Abstract

The C/EBPα transcription factor is required for myelopoiesis, with prior observations suggesting additional contributions to B lymhopoiesis. Cebpa expression is evident in CLP and preproB cells, but is absent in proB and preB cells. We previously observed that marrow lacking the Cebpa + 37 kb enhancer is impaired in producing B cells upon competitive transplantation. Additionally, a Cebpa enhancer/promoter-hCD4 transgene is expressed in B/myeloid colony forming units. Extending these findings, pan-hematopoietic murine Cebpa enhancer deletion using Mx1-Cre leads to expanded CLP, fewer preproB cells, markedly reduced proB and preB cells, and reduced mature B cells, without affecting T cell numbers. In contrast, enhancer deletion at the proB stage using Mb1-Cre does not impair B cell maturation. Further evaluation of CLP reveals that the Cebpa transgene is expressed almost exclusively in Flt3+ multipotent CLP, versus B cell-restricted Flt3- CLP. In vitro, hCD4+ preproB cells produce both B and myeloid cells, whereas hCD4- preproB only produce B cells. Additionally, a subset of hCD4- preproB express high levels of RAG1-GFP, as seen also in proB cells. Global gene expression analysis indicates that hCD4+ preproB express proliferative pathways, whereas B cell development and signal transduction pathways predominate in hCD4- preproB. Consistent with these changes, Cebpa enhancer-deleted preproB cells down-modulate cell cycle pathways while up-regulating B cell signaling pathways. Collectively, these findings indicate that C/EBPα is required for Flt3+ CLP maturation into preproB cells and then for proliferative Cebpaint B/myeloid preproB cells to progress to Cebpalo B cell-restricted preproB cells, and finally to Cebpaneg proB cells.

Introduction

The C/EBPα basic region-leucine zipper transcription factor (TF) regulates myeloid development and transformation (1). Cebpa−/− mice manifest neonatal lethality due to hypoglycemia, with marked neutropenia but no reduction in splenic B220+ B cells or thymic CD4+ or CD8+ T cells (2). pIpC-mediated deletion of the Cebpa open-reading frame (ORF) in Cebpa(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice leads to reduced Granulocyte-Monocyte Progenitors (GMP), with absent blood granulocytes and eosinophils, low monocytes, but no change in blood, marrow, or splenic B220+ B cell or Thy1.2+ T cell numbers (3).

The Cebpa gene contains a +37 kb enhancer that is bound and activated by the RUNX1, GATA2, SCL, PU.1, and C/EBPα TFs (4, 5). Germline deletion of the +37 kb enhancer results in marked reduction of Cebpa mRNA in marrow, but not in other organs that express Cebpa, including liver, lung, and adipose tissue (6, 7). Deletion of the +37 kb enhancer in adult Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice using pIpC leads to reduced marrow GMP and neutropenia, with a 20% decrease in marrow B220+ B lineage cells (6).

Despite little apparent change in total (B220+) B lymphoid numbers with Cebpa ORF or +37 kb enhancer deletion, several prior observations suggest a role for Cebpa in B lineage development. Most notably, upon 1:1 competitive transplantation of CD45.2+ enhancer-deleted marrow with CD45.1+ control marrow into lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients, CD45.2+ cells not only contribute minimally to blood or marrow neutrophils at 19 weeks, but also manifest 4-fold reduced contribution to B220+ B cells and increased contribution to CD3+ T cells (6). This finding suggests that compensatory homeostatic mechanisms allow Cebpa ORF- or enhancer-deleted mice to retain near normal B cell numbers. In GMP, the activating H3K4me1 and H3K27Ac histone marks are prominent at the Cebpa +37 kb enhancer, whereas in Megakaryocyte-Erythroid Progenitors (MEP) these are absent. Notably, these modifications are present at intermediate levels at the Cebpa locus in the Common Lymphoid Progenitor (CLP), which express Cebpa mRNA at levels below that of GMP but above that of MEP (5, 6). Deletion of the Cebpa enhancer in Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice reduces Cebpa mRNA 8-fold in CLP and leads to 4-fold fewer B cell colony-forming units (B-CFU) when marrow is cultured in methylcellulose with IL-7 (6). Additionally, a human CD4 transgene under control of the Cebpa enhancer/promoter (Enh/prom-hCD4) is expressed not only in 70% of GMP, but also in 36% of CLP and 40% of B220+CD43+ preproB/proB/early preB cells, with loss of expression at the preB stage (8). Expression of the transgene is undetectable in CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and their DN3 and DN4 precursors and is present in only 1% of MEP. Finally, when Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 marrow is sorted into hCD4- and hCD4+ populations and plated with IL-7, the hCD4+ subset yields B/myeloid colony-forming units, with the CD19+ B cells from these colonies having increased expression of c-kit, a marker of immaturity (8).

We have now further investigated the role of C/EBPα in B lineage development, finding 2-fold reduced B220+IgM+ B cells in marrow and spleen of Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC. These mice have 6-fold expanded CLP, 2-fold fewer preproB cells, and markedly reduced proB, early preB, and preB cells. Cebpa is expressed at high levels in preproB cells, but is absent at the proB stage. Expression of the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene allows division of preproB into Cebpaint and Cebpalo subsets, the former more proliferative and having both B cell and myeloid potential and the latter possessing mainly B-lineage potential and a lymphoid differentiation/signal transduction gene expression signature. In addition, the hCD4 transgene is expressed almost exclusively in multi-potent Flt3+ CLP as opposed to B lineage-restricted Flt3- CLP. Our findings indicate that C/EBPα is required for progression of Flt3+ CLP to Cebpaint B/myeloid preproB cells and subsequently to the proB stage.

Material and Methods

Murine models

C57BL/6 (B6) Enh(f/f) mice, with loxP sites surrounding the Cebpa +37 kb enhancer, and Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice were previously described, as were B6 Cebpa Enh/Prom-hCD4 mice harboring a transgene in which the +37 kb Cebpa enhancer and −725/+125 bp promoter are linked to a human CD4 reporter (6, 8). B6 Mb1-Cre mice (9) were bred with Enh(f/f) mice to obtain Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice. RAG1-GFP B6 mice were kindly provided by K. Medina (10). Pu.1(kd/kd) mice (11), kindly provided by D. Tenen, were bred into the B6 background for >10 generations. 12–20 wk male and female mice were utilized. To induce deletion of the floxed enhancer, 300 μg of pIpC (Invivogen) was provided i.p. every other day for three doses, followed by analysis 4 wks later. PCR of tail clip DNA using a primer pair that spans the 5’ loxP site distinguishes wild-type (WT) from floxed Cebpa +37 kb enhancer alleles (6). The Mb1-Cre knockin allele was genotyped using primers 5’-CCCTGTGGATGCCACCTC-3’ and 5’-GTCCTGGCATCTGTCAGAG-3’. 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) was provided at 100 μg/g i.p. 3 hrs before marrow harvest. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health, and the protocol was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood was obtained by lancing the facial vein and collecting drops of blood into an EDTA microtainer (Pharmingen). Marrow for analysis was obtained by flushing the femurs and tibias with PBS with 3% heat-inactivated FBS (HI-FBS), followed by red blood cell lysis using ammonium chloride and enumeration of total mononuclear cells using a hemocytometer. Marrow for cell sorting was obtained by crushing femurs, tibias, and spine using mortar and pestle, followed by passage through a 40 μm cell strainer. Spleen and thymus were passed through a 40 μm cell strainer to obtain single cell suspensions. Antibodies used were from Pharmingen unless otherwise indicated. Cell analysis or sorting was done using an LSR II or FACSAria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). Mature B cells were enumerated using anti-B220-APC (RA3–6B2, Biolegend), anti-IgM-PE (R6160.2), and anti-IgD-APC (11–26c.2a, Biolegend), neutrophils were assessed using anti-Gr1-APC (RB6–8C5, Biolegend) and anti-CD11b-PE (M1/70) and T cells with anti-CD3-PerCP-Cy5.5 (145–2C11). For enumeration of B cell precursors, marrow was subjected to lineage-depletion by staining with biotin-anti-Lineage Cocktail (with anti-Gr1, -CD11b, -Ter119, and -CD3 but without anti-B220), biotin-anti-IgM (II/41, eBioscience), and biotin-anti-NK1.1 (PK136, eBioscience), followed by incubation with streptavidin-BV605 or with anti-biotin microbeads and passage through LD columns (Miltenyi). Resulting lineage-negative (Lin-) cells were stained with anti-B220-APC (RA3–6B2), anti-CD43-BV786 or -PE (S7), anti-CD93-BV650 or -PE-Cy7 (AA4.1), anti-BP-1-PE or -FITC (6C3, eBioscience), anti-CD24-BUV496 or -PE-CF594 (M1/69), and anti-CD19-BV421 or -PerCP-Cy5.5 (1D3). Human CD4 was detected using anti-hCD4-BV421 or -BF785 (RPA-T4, Biolegend). For assessment of proliferation or apoptosis in B cell precursors, anti-Ki67-FITC (16A8, Biolegend), anti-Annexin-V-FITC, or anti-BrdU-FITC were added with 7AAD. Anti-phospho-γH2AX-AlexaFluor488 (2F3, Biolegend) was used to evaluate γ-H2AX. Progenitors were identified using biotin-anti-Lineage Cocktail (with anti-B220), streptavidin-PerCP-Cy5.5, anti-c-kit-APC (2B8), and anti-Sca-1-PE-Cy7 (D7, eBioscience), in addition to anti-CD16/CD32-PE (FcγR, 2.4G2) and anti-CD34-BV421 (RAM34) for GMP or anti-CD127-PE-Texas Red (SB199) or -BV650 (Biolegend, A7R34) for CLP. CLP, preproB, and proB cells were further evaluated using anti-Flt3-PE (A2F10.1) and anti-Ly6D-eF450 (49–4H, eBioscience) or for RAG1-GFP expression. For sorting of B cell precursors, lineage-depleted marrow was stained with anti-B220-APC, anti-CD43-PE (S7), anti-BP-1-FITC (6C3, eBioscience), anti-CD24-PE-Cy7 (M1/69, eBioscience), and anti-CD19-BV421.

