Abstract

In the United States, high rates of obesity and chronic disease impose serious consequences on the population’s health and health care system. Primary care providers are critical to broad prevention efforts aiming to reduce the burden of chronic disease in the nation and play an important role in addressing lifestyle behaviors that can result in illness and premature death. Unhealthy dietary behaviors largely contribute to morbidity and mortality in the United States despite national efforts to improve the nutritional quality of the typical American diet. This article discusses a comprehensive set of national evidence-based recommendations known as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans that can support primary care providers’ efforts to improve patient outcomes through optimal nutrition and healthy lifestyle behaviors. This article also describes basic behavioral counseling techniques primary care providers can incorporate into time-limited patient encounters to help improve the dietary and physical activity behaviors of their patients.

Keywords: dietary guidelines, primary care, dietary counseling, preventive medicine, obesity

‘Today, primary care providers (PCPs) are critical to broad prevention efforts to reduce the burden of chronic disease in the United States.’

As the foundation of the nation’s health care delivery system, primary care serves as a first point of contact for most individuals seeking treatment or guidance on health-related issues.1 Today, primary care providers (PCPs) are critical to broad prevention efforts to reduce the burden of chronic disease in the United States, where high rates of obesity and lifestyle-related chronic disease impose serious consequences on the population’s health and health care system.

In the United States, approximately 68% of adults and 34% of children and adolescents are considered overweight or obese,2 with an estimated 7 in 10 premature deaths each year resulting from chronic diseases.3 Both the US economy and the health care system struggle to withstand the impact of current levels of medical spending, which represent the highest of any nation in the world4 and yield far poorer health outcomes than most other industrialized countries.5

Unhealthy dietary behaviors largely contribute to overweight and obesity and are associated with major causes of poor health outcomes and premature death even in the absence of excess body weight.6 The incidence of many diet-related chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease as well as their associated morbidity and mortality, can be minimized and even prevented with timely, effective dietary and lifestyle intervention strategies.7

Promoting healthful, science-based dietary behaviors is an important prevention strategy for all sectors of society. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (Dietary Guidelines or the Guidelines) provides a comprehensive set of evidence-based recommendations for healthy eating and physical activity patterns Americans can adopt to help reduce their risk for many chronic illnesses.8 The Dietary Guidelines communicate nutrition information and dietary guidance that supports health care professionals and clinicians addressing dietary behaviors in a variety of settings, including primary care.

Today primary care and public health professionals face many challenges in helping Americans achieve their highest standard of health. This shared responsibility necessitates collaboration within and across fields as well as a willingness to alter long-held practices and roles regarding disease prevention and health promotion. Addressing unhealthy lifestyle behaviors such as poor diet and physical inactivity falls within the scope of both public health and clinical practice; however, PCPs are now challenged to tackle these complex issues more frequently in the primary care setting.1

As the US health care system evolves, PCPs will have new and expanded opportunities to address diet-related and lifestyle-related behaviors in clinical practice. The purpose of this article is to discuss applications of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans in primary care and describe basic behavioral counseling techniques PCPs can incorporate into time-limited patient encounters to help improve the dietary and physical activity behaviors of their patients.

Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Background

The Dietary Guidelines is a national health promotion and chronic disease prevention initiative that provides food-based guidance and nutrition information for Americans ages 2 years and older.8 As the foundational nutrition policy for all federal food and nutrition programs, this set of evidence-based recommendations is intended to help policymakers, nutrition professionals, and health care providers guide the food choices and physical activity behaviors of healthy individuals as well as those at increased risk for developing chronic diseases.

Along with the key recommendations of the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, the Dietary Guidelines helps focus national, state, and local prevention efforts on diet and physical activity, both of which are critical to improving individual and population health. Eating patterns and physical activity behaviors based on the Dietary Guidelines can lead to a healthy body weight and should be flexible, individualized, and achieved over time.

The federal government published the first edition of the Guidelines in 1980 and has released a new edition every five years since. Prior to 1990, the Dietary Guidelines was released on a voluntary basis (ie, 1980, 1985, 1990); however, following the passage of the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990 (P.L. 101-445), Congress required the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) jointly publish the Dietary Guidelines at least every five years.9

Each 5-year cycle, the HHS and USDA Secretaries appoint a group of independent scientific experts to the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, a Federal Advisory Committee that advises the Secretaries on the development of the Dietary Guidelines recommendations. Committee members serve voluntarily for 2 years and thoroughly review current scientific evidence on the relationships between diet, nutrition, physical activity, and health to inform their recommendations to the government on national dietary guidance. The Committee synthesizes current knowledge and describes their evidence-based recommendations in a comprehensive report submitted to the HHS and USDA Secretaries at the conclusion of their work.

The Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee provides the scientific basis for the government’s Dietary Guidelines recommendations, which are ultimately determined by the two Departments. The Guidelines are presented as actionable food-based recommendations and nutrition information for the general population and various large subpopulations, such as pregnant women and older adults. HHS and USDA describe the Dietary Guidelines in a policy document intended for health professionals and policymakers who then translate the key recommendations into practice through food and nutrition programs, education, and intervention strategies.

