Abstract

Counseling patients on behavior change is an important skill that traditional medical training does not emphasize. Most practitioners are trained in the expert approach to handle problems, which is useful in the acute care setting. However, in the case of chronic disease, a coach approach is more effective. This approach allows the patient to reflect on his or her own motivators for change as well as obstacles hindering the change. Changing from the expert approach to the coach approach is contingent on the lifestyle medicine practitioner sharing information when the patient is ready to receive it, listening mindfully, asking open-ended questions, treating problems as opportunities to learn and grow, and encouraging patients to take responsibility for their actions. By collaborating with the patient, the practitioner can guide patients to find solutions to the problems they are facing and foster an environment that leads patients to self-discovery, accepting responsibility for their behaviors, and ultimately, achieving goals that result in healthier daily habits. As a framework and a guide, lifestyle medicine practitioners can use a 5-step cycle of collaboration and a ladder of behavior change when working with patients on behavior change.

Keywords: health coaching, behavior change, lifestyle medicine, coach approach, motivational interviewing

‘The complexity of these lifestyle behaviors warrants consideration for an alternative physician-patient partnership—a “coach” approach.’

Lifestyle behaviors underlie the top 3 causes of death in the United States.1,2 By optimizing physical activity, diet, and weight, and not smoking, approximately 80% of chronic disease (heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes) and 40% of cancer could be prevented.3,4 Centuries ago, Hippocrates said, “If we could give every individual the right amount of nourishment and exercise, not too little and not too much, we would have found the safest way to health.” Decades ago, scientists conducted research, including case studies, longitudinal studies, and randomized controlled trials, that demonstrated that healthy food can reverse atherosclerotic plaque.5-7 Despite this, heart disease is the number one cause of death worldwide,8 and diabetes plagues more than 29 million people.9 The challenge of translating knowledge into action remains.

Physicians play an integral role in promoting health and can be effective champions for patient behavior change.10-13 However, evidence suggests that only 40% of chronic disease visits (e.g., hypertension) involve lifestyle behavior counseling.14 Furthermore, the focus tends to be on short general advice (ie, try to lose weight, limit salt, stop smoking) given in didactic format, rather than a discussion or information sharing from patient to physician and physician to patient.14 This is a missed opportunity to effectively prescribe, arguably the best medicine science has yet discovered—exercise, a whole foods plant-based diet, adequate sleep, social connection, and stress resiliency, all of which are encapsulated in lifestyle medicine.

Behavior change is significantly more complex than merely advising, “Eat less processed foods and exercise more,” and more involved than writing out a detailed prescription for these behaviors. It requires a purposeful interaction and a powerful connection between a lifestyle medicine practitioner and a patient that not only educates but also motivates and empowers the patient to participate in their own planning for a healthy lifestyle. It is this connection and empowerment that lead to sustained behavior change.

The traditional medical model tends to promote an “expert” approach. This expert approach is extremely valuable because it enables physicians to administer life-saving care to patients in acute situations. It gives physicians the autonomy to make complex decisions to provide the best care possible, particularly when the circumstances and implications of various treatment options cannot be fully understood by patients. This dictatorial style is ideal in life-threatening circumstances. However, it is less effective when dealing with lifestyle prescriptions for chronic disease and complex behavior change.

The complexity of these lifestyle behaviors warrants consideration for an alternative physician-patient partnership—a “coach” approach. The coach approach focuses on fostering patient-driven behavior change. It elicits a patient’s motivations, obstacles, strategies, and strengths to help them discover possible ways forward by taking small steps that lead to a healthier life. Physicians use their expertise to identify what behaviors are the most unhealthy, such as smoking, eating fast food, or being sedentary for most of the day. The behavior change process happens as a result of the patient reflecting on his or her health, priorities, purpose, values, and vision and then connecting these to concrete goals that will help them reach their optimal health and wellness. The coach helps a patient figure out how the unhealthy behavior is hindering his or her well-being and guides the patient to select goals that are the most important to him or her. Using the coach approach ultimately creates a situation where the patient has powerful intrinsic motivation. This is accomplished by cocreating an environment that allows for autonomy, competence, and connection, the 3 basic principles of the self-determination theory.15

Coach Approach Background

The coach approach is not what professors in medical schools have been emphasizing or teaching, However, the approach is consistent with what Carl Rogers taught in the 1980s, termed the client-centered approach. Rogers believed in facilitating patients to discover their own internal drivers, preferences, and motivations. Rather than prescriptive, it was conversational and focused on enabling patients to drive the therapeutic process. It takes into account both the client’s agenda to review expectations, feelings, and fears and the practitioner’s agenda to complete a history, physical, and lab work to determine the differential diagnosis, leading to an optimal treatment plan.16,17

The coach approach is based on many different well-researched and effective psychological theories and strategies such as motivational interviewing (MI),18 the Transtheoretical Model of Change,19 Self Determination Theory,15 Goal Setting Theory,20 Hope Theory,21 and the Social Ecological Model of Change.22

Each of these theories and strategies puts the patient in the center—a patient-centered approach. Coaching is often considered a relationship-centered approach because so much of the intervention relies on the coach creating a high-quality connection with the patient.23 For example, the MI spirit is based on 4 principles: (1) collaboration, (2) evocation, (3) autonomy, and (4) compassion.18 The coach aims to hold the MI spirit with each encounter. To meet the patients where they are and provide what they need at that moment in time, the coach needs to use the Transtheoretical Model of Change. This model allows the coach to assess what stage of change the patient is in for that particular behavior: precontemplation, not thinking about change or not willing to change; contemplation, thinking about changing; preparation, planning to change; action, has been practicing the healthy behavior for less than 6 months; or maintenance, has been regularly practicing the healthy behavior for more than 6 months.19 Knowing what stage a patient is in for a specific lifestyle behavior allows the coach to tailor his or her approach. For example, people in precontemplation will be very unlikely respond if the coach works to cocreate a SMART (specific, measurable, action oriented, realistic, and time sensitive) goal because they are not even sure whether they need to or want to change. They are not ready for SMART goals yet. However, a person in the action stage is ready for setting and trying to achieve a new SMART goal.

