Abstract

Although it is widely recognized that regular physical activity is associated with a variety of health-related benefits in youths, the extent to which vigorous physical activity, as opposed to moderate or light physical activity, may be especially beneficial for youths is not completely understood. This review will examine the evidence for the efficacy of vigorous physical activity for promoting the well-being of youths as indicated by body composition, physical fitness, cardiometabolic biomarkers, and cognitive function. Potential caveats associated with the promotion of vigorous physical activity among youths will also be discussed, as will the inclusion of vigorous physical activity in current recommendations by national organizations for physical activity among youths.

Keywords: children, physical activity intensity, cardiometabolic risk

‘As with adults, PA [physical activity] intensity with children is often categorized as being light, moderate, or vigorous . . . vigorous PA may be especially beneficial for youths.’

It is widely understood that regular physical activity (PA) has many beneficial effects on the well-being of youths.1-3 Less well understood is the precise dose of PA for optimizing these beneficial effects. PA intensity is an important component of PA dose, along with frequency and duration.4 As with adults, PA intensity with children is often categorized as being light, moderate, or vigorous,4 with a number of researchers suggesting that vigorous PA (VPA) may be especially beneficial for youths.5-7 The purpose of this review is to examine the relationship between VPA and the beneficial effects that accrue to youths regularly engaging in VPA. Of particular interest will be studies that reported data on both VPA and moderate intensity physical activity (MPA), given that national recommendations for PA among youths typically address both VPA and MPA.8,9 Since relatively few of the studies that included both VPA and MPA were specifically designed to compare VPA and MPA, issues such as the length of training interventions and volume of VPA and MPA will need to be kept in mind when assessing the relative effects of VPA and MPA on health outcomes.

The review will focus on VPA as related to 4 domains of well-being in youths: body composition, physical fitness, cardiometabolic biomarkers, and cognitive function. Although we will include evidence from cross-sectional and prospective cohort studies, greater weight will, in general, be given to the results of randomized controlled trials. At the same time, during our discussion of VPA and cardiometabolic biomarkers, we will suggest that data from observational studies can contribute in an important way to our understanding of the VPA–cardiometabolic biomarker relationships. We will also discuss the potential hazards associated with VPA in terms of increased injury risk or lessened exercise adherence. Finally, we will examine the extent to which current PA recommendations for youths from national organizations reflect the scientific literature relative to VPA.

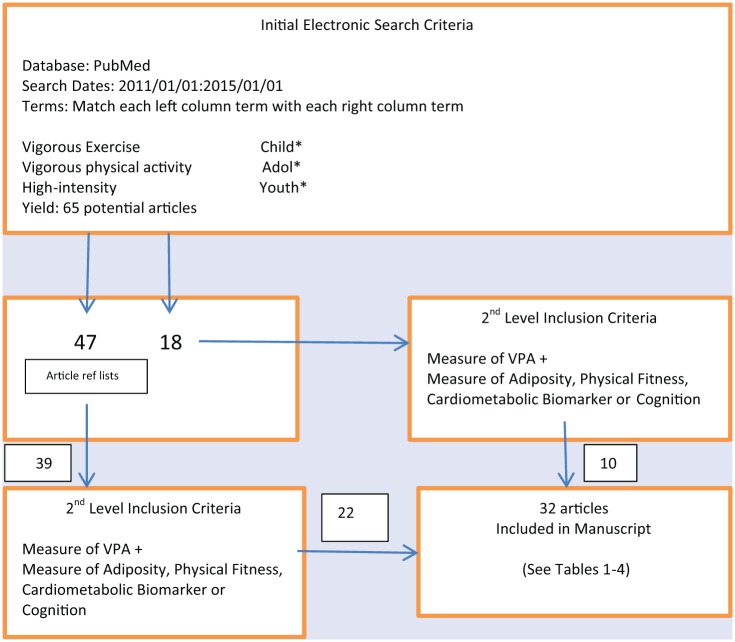

Identification of relevant articles for the current review began with a close reading of the excellent recent review by Parikh and Stratton,6 which also examined the influence of PA intensity on health-related variables in children. From that starting point, we searched the PubMed database from 2011 to 2015 using the keywords shown in Figure 1, which generated an initial pool of 65 potentially relevant articles and associated reference lists. Ten articles from the pool of 65 were eventually included in the review (see Tables 1-4), with the remaining articles being identified by the authors from the article reference lists and their own knowledge base of this topic. Final inclusion of articles was by consensus of the authors.

Figure 1.

Search Strategy for Identification of Relevant Articles.

Table 1.

Body Composition and Vigorous Physical Activity in Youths.

| Study | Age (Years)/Sex | N | Design | Physical Activity Intensity | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hay12 (2012) | 9-17/B&G | 605 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryLTA: 100-1499 cpmMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | WC, BMI z-score | Only VPA associated with reduced WC and BMI z-score |

| Laguna23 (2013) | 8-10/B&G | 439 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 2000-2999 cpmVPA: 3000-4499 cpm | Body fat | VPA better predictor of excess body fat than MPA |

| Sayers24 (2011) | Mean = 15.5/B&G | 1748 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 3600-6199 cpmVPA: >6200 cpm | Fat mass, lean mass, BMC | Only VPA related to fat mass, lean mass and BMC |

| Cohen25 (2014) | 13-18/G | 265 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryMPA: 3000-5200 cpmVPA: >5200 cpm | Body fat | Increased VPA, but not MPA, related to reduced body fat |

| Carson26 (2013) | 915/B&G | 315 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | WC, BMI z-score | Only VPA favorably associated with BMI z-score |

| Racil27 (2013) | Mean = 15.9/G | 34 | RCT | HIIT: 100-110% of max running speedMIIT: 70-80% of max running speed | WC, %BF | %BF decrease greater in HIIT; WC decrease significant in HIIT only |

| Howe29 (2011) | 8-12/B | 106 | RCT | Heart rateVPA: ≥150 bpm | %BF | Exercise HR correlated (P = .02) with decrease in %BF |

| Lau30 (2014) | Mean = 10/B&G | 48 | RCT | HIIT = 120% max running speedLIIT = 100% max running speed | Sum of skinfolds | Greater decrease in skinfolds in HIIT |

| Lee31 (2012) | 12-18/B | 45 | RCT | Resistance training to fatigue or aerobic training at 60-75% of max | Total adiposity, muscle mass | No differences in change in adiposity; muscle mass only increased with resistance training |

| Winther37 (2014) | 15-19/B&G | 1038 | Cross-sectional | 4 categories:SedentaryMPA ≥4× per weekRecreational sports ≥4× per weekHard training = competitive sports several times per week | BMD | Hard training related to greater BMD more than sedentary behavior |

| Sardinha38 (2008) | Mean = 9.7/B&G | 293 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 2001-3999 cpmVPA: >4000 cpm | Femoral neck strength | VPA main predictor of femoral neck strength |

| Weeks39 (2008) | Mean = 13.8/B&G | 99 | RCT | VPA: 10 min of jumping activitiesMPA: 10 min of normal PE warm-up activities | Bone mass | Jumping group gained more bone mass |

| Macdonald40 (2009) | 9-11/B | 202 | RCT | High-intensity vs normal PE activities | Bone strength | High-intensity group gained more bone strength |

Abbreviations: B, boys; G, girls; WC, waist circumference; LTA, light physical activity; MPA, moderate physical activity; VPA, vigorous physical activity; RCT, randomized controlled trial; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; MIIT, moderate-intensity interval training; BMC, bone mineral content; BMD, bone mineral density; %BF, % body fat; BPM, beats per minute; HR, heart rate; LIIT, lower-intensity training; PE, physical education.

Table 2.

