more broadly. The model recognizes the utility of existing behavior change frameworks, but substantively extends their reach by inspiring innovative research and intervention approaches. This model has the potential to enhance the likelihood of successful maintenance of health behaviors. The following sections will: (a) present the Maintain IT model within a conceptual overview, (b) describe principles of the Maintain IT model in practice, and (c) summarize challenges and future directions.

Maintain IT Model of Health Behavior Change and Maintenance: A Conceptual Overview

The central premise of the Maintain IT model (Figure 1) builds on more recent behavior change approaches which recognize that executive function (EF) is critical for deliberate, and specifically health related behavior (e.g., Hall & Fong, 2007; Hall & Fong, 2010; Hofmann, Schmeichel, & Baddeley, 2012). These approaches note that, because EF is relatively slow, effortful, and prone to errors, enduring changes in behavior are more likely if the underlying cognitive processes guiding behavior become more efficient and less effortful (that is, nonconscious, automatic, or habitual) and therefore rely less explicitly on EF. Maintain IT builds on and extends these well-known aspects of behavior change by suggesting processes and techniques that can facilitate relatively more automatic behavior overall, and increase the likelihood that EF can successfully be recruited when needed. Maintain IT was in part inspired by Kahneman’s cognitive processing view that distinguishes between System 1 (intuitive, fast, automatic, effortless, implicit, governed by habit) and System 2 (slow, effortful, controlled, deliberate, rule-governed) processes (Kahneman, 2003, 2011). Guided by prior research (Rothman, 2000; Rothman, Baldwin, Hertel, & Fuglestad, 2004), Maintain IT suggests that behavior that relies more on System 1 is more likely to be sustainable for the long-terms and notes the importance of increased automaticity for behavior maintenance. However, existing approaches do not specify how one might go about incorporating a behavior into System 1 processing, and instead implicitly rely on repeated performance to transition from initiation to automaticity. Repeating the behavior in a stable and predictable context, attaching the new behavior to an already established habit (Judah, Gardner, & Aunger, 2013), and creating an environment that either constructs the choice architecture to facilitate healthy defaults (Thaler, Sunstein, & Balz, 2010) or consistently has visible cues that promote healthy choices (Galla & Duckworth, 2015; Orbell & Verplanken, 2010) have proven successful for helping create automaticity to change behavior. But maintaining behavior change over the long-term creates difficulties for these techniques because maintenance often requires performing the behavior in a multitude of environments (including unsupportive ones), and under variable individual states that cannot always be controlled.

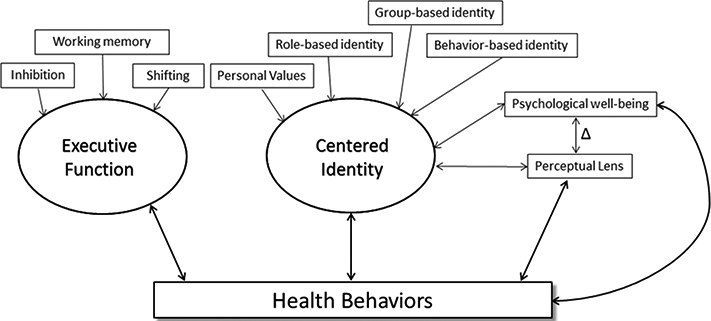

Figure 1.

Represents the components of the Maintain IT model, including the facets important for executive function and centered identity.

Further, although automatic behaviors are unquestionably more efficient; it may not be possible to make all, or even most, health behaviors completely automatized. Hall and Fong (2007) note that the extent to which a behavior will become automatic or habitual depends on the competing neural drives or impulses that influence the behavior. For example, restricting caloric intake frequently competes against an internal drive of hunger, and environmental cues of palatable, tempting, and rewarding foods that are often out of individual control. Thus, caloric restriction is a more difficult behavior to make automatic than behaviors such as flossing teeth or wearing a seatbelt, because there are generally no internal drives or environmental cues that directly oppose these behaviors. For some behaviors, interventions can emphasize creating automaticity (e.g., wearing a seatbelt), whereas other behaviors (e.g., healthy eating, caloric restriction, exercise) may require additional techniques to develop less effortful cognition, and/or increase the likelihood that effortful cognition can occur.

This premise is also consistent with dual systems and dual-process theories of mind. Both are increasingly utilized in health psychology (Hagger, 2016; Hagger & Chatzisarantis, 2014; Hofmann, Friese, & Wiers, 2008; Sheeran, Gollwitzer, & Bargh, 2013) because they provide a more comprehensive characterization of the conscious and non-conscious factors that influence behavior. These perspectives suggest that behavior is the result of the interplay between automatic and controlled processing, or between impulsive and reflective processes, rather than primarily driven by rational, goal-oriented cognition (Brannigan, Stevenson, & Francis, 2015; Smith & DeCoster, 2000; Strack & Deutsch, 2004). Individual differences in EF abilities, particularly working memory and attention, influence the extent to which individuals can control behavior by superseding automatic impulses and drives (Barrett, Tugade, & Engle, 2004).

Thus, a key contribution of Maintain IT is in noting that some level of active selfregulation will always be necessary for many health behaviors, and may be needed for all health behaviors during difficult environmental or individual circumstances (stress, opposing drives for unhealthy behaviors, lower inherent EF ability, etc.), and in certain physiological states (e.g., fatigue, anxiety, depression, intoxication). We propose the novel idea that a centered identity transformation and the connection of behavior to valued identities may present a way to scaffold existing behavior change approaches. This transformation aims to help create less reliance on EF for engaging in health behaviors globally and improve the likelihood that EF can successfully be recruited when needed.

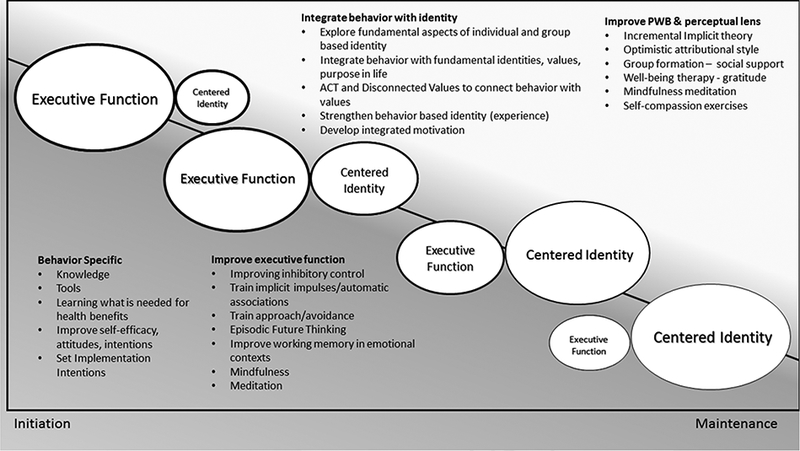

A centered identity transformation is one approach that can be harnessed for maintaining more complex behaviors, because it can allow more efficient processing to develop over time by integrating the behavior with identity. Further, a centered identity can increase the likelihood that successful recruitment of EF can occur by improving how empowered and resilient that identity is more broadly speaking (See Figure 2, which illustrates the relative importance of EF and identity along the continuum from behavior initiation to maintenance. Please note these are not distinct stages of behavior change nor is this necessarily a linear process). Centered identity transformation is a process through which a person develops self-representations that incorporate the new behavior, and reaches a more centered (i.e., empowered, resilient) state. This process first involves recruitment of EF, which is the foundation for deliberate conscious action, to facilitate the procedural learning of adaptive habits (Cohen & Squire, 1980; Mishkin, Malamut, & Bachevalier, 1984)—but further suggests a deliberate transformation of identity as an active approach to allow more efficient cognition to develop over time. This perspective contrasts with passive approaches that rely on successful repetition of a health behavior to lead to automaticity. Maintain IT suggests that interventions should move beyond the behavior, to help people work toward a more centered and empowered state more broadly, which can improve resilience in the face of inevitable obstacles, decrease the harmful effects of these challenges, and increase the likelihood likelihood that successful self-regulation can occur. Through a centered identity transformation, the new health behavior becomes integrated with fundamental roles and/or groups and values that make up an individual’s existing sense of self. More resilience and empowerment are developed to recover from setbacks, and deficits in psychological well-being can be addressed.

