Abstract

Physical activity is an important component of a healthy lifestyle for all adults and especially for older adults. Using information from the updated 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines, 3 dimensions of physical activity are identified for older adults. These include increasing aerobic activity, increasing muscle-strengthening activity, and reducing sedentary or sitting behavior. Although the overall goal of the physical activity recommendations is to prevent chronic diseases and conditions from developing, many older adults are already affected. Therefore, suggested types of physical activity are described for specific diseases and conditions that are designed to mediate the condition or prevent additional disability. Finally, barriers to participation in physical activity specific to older adults are described, and possible solutions offered. Encouraging older adults to continue or even start a physical activity program can result in major health benefits for these individuals.

Keywords: barriers, chronic disease, muscle strengthening, older adults, physical activity, sedentary behavior

‘Although there is general agreement that physical activity is important for adults of all ages, it is not quite as clear how active older adults need to be, what types of activity are most important to do as a person ages, and how to encourage older adults to become or continue to be physically active.’

Introduction

Physical activity is an important component of a healthy life for children and adults, and especially for older adults. Although there is general agreement that physical activity is important for adults of all ages, it is not quite as clear how active older adults need to be, what types of activity are most important to do as a person ages, and how to encourage older adults to become or continue to be physically active. This article reviews the latest information on the value of physical activity, the appropriate types of physical activity at different health levels, and most important, factors that influence physical activity with a particular focus on older adults.

Typically, the term older adult applies to anyone older than 65 years, and much of the literature on physical activity and health follows this definition. However, because health varies substantially across chronological ages and may affect a person’s ability to participate in physical activity at any age, information in this article may apply to younger adults, especially those with chronic conditions.

How Much Physical Activity Is Recommended?

In 1995, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in collaboration with the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) developed the first general guidelines specifying how active adults should be to achieve health benefits.1 Other reports followed, and all agreed that participating in health-enhancing physical activity daily was optimal and that the intensity should be at a moderate level or higher. Although there are several ways to assess the intensity of an activity, the one that is most commonly used in a public health setting is the description of the activity. For example, moderate intensity would be described as walking briskly, whereas a higher intensity, usually referred to as vigorous intensity, would be described as running or jogging. Using these descriptors, the general guidelines were that all adults should obtain 30 minutes per day at least 5 days per week of at least moderate-intensity activity1 or 150 minutes per week of at least moderate-intensity activity.2 At the time, none of the reports dealt specifically with older adults. Through the years, additional research has informed the process, and in 2008, an expert panel met to update the recommendations based on the latest studies and included specific information for older adults.3 The expert panel also determined that it was acceptable to combine aerobic activities of different types and intensities into a single measure of physical activity. Therefore, the recommended amount of physical activity was expanded to 30 to 60 minutes per day of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity on 5 or more days of the week for most health benefits, such as lower risk for all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes. Whereas most health benefits were achieved with about 2.5 weekly hours of physical activity, the amount of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity most consistently associated with significantly lower rates of colon and breast cancer and the prevention of unhealthy weight gain is in the range of 3 to 5 hours per week.3

Although much focus has been on aerobic activity, the updated guidelines emphasize that other dimensions of the activity spectrum are perhaps even more important as people age. These include resistance and balance activities. Most evidence supports older adults participating in balance training and muscle-strengthening activities for 30 minutes per session, twice a week.3

Regardless of time spent being physically active, reducing time spent without doing any physical activity at all (sedentary behavior) is an important component of an overall active lifestyle. The concept of sedentary behavior has changed over the past few years. Whereas it was previously measured and defined as time spent not being physically active, new studies have identified that contiguous time spent sitting can have multiple negative health effects in spite of the amount of physical activity that is done during the rest of the day. These negative effects are seen in terms of risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD)4 and overall mortality.5 However, the exact amount of “sitting” behavior associated with poor health outcomes is difficult to assess. A review published in 2014 found only 2 articles deemed to be of high quality addressing this matter,6 but did find a strong protective effect on overall mortality for older individuals who sat less than 8 hours per day.7 Another study found that older adults who were consistently sedentary over the 2-year study period had higher overall mortality than those who became less sedentary.8 This is an area where more research is needed and is currently under way.

In summary, there are 3 measures needed to define an appropriately active lifestyle for older adults: time spent in aerobic activity, time spent doing muscle strengthening activities, and time spent in sedentary (sitting/laying) behavior. A listing of general guidelines for older adults, adapted from the expert panel recommendations, is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key Guidelines for Older Adults.a

| General aerobic guidelines |

| • All older adults should avoid inactivity. Some physical activity is better than none |

| • For health benefits, older adults should do at least 150 weekly minutes (2½ hours) of moderate-intensity (brisk walking) or 75 minutes (1 hour and 15 minutes) a week of vigorous-intensity (running or jogging) aerobic physical activity, or an equivalent combination. Aerobic activity should be performed in episodes of at least 10 minutes and spread throughout the week |

| • When older adults cannot do 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic activity a week because of chronic conditions, they should be as physically active as their abilities and conditions allow |

| • For additional and more extensive health benefits, older adults should increase their aerobic physical activity to 300 minutes (5 hours) a week of moderate-intensity or 150 minutes a week of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination |

| • Older adults with chronic conditions should understand whether and how their conditions affect their ability to do regular physical activity safely |

| Muscle strengthening guidelines |

| • Older adults should also do muscle-strengthening activities that are moderate or high intensity and involve all major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week |

| • Sedentary time guidelines |

| • Older adults should reduce sitting time regardless of how much time is spent doing physical activity |

Adapted from the 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter5.aspx.

Health Effects of Physical Activity

Using evidence gathered by the expert panel, it was determined that compared with inactive persons, active men and women have lower rates of all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, stroke, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, colon cancer, breast cancer, and depression.3 Physical activity in older adults is essential to minimize the effects of chronic disease, prevent complications from existing diseases, and reduce the risk of disability. Unfortunately, unhealthy lifestyle choices of older adults, including poor diet or limited physical activity, are often long-established behavior patterns. However, even though the best health outcomes involve being physically active throughout the life span, there are significant health benefits that accrue even when starting a physical activity program late in life.9

How Active Are Older Adults?