Physical Fitness and Vigorous Physical Activity in Youths.

| Study | Age (Years)/Sex | N | Design | Physical Activity Intensity | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hay12 (2012) | 9-17/B&G | 605 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryLTA: 100-1499 cpmMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | Aerobic capacity | Only VPA associated with increased aerobic capacity |

| Moore41 (2013) | Middle school aged/B&G | 258 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 2296-4011 cpmVPA: ≥4012 cpm | Aerobic fitness | VPA strongest predictor of aerobic fitness |

| Carson26 (2013) | 915/B&G | 315 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | Aerobic capacity | Dose–response increase in aerobic capacity for VPA but not MPA |

| Lau30 (2014) | Mean = 10/B&G | 48 | RCT | HIIT = 120% max running speedLIIT = 100% max running speed | Distance covered during endurance test | Distance covered did not differ significantly between HIIT and LIIT |

| Racil27 (2013) | Mean = 15.9/G | 34 | RCT | HIIT: 100-110% of max running speedMIIT: 70-80% of max running speed | VO2peak | No significant differences in change in VO2peak between HIIT and MIIT |

| Buchan14 (2011) | Mean = 16.4/B&G | 47 | RCT | HIIT: repeats of 30-second max sprintsMPA: 20-minute running at 70% VO2max | Aerobic fitness | Increases in aerobic fitness did not differ between HIIT and MPA |

| Corte de Araju42 (2012) | 8-12/B&G | 30 | RCT | HIIT: 60-second sprints at 100% peak running speedMPA: 30-60 minutes continuous exercise at 80% peak HR | Aerobic capacity | Both interventions increased aerobic capacity equally |

| Baquet43 (2010) | Mean = 9.6/B&G | 63 | RCT | HIIT: sprints at 100-190% max running speedMPA: continuous running at 80-85% max running speed | VO2peak | Both interventions increased aerobic capacity equally |

| Tjonna15 (2009) | Mean = 14/B&G | 54 | RCT | HIIT: uphill treadmill training at 90-95% of max HRMultidisciplinary activities: General physical activities | Leg strength 1 RM | Improvements in leg strength did not differ between groups |

| Lee31 (2013) | 12-18/B | 45 | RCT | Resistance training to fatigue or aerobic training at 60-75% of max | Chest and leg strength | Significant increases in strength in resistance training group but not aerobic training group |

Abbreviations: B, boys; G, girls; WC, waist circumference; MPA, moderate physical activity; VPA, vigorous physical activity; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; MIIT, moderate-intensity interval training; HR, heart rate; 1 RM, one repetition maximum.

Table 3.

Cardiometabolic Biomarkers and Vigorous Physical Activity in Youths.

| Study | Age (Years)/Sex | N | Design | Physical Activity Intensity | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andersen45 (2006) | 9-15/B&G | 1732 | Cross-sectional | Accelerometrycpm divided into quintiles | Blood lipids, glucose, insulin | Significant inverse correlations between cpm and total cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose and insulin but not HDL-C |

| Bailey46 (2012) | 10-14/B&G | 100 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 970-2332 cpmVPA: >2333 cpm | Blood lipids, glucose, blood pressure | Neither MPA nor VPA significantly related to blood lipids or glucose; VPA inversely associated with diastolic BP |

| Ekelund47 (2007) | 9-10, 15-16/B&G | 1709 | RCT | AccelerometryMPA: <4000 cpmVPA: >4000 cpm | Blood lipids | VPA not more highly associated than MPA with blood lipids |

| Racil27 (2013) | Mean = 15.9/G | 34 | RCT | HIIT: 100-110% of max running speedMIIT: 70-80% of max running speed | Blood lipids, glucose, insulin | HIIT decreased total cholesterol, LDL-C, glucose and insulin greater than did MPA; no group differences for triglycerides |

| Tjonna15 (2009) | Mean = 14/B&G | 54 | RCT | HIIT: uphill treadmill training at 90-95% of max HRMultidisciplinary activities: general physical activities | Blood lipids, glucose, insulin, endothelial function | Glucose, insulin, and endothelial function more favorable in HIIT group; no group differences for HDL-C or triglycerides |

| Gutin48 (2011) | 8-12/G | 242 | Prospective cohort | VPA: HR > 150 bpm | Blood lipids, glucose, insulin, blood pressure | No significant associations between PA intensity and changes in lipids, glucose, insulin, or blood pressure in the intervention group |

| Ferreira49 (2005) | 13 and 36/B&G | 364 | RCT | Light-to-moderate PA: 4-7 METsVPA: >7 METs | Presence of metabolic syndrome | Decrease in VPA since age 13 related to metabolic syndrome at age 36 |

| Corte ed Araujo42 (2012) | 8-12/B&G | 30 | RCT | HIIT: sprints at 100-190% max running speedMPA: continuous running at 80-85% max running speed | Glucose and insulin | No group differences in changes in glucose and insulin |

| Lee31 (2013) | 12-18/B | 45 | Acute crossover | Resistance training to fatigue or aerobic training at 60-75% of max | Insulin sensitivity | Resistance training, but not aerobic training, associated with improved insulin sensitivity |

| Cockcroft50 (2014) | Mean = 14.2/B | 9 | Prospective cohort | HIIT: 60-second cycling at 90% of max power | Glucose and insulin | No significant group differences |

| MIIT: continuous cycling at 90% of gas exchange threshold | ||||||

| Hay12 (2012) | 9-17/B&G | 605 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryLTA: 100-1499 cpmMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | Systolic blood pressure | Only VPA associated with lowered systolic blood pressure |

| Gaya51 (2009) | 8-17/B&G | 163 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: ≥2000 cpmVPA: ≥3000 cpm | Blood pressure | MPA, but not VPA, inversely associated with systolic BP |

| Carson26 (2013) | 9-15/B&G | 315 | Prospective cohort | AccelerometryMPA: 1500-6499 cpmVPA: >6500 cpm | Blood pressure | Changes in systolic BP not associated with VPA |

| Buchan14 (2011) | Mean = 16.4/B&G | 47 | RCT | HIIT: repeats of 30-second max sprintsMPA: 20-minute running at 70% VO2max | Blood pressure | Systolic BP reduced significantly in HIIT group only |

| Hopkins52 (2009) | Mean = 10.3/B&G | 129 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryQuartiles of PA intensity | Flow-mediated dilation | Impaired flow-mediated dilation associated with low PA level |

| Ried-Larsen53 (2013) | Mean = 15.6/B&G | 336 | Cross-sectional | AccelerometryMPA: 3000-5160 cpmVPA: >5160 cpm | Carotid artery thickness/stiffness | VPA not associated with carotid artery thickness/stiffness |

| Obert54 (2009) | 9-11/B&G | 50 | RCT | HIIT: 25-30 minute running at 100-130% maximal aerobic velocity | LV thickness, mass, shortening | HIIT did not impact LV measures |

Abbreviations: B, boys; G, girls; cpm, counts per minute; RCT, randomized controlled trial; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; MIIT, moderate-intensity interval training; HR, heart rate; LV, left ventricular; BP, blood pressure; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

Table 4.

Cognitive Function and Vigorous Physical Activity in Youths.

| Study | Age (Years)/Sex | N | Design | Physical Activity Intensity | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Etnier55 (2014) | 11-12/B&G | 43 | Cross-sectional | Aerobic fitness test | Memory and verbal learning | A single session of exercise benefits memory and verbal learning |

| Pindus56 (2014) | Mean = 15.4/B&G | 667 | Cross-sectional | MVPA: ≥1963 cpmAerobic fitness test | Cognitive processing speed | Aerobic fitness, but not daily MVPA, was associated with increased cognitive processing speed |

| Coe57 (2006) | 10-13/B&G | 214 | Cross-sectional | From 3-day PA recallMPA: 3-5.99 METsVPA: ≥6 METs | Grades in 4 core classes | Students performing some VPA had higher grades than students performing no VPA |

Abbreviations: B, boys; G, girls; MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity; METs, metabolic equivalents; MPA, moderate intensity physical activity; VPA, vigorous intensity physical activity.

We begin the review with a brief overview of how PA intensity has been expressed in the professional literature.

