Abstract

This research examines the levels of condom use self-efficacy in a population of men who have sex with men who are at great risk for contracting/transmitting HIV. It focuses on the relationship between condom use self-efficacy and risk involvement, and examines the factors associated with greater/lower levels of condom use self-efficacy. The data come from a national sample of men, randomly chosen, who used any of 16 websites specifically to identify other men with whom they could engage in unprotected sex. Data were collected between January 2008 and May 2009 from 332 men, via telephone interviews. Multivariate analyses and structural equation modeling were used to test a conceptual model based on syndemics theory. Overall levels of condom use self-efficacy were fairly high, and self-efficacy was related inversely to involvement in HIV risk practices. Six factors were found to be indicative of levels of condom use self-efficacy: the number of drug problems experienced, sexual role identity as a “bottom,” not caring about the HIV serostatus of potential sex partners, experiencing childhood maltreatment, having confidence in HIV-related information provided in other men’s online profiles, and level of HIV knowledge. Condom use self-efficacy plays an integral role in HIV risk practices among high-risk men who have sex with men. This is true despite the fact that, overall, condom use self-efficacy levels were fairly high in this population.

Keywords: condom use self-efficacy, gay men, bisexual men, men who have sex with men (MSM), HIV risk behaviors, Internet

Introduction

In its simplest meaning, condom use self-efficacy refers to people’s level of confidence in their ability to use condoms. This construct has three major components to it. The first of these pertains to condom acquisition, and addresses issues regarding where to obtain free condoms or where to purchase condoms, and which type(s) of condoms one may use. The second of these components pertains to proper condom use, and addresses issues regarding how to check a condom’s packaging for an expiration date, knowing which lubricants one can/cannot use with a particular type of condom, knowing how to apply these lubricants to the condom, knowing how to apply the condom onto the genitalia, and knowing how to dispose of a condom once the sex has concluded and ejaculation has occurred. The third aspect of condom use self-efficacy pertains to negotiation skills, and addresses issues such as how to introduce the subject of condom use into a sexual relationship where, heretofore, condoms were not used, how to broach the subject of condom use with new sex partners, how to convince a partner who is reluctant to use condoms to give them a try, and how to avoid unwanted negative confrontations or potentially violent reactions from partners who are displeased with the subject of condom use. All of these various elements of people’s overall levels of condom use self-efficacy play an important role, and all of the factors must be considered if one is to understand a person’s overall condom use self-efficacy. Knowing where to obtain condoms does not necessarily mean that one knows how to use them.

Similarly, knowing how to use condoms properly does not necessarily mean that one knows how to introduce these devices into a sexual encounter with one’s sex partner. Knowing how to discuss condom use with a sex partner does not necessarily mean that one knows how to put on a condom correctly.

Although quite a few studies have been published in the scholarly literature since the year 2000 with respect to different aspects of condom use self-efficacy, especially how condom efficacy relates to involvement in sexual risk practices, the large majority of these reports have been based on samples of females or adolescents. Almost always, these studies have shown that higher rates of condom use self-efficacy are associated with lower rates of involvement in HIV-related risk practices (Alleyne, 2008; O’Leary, Jemmott, & Jemmott, 2008; Tucker, Elliott, Wenzel, & Hambarsoomian, 2007).

In contrast to the preceding, research on condom use self-efficacy among men who have sex with men (MSM), who are the subject of the present study, has been quite limited. Eaton, Cherry, Cain, and Pope (2011) examined changes in condom use self-efficacy levels among MSM following exposure to an HIV serosorting intervention. They found that condom use self-efficacy levels increased following exposure to the intervention, and that this effect lasted at least until the 3-month follow-up interval. Huebner, Davis, Nemeroff, and Aiken (2002) focused their attention on the relationship between internalized homophobia and both “mechanical condom use self-efficacy” and “communication condom use self-efficacy” in their sample of MSM in the Phoenix, Arizona metropolitan area. They found that men with greater levels of internalized homophobia responded less well to an HIV intervention designed to increase their levels of condom use self-efficacy.

As a result of the dearth of research on the subject of condom use self-efficacy among MSM, little is known about condom efficacy levels in this population and how, if at all, condom efficacy is related to HIV risk taking in this population. Do gay and bisexual men feel that they have the necessary skills to use condoms correctly? Are they confident in their ability to introduce condoms into their sexual relationships, or to discuss the possibility of using condoms with new sex partners? Is condom use self-efficacy (or the lack thereof) related to HIV risk taking in the MSM population? What factors underlie greater/lower levels of condom use self-efficacy among gay and bisexual men? The answers to these questions are unknown because research on this topic has been extremely limited. These questions form the main topics of inquiry for the present study, which examines condom use self-efficacy in one particular subsample of MSM that happens to be that is at very great risk for contracting and/or transmitting HIV.

Conceptual Model

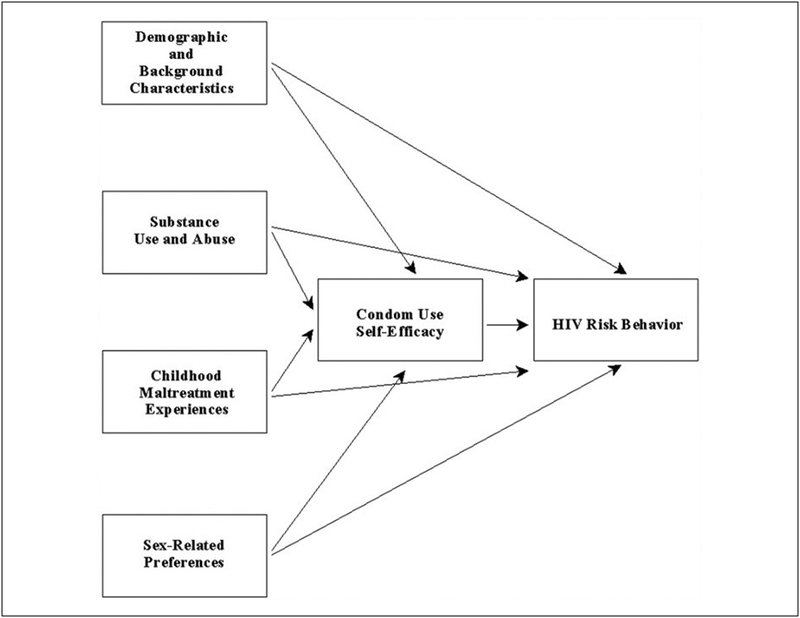

In the present article, a structural approach is used to develop a better understanding of how condom use self-efficacy affects HIV risk involvement in a sample of men who use the Internet specifically to find other men with whom they can engage in unprotected sex. Based on previously published studies, the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 was examined. In this exploratory model, condom use self-efficacy is hypothesized to have a direct effect on men’s involvement in risky practices. As the conceptual model shows, condom use self-efficacy is one of five types of influences hypothesized to affect men’s HIV risk practices, and is itself affected by the other four types. The others are demographic variables and other background characteristics (e.g., race/ethnicity, age, HIV serostatus), sex-related behavioral preferences (e.g., self-identification as a sexual “top” vs. a “bottom,” preferring to have sex that is “wild” or “uninhibited”), substance use/abuse, and childhood maltreatment experiences (e.g., sexual, physical, and emotional abuse, and physical and emotional neglect).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

To a great extent, this conceptual model owes its intellectual origins to the notion of syndemic and to syndemics theory. “Syndemic” refers to the tendency for multiple epidemics to co-occur and, for the various maladies to interact with one another, with each one worsening the effects of the others (Singer, 2009; Singer et al., 2006). Walkup et al. (2008) noted that health problems may be construed as syndemic when two or more conditions/afflictions are linked in such a manner that they interact synergistically, with each contributing to an excess burden of disease in a particular population. A number of authors, particularly during the past few years, have written about syndemics and syndemics theory as they apply to sexual risk taking and the HIV epidemic (Gielen et al., 2007; Mustanski, Garofalo, Herrick, & Donenberg, 2007; Romero-Daza, Weeks, & Singer, 2003; Senn, Carey, & Vanable, 2010; Singer et al., 2006), including specific mention of the applicability of the concept and theory to MSM (Klein, 2011b; Mustanski et al., 2007).