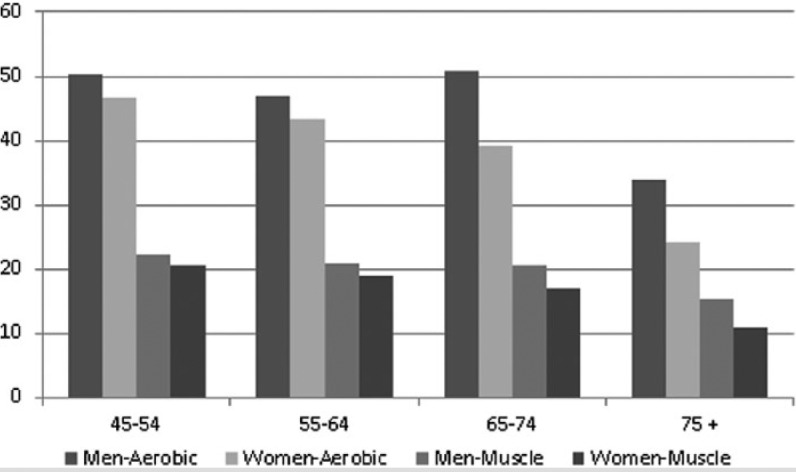

Many national surveillance systems collect physical activity data on the prevalence of physical activity. As is the case with most epidemiology studies on physical activity and health, this information is primarily self-reported. However, much of the data describing health benefits associated with physical activity also use self-reported data. Applying the 2008 guidelines to national data from 2012,9 it was found that men are more active than women at all age groups, including 45 to 54, 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 years and older (see Figure 1). This is true for both aerobic and muscle strengthening activities. Prior to 75 years, the prevalence of aerobic activity is between 40% and 50% and strengthening activities are around 18% to 20% for both men and women. From 75 years onward, the prevalence declines sharply for both aerobic and muscle strengthening activities, such that only 11% of women and 15% of men participate weekly in 2 or more days of muscle strengthening activities.

Figure 1.

Participation in Aerobic and Muscle-Strengthening Activities National Health Interview Survey, Adults 45-75+, United States, 2012.a

Physical Activity Among Adults With Chronic Disease

Much physical activity research focuses on the apparently healthy adult, but the vast majority of older adults are affected by chronic disease. It is known that 92% of adults older than 65 years are living with at least 1 chronic disease,10 and 62% are living with 2 or more chronic diseases.11 Chronic disease and multimorbidity can have negative effects on overall health, mobility, and functional independence.12 However, regular engagement in physical activity can have significant health benefits for older adults living with chronic diseases. Regular physical activity may contribute to slower disease progression, reduced complications and comorbidities, and reduced incident disability for adults already affected by chronic disease.12 In addition to its health benefits in secondary and tertiary prevention, physical activity may be considered a treatment strategy for some chronic conditions, including CVD,13 type 2 diabetes,14 and arthritis.15,16 The health benefits of physical activity in adults with chronic disease appear to differ across diagnoses, necessitating additional evidence to better understand the intensity and dosage necessary for such health benefits.12

Evidence is mounting regarding health benefits of physical activity for older adults living with chronic diseases. However, disease-related impairments may impede persons with chronic conditions from performing physical activity. Physical, sensory, psychosocial, and cognitive impairments may contribute to limitations in physical functional status or reduction in capacity to safely negotiate within the home or community environment. Physical impairments, including weakness, spasticity, or joint pain, often lead directly to functional limitations in mobility. However, sensory, psychosocial, and cognitive functions also play a vital role in mobility and community participation. For example, sensory limitations such as visual deficits or hearing impairments are associated with reduced safety and independence in activities of daily living, difficulty in community mobility, and restricted community participation.17-19 Cognitive impairments, common in chronic diseases, including multiple sclerosis, stroke, and Parkinson’s Disease, can contribute to reduced safety with community negotiation20,21 and community participation restriction22 and may necessitate caregiver assistance for successful participation in physical activity.23 Motivation to engage in physical activity may be affected by psychosocial impairments, including depressive symptoms or anxiety; both are linked with reduced mobility and community participation in older adults.17,20,24 In addition to health impairments resulting from the disease itself, the effect of pharmacological treatment of the disease may contribute to functional limitations. It is known that 40% of adults older than 65 years are taking more than 5 different medications per month; the risks of potentially inappropriate medications, side effects, and drug-drug interactions increase with multiple medication use.25-27 Polypharmacy in the older adult may affect alertness, balance, or coordination,27 which results in higher fall risk and contributes to additional activity restriction.25,27

Impairments associated with chronic disease can result in reduced participation in physical activity and increased time in sedentary positions creating cyclic pattern of inactivity and further health deteriorations.28,29 Mobility is central to healthy aging30 and has a strong inverse association with chronic disease.31 Integrating research of health impairments specific to older adults with that of environmental factors is instrumental to developing a public health approach to enhance mobility and physical activity among older adults.32 Additional research into the social, biological, behavioral, and environmental components of physical activity, mobility limitations, and their relationship to chronic disease is warranted to support development of effective strategies for physical activity promotion in the older adult.

For adults older than 65 years in the United States, the most prevalent chronic conditions include arthritis, CVD, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), osteoporosis, cancer, depression, and cognitive impairment. The following section discusses current evidence linking physical activity with primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of each of these common conditions. Disease-specific recommendations or guidelines for physical activity may increase participation and adherence and are addressed for each condition.

Arthritis and Osteoarthritis

Arthritis is the most commonly reported cause of disability in the older adult, affecting 49.7% of adults older than 65 years, according to data from the 2010-2012 National Health Interview Survey.33 Osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis, is characterized by a degeneration of joint space and articular cartilage causing joint pain. Decreased strength and muscular imbalance are risk factors for developing OA, with lack of physical activity a potential contributing cause.34 Joint pain with arthritis often leads to self-restriction of physical activity. Less than 60% of persons with OA meet the recommendations for 150 minutes of moderate-vigorous physical activity per week, and only 30% of persons with OA take at least 10 000 steps daily.35 Activity avoidance leads to a cyclic pattern of deconditioning and additional muscle weakening, further reducing the muscular support and shock absorption about the joint and contributing to increased pain.34,36

Maintaining or increasing physical activity can help reduce pain or functional limitations among those at risk for or those with a diagnosis of OA. In a prospective study of 1788 adults older than 50 years of age with or at risk of OA, each additional 1000 steps taken per day represented a 16% reduction of incident functional limitation over a 2-year period.37 Even modest improvements in reducing sedentary behavior can have profound effects in attenuating the risk of future disability. As compared with a sedentary lifestyle, a daily accumulation of 40 minutes of daily, light physical activity has been shown to decrease risk of disability in activities of daily living by 42% to 53% in community-dwelling adults with or at risk of OA.38 Focus toward reducing sedentary behavior and maintaining physical activity, particularly early in the disease process, can reduce functional limitations and disability over time.

In addition to the effects of physical activity in slowing the progression of disease, physical exercise, a subset of physical activity, is recommended as a first-line treatment for OA by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International and American College of Rheumatology.15,16 Exercise targeted at increasing strength and muscular balance is indicated to reduce pain and improve function. Progressive strength training, with or without weight bearing, has been shown to reduce pain and increase quality of life.39 Historically, aquatic exercises were recommended to help reduce the loading through painful joints. However, more recent research shows that land-based exercise may have superior results in increasing strength, controlling pain, and improving quality-of-life benefits as compared with aquatic therapy.40,41 Yet for some individuals who are severely limited by pain with weight-bearing, aquatic exercise may be necessary initially to increase physical activity tolerance.

