Abstract

Introduction:

Aspects of self-stigma and medication-related stigma among individuals with depressive disorders remain largely unexplored. The primary objective of this study is to highlight and characterize self-stigma and medication-related stigma experiences of antidepressant users.

Methods:

This is a secondary analysis of data obtained from PhotoVoice studies examining psychotropic medication experiences. Transcripts of reflections from 12 individuals self-reporting a depressive disorder diagnosis and receipt of a prescription for an antidepressant were included. A directed content analysis approach based on expansion of the Self-Stigma of Depression Scale and an iterative process of identification of medication-stigma and stigma-resistance were used. Total mentions of self-stigma, stigma resistance, medication stigma, and underlying themes were tallied and evaluated.

Results:

Self-stigma was mentioned a total of 100 times with at least 2 mentions per participant. Self-blame was the most prominent construct of self-stigma and was mentioned nearly twice as often as any other self-stigma construct. Most participants also made mentions of self-stigma resistance. Half of the individual participants mentioned stigma resistance more times than they mentioned self-stigma, which suggests some surmounting of self-stigma. Medication-related stigma was also prominent, denoting negativity about the presence of medications in one's life.

Discussion:

Self-stigma related to self-blame may be problematic for antidepressant users. Identification and measurement of stigma resistance, especially in peer interactions, may represent a promising concept in overcoming self-stigma. Future work should explore emphasizing self-blame aspects when designing interventions to reduce self-stigma among individuals with depressive disorders and explore development of tools to measure stigma resistance.

Keywords: self-stigma, PhotoVoice, stigma perceptions, stigma resistance, antidepressant users

Introduction

Stigma can be described as a perceived condition that deviates from what someone would consider normal, linked with attributes that would produce a negative image of the stigmatized person, spoiling one's identity.1 Stigma can be classified into 2 categories: perceived/public stigma and self-stigma. Perceived stigma is the negative attitude the public would have about an individual (eg, a person with mental illness). Self-stigma occurs when negative attitudes or stereotypes about an illness are accepted and incorporated into the identity of people who have been diagnosed with the illness.2 Presence of self-stigma in individuals with mental illness can have significant impacts on their quality of life and isolation from social interactions.3,4 Self-stigma is associated with poor medication adherence in individuals with various mental health conditions, including depression.5-7 Kamaradova and colleagues5 showed that severity of mental illness–related self-stigma was directly correlated to medication nonadherence. Several interventions have been recently developed to attempt to reduce self-stigma in individuals with mental illness.8 These have shown small-to-moderate reductions, suggesting more research is needed into the nature of self-stigma as well as alternative methods of self-stigma reduction.9

Medication stigma may also be prevalent in individuals with mental illness and may be associated with self-stigma.10 However, little has been written about the nature and impacts of medication-related stigma. Less is also known about self-stigma that is specific to depression or antidepressants as compared with schizophrenia and its treatments.11 Previous research has indicated that explicit, self-report measures of self-stigma may not capture the full nature of the phenomenon because much of self-stigma appears to be implicit. Individuals with mental illness may not be able or willing to disclose self-stigma in self-report measures and/or may not be aware of their own self-stigma on a conscious level.12 Therefore, alternative methods to understand self-stigma have been encouraged. In a recent series of participatory action studies exploring mental illness medication experience, researchers noted that participants often made statements alluding to mental illness–related or medication-related stigma.13,14 Because self-stigma is theoretically ingrained in an individual's self-concept, it stands to reason that aspects of self-stigma will manifest in conversation even when the individual is not being directly asked about it. Hence, the researchers performed a content analysis of existing data to explore stigma discussions further in an attempt to understand the nature of depression-related self-stigma and medication-related stigma that emerged.

