Abstract

Objective

To undertake a cost-utility analysis of a motivational multicomponent lifestyle-modification intervention in a community setting (the Healthy Eating Lifestyle Programme (HELP)) compared with enhanced standard care.

Design

Cost-utility analysis alongside a randomised controlled trial.

Setting

Community settings in Greater London, England.

Participants

174 young people with obesity aged 12–19 years.

Interventions

Intervention participants received 12 one-to-one sessions across 6 months, addressing lifestyle behaviours and focusing on motivation to change and self-esteem rather than weight change, delivered by trained graduate health workers in community settings. Control participants received a single 1-hour one-to-one nurse-delivered session providing didactic weight-management advice.

Main outcome measures

Mean costs and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) per participant over a 1-year period using resource use data and utility values collected during the trial. Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated and non-parametric bootstrapping was conducted to generate a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

Results

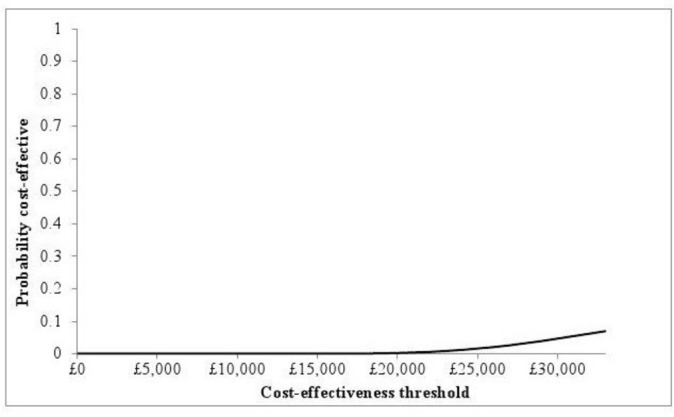

Mean intervention costs per participant were £918 for HELP and £68 for enhanced standard care. There were no significant differences between the two groups in mean resource use per participant for any type of healthcare contact. Adjusted costs were significantly higher in the intervention group (mean incremental costs for HELP vs enhanced standard care £1003 (95% CI £837 to £1168)). There were no differences in adjusted QALYs between groups (mean QALYs gained 0.008 (95% CI −0.031 to 0.046)). The ICER of the HELP versus enhanced standard care was £120 630 per QALY gained. The CEAC shows that the probability that HELP was cost-effective relative to the enhanced standard care was 0.002 or 0.046, at a threshold of £20 000 or £30 000 per QALY gained.

Conclusions

We did not find evidence that HELP was more effective than a single educational session in improving quality of life in a sample of adolescents with obesity. HELP was associated with higher costs, mainly due to the extra costs of delivering the intervention and therefore is not cost-effective.

Trial registration number

ISRCTN9984011.

Keywords: childhood obesity, cost-effective, cost-utility, qaly

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was based on data from a randomised controlled trial.

The economic evaluation followed published best-practice guidance.

Intervention costs were calculated as mean values per participant and did not include participant-level variation.

Resource use data were collected retrospectively from study participants and may be affected by inaccurate recall.

Intervention costs were relatively high due to the large number of providers involved, producing a small number of participants per provider.

Introduction

Obesity is associated with significant health expenditures. In England, the costs of overweight and obesity to the health system have been calculated to be £4.2 billion per annum.1 Individuals with obesity have been found to have medical costs approximately 30% greater than their normal-weight peers.2 In terms of non-health care costs, productivity losses due to obesity have been estimated to be £15.8 billion.1 Childhood obesity in particular imposes a substantial cost to the health system, with estimates of around US$14 billion per annum in the USA.3

Obesity in children and adolescents is a global public health concern. Approximately 7% of children and adolescents in the UK have obesity at a level likely to be associated with comorbidities.4

Prevention of obesity is important, so too are effective treatments for those already affected. Lifestyle interventions, involving a combination of diet, exercise and/or behaviour modification are essential for obesity management.5

The Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme (HELP) is a community-delivered evidence-based multicomponent intervention focusing on enhancing motivation to change, developing self-efficacy and self-esteem for individuals with obesity aged 12–19 years, seeking help to manage their weight. In an accompanying paper,6 we evaluated the efficacy of HELP intervention compared with enhanced standard care for adolescents with obesity. In this paper, we focus on the cost-effectiveness of the HELP intervention.

