Abstract

Social connection is a pillar of lifestyle medicine. Humans are wired to connect, and this connection affects our health. From psychological theories to recent research, there is significant evidence that social support and feeling connected can help people maintain a healthy body mass index, control blood sugars, improve cancer survival, decrease cardiovascular mortality, decrease depressive symptoms, mitigate posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and improve overall mental health. The opposite of connection, social isolation, has a negative effect on health and can increase depressive symptoms as well as mortality. Counseling patients on increasing social connections, prescribing connection, and inquiring about quantity and quality of social interactions at routine visits are ways that lifestyle medicine specialists can use connection to help patients to add not only years to their life but also health and well-being to those years.

Keywords: connection, lifestyle medicine, healthy habits, social life, friendships, loneliness

‘“Incorporating social support and connections is critical for overall health and for healthy habits to be sustainable.”’

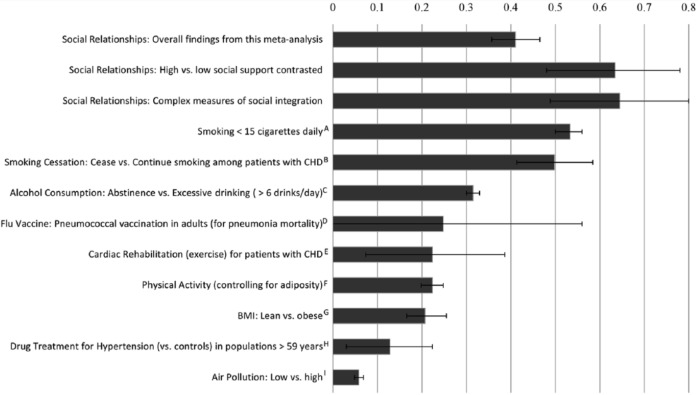

It is time to appreciate and utilize connection and social bonds as part of lifestyle counseling. Individuals need connections in their lives in the workplace and at home. Fostering these connections is critical to health and wellness. Lifestyle medicine is the growing specialty that works to formalize the counseling and prescriptions for healthy habits, including regular exercise, nutritious foods, stress management, smoking cessation, and moderate alcohol use. Incorporating social support and connections is critical for overall health and for healthy habits to be sustainable. The social ecological model of change stresses that we exist in communities and these groups have an important impact on individuals and their behaviors. There are decades of research that support the importance of social connection. Moreover, humans have lived in groups for thousands of years. In a meta-analysis by Holt-Lunstad and colleagues1 at Brigham Young University, they examined 148 articles published on the effects of human interactions on health outcomes, and they reported that social connections with friends, family, neighbors, or colleagues improves the odds of survival by 50%. High social support and social integration are associated with the lowest relative odds of mortality compared to many other well accepted risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Figure 1). The review article by Holt-Lunstad and colleagues is a powerful demonstration of the evidence base behind social connection and health. Low social interaction was reported to be similar to smoking 15 cigarettes a day and to being an alcoholic, to be more harmful than not exercising, and to be twice as harmful as obesity.1 In addition, the devastating effects of loneliness and social isolation have been well researched.

Figure 1.

Comparison of odds (ln OR) of decreased mortality across several conditions associated with mortality.

Note: Effect size of zero indicates no effect. The effect sizes were estimated from meta analyses: A = Shavelle et al, 20082; B = Critchley and Capewell, 20033; C = Holman et al, 19964; D = Fine et al, 19945; E = Taylor et al, 20046; F, G = Katzmarzyk et al, 20037; H = Insua et al, 19948; I = Schwartz, 1994.9

Reprinted from Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316.

Prescribing social interactions and encouraging friendships has the potential to have a healing effect on patients. Social connection should be viewed and treated as a vital sign much like physical activity. The “Exercise Is Medicine” campaign helped bolster support for the exercise prescription. The time is right for a “Connection Is Medicine” campaign. Asking patients how many close friends they have, if they belong to any organizations or groups that meet regularly, and how often they spend time socializing with others is one way to ensure that social connection receives the attention it deserves. Answers to these questions can be used to improve a patient’s weight management, diabetes control, hypertension, mood, and even immune function. By exploring the research from 50 years ago as well as the most recent data, this article strives to highlight the power of social interactions and to introduce the concept of the connection prescription as an integral part of the health care equation.

