Abstract

The structure of adolescents’ families, and thus parental forms, in the United States, have become more heterogeneous and fluid over the past several decades. These changes are due to increases in never-married, single parents, divorce, cohabitation, same-sex parenting, multi-partnered fertility, and co-residence with grandparents. We document current diversity and complexity in adolescents’ families as important context for rethinking future parenting theory and research. We also discuss how understandings of adolescents’ families are somewhat limited by current methods used to measure characteristics of families. We recommend social network and profile-based methods as alternatives to capturing key dimensions of family structure and processes. Understanding the diversity of households and families in which adolescents are raised can improve theory and research on parenting.

Even though a universal feature of adolescence is the growing autonomy that youth gain from parental oversight, parents, and the family context in general, continue to play a vital role in adolescents’ lives. The ways that adolescents are “parented,” including the provision of material and psychosocial resources, the quality of parent-child interactions and relationships, and levels of parental monitoring and scaffolding of youth have been consistently shown to matter for adolescents’ academic outcomes, subjective well-being, sexual behavior, substance use, delinquency, and other outcomes (DiClemente et al. 2001; Simons and Conger 2007; Steinberg 2001). Thus, social scientists, policy-makers, and practitioners continue to investigate and attempt to promote successful models for parenting adolescents.

For better or worse, many current investigations of the features and types of parenting that seem most beneficial for adolescents are based on theories of parenting and adolescence developed decades ago when family structures and their distribution in the population looked very different than they do today. Two cornerstones of contemporary theory, warmth and control, are concepts developed primarily between the 1930s and 1960s (Baldwin 1955; Baumrind 1967; Becker 1964; Sears, Maccoby, and Levin 1957; Symonds 1939) —a period in which about 90 percent of children under the age of 18 lived with two parents (Ruggles and Brower 2003). Studies of parenting have been increasingly recognizing how styles of parenting and their impact vary across cultures, socioeconomic strata, and family structures (e.g., Lareau 2003; Newman 2012; Sorkhabi and Mandara 2013; see also from this issue Jones, Loiselle, and Highlander; Lansford et al.; Murry; Stein et al.). Thus, to more accurately theorize, measure, and interpret findings regarding the parenting of adolescents, we must be clear about how families and households have changed over time, especially their increasingly dynamic and complex natures.

In this article, we review and summarize a wide body of literature showing how family forms and their prevalence have changed over the last several decades. After defining what we mean by “family” and “adolescence,” we describe the family households of adolescents, or the family members with whom they tend to live. We then discuss how family members might also be spread across other households, near and far. We then examine current practices in measuring the family contexts of adolescents and recommend innovations such as family network and profile methods. It is our goal to provide as detailed a picture as we can as to the range and distribution of adolescents’ family contexts in addition to suggesting methods for further enhancing our understanding of parenting contexts during adolescence.

Definitions

Family has always been a relatively elusive concept – definitions of family have changed over time, families themselves change over time, and members of families change (i.e., development and aging) (Harris 2008; Powell et al. 2010). For our purposes, we focus on all parents, siblings, and extended family members who play a role in adolescents’ lives. Family members may be related by blood, marriage, or other lasting bonds (e.g., cohabitation, guardianships, or adoption). Some family members reside in the same household as a given adolescent and some do not. Sometimes adolescents move between households following custody arrangements or other special circumstances. Thus, we start by describing change in the family households of adolescents and then broaden our focus to consider non-residential family members and their connections to adolescents over time.

Adolescence is a phase of life whose exact age bounds vary by expert or study, but are generally considered to encompass the second decade of life. This is roughly the time period from the onset of puberty to the beginning of adult roles (Steinberg 2016). We cite studies using a variety of age or grade ranges, including 12–17, 18–24, or grades 7–12, primarily due to the ages of participants. Further, many studies of family structure or stability aggregate data for all minors (ages 0–17). Thus, some of the data that we present apply to all youth, not just adolescents. Where we are able, we comment on the extent to which adolescents’ family forms are different than those of younger children.

The Households in Which Adolescents Live

As of 2016, 15 percent of all American households, and 23 percent of family households, contained at least one 12–17 year old (U.S. Census Bureau 2017a). Below we describe the changing prevalence of other family members in the households of adolescents. We discuss the parents, siblings, and grandparents with whom adolescents often live as well as homeless adolescents and adolescents who head their own households.

Parental Structure

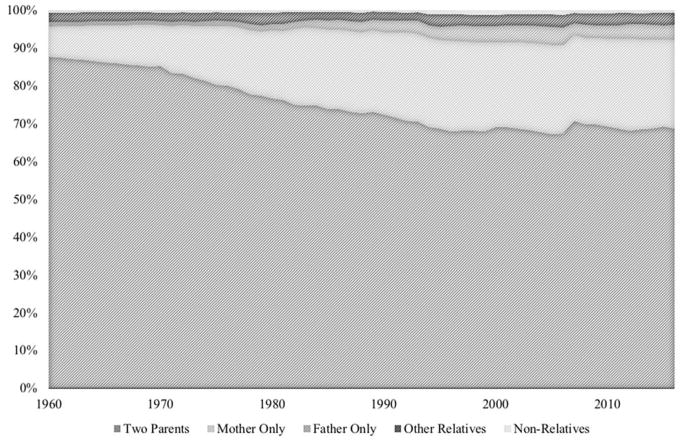

The nuclear family (a mother and father—usually married—and their biological child/ren) has long been assumed to be the Standard North American Family (SNAF) (Smith 1993) and continues to generally be the standard form to which all others are compared (Powell et al. 2010). As seen in Figure 1, as recently as 1960, about 88 percent of children (ages 0–17) lived with two parents (biological/adoptive, step, or cohabiting parents), eight percent lived with their mothers only, one percent lived with their fathers only, and three percent lived with other relatives or non-relatives. As of 2016, the percentage of children living with two parents is 69 percent -- a 22 percent decrease in 56 years. The shift was mostly due to single mother and single father families: now, 23 percent of children live with their mother only and four percent live with their fathers only. These numbers represent a 192 percent increase in mother-only families and 259 percent increase in father-only families (U.S. Census Bureau 2017e). Although father-only families have increased in number faster than mother-only families, mother-only families are still nearly six times more common.

Figure 1.

Living Arrangments of Children Under 18 Years Old, 1960–2016

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2017e)

Notes. The Census report does not have statistics for 1961–1967; for graphical purposes, a linear trend in each category is used between the data points for 1960 and 1968.

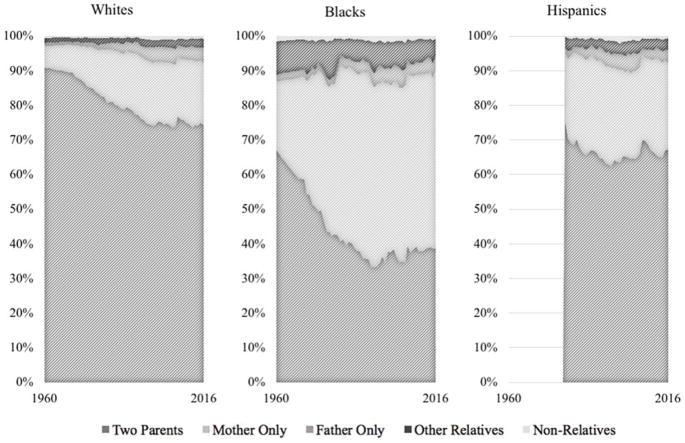

The increase in single parent households over time is primarily the result of two trends. First, divorce has been on the rise in the United States since the end of the Civil War, with a brief plateauing during the early 1980s (Kennedy and Ruggles 2014). Second, there has been a rise in the percentage of all births occurring to unmarried women, from four percent in 1940 to 41 percent in 2013 (Curtin, Ventura, and Martinez 2014). However, just over half (55 percent) of the births to single mothers, as of 2016, are to cohabiting parents (U.S. Census Bureau 2017d), and this has been increasing over time (Kennedy and Bumpass 2008). Thus, increasingly, one biological parent is not residing in the household, and if there are two parents, they may be cohabiting partners rather than marital ones. Because of racial and ethnic variation in rates of nonmarital births, cohabitation, and divorce (Barber, Yarger, and Gatny 2015; Curtin et al. 2014; Ruggles 1997; Smith, Morgan, and Koropeckyj-Cox 1996; Tucker and Mitchell-Kernan 1995), the increase in mother-only households and children living with other relatives has been particularly dramatic for Black and Hispanic youth, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Living Arrangments of Children Under 18 Years Old, by Race/Ethnicity, 1960–2016

Source: U.S. Census Bureau 2017g

Notes. The Census report does not have statistics for 1961–1967; for graphical purposes, a linear trend in each category is used between the data points for 1960 and 1968. Data for Hispanics begin in 1980 since they were not available before then for the subcategories shown here.