Since the first edition of the Dietary Guidelines, scientific and medical knowledge related to diet, physical activity, and health has grown tremendously. As this body of literature has expanded, researchers and scientists have developed and refined systematic approaches for synthesizing large volumes of evidence to facilitate translation into practice. The 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee was the first to use a systematic approach for reviewing and synthesizing the scientific evidence and developing its conclusions. To facilitate this laborious process, the USDA created the Nutrition Evidence Library (NEL), a Web-based electronic system that supports rigorous systematic reviews to inform federal food and nutrition policy and programs.10 The NEL improves efficiency and reduces the risk of biases during the systematic literature review process, and increases transparency with the public by providing the Committees’ methodologies and conclusions on the NEL Web site (the USDA’s Nutrition Evidence Library is publically available at http://www.nel.gov/).

Impact on Federal Food and Nutrition Initiatives

Federal programs have far-reaching effects on individuals, families, and communities across the country. As the primary basis for the federal government’s food and nutrition initiatives, the Dietary Guidelines inform a range of activities in agencies and offices across HHS, USDA, and other Departments. These recommendations support the government in providing consistent, science-based resources to the public and affect policies, educational programs, food purchasing, grant opportunities, research, and data collection nationwide.

For example, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010 was passed to help ensure children and other at-risk Americans have greater access to healthy foods and meals.11,12 This law authorizes funding and sets policy for several USDA national food assistance programs and helps to better align critical initiatives with current Dietary Guidelines. Because of this law, the government can better address some of the nation’s nutritional needs through the National School Lunch Program, School Breakfast Program, and Summer Food Service Program; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC); and the Child and Adult Care Food Program.12

National Disease Prevention and Health Promotion Initiatives for Primary Care

Affordable Care Act

In 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Affordable Care Act or ACA) was signed into law to help improve the nation’s health care delivery system and the nation’s health. At that time, national health care spending accounted for approximately 18% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), and has grown at a rate five times faster than the GDP since 1960.5 The ACA provisions aim to control health care expenditures, expand access to affordable health coverage for Americans, and improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the US health care system.1,13

When fully implemented, the ACA will have a considerable impact on the delivery of primary care and the role of PCPs in addressing the underlying causes of obesity and lifestyle-related chronic diseases. The ACA removes substantial cost and coverage barriers that prevent many Americans from accessing preventive care and will increase the delivery of these services in primary care. In 2011, an estimated 54 million Americans received expanded coverage of clinical preventive services as a result of the ACA.14

Optimal delivery and utilization of clinical preventive services, such as screening, counseling, and use of preventive medications, can improve health and longevity of individuals and populations.15,16 Under the ACA, qualifying individuals can now receive many of these services with no out-of-pocket costs, including preventive care for infants, children, adolescents; preventive care and screenings for women; recommended immunizations; and certain clinical preventive services recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF or the Task Force).13 Table 1 summarizes select Task Force recommendations relevant to the Dietary Guidelines and covered by the ACA.17-20

Table 1.

| Population | Recommendation | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Screening for and management of obesity in adults | ||

| Adults 18 years and older | Screen for obesity. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or higher should be offered or referred to intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions. (Grade B) | Intensive, multicomponent behavioral interventions for obese adults include the following components:

|

| Screening for obesity in children and adolescents | ||

| Children 6 years and older | Screen children ages 6 years and older for obesity. Offer or refer for intensive counseling and behavioral interventions. (Grade B) | Refer patients to comprehensive moderate- to high-intensity programs that include dietary, physical activity, and behavioral counseling components. |

| Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults | ||

| General adult population without a known diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease | Although the correlation among healthful diet, physical activity, and the incidence of cardiovascular disease is strong, existing evidence indicates that the health benefit of initiating behavioral counseling in the primary care setting to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. Clinicians may choose to selectively counsel patients rather than incorporate counseling into the care of all adults in the general population. (Grade C) | Medium- or high-intensity behavioral interventions to promote a healthful diet and physical activity may be provided to individual patients in primary care settings or in other sectors of the health care system after referral from a primary care clinician. In addition, clinicians may offer healthful diet and physical activity interventions by referring the patient to community-based organizations. Strong linkages between the primary care setting and community-based resources may improve the delivery of these services. |

| Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote a healthy diet in adults | ||

| Adults with increased risk for diet-related chronic disease | The USPSTF recommends intensive behavioral dietary counseling for adult patients with hyperlipidemia and other known risk factors for cardiovascular and diet-related chronic disease. Intensive counseling can be delivered by primary care clinicians or by referral to other specialists, such as nutritionists or dietitians. (Grade Ba) | Medium- to high-intensity counseling interventions can produce medium-to-large changes in average daily intake of core components of a healthy diet (including saturated fat, fiber, fruit, and vegetables) among adult patients at increased risk for diet-related chronic disease. Intensive counseling interventions that have been examined in controlled trials among at-risk adult patients have combined nutrition education with behavioral dietary counseling provided by a nutritionist, dietitian, or specially trained primary care clinician (eg, physician, nurse, or nurse practitioner). |