Figure 2.

Depicts the process from behavior initiation to maintenance, where centered identity transformation decreases the burden on executive function over time. Please note, this is not a linear, nor stage based process, but the four examples illustrate the relative importance of executive function and centered identity at four points along the sliding, diagonal continuum. The width of the outline indicates the accessibility of both executive function and centered identity, each becoming more accessible over time. More complex behaviors and less supportive environments and individual states may necessitate more recruitment of executive function during maintenance; but overall, the burden on executive function is reduced over time. Intervention strategies for behavior initiation, and improving executive function and centered identity transformation are provided.

Initiation of Behavior Change

An essential prerequisite for adaptive behavior change is intact EF (Cohen & Squire, 1980; Mishkin et al., 1984), which Fuster (2008) defines as, ‘the ability to temporally organize purposive behavior, language, and reasoning’ (p. 191), essential components of which are the planning and initiation of purposeful behavior, and the inhibition of attentional interference and behavioral impulsivity. More broadly, it may be considered as comprising a set of overlapping cognitive control processes (e.g., attentional and inhibitory control, monitoring of conflicting information, planning, working memory, shifting) that are necessary to engage in goal-directed behavior (Miyake & Friedman, 2012), especially over an extended period of time. EF is required for deliberate, conscious behavior that inhibits habitual, implicit, and impulsive processes; it frequently involves delaying gratification, and places more value on long-term rewards over easier, more automatic, or hedonically rewarding experiences in the moment (Miller & Cohen, 2001). EF is important for performing health behaviors that decrease chronic disease risk (Hall & Marteau, 2014)

Associated with EF are active self-regulation and self-control. A large body of research demonstrates that both contribute to the initiation of purposeful activity among motivated individuals. Self-regulation is defined as a goal-guided process in which behavior is controlled to attain and maintain personal goals (Bandura, 2005; Maes & Karoly, 2005), and self-control is defined as the ability of the individual to alter dominant responses or inner states such as impulses, urges, emotions, and thoughts, and replace them with a different response in the service of higher order goals, attitudes or standards (Friese, Hofmann, & Wiers, 2011). These abilities allow people to set, focus on, and monitor progress toward health behavior goals (Bandura, 2005; Maes & Karoly, 2005). Most health behaviors require a degree of effortful control and conscious, top-down processing, particularly when such behaviors are initially unfamiliar and not habitual. Relatively more complex health behaviors continue to require selfregulation and self-control.

In comparison with the automaticity that characterizes many daily behaviors, EF, selfregulation and self-control typically involve relatively slow, effortful, and error-prone cognitive processing. Inherent EF abilities help with initiation and self-regulation, but people tend to default to a habitual or automatic mode of functioning in novel, complex, or threatening situations (Shallice, 1988). Individual (trait) differences, variability in physiological state (e.g., mood, energy level, endocrine and immune status, intoxication, “hot” states, and ego-depletion; but see Hagger, Chatzisarantis, et al., 2016), and situational factors such as stress, cognitive load or demand, and tempting environmental stimuli are known to affect the extent to which EF can be activated and used to successfully guide behavior (Appelhans, French, Pagoto, & Sherwood, 2016; Baumeister, 2002; Hagger, Luszczynska, et al., 2016; Hall & Fong, 2007; Heatherton & Wagner, 2011; Hofmann, Schmeichel, & Baddeley, 2012). Hence, the effortful processing characteristic of EF is not a sustainable or realistic strategy over the long-term for most people, particularly when adopting a more complex health behavior, and when confronted with the realities and stressors of life outside the context of an intervention.

Classic intervention approaches that seek to improve the social cognitive antecedents of intentions are also problematic because they tend to be more successful strategies for those with inherently greater executive control (Allan, Johnston, & Campbell, 2011). Even approaches like implementation intentions, which are designed to decrease the need for effortful control in the moment, are shown to be more successfully utilized by those with higher inherent EF ability (Hall et. al., 2014). Strategies that can help scaffold these approaches and can work equally well among those with high and low in EF ability are currently lacking.

The Maintain IT model posits that effortful processing for self-regulation is not sustainable for maintaining health behaviors in part because of the effect that emotions and emotion regulation have on rational decision-making and EF. Research in behavioral economics has found that emotions and emotional arousal can disrupt rational decision-making, either by contributing to constraints on cognition (Kaufman, 1999), or in functional ways that motivate behavior contrary to optimal or ‘reasonable’ choices (Muramatsu & Hanoch, 2005) Empirical evidence demonstrates that emotions affect EF in the domains of attention, learning, and memory (reviewed in Muramatsu & Hanoch, 2005). Negative emotions and poor emotion regulation are associated with decreased activation in certain areas of the brain associated with self-control and self-regulation, and individuals who have difficulties regulating emotions frequently have difficulty with goal-directed behavior (Tang, Posner, Rothbart, & Volkow, 2015).

Stress has also been shown to increase impulsivity and disrupt prefrontal processing and attentional control (Liston, McEwen, & Casey, 2009), but cognitive ability appears to play a role in individual responses. For example, individuals with greater working memory capacity are better able to deal with negative feedback (Schmeichel & Demaree, 2010), and happiness may increase working memory capacity (Storbeck & Maswood, 2015). There is substantial overlap in the areas of the brain that influence self-regulation and emotion regulation and processing, which may lead to interference or contribute to cognitive load and self-regulatory depletion. This has led some to argue that stress, emotion regulation and self-regulation should be considered as integrated processes, thereby allowing us to more accurately understand the ways emotions and goal-pursuits influence one another (L. M. Diamond & Aspinwall, 2003). Maintain IT builds on this research, asserting that behavior change interventions to improve EF (detailed later) can be used at the beginning of an intervention to improve successful initiation. But it further suggests that intervention strategies that provide people with tools to regulate emotions generally, but are not necessarily related to behavior, may indirectly increase health behavior by improving the likelihood that successful recruitment of EF and self-regulation can occur.

Long term maintenance will be much more likely if the need for effortful, relatively slow processing that is prone to errors and adversely affected by physiological and psychological states and environmental conditions can be reduced over time. Maintain IT asserts that by activating other functional systems to reduce or circumvent the need for EF, it will be possible to facilitate recovery from inevitable setbacks and lapses in behavior without obstructive emotional stress.