Self Determination Theory teaches that all people need autonomy, connection, and competence.15 With all 3 of these components, people experience true volitional motivation that sustains them through adversity, fosters creativity, and facilitates optimal performance.15 By involving the patient in the goal creation process, the patient has ownership over the goal and exerts autonomy. Experiencing compassionate communication involving listening, reflecting, and asking open-ended questions feeds the patient’s desire to be heard and understood. This helps form a connection with the coach. Selecting SMART goals that are not only important but also ones that the patient is confident that he or she can complete sets the patient up for success and, thus, engenders a feeling of competence. Success breeds success.

Hope theory, developed by Rick Snyder, PhD, emphasizes the fact that people do well when there is something positive to look forward to or believe in.21 People need to set goals that they believe are possible and useful. This gives them hope that their situation, circumstance, and health can get better if they reach these goals and helps them work hard to complete them. In addition, Snyder taught that people need to use pathways thinking and find multiple routes to that goal. Third, Snyder discussed agency and being a self-advocate. People need to believe that they can achieve.21 As Henry Ford said, “Whether you think you can, or you think you can’t—you’re right.”

Then, the Social Ecological Model of change reminds people that they are not alone.22 The individual usually exists in an immediate family, an extended family, a neighborhood, a community, a state, and a country, and an individual is influenced by the beliefs and attitudes of the people around him or her as well as the social norms and the laws of the land.22

Finally, Seligman and Csujszebtnugaktu24 opened up the world to positive psychology and a strengths-based approach to counseling. This approach encourages people to focus on their strengths and to use those to reach higher levels of life satisfaction.24 Medicine tends to be deficit oriented: find the vitamin deficiency and replace it for scurvy, or find the problem and solve it for chest pain, shortness of breath, fever, or other ailments. For behavior change, the problem is the unhealthy choices people make in the moment, day to day. With a strengths-based approach, the coach shines a light on the patient’s character strengths and calls on them to help the patient move forward toward healthy habits. Instead of stressing what the patient does not have—namely, the deficits—the coach emphasizes the attributes that the patient does have and can use to enhance their well-being. When faced with a problem, it is often important to have multiple possible solutions from which to choose. Discovering possibilities requires creative thinking. Researchers have demonstrated that positive emotions such as appreciation, awe, joy, and pride lead to creativity with Fredrickson’s Broaden and Build Model.25

Coaching involves many different theories. New ones are added as they are developed, refined, and researched, such as Acceptance Commitment Therapy (ACT).26 ACT helps patients manage the negative emotions that they experience by naming them, accepting them, realizing that emotions come and go like a wave (both positive ones and negative ones), and committing to a way forward. “A” stands for accept the current emotions and reactions and be present with them; “C” stands for choose a direction forward in alignment with your values; and “T” stands for take action.26 ACT therapy is not for psychologists or psychiatrists alone. Reading books on the topic, attending workshops, and practicing the 3 main strategies together are ways to become proficient in this effective technique to manage negative emotions.

Does the Coach Approach Work?

There has been a sharp rise in the number of articles published on health and wellness coaching’s effect on a variety of conditions in the medical literature, with approximately 800 abstracts in the research database. There have been randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted for management of many chronic diseases, including asthma, cancer pain, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, increasing physical activity, and weight loss, all of which support the efficacy and validity of health and wellness coaching.27-39 The coach approach has utility in other domains and has also been proposed as a useful adjunct to physiatry and rehabilitation.39 In a recent systematic review of randomized controlled studies that included 13 studies, Kivela et al40 concluded that health coaching resulted in statistically better weight management, increased physical activity, and improved physical and mental health status in patients with chronic disease.

Notable RCTs in health and wellness coaching involving patients with asthma, cancer pain, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes have shown promising results. A RCT involving 191 children with asthma (and parents) resulted in significantly decreased rehospitalization rates compared with controls: 35.6% versus 59.1% (P < .01).27 Another RCT involving 67 cancer pain patients showed that a single face-to-face coaching session for 20 minutes resulted in a significantly reduced average pain severity level at the 2-week follow-up visit as compared with controls (P = .0014).28 A study of 792 cardiac patients who received 3 telephone coaching sessions over a 24-week period showed a cholesterol drop of 21 mg/dL in the coaching group versus 7 mg/dL in the usual care group (P < .0001).30 Studies in patients with diabetes have shown significantly improved diet self-management, less diabetes-related distress, higher satisfaction with care,31 and a reduction in hemoglobin A1C among those with a baseline value ≥7.41

Although there have been a number of studies examining the coach approach with promising results, issues still remain. In the current literature, there is no standard definition of coaching or standardization regarding the training process, coaching practices, or coaching sessions. Standardized measurements have not yet been developed, and there is a need for larger sample sizes as well as more clarity surrounding long-term outcomes. However, the prevailing themes echoed throughout the literature suggest a 1:1 relationship, collaboration/negotiation, goal setting, and accountability as key features of an ideal coaching relationship. With the new National Consortium for Credentialing Health and Wellness Coaches,42 many of these issues will be addressed, and it will be easier to compare coaching studies with each other.43

Switching to a Coach Approach

Focusing on 5 specific domains of communication enables practitioners to successfully switch from the expert approach to the coach approach when they are counseling on lifestyle medicine issues. The 5 domains include sharing knowledge, listening, asking questions, addressing problems, and taking responsibility.