The way data were collected for many years, one can identify whether there are two adults living in a household and whether at least one of the adults is biologically or adoptively related to children in the household. However, further specification of the marital or even romantic status of the two adults or how both adults are related to each child is often impossible in data collected from before the mid-1990s. More contemporary data has the specificity that allows us to further distinguish households by the complexity of family relationships. For example, we create Table 1 below by adapting U.S. Census Bureau data based on the Current Population Survey in 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau 2017b). This table builds upon Figure 1 and allows us to hone in on three groups of adolescents: 9–11 year-olds, 12–14 year-olds, and 15–17 year-olds.

Table 1.

Living Arrangements of Children and Adolescents in the United States in 2016 (Numbers in Thousands)

| Total | Two Parents | One Parent | No Parent | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Mother only | Father only | ||||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Married | Unmarried | Married1 | Widowed | Divorced | Separated | Never Married |

Married1 | Widowed | Divorced | Separated | Never Married |

Grand- parent |

Other Relative |

Other Nonrelative |

Foster | ||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| All Children 0–17 | 73,745 | 47,724 | 2,955 | 878 | 606 | 5,131 | 2,389 | 8,219 | 160 | 174 | 1,164 | 366 | 1,142 | 1556 | 723 | 336 | 222 |

| Within Category % | 94% | 6% | 4% | 3% | 25% | 12% | 41% | 1% | 1% | 6% | 2% | 6% | 55% | 25% | 12% | 8% | |

| Global Category % | 65% | 4% | 1% | 1% | 7% | 3% | 11% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 0% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 69% | 27% | 4% | |||||||||||||||

| 9–11 Years | 12,401 | 8,123 | 353 | 151 | 102 | 1,015 | 436 | 1,260 | 28 | 30 | 212 | 64 | 174 | 294 | 111 | 31 | 17 |

| Within Category % | 96% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 29% | 13% | 36% | 1% | 1% | 6% | 2% | 5% | 65% | 25% | 7% | 4% | |

| Global Category % | 66% | 3% | 1% | 1% | 8% | 4% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 68% | 28% | 4% | |||||||||||||||

| 12–14 Years | 12,322 | 8,173 | 226 | 151 | 129 | 1,099 | 458 | 1,075 | 32 | 43 | 251 | 67 | 166 | 260 | 121 | 44 | 27 |

| Within Category % | 97% | 3% | 4% | 4% | 32% | 13% | 31% | 1% | 1% | 7% | 2% | 5% | 58% | 27% | 10% | 6% | |

| Global Category % | 66% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 9% | 4% | 9% | 0% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 1% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0% | |

| 68% | 28% | 4% | |||||||||||||||

| 15–17 Years | 12,780 | 8,031 | 202 | 180 | 239 | 1,432 | 437 | 919 | 37 | 65 | 401 | 47 | 133 | 300 | 214 | 116 | 27 |

| Within Category % | 98% | 2% | 5% | 6% | 37% | 11% | 24% | 1% | 2% | 10% | 1% | 3% | 46% | 33% | 18% | 4% | |

| Global Category % | 63% | 2% | 1% | 2% | 11% | 3% | 7% | 0% | 1% | 3% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 1% | 0% | |

| 64%ab | 30%ab | 5%ab | |||||||||||||||

Source. U.S. Census Bureau (2017b).

Spouse absent

Estimates different at 95% confidence from 9–11 year-olds

Estimates different at 95% confidence from 12–14 year-olds

Note: Calculations of significant differences were made following the source documentation instructions.

Overall, 9–17 year-olds have very similar living arrangements to 0–17 year-olds. About 68 percent of 9–14 year-olds and 64 percent of 15–17 year-olds live with two parents as compared to 69 percent of all 0–17 year-olds. Twenty-eight percent of 9–14 year-olds and 30 percent of 15–17 year-olds live with one parent, compared to 27 percent of 0–18 year-olds. And, four and five percent, respectively, do not reside with a parent compared to four percent of those aged 0–17. Not surprisingly, the older adolescents (whose parents have had more time to change living situations or family structure) are slightly more likely than the younger children to live in single parent, other relative, or nonrelative homes.

For the 64–68 percent of adolescents living with two parents, the vast majority of them (about 96–98 percent) live with married biological or adoptive parents. For the 28–30 percent of adolescents who live with one parent, the vast majority of them live with their mothers; specifically, 85 percent of 9–11 year-olds, 84 percent of 12–14 year-olds, and 82 percent of 15–17 year-olds who live with a single parent live with their mother. Conversely, between 15 and 18 percent of adolescents in a single-parent home live with their single father. For all single parent categories, the largest groups, by far, are never married mothers and divorced mothers. Living with a separated mother is the third most common single parent living arrangement, which describes 11–13 percent of adolescents. Lastly, for the 4 to 5 percent of adolescents who do not live with either parent, the most common arrangement is to live with a grandparent, though this likelihood decreases with age: 65 percent of 9–11 year-olds, 58 percent of 12–14 year-olds, and 46 percent of 15–17 year-olds living without parents are living with a grandparent. The next most common arrangements for those living without either parent are living with another relative (25 to 33 percent), living with a nonrelative (7 to 18 percent), and living in foster care (4 to 6 percent).

Given the family change and diversity we have documented, theory and research about the parenting of adolescents must take into account that both parents and children are increasingly experiencing transitions in who lives with them that may induce emotional and financial stress or raise real or perceived stigma (Cherlin 2010; McLanahan and Sandefur 1994; Pryor 2004). This changes resources for parenting as well as the kinds of issues for which adolescents need support. Further, parents are increasingly spread across different households, which raises issues of how parenting is shared (or not) inside and outside an adolescent’s primary residence.

Same-Sex Parents

There have also been changes over time in the percentage of children living with two parents of the same sex. Vespa, Lewis, and Kreider (2013) find that about 16 percent of same-sex cohabiting or married couples in the United States have biological, adoptive, or stepchildren under age 18 living with them as of 2012 (11 percent of male couples and 22 percent of female couples). This is higher than the 1990 rate of 13 percent, but is lower than estimates between 2000 and 2008, which fluctuated between 17 and 19 percent (Gates 2012). With current estimates of same-sex couples from the American Community Survey at about 860,000 for 2015 (U.S. Census Bureau 2017c), if 15–20 percent of them have one child, then between 129,000–172,000 youth are currently living with co-resident same-sex parents.

One noteworthy trend among same-sex couples is the proportional increases in adoptive children compared to biological children, which may be due to LGBT individuals coming out earlier in life and thus becoming less likely to have children while in relationships with opposite sex partners (Gates 2012). The global increase in assisted reproductive techniques (ART)(Dyer et al. 2016), in tandem with medical advances and fertility clinics welcoming same-sex couples, is also increasing the ability for same-sex individuals (whether coupled or not) to become parents (Greenfeld and Seli 2016; Grover et al. 2013). With the number of same-sex couples growing each year between 2008–2015 (U.S. Census Bureau 2017c), the proportion of adolescents living with same-sex parents has grown.