Expressing Physical Activity Intensity

PA data among youths have been derived from a variety of sources, including self-report questionnaires,10 direct observation,11 assessment of bodily movement using pedometers or accelerometers,12 and by capturing physiologic responses such as heart rate and oxygen consumption during movement activities.13 The duration and frequency components of PA dose can be expressed in a relatively straightforward manner, with duration expressed in some unit of time such as minutes of PA per session, per day, or per week or, in longitudinal studies, as the number of weeks or months of training. Frequency of PA is typically expressed as days per week. Expressing the intensity component of PA is more varied and challenging. Commonly used expressions of PA intensity in youths include percentage of maximal oxygen consumption,14 percentage of maximal heart rate,15 body displacement per unit of time,11 steps per unit of time,16 acceleration counts per unit of time,12 caloric expenditure,7 METs,17 ratings of perceived exertion,18 ground impact forces,19 and, in resistance training scenarios, percentage of one repetition maximum (1 RM).20 In the studies included in this review, PA intensity was most frequently derived from accelerometry and expressed as counts per minute (cpm). A threshold, or cpm cutpoint, was then established to distinguish VPA from MPA. After an extensive review of the accelerometer cutpoint literature, Trost et al21 recommended that researchers utilize the accelerometry cutpoints developed by Evenson et al22 due to their superior overall accuracy and ability to perform well among children of all ages. The Evenson cutpoints categorize accelerometer cpm of between 2296 and 4011 as MPA and cpm ≥4012 as VPA.22 By way of reference, youth activities such as brisk walking (3 mph), dribbling a basketball, and stair climbing would be classified as MPA using the Evenson cpm cutpoints, whereas running at ≥4 mph and doing jumping jacks would be classified as VPA.22 As we proceed through the review, we will identify how VPA was defined in the various studies and, if included, how MPA was distinguished from VPA. We will also comment on the extent to which the varying cutpoints affect our understanding of the role of VPA on the components of well-being presented.

VPA and Body Composition

Three elements of body composition (adiposity, muscle mass, and bone) will be examined here as related to VPA in youths. Relative to VPA and adiposity, we acknowledge the 2011 review by Parikh and Stratton,6 which examined the relevant literature from 1999 to 2009. Our review will expand on their work by including relevant studies published since 2009 and by including information on VPA as related to muscle mass and bone health.

VPA and Adiposity

In their 2011 review, Parikh and Stratton6 concluded that time spent in higher intensities of PA was the most significant predictor of indices of adiposity in youth. Studies published since that review tend to support that conclusion. For example, in a cross-sectional analysis of data from 605 youths aged 9 to 17 years from the Healthy Hearts Prospective Cohort Study, Hay et al12 examined associations between PA intensities and several body composition outcomes including waist circumference and body mass index (BMI) z-score. PA was obtained from 7 days of accelerometry and divided into tertiles of light, moderate, and vigorous intensity based on accelerometer cpm where light PA = 100 to 1499 cpm, moderate PA = 1500 to 6499 cpm, and vigorous PA = >6500 cpm. Only VPA was consistently associated with lower levels of waist circumference and BMI z-score. Achieving more than 7 minutes per day of VPA was associated with a reduced adjusted odds ratio of being overweight. Laguna et al23 cross-sectionally analyzed PA and adiposity data from 439 Spanish youths aged 8 to 10 years participating in the European Youth Heart Study and reported that minutes per day of VPA was a better predictor of risk for excess body fat than was MPA. MPA was defined as 2000 to 2999 cpm, whereas VPA was defined as accelerometer cpm between 3000 and 4499. Thirty-six minutes per day of VPA was identified as the cutpoint for avoiding excess body fat. Sayers et al24 conducted a cross-sectional analysis of 1748 boys and girls (mean age = 15.5 years) participating in the Avon Longitudinal Study and reported that VPA, but not MPA, was inversely related to fat mass as measured by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). MPA was defined as 3600 to 6199 accelerometer cpm and VPA was defined as >6200 cpm.

In a prospective cohort study, Cohen et al25 analyzed PA and body fat data collected during 8th and 10th grade from 265 adolescent girls. MPA was defined as accelerometer counts between 3000 and 5200 cpm, whereas VPA was defined as >5200 cpm. Across the assessment period, increased VPA, but not MPA, was associated with reduced body fat. Every additional minute of increase in VPA was associated with a 0.1% decline in body fat. Carson et al26 prospectively analyzed PA and body composition data across 2 years in a group of 315 youth aged 9 to 15 years at baseline. MPA was defined as accelerometer counts between 1500 and 6499 cpm, while VPA was defined as >6500 cpm. Waist circumference and BMI z-score were the main body composition outcomes of interest. Favorable temporal associations were observed between VPA and waist circumference and BMI z-score. A favorable temporal association was also observed between MPA and waist circumference, but not between MPA and BMI z-score.

While the results of these recent descriptive studies suggest a favorable association between VPA and adiposity in youths, it is also possible that the correlations may not entirely be the result of cause–effect relations but rather reciprocal causation; that is, VPA may cause reduced adiposity, and excess adiposity (perhaps caused by genetics) may cause less VPA. As such, data from controlled interventions help clarify the nature of the VPA–adiposity relationship.

In a controlled intervention, Racil et al27 randomly assigned 34 obese adolescent females to 12 weeks of high-intensity or moderate-intensity interval training or to a nonexercising control group. The high-intensity group trained at 100% to 110% of maximum running speed as determined during a peak VO2 treadmill test, while the moderate-intensity group trained at 70% to 80% of maximal running speed. Interval training sessions were held on 3 nonconsecutive days per week on an outdoor running track. Posttraining decreases in percentage body fat were significantly greater in the high-intensity group than in the moderate-intensity group. Waist circumference decreased significantly only in the high-intensity training group. The authors also noted that the training load was greater in the high-intensity group and this may have contributed to the greater improvements in some variables. On the other hand, it has also been shown that when training volumes were equated, high-intensity interval training appeared to be more effective at reducing body mass.28

Howe et al29 randomized 106 boys aged 8 to 12 years to either a 10-month after school PA program or to a control group that did not attend the after school program. The PA group engaged daily in skills development (25 minutes), VPA (35 minutes), and 20 minutes of strengthening and stretching activities. Participants in the after school program wore heart rate monitors each day and were asked to maintain heart rates of at least 150 bpm during the VPA activities. The heart rate data provided an index of relative intensity for the individual as opposed to an accelerometry cutpoint, which applies the same intensity cutpoint to all children. Amounts of daily MPA and VPA were derived from assessment of 7-day PA recall. A significant correlation was observed between exercise heart rate and decrease in % body fat (r = −.43, P = .02).

Lau et al30 randomized 48 overweight children (mean age = 10 years) to high-intensity running, lower-intensity running, or a nonrunning control group and examined the impact of 6 weeks of intermittent run training on the sum of skinfolds. The high-intensity program involved running at 120% of the individually determined maximal aerobic running speed (determined during an initial intermittent aerobic endurance test), while the lower-intensity program had participants run at 100% of their individual maximal aerobic running speed. The control group did no scheduled training. In the intervention groups, the training consisted of running for 15 seconds at one’s designated percentage of maximal aerobic running speed, followed by a 15-second recovery period. To equate the total distance run per training session, the lower-intensity group completed 16 intervals, for a total of 8 minutes of running, while the high-intensity group completed 12 intervals, for a total of 6 minutes of running. Both intervention groups trained 3 days per week. Following training, the sum of skinfolds decreased significantly more (−12%) in the high-intensity group than in the lower-intensity group (−0.5%) or the control group (+8.0%). The authors also noted the time-efficiency aspect of high-intensity interval training, which involved only 18 minutes per week of actual running, and suggested such training may provide an attractive exercise alternative for youth. Since the distance run per training session was equated in this study, the results provide support for the notion that VPA has unique positive benefits apart from considerations of training volume.

Lee et al31 compared the effects of 3 months of aerobic versus resistance training in a group of 45 obese adolescent boys. The aerobic training group exercised 3 times per week for 60 minutes on treadmills, cycle ergometers, and elliptical trainers at a moderate intensity (60% to 75% of VO2peak). The resistance training group participated in three 60-minute training sessions per week that included a series of 10 whole-body exercises in which they performed 2 sets of each exercise to the point of fatigue. Total adiposity (in kg) decreased significantly and similarly in the 2 groups (aerobic exercise, −3.0 ± 0.8; resistance exercise, −2.5 ± 0.8). Thus, no evidence was provided that the higher intensity of the resistance exercise was especially efficacious compared to the moderate-intensity aerobic exercise.

