Abstract

Introduction. Prediabetes is a prevalent disease that has been associated with its own health risks and is a known precursor of type 2 diabetes. Lifestyle interventions are known to effectively treat prediabetes but are often not offered to patients within a primary care setting. Study Design. Exploratory and descriptive study. Objective. To assess if the use of a health coaching intervention among primary care patients, with prediabetes, warrants further examination. Methods. A retrospective chart review was conducted for all patients who had prediabetes and received health coaching at the Ambulatory Practice of the Future between 2012 and 2014. Discussion. A health coaching intervention used among primary care patients, with prediabetes, deserves further examination, as participants had a significant reduction in hemoglobin A1c and weight over 2 years.

Keywords: primary care, health coaching, weight loss, prediabetes

‘Most patients with prediabetes do not receive proven interventions that prevent or slow this progression . . .’

An estimated one third of American adults have prediabetes.1 Without lifestyle changes, these individuals have an increased risk of chronic kidney and cardiovascular disease,2,3 while 15% to 30% will develop diabetes within 5 years.4 Most patients with prediabetes do not receive proven interventions that prevent or slow this progression, often because their clinicians lack the knowledge or time to deliver them.5,6

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Diabetes Prevention Program is one such lifestyle intervention that uses biweekly supervised exercise sessions and 30- to 60-minute dietary counseling sessions and behavioral modification over 16 weeks.7 This intervention has shown the potential to reduce the risk of developing diabetes by 58%.7 Most primary care settings do not have the resources to provide such comprehensive educational and behavioral lifestyle interventions,8 but there is some evidence that primary care patients enrolling in prediabetes interventions are well-informed of their condition but need a structured path to enact change, suggesting that the behavioral component alone may offer some benefit.9,10

Health coaching is a patient-centered process that is based on behavior change theory,11 which focuses on promoting patient self-efficacy, therefore requiring less time and fewer resources than standardized counseling, and has been shown to reduce HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes.12 Therefore, the primary objective of this exploratory study was to assess if the use of a health coaching intervention among primary care patients, with prediabetes, warrants further examination. To make this assessment, we used a retrospective chart review to examine the feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a primary care–based, behavioral health coaching intervention for adults with prediabetes.

Methods

Subjects

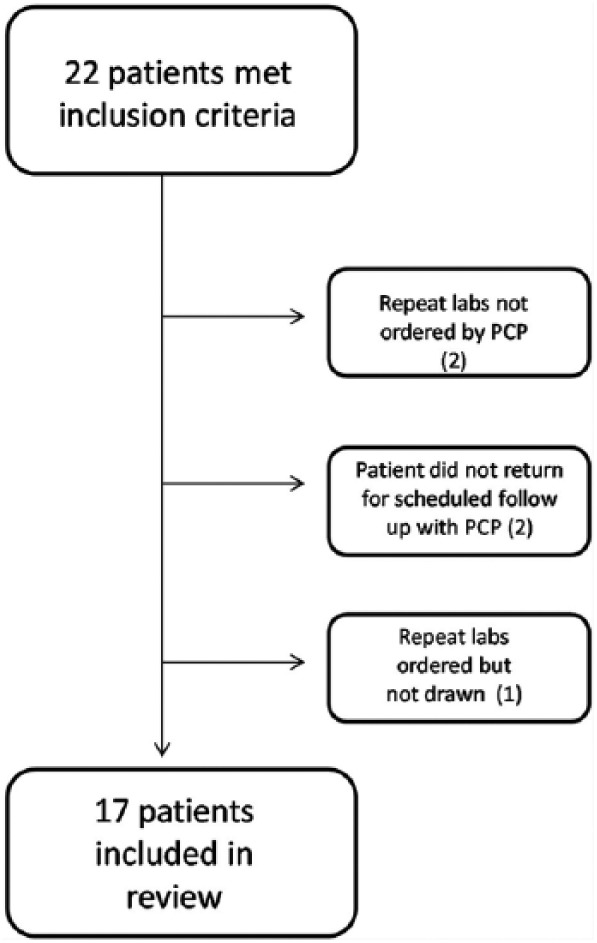

In this exploratory study, we examined charts of patients who had prediabetes (HbA1c 5.7% to 6.4%) and received health coaching between 2012 and 2014 at the Ambulatory Practice of the Future (APF). This study was approved by the Partners Healthcare institutional review board. The APF is a primary care practice at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) that serves MGH employees and their spouses. Participants were referred to coaching by their primary care physician (PCP) or a nurse practitioner. We excluded patients who did not have an HbA1c tested by their PCP at 24 months postintervention (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Participant recruitment.