History of Connection as a Basic Human Need

Seminal psychological theories, such as Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs,” included the concept of social connection.10 Abraham Maslow documented and explained the importance of connection, which he called “love and belongingness,” in his book Motivation and Personality, published in 1954. In his hierarchy, there are 5 important needs for psychological growth and development: (a) physiological, (b) shelter, (c) love and belongingness, (d) esteem, and (e) self-actualization. As Maslow describes it, feeling part of a group larger than oneself such as a work community, religious affiliation, community center, volunteer organization, team, interest group, or club is an essential component in the self-actualization process. Close associations with other, smaller groups or even dyads, such as immediate family, close friend, or a life partner, and specifically feeling close to someone, not lonely, are also important for human health and happiness. The self-determination theory developed by psychologists, Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, focuses on 3 basic human needs for sustained, volitional motivation: (a) autonomy, (b) competence, and (c) relatedness. Relatedness is referred to as feeling socially connected to others.11 This is similar to the love and belongingness in Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs.” According to Ryan and Deci,11 when 1 of these 3 basic needs is obstructed, then a person suffers. It is only when all 3 needs are met that a person feels motivated to tenaciously pursue goals and can thus achieve optimal performance, creativity, and well-being.

Many prominent psychologists and psychiatrists have written extensively about social interactions and their importance in human development. For example, Dr Robert Brooks, a Harvard psychologist, clearly demonstrates the profound effect of just one charismatic adult in a person’s life in his books, Raising Resilient Children, The Charismatic Advisor, and the Power of Resilience. Dr Brooks defines a charismatic adult as a person who a child feels connected to and from whom the child gathers strength. This strength helps children manage through adversity and to persevere despite setbacks. Children are not the only ones who need charismatic adults in their lives. Adults need these people too. The term charismatic adult was originally coined by the late Dr Julius Segal, a psychologist and trauma expert who wrote Winning Life’s Toughest Battles: Roots of Human Resilience,” published in 1986. Dr Brooks carries forward the importance of the charismatic adult and the value of this influential connection in his works and writings today. Connections to others have the potential to propel us forward in our goals and encourage us to persevere when times are difficult.

The Physiological Basis of Connection

From the beginning of our lives, we are wired to connect. First, as a newborn, the sound of her baby’s cry, prompts the production of oxytocin in the mother. Oxytocin is the hormone produced in nerve cell bodies in the hypothalamus and then released into the bloodstream from the posterior pituitary. This hormone serves as a signal for the mother to bond with her child, as it causes milk let down for breastfeeding. Oxytocin is not just released in a mother when she hears her baby crying, but it also has other functions in addition to milk let down. There is evidence that oxytocin is released with holding hands, hugging, massaging, and sexual intimacy, Researchers have discovered that petting an animal can cause the release of oxytocin and a pleasant feeling results. There is evidence that oxytocin works in concert with other neurotransmitters such as γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–inhibitory neurons for anti-anxiety, through serotonin, a neurotransmitter involved in mood regulation, and through dopamine, a neurotransmitter involved with the nucleus accumbens and the reward system creating feelings of pleasure. Oxytocin seems to facilitate a social attunement, activating more for social stimuli (faces) and activating less for nonsocial stimuli (cars).12 For these reasons, oxytocin is often called the “bonding hormone.”

Definition of Connection

Edward Hallowell, MD, published a book, titled Connect, in 1999 that focuses on how and why we need connection in our lives. Dr Hallowell, a psychiatrist who has written extensively on the power of connection and has successfully used it as an intervention, defines connection as “feeling a part of something larger than yourself, feeling close to another person or group, feeling welcomed, and understood.”13 There are many examples of connections.

A five-minute conversation can make all the difference in the world if the parties participate actively. To make it work, you have to set aside what you’re doing, put down the memo you were reading, disengage from your laptop, abandon your daydream and bring your attention to bear upon the person you are with. Usually, when you do this, the other person (or people) will feel the energy and respond in kind, naturally.13(pp126)

Another leader in the area of social interactions, Jane E. Dutton, PhD, studies high-quality connections and defines connection as

the dynamic, living tissue that exists between two people when there is some contact between them involving mutual awareness and social interaction. The existence of some interaction means that individuals have affected one another in some way, giving connections a temporal as well as an emotional dimension.14

These connections are significant and can be life altering.

Research on the Health Benefits of Connection

The health benefits of social connections span from enhanced mood to lower blood pressure and result in decreased mortality. Lisa Berkman and Leonard Syme completed the landmark study in 1979 that showed people with strong social ties were 3 times less likely to die than those who were less connected to others.15 In fact, they found close social ties to be a protective factor with regard to health: People who had unhealthy habits such as smoking, obesity, and physical inactivity but embraced close social ties lived longer than those who had more health promoting habits but lacked these important social connections.