Accumulating and sharing knowledge are valued assets throughout medical school and training. The expert is praised for acquiring and sharing as much information as possible in the classroom and when rounding in the hospital, whereas the coach is tasked with sharing knowledge, but in a judicious fashion; asking for permission; and checking in to see if a patient is ready and willing to hear the new information. This allows recognition of how receptive patients are for more facts, statistics, and advice. Having a fund of knowledge is critical, but being cognizant of how and when to use it is just as important.

Sometimes patients already know a great deal about their medical condition, and simply asking a question such as, “What do you know about how exercise affects blood sugar control?” can really help the practitioner connect with the patient and also save time because if the patient has already heard about exercise from his or her endocrinologist, then reteaching this information is likely to be a waste of time for the practitioner and the patient. The patient can explain what he or she already knows, and then, the practitioner can fill in any gaps. Helping the patient to see the connection between healthy lifestyles and their own personal medical conditions is often a good place to start. Patients are usually receptive to receiving information after they are asked questions such as, “Would you like to hear about how exercise helps prevent cardiovascular disease?” In this way, the patient gives permission to receive the information and is able to express autonomy.

One of the primary ways we gather knowledge is by listening. As ancient Greek philosopher Zeno Citium said, “We have two ears and one mouth, so we should listen more than we say.” Whether it is a peer, an attending, or a patient, we ask questions and hear their stories. The expert tends to rely heavily on cognitive listening, with specific focus on facts and physical signs. By focusing on affective listening and looking for subtleties such as change in tone of voice, facial expressions, body language, and the feelings behind the words (e.g., excitement, anxiety, pride, fear), coaches are able to gather significantly more data points. It is these indirect cues that often serve as windows to the type of interaction a patient needs at that particular time. This allows a much deeper understanding of where patients are and how lifestyle medicine specialists can help patients achieve their goals for healthy habits and, ultimately, their optimal state of health and wellness. Listening carefully is one way to demonstrate care and support. It is essential, in order to form a solid connection between 2 people, that they must listen and understand each other. Also, connection is one of the 3 essential components for motivation according to the self-determination theory: connection, autonomy, and competence.

Part of the listening and communication process is knowing when and how to ask questions; something physicians do not do particularly well. One study estimated that physicians interrupt a patient’s opening statement 77% of the time,44 with another study in medical residents revealing an astonishing 12 seconds of listening occurring before the resident interrupted the patient.45 The expert approach can foster this because physicians are generally looking for key pieces of information via closed ended questions—yes or no questions—that relate to developing a differential diagnosis. It is an essential part of the review of systems and an important part of caring for a sick patient. This is in stark contrast to the coach approach, the predominant focus of which is on asking powerful open-ended questions that seek to uncover core values and intrinsic motivations of patients.

These open-ended questions invite conversation and deep thinking. They prolong the discussion. By definition, an open-ended question cannot be answered by a yes or no. As Voltaire said, “Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.” Asking questions is a key element of effective coaching. Posing powerful questions that lead a patient to self-discovery is a skill that takes practice. It requires that you know the patient well. Entire coaching books exists on the topic of using powerful questions, such as Coaching Questions: A Coach’s Guide to Powerful Asking Skills.46 As part of the Health and Wellness coaching competencies, there are 38 skills to be taught and mastered by coaches, and asking open-ended questions is one of them.42 Asking open-ended questions is also a core skill in MI.

When a problem is identified during questioning, the expert and the coach approaches offer unique ways of addressing the predicament. The expert sees a problem as an opportunity to offer their expert knowledge and use their skills to focus on finding the best solution. It is exciting to find the answers to difficult problems. The Sherlock Holmes approach to the medical mystery thrills many physicians. Finding out what is causing the skin rash, knee pain, or the infection is a challenge, and once it is solved, there is a great feeling of reward and satisfaction, knowing that another patient will be healed. The coach approach views a problem as an opportunity for the patient to learn and grow. It views the patient as the enlightened person, with the solution to the problem. Using the growth mindset put forth by Dweck,47 the patient focuses on what to do differently if the same scenario happens. What did I learn from that setback? How can I use this information to move forward and prevent this from happening again? Instead of looking back at failures as shameful events, excuses not to move forward, or experiences that define the patient, with the growth mindset, failures are guiding lights and beacons that help steer patients in the right direction to make progress toward their goals and vision. Patients are able to take risks and try a new exercise routine or try a new stress reduction technique, knowing that if it does not work or go well, they will learn something valuable and be able to use that knowledge to craft a different path toward healthy habits. Experimenting and trying a variety of whole foods, a different physical activity, and new social opportunities are all part of a healthy lifestyle. In this way, patients are able to take advantage of the most recent evidence-based recommendations and guidelines in lifestyle medicine and become the true masters of their health and their health care.

Finally, the coach approach shifts the responsibility for behavior away from the lifestyle medicine practitioner and toward the patient. This encourages patients to express their autonomy and commitment to adopting healthy behaviors. This empowers the patient. Rather than being trained to find the best answer to every problem, the coach is trained to help patients find the best answer for themselves, guiding and supporting them along the way. By taking on responsibility, patients feel that they are in control. This can be scary, but with a growth mindset and the ability to look at every misstep as an opportunity to further develop and learn, taking responsibility for their own actions is easier for patients. Every patient’s journey is seen as a unique and necessary experience for his or her own growth and advancement.

Implementing the Coach Approach

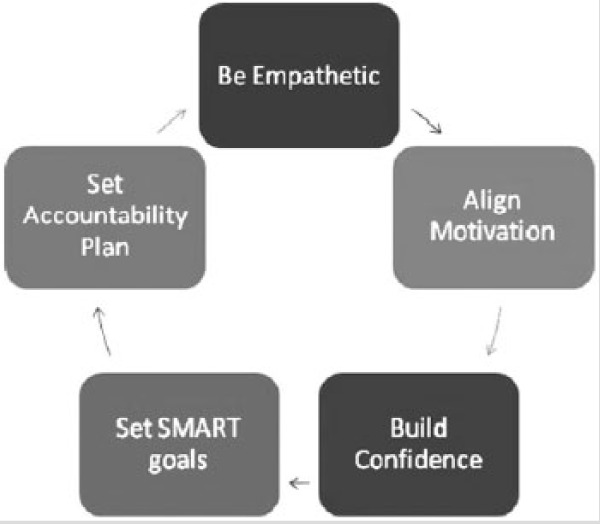

Collaborating with patients involves creating an environment of comfort, creativity, and possibility. Frates et al39 published a 5-step cycle (Figure 1) to accomplish this, which involves: being empathetic, aligning motivation, building confidence, setting SMART goals, and setting an accountability plan.