| Description of recommendation grades | ||

| A—Strongly Recommended: The USPSTF strongly recommends that clinicians provide [the service] to eligible patients. The USPSTF found good evidence that [the service] improves important health outcomes and concludes that benefits substantially outweigh harms. | ||

| B—Recommended: The USPSTF recommends that clinicians provide [the service] to eligible patients. The USPSTF found at least fair evidence that [the service] improves important health outcomes and concludes that benefits outweigh harms. | ||

| C—No Recommendation: The USPSTF makes no recommendation for or against routine provision of [the service]. The USPSTF found at least fair evidence that [the service] can improve health outcomes but concludes that the balance of benefits and harms is too close to justify a general recommendation. | ||

| D—Not Recommended: The USPSTF recommends against routinely providing [the service] to asymptomatic patients. The USPSTF found at least fair evidence that [the service] is ineffective or that harms outweigh benefits. | ||

| I—Insufficient Evidence to Make a Recommendation: The USPSTF concludes that the evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routinely providing [the service]. Evidence that the [service] is effective is lacking, of poor quality, or conflicting and the balance of benefits and harms cannot be determined. | ||

Abbreviation: USPSTF, US Preventive Services Task Force.

Update in progress.

National Prevention Strategy

The ACA also established a National Prevention Council led by the US Surgeon General to develop and coordinate a National Prevention Strategy and Action Plan to help guide the implementation of effective and achievable prevention efforts in the United States. The National Prevention Strategy was released in 2011 and provides strategic directions and targeted priorities for improving Americans’ health through chronic disease prevention.21 Their healthy eating recommendations, in particular, rely on implementation of Dietary Guidelines recommendations as the cornerstone for federal nutrition programs and education initiatives.

The National Prevention Strategy also details specific action items for health care providers.21 According to the Strategy, clinicians should:

Assess dietary patterns (both quality and quantity of food consumed), provide nutrition education and counseling, and refer people to community resources (eg, WIC, Head Start, County Extension Services, and nutrition programs for older Americans);

Screen for obesity by measuring body mass index and deliver appropriate care according to clinical practice guidelines for obesity; and

Use maternity care practices that empower new mothers to breastfeed, such as the Baby-Friendly Hospital standards.

US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations

Since 1984, the USPSTF has established and maintained evidence-based recommendations on clinical preventive services for their application in the primary care setting.16 The Task Force is an independent panel of experts in preventive medicine and primary care and has recommendations on over 100 clinical preventive services. Each Task Force recommendation is assigned a letter grade (A, B, C, D, or I) based on the magnitude of net benefit and the strength of evidence regarding the clinical service.16 Table 1 provides descriptions of the Task Force’s evidence grades.

At this time, the Task Force recommends providers screen patients ages 6 years and older for obesity and offer or refer those with obesity to intensive counseling and behavioral interventions (grade B). The Task Force also recommends intensive behavioral dietary counseling for adults with hyperlipidemia and other known risk factors for cardiovascular and diet-related chronic disease (grade B); this recommendation is currently under revision.

For adults without a known diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease, the Task Force makes no recommendation for or against dietary counseling to promote a healthy diet (grade C). Instead, the Task Force encourages selective, rather than comprehensive, counseling of patients based on professional judgment and other considerations, such as readiness to change, social support, community resources, patient preference, and other clinical priorities.18

The Role of Dietary Counseling in Primary Care

Quality of Typical American Diets

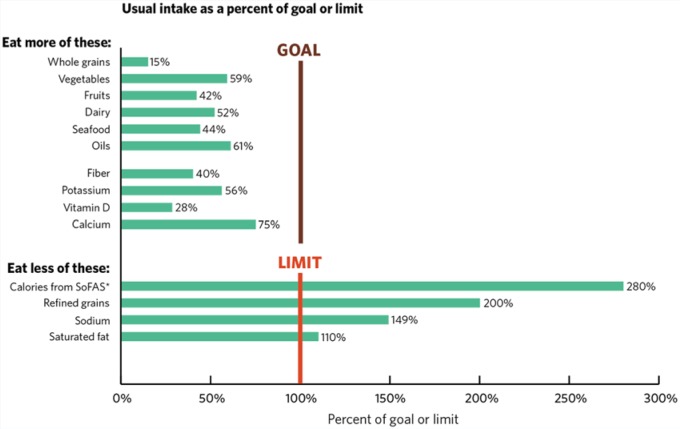

Despite national efforts to improve the nutritional quality of diets in the United States, the average American diet continues to be inconsistent with healthy eating patterns. As seen in Figure 1, Americans consume too many refined grains, too many calories from solid fats and added sugars, and too much sodium and saturated fat. Conversely, Americans consume inadequate amounts of important nutrients such as dietary fiber, potassium, vitamin D, and calcium.

Figure 1.