OP9 assay and splenic B cell class switching

OP9-GFP cells (12) were maintained in MEMα (ThermoFischer) with 20% HI-FBS (Hyclone), glutamine, β-mercaptoethanol, and penicillin/streptomycin. 1E4 sorted preproB cells were added to 80–90% confluent OP9-GFP cells in 35 mm dishes in IMDM with 10% HI-FBS, 5 ng/ml murine FL, 1 ng/ml murine IL-7 (Peprotech), and penicillin/streptomycin. Formation of mature myeloid and B lymphoid cells was assessed using anti-CD11b-PE and anti-CD19-PerCP-Cy5.5 (1D3), and B cell precursors were evaluated as done for marrow cells, in both cases gating on the GFP- population. Splenocytes were subjected to red blood cell lysis and CD43-negative selection (Miltenyi). CD43- cells were cultured in RPMI with 15% HI-FBS, β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin/streptomycin, and 20 ng/ml murine IL-4 (Peprotech) with either 10 μg/ml anti-murine CD40 (1C10, Biolegend) antibody or 25 μg/ml E. coli O55:B5 LPS (Sigma), followed by analysis on day 4 using anti-B220-APC with anti-IgE-PE (RME-1, Biolegend) and anti-IgG1-BV421 (RMG1–1, Biolegend) or anti-IgG2b-PE (RMG2b-1, Biolegend). Serum obtained by lancing the facial vein was analyzed for IgM, IgG, and IgA after 1:10,000 dilution using ELISA kits per the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen).

Quantitative RNA and DJ recombination analysis

RNA was prepared using NucleoSpin RNA II, with use of RNase-free DNase (Machery-Nagel) or by sorting cells into Trizol LS, followed by chloroform extraction, addition of equal volumes of ethanol to the top phase, and isolation using the RNA Clean and Concentrator Kit 5 (Zymo Research). First strand cDNA was prepared using AMV reverse transcriptase (Promega) and oligo-dT primer at 42°C for 1 h. Quantitative PCR was carried out using 5–25 ng of each cDNA using Radiant Lo-ROX SYBR Green supermix (Alkali Scientific). Cebpa and ribosomal subunit mS16 internal control primers were as described (6). Mb1 primers were 5’-GCATCATCACAGCAGAAGGG-3’ and 5’-GCATGTCCACCCCAAACTTC-3’. Heavy chain DJ recombination was evaluated as described (13).

Global gene expression analysis

Mouse GE 4×44K v2 slides (G4846A, Agilent) were used for microarray hybridizations. RNA was quantified with NanoDrop ND-1000 followed by quality assessment with a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). 400 ng of each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by MMLV-RT using an oligo-dT primer (System Biosciences) that incorporates a T7 promoter sequence. The cDNA was then used as a template for in vitro transcription in the presence of T7 RNA polymerase and Cyanine-3 labeled CTP (Perkin Elmer). The labeled cRNA was purified using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). 825 ng of each Cy3-labeled sample was used for hybridization at 65°C for 17 h in a hybridization oven with rotation. After hybridization, microarrays are washed and dried according to the Agilent microarray processing protocol. Microarrays were scanned using an Agilent G2565A Scanner controlled by Agilent Scan Control 7.0 software. Data were extracted with Agilent Feature Extraction 9.5.3.1 software. Agilent FE processed signal intensities were imported into GeneSpring GX 10 (Agilent Technologies). Normalization was accomplished by setting the intensity threshold to 5. Differentially expressed genes were subjected to Pathway analysis using Ingenuity Systems software and to Gene Set Enrichment Analysis using the Hallmark gene sets (Broad Institute). Analysis of fold-change between paired means of duplicate samples was conducted without subtraction of background signals. The most variable probes were those with the highest standard deviation amongst groups analyzed. Primary microarray data is available from GEO (Accession numbers GSE110029 and GSE110034, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Statistics

Means and standard deviations are shown. The Student t test was used for statistical comparisons.

Results

Pan-hematopoietic deletion of the +37 kb Cebpa enhancer impairs B lymphopoiesis

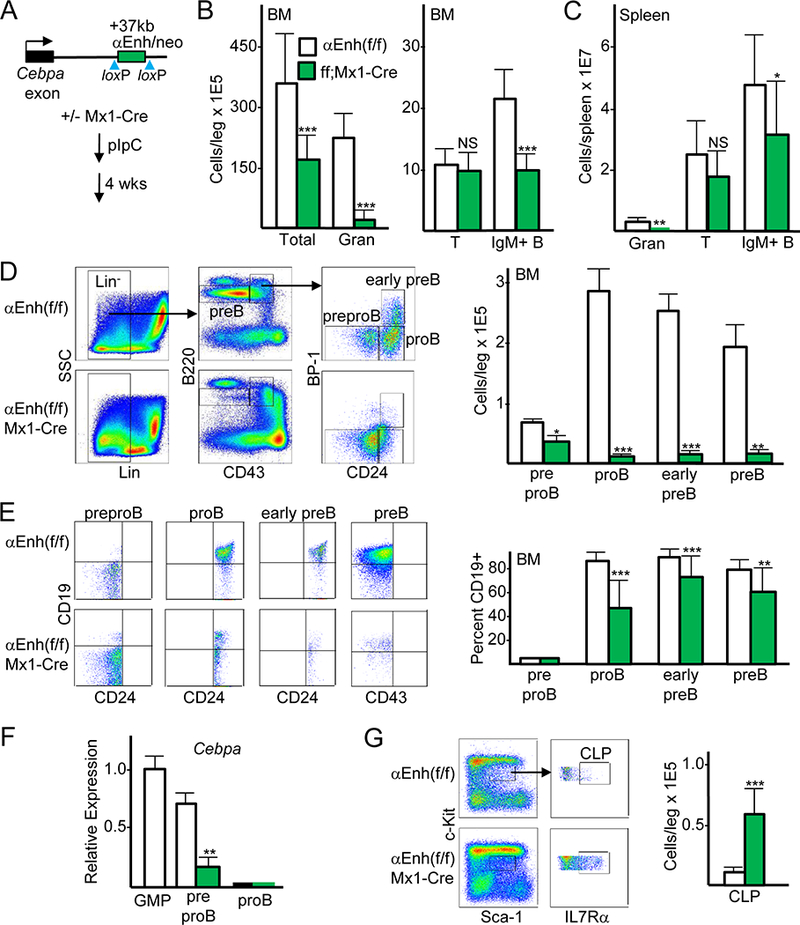

To characterize the effects of reduced C/EBPα on B lymphopoiesis, Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice were exposed to pIpC, followed by evaluation 4 weeks later to allow re-establishment of homeostasis (Fig. 1A). As seen previously, enhancer deletion led to markedly reduced marrow granulocyte numbers, with a 2-fold reduction in marrow mononuclear cells (Fig. 1B, left) (6). Total marrow CD3+ T cells were unchanged, but B220+IgM+ B cells were reduced 2-fold (Fig. 1B, right). In spleens of enhancer-deleted mice, IgM+ transitional B cells were also reduced almost 2-fold, whereas splenic and thymic T cell numbers were unaffected (Fig. 1C, Fig. S1A).

FIGURE 1.

Cebpa enhancer deletion using Mx1-Cre reduces proB, early preB, preB, and mature B cells but not T cells. (A) Diagram of the Cebpa locus in Cebpa Enh(f/f) mice, showing the single exon and floxed +37 kb enhancer, and the strategy for enhancer deletion via pIpC induction of the Mx1-Cre transgene, followed by analysis 4 wks later. (B) Total bone marrow (BM) mononuclear cells, CD11b+Gr-1+ granulocytes (Gran), CD3+ T cells, and B220+IgM+ B cells per leg (femur plus tibia) were enumerated from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre littermates after pIpC exposure (mean and SD from seven determinations). (C) Granulocytes, T cells, and IgM+ B cells were enumerated from spleens of Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice (mean and SD from four determinations). (D) Representative FC data for preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice (left), and enumeration of these subsets (right, mean and SD from five determinations). (E) Representative FC data for CD19 expression in pre-gated CD24- preproB, CD24+ proB or early preB, and CD43- preB cells from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice (left), and enumeration of CD19 expression in these subsets (right, mean and SD from 20 determinations). (F) Total cellular RNAs from GMP, preproB from control or enhancer-deleted marrow, and proB cells were analyzed for relative Cebpa mRNA expression, normalized to mS16 mRNA expression (mean and SD from three determinations). (G) Representative FC for CLP (left) and CLP enumeration in Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice (right, mean and SD from six determinations). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To analyze B cell precursor populations, we depleted marrow of mature myeloid, erythroid, T, NK, and IgM+ B cells, followed by staining with B220, CD43, BP-1, and CD24 to identify preproB (FrA), proB (FrB), early preB (FrC), and preB subsets (14, 15), as illustrated (Fig. 1D, left). We did not gate on CD93+ cells within the B220+CD43+ gate as enhancer deletion led to a leftward shift of CD93 surface expression (Fig. S1B), potentially due to C/EBPα regulation of the CD93 gene. Marrow preproB numbers were reduced 2-fold, and proB, early preB, and preB numbers were each reduced >15-fold (Fig. 1D, right). CD19 levels were present on >80% of proB, early preB, and preB cells but absent on preproB cells as expected, and Cebpa enhancer deletion reduced expression of this lineage marker 2-fold on proB cells and to a lesser extent on remaining early preB and preB cells (Fig. 1E).