Figure 1.

Five-Step Cycle in the Coaching Model.a

Abbreviation: SMART, specific, measurable, action oriented, realistic, and time sensitive.

aReprinted with permission from Frates et al.39

Be Empathetic

The American Heritage Dictionary defines empathy as “identification with and understanding of another’s situation, feelings, and motives.”48 Empathy drives the collaborative relationship. Being empathetic allows lifestyle medicine practitioners to build a trusting and caring relationship that enables them to effectively assess patient readiness for change. It helps create a level of understanding about the challenges a patient faces and makes it easier to identify a focus for behavior change. Not only does expressing empathy feel good for both parties involved, but it also helps and heals. Research has shown that high empathy scores in physicians correlate with good control of hemoglobin A1C and low-density cholesterol in their patients.49

Empathy involves trust, respect, support, listening, being nonjudgmental, and being genuinely curious about what a patient has to say. Goleman50 suggests that there are 3 different types of empathy: cognitive, emotional, and empathic need. Cognitive empathy is being able to see things from another’s perspective. It allows one to appreciate how the other person is viewing a particular situation. Emotional empathy is an important type of empathy because it is the basis for building rapport and creating chemistry with a patient. It is the ability to relate to what someone is feeling and understand what someone is going through. The empathic need component consists of the spontaneous drive to offer help. This type of empathy relies on the first 2 to be in place and goes a step beyond. With empathic need, the practitioner is so in tune with the patient that he or she can predict what the patient needs prior to the need being expressed, such as getting out the tissue box before the tears start to flow or resting a hand on a person’s shoulder to provide support and comfort. Empathy is at the core of medicine and something that most clinicians have instinctively. However, not all practitioners are skilled at expressing it with their words or actions. Using reflections after carefully listening to the patient can help a patient feel the empathy that the practitioner is feeling. The best skills to work on when trying to express empathy are listening mindfully and reflecting accurately.

Listening takes energy and effort to do mindfully, meaning being fully present and concentrating on the moment-to-moment happenings unraveling as the person speaks. Whitworth51 has suggested that 3 levels of listening exist: internal, focused, and global. Internal listening is an awareness focused on what the words mean to the listener personally. Focused listening moves beyond the body and mind of the listener, and shifts the emphasis onto the other person who is talking and expressing his or her thoughts, emotions, or concerns. This allows for more open understanding and for a more collaborative relationship. The third level of listening—global listening—involves use of all the senses to better understand the message that is being conveyed by the person speaking. In addition to the verbal cues, nonverbal cues become important, such as body language, facial expression, tone of voice, cadence of speech, volume of speech, and eye contact.51 This constructs a more holistic picture of the emotional environment and fosters a true sense of connection and collaboration for effective coaching to take place. The 3 levels of listening that Whitworth puts forth mirror the 3 levels of empathy that Goleman puts forth, each one getting deeper into the core of the person, so that by level 3 listening and level 3 empathy, there is a real connection between the 2 people in the conversation.

Align Motivation

An empathetic demeanor allows for coordinated efforts to propel a patient forward. Aligning motivation involves discovering a patient’s purpose, priorities, values, and vision of himself or herself in the future. These act as the sides of a ladder, allowing the patient to climb upward one step at a time (Figure 2). The steps are the actions, behaviors, and SMART goals that are in alignment with the patient’s sense of purpose, priorities, values, and vision. The goals and steps need to be in alignment with the person’s mission statement. The motivators propel the patient up the steps of the ladder. The focus is on finding out what the person holds most dear and leveraging this as the driver of change. The Self-Determination Theory enters the coaching equation again at this point by reminding lifestyle medicine practitioners to create conditions that support autonomy, competence, and connection to foster the most volitional and high-quality forms of motivation.15 Extrinsic motivators like rewards, buying new clothes in a smaller size, or losing weight to reduce insurance premiums are often the initial motivators. However, for sustained behavior change, the patient needs to find intrinsic motivation.

Figure 2.

Ladder of Behavior Change.a

aThe sides of the ladder represent the person’s priorities, principles, visions, and values—the framework on which to base his or her SMART (specific, measurable, action oriented, realistic, and time sensitive) goals. The rungs of the ladder are the individual SMART goals, both short and long term, that will lead a person toward his or her ultimate vision or dream. Motivators, both intrinsic and extrinsic, serve as the driving force that propels patients forward along their climb to success.

Intrinsic motivation refers to the desire to experience and appreciate the internal rewards that accompany the targeted behavior. For example, intrinsic motivation could be the feeling of increased energy after a walk or run, increased concentration after a workout, or the sense and comfort of moving with ease as one ambulates throughout the day. Most people experience some type of ambivalence about change. On the one hand, they want to change, and on the other hand, they want to stay the same. These intrapersonal competing interests that exist within a patient can be brought to his or her attention via MI and then resolved collaboratively.18 With MI, the patient is encouraged to do the “change talk” and convince themselves of all the reasons they should change by talking about them out loud. MI has been studied in multiple RCTs and has been shown to be efficacious and moderately more effective than similar interventions.52,53 It has been investigated in various domains, such as weight loss and stroke, and has shown promise in many other areas, including HIV, dental outcomes, alcohol use, tobacco use, and physical inactivity.52-54 Getting to the real root of the patient’s motivation for change helps tremendously. Focusing on motivators in the counseling session takes time and energy, but it is time well spent. Identifying powerful intrinsic motivators often saves time in the future for both the patient and lifestyle medicine practitioner.