Maintaining Behavior Change

Maintain IT proposes that a process of identity transformation towards a centered identity (i.e., one that allows for integration of the behavior with already formed components of identity, and more resilience in the face of emotions, stress, and lapses in behavior) is one approach to facilitate the maintenance of behavior change over the long-term. This transformation involves integrating the newly adopted behavior with one’s sense of self, and developing a more centered and empowered state for this sense of self. This transformation can complement the majority of approaches used currently that rely heavily or exclusively on effortful EF. As the behavior becomes a part of one’s identity, it requires less effortful self-regulation (Ryan & Deci, 2000). And as one’s identity is more centered and empowered, the harmful effects of inevitable setbacks, stress, emotions, or other difficulties on self-regulation are reduced.

Maintain IT extends goal-oriented self-regulation approaches by acknowledging that knowing where one wants to go is necessary, but insufficient, for planning an effective route to that destination. In order to strategize how to achieve behavior or health goals, individuals must first know their point of origin. The model asserts that identity transformation can begin with a process of reflection and exploration of individuals’ perceptions of the most fundamental roles and groups that constitute their identity and the degree to which adopting the behavior is consistent, or at odds with their identity and values (Brook, Garcia, & Fleming, 2008). This examination can serve two purposes. First, it can help individuals adopt and integrate the behavior in ways that are consistent with fundamental aspects of their identity wherever possible. Second, it can ascertain aspects of identity that are unlikely to change (family roles/relationships), but can make adopting the behavior for the long-term more difficult. This latter aspect of the discovery process can illuminate social contexts where more self-regulatory effort will be required to engage in the behavior, and to strategize the implementation intentions to be used under more difficult circumstances.

Several converging lines of evidence support the importance of identity as a central component of successful self-regulation of health behavior. Overall, an understanding of the self (i.e., an individuals’ belief about the totality of himself or herself, including the body, sense of identity, and attributes about who and what the self is; Baumeister, 1999), is fundamental to selfregulated behavior (Heatherton, 2011). For example, aspects of identity, such as masculinity, are related to drinking and risk taking (Bishop, Weisgram, Holleque, Lund, & Wheeler-Anderson, 2005; de Visser & Smith, 2007; Lewis et al., 2010). Identity has shown to be important for exercise and physical activity (Rhodes, Kaushal, & Quinlan, 2016), in food choices (Bisogni, Connors, Devine, & Sobal, 2002; Fox & Ward, 2008; Strachan & Brawley, 2009), and in diabetes management (Liburd, 2003; Luyckx et al., 2008; Tilden, Charman, Sharples, & Fosbury, 2005). Further, integrating the health behavior into an individual’s sense of self, and creating a self-schema consistent with the behavior (in addition to repeated performance), can aid the formation of associative networks, increased attention, and more efficient processing (Bargh, 1982; Tacikowski, Freiburghaus, & Ehrsson, 2017). These associative networks, increased attention and more efficient processing may reduce the level of effortful control needed to perform the behavior. Foundational work from identity theory (or identity control theory) and social identity theory (Stets & Burke, 2000) also detail the centrality of roles and social structure for the formation of identity. Identity control theory further suggests that individuals form a set of standards that correspond to the meaning and expectations of a given identity and are inherently motivated to behave in ways that are consistent with their values and conceptions of themselves (Burke, 2006). When behavior does not align with identity standards, it creates negative affect, and motivates behaviors that reinforce self-concept. Thus, incorporating the new behavior into one’s identity allows it to become more self-reinforcing. These ideas are also consistent with self-determination theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000), which details the advantages of moving from external regulation to perform a behavior, to more integrated and autonomous forms of regulation, where the behavior is in line with the self-concept of the individual. Maintain IT goes beyond these perspectives to suggest that integrating behavior into identity has the added advantage that it can reduce the need for slow, effortful processing to guide behavior, because self-schemas (heuristic cognitive generalizations about the self) allow self-relevant information to be processed more efficiently and quickly than non-relevant information (Markus, 1977).

Components of centered identity.

The centered identity construct is comprised of behavior-based identity, role- and group-based identities, personal values, perceptual lens, and psychological well-being.

Behavior-based identity.

Behavior-based identity is merely the extent to which an individual identifies as a person who performs a given behavior. It has been shown to be an important predictor of health behaviors (e.g., Rhodes et al., 2016; van den Putte, Marco, Willemsen, & Yzer, 2009). It is predicted by Maintain IT to change with repeated performance of the behavior, and to improve with successful integration of the behavior with other aspects of identity (Gillman & Bryan, 2017). It may also limit the damage of lapses, as one study demonstrated that those with a more highly developed behavior-based identity perceived the reasons for having a lapse in behavior as being more transient (Kendzierski & Sheffield, 2000).

Role- and group-based identity.

Identity is also defined as a set of hierarchically organized multi-dimensional components including roles that correspond to the social structure (Stryker & Burke, 2000). To improve the likelihood of maintaining behavior change, individuals may need to examine the roles and groups that are most fundamental to their identity, and determine those that will facilitate versus those that will inhibit changes in health behaviors or identity. The process of identity transformation involves integrating the new health behavior into one’s sense of self, recognized anew after initial examination. This will allow individuals to more appropriately specify behavioral strategies whenever possible that simultaneously reinforce the health behavior and honor the most fundamental aspects of one’s role- and group-based identities. Concurrently, recommendations should also be made to distance oneself from groups and roles that are anticipated or experienced to inhibit transforming behavior, and to obtain and sustain supportive groups and roles that reinforce behavior integration to increase the likelihood that behavior will be maintained over the long-term. When the existing role or group based identities are not congruent with the behavior, but it is not possible or desirable to change those roles or groups, individuals should be encouraged to recognize that these contexts will necessitate more active self-regulation and successful recruitment of EF. Developing implementation intentions for these identity-based unsupportive environments constitutes one potentially effective strategy adapted from existing approaches for the Maintain IT context. This awareness can also improve resilience, because interventions can highlight that failures are more likely in unsupportive environments, and individuals can recognize that the failure was partly due to transient/situation specific conditions, rather than global and stable ones.

Personal values.

Personal values have a long history in the clinical psychology and behavior change literatures. Rokeach (1973) argued that values are core beliefs that guide behavior, provide impetus for motivating behavior, and provide standards against which behavior is assessed. Clinical and behavior change approaches like acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes, 2004), motivational interviewing (Rollnick & Miller, 1995), and the disconnected values model (Anshel, 2008) are widely used and empirically supported approaches in which values play a foundational role. Overall, individuals who live with a daily awareness of what they value are better able and more motivated to make choices that support their health and well-being (Hooker & Masters, 2018; Roepke, Jayawickreme, & Riffle, 2014), including choices about health behavior (Segar, Eccles, & Richardson, 2011).

Perceptual lens.

The perceptual lens is defined herein as a filter through which new circumstances and information are perceived and interpreted. As depicted in Figure 1, centered identity influences behavior directly, as well as indirectly through this perceptual lens; thus, the relationship between perceptual lens and centered identity is bidirectional. This relationship helps determine the course of action (or inaction) individuals take in response to environmental circumstances.

There are two novel components of the perceptual lens that are the primary focus of Maintain IT and are hypothesized to improve resilience and increase success at long-term maintenance. The first component of perceptual lens is attributional or explanatory style, that is the ‘default’ tendency to interpret positive and negative events (Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978). In behavior change, a more pessimistic attributional (or explanatory) style is one that would interpret difficulties and setbacks as being internal, stable, and global, and is predicted to make lasting behavior change more difficult. A more optimistic style is one that views setbacks as situational, transient, and specific, and is predicted to facilitate lasting behavior change and recovery from lapses in behavior. The second component of perceptual lens is implicit theory surrounding behavior and identity change, or the extent to which one believes the behavior of interest and identity more generally are malleable and within individual control to change (incremental implicit theory), as opposed to stable and impossible to change (entity implicit theory; Dweck, 1999). An entity (or fixed) implicit theory is likely to make lasting behavior change more difficult, whereas an incremental (or growth) implicit theory will facilitate lasting behavior change.