Based on the available research from cross-sectional, prospective cohort, and controlled intervention studies, a relatively consistent pattern has emerged suggesting that VPA of an aerobic nature provides adiposity-related benefits to youths over and above those obtained from moderate or light aerobic PA. See Table 1 for a summary of these studies. It should be added that the training interventions associated with these studies tended to be relatively short (6-12 weeks). It may be that the benefits of VPA appear more rapidly than those associated with MPA, but with MPA providing comparable benefits over time. Interventions of longer duration will be needed to address this issue. Nonetheless, at least 2 researchers attempted to quantify the adiposity-related advantages of VPA over MPA on a per-minute basis. Based on their cross-sectional data from 251 children 8 to 10 years of age, Wittmeier et al7 reported that 45 minutes of MPA per day were needed to see the same benefits associated with just 15 minutes per day of VPA in terms of reduced body fat and BMI. Steele et al32 reported that 6.5 minutes of daily VPA were associated with a reduction in waist circumference of 1.32 cm, whereas 13.6 minutes of daily MPA were associated with a reduction in waist circumference of only 0.49 cm. In other words, 1 minute of VPA appears to be worth at least 2 to 3 minutes of MPA in terms of body composition benefit.

VPA and Muscle Mass

While most studies addressing issues of body composition in youths focus on measures of adiposity, muscle mass is an important contributor to health risk as well.31 In the study mentioned above by Sayers et al24 involving the cross-sectional analysis of 1748 boys and girls (mean age = 15.5 years) participating in the Avon Longitudinal Study, VPA was positively associated with lean mass (β = 0.038, P = .0001), whereas MPA showed little association with lean mass (β = −0.006, P = .5429). In the study by Lee et al,31 which compared the effects of 3 months of aerobic versus resistance training in 45 obese adolescent boys, total skeletal muscle mass increased significantly in the resistance exercise group but not in the aerobic exercise group. This is consistent with the idea that taking the muscle to momentary failure, which indicates a very high intensity, is especially effective in enhancing muscle mass.

In light of the relatively small number of studies involving muscle mass, it cannot be concluded at this time that VPA is superior to MPA for enhancement of muscle mass among youths.

VPA and Bone Health

Several recent reviews have examined the association between PA and bone health among youths.33-36 Broadly speaking, they concluded that weight-bearing activities during the growing years are effective for promoting bone health. More specifically, it appears that vigorous weight-bearing activities (typically referred to as “high-impact” activities in bone health studies) during youth are more effective for promoting bone health than moderate (“low-impact”) weight-bearing activities. For example, Winther et al37 conducted a population-based survey of more than 1000 Norwegian adolescents to identify predictors that may influence the acquisition of peak bone mass at the femoral neck. Bone mineral density (BMD) was determined using DXA. Questions regarding PA identified type and frequency of PA as well as 4 intensity categories including sedentary, moderate, recreational sports, and hard training. Boys and girls who reported hard training had a 1 standard deviation higher BMD at the femoral neck than did sedentary participants. Using data from the Avon Longitudinal Study, Sayers et al24 reported that day-to-day VPA was positively associated with indices of bone mineral content and geometry in adolescents, whereas light or moderate PA had no detectable associations. The results prompted the authors to suggest that promoting PA during childhood is unlikely to benefit skeletal development unless high-impact activities are increased. Sardinha et al38 cross-sectionally analyzed relationships between accelerometer-derived PA intensity and indices of femoral neck strength in 293 boys and girls (mean age = 9.7 years). MPA was defined as 2001 to 3999 cpm, while VPA was defined as >4000 cpm. VPA emerged as the main PA predictor of femoral neck strength. Daily VPA of at least 25 minutes was associated with better femoral neck bone health in children. In support, Tan et al36 noted that of the 13 observational studies they reviewed regarding associations between organized sports participation and bone strength, all 13 showed a positive association. That is, young athletes had significantly greater bone strength than nonathletes across various measurement sites (proximal femur, tibia, radius, humerus, lumbar spine) and across all maturity groups.

In a controlled, school-based study, Weeks et al39 randomized 99 adolescents to intervention and control groups for 8 weeks. Intervention group participants substituted 10 minutes of jumping activity for normal PE warm-up activities, while the control group maintained normal PE warm-up activities. Jumping activities were designed to apply high strain loads to the skeleton and included jumps, hops, squat-jumps, lunges, and skipping. After 8 weeks, participants in the intervention group gained significantly more bone mass at the femoral neck, trochanter, and calcaneus than the controls. In another controlled, school-based study, Macdonald et al40 randomly assigned 202 boys (aged 9-11 years) to intervention and control groups with the boys in the intervention group participating in a bone loading program not provided to the control group. The bone loading program consisted of 2 components: a “15 × 5” component that included 15 minutes 5 days per week of activities such as skipping, dancing, playground circuits, and resistance exercises with elastic bands and a “Bounce the Bell” component that consisted of a simple jumping activity that required students to perform either counter-movement jumps or side-to-side jumps 3 times per day, 4 days per week. Control participants engaged in normal physical education activities during two 40-minute physical education classes per week. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography showed that the 16-month intervention effectively increased bone strength of the tibia to a greater extent in the intervention group than in the control group. See Table 1 for summary of bone health studies.

As for possible sex differences, Tan et al36 noted in their review that although some adaptations in bone structure and strength related to PA were sex-specific, PA was generally associated with improved bone strength in both boys and girls. It also appears that prepuberty and peripuberty may be the most opportune time for boys and girls to enhance bone strength through PA.33,36 Although the minimum necessary dose of PA to bring about improved bone health among youths is yet to be determined, it was noted that controlled studies that reported positive bone strength outcomes among children implemented weight-bearing PA programs with ground reaction forces 3 to 5 times body weight for a minimum of 7 months, 1 to 12 minutes per session and 2 to 12 sessions per week.36

Although there is less research on PA intensity and bone health than on PA intensity and adiposity, the existing data from cross-sectional studies and controlled interventions consistently point to bone health advantages for youths engaged in high-impact as compared to moderate or low-impact activities.

VPA and Physical Fitness

In this section, we examine VPA and 2 health-related components of physical fitness, that is, aerobic capacity and muscle fitness (muscular strength and muscular endurance). Again, we acknowledge the 2011 review by Parikh and Stratton,6 which examined VPA and aerobic fitness based on the literature between 1999 and 2009. They concluded that although a relationship between aerobic fitness and VPA was evident, it appeared to be less clear than the relationship between VPA and adiposity. Our review will expand on their work by including relevant studies published since 2009 and by including information on VPA and muscle fitness.

VPA and Aerobic Capacity

In their cross-sectional analysis of 605 youth aged 9 to 17 years from the Healthy Hearts Prospective Cohort Study, Hay et al12 found that aerobic capacity increased in a dose–response manner across tertiles of VPA, whereas varying amounts light and moderate PA were not associated with aerobic capacity. The authors also noted that improved aerobic fitness was observed in overweight and obese participants, indicating that VPA can be achieved by this high-risk group. Moore et al41 examined associations between aerobic fitness and sedentary time, MPA, and VPA in a group of 285 middle school students who wore accelerometers for 7 consecutive days. PA cutpoints were 2296 to 4011 cpm for MPA and ≥4012 cpm for VPA. CPM of <100 were classified as sedentary time. Regression analysis indicated that sedentary time and MPA did not contribute meaningfully to aerobic fitness after VPA was included in the model, prompting the authors to suggest that public health messages should stress the promotion of VPA to promote cardiorespiratory health among youth.

In the prospective study by Carson et al,26 mentioned earlier, it was found that follow-up aerobic capacity increased among 315 Canadian youths after 2 years in a dose–response manner across quartiles of VPA, as assessed by accelerometry, but not across quartiles of MPA. The authors suggested the data provide important temporal evidence of the beneficial health outcomes associated with the time youths spend engaging in VPA.

Recent controlled interventions have less consistently shown VPA to be superior to MPA for improving aerobic capacity among youths. For example, in the high-intensity versus lower-intensity running study by Lau et al,30 although 6 weeks of training by participants in the high-intensity group increased the amount of distance covered during the endurance test by 21% compared to the 10% increase experienced by the lower-intensity training group, the percent differences were not statistically significant. In the interval training study by Racil et al,27 mentioned above, both the high-intensity and the moderate-intensity training groups increased VO2peak significantly following 12 weeks of interval training with no significant difference between the groups. Along the same lines, Buchan et al14 reported that both high-intensity interval training and more traditional aerobic training (20 minutes at 70% of VO2max) increased aerobic fitness by approximately the same amount in 47 adolescents following 7 weeks of training. Again, the authors noted the high-intensity group achieved its results with a much shorter time commitment.