There are few economic evaluations of childhood lifestyle obesity interventions; and among those that have been conducted, differences in the type of intervention, age of participants, cost components included, country of setting, outcomes of interest and methodologies mean that it is difficult to draw conclusions as to whether such interventions are cost-effective (see online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2017-018640supp001.pdf (229.5KB, pdf)

Therefore, the aim of this paper was to assess the costs and cost-effectiveness of the HELP intervention from the perspective of the UK National Health Service (NHS).

Methods

Trial design

The HELP trial was a Medical Research Council complex phase III efficacy randomised clinical trial. The study tested a community-delivered multicomponent intervention designed for adolescents, developed from best practice as identified by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE).5

The study population comprised 174 young people with obesity (body mass index (BMI) >95th BMI centile for age and sex based on the UK 1990 growth reference7), aged 12–19 years, recruited from primary care and community settings within the Greater London area. Participants were individually randomised to receiving either the HELP intervention (n=87) or enhanced standard care (n=87).

Intervention participants and at least one parent attended 12 fortnightly ~60 min sessions with a Graduate Health Worker (‘provider’) in one-to-one meetings over 6 months. A written manual was used to enable delivery in a standardised manner by all the providers. The intervention comprised motivational interviewing and solution-focused approaches to increase engagement and concordance with the four programme components: (1) modifying eating behaviour and encouraging regular eating patterns, (2) decreasing sedentary behaviour and increasing lifestyle and programme activity, (3) reducing intake of energy-dense foods and increasing healthy nutritional choice and (4) addressing emotional eating triggers.

Controls attended one one-to-one enhanced standard care session delivered by a community or primary care nurse at the young person’s general practice or an alternative community setting. Where a practice nurse was not available, a trained staff (eg, agency nurse, healthcare assistant) was provided by the study team to deliver the session. The session lasted ~40–60 min and incorporated standard Department of Health guidance and published information on obesity including information on eating behaviours, healthy activity levels and healthy eating patterns.

Further details of the structure of the clinical trial are available from the study protocol8 and from the accompanying paper.6

The trial found that mean BMI across the whole study population was 32.3 kg/m2 (SD 4.4) at the start and 32.6 kg/m2 (SD 4.7) at the end of the intervention. There were no significant differences in the primary outcome, BMI at 6 months, between groups: adjusted difference in BMI −0.11 kg/m2 ((95% CI −0.62 to 0.40), P value=0.7). No significant differences were observed for changes in secondary outcomes including BMI z-score, fat mass, self-esteem, eating behaviours or quality of life (all P values >0.3) between intervention and control groups at 6 months.6 The process evaluation showed that participants and their families found the intervention highly engaging, respectful and helpful in making reported behavioural changes.

Patient involvement

Adolescents and their families were not involved in the design of the study; however, conversations with families about questionnaires had taken place in relation to other projects and audits. Feedback from clinical contact with adolescents and parents were used to inform the development of the research question and outcome measures. Adolescents and parents were not involved in the recruitment and conduct of the study. As part of the study, an integrated process evaluation reviewed participants’ experience of taking part in the randomised controlled trial. In addition, an independent qualitative evaluation of participant experience was completed and presented at a dissemination day. Adolescents and parents participated in the dissemination day contributing to a future research design. A summary of the study results was sent to all adolescents who took part in the trial.