Osteoporosis

Bone loss increases with age in both men and women, but postmenopausal women are at particularly increased risk of osteopenia or osteoporosis. According to data from NHANES 2005-2006, 49% of women older than 50 years have osteopenia, and 10% have osteoporosis at the femur neck; 30% of men older than 50 years have osteopenia at the femur neck.42 Sedentary behavior increases the risk of low bone mineral density (BMD) in older women.43 In women, the effects of sedentary behavior on BMD are independent of physical exercise behavior, and longer durations of uninterrupted sedentary behavior are more strongly associated with lower BMD as compared with total daily sedentary time.43 Interestingly, sedentary behavior in men does not appear to have the same association with lowered BMD.43 Moderate levels of habitual physical activity are beneficial for bone health in older adults, and correspond to a decreased rate of bone loss over time in both men and women.44,45

Weight-bearing activities have long been recommended as treatment for low BMD in adults with osteopenia or osteoporosis. However, although evidence exists that body-weight-supported exercise can improve BMD in select populations, the literature regarding improvements in bone density among postmenopausal women is conflicting.46,47 High-load strength training exercise appears to be more effective in reducing bone loss in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis when compared with low-load endurance exercise; in some studies, high-load strength training interventions resulted in an improvement in BMD.46,48 Walking programs, although providing other health benefits, demonstrate no impact on BMD in postmenopausal women.49 A systematic review of exercise and BMD in middle-aged and older men found similar results of potential osteogenic benefits with impact-loading activities but limited effect of walking on bone density.50

In addition to potential benefits in bone density, exercise focused on improving balance is essential to reduce the risk of falls and fracture in the older adults with brittle bones. Reduced leg power is associated with increased risk of falls in older adults with osteoporosis.51 Lower-extremity strength training is recommended in this population. Furthermore, reduced fear of falling and frequency of falls as well as improved balance can be achieved in older adults with osteoporosis through balance exercises.52 Multicomponent exercise programs that incorporate strength and balance training together appear to be most effective at improving balance and reducing falls.53,54 Strength training in combination with balance exercises is highly recommended for prevention of falls in adults with osteoporosis, and reduces the risk of fractures and potential serious medical complications in older adults.

Cardiovascular Disease

Cardiovascular disease is a term inclusive of a number of medical diagnoses, including coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral artery disease, hypertension, heart failure, and myocardial infarction. The burden of disease from CVD among older adults is high. In 2010, more than 70% of both men and women older than 65 years were diagnosed with CVD.55 Sedentary behavior has been consistently associated with increased incidence of CVD and increased risk of cardiovascular death.56,57 For adults with risk factors for CVD, physical activity is recommended as a first-line intervention to prevent development of disease. Among adults already diagnosed with CVD, habitual physical activity as an adjunct to pharmacological intervention can reduce the risk of cardiac events, cardiac mortality, or all-cause mortality. Adults with CVD who have high levels of physical activity have less than half the risk of CVD events and nearly a 75% reduction in risk of all-cause and CVD-related mortality over time as compared with those with CVD who engage in limited physical activity.58

An expert panel for the ACSM and American Heart Association reviewed the scientific literature and concluded that most adults with CVD can safely perform physical activity and exercise59; restrictions to intensity and duration of exercise may be necessary according to the type and severity of disease, and the American Heart Association recommends that adults with CVD consult with their physician before initiating an exercise program with an intensity level greater than walking.59 Specific effects of physical activity on heart disease and stroke are provided below because recommendations, barriers, and benefits vary between the two.

Heart Disease

Heart disease is the leading cause of death for adults older than 65 years.60 The CDC reports that as many as 200 000 deaths from heart disease are preventable each year, 56% of which occur in adults >65 years old.33 Physical exercise has been shown to have beneficial effects, reducing cholesterol and blood pressure, which are mediators of disease progression. High-intensity aerobic exercise is effective in increasing HDL levels, whereas evidence has shown that resistance training has beneficial impacts on LDL levels.61 In adults with hypertension, initiation of an aerobic exercise program results in an average sustained decrease in systolic blood pressure of 6.9 mm Hg.62 The same meta-analysis found that strength training reduced systolic blood pressure an average of 3.1 mm Hg in adults with hypertension.62 Several observational and randomized controlled trials have established that regular engagement in physical exercise is effective secondary prevention for coronary heart disease.63,64 Higher levels of physical activity offer greater prevention against cardiovascular events, yet as little as a 45- to 70-minute weekly increase in physical activity can result in reduced risk of cardiovascular events.65

For older adults with angina pectoris, cardiac surgeries, or acute CVD events, specialized intervention in the form of cardiac rehabilitation programs may be warranted. Cardiac rehabilitation programs have been greatly successful in reducing risk factors for mortality.66 Unfortunately, cardiac rehabilitation is a generally underutilized service for adults older than 65 years, particularly for those older than 75 years.67 Reasons for underuse include decreased physician referrals for this population68 because of an assumption that older adults have less benefit from such programs. However, when analyzing the impact from cardiac rehabilitation, adults older than 65 years demonstrate similar improvements from baseline in terms of blood pressure, cholesterol, weight management, and physical activity when compared with adults younger than 65 years.69

Stroke

Approximately 795 000 people in the United States suffer a stroke annually; 185 000 (23.4%) of these strokes are recurrent strokes.70 Physical activity can reduce known risk factors for stroke, including high cholesterol, hypertension, heart disease, and diabetes.71 The role of physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation, a risk factor for stroke, remains controversial. Vigorous-intensity and high-endurance exercise has been reported to increase risk of atrial fibrillation particularly in athletes; however, 2 recent meta-analyses have failed to show an increased risk of atrial fibrillation for high intensity or high duration physical activity in the general population.72,73 Moreover, regular engagement in low to moderate physical activity in the older adult appears to be associated with reduced risk of incident atrial fibrillation.74,75 Physical activity is associated with reduced risk of incident stroke and reduced risk of mortality from stroke and is also protective of recurrent stroke in stroke survivors.76,77

Physical impairments resulting from stroke, including hemiplegia, spasticity, and poor motor control, may reduce mobility, therefore limiting a person’s ability to engage in regular physical activity independently. Prevalence of physical inactivity is high following stroke, with <18% of stroke survivors achieving the recommended guidelines of 150 minutes of physical activity weekly.78 Although severity of the stroke is highly correlated with physical activity after the event, other factors, including intrinsic motivation, mood, and depression, and other medical comorbidities can greatly influence physical activity participation.79 For stroke survivors who demonstrate decreased physical activity tolerance, splitting daily exercise into multiple, short, moderate-intensity sessions may be better tolerated than a longer 20- to 30-minute session.79 Treadmill walking has some specific advantages for this population because it serves dually as a method to improve task-specific training of ambulation at the same time as providing aerobic conditioning.79,80 Additionally, for those with slower gait speeds, inclined treadmill walking can provide additional intensity of exercise while still allowing safe ambulation.79