Theory and research on parenting often consider mothers’ and fathers’ roles in providing warmth and control, and sometimes claim unique and essential roles of both, but evidence suggests the gender composition of parents has minimal influence on children’s psychological and social outcomes (Biblarz and Stacey 2010). However, parents’ gender is correlated with how parents and children get along, parents’ emphasis on gender conformity, and parenting skills, so theory and research on parenting should continue to examine the gender composition of parents as a factor shaping parenting and its outcomes (Bos, van Balen, and van den Boom 2007; Golombok, Tasker, and Murray 1997).

Although social acceptance of same-sex couples marrying and having children is growing, there is still potential for parents and children in these families to experience stigma and discrimination (Gates 2015). As Jones et al. (this volume), Mills-Koonce, Rehder, and McCurdy (this volume), Murry (this volume), and Stein et al. (this volume) all point out, in families facing real and perceived stigma, parents face the challenge of building a positive sense of oneself and one’s family in addition to helping children understand and persevere in these social dynamics.

Foster and Adoptive Parents

In September of 2015, about 172,000 adolescents ages 10–20 were living in foster care; during the same year, 92,000 adolescents entered foster care and 99,000 exited foster care (Children’s Bureau 2016). Among youth ages 0–20 who exited, 51 percent were reunified with their parents or primary caretakers and 22 percent were adopted (Children’s Bureau 2016). In published statistics, adopted children are typically included with those who are biologically related to parents. However, Child Trends (2012) uses more detailed survey data on adoption from 2007 to show that two percent of all children (ages 0–17) live with at least one adoptive parent and no biological parents. Of those, 37 percent were in foster care at some point, 38 percent were adopted through private domestic adoption, and 25 percent were adopted internationally. One more recent estimate suggests that approximately seven percent of children ages 0–17 in the United States live with at least one adoptive parent, but this includes those adopted by a step-parent, unlike the prior estimate (Kreider and Lofquist 2014).

Fostering and adopting children raises all kinds of unique parenting issues. Adolescent foster or adoptive children have often experienced prior neglect, abuse, or abandonment, making them less trusting of parent figures in general (Pryor 2004). Adoptive parents and children sometimes differ notably in culture or appearance, posing potential issues for how they or others view their relationships (Pryor 2004). Foster parents may be managing uncertainty about how long a child/ren will be in their home and what kinds of bonds to forge (Pryor 2004). Birth parents may still be in contact and involved with their children, raising issues of how to manage co-parenting with foster parents. In other words, there are additional factors at play in foster or adoptive parenting, highlighting key roles of parents and how those are modified across family structure.

Siblings

Another important feature of family or household context, when it comes to parenting, is how many and what types of siblings live with adolescents on average. Using data from 2009, Kreider and Ellis (2011) find that about 58 million children live with siblings (78 percent). Of these children, the majority (82 percent) live with only full siblings, 14 percent live with a halfsibling, 2 percent live with a stepsibling, and 2 percent live with an adopted sibling. About 22 percent of all youth have no siblings, 38 percent have one sibling, 24 percent have two siblings, 11 percent have three siblings, and 5 percent have four or more siblings.

Siblings function as both sources of intimacy and conflict for adolescents (Lempers and Clark-Lempers 1992), which is largely a continuation of their sibling relationships from childhood (Dunn, Slomkowski, and Beardsall 1994). Intimacy remains stable among same-sex sibling dyads throughout adolescence, but increases for mixed-sex dyads, while conflict appears to taper off during middle to late adolescence (Kim et al. 2006). Theory and research on parenting often focuses on one dyad despite there often being other children in the family. The number of siblings has implications for how resources (material and emotional) are shared which is directly related to parenting (Blake 1981). This takes on even more complexity in blended families with a combination of sibling types.

Grandparents

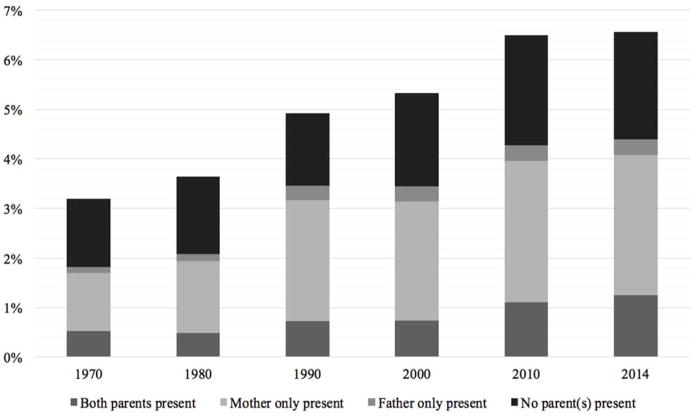

Table 1, discussed earlier, shows that about two percent of all children live without parents but with a grandparent. Figure 3, below, adds to this statistic by showing trends over time in children living with grandparents, in any combination with or without parents (U.S. Census Bureau 2017f). The figure shows a doubling in the percent of children who live with a grandparent between 1980 and 2014, from 3.2 percent to 6.6 percent. Notably, about two-thirds of children living with a grandparent are also living with one of their parents (typically the mother). These are called multigenerational households, or households containing three or more generations, and have been shown elsewhere to also vary by race – with Hispanics and blacks having the highest rates (8 percent of households), followed by Asians (6 percent) and whites (4 percent)(Vespa et al. 2013). Theories and research on grandparents as parents should factor in how the middle generation (biological parents) fit into the family and parenting, as well as how life course stages and developmental compatibility between family members affect grandparents’ parenting styles (Burton, Dilworth-Anderson, and Merriwether-deVries 1995; Kemp 2007).

Figure 3.

Children Under 18 Living with Grandparents as Percentage of All Children Under 18

Source: U.S. Census Bureau (2017f)

Homeless adolescents

Although rare, another important family form to address for adolescents is homelessness. About seven percent of the homeless population are unaccompanied children (under 18 years old) and youth (18–24), and about 37,000 children and youth were experiencing homelessness during a point-in-time estimate in 2015 (National Alliance to End Homelessness 2016). However, this is likely an underestimate, since enumeration techniques are not as effective for youth, and youth often do not congregate in the same areas as those in older age groups. Indeed, survey estimates of youth who experience at least one night of homelessness in a given year range from about 1 million to 1.7 million (Fernandes-Alcantara 2013). Homelessness is surely a taxing and stigmatizing experience for adolescents and their parents, further what parents can or cannot provide adolescents.

Adolescents as parents

Births to adolescents are declining and reached an all-time low in 2015 (Martin et al. 2017), predominately due to improved contraceptive usage (Lindberg, Santelli, and Desai 2016), though many adolescents do become parents – usually unintentionally. Finer and Zolna (2014) show that, as of 2008, 91 percent of pregnancies among 15–17 year-olds and 77 percent of pregnancies among 18–19 year-olds are unintended. Nevertheless, in 2015, adolescent females ages 15–19 had about 230,000 births, with about one percent of 15–17 year-old girls giving birth and four percent of 18–19 year-old girls (Martin et al. 2017). Adolescent parents and their children face a number of obstacles and are at an increased risk for a host of negative outcomes, yet intervention programs have the potential to mitigate these (see Pinzon et al. (2012) for a comprehensive review on both outcomes of adolescent parenting and interventions). The renegotiation of parenting when one’s own adolescent becomes a parent, and may need new kinds of support and/or more independence, likely presents unique challenges.