Sorted preproB cells expressed Cebpa mRNA at levels ~30% below that seen in GMP, whereas proB cells did not express Cebpa, and enhancer deletion reduced Cebpa ~4-fold in the preproB population (Fig. 1F). These expression data, together with the markedly reduce proB numbers seen upon enhancer deletion, indicate that the Cebpa enhancer is activated in preproB cells and that reduced preproB Cebpa strongly interferes with progression to the proB stage.

We previously found that CLP express Cebpa mRNA at intermediate levels, 5-fold below GMP, and that deletion of the Cebpa +37 kb enhancer reduces Cebpa mRNA 8-fold in CLP (6). Consistent with prior results (6), CLP numbers were increased 6-fold in response to Mx1-Cre-mediated enhancer deletion (Fig. 1G). Reduced preproB numbers upon Cebpa enhancer deletion despite CLP expansion potentially reflects an additional requirement for Cebpa during progression of CLP to the preproB stage.

Deletion of the Cebpa enhancer at the proB stage does not impair B lymphopoiesis

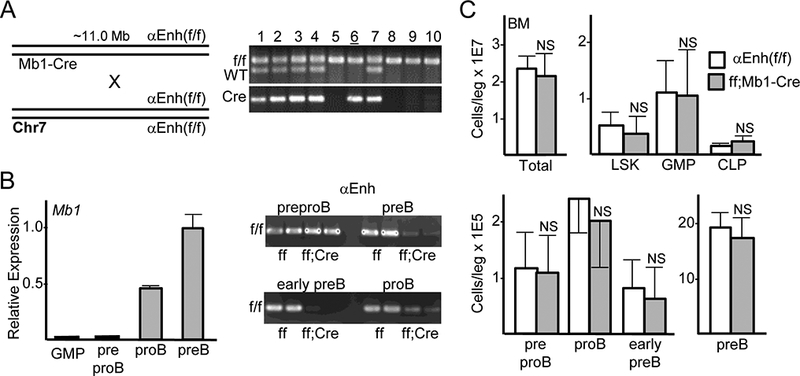

The Mb1-Cre knockin allele efficiently deletes floxed genomic DNA segments in B lineage marrow precursors; in contrast, CD19-Cre was much less effective (9). The Mb1 and Cebpa loci are separated by approximately 11 Mb on mouse chromosome 7. After crossing Cebpa Enh(f/f) with Mb1-Cre mice to obtain Enh(f/+);Mb1-Cre offspring having the Mb1-Cre allele and floxed enhancer on separate chromosome 7 homologs, these mice were crossed with Enh(f/f) mice and screened by tail clip PCR, which identified an Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre pup in 1/77 offspring to establish our colony (Fig. 2A). Mb1 mRNA was minimal in GMP and preproB from WT mice but was abundant in proB cells and increased 2-fold further in preB cells (Fig. 2B, left). Consistent with this pattern of expression, PCR analysis of genomic DNA indicated lack of Cebpa +37 kb enhancer deletion in preproB cells from Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice, whereas substantial deletion was evident in proB, early preB, and preB cells (Fig. 2B, right). In contrast to Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC, Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice showed no change in marrow cellularity, LSK, GMP, or CLP progenitor numbers, or preproB, proB, early preB, or preB B lineage precursor numbers (Fig. 2C). Thus, Cebpa enhancer deletion prior to the proB stage is required to obtain reduced numbers of proB and downstream B lineage cells.

FIGURE 2.

Cebpa enhancer deletion using Mb1-Cre does not reduce marrow proB, early preB, or preB cells. (A) Diagram of breeding strategy to obtain Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice (left). Examples of WT versus floxed Cebpa enhancer and Mb1-Cre PCR analysis - mouse 6 (underlined) has genotype Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre (right). (B) RNA from flow-sorted GMP, preproB, proB, and preB cells from WT mice was analyzed for Mb1 mRNA expression relative to mS16 mRNA, with expression in preB cells set to 1.0 (left, mean and SD from three determinations). Genomic DNA from preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells from two Enh(f/f) and two Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice were analyzed for retention of the floxed Cebpa enhancer by PCR followed by agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide staining (right). (C) Total bone marrow mononuclear cells, Lin-Sca-1+c-kit+ (LSK) cells, GMP, CLP, preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells were enumerated in Enh(f/f) and Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre littermates (mean and SD from three determinations).

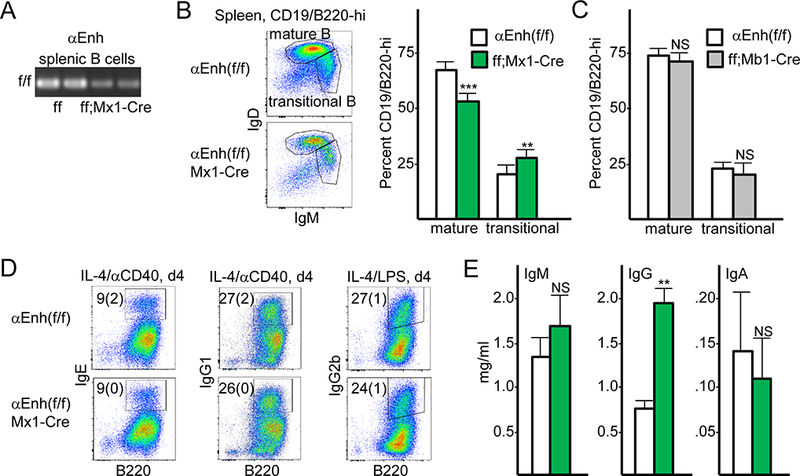

Pan-hematopoietic deletion of the +37 kb Cebpa enhancer does not affect mature B cell class switching

PCR analysis of splenic B cell DNA from Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC demonstrates that a large majority of these cells lack the Cebpa enhancer, indicating that they do not derive from an undeleted minority of CLP/preproB (Fig. 3A). Evaluation of splenic B220hiCD19hi B cells for IgM and IgD revealed a mild increase in transitional IgMhiIgDlo and a mild reduction in mature IgMloIgDhi B cells in response to pan-hematopoietic enhancer deletion (Fig. 3B); in contrast, these populations were unchanged in response to deletion of the Cebpa enhancer at the proB stage using Mb1-Cre (Fig. 3C). Splenic B cells from two Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed 4 wks earlier to pIpC were enriched by negative selection for CD43, followed by culture with IL-4 and either anti-CD40 or LPS. Representative flow cytometry (FC) and mean values for surface IgE, IgG1, and IgG2b levels on day 4, with SD from two determinations, indicate equivalent immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching (Fig. 3D). Consistent with these findings, serum IgM, total IgG, and IgA levels were not reduced upon enhancer deletion, with IgG levels actually increased >2-fold (Fig. 3E). Increased IgG was not evident in Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre compared with Enh(f/f) mice (n=3, not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Splenic B cells lacking the Cebpa +37 kb enhancer retain normal immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching. (A) Genomic DNA from CD43- splenic B cells from two Enh(f/f) and two Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed 4 wks earlier to pIpC were analyzed for retention of the floxed Cebpa enhancer by PCR. (B) Representative FC data for transitional and mature splenic B cells from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice (left), and enumeration of these subsets (right, mean and SD from four determinations). (C) Enumeration of transitional and mature splenic B cells for Enh(f/f) and Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice (mean and SD from three determinations). (D) Representative FC for IgE, IgG1, and IgG2b expression in splenic B cells cultured with IL-4 and either anti-CD40 antibody or LPS for 4 days, with mean values with SD for the percentage of Ig-expressing cells from two determinations shown. (E) Serum from Enh(f/f) and Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice was evaluated for IgM, IgG, and IgA by ELISA (mean and SD from three determinations).