In another controlled intervention, Corte de Araujo et al42 randomly assigned 30 obese children to 12 weeks of either high-intensity interval training or continuous endurance training. High-intensity training consisted of 3 to 6 sets of 60-second sprints at 100% of peak running speed interspersed by 3 minutes of active recovery. The endurance training group performed 30- to 60-minute continuous exercise sessions at 80% of peak heart rate. Aerobic capacity was assessed with a maximal treadmill test. Both groups trained 2 days per week. The results indicated that the 2 training methods were equally effective for improving aerobic capacity. Again, the authors noted the high-intensity training involved a substantially smaller (70%) time commitment and that high-intensity exercise was well tolerated by obese children. Baquet et al43 (2010) randomized 63 children (mean age = 9.6 years) to 1 of 3 groups including intermittent run training, continuous run training, or control group. The 2 run training groups trained 3 days per week for 7 weeks. Intermittent training consisted of short sprints at 100% to 190% of maximal running speed as determined during an aerobic fitness treadmill test. Recovery periods of 15 to 30 seconds followed each sprint. Continuous run training involved runs lasting between 6 and 20 minutes at 80% to 85% of maximal running speed. After training, VO2peak was significantly increased by +4.8% in the intermittent run training group and by +7.0% in the continuous run training group with no significant difference between the groups.

The results of the studies in this section indicate that VPA is effective for increasing the aerobic capacity of youths. Cross-sectional and prospective cohort data suggest increases in aerobic capacity are more likely to occur in association with VPA rather than MPA. Recently published randomized controlled trials indicate that VPA is as effective as, but not necessarily superior to, MPA for improving aerobic fitness among youths. VPA appears to have the advantage of time efficiency for achieving aerobic training results, which may be an important consideration where children are involved. See Table 2 for study summaries.

VPA and Muscle Fitness

Research comparing VPA and MPA relative to muscle fitness in youths is much less extensive than research examining differences in aerobic fitness. In a controlled intervention, Tjonna et al15 randomized 54 overweight male and female adolescents to either twice weekly supervised vigorous intensity interval training or a multidisciplinary intervention consisting of exercise, dietary, and psychological advice. The vigorous intensity interval training sessions consisted of 4 segments of walking or running uphill on a treadmill for 4 minutes at 90% to 95% of maximal heart rate followed by 3 minutes of active recovery at 70% of maximum heart rate before proceeding to the next segment. With inclusion of a 10-minute warm-up and 5-minute cool-down period, the total duration of each training session was 40 minutes. Improvements in maximal leg strength (1 RM) were not significantly different between the aerobic interval training group and the multidisciplinary training group. In the study by Lee et al31 that compared the effects of 3 months of aerobic versus resistance training in 45 obese adolescent boys, chest press and leg press strength increased significantly in the resistance exercise group but not in the aerobic exercise group. See Table 2 for study summaries. That resistance exercise can positively affect muscular strength and endurance among youths is widely recognized44 and has prompted national organizations to include resistance training as part of their PA recommendations for youths.8,9 The extent to which VPA more beneficially affects muscle fitness than does MPA apart from resistance training requires additional investigation.

VPA and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers

There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that VPA may be especially important as related to the cardiometabolic profiles of youths.5 In this section, we examine VPA among youths as related to lipid profiles, glucose and insulin, and cardiovascular functions and dimensions.

VPA and Lipid Profile

In a cross-sectional study, Andersen et al45 examined lipid profiles in 1732 boys and girls 9 to 15 years of age who participated in The European Youth Heart Study. Participants wore accelerometers for 4 consecutive days including 2 school days and 2 weekend days. PA was characterized by accelerometer cpm. Small, but significant, inverse correlations were observed between cpm and total cholesterol (TC; r = −.09) and triglycerides (r = −.10) but not for high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C; r = .01). The researchers also calculated a composite cardiometabolic risk factor score for each participant based on systolic blood pressure, triglycerides, TC/HDL-C, insulin resistance, sum of skinfolds, and aerobic fitness. They then assigned participants to quintiles of PA based on cpm. Participants in the highest PA quintile were the only ones to average more than 4000 cpm. Youths in the least active PA quintile were 3.29 times more likely to have a poor composite risk factor score compared to those in the highest PA quintile. Youths in the fourth PA quintile were 2.03 times more likely to have a poor composite risk factor score compared to those in the highest PA quintile.

Bailey et al46 examined PA intensity and cardiometabolic biomarkers in a group of 100 youths aged 10 to 14 years participating in the Health and Physical Activity Promotion in Youth (HAPPY) study. PA was determined from 7 days of accelerometry and classified as moderate (970-2332 cpm) and vigorous (>2333 cpm). Neither MPA nor VPA was significantly associated with blood lipids (triglycerides or TC/HDL ratio). Similarly, Ekelund et al47 did not find VPA to be more highly associated with blood lipid values than was total PA when analyzing data from 1709 participants in European Youth Heart Study. CPM of >4000 was used to distinguish VPA from MPA.

In the controlled intervention study mentioned above, Racil et al27 found that the high-intensity training group decreased TC and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) to a greater extent than did the moderate-intensity training group. Changes in triglycerides were not significantly different between the groups. HDL-C increased significantly following training in both groups, but not significantly more in the high-intensity group. In the controlled intervention by Tjonna et al,15 mentioned above, data on cardiometabolic risk factors were obtained at baseline, 3 months, and 12 months from the vigorous intensity interval training group and the multidisciplinary intervention group. Neither the HDL-C nor triglyceride values differed significantly between the groups at 3 or 12 months, although the vigorous intensity interval training group experienced a significant within-group increase in HDL-C at the end of the 3-month training period compared to baseline.

Gutin et al48 examined changes in lipid profiles (HDL-C, LDL-C, triglycerides) in 242 youths 8 to 12 years of age considered at increased cardiometabolic health risk (ie, black girls). Girls were randomized to a 10-month after school PA intervention or a nonintervention control group. The intervention included 25 minutes of skills development, 35 minutes of VPA, and 20 minutes of toning and stretching. Participants wore heart rate monitors during all activity sessions and were taught how to maintain heart rates above 150 bpm during the 35-minute VPA segment. After 10 months, the intervention led to a significant beneficial effect on LDL-C, but no significant associations between PA intensity and changes in lipids were observed within the intervention group. The authors speculated that the lack of association may have been related to the fact the researchers tried to keep all the children working at a relatively high intensity, which may have limited the variability in heart rate values to such an extent that no significant relationships emerged. In addition, they noted that if, in fact, there is a cause–effect relationship between VPA and some biomarkers, descriptive studies are more likely to show it, for 2 reasons. First, descriptive studies typically have large numbers of subjects, providing substantial statistical power. Second, they may show relationships that have evolved over long periods of variation in PA (eg, months and years). On the other hand, controlled interventions typically have smaller sample sizes and relatively short durations, so the relationships of interest may not have evolved enough to be statistically significant. They add that a meta-analysis might be helpful here.

In summary, although the results are not uniform, the research presented favors the suggestion that increased levels of VPA are associated with improved blood lipid profile, although there are some notable exceptions.46-48

VPA and Glucose-Insulin

Researchers in the European Youth Heart Study found that higher accelerometry derived counts per minute (>4000) of PA were associated with lower levels of blood glucose and insulin.45 On the other hand, Bailey et al46 did not find significant associations between either MPA or VPA and blood glucose levels in the 100 youths involved in the HAPPY study mentioned above. Notably, the cutpoint for VPA in this study was set at a relatively low value of 2333 cpm.

Prospective data from the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study suggest the importance of VPA during youth for future cardiometabolic health in that participants suffering from the metabolic syndrome at age 36, compared with those without the syndrome, showed a marked decrease in the amount of VPA engaged in since age 13.49 VPA was defined as >7 METs, whereas light-to-moderate PA was defined as 4 to 7 METs.