Psychological well-being.

As with perceptual lens, the relationship between centered identity and psychological well-being is bidirectional (see Figure 1). The primary focus for psychological well-being is on eudaimonic well-being, a multidimensional construct that represents positive psychological function or flourishing (Ryff, 1989; Ryff & Keyes, 1995). Eudaimonic well-being is related to, but not synonymous with subjective or hedonic well-being (i.e., happiness, high positive affect, or satisfaction). Eudaimonic well-being is particularly relevant during the health behavior change and identity transformation processes because it is associated with integrating perceptions of the past, present, and future, whereas subjective wellbeing is largely present-oriented (Baumeister, Vohs, Aaker, & Garbinsky, 2013). Many health behaviors are not inherently enjoyable (Ryan, Patrick, Deci, & Williams, 2008), and may even be unpleasant, and thus demand the ability to tolerate distress (Hayes, 2004), at least initially. Further, long term behavior change that involves in-depth examination of the self, values and goals for future health is not expected to immediately or exclusively evoke positive feelings (hedonic well-being). However, goal-directed behavior has been shown to be associated with greater eudaimonic well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001), and existential writers such as Frankl (1997) demonstrated the potency of meaning for perseverance in the face of adversity.

Eudaimonic well-being includes six core dimensions: purpose in life, environmental mastery, positive relationships with others, personal growth, autonomy, and self-acceptance (Ryff & Keyes, 1995). This perspective precedes, but in some ways broadens the formative work of Deci and Ryan’s SDT (Deci & Ryan, 2000). SDT is founded on the premise that people have innate psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, and are more highly motivated when environments satisfy these needs (Ryan & Deci, 2001). These psychological needs are analogous, though not identical to, three of the six facets of psychological well-being as defined by Ryff and Keyes (Lent, 2004).1 Maintain IT extends these perspectives by suggesting that rather than only focusing on three of the dimensions outlined by Ryff and colleagues, deficits in any of the six dimensions of well-being can stall or prevent progress toward adopting and maintaining health behaviors or lead to relapse. Maintain IT suggests that in addition to having a high overall sense of positive engagement in life (high eudaimonia), balance among the facets of psychological well-being is important for optimal well-being (Sirgy & Wu, 2009). Scheier and colleagues (2006) also suggest that connecting to one’s purpose or meaning in life is an important aspect of behavioral self-regulation, because it provides the intrinsic ‘why’ for engaging in and maintaining certain behaviors.

Eudaimonic well-being is robustly related to better health, including biomarkers of health (e.g., lower cortisol and inflammatory markers), longitudinal self-reports of health, and even the prevention of and recovery from health problems (Ryff, 2014; Ryff, Radler, & Friedman, 2015; reviewed in Vázquez, Hervás, Rahona, & Gómez, 2009). However, causal properties of this relationship, if any, are unknown. Maintain IT predicts that whereas health can improve psychological well-being, intervention approaches that help individuals improve psychological well-being can also support health behavior maintenance. Maintain IT hypothesizes that deficits in psychological well-being increase both the drive for unhealthy behaviors and cognitive load, particularly the demand for emotion regulation. This may render self-regulation less likely; and lead to unhealthy coping behaviors and poorer resilience in the face of inevitable setbacks and stress.

Within the Maintain IT framework, broader improvements to perceptual lens (attributional style and implicit theory) and psychological well-being can make performing healthy behaviors less effortful and facilitate sustained behavior change in several ways. Perceptual lens and psychological well-being can improve the way individuals regulate emotions and deal with stressors, fostering a psychological state more conducive to self-control and selfregulation. It may also decrease impulses to perform unhealthy coping behaviors, and strengthen resilience to deal with impediments and obstacles that can lead to lapses and relapses. For example, an fMRI study showed that individuals with higher eudaimonic well-being have slower response and lower activation of the amygdala in response to aversive stimuli (van Reekum et al., 2007). This suggests that improvements to eudaimonic psychological well-being may blunt the physiological response in the brain to negative or aversive circumstances.

Maintain IT posits a bidirectional relationship between behavior and centered identity, such that performing healthy behaviors improves multiple aspects of the centered identity, particularly behavior-based identity, incremental implicit theory (the belief that behavior and identity are malleable), and psychological well-being. In this way, a positive feedback loop is stimulated, leading the behavior to become more self-reinforcing, and decreasing the need for effortful self-regulation. This approach can further increase the likelihood that successful selfregulation can occur even under stressful or unsupportive conditions by enhancing eudaimonic well-being and perceptual lens to create a more centered, balanced, and empowered sense of self.

Further, broad improvements to psychological well-being and perceptual lens will reduce the effect that stress and negative emotions have on cognitive load, thus increasing the likelihood that the reflexive, self-control system is not overly taxed, distracted, or depleted. The newly formed centered identity will allow performing the behavior to be more cognitively efficient, and more resilient in the face of setbacks and conditions that make successful self-regulation less likely.

The importance of identity in the performance and maintenance of health behaviors is widely recognized. In a recent meta-analysis on identity/schema in association with physical activity, there was a robust and significant positive relationship (r = 0.44), on par with intentions (Rhodes et al., 2016). Self-identity has also been included by some in the Theory of Planned Behavior, and significantly adds to the predictive power of the model to predict intentions and behavior (e.g., Bélanger-Gravel & Godin, 2010; de Bruijn & van den Putte, 2012; Sparks & Guthrie, 1998). Identity in health behavior research thus far primarily focuses on behavior-based aspects of identity. Maintain IT extends the behavior-based identity, in order to appreciate that identity also includes the roles (e.g., parent, nurse, etc.), groups, and values that are fundamental to the individual. This broader conceptualization of identity can allow individuals to incorporate and colleagues (2016) systematically reviewed 100 behavior change maintenance models and presented five overall themes. Identity was recognized as a core component of the maintenance authors conclude that identity is important because people are more likely to behave in ways that more quickly and efficiently than non-relevant information. Identity (i.e., self-concept) was also identified as an important factor in weight loss maintenance in a recent systematic review of qualitative studies (Greaves, Poltawski, Garside, & Briscoe, 2017). The authors noted that identity can inhibit weight loss maintenance when identity is inconsistent with weight management behaviors. In contrast, successful weight loss maintainers list a change in their selfperceptions as an important factor contributing to their success.

Maintain IT in Practice

The goal of the Maintain IT model is to pragmatically integrate previous lines of theory and research to inspire interventions that result in lasting behavior change. The following sections briefly summarize the current state of evidence for relatively novel intervention approaches and techniques that improve individual and combined facets of Maintain IT. By highlighting these approaches we hope to draw attention to existing conceptual links between Maintain IT and current intervention approaches. An example of an intervention drawing from some of these approaches follows.