Typical American Diets Compared to Recommended Intake Levels8.

*SoFAS, solid fats and added sugars.

Note: Bars show average intakes for all individuals (ages 1 or 2 years or older, depending on the data source) as a percentage of the recommended intake level or limit. Recommended intakes for food groups and limits for refined grains and solid fats and added sugars are based on amounts in the USDA 2000-calorie food pattern. Recommended intakes for fiber, potassium, vitamin D, and calcium are based on the highest AI or RDA for ages 14 to 70 years. Limits for sodium are based on the UL and for saturated fat on 10% of calories. The protein foods group is not shown here because, on average, intake is close to recommended levels.

Based on data from: US Department of Agricultural, Agricultural Research Service and US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2001-2001 or 2005-2006.

The Healthy Eating Index (HEI) is a scoring system used to measure the nutritional quality of American diets compared to the Dietary Guidelines. The HEI is considered an indicator of diet quality for the US population, where higher HEI scores indicate diets more consistent with recommended eating patterns.22 The HEI has a range of applications, including monitoring population diet quality over time, determining the effectiveness of nutrition intervention programs, and assessing the quality of food assistance packages, menus, and the US food supply.

Similar to other national data sources, analyses using the recently updated HEI-2010 have not shown substantial improvements in the quality of typical American diets over the last decade.23 Diet quality and adherence to the Dietary Guidelines can be improved in the United States by increasing Americans’ intakes of fruits and vegetables, especially dark-green vegetables (eg, broccoli, spinach, and romaine) and beans (eg, kidney, pinto, and black beans) and peas (eg, black-eyed and split peas, chickpeas, and lentils) and substituting fat-free or low-fat dairy for higher-fat dairy products, whole-grain for refined-grain products, and seafood for some meat and poultry.

Improving the Quality of American Diets With Dietary Counseling

PCPs have a unique opportunity to promote a healthy diet in patients throughout the population using various types of behavioral strategies. Dietary counseling is a behavioral approach aimed at optimizing an individual’s nutrient intake by helping them identify and adopt healthy food choices over time. Effective dietary counseling may help decrease the burden of disease in patient populations, reduce preventable expenditures, and improve patient satisfaction.24,25 This strategy has been shown to help patients consume less total fat, saturated fat, and sodium and more fruits and vegetables,20 thus better aligning dietary patterns with Dietary Guidelines recommendations.8

Reimbursement for Diet-Related and Nutrition-Related Preventive Services

Despite increasing rates of obesity and chronic disease, weight-related lifestyle counseling has declined in primary care settings since the mid-1990s and remains low in both adults and children.26-28 Many factors contribute to low rates of diet-related preventive services in primary care, including barriers created by reimbursement structures in the health care system. The ACA helps address this issue in part by increasing coverage of clinical preventive services recommended by the Task Force with grades of A or B.29

Still, reimbursement for diet-related and nutrition-related clinical preventive services is often dependent on the frequency in which these services are provided. For example, Medicare waives the copayment for intensive behavioral therapy for obese adults,30 a grade B Task Force recommendation, whereas Medicaid coverage varies by state.31 The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services states that Medicare beneficiaries diagnosed as obese are entitled to a certain number of intensive behavioral counseling sessions in the primary care setting according to the following schedule:

One face-to-face visit every week for the first month of treatment;

One face-to-face visit every other week for months 2 to 6; and

One face-to-face visit every month for months 7 to 12 if the individual has achieved a documented weight loss of at least 3 kg.

For those who have not achieved this weight loss, additional counseling will only be reimbursed after a reassessment of their readiness to change and documentation of a current body mass index.30

Techniques for Dietary Counseling in the Primary Care Setting

Basic Dietary Messaging

The Dietary Guidelines emphasize that a healthy eating pattern is not a rigid prescription and should provide individualization and flexibility to accommodate cultural, ethnic, traditional, and personal preferences as well as various income levels. PCPs can help patients understand basic nutrition concepts and some of the many ways to consume a healthy diet using simple, targeted messages based on the Dietary Guidelines.

With the necessary resources and knowledge, PCPs can integrate basic dietary messages into their regular interactions with patients. PCPs should understand how to communicate two important overarching concepts about a healthy diet to patients: (a) balancing calories over time with appropriate food choices and physical activity to achieve and maintain a healthy weight, and (b) selecting nutrient-rich foods and beverages to receive the most health benefits from the diet.

Patients should also be encouraged to understand their individual nutrient needs and become comfortable making food choices that help them meet these needs over time. PCPs can play a role in teaching patients to account for the calorie and nutrient contribution of foods and beverages in their diet, determine how certain foods fit within a total healthy eating pattern, and follow safe food practices when handling, preparing, and eating foods. Table 2 outlines key messages based on the Dietary Guidelines and strategies PCPs can use to initiate nutrition dialogue during patient encounters. Messages and dietary counseling strategies should be targeted to meet the needs and desired health outcomes of individual patients.