Build Confidence

The path to successful behavioral change is filled with challenges; however, no small achievement should go unrecognized. The positive psychology strategy of describing how one succeeded with a goal in the past is a powerful reminder of one’s abilities and helps build confidence. Self-efficacy—belief that one can accomplish the stated task—is thought by some to be a primary determiner of behavior change success and sustained perseverance.55 Promoting patient self-efficacy and autonomy may support creative problem-solving skills and lead to more successes. This is based on Fredrickson’s Broaden-and-Build theory,25 which posits that positive emotions broaden people’s momentary thought-action repertoires, which serves to build enduring personal resources.

In addition, the strengths-based approach to counseling developed by Martin Seligman helps build confidence. Spending time to discover the patient’s individual strengths that he or she uses in everyday interactions and at work is a good way to build confidence. Many people have a hard time recognizing their strengths. By uncovering these signature strengths, the patient can use them to help move forward in behavior change. Often, the characteristics that lead to success in work life or family life are the same ones that can help people reach their health goals. Setting SMART goals and achieving them is another powerful way to build confidence.

Set SMART Goals

In the adult learning theory called andragogy put forth by Knowles,56 adults need to be intricately involved in planning and evaluating issues that have immediate relevance to them. The thought is that adults should experience the accomplishments and setbacks in their journey as the basis for learning new processes or behaviors. By enabling the patient to drive the goal setting process and be the “guinea pig” in their own experiment, additional learning and problem-solving skills can be developed.

Working toward a goal provides a major source of motivation to actually reach the goal, which, in turn, improves performance.20 The selection of goals is critically important too. The goal setting theory put forward by Locke and Latham20 supports creating specific and ambitious goals rather than easy or general goals. Goals that are too easily obtained may not yield enough progress toward the ultimate vision. Conversely, lofty goals may be unobtainable or too challenging in the current circumstances and can lead to frustration and burnout. The coach approach balances these issues by advocating for a collaborative approach that results in a co-developed and built specific, measurable, action-oriented, realistic, and timely (SMART) goal.

A goal that states, “I want to lose twenty pounds,” is not a SMART goal. It is too vague. It is not action oriented. It is not timely. It might be realistic depending on the person and the time frame. It is measurable. To make this into a SMART goal, the lifestyle medicine practitioner and the patient need to do some deeper thinking and questioning. How will the patient lose the weight? What actions will lead to weight loss for the patient? What is the time frame? A SMART goal that could lead to weight loss would read more like the following, “I will exercise 5 days a week for 60 minutes by walking with my husband after dinner on Monday, Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday, and I will eat a piece of fruit for dessert for the next month.” Focusing on the healthy habits and making them be central in the SMART goal will lead to a series of goals that can ultimately steer the patient to improved health and weight loss too. With or without the weight loss, adding these healthy habits into the person’s life will decrease their risk for morbidity and mortality.57

Connecting goals to the priorities and the values in the person’s life is one of the most important steps to cocreating goals. If the goals match, or are consistent with the patient’s sense of purpose, then they are more likely to matter to the patient and, thus, be accomplished by the patient. Research demonstrates that it is important for people to strive to create meaningful experiences for themselves when they are on behavior change journeys such as those leading to weight loss.58 There are a plethora of studies in organizational psychology that emphasize the importance of setting relevant goals that align with a person’s sense of purpose, which will increase productivity and engagement in work and also enhance well-being.59 Lifestyle medicine practitioners strive to cocreate goals that are SMART and aligned with the patient’s sense of purpose in life. Using the previous analogy of the ladder, the goals are the steps, held together and anchored by the patient’s values and vision on one side of the ladder and by their priorities and purpose on the other side of the ladder. The steps—namely, the SMART goals—allow the patient to climb upward toward their optimal level of health and wellness.

After setting a goal, it is important to check on how important that goal is to the patient and how confident the patient is about achieving that goal. A Likert scale is used for this. For example, the practitioner can ask “On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 representing not important and 10 representing extremely important, how important is this goal to you?” For confidence, a similar methodology can be utilized by asking, “On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 representing not confident and 10 representing extremely confident, how confident are you that you can achieve this goal?” If the patient responds with a number >7, then the goal is likely important enough or they are confident enough to achieve the goal. If the number is 7 or lower, it is worth asking a few more questions such as, “What made you say 5 instead of a 2?” This way, the patient will explain why the goal is somewhat important to them. If they respond that they are confident at a level of a 6, then a response might be, “What would it take to change this goal, so that you feel more confident about achieving it?” These are techniques to use to make sure that the goal is a relevant and important one to them and that it is set at the right level of challenge for the patient.

Additionally, Covey’s work60 suggests to begin with the end in mind. The SMART goal approach is effective for daily and weekly goals as well as monthly and yearly goals. Starting with a vision of where the patient wants to go, the ultimate goal, the mission, is an important part of the process. After solidifying this end or vision, then it is essential to find long-term goals (months to a year), and short-term goals (days to weeks) that will lead to realizing the vision set forth.60 This can produce a timeline of checkpoints to reevaluate how things are going to ensure that progress is being made and that modifications can be made as needed along the way.

Perhaps more importantly, these goals need to fit into the context of a patient’s life. The Social Ecological Theory and Model of Change bring environmental social influences on health and disease to the forefront.22 They acknowledge the interplay environmental conditions have with human behavior and recognize the profound effect that society, community, and relationships can have on an individual.22 These additional considerations add complexity to the goal setting process. However, it allows for the creation of an appropriately tailored goal.