In terms of its relevance for the study of condom use self-efficacy among risk-taking MSM, syndemics theory would posit that there are numerous factors influencing how capable men feel about using condoms and/or convincing their sex partners to use condoms, and that some of these factors may interact with one another in terms of their effects on men’s overall levels of condom use self-efficacy. For example, childhood maltreatment experiences may have an impact on subsequent substance use/abuse practices and/or on mental health functioning such that previously-abused men may be more likely to have drug problems and/or to suffer from low self-esteem or greater levels of depression. These problems, in turn, may have an impact on the extent to which they feel confident in their ability to bring about condom use with their partners. Thus, by examining the conjoint effects of variables such as these—childhood maltreatment history, substance use/abuse, psychological functioning—Syndemics theory is likely to be an effective way of examining the role that condom use self-efficacy plays in the overall HIV risk profiles of risk-seeking MSM.

Method

This article draws from data that were collected between January 2008 and May 2009 for The Bareback Project, a study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The study sample consisted of men who use the Internet specifically to find other men with whom they could engage in unprotected sex. Men were recruited from 16 different websites. Some of the 16 websites catered exclusively to unprotected sex (e.g., Bareback.com, RawLoads.com). These sites accounted for 50.9% of the men subsequently recruited into the study. The other websites used did not cater to unprotected sex exclusively but did make it possible for site users to identify which individuals were looking for unprotected sex (e.g., Men4SexNow.com, Squirt.org). These sites supplied the remaining 49.1% of the men for the sample.

Recruitment

A nationwide sample of men was derived, with random selection of participants being based on a combination of the first letter of the person’s online username, his race/ethnicity (as listed in his profile), and the day of recruitment. Each day, members of the research staff working on recruitment had three letters or numerals assigned to them for their use that day. These letters and numerals were assigned randomly, using the software available at www.random.org (substituting the numbers 1 to 26 to represent, sequentially, the letters of the alphabet, and then using numbers after that to represent numerals). The first letter/numeral was restricted for use for recruiting Caucasian men only; the last two letters/numerals were used exclusively for recruiting men of color. (This oversampling technique for racial minority group men was adopted so as to compensate for the fact that men of color, especially African American men, are more difficult to recruit into research studies than their Caucasian counterparts are.) In order for a particular person to be approached and asked to participate in the study, these letters/numerals had to correspond to the first letter/numeral of that individual’s profile and that person’s race/ethnicity, as stated in his profile, had to be a match for the Caucasian-versus-racial-minority-group-member designation on the daily randomization listing.

On recruitment sites where it was possible to know who was online at the time the recruiter was working, selection of potential study participants came from the pool of men who happened to be logged onto the site during the time block when the recruiter was working. All men who were online at the time the recruiter was working and whose profile name began with the appropriate letter/numeral were eligible to be approached. On recruitment sites where it was not possible to know who was online at the time the recruiter was working, ZIP codes were used to narrow down the pool of men who could be approached. To do this, in addition to the daily three letters/numerals that were assigned randomly to each recruiter throughout the study, each day, 10 five-digit numbers were also assigned to each recruiter (five to be used for Caucasian men, five to be used for men of color). These five-digit numbers were random number combinations generated by the www.random.org software, and they were used in this study as proxies for ZIP codes. Recruiters entered the first five-digit number into the website’s ZIP code search field (which site users typically used to identify potential sex partners who resided within a specified radius from their residence), selected a 5-mile radius, and then viewed the profile names of all men meeting those criteria who had logged onto that site within the previous 24 hours. Those men were eligible to be invited to participate, and their profiles were reviewed for the letter/numeral match described above for men who were online at the time that recruiters were working.

Recruitment efforts were undertaken 7 days a week, during all hours of the day and nighttime, variable from week to week throughout the duration of the project. This was done to maximize the representativeness of the final research sample, in recognition of the fact that different people use the Internet at different times.

Participation

Initially, men were approached for participation either via instant message or e-mail (much more commonly via e-mail), depending on the website used. Potential participants were provided with a brief overview of the study and informed consent-related information, and they were given the opportunity to ask questions about the study before deciding whether or not to participate. Potential participants were also provided with a website link to the project’s online home page, to offer additional information about the project and to help them feel secure in the legitimacy of the research endeavor. Interested men were scheduled for an interview soon after they expressed an interest in taking part in the study, typically within a few days. To maximize convenience for participants, interviews were conducted during all hours of the day and night, 7 days a week, based on interviewer availability and participants’ preferences.

Participants in the study completed a one-time, confidential telephone interview addressing a wide array of topics. The decision to conduct the data collection via telephone interviews rather than via anonymous online surveys was made for a number of reasons. First, telephone interviews allowed the research team members to establish rapport with respondents, and this was deemed critical in light of the length of the questionnaire and the very personal nature of the questions being asked. Second, using telephone interviews enabled the research team to make sure that study participants understood all the questions (something that cannot be achieved when online survey techniques are used), and helped people to “think through” some of the more complex questions asked during the interview. Third, The Bareback Project was a mixed methods study, involving the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. The latter would have been precluded had only an online survey been implemented.

The questionnaire that was used for the study’s quantitative component (which serves as the basis for the data reported in the present research) was developed specifically for The Bareback Project. Many parts of the survey instrument were derived from standardized scales previously used and validated by other researchers. The interview covered subjects such as degree of “outness,” perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation, general health practices, HIV testing history and serostatus, sexual practices (protected and unprotected) with partners met online and offline, risk-related preferences, risk-related hypothetical situations, substance use, drug-related problems, Internet usage, psychological and psychosocial functioning, childhood maltreatment experiences, HIV/AIDS knowledge, and some basic demographic information.

The interviews lasted an average of 69 minutes (median = 63, SD = 20.1, range = 30–210). Participants who completed the interview were offered $35. Two payment options were available, one of which allowed men to maintain complete anonymity (PayPal) and one of which required them to provide a name and mailing address to receive payment (check). Approval of the research protocol was given by the institutional review boards at Morgan State University, where the principal investigator and one of the research assistants were affiliated, and George Mason University, where the other research assistant was located.

Measures Used

The main measure of condom use self-efficacy was a scale measure composed of 13 items adapted from the work of Brafford and Beck (1991). All items were scored using a 5-point Likert-type response set, with answers ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. The actual items comprising this scale are shown in Table 2. The scale assessing respondents’ overall levels of condom use self-efficacy was found to be reliable (Cronbach’s α = .86).

Table 2.