Table 2.

| Key Message | Strategies | Potential Prevention Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Enjoy your food, but eat less |

Basic strategies

|

Weight loss or maintenance |

| Avoid oversized portions |

Advanced strategies

|

May reduce risk of many chronic diseases |

| Compare sodium in foods like soup, bread, and frozen meals—and choose foods with lower numbers |

Basic strategies

|

Reduce risk for high blood pressure |

Advanced strategies

|

Keeping blood pressure in the normal range reduces an individual’s risk of cardiovascular disease | |

| Drink water instead of sugary drinks |

Basic strategies

|

May be associated with lower body weight or weight maintenance |

| Make half your plate fruits and vegetables |

Basic strategies

Advanced strategies

|

May reduce risk of many chronic diseases May reduce risk of cardiovascular disease, including heart attack and stroke May be protective against certain types of cancer |

| Choose a variety of protein foods Eat seafood in place of some meat or poultry twice a week |

Basic strategies

Advanced strategies

|

May reduce risk factors for cardiovascular disease May support optimal fetal growth and development |

| Make at least half your grains whole grains |

Basic strategies

Advanced strategies

|

May reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease May be associated with lower body weight May reduce incidence of type 2 diabetes |

| Switch to fat-free or low-fat (1%) milk |

Basic strategies

Advanced strategies

|

Supports optimal bone health Reduce risk of osteoporosis and bone fractures |

| Some physical activity is better than none Aim for at least 2 hours and 30 minutes (150 minutes) a week of moderate-intensity physical activity, such as brisk walking, and 2 days a week of muscle strengthening |

Basic strategies

Advanced strategies

|

Weight loss or maintenance May reduce risk of many chronic diseases |

A Simplified Framework for Dietary Counseling

All dietary counseling strategies should incorporate the 5As Behavior Change Model approach recommended by both the Task Force and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services.30,33 This approach combines several evidence-based intervention strategies, including motivational interviewing, goal-setting, and modeling, into five steps: (a) assessing, (b) advising, (c) agreeing, (d) assisting, and (e) arranging for follow up.33

A provider using the 5As approach for dietary counseling would begin by assessing the patient’s diet-related risk factors and nutritional goals. Next the PCP would provide clear, specific, and personalized advice, attempting to collaborate with the patient based on interest and willingness. Once the PCP and patient agree on appropriate treatment goals and potential approaches for reaching those goals, self-help resources such as those discussed in this article can be offered to the patient to support his or her planned behavior change. Finally, PCPs should develop a follow-up plan for the patient based on his or her treatment plan and goals that includes future clinical appointments and other relevant interventions strategies, and emphasizes the iterative nature of goal setting and achievement.34

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a patient-based approach to counseling that draws from constructs embedded in various health promotion theories, including the Health Belief Model and Stages of Change (or Transtheoretical) Model.33,35 Recognizing a patient’s perception of illness susceptibility, facilitators and barriers to change, and self-confidence in his or her ability to change helps PCPs determine the most appropriate approaches for improving a patient’s dietary behaviors.

For example, a patient with a family history of stroke may be particularly concerned about preventing cardiovascular disease. In this case, a provider could potentially engage the patient in a meaningful discussion of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet, a dietary pattern recommended in the Dietary Guidelines for prevention and reduction of high blood pressure.

PCPs can incorporate motivational interviewing into dietary counseling by applying three basic principles: ask open-ended questions, listen to patients describe their experiences, and inform patients within the context of those experiences.36 A dietary counseling session that incorporates these techniques, therefore, may begin with an open-ended question such as, “How important is it for you to eat a nutritious diet?” This could be followed with a series of questions on past diet-related experiences: “Have you tried changing something in your diet before? What changes did you make? How did it go? What helped or hindered you in eating more or less of that particular food?” The provider may then use those responses as a springboard for discussing recommendations or messages from Dietary Guidelines that are most relevant to the patient based on his or her experiences and health status.

In addition, providers can use information obtained during motivational interviewing to assess a patient’s readiness to change a particular dietary behavior or pattern. For example, a highly motivated patient who is already making successful changes may require more nuanced nutrition guidance, while a less motivated patient may require rudimentary nutrition advice and a discussion of overcoming barriers to change. Table 2 provides examples of basic and advanced strategies for improving various dietary behaviors and health outcomes. Finally, PCPs should address realistic approaches for anticipating and avoiding relapses with all patients who express a desire to implement behavior change strategies.

Goal Setting

Goal setting is an important component of effective dietary counseling, both during the counseling encounter and thereafter. Behavior change goals can be established by either the patient or provider; however, goals are often more meaningful and achievable when developed by patients themselves or in collaboration with the PCP.34 During a counseling session, the process of establishing goals helps clarify patient expectations and priorities, and the process of working toward and achieving those goals helps boost patient confidence.35

Effective goal setting can be distilled to a few basic principles: goals should be specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound (SMART).37 In addition, the American Heart Association recommends nutritional goals focused on behaviors within the patient’s control rather than physiological endpoints.34 An example of a SMART goal related to dietary behaviors is reduce calories from added sugar by replacing one sugar-sweetened beverage with a glass of water at least once a day. A vague goal based on a physiological endpoint, such as decrease fasting blood glucose by consuming fewer sugar-sweetened beverages, may be less achievable and more difficult to measure.