Arrange Accountability

In addition to the SMART goals, accountability is needed to ensure that appropriate follow through occurs. Setting goals without setting accountability does not foster sustainable behavior change. When Locke61 wrote about goal setting, he also emphasized the importance of following up on the goal. Whether it is regularly scheduled appointments with the practitioner or health coach or collaboration with a caregiver, spouse, or friend, a system that elicits a sense of responsibility is needed. This could also be self-monitored with a tracking system. Peter Drucker famously said “what get’s measured, gets managed.” Although every goal will be different, there are limitless ways to monitor any behavior change. Patients can use simple logs for number of fruits and vegetables, hours of sleep, push-ups, and minutes of exercise. Technology can be used to monitor heart rate, step count, weight, body fat, blood pressure, or nutrient intake. Qualitative measurements can be discerned with a symptom diary. The methodology is less important than the reinforcement received by experiencing the satisfaction of positive changes.

After checking in with the patient about their goals, the lifestyle medicine practitioner must again use empathy to respond and set the cycle into motion again. No matter what the outcome with the goal, it is important to try to “walk in the patient’s shoes.” Find something that went well and then discuss any obstacles that got in the way of accomplishing a goal. Reinforcing that every misstep is an opportunity to learn and grow is critical for sustained behavior change. With this in mind, the patient and lifestyle medicine practitioner continue to follow the cycle as the patient continues to strive to improve his or her health. This 5-step cycle is evidence based and can serve as a guide for lifestyle medicine practitioners seeking to coach their patients in behavior change.

Clinical Practice Suggestions

Try to make it a point in every patient encounter to address lifestyle issues, even if only briefly. Consider taking lifestyle vital signs (ie, BMI, number of minutes of physical activity per week, number of hours slept, fruit and vegetable intake, smoking history, and alcohol consumption).62 This can help make it easier to prescribe lifestyle medicine as the first line of treatment for many chronic diseases.63,64 Robert Sallis65 created a series of suggestions for the Exercise is Medicine initiative for visit- and time-specific exercise prescription suggestions. Similarly, below are some specific examples to consider that pertain to any behavior change, depending on the amount of time allotted in a particular patient visit.

30 Seconds

A brief interaction can be an opportune time for a clinician to express how important lifestyle issues are with regard to health. It also provides an opportunity to schedule dedicated time in a follow-up visit. Lifestyle medicine practitioners can take advantage of a prevention visit, which is covered by Medicare. Discussing one’s own personal health behaviors may also be an effective approach.66 Frank et al66 showed that physicians who conveyed their own healthy habits enhanced their ability to motivate patients. This study also utilized nonverbal cues, including intentional placement of an apple on the physician’s desk and the physician wearing a bike helmet.66 The main goal in the 30-second interaction is to make a connection and keep the door open for further discussions in the future. A simple reflection expressing that the lifestyle medicine practitioner understands the patient by saying, “I hear you saying that you want to start exercising, but you just cannot find the time,” can help the patient feel heard and understood, which could allow further discussion and brainstorming at the next visit. Reinforcing the importance of exercise for optimal health can be done in an open and nonjudgmental way such as, “Medical research and my clinical experience have informed me about how exercise can reduce high blood pressure. Regular exercise and a healthy diet can help avoid heart attacks and strokes. When you are ready to discuss this further and work on an action plan to get moving, I am here for you.”

5 Minutes

Inquire about what lifestyle-related areas a patient is currently concerned about and which one they are ready to address: exercise, healthy eating, sleep, stress management, smoking cessation, controlling drinking, or social connection. Ask the patient what he or she is doing now in these areas. Find out about what specific steps he or she could take and then develop a brief, “one small step,” action plan with them. Once a plan is agreed on, check a patient’s confidence level by asking how confident they are on a 1 to 10 scale (1 being not confident at all, 10 being completely sure). Consider follow up questions such as, “I see you marked ‘5’; what made you mark ‘5’ instead of ‘2’?” to further evoke a patient’s positive affirmation of their self-efficacy and ability to change. As reviewed previously, this type of MI counseling with confidence and importance scales encourages the patient to convince himself or herself of the ability to change and the need for change rather than the lifestyle medicine practitioner telling the patient what to do and stripping the patient of his or her autonomy. If a patient is not ready for an action plan, offer a brief message appropriate to the patient’s stage of readiness.62 Be sure to ask open-ended questions and find a focus for the next visit.

10 Minutes

Additional time allows a provider to take a deep dive into an area or two of concern that the patient is ready and willing to address. This is where the collaboration cycle can be utilized. The process should start by assessing the stage of change for the patient’s particular area of focus. Depending on the stage, one should consider the following questions: What/who do you value in your life? What is most important to you? What do you feel your life’s purpose is? How do you envision your future self in 5 or 10 years? Where are you now in relation to how you see yourself? What small step could you take now/this week to get slightly closer to this goal/vision? How will this step help you achieve your goals? What is motivating you to make this change? What obstacles are in your way? What strengths do you have that you can use to help you get around these barriers? What solutions have you considered that you think will work for you? The ultimate goal of the session is to connect the behavior change to the patient’s core values and life purpose. This is not meant to be a 10-minute lecture, rather more of a brainstorming, cocreating session. Once the patient can articulate and envision where they want to go, MI techniques can elicit “change talk” from a patient. After they express genuine motivation to change, a SMART goal can be set and follow-up visit/times can be agreed on. This process seeks to evoke a patient’s intrinsic motivation and leverage this as the driver of change.