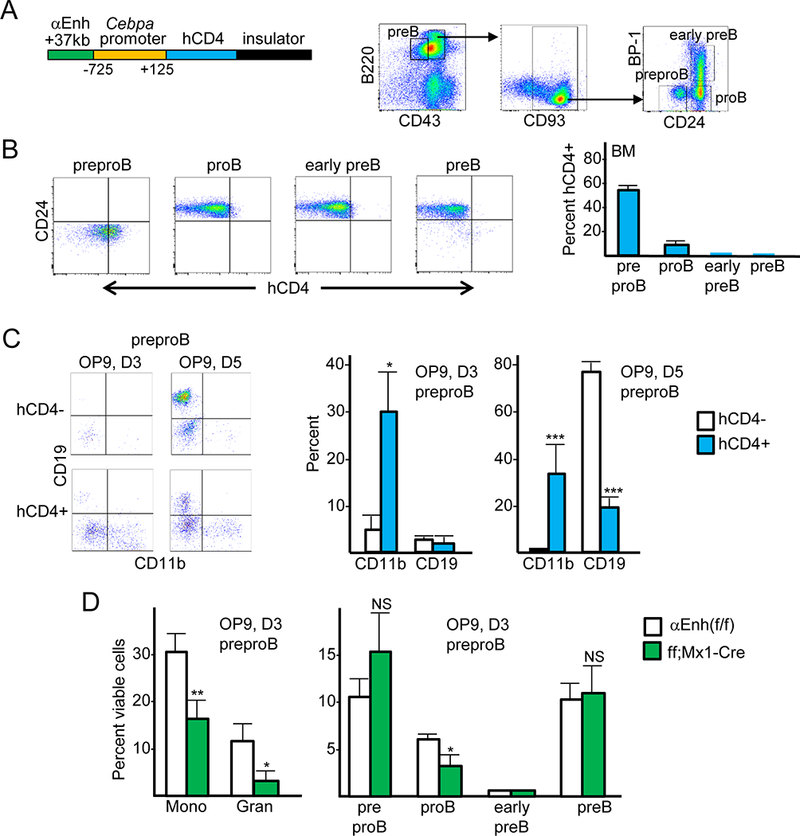

PreproB cells expressing the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene have B/myeloid potential

We next sought to characterize and compare B lineage cells that express a human CD4 Cebpa reporter with those that do not. The +37 kb Cebpa enhancer/promoter-hCD4 transgene is diagrammed (Fig. 4A, left), with hCD4 cytoplasmically truncated to prevent transmission of intracellular signals. The gating strategy used to identify preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells from these mice is also shown (Fig. 4A, right). Representative CD24/hCD4 FC data for these B lineage precursors demonstrates that the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 reporter is expressed in 50% of preproB cells and 10% of proB cells, but not in early preB or preB cells (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

PreproB cells that expresses a Cebpa +37 kb enhancer/promoter transgene have B cell and myeloid potential. (A) Diagram of the Cebpa +37 kb enhancer/promoter-hCD4 transgene (left) and gating strategy to obtain preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells from these mice (right). (B) Representative CD24/hCD4 FC from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice (left) and the proportion of B lineage precursors from these mice that express hCD4 (right, mean and SD from three determinations). (C) Representative CD11b/CD19 FC after culturing hCD4- or hCD4+ preproB cells on OP9-GFP cells with FL and IL-7 on day 3 (D3) or day 5 (D5) and the proportion of these cells that express CD11b or CD19 (mean and SD from three determinations). (D) PreproB cells isolated from the bone marrows of Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed 4 wks earlier to pIpC were plated on OP9-GFP cells with FL and IL-7 and analyzed on day 3 for CD11b+Gr-1- monocytes, CD11b+Gr-1+ granulocytes, and for preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells (mean and SD from three determinations).

To compare their lineage potential, preproB cells from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice were sorted into hCD4- and hCD4+ subsets, with representative gating shown (Fig. S1C). Equal numbers of these cells were plated onto OP9 cells with FL and IL-7 and monitored for formation of CD11b+ myeloid and CD19+ B lymphoid cells. Representative FC data on days 3 and 5 of culture are shown, along with enumeration of the percentage of cells that were CD11b+ or CD19+ on these days (Fig. 4C). Little B cell maturation was evident on day 3, whereas 78% of the hCD4- culture expressed CD19 on day 5, on average, compared to 19% of the hCD4+ culture. In contrast, the hCD4+ preproB subset yielded abundant CD11b+ myeloid cells, representing ~30% of the hematopoietic cells on both day 3 and day 5, whereas the hCD4- subset generated only 5% CD11b+ cells on day 3 and few myeloid cells on day 5. Thus, hCD4+ preproB cells, comprising about half of the total preproB population, have both myeloid and B cell potential and may be developmentally upstream of the hCD4- preproB subset. Of note, preproB cells did not form colonies in methylcellulose with IL-3/IL-6/SCF or IL-7 and did not expand sufficiently to allow FC analysis when sorted as single cells onto OP9 cells with FL/IL-7 (not shown), indicating that they are not as immature as myeloid or B cell progenitors from GMP or CLP.

Equal numbers of preproB cells from Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC 4 weeks earlier were also plated on OP9 cells with FL/IL-7, followed by FC on day 3 for monocytes, granulocytes, and B lineage precursors (Fig. 4D). Enhancer deletion reduced monocyte formation 2-fold and granulocyte formation 4-fold, consistent with the greater in vivo effect of Mx1-Cre-mediated enhancer deletion on granulocytes compared with monocytes (6). ProB formation was reduced 2-fold, although preB cell formation was unaffected. The more severe effect of enhancer deletion evident in vivo may reflect reduction of in vivo preproB cell numbers and increased permissiveness of the in vitro cultures.

The Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene is predominantly expressed in Flt3+ CLP

We previously found that ~36% of CLP express the +37 kb Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene (8). CLP can be further divided based their expression of Flt3 or Ly6D, with Flt3+ or Ly6D- CLP having multipotent potential (T, B, natural killer, dendritic cell) and Flt3- or Ly6D+ CLP having B cell-restricted potential (16, 17). Lin-Sca-1intc-kitintIL7Rα+ CLP from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgenic mice were analyzed for Flt3, Ly6D, and hCD4 expression, as shown (Fig. 5A, top). Approximately 75% of CLP are Flt3+ and 71% Ly6D+; >80% of Flt3+ but few Flt3- CLP express hCD4, whereas ~70% of either Ly6D+ or Ly6D- CLP express the hCD4 reporter (Fig. 5A, bottom). In addition, the large majority of preproB, but not proB, from these mice express Flt3 (Fig. 5B), consistent with the idea that multipotent Flt3+hCD4+ CLP give rise to Flt3+hCD4+ preproB with B/myeloid potential. CLP from Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC 4 weeks earlier were also analyzed for Flt3 and Ly6D surface expression (Fig. 5C). CLP expansion was again evident, and enhancer deletion led to ~2-fold reduction in the proportion of Flt3+ CLP without affecting the proportion of Ly6D+ CLP, consistent with preferential expression of the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene in Flt3+ but not Ly6D+ CLP.

FIGURE 5.

CLP that expresses a Cebpa +37 kb enhancer/promoter transgene preferentially express Flt3. (A) Representative FC for Flt3, Ly6D, and hCD4 on CLP from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice (top); the proportion of CLP that express Flt3 or Ly6D and the proportion of Flt3+, Flt3-, Ly6D+, or Ly6D- CLP that express hCD4 (bottom, mean and SD from three determinations). (B) Representative FC for Flt3 in preproB and proB cells from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice. (C) Representative FC for Flt3 and Ly6D on CLP from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre 4 wks after pIpC exposure (top) and the number of total CLP and percent of CLP that express Flt3 or Ly6D (bottom, mean and SD from three determinations). (D) Representative FC for RAG1-GFP in hCD4+ and hCD4- CLP, LSK, hCD4+ and hCD4- preproB, and proB cells, from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4::RAG1-GFP mice, with the proportion of cells in the indicated gates (mean and SD from three determinations).

We also utilized Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4::RAG1-GFP mice to further sub-divide CLP, with RAG1-GFP- CLP having B, natural killer, and DC potential and RAG1-GFP+ CLP largely B cell-restricted in vitro (18). RAG1-GFP expression is evident in ~72% of both hCD4+ and hCD4- CLP from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4::RAG1-GFP mice, with increased average GFP intensity in hCD4- CLP, potentially reflecting the more homogenous, B cell-restricted potential of this subset (Fig. 5D, left). In contrast, RAG1-GFP expression is minimal in the LSK population that predominantly consists of Flt3+ lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitors, a population that gives rise to CLP and almost uniformly expresses the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene (8). Finally, low-level GFP expression is evident in ~40% of hCD4+ or hCD4- preproB (Fig. 5D, right). Of note, high-level RAG1-GFP expression is seen in a distinct subset of hCD4- preproB cells (~6% on average) and in the majority of proB cells from these mice, supporting the idea that hCD4+ preproB progress to hCD4- preproB and then to proB cells.

PreproB cells expressing the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene have increased proliferation

B cell precursors from Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC were assessed for proliferation using Ki67/7AAD staining and for apoptosis and cell death using Annexin V/7AAD staining. Representative FC data for preproB and proB cells is shown (Fig. 6A, left), with enumeration of Ki67+7AAD+ S/G2/M cells, Annexin V+7AAD- apoptotic cells, and Annexin V+7AAD+ dead cells in preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells (Fig. 6A, right). No change in proliferation was seen in preproB, proB, or early preB, with a mild increase in preB S/G2/M, upon enhancer deletion. Increased cell death was evident in each enhancer-deleted population, reaching as high as 50% of preB cells, which also exhibited increased apoptotic cells. Increased apoptosis and cell death may in part account for reduced B lineage maturation beyond the preproB stage as a result of Cebpa enhancer deletion, although the degree of cell death only reached 10% in proB and early preB cells.