Overview of economic evaluation

We undertook a cost-utility analysis to compare the costs and outcomes associated with HELP versus enhanced standard care. The outcome measure was quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which combine length of life and quality of life and is consistent with the NICE recommendations.9 The analysis took a UK NHS perspective; costs from a personal social services perspective were likely to be negligible and so were excluded. Costs were calculated in 2013/2014 UK pounds. The time horizon was 1 year, reflecting follow-up in the trial. Extrapolation beyond the end of the trial using decision-analytical modelling was not undertaken because the within-trial analysis found no evidence of significant differences in benefits between intervention and control groups, and costs were significantly higher in the intervention group; the 1 year time horizon was long enough to reflect all important differences in costs or outcomes between the two treatments. Since the time horizon was 1 year, discounting was unnecessary.

Resource use and costs

For every participant, we calculated the cost of the lifestyle intervention and the cost of follow-up using resource use data collected retrospectively in the trial via questionnaires sent to participants at baseline and 6 and 12 months postrandomisation.

The cost of HELP included providers’ training, learning materials for providers and participants and time spent by providers/experienced psychologist in each follow-up session with participants.

There were 21 providers who received training to deliver HELP (each trained for 5 days; 7 hours/day) from experienced psychologists in specific motivational interviewing techniques and the use of solution-focused questioning in the intervention group. In the enhanced standard care group, the nurses did not receive any training in delivery style.

In the HELP group, we accounted for 1.5 hours spent by the provider to deliver the intervention and room rental for each session, plus 1.5 hours spent by the experienced psychologist to supervise the delivery of session 1 of the intervention with the provider’s first participant. In the enhanced standard care group, we accounted for 1 hour spent by the nurse to deliver the single educational session plus room rental.

Providers’ travel time (mean 1.5 hours) to and from session venues, and travel costs were accounted for in the HELP group. Travel time (mean 2 hours) to and from session venues was accounted for in the enhanced standard care group only if the intervention was delivered by a nurse provided by the study team (n=36), as other standard care sessions were provided by local practice nurses in their own practice.

Educational materials (manuals/leaflets) were supplied for both providers and participants in the HELP group. Leaflets were supplied for participants in the enhanced standard care group.

Follow-up resource use included: general practitioner (GP) surgery consultations; GP telephone consultations; GP home consultations; contacts with the practice nurse; referrals to secondary care services (eg, dietitian, physiotherapist, osteopath, chiropractor, psychologist, counsellor, dentist, radiologist, community pharmacist); hospital inpatient admissions; hospital day cases and hospital outpatient visits.

Unit costs were obtained from published sources10 11 (for all resource use associated with follow-up care not directly related to the interventions; table 1) and local costs (for any resource use needed to deliver the intervention; see online supplementary table 2), inflated where appropriate.

Table 1.

Mean healthcare resource use±SD, unit costs (2013/2014 values), complete data

| Type of resource use (unit) | Unit costs (references) |

HELP | Enhanced standard care | Difference | P value | ||

| N | Mean±SD | N | Mean±SD | ||||

| Hospital inpatient (admission) | £1758.369 | 59 | 0.05±0.29 | 53 | 0.06±0.41 | −0.01 | 0.93 |

| Hospital day case (attendance) | £693.009 | 59 | 0.15±0.81 | 52 | 0.04±0.19 | 0.11 | 0.32 |

| Hospital outpatient (visit) | £108.229 | 58 | 0.64±1.22 | 52 | 0.29±0.70 | 0.35 | 0.07 |

| A&E (visits) | £115.009 | 58 | 0.29±0.56 | 53 | 0.23±0.54 | 0.07 | 0.53 |

| GP surgery (consultation) | £45.0010 | 58 | 1.57±2.31 | 50 | 1.46±1.80 | 0.11 | 0.79 |

| GP home (visit) | £114.0010 | 59 | 0.00±0.00 | 53 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| GP phone (consultation) | £27.0010 | 59 | 0.27±0.69 | 53 | 0.32±0.94 | −0.05 | 0.75 |

| Nurse home (visit) | £70.0010 | 59 | 0.02±0.13 | 52 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| Nurse surgery (visit) | £13.4310 | 58 | 0.26±0.78 | 53 | 0.25±0.78 | 0.01 | 0.93 |

| Nurse phone (consultation) | £13.4310 | 58 | 0.02±0.13 | 52 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.02 | 0.35 |