30 Minutes

This is a good amount of time to implement the entire 5-step cycle. Similar to the previous examples, empathy is the foundation and common thread woven throughout the visit. Letting the patient talk and tell their story is an essential part of knowing the patient well and being able to provide what the patient needs at that moment, at that stage of change. Understanding the patient enables motivation alignment toward a common goal. As described above, MI with reflections, affirmations, and open-ended questions supporting a patient’s self-efficacy will build the confidence a patient needs to pursue their behavior change plan. Investing the time to explore a patient’s strengths, weaknesses, preferences, and values is critically important. The priorities, principles, values, and vision provide the backbone in the ladder of the behavior change framework (Figure 2), with SMART goals acting as the rungs and motivators (both intrinsic and extrinsic) as the forces moving people closer to their dreams. The importance of asking open-ended questions in an exploratory, nonjudgmental, and inquisitive fashion cannot be overstated. This is what builds a collaborative, trusting relationship. The ambivalence that a patient exhibits surrounding a particular behavior can be gently swayed toward a motivation and a desire to make a healthy change. By collaborating with the patient, the patient can find his or her own internal source of motivation and share it out loud with the lifestyle medicine practitioner. This process will naturally lead to a patient wanting to take a step toward change and to cocreate a SMART goal that is important to them. The clinician serves to reflect what the patient is saying to guide and facilitate the development of an appropriate SMART goal. The empathic exchange fosters a sense of possibility and hope. Involving the patient and asking them to lead the way transfers responsibility to the patient. Knowing that the lifestyle medicine practitioner is supporting the patient and will check up on the patient’s progress provides the accountability that can help propel patients to make lasting changes to improve their health and, ultimately, their lives.

Personal Practices of Lifestyle Medicine Practitioners

Making healthy lifestyle changes for patients and providers alike is a challenging task that takes significant time. With busy offices, packed schedules, and a never-ending supply of emails, most physicians have room for improvement in the area of counseling for behavior change as well as practicing their own behavior change. Interestingly, physician health habits may affect patient’s habits. Research has shown that physicians who practice healthy habits are more inclined to counsel patients about these same habits.67-69 Perhaps in this ever-spinning world, with always more work and more deadlines, and less and less time, lifestyle medicine practitioners can start by taking some of their own advice. It might make sense for practitioners to take 5, 10, or even 30 minutes to sit down and make their own behavior change ladder looking at their own vision and values on the one hand and priorities and purpose on the other. Then, they can consider their own intrinsic motivation, use of a growth mindset, feeling of connection, feeling of autonomy, feeling of competence, feeling of hope, and system setup for accountability for a healthy habit goal that they themselves want to pursue. After this, the practitioners can craft their own SMART step and start creating the rungs on their own ladder to lasting behavior change (Figure 2). In the words of Mahatma Gandhi, “Be the Change that you wish to see in the world,” and John Lewis, “If not us, then who? If not now, then when?”

Conclusion

Chronic diseases are largely influenced by modifiable lifestyle behaviors. The coach approach of collaboration and negotiation offers significant benefits, as compared with the traditional expert approach, for promoting lifestyle medicine and fostering lasting behavior change in patients. Although some new skills are needed to master the approach, there are simple ways to begin incorporating this coach approach into clinical practice immediately. Further research is needed to specify the ideal training formats and implementation strategies needed for increased adoption of this approach in the current medical training model. However, a step in the direction of tackling the worldwide obesity and diabetes epidemic may be for lifestyle medicine practitioners to use the 5-step collaboration with patients when counseling on behavior change and to help patients create their own behavior change ladders.

Acknowledgments

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Footnotes

These articles are based on The Annual Conference of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) held November 1-4, 2015, in Nashville, Tennessee—Lifestyle Medicine 2015: Integrating Evidence into Practice.