Social Connection and Body Mass Index

Americans are struggling with obesity. More than 30% of American adults are obese.16 Since June 2013, obesity has been a documented diagnosis in a patient’s chart. Exercise and nutrition counseling are key pieces of the treatment plan to date, and in the future social connection will likely be a staple of obesity treatment, due to recent research findings. There is evidence of a relationship between body mass index (BMI) and social connection: those who have more social supports have lower BMIs. For example, a national longitudinal study researching the effects of school environments on adolescents found that the more socially connected girls feel to each other and to the school, the lower their BMIs, and for the boys—the more they got along with teachers and other students as well as the more they felt that teachers treated students fairly, the lower their BMIs.17

In recent years, childhood obesity has been a focus of discussion and research. Investigators are searching for methods to help children attain and maintain a healthy BMI. A study evaluating 5 Head Start programs in a small north-eastern city researched the use of a family ecological model for weight management, which examined many different factors, including social connectedness to neighbors and friends.18 The importance of involving the entire family in the treatment of childhood obesity is becoming more and more clear. The social ties within the family and within the community are powerful forces in the lives of children.

A cross-sectional study completed by Lee and colleagues19 examined 657 Koreans aged 60 years and older who participated in the Korean Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. The researchers studied network size, which was defined as the number of friends an individual reported, density of community network, which was defined as the number of connections in an individual’s social network reported as fraction of the total links possible in that person’s network, and the average frequency of communication defined as how frequently network members communicated with each other. They found that men with lower density and higher network size had a higher body mass index when compared with men with higher density and lower network size (P = .037). In women, Lee’s group found communication frequency to be extremely important because the lowest level of communication frequency in women was associated with higher body mass indexes (P = .049). Although this study was limited to an elderly Korean population, it demonstrates that social connections, both their quality and quantity, can have a significant impact on BMI in adults.19

Social Connection and Diabetes

Another disease sweeping the nation as well as other countries worldwide is diabetes. It, too, has been correlated with connectedness. Research studies have identified social connection as a positive influence on health behaviors as well as HbA1c levels in individuals living with type 2 diabetes. One such study, conducted by Shaya and colleagues,20 examined the effectiveness of a connection intervention compared with a control group. The subjects were older than 18 years and had HbA1c levels greater than 7% and blood glucose greater than 110 mg/dL. Both groups received the same amount of diabetes education, but the teaching style differed greatly between the control group and intervention group. While the control group focused solely on a lecture style education, the intervention group focused on team-building exercises as well as sharing diabetes information among participants in their cluster. The subjects in the intervention group were asked to recruit peers and family members who met the same study inclusion criteria, thus forming small clusters. The researchers found that after 6 months individuals randomized into the intervention group involving social connections had a significantly greater decrease in HbA1c and blood glucose than individuals in a control group.20 More specifically, at 6 months, subjects in the interactive group had a decrease in HbA1c of 0.81% while the control group dropped by 0.50% (P < .0001). Also, the intervention group experienced a decrease in blood glucose of 19.3 mg/dL while the control group dropped by 8.72 mg/dL (P < .0001). Not only did subjects in the intervention group have substantially more diabetes knowledge after 6 months (P = .01) as well as increased self-efficacy (P = .004) than individuals in the control group, but researchers also found that subjects in the intervention group experienced a greater decrease in weight than controls by 2.98 pounds at the end of 6 months (P = .07). This particular study was limited by the low number of subjects (hundreds) and the fact that the subjects were from a largely African American population in Baltimore. Another limitation of the study was the short follow-up of 6 months. Nevertheless, the results emphasize the power of the group and peer support.

Other studies corroborate similar findings about diabetes and social interactions. For example, a randomized controlled trial conducted by Thom and colleagues21 in 2013 trained individuals from 6 public health clinics in San Francisco who had an HbA1c level of less than 8.5% to be peer coaches. The training was a 36-hour program focussed on nonjudgmental communication, active listening, social and emotional support strategies, as well as diabetes self-management.21 To become a peer coach, these individuals had to pass a written and an oral exam after completing the training. The patients were recruited from the same clinics as the peer coaches. The patients in the study had a HbA1c level of 8.0% or more. Then, the patients were randomized into usual care that included access to nutritionists and diabetes education through referrals from primary care doctors, or a treatment group using a trained peer coach that involved a telephone call with the coach at least twice a month and 2 or more in-person meetings with the coach every 6 months. Individuals in the peer-coached group were found to have a decrease in HbA1c level of 1.07% at 6 months in comparison with a 0.30% decrease in HbA1c levels in the usual care group (P = .01 adjusted). This is a difference of 0.77% in favor of peer coaching. The significance of connection and the power of peer support from individuals with similar symptoms on patients dealing with type 2 diabetes are clearly demonstrated in this study.

Connection and Cancer Patients

Connections help improve the life and health of cancer patients. In an article by Engebretson and colleagues,22 cancer survivors of advanced stages of their diseases who lived an average 11 years after their initial diagnosis were all interviewed and major themes were pulled out of their narratives. The most obvious and consistent theme among all fourteen subjects was strong connections to family, friends, and medical staff. These strong connections lead to an increased desire to live.22 These cancer survivors also recounted a more pleasurable experience when connection remained intact throughout their illness. This retrospective, narrative study suggests having strong social connections might play a role in decreased mortality in cancer patients.