FIGURE 6.

PreproB cells that express a Cebpa +37 kb enhancer/promoter transgene have increased cell proliferation, and enhancer deletion reduces proliferation and increases cell death in B cell precursors. (A) Representative Ki67/7AAD and AnnexinV/7AAD FC of preproB and proB cells from Cebpa Enh(f/f) and Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC (left) and the percent of preproB, proB, early preB, and preB cells that are Ki67+, Annexin V+/7AAD- (A+7-), or Annexin V+/7AAD+ (A+7+) from these mice (mean and SD from four determinations). (B) Representative anti-BrdU/7AAD FC of the hCD4- and hCD4+ preproB subsets from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice and enumeration of the proportion in the G1, S, and G2/M phases of the cell cycle (left, mean and SD from three determinations). Representative Annexin V/7AAD FC of these same populations and the proportion that are apoptotic or dead (right, mean and SD from three determinations).

PreproB cells from Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice were also analyzed for proliferation and apoptosis. Ki67/7AAD staining suggested increased proliferation of the hCD4+ preproB subset (not shown), and anti-BrdU/7AAD staining confirmed this conclusion, with an 8-fold increase, from 2% to 16%, in the proportion of S phase cells (Fig. 6B, left). Annexin V/7AAD analysis indicated no difference in the proportion of apoptotic cells, but dead cells were reduced, from 8% in hCD4- to 4% in hCD4+ preproB, representing a small proportion of the entire population. Increased proliferation of hCD4+ preproB cells may reflect their more immature status compared with the hCD4- subset.

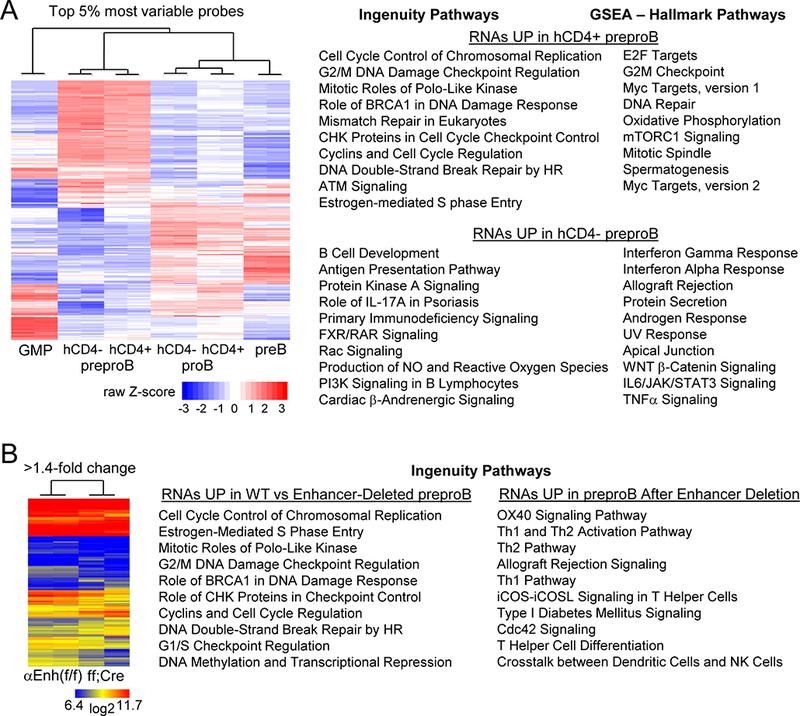

hCD4+ preproB have a proliferative and hCD4- preproB a differentiation gene expression signature

Total cellular RNA from sorted hCD4- and hCD4+ preproB and proB cells, hCD4+ GMP, and preB cells from two Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 mice were subjected to microarray analysis of global gene expression. A heat map of the top 5% most variable probes is shown (Fig. 7A, left). ProB and preB appear fairly similar in this analysis, whereas preproB are distinct from these more mature B lineage precursors and from GMP. GMP gene expression correlated more closely with that of hCD4+ than hCD4- preproB cells (average Spearman correlation coefficient −0.17 vs −0.32). Ingenuity pathway analysis (IPA) of the 526 RNAs expressed >2-fold higher in hCD4+ compared with hCD4- preproB cells revealed activation of cell cycle and DNA repair pathways in the hCD4+ subset, and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) of these RNAs indicated activation of related Hallmark Pathways, such as E2F Targets, Myc Targets, G2M Checkpoint, and DNA Repair (Fig. 7A, top right). The gene sets upregulated in these IPA pathways are provided (Table SI), and examples of increased DNA repair and cell cycle regulatory mRNAs and their average expression levels and standard deviations are listed (Table I). Rad51, Brca2, Rpa1, Pcna, Ccnb1, and Rfc5 are expressed at higher levels in hCD4+ than in hCD4- preproB cells. Of note, these and additional DNA repair genes are induced by E2F family members during cell proliferation, to maintain DNA integrity (19), and both E2f1 and E2f2 are more highly expressed in the more proliferative hCD4+ preproB subset. The mRNAs encoding the listed DNA repair factors are expressed at even higher levels in GMP, proB, and preB cells, likely reflecting their even greater proliferative fraction. Increased expression of DNA repair factors might also reflect DNA-damage or V(D)J recombination. However, DNA-damage leads to upregulation of DNA repair factors at the protein but not the RNA level (20). In addition, phospho-γ-H2AX was not increased in hCD4+ compared with hCD4- preproB cells or in their 7AAD- G0/G1 subsets (Fig. S1D and not shown), and Ig heavy chain DJ recombination was also similar in the hCD4- and hCD4+ preproB populations (Fig. S1E).

FIGURE 7.

Global gene expression analysis of B cell precursors in Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 and Enh(f/f) versus Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice. (A) Heat map for the top 5% most variable probes after microarray analysis of indicated Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 marrow subsets from two mice (left). GMP represents hCD4+ GMP. The top ten Ingenuity and Hallmark Pathways resulting from analysis of RNAs increased >2-fold in hCD4+ or in hCD4- preproB cells are shown (right). The p-values for the Hallmark pathways higher in hCD4+ cells ranged from <0.001 to 0.049, and for the pathways higher in hCD4- cells from <0.001 to 0.015. P-values for the Ingenuity Pathways, along with R values indicating the proportion of genes in each pathway affected, are provided (Table SI). (B) Heat map for those RNAs with >1.4-fold change comparing preproB cells from two Cebpa Enh(f/f) with two Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC (left). The top ten Ingenuity Pathways resulting from analysis of RNAs increased in Enh(f/f) compared with enhancer-deleted preproB cells or those increased after enhancer deletion are shown (right). P-values for these pathways, along with their R values are provided (Table SII).

Table I.

Selected RNAs Expressed in GMP and B-Lineage Subsets from Cebpa-Enh/Prom-hCD4 mice or from Cebpa Enh(f/f) vs Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC*

| GENE | GMP | preproB hCD4- | preproB hCD4+ |

proB hCD4- |

proB hCD4+ |

preB | preproB Enh(ff) |

preproB ff;Mx1Cre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myeloid | ||||||||

| Cebpa | 10.8(.2) | 8.4(.4) | 8.9(.1) | 6.0(.2) | 7.8(.2) | 6.1(.1) | 10.0(.3) | 7.8(.3) |

| Cebpb | 12.5(.1) | 10.6(.2) | 10.9(.1) | 8.0(.1) | 9.4 (0) | 7.6(.3) | 10.0 (0) | 10.6(.1) |

| Cebpd | 13.2(.2) | 11.7(.2) | 11.9(.1) | 7.7(.3) | 9.7(.1) | 6.6(.2) | 13.0(.2) | 12.4(.2) |

| Irf8 | 14.4 (0) | 17.4(.1) | 17.3(.1) | 13.0(.1) | 14.3(.1) | 13.3(.1) | 18.1 (0) | 18.2(.1) |

| Klf4 | 10.8(.2) | 12.0(.1) | 12.2(.1) | 10.6(.1) | 10.6(.1) | 11.8(.2) | 11.6(.1) | 9.3(.2) |

| Egr1 | 11.5(1) | 8.0(.1) | 9.8(.4) | 11.9(.6) | 10.5(.1) | 10.2(.4) | 7.5(.1) | 7.7(.4) |

| Pu.1 | 8.5(.2) | 6.8(.2) | 7.2(.2) | 6.8 (0) | 7.2(.2) | 7.2 (0) | -- | -- |

| IL6ra | 12.8(.1) | 12.5(.1) | 12.6(.2) | 8.0(.1) | 10.5(.1) | 9.0(.1) | 13.1(.1) | 13.1 (0) |

| Gfi1 | 12.1 (0) | 7.8(.2) | 7.9(.2) | 11.6(0) | 10.8(.1) | 11.2(.2) | 8.6 (0) | 7.6(.4) |

| B Lymphoid | ||||||||

| Tcf3/E2A | 9.2 (0) | 9.4(.1) | 9.1 (0) | 11.2(.1) | 10.8(.2) | 11.8(.1) | 9.8 (0) | 9.6 (0) |

| Ikzf1 | 8.7(.1) | 10.7(.2) | 10.0(.1) | 9.7(.1) | 9.6 (0) | 10.7(.1) | 10.3(.2) | 10.2(.4) |

| Ebf1 | 5.7(.1) | 5.9(.1) | 6.2(.2) | 13.2(.1) | 12.7(.1) | 13.4 (0) | 9.0(.3) | 7.0(.5) |