Strength training, once contraindicated because of the false assumption that it increased spasticity, is now advocated for stroke survivors for its benefits in reducing cardiac demands and increasing functional independence.81 Hemiparetic knee extension strength is a strong predictor of walking capabilities in adults with stroke, and multiple studies have shown that progressive resistance training produces improvements not only in muscle strength but also in gait and balance in ambulatory stroke survivors.81-83 Specific evidence-based guidelines regarding intensity of strengthening have yet to be established, but the American Heart Association with the American Stroke Association issued a suggestion to perform higher-repetition, lower-load strengthening exercises as a prudent exercise prescription.79

Physical exercise prescription for older adults with stroke can be complicated by impairments caused by the cerebrovascular lesions. Limited independence with mobility, aphasia, and/or cognitive impairments can restrict participation in previously performed physical activity and complicate participation in community-based fitness activities. After discharge from formal rehabilitation programs, many stroke survivors with newfound disabilities report that limited knowledge of how or where to engage in physical exercise is a primary barrier to engaging in regular physical activity.79 Adherence to regular physical activity can be improved with tailored exercise guidance from health care professionals, linkage with adaptive exercise groups, and a strong family or social support system.

Diabetes

In 2012, the prevalence of diabetes among adults >65 years old was 25.9%, according to data from the 2009-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.84 Poor diet, sedentary behavior, and limited physical activity are contributing to the growing epidemic of diabetes in the United States. Higher sedentary time is associated with risk factors for diabetes, including larger waist circumference, higher insulin levels, higher triglyceride levels, and lower HDL levels.85,86 According to a recent meta-analysis of 16 prospective and 2 cross-sectional studies, adults with the highest levels of sedentary behavior have a 112% higher risk of diabetes than active older adults.57 Additionally, a prospective, longitudinal study of older adult women demonstrated that every 2 hours of sitting at work per day was associated with a 7% increased risk of diabetes, and every 2 hours of TV watching per day was associated with a 14% increased risk of diabetes; conversely, every hour of brisk walking per day was associated with a 34% reduced likelihood of developing the disease.56

Increasing physical activity among older adults with diabetes can improve insulin action, control glucose and lipid levels, and reduce hypertension. Consistent physical activity can reduce risk of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality among older adults with diabetes.87 Additionally, quality-of-life measures can be improved with participation in consistent physical activity.87

The American Diabetes Association and ACSM released a joint position statement recommending that adults with diabetes follow the general recommendations for exercise in adults, including >150 weekly minutes of aerobic conditioning and two to three days per week of resistance training.87 Special considerations may be needed for older adults with diabetes, depending on common comorbidities. For those with peripheral neuropathy affecting sensation, proper footwear during exercise and regular foot care is recommended to prevent the development of foot ulcers.87 For those with vision problems, additional focus on balance training can help reduce impairment from progressive vision decline. Heavy resistance training that might increase intraocular pressure is cautioned in adults with uncontrolled retinopathy. Older adults with diabetes and chronic kidney disease should be encouraged to maintain a regular physical activity schedule between dialysis treatments, although fatigue may be a limiting factor for dialysis patients.

Unfortunately, most adults with diabetes fail to meet physical activity recommendations. Adherence with regular physical activity in this population falls below national norms for adults, with <40% of adults with diabetes reporting an equivalent of 90 minutes of physical activity per week.88 Self-efficacy and strong social support are positively associated with initiation and maintenance of physical activity in older adults with diabetes, and interventions fostering the development of self-efficacy with exercise or strengthening support systems may improve adherence in this population.87

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

In 2011, COPD prevalence was highest among women 65 to 74 years old (10.4%) and 75 to 84 years old (9.7%) and among men aged 75 to 84 years old (11.2%).89 Avoidance of physical activity becomes a common behavioral response to dyspnea associated with exercise for persons with COPD. Inactivity contributes to worsening of respiratory function as well as reduced quality of life in persons with COPD.90 Physical activity is well documented to reduce COPD-related hospital readmissions and risk of mortality.91,92

Adults diagnosed with early stages of COPD should be encouraged to participate in light to moderate physical activity every day for 20 to 30 minutes.93 Pharmacological interventions to assist with respiration during exertion may be necessary for an individual to perform increased intensity or duration of physical activity before onset of dyspnea. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs focused at increasing exercise tolerance have been shown to increase functional status and exercise tolerance, and improve quality of life.94 Comprehensive pulmonary rehabilitation programs have led to significant improvement in active coping strategies, reduced activity avoidance behaviors, and contributed to decreased levels of anxiety and depression.95,96

Cancer

Older adults with cancer often face unique challenges with regard to remaining physically active. Fatigue, a common side effect from cancer treatments, often interferes with ability to perform even basic daily activities. Unfortunately, fatigue can persist for extended periods of time, even after treatment has ended. Historically, patients with cancer were instructed to rest and avoid strenuous activity in order to allow their bodies to recuperate and heal. New research indicates that exercise and physical activity are actually beneficial for this population and should be encouraged, within the individual’s capability.97

The bulk of research in cancer and physical activity pertains to studies of patients with breast cancer or prostate cancer. Yet experts with the ACSM reviewed the current body of scientific evidence and asserted that, although there are specific individual risks that should be accounted for, exercise during treatment and after survivorship from cancer is safe and should be encouraged.97 Benefits from physical activity among cancer survivors include improved strength and cardiovascular fitness,97 reduced fatigue,98,99 and improved quality of life.100

Additionally, physical activity may affect survivorship from cancer. Increased physical activity after breast cancer diagnosis appears to have a protective effect in regard to breast cancer mortality and all-cause mortality.101 In fact, physical activity after breast cancer diagnosis has been shown to have a stronger protective effect for mortality as compared with physical activity levels before diagnosis.102 A similar association between colon cancer survival and physical activity after diagnosis has been found.103

The exact duration and intensity of physical activity necessary to provide benefits for adults with cancer is unknown, and the capacity to perform physical activity is likely dependent on a variety of factors, including diagnosis and severity of disease, type of cancer treatment, and the individual’s response to treatment. The general recommendation to avoid inactivity for adults with cancer can be used. Specific medical screening and guidance from physicians may be required for some individuals with cancer who are at higher risk of fractures or cardiac disease.97

Depression

Depression is an often-overlooked problem that greatly affects health and quality of life of the older adult. A growing body of literature supports the recommendation for physical activity and exercise for persons with depression as either an adjunct to traditional psychotherapy or pharmacological treatments, or even as an alternative to such treatments.104 Physical activity is potentially advantageous over pharmacological treatment in the older adult because of the complications of increased side effects and drug interactions in this population. However, limited research specifically targets depression and physical activity in the older adult. In the few randomized controlled studies that have targeted this older adult population with depression, regular engagement in an exercise program has been shown to reduce the symptoms of depression. A 10-week physical exercise intervention class consisting of aerobic activity, strength training, and stretching provided as an adjunct to antidepressant therapy resulted in significantly reduced depressive symptoms when compared with controls who maintained pharmacological therapy only.105 In a small study of 32 community-dwelling older adults with depressive symptoms who were not receiving pharmacological therapy, those who were randomized to a 10-week resistance training exercise intervention had higher rates of depression resolution and maintained lower levels of depression symptoms at a 26-week follow-up as compared with those randomized to the health education group.106 A walking intervention program, consisting of 3 days per week of 40 minutes moderate-intensity walking, provided a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in previously inactive postmenopausal women.107 The studies available regarding physical activity and depression in the older adult are generally limited by small sample sizes, and the physical activity interventions are heterogeneous between studies. Although the findings from the few published studies on the topic suggest that physical activity has potential benefit in the reduction of depressive symptoms in older adults, additional research targeting the older adult population is needed. Research into intensity, dosage, and type of activity necessary for benefits remains limited for this population.