Condom Use Self-Efficacy Measures.

| Condom use self-efficacy measure | Disagree (%) | Neutral (%) | Agree (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| You feel confident in your ability to put a condom on yourself or your partner. | 10.6 | 7.0 | 82.4 |

| You feel confident you could purchase condoms without feeling embarrassed. | 4.6 | 1.8 | 93.6 |

| You feel confident in your ability to discuss condom usage with any partner you might have. | 6.4 | 6.1 | 87.5 |

| You feel confident in your ability to suggest using condoms with a new partner. | 18.8 | 18.5 | 62.6 |

| You would feel embarrassed to put a condom on yourself or your partner. | 3.9 | 8.5 | 87.6 |

| If you were to suggest using a condom to a partner, you would feel afraid that that person would reject you. | 10.1 | 14.1 | 75.8 |

| You would feel comfortable discussing condom use with a potential sexual partner before you ever had any sexual contact. | 8.2 | 6.1 | 85.8 |

| You would not feel confident suggesting using a condom with a new partner because you would be worried that person would think you have a sexually transmitted disease. | 10.3 | 9.1 | 80.6 |

| You feel confident that you could use a condom with a partner without “breaking the mood.” | 37.7 | 13.7 | 48.6 |

| You feel confident in your ability to put a condom on yourself or your partner quickly. | 19.5 | 14.3 | 66.2 |

| You feel confident you could use a condom during sex without reducing any sexual sensations. | 67.9 | 10.6 | 21.5 |

| You feel confident that you could use a condom successfully. | 10.6 | 4.3 | 85.1 |

| You feel confident you could stop to put a condom on yourself or your partner even in the heat of passion. | 21.8 | 13.3 | 64.9 |

Several HIV risk behavior outcome measures were examined in conjunction with the part of the analysis focusing on condom use self-efficacy and its relationship to risk taking. The measure used for the main structural equation modeling indicated the proportion of all anal sex acts (insertive and receptive) that involved the use of condoms. It was a continuous measure based on sexual behaviors reported during the 30 days prior to interview.1 Other risk behaviors (all of which used a past-30-days time frame) assessed included the proportion of all sex acts that involved the use of condoms (continuous), the proportion of all sex acts involving internal ejaculation (continuous), the proportion of all anal sex acts involving internal ejaculation (continuous), the number of sex partners (continuous), the number of times engaging in anonymous sex (continuous), the number of times having sex while under the influence of alcohol and/or other drugs (continuous), the number of times having sex that the person considered to be “wild” or “uninhibited” (continuous), the number of times having sex in public places such as parks, restrooms, or bookstores (continuous), and the number of times having sex that the respondent considered to be physically rough (continuous).

Demographic and background data included age (continuous), race/ethnicity (categorical), educational attainment (continuous), sexual orientation (gay vs. bisexual), HIV serostatus (HIV-positive vs. HIV-negative or serostatus unknown), preferred HIV serostatus of sex partners (must be HIV-positive, preferred to be HIV-positive, must be HIV-negative, preferred to be HIV-negative, does not matter), and sexual role identity (top, versatile top, versatile, versatile bottom, or bottom). In addition, respondents were asked about their level of confidence in the accuracy of HIV-related information they see/read in other men’s online profiles (ordinal, ranging from not at all confident to very confident); compared with other ways in which they meet men for sex, how often they used bareback-focused websites to find partners for sex (ordinal, ranging from much less to much more); and overall levels of knowledge about HIV/AIDS and HIV transmission (continuous scale measure, Kuder– Richardson20 = 0.76).

As the model depicted in Figure 1 shows, several substance abuse measures were examined as well. These included whether or not the person had used any illegal drugs during the month prior to interview (yes/no), total amount of illegal drug use during the previous 30 days (continuous measure, summing the quantity-frequency of use for nine different types of illegal drugs), and the number of symptoms of drug abuse and drug dependency experienced during one’s lifetime and during the past 30 days (both continuous scale measures, with items derived from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition–text revision [DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000]; Kuder– Richardson20 = 0.87 and 0.79, respectively).

A few items assessing men’s sex-related preferences were also included in these analyses. These were the extent to which men liked/preferred to have sex that was rough (continuous), the extent to which men liked/preferred to have sex that was “wild” or “uninhibited” (continuous), the extent to which men liked/preferred to have sex in public places (continuous), whether or not men liked to have anonymous sex (yes/no), and the extent to which men eroticized ejaculatory fluids (continuous scale measure; Cronbach’s α = .84).

Finally, childhood maltreatment experiences were assessed via the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein & Fink, 1998). These items enabled separate continuous scale measures to be developed to assess sexual abuse (Cronbach’s α = .93), physical abuse (Cronbach’s α = .85), emotional abuse (Cronbach’s α = .89), physical neglect (Cronbach’s α = .71), and emotional neglect (Cronbach’s α = .93) during men’s childhood and adolescent years, as well as an overall extent of maltreatment measure (Cronbach’s α = .94).

Analysis

Examination of the relationship between level of condom use self-efficacy and involvement in HIV-related risk practices was undertaken by computing simple correlation coefficients (Pearson’s r), because all the dependent and independent variables in question were continuous measures.

The next part of the analysis, focusing on the factors associated with engaging in unprotected anal sex, was undertaken in two steps. First, bivariate relationships were assessed for each of the independent variables outlined above and unprotected sex, using the latter as the dependent variable. Whenever the independent measure was dichotomous (e.g., sexual orientation, HIV-positive serostatus), Student’s t tests were used. Whenever the independent variable was continuous (e.g., educational attainment, age), simple regression was used. Then, all items found to be related either significantly (p < .05) or marginally (.10 > p > .05) to the extent to which men used condoms were entered into a multivariate equation, and then removed in stepwise fashion until a best fit model containing only statistically significant measures remained. A comparable approach was used to determine the multivariate measures that were associated with (i.e., predictive of) men’s levels of condom use self-efficacy.

