Abstract

Considering retreatment following recovery from an immune-related adverse event (irAE) is a common clinical scenario, but the safety and benefit of retreatment is unknown. We identified patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with anti–PD-L1 who had treatment held due to irAEs and divided them into two groups: those retreated with anti–PD-L1 (retreatment cohort) or those who had treatment stopped (discontinuation cohort). Out of 482 NSCLC patients treated with anti–PD-L1, 68 (14%) developed a serious irAE requiring treatment interruption. Of these, 38 (56%) were retreated and 30 (44%) had treatment discontinued. In the retreatment cohort, 18 (48%) patients had no subsequent irAEs, 10 (26%) had recurrence of the initial irAE, and 10 (26%) had a new irAE. Most recurrent/new irAEs were mild (58% grade 1–2) and manageable (84% resolved or improved to grade 1). Two treatment-related deaths occurred. Recurrent/new irAEs were more likely if the initial irAE required hospitalization, but the initial grade and time to retreatment did not influence risk. Among those with no observed partial responses prior to the irAE, PFS and OS were longer in the retreatment cohort. Conversely, for those with objective responses prior to the irAE, PFS and OS were similar in the retreatment and discontinuation cohorts. Among patients with early objective responses prior to a serious irAE, outcomes were similar, whether or not they were retreated. Together, data suggest that benefit may occur with retreatment in patients with irAEs who had no treatment response prior to irAE onset.

Keywords: immune-related adverse events, NSCLC, anti–PD-1, anti–PD-L1, immune checkpoint blockade

Introduction

The relatively modest toxicity profile of immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) has contributed to the rapid and broad use of these agents. However, the capacity to leverage the immune system against cancer is accompanied by a distinct spectrum of side effects termed immune-related adverse events (irAEs). These immune-mediated toxicities can involve nearly any organ system and are characterized by uncertain predictive features and idiosyncratic timing of onset, but are largely reversible with immunosuppression and/or discontinuation of therapy(1–6). Between 3%–12% of patients will discontinue anti–PD-L1 therapy due to treatment-related adverse events, 16% of which will discontinue anti–CTLA-4 therapy, and rates may be higher when anti–CTLA-4 and anti–PD-L1 therapies are combined(7,8). Although these events are infrequent, the broad (and growing) use of anti–PD-L1 therapy yields a substantial absolute number of individuals with irAEs.

Early recognition and unifying management strategies of irAEs have been important in the effort to optimize the safety of anti–PD-L1 therapy. Available management guidelines(9–11) generally focus on decisions about holding or discontinuing therapy and on the use of immunosuppressants to treat irAEs. However, consideration of retreatment following improvement from an irAE is a frequent clinical scenario that currently is lacking data. The routine guidance following most grade 3 or grade 4 irAEs is to permanently discontinue ICB therapy(12), but this recommendation is based solely on expert consensus and anecdotal experience.(13,14) No systematic effort to examine the safety and outcomes of retreatment with anti–PD-L1 therapy following the recovery from an irAE has been performed, and an uncertainty remains about the likelihood of recurrent irAEs and the value of continued therapy following initial toxicity, which are central to informing provider decisions and discussion of risk and benefit with patients.

To address this critical knowledge gap, we systematically reviewed the experience of nearly five hundred patients with NSCLC treated with anti–PD-L1–based therapy at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) to identify patients with irAEs requiring a delay in therapy and who were later retreated.

Materials and Methods

Patients

In accordance with the Belmont report and following MSKCC Institutional Review Board approval for retrospective review of records and waiver of consent, we retrospectively identified patients with advanced NSCLC treated with anti–PD-1/anti–PD-L1 therapy (nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, or durvalumab), either as monotherapy or in combination with anti–CTLA-4 therapy (ipilimumab or tremelimumab), from April 2011 to May 2016. Pharmacy records were reviewed to capture patients who had a treatment delay longer than one week between planned doses of immunotherapy. Cases were reviewed to determine whether treatment was interrupted due to an irAE or other causes. Adverse events were defined as irAEs at the discretion of the investigator based on the suspicion to be immune-mediated in nature, a new onset during treatment with immunotherapy without evident alternative etiology, may be treated with immune suppression, and included events such as pneumonitis, colitis, endocrinopathies, hepatitis, nephritis, dermatitis, myositis, arthritis, or neurologic disorders. Those who had treatment interrupted due to an irAE and later retreated were considered the “retreatment cohort”. Patients who had more than one treatment interruption due to an irAE were examined for the first event only. The time to retreatment was defined as the time between the detection of the irAE and the date when retreatment was initiated. Patients who received an additional systemic anti-cancer treatment between the time of irAE and retreatment with anti–PD-L1 therapy were excluded.