In a randomized controlled intervention published in the Lancet, Spiegel and colleagues23 studied 86 women with metastatic breast cancer. They used a 1-year intervention consisting of weekly supportive group therapy plus self-hypnosis for pain and a control group receiving the routine standard of care. At a 10-year follow-up, there were 3 surviving subjects. Thus, data on death rates were collected from death records. The women in the intervention group survived on average 36 months while the control group survived half as long, 18 months. This shows the power of connections in the form of supportive group therapy.

In another study investigating cancer patients, Costanzo et al24 explored the effect of social connections on interleukin-6 (IL-6), a pro-inflammatory cytokine. In their cross-sectional study of 61 ovarian cancer patients older than 18 years, the researchers evaluated self-report questionnaires on social support, distressed mood, and quality of life. They also analyzed blood samples for IL-6 levels. They looked specifically at IL-6 for many reasons. IL-6 is normally low in healthy people and elevated in women with ovarian cancer. This cytokine has been shown to enhance the action of cancer cells by stimulating proliferation, attachment, and migration of these cells. For these reasons, IL-6 has been connected with metastatic disease. In their study, Costanzo and colleagues24 found that high social attachment, indicating that the subject experienced a sense of closeness and intimacy with someone else, was correlated with lower levels of IL-6 (P = .03). And, women with poorer physical well-being (P = .04), poorer functional well-being (P = .02), and greater fatigue (P = .01) had higher levels of IL-6. Ovarian cancer patients with elevated levels of IL-6 have been found to have a poorer prognosis. Thus, this study supports the idea that one way to increase survival is to encourage connection among ovarian cancer patients. Having social connections not only allows ovarian cancer patients to enjoy better physical and functional well-being, but it also increases their bodies’ protective mechanisms against cancer through lowering cytokine IL-6.

Like women, men benefit from social connection when it comes to the diagnosis of cancer. Welin and colleagues25 found that the less people in a man’s house and a low level of social activity in a man’s life were both related to cancer mortality. The study revealed that men living alone or with one other person possessed an increased risk of cancer mortality when compared with men living in households of at least 3 people. Cancer mortality is cut in half when a man increases the number of people living in his household from 2 to 3. The highest cancer mortality (10.6%,) was found in men who participated in 0 to 3 social activities per week. Living with people, interacting socially on a daily basis, and being involved in activities with others are both protective factors for men with regard to cancer.

Connection and Cardiovascular Disease

Many research studies have demonstrated a positive impact of connections on cardiovascular disease. A large prospective cohort study of 734 626 middle-aged women in the United Kingdom was completed by Floud et al.26 They used the Million Women Study via the UK National Breast Screening Program for their study participants. Women filled out self-report questionnaires about marital status and living situations, socioeconomic status, education, and lifestyle factors. In addition, the researchers examined hospital records for first hospital admission for ischemic heart disease as well as death from this disease. The data revealed that women living with a spouse or partner had the same risk of a first coronary event as those women living alone. However, the women living with a spouse or partner had a lower risk of ischemic heart disease mortality than those living along (P < .0001).26 In this study, there were no significant differences in lifestyle factors, socioeconomic factors, or educational factors between the group of women who suffered an ischemic first event and those who did not. This is evidence that for women, living with a spouse or partner confers some type of protection against dying from ischemic heart disease.

There are other connections in a woman’s life apart from her marital status or whether she is living with someone. Researchers have examined the importance of expanded social connections in the heart health of women. In a prospective study of 503 middle-aged women, Rutledge and colleagues27 found that the size of social network was a significant factor in developing risk factors for coronary artery disease such as smoking and hypertension. They used the Social Network Index (SNI; 17) to evaluate social connections. This scale looks at 12 different types of social relationships such as coworkers, friends, spouse, family, and children, and participation in organizations or volunteer activities. By recording the presence or absence of social connections in each of the 12 domains, the SNI reveals information about the diversity of social interactions. It also measures the number of social contacts in each domain. The recording period for the SNI is two weeks. In this study, the researchers performed psychosocial testing, coronary artery disease risk factor assessments, and even quantitative coronary angiography. After following the women for 2.3 years, the researchers concluded that women with high social network scores had a reduced risk of coronary artery disease, including lower blood glucose levels (P = .03), lower smoking rates (P = .002), lower waist-to-hip ratios (P < .01), and lower rates of hypertension (P = .04) and diabetes (P = .004).27 This study also found that increase in social connection was related to a decrease in mortality rates; women with low scores had twice the death rate as women with high scores (P = .03). Rutledge et al27 concluded that every point on the SNI resulted in a 19% decrease in prospective mortality risk over the follow-up period (P = .05). The angiograms revealed that women with high social network scores had lower mean angiogram stenosis values (P < .001). This study points out the importance of a number of varied social connections for women. Of note, in this study, the researchers found that social isolation was associated with lower income levels. This finding highlights the importance of prescribing social connection among at risk populations, such as low socioeconomic status women.