| NHS dietician (visit) | £35.0010 | 58 | 0.09±0.34 | 52 | 0.04±0.19 | 0.05 | 0.37 |

| Community pharmacist (contact) | £56.0010 | 58 | 0.31±0.78 | 52 | 0.15±0.54 | 0.16 | 0.23 |

| NHS physiotherapist (visit) | £34.0010 | 58 | 0.14±0.71 | 53 | 0.19±1.00 | −0.05 | 0.76 |

| Private physiotherapist (visit) | £77.0010 | 58 | 0.03±0.26 | 53 | 0.06±0.41 | −0.02 | 0.73 |

| Osteopath (visit) | £34.0010 | 58 | 0.03±0.26 | 53 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.03 | 0.34 |

| Chiropractor (visit) | £34.0010 | 58 | 0.00±0.00 | 53 | 0.00±0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Psychologist (visit) | £59.0010 | 58 | 0.31±1.88 | 53 | 0.06±0.41 | 0.25 | 0.34 |

| Counsellor (visit) | £58.0010 | 58 | 0.09±0.66 | 53 | 0.30±1.48 | −0.22 | 0.31 |

| Any other healthcare (contact) | £81.009 10 | 57 | 0.46±1.31 | 53 | 0.45±1.25 | 0.01 | 0.99 |

A&E, accident and emergency; GP, general practitioner; HELP, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme; NHS, National Health Service.

bmjopen-2017-018640supp002.pdf (88.5KB, pdf)

Utilities and QALYs

Participants’ generic health state was assessed using the EuroQol 5D (EQ-5D-3L) descriptive system12 13 at baseline, 6 and 12 months postrandomisation. The EQ-5D-3L is a validated generic health-related preference-based measure comprising five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain, anxiety/depression) with three levels in each item. Every EQ-5D-3L health state was converted into a single summary index (utility value) using a formula that attaches weights to each of the levels in each dimension based on valuations by general population samples. Given the perspective of our analysis, we used a value set for the UK population to calculate utility values at each time point for every participant.14 Utility values at each point in time were calculated. The values lie on a scale between 0 (equivalent to death) and 1 (equivalent to full health); negative values are possible, representing states worse than death. A utility profile was created for each participant assuming a straight line relation between their utility values at each measurement point in time. QALYs for each participant from baseline to 12 months were calculated as the area under the utility profile.

Dealing with missing data

Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data for costs of primary and secondary care contacts, total cost, utility values at every time point and total QALYs. The cost variables were unit costs multiplied by resource use. Age, gender and treatment allocation were included in the imputation models as additional explanatory variables.

We used multiple imputation with chained equations to impute missing data under the assumptions that data were missing at random. We generated 20 imputed datasets.

Statistical methods

Mean resource use, costs, utility values and QALYs were compared between groups on an intention-to-treat basis and the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) calculated.

We calculated differences in mean costs and QALYs between groups using regression analysis, regressing individual QALYs and costs against treatment allocation in the trial controlling for other factors.

QALYs gained were adjusted for age, gender and baseline utility values. Incremental costs were adjusted for age, gender and costs in the 6-month period prior to baseline. To analyse QALYs gained, we used a linear regression model. To account for skewness of the cost data, we used a generalised linear model with gamma family and log link;15 we also considered using log Normal, Gaussian, inverse Gaussian and negative binomial distributions, but the gamma model gave the best fit in terms of residual plots and the Akaike Information Criterion. Standard errors were corrected to account for uncertainty in the imputed values. Analyses were carried out using STATA V.13.1.

The ICER was calculated by dividing the incremental costs (difference in costs between HELP intervention and enhanced standard care groups) by incremental QALYs (difference in QALYs between HELP intervention and enhanced standard care groups). We used the cost-effectiveness threshold range recommended by NICE (£20 000 to £30 000)9 as the lower and upper limits of the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY.