To provide comparison, we identified patients whose treatment was permanently stopped due to an irAE (“discontinuation cohort”). We excluded patients who discontinued treatment and who also had concurrent disease progression because they were not considered “eligible” for retreatment. This exclusion avoids potential confounding factors when examining longer-term efficacy in patients in the retreatment compared to the discontinuation cohort. Supplementary Table S1 characterizes the full cohort of 482 patients who were reviewed for inclusion.

Toxicity and response assessment

Characteristics of the initial irAE associated with treatment interruption or discontinuation were annotated (F.C.S., H.R., M.D.H). Timing of retreatment and occurrence of recurrent or new irAEs were also determined. Adverse events were graded according to Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v4.0). Radiological outcomes were classified using Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST v1.1). For patients treated as part of clinical trials, radiologic responses were determined prospectively. For those treated as part of standard of care, computed tomography (CT) scans were reviewed retrospectively by thoracic radiologists (A.P., D.H., N.L.) blinded to patient clinical data.

Statistical methods

Data were summarized according to frequency and percentage for qualitative variables, as well as by medians and ranges for quantitative variables. Comparisons between groups were performed by using the Γ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for qualitative variables (gender, smoking status, histology, drug, best overall response, type of irAE, and type of corticosteroid), and by the Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables (age, line of therapy, time interval to irAE, and number of infusions before irAE). Progression-free survival (PFS) was measured as the time from the first administration of immunotherapy to progression defined by RECIST v1.1 or death from any cause. Patients who were alive without having experienced progression at the time of analysis were censored at their most recent CT scan. Overall survival (OS) was measured as the time from the first administration of immunotherapy to death from any cause. Patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored at their last follow-up. Survival rates and progression-free survival rates were estimated by using the Kaplan-Meier method. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard regressions were used to assess the efficacy of retreatment on survival rate and progression-free survival rate with and without adjusting for line of therapy, respectively. The significance threshold was set at a p value of ≤0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.2 and R version 3.3.2.

Results

Frequency and clinical features of irAEs requiring treatment interruption

Four hundred eighty-two patients received monoclonal anti–PD-1/PD-L1 as monotherapy (n=432, 90%) or in combination with anti–CTLA-4 (n=50, 10%) at MSKCC from April 2011 to May 2016 (Supplementary Table S1). Sixty-eight patients (14%) experienced an irAE that led to treatment interruption (retreatment cohort, 38 of 68, 56%) or discontinuation (discontinued cohort, 30 of 68, 44%). The baseline characteristics of patients in the retreatment and discontinuation cohorts were similar in terms of age, gender, smoking status, histology, and immune checkpoint inhibitor (Table 1). Patients in the retreatment cohort were more likely to be treated first-line (66% vs. 30%, p=0.007).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients Who Experienced Serious Immune-Related Adverse Events Requiring Treatment Delay

| Retreatment | Discontinuation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients; No. (%) | 38 | 30 | |

| Median age, years (range) | 64 (49–83) | 66 (42–84) | 0.59 |

| Sex, female; No. (%) | 18 (47) | 11 (37) | 0.46 |

| Smoking history, No. (%) | 0.51 | ||

| Yes | 33 (87) | 24 (80) | |

| No | 5 (13) | 6 (20) | |

| Histology, No. (%) | 0.06 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 23 (61) | 26 (87) | |

| Squamous | 11 (29) | 4 (13) | |

| LCNEC or NOS | 4 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Immunotherapy treatment data, No. (%) | 0.18 | ||

| Anti–PD-1 or Anti–PD-L1 | 24 (63) | 24 (80) | |

| Combination w/ anti–CTLA4 | 14 (37) | 6 (20) | |

| Line of therapy, No. (%) | 0.007 | ||

| First | 25 (66) | 9 (30) | |

| Second and beyond | 13 (34) | 21 (70) | |

| Best overall response, No. (%) | 0.62 | ||

| CR or PR | 18 (47) | 12 (40) | |

| SD or PD | 20 (53) | 18 (60) |

Abbreviations: LCNEC, large-cell neuroendocrine cancer; NOS, not otherwise specified carcinoma; PD-1, programmed cell death protein 1; PD-L1, programmed death-ligand 1; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4; CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease.