Methods

Transcripts of individual interviews from a series of participatory-action research studies13,14 employing the use of PhotoVoice methodology were used as the data set for the current study. PhotoVoice is a participatory action method that equips participants with disposable cameras in order to capture their lived experiences that can be shared with others to enable communication, education, and advocacy.15 The goal of the PhotoVoice approach is to make the lived experience of a participant tangible to others. The original study recruited participants who self-reported a mental illness diagnosis as well as receipt of a prescription for 1 or more psychotropic medications. Participants took photographs of their lived experience of psychotropic medication and reflected upon each photo using the SHOWED technique, an open-ended questioning reflection approach.16 Reflections were audio-recorded and transcribed. The participants, while describing and discussing their medication experience, placed considerable emphasis on larger aspects of their illness; the most prominent of these was stigma. Of the original 23 participants, 12 (n = 4, 6, and 2 for cohorts 1, 2, and 3, respectively) were taking an antidepressant medication and completed a photo reflection session. These participants reflected upon a total of 106 photos with a median of 8 photos each (range: 1 to 18). Transcripts of reflections from these 12 participants were analyzed in the present study. All 12 participants self-reported a diagnosis of a depressive disorder (n = 9 with major depression, n = 2 with bipolar depression, n = 1 with schizoaffective disorder, with depressive episodes).

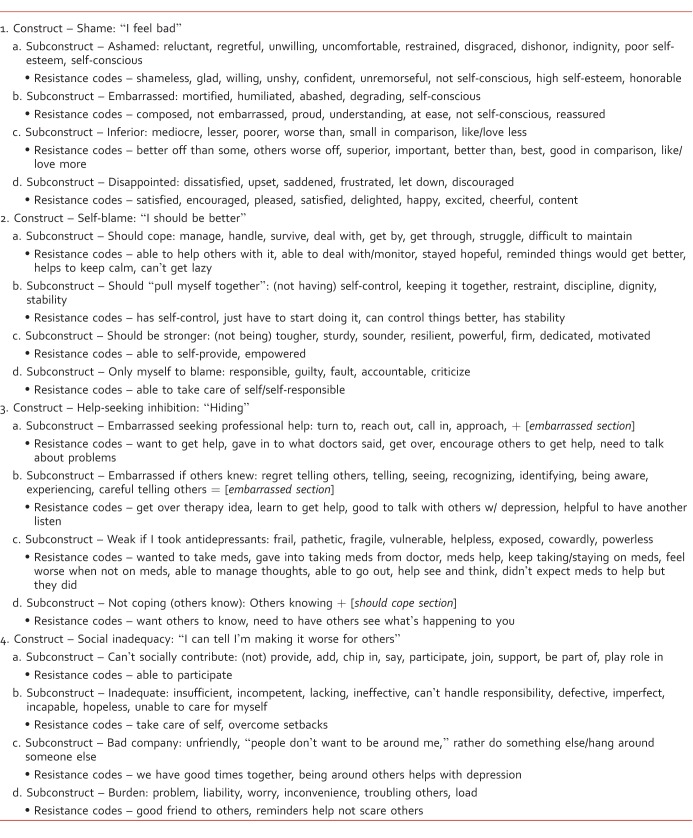

The present study is a secondary content analysis of the original data with the objective to highlight self-stigma expressed by antidepressant users. A directed conceptual content analysis approach was chosen in order to describe the characteristics of the self-stigma mentioned by the participants. The researchers developed a coding scheme based on the Self-Stigma Depression Scale (SSDS).17 The SSDS was used as the basis for the coding scheme due to its specificity of self-stigma associated with depression. The coding scheme was formed by starting with the actual descriptive words used in the 16 items and 4 constructs of the SSDS (shame, self-blame, help-seeking inhibition, and social inadequacy). This was expanded to include related words based on a standard thesaurus. Next, codes were added to represent mentions of stigma resistance (words/statements that combatted stigma or were the opposite of SSDS words). The coding scheme was modified with each transcript analysis to include additional self-stigma–related words. New codes were then applied retrospectively and prospectively to each transcript. The final coding scheme used is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1: .