Household Transitions Experience by Adolescents

What we have presented to this point are snapshots of what the households of children or adolescents look like across the population in certain years. Another way of understanding variance in the family contexts of youth is to consider how stable these contexts are over time. Several studies have conceptualized family instability as the number of transitions households experience (Cavanagh 2008; Fomby, Mollborn, and Sennott 2010), and increasingly studies are comparing particular types of transitions or the timing of those transitions and their associations with child well-being (Lee and McLanahan 2015). When households lose or gain parents or siblings, it is likely to affect parenting resources and styles (Pryor 2004).

Parental Transitions

Brown (2006) uses data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of youth in grades 7–11 during the 1994–95 school year to report the frequency of family transitions within one year of adolescence. Ninety-three percent of these youth experienced no household transitions in that year; specifically, 62 percent of adolescents in this sample lived with two-biological parents throughout the year (married or cohabiting), 12 percent remained in a previously formed stepfamily, and 19 percent remained with a single mother. Seven percent of adolescents experienced a household or family transition during that year: four percent moved from a two-parent family to a single-mother family, three percent went from a single-mother household to a two-parent household (either cohabiting or married), and one percent experienced a transition from one two-parent household type to another (usually from a cohabiting stepfamily to a married stepfamily). Laughlin (2014) shows that 12 percent of children ages 12 to 17 years old in 2011 had experienced a change in the number of residential parents or parent’s partners in the home in the past four years.

Considering the trajectories of household structure throughout all of childhood and adolescence, Mitchell (2013) uses data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Mother’s and Children sample to estimate latent classes of children’s long-term living arrangements for youth who were 14–19 years old in 2006. She finds five general pathways: 1) consistently living with two biological parents from birth (55 percent), long-term living with a single mother (18 percent), living with married biological parents who divorce (12 percent), gaining a stepfather through marriage (11 percent), and being born to cohabiting parents who later married or broke up (4 percent). Although these five pathways do not encompass the experiences of all adolescents, they give a good sense of the most common experiences over time.

Custody and Living Arrangements

Using data from the 2009 American Community Survey, Elliot and Simmons (2011) show that about 18 percent of men and 44 percent of women with a divorce in the past year were living with children under 18. This equates to over a million children experiencing a divorce in the past year, with the median age of these children around 9.8 – about the onset of adolescence. Following many of these divorces will be custody arrangements that inevitably change the living situation of the adolescents involved. Custody arrangements have changed tremendously over the past few centuries (see DiFonzo (2014) for a review), but the most recent trend (from the mid-1980s to present) has been a substantial decline in sole custody awards to mothers coupled with a dramatic increase in shared custody awards (Cancian et al. 2014). Estimates of custody awards from 2008, based on a very large sample of court records in Wisconsin, suggest that about 42 percent of awards are now for sole mother custody, 45 percent are for shared custody, nine percent are sole father custody, and the rest are split custody (Cancian et al. 2014).

Other Residential Transitions

The period between late adolescence and early adulthood, often called “emerging adulthood” (Arnett 2004), is marked by numerous transitions and identity exploration. For example, about 69 percent of high school graduates begin college immediately following their high school completion (McFarland et al. 2017). This is often accompanied by a residential move, as about half of college students live apart from their parents, which is split about evenly between those with and without roommates (Sallie Mae 2017). Thus, late adolescence is a period of home-leaving for many but not necessarily independent living for most. For adolescents who do not go on to college, many of them begin some sort of paid work, establish their own household, or start families (DeLuca, Clampet-Lundquist, and Edin 2016; Mitchell and Syed 2015), often with difficulties in the labor market due to having no more than a high school degree (Rosenbaum 2001). Especially among disadvantaged youth, the typical explorations of emerging adulthood may not be possible (Côté 2014); these youth often face an expedited path to adulthood that involves forgoing postsecondary education and becoming independent as quickly as possible (DeLuca et al. 2016).

Interestingly, the percentage of older adolescents and young adults who return to their parents’ home after leaving, who are sometimes referred to as “boomerang kids,” has been increasing over time in the United States (Goldscheider and Goldscheider 1999). In fact, recent estimates show that living with parents is the most common living situation for 18 to 34 year-olds, at 32 percent (Fry 2016). The reaction of parents to this phenomenon varies, but there is an expectation among parents in the United States that their live-in adult children are working toward independence (Newman 2012).

In general, the increasing fluidity and change in the households and family structures of adolescents signals a growing need for theories and research on the parenting of adolescents to not just expand to consider different family forms, but to also recognize family instability as its own context for parenting (Pryor 2004). As the life course perspective recognizes (Elder 1998), young people (and their parents) carry forward their early life experiences, and so a divorced and single mother might not just be parenting with reduced time and resources in the present, but she and her child/ren are also living with the experiences of the past, such as how well was the divorce handled by all. Due to distress and disruption, parenting is often temporarily compromised during and immediately following a transition in family structure (Capaldi and Patterson 1991; DeGarmo and Forgatch 1999).

Nonresidential Family Members of Adolescents

Nonresident Fathers

Due to rising rates of births to single mothers and divorce, as well as the fragility of cohabiting unions, many children have nonresident fathers for some or all of adolescence. In Figure 1, we show that about 27 percent of youth live away from their father, with the majority of them (23 percent of youth) living with a single mother. Rates of single motherhood also vary substantially by race, with 18 percent of white children, 52 percent of black children, and 25 percent of Hispanic children living with a single mother as of 2016 (U.S. Census Bureau 2017g). Nonresident fathers, as a group, substantially increased involvement in their children’s lives between 1976 and 2002, with more fathers seeing their children weekly and fewer fathers reporting no contact at all (Amato, Meyers, and Emery 2009). Cheadle, Amato, and King (2010) add nuance to this finding and identify four latent classes of nonresident father involvement: 38 percent of fathers have high and stable involvement over time, 32 percent have low and stable involvement, 23 percent have high involvement initially but decrease it over time, and 8 percent have low involvement initially but increase it over time.

Nonresident Mothers

Although uncommon, some children spend years not living with their biological or adoptive mothers. In Figure 1 we show that about 8 percent of youth live away from their mother, with about half of these youth (4 percent) residing with single fathers. Table 1 further shows that this percentage is about the same for 9–11 year-olds, 12–14 year-olds, and 15–17 year-olds. The economic situation of nonresident mothers tends to be worse, on average, than that of nonresident fathers, as they earn less money and are less likely to be working (Sousa and Sorensen 2006). However, nonresident mothers tend to spend more time with their children than nonresident fathers (Gunnoe 1993). Because of the historical norm that mothers are more likely to get custody, women who lose or have less custody than fathers probably face stigma that will affect their parenting and create a need for children to also be parented in ways that helps them prepare for potential discrimination. Being a nonresident parent, father or mother, introduces challenges to spending time with one’s children to parent, and may remove one from involvement in important decisions or parenting tasks (Pryor 2004).

Multi-Partner Fertility

Adults have become increasingly like to have children with more than one partner, often called multi-partner fertility (MPF). Recent estimates suggest about 10 percent of adults have MPF (Monte 2017). This means many adolescents have siblings (with full, partial, or no biological ties) with whom they may be maintaining relationships, potentially across residences. Once again, because surveys usually only collect information on household members, we know little about how many adolescents have siblings of any kind residing in other households, nor the quality, benefits, or consequences of those relationships. It is likely that the presence of siblings across other households stretches resources such that adolescents in these situations may get, on average, less time and support from their parents (Meyer and Cancian 2012; Tach, Mincy, and Edin 2010). There may also be tension between different parent figures or parents and children that interferes with or complicates the parenting of adolescents (Pryor 2004).