Once a patient’s behavioral goals are established, a system of monitoring and positive reinforcement is critical for continuous progress and sustained dietary behavior change.35 Examples of dietary self-monitoring include regularly checking and recording body weight, weekly menu planning to support informed decision-making and help prevent impulse purchases of unhealthy foods in the grocery store, recording food choices in a paper- or technology-based food diary to track dietary behaviors and determine nutrient intakes, or wearing a pedometer to help estimate typical physical activity behaviors.

Even with appropriate counseling, goal setting, and monitoring—and despite a patient’s best intentions—relapses can and will occur. PCPs can help patients normalize these experiences while also teaching them to recognize the contextual factors that influence these relapses.34,35 If a patient is attempting to reduce sodium intake, for example, strategies for preventing relapses may include identifying foods in the diet that are high in sodium, recognizing triggers for consuming those foods, and learning about suitable alternatives that are lower in sodium.

Delivery Mechanisms for Dietary Counseling in the Primary Care Setting

Team-Based Approaches and Referrals

Extensive one-on-one dietary counseling is likely unrealistic for many PCPs who practice within the constraints of limited time and resources. In these situations, team-based approaches and referrals are particularly important and allow the PCP to collaborate with other providers with expertise in nutrition science, behavioral counseling, or other professional skill sets useful for addressing lifestyle behaviors. Referrals for additional guidance on dietary and nutrition-related issues can be made internally or externally to nutrition professionals such as a registered dietitian (RD) or discussed with other members of the multidisciplinary team such as registered nurses and social workers.

In primary care, RDs are essential to the multidisciplinary team where they support PCPs by providing individualized medical nutrition therapy to improve patient outcomes.38 RDs are experts in the translation of food and nutrition science into dietary and lifestyle behavior change strategies for individuals and populations, and often work in clinical practice. In addition to extensive training in complex food and nutrition concepts, some RDs are certified in specialized areas of practice, such as weight management, diabetes education, and sports nutrition.38 PCPs can use the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ free, online national referral service to locate an RD in their community (The Academy of Dietetics’ Find an RD online referral service can be accessed online at http://www.eatright.org/programs/rdfinder/).

Social workers may offer important assistance in identifying state and community resources available to help meet patient needs. For example, there are a number of food-related assistance programs available to Americans, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and WIC, which are briefly described in Table 3. PCPs and social workers can assist patients by providing the contact phone numbers for their local SNAP and WIC offices.39,40

Table 3.

Overview of SNAP and WIC Programs.

| Program | Population | Eligibility | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNAP | Open to everyone | Income, deduction, employment, and immigrant eligibility requirements | By phone: state SNAP hotline In-person: at local SNAP office |

| WIC | Pregnant women, children from birth to 5 years of age | Categorical, residential, income, and nutrition risk eligibility requirements | By phone: state or local WIC agency |

Group Sessions

Group-based sessions may also improve efficiency and effectiveness of dietary counseling in primary care. These sessions can occur either alone or in combination with individual-based sessions, and are often conducted by RDs. Group sessions may incorporate a variety of techniques, including skill-building exercises, traditional didactics, and coaching, and may take place at the health care facility or within the community, such as in the workplace or in a church setting.34

Modeling techniques can be applied during shared medical appointments or group counseling settings to facilitate observational learning and reinforce positive behaviors among multiple patients. This approach helps individuals learn how to apply dietary behavior changes by observing and replicating the positive behavior of others. Examples of dietary modeling techniques include the use of online cooking tutorials or in-person demonstrations of healthy food preparation, as well as educational trips to grocery stores to increase a patient’s confidence in selecting affordable, healthy foods.34

Community-based programs can also be considered in the context of group-based interventions. A number of large community-based initiatives have been implemented nationwide, including “We Can!” and the “Eat Healthy, Be Active Community Workshops.” RDs may be available to assist in maintaining a comprehensive list of community or local programs to distribute to patients as necessary. Table 4 provides a list of select federal resources related to the Dietary Guidelines that are within the public domain and available for public use and distribution.

Table 4.