Identifying successful strategies to increase connection in at risk populations is of paramount importance. Coulon and colleagues28 specifically studied underserved African American communities with high levels of chronic disease, poverty, and crime in an effort to find methods to encourage physical activity with the ultimate goal of improving health. In this population, walking programs were most effectively implemented when using social marketing, and participants reported social interaction was the main reason that they participated in the police-patrolled walking programs.28 In this case, social contact was paired with physical activity to create a healthy lifestyle intervention.

It is not only women who benefit from social connections; findings also support a positive relationship between strong social networks and a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease in men. In 1973, a prospective cohort study by Welin and colleagues25 was completed over the course of 12 years with a sample size of almost 1000 men between the ages of 50 and 60 years. Social activities were measured through a verbal questionnaire given by psychologist in which participants were asked about their home activities, outside activities, and social activities as well as their marital status and the number of individuals living in one’s household. It concluded that mortality from cardiovascular disease was correlated with baseline blood pressure (P < .0001), smoking habits (P = .002), and myocardial infarction or stroke (P < .001).25 Although these data are not surprising, a striking statistic from this research is that cardiovascular mortality is also related to a low level of social activities (P = .04). The study was limited to middle-aged men living in Gothenburg, Sweden. However, the data show a strong relationship between cardiovascular mortality and a man’s social network.

Another study on men and social connections completed by Kawachi and colleagues29 further emphasizes the importance of social connection to a man’s cardiovascular health. The authors conducted a 4-year follow-up study in an ongoing cohort of male health care professionals between the ages of 42 and 77 years, including veterinarians, pharmacists, optometrists, osteopathic physicians, and podiatrists.29 Researchers reported that in comparison with men with high social networks, socially isolated men, defined as not married, fewer than 6 friends or relatives, no membership in church or community groups, possessed a high level of risk for cardiovascular death (age-adjusted relative risk, 1.90; 95% CI = 1.07-3.37). In addition, socially isolated men had an elevated risk for stroke (relative risk, 2.21; 95% CI = 1.12-4.35). This study was completed among a highly educated group of men who were aware of health outcomes, which reveals that medical knowledge does not necessarily protect people from the perils of social isolation.

In a recent article on Behavioral Cardiology, Dr Alan Rozanski identifies and defines behaviors that are risk factors for cardiovascular disease.30 He lists 5 main categories: (a) physical health behaviors, (b) negative emotions and mental mind-sets, (c) chronic stress, (d) social isolation and poor social support, and (e) lack of sense of purpose. As described by Rozanski,30 the greater the social support, the less likely is an adverse cardiac outcome for a patient. More and more research is pointing to the importance of social connection for cardiovascular health.

Connection and Psychological Health

Social connection has a significant effect on our mood and our psychological health. There are a number of studies that have researched the effect of socializing in relation to mental health. In fact, the study previously mentioned under connection and cardiovascular health by Kawachi and colleagues29 investigating male health professionals also found that socially isolated men were at increased risk for accidents and suicide. Cruwys and colleagues31 from the United Kingdom completed research examining more than 4000 participants who were respondents in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA). Respondents to the ELSA who were aged 50 years or older, were interviewed in person, and were asked to complete a survey. The survey included questions about depression, group memberships, and other factors, including their age, gender, relationship status, economic status, as well as subjective health status. Specifically, the questions about group membership focused on organizations, clubs, or societies, and individuals had the ability to identify all of the groups that applied to them. There were several specific group memberships included in the questionnaire in diverse categories, including educational, political, religious, political, and social among other classifications. Researchers concluded that not only can group membership be a significant preventive factor in developing depression but it can also be important in attenuating depression symptoms in individuals who are diagnosed with depression. For example, the data revealed that depressed subjects who were not members of any group who joined just one group lowered their risk of a depression relapse by 24%, and depressed subjects who were not members of any group who joined 3 groups lowered their risk of a depression relapse by 63%. While this study included a large sample size, the majority of participants were white, limiting the study. Nevertheless, it does demonstrate the powerful, positive impact of group membership on mood.

A study by Sintonen and colleagues32 in Finland found that the more compact a society is, the better the self-rated mental health is across age groups. This study involved sending a survey to more than 1000 adults between the ages of 55 and 79 years. The survey included questions about social support and mental health, and it was observed that those with more proximate social support felt like they needed less help with their health and they were more capable of taking care of themselves.