Coding scheme

Data coding proceeded in a stepwise process. The authors first performed a text search for each word listed in the coding scheme. Author 1 applied codes to identified searched terms, excluding those words that did not relate to the self-stigma scale constructs (eg, the word “manage” relating to managing finances). Any time a participant used one of the words in the coding scheme while describing his or her medication experience in the context of stigma and/or stigma resistance, a code was applied. This meant that if a participant used the word “cope” 3 times within the same paragraph, this could have been counted as 3 separate instances of the code within the self-blame construct if all uses of the word were self-stigma–related. Next, the researchers independently applied codes to the transcripts, using line-by-line coding. This allowed for close examination of all participant statements to catch stigma-contextual references that did not use specific words from the coding scheme. For example, the colloquial and self-deprecating statement “…a lot of times I feel like a big pile [of excrement] sitting out in the yard” was coded as inferiority under the shame construct (Table 1). This also allowed for identification of medication-related stigma (words/statements employing SSDS construct concepts coupled with perceptions of medications). The researchers then convened to develop consensus on final coding values. Finally, all self-stigma– and medication-related stigma mentions were tallied and grouped according to construct and subconstruct. A ratio of stigma resistance to self-stigma was calculated for each individual using his or her total number of stigma resistance codes as the numerator and the total number of his or her self-stigma codes as the denominator (resistance #/SSDS #; Table 2). Therefore, numbers greater than 1 would portray more prominent discussion of stigma resistance as compared with self-stigma. The institutional review board reviewed and approved all study procedures, including informed consent of participants.

TABLE 2: .

Participant stigma codes

Results

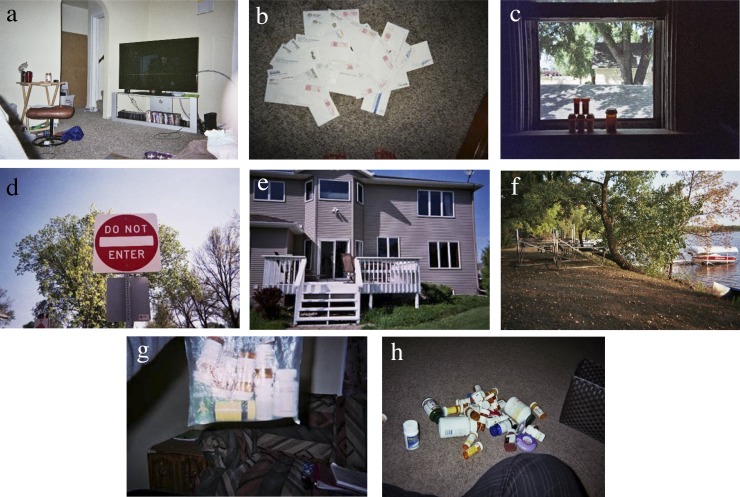

All participants mentioned self-stigma–related context and/or words at least twice during their discussion of their medication experience. Self-stigma mentions varied considerably between each participant (Table 2). Stigma resistance mentions were also prevalent. The photos and reflections included below were chosen as examples due to their easily observed depiction of the nature of the coding scheme. Pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of participants.

Self-Stigma

A total of 100 SSDS adapted codes were mentioned between the 12 participants, varying between 2 and 37 mentions per person. Variation in the self-stigma constructs of the SSDS was also apparent as all participants made mentions of stigma in at least 2 different SSDS constructs.

Self-blame was the most prominent construct of self-stigma. Aspects of this construct were mentioned nearly twice as often as any other SSDS construct. Inability to cope (ie, “should cope”) was the most mentioned subconstruct within the self-blame construct with 15 total mentions (Table 2). The “should cope” subconstruct manifested in participants' use of words describing their inability to cope sufficiently or deal with their depression properly. For example, Sarah reflected on the photo below by saying, “One of my struggles was that I was an only child and I didn't really have anyone to go to, so I had to deal with it myself [italicized for coded term]. Now that I'm an adult and I have to deal with all the responsibilities of being an adult but when you were a kid you didn't figure out how to deal with your emotional issues and that's carrying over into adulthood and being an adult and being in difficult situations and not knowing how to manage that emotionally is difficult” (Figure, part a).