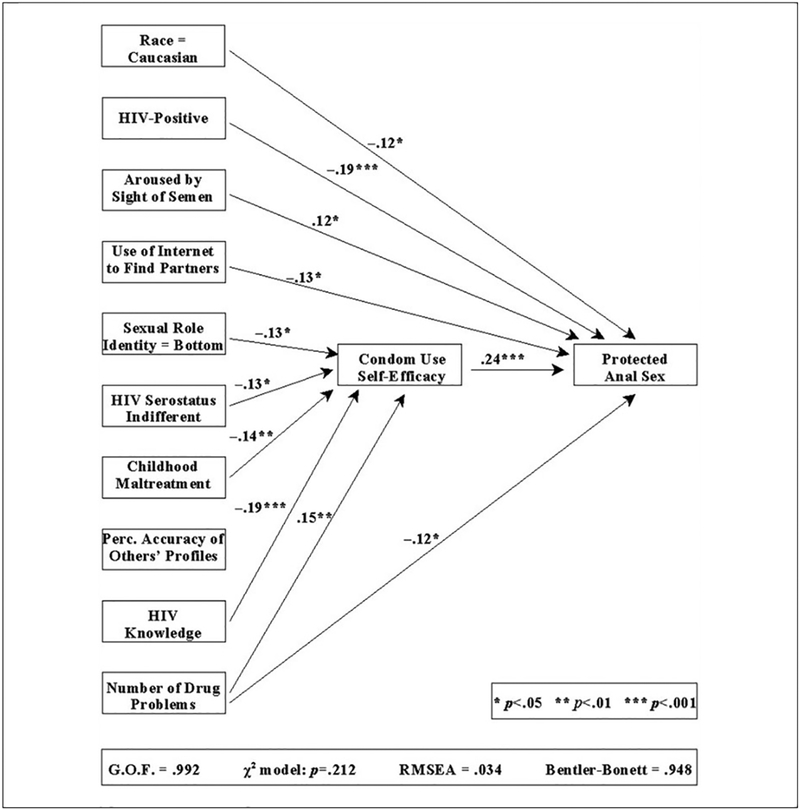

Subsequently, the relationships depicted in Figure 2 (which were the result of the bivariate and multivariate analyses described above) were subjected to a structural equation analysis to determine whether the way the relationships depicted there is an appropriate and effective representation of the study data. SAS’s PROC CALIS procedure was used to assess the overall fit of the model to the data. When we use this type of structural equation analysis, we look for several specific outcomes: (a) a goodness-of-fit index as close to 1.00 as possible, but no less than .90, (b) a Bentler–Bonett normed fit index value as close to 1.00 as possible, but no less than .90, (c) an overall chi-square value for the model that is statistically nonsignificant, preferably as far from attaining statistical significance as possible, and (d) a root mean square error of approximation value as close to .00 as possible, but no greater than .05. If these conditions are met, then the relationships depicted are considered to indicate a good fit with the data.

Figure 2.

Results of structural equation analysis.

Note. GOF = goodness of fit; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation.

Throughout all the analyses, results are reported as statistically significant whenever p < .05.

Results

Sample Characteristics

In total, 332 men participated in the study. They ranged in age from 18 to 72 years (mean = 43.7, SD = 11.2, median = 43.2; see Table 1). Racially, the sample was appropriately diverse, with 74.1% of the men being Caucasian, 9.0% each being African American and Latino, 5.1% self-identifying as biracial or multiracial, 2.4% being Asian, and 0.3% being Native American. The large majority of the men (89.5%) considered themselves to be gay and almost all of the rest (10.2%) said they were bisexual. On balance, men participating in The Bareback Project were fairly well-educated. About 1 man in 7 (14.5%) had completed no more than high school, 34.3% had some college experience without earning a college degree, 28.9% had a bachelor’s degree, and 22.3% were educated beyond the bachelor’s level. Slightly more than one-half of the men (59.0%) reported being HIV-positive; most of the rest (38.6%) were HIV-negative.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

| Characteristic | n | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–29 | 44 | 13.3 |

| 30–39 | 69 | 20.8 |

| 40–49 | 109 | 32.9 |

| 50–59 | 81 | 24.5 |

| 60+ | 28 | 8.5 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 246 | 74.1 |

| African American | 30 | 9.0 |

| Latino | 30 | 9.0 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 8 | 2.4 |

| Native American/Native Alaskan | 1 | 0.3 |

| Biracial/multiracial | 17 | 5.1 |

| Educational attainment | ||

| High school graduate or less | 48 | 14.5 |

| Some college | 1 14 | 34.3 |

| College graduate | 96 | 28.9 |

| Postgraduate | 74 | 22.3 |

| Population density in area of residence | ||

| Rural (<250 persons per square mile) | 76 | 22.9 |

| Urban (1,000+ persons per square mile) | 198 | 59.6 |

| Low density (1,000–2,500 persons) | (53) | (26.8) |

| Medium density (2,501–5,000 persons) | (67) | (33.8) |

| High density (5,001+ persons) | (78) | (39.4) |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married or “involved” | 87 | 26.2 |

| Single | 245 | 73.8 |

| HIV serostatus | ||

| Negative | 128 | 38.6 |

| Positive | 196 | 59.0 |

| Don’t know | 8 | 2.4 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Gay | 297 | 89.5 |

| Bisexual | 34 | 10.2 |

| Sexual role identity | ||

| Total top | 54 | 16.3 |

| Versatile top | 62 | 18.7 |

| Versatile | 60 | 18.1 |

| Versatile bottom | 92 | 27.7 |

| Total bottom | 64 | 19.3 |

Overall Levels of Condom Use Self-Efficacy

Overall, most men scored fairly high on the overall scale measure for condom use self-efficacy (mean = 3.75, SD = 0.61). Very few men (6.1%) had average scores indicating low levels of condom use self-efficacy (mean of 1.00–2.74 on the 1–5 scale) and only 13.0% more had scores equating to average overall levels of condom use self-efficacy (mean of 2.75–3.25 on the 1–5 scale). More than one-half of the men (58.0%) scored fairly high on this scale (mean of 3.26 to 4.25 on the 1–5 scale) and nearly one-quarter of the study participants (23.0%) were found to have very high levels of condom use self-efficacy overall (mean score of 4.26–5.00 on the 1–5 scale).

Table 2 presents participants’ responses to the various items comprising the condom use self-efficacy scale, with “agree” and “strongly agree” responses collapsed into a single category for simplicity in presentation and the same having been done for “disagree” and “strongly disagree” responses. On most dimensions, men were confident in their ability to use condoms correctly and/or to negotiate effectively for their use with their sex partners. There were a few notable exceptions to this, though. First, few men (21.5%) believed that they could use a condom during sex without reducing sexual sensations. Second, nearly one-half of the men (48.6%) believed that it would be difficult for them to use a condom without “breaking the mood” during sex. Third, more than one-third of the men (37.4%) lacked confidence in their ability to suggest using a condom with a new sex partner. A comparable percentage of the men (33.8%) expressed concern about their ability to put on a condom quickly, as oftentimes would be required during a sexual encounter.

Condom Use Self-Efficacy and HIV Risk Practices

Table 3 summarizes the findings obtained for analyses examining the relationship of condom use self-efficacy to involvement in various HIV risk practices. For all of the risk outcome measures examined except one (the exception being the number of times that men had engaged in sexual relations in public venues, such as parks, restrooms, or bookstores), condom use self-efficacy was related to risk involvement. In all instances, greater levels of self-efficacy corresponded with lesser involvement in risk. This was true for men’s overall rate of condom use (p < .001), their rates of condom use during anal sex (p < .001), the proportion of all sex acts involving internal ejaculation (p = .011), the proportion of anal sex acts involving internal ejaculation (p < .001), the number of times that men reported having engaged in “wild” or “uninhibited” sex (p = .008), the number of times that men had anonymous sex of any kind (p = .005), the number of times that men had sexual relations that they would describe as physically rough (p = .034), the number of sex partners men reported during the month prior to interview (p < .001), and the number of sex partners that men acknowledged having over the course of their lifetimes (p = .003). Additionally, greater condom use self-efficacy was associated with a reduced risk for engaging in sexual relations while under the influence of alcohol and/or other drugs (p = .002).

Table 3.

Condom Use Self-Efficacy and Involvement in HIV Risk Practices.

| HIV risk practice | Correlation coefficient (r) | p=|x| |

|---|---|---|

| Overall rate of condom use | .25 | <.00l |

| Condom use during anal sex | .30 | <.00l |

| Proportion of sex acts involving internal ejaculation | −.15 | .011 |

| Proportion of anal sex acts involving internal ejaculation | −.26 | <.00l |

| Engaging in any sex while “under the influence” | .51a | .002 |

| Number of times having “wild” or “uninhibited” sex | −.15 | .008 |

| Number of times having anonymous sex | −.15 | .005 |

| Number of times having sex in public places | −.04 | .451 |

| Number of times having rough sex | −.12 | .034 |

| Number of recent sex partners | −.21 | <.00l |

| Number of lifetime sex partners | −.17 | .003 |

Dichotomous measure used as dependent variable, so odds ratio rather than correlation coefficient presented.