For each of the 20 imputed datasets, we ran 1000 bootstrap replications and combined the results using published equations16 to calculate standard errors around mean values accounting for uncertainty in imputed values, the skewed nature of the cost data and utility values and sampling variation. Standard errors were used to calculate 95% CIs around point estimates.

A cost-effectiveness acceptability curve17 showing the probability that the HELP intervention was cost-effective compared with enhanced standard care at a range of values for the maximum willingness to pay for a QALY was generated based on the proportion of the bootstrap replications across all 20 imputed datasets. The probabilities that the HELP intervention was cost-effective at a maximum willingness to pay for a QALY of £20 000 and £30 000 were reported.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

Participants in the clinical trial were well balanced in terms of age, gender and baseline BMI and EQ-5D values, although there were slightly fewer black participants and slightly greater numbers of white and Asian participants in the HELP arm.6

Resource use and costs

During the 12-month follow-up, there were no significant differences in any component of healthcare resource use between HELP and enhanced standard care (table 1). The most common types of contact were GP surgery visits for both groups with a mean (SD) of 1.57 (SD 2.31) visits per participant in the HELP group (n=58) and 1.46 (SD 1.80) visits per participant in the enhanced standard care group (n=50), followed by outpatient visits in the HELP group (mean 0.64 (SD 1.22), n=58) and counsellor visits in the enhanced standard care group (mean 0.30 (SD 1.48), n=53). Any other healthcare visits comprised visits with a dentist, orthodontist or an optician.

In the complete case analysis, the mean total cost of healthcare resource use per participant were £363 (95% CI £221 to £505) in the HELP group (n=55) and £357 (95% CI £114 to £600) in the enhanced standard care group (n=48; table 2). Accounting for missing data using multiple imputation, the values were £320 (95% CI £212 to £428) and £462 (95% CI £268 to £657), respectively.

Table 2.

Mean cost±SD of HELP and enhanced standard care and resource use per participant

| Type of costs | HELP | Enhanced standard care | HELP versus enhanced standard care |

| Training | |||

| Provider/nurse | £130±£0 | £0±£0 | £130 |

| Psychologist | £46±£0 | £0±£0 | £46 |

| Intervention | |||

| Provider/nurse | £201±£90 | £33±£17 | £168 |

| Psychologist | £134±£60 | £0±£0 | £134 |

| Room rental | £114±£51 | £13±£6 | £101 |

| Travel | |||

| Provider/nurse | £279±£124 | £22±£26 | £257 |

| Materials | |||

| Manual for provider | £3±£0 | £0±£0 | £3 |

| Manual/leaflets for participant | £5±£0 | £1±£0 | £4 |

| Other materials for participant | £5±£0 | £0±£0 | £5 |

| Intervention costs per participant | £918±£201 | £68±£22 | £850 |

| Costs (95% CI) of healthcare resource use during follow-up | |||

| Complete cases | £363 (£221 to £505) (n=55) |

£357 (£114 to £600) (n=48) |

£6 (-£264 to £275) (n=103) |

| With imputation | £320 (£212 to £428) |

£462 (£268 to £657) |

-£142 (-£363 to £79) |

| Total costs (95% CI) per participant (intervention cost plus healthcare resource use during follow-up) | |||

| Complete cases | £1281 (£1246 to £1527) (n=55) |

£425 (£188 to £675) (n=48) |

£855 (£685 to £1,224) (n=103) |

| With imputation | £1238 (£1237 to £1452) |

£530 (£343 to £732) |

£708 (£587 to £1028) |

HELP, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme.

There were 758 sessions delivered in the intervention group and 71 sessions delivered in the control group. The mean total intervention cost per participant was £918 (95% CI £875 to £960) for the delivery of the HELP intervention and £68 (95% CI £63 to £73; table 2) for enhanced standard care.

Accounting for missing data using multiple imputation the mean total costs per participant were £1238 (95% CI £1237 to £1452) in the intervention group (n=87) and £530 (95% CI £343 to £732) in the control group (n=87; table 2). Values for complete case analysis followed the same trend (table 2). The difference in intervention costs between intervention and control groups was driven by the costs of the delivery of HELP intervention and provider’s travel.