FIGURE:

(a-h) Participant photos of their medication experiences

Self-blame was also evident in participants' portrayal of their perception that they should cope, many times implying their belief that their depression was something they should be able to get over. For example, a male participant explained that he was raised to be self-sufficient and believed he should take care of his condition on his own. Similarly, lack of treatment success was portrayed as a failure of oneself. Finally, participants mentioned that their depression made accomplishing tasks much harder and blamed themselves as a result. Emily, when reflecting on the photo below of piling up paperwork, stated, “When I am falling into depression then I don't do the things I should do” (Figure, part b).

The inability to “pull oneself together” subconstruct within the self-blame construct was also prominent in this analysis as it was mentioned by the participants 12 times. Sarah stated that without her medications, she would not be in control of her own head. Similarly, when she compared 2 photos of herself (one with makeup, smiling, and one without), she explained that she was “kicking myself for not looking like this every day” and “kicking myself for [the times] when I was down.”

The shame (23 mentions) and help-seeking inhibition (21 mentions) constructs of the SSDS were mentioned by the participants but with lower frequency than the self-blame construct. Mentions in the shame construct centered on negative self-judgments, especially disappointment in oneself. For example, Ryan reflected on the photo below by saying, “[My medication] doesn't cure things, but it helps control things… I did not want to take medications, I felt so defeated. But when I felt so suicidal and hit bottom, it is just so discouraging when you have to take a new medication...” (Figure, part c).

In the area of help-seeking inhibition, participants expressed desire to conceal their depression, consumption of antidepressant medication, or seeking of professional help for their depression. Participants also portrayed their embarrassment about others knowing they weren't coping well. For example, Lucas reflected on the photo by saying, “When I'm feeling depressed…I want to hang this sign on my door...When I'm feeling down I don't want people to see me because depression is sign of weakness. I don't want people to see me weak” (Figure, part d).

The social inadequacy construct was mentioned the least amount of times (12 mentions) and centered on participants' feelings of insufficiency in completing everyday tasks as well as their perception of their inadequate performance in relationships with friends or family.

Self-Stigma Resistance

Nearly all participants made mention of resisting self-stigma instead of succumbing to it, implying self-stigma resistance. Self-stigma resistance was mentioned 67 times between 9 of the 12 participants ranging from 0 to 15 codes per person. Resistance to self-stigma was most prominent in the help-seeking inhibition construct. In other words, participants frequently advocated for seeking help and expressed benefit they had received from doing so. Subconstructs of “weak if I took antidepressants” and “embarrassed seeking professional help” were most frequently resisted. For example, Sophie reflected about this photo, saying, “I think the anxiety medication and depression medication has helped because I've had the energy to [put my house on the market]. You know, because the days spending in bed don't get you anywhere” (Figure, part e).

Sophie later described that the best way for those who are depressed to get better is to “Get help if that is how depressed you are…The easiest [way people should get help] would be for people to call their doctor, one they can trust and take their advice.” Lucas stated that he was hesitant to start group therapy but now feels more comfortable, saying, “It is like your home away from home. It is a comfort, a safe place to be. Especially once you get over the group therapy idea… once you stay [in the groups], you learn all day long but if you bail then you don't learn that you can get the help that you need.” Mentions of resistance to self-stigma were noted in other subconstructs as well. For example, Lily relayed a resistance to feeling inadequate regarding her depression when she remarked the following while reflecting on the photo of a fallen tree: “It makes me feel like this tree represents me and my life to come that these two years I have fallen over and I'll start to grow again” (Figure, part f).

There was a wide distribution of ratios of the number of self-stigma mentions versus the mentions of self-stigma resistance among the individual participants. Some participants expressed more self-stigma than advocacy against it (2 participants had 0 mentions of self-stigma resistance, 1 participant had 37 self-stigma mentions with only 2 resistance codes = 0.05 ratio), and other participants mentioned advocacy against self-stigma more than they identified with it (for example, Lucas had 7 resistance codes and 2 self-stigma codes, resulting in a ratio of 3.5, and Ryan had 16 resistance codes to 8 self-stigma codes for a ratio of 2).