Approaches that Target EF

The literature on training EF has yielded mixed results for a number of reasons. For example, samples range from children (A. Diamond & Lee, 2011) and healthy undergraduates (Soveri, Waris, & Laine, 2013) to experienced (Tsai & Chou, 2016) and very experienced (Van Vugt & Slagter, 2014) meditation practitioners. In most cases, the range of EF capacity was relatively narrow, with few individuals showing impairment that was worse than mild. Training and experience were similarly variable, ranging from one brief guided session of meditation (Colzato, van der Wel, Sellaro, & Hommel, 2016) through the use of extremely experienced meditation practitioners (Tsai & Chou, 2016; Van Vugt & Slagter, 2014). Interventions have included aerobic exercise (Hillman, Erickson, & Kramer, 2008), computerized training (Mackey, Hill, Stone, & Bunge, 2011), commercially available online training (Thorell, Lindqvist, Nutley, Bohlin, & Klingberg, 2009), mindfulness meditation (Gallant, 2016), focused attention and open monitoring meditation (Colzato, Sellaro, Samara, Baas, & Hommel, 2015; Tsai & Chou, 2016), Ch’an (Zen) and Confucian movement-based meditation (Teng & Lien, 2016) and others (A. Diamond & Lee, 2011). Further complicating the issue is the variety of conceptualizations of EF, and the different instruments used to measure EF or its subcomponents.

EF plays an essential role in a number of health-related behaviors (Tran, Baxter, Hamman, & Grigsby, 2014), including weight control (Gettens & Gorin, 2017). But EF is mediated by a modular, distributed anatomic network involving different areas of prefrontal ortex, as well as the dentate, caudate, and subthalamic nuclei, dorsomedial thalamus, and other regions, and the fiber tracts that connect them (Fuster, 2000, 2008; Grahn, Parkinson, & Owen, 2008; Schmahmann & Sherman, 1998), and the specific subcomponent functions associated with these regions vary in importance for different behaviors. In general, inhibitory control appears to improve somewhat more with adequate practice than other aspects of EF, such as set-shifting and working memory. Techniques such as mindfulness meditation (Gallant, 2016) and an adaptive version of the stop-signal task (Berkman, Kahn, & Merchant, 2014) have demonstrated success at improving inhibitory control. However, a meta-analysis of studies that examined the effects of training inhibitory control on subsequent health behavior concluded that the effects of improving inhibitory control may only be effective in the short-term, and more studies are needed to examine the longevity of training effects (Allom, Mullan, & Hagger, 2016). Set-shifting ability was less readily improved (Soveri et al., 2013), although Tsai and Chou (2016) reported a positive effect on this subcomponent of EF in association with Ch’an training. Working memory appears to be the most difficult of these three executive sub-functions to improve, at least with techniques that show a generalization of improvement beyond performance on the training task and related skills, although certain approaches show a positive effect (Au et al., 2015; Salminen, Kuhn, Frensch, & Schubert, 2016).

Some recent work has shown promise for training implicit impulses and EF to increase health behaviors. Friese and colleagues (2011) note that a dual systems approach can inform interventions by considering three components: reflective processes (attitudes, personal standards); impulsive processes; and self-control abilities. They summarize a growing number of recent studies that demonstrate possible targets to change impulsive processes by training changes in automatic associations, attentional biases, and approach tendencies. There is some evidence that interventions can train impulses and facilitate the creation of associative networks that reduce the need for effortful control to perform behavior (described in more detail in Example of Maintain IT Intervention below). These approaches have been successful at training automatic associations and implicit approach/avoidance tendencies for eating unhealthy foods and drinking alcohol, as well as changing behaviors themselves (Fishbach & Shah, 2006; Houben, Havermans, & Wiers, 2010; Houben & Jansen, 2011; Leeman, Wiers, Cousijn, DeMartini, & O’Malley, 2014; Wiers, Eberl, Rinck, Becker, & Lindenmeyer, 2011; Wiers, Rinck, Kordts, Houben, & Strack, 2010). Episodic future thinking, or vivid simulations of future events, is another technique that has shown promise for decreasing impulsivity (Benoit, Gilbert, & Burgess, 2011; Bickel, Yi, Landes, Hill, & Baxter, 2011; Gellert, Ziegelmann, Lippke, & Schwarzer, 2012). The relationship between EF and health behaviors may also be bidirectional, such that changes in behavior (increasing physical activity, quitting smoking) may improve EF (Colcombe & Kramer, 2003; Gettens & Gorin, 2017; Gunstad et al., 2007; Heijnen, Hommel, Kibele, & Colzato, 2016; Loprinzi et al., 2015; Sofis, Carrillo, & Jarmolowicz, 2017). Despite some evidence suggesting that healthy changes in behavior may lead to improvements in EF, this is far from conclusive currently (Gettens & Gorin, 2017).

Trait-level working memory capacity may be largely stable, but the ability to improve working memory over the short-term (Melby-Lervåg & Hulme, 2013), and successfully employ working memory in emotional contexts (Schweizer, Grahn, Hampshire, Mobbs, & Dalgleish, 2013; Schweizer, Hampshire, & Dalgleish, 2011), may be amenable to training. The latter types of training may be important for health behavior change interventions, because they increase the likelihood that self-regulation can occur in emotive environmental conditions. In addition, a recent study demonstrated that impulsivity could be experimentally reduced with a negative urgency task, but particularly among those who were lower in working memory (Gunn & Finn, 2015). If working memory is more difficult to change, approaches that work better for those lower in working memory will be particularly valuable, because existing intervention techniques have been shown to be more successful in those with greater working memory (Hall et al., 2014).

Maintain IT builds on this work, by suggesting that approaches which improve response inhibition, and reduce impulsive behaviors help create associative networks surrounding the health behavior and potentially improve state level working memory. These approaches can complement self-regulatory approaches focused on the reflective system, like goal setting and monitoring. The fluid structure of Maintain IT suggests that such approaches may be more important during behavior initiation, when EF strategies and abilities are most needed.

Approaches that Target Centered Identity

A large body of research demonstrates that behavior-based identity is associated with the successful performance of health behaviors. Behavior-based identity is largely comprised of one’s perception of the frequency with which they have engaged in the behavior in the past, therefore the transformation of this facet of identity is expected to occur primarily after successfully adopting and performing the behavior repeatedly. The novel aspect of Maintain IT is that it also considers aspects of identity more broadly, beginning with an examination of personal values, and fundamental role- and group-based identities, and the extent to which the behavior is consistent with or at odds with these values and identities. Second, Maintain IT proposes that it is critical for individuals to link the health behavior to their values, and find individualized ways to incorporate the behavior to be consistent with, rather than at odds with, fundamental roles and groups central to their identity. Some fundamental roles may be in opposition to the behavior, but are not changeable (e.g., child of unhealthy parent), or individuals may simply not want to change them (e.g., spouse of unhealthy partner). The practice of identifying unsupportive roles can be helpful to be able to set implementation intentions for how to deal with these unsupportive roles, and attribute setbacks in the context of these roles as being transient, rather than global. This optimistic attribution can improve resilience and recovery in the face of such setbacks.