Research has demonstrated that group membership is also important in mitigating posttraumatic stress disorder. In a study by Jones et al,33 93 participants admitted to a hospital in England were diagnosed with mild head injuries with no loss of consciousness or moderate head injuries with a loss of consciousness (both placed in the acquired brain injury group) or upper limb injuries with no loss of consciousness (placed in the orthopedic group). The subjects were given questionnaires to fill out at 2 weeks after injury and at 3 months after injury. The questionnaires inquired about general health, maintenance of group membership since injury, development of new group membership since injury, the participants’ sense of belonging, connection, and support associated with group memberships before the injury and after the injury, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and demographics. After evaluating all the data, Jones’s group concluded that after 3 months, having fewer general health symptoms at 2 weeks predicted fewer posttraumatic stress symptoms at 3 months in the group with orthopedic injuries. However, for the acquired brain injury group, forming new group memberships at 2 weeks after the injury was the main predictor of lower levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms at 3 months.33 Specifically, individuals with acquired brain injury who developed new group memberships 2 weeks after being admitted to the hospital reported lower levels of posttraumatic stress symptoms 3 months after being admitted to the hospital (P = .042). This is a call for support group formation for patients admitted to the hospital with acquired brain injury and a recommendation to encourage these patients to become involved with local support groups immediately after discharge.

Posttraumatic stress disorder plagues many people who suffer a wide variety of traumatic experiences including military personnel. Thus, finding a solution to ameliorate the symptoms of this disturbing and life altering disorder is an important goal. Research like that of Jones and colleagues33 reveals that a solution as simple as a support group might well be an effective strategy for this troubling, pervasive problem. In addition, researchers are investigating the use of oxytocin through social bonding and even nasal oxytocin spray to reduce the fight or flight response, the amygdala response, anxiety, distress, and avoidance behaviors experienced by people suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder.34 Connection can act like a medicine for posttraumatic stress patients that allows them to escape the grips of fear and anxiety.

Social Isolation

While the data for positive health outcomes support social interaction, individuals living in the United States are becoming increasingly socially isolated. For example, according to the US Census Bureau report on America’s Families and Living Arrangements in 2012, the average household size declined from 3.1 in 1970 to approximately 2.6 in 2012.35 In addition, this report concluded the proportion of one-person households increased by 10 percentage points between 1970 and 2012, from 17% to 27%. The report makes a correlation between the decrease in family size in addition to the increase in individuals living alone and the decline in the health of the nation.

Social isolation is the opposite of social integration. In a seminal study reviewing the available data on social isolation from 1973 to 1996, Teresa Seeman,36 PhD, defines social isolation as “disengagement from social ties, institutional connections, or community participation.” Dr Seeman reported that both social isolation and unsupportive social interactions can lead to lower immune function, higher neuroendocrine activity, and higher cardiovascular activity. In contrast, socially supportive interactions can do just the opposite.

Almost 20 years later in 2013, a study by Pantell and colleagues37 collected statistics on more than 15 000 adults from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the National Death Index. They used the Social Network Index (SNI) to evaluate social connections. The researchers concluded that socially isolated individuals, both men and women, have an increased risk of mortality. They found that for both men and women being unmarried as well as infrequent participation in religious activities were associated with social isolation. However, for men an additional risk factor for social isolation was lacking club or organization affiliations while in women an additional risk factor for social isolation was infrequent social contact. Pantell and his group concluded that there are some subtle gender differences with respect to social isolation, but the most notable finding is that social isolation for both sexes is just as important as other diagnosed and well-recognized risk factors for mortality, such as hypertension or high cholesterol.

Loneliness is not the same as social isolation. Loneliness is defined as feeling alone and not connected to others, lacking friendship. Loneliness can occur in large groups of people. Like social isolation, loneliness can have a negative impact on health. Research demonstrates the negative effects of loneliness including engaging in addictive and destructive lifestyle behaviors. For example, Stickley and colleagues38 demonstrated that throughout the former Soviet Union, except Kazakhstan and Moldova, loneliness was associated with poor self-related health as well as less healthy behaviors. Specifically, loneliness was connected with risky drinking behaviors in Armenia and Krygyzstan; in Russia, loneliness was associated with drinking as well as hazardous smoking behaviors. Even though this study was completed in the Soviet Union during a time of economic hardship, the research highlights the negative health behaviors that stem from loneliness.