As Figure 2 depicts, when multivariate analysis was performed, condom use self-efficacy was one of six measures found to be associated with the proportion of all anal sex acts involving the use of protection. This analysis revealed that, compared with members of other racial groups, Caucasians engaged in protected anal sex significantly less of the time (p = .038). Men who were infected with HIV engaged in higher rates of unprotected anal sex than their HIV-negative and serostatus-unknown counterparts (p < .001). The larger the number of drug abuse and drug dependency symptoms/problems that men had experienced, the lower their rates of protected anal sex tended to be (p = .041). The more that respondents reported using barebacking-focused websites on the Internet to find sex partners, the greater the proportion of their anal sex acts that were unprotected (p = .021). Finally, the greater men’s levels of condom use self-efficacy were, the greater their use of condoms during anal intercourse tended to be (p < .001). Together, these items explained 18.8% of the total variance.

Factors Associated With Condom Use Self-Efficacy

Figure 2 also shows the factors that were found to be associated with men’s levels of condom use self-efficacy, based on the multivariate analysis. In all, six items were identified and, together, they explained 15.9% of the total variance. First, the more drug abuse and drug dependency symptoms/problems that men had experienced, the lower their levels of condom use self-efficacy were (p = .002). Second, men who self-identified as sexual bottoms reported lower levels of condom use self-efficacy than their sexually versatile and sexually top counterparts did (p = .013). Third, compared with those who wanted to find partners who specifically were HIV-positive or HIV-negative, men who were indifferent to the HIV serostatus of their prospective sex partners were less confident in their ability to use condoms correctly and/or to negotiate for their use (p = .013). Fourth, the more sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, and/or emotional neglect men had experienced during their formative years, the lower their levels of condom use self-efficacy were at the time of interview (p = .006). Fifth, the more confidence men had in the accuracy of other men’s profiles on the Internet, the lower their levels of condom use self-efficacy tended to be (p < .001). Finally, the more knowledgeable men were regarding how HIV is transmitted, the greater their confidence in their ability to use condoms correctly and/or to negotiate for their use tended to be (p = .004).

Structural Equation Model

The data from the structural equation analysis revealed that the relationships depicted in Figure 2 are an appropriate way of characterizing the role that condom use self-efficacy plays in HIV risk taking in this population. The goodness-of-fit index for this model was 0.99—well above the 0.90 threshold desired to deem a model a good fit for the data. As sought in structural equation modeling, the overall chi-square test statistic for the model was non-significant (p = .212) and nowhere near attaining statistical significance. The root mean square error approximation estimate was .03—below the maximum acceptable value of .05. Finally, the Bentler-Bonett normed fit index was .95—comfortably above the minimum threshold of .90 that is used to indicate a good fit for the data.

Discussion

This study’s findings are indicative of what some people might interpret as a “good news, bad news” situation. The good news is that, on balance, men taking part in The Bareback Project felt confident in their ability to use condoms in a variety of situations and to negotiate for their use with their sex partners when they wanted to do so. The bad news is that, overwhelmingly, they did not avail themselves of these skills. Despite the fact that condom use self-efficacy levels were fairly high in this population, actual condom use rates were very low (averaging only 8.0% across all sexual practices and 17.1% for anal sex). The present study’s findings indicate that participants’ nonuse of condoms must be, for the most part, attributed to factors other than skills deficits with regard to the proper use of condoms and the ability to discuss condom use with prospective sex partners.

Nevertheless, the data revealed a few specific areas in which condom use self-efficacy could be improved in this population. For example, more than two-thirds of the study participants believed that it would not be possible for them to use a condom without losing sexual sensations. Although this is undoubtedly true when a direct comparison is made between the physical sensations of protected sex and the physical sensations of bareback sex, there are many new types of condoms on the marketplace nowadays that offer wearers heightened sensitivity. Durex offers “Extra Sensitive” condoms that are described as being “super thin to give you exceptional sensitivity.” Trojan offers “Ultra Thin” condoms that are marketed to consumers as being designed for “ultra sensation.” Kimono brand sells “MicroThin” condoms that are “38% thinner than regular condoms … [offering] maximum … sensitivity and feeling.” As newer products on the market, it is likely that the large majority of the men who participated in this study had never tried these particular condoms. Although their dislike of condoms is far-reaching, going well beyond the issue of diminished sensitivity (for further information about this, see Klein & Kaplan, 2012), it is possible that some of the men who currently eschew condom use might be willing to use these new ultrathin, ultrasensitive condoms at least occasionally if interventionists could convince them to give them a try.

As another example of an aspect of condom use self-efficacy that might be amenable to improvement pertains to this study’s finding that more than one-half of the men said that they were not confident that they could use a condom with a sex partner without “breaking the mood” during the sex. A number of community-based HIV prevention, education, and intervention programs around the United States have offered workshops about eroticizing safer sex, in an effort to teach members of the MSM community about specific strategies that can be undertaken to make condom use feel less disruptive, more playful, and more naturally integrated into the overall sexual scenario. Programs such as those offered by Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York City (Palacios-Jimenez & Shernoff, 1986), the Howard Brown Health Center in Chicago, and Project ARK in St. Louis are to be applauded, as are community-specific approaches such as AIDS Project Los Angeles’ Red Circle Project (targeting safer sex among Native Americans) and Bockting, Rosser, and Scheltema’s (1999) program targeting safer sex among transgendered persons. Likewise, in recent years, websites dedicated to promoting erotic safer sex have begun to appear on the Internet, and they offer great promise in combating HIV-risk taking among MSM. An excellent example of this may be found on the Washington, D.C.–based group’s DCFukit website, at http://www.dcfukit.org. Finding innovative ways to eroticize safer sex may be an important approach to changing how MSM think about condom use, and that, in turn, is likely to be an effective way of reducing their involvement in risky sexual practices.

As a third example, more than one-third of the men taking part in this study were not confident in their ability to negotiate for safer sex with a new sex partner. A number of studies have shown that partner communication skills are related inversely to HIV risk taking among MSM (Lo, Reisen, Poppen, Bianchi, & Zea, 2011; Prestage et al., 2006; Wilson, Diaz, Yoshikawa, & Shrout, 2009); and many scholars have spoken of the need to bolster partner communication skills among MSM in order to keep members of this population safe from HIV (Crepaz & Marks, 2003; Oster et al., 2011; Wilson et al., 2009). The present study’s data suggest that it would be worthwhile for HIV intervention programs to incorporate components designed to bolster partner communication skills. Working with men to increase their levels of comfort broaching the subjects of HIV serostatus, recency of HIV testing, and condom use; offering them specific strategies that they can use to bolster their chances of convincing a partner to engage in protected sex with them; and engaging in role-playing exercises that can provide men with on-the-spot feedback about their attempts to engage in safer sex-related discussion with potential partners are likely to be the most promising ways of accomplishing this. Taking this one step farther, Internet-based educational/prevention efforts could be used as well, to provide instruction about some of these techniques, which could be modeled by online actors. Interventionists might even consider availing themselves of gaming technology, to make such information fun and engaging for the MSM who are participating in these skills-building exercises.