| Pax5 | 6.0(.1) | 6.0(.1) | 5.9 (0) | 7.9(.1) | 7.4 (0) | 8.1(.1) | 5.8 (0) | 5.4(.1) |

| Foxo1 | 8.2(.1) | 11.4(.1) | 11.1 (0) | 12.9 (0) | 12.4(.1) | 13.2 (0) | 11.9 (0) | 11.9(.1) |

| Bach2 | 6.9(.5) | 8.6(.1) | 8.4(.1) | 10.6 (0) | 9.6(.1) | 12.4(.1) | 8.5(.1) | 8.3(.3) |

| Hnf1a | 6.0 (0) | 6.1 (0) | 6.1(.1) | 6.0 (0) | 6.1 (0) | 6.0(.1) | 5.8 (0) | 5.7 (0) |

| Irf4 | 5.8(.1) | 8.8(.1) | 8.6(.2) | 11.6(.1) | 10.4(.1) | 13.4(.1) | 9.6(.2) | 9.6 (0) |

| Lef1 | 5.9 (0) | 6.2(.1) | 6.2(.2) | 14.0(.2) | 12.7 (0) | 12.3(.1) | 10.0(.2) | 8.0(.8) |

| IL7ra | 5.5(.1) | 12.7(.1) | 12.4(.1) | 12.2(.1) | 12.0(.1) | 13.2(.1) | 12.9 (0) | 13.0 (0) |

| Flt3 | 8.0(.1) | 10.9(.2) | 10.5 (0) | 7.8(.1) | 9.5(0) | 7.0(.2) | 10.6(.1) | 10.3(.1) |

| Mb1 | 6.4(.1) | 7.2(.3) | 6.8(.1) | 12.9 (0) | 12.6(.3) | 13.4(.1) | 9.0(.1) | 8.4 (0) |

| Cd19 | 5.8(.1) | 6.0(.2) | 6.1(.1) | 13.4(.1) | 12.8(.1) | 12.8(.1) | 9.1(.2) | 8.2(.3) |

| Ly6d | 6.2(.1) | 17.2 (0) | 17.2(.1) | 13.6(.2) | 14.3 (0) | 15.4 (0) | 17.4(.1) | 17.4(.1) |

| Rag1 | 6.0(.1) | 6.4(.2) | 6.4(.1) | 11.0(.2) | 10.4 (0) | 12.0(.1) | 8.5(.2) | 7.1(.5) |

| Rag2 | 6.0(.1) | 5.9 (0) | 6.0(.1) | 7.7 (0) | 7.4(.1) | 7.6(.1) | 6.1(.1) | 5.6(.1) |

| DNA Repair | ||||||||

| Rad51 | 10.6(.1) | 7.2(.3) | 9.8(.2) | 10.8(.1) | 10.8(.1) | 11.0(.1) | 9.7(.1) | 8.0(.9) |

| Brca2 | 10.7(.1) | 7.8 (0) | 9.8(.1) | 10.6(.1) | 10.8 (0) | 10.0(.1) | 9.6(.1) | 8.8(.3) |

| Rpa1 | 13.0(.1) | 11.3(.1) | 12.2(.1) | 13.2 (0) | 13.3 (0) | 13.0(.1) | 12.8(.1) | 12.5(.1) |

| Pcna | 14.4(.1) | 12.5(.3) | 15.0(.1) | 15.5(.1) | 14.6(.1) | 15.2(.1) | 13.9 (0) | 13.3(.3) |

| Ccnb1 | 9.9(.1) | 8.4(.1) | 9.9(.1) | 11.2(.2) | 11.1 (0) | 10.8(.2) | 8.7(.3) | 7.5(.6) |

| Rfc5 | 13.2(.1) | 11.5 (0) | 12.6(.2) | 12.7 (0) | 12.8 (0) | 12.4(.1) | 12.0(.2) | 11.9 (0) |

| proliferation | ||||||||

| E2f1 | 11.7(.1) | 10.2 (0) | 11.2(.1) | 11.2 (0) | 11.6(.2) | 11.2(.1) | 10.8(.1) | 10.6(.2) |

| E2f2 | 11.0 (0) | 10.4 (0) | 12.2 (0) | 15.2(.1) | 14.4(.2) | 15.9 (0) | 11.6(.2) | 10.6(.9) |

| Myc | 12.2(.1) | 6.2(.2) | 7.2(.2) | 10.8(.1) | 11.4(.2) | 8.0(.1) | 8.0 (0) | 7.2(.1) |

| Bcl2 | 11.2 (0) | 10.1(.2) | 11.2(.1) | 9.4(.2) | 10.0(.2) | 7.8(.3) | 10.8 (0) | 9.3(.7) |

Mean microarray intensity values and SD from two determinations, log2.

IPA and GSEA of the 249 RNAs expressed >2-fold higher in the hCD4- preproB subset revealed activation of B cell development and intra-cellular signaling pathways, e.g. Protein Kinase A Signaling and IFNγ Response (Fig. 7A, bottom right, Table SI), consistent with the idea that hCD4- B-lineage-committed preproB develop from more proliferative, hCD4+ B/myeloid preproB cells.

The average expression levels of several key regulators of myeloid and lymphoid development are listed for the six Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 marrow cell populations evaluated (Table I). Cebpa mRNA is higher in hCD4+ compared with hCD4- preproB and proB cells, Egr1 is higher in hCD4+ preproB cells, and Cebpb, Cebpd, Irf8, and IL6ra are higher in hCD4+ proB cells. For B lymphoid regulators, Izkf1 is higher in hCD4- preproB cells, and Ebf1, Pax5, Foxo1, Irf4, and Lef1 are higher in hCD4- proB cells. The expression pattern of these myeloid and lymphoid TFs is consistent with increased B lymphoid potential and reduced myeloid potential of CebpalohCD4- compared with CebpainthCD4+ preproB cells. Mb1, Cd19, Rag1, and Rag2 are at or near background levels in preproB and increase in proB cells, as expected.

Cebpa enhancer deletion shifts preproB from a proliferative to an intracellular signaling signature

Total cellular RNA from preproB cells isolated from two Cebpa Enh(f/f) or Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed 4 wks earlier to pIpC were also subjected to microarray analysis of global gene expression. A heat map for the RNAs with >1.4-fold change is shown (Fig. 7B, left). IPA of the 1044 RNAs expressed >1.4-fold higher in preproB cells from Enh(f/f) mice revealed increased activity of cell cycle and DNA repair pathways, with nine of the top ten pathways identical to those more active in hCD4+ compared with hCD4- preproB cells (Fig. 7B center, Table SII). Expression of Rad51, Brca2, Pcna, Ccnb1, E2f2, and Myc levels were reduced by Cebpa enhancer deletion (Table I), as was Bcl2, whose gene is activated by C/EBPα (21).

IPA analysis of the 825 RNAs more abundant after enhancer deletion revealed induction of lymphoid intracellular signaling pathways, albeit several active in T cells and none identical to those prominent in hCD4- preproB cells (Fig. 7B right, Table SII). Perhaps the larger reduction in Cebpa that occurs consequent to +37 kb enhancer deletion compared to the difference in Cebpa between hCD4+ and hCD4- preproB cells accounts for differences seen in signaling pathways retained.

Cebpa enhancer deletion led to reduced preproB expression of the myeloid regulators Cebpa, Cebpb, Cebpd, Klf4, and Gfi1, and also to reduced levels of Ebf1, Lef1, Mb1, Cd19, Rag1, and Rag2 (Table I). Pu.1 mRNA was not detected on the array, but qRT-PCR analysis demonstrated 1.6-fold reduction (Fig. S2A). Pu.1(kd/kd) mice lacking the −14 kb Pu.1 enhancer have 3-fold reduce Pu.1 mRNA in B220+ marrow B cells and manifest a 14-fold reduction in the CD43+B220+ preproB/proB/early preB population and 28-fold fewer preB cells (22), similar to our findings with Cebpa Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC. We evaluated Pu.1(kd/kd) mice and confirmed these defects in B lymphopoiesis; additionally, we found that these mice have markedly reduced numbers of total and Flt3+ CLP, preproB, proB, and early preB cells (Fig. S2B).

Discussion

C/EBPα is considered a master regulator of myeloid lineage development, its absence leading to markedly reduced formation of GMP, granulocytes, and monocytes (1–3). In addition, exogenous C/EBPα reprograms CD19+ marrow or splenic B cells into macrophages (23). However, our previous work demonstrates that Cebpa is expressed in a subset of CLP and that markedly reduced expression of Cebpa consequent to pan-hematopoietic deletion of its +37 kb hematopoietic enhancer using Mx1-Cre results in 4-fold reduced B cell production in competitive transplantation (6). We now demonstrate that enhancer deletion leads to impaired CLP to preproB progression, with 2-fold reduced preproB despite 6-fold increased CLP. Additionally, we find a striking deficiency in the preproB to proB transition. Despite markedly reduced proB and proB cells, marrow and spleen IgM+ transitional B cells were only reduced 2-fold, likely reflecting compensation downstream of the preB subset. Residual mature splenic B cells manifested normal immunoglobulin heavy chain class switching and IgM, IgG, and IgA production. Lack of reduction in total B220+ cells in mice lacking the Cebpa ORF may reflect similar homeostatic mechanisms (2, 3). Expression of B220 on plasmacytoid dendritic cells and subsets of T cells and NK cells may also have contributed to these prior observations (24–26). Furthermore, bialleleic Cebpa ORF deletion, but not enhancer deletion, results in complete absence of neutrophils as well as induction of Cebpg (6, 27), a dominant-inhibitor of the entire C/EBP family, both of which may affect B cell numbers. Cebpa +37 kb enhancer deletion reduces Cebpa mRNA 8-fold in CLP (6). Consistent with a functional role for C/EBPα in preproB cells, this population expresses Cebpa at levels near that of GMP, and Mx1-Cre-mediated enhancer deletion reduces preproB Cebpa 4-fold. ProB cells express little Cebpa, and Enh(f/f);Mb1-Cre mice, with onset of Cebpa enhancer deletion at the proB stage, did not manifest expanded CLP or deficits in preproB, proB, early preB, or preB cells.