The results of several controlled interventions suggest VPA may be more effective in lowering glucose-insulin levels in youths than lesser PA intensities. In the 3-month exercise intervention by Tjonna et al,15 in which the participants engaged in either twice weekly vigorous-intensity interval training or a multidisciplinary intervention, vigorous interval training induced more favorable regulation of glucose and insulin compared to the less vigorous multidisciplinary intervention.

In their comparison of 12 weeks of high-intensity versus moderate-intensity interval training, Racil et al27 saw no decline in blood glucose in either group, but the high-intensity interval training group experienced a significantly greater decline in insulin than did the moderate-intensity group. Corte de Araujo et al42 reported that changes in insulin and blood glucose were similar in obese adolescents randomized to either 12 weeks of high-intensity interval training (3-6 sets of maximal effort 60-second sprints) or 30 to 60 minutes of continuous endurance exercise at 80% of peak heart rate. Lee et al31 compared the effects of 3 months of aerobic versus resistance training on insulin sensitivity in a group of 45 obese adolescent boys. The aerobic training group exercised 3 times per week for 60 minutes on treadmills, cycle ergometers, and elliptical trainers at a moderate intensity (60% to 75% of VO2peak). The resistance training group participated in three 60-minute training sessions per week that included a series of 10 whole-body exercises, performed 2 sets of each exercise, to the point of fatigue. Resistance exercise, but not aerobic exercise, was associated with significant improvements in insulin sensitivity. In the study mentioned above by Gutin et al48 involving 8- to 12-year-old black girls, no association between PA intensity and blood glucose or insulin was observed after 10 months of training.

Finally, in a brief experimental study, Cockcroft et al50 had 9 adolescent boys complete 2 separate exercise sessions on a cycle ergometer on different days including a high-intensity interval session and a moderate-intensity interval session. The high-intensity session involved 8 repeated bouts of 1 minute of cycling at 90% of maximal power output interspersed with 1.25 minutes of recovery. The moderate-intensity session consisted of continuous cycling at 90% of gas exchange threshold for a duration that matched the mechanical work accomplished during the high-intensity session. An oral glucose tolerance test was performed after each exercise session with the results showing that the high- and moderate-intensity exercise sessions were equally good at lowering postexercise areas under the curve for insulin and glucose. The authors noted, however, that the favorable responses were accomplished in a more time efficient, yet equally enjoyable, manner during the high-intensity sessions (22.8 vs 28.9 minutes), suggesting the shorter time commitment of high-intensity interval training might be considered an attractive alternative to moderate-intensity training.

Although the data are not extensive, a tentative conclusion that VPA is more beneficial than MPA for the glucose-insulin profile of youths seems justified. The large European Youth Heart Study45 and the Amsterdam Growth and Health Study49 provide observational support for that conclusion. In addition, 3 of the 5 controlled interventions mentioned here reported that higher-intensity exercise was associated with improved insulin levels,15,27,31 although only one of those 3 studies reported that glucose was lower in association with VPA.15 See Table 3 for study summaries.

VPA and Cardiovascular Functions and Dimensions

A number of researchers have reported on the associations between VPA and cardiovascular functions and dimensions. Blood pressure has been the function most frequently examined and will be reviewed first, followed by isolated studies reporting on VPA and flow-mediated dilation, carotid artery health, endothelial function, and left ventricular parameters.

In their cross-sectional analysis of data from 605 youth aged 9 to 17 years from the Healthy Hearts Prospective Study, Hay et al12 reported on the associations between PA intensities and systolic blood pressure (SBP). PA was obtained from accelerometry and divided into tertiles of light, moderate, and vigorous intensity. Only VPA was consistently associated with lower levels of SBP. Achieving more than 7 minutes per day of VPA was associated with a reduced adjusted odds ratio for elevated SBP. Bailey et al46 observed a significant inverse association (r = −0.27, P < .05) between VPA and diastolic blood pressure in the 100 youths participating in the HAPPY study mentioned above. MPA was not significantly associated with diastolic blood pressure. On the other hand, Gaya et al51 did not find a significant association between amount of time spend in VPA assessed by accelerometry (>3000 cpm) and systolic blood pressure in a group of 163 adolescent boys and girls who wore accelerometers for at least 4 days. Again, part of the lack of association in this study may have been due the relatively modest cutpoint of 3000 cpm for VPA. Gutin et al48 did not observe a significant association between PA intensity and blood pressure in black girls following a 10-month after school exercise program.

In the 2-year prospective cohort study by Carson et al,26 mentioned above, decreases in systolic blood pressure were observed across quartiles of baseline VPA, but did not reach statistical significance (Ptrend = .06).

In the training study by Buchan et al,14 (2011) mentioned above, SBP was significantly reduced in the group of adolescents exposed to 7 weeks of high-intensity training but not in the group engaging in moderate-intensity training. Thus, relative to blood pressure, the weight of the evidence suggests VPA has a beneficial effect among youths over and above that provided by MPA.

Relative to cardiovascular functions other than blood pressure, Hopkins et al52 examined the relationship between PA intensity and vascular function in 129 children (mean age = 10.3 years) assessed from measurements of flow-mediated dilation (FMD). Brachial artery FMD was expressed as a percent change in arterial diameter (FMD%) and normalized for differences in the eliciting shear rate stimulus between subjects using area under the curve (AUC) data, resulting in an FMD%/SRAUC variable used for analysis. The variable was then split into tertiles from most impaired to least impaired vascular function. PA was determined from 7 days of accelerometry and compared to accelerometer cpm associated with treadmill running speeds obtained during a maximal treadmill test. These data allowed the researchers to determine the number of minutes spent per day by each participant in quartiles of increasing PA intensity. The results showed that significant correlations existed between minutes spent in the 2 upper PA intensity quartiles and impaired vascular function, particularly in those children in the lowest (most impaired) FMD%/SRAUC tertile. No such relationship was observed between PA intensity levels in children in the healthy upper tertiles of vascular function. These finding prompted the authors to suggest that interventions focused on increasing the amount of high-intensity PA may be the most beneficial in improving vascular function in youths at risk of future cardiovascular disease.

Ried-Larsen et al53 did not find that VPA (>5160 cpm) was significantly associated with carotid artery thickness or stiffness in a group of 336 Danish adolescents participating in the European Youth Heart Study who wore accelerometers for 7 consecutive days. The authors noted, however, that the amount of time spent per day in VPA was low and showed little variation, which may have limited statistical power in the analysis.

Tjonna et al15 reported that 3 months of high-intensity (90% of max heart rate) interval training enhanced endothelial functional in adolescents to a greater extent than did 3 months of a multidisciplinary program. Obert et al54 assessed left ventricular health in 50 healthy children 9 to 11 years of age participating in either 2 months of high-intensity training or 2 months of normal activities. The high-intensity training sessions took place 3 times per week and consisted of interval run training for 25 to 30 minutes per session at intensities varying between 100% and 130% of maximal aerobic velocity. Left ventricular wall thickness and mass, as well as shortening fraction, were not affected by training. The authors speculated that prolonged and intensive stimuli may be required to induce significant improvements in diastolic function in healthy young hearts.

The bulk of the research favors the conclusion that VPA has a more favorable impact on cardiovascular dimensions and functions than does PA of lower intensity although, with the exception of blood pressure, only isolated studies exist for most of the variables discussed in this section. See Table 3 for study summaries.

VPA and Cognitive Function

Although research on the effects of acute exercise on cognitive performance among children is relatively limited, it appears that a single bout of exercise, without regard to intensity, can have a transient positive effect on cognitive performance.55 In another study, when compared to less aerobically fit children, aerobically fit children demonstrated greater cognitive processing speed on performance tasks that call for higher order computational processes related to executive control or executive function.56 Daily moderate-to-vigorous PA was not associated with these functions. The extent to which PA intensity affects these results is unclear. Relative to academic achievement, Coe et al57 found that among 214 sixth-grade students greater levels of VPA were associated with higher grades, particularly in students meeting the Healthy People 2010 recommendations for VPA of at least 20 minutes per day at least 3 days per week. Levels of MPA were not associated with higher grades. To be sure, additional research is needed to clarify the exercise intensity–cognitive function relationship among youths. See Table 4 for study summaries.