Cognitive Impairments, Dementia, and Alzheimer’s Disease

Changes in the structure of brain tissues occur in the normal aging process, with atrophy of the cortical tissues and loss of brain volume. Cognitive impairments such as memory problems, diminished executive function, and slower processing become more prevalent with age. Neurodegenerative changes outside of the normal aging process are seen in diagnoses such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other forms of dementia. The burden of disease of cognitive impairments in the United States is immense and continues to rise. According to data collected from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study, 13.9% of Americans older than 71 years are estimated to have dementia, including 9.7% with AD.108 The prevalence of dementia increases with age, with 37.4% of Americans >90 years old estimated to be affected by the disease.108 By 2030, the number of adults with AD in the United States is estimated to reach 8.4 million.109 Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a recognized risk factor for progression to AD, though many individuals with MCI revert or never progress to dementia with AD.110 The prevalence and incidence of MCI are difficult to determine because of lack of agreement on the definition and changing terminology; among Americans >65 years old, estimates of prevalence vary from 18.8% to 32.9% in the literature.111

As the prevalence of MCI, AD, and other forms of dementia increase in the US population, attention has been placed on the relationship between cognitive functioning and physical activity. Prospective cohort studies have found that healthy older adults who regularly participate in aerobic exercise demonstrate improved processing speeds, memory, and executive function when compared with peers who do not participate in aerobic exercise.112,113 Regular physical activity appears to protect against brain volume atrophy,114 cognitive impairment,115 and dementia.116 A prospective cohort of 299 healthy older adults revealed that walking the equivalent of 1 mile per day was associated with greater volume of gray matter in the hippocampal and prefrontal regions of the brain, as measured 9 years later by MRI.117 Follow-up 4 years after the MRI revealed that the increased gray matter volume was associated with significantly reduced likelihood of diagnosis of MCI or dementia.117 Additionally, the benefits of physical activity may not be limited to slowing brain volume decline; it may increase brain volume and improve cognition when introduced to healthy older adults. In a randomized controlled study with 120 healthy older adults, brisk walking at a frequency of 3 times per week for 1 year resulted in a 2% increase in hippocampal volume, compared with a 1.5% decrease in hippocampal volume in the control group; this increased hippocampal volume was significantly associated with improved performance with memory testing.118 The benefits of physical activity among healthy older adults provide promising evidence that initiation or maintenance of midlife to late-life physical activity can have residual impact on cognition later in life.

Whether physical activity can reduce the rate of cognitive decline or even improve cognition once impairments have developed has not yet been determined. Recent meta-analyses offer conflicting results regarding physical activity and cognitive function in older adults with MCI. Two meta-analyses failed to show benefit in memory, processing speed, or executive function from intervention studies of increased physical activity.119,120 However, in a meta-analysis of 29 randomized control studies, Smith et al121 concluded that older adults with MCI demonstrate improvements in cognitive function following exercise programs that combine strength training with aerobic exercise. The escalating burden of disease of dementia necessitates additional research into the effects of physical activity in slowing the progression of disease in MCI and in the prevention of incident dementia.

For older adults who have progressed from mild cognitive decline to a diagnosis of AD or other form of dementia, participation in regular physical activity may be difficult. Taking multiple medications, dizziness, decreased independence with activities of daily living, and a history of falls are associated with decreased activity levels in patients with dementia.122 Physical activity intervention programs have shown benefits for individuals with dementia, including improved independence with activities of daily living, reduced demands of the caregiver, and improved cognitive scores.123

At this time, evidence regarding type, duration, and intensity of physical activity necessary to invoke benefits for persons with cognitive decline is insufficient to determine specific recommendations. Intervention studies within this population vary in the type of exercise prescribed, but the limited research currently available points to the potential benefits of maintaining physical activity for persons with cognitive decline.

Barriers to Physical Activity

Knowing common barriers to physical activity reported by older adults is essential for developing tailored treatment recommendations. The barriers represent responses to questions similar to the following: “What keeps you from being more active?”124 As such, they embody the common factors that older adults perceive as preventing them from engaging in physical activity. As many as 87% of older adults report at least 1 barrier.125 The barriers reported most often are different for older adults compared with younger adults, yet the 2 groups have some barriers in common. Adults 20 to 60 years of age most often report poor body image, lack of confidence, being uncomfortable in gym environments, and not knowing other people who exercise as reasons for physical inactivity.126 Older adults most often report poor health as their primary barrier in addition to fear of falling or injury, symptoms of depression, lack of time, adverse built environments, and a general disinterest in being active.127,128

Gender differences in reported barriers have been noted among older adults. Compared with men, women more often report lack of opportunity, lack of facilities, and concerns about falling, safety, and injury.127,128 The barriers to physical activity for older adults differ across dimensions of weight status,129 depression,130 and physical mobility.131 Even in seemingly homogeneous populations, barriers can differ significantly among subgroups.132 Despite this variance, common barriers emerge across geographically and culturally dissimilar populations and are described below along with potential solutions.

Physical Health

The most common reason older adults give for not engaging in physical activity is poor physical health.133 Reduced mobility, pain, and other symptoms of medical problems can affect an older adult’s ability and/or motivation to engage in physical activity. In 2012, 35.9% of older adults reported a disability (ie, difficulty hearing, vision, cognition, ambulation, self-care, independent living), and 23.1% reported difficulty walking or climbing stairs.134 Physical disability can be both caused by and result in pain, which is experienced by 25% to 50% of community-dwelling older adults and by 45% to 80% of nursing home residents.135 Some types of pain reduce with old age (eg, head, abdominal, chest pain), whereas others increase (eg, joint pain).136 Fatigue or being too tired to exercise can be a by-product of chronic illnesses common in older adults (eg, cancer, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke, depression, sleep disorders).137 It is also a common symptom of depression.138 Treatments for persistent exhaustion include cognitive behavioral therapy and graded exercise therapy.139

When interviewed, older adults express awareness of the physical and mental health benefits of physical activity. Evidence suggests that older adults are aware of the health benefits of physical activity, so much so that improving health was the most commonly reported reason older adults gave for engaging in physical activity.133,140,141 Physicians can use this duality to their advantage by encouraging adults who report physical health as a barrier to physical activity by reminding them of its overall, and often disease-specific, health benefits. When fatigue or lack of energy is the major complaint, suggestions include scheduling physical activity in short bouts at times when the energy level is at its highest (such as early in the morning).