In addition to the preceding, the present study also found that condom use self-efficacy was related quite closely and quite consistently (and always inversely) to a variety of HIV risk practices. This is consistent with other published reports (Fernandez-Esquer, Atkinson, Diamond, Useche, & Mendiola, 2004; Leonard, Markham, Bui, Shegog, & Paul, 2010; O’Leary et al., 2008), almost all of which have been based on populations other than MSM. Thus, one contribution that this research makes to the scientific community is documenting that condom use self-efficacy is related to risk taking among MSM, just as it has been shown to be related in other populations. This finding highlights the importance of finding creative, effective ways of boosting condom use self-efficacy levels among MSM, and suggests that accomplishing this may help facilitate reductions in HIV transmission in this population.

Understanding the factors that underlie greater/lesser condom use self-efficacy among MSM thus becomes an important endeavor, because knowing more about these factors can help identify subgroups within the broader MSM population that may need targeted intervention and/or specific behaviors that serve as markers for greater risk. The present study identified six such factors, each of which merits brief discussion.

First, the more that men were experiencing problems as a result of substance use/abuse, the lower their levels of condom use self-efficacy tended to be. There is a well-established association between substance use/abuse and involvement in risky sex among MSM (Carey et al., 2009; Halkitis, Mukherjee, & Palamar, 2009; Semple, Strathdee, Zians, & Patterson, 2009). The present study’s finding is consistent with these reports and expands on them by showing that it is not just risk practices per se that are affected by men’s substance (ab)use behaviors but also the belief and attitude structures that underlie these risk practices. In another report (Klein, 2011a), the present author has discussed the very high prevalence of substance use, substance abuse, and attendant drug-related problems among members of The Bareback Project population. These findings highlight the importance of providing substance abuse prevention education, drug abuse intervention services, and substance abuse treatment to men who use the Internet to find partners for unprotected sex. Other scholars as well have spoken of the need for these types of services among MSM (Kelly & Parsons, 2010; Mimiaga et al., 2008; Palamar, Mukherjee, & Halkitis, 2008); the present study supports their contention. Completing drug treatment has been shown to be effective at helping to reduce HIV risk practices in a variety of population groups (Booth et al., 2011; Metzger, Woody, & O’Brien, 2010), including MSM (Jaffe, Shoptaw, Stein, Reback, & Rotheram-Fuller, 2007; Shoptaw et al., 2008).

Second, men who self-identified as sexual “bottoms” reported lower levels of condom use self-efficacy than their “versatile” and “top” counterparts did. To some extent, this may reflect the sexual behaviors that coincide with adhering to those sexual role identities, as “bottom” men are more likely to make themselves sexually subservient to “top” partners or to allow the “tops” to have more control over what sexual acts occur, how they take place, and so forth (Hoppe, 2011). Although the sexual role identity classifications among MSM as “bottom,” “versatile,” or “top” have been acknowledged by other researchers doing HIV-related work (Hart, Wolitski, Purcell, Gomez, & Halkitis, 2003; Wei & Raymond, 2011), little has been documented in the scientific literature regarding differences among these groups with regard to their actual sexual risk behaviors or their beliefs or attitudes toward risk taking. The present study’s finding suggests that more attention needs to be dedicated to these self-identification labels among MSM and how they affect HIV risk. In particular, men who consider themselves to be sexual “bottoms” appear to be in need of targeted intervention when it comes to their skills vis-à-vis condom use and negotiating with sex partners for safer sex.

Third, condom use self-efficacy levels were significantly lower among men who said that they did not care about potential sex partners’ HIV serostatus, compared with men who specifically wanted to identify partners who were either HIV-positive or HIV-negative. When present, HIV serostatus indifference is highly problematic because it heightens the likelihood that men will not ask potential sex partners about their HIV testing history, about their HIV serostatus, or about the possibility of using condoms during sex. Many MSM experience this type of HIV serostatus indifference because they perceive HIV infection to be an inevitability (i.e., “No matter what I do, I will contract HIV eventually. It is beyond my control.”) and, therefore, choose not to devote worry or psychic energy to concerns about HIV transmission. Interventionists working with risk-seeking MSM such as those who participated in the present study might wish to develop program components/modules that address the importance of caring about one’s HIV serostatus, knowing one’s HIV serostatus, and discussing this subject with potential sex partners prior to having sex with them. Research has shown that, among MSM, having discussions regarding HIV serostatus is associated with lower levels of subsequent risk involvement (Bird, Fingerhut, & McKirnan, 2011; Parsons et al., 2005). Additionally, interventionists working with risk-seeking MSM might wish to incorporate/implement intervention components focusing on serosorting, that is, the practice of engaging in sexual relations exclusively with persons whose HIV serostatus matches one’s own. In recent years, numerous authors have discussed the viability of serosorting among MSM, generally reporting it to be a successful approach in helping “at risk” members of this population to reduce their risk for contracting or transmitting HIV (Grov et al., 2007; Halkitis, Moeller, & Pollock, 2008); although some studies have also spoken of the risks inherent in relying on serosorting as a primary HIV risk reduction technique and the need to educate MSM more completely about this behavior (e.g., see Eaton et al., 2011, and Kurtz, Buttram, Surratt, & Stall, 2012).

Fourth, greater levels of childhood maltreatment were associated with lower levels of condom use self-efficacy in adulthood in this sample. In numerous studies, experiences with physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse or neglect during men’s formative years have been linked to greater involvement in risky sexual behaviors in subsequent years (see, e.g., Gore-Felton et al., 2006; Mimiaga et al., 2009). In the present study, childhood maltreatment was linked with poorer condom use self-efficacy, which is associated closely with the extent to which men were involved in risky practices. This finding indicates a need to work with MSM who experienced maltreatment during their childhood and/or adolescent years, to help them to recover from the long-term, damaging effects of their abuse or neglect. Interventionists wishing to assist this population should have strong linkages established with local-area mental health professionals, so that men who want to get counseling can do so “on demand” and with the support of the community-based programs that are trying to help them reduce their risk for HIV.

Fifth, there was an inverse association between the extent to which men perceived online profile information regarding other men’s HIV serostatus to be accurate and the extent to which they felt confident in their ability to use condoms correctly or negotiate effectively for their use. It is possible that this finding reflects some aspect of facility or easiness of action. That is, simply accepting as truthful what one reads in another person’s online profile is much easier—and for many men, much more comfortablexthan reading that information and then using it to initiate a discussion based on that posted information. If men choose to operate on the assumption that what is posted online must be, or most likely is, truthful, then they absolve themselves of the duty of safeguarding their health by allowing the other person’s online information to make the sexual decisions for themselves. This is a risky assumption to make. HIV interventionists working with MSM who use the Internet to find sex partners—something that many HIV researchers readily acknowledge happens with great frequency nowadays, particularly when these men are seeking risky behaviors (Benotsch et al., 2011; Grov, Golub, & Parsons, 2010; Kakietek, Sullivan, & Heffelfinger, 2011)—could address this issue by talking with men about trust, the truthfulness of online information (especially information provided in sex-fostering websites’ profiles), and how to make better decisions about their sexual health when meeting potential sex partners online. As discussed above with regard to not caring about potential sex partners’ HIV serostatus, improving partner communication skills among online-using, risk-seeking MSM would be a beneficial thing for HIV intervention programs to undertake.