Onset, severity, and outcomes of initial irAEs

Across all patients, the most common initial irAEs that led to treatment interruption or discontinuation included pneumonitis (19%), colitis (17%), rash (16%), and liver enzyme abnormalities (10%). Between the retreatment and discontinuation cohorts, no differences in types of events (Table 2) or timing of the first irAE (median onset 69 days vs. 73 days, p=0.77; Supplementary Fig. S1) were seen. Initial irAEs were less severe in the retreatment cohort than the discontinuation cohort, with fewer grade 3–4 events (34% vs. 67%, p=0.01), less frequent hospitalizations for management of the irAE (21% vs. 53%, p=0.01), shorter course of steroids (rate of >4 weeks course of steroids of 34% vs. 65%, p=0.04), and no instances of TNFα inhibitor use (0 vs. 3 patients, p=0.05). Retreated patients almost exclusively had resolution of irAEs or improvement to at least grade 1 compared to those who had treatment discontinued (97% vs. 76%, p=0.01; Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Initial Immune-Related Adverse Events (irAEs)

| Retreatment | Discontinuation | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade of the first irAE, No. (%) | 0.01 | ||

| Grades 1 and 2 | 25 (66) | 10 (33) | |

| Grades 3 and 4 | 13 (34) | 20 (67) | |

| Type of irAE; No. (%) | 0.62a | ||

| Pneumonitis | 6 (16) | 7 (23) | |

| Colitis | 7 (18) | 5 (17) | |

| Rash/Pruritus | 5 (13) | 6 (20) | |

| ALT or AST increase | 3 (8) | 4 (13) | |

| Arthralgia/Myalgia | 5 (13) | 1 (3) | |

| Nephritis | 2 (5) | 2 (7) | |

| Pancreatic enzymes elevation | 4 (11) | 0 (0) | |

| Meningitis/Headache | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | |

| Endocrine disordersb | 2 (5) | 1 (3) | |

| Ventricular arrhythmias | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Fatigue | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | |

| ITP | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 2 (7) | |

| Hospitalizations; No. (%) | 8 (21) | 16 (53) | 0.01 |

| Time interval to irAE: | |||

| No. infusions before the irAE: | |||

| Corticosteroid used; No. (%) | 29 (76) | 29 (97) | 0.03 |

| Intravenous | 3 (10) | 12 (40) | |

| Oral | 23 (80) | 16 (53) | |

| Otherc | 3 (10) | 2 (6) | |

| Steroids > 4 weeks; No. (%) | 10 (34) | 15 (65)d | 0.04 |

| Anti-TNF used in the first toxicity; No. (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (9) | 0.05 |

| irAE resolved to: No. (%) | 0.03 | ||

| Grades 0 and 1 | 37 (97) | 23 (79) | |

| Grade >= 2 | 1 (3) | 6 (21) | |

| Death related to irAE; No. (%) | 0 | 2 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ITP, idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; Anti-TNF, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha.

This p-value refers to the comparison of the four more common toxicities

Hypothyroidism (n=1), hyperthyroidism (n=1), adrenal insufficiency (n=1)

Topical steroids or non-absorbable budesonide

There are six patients that were not evaluable for this category for reasons like death, loss of follow-up, and non-compliance.