Caveats Associated With VPA in Youth

Two potential caveats associated with increased VPA in youths relate to possible increased injury risk and lessened exercise adherence.58 Although data on adverse events that result when youths are encouraged to participate in VPA are relatively sparse, the existing research appears to support the notion that VPA is safe. For example, Buchan et al14 examined the effects of a 7-week program of exercise training in adolescent boys and girls randomized to moderate- or high-intensity exercise groups. The high-intensity group engaged in maximal effort sprint interval training 3 days per week, while the moderate training group engaged in 20 minutes of continuous running at 70% of VO2max 3 days per week. No injuries were observed in either group. Kabasakalis et al59 compared continuous endurance swim training sessions with high-intensity interval swim sessions in 14- to 18-year-old male and female swimmers and reported that high-intensity sessions were not detrimental to the redox homeostasis of the swimmers.

Relative to adherence, Corte de Araujo et al42 reported that adherence rates were similar in obese adolescents randomized to 12 weeks of high-intensity interval training (3-6 sets of maximal effort 60-second sprints) or 30 to 60 minutes of continuous endurance exercise at 80% of peak heart rate. In the high-intensity group, 86.9% of the participants completed the program versus 85.5% of the endurance training participants. Murphy et al60 reported that 7 of 9 (78%) obese teens participating in a 4-week high-intensity interval training program completed the training compared to 6 of 8 (75%) obese teens participating in 4 weeks of continuous aerobic training sessions. In a poststudy survey, 6 of the 7 high-intensity exercise participants said they desired to continue with the high-intensity type of training. These results, coupled with the recommendation by Gutin61 that unfit or obese youths gradually build up from lower to higher doses of PA volume and intensity for avoidance of injury and undue fatigue, seem to place calls for increased VPA among youths on solid footing.

VPA in National Activity Guidelines for Youths

Nationally recognized organizations have been publishing PA guidelines for youths for more than 25 years. The American College of Sports Medicine’s first set of youth guidelines, published in 1988, recommended that youths obtain 30 minutes of vigorous exercise each day.62 The current physical activity guidelines from the US Department of Health and Human Services state that children and adolescents should do 60 minutes or more of physical activity daily, most of which should be either moderate- or vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, and should include vigorous-intensity physical activity at least 3 days a week.8 The 2014 position stand from the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology says vigorous-intensity activities and activities that strengthen muscles and bone are recommended at least 3 days per week.9 Clearly, VPA for children is being widely recommended. Unfortunately, it appears that only about 28% of American youth aged 6 to 17 engage in VPA on a daily basis.63 Thus, even though enhancing our understanding of the true nature of the relationship between VPA and well-being among youths is an important goal, addressing the lack of participation in daily VPA by our youth is of equal, if not greater, importance.

Recommendations for Future Research

Answering questions regarding the minimal necessary dose and possible optimal dose of VPA to bring about the health benefits discussed in this review is a major research goal, as is determining whether minimal and optimal doses very across the health benefit in question. The extent to which developmental stage and gender interact with these relationships adds additional levels to the research challenge, as does the need for intervention studies of longer duration comparing VPA and MPA so questions relative to the time course of changes and long-term benefits of VPA compared to MPA can be addressed. While much of the evidence suggesting a beneficial relationship between VPA and health outcomes in youths is observational in nature, it should not be discounted. It has been noted that observational studies often have large numbers of subjects, which provides statistical power, and they may reveal relationships that have evolved over long periods (months or years) of variation in PA.48 Still, the larger goal of establishing cause-and-effect relationships between VPA and health outcomes requires results from additional randomized controlled trials. To date, most of the randomized controlled trials had relatively small numbers of children and relatively short durations. Therefore, firm conclusions await the accumulation of studies in a meta-analysis in order to provide significant power.

Although beyond the scope of this review, another area in need of investigation concerns the physiologic mechanisms underlying the relations between physical activity intensity and various outcome variables. For example, favorable changes in bone might be derived from the direct mechanical stimulation of VPA, whereas favorable changes in cardiometabolic biomarkers may be derived from the metabolic effect of sustained amounts of time spent at lower intensities of physical activity.

Conclusions

This review has examined VPA and MPA from the perspective of which better contributes to selected health outcomes in youths. In general, it appears that engaging in VPA is more advantageous for youths than is MPA, but the strength of the relationship appears to vary with the health outcome under consideration. The results from cross-sectional, prospective cohort, and controlled interventions indicate the case is strong for favoring VPA over MPA relative to adiposity in youths. Relative to muscle mass, the number of relevant studies, especially controlled interventions, is more limited than for adiposity. As such, it cannot be said at this time that VPA is superior to MPA for this component of body composition. Regarding bone health, a strong case can be made in favor VPA over MPA with all study types supporting this conclusion.

Two components of physical fitness were reviewed here, aerobic fitness and muscle fitness. Although VPA has been shown to be an effective strategy for improving the aerobic fitness of youths, most of the current data suggest that MPA is equally effective. At the same time, a number of researchers have noted there is a time-efficiency component that favors VPA over MPA and that this factor may be an important consideration when recommending physical activity for youths. Regarding muscle fitness, although it is widely recognized that resistance exercise can enhance muscle strength and endurance among youths, there are insufficient data to determine whether VPA, apart from resistance training, is more beneficial than MPA for the muscle fitness of youths.

Regarding VPA and cardiometabolic biomarkers among youths, blood lipids and blood pressure have been the most frequently examined. In general, it can be concluded that increased levels of VPA among youths are associated with improved blood lipid profiles. Most of research also indicates a blood pressure benefit for engaging in VPA as opposed to MPA. VPA appears to be more beneficial than MPA for youths in terms of insulin profile, but the data are less clear regarding blood glucose. There is too little published research on other components of cardiovascular function and dimension, such as and flow-mediated dilation, carotid artery health, endothelial function, and left ventricular mass and function to draw conclusions as to the efficacy of VPA over MPA.

The available research on PA intensity and cognitive function among youths is sparse, and no definitive conclusion on the benefits of VPA versus MPA can be drawn. On the other hand, the available data suggest that VPA is safe for children and that it does not appear to lessen adherence to exercise.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Janssen I, Leblanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strong WB, Malina RM, Blimkie CJ, et al. Evidence based physical activity for school-age youth. J Pediatr. 2005;146:732-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Timmons BW, Leblanc AG, Carson V, et al. Systematic review of physical activity and health in the early years (aged 0-4 years). Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2012;37:773-792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014:162-163. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gutin B, Owens S. The influence of physical activity on cardiometabolic biomarkers in youths: a review. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2011;23:169-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parikh T, Stratton G. Influence of intensity of physical activity on adiposity and cardiorespiratory fitness in 5-18 year olds. Sports Med. 2011;41:477-488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wittmeier KD, Mollard RC, Kriellaars DJ. Physical activity intensity and risk of overweight and adiposity in children. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:415-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. US Department of Health and Human Services. 2008. Physical activity guidelines for Americans. http://www.health.gov/PAGuidelines/guidelines/default.aspx. Accessed February 21, 2015.