Next, individuals examine their social or group-based identity, to ascertain groups with which they identify, that are important to them, that have values or goals that contrast with the health behavior, or that will resist attempts to transform aspects of identity. As with roles that are in opposition to behavior, remaining in groups that do not value the new behavior may be necessary, or desired, but will require more active self-regulation, and therefore make maintenance more difficult over the long-term. Important personal relationships that inhibit the adoption of a health behavior or transformed identity may create emotional turmoil and stress, which can increase the need for more effortful self-regulation, but decrease the likelihood that it can occur. Implementation intentions, or similar approaches that acknowledge difficult social circumstances and anticipate strategies for dealing with them, can likely help people maintain health behavior. Social support, on the other hand, has been shown to significantly increase both completion of a weight loss intervention, weight loss during an intervention, and long-term maintenance of weight loss (Wing & Jeffery, 1999). When necessary, individuals may need to develop new, supportive social relationships or groups that will not push back against the adoption of a new health behavior or the formation of a new, more centered identity. Interventions should facilitate the formation of new relationships and groups (even virtual groups) for support, and the development of a transformed group-based identity (Coursaris & Liu, 2009). Positive and strong relationships with others represent a core dimension of psychological well-being (Ryff & Keyes, 1995), and are important for the formation of identity (Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

The Maintain IT model predicts that interventions that support people’s attempts to examine their identity, set goals consistent with their values, and integrate behavior in ways that reinforce their fundamentally valued roles/groups will increase how autonomously they view their goals and behavior, and in turn, improve the likelihood of long-term maintenance. This is in line with a large body of theoretical and empirical work from SDT that demonstrates that people are more likely to consistently perform a behavior that is autonomously chosen and directed (Teixeira, Silva, Mata, Palmeira, & Markland, 2012).

Maintain IT suggests that interventions should also integrate methods to improve psychological well-being and perceptual lens. Promising approaches from positive and clinical psychology have shown that well-being can be improved through writing gratitude letters or journals, count-your-blessing exercises, practicing optimistic and positive thinking, and expanding positive relationships with others (Chan, 2010; Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Ryff, 2014; Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009). Practicing gratitude and developing a more grateful orientation during the IT process is expected to improve several dimensions targeted in the centered identity construct of Maintain IT. Gratitude has been shown to predict well-being, both directly and through perceptions of social support and fostering adaptive coping styles, and is related to lower stress and depression during a life transition (Lin & Yeh, 2014; Wood, Maltby, Gillett, Linley, & Joseph, 2008). Further, gratitude may be an intervention approach to which people are more able to adhere; for example, one bodydissatisfaction intervention demonstrated that twice as many people completed a gratitude intervention compared to a control intervention (Geraghty, Wood, & Hyland, 2010).

Approaches that Target Multiple Facets of Maintain IT

Research has shown that mindfulness is an approach that targets EF and centered identity components. Mindfulness can be used to train attention and working memory, and can help regulate areas of the brain associated with self-control (e.g., ACC, mPFC) and reduce the drive for addictive health-risk behaviors (Tang, Posner, Rothbart, & Volkow, 2015). Mindfulness is also related to greater psychological well-being (Brown & Ryan, 2003), lower stress (Creswell, 2015), and engagement in health behaviors directly (Roberts & Danoff-Burg, 2010).In a preliminary study, a mindfulness-based meditation intervention demonstrated significant effects on physical health that were mediated by perceptions of social connectedness (Kok et al., 2013), which suggests that mindfulness can also potentially improve group-based identity and the relatedness facet of psychological well-being.

Some authors have suggested that the relationship between mindfulness and health/wellbeing is mediated by self-compassion (Baer, 2010; Hölzel et al., 2011). Proponents posit that self-compassion is particularly useful in promoting resilience in the face of minor failures (Neff, 2011; Neff, Kirkpatrick, & Rude, 2007) and specifically when trying to adopt health behaviors or reach a health-related goal (Sirois, Kitner, & Hirsch, 2015). Some suggest that self-compassion promotes self-regulation, because it helps individuals set appropriate goals, monitor progress toward goals, regulate emotions and promote emotional resilience and stability (Terry & Leary, 2011). Self-compassion is also associated with intrinsic motivation and greater personal initiative to make necessary changes and has been shown to facilitate health behaviors (Neff, 2003). A recent meta-analysis of 15 studies found that self-compassion is associated with health behaviors directly, though the effect size was small (r = .25; Sirois, Kitner, & Hirsch, 2015). Importantly, self-compassion has been shown to improve when targeted via multiple intervention approaches (Barnard & Curry, 2011). The Maintain IT model predicts that self-compassion and mindfulness will also lead to attributional styles more amenable to recovering from setbacks.

Example of a Maintain IT Intervention

The sections above demonstrate that Maintain IT has common ground with many current interventions or aspects thereof. However, we believe that full consideration of the Maintain IT model may lead to a systematic and effective integration of these interventions. To that end we present a case example. Consider a woman who is enrolled in a Maintain IT intervention to increase physical activity. First, the intervention could involve activities designed to train the impulsive system and improve inhibition and attention. Activities could be designed to train approach/avoidance implicit tendencies by having participants pull a joystick toward themselves when viewing images or words associated with physical activity, and pushing the joystick away from themselves when viewing images or words associated with sedentary behaviors. This approach has proven effective to influence unhealthy eating (Fishbach & Shah, 2006) and decreasing and abstaining from alcohol consumption (Leeman et al., 2014; Wiers et al., 2011). Similarly, Go/No-Go tasks could be adapted for physical activity as they have been successfully adapted to train inhibition for drinking beer (Houben, Nederkoorn, Wiers, & Jansen, 2011) and eating chocolate (Houben & Jansen, 2011).

On the identity side, the intervention would first involve examining the fundamental roles and groups that constitute identity, and rate the extent to which those roles and groups are consistent with (or in contrast to) adopting and maintaining physical activity (adapted from Brook et al., 2008 to measure identity congruence). Upon this examination, the participant might discover that she identifies with being a mother and belonging to her family as the most fundamental to her identity; but sees both as working against her ability to adopt and maintain physical activity. The intervention can encourage her to find individualized ways to frame exercise as a part of investing in her children, focusing on the ways being active sets a good example, allows her to more fully engage with her children, and makes it more likely she will live long enough to care for her children. The intervention should encourage her to incorporate physical activity in ways that reinforce her role as a mother, including taking her family to the park or walking or hiking with her child in a stroller or backpack, rather than having her identity as an ‘exerciser’ compete with her identity as a ‘mother’ (requiring time and resources to find a babysitter to spend time away from her child and go to a gym). Incorporating the behavior into her role-based identity may encourage the behavior to become more automatic because the behavior becomes self-relevant, and aligns with and reinforces both her fundamental role-based identity and her goal to be more active. This process would be expected to increase her integrated (i.e., more autonomous) form of motivation. In terms of perceptual lens, the intervention would adopt techniques that are used in implicit theory interventions to teach or reinforce characteristics such as intelligence (Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007), personality (Yeager et al., 2014), and weight loss (Burnette & Finkel, 2012) are malleable (incremental) rather than fixed (entity). This can change perceptions about whether being an active person is a malleable trait, rather than fixed trait. To our knowledge, no intervention approaches have been developed in health behavior adoption contexts to help individuals develop more optimistic attributional styles (i.e., styles that interpret negative events or setbacks as being situational, transient, and specific, or positive events as being global). However, we are confident that approaches that have been used in the treatment of depression to improve attributional style, can be adapted for health behavior contexts. Recall that the woman in our example sees her family as the group that is most fundamental to her identity, but is at odds with increasing physical activity. Increasing physical activity will not be more important than being part of her family, and we would not expect her to change families in order to succeed at increasing physical activity. But recognizing that her family social context will make changing and maintaining physical activity more difficult, she can then set implementation intentions to increase the likelihood that she can be active in these difficult circumstances. She can also learn to utilize a more optimistic attributional style by recognizing failures in difficult social contexts as being situational, transient, and specific, as opposed to internal, stable, and global. This is predicted to help recovery from setbacks and improve resilience. Clinical approaches currently in use, such as ACT and the disconnected values (intervention) model (Anshel, Brinthaupt, & Kang, 2010; Anshel & Kang, 2007; Anshel, 2008) include careful consideration of values in order to engage discussion around values clarification and to explicitly align endorsed values with behavior. These approaches parallel Maintain IT and provide specific techniques for use in clinical behavior change settings that can be incorporated into health behavior change interventions. Finally, techniques from positive psychology interventions summarized above that improve psychological well-being and multiple facets of Maintain IT more broadly (i.e., not behavior specific) such as mindfulness, gratitude, and self-compassion exercises should also be incorporated. These techniques are predicted to improve the likelihood that EF can be recruited when necessary, reduce the drive for health-risk behaviors, and help build resilience to recover from setbacks.