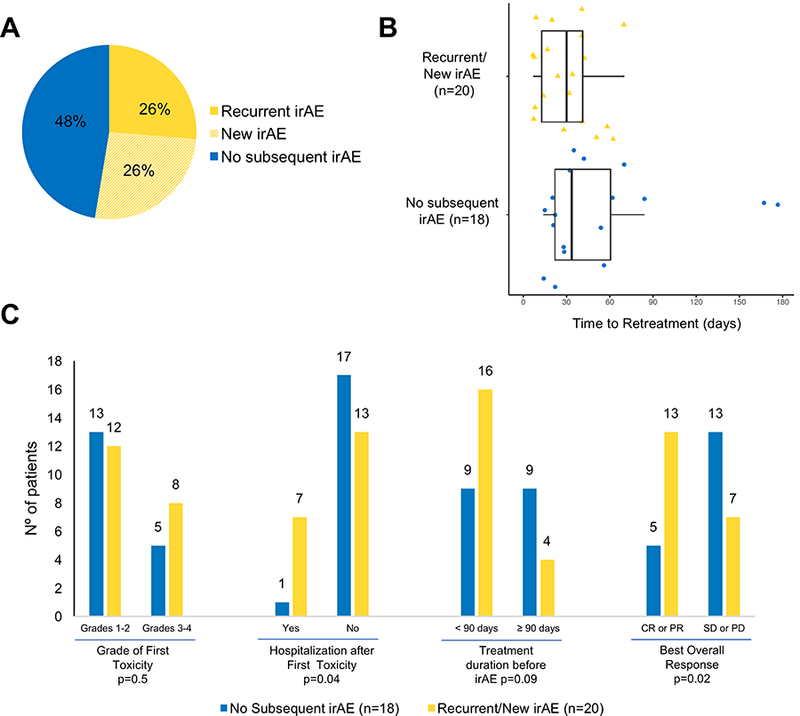

Safety of retreatment following initial irAEs

Of the 38 patients who were retreated with anti–PD-L1 following an initial irAE, 18 (48%) patients had no subsequent irAEs, 10 (26%) had recurrence of the initial irAE, and 10 (26%) developed a new irAE district from the initial event (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Table S2). The median time from detection of the initial irAE to retreatment was 32 days (range: 7 to 177 days). No difference in the rate of recurrent/new events based on the time to retreatment was observed when patients were stratified below and above the median time (10 of 18 [55%] with interval <32 days vs. 10 of 20 [50%] with interval ≥32 days, p=0.5; Fig. 1B). The rate of recurrent/new irAEs was the same among patients who initially had grade 1/2 or grade 3/4 events (12 of 25 [48%] vs. 8 of 13 [61%], p=0.5; Fig. 1C). Recurrent/new irAEs were more common among those requiring hospitalization for the initial irAE (7 of 8 [87%] vs. 13 of 30 [43%], p=0.04; Fig. 1C) and those with complete or partial responses (13 of 18 [72%] vs. 7 of 20 [35%] with stable or progressive disease, p=0.02; Fig. 1C). No evident trends in differential rates of new/recurrent irAEs based on the type of initial irAE were seen, except for higher frequency of recurrent/new irAEs in patients initially with arthralgia or myalgia (4 of 6, 67%).

Figure 1. Features of patients in retreatment cohort.

(A) Rate of no (blue), recurrent (yellow), or new (yellow-striped) irAEs among patients retreated with immunotherapy after an initial irAE (n=38). (B) Box plots of time to retreatment of patients with recurrent/new (n=20) or no irAEs (n=18). The line in the boxes represents the median. Mann-Whitney test was used to compare the two groups and no difference was observed, p=0.5. (C) Rate of recurrent or new irAEs after retreatment. Labels over the top of the bars: number of patients. Fisher’s exact test p-values refer to comparison of recurrent/new irAEs with no recurrent irAE. The significance threshold was set at a p≤0.05. CR: complete response; PR: partial response; SD: stable disease; PD: progressive disease.

The majority of recurrent/new irAEs in the retreatment cohort were mild (12 of 20 [60%] grades 1 and 2; 8 of 20 [40%] grades 3 and 4), occurred early (13 of 20 [65%] occurred within 90 days of retreatment), and were manageable (17 of 20 [85%] resolved or improved to grade 1). However, two treatment-related deaths (5% mortality rate of overall retreatment cohort) occurred (Supplementary Table S3). In one case, a patient treated with anti–PD-1 in combination with anti–CTLA-4 initially developed grade 3 lipase elevation after seven weeks that resolved with treatment interruption only. The patient was eventually retreated with one dose of the combination regimen, but one week later developed colitis and hepatic failure, which lead to death. Another patient received anti–PD-1 therapy for 10 months before developing grade 2 colitis that was treated with budesonide and prednisone. After a seven-week delay, treatment was restarted, but six months after retreatment began, the patient developed pneumonitis, which resulted in death.