Extended Family

Adolescents are often close to and exchange support with extended family members, including grandparents, aunts and uncles, or cousins (Sterrett et al. 2011). Increasing gains in longevity translate to a higher likelihood that adolescents know their grandparents longer than in previous generations (Kemp 2007). The closer grandparents live to their grandchildren, the more emotionally close they are, but grandparents who live far away often use electronic forms of communication, and studies show that frequent phone or email conversations build closeness (Harwood 2000). Kinds of support that grandparents provide include emotional support, peace-keeping, “straight talking,” and sharing family history (Soliz 2008).

Although research is increasingly incorporating the roles of nonresidential family members, and especially parental figures, in the lives of adolescents (Jones et al. 2007), more could be done to examine forms of support (or conflict) provided to adolescents and residential parent figures. Past theories and methods have relied heavily on the household context and often assumed two biological parents are involved, but now the socialization and raising of adolescents falls to a larger network of adults. The better we understand the forms family configurations and exchanges take, the better we can tailor theory, research, and practice or interventions to fit families as they are.

Measuring Family Contexts for the Parenting of Adolescents

In addition to data on families collected through the U.S. Census, there are a number of high quality, nationally representative sample surveys, many of which are used in the research reported above, that make the description of adolescent family contexts possible. What we know about the family contexts in which adolescents live depends on how we collect data and “measure” family life. Although we learn a great deal from existing data, in some ways, the designs of these studies limit our ability to fully understand certain aspects of adolescents’ families.

Most existing surveys mainly collect information about family members who reside together in households. For some surveys, like the Current Population Survey or the American Community Survey, households are a sampling unit, and one member of the household reports on all others. The quality of those data for understanding family structures within households depends heavily on a well-designed household roster or matrix that lists all members of a household and carefully notes the relationships between all members. When data do not include complete information about the relations between each household member and all other household members, we are restricted from knowing important family characteristics, like whether a married or cohabiting couple in a household are biological, adoptive, or step-parents to the child/ren in the household (Manning, Brown, and Stykes 2014; O’Hara, Shattuck, and Goerge 2017). Further, data often lack the detail necessary to determine whether co-resident children are full, half, or unrelated siblings (McHale, Updegraff, and Whiteman 2012).

For many years, household surveys such as U.S. Census forms (up until 1980) required the “household head” to be the household respondent. This was typically a man. In 1980, the Census changed procedure, allowing any “householder” to be the respondent, and this would include men or women who jointly own or rent the home. The proportion of reporting householders who are women has increased over time (Ruggles and Brower 2003). On the other hand, in many more recently established survey studies, such as the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 Children and Young Adults, or the National Study of Youth and Religion, mothers are the primary reporting parent and source of information on other members of the household. Household- or child-focused studies are often designed to have mothers (whenever possible) as reporters because of long-standing assumptions about their chief importance in and knowledge of children’s development and family processes (Schaeffer, Seltzer, and Dykema 1998). It has also proved easier and less costly, historically, to locate and recruit women or mothers for survey research (Braver and Bay 1992; Schaeffer et al. 1998). Despite the benefits of relying on mothers for family information, only having reports from one parent limits the information we have about adolescents and their families.

Regardless of how residential family members and their relationships to each other are documented, household-based surveys are also limited by the extent to which they can shed light on family members who reside outside the focal household (Manning et al. 2014). This includes nonresidential parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts and uncles, cousins, or even adults who are not blood relatives but play a central role in parenting adolescents. Some studies, like the National Study of Families and Households, involve interviews with multiple parents, including follow ups with parents who leave the household. Very few nationally representative studies of youth or families collect data from nonresidential parents from the start. One exception is the Fragile Families Study (Reichman et al. 2001), in which fathers are interviewed at all the same time points as mothers, even if they live apart. It is undoubtedly expensive to fully delineate and measure adolescents’ families, especially from the perspective of multiple family members, but the value in doing so justifies consideration of how we might more creatively approach the collection of data on adolescents’ family contexts.

A handful of other previously identified factors may also bias our understandings of adolescents or young adults’ living arrangements when young people themselves are the sampling units. For example, when youth are sampled from schools, youth who are not in school either because of dropping out or being homeschooled may be missing from the sampling frame (Johnston and O’Malley 1985). Thus, the types of families or households those youth tend to have could be underrepresented in the data. Further, some studies restrict residents of institutions from being in the sampling frame, meaning that when focusing on youth, those who live on a college campus or are incarcerated (and their family situations) are underrepresented. And, some studies restrict their samples to college students, making findings less generalizable to the whole population of late adolescents or young adults. (Côté 2014; Mitchell and Syed 2015).

Future Directions

Family Networks

One alternative that could address limitations inherent in the household-centric design of surveys is the application of social network approaches and methods to the collection of data on family members (Bernardi 2011; Widmer 2010). These methods have been primarily used for adults’ social networks to date, and to collect information on the most influential people in their lives. Widmer (2010) argues families are best defined as configurations created out of the interdependencies between family members. Using a social network approach to conceptualize families allows researchers to put adolescents at the center of a network of family members, considering the social, psychological, biological, and geographic distances of those in the web of family. It also makes it possible to assess the type and quality of ties between members of an adolescent’s family network, including the social capital available (Widmer 2010). Further, one could consider the support networks (family or wider) of multiple family members and the extent to which they overlap or leave certain family members isolated (Bernardi 2011).

The conceptualization of adolescents’ families as social networks suggests new forms of data collection as well (Bernardi 2011; Widmer 2010). In survey studies designed to understand the role of family and family members in the lives of adolescents, rather than a standard household roster,, adolescents might be asked to complete a sociogram or network diagram that systematically elicits reports of the important family members in an adolescent’s life (Widmer, Aeby, and Sapin 2013). “Important” could be defined according to key theories or research questions. For example, studies might focus on listing and describing family ties based on levels of closeness, social support, financial support, or time spent together. Further, adolescents could report perceptions of how close each of these family members is to every other family member, so that standard network measures, such as density or centrality, could be applied to understanding family characteristics. Other family members could also become participants in the study and provide their own assessment of adolescents’ family networks and the ties involved.

In longitudinal studies, the repeated mapping of adolescents’ family networks could provide rich data for shifts over time in influential family members, family relationships, and family living arrangements. This dynamic approach allows for assessing levels of stability or instability in family networks as well as various trajectories in network change. Widmer (2010) demonstrates how change in family configurations in the short and long term are related to psychological well-being.

Using a social network approach in measuring the family structures, ties, and interactions of adolescents could address several issues raised earlier in the paper. For one, this measurement strategy could do a better job of documenting family relations across households, not limiting researchers to the context of one household. Second, depending on how data about family networks are collected, this approach could do a better job of characterizing types and features of family relationships (Widmer 2010). With a variety of studies indicating that levels of warmth and control provided by parents are more predictive of youth well-being than the family structure/s in which they have lived (Arnold et al. 2017; Demo and Acock 1996; Lansford et al. 2001; Phillips 2012), it is important that we understand how family configurations improve or challenge the ability of parents to provide high quality parenting (Pryor 2004; Murry this issue).

Family Profiles

Another alternative for measuring the family contexts in which adolescents live is to use cluster analysis or latent class methods to suggest “types” or “profiles” of families. Common types of families would be identified by a set of indicators of family structure such as number and type of parent figures, sibling types and living arrangements, different residential custody arrangements, multigenerational living, and more. Family configurations could represent families at one moment in time or a set of experiences across time.

Research on the implications of family structure for children and adolescents often focuses on one part of family structure at a time, like whether there are one or two parents in the home, or the impact of a remarriage on adolescents. However, the relationship status or transitions experienced by parents might be different based on whether an adolescent has siblings or not and how many. Manning et al. (2014) and others describe the multifaceted nature of families as “complexity,” and they recommend an approach that documents types of parent figures as well as siblings. Methods such as latent class analysis could achieve this.