Procedures

Patients who enrolled in health coaching agreed to participate for at least 12 weeks with the APF’s health coach (RS), a certified health coach and a registered clinical exercise physiologist. All patients received usual care by their PCP throughout the time of the study.

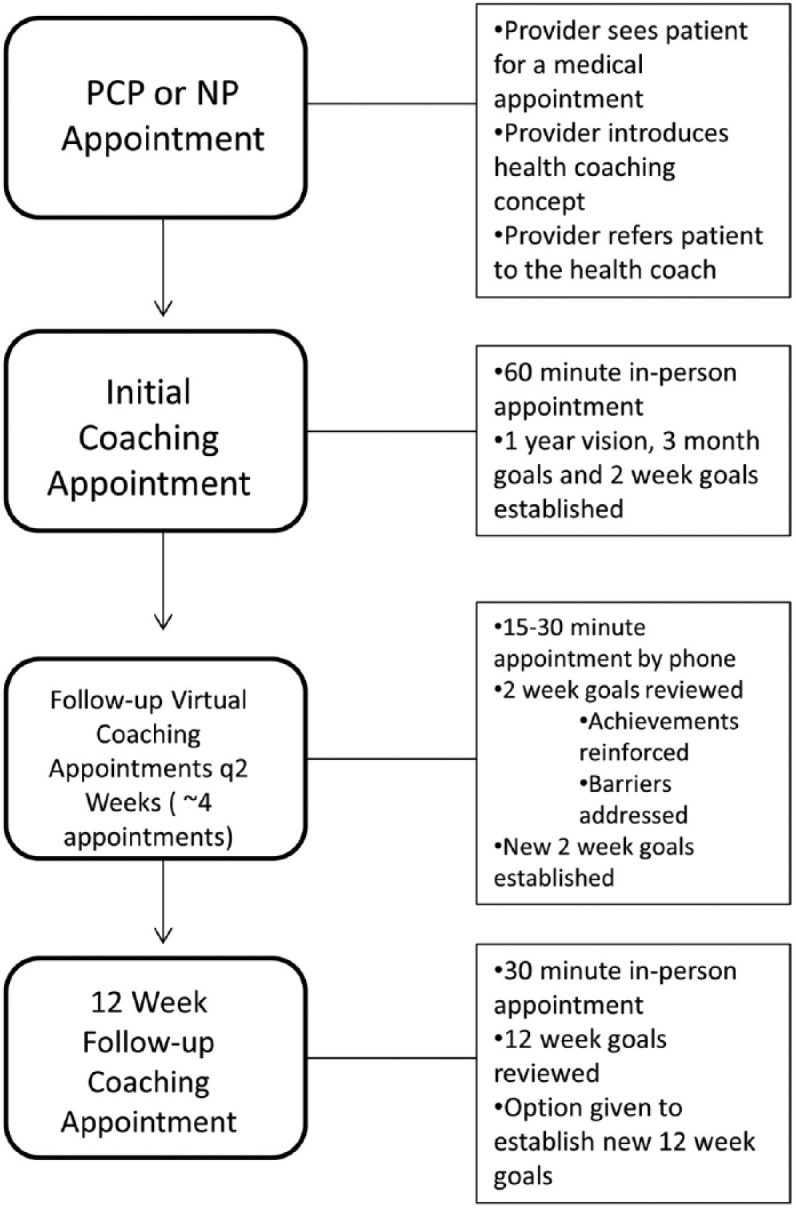

Coaching was based on the Wellcoaches protocol, which integrates several models of behavioral evaluation and engagement including motivational interviewing, self-determination theory, transtheoretical model, positive psychology, and relational flow.13 The health coach did not provide advice or education unless the patient explicitly requested it. Figure 2 describes the content and the structure of the health coaching visits. Each patient was asked to return to the APF to obtain a follow-up weight and HbA1c at 6 months, regardless of their engagement with coaching after the third month.

Figure 2.

Health coaching appointment flow chart.

+PCP = primary care physician; ++NP = nurse practitioner.

Measurements and Statistical Analysis

We reviewed the charts of all APF patients who had prediabetes and were seen by the health coach between 2012 and 2014. We collected HbA1c, weight, body mass index (BMI), age, gender, race, level of education, presence of comorbid conditions including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, and anxiety, and number of coaching encounters.

Demographic data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Mean HbA1c and BMI before and after health coaching at 6 and 24 months was compared using a repeated-measures ANOVA test. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 23 (Chicago, IL).