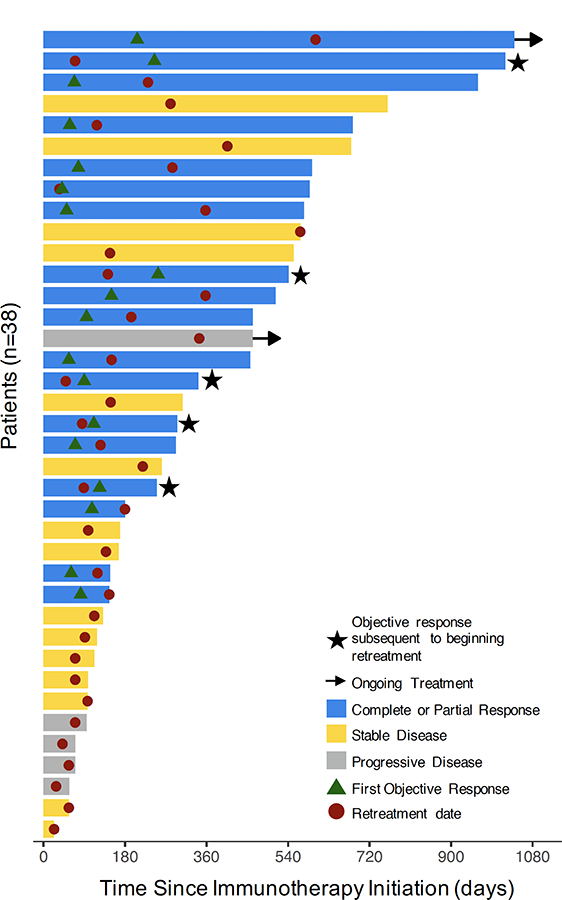

Efficacy of retreatment following initial irAEs

For retreated patients, the median duration of immunotherapy from the start of retreatment was 9.2 months (range: 23 days to 34 months; Fig. 2A). Five patients (13% of entire retreatment cohort; 5 of 26 without partial responses prior to retreatment [19%]) had onset of an objective response following retreatment (Fig. 2). For comparison, in the discontinuation cohort, two patients (7% of entire discontinuation cohort; 2 of 22 without PR prior to discontinuation [10%]) had partial responses (PR) following discontinuation.

Figure 2. Treatment exposure and response duration in the retreatment cohort.

Colored solid bars: best objective response of each patient (n=38). Stars: objective response documented after retreatment. Arrow: ongoing treatment; Circle: retreatment date; Triangle: first objective response.