Utilities and QALYs

Mean utility values per participant at each follow-up point were similar for both groups and did not vary significantly over time in either group (table 3).

Table 3.

Mean utility values and QALYs per participant

| Utility values | HELP | Enhanced standard care | ||

| Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | |

| Complete cases | ||||

| Baseline | 0.793 (n=83) | (0.735 to 0.850) | 0.833 (n=85) | (0.792 to 0.875) |

| 6 months | 0.852 (n=68) | (0.803 to 0.902) | 0.881 (n=63) | (0.844 to 0.918) |

| 12 months | 0.851 (n=59) | (0.799 to 0.902) | 0.871 (n=52) | (0.812 to 0.930) |

| QALYs | 0.837 (n=54) | (0.787 to 0.887) | 0.867 (n=50) | (0.828 to 0.907) |

| With imputation | ||||

| Baseline | 0.792 | (0.736 to 0.849) | 0.829 | (0.788 to 0.870) |

| 6 months | 0.848 | (0.806 to 0.890) | 0.891 | (0.858 to 0.924) |

| 12 months | 0.849 | (0.807 to 0.891) | 0.847 | (0.805 to 0.889) |

| QALYs | 0.855 | (0.816 to 0.895) | 0.881 | (0.851 to 0.921) |

Data include values imputed using multiple imputation (see text).

HELP, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years.

Accounting for missing data, mean utility values per participant in the intervention group increased from 0.792 (95% CI 0.736 to 0.849) at baseline to 0.848 (95% CI 0.806 to 0.890) at 6 months and then at 0.849 (95% CI 0.807 to 0.891) at 12 months. The mean utility values per participant in control group increased from 0.829 (95% CI 0.788 to 0.870) at baseline to 0.891 (95% CI 0.858 to 0.924) at 6 months and declined to 0.847 (95% CI 0.805 to 0.889) at 12 months. Mean total QALYs per participant in the intervention group were 0.855 (95% CI 0.816 to 0.895) and in control group were 0.881 (95% CI 0.851 to 0.912). Utility values and QALYs were similar for complete cases.

Cost-utility analysis

In the base case analysis, accounting for missing data using multiple imputation and baseline characteristics, there were no significant differences in costs or QALYs between the two groups: the mean incremental cost for HELP versus enhanced standard care was £1003 (95% CI £837 to £1 168) and the mean QALYs gained were 0.008 (95% CI −0.031 to 0.046) (table 4). The incremental costs and QALYs gained for HELP versus enhanced standard care remained not significantly different from zero when rerunning the base case analysis without adjustment and using complete cases.

Table 4.

Cost-effectiveness of HELP intervention versus enhanced standard care: complete case and imputed data analyses (baseline to 12 months)

| Incremental cost | QALYs gained | |||

| Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | |

| Base case* | £1003 | (£837 to £1 168) | 0.008 | (−0.031 to 0.046) |

| No adjustment† | £861 | (£713 to £1 010) | −0.037 | (−0.100 to 0.027) |

| Complete case analysis‡ | £1022 | (£673 to £1 372) | 0.018 | (−0.021 to 0.058) |

| Complete case analysis with no adjustment§ | £955 | (£432 to £1 477) | −0.030 | (−0.093 to 0.033) |

*Data include values imputed using multiple imputation with SEs corrected to account for uncertainty in the imputed values. The QALYs gained are adjusted for age, gender and baseline utility values. The incremental costs are adjusted for age, gender costs in the 6-month period prior to baseline.

†As for the base case analysis except the QALYs gained and the incremental costs are unadjusted.

‡As for the base case analysis except there is no multiple imputation of missing values.

§As for the base case analysis except the QALYs gained and the incremental costs are unadjusted and there is no multiple imputation of missing values.

HELP, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme; QALYs, quality-adjusted life years.