References

- 1. Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238-1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McGinnis J, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2207-2212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kroger J, Schienkiewitz A, Weikert C, Boeing H. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition—Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1355-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organization. Preventing Chronic Disease: A Vital Investment. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. http://www.who.int/chp/chronic_disease_report/full_report.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esselstyn CB, Jr, Gendy G, Doyle J, Golubic M, Roizen MF. A way to reverse CAD? J Fam Pract. 2014;63:356b-364b. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Esselstyn CB, Jr, Ellis SG, Medendorp SV, Crowe TD. A strategy to arrest and reverse coronary artery disease: a 5-year longitudinal study of a single physician’s practice. J Fam Pract. 1995;41:560-568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ornish D, Scherwitz L, Billings W, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1998;280:2001-2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy SL, Xu JQ, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1-117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health & Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Douglas F, Torrance N, van Teijlingen E, Meloni S, Kerr A. Primary care staff’s views and experiences related to routinely advising patients about physical activity: a questionnaire survey. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eakin EG, Glasgow RE, Riley KM. Review of primary care-based physical activity intervention studies: effectiveness and implications for practice and future research. J Fam Pract. 2000;48:158-168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kreuter MW, Chheda SG, Bull FC. How does physician advice influence patient behavior? Evidence for a priming effect. Arch Fam Med. 2000;5:426-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feenstra TL, Hamberg-van Reenen HH, Hoogenveen RT, Rutten-van Mölken MP. Cost-effectiveness of face-to-face smoking cessation interventions: a dynamic modeling study. Value Health. 2005;8:178-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Milder IE, Blokstra A, de Groot J, van Dulmen S, Bemelmans WJ. Lifestyle counseling in hypertension-related visits: analysis of videotaped general practice visits. BMC Fam Pract. 2008;9:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Deci EL, Ryan RM. Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: an overview of self-determination theory. In: Ryan RM, ed. Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2012:85-107. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rogers CR. Significant aspects of client-centered therapy. Am Psychol. 1946;1:415-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rogers CR. Client-centered therapy: a current view. In Fromm-Reichmann F, Moreno JL, eds. Progress in Psychotherapy. New York, NY: Grune & Stratton; 1956:199-209. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rollnick S, Miller WR. What is motivational interviewing? Behav Cogn Psychother. 1995;23:325-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Prochaska JO, Norcross JC, Diclemente CC. Changing for Good: A Revolutionary Six-Stage Program for Overcoming Bad Habits and Moving Your Life Positively Forward. New York, NY: HarperCollins; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Locke EA, Latham GP. Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: a 35-year odyssey. Am Psychol. 2002;57:705-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Snyder CR, Rand KL, Sigmon DR. Hope theory: a member of the positive psychology family. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of Positive Psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002:257-276. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence: a global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, eds. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002:1-56. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dutton JE, Heaphy E. The power of high quality connections. In: Cameron K, Dutton JE, Quinn RE, eds. Positive Organizational Scholarship. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler; 2003:263-278. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Seligman MEPM, Csujszebtnugaktu N. Positive psychology: an introduction. Am Psychol. 2000;55:5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56:218-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hooper N, Larsson A. The Research Journey of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fisher EB, Strunk RC, Highstein GR, et al. A randomized controlled evaluation of the effect of community health workers on hospitalization for asthma: the asthma coach. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:225-232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oliver JW, Kravitz RL, Kaplan SH, Meyers FJ. Individualized patient education and coaching to improve pain control among cancer outpatients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2206-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Edelman D, Oddone EZ, Liebowitz RS, et al. A multidimensional integrative medicine intervention to improve cardiovascular risk. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:728-734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vale MJ, Jelinek MV, Best JD, et al. Coaching patients on achieving cardiovascular health (COACH): a multicenter randomized trial in patients with coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2775-2783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whittemore R, Melkus GD, Sullivan A, Grey M. A nurse-coaching intervention for women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2004;30:795-804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sacco W, Morrison AD, Malone JI. A brief, regular, proactive telephone “coaching” intervention for diabetes: rationale, description, and preliminary results. J Diabetes Complications. 2004;18:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Koenigsberg MA, Bartlett D, Cramer JS. Facilitating treatment adherence with lifestyle changes in diabetes. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:309-316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Debar LL, Ritenbaugh C, Aickin M, et al. A health plan-based lifestyle intervention increases bone mineral density in adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1269-1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Holland SK, Greenberg J, Tidwell L, Malone J, Mullan J, Newcomer R. Community-based health coaching, exercise, and health service utilization. J Aging Health. 2005;17:697-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tidwell L, Holland SK, Greenberg J, Malone J, Mullan J, Newcomer R. Community-based nurse health coaching and its effect on fitness participation. Lippincotts Case Manag. 2004;9:267-279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Heimendinger J, Uyeki T, Andhara A. Coaching process outcomes of a family visit nutrition and physical activity intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2007;34:71-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tucker LA, Cook AJ, Nokes NR, Adams TB. Telephone-based diet and exercise coaching and a weight-loss supplement result in weight and fat loss in 120 men and women. Am J Health Promot. 2008;23:121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Frates EP, Moore MA, Lopez CN, McMahon GT. Coaching for behavior change in physiatry. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:1074-1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kivela K, Elo S, Kynga H, Kääriäinen M. The effects of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;92:147-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wolever RQ, Dreusicke M, Fikkan J, et al. Integrative health coaching for patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010;36:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jordan M, Wolever RQ, Lawson K, Moore M. National training and education standards for health and wellness coaching: the path to national certification. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015;4(3):46-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mittelman M. Health coaching: an update on the national consortium for credentialing of health and wellness coaches. Glob Adv Health Med. 2015;4(1):68-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Beckman HB, Frankel RM. The effect of physician behavior on the collection of data. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:692-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rhoades DR, McFarland KF, Finch WH, Johnson AO. Speaking and interruptions during primary care office visits. Fam Med. 2001;33:528-532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Stoltzfus T. Coaching Questions: A Coach’s Guide to Powerful Asking Skills. Virginia Beach, VA: Coach22; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Dweck C. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. New York, NY: Random House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 48. “Empathy.” The American Heritage Dictionary. 2nd ed 1991. p. 449. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86:359-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Goleman D. The Brain and Emotional Intelligence: New Insights. Northampton, MA: More Than Sound; 2011:61. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Whitworth L. Co-Active Coaching: New Skills for Coaching People Toward Success in Work and Life. 2nd ed Mountain View, CA: Davies-Black; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Watkins CL, Wathan JV, Leathley MJ, et al. The 12-month effects of early motivational interviewing after acute stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2011;42:1956-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pollack KI, Alexander SC, Coffman CJ, et al. Physician communication techniques and weight loss in adults: project CHAT. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:321-328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1994:71-81 (reprinted in Friedman H, ed. Encyclopedia of Mental Health San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 56. Knowles MS. The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species. 4th ed Houston, TX: Gulf Publishing; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Matheson EM, King DE, Everett CJ. Healthy lifestyle habits and mortality in overweight and obese individuals. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Silva MN, Markland D, Carraca EV, et al. Exercise autonomous motivation predicts 3-yr weight loss in women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:728-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Berg JL. The role of personal purpose and personal goals in symbiotic visions. Front Psychol. 2015;6:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Covey SR. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Restoring the Character Ethic. Rev ed New York, NY: Free Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Locke EA. Motivation through conscious goal setting. Appl Prev Psychol. 1996;5:117-124. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Liana L, Johnson M. Physician competencies for prescribing lifestyle medicine. JAMA. 2010;304:202-203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes: 2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(suppl 1):S11-S61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sallis R. Exercise is medicine: a call to action for physicians to assess and prescribe exercise. Phys Sportsmed. 2015;43:22-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Frank E, Breyan J, Elon L. Physician disclosure of healthy personal behaviors improves credibility and ability to motivate. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:287-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Abramson S, Stein J, Schaufele M, Frates E, Rogan S. Personal exercise habits and counseling practices of primary care physicians: a national survey. Clin J Sport Med. 2000;10:40-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Oberg EG, Frank E. Physicians’ health practices strongly influence patient health practices. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2009;39:290-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wells KB, Lewis CE, Leake B, Ware JE., Jr. Do physicians preach what they practice? A study of physician’s health habits and counseling practices. JAMA. 1984;252:2846-2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]