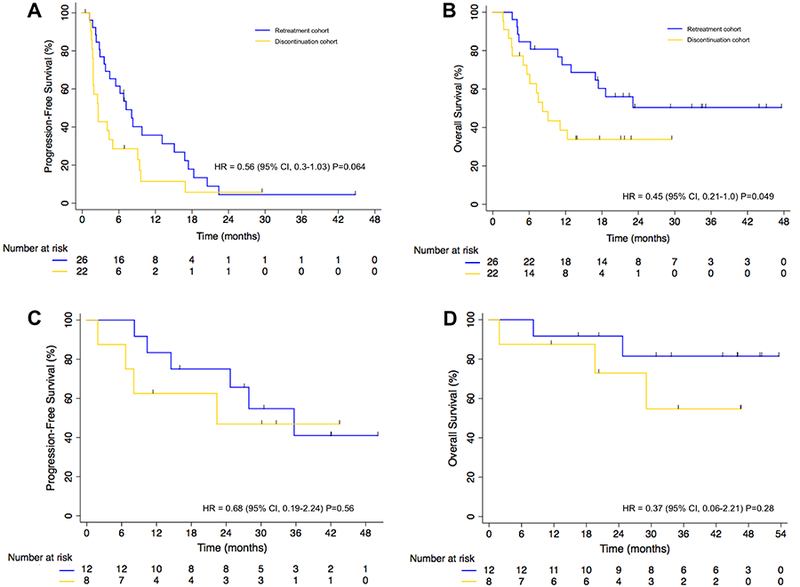

Overall, among the 48 patients who did not have a PR prior to the time of the irAE detection (considered “response eligible”), progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were improved with retreatment (PFS hazard ratio: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.3 to 1.03, p=0.064; and OS hazard ratio: 0.45, 95% CI: 0.21 to 1.0, p=0.049) (Fig. 3A and B). In the multivariate model of the response-eligible patients, with baseline imbalance in number of lines of prior therapy taken into consideration, PFS and OS were significantly improved in those who were retreated (PFS hazard ratio: 0.46, 95% CI: 0.21 to 1.0, p=0.049; and OS hazard ratio: 0.24, 95% CI: 0.093 to 0.61, p=0.0026).

Figure 3. Survival outcomes in lung cancer patients retreated with PD-1 blockade following an initial irAE.

Kaplan-Meier curves of (A) progression-free survival and (B) overall survival of patients in the retreatment (n=26) and discontinuation cohorts (n=22), who did not achieve partial or complete responses before the first irAE. Kaplan-Meier curve of (C) progression-free survival and (D) overall survival of patients in the retreatment (n=12) and discontinuation cohorts (n=8), who achieved partial or complete responses before the first irAE. Differences between curves were statistically analyzed using the log-rank test. Significance threshold was set at a p≤0.05. Censored patients are shown as vertical bars. The chart below the graphs represents the number of patients at risk.

By contrast, among the patients who achieved a partial response prior to the onset of the initial irAE (n=20), PFS and OS were similar in the retreatment and discontinuation cohorts (PFS hazard ratio: 0.68, 95% CI: 0.19 to 2.44, p=0.56; and OS hazard ratio: 0.37, 95% CI: 0.06 to 2.21, p=0.28) (Fig. 3C and D). In the multivariate model, no significant difference in PFS or OS was observed (PFS hazard ratio: 0.61, 95% CI: 0.14 to 2.79, p=0.53; and OS hazard ratio: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.015 to 1.29, p=0.083). The median OS of the retreatment cohort had not been reached, but the estimated 2-year survival from diagnosis of stage IV was 64% (95% CI: 46 to 77%; Supplementary Fig. S2).

Retreatment among patients treated with combination immunotherapy

Fourteen patients (37%) in the retreatment cohort initially received anti–PD-L1 therapy in combination with anti–CTLA-4 therapy. Among these, 8 (57%) continued both drugs, whereas 6 (43%) received anti–PD-L1 only upon retreatment. The rate of new/recurrent irAEs was similar in both treatment scenarios (50% with combination retreatment vs. 54% with monotherapy retreatment, p=1.0). Among these patients who were retreated, 7 had recurrent/new irAEs (4 [57%] grade 2 and 3 [43%] grade 3), and one patient died.

Discussion

This report provides a systematic effort to characterize the safety and benefit of retreatment with anti–PD-L1 in patients with lung cancers who previously developed an irAE that led to treatment interruption. We found that retreatment with anti–PD-L1 therapy resulted in recurrent/new events in 52% of patients. Recurrent/new irAEs following retreatment were usually mild and manageable, but deaths did occur. Among those patients with partial or complete responses prior to the onset of irAEs, survival was similar regardless of retreatment or discontinuation, and in those without response, objective responses sometimes occurred with retreatment.

Patients in the retreatment cohort were distinct from those in the discontinuation cohort, with initial irAEs in the retreatment cohort being generally less severe, more manageable, and more common in the first-line treatment setting. These differences were expected in this analysis, where real-time physician judgment determined whether to retreat or discontinue treatment, and there was appropriate caution about retreating patients with more severe or difficult irAEs. Therefore, this report reflects the irAEs experienced in selected patients, in whom retreatment was considered to be reasonable. Truly life-threatening irAEs were generally not captured in this analysis, and retreatment is not encouraged in this setting.