Results

We examined 17 adults ranging in age from 32 to 71 years. The majority of patients were white, and all patients attended at least some college. The majority of patients had at least one other comorbidity (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Participants (N = 17).

| Age, mean (SD) | 52 (12.44) |

| Gender (male), n (%) | 10 (59) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 15 (88) |

| Asian | 2 (12) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 11(65) |

| Hypertension | 4 (23) |

| Depression and/or anxiety | 3 (18) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 13 (76) |

| Some college | 4 (24) |

On average, patients participated in 7 coaching sessions over 5 months (range = 3-6 months). The most common goals set by patients were related to cardiovascular exercise (82%), strength training (71%), food preparation (59%), reducing empty calorie intake (eg, alcohol or dessert; 29%), and increasing fruit and vegetable intake (29%).

Mean HbA1c decreased from 5.85% (95% confidence interval = 5.79% to 5.90%) prior to health coaching to 5.72% (95% confidence interval = 5.68% to 5.76%) at 6 months and 5.62% (95% confidence interval = 5.56% to 5.68%) at 24 months (P < .001). Mean baseline weight decreased from 195.2 lbs to 188.5 lbs at 6 months and to 183.7 lbs at 24 months (P < .001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Body Weight and HbA1c of Participants Over Time.

| HbA1c |

Weight |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (%) | 95% CI | Mean (lb) | 95% CI | |

| Baseline | 5.85 | [5.79%, 5.90%] | 195.2 | [192.1, 198.3] |

| 6 Months | 5.72 | [5.68%, 5.76%] | 188.5 | [187, 190] |

| 24 Months | 5.64* | [5.56%, 5.68%] | 183.7* | [180.1, 187.3] |

Abbreviations: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; CI, confidence interval.

P < .001 difference between HbA1c and weight at baseline and 24 months.

Discussion

Our exploratory study indicated that patients who received health coaching achieved significant reductions in HbA1c and body weight after 2 years. Of note, HbA1c and weight continued to improve after coaching ended, which suggests the potential for a sustained effect of the intervention. These results suggest that a health coaching intervention used among primary care patients, with prediabetes, deserves further examination.

This exploratory study has inherent limitations, such as the lack of a comparison group and selection bias. Our study also has limited generalizability given that the patients were predominately white, commercially insured, and college-educated. Furthermore, the APF serves a unique population of hospital employees and their spouses who may have chosen the clinic based on their prior interest and commitment to coaching. Our study was also limited by the use of one health coach, as the results could be an effect of the coach’s personal strengths rather than the coaching methodology.

Due to these limitations, a direct correlation between use of a health coaching model and a reduction in HbA1c in primary care patients, with prediabetes, cannot be made. However, this study generated a hypothesis that deserves further investigation: the health coaching model can be applied to reduce HbA1c in primary care patients with prediabetes. To fully investigate this hypothesis, a multicenter, multicoach, randomized control study is needed to evaluate the impact of implementing a health coaching intervention to manage prediabetes within a primary care setting.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Plantinga LC, Crews DC, Coresh J, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in US adults with undiagnosed diabetes or prediabetes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:673-682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coutinho M, Gerstein HC, Wang Y, Yusuf S. The relationship between glucose and incident cardiovascular events. A metaregression analysis of published data from 20 studies of 95,783 individuals followed for 12.4 years. Diabetes Care.1999;22:233-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prediabetes. http://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/basics/prediabetes.html. Accessed April 11, 2016.

- 5. Stevens JW, Khunti K, Harvey R, et al. Preventing the progression to type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults at high risk: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of lifestyle, pharmacological and surgical interventions. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;107:320-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fonseca VA. Identification and treatment of prediabetes to prevent progression to type 2 diabetes. Clin Cornerstone. 2008;9:51-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165-2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mainous AG, Tanner RJ, Baker R. Prediabetes diagnosis and treatment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29:283-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baker MK, Simpson K, Lloyd B, Bauman A, Singh MAF. Behavioral strategies in diabetes prevention programs: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kolb JM, Kitos NR, Ramachandran A, Lin JJ, Mann DM. What do primary care prediabetes patients need? A baseline assessment of patients engaging in a technology-enhanced lifestyle intervention. J Bioinform Diabetes. 2014;1(1):4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolever RQ, Simmons LA, Sforzo GA, et al. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: defining a key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;4(2):38-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moore M, Tschannen-Moran B. Coaching Psychology Manual. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]