Finally, the more knowledgeable men were about how HIV is transmitted, the more confident they tended to be in their condom use and condom negotiation skills. It is possible that this finding is indicative of certain men taking their sexual health very seriously, and in so doing, they have tried to make themselves aware of how HIV can/cannot be transmitted while simultaneously trying to develop the skills necessary to maintain their own sexual health. If this is an accurate interpretation of the data, as the author believes it to be, then it suggests that condom use self-efficacy and knowledge about HIV transmission go hand in hand for many men because they are part and parcel of the same underlying phenomenon, namely, a desire to take personal responsibility for one’s sexual health. Although HIV-related knowledge has been found to be related weakly or inconsistently to actual risk behavior practices among MSM, providing these men with a solid understanding of what levels of risk coincide with the specific sexual and drug use behaviors in which they may engage remains an important cornerstone of HIV prevention with this population. In the absence of knowledge about how HIV is/not transmitted, it is not reasonable to expect men to be able to modify their behaviors in a direction indicative of greater personal safety. In The Bareback Project, men’s overall levels of HIV knowledge were moderate, with men answering approximately 11 out of 15 knowledge-related questions correctly. Almost all HIV intervention and prevention efforts include information about HIV transmission in their programmatic components, and the present study suggests that this is a wise thing to do.

Potential Limitations

Before concluding, the author wishes to acknowledge a few potential limitations of this research. First, the data in this study are based on uncorroborated self-reports. Therefore, it is unknown whether participants underre-ported or overreported their involvement in risky behaviors. The self-reported data probably can be trusted, however, as noted by other authors of previous studies with similar populations (Schrimshaw, Rosario, Meyer-Bahlburg, & Scharf-Matlick 2006). This is particularly relevant for self-reported measures that involve relatively small occurrences (e.g., number of times having a particular kind of sex during the previous 30 days), which characterize the substantial majority of the data collected in this study (Bogart et al., 2007). Other researchers have also commented favorably on the reliability of self-reported information in their studies regarding topics such as condom use (Morisky, Ang, & Sneed, 2002).

A second potential limitation is the possibility of recall bias. For most of the measures used, respondents were asked about their beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors during the past 7 or 30 days. These time frames were chosen specifically: (a) to incorporate a large enough time frame in order to facilitate meaningful variability from person to person and (b) to minimize recall bias. Although the author cannot determine the exact extent to which recall bias affected the data, other researchers who have used similar measures have reported that recall bias is sufficiently minimal that its impact on study findings is likely to be negligible (Kauth, St. Lawrence, & Kelly, 1991; Napper, Fisher, Reynolds, & Johnson, 2010). This seems to be especially true when the recall period is small (Fenton, Johnson, McManus, & Erens, 2001; Weir, Roddy, Zekeng, & Ryan, 1999), as was the case for most of the main measures used in the present study.

Conclusion

Most of the men who participated in this study were fairly confident in their ability to use condoms properly and/or to negotiate for their use in an effective manner. Higher levels of condom use self-efficacy were found to be associated with a reduced chance for involvement in a variety of HIV risk practices, and condom use self-efficacy was identified as being one of the main multivariate predictors of the proportion of all anal sex acts that involved the use of protection. Consistent with the syndemics theory conceptual model underlying this research, condom use self-efficacy was one of several factors that affected risk involvement, and self-efficacy levels themselves were influenced by a number of factors (substance abuse, sexual role identity, childhood maltreatment experiences, etc.). It is important to be cognizant of these factors, for they have important implications for HIV prevention and intervention among men who use the Internet to find other men with whom they can engage in unprotected sex.

Acknowledgment

The author wishes to acknowledge, with gratitude, the contributions made by Thomas P. Lambing to this study’s data collection and data entry/cleaning efforts.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This research (officially titled Drug Use and HIV Risk Practices Sought by Men Who Have Sex with Other Men, and Who Use Internet Websites to Identify Potential Sexual Partners) was supported by a grant (5R24DA019805) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Although a measure assessing the total number of times a man reported having unprotected anal sex during a particular time period is a direct measure of risk, the author believes that the chosen measure, which assesses the proportion of anal sex acts that are unprotected, is a better measure because it indicates a person’s likelihood of having unprotected sex across time points. The latter indicates his “usual” practices and tendencies, whereas the former indicates his practices during a specific period that may or may not represent his “usual” sexual opportunities. The number of sexual encounters will increase or decrease during different time periods for the men in this study due to situational influences; thus, basing the risk assessment on the total number of unprotected sexual acts would miss this variation. Consequently, using the proportion of the sexual acts that were unprotected offers a better indication of this behavior when the men are engaging in their “typical” number of sexual encounters as well as for the times when their number of encounters increases or decreases.