- 9. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hoelscher DM, Barroso C, Springer A, Castrucci B, Kelder SH. Prevalence of self-reported activity and sedentary behaviors among 4th-, 8th-, and 11th-grade Texas public school children: the school physical activity and nutrition study. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6:535-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Honas JJ, Washburn RA, Smith BK, Greene JL, Cook-Wiens G, Donnelly JE. The System for Observing Fitness Instruction Time (SOFIT) as a measure of energy expenditure during classroom-based physical activity. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2008;20:439-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hay J, Maximova K, Durksen A, et al. Physical activity intensity and cardiometabolic risk in youth. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166:1022-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gutin B, Riggs S, Ferguson M, Owens S. Description and process evaluation of a physical training program for obese children. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1999;70:65-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buchan DS, Ollis S, Thomas NE, et al. Physical activity interventions: effects of duration and intensity. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:e341-e350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tjonna AE, Stolen TO, Bye A, et al. Aerobic interval training reduces cardiovascular risk factors more than a multitreatment approach in overweight adolescents. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009;116:317-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Graser SV, Groves A, Prusak KA, Pennington TR. Pedometer steps-per-minute, moderate intensity, and individual differences in 12- to 14-year-old youth. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8:272-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Owens S, Gutin B, Allison J, et al. Effect of physical training on total and visceral fat in obese children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31:143-148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tompkins CL, Flanagan T, Lavoie J, II, Brock DW. Heart rate and perceived exertion in healthy weight and obese children during a self-selected, physical activity program [published online September 9, 2014]. J Phys Act Health. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2013-0374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tobias JH, Gould V, Brunton L, et al. Physical activity and bone: may the force be with you. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malina RM. Weight training in youth-growth, maturation, and safety: an evidence-based review. Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16:478-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Trost SG, Loprinzi PD, Moore R, Pfeiffer KA. Comparison of accelerometer cut points for predicting activity intensity in youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:1360-1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Evenson KR, Catellier DJ, Gill K, Ondrak KS, McMurray RG. Calibration of two objective measures of physical activity for children. J Sports Sci. 2008;26:1557-1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laguna M, Ruiz JR, Lara MT, Aznar S. Recommended levels of physical activity to avoid adiposity in Spanish children. Pediatr Obes. 2013;8:62-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sayers A, Mattocks C, Deere K, Ness A, Riddoch C, Tobias JH. Habitual levels of vigorous, but not moderate or light, physical activity is positively related to cortical bone mass in adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E793-E802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cohen DA, Ghosh-Dastidar B, Conway TL, et al. Energy balance in adolescent girls: the trial of activity for adolescent girls cohort. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:772-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Carson V, Rinaldi RL, Torrance B, et al. Vigorous physical activity and longitudinal associations with cardiometabolic risk factors in youth. Int J Obes (Lond). 2013;38:16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Racil G, Ben Ounis O, Hammouda O, et al. Effects of high vs. moderate exercise intensity during interval training on lipids and adiponectin levels in obese young females. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2013;113:2531-2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gutin B, Yin Z, Humphries MC, Barbeau P. Relations of moderate and vigorous physical activity to fitness and fatness in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:746-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Howe CA, Harris RA, Gutin B. A 10-month physical activity intervention improves body composition in young black boys. J Obes. 2011;2011:358581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lau PW, Wong del P, Ngo JK, Liang Y, Kim CG, Kim HS. Effects of high-intensity intermittent running exercise in overweight children. Eur J Sport Sci. 2014;15:182-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee S, Bacha F, Hannon T, Kuk JL, Boesch C, Arslanian S. Effects of aerobic versus resistance exercise without caloric restriction on abdominal fat, intrahepatic lipid, and insulin sensitivity in obese adolescent boys: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes. 2012;61:2787-2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Steele RM, van Sluijs EM, Cassidy A, Griffin SJ, Ekelund U. Targeting sedentary time or moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity: independent relations with adiposity in a population-based sample of 10-y-old British children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1185-1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Behringer M, Gruetzner S, McCourt M, Mester J. Effects of weight-bearing activities on bone mineral content and density in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:467-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ishikawa S, Kim Y, Kang M, Morgan DW. Effects of weight-bearing exercise on bone health in girls: a meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2013;43:875-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Janz KF, Thomas DQ, Ford MA, Williams SM. Top 10 research questions related to physical activity and bone health in children and adolescents. Res Q Exerc Sport. 2015;86:5-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tan VP, Macdonald HM, Kim S, et al. Influence of physical activity on bone strength in children and adolescents: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29:2161-2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Winther A, Dennison E, Ahmed LA, et al. The Tromso study: fit futures: a study of Norwegian adolescents’ lifestyle and bone health. Arch Osteoporos. 2014;9:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sardinha LB, Baptista F, Ekelund U. Objectively measured physical activity and bone strength in 9-year-old boys and girls. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e728-e736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weeks BK, Young CM, Beck BR. Eight months of regular in-school jumping improves indices of bone strength in adolescent boys and girls: the POWER PE study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1002-1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Macdonald HM, Cooper DM, McKay HA. Anterior-posterior bending strength at the tibial shaft increases with physical activity in boys: evidence for non-uniform geometric adaptation. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:61-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moore JB, Beets MW, Barr-Anderson DJ, Evenson KR. Sedentary time and vigorous physical activity are independently associated with cardiorespiratory fitness in middle school youth. J Sports Sci. 2013;31:1520-1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Corte de Araujo AC, Roschel H, Picanco AR, et al. Similar health benefits of endurance and high-intensity interval training in obese children. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baquet G, Gamelin FX, Mucci P, Thevenet D, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S. Continuous vs. interval aerobic training in 8- to 11-year-old children. J Strength Cond Res. 2010;24:1381-1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Behringer M, Vom Heede A, Yue Z, Mester J. Effects of resistance training in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2010;126:e1199-e1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Andersen LB, Harro M, Sardinha LB, et al. Physical activity and clustered cardiovascular risk in children: a cross-sectional study (The European Youth Heart Study). Lancet. 2006;368:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bailey DP, Boddy LM, Savory LA, Denton SJ, Kerr CJ. Associations between cardiorespiratory fitness, physical activity and clustered cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents: the HAPPY study. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171:1317-1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ekelund U, Anderssen SA, Froberg K, Sardinha LB, Andersen LB, Brage S. Independent associations of physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness with metabolic risk factors in children: the European youth heart study. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1832-1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gutin B, Harris RA, Howe CA, Johnson MH, Zhu H, Dong Y. Cardiometabolic biomarkers in young black girls: relations to body fatness and aerobic fitness, and effects of a randomized physical activity trial. Int J Pediatr. 2011;2011:219268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ferreira I, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Kemper HC, Stehouwer CD. Development of fatness, fitness, and lifestyle from adolescence to the age of 36 years: determinants of the metabolic syndrome in young adults: the Amsterdam growth and health longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:42-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Cockcroft EJ, Williams CA, Tomlinson OW, et al. High intensity interval exercise is an effective alternative to moderate intensity exercise for improving glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity in adolescent boys [published online October 17, 2014]. J Sci Med Sport. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gaya AR, Alves A, Aires L, Martins CL, Ribeiro JC, Mota J. Association between time spent in sedentary, moderate to vigorous physical activity, body mass index, cardiorespiratory fitness and blood pressure. Ann Hum Biol. 2009;36:379-387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hopkins ND, Stratton G, Tinken TM, et al. Relationships between measures of fitness, physical activity, body composition and vascular function in children. Atherosclerosis. 2009;204:244-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ried-Larsen M, Grontved A, Moller NC, Larsen KT, Froberg K, Andersen LB. Associations between objectively measured physical activity intensity in childhood and measures of subclinical cardiovascular disease in adolescence: prospective observations from the European Youth Heart Study. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1502-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Obert P, Nottin S, Baquet G, Thevenet D, Gamelin FX, Berthoin S. Two months of endurance training does not alter diastolic function evaluated by TDI in 9-11-year-old boys and girls. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:132-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Etnier J, Labban JD, Piepmeier A, Davis ME, Henning DA. Effects of an acute bout of exercise on memory in 6th grade children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2014;26:250-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Pindus DM, Davis RD, Hillman CH, et al. The relationship of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity to cognitive processing in adolescents: findings from the ALSPAC birth cohort [published online October 17, 2014]. Psychol Res. doi: 10.1007/s00426-014-0612-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Coe DP, Pivarnik JM, Womack CJ, Reeves MJ, Malina RM. Effect of physical education and activity levels on academic achievement in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1515-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Longmuir PE, Colley RC, Wherley VA, Tremblay MS. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology position stand: Benefit and risk for promoting childhood physical activity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39:1271-1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kabasakalis A, Tsalis G, Zafrana E, Loupos D, Mougios V. Effects of endurance and high-intensity swimming exercise on the redox status of adolescent male and female swimmers. J Sports Sci. 2014;32:747-756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murphy A, Kist C, Gier AJ, Edwards NM, Gao Z, Siegel RM. The feasibility of high-intensity interval exercise in obese adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2014;54:87-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gutin B. Child obesity can be reduced with vigorous activity rather than restriction of energy intake. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:2193-2196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. American College of Sports Medicine. Opinion statement on physical fitness in children and youth. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1988;20:422-423. [Google Scholar]