The ICER of the HELP versus enhanced standard care was £120 630 per QALY gained. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve shows that the probability that HELP was cost-effective relative to the enhanced standard care was 0.002 or 0.046, at a threshold of £20 000 or £30 000 per QALY gained (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cost-effectiveness acceptability curve showing the probability that the HELP intervention is cost-effective compared with enhanced standard care over a range of values of the cost-effectiveness threshold. HELP, Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme.

Discussion

Principal findings

The HELP trial showed that changes in BMI in adolescents with obesity who received the intervention are similar to those seen in adolescents who received enhanced standard care. Our economic analysis of the HELP trial showed that the intervention had similar outcomes but higher costs when compared with the enhanced standard care. Resource use during follow-up was similar between the trial arms, and therefore the cost of the HELP intervention was the major driver of the cost difference.

Given no differences in outcomes or resource use during follow-up between groups and higher intervention costs, our findings indicate the HELP intervention is unlikely to be cost-effective.

Strengths and weaknesses

The HELP intervention was designed specifically for adolescents who have difficulties losing weight and encouraged parents to participate and support their children. The major strength of the study is that it is based on data from a randomised controlled trial and that best practice methods have been used in the economic evaluation. Moreover, the numbers of control and intervention participants in the economic evaluation were balanced and their baseline characteristics were similar, although there were slightly fewer black participants and slightly greater numbers of white and Asian participants in the HELP arm.

Self-reported questionnaires were used for obtaining resource use data; these are a valid method of collecting data on healthcare resource use and are commonly used. We acknowledge that self-reported questionnaires may be subject to inaccurate recall, though we have no reason to believe this would be different between groups.

Due to high staff turnover during the study, there were 21 providers trained to deliver the intervention, and this might contribute to the relatively high mean cost per participant of the HELP intervention; smaller number of providers would lower the average training costs.

Also one-to-one meetings between participants and providers potentially made the intervention relatively resource intensive. The costs could be reduced if the intervention was provided in a group setting, however, the motivational interviewing is unlikely to be possible in such a setting.

The HELP intervention was costed using a uniform assessment of the time spent by providers in delivering the intervention. Although it is expected that there will be some variability at individual level, our approach to costing the intervention is pragmatic and unlikely to affect our findings.

Our economic analysis had a time horizon of only 1 year, reflecting the duration of follow-up in the trial. While this is a limited duration, given we found no differences in utility values, QALYs or resource use during follow-up between groups up to 12 months then measuring costs and benefits after 1 year using modelling was unlikely to change the results.

We also only included NHS costs in our evaluation and not, for example, costs to participants and families. Given there were no differences in healthcare resource use during follow-up and utility values between groups, including these costs is unlikely to change our conclusions. They may make the intervention appear less cost-effective if HELP intervention costs were to increase when incorporating time and travel costs borne by adolescents and families to participate in the intervention.

Comparisons with other studies

As noted (see online supplementary table 1), there are few evaluations of childhood obesity interventions that include an economic evaluation with which to compare our results; however, differences between studies in terms of age of participants, country, components of the interventions and outcome measures make comparisons with other studies difficult.

In our study, possible explanations as to why there was no difference in outcomes between study groups may relate to the lack of effect of the intervention (it is possible that the trial did not provide an adequate test of the intervention, although adequately powered and methodologically robust), methodology (slow recruitment, widening the age range, dropouts) and population (highly deprived, mental health problems at baseline, despite exclusion of those known with mental health conditions).6

Implications

The health risks and healthcare costs associated with overweight and obesity are considerable. A public health approach to develop lifestyle interventions in adolescents should target factors contributing to obesity and barriers to lifestyle change at personal, environmental and socioeconomic levels.18

The HELP intervention was no more efficacious than a standard care of a single educational session for reducing BMI in a community sample of adolescents with obesity. This adds to a large literature on negative weight-management trials for children and adolescents. Further work to understand how weight-management programmes can be delivered effectively to young people should be considered. Such research must also consider the cost implications of weight-management programmes.

Future research

Future research is needed to identify the most cost-effective lifestyle intervention for adolescents with obesity, including its length and intensity, as well as long-term sustainability into adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the young people, families and providers from the HELP trial for providing the data on which this analysis is based.