Fear of Falling and Fear of Injury

Older adults are at increased risk of falling and of injury because of physiological changes experienced throughout their lifetime. Between 30% and 60% of older adults fall each year.142 Falls are the leading cause of accidental death in this population143 and contribute to more than 80% of injury-related hospital admissions.144 Both fallers and nonfallers report the fear of falling as a barrier to physical activity, yet older adults with a previous fall are at higher risk for falling again.145 Exercise, with and without balance training, has been shown to reduce the risk of falling and should be encouraged.146,147

Fear of injury may stem from perceptions that older adults experience more severe outcomes from injury than their younger counterparts. Additionally, adults whose injury prevents them from being physically active can rapidly undergo physical deconditioning, and after only a few days of hospitalization, deconditioning can lead to decline in functional status.148 Although significant differences in sport-specific injury rates (ie, skiing, golfing, bowling, cycling, weight training) are apparent between older adults and adults of younger ages, evidence suggests that the incidence of injuries related to general physical activity in older adults (14%-56%, with most larger epidemiological studies reporting 16%) is similar to that of younger adults.149 To prevent injury, activities that have minimal risk (such as walking) and that are appropriate for the age, fitness level, skill level, and health status of the individual are recommended.

Social Support

Older adults often report that they do not have someone to exercise with. In 2013, 28% of community-dwelling older adults lived alone.150 For these adults and others living with persons incapable of exercise, physical activity presents an opportunity for recently separated or lonely older adults to engage with others during group activities, thereby reducing isolation and loneliness.151 Merely belonging to a group doubles the odds of being physically active.152 It is sometimes effective for older adults to participate and volunteer in community center activities, especially those that involve physical activity. Reaching out to friends and family to encourage participation in physical activities is sometimes useful. Joining a physically active group or club (such as a hiking or dancing group) can encourage making friends with similar activity interests.

Time

As aging progresses, routine activities take longer to complete, effectively shortening the amount of time available for other pursuits. Older adults are often called on to care for their children, grandchildren, and their parents. Additionally, they are committed to volunteer responsibilities and to committee/community activities.153 For cultures with strong collectivist attitudes, taking time away from community activities may be frowned on.154 For these individuals, involvement in physically active community activities can be strongly recommended. Physical activity can also be incorporated into daily routines such as exercising while watching TV and parking farther away from destination points.

Built Environment

Physical environment can be a barrier to engaging in physical activity for older adults. Distance from exercise facilities or open spaces conducive to physical activity is often reported as a barrier. Similarly, lack of transportation to such facilities or spaces is another barrier. Even for older adults with a driver’s license and automobile, it may be difficult to get around because they may feel unsafe driving. Although public transportation is an option in some cities, it is time-consuming, sometimes unreliable, and can be stressful.128 Other commonly cited reasons for physical inactivity related to the built environment include unsafe neighborhoods, streets with heavy traffic or poor pedestrian infrastructure, and unmaintained sidewalks. Strategies to deal with these barriers include using the “buddy system” to overcome safety concerns or identifying places in close proximity to home.

Cost

The income of most older adults comes from primarily fixed sources, with only 28% reporting earnings as a major source of income.155 For older adults whose funds have already been designated to specific living expenses, adding fees from health club or fitness club memberships may prove difficult. However, many low- or no-cost physical activity opportunities may be available (eg, volunteer as a coach or umpire, find fitness centers that offer discounts to senior citizens, be active at home). It is also important to note that contemporaneous financial costs of physical activity may be offset by lowering or reducing future health care expenditures.156-159

Climate

Commonly cited reasons for not engaging in physical activity include excessive heat, cold, or precipitation. Because these barriers have significant regional and daily variance, older adults are encouraged to check local sources for activities not subject to environmental barriers. Common indoor activities available in many localities include dancing and walking in malls.

Other Suggestions to Help Patients Overcome Barriers

Older adults have an affinity for solving their own problems and,140 before advice is given, should be asked what they can do to overcome barriers. The time required for standard motivational interviewing techniques may be too long to use in a health care environment,160 but brief questionnaires regarding the steps elderly adults can take to overcome barriers can provide physicians with information that can be used to develop tailored recommendations to increase older adults’ physical activity levels. Having patients focus on times they were active and exploring the circumstances in which they took place could help identify individualized motivators that have a history of success. These intrapersonal and interpersonal methods for overcoming barriers should be considered along with the broader ecological framework for increasing physical activity.161,162

Promoting Physical Activity in the Older Adult

As the body of evidence supporting the benefits of physical activity among older adults continues to grow, effectively promoting physical activity has become a focus of practitioners and public health professionals. Clinicians, researchers, and even many older adults are realizing the benefits of activity on health and quality of life. Lifestyle changes, even at an advanced age, can have significant health benefits. Yet changing habits that have been in place for years or even decades can prove difficult.

Sedentary older adults tend to have better adherence with lifestyle changes when the recommendations are explicitly prescribed by a health care professional and written down. Use of written exercise prescriptions have been shown to increase physical activity levels, at least for short intervals.163-165 However, neither verbal nor written recommendations from health care providers have consistently been associated with long-term compliance with physical activity recommendations. To help health care providers, there is a link on the Physical Activity Guidelines Web site focused on physical activity interventions that have been successful in clinical settings and may be a useful resource (http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/).

Lack of education about the health benefits of physical activity is not a common reason for sedentary behavior, and it is important to recognize and account for other potential obstacles to physical activity. Health care professionals should be cognizant of the social, psychological, and environmental barriers that may be restricting an individual’s compliance with physical activity participation to best assist in providing support for long-lasting change. Creating realistic plans for increased physical activity that are feasible and sustainable for each individual will provide the best opportunity for long-term adherence.

Often the best way to reduce sedentary behavior and increase physical activity is for older adults to plan activities around their lifestyle. Engaging in activities that provide satisfaction will allow adults to remain motivated and active. It is also important that the older adult feels safe and skilled in performing the activity because this may lead to long-term compliance with exercise. An important resource to understand behaviors and increase physical activity can be found in the Community Guide, a composite review of physical activity interventions conducted in specific settings (http://thecommunityguide.org/pa/index.html).

Some older adults may need additional personalized assistance to initiate a change in physical activity. For older adults with a functional impairment or disability, physical and/or occupational therapy may be indicated to improve mobility, reduce pain, and progress activities of daily living. After improved independence is achieved, progression to a home or community exercise program may be more successful. For those with moderate or severe cardiac disease, supervised exercise in a cardiac rehabilitation program may be beneficial until exercise is deemed safe. Adults with other health or mobility problems may gain benefit initially from a qualified physical trainer who has experience working with older adults with medical comorbidities. Support from qualified personnel can help ease the transition from sedentary to active lifestyles and increase a person’s perception of self-efficacy and success with physical activity.