Medication-Related Stigma

Despite the relatively high frequency of resistance to the “weak if I took antidepressants” subconstruct, several participants made mentions of medication-related stigma that was unrelated to being weak. Most participants implied a certain judgment of “badness” about medications at least once. Stigma about medications centered on fear of long-term effects from medications and the presence of medications in one's life implying a poor outlook of the disease, especially if more medications were used. The examples below illustrate this concept:

“This is my daily medication bag. This is larger than my grandmother's medication bag and I'm a 19-year-old college student.” —Sarah (Figure, part g)

“It is one thing to say, ‘I take these' but then when I look at all of them it is so overwhelming. And it is easy to say, ‘I cannot take one or two days of meds' and it is easy to say ‘well, I never took so many meds so I should be able to do this without this many meds' …I feel like such a drug addict sometimes, taking so many pills.” —Charlotte (Figure, part h)

Discussion

In this secondary analysis of data collected from antidepressant users via the PhotoVoice method, self-stigma manifested frequently during photo-taking and reflection about medication and mental illness experiences. Self-blame was the most prominent type of self-stigma to emerge. This is a significant finding as little research has reported thus far on the nature and characterization of self-stigma specific to patients with depressive disorders. Although not reported in the context of self-stigma, the literature has shown that self-blame may have a substantial impact in depressive patients.11 Taken together, these findings suggest that self-stigma of a self-blaming nature is a point of emphasis among persons with depressive disorders. Perhaps interventions that target reducing self-stigma for patients with depression should focus especially on self-blame themes. More specifically, emphasis on “should cope” and “should pull myself together” subconstructs or themes might be most worthwhile as these areas emerged most prominently among antidepressant takers in this study.

Resistance to self-stigma was mentioned nearly as often as self-stigma in this study. Specifically, the majority of participants mentioned advocating for help-seeking and medication-taking rather than expressing self-stigmatized ideas that would inhibit their help- and/or treatment-seeking. This is perhaps, not surprising, because the inclusion criteria for the original study represented selection bias toward individuals who had already sought help and were prescribed medication for their depression. However, the frequent mention of resistance to self-stigma in this study still warrants careful consideration. Participants had overcome self-stigma to such a degree that they talked openly about it and advocated help-seeking by others. Future research, in addition to qualitatively measuring self-stigma, may be directed toward developing and refining quantitative measure of self-stigma resistance among persons with depressive disorders. Subscales within 2 different well-established self-stigma scales (the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Scale and the Stigma Scale) have been used to quantify stigma resistance somewhat reliably but largely only in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, not depressive disorders nor antidepressant takers.18,19 Furthermore, the degree to which an individual antidepressant taker expresses self-stigma resistance may have important associations with medication adherence, disease severity, quality of life, or other important patient-centered outcomes. Future studies should seek to establish associations between stigma resistance and depression-related outcomes. Previous research20 has indicated that PhotoVoice itself may be associated with lowering of stigma. Therefore, it is possible that participation in this study is partly or entirely responsible for the prominence of self-stigma resistance found. Future work should delineate effects of PhotoVoice participation on development of self-stigma resistance from selection bias toward participants possessing preachieved levels of stigma resistance, leading them to agree to participate in such studies. Alternatively, higher levels of self-stigma among persons with depression have previously been associated with higher levels of depression symptoms.21 It is possible that the reverse of this relationship may have been at play in this study. Although the authors did not measure depression severity in these participants, it is possible that a significant degree of self-stigma resistance was found because the participants were attending a partial program nearing discharge from this high level of care for their mental health condition while participating in the original study.

Medication-related stigma also emerged frequently in this study. This is consistent with the results of a survey study by Boyd and colleagues22 of veterans with psychiatric medications. There is a significant paucity of literature regarding full characterization of medication stigma and how it interfaces with self-stigma. There is also a lack of knowledge regarding approaches to reducing medication-related stigma among individuals with mental illness. These findings, coupled with those of others, suggest that there is a need to begin to explore the impacts of medication stigma and effective methods to reduce it.