Select Federal Nutrition and Physical Activity Resources Within the Public Domain.

| Title | Description | Web Site URL |

|---|---|---|

| Consumer Resources | ||

| Eat Healthy • Be Active Community Workshops | Series of six, 1-hour lesson plans based on the DGA and PAG, includes talking points, activities, video vignettes, handoutsa | www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/workshops |

| Be Active Your Way (Physical Activity Guidelines) | Brochures, fact sheetsa, infographica, blog | www.health.gov/paguidelines/adultguide/ |

| Choose MyPlate | Ten tips series, daily meal plans, videos, menus, recipes; SuperTracker (ie, diet and physical activity tracking tool) | www.choosemyplate.gov |

| 10 Tips Nutrition and Physical Activity Series | One-page tip sheets on a variety of nutrition and physical activity topics | www.choosemyplate.gov/healthy-eating-tips/ten-tips.html |

| Presidential Active Lifestyle Award (PALA+) | Six-week program based on the DGA and PAG to track individual eating and physical activity levelsa | www.presidentschallenge.org/ |

| Let’s Move! | Tips, tools, resources for parents, children, schools on nutrition and physical activity | www.letsmove.gov |

| We Can! | Information, toolkits, worksheets, tips for youth ages 8-13 to maintain a healthy body weight, portion distortion information, and quiz comparing portions from 20 years ago | www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/obesity/wecan/ |

| Healthfinder.gov | Information, resources, and tools on a variety of health topics | www.healthfinder.gov |

| Fruit & Veggies—More Matters | Recipes, meal planning, tips | www.fruitsandveggiesmorematters.org/ |

| Bright Futures | Tips, resources, handouts, newsletters to improve children’s health care needs | www.brightfutures.aap.org |

| BodyWorks | Tools and resources for parents and caregivers of adolescents to improve family eating and physical activity habitsa | www.womenshealth.gov/index.html |

| Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension Eating (DASH) Plan | DASH eating plan, daily nutrient goals | www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/dash/ |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) Calculator | Input height and weight to determine BMI | www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/BMI/bmicalc.htm |

| Government Reports and Resources | ||

| Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) | Policy document, Advisory Committee Report, key messages, previous versions of the DGA | www.dietaryguidelines.gov |

| Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (PAG) and PAG Midcourse Report | Policy document, Advisory Committee Report, key messages | www.health.gov/paguidelines |

| Healthy People | Ten-year health objectives for the nation | www.healthypeople.gov |

Denotes materials are available in Spanish.

Technology-Based Interventions and Printed Education Materials

Additional alternatives to one-on-one dietary counseling may involve engaging patients through technology-based strategies or interventions. Interactive behavior change technologies allow delivery of behavior-change interventions strategies via telephone, e-mail, or the Internet.41 Although the specifics of these interventions are beyond the scope of this article, successful examples using telephone42 and Web-based43,44 approaches have had similar methodologies: counselors made periodic contact with patients and used cognitive-behavioral strategies to help them track progress toward goals.

Technology-based interventions are less suitable for patients with limited access to technology or those unfamiliar with the use or application of certain technologies. In these cases, printed materials such as those listed in Table 4 can also provide a helpful supplement to in-office counseling. Like their technological equivalents, print-only strategies should be tailored to the individual patient, taking into account eyesight, reading level, understanding of health concepts, and cultural background.34 Depending on the patient population they serve, clinics may consider keeping large-print and non-English language handouts.

Conclusion

As the US health care system evolves, PCPs have new and expanded opportunities to address diet-related and lifestyle-related behaviors in clinical practice to reduce the burden of chronic disease in the population. In the United States, patients often consider PCPs’ advice to be authoritative and credible, and look to them for guidance on individual food choices and physical activity behaviors.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans provide food-based guidance for the general public and specific subpopulations to help all Americans achieve their highest standard of health through optimal nutrition and regular physical activity. These national recommendations help health care professionals and clinicians address dietary behaviors efficiently and effectively in a variety of settings, including primary care.

Patient–provider encounters are valuable opportunities to engage individuals in dialogue about their lifestyle behaviors. Even with limited time, PCPs can address unhealthy dietary behaviors and physical inactivity with patients using targeted, easy-to-understand messages based on Dietary Guidelines recommendations and individualized dietary counseling. In addition to one-on-one behavioral counseling, PCPs can use electronic and print resources to encourage healthy food choices in patients through education, goal setting, and monitoring; encourage patients to access appropriate existing community resources such as WIC and SNAP programs; and refer patients to another member of the multidisciplinary health care team such as a registered dietitian.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the following individuals for their valuable contributions to the development of this article: Subhashini Katumuluwa, MD, at Stony Brook University Medical Center, and Gene Donovan, MD, and Mary Donovan, MD. The authors also acknowledge the following individuals for their review of this article: Don Wright, MD, MPH, Angela Hutson, RN, and Holly McPeak, MS, at the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion at the US Department of Health and Human Services; Eve Essery Stoody, PhD, at the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion at the US Department of Agriculture; Derek Mazique, MD, at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine; and Daniel Burnett, MD, at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.

The findings and conclusions of this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, the US Department of Health and Human Services, or the US Department of Defense

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine. Primary Care and Public Health: Exploring Integration to Improve Population Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6-e245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chronic diseases and health promotion. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/index.htm#ref1. Published 2010. Accessed July 2013.

- 4. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Center for Public Health Policy, American Public Health Association. The Prevention and Public Health Fund: a critical investment in our nation’s physical and fiscal health. http://www.apha.org/NR/rdonlyres/8FA13774-AA47-43F2-838B-1B0757D111C6/0/APHA_PrevFundBrief_June2012.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed June 2013.