Indicators of dynamic living arrangements such as shared residential custody could be included in analyses. One could represent family transitions over time such as having ever lived with a single parent, a step-parent (married or cohabiting), having had a biological-, half-, or step-sibling, having ever lived with a grandparent, having experienced a parental dissolution, having moved from home, or ever having returned to home.

The use of social network or configurational methods has the potential to transform the study of adolescents’ family contexts and parenting by providing better coverage of family members and processes. Rather than having to rely on certain segments of what adolescents might define as their family, or only consider one aspect of family structure at a time, these methods allow the complexity of families to be more fully captured. Moreover, with network or family profile methods, measures of the quality or content of family interactions could be included. This might include family experiences, such as death, severe or chronic health issues, incarceration, or deportation of a family member as factors that define a family and present new issues for parenting adolescents.

Conclusions

Understanding forms of family in which adolescents come of age and their impact is challenging on a number of fronts. There are many dynamics at play. The definition of family has been changing over time, families experience changes of members across time, and parents and adolescents themselves are developing through time. Further, there are key measurement challenges, including the extent to which we focus on household members as family, who we ask to report on family structure and dynamics, and how to best capture changes in these very complex processes over time.

Despite these challenges, we do have a sense of the range and prevalence of family forms and how these have changed over time. Adolescents increasingly live in single-parent, step-parent, and no-biological-parent homes. Having step-siblings or half-siblings in the home or in other homes is more common. Grandparents are increasingly present in adolescents’ homes and lives. Older adolescents or young adults are more likely to return to their parents’ homes for a period of time. Further, the number of changes in living arrangements families experience has increased. Because so much about adolescents’ families has changed since the middle of the 20th century when foundational theories of parenting were developed, it is important we consider how newer contexts for parenting might alter or expand theory or research on parenting adolescents.

The many aspects of family change experienced in the United States over the past few decades share a common set of implications for parenting adolescents. Different forms and increasing change within families involves relationship transitions for both parents and children, can be stigmatizing for parents and children, might increase the number of parent figures needing to coordinate support and guidance for an adolescent, and can be a source of difference or distance between parents and children.

Relationship transitions, such as separation or divorce, are associated with more parental stress and harsher parenting in mothers (Beck et al. 2010; Cooper et al. 2009). Amato (2004:32) contends that while there are many risk factors associated with divorce, “disruptions in parent-child relationships have the greatest potential to affect children negatively.” Families with “boomerang” adolescents, who have moved out and then return, may have challenges negotiating appropriate autonomy-granting and independence-building (Newman 2012). Thus, the transitions involved in creating increasingly new and different family forms raise challenges to parenting adolescents. Classic theories highlighting the importance of warmth and control (e.g., Baldwin 1955; Baumrind 1967; Becker 1964; Sears et al. 1957; Symonds 1939) can be enhanced in thinking about ways parents can adequately provide support to adolescents during times of transition and in new family forms.

These considerations all point to an increased need for cooperation, negotiation, and understanding among parents, partners, and children (Amato 2004). Theory and research should continue to address the extent to which relationship transitions limit parents’ abilities to provide optimal support and monitoring, and whether, at the same time, adolescents in these situations might need more support and monitoring. Parents themselves should and often do acknowledge the need to process these transitions in as healthy a manner as possible to protect their and their adolescents’ well-being. For example, authoritative parenting, in which parents are warm, involved, and supportive of their adolescent’s autonomy and decision-making, yet are clear and firm about their boundaries and expectations, can be successful across multiple family types and cultures (Baumrind 1971; Sorkhabi and Mandara 2013; Steinberg 2001). Other parents and family members who are not be dealing with family transitions might consider how they can best support those parents who are, in the interest of helping families emerge from transitions.

When family forms are changing so fast, and society holds strong to nostalgia for the idealize family of the past (Coontz 1992), there is great potential for suspicion and condemnation of non-nuclear families, same-sex parent families, or foster/adoptive families that stem from a failure or inadequacy on the part of biological parents. Thus, parents and adolescents in these family forms, with these experiences and identities, face personal challenges that arise from marginalization, and they worry about and attend to each other’s harm from such discrimination. These processes are also discussed by Murry (this issue) and are a potential context in which to consider what optimal parenting of adolescents involves.

Parents in these often-judged families can benefit from being aware and educated about the risk of experiencing real and perceived stigma. If parents are presented with data to show the relative normality of their experiences today and the questionable reasoning in assuming a golden age of families in the past (Coontz 1992), they may gain confidence as parents, allowing them to provide the support and monitoring that seems more essential to adolescents than family structure in and of itself. Likewise, adolescents who face potential stigma because of their family experiences can be taught how to understand and cope with it. Finally, parents and adolescents who have consistently been a part of a nuclear, biological, heterosexual parent family should also recognize that different family forms are not necessarily inferior family forms. They should connect with different kinds of families to learn how their lives are more similar than they know. As everyone recognizes the dangers in assuming that family structure equates to family quality, the risk of stigma for parents and children in new family forms will decline.

Complex families with multiple parent figures, including grandparents, other relatives, non-residential parents, and foster parents, have increased potential for conflicts about parenting and greater challenges negotiating a unified and beneficial parenting approach (Pryor 2004). As a greater number of parent figures become involved in adolescents’ lives, parenting behaviors become responsive to the desires and circumstances of a range of parent types, new children, and others. These complex family networks will affect access to, and relationships with, all of a parent’s children (Meyer and Cancian 2012; Tach et al. 2010).

Finally, with greater heterogeneity and change over time in the number of parent figures involved in an adolescents lives comes the potential for greater distance between parents and adolescent along a number of lines. Step-parents, foster or adoptive parents, or even parents who had children via ART, and their adolescent children, often have issues surrounding the lack of biological connection between them and/or negotiating how to establish strong bonds and encourage their connection with their biological parents (if they are still involved) (Pryor 2004). Grandparents who parent may share biological ties with adolescents, but their age difference may pose challenges to parenting. Non-resident mothers or fathers may be or feel less involved in key decisions or socialization processes due to their limits on time together (Pryor 2004).

We have covered a variety of aspects of family structure and their implications for the contemporary study of parenting adolescents. Yet, there remain other ways that families differ that might impact parenting and should also be studied further. We focused on permanent relationship and living arrangement change in our survey of the literature, but families can become separated in temporary (but often long-term) ways that hold many of the same implications for how parenting might unfold. For example, military families deal with frequent moves as well as deployment of at least one parent (Arnold et al. 2017). There has been a massive increase in the likelihood an adolescent will be separated from a parent who is incarcerated, presenting its own unique challenges (Johnson and Easterling 2012; Murphey and Cooper 2015). Deportation is increasingly an issue for immigrant families in the United States, and refuges may have family members left in their country of origin. There are also family experiences that do not change the structure of family, but shift the balance of resources or parenting. This could include parent or child physical or mental health issues, unemployment, or death of a family member. In general, the better we are at considering the range of family forms and experiences in our measures and models, the more advice can be tailored to specific parenting contexts for adolescents.

In addition to incorporating new family forms and their implications into our theorizing and research on parenting adolescents, we must also advance our methods of measuring families. Because of the challenges in grasping all complexities of adolescents’ families, research should continue to pursue and implement new ways to conceptualize and measure family forms and processes. Social network methods bring a flexibility and comprehensiveness to the measurement of significant family ties, as well as allowing the study of multiple family members’ perspectives. Profile or clustering methods permit studying unique configurations of certain aspects of family structure and the quality of interactions.

In the absence of these alternate forms of data on families, we recommend that studies focused on or controlling for the role of family structure in parenting theorize the appropriate dimensions of family context to a given topic, and include as many of those as possible. This would include measures of number and type of parents, siblings, and extended family members and involvement of non-residential parent figures in an adolescent’s life. We also recommend modeling interactions between parenting styles and family structure, so we can better evaluate the extent to which the importance of key constructs like emotional support or behavioral monitoring varies by family context.