The findings of this study should be viewed with limitations in mind. First, the sample size was small and may make generalizing the results difficult. However, previous work employing the PhotoVoice method in individuals with mental illness has produced meaningful and reliable results when similar sample sizes were used.23,24 Next, because this study was a secondary analysis of existing data, it is possible that there could be misattributions of self-stigma by the researchers where it was not intended by the participant. The authors did not have the opportunity to inquire of participants their intentions nor ask them to expand upon their statements for clarification as Davtyan and colleagues25 did. However, previous research regarding the implicit nature of self-stigma would suggest that much of self-stigma may be not fully recognized by the individual and may emerge outwardly and independently of self-reported measures.12

Conversely, it is possible that additional self-stigma conceptualizations may have been present within participants but were not measured by the researchers. In addition, significant overlap between untreated depression symptoms and self-stigma was noted in the transcripts during the coding process. For example, Lucas stated, “With depression your life gets derailed,” which could be interpreted as a negative perception of his ability to pull himself together or a negative cognitive distortion of depression itself, resulting in his perception that life was falling apart. Because the researchers did not measure depression symptoms nor depression severity among the participants, the researchers could not easily distinguish between internalized negativity due to untreated illness from that due to fixed internal perceptions about the individual with the illness (ie, self-stigma). However, this phenomenon is likely true of much of the self-stigma research in the field due to the high degree of association between depression severity and self-stigma.26

Conclusion

Little is known about the characteristics of self-stigma that individuals with depressive disorders experience. This study's results suggest that individuals with depressive disorders discuss self-stigma even when they are not being directly asked about it and self-blame constructs of self-stigma may be most prominent for them. In addition, stigma resistance was discussed nearly as prominently as was self-stigma. Future research should explore associations between self-stigma, stigma-resistance, and illness outcomes among individuals with depressive disorders.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Jones E. Social stigma: the psychology of marked relationships. New York: W.H. Freeman;; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corrigan P, Watson A, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. J Soc Clin Psychology. 2006;25(8):875–84. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2006.25.8.875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yen C-, Chen C-, Lee Y, Tang T-, Ko C-, Yen J- Association between quality of life and self-stigma, insight, and adverse effects of medication in patients with depressive disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(11):1033–9. doi: 10.1002/da.20413. 19288581 DOI: 10.1002/da.20413 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 19288581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright E, Gronfein W, Owens T. Deinstitutionalization, social rejection, and the self-esteem of former mental patients. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(1):68–90. doi: 10.2307/2676361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamaradova D, Latalova K, Prasko J, Kubinek R, Vrbova K, Mainerova B, et al. Connection between self-stigma, adherence to treatment, and discontinuation of medication. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:1289–98. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s99136. 27524884 PMC4966500 DOI: 10.2147/ppa.s99136 PubMed PMID: 27524884 PubMed Central PMCID: PubMed PMID: 27524884 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4966500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sedlácková Z, Kamarádová D, Prásko J, Látalová K, Ocisková M, Ocisková M, et al. Treatment adherence and self-stigma in patients with depressive disorder in remission -- a cross-sectional study. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2015;36(2):171–7. PubMed PMID: 26071588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sirey J, Bruce M, Alexopoulos G, Perlick D, Raue P, Friedman S, et al. Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(3):479–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479. 11229992 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 11229992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yanos P, Lucksted A, Drapalski A, Roe D, Lysaker P. Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: a review and comparison. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):171–8. doi: 10.1037/prj0000100. 25313530 PMC4395502 DOI: 10.1037/prj0000100 PubMed PMID: 25313530 PubMed Central PMCID: PubMed PMID: 25313530 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4395502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsang HW, Ching S, Tang K, Lam H, Law PY, Wan C. Therapeutic intervention for internalized stigma of severe mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2016;173(1-2):45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.013. 26969450 DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.02.013 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 26969450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyd J, Otilingam P, Deforge B. Brief version of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness (ISMI) scale: psychometric properties and relationship to depression, self esteem, recovery orientation, empowerment, and perceived devaluation and discrimination. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2014;37(1):17–23. doi: 10.1037/prj0000035. 24660946 DOI: 10.1037/prj0000035 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 24660946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucksted A, Drapalski A. Self-stigma regarding mental illness: definition, impact, and relationship to societal stigma. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):99–102. doi: 10.1037/prj0000152. 26075527 DOI: 10.1037/prj0000152 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 26075527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rüsch N, Corrigan P, Todd A, Bodenhausen G. Implicit self-stigma in people with mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198(2):150–3. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43b5. 20145491 DOI: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43b5 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 20145491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Werremeyer A, Aalgaard-Kelly G, Skoy E. Using Photovoice to explore patients' experiences with mental health medication: a pilot study. Ment Health Clin [Internet] 2016;6(3):142–53. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2016.05.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Werremeyer A, Skoy E. Aalgaard Kelly G. Use of Photovoice to understand the experience of taking psychotropic medications. Qual Health Res. 2017;27(13):1959–69. doi: 10.1177/1049732317693221. 29088990 DOI: 10.1177/1049732317693221 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 29088990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.PhotoVoice. (n.d.) Vision and mission [retrieved 2016 Jun 23] Available from: http://www.photovoice.org/vision-and-mission/