Summary, Challenges, and Predictions

Maintain IT aims to build on approaches to health behavior change that recognize the limitations of interventions that depend primarily on self-regulation strategies that involve cognitively taxing EF and rational, top-down, conscious processing. These approaches are crucial for the initiation of healthy behavior, but for most people, this type of effortful control is not sustainable. Maintain IT posits that a process of centered identity transformation is one potent strategy for creating less effortful and ultimately more self-reinforcing behavior, and allowing individuals to be resilient in the face of difficult circumstances and inevitable setbacks. This approach acknowledges that EF is critical for behavior initiation, for more complex behaviors beyond initiation, and in less supportive individual or environmental circumstances; but emphasizes that decreasing the need for effortful control, and increasing the likelihood that EF can be successfully recruited when necessary, will help make behavior changes more likely to be maintained. Second, existing approaches do not typically factor in individual differences aside from measuring previous behavior and motivation or readiness to change (i.e., the strength of intentions to begin a new behavior) at the outset of an intervention. In contrast, Maintain IT incorporates not only past experience with the behavior of interest and motivation to change, but also includes differences in individuals’ perceptions of the fundamental roles and groups that constitute identity. By working to incorporate the target behavior within the fundamental aspects of an individual’s identity and values, and more broadly improving psychological well-being and perceptual lens, behavior change methods need not rely solely on strategies that utilize slow and costly EF that tend to only succeed in the context of an intervention or particular environment, or that are more effective for those higher in EF. Further, this approach buffers against the challenges that often lead people to revert back to unhealthy behaviors, such as cognitive load, ego-depletion, intoxication, “hot” states, novel and/or unsupportive environments, stress, and emotion/affect.

Maintain IT is the product of decades of research and thought collectively among the authors in multiple domains of behavior change, but is itself in the early stages of development. We acknowledge its limitations and several challenges that need to be overcome in order to acquire the data necessary to support or refute the assertions of the model. As with all models, it is an over-simplification of the truly complex set of interrelated factors that influence behavior change and maintenance. The first notable challenge is that not all constructs in the model can be reliably and validly measured at present. The development of appropriate and potentially behavior-specific measures for each of the constructs will be necessary. Second, this is a model of process and maintenance, which means outcomes based on long-term maintenance will require longitudinal research for which funding may be difficult to obtain. Third, many of the approaches are individualized, or are modeled after clinical approaches that require one-on-one interactions that are not ideal for large, population-based interventions. However, if they are substantially more effective than current approaches, the costs and benefits of including some level of individualized, patient centered approaches can be evaluated. In addition, many of these approaches are being developed for digital formats that would allow for lower-cost solutions (Dimidjian et al., 2014). In addition, the most effective way to facilitate the process of identity transformation is not currently well-understood. Finally, the model suggests that EF is important both during the initiation phases of behavior change and under challenging social, contextual, or emotional circumstances. Thus, from an intervention perspective, it is unclear what the “critical timing” of the presentation of each of these strategies might be. It will take many iterations and creative experimental designs including adaptive randomization (Zhang & Rosenberger, 2012) to determine what the optimal order and timing for the different components will be.

Despite these challenges, we hope that Maintain IT is inclusive, integrative, and comprehensive enough to shed light on some of the lesser considered factors in sustainable behavior change, that it has meaningful heuristic value, and that it can generate new and clear hypotheses that can be tested and replicated in current and future interventions. An empirical test of the model would measure behavior, EF and aspects of identity (including values, eudaimonic psychological well-being, implicit theory and attributional style) at baseline, during, and at the conclusion of an intervention. Behavior maintenance would be measured with post intervention follow-up measures of behavior. The model posits that EF will predict behavior initiation, and to a lesser degree maintenance. Long-term maintenance will primarily be predicted by the extent to which aspects of identity and values are consistent with, rather than at odds with the behavior, as well as eudaimonic well-being, an incremental implicit theory surrounding changing the behavior, and a more optimistic attributional style. An alignment of identity and values with behavior, an incremental implicit theory, and an optimistic attributional style will be associated with maintenance whether they are present at baseline or developed over time during an intervention. The identity transformation aspects of this intervention approach are predicted to be particularly relevant for more complex behaviors (e.g., diet, exercise), and perhaps more efficacious when attached to circumstances when identity is already changing (e.g., pregnancy, puberty, parenthood, bariatric surgery, cancer diagnosis). Thus, an empirical test could compare the utility of an identity transformation intervention to change a complex behavior compared to one that was more readily automatized (e.g., wearing a seatbelt); hypothesizing that the identity components are less relevant for predicting adherence to more easily automatized behaviors. Another empirical test could compare the efficacy of an identity transformation intervention in a population where identity is changing to one in which identity is not already changing; positing that incorporating the new behavior into identity is more likely when identity is already undergoing change. Other testable predictions we see as relevant to the field of sustainable behavior change that derive from the model include, but are not limited to the following: (a) improvements in EF, behavior-based identity, psychological well-being, and perceptual lens over the course of an intervention predict long-term maintenance of health behaviors, (b) interventions that help individuals integrate health behavior with their role- and group-based identity will lead to greater increases in behavior based identity, autonomous motivation, and maintenance of health behavior changes, (c) centered IT interventions will lead to more successful maintenance compared to traditional, behavior-only focused interventions, and finally (d) a centered IT intervention approach will work similarly well for those inherently high and low in EF. Overall, we hope this approach can lead to more comprehensive, novel interventions that facilitate long-term maintenance of health behaviors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kristen Speaker, Dr. Drew Sayer, Mary Pinter, Jennalee Woodridge, Katie Schneider, and four anonymous reviewers this work was funded by T32 HL116276.

Footnotes

It should be noted that SDT also differs from Ryff’s perspective on well-being in that SDT theorizes that competence, autonomy and relatedness foster well-being, whereas Ryff’s approach uses these constructs to define well-being.