Loneliness has also been associated with depressive symptoms. Cacioppo and colleagues39 performed 2 studies that they published in 1 research report. The first study was a cross-sectional one using a national representative sample of persons age 54 years and older taken from the Health and Retirement Study. The data were gathered by telephone interviews which were part of a study on health and aging. Analysis of the data from the first study demonstrated that an increased level of loneliness was associated with an increased level of depressive symptoms. Although higher education and higher income predict lower depressive symptoms, the relationship between loneliness and depressive symptoms remained significant across socioeconomic statuses. When gender was accounted for, the study found that loneliness and depression had a stronger relationship among men; however, the relationship still exists in women, just to a lesser extent.39

Their second study was a longitudinal analysis. Cacioppo and colleagues39 collected data over a 3-year period gathering information regarding measures of loneliness, social support, perceived stress, hostility, and demographic characteristics from a population-based sample of individuals between the ages of 50 and 67 years. Similar results were found as their first study: an increased level of loneliness led to more depressive symptoms.39 The most striking statistic from this second study was that even when perceived stress, hostility, and social support were included as additional covariates, the analysis of the data demonstrated that loneliness was a powerful predictor of depressive symptoms on its own. Loneliness had a more powerful effect on increasing depressive symptoms than demographic factors, marital status, perceived stress, hostility, and social support had.39 So, not only having social support around you but also feeling connected, not lonely, may be an essential ingredient in the power of social connection.

A Proposed Connection Prescription

The growing body of literature around social connection can lead to new avenues of care for our patients, including inquiring about the quantity and quality of social interactions patients experience in 1 week and crafting a connection prescription from this information. We propose modeling the connection prescription after the exercise prescription which takes into account all the factors of a medication prescription, type of medicine, dose, frequency, and duration. Using the same mnemonic as the exercise prescription, FITT, will help guide the creation of connection prescriptions. What is the frequency (F) or quantity of social interactions? (daily, weekly, or monthly) What is the intensity (I) or quality of social interactions? (Are these close ties, new connections, family interactions, friends that are positive influences or negative influences, are the conversations deep or superficial, is there shared activity, is there a feeling of closeness or connection ?) What is the time (T) or duration of the interaction? (Are these taking 5 minutes, 1 hour, 6 hours?) What type (T) of interaction is this? (Are these volunteer experiences with strangers each week, are these family gatherings, Are these get-togethers with friends, are these group meetings, are these religious services or group exercise classes). Using a familiar template for the connection prescription will allow lifestyle specialists to more readily adopt this tool into their practice and counseling sessions.

The correlation between connection and health is clear. However, further research is needed to comprehend the specifics and the details of the most powerful and healthful connections. At this point, it is safe to say that connecting with friends and family, with whom a person has a good relationship is recommended on a daily or at least once a week basis. This could be a phone call, a Skype call, or a face-to-face interaction. It needs to be an interaction that helps that particular person to feel close to another person. Experiencing a sense of belonging to a group is also beneficial and engaging in group activities once a week or at least once a month is a good place for patients to start. These goals will help patients reach and maintain their health goals. The risks of this type of recommendation are minimal if at all. Ensuring that the people and places with which the patients are connecting are healthy, enjoyable interactions, the only side effects are positive ones such as feeling energized and an improved mood.

Physicians and health care providers often lack time in any given visit to address much more than the presenting complaint. However, with a review of and exposure to the literature on connection and health, providers might be more willing to discuss this important lifestyle topic with patients, especially during an annual visit or a wellness visit. Merely asking about social encounters will be a step in a positive direction. As with exercise as a vital sign, number of social contacts, quantity of social visits in a week, and quality of relationships can be listed on an intake questionnaire as well as put into an electronic medical record. This will indicate to the patient that social connection is something to take seriously and that it is medically important since it is listed with other health-related questions in the doctor’s office. Then, the physician only has to take a quick glance at an added question or two and decide whether to address social connection during the current visit or one in the future. Regardless, simply putting a question about social connection on a medical intake form or questionnaire will send a strong message to patients and physicians alike. This is one small step in the direction of a healthy lifestyle.

In some cases, the physician visit might serve as the person’s weekly or monthly social interaction, and the physician might be an important social connection for the patient, maybe even a “charismatic adult,” someone from whom others gather strength, as Dr Robert Brooks has used the term. The US health care system currently revolves around the gold standard of medicinal therapies, which can be lifesaving in many situations. Lifestyle medicine and specifically connection has the potential to help patients in a different way than medicines and could likely prove to be synergistic with medical therapies. In addition, social connection, like exercise, is a preventative strategy as well as a treatment strategy for chronic conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and depression. It is time to make social connection a part of lifestyle medicine.