- 16.National Association of County and City Health Officials. Tool-Photovoice Project. (n.d.)2016 [cited. Sep 19] Available from: http://www.naccho.org/programs/public-health-infrastructure/community-health-assessment/resources.

- 17.Barney L, Griffiths K, Christensen H, Jorm A. The Self-Stigma of Depression Scale (SSDS): development and psychometric evaluation of a new instrument. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19(4):243–54. doi: 10.1002/mpr.325. 20683846 DOI: 10.1002/mpr.325 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 20683846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd Ritsher J, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(1):31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. PubMed PMID: 14572622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King M, Dinos S, Shaw J, Watson R, Stevens S, Passetti F, et al. The Stigma Scale: development of a standardised measure of the stigma of mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190(03):248–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638. 17329746 DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024638 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 17329746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russinova Z, Rogers E, Gagne C, Bloch P, Drake K, Mueser K. A randomized controlled trial of a peer-run antistigma PhotoVoice intervention. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):242–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200572. 24337339 DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200572 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 24337339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holubova M, Prasko J, Ociskova M, Marackova M, Grambal A, Slepecky M. Self-stigma and quality of life in patients with depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:2677–87. doi: 10.2147/ndt.s118593. 27799775 PMC5077239 DOI: 10.2147/ndt.s118593 PubMed PMID: 27799775 PubMed Central PMCID: PubMed PMID: 27799775 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5077239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyd J, Juanamarga J, Hashemi P. Stigma of taking psychiatric medications among psychiatric outpatient veterans. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):132–4. doi: 10.1037/prj0000122. 25821981 DOI: 10.1037/prj0000122 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 25821981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cabassa L, Parcesepe A, Nicasio A, Baxter E, Tsemberis S, Lewis-Fernández R. Health and wellness PhotoVoice project: engaging consumers with serious mental illness in health care interventions. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(5):618–30. doi: 10.1177/1049732312470872. 23258117 PMC3818106 DOI: 10.1177/1049732312470872 PubMed PMID: 23258117 PubMed Central PMCID: PubMed PMID: 23258117 PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3818106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson N, Hunter E, Murray L, Ninci L, Rolfs E, Pallikkathayil L. The experience of living with chronic mental illness: a PhotoVoice study. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2008;44(1):14–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00143.x. 18177274 DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00143.x PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 18177274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davtyan M, Farmer S, Brown B, Sami M, Frederick T. Women of color reflect on HIV-related stigma through PhotoVoice. J Assoc Nurses Aids Care. 2016;27(4):404–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.003. 27085253 DOI: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.003 PubMed PMID: PubMed PMID: 27085253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pyne J, Kuc E, Schroeder P, Fortney J, Edlund M, Sullivan G. Relationship between perceived stigma and depression severity. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(4):278–83. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120886.39886.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]