- 6. US Department of Agriculture, US Department of Health and Human Services. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slawson DL, Fitzgerald N, Morgan KT. Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: the role of nutrition in health promotion and chronic disease prevention. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:972-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Department of Agriculture, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th ed. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watts ML, Hager MH, Toner CD, Weber JA. The art of translating nutritional science into dietary guidance: history and evolution of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:404-412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Spahn JM, Lyon JM, Altman JM, et al. The systematic review methodology used to support the 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:520-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture. Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/cnr_2010.htm. Accessed May 1, 2013.

- 12. Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture. Summary of the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. (By program). http://www.fns.usda.gov/cnd/governance/legislation/PL111-296_Summary.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2013.

- 13. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Focus on Health Reform: summary of the Affordable Care Act. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2011/04/8061-021.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2013.

- 14. Benjamin D, Sommers LW. ASPE Issue Brief: Fifty-four million additional Americans are receiving preventive services coverage without cost-sharing under the Affordable Care Act. http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2012/PreventiveServices/ib.shtml. Published 2012. Accessed June 2013.

- 15. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of selected clinical preventive services among adults—United States, 2007-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(suppl):1-84. [Google Scholar]

- 16. US Preventive Services Task Force. The Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 2012. Washington, DC: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 17. US Preventive Services Task Force. Behavioral counseling in primary care to promote a healthy diet: recommendations and rationale. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24:93-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moyer VA. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:367-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moyer VA. Screening for and management of obesity in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157:373-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lin JS, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, et al. Behavioral Counseling to Promote Physical Activity and a Healthful Diet to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: Update of the Evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Prevention Council. National Prevention Strategy. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, US Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guenther PM, Casavale KO, Reedy J, et al. Update of the Healthy Eating Index: HEI-2010. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113:569-580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hiza HAB, Guenther PM, Rihane CI, Diet quality of children age 2-17 years as measured by the Healthy Eating Index-2010. Nutr Insight. 2013;52 http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/Publications/NutritionInsights/Insight52.pdf. Accessed January 21, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Post RE, Mainous AG, 3rd, Gregorie SH, Knoll ME, Diaz VA, Saxena SK. The influence of physician acknowledgment of patients’ weight status on patient perceptions of overweight and obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:316-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Potter MB, Vu JD, Croughan-Minihane M. Weight management: what patients want from their primary care physicians. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:513-518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kraschnewski JL, Sciamanna CN, Stuckey HL, et al. A silent response to the obesity epidemic: decline in US physician weight counseling. Med Care. 2013;51:186-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smith AW, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. U.S. primary care physicians’ diet-, physical activity-, and weight-related care of adult patients. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:33-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang TT, Borowski LA, Liu B, et al. Pediatricians’ and family physicians’ weight-related care of children in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41:24-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. US Preventive Services Task Force. USPSTF A and B recommendations. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsabrecs.htm. Accessed August 17, 2013.

- 30. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, US Department of Health and Human Services. Decision Memo for Intensive Behavioral Therapy for Obesity (CAG-00423N). http://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?&NcaName=Intensive%20Behavioral%20Therapy%20for%20Obesity&bc=ACAAAAAAIAAA&NCAId=253&. Published 2011. Accessed August 2, 2013.

- 31. Lee JS, Sheer JL, Lopez N, Rosenbaum S. Coverage of obesity treatment: a state-by-state analysis of Medicaid and state insurance laws. Public Health Rep. 2010;125:596-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. US Department of Agriculture. Healthy eating tips. http://www.choosemyplate.gov/healthy-eating-tips.html. Accessed August 2013.

- 33. Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:267-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Artinian NT, Fletcher GF, Mozaffarian D, et al. Interventions to promote physical activity and dietary lifestyle changes for cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2010;122:406-441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rimer BK, Glanz K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rollnick S, Butler CC, Kinnersley P, Gregory J, Mash B. Motivational interviewing. BMJ. 2010;340:c1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Doran G. There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Manage Rev. 1981;70:35-36. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Academy Quality Management Committee, Scope of Practice Subcommittee of Quality Management Committee. Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: scope of practice for the registered dietitian. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(6 suppl):S17-S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Food and Nutrition Service, US Department of Agriculture. Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) state information/hotline numbers. http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/contact_info/hotlines.htm. Accessed May 1, 2013.

- 40. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service. Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) toll-free numbers for WIC state agencies. http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/Contacts/tollfreenumbers.htm. Accessed May 1, 2013.

- 41. Glasgow RE, Bull SS, Piette JD, Steiner JF. Interactive behavior change technology. A partial solution to the competing demands of primary care. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27(2 suppl):80-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Newman VA, Flatt SW, Pierce JP. Telephone counseling promotes dietary change in healthy adults: results of a pilot trial. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008;108:1350-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Alexander GL, McClure JB, Calvi JH, et al. A randomized clinical trial evaluating online interventions to improve fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:319-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van Wier MF, Dekkers JC, Hendriksen IJ, et al. Effectiveness of phone and e-mail lifestyle counseling for long term weight control among overweight employees. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53:680-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]