References

- Alleyne B (2008). HIV risk behaviors among a sample of young Black college women. Journal of HIV/AIDS & Social Services, 7, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text rev.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Benotsch EG, Martin AM, Espil FM, Nettles CD, Seal DW, & Pinkerton SD (2011). Internet use, recreational travel, and HIV risk behaviors in men who have sex with men Journal of Community Health, 36, 398–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, & Fink L (1998). Childhood Trauma Questionnaire: A retrospective self-report manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bird JDP, Fingerhut DD, & McKirnan DJ (2011). Ethnic differences in HIV-disclosure and sexual risk. AIDS Care, 23, 444–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Rosser BRS, & Scheltema K (1999). Transgender HIV prevention: Implementation and evaluation of a workshop. Health Education Research, 14, 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart LM, Walt LC, Pavlovic JD, Ober AJ, Brown N, & Kalichman SC (2007). Cognitive strategies affecting recall of sexual behavior among high-risk men and women. Health Psychology, 26, 787–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Campbell BK, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Tillotson CJ, & McCarty D (2011). Reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among injection drug users in residential detoxification. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 30–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brafford LJ, & Beck KH (1991). Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. College Health, 39, 219–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey JW, Mejia R, Bingham T, Ciesielski C, Gelaude D, Herbst JH, & Stall R (2009). Drug use, high-risk sex behaviors, and increased risk for recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chicago and Los Angeles. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 1084–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, & Marks G (2003). Serostatus disclosure, sexual communication and safer sex in HIV-positive men. AIDS Care, 15, 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Cherry C, Cain D, & Pope H (2011). A novel approach to prevention for at-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men: Creating a teachable moment to promote informed sexual decision-making. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 539–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, & Erens B (2001). Measuring sexual behaviour: Methodological challenges in survey research. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 77, 84–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Esquer ME, Atkinson J, Diamond P, Useche B, & Mendiola R (2004). Condom use self-efficacy among U.S.- and foreign-born Latinos in Texas. Journal of Sex Research, 41, 390–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen AC, Ghandour RM, Burke JG, Mahoney P, McDonnell KA, & O’Campo P (2007). HIV/AIDS and intimate partner violence: Intersecting women’s health issues in the United States. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 8, 178–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore-Felton C, Kalichman SC, Brondino MJ, Benotsch EG, Cage M, & DiFonzo K (2006). Childhood sexual abuse and HIV risk among men who have sex with men: Initial test of a conceptual model. Journal of Family Violence, 21, 263–270. [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, DeBusk JA, Bimbi DS, Golub SA, Nanin JE, & Parsons JT (2007). Barebacking, the Internet, and harm reduction: An intercept survey with gay and bisexual men in Los Angeles and New York City. AIDS and Behavior, 11, 527–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grov C, Golub SA, & Parsons JT (2010). HIV status differences in venues where highly sexually active gay and bisexual men met sex partners: Results from a pilot study. AIDS Education and Prevention, 22, 496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Moeller RW, & Pollock JA (2008). Sexual practices of gay, bisexual, and other nonidentified MSM attending New York City gyms: Patterns of serosorting, strategic positioning, and context selection. Journal of Sex Research, 45, 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Mukherjee PP, & Palamar JJ (2009). Longitudinal modeling of methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors in gay and bisexual men. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart TA, Wolitski RJ, Purcell DW, Gomez C, & Halkitis P (2003). Sexual behavior among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: What’s in a label? Journal of Sex Research, 40, 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe T (2011). Circuits of power, circuits of pleasure: Sexual scripting in gay men’s bottom narratives. Sexualities, 14, 193–217. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Davis MC, Nemeroff CJ, & Aiken LS (2002). The impact of internalized homophobia on HIV preventive interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 326–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe A, Shoptaw S, Stein JA, Reback CJ, & Rotheram-Fuller E (2007). Depression ratings, reported sexual risk behaviors, and methamphetamine use: Latent growth curve models of positive change among gay and bisexual men in an outpatient treatment program. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 15, 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakietek J, Sullivan PS, & Heffelfinger JD (2011). You’ve got male: Internet use, rural residence, and risky sex in men who have sex with men recruited in 12 U.S. cities. AIDS Education and Prevention, 23, 118–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauth MR, St.Lawrence JS, & Kelly JA (1991). Reliability of retrospective assessments of sexual HIV risk behavior: A comparison of biweekly, three-month, and twelve-month self-reports. AIDS Education and Prevention, 3, 207–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BC, & Parsons JT (2010). Prevalence and predictors of non-medical prescription drug use among men who have sex with men. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 312–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H (2011a). Substance use and abuse among men using the Internet specifically to find partners for unprotected sex. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 43, 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H (2011b). Using a syndemics theory approach to study HIV risk taking in a population of men who use the Internet to find partners for unprotected sex. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 466–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein H, & Kaplan RL (2012). Condom use attitudes and HIV risk among American MSM seeking partners for unprotected sex via the Internet. International Public Health Journal, 4, 419–434. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz SP, Buttram ME, Surratt HL, & Stall RD (2012). Resilience, syndemic factors, and serosorting behaviors among HIV-positive and HIV-negative sub stance-using MSM. AIDS Education and Prevention, 24, 193–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard AD, Markham CM, Bui T, Shegog R, & Paul ME (2010). Lowering the risk of secondary HIV transmission: Insights from HIV-positive youth and health care providers. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42, 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo SC, Reisen CA, Poppen PJ, Bianchi FT, & Zea MC (2011). Cultural beliefs, partner characteristics, communication, and sexual risk among Latino MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 15, 613–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Woody GE, & O’Brien CP (2010). Drug treatment as HIV prevention: A research update. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 55, s32–s36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Noonan E, Donnell D, Safren SA, Koenen KC, Gortmaker S, & Mayer KH (2009). Childhood sexual abuse is highly associated with HIV risk-taking behavior and infection among MSM in the EXPLORE study. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51, 340–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Vanderwarker R, Gaucher MJ, O’Connor CA, Medeiros MS, & Safren SA (2008). Polysubstance use and HIV/STD risk behavior among Massachusetts men who have sex with men accessing Department of Public Health mobile van services: Implications for intervention development. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 22, 745–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Ang A, & Sneed CD (2002). Validating the effects of social desirability on self-reported condom use behavior among commercial sex workers. AIDS Education and Prevention, 14, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Garofalo R, Herrick A, & Donenberg G (2007). Psychosocial health problems increase risk for HIV among urban young men who have sex with men: Preliminary evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 34, 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napper LE, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, & Johnson ME (2010). HIV risk behavior self-report reliability at different recall periods. AIDS and Behavior, 14, 152–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Jemmott LS, & Jemmott JB III. (2008). Mediation analysis of an effective sexual risk-reduction intervention for women: The importance of self-efficacy. Health Psychology, 27, s180–s184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster AM, Dorell CG, Mena LA, Thomas PE, Toledo CA, & Heffelfinger JD (2011). HIV risk among African American men who have sex with men: A case-control study in Mississippi. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 137–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palacios-Jimenez L, & Shernoff M (1986). Facilitator’s guide to eroticizing safer sex: A psychoeducational workshop approach to safer sex education. New York, NY: Gay Men’s Health Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Palamar JJ, Mukherjee PP, & Halkitis PN (2008). A longitudinal investigation of powder cocaine use among club-drug using gay and bisexual men. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 69, 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Schrimshaw EW, Bimbi DS, Wolitski RJ, Gomez CA, & Halkitis PN (2005). Consistent, inconsistent, and non-disclosure to casual sexual partners among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS, 19, s87–s97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prestage G, Mao L, McGuigan D, Crawford J, Kippax S, Kaldor J, & Grulich AE (2006). HIV risk and communication between regular partners in a cohort of HIV-negative gay men. AIDS Care, 18, 166–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Daza N, Weeks M, & Singer M (2003). “Nobody gives a damn if I live or die”: Violence, drugs, and street-level prostitution in inner-city Hartford, Connecticut. Medical Anthropology, 22, 233–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Rosario M, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, & Scharf-Matlick AA (2006). Test-retest reliability of self-reported sexual behavior, sexual orientation, and psycho-sexual milestones among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 225–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Zians J, & Patterson TL (2009). Sexual risk behavior associated with co-administration of methamphetamine and other drugs in a sample of HIV-positive men who have sex with men. American Journal on Addictions, 18, 65–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn TE, Carey MP, & Vanable PA (2010). The intersection of violence, substance use, depression, and STDs: Testing of a syndemic pattern among patients attending an urban STD clinic. Journal of the National Medical Association, 102, 614–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoptaw S, Reback CJ, Larkins S, Wang PC, Rotheram-Fuller E, Dang J, & Yang X (2008). Outcomes using two tailored behavioral treatments for substance abuse in urban gay and bisexual men. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 35, 285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer M (2009). Introduction to syndemics: A systems approach to public and community health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, & Nicolaysen AM (2006). Syndemics, sex and the city: Understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 2010–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Elliott MN, Wenzel SL, & Hambarsoomian K (2007). Relationship commitment and its implications for unprotected sex among impoverished women living in shelters and low-income housing in Los Angeles County. Health Psychology, 26, 644–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walkup J, Blank MB, Gonzalez JS, Safren S, Schwartz R, Brown L, & Schumacher JE (2008). The impact of mental health and substance abuse factors on HIV prevention and treatment. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 47(Suppl. 1), S15–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei C, & Raymond HF (2011). Preference for and maintenance of anal sex roles among men who have sex with men: Sociodemographic and behavioral correlates. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir SS, Roddy RE, Zekeng L, & Ryan KA (1999). Association between condom use and HIV infection: A randomised study of self reported condom use measures. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 53, 417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson PA, Diaz RM, Yoshikawa H, & Shrout PE (2009). Drug use, interpersonal attraction, and communication: Situational factors as predictors of episodes of unprotected anal intercourse among Latino gay men. AIDS and Behavior, 13, 691–699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]