Using Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 reporter mice, preproB could be divided into hCD4+ and hCD4- subsets, the former expressing 1.4-fold higher Cebpa RNA, on average. A subset of hCD4+ preproB may express even higher levels of Cebpa. Of note, the Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene is regulated by multiple TFs, including Runx1 and Ets family members (5), and so its increased expression in the hCD4+ preproB subset might not only reflect increased C/EBPα but also increased activity of these factors. hCD4+ preproB generated similar numbers of B and myeloid cells upon culture with OP9 cells and FL/IL-7, whereas hCD4- preproB mainly formed B cells. In addition, hCD4+ preproB manifested a proliferative gene expression signature and a markedly increased proportion of cells in the S phase of the cell cycle compared with hCD4- preproB, which harbored a B cell development and signal transduction gene expression pattern. Moreover, concordance between the proliferative pathways down-modulated upon Cebpa enhancer deletion in Enh(f/f);Mx1-Cre mice exposed to pIpC and those most prominent in hCD4+ preproB cells support a model in which CebpainthCD4+ preproB with B/myeloid potential give rise to CebpalohCD4- preproB cells, which then mature into Cebpaneg proB cells (Fig. 8A).

FIGURE 8.

Model for the role of C/EBPα in early B lymphopoiesis. (A) Multipotent Cebpaint Flt3+ CLP predominantly generate Cebpaint preproB, which give rise to myeloid cells or to Cebpalo preproB, the latter progressing to the Cebpaneg proB stage. Efficient Flt3+ CLP to preproB and preproB to proB progression requires C/EBPα (α). PreproB express both myeloid and lymphoid TFs, as listed, whereas proB cells down-modulate myeloid TFs and express increased levels of several lymphoid TFs (denoted by larger font) and Pax5. (B) Gene regulatory network linking TFs that control B lineage commitment and progression. Ikaros induces E2A, EBF1, and Foxo1, which then induce each other and Pax5. E2A, EBF1, Foxo1, and Pax5 cooperatively activate genes such as Mb1 and CD19 to specify the proB stage. Bach2 is induced by B lineage TFs and represses Cebpa (and Cebpb) to suppress myelopoiesis, while inducing Foxo1 to further favor B lymphopoiesis. C/EBPα may contribute to B lymphopoiesis by inducing PU.1, which cooperates with IRF4/IRF8 to induce Pax5, and by directly stimulating Bach2 gene expression.

In CLP we find a striking correlation between expression of the Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4 transgene and Flt3, but not Ly6D. PreproB almost uniformly express Flt3, suggesting that multi-potent Flt3+ CLP give rise to hCD4+ preproB with B/myeloid potential, which then progress to hCD4- preproB with B cell-restricted potential (Fig. 8A).

In addition to myeloid TFs, preproB express the lymphoid Izkf1, Ebf1, E2A, Pu.1, Foxo1, Bach2, and Irf4 TFs. ProB manifest even higher levels of Ebf1, E2A, Foxo1, Bach2, and Irf4, with onset of Pax5 expression, suggesting that myeloid TFs suppress expression of these lymphoid TFs in preproB cells (Table I, Fig. 8A). Absence of Izkf1 or Pu.1 blocks lymphoid development at the lymphoid-primed multipotent progenitor stage, absence of E2A at the Ly6D- CLP stage, absence of Ebf1 or Foxo1 at the Ly6D+ CLP stage, and absence of Pax5 at the preproB stage (28–33). In addition, Hnf1a−/− mice have markedly reduced B lymphopoiesis beyond preproB (34). Pax5−/− preproB cells have myeloid, T cell, and NK cell potential, and their rescue with low-level Pax5 leads to a biphenotypic B220+CD19-CD11b+Gr-1- B/myeloid state (35), consistent with our finding that Cebpa Enh/prom-hCD4+ preproB have functional B/myeloid potential.

Ikaros is thought to induce E2A, Ebf1, and Foxo1, which then further induce each other as well as Pax5. PU.1 also induces Pax5 in conjunction with Irf4/Irf8. E2A, EBF1, Foxo1, and Pax5 then act in a combinatorial manner to enable proB cell formation and subsequent B cell maturation (36, 37. 38, 39, Fig. 8B). C/EBPα induces Pu.1 gene transcription through its promoter and −14 kb enhancer (40, 41), and Cebpa +37 kb enhancer deletion reduced Pu.1 mRNA 1.6-fold in preproB cells, potentially contributing to impaired B lymphopoiesis upon Cebpa enhancer deletion. However, our finding that the B lineage phenotype of Pu.1(kd/kd) mice differs from that of Cebpa enhancer-deleted mice, with essentially absent rather than expanded CLP, suggests that reduced PU.1 consequent to Cebpa enhancer deletion does not account for the deficit seen in CLP to preproB progression.

Bach2 is induced by E2A, Foxo1, and Pax5 in immature B lineage cells and suppresses myeloid potential by repressing transcription of Cebpa and Cebpb; Bach2 also reciprocally induces Foxo1 to favor B lymphopoiesis (36, 42, 43). In addition, Cebpa binds a Bach2 super-enhancer and may thereby activate its expression (43, 44, Fig. 8B). Reduced C/EBPα consequent to +37 kb Cebpa enhancer deletion may therefore also impair B lymphopoeisis by reducing Bach2. Of note, in Cebpa Enh/Prom-hCD4 transgenic mice Bach2 was expressed 4-fold lower in hCD4- or hCD4+ preproB cells than in hCD4- proB cells, perhaps leading to Cebpa levels intermediate to those in GMP and proB (Table I). Mice lacking C/EBPβ have 2-fold reduced marrow B220+ and B220+/IgM- B cells (45), which may reflect activities similar to C/EBPα in the B cell lineage. Future investigations will further define the gene regulatory networks that account for our finding that C/EBPα is required in CLP and in preproB cells and yet is suppressed at the immediately downstream proB stage during B lymphopoiesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wayne Yu and Ludmila Danilova for assistance with IPA and GSEA and Stephen Desiderio for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL130034 to. A.D.F., T32 CA60441 to T.B., and P30 CA006973) and by the Giant Food Children’s Cancer Research Fund.

Abbreviations used in this article:

- B6, C57BL/6, CLP

common lymphoid progenitor

- FC

flow cytometry

- GMP

granulocyte-monocyte progenitor

- GSEA

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

- IPA

Ingenuity Pathway Analysis

- MEP

megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors

- ORF

open-reading frame

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Friedman AD C/EBPα in normal and malignant myelopoiesis. 2015. Int. J. Hematol 101: 330–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang DE, Zhang P, Wang ND, Hetherington CJ, Darlington GJ, and Tenen DG. 1997. Absence of G-CSF signaling and neutrophil development in CCAAT enhancer binding protein α-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA MediMedia 94: 569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang P, Iwasaki-Arai J, Iwasaki H, Fenyus ML, Dayaram T, Owens BM, Shigematsu H, Levantini E, Huettner CS, Lekstrom-Himes JA, Akashi K, and Tenen DG. 2004. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell repopulating capacity and self-renewal in the absence of the transcription factor C/EBPα. Immunity 21: 853–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo H, Ma O, Speck NA, and Friedman AD. 2012. Runx1 deletion or dominant inhibition reduces Cebpa transcription via conserved promoter and distal enhancer sites to favor monopoiesis over granulopoiesis. Blood 119: 4408–4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper S, Guo H, and Friedman AD. 2015. The + 37 kb Cebpa enhancer is critical for Cebpa myeloid gene expression and contains functional sites that bind SCL, GATA2, C/EBPα, PU.1, and additional Ets factors. PLoS One 10: e0126385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo H, Cooper S, and Friedman AD. 2016. In vivo deletion of the +37 kb Cebpa enhancer markedly reduces Cebpa mRNA in myeloid progenitors but not in non-hematopoietic tissues to impair granulopoiesis. PLoS One 11: e0150809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avellino R, Havermans M, Erpelinck C, Sanders MA, Hoogenboezem R, van de Werken HJ, Rombouts E, van Lom K, van Strien PM, Gebhard C, Rehli M, Pimanda J, Beck D, Erkeland S, Kuiken T, de Looper H, Gröschel S, Touw I, Bindels E, and Delwel R. 2016. An autonomous CEBPA enhancer specific for myeloid-lineage priming and neutrophilic differentiation. Blood 127: 2991–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo H, Ma O, and Friedman AD. 2014. The Cebpa +37 kb enhancer directs transgene expression to myeloid progenitors and to long-term hematopoietic stem cells. J. Leuk. Biol 96: 419–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobeika E, Thiemann S, Storch B, Jumaa H, Nielsen PJ, Pelanda R, and Reth M. 2006. Testing gene function early in the B cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103: 13789–13794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuwata N, Igarashi H, Ohmura T, Aizawa S, and Sakaguchi N. 1999. Cutting edge: absence of expression of RAG1 in peritoneal B-1 cells detected by knocking into RAG1 locus with green fluorescent protein gene. J. Immunol 163: 6355–6359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenbauer F, Wagner K, Kutok JL, Iwasaki H, Le Beau NM, Okuno Y, Akashi K, Fiering S, and Tenen DG. 2004. Acute myeloid leukemia induced by graded reduction of a lineage-specific transcription factor, PU.1. Nature Genet. 36: 624–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.La Motte-Mohs RN, Herer E, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. 2005. Induction of T-cell development from human cord blood hematopoietic stem cells by Delta-like 1 in vitro. Blood 105: 1431–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schlissel MS, Corcoran LM, and Baltimore D. 1991. Virus-transformed pre-B cells show ordered activation but not inactivation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement and transcription. J. Exp. Med 173: 711–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardy RR, Carmack CE, Shinton SA, Kemp JD, and Hayakawa K. 1991. Resolution and characterization of pro-B and pre-pro-B cell stages in normal mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol 189: 3271–3283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rumfelt LL, Zhou Y, Rowley BM, Shinton SA, and Hardy RR. 2006. Lineage specification and plasticity in CD19- early B cell precursors. J. Exp. Med 203: 675–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karunsky H, Inlay MA, Serwold T, Bhattacharya D, and Weissman IL. 2008. Flk2+ common lymphoid progenitors possess equivalent differentiation potential for the B and T lineages. Blood 111: 5562–5570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inlay MA, Bhattacharya D, Sahoo D, Serwold T, Seita J, Karunsky H, Plevritis SK, Dill DL, and Weissman IL. 2009. Ly6d marks the earliest stage of B-cell specification and identifies the branchpoint between B-cell and T-cell development. Genes Dev. 23: 2376–2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Esplin BL, Iida R, Garrett KP, Huang ZL, Medina KL, and Kincade PW. 2013. RAG-1 and Ly6D independently reflect progression in the B lymphoid lineage. PLoS One 8:e72397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren B, Cam H, Takahashi Y, Volkert T, Terragni J, Young RA, and Dynlacht BD. 2002. E2F integrates cell cycle progression with DNA repair, replication, and G2/M checkpoints. Genes. Dev 16: 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein M and Kastan MB. 2015. The DNA damage response: implications for tumor responses to radiation and chemotherapy. Annu. Rev. Med 66: 129–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paz-Priel I, Cai DH, Wang D, Kowalski J, Blackford A, Liu H, Heckman CA, Gombart A, Koeffler HP, Boxer LM, and Friedman AD. 2005. C/EBPα and C/EBPα myeloid oncoproteins induce Bcl-2 via interaction of their basic regions with NF-κB p50. Mol. Cancer Res 3: 585–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenbauer F, Owens BM, Yu L, Tunag JR, Steidl U, Kutok JL, Clayton LK, Wagner K, Scheller M, Iwasaki H, Liu C, Hackanson B, Akashi K, Leutz A, Rothstein TL, Plass C, and Tenen DG. Lymphoid cell growth and transformation are suppressed by a key regulatory element of the gene encoding PU.1. Nat. Genet 2006; 38: 27–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie H, Ye M, Feng R, and Graf T. 2004. Stepwise reprogramming of B cells into macrophages. Cell 117: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merad M, Sathe P, Helft J, Miller J, and Mortha A. 2013. The dendritic cell lineage: ontogeny and function of dendritic cells and their subsets in the steady state and the inflamed setting. Annu. Rev. Immunol 31: 563–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renno T, Attinger A, Rimoldi D, Hahne M, Tschopp J, and MacDonald HR. 1998. Expression of B220 on activated T cell blasts precedes apoptosis. Eur. J. Immunol 28: 540–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Depletion of B220+NK1.1+ cells enhances the rejection of established melanoma by tumor-specific CD4+ T cells. 2015. Wilson KA, Goding SR, Neely HR, Harris KM, and Antony PA. Oncoimmunology 4:e1019196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alberich-Jordà M, Wouters B, Balastik M, Shapiro-Koss C, Zhang H, Di Ruscio A, Radomska HS, Ebralidze AK, Amabile G, Ye M, Zhang J, Lowers I, Avellino R, Melnick A, Figueroa ME, Valk PJ, Delwel R, and Tenen DG. 2012. C/EBPγ deregulation results in differentiation arrest in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Clin. Invest 122: 4490–4504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshida T, Ng SY-M, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, and Georgopoulos K. 2006. Early hematopoietic lineage restrictions directed by Ikaros. Nat. Immunol 7: 382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, and Singh H. 1994. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science 265: 1573–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bain G, Maandag ECR, Izon DJ, Amsen D, Kruisbeek AM, Weintraub BC, Krop I, Schlissel MS, Freeney AJ, van Roon M, van der Valk M, te Rile HPJ, Berns A, and Murre C. 1994. E2A proteins are required for proper B cell development and initiation of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements. Cell 79: 885–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin H and Grosschedl R. 1995. Failure of B-cell differentiation in mice lacking the transcription factor EBF. Nature 376: 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mansson R, Welinder E, Ahsberg J, Lin YC, Benner C, Glass CK, Lucas JS, Sigvardsson M, and Murre C. 2012. Positive intergenic feedback circuitry, involving EBF1 and FOXO1, orchestrates B-cell fate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 21028–21033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nutt SL, Heavey B, Rolink AG, and Busslinger M. 1999. Commitment to the B-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. J. Immunol 401: 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Wnuck Lipinski K, Sattler K, Peters S, Weske S, Keul P, Klump H, Heusch G, Gothert JR, and Levkau B. 2016. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1A is a cell-intrinsic transcription factor required for B cell differentiation and development in mice. J. Immunol 196: 1655–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simmons S, Knoll M, Drewell C, Wolf I, Mollenkopf H-J, Bouquet C, and Melchers F. 2012. Biphenotypic B-lymphoid/myeloid cells expressing low levels of Pax5: potential targets of BAL development. Blood 120: 3688–3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin YC, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, Heinz S, Welinder E, Mansson R, Sigvardsson M, Hagman J, Espinoza CA, Dutkowski J, Ideker T, Glass CK, and Murre C. 2010. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat. Immunol 11: 635–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roessler S, Gyory I, Imhof S, Spivakov M, Williams RR, Busslinger M, Fisher AG, and Grosschedl R. 2007. Distinct promoters mediate the regulation of Ebf1 gene expression by interleukin-7 and Pax5. Mol. Cell. Biol 27: 579–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Decker T, Pasco di Magliano M, McManus S, Sun Q, Bonifer C, Tagoh H, and Busslinger M. 2009. Stepwise activation of enhancer and promoter regions of the B cell commitment gene Pax5 in early lymphopoiesis. Immunity 30: 508–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferreiros-Vidal I, Carroll T, Taylor B, Terry A, Liang Z, Bruno L, Dharmalingam G, Khadayate S, Cobb BS, Smale ST, Spivakov M, Srivastava P, Petretto E, Fisher AG, and Merkenschlager M. 2013. Genome-wide identification of Ikaros targets elucidates its contribution to mouse B-cell lineage specification and pre-B-cell differentiation. Blood 121: 1769–1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kummalue T and Friedman AD. 2003. Cross-talk between regulators of myeloid development: C/EBPα binds and activates the promoter of the PU.1 gene. J. Leuk. Biol 72: 464–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeamans C, Wang D, Paz-Priel I, Torbett BE, Tenen DG, and Friedman AD. 2007. C/EBPα binds and activates the PU.1 distal enhancer to induce monocyte lineage commitment. Blood 110: 3136–3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Itoh-Nakadai A, Hikota R, Muto A, Kometani K, Watanabe-Matsui M, Sato Y, Kobayashi M, Nakamura A, Miura Y, Yano Y, Tashiro S, Sun J, Ikawa T, Ochiai K, Kurosaki T, and Igarashi K. 2014. The transcription factor repressors Bach2 and Bach1 promote B cell development by repressing the myeloid program. Nat. Immunol 15: 1171–1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Itoh-Nakadai A, Matsumoto M, Kato H, Sasaki J, Uehara Y, Sato Y, Ebina-Shibuya R, Morooka M, Funayama R, Nakayama K, Ochiai K, Muto A, and Igarashi K. 2017. A Bach2-Cebp gene regulatory network for the commitment of multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Cell Reports 18: 2401–2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whyte WA, Orlando DA, Hnisz D, Abraham BJ, Lin CY, Kagey MH, Rahl PB, Lee TI, and Young RA. 2013. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153: 307–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen X, Weimin L, Ambrosino C, Ruocco MR, Poli V, Romani L, Quinto I, Barbieri S, Holmes KL, Venuta S, and Scala G. 1997. Impaired generation of bone marrow B lymphocytes in mice deficient in C/EBPβ. Blood 90: 156–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.