The advent of new technologies allows for innovative methods to increase adherence with physical activity. Although most studies have focused on the contributions of technology and physical activity in younger populations, the limited research currently available shows that these new technologies may be effective tools for older adults as well. Web-based programs have been used as a way to introduce home-based exercise instruction in the older adult population.166,167 Long-term care facilities and assisted living communities have found success with Wii and other virtual reality games in providing motivation for physical activity for their residents.168

Pedometers have the potential to affect activity levels by providing immediate, reliable, and objective monitoring. Pedometers may be particularly beneficial for this population because walking is the most commonly reported physical activity performed by older adults. Pedometer use has been shown to effectively increase daily step counts by 22% to 27% in adults older than 65 years.169,170 Improvements in numbers of steps are further increased when individualized step count goals are established according to personal activity capacities.171 More advanced activity monitors, including the Fitbit, have also been used with success in this older adult population to provide self-monitoring and maintenance of physical activity.172 As in other areas of public health (eg, tobacco control), real-time processing is being added to these remote sensors to make possible ecological momentary interventions that adapt to each individual and their environment.173

There are tremendous health benefits that can accrue with even small increases in physical activity among older adults and especially among those with existing disease. These health benefits include reducing functional limitations and subsequent disability, thus improving quality of life. Encouraging increases in aerobic activity in addition to muscle strengthening activities and reducing sedentary time are established approaches to improving the health of older adults. For older adults not meeting physical activity guidelines, it is never too late to start.

References

- 1. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402-407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7823386. Accessed August 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. United States. Department of Health, & Human Services. (1996). Physical activity and health: a report of the Surgeon General. DIANE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. Hyattsville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chomistek AK, Manson JE, Stefanick ML, et al. Relationship of sedentary behavior and physical activity to incident cardiovascular disease: results from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:2346-2354. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Seguin R, Buchner DM, Liu J, et al. Sedentary behavior and mortality in older women: the women’s health initiative. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46:122-135. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Rezende LFM, Rey-López JP, Matsudo VKR, do Carmo Luiz O. Sedentary behavior and health outcomes among older adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:333. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pavey TG, Peeters GG, Brown WJ. Sitting-time and 9-year all-cause mortality in older women. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:95-99. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23243009. Accessed August 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. León-Muñoz LM, Martínez-Gómez D, Balboa-Castillo T, López-García E, Guallar-Castillón P, Rodríguez-Artalejo F. Continued sedentariness, change in sitting time, and mortality in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:1501-1507. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23439420. Accessed August 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2013: With Special Feature on Prescription Drugs. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hung WW, Ross JS, Boockvar KS, Siu AL. Recent trends in chronic disease, impairment and disability among older adults in the United States. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ward BW, Schiller JS. Prevalence of multiple chronic conditions among US adults: estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2010. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stewart AL, Hays RD, Wells KB, Rogers WH, Spritzer KL, Greenfield S. Long-term functioning and well-being outcomes associated with physical activity and exercise in patients with chronic conditions in the Medical Outcomes Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47:719-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thompson PD, Buchner D, Pina IL, et al. Exercise and physical activity in the prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology (Subcommittee on Exercise, Rehabilitation, and Prevention) and the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism (Subcommittee on Physical Activity). Circulation. 2003;107:3109-3116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B, et al. Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:e147-e167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang W, Moskowitz RW, Nuki G, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:137-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Deshpande N, Metter JE, Guralnik J, Bandinelli S, Ferrucci L. Sensorimotor and psychosocial determinants of 3-year incident mobility disability in middle-aged and older adults. Age Ageing. 2014;43:64-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Theis KA, Furner SE. Shut-in? Impact of chronic conditions on community participation restriction among older adults. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:759158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Viljanen A, Kaprio J, Pyykkö I, Sorri M, Koskenvuo M, Rantanen T. Hearing acuity as a predictor of walking difficulties in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2282-2286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dommes A, Cavallo V. The role of perceptual, cognitive, and motor abilities in street-crossing decisions of young and older pedestrians. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31:292-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin C-H, Ou Y-K, Wu R-M, Liu Y-C. Predictors of road crossing safety in pedestrians with Parkinson’s disease. Accid Anal Prev. 2013;51:202-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fairhall N, Sherrington C, Cameron ID, et al. Predicting participation restriction in community-dwelling older men: the Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project. Age Ageing. 2014;43:31-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Werner S, Auslander GK, Shoval N, Gitlitz T, Landau R, Heinik J. Caregiving burden and out-of-home mobility of cognitively impaired care-recipients based on GPS tracking. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1836-1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hermsen LA, Leone SS, Smalbrugge M, Dekker J, van der Horst HE. Frequency, severity and determinants of functional limitations in older adults with joint pain and comorbidity: results of a cross-sectional study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59:98-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Milos V, Bondesson Å, Magnusson M, Jakobsson U, Westerlund T, Midlöv P. Fall risk-increasing drugs and falls: a cross-sectional study among elderly patients in primary care. BMC Geriatr. 2014;14:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnell K, Fastbom J. Multi-dose drug dispensing and inappropriate drug use: a nationwide register-based study of over 700,000 elderly. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2008;26:86-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pfortmueller C, Lindner G, Exadaktylos A. Reducing fall risk in the elderly: risk factors and fall prevention, a systematic review. Minerva Med. 2014;105:275-281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tiedemann A, Sherrington C, Lord SR. Predictors of exercise adherence in older people living in retirement villages. Prev Med. 2011;52:480-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carroll D, Courtney-Long E, Stevens A, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity—United States, 2009-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:407-413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prohaska TR, Anderson LA, Hooker SP, Hughes SL, Belza B. Mobility and aging: transference to transportation. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:392751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rosenberg DE, Bombardier CH, Hoffman JM, Belza B. Physical activity among persons aging with mobility disabilities: shaping a research agenda. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:708510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Satariano WA, Guralnik JM, Jackson RJ, Marottoli RA, Phelan EA, Prohaska TR. Mobility and aging: new directions for public health action. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:1508-1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schieb LJ, Greer SA, Ritchey MD, George MG, Casper ML. Vital signs: avoidable deaths from heart disease, stroke, and hypertensive disease-United States, 2001-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:721-727. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24005227. Accessed September 2, 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hügle T, Geurts J, Nüesch C, Müller-Gerbl M, Valderrabano V. Aging and osteoarthritis: an inevitable encounter? J Aging Res. 2012;2012:950192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wallis JA, Webster KE, Levinger P, Taylor NF. What proportion of people with hip and knee osteoarthritis meet physical activity guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21:1648-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pisters MF, Veenhof C, van Meeteren NLU, et al. Long-term effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1245-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. White DK, Tudor-Locke C, Zhang Y, et al. Daily walking and the risk of incident functional limitation in knee osteoarthritis: an observational study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2014;66:1328-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dunlop DD, Song J, Semanik PA, et al. Relation of physical activity time to incident disability in community dwelling adults with or at risk of knee arthritis : prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2014;348:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Valderrabano V, Steiger C. Treatment and prevention of osteoarthritis through exercise and sports. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:374653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tanaka R, Ozawa J, Kito N, Moriyama H. Efficacy of strengthening or aerobic exercise on pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2013;27:1059-1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wang T-J, Lee S-C, Liang S-Y, Tung H-H, Wu S-F V, Lin Y-P. Comparing the efficacy of aquatic exercises and land-based exercises for patients with knee osteoarthritis. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:2609-2622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Looker AC, Melton LJ, Harris TB, Borrud LG, Shepherd JA. Prevalence and trends in low femur bone density among older US adults: NHANES 2005-2006 compared with NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:64-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chastin SFM, Mandrichenko O, Helbostadt JL, Skelton DA. Associations between objectively-measured sedentary behaviour and physical activity with bone mineral density in adults and older adults, the NHANES study. Bone. 2014;64:254-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Daly RM, Ahlborg HG, Ringsberg K, Gardsell P, Sernbo I, Karlsson MK. Association between changes in habitual physical activity and changes in bone density, muscle strength, and functional performance in elderly men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:2252-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wee J, Sng BYJ, Shen L, Lim CT, Singh G, Das De S. The relationship between body mass index and physical activity levels in relation to bone mineral density in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Arch Osteoporos. 2013;8:162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gómez-Cabello A, Ara I. Effects of training on bone mass in older adults. Sport Med. 2012;42:301-325. http://link.springer.com/article/10.2165/11597670-000000000-00000. Accessed July 16, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Nikander R, Sievänen H, Heinonen A, Daly RM, Uusi-Rasi K, Kannus P. Targeted exercise against osteoporosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis for optimising bone strength throughout life. BMC Med. 2010;8:47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Howe T, Shea B, Lj D, et al. Exercise for preventing and treating osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. 2011;(7):CD000333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ma D, Wu L, He Z. Effects of walking on the preservation of bone mineral density in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2013;20:1216-1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bolam KA, van Uffelen JGZ, Taaffe DR. The effect of physical exercise on bone density in middle-aged and older men: a systematic review. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2749-2762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chan BKS, Marshall LM, Winters KM, Faulkner KA, Schwartz A V, Orwoll ES. Incident fall risk and physical activity and physical performance among older men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:696-703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Madureira MM, Bonfá E, Takayama L, Pereira RMR. A 12-month randomized controlled trial of balance training in elderly women with osteoporosis: improvement of quality of life. Maturitas. 2010;66:206-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Smulders E, Weerdesteyn V, Groen BE, et al. Efficacy of a short multidisciplinary falls prevention program for elderly persons with osteoporosis and a fall history: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:1705-1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD007146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Naional Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. NHLBI Fact Book: Fiscal Year 2012. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/about/documents/factbook/2012/index.htm. Accessed January 9, 2014.