However, some patients in the retreatment cohort experienced significant irAEs, including grade 3 or grade 4 toxicities. This is a scenario where retreatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors is generally discouraged among experts and in consensus by guidelines, but no data previously existed that aided in this decision. We found that recurrent/new irAEs occurred at similar rates in those who had grade 3 to 4 irAE vs. grade 1 to 2 irAEs (61% vs 48%). Although both rates were high, toxicity was not inevitable upon retreatment. Clinical features of the initial irAE may further refine expectations for retreatment safety. The need for hospitalization due to the first irAE was associated with an increased risk of recurrent/new irAE (up to 87%).

The safety analysis of our report favors a conclusion that retreatment can be carefully considered in some patients with irAEs. However, a separate question is whether it should be considered. The efficacy analysis of patients who had an objective response prior to the onset of an irAE were similar in the retreatment cohort and discontinuation cohorts. We conclude that for patients who achieved an objective response and developed an irAE that requires holding immunotherapy, retreatment upon improvement/recovery of the irAE should not be encouraged. This conclusion aligns with a report of patients with advance melanoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab, where efficacy was similar between patients who discontinued treatment because of adverse events compared to those who did not (15).

Among the patients who do not achieve an early objective response, we found that a minority (but not zero) of patients had onset of objective responses following retreatment. Whether these responses may have occurred in absence of retreatment is not clear. A somewhat similar fraction (13% vs 7%) of patients in the discontinuation cohort had their first objective response onset following treatment discontinuation and in the absence of continued PD-L1 blockade. Nevertheless, among patients without responses at the time the first serious irAE was detected, PFS and OS were improved with retreatment compared to those with treatment discontinued.

The consideration of resuming ICB in the specific context of anti–CTLA-4 plus anti–PD-L1 therapy in melanoma has been explored in a few reports. In patients with prior severe irAEs with ipilimumab and later treated with anti–PD-1 therapy, new irAEs occurred in 34% of patients(16), suggesting a potential overlap in susceptibilities to severe irAEs. In a phase I/II study, a cohort of 21 melanoma patients with severe irAEs from ipilimumab were later treated with nivolumab plus a peptide vaccine, and 33% of these patients developed grade 3–4 treatment-related adverse events (17). In a different analysis of melanoma patients who experienced clinically significant irAEs from combined CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade and were later re-challenged with anti–PD-1 monotherapy, only 18% experienced any grade of irAEs with anti–PD-1 resumption (18).

The retrospective nature of our study is a limitation in terms of subjectivity of the retreatment decision after irAE resolution, but it is unlikely that randomized studies will be conducted to study the issues presented here. Our data demonstrates the risks and benefits of retreatment. Data from patients treated in the standard-of-care setting are sometimes more limited in real-time documentation compared to data collected in prospective clinical trials. We have addressed this by initially identifying patients through systematic review of pharmacy records for objective evidence of treatment interruption, rather than relying on search terms for specific irAEs. Because clinical trials generally have management guidelines that dictate decisions related to retreatment and/or discontinuation, capturing real-world experience is important to comprehensively characterize safety and efficacy. To ensure accurate assessments of objective responses, we also performed retrospective RECIST reads of CT scans in patients not treated in clinical trials.

In summary, in patients with irAEs requiring treatment interruption and later retreated with anti–PD-L1 therapy, recurrent and/or subsequent irAEs occured frequently, but not universally, and were manageable. Based on data reported here, we recommend that patients requiring hospitalization for an initial irAE and those who have already achieved a complete or partial response before an initial irAE should not be retreated. We encourage researchers reporting trials to include detailed information about the management and course of patients where immune checkpoint blockade has been suspended solely due to irAEs. Moving forward, every case should be considered individually and informed decisions of the potential risks and benefits should be the backbone of the conversations with the patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748); a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Career Development Award (MDH); MDH is a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator supported (in part) by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI-98–18); and Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research at MSKCC. This investigator (MDH) is a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Funding: This work was supported by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Support Grant/Core Grant (P30 CA008748); a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Career Development Award (MDH); MDH is a Damon Runyon Clinical Investigator supported (in part) by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (CI-98–18); and Druckenmiller Center for Lung Cancer Research at MSKCC. This investigator (MDH) is a member of the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy.