References

- Abramson LY, Seligman ME, & Teasdale JD (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 87, 49–74. 10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan JL, Johnston M, & Campbell N (2011). Missed by an inch or a mile? Predicting the size of intention–behavior gap from measures of executive control. Psychology & Health, 26, 635–650. 10.1080/08870441003681307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allom V, Mullan B, & Hagger M (2016). Does inhibitory control training improve health behavior? A meta-analysis. Health Psychology Review, 10, 168–186. 10.1080/17437199.2015.1051078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anshel MA (2008). The disconnected values model: Intervention strategies for exercise behavior change. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 2, 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1123%2Fjcsp.2.4.357 [Google Scholar]

- Anshel MH, Brinthaupt TM, & Kang M (2010). The disconnected values model improves mental well-being and fitness in an employee wellness program. Behavioral Medicine, 36, 113–122. 10.1080/08964289.2010.489080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anshel MH, & Kang M (2007). An outcome-based action study on changes in fitness, blood lipids, and exercise adherence, using the disconnected values (intervention) model. Behavioral Medicine, 33, 85–100. 10.3200/BMED.33.3.85-100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelhans BM, French SA, Pagoto SL, & Sherwood NE (2016). Managing temptation in obesity treatment: A neurobehavioral model of intervention strategies. Appetite, 96, 268–279. 10.1016/j.appet.2015.09.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au J, Sheehan E, Tsai N, Duncan GJ, Buschkuehl M, & Jaeggi SM (2015). Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory: a meta-analysis. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22, 366–377. 10.3758/s13423-014-0699-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer R (2010). Self-compassion as a mechanism of change in mindfulness- and acceptancebased treatments In Baer R (Ed.), Assessing mindfulness and acceptance processes in clients: Illuminating the theory and practice of change (pp. 135–150). Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A (2005). The primacy of self-regulation in health promotion. Applied Psychology, 54, 245–254. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00208.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bargh JA (1982). Attention and automaticity in the processing of self-relevant information. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 425–436. 10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard LK, & Curry JF (2011). Self-compassion: Conceptualizations, correlates, & interventions. Review of General Psychology, 15, 289–303. 10.1037/a0025754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF, Tugade MM, & Engle RW (2004). Individual differences in working memory capacity and dual-process theories of the mind. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 553–573. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF (1999). Self-Concept, self-esteem, and identity In Derlega V, Winstead B, & Jones W (Eds.), Personality: Contemporary theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 339–375). Chicago: Nelson-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF (2002). Ego depletion and self-control failure: An energy model of the self’s executive function. Self and Identity, 1, 129–136. 10.1080/152988602317319302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Aaker JL, & Garbinsky EN (2013). Some key differences between a happy life and a meaningful life. The Journal of Positive Psychology,8, 505–516. 10.1080/17439760.2013.830764 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bélanger-Gravel A, & Godin G (2010). Key beliefs for targeted interventions to increase physical activity in children: Analyzing data from an extended version of the theory of planned behavior. International Journal of Pediatrics, 2010, 893854 10.1155/2010/893854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit RG, Gilbert SJ, & Burgess PW (2011). A neural mechanism mediating the impact of episodic prospection on farsighted decisions. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 6771–6779. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6559-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman ET, Kahn LE, & Merchant JS (2014). Training-induced changes in inhibitory control network activity. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 149–157. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3564-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, & Baxter C (2011). Remember the future: Working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biological Psychiatry, 69, 260–265. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop DI, Weisgram ES, Holleque KM, Lund KE, & Wheeler-Anderson JR (2005). Identity development and alcohol consumption: Current and retrospective self-reports by college students. Journal of Adolescence, 28, 523–533. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni CA, Connors M, Devine CM, & Sobal J (2002). Who we are and how we eat: A qualitative study of identities in food choice. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34, 128–139. 10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60082–1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell KL, Trzesniewski KH, & Dweck CS (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78, 246–263. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannigan M, Stevenson RJ, & Francis H (2015). Thirst interoception its relationship to a Western-style diet. Physiology and Behavior, 139, 423–429 10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.11.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook AT, Garcia J, & Fleming MA (2008). The effects of multiple identities on psychological well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34, 1588–1600. 10.1177/0146167208324629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown KW, & Ryan RM (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822–848. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan AD, Magnan RE, Hooper AEC, Ciccolo JT, Marcus B, & Hutchison KE (2013). Colorado stride (COSTRIDE): Testing genetic and physiological moderators of response to an intervention to increase physical activity. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10, 139 10.1186/1479-5868-10-139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke PJ (2006). Identity change. Social Psychology Quarterly, 69, 81–96. 10.1177/019027250606900106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette JL, & Finkel EJ (2012). Buffering against weight gain following dieting setbacks: An implicit theory intervention. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 721–725. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.12.020 [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW (2010). Gratitude, gratitude intervention and subjective well-being among Chinese school teachers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 30, 139–153. 10.1080/01443410903493934 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NJ, & Squire LR (1980). Preserved learning and retention of pattern-analyzing skill in amnesia: Dissociation of knowing how and knowing that. Science, 210, 207–210. 10.1126/science.7414331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colcombe S, & Kramer AF (2003). Fitness effects on the cognitive function of older adults: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Science, 14, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.llll/1467-9280.t01-1-01430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colzato LS, Sellaro R, Samara I, Baas M, & Hommel B (2015). Meditation-induced states predict attentional control over time. Consciousness and Cognition, 37, 57–62. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colzato LS, van der Wel P, Sellaro R, & Hommel B (2016). A single bout of meditation biases cognitive control but not attentional focusing: Evidence from the global-local task. Consciousness and Cognition, 39, 1–7. https://doi.Org/10.1016/j.concog.2015.ll.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coursaris CK, & Liu M (2009). An analysis of social support exchanges in online HIV/AIDS self-help groups. Computers in Human Behavior, 25, 911–918. 10.1016/j.chb.2009.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD (2015). Biological pathways linking mindfulness with health In Brown KW, Creswell JD, & Ryan RM (Eds.), Handbook of mindfulness: Theory, research, and practice (pp. 426–440). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruijn GJ, & van den Putte B (2012). Exercise promotion: An integration of exercise self-identity, beliefs, intention, and behaviour. European Journal of Sport Science, 12, 354–366. 10.1080/17461391.2011.568631 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Visser RO, & Smith JA (2007). Alcohol consumption and masculine identity among young men. Psychology & Health, 22, 595–614. 10.1080/14768320600941772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deci EL, & Ryan RM (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond A, & Lee K (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 years old. Science, 333, 959–964. 10.1126/science.1204529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LM, & Aspinwall LG (2003). Emotion regulation across the life span: An integrative perspective emphasizing self-regulation, positive affect, and dyadic processes. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 125–156. 10.1023/A:1024521920068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Beck A, Felder JN, Boggs JM, Gallop R, & Segal ZV (2014). Webbased mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for reducing residual depressive symptoms: An open trial and quasi-experimental comparison to propensity score matched controls. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 63, 83–89. 10.1016/j.brat.2014.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality and development. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, & McCullough ME (2003). Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 377–389. 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbach A, & Shah JY (2006). Self-control in action: Implicit dispositions toward goals and away from temptations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 820–832. 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox N, & Ward KJ (2008). You are what you eat? Vegetarianism, health and identity. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 2585–2595. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankl VE (1997). Man’s search for meaning. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; (Original work published in 1946). [Google Scholar]

- Friese M, Hofmann W, & Wiers RW (2011). On taming horses and strengthening riders: Recent developments in research on interventions to improve self-control in health behaviors. Self and Identity, 10(3), 336–351. 10.1080/15298868.2010.536417 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM (2000). Executive frontal functions. Experimental Brain Research, 133, 66–70. 10.1007/s002210000401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuster JM (2008). The prefrontal cortex (4th ed.). London: Academic Press; 10.1016/B978-0-12-373644-4.X0001-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galla BM, & Duckworth AL (2015). More than resisting temptation: Beneficial habits mediate the relationship between self-control and positive life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 508–525. 10.1037/pspp0000026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant SN (2016). Mindfulness meditation practice and executive functioning: Breaking down the benefit. Consciousness and Cognition, 40, 116–130. 10.1016/j.concog.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]