- 56. Grøntved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305:2448-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, et al. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2895-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mons U, Hahmann H, Brenner H. Reverse J-shaped association of leisure time physical activity with prognosis in patients with stable coronary heart disease: evidence from a large cohort with repeated. Heart. 2014;100:1043-1049. http://heart.bmj.com/content/early/2014/03/18/heartjnl-2013-305242.short. Accessed August 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fletcher GF, Ades PA, Kligfield P, et al. Exercise standards for testing and training: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;128:873-934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Heron M. Death: leading causes for 2010. In: National Vital Statistics Reports.Vol 62, no 6 Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2013; 1-96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tambalis K, Panagiotakos DB, Kavouras SA, Sidossis LS. Responses of blood lipids to aerobic, resistance, and combined aerobic with resistance exercise training: a systematic review of current evidence. Angiology. 2009;60:614-632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Cornelissen VA, Smart NA. Exercise training for blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lavie CJ, Thomas RJ, Squires RW, Allison TG, Milani RV. Exercise training and cardiac rehabilitation in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:373-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Swift DL, Lavie CJ, Johannsen NM, et al. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and exercise training in primary and secondary coronary prevention. Circ J. 2013;77:281-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:716-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Taylor AH, Cable NT, Faulkner G, Hillsdon M, Narici M, Van Der Bij AK. Physical activity and older adults: a review of health benefits and the effectiveness of interventions. J Sports Sci. 2004;22:703-725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Davies P, Taylor F, Beswick A, et al. Promoting patient uptake and adherence in cardiac rehabilitation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD007131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Brown T, Hernandez A, Bittner V, Cannon C, Ellrodt G, Liang L. Predictors of cardiac rehabilitation referral in coronary artery disease patients: findings from the American Heart Association’s Get With The Guidelines Program. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:515-521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Maniar S, Sanderson BK, Bittner V. Comparison of baseline characteristics and outcomes in younger and older patients completing cardiac rehabilitation. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2009;29:220-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2014 update. A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;129:399-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA. 1995;273:402-407. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7823386. Accessed August 28, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kwok CS, Anderson SG, Myint PK, Mamas MA, Loke YK. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177:467-476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ofman P, Khawaja O, Rahilly-Tierney CR, et al. Regular physical activity and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:252-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Azarbal F, Stefanick ML, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, et al. Obesity, physical activity, and their interaction in incident atrial fibrillation in postmenopausal women. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Mozaffarian D, Furberg CD, Psaty BM, Siscovick D. Physical activity and incidence of atrial fibrillation in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Circulation. 2008;118:800-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Gordon NF, Gulanick M, Costa F, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Subcommittee on Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention; the Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the Stroke Council. Circulation. 2004;109:2031-2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lee CD, Folsom AR, Blair SN. Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2003;34:2475-2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Butler EN, Evenson KR. Prevalence of physical activity and sedentary behavior among stroke survivors in the United States. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2014;21:246-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Billinger SA, Arena R, Bernhardt J, et al. Physical activity and exercise recommendations for stroke survivors: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2532-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Macko RF, Ivey FM, Forrester LW, et al. Treadmill exercise rehabilitation improves ambulatory function and cardiovascular fitness in patients with chronic stroke: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. 2005;36:2206-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Pak S, Patten C. Strengthening to promote functional recovery poststroke: an evidence-based review. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2008;15:177-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Hill TR, Gjellesvik TI, Moen PMR, et al. Maximal strength training enhances strength and functional performance in chronic stroke survivors. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:393-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ada L, Dorsch S, Canning CG. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52:241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pubs/statsreport14/national-diabetes-report-web.pdf. Accessed January 30, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Healy GN, Matthews CE, Dunstan DW, Winkler EAH, Owen N. Sedentary time and cardio-metabolic biomarkers in US adults: NHANES 2003-06. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:590-597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Cooper a R, Sebire S, Montgomery AA, et al. Sedentary time, breaks in sedentary time and metabolic variables in people with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2012;55:589-599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]