Footnotes

Contributors: MP undertook the economic analysis and drafted the paper with input from all authors, and is the guarantor. DC conceptualised the trial, developed the trial design and intervention and revised the paper. TJC contributed to the trial design, developed the trial statistical plan and revised the paper. SC and JW monitored the data collection, cleaned the data and revised the paper. JG developed the trial statistical plan and revised the paper. RH supervised the providers and revised the paper. LDH, AK and AM contributed to trial design, writing of the protocol and revised the paper. SK, ICKW and IN contributed to the trial design and revised the paper. RMV conceptualised the trial, developed the trial design and intervention, developed the trial statistical plan and revised the paper. SM contributed to the trial design, developed the health economic plan and drafted and revised the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the NIHR under its Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (Grant Reference Number RP-PG-0608-10035)—the Paediatric Research in Obesity Multi-model Intervention and Service Evaluation (PROMISE) programme). The HELP research team acknowledges the support of the NIHR through the Primary Care Research Network. TJC was funded by MRC grant MR/M012069/1.

Disclaimer: The views represented in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily represent those of PHE, NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: AK is Director of International Public Health at Public Health England (PHE).

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: National Research Ethics Service, West London REC 3, on 27 August 2010. Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference number 10/H0706/54.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1.National Obesity Observatory (Public Health England). The economic burden of obesity. 2010. http://www.a-new-shape.co.uk/attachments/05112015141030_17022015122116_vid_8575_Burdenofobesity151110MG.pdf (accessed May 2017).

- 2.Withrow D, Alter DA. The economic burden of obesity worldwide: a systematic review of the direct costs of obesity. Obes Rev 2011;12:131–41. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00712.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research (NCCOR). Childhood obesity in the United States. 2009. http://www.nccor.org/downloads/ChildhoodObesity_020509.pdf (accessed May 2017).

- 4.Lobstein T, Leach RJ. 2007. Tackling obesities: future choices: international comparisons of obesity trends, determinants and response—evidence review-2. Children: foresight: Government Office for Science. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Obesity: guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children. UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christie D, Hudson LD, Kinra S, et al. A community-based motivational personalised lifestyle intervention to reduce BMI in obese adolescents: results from the Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme (HELP) randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child 2017;102:695–701. 10.1136/archdischild-2016-311586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Obesity Observatory (Public Health England). A simple guide to classifying body mass index in children. 2011. https://khub.net/documents/31798783/32039025/A+simple+guide+to+classifying+body+mass+index+in+children/ced23256-6f8d-43c7-9f44-222e2beebf97?version=1.0 (accessed May 2017).

- 8.Christie D, Hudson L, Mathiot A, et al. Assessing the efficacy of the Healthy Eating and Lifestyle Programme (HELP) compared with enhanced standard care of the obese adolescent in the community: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2011;12:242 10.1186/1745-6215-12-242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health. National schedule of reference costs- year 2013-2014- NHS trusts and nhs foundation trusts: NHS own cost. London: Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis L. Unit costs of health and social care 2013. Kent: Personal Social Service Research Unit, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.EuroQol Group. EuroQol–a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990;16:199–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53–72. 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolan P. Modeling valuations for EuroQol health states. Med Care 1997;35:1095–108. 10.1097/00005650-199711000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barber J, Thompson S. Multiple regression of cost data: use of generalised linear models. J Health Serv Res Policy 2004;9:197–204. 10.1258/1355819042250249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs A, Clark T, Wolstenholme J, et al. Missing…presumed at random: cost-analysis of incomplete data. Health Econ 2003;12:377–92. 10.1002/hec.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briggs AH, Gray AM. Handling uncertainty when performing economic evaluation of healthcare interventions. Health Technol Assess 1999;3:1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan RS, Woo J. Prevention of overweight and obesity: how effective is the current public health approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2010;7:765–83. 10.3390/ijerph7030765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018640supp001.pdf (229.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-018640supp002.pdf (88.5KB, pdf)