Footnotes

Disclosures: MGK is a consultant for AstraZeneca. CMR is a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, G1 Therapeutics, and Abbvie. JEC is a consultant for Astra Zeneca and Genentech. MDH is a consultant for Merck Sharp & Dohme, Genentech/Roche, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Syndax, Mirati, and Shattuck labs. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Previous presentations: Presented at the ASCO Annual Meeting 2017, Chicago, USA.

References

- 1.June CH, Warshauer JT, Bluestone JA. Is autoimmunity the Achilles’ heel of cancer immunotherapy? Nat Med 2017;23(5):540–7 doi 10.1038/nm.4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber JS, Kahler KC, Hauschild A. Management of immune-related adverse events and kinetics of response with ipilimumab. J Clin Oncol 2012;30(21):2691–7 doi 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.6750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fecher LA, Agarwala SS, Hodi FS, Weber JS. Ipilimumab and its toxicities: a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist 2013;18(6):733–43 doi 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson DB, Balko JM, Compton ML, Chalkias S, Gorham J, Xu Y, et al. Fulminant Myocarditis with Combination Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med 2016;375(18):1749–55 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1609214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byun DJ, Wolchok JD, Rosenberg LM, Girotra M. Cancer immunotherapy - immune checkpoint blockade and associated endocrinopathies. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2017;13(4):195–207 doi 10.1038/nrendo.2016.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Postow MA, Hellmann MD. Adverse Events Associated with Immune Checkpoint Blockade. N Engl J Med 2018;378(12):1165 doi 10.1056/NEJMc1801663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khoja L, Day D, Wei-Wu Chen T, Siu LL, Hansen AR. Tumour- and class-specific patterns of immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2017;28(10):2377–85 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdx286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolchok JD, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, et al. Overall Survival with Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377(14):1345–56 doi 10.1056/NEJMoa1709684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haanen JBAG, Carbonnel F, Robert C, Kerr KM, Peters S, Larkin J, et al. Management of toxicities from immunotherapy: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017;28(suppl_4):iv119–iv42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brahmer JR, Lacchetti C, Schneider BJ, Atkins MB, Brassil KJ, Caterino JM, et al. Management of Immune-Related Adverse Events in Patients Treated With Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2018:JCO2017776385 doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.6385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puzanov I, Diab A, Abdallah K, Bingham CO, 3rd, Brogdon C, Dadu R, et al. Managing toxicities associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: consensus recommendations from the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Toxicity Management Working Group. J Immunother Cancer 2017;5(1):95 doi 10.1186/s40425-017-0300-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michot JM, Bigenwald C, Champiat S, Collins M, Carbonnel F, Postel-Vinay S, et al. Immune-related adverse events with immune checkpoint blockade: a comprehensive review. Eur J Cancer 2016;54:139–48 doi 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champiat S, Lambotte O, Barreau E, Belkhir R, Berdelou A, Carbonnel F, et al. Management of immune checkpoint blockade dysimmune toxicities: a collaborative position paper. Ann Oncol 2016;27(4):559–74 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdv623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weber JS, Yang JC, Atkins MB, Disis ML. Toxicities of Immunotherapy for the Practitioner. J Clin Oncol 2015;33(18):2092–9 doi 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schadendorf D, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Rutkowski P, et al. Efficacy and Safety Outcomes in Patients With Advanced Melanoma Who Discontinued Treatment With Nivolumab and Ipilimumab Because of Adverse Events: A Pooled Analysis of Randomized Phase II and III Trials. J Clin Oncol 2017: JCO2017732289 doi 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menzies AM, Johnson DB, Ramanujam S, Atkinson VG, Wong ANM, Park JJ, et al. Anti-PD-1 therapy in patients with advanced melanoma and preexisting autoimmune disorders or major toxicity with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol 2017;28(2):368–76 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdw443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weber J, Gibney G, Kudchadkar R, Yu B, Cheng P, Martinez AJ, et al. Phase I/II Study of Metastatic Melanoma Patients Treated with Nivolumab Who Had Progressed after Ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Res 2016;4(4):345–53 doi 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pollack MH, Betof A, Dearden H, Rapazzo K, Valentine I, Brohl AS, et al. Safety of resuming anti-PD-1 in patients with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) during combined anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD1 in metastatic melanoma. Ann Oncol 2018;29(1):250–5 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdx642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.