More fully recognizing the contemporary range of family structures and the unique issues involved with each greatly improves the odds that we are more accurately theorizing, measuring, and analyzing best practices for parenting adolescents. In turn, the public can also be better informed about the growing normality of non-nuclear, impermanent family structures, possibly lowering stigma of certain families and raising parents’ and adolescents’ confidence in maintaining strong bonds and successfully preparing for the transition to adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This research received support from the Population Research Training grant (T32 HD007168) and the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2C HD050924) awarded to the Carolina Population Center at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Contributor Information

Lisa D. Pearce, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

George M. Hayward, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Laurie Chassin, Arizona State University

Patrick J. Curran, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- Amato Paul R. Parenting Through Family Transitions. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 2004;(23):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Amato Paul R, Meyers Catherine E, Emery Robert E. Changes in Nonresident Father-Child Contact from 1976 to 2002. Family Relations. 2009;58(1):41–53. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett Jeffrey. Emerging Adulthood: The Winding Road from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold Amy L, Lucier-Greer Mallory, Mancini Jay A, Ford James L, Wickrama KAS. How Family Structures and Processes Interrelate: The Case of Adolescent Mental Health and Academic Success in Military Families. Journal of Family Issues. 2017;38(6):858–79. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin Alfred L. Behavior and Development in Childhood. New York: Dryden Press; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Barber Jennifer S, Yarger Jennifer E, Gatny Heather H. Black-White Differences in Attitudes Related to Pregnancy among Young Women. Demography. 2015;52(3):751–86. doi: 10.1007/s13524-015-0391-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind Diana. Child Care Practices Anteceding Three Patterns of Preschool Behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1967;75(1):43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind Diana. Current Patterns of Parental Authority. Developmental Psychology. 1971;4(1 Pt 2):1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Beck Audrey N, Cooper Carey E, Mclanahan Sara, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne. Partnership Transitions and Maternal Parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(2):219–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Wesley C. Consequences of Different Kinds of Parental Discipline. In: Hoffman ML, Hoffman LW, editors. Review of Child Development Research. Vol. 1. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1964. pp. 169–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi Laura. A Mixed-Methods Social Networks Study Design for Research on Transnational Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(4):788–803. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz Timothy J, Stacey Judith. How Does the Gender of Parents Matter? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(1):3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Blake Judith. Family Size and the Quality of Children. Demography. 1981;18(4):421–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos Henny MW, van Balen Frank, van den Boom Dymphna C. Child Adjustment and Parenting in Planned Lesbian-Parent Families. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77(1):38–48. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braver Sanford L, Curtis Bay R. Assessing and Compensating for Self-Selection Bias (Non-Representativeness) of the Family Research Sample. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1992;54(4):925–39. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Susan L. Family Structure Transitions and Adolescent Well-Being. Demography. 2006;43(3):447–61. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton Linda M, Dilworth-Anderson Peggye, Merriwether-deVries Cynthia. Context and Surrogate Parenting among Contemporary Grandparents. Marriage and Family Review. 1995;20(3–4):349–66. [Google Scholar]

- Cancian Maria, Meyer Daniel R, Brown Patricia R, Cook Steven T. Who Gets Custody Now? Dramatic Changes in Children’s Living Arrangements After Divorce. Demography. 2014;51(4):1381–96. doi: 10.1007/s13524-014-0307-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Patterson GR. Relation of Parental Transitions to Boys’ Adjustment Problems: I. A Linear Hypothesis. II. Mothers at Risk for Transitions and Unskilled Parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(3):489–504. [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh Shannon E. Family Structure History and Adolescent Adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(7):944–80. [Google Scholar]

- Cheadle Jacob E, Amato Paul R, King Valarie. Patterns of Nonresident Father Contact. Demography. 2010;47(1):205–25. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlin Andrew J. The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today. New York: Vintage Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Child Trends. Adopted Children. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Bureau. The AFCARS Report. Washington, D.C: Administration for Children & Families, U.S. Department of Health & Human Resources; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coontz Stephanie. The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper Carey E, McLanahan Sara S, Meadows Sarah O, Brooks-Gunn Jeanne, Johnson David. Family Structure Transitions and Maternal Parenting Stress. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(3):558–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00619.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté James E. The Dangerous Myth of Emerging Adulthood: An Evidence-Based Critique of a Flawed Developmental Theory. Applied Developmental Science. 2014;18(4):177–88. [Google Scholar]

- Curtin Sally C, Ventura Stephanie J, Martinez Gladys M. Recent Declines in Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db162.htm) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo David S, Forgatch Marion S. Contexts as Predictors of Changing Maternal Practices in Diverse Family Structures. In: Hetherington EM, editor. Coping With Divorce, Single Parenting, and Remarriage: A Risk and Resiliency Perspective. Mahwah, N.J: Psychology Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca Stefanie, Clampet-Lundquist Susan, Edin Kathryn. Coming of Age in the Other America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Demo David H, Acock Alan C. Family Structure, Family Process, and Adolescent Well-Being. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1996;6(4):457–488. [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente Ralph J, et al. Parental Monitoring: Association With Adolescents’ Risk Behaviors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):1363–68. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFonzo J Herbie. From the Rule of One to Shared Parenting: Custody Presumptions in Law and Policy. Family Court Review. 2014;52(2):213–39. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn Judy, Slomkowski Cheryl, Beardsall Lynn. Sibling Relationships from the Preschool Period through Middle Childhood and Early Adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30(3):315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer S, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies World Report: Assisted Reproductive Technology 2008, 2009 and 2010. Human Reproduction. 2016;31(7):1588–1609. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder Glen H. The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Development. 1998;69(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott Diana B, Simmons Tavia. Marital Events of Americans: 2009. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2011/acs/acs-13.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alcantara Adrienne L. Runaway and Homeless Youth: Demographics and Programs. Washington, D.C: Congressional Research Service; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Finer Lawrence B, Zolna Mia R. Shifts in Intended and Unintended Pregnancies in the United States, 2001–2008. American Journal of Public Health. 2014;104:S43–48. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fomby Paula, Mollborn Stefanie, Sennott Christie A. Race/Ethnic Differences in Effects of Family Instability on Adolescents’ Risk Behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72(2):234–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry Richard. For First Time in Modern Era, Living With Parents Edges Out Other Living Arrangements for 18- to 34-Year-Olds. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gates Gary. Family Formation and Raising Children Among Same-Sex Couples. National Council of Family Relations. 2012;51(1) Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5pq1q8d7) [Google Scholar]