Conclusion

From the current body of medical research, it is evident that social connection has substantial impacts in many categories of health from weight management, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and depression. Some psychiatrists go so far as comparing social connection to vitamins: “just as we need vitamin C each day, we also need a dose of the human moment—positive contact with other people.”13 They advocate for adding connection to our list of essentials in addition to food, water, vitamins, and minerals. Thus, like in Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs,” connection distills down to a vital human need. Inquiring about social connection, prescribing it, and using it as treatment as well as prevention, in combination with medicinal therapies in areas where the research supports such practice, could indeed be the social cure for which the United States has been longing

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shavelle RM, Paculdo DR, Strauss DJ, Kush SJ. Smoking habit and mortality: a meta-analysis. J Insur Med. 2008;40:170-178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Critchley JA, Capewell S. Mortality risk reduction associated with smoking cessation in patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;290:86-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Holman CD, English DR, Milne E, Winter MG. Meta-analysis of alcohol and all-cause mortality: a validation of NHMRC recommendations. Med J Aust. 1996;164:141-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fine MJ, Smith MA, Carson CA, et al. Efficacy of pneumococcal vaccination in adults. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2666-2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor RS, Brown A, Ebrahim S, et al. Exercise-based rehabilitation for patients with coronary heart disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2004;116:682-692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I, Ardern CI. Physical inactivity, excess adiposity and premature mortality. Obes Rev. 2003;4:257-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Insua JT, Sacks HS, Lau TS, et al. Drug treatment of hypertension in the elderly: a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:355-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schwartz J. Air pollution and daily mortality: a review and meta analysis. Environ Res. 1994;64:36-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Deci E L, Ryan RM. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gordon I, Vander Wyk BC, Bennett RH, et al. Oxytocin enhances brain function in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:20953-20958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hallowell EM. Connect. New York, NY: Pocket Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dutton JE, Heaphy E. The power of high quality connections. In Cameron KS, Dutton JE, Quinn RE, eds. Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2003:263-278. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;109:186-204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight and obesity. http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/facts.html. Last reviewed April 27, 2012. Accessed August 18, 2015.

- 17. Richmond TK, Milliren C, Walls CE, Kawachi I. School social capital and body mass index in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Sch Health. 2014;84:759-768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Davison KK, Jurkowski JM, Lawson HA. Reframing family-centered obesity prevention using the Family Ecological Model. Public Health Nutr. 2013;16:1861-1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee WJ, Youm Y, Rhee Y, Park YR, Chu SH, Kim HC. Social network characteristics and body mass index in an elderly Korean population. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013;46:336-345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shaya FT, Chirikov VV, Howard D, et al. Effect of social networks intervention in type 2 diabetes: a partial randmoised study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68:326-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thom D, Amireh G, Hessler D, Vore DE, Chen E, Bodenheimer TA. Impact of peer health coaching on glycemic control in low income patients with diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:137-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Engebretson JC, Peterson NE, Frenkel M. Exceptional patients: narratives of connections. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Spiegel D, Kraemer HC, Bloom JR, Gottheil E. Effect of psyschosocial treatment on survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Lancet. 1989;334:888-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Costanzo ES, Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Anderson B, Sorosky J, Lubaroff DM. Psychosocial factors and interleukin-6 among women with advanced ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2005;104:305-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welin L, Larsson B, Svardsudd K, Tibblin B, Gosta T. Social network and activities in relation to mortality from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and other causes: a 12 year follow up of the study of men born in 1913 and 1923. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992;46:127-132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Floud S, Balkwill A, Canoy D, et al. Million Women Study Collaborators. Marital status and ischemic heart disease incidence and mortality in women: a large prospective study. BMC Med. 2014;12:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rutledge T, Reis SE, Olson M, et al. Social networks are associated with lower mortality rates among women with suspected coronary disease: the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:882-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coulon SM, Wilson DK, Griffin S, et al. Formative process evaluation for implementing a social marketing intervention to increase walking among African Americans in the positive action for today’s health trial. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:2315-2321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawachi I, Colditz GA, Ascherio A, et al. A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1996;50:245-251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rozanski A. Behavioral cardiology: current advances and future directions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:100-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cruwys T, Dingle GA, Haslam C, Haslam SA, Jetten J, Morton TA. Social group memberships protect against future depression, alleviate depression symptoms and prevent depression relapse. Soc Sci Med. 2013;98:179-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sintonen S, Pehkonen A. Effect of social networks and well-being on acute care needs. Health Soc Care Community. 2014;22:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones JM, Williams WH, Jetten J, Haslam SA, Harris A, Gleibs IH. The role of psychological symptoms and social group memberships in the development of post-traumatic stress after traumatic injury. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:798-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Olff M. Bonding after trauma: on the role of social support and oxytocin system in traumatic stress. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2012;3:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. US Census Bureau. America’s Families and Living Arrangements: 2012. http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-570.pdf. Issued August 2013. Accessed August 2014.

- 36. Seeman T. Social ties and health: the benefits of social integration. Ann Epidemiol. 1996;6:442-451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N. Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:2056-2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stickley A, Koyanagi A, Roberts B, et al. Loneliness: its correlates and association with health behaviours and outcomes in nine countries of the former Soviet Union. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e67978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging. 2006;21:140-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]