- Gates Gary J. Marriage and Family: LGBT Individuals and Same-Sex Couples. The Future of Children. 2015;25(2):67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider Frances, Goldscheider Calvin. The Changing Transition to Adulthood: Leaving and Returning Home. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Golombok Susan, Tasker Fiona, Murray Clare. Children Raised in Fatherless Families from Infancy: Family Relationships and the Socioemotional Development of Children of Lesbian and Single Heterosexual Mothers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(7):783–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld Dorothy A, Seli Emre. Same-Sex Reproduction: Medical Treatment Options and Psychosocial Considerations. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2016;28(3):202–5. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover Stephanie A, Shmorgun Ziva, Moskovtsev Sergey I, Baratz Ari, Librach Clifford L. Assisted Reproduction in a Cohort of Same-Sex Male Couples and Single Men. Reproductive BioMedicine Online. 2013;27(2):217–21. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnoe Marjorie L. Doctoral Dissertation. University of Virginia; Charlottesville, Virginia: 1993. Noncustodial Mothers’ and Fathers’ Contributions to the Adjustment of Adolescent Stepchildren. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Scott R. What Is Family Diversity? Objective and Interpretive Approaches. Journal of Family Issues. 2008;29(11):1407–25. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood Jake. Communication Media Use in the Grandparent-Grandchild Relationship. Journal of Communication. 2000;50(4):56–78. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Elizabeth I, Easterling Beth. Understanding Unique Effects of Parental Incarceration on Children: Challenges, Progress, and Recommendations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(2):342–56. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston Lloyd D, O’Malley Patrick M. Issues of Validity and Population Coverage in Student Surveys of Drug Use. In: Rouse BA, Kozel NJ, Richards LG, editors. Self-Report Methods of Estimating Drug Use: Meeting Current Challenges to Validity. Washington, D.C: National Institute on Drug Abuse, Department of Health and Human Services; 1985. pp. 31–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Deborah J, Zalot Alecia A, Foster Sarah E, Sterrett Emma, Chester Charlene. A Review of Childrearing in African American Single Mother Families: The Relevance of a Coparenting Framework. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2007;16(5):671–83. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp Candace L. Grandparent—Grandchild Ties: Reflections on Continuity and Change Across Three Generations. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(7):855–81. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Sheela, Bumpass Larry. Cohabitation and Children’s Living Arrangements: New Estimates from the United States. Demographic Research. 2008;19:1663–92. doi: 10.4054/demres.2008.19.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy Sheela, Ruggles Steven. Breaking Up Is Hard to Count: The Rise of Divorce in the United States, 1980–2010. Demography. 2014;51(2):587–98. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0270-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Ji-Yeon, McHale Susan M, Wayne Osgood D, Crouter Ann C. Longitudinal Course and Family Correlates of Sibling Relationships from Childhood through Adolescence. Child Development. 2006;77(6):1746–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider Rose M, Ellis Renee. Living Arrangements of Children: 2009. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider Rose M, Lofquist Daphne A. Adopted Children and Stepchildren: 2010. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( https://www.census.gov/prod/2014pubs/p20-572.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Lansford Jennifer E, Ceballo Rosario, Abbey Antonia, Stewart Abigail J. Does Family Structure Matter? A Comparison of Adoptive, Two-Parent Biological, Single-Mother, Stepfather, and Stepmother Households. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63(3):840–51. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin Lynda. A Child’s Day: Living Arrangements, Nativity, and Family Transitions: 2011 (Selected Indicators of Child Well-Being) Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Dohoon, McLanahan Sara. Family Structure Transitions and Child Development: Instability, Selection, and Population Heterogeneity. American Sociological Review. 2015;80(4):738–63. doi: 10.1177/0003122415592129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lempers Jacques D, Clark-Lempers Dania S. Young, Middle, and Late Adolescents’ Comparisons of the Functional Importance of Five Significant Relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1992;21(1):53–96. doi: 10.1007/BF01536983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg Laura, Santelli John, Desai Sheila. Understanding the Decline in Adolescent Fertility in the United States, 2007–2012. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;59(5):577–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning Wendy D, Brown Susan L, Bart Stykes J. Family Complexity among Children in the United States. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2014;654(1):48–65. doi: 10.1177/0002716214524515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joyce A, Hamilton Brady E, Osterman Michelle JK, Driscoll Anne K, Matthews TJ. Births: Final Data for 2015. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland Joel, et al. The Condition of Education 2017. Washington, D.C: National Center for Education Statistics; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McHale Susan M, Updegraff Kimberly A, Whiteman Shawn D. Sibling Relationships and Influences in Childhood and Adolescence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(5):913–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.01011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan Sara, Sandefur Gary. Growing Up With a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer Daniel R, Cancian Maria. ‘I’m Not Supporting His Kids’: Nonresident Fathers’ Contributions Given Mothers’ New Fertility. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74(1):132–51. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Katherine S. Pathways of Children’s Long-Term Living Arrangements: A Latent Class Analysis. Social Science Research. 2013;42(5):1284–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell Lauren L, Syed Moin. Does College Matter for Emerging Adulthood? Comparing Developmental Trajectories of Educational Groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2015;44(11):2012–27. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0330-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte Lindsay M. Multiple Partner Fertility Research Brief. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Murphey David, Mae Cooper P. Parents Behind Bars: What Happens to Their Children? Bethesda, MD: Child Trends; 2015. Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( http://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/BTB_23_4K_6.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. The State of Homelessness in America. Washington, D.C: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Newman Katherine S. The Accordion Family: Boomerang Kids, Anxious Parents, and the Private Toll of Global Competition. Boston: Beacon Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara Amy, Shattuck Rachel M, Goerge Robert M. Linking Federal Surveys with Administrative Data to Improve Research on Families. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2017;669(1):63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips Tommy M. The Influence of Family Structure Vs. Family Climate on Adolescent Well-Being. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2012;29(2):103–10. [Google Scholar]

- Pinzon Jorge L, Jones Veronnie F Committee on Adolescence, and Committee on Early Childhood. Care of Adolescent Parents and Their Children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1743–56. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell Brian, Bolzendahl Catherine, Geist Claudia, Steelman Lala C. Counted Out: Same-Sex Relations and Americans’ Definitions of Family. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor Jan. Parenting in Reconstituted and Surrogate Families. In: Hoghughi M, Long N, editors. Handbook of Parenting: Theory and Research for Practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2004. pp. 110–29. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman Nancy E, Teitler Julien O, Garfinkel Irwin, McLanahan Sara S. Fragile Families: Sample and Design. Children and Youth Services Review. 2001;23(4/5):303–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum James E. Beyond College For All: Career Paths for the Forgotten Half. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles Steven. The Rise of Divorce and Separation in the United States, 1880–1990. Demography. 1997;34(4):455–66. doi: 10.2307/3038300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles Steven, Brower Susan. Measurement of Household and Family Composition in the United States, 1850–2000. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(1):73–101. [Google Scholar]

- Mae Sallie. How America Pays for College. Newark, DE: Sallie Mae; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer Nora C, Seltzer Judith A, Dykema Jennifer. Methodological and Theoretical Issues in Studying Nonresident Fathers: A Selective Review. 1998 Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED456162)

- Sears Robert R, Maccoby Eleanor E, Levin Harry. Patterns of Child Rearing. Oxford, England: Row, Peterson; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Simons Leslie G, Conger Rand D. Linking Mother–Father Differences in Parenting to a Typology of Family Parenting Styles and Adolescent Outcomes. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(2):212–41. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Dorothy E. The Standard North American Family: SNAF as an Ideological Code. Journal of Family Issues. 1993;14(1):50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Herbert L, Philip Morgan S, Koropeckyj-Cox Tanya. A Decomposition of Trends in the Nonmarital Fertility Ratios of Blacks and Whites in the United States, 1960–1992. Demography. 1996;33(2):141–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soliz Jordan. Intergenerational Support and the Role of Grandparents in Post-Divorce Families: Retrospective Accounts of Young Adult Grandchildren. Qualitative Research Reports in Communication. 2008;9(1):72–80. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkhabi Nadia, Mandara Jelani. Are the Effects of Baumrind’s Parenting Styles Culturally Specific or Culturally Equivalent. In: Larzelere RE, Morris AS, Harrist AW, editors. Authoritative Parenting: Synthesizing Nurturance and Discipline for Optimal Child Development. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2013. pp. 113–35. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa Liliana, Sorensen Elaine J. The Economic Reality of Nonresident Mothers and Their Children. Washington, D.C: Urban Institute; 2006. Retrieved February 28, 2018 ( http://webarchive.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311342_B-69.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Laurence. Adolescence. 11. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg Laurence. We Know Some Things: Parent–Adolescent Relationships in Retrospect and Prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sterrett Emma M, Jones Deborah J, McKee Laura G, Kincaid Carlye. Supportive Non-Parental Adults and Adolescent Psychosocial Functioning: Using Social Support as a Theoretical Framework. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;48(3–4):284–95. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9429-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]